Abstract

Unlike most DNA-PKcs deficient mouse cell strains, we show here that targeted deletion of DNA-PKcs in two different human cell lines abrogates VDJ signal end joining in episomal assays. Although the mechanism is not well defined, DNA-PKcs deficiency results in spontaneous reduction of ATM expression in many cultured cell lines (including those studied here) and in DNA-PKcs deficient mice. We considered that varying loss of ATM expression might explain differences in signal end joining in different cell strains and animal models, and we investigated the impact of ATM and/or DNA-PKcs loss on VDJ recombination in cultured human and rodent cell strains. To our surprise, in DNA-PKcs deficient mouse cell strains that are proficient in signal end joining, restoration of ATM expression markedly inhibits signal end joining. In contrast, in DNA-PKcs deficient cells that are deficient in signal end joining, complete loss of ATM enhances signal (but not coding) joint formation. We propose that ATM facilitates restriction of signal ends to the “classical” non-homologous end-joining pathway.

Introduction

VDJ recombination is the molecular mechanism that provides for the adaptive immune response in higher vertebrates; this mechanism assembles immunoglobulin and T cell receptor coding region exons from discrete gene segments via a DNA recombination mechanism that proceeds through DNA cleavage and rejoining (1, 2) (3, 4). Unlike other DNA double strand breaks (DSBs) that can be repaired by three distinct DNA repair pathways (5), DSBs introduced during VDJ recombination are repaired almost exclusively by the classical non-homologous end joining pathway (c-NHEJ) (6).

VDJ recombination is generally studied in two ways: 1) by assessing recombination of episomal substrates introduced into cultured cells that express the RAG endonuclease (7), or 2) by assessing chromosomal VDJ recombination events, either of endogenous immune receptors or of integrated recombination substrates in cultured cells or in developing lymphocytes (8). Whereas episomal substrate assays have defined a clear role for “core” factors of the c-NHEJ pathway (DNA-PKcs, Ku70, Ku86, XRCC4, DNA ligase IV, Artemis, and perhaps XLF) (9, 10), studies of chromosomal VDJ recombination have elucidated additional factors (ATM, 53BP1, H2AX, MRN complex) that facilitate appropriate resolution of RAG-induced chromosomal DSBs (11-15). Although episomal assays are not optimal to study the regulation of VDJ recombination, these assays have historically provided a powerful tool to study the mechanistic basis of many aspects of VDJ recombination.

DNA-PKcs deficiency has been studied extensively in three species (mice, horses, dogs); in all three of these models, DNA-PK activity is completely abrogated (16-18) (19-22). Although two human SCID patients have been reported with DNA-PKcs defects (23, 24), the DNA-PKcs mutations in both were hypomorphic mutations, retaining varying degrees of enzymatic activity and the ability to support VDJ coding end joining. Thus, the impact of complete DNA-PKcs deficiency on VDJ recombination in human cells is limited to one study of the malignant glioblastoma cell strain, MO59J (25). Here we assessed VDJ recombination of episomal substrates in two different human cell strains in which gene targeting was utilized to disrupt DNA-PKcs; in both, signal end joining is substantially impaired. In these cell strains, as has been reported for other DNA-PKcs deficient cell strains and living animals, ATM expression is reduced (26, 27). We considered that varying loss of ATM expression might explain differences in signal end joining in different cell strains and animal models, and we investigated the impact of ATM and/or DNA-PKcs loss on VDJ recombination in cultured human and rodent cell strains. To our surprise, [and at odds with studies of chromosomal VDJ recombination (28, 29)], we found that whereas complete loss of ATM enhances both signal and coding end joining in episomal assays, ectopic expression of ATM inhibits both. Current dogma proposes a role for ATM in stabilizing the RAG post cleavage complex (8), thus ensuring both accurate joining of VDJ associated DSBs in cis, and suppressing translocations. We suggest that insufficient ATM expression in these episomal cellular assays results in a less stable post-cleavage complex, and more rapid release of DSBs resulting in more efficient end joining.

Materials and Methods

Plasmids

The expression constructs for wild type human and murine DNA-PKcs and the human K3753R and D3922A DNA-PKcs mutant constructs have been described (30). The murine D3922A mutant was generated by PCR mutagenesis of a fragment spanning unique BstEII and SpeI restriction sites in a murine DNA-PKcs expression plasmid (31). The following oligonucleotides were used for PCR mutagenesis.

5′BstEII: TATGGCGCCTTGGGTGACCTTCGTGCTC

3′+Not: GGGCGGCCGCTTACATCCAGGGCTCCCA

5′BssHI: ATTGGAGCGCGCCACCTGAACAATTTCATGGTG

3′ BssHI: GTGGCGCGCTCCAATCCCGAGGAG

The fluorescent substrates were generated by flanking RFP (from Ds-Red Express, Clontech) with Cla1 restriction sites using PCR mutagenesis. The resulting Cla1 fragment was subcloned into pJH290, pJH289 (32), or an I-Sce1 substrate (33). PCR mutagenesis was used to flank the RSS or I-Sce1 cassettes with Nhe1 and Age1 restriction sites. These fragments were subsequently subcloned into pECFPN1. In test transfections, for unknown reasons, weak CFP expression was detected in both the 289/RFP/CFP and 290/RFP/CFP substrates (without RFP deletion). However, no CFP expression was detected when substrates containing either 2 or 3 copies of RFP between the RSSs were tested; VDJ recombination levels measured using substrates with 1, 2, or 3 copies of RFP were indistinguishable although the I-Sce1 substrate had a reduced efficiency of RFP deletion when multiple copies of RFP were included. Thus, to reduce background fluorescence in the VDJ assays, 289/RFP/CFP and 290/RFP/CFP substrates included 2 or 3 copies of RFP respectively. RAG expression constructs have been described previously (34). The ATM expression plasmid was the generous gift of Dr. Michael Kastan (35). A GFP-tagged human DNA-PKcs expression vector using the pEF6 expression plasmid that includes the EF1α promoter has been described previously (36). To generate an ATM expression plasmid that includes the EF1α promoter, the ATM cDNA was subcloned into this plasmid.

Cell Culture and Cell Strains

V3 cells were cultured in Minimum Essential Medium (α–MEM, Gibco) with 10% fetal calf serum, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg ml streptomycin, and 10 μg/ml ciprofloxacin. Sf19, 293T, and HCT116 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (Gibco) with 10% fetal calf serum, 2 mM L-glutamine, 0.1 mM non-essential amino acids, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 100U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 10 μg/ml ciprofloxacin. DNA-PKcs deficient embryonic stem (ES) cells (a generous gift of Dr. Fred Alt) were cultured in the medium described above with the addition of β-mercaptoethanol and 103 U/ml ESGRO (EMD Millipore). All cells were maintained at 37°C with 5% CO2.

Methods to derive V3 strains expressing DNA-PKcs have been previously described (30). Briefly, the DNA-PKcs-deficient Chinese hamster ovary cells (V3 cells) were co-transfected with the indicated DNA-PKcs expression plasmid and the pSuper-puro plasmid (Oligoengine), to confer puromycin resistance, using FuGENE 6 (Roche) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Independent, stable transfectants were selected and maintained in complete medium containing 10 μg/ml puromycin.

Cas9 mediated gene disruption

Cas9 targeted gene disruption was performed using methods similar to that reported by Mali et al. (37). Briefly, gRNA's specific for DNA-PKcs, ATM, XRCC4 or XLF were synthesized as 455bp fragments (Integrated DNA Technologies). The synthesized fragments were cloned into pCR2.1 using a TOPO TA cloning kit according to the manufacturers’ instructions (Life Technologies). Cells were transfected with 1 μg gRNA plasmid and 1 μg Cas9 expression plasmid (Addgene). In some cases, cells were co-transfected with 0.2 μg of pcDNA6 (Life Technologies) or pSuper-Puro to confer blasticidin or puromycin resistance. Western blotting was used to identify clones with deletions in each of these factors; in all cases, deletion was also confirmed by PCR amplification that revealed deletions at the target site. gRNAs were designed such that they would target DNA-PKcs, ATM, XRCC4, or XLF in both human and hamster cells. Sequences of the 19mers specific for each factor synthesized into the 455bp fragments are as follows:

DNA-PKcs-2: TGCAACTTCACTAAGTCCA

DNA-PKcs-3: GAAAAAGTACATTGAAATT

ATM: TCTTTCTGTGAGAAAATAC

XRCC4: CCTGCAGAAAGAAAATGAA

XLF: GGCCTGTTGATGCAGCCAT

Clonogenic Survival Assays

V3 transfectants were plated at cloning densities into complete medium containing the indicated dosage of zeocin. After 7 days, cell colonies were stained with 1% (w/v) crystal violet in ethanol, and colony numbers were assessed. Survival was plotted as percentage survival compared to untreated cells.

VDJ recombination assays

Extrachromosomal VDJ recombination assays utilizing the signal joint substrate (pJH201) were performed as described (7). Briefly, cells plated at 20-40% confluency in 60 mm diameter dishes were transiently transfected with 1 μg substrate, 2 μg each of RAG1 and RAG2, and 6 μg of the indicated expression construct (DNA-PKcs, ATM, XLF, or 53BP1) or empty vector using the FuGENE 6 transfection reagent according to the manufacturers’ instructions. For ES cells, 2×106 cells were plated in 60 mm diameter dishes and cells were immediately transfected with 0.5 μg substrate, 2 μg each of RAG1 and RAG2, and 2-8 ug of ATM and/or vector using lipofectamine according to the manufacturers’ instructions. For all cell types, 48 hr after transfection, substrate plasmids were isolated by alkaline lysis and subjected to DpnI digestion for 1 hr. DpnI-digested DNA was transformed into competent DH5α cells (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturers' instructions. Transformed cells were spread onto LB Agar plates containing 100 μg/ml ampicillin only or with 100 μg/ml ampicillin and 22 μg/ml chloramphenicol. The percentage of recombination was calculated as the number of colonies resistant to ampicillin and chloramphenicol divided by the number of colonies resistant to ampicillin.

