Abstract

Providing financial incentives can be a useful behavioral economics strategy for increasing fruit and vegetable intake among consumers. It remains to be determined whether financial incentives can promote intake of other low energy-dense foods and if consumers who are already using promotional tools for their grocery purchases may be especially responsive to receiving incentives. This randomized controlled trial tested the effects of offering financial incentives for the purchase of healthy groceries on 3-month changes in dietary intake, weight outcomes, and the home food environment among older adults. A secondary aim was to compare frequent coupon users (FCU) and non-coupon users (NCU) on weight status, home food environment, and grocery shopping behavior. FCU (n = 28) and NCU (n = 26) were randomly assigned to either an incentive or a control group. Participants in the incentive group received $1 for every healthy food or beverage they purchased. All participants completed 3-day food records and a home food inventory and had their height, weight, and waist circumference measured at baseline and after 3 months. Participants who were responsive to the intervention and received financial incentives significantly increased their daily vegetable intake (P = 0.04). Participants in both groups showed significant improvements in their home food environment (P = 0.0003). No significant changes were observed in daily energy intake or weight-related outcomes across groups (P < 0.12). FCU and NCU did not differ significantly in any anthropometric variables or the level at which their home food environment may be considered ‘obesogenic’ (P > 0.73). Increased consumption of vegetables did not replace intake of more energy-dense foods. Incentivizing consumers to make healthy food choices while simultaneously reducing less healthy food choices may be important.

Keywords: Financial incentives, obesity, groceries, diet

Introduction

Provision of financial incentives designed from behavioral economics concepts are increasingly being tested for their effectiveness in changing health behaviors including, but not limited to, smoking cessation, medication adherence, weight loss, and promotion of physical activity (1). A number of randomized studies were also conducted recently to test the effectiveness of providing financial incentives for the purchase of healthy foods and beverages on promoting their intake. For example, the USDA Healthy Incentives Pilot (HIP) project aimed to determine the impact of financial incentives provided to participants in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) for the purchase of qualifying fruits and vegetables on intake (2). Participants in the intervention (HIP) group received 30 cents for every SNAP dollar they spent on targeted fruits and vegetables (e.g., fresh, frozen, canned, dried fruits and vegetables without added sugars, fats, oils, and salt) at participating retailers. The results showed that HIP participants consumed almost a quarter of a cup or 26% more targeted fruits and vegetables per day compared to participants in the control group. Similarly, Geliebter and colleagues (3) tested the effect of a 50% discount on low energy-dense fruits and vegetables, bottled water, and diet sodas on purchasing behaviors, food intake, and body weight in overweight and obese shoppers in two Manhattan supermarkets. The results showed that the gross weekly purchasing of discounted fruits and vegetables was more than three times greater by the intervention group than the control group, an effect which was partially sustained during the 4-week follow-up period. Together, these data suggest that subsidizing purchases of fruits and vegetables by providing financial incentives can be an effective strategy to significantly increase intake of these foods. It remains to be tested if extending financial incentives to other low energy-dense foods and beverages can significantly impact daily energy intake and weight-related outcomes.

Many middle-aged and older Americans are economizing on their food purchases and coupons are one of several promotional tools that supermarkets use to promote grocery sales. It is estimated that 27% of households frequently use grocery coupons at a variety of retailers (4). Novel distribution techniques for coupons through digital channels (e.g., email promotions, mobile device apps), which personalize the display of coupons are increasingly being used by retailers and have shown to yield higher rates of coupon redemptions and more redemptions for brands/products that are new to consumers (5). While many prior studies have focused on coupon use as a sales promotion technique (6-9), little is known about the extent to which coupons for groceries may promote obesogenic home food environments and higher weight status among consumers. Many coupons encourage the purchase of large quantities of prepackaged and processed foods and often reward shoppers by adding ‘free’ products if they purchase certain quantities. In fact, a content analysis of 1,056 online coupons showed that the largest percentage of coupons was for processed snack foods, candies and desserts (25%), prepared meals (14%), cereals (11%), and beverages such as sodas, juices, and energy/sports drinks (12%). Only 4% of the online coupons were for the purchase of fruits and vegetables (10). Availability and easy accessibility of unhealthy foods and beverages in the home, such as high-fat foods, sweet and savory snacks, and sugar-sweetened beverages, has been shown to promote increased intake of those foods and beverages in youth and adults (11-13).

The primary aim of this pilot study was to test, in a randomized-controlled trial, the effects of financial incentives for the purchase of healthy foods and beverages on 3-month changes in dietary intake, BMI and waist circumference, and the home food environment among an urban sample of middle-aged and older FCU and NCU. We hypothesized that participants in the incentivized group would show significant improvements in dietary intake, BMI and waist circumference, and their home food environment compared to participants in the control group. A secondary aim of the study was to compare, in a baseline analysis, FCU and NCU on weight measures, home food environments, and grocery shopping behaviors. We hypothesized that compared to NCU, FCU would have a significantly higher weight status and reside in a more obesogenic home food environment. We further hypothesized that the primary considerations for food product choices among FCU would be price and economic value, while NCU focus more on the perceived nutritional value and quality of grocery purchases.

Study Design

This pilot study, a randomized controlled trial, tested the effects of providing financial incentives for the purchase of healthy groceries on 3-month changes in dietary intake, BMI and waist circumference, and the home food environment among older adults who either frequently or never used coupons for their grocery purchases. Participants were randomly assigned to either an incentivized group (Incentive) or a control group (Control). Coupon usage (FCU / NCU) was counterbalanced across groups so that each group consisted of ∼50% FCU and ∼50% NCU. At baseline, and again at a 3-month follow-up visit, participants were asked to complete a series of questionnaires and had their height, weight, and waist circumference measured.

