Abstract

The differentiation of effector CD8+ T cells is a dynamically regulated process that varies during different infections and is influenced by the inflammatory milieu of the host. Here, we define three signals regulating CD8+ T cell responses during tuberculosis by focusing on cytokines known to affect disease outcome: IL-12, type I IFN, and IL-27. Using mixed bone marrow chimeras, we compared wild type and cytokine receptor knockout CD8+ T cells within the same mouse following aerosol infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Four weeks post-infection, IL-12, type 1 IFN, and IL-27 were all required for efficient CD8+ T cell expansion in the lungs. We next determined if these cytokines directly promote CD8+ T cell priming or are required only for expansion in the lungs. Utilizing retrogenic CD8+ T cells specific for the Mtb antigen TB10.4 (EsxH), we observed that IL-12 is the dominant cytokine driving both CD8+ T cell priming in the lymph node and expansion in the lungs; however, type I IFN and IL-27 have non-redundant roles supporting pulmonary CD8+ T cell expansion. Thus, IL-12 is a major signal promoting priming in the lymph node, but a multitude of inflammatory signals converge in the lung to promote continued expansion. Furthermore, these cytokines regulate the differentiation and function of CD8+ T cells during tuberculosis. These data demonstrate distinct and overlapping roles for each of the cytokines examined and underscore the complexity of CD8+ T cell regulation during tuberculosis.

Introduction

Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) infection elicits IL-12, type I IFN, and IL-27, all of which have profound effects on disease outcome and host resistance. IL-12 is required for host resistance in mice and humans, and has an essential role in promoting CD4+ T cell responses (1, 2). In contrast, IL-27 acts as an immunoregulatory cytokine and can dampen CD4+ T cell responses. During tuberculosis, IL-27 limits the control of bacterial growth but is necessary to prevent immunopathology during chronic disease (3, 4). Type I IFN has a variety of effects during infection, and its overproduction is detrimental to host resistance (5). The increased resistance of IFNAR−/− mice to Mtb infection underscores this fact (6–9). A similar association exists in humans, where type I IFN signaling is linked to active disease (10).

In other infections, all three of these cytokines are key regulators of CD8+ T cells and can act as essential signals promoting CD8+ T cell expansion and effector function. In particular, IL-12 and type I IFN can provide a necessary signal for priming naïve CD8+ T cells. This signal works in conjunction with T cell receptor (TCR) stimulation (signal 1) and costimulation (signal 2), and these “signal 3” cytokines influence CD8+ T cell expansion, differentiation, effector functions, and memory formation (11, 12). In the absence of signal 3 cytokines, primed CD8+ T cells can proliferate but fail to develop effector functions and become tolerant to antigen (Ag) stimulation (13). The relative importance of IL-12 or type 1 IFN varies between different infections and is dictated by the inflammatory response elicited by the pathogen (14, 15). Currently, the signal 3 requirements for CD8+ T cell responses during tuberculosis are uncharacterized. IL-27 can also affect CD8+ T cell function in ways similar to IL-12 and type I IFN, though it has never been formally examined as a signal 3 cytokine. In certain vaccination strategies, CD8+ T cells require IL-27 for both primary expansion and recall responses (16). During vesicular stomatitis virus infection, IL-27 influences differentiation by promoting the accumulation of terminally differentiated short-lived effector cells (SLECs) (17). IL-27 is also associated with promoting CD8+ T cell function, and is required for IFN-γ expression during both Toxoplasma gondii and influenza virus infection (18).

Although Mtb infection elicits CD8+ T cell responses with similar kinetics and magnitude as CD4+ T cell responses, protection mediated by CD8+ T cells has been more difficult to demonstrate in vivo and in vitro (19, 20). Here, we consider whether inflammatory signals augment or potentially inhibit CD8+ T cell function, and begin by addressing the roles of IL-12, type I IFN, and IL-27. These cytokines were selected because of their impact on disease outcome and because previous studies have focused on their effects on CD4+ T cells. Given that IL-12, type 1 IFN, and IL-27 have distinct effects on CD8+ T cells in other infections, it is imperative to understand their role in CD8+ T cell responses during tuberculosis. Specifically, we are interested in defining the signal 3 cytokine requirements for CD8+ T cells responding to infection with Mtb.

Using 1:1 mixed bone marrow chimeras (MBMCs), we demonstrate that IL-12 is essential to promote CD8+ T cell expansion and the acquisition of effector functions. Type I IFN and IL-27 also augment the expansion of effector cells in this system. These findings support a model in which each cytokine influences CD8+ T cell expansion in a non-redundant way. In additional experiments with bone marrow (BM) chimeras, we interrogate the cytolytic ability of CD8+ T cells incapable of responding to IL-12, type 1 IFN, or IL-27 in vivo. Overall specific killing is reduced in the absence of IL-12; however, CD8+ T cells remain highly cytolytic without IL-12 signaling. This surprising finding indicates that cytolysis is a robust effector function during tuberculosis and is likely promoted and executed through redundant mechanisms (21).

Using the adoptive transfer of retrogenic Ag-specific CD8+ T cells, we directly examine priming following low-dose aerosol infection. These studies reveal that IL-12 is necessary to prime CD8+ T cells in the lymph node (LN) and to continue their expansion in the lungs. For this reason, IL-12 is the dominant signal 3 cytokine during tuberculosis. In total, IL-12 promotes CD8+ T cell priming, expansion, SLEC differentiation, and IFN-γ production, while type I IFN and IL-27 support expansion in the lungs. To date, this is the most comprehensive study of CD8+ T cell regulation during tuberculosis. We believe such understanding has implications for rational vaccine design and the development of immunotherapies.

Materials and Methods

Ethics Statement

The animal studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the Dana Farber Cancer Institute or the University of Massachusetts Medical School (Animal Welfare Assurance no. A3023-01 [DFCI] or A3306-01 [UMMS]), using the recommendations from the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health and the Office of Laboratory Animal Welfare.

Mice

C57BL/6 (WT), CD45.1 (B6.SJL-PtprcaPepcb/BoyJ), CD90.1 (B6.PL-Thy1a/CyJ), TCRα−/− (B6.129S2-Tcratm1Mom/J), CD8α−/− (B6.129S2-Cd8atm1Mak/J), IL-12 receptor beta 2 deficient (IL-12R−/−: B6.129S1-Il12rb2tm1Jm/J), and IL-27 receptor alpha deficient (IL-27R−/−: B6N.129P2-Il27ratm1Mak/J) mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). Interferon-α/β receptor deficient mice (IFNAR−/−) were obtained from Dr. Raymond M. Welsh and were previously described (10, 22, 23). Mice were 8 to 10 weeks old at the start of all experiments. Mice infected with M. tuberculosis were housed in a biosafety level 3 facility under specific pathogen-free conditions at DFCI or at UMMS.

Generation of mouse bone marrow chimeras

1:1 mixed bone barrow chimeras (MBMCs) were made by lethally irradiating CD90.1+ recipients (2 doses of 600 rads separated by three hours). BM was flushed from the femurs, tibia, and humeri of donor mice and RBC lysed. BM cells were then enumerated and groups were combined in a 1:1 ratio. Each recipient mouse received a total of 107 BM cells (5×106 of WT and 5×106 of KO) via lateral tail vein injection and was kept on antibiotic-treated water for 5 weeks following irradiation. Mice were checked for reconstitution by retro-orbital bleeding to assess the ratio of donor cells in the peripheral blood by flow cytometry. MBMCs were infected with Mtb 8-10 weeks after transfer of the bone marrow cells. For 4:1 chimeras, TCRα−/− mice were given a lower dose of radiation (2 doses of 500 rads separated by three hours). The ratio of donor cells in these chimeras was 80% CD8α−/− and 20% of the indicate WT or KO BM.