Extrachromosomal fluorescent VDJ assays were performed on cells plated at 20-40% confluency into 24 well plates in complete medium. Cells were transfected with 0.125 μg substrate, 0.25 μg RAG1 and 0.25 μg RAG2 per well using polyethylenimine (PEI, 1 ug/ml, Polysciences) at 2 ul/1 ug DNA. In experiments with additional expression plasmids, 0.25 μg of the expression plasmid or vector control was included. Cells were harvested 72 hr after transfection and analyzed for CFP and RFP expression by flow cytometry. Flow analyses were performed on FloJo; briefly, in each experiment, live cells were gated based on forward and side scatter plots. The percentage of recombination was calculated as the percentage of live cells expressing CFP divided by the percentage expressing RFP. Data presented represents at least three independent experiments, which each includes triplicate transfections.

Analyses of VDJ recombination intermediates

293T cells were transfected with the 289/RFP/CFP recombination substrate alone, or with indicated RAG expression plasmids. Hirt supernatants were prepared as described previously (7). Hirt supernatant were ligated to 500 pmoles annealed oligonucleotides: top GCTATGTACTACCCGGGAATTCGTG, bottom: CACGAATTCCC. Signal ends were amplified with primer com binations: linker: GGGAATTCGTGCACAGTG and 5'Nhe: CGTCGCCGTCCAGCTCGACC. Signal joints were amplified with 5'Nhe and 3'Age: TACGGTGGGAGGTCTATATA. PCR included forty-five cycles of amplification (94°, 30 seconds, 58°, 1 minute, 68° 1 minute).

Kinase Assays and Immunoblotting

Unless otherwise indicated, whole cell extracts were generated by resuspending cell pellets in solubilization buffer (50 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 50 mM NaF, 5 mM MnCl2, 0.1% Triton X-100, 3 mg/ml DNase I, with protease and phosphatase inhibitors) and incubating at 37ºC for 5 min. For extract kinase reactions, (freeze/thaw) extracts prepared by the method described by Finnie et al (38) were prepared in the following buffer (50 mM NaF, 20 mM Hepes ph 7.8, 450 mM NaCl, 25% glycerol, 0.2 mM EDTA); 100 ug extract was utilized/reaction. 25 ul kinase reactions were incubated for 1 hour at room temperature and the reaction stopped by the addition of SDS-Page buffer and analyzed by immunoblotting using antibodies to XRCC4 (Serotec), RPA32 (Epitomics), DNA-PKcs, phospho-S2056 (Abcam).

Results

Human 293T cells that lack DNA-PKcs are deficient in signal end joining

VDJ recombination has been studied in dozens of DNA-PKcs-deficient non-human cell lines (9, 10, 17-20, 39-47), and in seven different DNA-PKcs deficient animal models (16-18) (19-22). In these varied models, DNA-PKcs deficiency invariably results in profound impairment of coding end joining; however, there are clear differences in the rate of signal end joining with DNA-PKcs deficiency in different species and/or cell strains. Table I presents a comparison of previous studies. Briefly, it is clear that murine lymphocytes and murine cell strains do not absolutely require DNA-PKcs to resolve signal ends (either chromosomally for joining endogenous immune receptor genes or engineered chromosomal substrates or on episomal substrates). Proficient signal joining has been shown both in vivo, with five different DNA-PKcs deficient mouse strains (16-19, 22), and in cellular assays using DNA-PKcs deficient mouse Abelson B cell lines (40), mouse embryonic stem cell lines (17), and mouse embryonic (18) and adult fibroblast lines (31, 45) [although mild deficits are reported in some studies, up to 10 fold (19, 31)]. In contrast, both equine and canine DNA-PKcs deficient lymphocytes have a clear and profound deficit in resolving signal ends at endogenous immune receptor loci (100 fold reduce in dogs, 10,000 fold reduced in horses) (20, 21, 44). Additionally, pronounced signal joining deficits have also been reported using episomal assays in DNA-PKcs deficient hamster and equine cells (20, 39, 42, 43, 47). To date, there is no explanation for these differences.

Table I.

Efficacy of signal end joining in different species and cell types1.

| Endogenous immune receptors |

Cellular Assays | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chromosomal | Episomal | (Ref) | ||

| Human | ND | MO59J/K | (1) | |

| ND | Not reduced | |||

| 293T | this study |

|||

| Reduced | 4-80 fold re- duced |

|||

| HCT116 | this study |

|||

| ND | 10 fold reduced | |||

| Mouse | Most studies report no reduction in joining. Some studies report mild reduction (up to 10 fold). (2-6) |

Abelson B cell lines | (7) | |

| Not reduced | Not reduced | |||

| Embryonic Stem Cells | (3) | |||

| ND | Mildly or not reduced |

|||

| Fibroblasts | (8, 9) | |||

| ND | Mildly or not reduced |

|||

| Hamster | Not available | V3 | (10- 15) |

|

| ND | 2-50 fold re- duced |

|||

| XR-C1 | (16) | |||

| ND | 60 fold reduced | |||

| Irs-20 | (17) | |||

| ND | 10 fold reduced | |||

| Horse | 10,000 fold reduced (15, 18, 19) |

Fibroblasts | (15) | |

| ND | Reduced | |||

Summary of signal end joining in different species and cell types from published literature.

The requirement for DNA-PKcs in coding and signal joining in humans has been less well studied, and there are important differences between DNA-PKcs expression in human and other primates as compared to other vertebrates. DNA-PKcs levels are substantially higher (50 fold) in human cells than in non-primate cells (38); emerging data suggest that DNA-PKcs may have additional roles in human cells that are not important (or required) in other mammalian cells (23, 48).

Only two patients with DNA-PKcs associated SCID have been reported; endogenous VDJ rearrangements were not assessed in these patients. One SCID patient harbored a mild DNA-PKcs mutation that retained full catalytic activity, but which could not activate the downstream nuclease, Artemis (24). The other DNA-PKcs deficient SCID patient harbored much more debilitating (although not null) mutations in DNA-PKcs. One allele encoded a protein that completely lacked enzymatic activity while the other allele encoded a protein that was capable of only minimal catalysis (too low to measure with standard enzymatic assays) (23). This hypomorphic allele was also competent to support reduced levels of coding end joining in episomal assays. Of note, this DNA-PKcs deficient patient presented with a profound defect in neuronal development that resulted in death of the patient at an early age; no similar defects have been observed in the patients with hypomorphic DNA-PKcs mutations or in mice, dogs, or horses that have completely null DNA-PKcs mutations (20, 21, 49).

More recently, Mathieu et al reported two additional patients with the same mild hypomorphic mutation on both alleles; these two patients did not present with overt SCID, but instead presented with inflammatory disease with granuloma and autoimmunity (but with decreased B and T cell numbers) (50). The authors suggest that these phenotypes were associated with defects in AIRE expression, which requires DNA-PKcs for appropriate expression. It is noteworthy that of the six spontaneous VDJ associated SCID mutations described in animals (41, 51-54), three are the result of kinase inactivating mutations in DNA-PKcs, whereas none of the hundreds of VDJ associated SCID patients studied completely lacks DNA-PK activity. For this reason, we have long postulated that a completely null DNA-PKcs mutation would be lethal in humans (23, 52).

Four human cell lines have been described that lack DNA-PKcs. VDJ assays were not performed on two patient derived DNA-PKcs deficient cell strains. A targeted disruption of DNA-PKcs in the HCT116 colorectal carcinoma cell strain revealed pronounced telomere shortening and DNA repair deficits, but VDJ recombination was not studied (48). Lieber and colleagues demonstrated that the human glioblastoma cell strains MO59J (DNA-PKcs deficient) and MO59K (DNA-PKcs proficient) are similarly proficient in signal end joining (25); however, recombination levels were relatively low, probably because the MO59J cell strain is particularly recalcitrant to transfection (55). In summary, there is a paucity of experimental data on the impact of a DNA-PKcs deficiency in humans or human cell lines.

To generate additional DNA-PKcs-deficient human cell lines that would be suitable for episomal assays, we utilized the Cas9/CRISPR-mediated gene targeting technique to disrupt DNA-PKcs in SV40-transformed human embryonic kidney 293T cells (37). Two different CRISPR gRNA encoding constructs were co-transfected with a Cas9 expression plasmid. Individual clones were isolated and expanded. DNA-PKcs expression was assessed by immunoblotting. Two clones were selected, one that lacked DNA-PKcs protein and one that maintained normal levels of DNA-PKcs expression. In vitro kinase assays were performed to assess DNA-PKcs expression and function (Fig. 1A). Clone 7 lacks DNA-PKcs expression (top panel), and in vitro phosphorylation of known DNA-PKcs targets (DNA-PKcs autophosphorylation and XRCC4, both induced by linear DNA; and RPA34, induced by gapped linear DNA) is defective in these cells. DNA-PKcs deficient 293T cells grow substantially slower than wild type cells (Supplementary Fig. 1). For comparison, 293T cells lacking ATM, XRCC4 and XLF were also established. Whereas 293T cells deficient in both XLF and XRCC4 grow similarly to wild type cells, the DNA-PKcs deficient and ATM deficient cells grow substantially slower. Sensitivity of cells deficient in both XRCC4 and XLF to agents that induce DSBs is more pronounced than for cells deficient in either DNA-PKcs or ATM.