Participants and Recruitment

Participants in this study were 54 racially/ethnically diverse men and women, ages 40 to 70 years, living in Philadelphia. Participants were recruited through newspaper and online advertisements. To be included in the study, participants had to be between 40 and 70 years of age and qualify as a FCU or NCU. FCU were defined as individuals who, during a telephone screening interview, reported that they 1) use grocery coupons at least once a week or every time they shop for groceries and 2) purchase at least half of their grocery items with coupons each time they shop. NCU were individuals who reported never using coupons when shopping for groceries. Individuals were excluded from participating in the study if they had medical conditions or were using medications that affect appetite, food intake, and body weight; were on a special diet or dieting; had severe food allergies or dietary restrictions; or were occasional coupon users.

Interested men and women were screened by telephone to determine their eligibility for the study. Those who qualified for the study from the screening interview were invited to come to the Center for Weight and Eating Disorders at the University of Pennsylvania for their baseline visit. During this visit, participants received a detailed explanation of study procedures and were asked to provide voluntary consent to participate in the study by signing the consent form. Subjects were compensated $100 for the successful completion of all anthropometric and dietary assessments over the course of the study. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Pennsylvania.

Intervention and Control Groups

Eligible participants were randomly assigned to either an incentivized group (Incentive) or a control group (Control). Participants in the Incentive group received a brief orientation to the incentive program at the beginning of the study (baseline visit). During this orientation, a clinical research coordinator informed participants that for every healthy food or beverage they purchased, they would receive $1 (in cash) in financial incentives. The maximum amount of financial incentives that participants could earn was $100 (for a total of 100 healthy foods and/or beverages) over the 3-month study duration. Foods and beverages that qualified for the incentive program included fruits and vegetables (fresh, canned, frozen); no-calorie or low-calorie (< 50 kcal per 8 fl oz) beverages; and any foods with an energy density < 1.5 calories per serving (g), such as soups, legumes, or low-fat dairy and meat products. Participants were given $1.00 for every food item purchased per grocery transaction that met this definition. This also meant that, for example, if a participant purchased five apples during one transaction and provided proof of purchase with one grocery receipt, they were given $1.00. If a participant purchased one apple at five independent transactions over the course of their participation, they were given $1.00 per transaction for a total of $5.00. This incentive also applied to the purchase of food items with no or low calories, including diet soda, that have no nutritional value. During the orientation, participants were also trained in how to derive the energy density (kcal/g) of a food product from a nutrition facts label. Participants were asked to either mail with a prepaid envelope or deliver in person the nutrition facts labels of healthy foods and beverages they purchased along with grocery receipts. Participants were instructed to provide solely the receipt as proof of purchase to receive the financial incentive for the purchase of fresh fruits and vegetables as most fresh fruits and vegetables are not accompanied by a nutrition facts label. Participants in the Control group did not receive financial incentives for their grocery purchases and did not receive any nutrition training.

Assessment of Height, Weight, and Waist Circumference

During the baseline and 3-month follow-up visits, trained research staff measured participants' height, weight, and waist circumference. All measures were taken with participants wearing light clothing and having their shoes removed. Participants' weight was measured on a digital scale (Tanita BWB-800, Arlington Heights, IL; accurate to 0.1kg); their standing height was measured on a wall-mounted stadiometer (Veder-Root, Elizabethtown, NC; accurate to 0.1cm); and their abdominal waist circumference was measured with a non-stretchable fiberglass tape (accurate to 0.1 cm) following the measurement techniques described in Lohman et al. (14). Anthropometric measurements were taken in duplicate; the mean was used in analyses. Participants' BMI was calculated as weight (kg) divided by height (m) squared. Participants were classified as underweight (BMI < 18.5 kg/m2), normal-weight (BMI 18.5 – 24.9 kg/m2), overweight (BMI 25.0 – 29.9 kg/m2), or obese (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) (15). Participants' waist-to-height ratio was calculated as waist circumference divided by height (16).

Habitual Dietary Intake

Three-day Food Records

At baseline and again at the 3-month follow-up visit, participants were asked to complete food records for 3 days (2 weekdays, 1 weekend day). During the baseline visit, research staff trained participants on how to complete the food records. Specifically, using written instructions and visual aids, participants were trained on the details (i.e., time, type, preparation method, and amounts of foods and beverages consumed) of accurately completing food records and estimating portion sizes. Participants received a sample of a correctly completed food record and a visual aid for estimating food portions. Food records were entered, double-checked by trained staff members, and analyzed using the Food Processor SQL software (ESHA), version 10.6.3 (2010, ESHA Research, Salem, OR). Dietary outcome variables for this study included 3-month changes in daily energy intake (kcal); percent energy consumed from fat, carbohydrate, and protein; dietary fiber; calcium; and food group intake (fruits, vegetables, grains, dairy, meat, and other (fats, oils, and sweets) for participants in the Incentive and Control groups.