Generation of retrogenic mice

Detailed information on the generation of TB104-11-specfic retrogenic T cells was previously published (24). TCR retroviral constructs were generated as 2A-linked single open reading frames using PCR and cloned into a murine stem cell virus-based retroviral vector with a GFP marker as previously described (25). Retroviral-mediated stem cell gene transfer was performed as previously described (25). For all experiments shown, the TB104-11-specfic TCR used corresponds to TCR3 (Rg3) as described by Nunes-Alves et al. (24).

Experimental infection and bacterial quantification

Infection with M. tuberculosis (Mtb – Erdman strain) was performed via the aerosol route, and mice received a day 1 inoculum of 50–200 CFU. A bacterial aliquot was thawed, sonicated twice for 10 seconds in a cup horn sonicator, and then diluted in 0.9% NaCl–0.02% Tween 80. A 15 ml suspension of Mtb was loaded into a nebulizer (MiniHEART nebulizer; Vortran Medical Technologies) and mice were infected using a nose-only exposure unit (Intox Products). Alternatively, the bacterial aliquot was diluted in a final volume of 5ml, and mice were infected using a Glas-Col aerosol-generation device. To determine CFU, mice were euthanized by carbon dioxide inhalation, organs were aseptically removed, individually homogenized, and viable bacteria were enumerated by plating 10-fold serial dilutions of organ homogenates onto 7H11 agar plates. Plates were incubated at 37°C and M. tuberculosis colonies were counted after 21 days. We observed no differences in day 1 CFU between the nose-only exposure unit and the Glas-Col aerosol-generation device. For all of the priming experiments using transferred retrogenic T cells, infections were performed exclusively with the Glas-Col aerosol-generation device.

Flow cytometry analysis

Cell suspensions from lung, spleen and lymph nodes were prepared by gentle disruption of the organs through a 70μm nylon strainer (Fisher) or using the GentleMacs Dissociator (Miltenyi Biotec, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. For lung preparations, tissue was digested for 30–60 min at 37°C in cRPMI with 300U/ml collagenase (Sigma) prior to straining. Erythrocytes were lysed using a hemolytic solution (155 mM NH4Cl, 10 mM KHCO3, 0.1 mM sodium EDTA pH 7.2) and, after washing, cells were resuspended in supplemented RPMI (cRPMI - 10% heat inactivated FCS, 10 mM HEPES, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 2 mM L-glutamine, 50 mg/ml streptomycin and 50 U/ml penicillin, all from Invitrogen) or MACS buffer (Miltenyi Biotec, Germany). Cells were enumerated in 4% trypan blue on a hemocytometer or using a MACSQuant flow cytometer (Miltenyi Biotec, Germany). Surface staining was performed with antibodies specific for mouse CD3 (clone 17A2), CD3ε (clone 145-2C11), CD4 (clone GK1.5), CD8 (clone 53-6.7), CD19 (clone 6D5), CD44 (clone IM7), CD62L (clone MEL-14), CD45.1 (clone A20), CD45.2 (clone 104), CD90.1 (clone OX-7), CD90.2 (clone 53-2.1), CD127 (clone A7R34), KLRG1 (clone 2F1/KLRG1) and Va2 (clone B20.1), (from Biolegend, CA, USA, or from BD Pharmingen, CA, USA). The tetramers of TB10.44–11-loaded H-2 Kb were obtained from the National Institutes of Health Tetramer Core Facility (Emory University Vaccine Center, Atlanta, GA, USA). All staining was performed for 20 min at 4°C and, unless otherwise stated. Cells were fixed before acquisition with 1% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 60 minutes. Cell analysis was performed on a FACS Canto (Becton Dickinson, NJ, USA) or on a MACSQuant flow cytometer (Miltenyi Biotec, Germany). Data were analyzed using FlowJo Software (Tree Star, OR, USA). For all of the FACS analysis, single-lymphocyte events were gated by forward scatter versus height and side scatter for size and granularity.

Intracellular cytokine staining

5×105-1×106 cells were plated in each well of a round bottom 96-well plate and incubated in the presence of TB10.44-11 peptide (10 μM; New England Peptide). Cells incubated in the presence of αCD3/αCD28 (1 μg/mL; BioLegend) or in the absence of stimuli were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. Cells were incubated for 1 hour at 37° C, at which point GolgiPlug solution (BD Pharmingen, CA, USA) was added to each well for the remaining 4 hours. Cells were collected after the 5 hours stimulation and then surface stained with the antibodies described above, followed by intracellular staining for IFN-γ (clone XMG1.2), TNF (clone MPX6-T22), or granzyme B (clone gb11) using the BD Permwash Kit (BD Pharmingen, CA, USA) as per manufacturer's instructions.

In vivo cytotoxicity assay

In vivo cytotoxicity was determined using peptide-coated splenocytes differentially labeled with the fluorescent dyes CFSE and efluor 450 (eBiosciences) as previously described (21). All target cells were obtained from the spleens of uninfected mice. Target cells were labeled in PBS for either 20 minutes (efluor 450) or 10 minutes (CFSE) at room temperature, followed by extensive washing. Target cell populations were pulsed with 100 nM of the TB10.44-11 peptide at 37°C for 1 hour in complete medium or left unpulsed. Labeled populations were mixed at an equal cell ratio and injected IV into age-matched uninfected and infected recipient mice (2.5×106 of each labeled population per mouse). After 20 hours, recipient spleens and lungs were harvested and single-cell suspensions were made as described. Ratios of recovered CFSE- and efluor 450-labeled target lymphocyte populations were determined by flow cytometry. Percent specific killing was determined by the following formula: percent specific killing = 100 − (100 - (ratio in infected mice)/(ratio in uninfected mice)), where ratio = percent peptide-pulsed target cells/percent unpulsed target cells.

Adoptive T cell transfer

Single cell suspensions of pools of spleens and lymph nodes from naïve retrogenic mice (6 to 12 weeks post reconstitution) were prepared. CD8+ T cells were purified from each suspension using the CD8+ T cell isolation kit and magnetic separation (STEMCELL Technologies Inc, Canada). After purification, cells were counted and transferred via the tail vein into congenically marked recipients (CD45.1 or CD90.1), which had been infected 7 days earlier with virulent Mtb (Erdman) via the aerosol route. For all experiments, 3×104 -5×104 cells of each group were transferred into each recipient. WT retrogenic CD8+ T cells survived in infected mice and were detectable in the lymph nodes, lungs, and spleens for at least 4 weeks after transfer.

Measurement of cell proliferation

For analysis of cell proliferation of retrogenic cells after adoptive transfer, bead-purified naïve Rg cells (see above) were labeled with 5 μM of cell proliferation dye efluor 450 (eBiosciences) in PBS for 20 min at room temperature, followed by extensive washing.