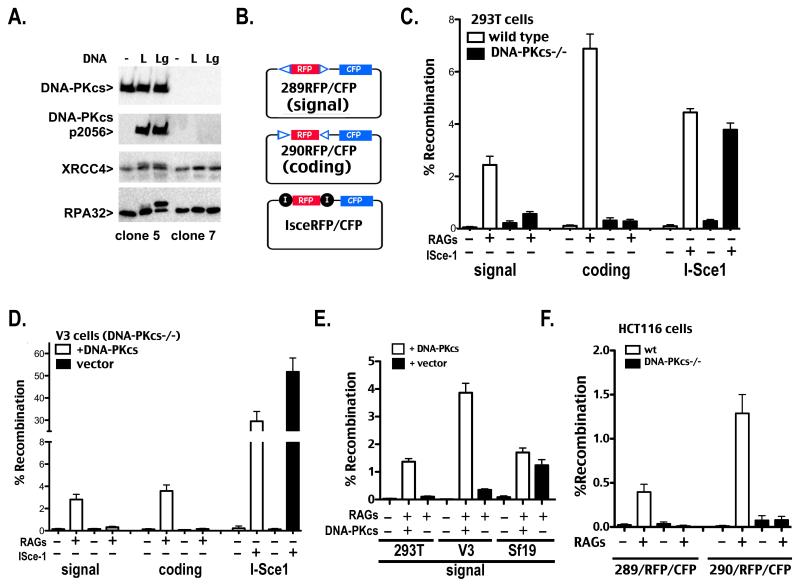

Figure 1. Human 293T cells that lack DNA-PKcs are severely deficient in signal end joining.

A. In vitro kinase assays were performed as described in Methods. Briefly, DNA-PK was not activated (−), activated with linear DNA (L), or activated with linear DNA that includes a single stranded gap (Lg). Kinase reactions were analyzed by western blotting using antibodies specific for DNA-PKcs, phospho-2056 DNA-PKcs, XRCC4, or RPA32. B. Schematic of plasmid VDJ recombination substrates used to detect signal joints (top), coding joints (middle), or I-Sce1 DSB-induced deletion (bottom) are depicted. C and D. Wild type and DNA-PKcs-deficient 293T (C) or V3 (D) cells were transfected with the indicated recombination substrate as well as RAG1 and RAG2 or an I-Sce1 expression construct as specified. Cells were analyzed by flow cytometry 72 hr after transfection and the percentage of recombination was calculated as the percentage of live cells expressing CFP divided by the percentage expressing RFP. Error bars represent the standard error of the means. E. DNA-PKcs-deficient 293T, V3, or Sf19 cells were transfected with indicated recombination substrates, RAG1 and RAG2, and the DNA-PKcs expression construct as specified. Cells were analyzed by flow cytometry as in C and D. F. Wild type and DNA-PKcs-deficient HCT116 cells were transfected with the indicated recombination substrate as well as RAG1 and RAG2 expression constructs as specified. Cells were analyzed by flow cytometry 72 hr after transfection and the percentage of recombination was calculated as the percentage of live cells expressing CFP divided by the percentage expressing RFP. Error bars represent the standard error of the means.

Several VDJ recombination substrates were developed in which two pairs of recombination signal sequences are separated by the red fluorescent protein (RFP) coding sequence (Fig. 1B and Supplementary Fig. 2). These substrates provide an internal control (RFP expression) for plasmid uptake and nuclear localization in the transfected cells. Additionally, they include the SV40 origin of replication, and are thus efficiently replicated episomally in all primate cell strains; it has been reported that this origin replicates to very low copy number in rodent cells (56). VDJ recombination of the substrate results in deletion of RFP and subsequent expression of cyan fluorescent protein (CFP). Substrates that allow assessment of either coding or signal joining as well as I-Sce1-mediated deletion of RFP were prepared.

Proficient coding end joining, signal end joining, and I-Sce1 joining are robustly detected by flow cytometry (Fig. 1C) or by fluorescent microscopy (Supplementary Fig. 2) in 293T cells that express DNA-PKcs. As expected, no coding end joining is detected in 293T cells lacking DNA-PKcs; however, 293T cells that lack DNA-PKcs also have a substantial defect in signal end joining (4.4 fold decreased in the clone presented). Defective signal end joining was observed in three independent DNA-PKcs deficient 293T cell clones (4-80 fold reduced, data not shown). Rejoining of I-Sce1-mediated breaks occurs proficiently in both cell lines because I-Sce1 breaks are not restricted to c-NHEJ and, in the absence of DNA-PKcs, can be joined via a-NHEJ (33). The RFP/CFP substrates were also tested in V3 transfectants (DNA-PKcs deficient CHO cells) that stably express DNA-PKcs or vector controls. V3 cells have a clear deficit in both signal and coding end joining in the fluorescent assay as we and others have shown previously using the conventional episomal assay (43, 46, 47). In contrast, I-Sce1 joining (mediated by alternative end joining) is remarkably proficient in V3 cells (Fig. 1D). To confirm that the observed VDJ-related c-NHEJ deficits in 293T cells could be attributed to DNA-PKcs deletion (and not off-target effects of Cas9 expression), complementation experiments were performed. Transient co-expression of wild type DNA-PKcs restores both coding (not shown) and signal end joining in the DNA-PKcs-deficient 293T cells (Fig. 1E). To provide a direct comparison of signal end joining in different DNA-PKcs deficient cell types, transient complementation signal end joining experiments were also performed with the fluorescent substrate in V3 cells and Sf19 SCID mouse fibroblasts. As shown above, V3 cells have a substantial signal end-joining deficit that is reversed by transient expression of DNA-PKcs (Fig 1E). In contrast, Sf19 SCID mouse fibroblasts support substantial signal joining with or without transient expression of DNA-PKcs, in good agreement with decades of research studying VDJ recombination in DNA-PKcs deficient mice and mouse cell lines (16-19, 22). The RFP/CFP substrates were also tested in DNA-PKcs-deficient HCT116 cells. Although the transfection efficiency was much lower (1-10%) than in 293T cells (~80%) a significant signal end-joining defect (>10 fold) was also apparent (Fig. 1F). We attempted to assess signal joining in the MO59J cell lines analyzed previously; the poor transfection of these cells precluded this analysis. In sum, we show that DNA-PKcs is required for signal end joining in two different human cell lines; in contrast, using the same assay, DNA-PKcs deficient mouse fibroblasts are proficient in joining signal ends.

Signal end joining deficits in V3 and 293T cells cannot be compensated for by ATM or by factors that have been reported to be functionally redundant with DNA-PKcs

We next focused on utilizing this robust episomal assay to try to address why these three cell strains (DNA-PKcs deficient 293T, V3, and Sf19) vary in their dependence on DNA-PKcs to facilitate signal end joining. We first considered that DNA-PKcs-deficient V3 and 293T cells do not resolve signal ends because they lack sufficient expression of a factor that functions to join signal ends in other cell types. We considered ATM (or its targets) as strong candidates for several reasons. First, many DNA-PKcs deficient cell strains have spontaneously reduced expression of ATM (26, 27). The human DNA-PKcs deficient cell strains utilized here also express markedly reduced ATM expression (Fig. 2A). In DNA-PKcs−/− 293T cells, ATM expression is reduced by more than 4 fold. V3 cells show only slightly reduced ATM levels compared to parental cell strain AA8.

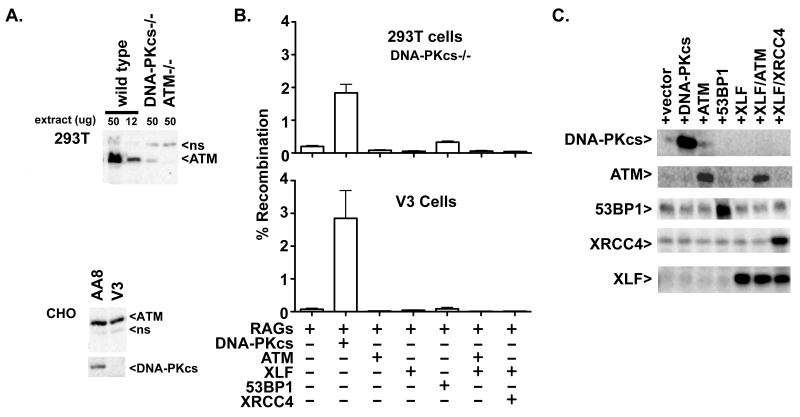

Figure 2. Signal end joining deficits in V3 and 293T cells cannot be compensated for by expression of factors that have been reported to be functional redundant with DNA-PKcs.

A. Immunoblot analyses of ATM and DNA-PKcs expression in human 293T cells and in CHO cell strains AA8 and V3. Non-specific bands (ns) recognized by the ATM antibody in 293T and CHO cells serve as a loading controls, so that the same low percentage gel required to separate the large ATM and DNA-PKcs proteins. Whole cell extracts from several V3 clones were also analyzed to illustrate clonal variation of ATM expression that is independent of DNA-PKcs complementation. B. Top Panel. Recombination percentage of the signal joint substrate 289/RFP/CFP in DNA-PKcs deficient 293T cells transiently expressing RAG proteins and either DNA-PKcs, ATM, XLF 53BP1, XLF and ATM or XLF and XRCC4. Cells were analyzed by flow cytometry as in Fig. 1. Bottom Panel. Recombination percentage of the signal joint substrate pJH201 in V3 cells transiently expressing RAG proteins and either DNA-PKcs, ATM, XLF 53BP1, XLF and ATM or XLF and XRCC4. Error bars represent the standard error of the means. C. DNA-PKcs deficient 293T cells were transfected with the 289/RFP/CFP recombination substrate as well as RAG1 and RAG2 expression constructs and additional expression constructs encoding DNA-PKcs, ATM, 53BP1, XLF, XRCC4, or vector as specified. Cells were harvested 72 hours later; whole cell extracts were analyzed by immunoblotting as indicated.