Screening for Implausible Reporters

For the food record data, we used the approach by Huang et al. (17, 18) to screen for implausible reporters of dietary intake. Specifically, participants were considered implausible reporters if their average reported energy intake (rEI) across the three days as a percentage of predicted energy requirement (pER) was outside a ± 1 standard deviation (SD) cutoff. Computation of participants' pER was based on age-, sex-, and weight-, and height-specific equations (19), using a physical activity coefficient of 1.00 (i.e., sedentary) for all participants. Using this approach, a total of 20 participants (8 Control, 12 Incentive) were identified as implausible reporters at either a) baseline, b) Month 3, or c) both time points. Data from implausible reporters were excluded from all dietary intake analyses. Additionally, of those participants who completed the study, a total of 5 participants (3 Control, 2 Incentive) failed to return food records at one time point (baseline or Month 3).

Assessment of Participants' Home Food Environment

At baseline and at the 3-month follow-up visit, participants were asked complete the Home Food Inventory (20), which assesses availability of 190 food items in the home that represent 13 major food categories. Participants were instructed to complete the inventory while at home, by inspecting all areas of the home where food is stored, including the refrigerator, freezer, pantry, cupboard, and other areas (e.g., basement), and return the completed inventory by mail. Food items are listed in a checklist type format with yes/no (1/0) response options. Higher scores indicate greater availability. The inventory provides an obesogenic household food availability score (ranging from 0-71), which represents the summative score for regular-fat versions of cheese, milk, yogurt, other dairy, frozen desserts, prepared desserts, savory snacks, added fats; regular-sugar beverages; processed meat; high-fat quick, microwavable foods; candy; access to unhealthy foods in refrigerator and kitchen. Participants' 3-month change (baseline to follow-up visit) in this score was used in the statistical analysis. The inventory has shown acceptable criterion and construct validity for all major food category scores and the obesogenic home availability score (20).

Other Questionnaires

Participants were also asked to complete a demographic questionnaire, which included the 6-item USDA Food Security Survey (21), questions about participants' socioeconomic and employment status, and an assessment of participants' attitudes towards grocery stores. On the attitudes towards grocery stores questionnaire, participants were asked to indicate on a 5-point scale (ranging from ‘not important at all’, ‘not very important’, ‘impartial’, ‘somewhat important’, to ‘extremely important’) the level of importance they assign to 13 grocery store characteristics (i.e., quality of food, healthfulness of food, availability of food, store atmosphere, price, customer service, cleanliness of store, in-store signage, convenient business hours, travel time to grocery store, supporting local businesses, buying locally grown foods, availability of organic foods). For the analysis, ratings of assigned importance of the grocery store characteristics were dichotomized into important (i.e., ‘somewhat important’, ‘extremely important’) and not important (i.e., ‘not important at all’, ‘not very important’, ‘impartial’).

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using the statistical software SAS (Version 9.2; SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC) and SPSS (Version 20; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). The Shapiro-Wilk test was used in conjunction with distribution plots and summary statistics to confirm normal distribution of continuous variables. To test the main aim, a mixed-effects linear model with repeated measures assessed 3-month changes in participants' dietary and weight-related outcomes and obesogenic household food availability score by group (Incentive vs. Control). The fixed factor effects used in all models were group (Incentive, Control) and time (baseline, month 3). The group-by-time interaction was tested and removed if not significant. One advantage of a mixed-effects linear model analysis is that it uses the intention to treat (ITT) principle and allows for analysis of all available data points, which represents the most unbiased way to obtain study estimates. To test the influence of coupon status (FCU/NCU) on all outcome measures, we performed an analysis that tested the a) group-by-time-by-coupon status interaction on 3-month changes in all outcome measures in a mixed-effects linear model and b) group-by-coupon status interaction on 3-month changes in a general linear model using the change variables (month 3 value – baseline value) for all outcomes. The model for the dietary analysis included plausible reporters only (Control group: 18 subjects at baseline, 19 subjects at Month 3; Incentive group: 14 subjects at baseline, 15 subjects at Month 3). Because only a subgroup (57%) of subjects in the Incentive group were responsive to the intervention and returned nutrition facts labels in exchange for financial incentives, we also performed a subgroup analysis which included a) Incentive group: only subjects who returned nutrition facts labels, received financial incentives, and were deemed plausible reporters (10 subjects at baseline, 11 subjects at Month 3), and b) Control group: all subjects who were deemed plausible reporters (18 subjects at baseline, 19 subjects at Month 3). One incentivized subject (with a reported vegetable intake of 7.1 cups per day at Month 3) was identified as an outlier for vegetable intake during normality testing and excluded from both the primary and the subgroup analysis.

For the secondary aim, we used independent two-sample t-tests (FCU vs. NCU) for normally distributed continuous variables, nonparametric tests (Mann-Whitney test) for non-normally distributed variables, and Chi-Square and Fisher's Exact tests for categorical variables to compare FCU and NCU in anthropometric and demographic measures as well as variables related to their grocery shopping behavior and home food environment.

Descriptive statistics are reported as mean (± SD) for continuous variables or as frequency (percentage) for categorical variables. Results from the mixed linear model analysis are presented as model-based means (± SEM). Reported P values are two-sided and P < 0.050 was considered significant for all tests.

Results

Demographic Characteristics of Treatment Groups

Table 1 depicts the demographic and anthropometric characteristics of study participants. Participants in Incentive and Control groups did not differ significantly in any of the demographic or anthropometric characteristics (P > 0.22). The majority of study participants in both groups were non-Hispanic African American, single, with a household income of less than $25,000. Approximately half of the subjects participated in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and more than one third experienced very low or low household food security. About 75% of subjects in both groups were considered overweight or obese.

Table 1.