Cell isolation and microarray analysis

Female C57BL/6 mice were infected with Mtb Erdman as described above. At the indicated time points, mice were euthanized by cervical dislocation and lungs were harvested after perfusion with collagenase containing media. Lungs were allowed to digest in collagenase-containing media for 15 minutes before being homogenized into single cell suspensions. At this point, the lungs from 3 individual mice were combined into a single sample. T cells were then purified by negative magnetic bead selection (Miltenyi Biotec, Germany). Purified cells were stained to distinguish CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (CD19, CD3, CD4, CD8). For cell sorting, stained cells were suspended in MACS buffer (Miltenyi Biotec, Germany) and deposited in collection tubes using a BD Canto flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, NJ, USA). 50,000 CD19−CD3+CD8+ cells were sorted directly into TRIzol Reagent (Life Technologies, California) and immediately frozen. RNA extraction, microarray hybridization (Affymetrix Mouse Gene 1.0ST array) and data processing were done at the ImmGen Project processing center. Details of the data analysis and quality control can be found at (www.immgen.org).

Statistical analysis

All data are represented as mean with SEM. Comparisons of two groups within 1:1 mixed bone marrow chimeras were done with a paired student's t-test. All other comparisons were done with an unpaired student's t-test and are indicated in the figure legends. Comparisons of more than two groups were done using Holm-Šídák multiple comparisons testing following two-way ANOVA. Significance was represented by the following symbols: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001, ‡P < 0.0001, and N.S. = not significant.

Results

CD8+ T cells express the IL-12, type I IFN, and IL-27 receptors throughout Mtb infection

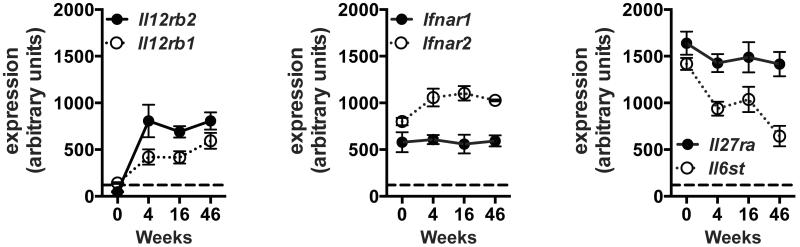

IL-12, IFNβ, and IL-27 are all expressed in the lungs of Mtb-infected mice, as previously reported by multiple groups (2, 3, 26, 27). To determine the extent to which the receptors for IL-12, type I IFN, and IL-27 are expressed by CD8+ T cells during Mtb infection, we performed gene expression profiling on highly purified CD8+ T cells from the lungs of uninfected or Mtb infected mice. Briefly, CD8+ T cells were enriched from the lungs of uninfected or infected mice using immunomagnetic beads and then flow sorted to >99% pure CD3+CD8+ cells. Microarray gene expression profiling was performed and expression values were normalized across all the samples and time points in the experiment. Here, we focus on the relative expression of the subunits for the IL-12 receptor (IL-12R; Il12rb1 and Il12rb2), the interferon-α/β receptor (IFNAR; Ifnar1 and Ifnar2), and the IL-27 receptor (IL-27R; Il27ra and Il6st) (Fig. 1). IL12rb1 transcripts were marginally detectable in CD8+ T cells from the lungs of uninfected mice (time 0) and IL12rb2 was undetectable (Fig. 1). Following infection, transcription of both IL-12 receptor subunits increased and remained detectable throughout the infection (Fig. 1). CD8+ T cells from both uninfected and infected mice constitutively expressed the IFNAR and IL-27R subunits, which persisted at relatively high levels during the course of infection (Fig. 1). Together, these findings suggest that CD8+ T cells are capable of responding to all three cytokines throughout infection.

Figure 1. CD8+ T cells express IL-12, type 1 IFN, and IL-27 receptors throughout Mtb infection.

Expression of the indicated cytokine receptor subunits by sorted CD8+ T cells purified from the lungs of uninfected mice (time 0) and infected mice at the indicated time points. Each point represents the mean ± SEM, of replicates from 3–4 independent infections, each with three pooled mice. Values above 120 (indicated by the dotted line) have a 95% or greater probability of true expression. The receptor subunits shown are: IL-12 receptor (IL-12R; Il12rb1 and Il12rb2), the interferon-α/β receptor (IFNAR; Ifnar1 and Ifnar2), and the IL-27 receptor (IL-27R; Il27ra and Il6st). Receptor subunits displayed in black correspond to the cytokine receptor knockout (KO) mice used in all subsequent figures.

IL-12, type I IFN, and IL-27 augment the magnitude of CD8+ T cell responses during tuberculosis

The inflammatory response and degree of susceptibility to Mtb varies substantially between the IL-12 p40, IFNAR, and IL-27R knockout (KO) mice, which confounds the elucidation of how these cytokine receptors regulate T cell function in an intact host (1–4, 6–9). To avoid this pitfall as we determined the effects of IL-12, type I IFN, and IL-27 on CD8+ T cell responses during tuberculosis, we used 1:1 mixed bone marrow chimeras (MBMCs) in an aerosol infection model, which allows for the direct comparison of wild-type (WT) and cytokine receptor KO CD8+ T cells within the same host mouse. This experimental system has the key advantage of exposing both WT and KO CD8+ T cells to the same inflammatory environment and bacterial burden throughout the infection.

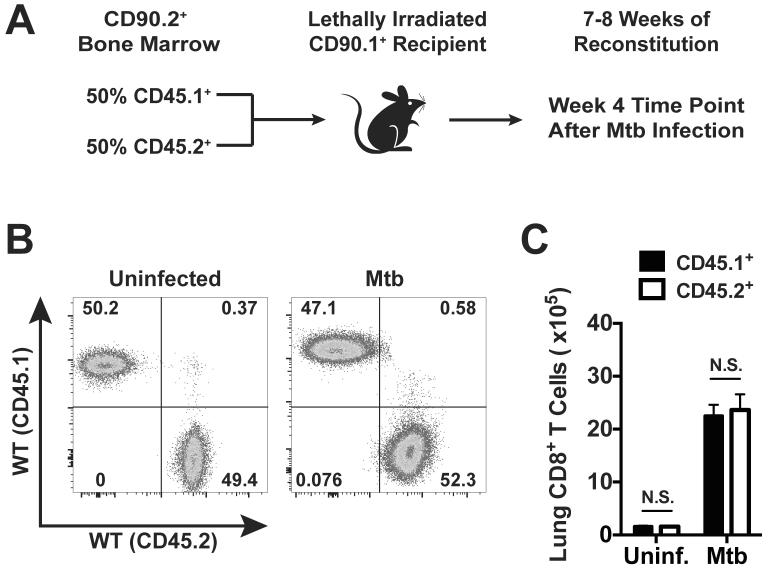

To generate chimeric mice, congenically marked (CD90.1+) recipients were lethally irradiated and reconstituted with equal ratios of WT (CD45.1+) BM and BM from one of the receptor knockout strains (CD45.2+) (Fig. 2a). In control experiments, we generated MBMCs with a mixture of WT CD45.1+ and WT CD45.2+ BM. After reconstitution, these control mice maintained equal ratios and numbers of CD45.1+ and CD45.2+ CD8+ T cells in the lungs before and four weeks after Mtb infection (Fig. 2b and 2c), which confirms that both groups of donor-derived cells have the potential to respond similarly to Mtb infection in this model. Our experimental conditions used donor mice lacking one of following cytokine receptors: IL-12 receptor beta 2 (IL-12R−/−), interferon-α/β receptor 1 (IFNAR−/−), or IL-27 receptor alpha (IL-27R−/−). Following reconstitution, the resulting chimeras had equivalent ratios of WT and KO CD8+ T cells in the peripheral blood and lungs (Fig. 3a and 3d). This indicates that the absence of the individual cytokine receptors did not significantly alter T cell development and homeostasis in uninfected mice. Once baseline reconstitution was assessed, the chimeras were infected via the aerosol route and examined four weeks later, which is the peak of the T cell response to Mtb (28).