Another reason to consider ATM as a potential “missing” factor is that there are recent reports establishing that DNA-PKcs is functionally redundant with both ATM and XLF; moreover, XLF is itself functionally redundant with ATM as well as with 53BP1 and H2AX (29, 40, 57-60). XLF, XRCC4, 53BP1, and H2AX are all targets of ATM and/or DNA-PK. Since DNA-PK, 53BP1, H2AX, and XLF (with XRCC4 in XRCC4/XLF filaments) have all been suggested to facilitate DNA end bridging (61-64), we considered that the pronounced deficit in signal end joining in V3 and 293T cells might be explained by a lack of one of these “bridging” factors. Thus, additional signal joint assays were performed in V3 and DNA-PKcs-deficient 293T cells where ATM, XLF, XRCC4 and XLF, and 53BP1 were co-expressed in transient assays. None of these factors increased the level of signal joining (Fig. 2B), although each factor is abundantly expressed in transient assays (Fig. 2C). We conclude that defective signal end joining in 293T and V3 cells is not due to the lack of expression of ATM, 53BP1, or XRCC4/XLF filaments.

ATM deficiency results in a hyper VDJ recombination phenotype in c-NHEJ proficient cells and restores signal end joining in DNA-PKcs deficient cells

Unlike most DSBs that can be repaired by classical or alternative NHEJ or by homologous recombination, RAG-induced DSBs require c-NHEJ for efficient repair (6). The mechanism by which RAG-induced DSBs are restricted to the c-NHEJ pathway is poorly understood. Since certain RAG2 mutants defined by Roth and colleagues are deficient in this process, it has been suggested that the RAG endonuclease interacts with other factor(s) that facilitate restriction of RAG-induced DSBs to the c-NHEJ pathway (34, 65, 66). We considered that the difference between DNA-PKcs-deficient cells that are proficient versus deficient in signal end joining is not because the deficient cells lack a joining factor, but because the proficient cells lack a factor that restricts RAG-induced breaks to c-NHEJ. Elegant studies initially from Sleckman and colleagues and later from other investigators demonstrate that ATM deficiency destabilizes the RAG post-cleavage complex (PCC) (14, 66-69). In the absence of ATM, RAG-induced DSBs promote genomic instability and tumorigenesis (70-73), perhaps because the DNA ends are less well restricted (to c-NHEJ) and join inappropriately. Therefore, it seems intuitive that the RAG post cleavage complex would be involved in “shepherding” RAG-induced DSBs into c-NHEJ. Even more, ATM would be an attractive candidate factor involved in restricting RAG-induced breaks into cNHEJ, because many DNA-PKcs deficient cell lines as well as splenocytes from SCID mice spontaneously display markedly reduced ATM expression (26, 27). If ATM helps restrict RAG DSBs to c-NHEJ, variable degrees of spontaneous reduction/loss of ATM in DNA-PKcs deficient cells and in SCID mice might explain more proficient signal end joining in different cell types and in different animals.

Cas9/CRISPR-mediated gene targeting was utilized to disrupt ATM; ATM-deficient hamster V3 cells (either expressing human wild type DNA-PKcs, or vector control) were isolated. V3 ATM deficient cells display expected hypersensitivity to agents that induce DSBs (Supplementary Fig. 3). Although 293T cells that lack ATM were readily obtained, we were not successful in generating 293T cells deficient in both DNA-PKcs and ATM. Four independent ATM-deficient V3 clones (expressing wild type DNA-PKcs) and two independent ATM-deficient 293T clones were assessed for VDJ recombination proficiency. Results for one clone for each cell type are presented (Fig. 3A and 3B), but all clones tested gave analogous results. ATM deficiency in 293T cells and in DNA-PKcs complemented V3 cells results in a hyper VDJ recombination phenotype, which results in a significant increase in coding joining and an even more dramatic increase in signal joining. In contrast, ATM deficiency does not have a substantial effect on I-Sce1 joining in V3 cells although there is a modest affect in 293T cells. Remarkably, ATM deficiency in DNA-PKcs-deficient V3 cells substantially rescues signal end joining; signal end-joining in ATM-deficient V3 cells is roughly equivalent to signal end-joining in DNA-PKcs complemented V3 cells. These results were confirmed in V3 cells with the standard Gellert assay (Supplementary Fig. 4). In contrast, coding end joining does not differ substantially in DNA-PKcs-deficient V3 cells with or without ATM. Thus, ATM deficient V3 cells resolve VDJ intermediates (both coding and signal ends) similarly to SCID mouse cells.

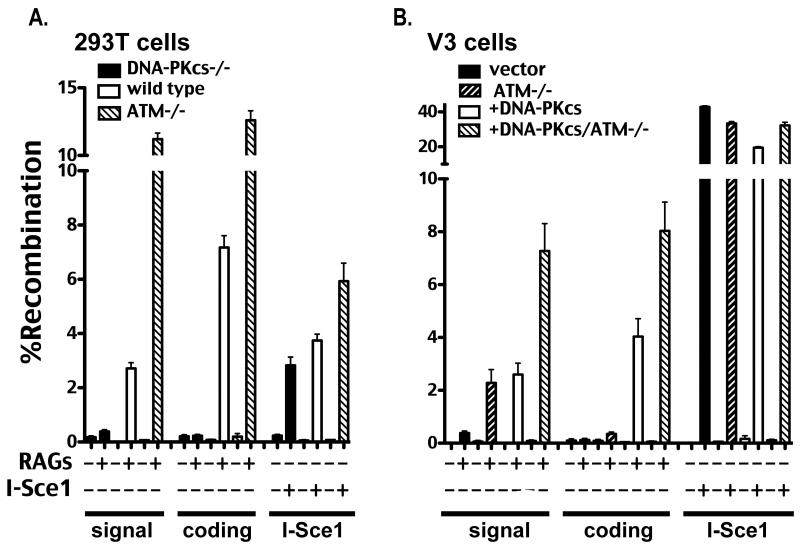

Figure 3. ATM deficiency results in a hyper VDJ recombination phenotype in c-NHEJ proficient cells and restores signal end joining in DNA-PKcs-deficient cells.

A. Wild type, DNA-PKcs-deficient, and ATM-deficient 293T cells were transfected with the indicated recombination substrate as well as RAG1 and RAG2 or an I-Sce1 expression construct as specified. Cells were analyzed by flow cytometry as in Fig. 1. B. V3 transfectant strains expressing no DNA-PKcs (vector) or wild type DNA-PKcs (+DNA-PKcs) as well as isogenic strains deficient in ATM, (ATM−/−) and (+DNA-PKcs/ATM−/−) respectively, were transfected with the indicated recombination substrate as well as RAG1 and RAG2 or an I-Sce1 expression construct as specified. Cells were analyzed by flow cytometry as in Fig. 1.

To confirm that the observed hyper-recombination phenotype observed in ATM deficient cells was the result of ATM deletion (and not off-target effects of Cas9 expression), complementation experiments were performed. In these experiments, the only variable between different transfections is a variable amount of the ATM plasmid or vector control. Whereas ATM expression reduces signal joining in ATM deficient 293T cells in a titratable manner, empty vector has no effect (Fig. 4A). Increasing dosage of the ATM expression plasmid increases expression of ATM, while lowering signal joining, but nei ther RAG1 nor RAG2 expression is impacted by co-transfection of the ATM expression plasmid (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4. Signal joining is reduced in ATM deficient cells by ectopic ATM expression.

A. Left panel. Recombination percentage of signal joint substrate 289/RFP/CFP in 293T ATM deficient cells expressing ectopic ATM or vector control. Right Panel. Immunoblot analyses of ATM, RAG1, and RAG2 ectopic expression in ATM deficient 293T cells, 72 hours after transfection of indicated plasmids. B. Recombination percentage of the signal joint substrate 289/RFP/CFP in V3 transfectant strains expressing no DNA-PKcs (vector) or wild type DNA-PKcs (+DNA-PKcs) as well as isogenic strains deficient in ATM, (ATM−/−) and (+DNA-PKcs/ATM−/−) respectively, transiently expressing RAG proteins and either DNA-PKcs, the catalytically inactive D3922A DNA-PKcs mutant (D>A), ATM, or 53BP1. Cells were analyzed by flow cytometry as in Fig. 1.

Additional episomal assays were conducted using the four V3 cell strains including transient expression of ATM, DNA-PKcs, and 53BP1 (Fig. 4C). In DNA-PKcs-complimented cells (with or without ATM), expressing additional DNA-PKcs (wild type or the enzymatically inactive D3922A mutant) modestly inhibits signal end joining. In DNA-PKcs-complemented, ATM deficient cells, ATM more dramatically inhibits signal end joining. In contrast, co-transfection of a plasmid encoding another large DNA repair protein (53BP1) has little affect on signal end joining. In DNA-PKcs-deficient cells (with or without ATM), wild type DNA-PK substantially reverses signal end joining deficits. Thus, either ATM or DNA-PKcs can restrict signal ends to c-NHEJ. In DNA-PKcs/ATM deficient cells, signal joining is markedly reduced by transient expression of either catalytically inactive DNA-PKcs or by ATM. Similarly, co-transfection of ATM inhibits signal joining in the conventional (pJH201) assay (Supplementary Fig. 4). Co-transfection of ATM with kinase dead DNA-PKcs did not further reduce the level of signal end joining. The fact that ectopic ATM expression reverses the hyper-recombination phenotype of both 293T and V3 ATM-deficient cells strongly suggests that this phenotype is the result of ATM deficiency.