Baseline demographic and anthropometric characteristics of participants in the Incentive (N = 28) and Control (N = 26) groups.

| Characteristic | Incentive | Control | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Age (years) | 52.0 ± 1.3 | 51.6 ± 1.5 | 0.84 |

|

| |||

| Sex (Male / Female) | 13 (46%) / 15 (54%) | 9 (35%) / 17 (65%) | 0.42 |

|

| |||

| Coupon Status (FCU / NCU) | 15 (54%) / 13 (46%) | 13 (50%) / 13 (50%) | 0.79 |

|

| |||

| Race | |||

| Asian | 1 (4%) | 0 (0%) | |

| African American | 21 (75%) | 22 (85%) | |

| Caucasian | 3 (11%) | 3 (12%) | |

| More than one race | 3 (11%) | 1 (4%) | 0.72 |

|

| |||

| Ethnicity1 | |||

| Hispanic | 3 (11%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Non-Hispanic | 22 (79%) | 22 (85%) | 0.39 |

|

| |||

| Marital Status | |||

| Single | 19 (68%) | 16 (62%) | |

| Married | 4 (14%) | 5 (19%) | |

| Divorced, separated, or widowed | 5 (18%) | 5 (19%) | 0.92 |

|

| |||

| Education2 | |||

| High School | 15 (54%) | 11 (42%) | |

| College | 8 (29%) | 8 (31%) | 0.63 |

|

| |||

| Employment status | |||

| Work full-/part-time, self-employed | 13 (46%) | 9 (35%) | |

| Unemployed | 10 (36%) | 8 (31%) | |

| Other | 5 (18%) | 9 (35%) | 0.36 |

|

| |||

| Household income | |||

| < $25,000 | 19 (68%) | 18 (69%) | |

| $25,000 - $50,000 | 8 (29%) | 4 (15%) | |

| > $50,000 | 1 (4%) | 4 (15%) | 0.24 |

|

| |||

| Participation in SNAP3 (% yes) | 16 (57%) | 14 (54%) | 0.81 |

|

| |||

| (Very) low household food security | 13 (46%) | 9 (35%) | 0.38 |

|

| |||

| Height (m) | 1.68 ± 0.01 | 1.68 ± 0.02 | 0.96 |

|

| |||

| Weight (kg) | 82.9 ± 4.5 | 87.4 ± 3.4 | 0.43 |

|

| |||

| Waist circumference (cm) | 100.7 ± 4.6 | 102.9 ± 2.6 | 0.22 |

|

| |||

| Waist-to-height ratio | 0.6 ± 0.03 | 0.6 ± 0.02 | 0.27 |

|

| |||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 29.3 ± 1.5 | 31.0 ± 1.3 | 0.39 |

|

| |||

| Weight status | |||

| Underweight (BMI < 18.5 kg/m2) | 1 (4%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Normal-weight (BMI 18.5 – 24.9 kg/m2) | 9 (32%) | 4 (15%) | |

| Overweight (BMI 25.0 – 29.9 kg/m2) | 6 (21%) | 10 (39%) | |

| Obese (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) | 12 (43%) | 12 (46%) | 0.26 |

Ethnicity unknown for 7 participants (3 Incentive, 4 Control);

Education unknown for 12 participants (5 Incentive, 7 Control);

Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program

Disbursement of Incentives

The total number of nutrition facts labels that participants in the Incentive group returned over the course of the 3-month intervention was 697. The percentage of returned labels that qualified as healthy food/beverage, on average, was 82% ± 19.7 (range: 38 – 100%). Only a subgroup of subjects (57%) in the Incentive group returned nutrition facts labels and thus received financial incentives. Eight subjects (50%) returned between 0 and 20 labels; 1 subject (6%) returned between 20 and 40 labels; 3 subjects (19%) returned between 40 and 60 labels; 1 subject (6%) returned between 60 and 80 labels; and 3 subjects (19%) returned between 80 and 100 labels, respectively. The total number of nutrition facts labels returned significantly differed by coupon user status with FCU returning a significantly higher number of labels than NCU (46.3 ± 48.8 labels vs. 11.8 ± 14.9 labels; P = 0.04).