Figure 2. Donor bone marrow-derived CD8+ T cells contribute to immunity following Mtb infection of mixed bone marrow chimeras.

(a) Strategy used to generate MBMCs. A 1:1 ratio of WT CD45.1+ and WT CD45.2+ BM was infused into lethally irradiated CD90.1 (a.k.a. Thy1.1) mice. (b) Representative flow cytometry plots of CD3+ CD8+ T cells from the lungs of an uninfected MBMC and another MBMC four weeks after aerosol Mtb infection. (c) Total number of WT (CD45.1+) or WT (CD45.2+) CD8+ T cells in the lungs of MBMCs before or 4 weeks after Mtb infection. Each bar represents the mean ± SEM (n = 4-5 mice per experiment). N.S. indicates “not significant” (paired Student's t-test). Data are representative of two independent experiments.

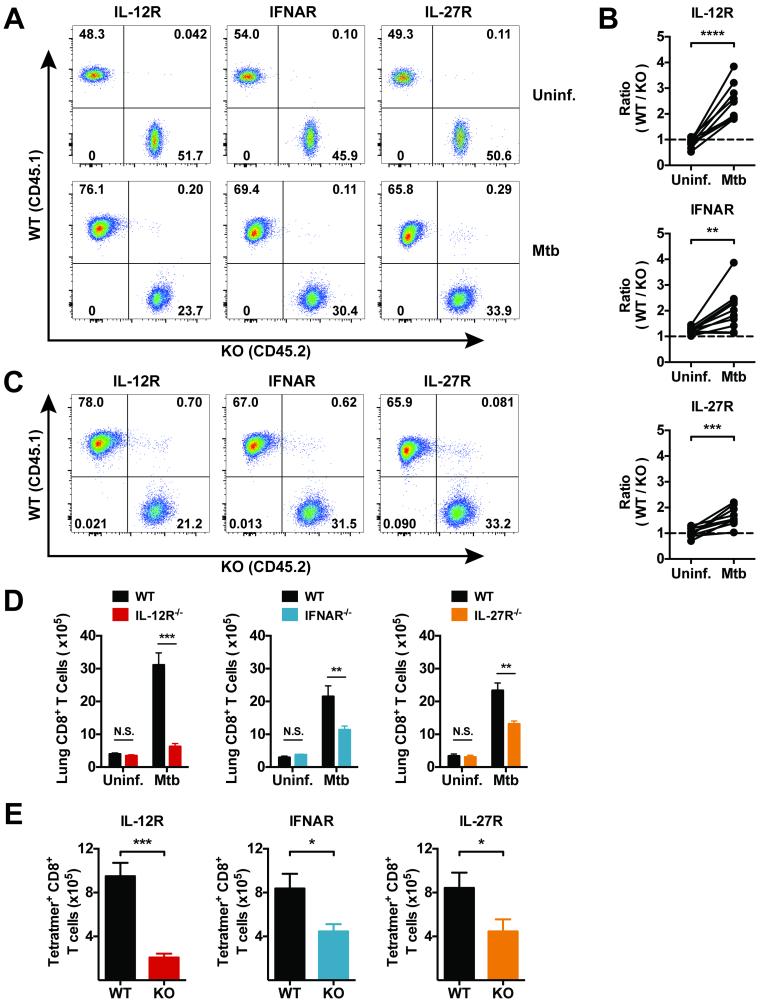

Figure 3. IL-12, type 1 IFN, and IL-27 promote CD8+ T cell expansion following Mtb infection.

(a) Representative flow cytometry plots of CD3+ CD8+ T cells from the blood of the same MBMC before and four weeks after infection with Mtb. (b) The ratio of WT to KO CD3+ CD8+ T cells in the blood of the indicated MBMCs before and after infection. (c) Representative flow cytometry plots of CD3+ CD8+ T cells from the lungs of the indicated MBMCs four weeks after infection. (d) Total number of WT (CD45.1+) or KO (CD45.2+) CD8+ T cells in the lungs of MBMCs either uninfected or 4 weeks after Mtb infection. (e) The number of TB10.44-11/Kb tetramer+ (Tetramer+) CD8+ T cells that are WT or KO in the lungs of infected 1:1 chimeras. Each bar represents the mean ± SEM (n = 4-5 mice per group for the uninfected groups and n = 8-10 mice per group for the infected groups). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 (paired Student's t-test). Data are representative of three independent experiments for the infected groups and two independent experiments for the uninfected groups. Uninf. indicates “uninfected”.

By determining the ratio of WT and KO CD8+ T cells in the blood, we tracked the proportion of WT and KO CD8+ T cells in the same mice before and after infection with Mtb. Four weeks after infection, IL-12R−/−, IFNAR−/−, and IL-27R−/− CD8+ T cells were underrepresented in blood relative to WT cells (Fig. 3a and 3b). This was also true in the lungs of infected mice, where the percentage of IL-12R−/−, IFNAR−/−, and IL-27R−/− CD8+ T cells were reduced relative to their WT counterparts in the same mouse (Fig. 3c). Importantly, the dramatic increase in the number of CD8+ T cells in the lungs of Mtb infected mice was dependent upon all three cytokine receptors (Fig. 3d). Although CD8+ T cell expansion was suboptimal in the absence of IFNAR and IL-27R, it was nearly completely abrogated in the absence of IL-12R. Tracking CD8+ T cells specific for the immunodominant epitope TB10.44-11 (Rv0288; EsxH) also revealed similar reductions in the number of Ag-specific CD8+ T cells in the lungs (Fig. 3e). Though the number of Ag-specific receptor KO CD8+ T cells is reduced, the percentages of TB10.44-11-specific cells within the KO populations is comparable to the percentages within the WT populations (see below, Fig. 5b). Thus, the reduced number of Ag-specific cells reflects the global reduction in receptor KO CD8+ T cells. Overall, these data show that all three cytokine receptors (IL-12R, IFNAR, and IL-27R) are necessary for the expansion and accumulation of CD8+ T cells in the lungs during tuberculosis. Of these cytokines, IL-12 appears to have the greatest impact, as in the absence of IL-12R, CD8+ T cells underwent little expansion; however, type I IFN and IL-27 clearly have crucial roles in regulating the magnitude of CD8+ T cell responses.