ATM deficiency results in increased joining, but not increased cleavage

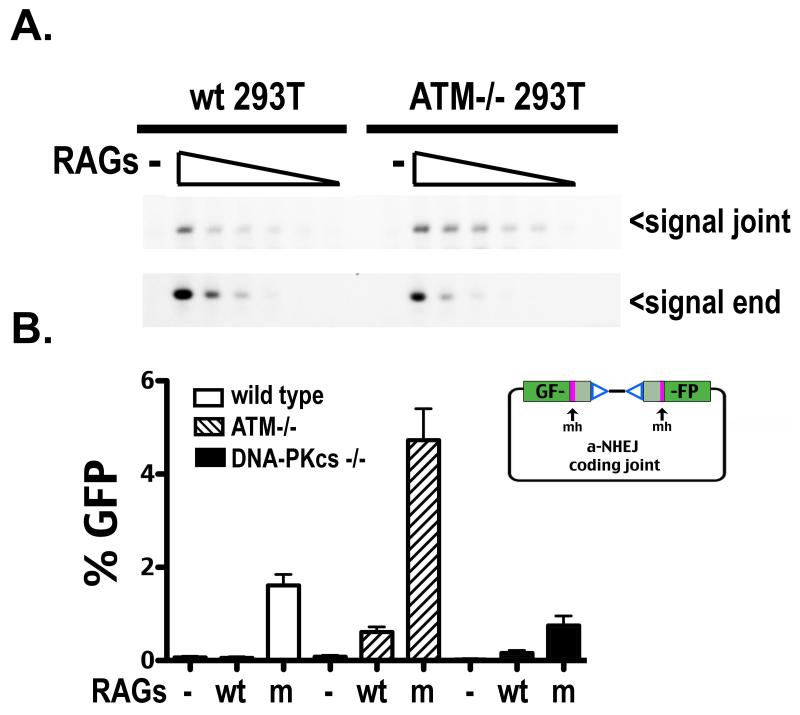

Bassing and colleagues have observed increased cleavage at endogenous immune receptor loci in ATM deficient cells; this hyper cleavage effect was at least partially attributed to loss of ATM induced suppression of RAG transcription (74, 75). To ascertain whether the hyper recombination phenotype associated with ATM deficiency in these episomal assays results from increased cleavage or increased release of DSBs, persistence of recombination intermediates was assessed by LMPCR. Hirt supernatants were prepared from transient transfections and linker ligated; five fold dilutions of these input DNAs were PCR amplified to detect either signal joints or signal ends. Consistent with the increased signal joining observed in all ATM−/− cell types tested, signal joints can be detected with 5-fold less input DNA as compared to wild type cells; a concomitant, modest reduction of unrepaired signal ends is also apparent in ATM deficient cells as compared to wild type cells (Fig. 5A), suggesting that ATM deficiency results in increased release (and joining) as opposed to increased cleavage.

Figure 5. ATM deficiency results in increased joining, but not increased cleavage.

A. Limiting dilution PCR (top panel) or LMPCR (bottom panel) of serial 5 fold dilutions of oligonucleotide ligated Hirt supernatants prepared from 293T cells proficient (left) or deficient (right) in ATM, transfected with no RAGS or wild type RAGS. Arrows depict PCR products detecting signal joints or signal ends. B. Wild type, ATM-deficient, and DNA-PKcs-deficient 293T cells were transfected with dsRED express and either RAG1 and RAG2, or RAG1 and mutant RAG2, and a substrate (depicted in right panel) to detect VDJ coding joints that delete 8 or 9 bp from each end and are joined at a region of microhomology, and thus likely represent joints mediated by a-NHEJ. Cells were analyzed by flow cytometry as in Fig. 1.

To further explore the basis of hyper recombination in ATM deficient cells, a novel VDJ recombination substrate designed to measure repair of RAG DSBs by a-NHEJ was utilized (34). The alt-VDJ substrate separates the GFP open reading frame with a pair of RSSs; repair of RAG induced DSBs at the termini of the two GFP halves only results in an intact GFP open reading frame if joining deletes 8/9bp from the two ends and joining occurs at a sequence of 9bp of microhomology. It has been shown that the “hyper” RAG2 mutant described by Roth and colleagues (34) allows significantly more joining at the 9bp region of microhomology than wild type RAGs; this finding was readily recapitulated in 293T cells (Fig. 5B). Although alt-VDJ was not detected in ATM proficient cells with wild type RAG2, alt-VDJ was readily detected using wild type RAGs in ATM deficient cells, consistent with increased release of VDJ intermediates in the absence of ATM. Moreover, alt-VDJ detected using the RAG2 mutant was markedly enhanced in ATM deficient cells. We conclude that increased release of DSBs (allowing some DSBs to be repaired by the a-NHEJ pathway) contributes to the increased recombination levels observed in ATM deficient 293T cells.

In addition, in an effort to understand what pathway contributes to signal end repair in ATM deficient V3 cells, recombined signal joints (from the standard assay, Supplementary Fig. 4) were isolated sequenced. As expected, although signal joints isolated from DNA-PKcs deficient cells (either ATM proficient or deficient) are markedly less precise than those isolated from DNA-PKcs complemented V3 cells, there are no significant differences in DNA end trimming or microhomology use when comparing ATM proficient or deficient cells (Table II). Although a-NHEJ may contribute to increased joining observed in ATM−/− cells (as evidenced by Fig. 5B), the high percentage of precise signal joints is most consistent with c-NHEJ mediated joining of the majority of RAG-induced DSBs in DNA-PKcs proficient, ATM deficient cells.

Table II.

Signal joints isolated from ATM proficient or deficient cells are indistinguishable2.

| # Sequences |

% Perfect Joints |

Deletion range |

Deletion (median) |

% micro homology |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNA-PKcs+ | 48 | 89.6% (43/48) |

1-30 | 5 | 3/5 |

| DNA-PKcs+/ ATM−/− |

59 | 94.9% (56/59) |

2-12 | 2 | 0/3 |

| vector | 46 | 69.6% (32/46) |

1-151 | 9 | 9/14 |

| vector/ ATM−/− |

59 | 74.6% (44/59) |

1-140 | 5 | 3/15 |

~50 recombined pjH201 substrates with signal joints from assays depicted in Sup. Fig. 4.

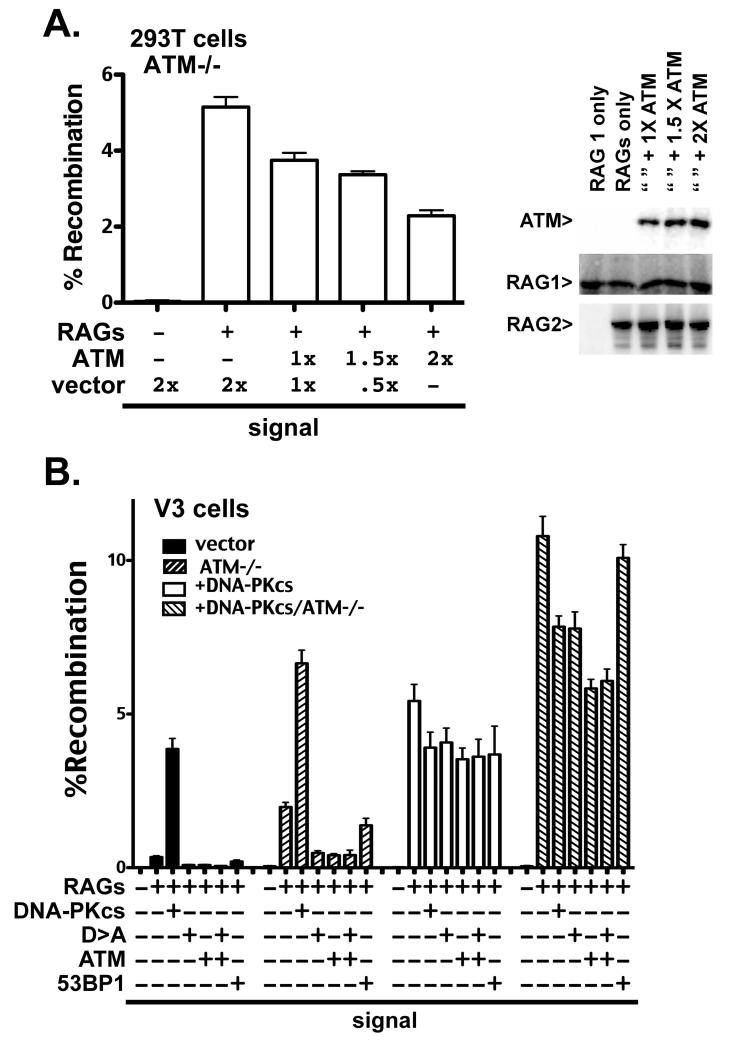

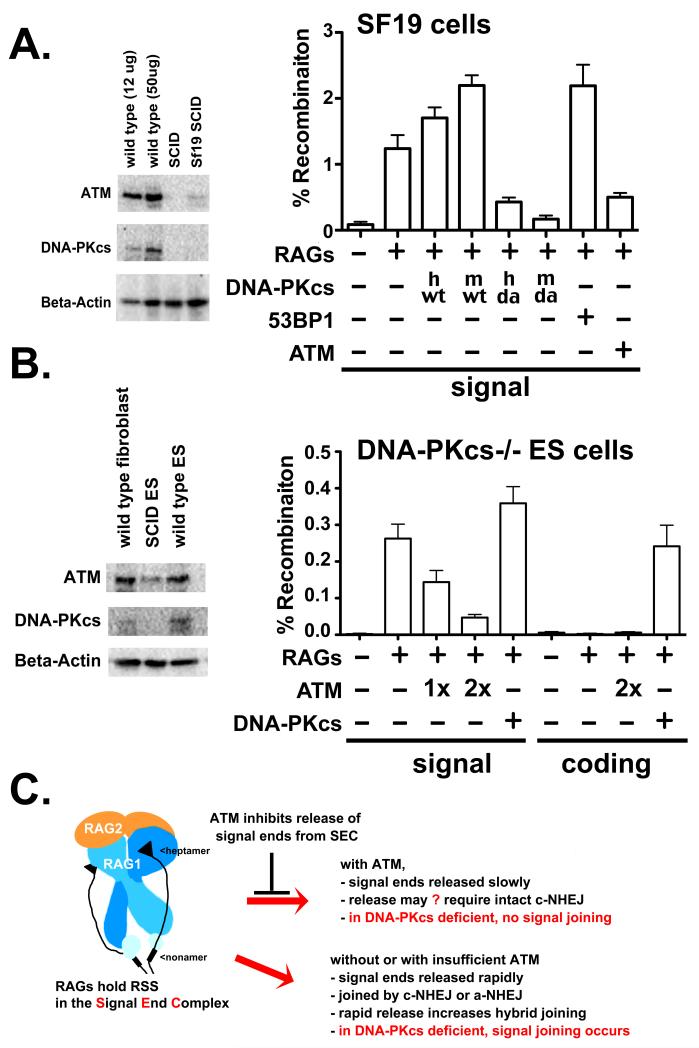

ATM over-expression suppresses signal joining in DNA-PKcs deficient mouse fibroblasts and ES cells