Three-Month Changes in Dietary Intake and Weight-Related Outcomes

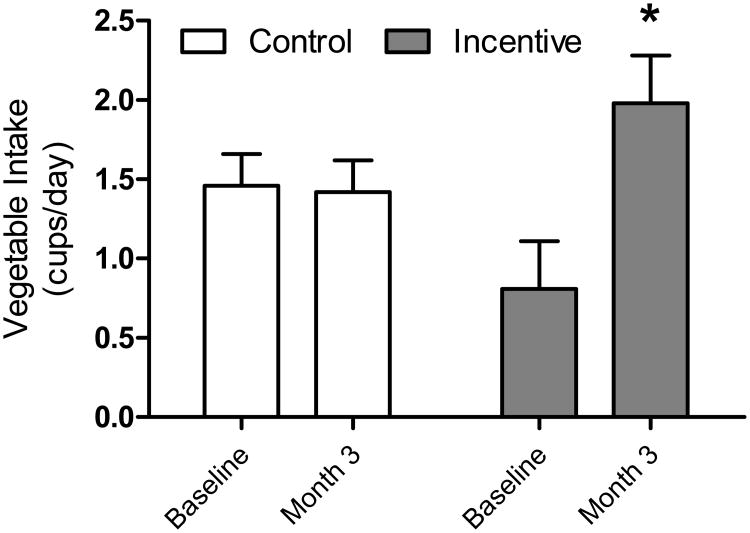

Table 2 depicts the mean dietary intakes and weight-related outcomes of the Control and Incentive groups at baseline and month 3. There was a borderline significant time-by-group interaction (P = 0.05) for percent energy consumed from protein after the 3-month intervention. None of the remaining time-by-group interactions were statistically significant for any of the nutrients or food groups. There was a significant main effect of time (P = 0.04) for calcium intake indicating that both groups increased their calcium intake over the course of the intervention. When basing the analyses on only those participants in the treatment group who turned in nutrition facts labels and thus received financial incentives for their grocery purchases, the results showed a significant group-by-time interaction (P = 0.04) for vegetable intake. Post-hoc comparisons indicated a significant difference in daily vegetable intake between baseline and month 3 for the Incentive group (P = 0.02), but not for the Control group (P = 0.91). Participants in the Incentive group who returned nutrition facts labels and received financial incentives significantly increased their daily vegetable intake over the course of the intervention (Figure 1). The difference in daily vegetable intake between the Control and Incentive groups at baseline was not significant (P = 0.08).

Table 2. Dietary intake, weight-related outcomes, and home food environment (model-based means ± SEM) by treatment group over time.

| Control | Incentive | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Baseline (N = 18) |

Month 3 (N = 19) |

Baseline (N = 14) |

Month 3a (N = 15) |

P-values |

| Dietary Intake | |||||

| Daily energy intake (kcal) | 2,049.3 ± 128.4 | 2,016.3 ± 125.0 | 2,111.3 ± 145.5 | 2,030.5 ± 140.6 | ns |

| Fat (% energy) | 36.5 ± 1.6 | 35.8 ± 1.6 | 35.2 ± 1.9 | 35.3 ± 1.8 | ns |

| Carbohydrate (% energy) | 47.2 ± 2.0 | 48.5 ± 2.0 | 48.0 ±2.3 | 47.9 ± 2.2 | ns |

| Protein (% energy) | 16.4 ± 0.9 | 15.6 ± 0.8 | 15.2 ± 0.9 | 16.8 ± 0.9 | Time*Group: P = 0.05 |

| Fiber (g) | 15.3 ± 0.8 | 15.6 ± 1.8 | 19.6 ± 2.1 | 19.4 ± 2.0 | Group: P = 0.08 |

| Calcium (mg) | 563.9 ± 68.5 | 653.3 ± 67.1 | 556.1 ± 76.9 | 716.6 ± 74.8 | Time: P = 0.04 |

| Fruits (cups) | 0.9 ± 0.2 | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | ns |

| Vegetables (cups) | 1.5 ± 0.2 | 1.4 ± 0.2 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 1.6 ± 0.2 | ns |

| Grains (oz-equivalents) | 7.0 ± 0.6 | 6.2 ± 0.6 | 6.0 ± 0.7 | 5.6 ± 0.7 | ns |

| Dairy (cups) | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 0.7 ± 0.1 | ns |

| Meat (oz-equivalents) | 7.0 ± 1.0 | 6.7 ± 0.9 | 5.7 ± 1.1 | 8.3 ± 1.1 | ns |

| Anthropometric Measures | |||||

| Weight (kg) | 87.4 ± 4.1 | 86.0 ± 4.0 | 82.9 ± 3.9 | 82.7 ± 3.9 | Time: P = 0.06 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 31.0 ± 1.4 | 30.5 ± 1.4 | 29.3 ± 1.4 | 29.0 ± 1.4 | Time: P = 0.02 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 102.9 ± 3.0 | 103.2 ± 3.0 | 98.1 ± 2.9 | 98.6 ± 3.0 | ns |

| Waist-to-height ratio | 0.62 ± 0.02 | 0.62 ± 0.02 | 0.59 ± 0.02 | 0.59 ± 0.02 | ns |

| Home Food Environment | |||||

| Obesogenic household food availability score | 25.6 ± 2.3 | 22.1 ± 2.3 | 23.5 ± 2.3 | 20.1 ± 2.3 | Time: P = 0.0003 |

The analysis for vegetable intake included 14 subjects at Month 3. One subject with a reported vegetable intake of 7.1 cups per day was deemed an outlier and not included in the analysis.

Figure 1.

Mean (± SEM) vegetable intake (cups/day) at baseline and month 3 for participants in the Control (baseline: n = 18; month 3: n = 19) and participants in the Incentive group who received financial incentives for returning nutrition facts labels for healthy foods/beverages (baseline: n = 10; month 3: n = 10). All subjects included in this subgroup analysis were deemed plausible reporters. A mixed-effects linear model with repeated measures was used to assess 3-month changes in vegetable intake by group. The results showed a significant group-by-time interaction (P = 0.04) for vegetable intake. Post-hoc comparisons indicated a significant difference in daily vegetable intake between baseline and month 3 for the Incentive group (P = 0.02; denoted by (*), but not for the Control group (P = 0.91).

With respect to the weight-related outcomes, none of the time-by-group interactions were statistically significant. There was a significant main effect of time (P = 0.02) for BMI showing a small decrease in BMI in both groups over the course of the intervention.

The analysis that tested the effects of coupon user status on all outcomes showed non-significant findings for the 3-way interaction (group-by-coupon status-by-time; P > 0.13) and the change score analysis (P > 0.15) for all outcomes. When performing the analyses with only those participants in the intervention group who received financial incentives, the change score analysis showed a significant group-by-coupon status interaction for percent calories consumed from protein (P = 0.03). FCUs in the Incentive group showed a significantly greater change in percent energy consumed from protein compared to NCUs (2.0 ± 1.2% vs. -4.0 ± 1.8%; P = 0.01).