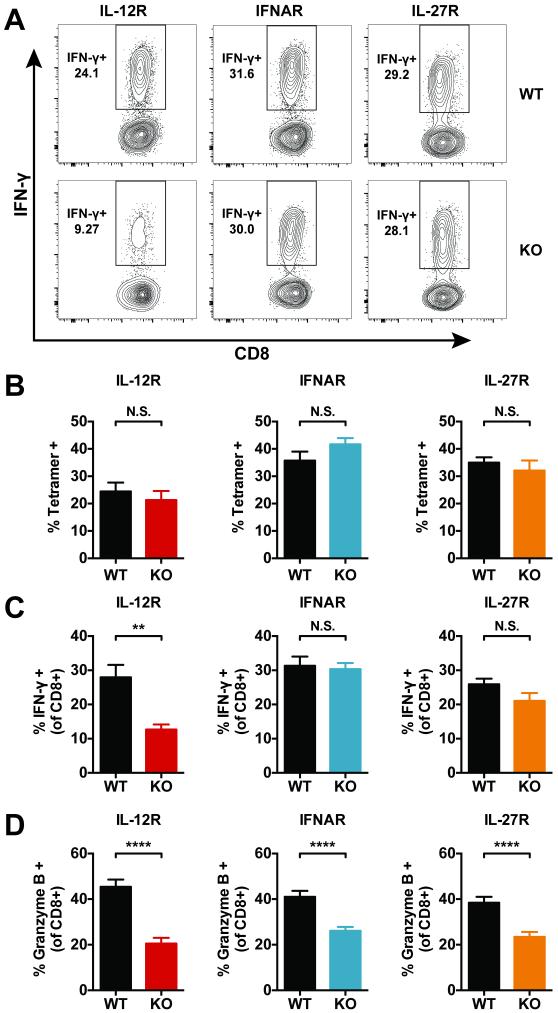

Figure 5. Signal 3 cytokines affect IFN-γ production and granzyme B expression by CD8+ T cells during tuberculosis.

(a) Representative flow cytometry plots of lung CD8+ T cells of the indicated genotype 4 weeks after infection. Single cell lung preparations were stimulated ex vivo with TB10.44-11 peptide prior to IFN-γ analysis. (b) The percentage of TB10.44-11-specific CD8+ T cells within the WT (CD45.1+) or KO (CD45.2+) populations based on positive staining with TB10.44-11/Kb tetramers (Tetramer+). Though the overall number of Ag-specific KO CD8+ T cells is reduced in each group of MBMCs (Figure 3), the percentage of Tetramer+ cells remains comparable within the WT and KO populations. (c) The percentage of WT and KO CD8+ T cells positive for intracellular IFN-γ after ex vivo stimulation with TB10.44-11 peptide. (d) The percentage of WT and KO CD8+ T cells positive for intracellular granzyme B staining. Each bar represents the mean ± SEM (n = 9-10 mice per group) **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 and N.S. indicates “not significant” (paired Student's t-test). Data are representative of three independent experiments.

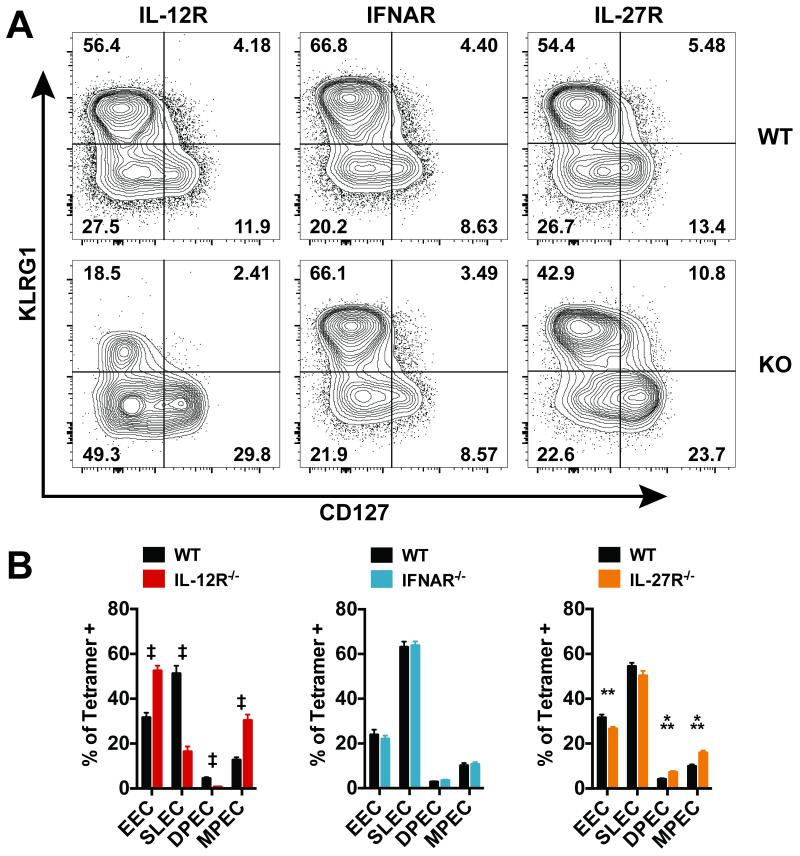

IL-12 and IL-27 influence the differentiation of effector CD8+ T cells during tuberculosis

Following priming, CD8+ T cells can differentiate into several effector subpopulations that are distinguishable by their expression of the cell surface markers killer cell lectin-like receptor subfamily G, member 1 (KLRG1) and interleukin-7 receptor (CD127) (29, 30). Recently primed effector cells lack expression of both KLRG1 and CD127 and are known as early effector cells (EECs) (17). These cells can give rise to two effector subpopulations: short-lived effector cells (SLEC – KLRG1HiCD127Lo) and memory precursor effector cells (MPEC – KLRG1LoCD127Hi) (31). MPECs are the population with the greatest potential to generate long-lived memory cells (29, 30, 32). A fourth subpopulation expresses both KLRG1 and CD127 (DPEC – double positive effector cell); however, the functional relevance of these cells remains unclear.

The inflammatory environment elicited by each pathogen influences these cell fate decisions, and IL-12, type I IFN and IL-27 can influence CD8+ T cell differentiation during different infections (15, 17, 33). The effects of these cytokines on CD8+ T cell differentiation were determined during tuberculosis using the MBMC model. Four weeks after infection, we measured the cell surface expression of KLRG1 and CD127 on WT and cytokine receptor KO Ag-specific CD8+ T cells, which were identified using TB10.44-11/Kb tetramers. Following Mtb infection, WT CD8+ T cells primarily adopt a SLEC (~53–60%) and EEC (~26–32%) phenotype with fewer cells expressing CD127 (Fig. 4a, top row). Loss of IL-12 signaling severely reduced the population of SLECs, while the frequency of MPECs increased, as manifested by a loss KLRG1+ cells and increased expression of CD127 (Fig. 4a and b). In contrast, loss of type I IFN signaling had no impact on the relative proportion of effector subpopulations (Fig. 4a and b). Although IL-27 signaling had no effect on SLEC differentiation, it had a small but significant inhibitory effect on CD127 expression, leading to an increased proportion of MPECs in the absence of IL-27 signaling (Fig. 4a and b). Thus, of these three pro-inflammatory cytokines, IL-12 is the main driver of CD8+ T cell terminal differentiation during tuberculosis; in its absence, not only is there a failure of CD8+ T cell expansion (Fig. 3d) but also a substantial skewing of effector subpopulations that leads to a loss of SLECs.

Figure 4. IL-12 is the dominant cytokine affecting effector CD8+ T cell differentiation during tuberculosis.

(a) Representative flow cytometry plots of lung CD8+ TB10.44-11/Kb tetramer+ T cells of the indicated genotype 4 weeks after infection in MBMCs. (b) Analysis of CD8+ TB10.44-11/Kb tetramer+ cells based on KLRG1 and CD127 staining (EEC – Early Effector Cells, KLRG1Lo CD127Lo; SLEC – Short-Lived Effector Cells, KLRG1Hi CD127Lo; DPEC – Double Positive Effector Cell, KLRG1Hi CD127Hi; MPEC – Memory Precursor Effector Cell, KLRG1Lo CD127Hi) Each bar represents the mean ± SEM (n = 9-10 mice per group) **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ‡P < 0.0001 (paired Student's t-test). Data are representative of three independent experiments.