These data would be consistent with a hypothesis that loss of ATM in DNA-PKcs-deficient cells correlates with efficacy of signal end joining and we next considered whether ATM might be able to suppress signal joining in DNA-PKcs-deficient cells that are proficient at signal joining. We addressed this using two different DNA-PKcs deficient, non-transformed cell strains (SCID mouse fibroblasts and DNA-PKcs deficient murine ES cells); both cell strains have reduced ATM levels as compared to wild type controls (left panels, Fig. 6A and 6B). ATM expression in both DNA-PKcs−/− cell types is reduced compared to wild type controls. In Sf19 cells, both human and mouse wild type DNA-PKcs modestly increase signal joining, whereas catalytically inactive DNA-PKcs inhibits signal joining (Fig. 6A). Co-transfection of ATM markedly reduces signal joining in mouse SCID fibroblasts, whereas co-expression of 53BP1 does not. In fact, transient expression of ATM in SCID mouse cells results in a 4 fold deficit in signal joining that is similar to the deficits observed in DNA-PKcs deficient 293T cells (~4 fold) or V3 cells (~7 fold). The CMV promoter controls CFP and RFP expression in the fluorescent substrates as well as ATM expression in the plasmids utilized thus far; however the CMV promoter functions poorly in ES cells. Thus, the pJH201 substrate was used to assess signal joining in ES cells. Additional ATM expression plasmids using the EF1α promoter were constructed for this experiment. Ectopic ATM expression suppresses signal joining in DNA-PKcs deficient mouse ES cells, in a titratable manner. In contrast, ectopic DNA-PKcs expression, slightly enhances signal joining, and complements the deficit in coding end joining as expected. Altogether, these data are consistent with a model whereby ATM restricts signal ends to the c-NHEJ pathway.

Figure 6. ATM over-expression suppresses signal joining in SCID mouse fibroblasts and DNA-PKcs deficient murine ES cells.

A. Left panel. Immunoblot analyses for ATM, DNA-PKcs or Beta-Actin expression of 12-50 μg of whole cell extracts from wild type or SCID ear fibroblasts, or the murine SCID fibroblast cell strain, Sf19. Right panel. Recombination percentage of the signal joint substrate 289/RFP/CFP in Sf19 cells transiently expressing RAG proteins and either no DNA-PKcs, human or mouse, wild type or mutant DNA-PKcs (vector, hwt, mwt, hD3922>A, mD3922>A,), 53BP1 or ATM. Cells were analyzed by flow cytometry as in Fig. 1. B. Left panel. Immunoblot analyses for ATM, DNA-PKcs or Beta-Actin expression of 50 μg whole cell extracts from wild type mouse fibroblasts, and wild type or DNA-PKcs deficient murine ES cells strains. Right panel. Recombination percentage of the signal joint substrate pJH201 or coding joint substrate pJH290 in DNA-PKcs deficient murine ES cells transiently expressing RAG proteins and varying levels of ATM, vector control, or DNA-PKcs as indicated. C. Proposed model. SEC structure is based on studies of Ru et al. (77).

Discussion

Here we show in episomal VDJ recombination assays that deletion of ATM results in increased VDJ recombination rates, and deletion of ATM in DNA-PKcs-deficient cells substantially reverses signal joining deficits. However, studies from the Alt, Sleckman, and Nussensweig laboratories have established that loss of ATM and DNA-PKcs markedly potentiate chromosomal VDJ end joining deficits (28, 29). How can this paradox be clarified? The most plausible explanation is that these earlier elegant reports studied ATM/DNA-PKcs deficiency primarily on chromosomal rearrangements in lymphocytes. Since this involves assessment of a single event in each cell, “hyper” joining would be precluded. Clearly, deficiency in both DNA-PK and ATM results in chromosomal repair deficits more pronounced than with either deficiency alone. This is consistent with data presented here showing that cells deficient in both DNA-PKcs and ATM are more sensitive to drugs that induce chromosomal DSBs (Supplementary Fig. 3) than cells deficient in either DNA-PKcs or ATM alone. Although there is no question that it is more relevant to study VDJ recombination in developing lymphocytes than in cultured, non-lymphoid cell strains, because of the many levels of regulation that are imposed during antigen receptor gene assembly in lymphocytes, use of robust episomal assays can provide important mechanistic insight(s) into specific steps of this interesting and important facet of immune system development. Clearly human cells have a unique dependence on the DNA-PK complex (23, 48); delineation of the basis for this unique dependence will have to emerge from cell culture approaches like these.

Emerging structural studies provide a wealth of insight into how the RAG complex precisely targets 12RSS and 23RSS to perform its function in immune repertoire development (76, 77). These studies also reveal the structure of the RAG signal end complex, which has long been known to be particularly stable and hypothesized to sequester signal ends post-cleavage (78, 79). The data presented here suggest a model whereby ATM stabilizes the signal end complex (Fig. 6C).

We have struggled to explain differences in signal end joining deficits in different animal models of DNA-PKcs deficiency. As discussed above, most DNA-PKcs deficient cells spontaneously reduce ATM expression levels (Fig. 2A and 6A and (26)). Data presented here showing that ATM expression is required to fully restrict RAG induced DSBs to c-NHEJ provides a potential explanation for these inconsistencies (Fig. 6C). Thus, in the absence of DNA-PKcs, signal joining occurs efficiently only if ATM levels are insufficient to maintain the signal end complex. What is not clear is whether this is a direct effect of ATM, or the consequence of phosphorylation by ATM of one or more of its downstream targets. Previous studies have provided evidence that many factors that promote VDJ joining (H2AX, 53BP1, Artemis) are also targets of ATM’s kinase activity (11, 13, 71, 80, 81). The challenge will be to decipher which (if any) of these phosphorylations directly promotes restriction of RAG induced DSBs to the c-NHEJ pathway.

Work from Sleckman and colleagues provide compelling evidence that ATM is required to stabilize the RAG post cleavage complex (15, 67). Undoubtedly, the hyper recombination phenotype we observe is actually a different sequellae of the same activity. Studies with enzymatically inactive DNA-PKcs suggest an overlapping role for DNA-PKcs and ATM in maintaining the RAG post cleavage complex, and that (at least DNA-PKcs) has a structural role, independent of its catalytic activity. The new finding presented here is that signal end joining is also impacted by loss of ATM. Our studies suggest that release of both signal and coding ends is dysregulated in ATM deficient cells; it seems that dysregulation of coding and signal end release offers a good explanation for increased hybrid joining in ATM deficient cells (Fig. 6C). It is well established that coding end joining proceeds more rapidly than signal end joining (82); we suggest that the exquisite preference to join coding end to coding end and signal end to signal end may be a reflection of timed release of ends: coding ends quickly, signal ends more slowly. If coding and signal ends are released concurrently, the likelihood of hybrid joining may increase.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Martin Gellert, Kefei Yu, and Mauro Modesti for their careful review of this manuscript and for their many thought-provoking suggestions to our research projects.

Footnotes

This work was supported by Public Health Service grant AI048758 (KM).