Three-Month Changes in Home Food Environment

With respect to participants' home food environment, there was a significant main effect of time (P = 0.0003) indicating that both groups showed improvements in their obesogenic household food availability scores over the 3-month period (Table 2).

Demographic and Anthropometric Characteristics of FCU and NCU

The majority of both FCU and NCU were female (∼60%) non-Hispanic African Americans (∼80%) and single (∼65%). About one third of all participants had an Associate or college degree and about 40% indicated they were employed full-time, part-time, or self-employed. Compared to FCU, a larger percentage of NCU earned less than $25,000 per year (85% vs. 54%; P = 0.03), participated in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP; 65% vs. 46%; P = 0.18), and experienced low to very low household food security (46% vs. 36%; P = 0.44). There were no significant differences between FCU and NCU in weight, BMI, waist circumference, and waist-to-height ratio (P > 0.73). The majority of FCU and NCU were considered overweight or obese (72% vs. 77%).

Grocery Shopping Behavior of FCU and NCU

A significantly greater percentage of FCU than NCU indicated that they shopped at wholesale clubs (46% vs. 19%, P = 0.03), but FCU and NCU did not differ in the frequency with which they shopped for groceries or in the amount of money spent on groceries (P > 0.35). In addition to buying groceries with coupons, a significantly greater percentage of FCU, compared to NCU, indicated that they buy certain items only if they are on sale to save money on grocery bills (82% vs. 31%; P < 0.001). Almost one third (27%) of NCU indicated that they did not use any particular methods to save money on grocery bills. In addition to using coupons for groceries, a significantly greater percentage of FCU, compared to NCU, indicated that they use coupons for restaurants/dining out (75% vs. 27%), fast food establishments (82% vs. 31%), activities/entertainment (50% vs. 12%), and services (39% vs. 0%).

When asked about the importance of a variety of grocery store characteristics, a significantly greater percentage of FCU, compared to NCU, indicated that supporting local business (68% vs. 35%; P = 0.015) and buying locally grown foods (64% vs. 35%; P = 0.03) was important to them. FCU and NCU did not significantly differ in their perceived importance of the remaining grocery store characteristics (P > 0.10).

Home Food Environment of FCU and NCU

The mean obesogenic household food availability score did not differ significantly between FCU and NCU (25.0 ± 2.6 vs. 24.6 ± 2.5; P = 0.90), which indicates that participants' home food environments were similar with respect to the availability of energy-dense foods and snacks in the home.

Discussion

This study showed that older adults who were responsive to the intervention and received financial incentives for purchasing healthy foods and beverages significantly increased their daily vegetable intake, but there were no significant differences in total energy intake or weight-related outcomes across groups. This study also showed that consumers who frequently used coupons for their grocery purchases, compared to those who never used coupons, significantly differed in household income and a variety of shopping behaviors, but they did not differ significantly in anthropometric variables, weight status, or the level at which their home food environment may be considered ‘obesogenic.’

The primary aim of this study was to test, in a randomized controlled trial, the effects of providing financial incentives for the purchase of healthy groceries on 3-month changes in dietary intake, BMI and waist circumference, and the home food environment among older adults. The results of the study showed that the intervention was successful in increasing daily vegetable intake, but only in a subset of participants in the Incentive group, namely those who returned nutrition facts labels and thus received the financial incentives for qualifying grocery purchases. Of those who did receive financial incentives, the majority (67%) of them were FCU, which was an unexpected finding. This finding may have important implications for public health researchers in that it suggests that consumers who are already using promotional tools, such as coupons, to save on their grocery purchases may be especially responsive to an incentive-based nutrition intervention. Future interventions that use behavioral economic concepts may therefore consider targeting this group of consumers. At the same time, the lack of responsiveness among NCU also has important implications in that it appears to be more difficult to reach NCU with financial incentives and therefore may require different or additional strategies beyond providing financial incentives to promote health behavior changes among those consumers.

Despite the increase in vegetable intake among incentivized participants, they did not differ significantly in their daily energy intake or weight-related outcomes from participants in the control group. This suggests that increased vegetable intake may not have substituted intake of more energy-dense foods among incentivized participants. Increased vegetables intake, however, has been shown to be associated with other health benefits such as a potential reduction in the risk for cancer (22, 23), hypertension (24), cardiovascular disease (25-29), and inflammation associated with rheumatoid disease (30). Incentivizing consumers for making healthy food choices while at the same time reducing less healthy food choices may be required to achieve reductions in daily energy intake and weight-related outcomes.

Our findings further indicated significant improvements in the obesogenic household food availability scores and BMI in both groups over time. It remains unclear as to why these two outcomes improved in both groups. It is possible that participating in this clinical trial may have changed their grocery shopping behavior or removed less desirable foods from the home. Future studies may benefit from utilizing a more objective assessment of the home food environment (e.g., inspection by research staff, digital photographs), rather than rely on participant report, to determine the healthfulness of the foods in the home over time.

A secondary aim of this study was to compare middle-aged and older FCU and NCU on weight status, home food environment, and grocery shopping behavior. Contrary to our hypothesis, FCU did not exhibit a higher weight status or a more obesogenic home food environment compared to NCU. In this study, over 70% of both FCU and NCU were considered overweight/obese and the mean obesogenic household food availability score did not significantly differ between FCU and NCU. It is important to note, however, that while this score indicates the availability of less healthy foods and beverages in the home, it does not provide information about the quantity of those items. With many grocery coupons promoting 2-for-1 deals, it is still possible that the home environments of FCU contain larger quantities of less healthy foods and beverages, which is an important area for future research. Given the cross-sectional nature of this analysis, future studies are needed to determine longer-term diet and weight trajectories of FCU and NCU.