IL-12, type I IFN, and IL-27 have distinct and overlapping effects on CD8+ T cell function during tuberculosis

IL-12, type I IFN, and IL-27 can all impact the acquisition of effector functions by CD8+ T cells; however, their direct effects on CD8+ T cell function during tuberculosis have not been examined. Interferon gamma (IFN-γ) is a particularly important cytokine during tuberculosis, and CD8+ T cells are a source of this protective cytokine (24, 34). We stimulated lung cells from MBMCs ex vivo with the TB10.44-11 minimal peptide epitope and performed intracellular cytokine staining to measure the percentage of Ag-specific CD8+ T cells that can produce IFN-γ. As controls, lung cells were also left unstimulated or stimulated with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 monoclonal antibodies. Significant levels of cytokine production were not observed in the unstimulated samples. Of the three cytokines, only IL-12 signaling was essential for IFN-γ production by lung CD8+ T cells four weeks after Mtb infection (Fig. 5a and c). Though the number of Ag-specific receptor KO CD8+ T cells is diminished in the MBMCs (Fig. 3), KO CD8+ T cells are still elicited in response to infection, and the percentages of TB10.44-11-specific cells within the KO populations is comparable to the percentages within the WT populations (Fig. 5b). Thus, the reduced percentage of IL-12R−/− CD8+ T cells producing IFN-γ is the result of a functional defect and is not caused by a diminished percentage of Ag-specific cells within the KO population.

In addition to cytokine production, IL-12, type I IFN, and IL-27 can alter the cytolytic activity of CD8+ T cells. To address the role of these cytokines in regulating cytolytic function, we analyzed intracellular granzyme B levels in CD8+ T cells from the lungs of MBMCs. Surprisingly, the loss of receptor signaling for all three cytokines resulted in a decreased percentage of cells positive for granzyme B (Fig. 5d). These findings suggest that all three cytokines are required for optimal cytolytic function.

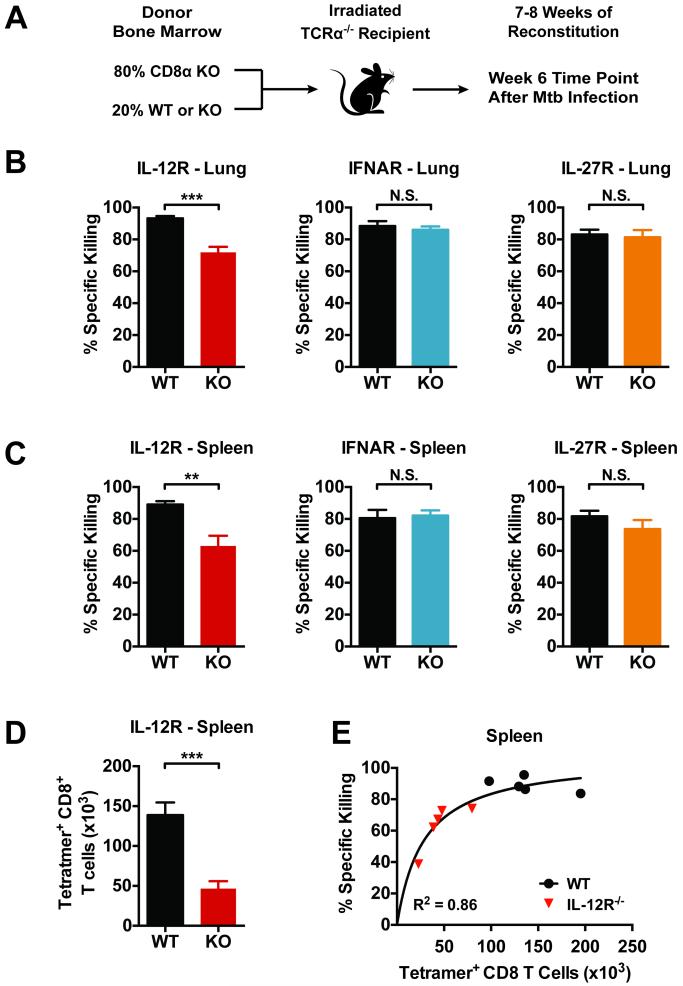

Following Mtb infection, elicited CD8+ T cells remain cytolytic in the absence of IL-12, type I IFN, or IL-27 signaling

With the goal of examining cytolytic function, we used a second strategy to generate BM chimeras in which all the CD8+ T cells lacked the cytokine receptors of interest (Fig. 6a). Briefly, TCRα−/− mice were lethally irradiated and reconstituted with a mixture of donor cells consisting of 80% CD8α−/− BM and 20% of either WT or receptor KO BM (IL-12R−/−, IFNAR−/−, or IL-27R−/−). In the resulting “4:1” chimeric mice, CD8+ T cells can only be derived from either the donor WT or cytokine receptor KO BM, depending on the experimental group (Fig. 6a). Thus, these experiments differ from the MBMCs, because the WT and KO groups are separate sets of mice. CD8+ T cells developed normally in these mice and responded robustly to aerosol infection with Mtb. After six weeks of infection, the chimeras with IL-12R−/−, IFNAR−/−, or IL-27R−/− CD8+ T cells had a similar bacterial burden as control chimeras with WT CD8+ T cells and all chimeras survived. These observations were anticipated given that mice completely lacking CD8+ T cells only exhibit increased susceptibility to tuberculosis at very late time points (35).

Figure 6. CD8+ T cells retain cytolytic activity in the absence of IL-12, type 1 IFN, or IL-27 signaling.

(a) Schema for the production of 4:1 MBMCs in which CD8+ T cells are either WT or KO, but the other hematopoietic cells are ~80–100% WT. (b and c) In vivo cytolytic activity of TB10.44-11-specific CD8+ T cells in the lungs (b) and spleens (c) of infected 4:1 chimeras 6 weeks post-infection. (d) The total number CD8+ TB10.44-11/Kb tetramer+ (Tetramer+) T cells in the spleens of the indicated 4:1 chimeras 6 weeks post-infection. (E) Nonlinear regression analysis of TB10.44-11-specific CD8+ T cell number vs. specific killing comparing WT to IL-12R−/− 4:1 chimeras. Both data sets are best fit by a single curve (R2=0.8601). Specific killing was calculated as described in the Materials and Methods. Each bar represents the mean ± SEM (n = 4-5 mice per group) *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 (unpaired Student's t-test). Data are representative of two independent experiments.

An in vivo cytotoxicity assay was performed with the 4:1 chimeras by assessing the specific killing of fluorescently labeled target splenocytes loaded with TB10.44-11 as previously published (21). Diminished specific killing of targets was observed only in 4:1 chimeras with IL-12R−/− CD8+ T cells; otherwise, efficient killing of target cells was detected in the both the lungs and spleens of infected mice (Fig.6 b and c). Since IL-12R−/− CD8+ T cells have the most profound defect in the expansion of Ag-specific cells (Fig. 6d), we wished to determine whether the reduced specific killing resulted from fewer Ag-specific CD8+ T cells or actually reflected a dysfunction of IL-12R−/− cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL). By plotting the absolute number of TB10.44-11-specifc CD8+ T cells in the spleen versus specific killing, it was apparent that cell number had a great impact on target cell lysis (Fig. 6e). This correlation was particularly robust in the spleens where a higher number of target cells were recovered, but similar results were observed in the lungs (data not shown). These findings indicate that CTL are generated even in the absence of IL-12, type I IFN, or IL-27 signaling, and despite an overall reduction in granzyme B levels, the cells function as effective CTL. Multiple molecules and several different pathways contribute to cytolysis (19, 21); thus, it is likely that, individually, these cytokines do not have a substantial impact on cytolytic function.