References

- 1.Lieber MR, Yu K, Raghavan SC. Roles of nonhomologous DNA end joining, V(D)J recombination, and class switch recombination in chromosomal translocations. DNA repair. 2006;5:1234–1245. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2006.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gellert M. V(D)J recombination: RAG proteins, repair factors, and regulation. Annual review of biochemistry. 2002;71:101–132. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.71.090501.150203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matthews AG, Oettinger MA. RAG: a recombinase diversified. Nature immunology. 2009;10:817–821. doi: 10.1038/ni.1776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schatz DG, Spanopoulou E. Biochemistry of V(D)J recombination. Current topics in microbiology and immunology. 2005;290:49–85. doi: 10.1007/3-540-26363-2_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shibata A, Jeggo PA. DNA double-strand break repair in a cellular context. Clinical oncology. 2014;26:243–249. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2014.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roth DB. V(D)J Recombination: Mechanism, Errors, and Fidelity. Microbiology spectrum. 2014:2. doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.MDNA3-0041-2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hesse JE, Lieber MR, Gellert M, Mizuuchi K. Extrachromosomal DNA substrates in pre-B cells undergo inversion or deletion at immunoglobulin V-(D)-J joining signals. Cell. 1987;49:775–783. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90615-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Helmink BA, Sleckman BP. The response to and repair of RAG-mediated DNA double-strand breaks. Annual review of immunology. 2012;30:175–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-030409-101320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taccioli GE, Rathbun G, Oltz E, Stamato T, Jeggo PA, Alt FW. Impairment of V(D)J recombination in double-strand break repair mutants. Science. 1993;260:207–210. doi: 10.1126/science.8469973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pergola F, Zdzienicka MZ, Lieber MR. V(D)J recombination in mammalian cell mutants defective in DNA double-strand break repair. Molecular and cellular biology. 1993;13:3464–3471. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.6.3464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Helmink BA, Tubbs AT, Dorsett Y, Bednarski JJ, Walker LM, Feng Z, Sharma GG, McKinnon PJ, Zhang J, Bassing CH, Sleckman BP. H2AX prevents CtIP-mediated DNA end resection and aberrant repair in G1-phase lymphocytes. Nature. 2011;469:245–249. doi: 10.1038/nature09585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Helmink BA, Bredemeyer AL, Lee BS, Huang CY, Sharma GG, Walker LM, Bednarski JJ, Lee WL, Pandita TK, Bassing CH, Sleckman BP. MRN complex function in the repair of chromosomal Rag-mediated DNA double-strand breaks. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2009;206:669–679. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Difilippantonio S, Gapud E, Wong N, Huang CY, Mahowald G, Chen HT, Kruhlak MJ, Callen E, Livak F, Nussenzweig MC, Sleckman BP, Nussenzweig A. 53BP1 facilitates long-range DNA end-joining during V(D)J recombination. Nature. 2008;456:529–533. doi: 10.1038/nature07476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bredemeyer AL, Huang CY, Walker LM, Bassing CH, Sleckman BP. Aberrant V(D)J recombination in ataxia telangiectasia mutated-deficient lymphocytes is dependent on nonhomologous DNA end joining. Journal of immunology. 2008;181:2620–2625. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.4.2620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang CY, Sharma GG, Walker LM, Bassing CH, Pandita TK, Sleckman BP. Defects in coding joint formation in vivo in developing ATM-deficient B and T lymphocytes. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2007;204:1371–1381. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lieber MR, Hesse JE, Lewis S, Bosma GC, Rosenberg N, Mizuuchi K, Bosma MJ, Gellert M. The defect in murine severe combined immune deficiency: joining of signal sequences but not coding segments in V(D)J recombination. Cell. 1988;55:7–16. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90004-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gao Y, Chaudhuri J, Zhu C, Davidson L, Weaver DT, Alt FW. A targeted DNA-PKcs-null mutation reveals DNA-PK-independent functions for KU in V(D)J recombination. Immunity. 1998;9:367–376. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80619-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Taccioli GE, Amatucci AG, Beamish HJ, Gell D, Xiang XH, Torres Arzayus MI, Priestley A, Jackson SP, Marshak Rothstein A, Jeggo PA, Herrera VL. Targeted disruption of the catalytic subunit of the DNA-PK gene in mice confers severe combined immunodeficiency and radiosensitivity. Immunity. 1998;9:355–366. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80618-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bogue MA, Jhappan C, Roth DB. Analysis of variable (diversity) joining recombination in DNAdependent protein kinase (DNA-PK)-deficient mice reveals DNA-PK-independent pathways for both signal and coding joint formation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1998;95:15559–15564. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wiler R, Leber R, Moore BB, VanDyk LF, Perryman LE, Meek K. Equine severe combined immunodeficiency: a defect in V(D)J recombination and DNA-dependent protein kinase activity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1995;92:11485–11489. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.25.11485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meek K, Kienker L, Dallas C, Wang W, Dark MJ, Venta PJ, Huie ML, Hirschhorn R, Bell T. SCID in Jack Russell terriers: a new animal model of DNA-PKcs deficiency. Journal of immunology. 2001;167:2142–2150. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.4.2142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kurimasa A, Ouyang H, Dong LJ, Wang S, Li X, Cordon-Cardo C, Chen DJ, Li GC. Catalytic subunit of DNA-dependent protein kinase: impact on lymphocyte development and tumorigenesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1999;96:1403–1408. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.4.1403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Woodbine L, Neal JA, Sasi NK, Shimada M, Deem K, Coleman H, Dobyns WB, Ogi T, Meek K, Davies EG, Jeggo PA. PRKDC mutations in a SCID patient with profound neurological abnormalities. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2013;123:2969–2980. doi: 10.1172/JCI67349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van der Burg M, Ijspeert H, Verkaik NS, Turul T, Wiegant WW, Morotomi-Yano K, Mari PO, Tezcan I, Chen DJ, Zdzienicka MZ, van Dongen JJ, van Gent DC. A DNA-PKcs mutation in a radiosensitive T-B- SCID patient inhibits Artemis activation and nonhomologous end-joining. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2009;119:91–98. doi: 10.1172/JCI37141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kulesza P, Lieber MR. DNA-PK is essential only for coding joint formation in V(D)J recombination. Nucleic acids research. 1998;26:3944–3948. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.17.3944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peng Y, Woods RG, Beamish H, Ye R, Lees-Miller SP, Lavin MF, Bedford JS. Deficiency in the catalytic subunit of DNA-dependent protein kinase causes down-regulation of ATM. Cancer research. 2005;65:1670–1677. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shrivastav M, Miller CA, De Haro LP, Durant ST, Chen BP, Chen DJ, Nickoloff JA. DNA-PKcs and ATM co-regulate DNA double-strand break repair. DNA repair. 2009;8:920–929. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2009.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gapud EJ, Dorsett Y, Yin B, Callen E, Bredemeyer A, Mahowald GK, Omi KQ, Walker LM, Bednarski JJ, McKinnon PJ, Bassing CH, Nussenzweig A, Sleckman BP. Ataxia telangiectasia mutated (Atm) and DNA-PKcs kinases have overlapping activities during chromosomal signal joint formation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:2022–2027. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1013295108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zha S, Jiang W, Fujiwara Y, Patel H, Goff PH, Brush JW, Dubois RL, Alt FW. Ataxia telangiectasia-mutated protein and DNA-dependent protein kinase have complementary V(D)J recombination functions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:2028–2033. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019293108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Neal JA, Dang V, Douglas P, Wold MS, Lees-Miller SP, Meek K. Inhibition of homologous recombination by DNA-dependent protein kinase requires kinase activity, is titratable, and is modulated by autophosphorylation. Molecular and cellular biology. 2011;31:1719–1733. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01298-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fukumura R, Araki R, Fujimori A, Tsutsumi Y, Kurimasa A, Li GC, Chen DJ, Tatsumi K, Abe M. Signal joint formation is also impaired in DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit knockout cells. Journal of immunology. 2000;165:3883–3889. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.7.3883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hesse JE, Lieber MR, Mizuuchi K, Gellert M. V(D)J recombination: a functional definition of the joining signals. Genes & development. 1989;3:1053–1061. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.7.1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cui X, Meek K. Linking double-stranded DNA breaks to the recombination activating gene complex directs repair to the nonhomologous end-joining pathway. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:17046–17051. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610928104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Corneo B, Wendland RL, Deriano L, Cui X, Klein IA, Wong SY, Arnal S, Holub AJ, Weller GR, Pancake BA, Shah S, Brandt VL, Meek K, Roth DB. Rag mutations reveal robust alternative end joining. Nature. 2007;449:483–486. doi: 10.1038/nature06168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bakkenist CJ, Kastan MB. DNA damage activates ATM through intermolecular autophosphorylation and dimer dissociation. Nature. 2003;421:499–506. doi: 10.1038/nature01368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meek K, Lees-Miller SP, Modesti M. N-terminal constraint activates the catalytic subunit of the DNA-dependent protein kinase in the absence of DNA or Ku. Nucleic acids research. 2012;40:2964–2973. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mali P, Yang L, Esvelt KM, Aach J, Guell M, DiCarlo JE, Norville JE, Church GM. RNA-guided human genome engineering via Cas9. Science. 2013;339:823–826. doi: 10.1126/science.1232033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Finnie NJ, Gottlieb TM, Blunt T, Jeggo PA, Jackson SP. DNA-dependent protein kinase activity is absent in xrs-6 cells: implications for site-specific recombination and DNA double-strand break repair. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1995;92:320–324. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.1.320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Errami A, He DM, Friedl AA, Overkamp WJ, Morolli B, Hendrickson EA, Eckardt-Schupp F, Oshimura M, Lohman PH, Jackson SP, Zdzienicka MZ. XR-C1, a new CHO cell mutant which is defective in DNA-PKcs, is impaired in both V(D)J coding and signal joint formation. Nucleic acids research. 1998;26:3146–3153. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.13.3146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gapud EJ, Sleckman BP. Unique and redundant functions of ATM and DNA-PKcs during V(D)J recombination. Cell cycle. 2011;10:1928–1935. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.12.16011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Blunt T, Finnie NJ, Taccioli GE, Smith GC, Demengeot J, Gottlieb TM, Mizuta R, Varghese AJ, Alt FW, Jeggo PA, Jackson SP. Defective DNA-dependent protein kinase activity is linked to V(D)J recombination and DNA repair defects associated with the murine scid mutation. Cell. 1995;80:813–823. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90360-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Priestley A, Beamish HJ, Gell D, Amatucci AG, Muhlmann-Diaz MC, Singleton BK, Smith GC, Blunt T, Schalkwyk LC, Bedford JS, Jackson SP, Jeggo PA, Taccioli GE. Molecular and biochemical characterisation of DNA-dependent protein kinase-defective rodent mutant irs-20. Nucleic acids research. 