With respect to participants' grocery shopping behavior, the data from this study indicate that a greater number of FCU, compared to NCU, shopped at wholesale clubs and bought certain grocery items only if they were on sale to save on grocery bills. Further, a greater percentage of FCU than NCU indicated that they use coupons for restaurants/dining out, fast food establishments, activities/entertainment, and other services. These data suggest that FCU, as a group, may be more strategic than NCU in economizing not only on grocery purchases but on expenditures in other categories as well despite the fact that they showed higher household incomes and lower participation rates in SNAP compared to NCU. It is also possible, however, that NCU, due to their overall lower socioeconomic status, could not afford memberships to wholesale clubs or lived in neighborhoods which offered limited access to wholesale clubs or restaurants. FCU did not differ significantly from NCU in the amount of money they spent on groceries per week. Given that FCU received considerable discounts on their grocery purchases due to coupon usage, one might have expected that they spend less money on groceries per week. It is possible that FCU shopped at more expensive stores or purchased more items per trip. It is also possible that the coupons utilized by FCU are contingent on buying (and thus paying) more before discounts are applied. It is unlikely that they shopped for more people in their homes because household size did not differ significantly between FCU and NCU (data not shown). Contrary to our initial hypothesis, FCU did also not differ from NCU in their perceived importance of the quality and healthfulness of foods or price when shopping for groceries. The only grocery store and restaurant characteristics that differed between groups were support for local businesses, availability of locally grown foods, and restaurant service, all of which FCU rated higher in perceived importance than did NCU.

The strengths of this pilot study involve the inclusion of a large number of urban minority adults. The study also had limitations. One, the definition of a ‘healthy food’ (e.g., deriving the energy density of a food from a nutrition facts label) may have required more extensive nutrition training for participants in the intervention group than was provided. Also, the return of the nutrition facts labels along with grocery store receipts by mail or in person to obtain a financial incentive likely was very cumbersome for some participants. Future studies should combine an incentive-based intervention with nutrition education and make use of technology to offer real-time incentives for in-store purchases of healthy foods. Third, the fairly large number of participants who were identified as implausible reporters points to inaccuracies in self-reported dietary intakes using food records. Also, the study used an estimated, rather than observed, measure of physical activity for the computation of participants' pER to identify implausible reporters and therefore participants' true daily energy requirement may differ from the one used in this analysis. Future studies should consider using interviewer-assisted 24-hour dietary recalls instead of food records to improve reporting accuracy. Additionally, it is possible that this pilot study may have had limited statistical power, which in turn may explain the lack of significant effects in the present study. It will therefore be critical to test this intervention in a larger sample of participants to determine the true efficacy of the financial incentives intervention on all outcomes. Future studies should also include more heterogeneous samples, test the intervention over a longer period of time, and target overall energy intake and improvements in weight outcomes. This could be achieved by, for example, incentivizing participants for reducing the purchase and consumption of energy-dense foods and sugar-sweetened beverages and by setting specific calorie and weight loss goals. Lastly, future studies should also test different amounts of financial incentives and systematically examine the potential relationship between SNAP participation and coupon usage among subjects.

Conclusion

In summary, providing financial incentives for the purchase of healthy foods and beverages significantly increased daily vegetable intake in an urban sample of middle-aged and older consumers, but only in a subgroup of participants (57%) who were responsive to the intervention. Groups did not significantly differ in their daily energy intakes or weight-related outcomes over the course of the intervention. This suggests that providing financial incentives both for making healthy food choices while at the same time limiting less healthy foods choices may have a greater impact on dietary and weight outcomes than incentivizing healthy food choices alone. Further, consumers who frequently used coupons for their grocery purchases did not differ significantly in BMI, waist circumference, waist-to-height ratio or the level at which their home food environment may be considered ‘obesogenic’ compared to consumers who never used coupons for their grocery purchases. These findings suggest that factors other than grocery coupons use may be associated with increased weight status among at-risk individuals.

Highlights.

Financial incentives can be effective for changing health behaviors.

We tested the effect of incentives for healthy groceries on diet/weight changes.

Incentivized participants significantly increased their daily vegetable intake.

There were no changes in daily energy intake or weight-related outcomes.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the contributions of the staff and students at the Center for Weight and Eating Disorders at the University of Pennsylvania who assisted with this study. The authors' responsibilities were as follows – TVEK: study design, data collection, statistical analysis, interpretation of results, writing of the manuscript; ALB: data collection, interpretation of results, critical revision of manuscript; and RHM: statistical analysis, interpretation of the results, critical revision of manuscript. The authors have no competing interests. This study was funded by the National Institutes on Aging to Penn CMU Roybal P30 Center on Behavioral Economics and Health (P30AG034546).

Financial Support: Funding was received from the National Institute on Aging to Penn CMU Roybal P30 Center on Behavioral Economics and Health (P30AG034546).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Tanja V.E. Kral, Department of Behavioral Health Sciences, University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing; Department of Psychiatry, University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine

Annika L. Bannon, Division of OB/GYN Research, University of Massachusetts Medical School

Reneé H. Moore, Department of Statistics, North Carolina State University

References

- 1.Haff N, Patel MS, Lim R, Zhu J, Troxel AB, Asch DA, et al. The role of behavioral economic incentive design and demographic characteristics in financial incentive-based approaches to changing health behaviors: a meta-analysis. Am J Health Promot. 2015;29(5):314–23. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.140714-LIT-333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.United States Department of Agriculture. Evaluation of the Healthy Incentives Pilot (HIP) Summary of Findings. 2014 http://www.fns.usda.gov/sites/default/files/HIP-Final_Findings.pdf.