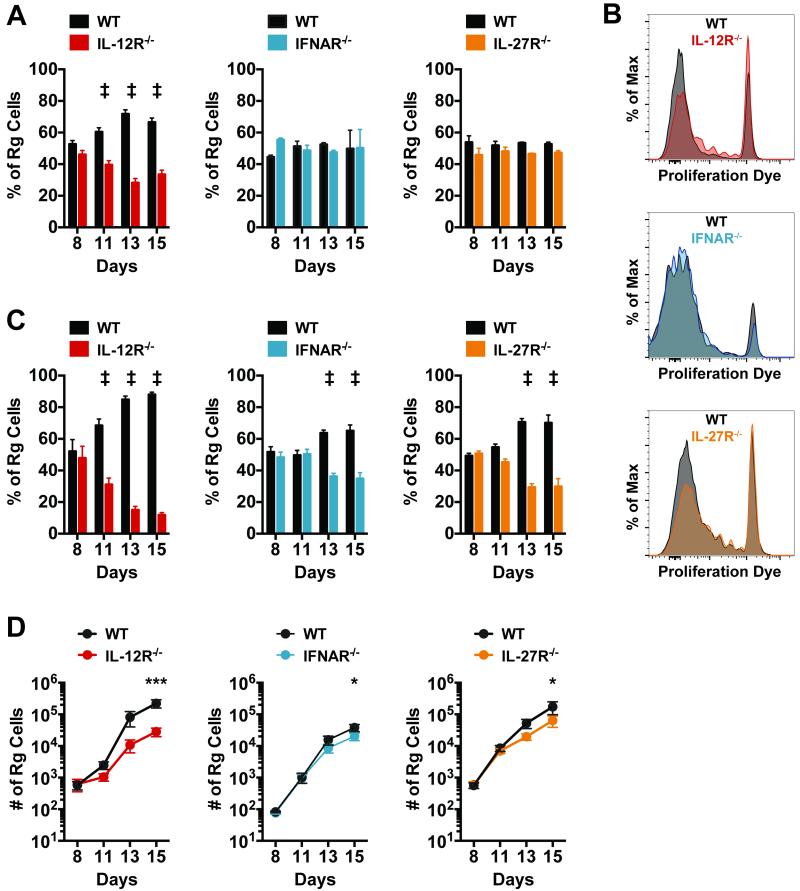

CD8+ T cell priming in the lung draining lymph node requires IL-12, while CD8+ T cell expansion in the lung depends on IL-12, type I IFN, and IL-27

IL-12 and type I IFN, or their combination, provide a necessary third signal for priming CD8+ T cells after infection with different pathogens but their role as “signal 3” cytokines during tuberculosis is unknown. While IL-27 is not usually considered a signal 3 cytokine, it has several of the same attributes as IL-12 and type I IFN. Because IL-12, type I IFN, and IL-27 all influence the magnitude of the CD8+ T cell response during tuberculosis, we determined whether these effects are mediated during T cell priming in the LN or only during T cell expansion in the lungs.

To address this question, we used a retrogenic (Rg) mouse model in which a high percentage of CD8+ T cells express a TCR specific for the immunodominant Ag TB10.44-11 (TB10Rg) (24). A key advantage of TB10Rg mice is that naïve Ag-specific CD8+ T cells can be generated on nearly any genetic background, thus providing a source of naïve TB10.44-11-specific IL-12R−/−, IFNAR−/−, and IL-27R−/− CD8+ T cells. After adoptive transfer of naïve TB10Rg CD8+ T cells, priming is detected in the draining LN approximately 11 days following aerosol infection (24). This delay in T cell priming results from the delayed transfer of Mtb and its antigens from the lung to the draining LN (36–38). To determine the role of IL-12R, IFNAR, and IL-27R signaling in priming, equal numbers of congenically marked WT and receptor KO TB10Rg CD8+ T cells were transferred into recipient mice 7 days after low-dose aerosol Mtb infection, and the ratio of WT and KO TB10Rg CD8+ T cells was measured on days 8, 11, 13, and 15 post infection.

On day 8, the ratio of WT and receptor KO Rg CD8+ T cells was unaltered from the ratio of cells injected at day 7 (Fig. 7a). By day 11 in the mediastinal LN, IL-12R−/− TB10Rg CD8+ T cells were underrepresented relative to WT cells and continued to lag behind through days 13 and 15 (Fig. 7a). Throughout the experiment, IFNAR−/− and IL-27R−/− TB10Rg CD8+ T cells maintained a consistent ratio with WT cells in the LN, indicating that type I IFN and IL-27 are dispensable for CD8+ T cell priming following Mtb infection (Fig. 7a). Surprisingly, IL-12R−/− TB10Rg CD8+ T cells still expanded significantly in the LN, though they did lag behind WT cells. The number of IL-12R−/− TB10Rg CD8+ T cells continued to increase in the LN throughout the time course of this experiment (Supplemental Fig. 1). Furthermore, IL-12R−/− TB10Rg CD8+ T cells in the LN substantially diluted their proliferation dye by day 11 post-transfer, though not as efficiently as WT cells (Fig. 7b). These data indicate that signals other than IL-12 in the LN contribute to CD8+ T cell priming and suggest that additional signal 3 cytokines may exist. Additionally, type I IFN or IL-27 may support priming in the absence of IL-12. IFNAR−/− and IL-27R−/− TB10Rg CD8+ T cells diluted their proliferation dye equivalent to WT cells by day 11, reinforcing that these signals are not needed to prime cells in the LN when IL-12 is present (Fig. 7b).

Figure 7. CD8+ T cell priming in the lung draining lymph node requires IL-12, while CD8+ T cell expansion in the lung depends on IL-12, type I IFN, and IL-27.

Equal numbers of retrogenic TB10.44-11-specific (TB10Rg) CD8+T cells were transferred into mice 7 days after low-dose aerosol infection with Mtb. (a) The percentage of total retrogenic (Rg) cells that were WT or KO for the indicated cytokine receptor in the mediastinal LN on days 8, 11, 13 and 15 following infection. (b) Histograms depicting the dilution of the proliferation dye efluor 450 in TB10Rg cells in the LN at day 11. Each group of samples (WT or KO) was concatenated into a single histogram. (c) The percentage of total retrogenic (Rg) cells that were WT or KO for the indicated cytokine receptor in the lungs at days 8, 11, 13 and 15 following infection. (d) Total number of WT and KO Rg cells detected in the lungs at the indicated time points. Each bar or point represents the mean ± SEM (n = 4-5 mice per group) *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ‡P < 0.0001 (Holm-Šídák multiple comparisons testing following two-way ANOVA). Data are representative of two independent experiments.