1998;26:1965–1973. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.8.1965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kurimasa A, Kumano S, Boubnov NV, Story MD, Tung CS, Peterson SR, Chen DJ. Requirement for the kinase activity of human DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit in DNA strand break rejoining. Molecular and cellular biology. 1999;19:3877–3884. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.5.3877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shin EK, Rijkers T, Pastink A, Meek K. Analyses of TCRB rearrangements substantiate a profound deficit in recombination signal sequence joining in SCID foals: implications for the role of DNA-dependent protein kinase in V(D)J recombination. Journal of immunology. 2000;164:1416–1424. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.3.1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kienker LJ, Shin EK, Meek K. Both V(D)J recombination and radioresistance require DNA-PK kinase activity, though minimal levels suffice for V(D)J recombination. Nucleic acids research. 2000;28:2752–2761. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.14.2752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ding Q, Reddy YV, Wang W, Woods T, Douglas P, Ramsden DA, Lees-Miller SP, Meek K. Autophosphorylation of the catalytic subunit of the DNA-dependent protein kinase is required for efficient end processing during DNA double-strand break repair. Molecular and cellular biology. 2003;23:5836–5848. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.16.5836-5848.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Neal JA, Sugiman-Marangos S, VanderVere-Carozza P, Wagner M, Turchi J, Lees-Miller SP, Junop MS, Meek K. Unraveling the complexities of DNA-dependent protein kinase autophosphorylation. Molecular and cellular biology. 2014;34:2162–2175. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01554-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ruis BL, Fattah KR, Hendrickson EA. The catalytic subunit of DNA-dependent protein kinase regulates proliferation, telomere length, and genomic stability in human somatic cells. Molecular and cellular biology. 2008;28:6182–6195. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00355-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bosma GC, Custer RP, Bosma MJ. A severe combined immunodeficiency mutation in the mouse. Nature. 1983;301:527–530. doi: 10.1038/301527a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mathieu AL, Verronese E, Rice GI, Fouyssac F, Bertrand Y, Picard C, Chansel M, Walter JE, Notarangelo LD, Butte MJ, Nadeau KC, Csomos K, Chen DJ, Chen K, Delgado A, Rigal C, Bardin C, Schuetz C, Moshous D, Reumaux H, Plenat F, Phan A, Zabot MT, Balme B, Viel S, Bienvenu J, Cochat P, van der Burg M, Caux C, Kemp EH, Rouvet I, Malcus C, Meritet JF, Lim A, Crow YJ, Fabien N, Menetrier-Caux C, De Villartay JP, Walzer T, Belot A. PRKDC mutations associated with immunodeficiency, granuloma, and autoimmune regulator-dependent autoimmunity. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2015;135:1578–1588. e1575. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.01.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shin EK, Perryman LE, Meek K. A kinase-negative mutation of DNA-PK(CS) in equine SCID results in defective coding and signal joint formation. Journal of immunology. 1997;158:3565–3569. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ding Q, Bramble L, Yuzbasiyan-Gurkan V, Bell T, Meek K. DNA-PKcs mutations in dogs and horses: allele frequency and association with neoplasia. Gene. 2002;283:263–269. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(01)00880-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Verfuurden B, Wempe F, Reinink P, van Kooten PJ, Martens E, Gerritsen R, Vos JH, Rutten VP, Leegwater PA. Severe combined immunodeficiency in Frisian Water Dogs caused by a RAG1 mutation. Genes and immunity. 2011;12:310–313. doi: 10.1038/gene.2011.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Waide EH, Dekkers JC, Ross JW, Rowland RR, Wyatt CR, Ewen CL, Evans AB, Thekkoot DM, Boddicker NJ, Serao NV, Ellinwood NM, Tuggle CK. Not All SCID Pigs Are Created Equally: Two Independent Mutations in the Artemis Gene Cause SCID in Pigs. Journal of immunology. 2015;195:3171–3179. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1501132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pastwa E, Lubner EM, Mezhevaya K, Neumann RD, Winters TA. DNA uptake and repair enzyme access to transfected DNA is under reported by gene expression. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2003;306:421–429. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)00972-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Piechaczek C, Fetzer C, Baiker A, Bode J, Lipps HJ. A vector based on the SV40 origin of replication and chromosomal S/MARs replicates episomally in CHO cells. Nucleic acids research. 1999;27:426–428. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.2.426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kumar V, Alt FW, Oksenych V. Functional overlaps between XLF and the ATM-dependent DNA double strand break response. DNA repair. 2014;16:11–22. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2014.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yin B, Lee BS, Yang-Iott KS, Sleckman BP, Bassing CH. Redundant and nonredundant functions of ATM and H2AX in alphabeta T-lineage lymphocytes. Journal of immunology. 2012;189:1372–1379. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zha S, Guo C, Boboila C, Oksenych V, Cheng HL, Zhang Y, Wesemann DR, Yuen G, Patel H, Goff PH, Dubois RL, Alt FW. ATM damage response and XLF repair factor are functionally redundant in joining DNA breaks. Nature. 2011;469:250–254. doi: 10.1038/nature09604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zha S, Sekiguchi J, Brush JW, Bassing CH, Alt FW. Complementary functions of ATM and H2AX in development and suppression of genomic instability. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105:9302–9306. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803520105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Andres SN, Vergnes A, Ristic D, Wyman C, Modesti M, Junop M. A human XRCC4-XLF complex bridges DNA. Nucleic acids research. 2012;40:1868–1878. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Roy S, Andres SN, Vergnes A, Neal JA, Xu Y, Yu Y, Lees-Miller SP, Junop M, Modesti M, Meek K. XRCC4's interaction with XLF is required for coding (but not signal) end joining. Nucleic acids research. 2012;40:1684–1694. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wu Q, Ochi T, Matak-Vinkovic D, Robinson CV, Chirgadze DY, Blundell TL. Non-homologous end-joining partners in a helical dance: structural studies of XLF-XRCC4 interactions. Biochemical Society transactions. 2011;39:1387–1392. doi: 10.1042/BST0391387. suppl 1382 p following 1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hammel M, Yu Y, Fang S, Lees-Miller SP, Tainer JA. XLF regulates filament architecture of the XRCC4.ligase IV complex. Structure. 2010;18:1431–1442. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2010.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Coussens MA, Wendland RL, Deriano L, Lindsay CR, Arnal SM, Roth DB. RAG2's acidic hinge restricts repair-pathway choice and promotes genomic stability. Cell reports. 2013;4:870–878. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.07.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chaumeil J, Micsinai M, Ntziachristos P, Roth DB, Aifantis I, Kluger Y, Deriano L, Skok JA. The RAG2 C-terminus and ATM protect genome integrity by controlling antigen receptor gene cleavage. Nature communications. 2013;4:2231. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bredemeyer AL, Sharma GG, Huang CY, Helmink BA, Walker LM, Khor KC, Nuskey B, Sullivan KE, Pandita TK, Bassing CH, Sleckman BP. ATM stabilizes DNA double-strand-break complexes during V(D)J recombination. Nature. 2006;442:466–470. doi: 10.1038/nature04866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Callen E, Jankovic M, Difilippantonio S, Daniel JA, Chen HT, Celeste A, Pellegrini M, McBride K, Wangsa D, Bredemeyer AL, Sleckman BP, Ried T, Nussenzweig M, Nussenzweig A. ATM prevents the persistence and propagation of chromosome breaks in lymphocytes. Cell. 2007;130:63–75. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hewitt SL, Yin B, Ji Y, Chaumeil J, Marszalek K, Tenthorey J, Salvagiotto G, Steinel N, Ramsey LB, Ghysdael J, Farrar MA, Sleckman BP, Schatz DG, Busslinger M, Bassing CH, Skok JA. RAG-1 and ATM coordinate monoallelic recombination and nuclear positioning of immunoglobulin loci. Nature immunology. 2009;10:655–664. doi: 10.1038/ni.1735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zha S, Bassing CH, Sanda T, Brush JW, Patel H, Goff PH, Murphy MM, Tepsuporn S, Gatti RA, Look AT, Alt FW. ATM- deficient thymic lymphoma is associated with aberrant tcrd rearrangement and gene amplification. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2010;207:1369–1380. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yin B, Savic V, Juntilla MM, Bredemeyer AL, Yang-Iott KS, Helmink BA, Koretzky GA, Sleckman BP, Bassing CH. Histone H2AX stabilizes broken DNA strands to suppress chromosome breaks and translocations during V(D)J recombination. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2009;206:2625–2639. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mahowald GK, Baron JM, Mahowald MA, Kulkarni S, Bredemeyer AL, Bassing CH, Sleckman BP. Aberrantly resolved RAG-mediated DNA breaks in Atm-deficient lymphocytes target chromosomal breakpoints in cis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106:18339–18344. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902545106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Savic V, Yin B, Maas NL, Bredemeyer AL, Carpenter AC, Helmink BA, Yang-Iott KS, Sleckman BP, Bassing CH. Formation of dynamic gamma-H2AX domains along broken DNA strands is distinctly regulated by ATM and MDC1 and dependent upon H2AX densities in chromatin. Molecular cell. 2009;34:298–310. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Steinel NC, Fisher MR, Yang-Iott KS, Bassing CH. The ataxia telangiectasia mutated and cyclin D3 proteins cooperate to help enforce TCRbeta and IgH allelic exclusion. Journal of immunology. 2014;193:2881–2890. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1302201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Steinel NC, Lee BS, Tubbs AT, Bednarski JJ, Schulte E, Yang-Iott KS, Schatz DG, Sleckman BP, Bassing CH. The ataxia telangiectasia mutated kinase controls Igkappa allelic exclusion by inhibiting secondary Vkappa-to-Jkappa rearrangements. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2013;210:233–239. doi: 10.1084/jem.20121605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kim MS, Lapkouski M, Yang W, Gellert M. Crystal structure of the V(D)J recombinase RAG1-RAG2. Nature. 2015;518:507–511. doi: 10.1038/nature14174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ru H, Chambers MG, Fu TM, Tong AB, Liao M, Wu H. Molecular Mechanism of V(D)J Recombination from Synaptic RAG1-RAG2 Complex Structures. Cell. 2015;163:1138–1152. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.10.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Jones JM, Gellert M. Intermediates in V(D)J recombination: a stable RAG1/2 complex sequesters cleaved RSS ends. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98:12926–12931. doi: 10.1073/pnas.221471198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Agrawal A, Schatz DG. RAG1 and RAG2 form a stable postcleavage synaptic complex with DNA containing signal ends in V(D)J recombination. Cell. 1997;89:43–53. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80181-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Franco S, Gostissa M, Zha S, Lombard DB, Murphy MM, Zarrin AA, Yan C, Tepsuporn S, Morales JC, Adams MM, Lou Z, Bassing CH, Manis JP, Chen J, Carpenter PB, Alt FW. H2AX prevents DNA breaks from progressing to chromosome breaks and translocations. Molecular cell. 2006;21:201–214. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Goodarzi AA, Yu Y, Riballo E, Douglas P, Walker SA, Ye R, Harer C, Marchetti C, Morrice N, Jeggo PA, Lees-Miller SP. DNA-PK autophosphorylation facilitates Artemis endonuclease activity. The EMBO journal. 2006;25:3880–3889. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Zhu C, Roth DB. Characterization of coding ends in thymocytes of scid mice: implications for the mechanism of V(D)J recombination. Immunity. 1995;2:101–112. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90082-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.