- 3.Geliebter A, Ang IY, Bernales-Korins M, Hernandez D, Ochner CN, Ungredda T, et al. Supermarket discounts of low-energy density foods: effects on purchasing, food intake, and body weight. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2013;21(12):E542–8. doi: 10.1002/oby.20484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kumcu A, Kaufman P. Food spending adjustments during recessionary times. 2011 http://www.ers.usda.gov/AmberWaves/September11/Features/FoodSpending.htm.

- 5.Cameron D, Gregory C, Battaglia D. Nielsen Personalizes The Mobile Shopping App If You Build the Technology, They Will Come. Journal of Advertising Research. 2012;52(3):333–338. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Venkatesan R, Farris PW. Measuring and Managing Returns from Retailer-Customized Coupon Campaigns. Journal of Marketing. 2012;76(1):76–94. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Musalem A, Bradlow ET, Raju JS. Who's Got the Coupon? Estimating Consumer Preferences and Coupon Usage from Aggregate Information. Journal of Marketing Research. 2008;45(6):715–730. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goodwin BK. An Analysis of Factors Associated with Consumers Use of Grocery Coupons. Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics. 1992;17(1):110–120. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bawa K, Shoemaker RW. The Effects of a Direct Mail Coupon on Brand Choice Behavior. Journal of Marketing Research. 1987;24(4):370–376. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lopez A, Seligman HK. Online grocery store coupons and unhealthy foods, United States. Prev Chronic Dis. 2014;11:130211. doi: 10.5888/pcd11.130211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Raynor HA, Polley BA, Wing RR, Jeffery RW. Is dietary fat intake related to liking or household availability of high- and low-fat foods? Obes Res. 2004;12(5):816–23. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Campbell KJ, Crawford DA, Salmon J, Carver A, Garnett SP, Baur LA. Associations between the home food environment and obesity-promoting eating behaviors in adolescence. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2007;15(3):719–30. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tak NI, Te Velde SJ, Oenema A, Van der Horst K, Timperio A, Crawford D, et al. The association between home environmental variables and soft drink consumption among adolescents. Exploration of mediation by individual cognitions and habit strength. Appetite. 2011;56(2):503–10. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2011.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lohman T, Roche A, Martorell R. Anthropometric standardization reference manual. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults: executive summary. Expert Panel on the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight in Adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 1998;68(4):899–917. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/68.4.899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ashwell M, Gunn P, Gibson S. Waist-to-height ratio is a better screening tool than waist circumference and BMI for adult cardiometabolic risk factors: systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2012;13(3):275–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2011.00952.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang TT, Howarth NC, Lin BH, Roberts SB, McCrory MA. Energy intake and meal portions: associations with BMI percentile in U.S. children. Obes Res. 2004;12(11):1875–85. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang TT, Roberts SB, Howarth NC, McCrory MA. Effect of screening out implausible energy intake reports on relationships between diet and BMI. Obes Res. 2005;13(7):1205–17. doi: 10.1038/oby.2005.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Institute of Medicine. Dietary reference intakes for energy, carbohydrate, fiber, fat, fatty acids, cholesterol, protein, and amino acids (macronutrients) Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fulkerson JA, Nelson MC, Lytle L, Moe S, Heitzler C, Pasch KE. The validation of a home food inventory. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2008;5:55. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-5-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.United States Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service. U.S. Household Food Security Survey Module: Six-Item Short Form. http://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-us/survey-tools.aspx#six.

- 22.American Institute for Cancer Research and World Cancer Research Fund. Food, Nutrition, Physical Activity and the Prevention of Cancer: A Global Perspective. Washington, D.C.: American Institute for Cancer Research; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abdull Razis AF, Noor NM. Cruciferous vegetables: dietary phytochemicals for cancer prevention. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013;14(3):1565–70. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2013.14.3.1565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Savica V, Bellinghieri G, Kopple JD. The effect of nutrition on blood pressure. Annu Rev Nutr. 2010;30:365–401. doi: 10.1146/annurev-nutr-010510-103954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen ST, Maruthur NM, Appel LJ. The effect of dietary patterns on estimated coronary heart disease risk: results from the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) trial. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2010;3(5):484–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.109.930685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oude Griep LM, Geleijnse JM, Kromhout D, Ocke MC, Verschuren WM. Raw and processed fruit and vegetable consumption and 10-year coronary heart disease incidence in a population-based cohort study in the Netherlands. PLoS One. 2010;5(10):e13609. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dauchet L, Amouyel P, Hercberg S, Dallongeville J. Fruit and vegetable consumption and risk of coronary heart disease: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. J Nutr. 2006;136(10):2588–93. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.10.2588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Toh JY, Tan VM, Lim PC, Lim ST, Chong MF. Flavonoids from fruit and vegetables: a focus on cardiovascular risk factors. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2013;15(12):368. doi: 10.1007/s11883-013-0368-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Slavin JL, Lloyd B. Health benefits of fruits and vegetables. Adv Nutr. 2012;3(4):506–16. doi: 10.3945/an.112.002154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pattison DJ, Harrison RA, Symmons DP. The role of diet in susceptibility to rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review. J Rheumatol. 2004;31(7):1310–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]