In the same priming experiments, the expansion of the transferred cells was monitored in the lungs of recipient mice. Similar to the observations in the LN, IL-12R−/− TB10Rg CD8+ T cells continued to expand over the course of the experiment; however, they underperformed relative to WT cells (Fig. 7c and 7d). This suggests that IL-12 is necessary for the efficient priming of CD8+ T cells in the LN as well as their continued expansion in the lungs. Though type I IFN and IL-27 are dispensable for CD8+ T cell priming, their influence on CD8+ T cell expansion in the lungs could be observed 13 days post infection, as the percentage of IFNAR−/− or IL-27R−/− TB10Rg CD8+ T cells decreased relative to their WT counterparts on days 13 and 15 (Fig. 7c). These data indicate that, while IL-12 promotes CD8+ T cell expansion during priming in the LN, type I IFN and IL-27 primarily act after priming has occurred to expand CD8+ T cells in the lungs during Mtb infection.

Discussion

Numerous T cell subsets participate in the immune response following Mtb infection. T cell responses have different kinetics and magnitudes; they differ in respect to their function and where in the lung they localize. This complicates efforts to understand the relative importance of each T cell subset in mediating protection against tuberculosis. In this respect, the role of CD8+ T cells has been enigmatic. CD8+ T cells were first recognized to be essential for host resistance in the murine model, but are now recognized to be crucial for protection in non-human primates as well (19, 39–41). Mapping of the Mtb epitopes recognized by murine and human CD8+ T cells from infected individuals has characterized many of the antigens that elicit CD8+ T cells during infection and demonstrated dramatic clonal expansions that appear to be driven by TCR affinity (24). CD8+ T cells express potent effector functions and there is potential for vaccine-elicited CD8+ T cells to mediate protection against tuberculosis. However, CD8+ T cells appear to be less effective than CD4+ T cells in mediating resistance, despite similar kinetics (28, 35, 42). There are numerous potential signals that modify T cell responses in a diseased lung – soluble mediators and cell surface signals can have both positive and negative effects on T cell expansion and function (43). While it is commonly accepted that optimal CD8+ T cell responses require a third signal – usually mediated by an inflammatory cytokine – how CD8+ T cells are regulated during chronic inflammation is less well understood (13). Infection with Mtb elicits a complex innate inflammatory response that shapes T cell immunity. We considered the possibility that IL-12, IL-27, and type I IFN, three cytokines produced by infected cells and known to influence host resistance, may have differential effects on CD8+ T cell function. In particular, we sought to determine if any of these cytokines directly limits CD8+ T cell responses during tuberculosis.

Using MBMCs and the adoptive transfer of naïve TB104-11-specific CD8+ T cells, we show that IL-12 is a major positive regulator of the CD8+ T cell response during tuberculosis. Following aerosol infection, IL-12 is essential for efficient CD8+ T cell priming in the LN and subsequent expansion in the lung. IL-12 also promotes the terminal differentiation of SLECs and enhances IFN-γ production. Based on these results, we conclude that IL-12 is the dominant signal 3 cytokine during tuberculosis.

IL-12 does not act alone in the infected host. Instead of seeing inhibition, we demonstrate a direct positive supporting role for both type I IFN and IL-27 in CD8+ T cell expansion. These effects are not observed during the priming of naïve CD8+ T cells in the LN and only become evident once activated CD8+ T cells are recruited to the infected lung. Because they are dispensable for priming, we argue that type I IFN and IL-27 are not acting as signal 3 cytokines. Nevertheless, type I IFN and IL-27 each have a non-redundant role augmenting the magnitude of pulmonary CD8+ T cell responses. This is most evident in the MBMCs, where WT and KO cells are in direct competition within the same inflammatory environment. This complex involvement of multiple inflammatory cytokines is similar to other infections, where IL-12 and type I IFN both support CD8+ T cell expansion (15). In this way, CD8+ T cells reflect the inflammatory environment of the host, responding in different degrees to each cytokine induced by the pathogen.

Type I IFN negatively affects host immunity to Mtb through a number of mechanisms, but few studies have directly addressed the impact of type 1 IFN on T cell function during tuberculosis. Dorhoi et al. examined T cell responses in Mtb-infected IFNAR−/− mice on the 129S2 background and noted no alteration in IFN-γ production by CD4+ or CD8+ T cells (9). In our MBMCs, type I IFN supports CD8+ T cell expansion while having no major effect on the expansion of CD4+ T cells (Fig. 3 and data not shown). We conclude that type I IFN does not directly inhibit T cell function, but rather promotes the expansion of CD8+ T cells in the lungs. Beyond this effect, we did not observed type I IFN to affect CD8+ T cell differentiation or function.

Recently, Torrado et al. examined the expansion of TB10.44-11-specific CD8+ T cells in the lungs of intact IL-27R−/− mice and did not observe a defect in expansion compared to WT controls (44). In our experiments, the effect of IL-27 on CD8+ T cell expansion was far less dramatic than that of IL-12 and was only observable when IL-27R−/− CD8+ T cells were in direct competition with WT cells in the lungs of the same mouse. This was evident in both the MBMC model (Fig. 3) and the co-transfer of WT and IL-27R−/− TB10Rg cells (Fig. 7). We believe these experimental systems are more sensitive at detecting subtle defects in T cell expansion and bypass any confounding differences in the inflammatory response of WT and KO mice.

We were surprised to discover IL-27 did not affect basic CD8+ T cell effector functions. IL-27 is a critical promoter of IFN-γ production by CD8+ T cells in other infections (18); but we did not observe this effect in our model of tuberculosis. It is possible that the dominant role of IL-12 during tuberculosis masks any potential effects of IL-27. However, this hypothesis seems unlikely since during Toxoplasma gondii infection IL-12 promotes the expansion of effector CD8+ T cells while IL-27 is necessary for IFN-γ production (18, 45–47). Thus, IL-27 can be observed to drive IFN-γ production even in the presence of high IL-12 levels in other infections. As IL-27 is clearly dispensable for IFN-γ production by CD8+ T cells during tuberculosis, the effects of IL-27 on CD8+ T cell effector function are likely pathogen-specific. The loss of IL-27 signaling does not influence CD8+ T cell SLEC differentiation. Instead, IL-27R−/− cells were more likely to adopt a DPEC and MPEC phenotype, from which we infer that IL-27 signaling limits CD127 expression. While it is tempting to speculate that IL-27 limits CD8+ memory formation during tuberculosis, this possibility cannot be addressed with our current data.

IL-12, type I IFN, and IL-27 all promote granzyme B production following Mtb infection, but no substantial loss in in vivo cytolytic activity is observed. Mice with only IL-12R−/− CD8+ T cells show reduced specific killing; however, our data indicate this results from reduced CD8+ T cell numbers, not from a reduction in cytolytic function on a per cell basis. In fact, IL-12R−/− CD8+ T cells efficiently lysed targets cells in vivo. The cytolytic activity of IL-12R−/− CD8+ T cells highlights the redundancy of cytokines that regulate cytolytic effector pathways. With multiple cytokines promoting cytolytic activity, the loss of a single cytokine fails to perturb specific killing. These data also suggest that granzyme B levels may not be the best proxy for CTL, since a moderate decrease in granzyme B levels (Fig. 5c) did not correlate with reduced in vivo killing (Fig. 6). Multiple molecules and mechanisms enable cytolysis during tuberculosis including granule-exocytosis, fas/fasL, and TNF (19, 21). During tuberculosis, in vivo cytolytic activity is only marginally affected by the absence of perforin; however, perforin is crucial for host immunity during tuberculosis (21). This indicates that although multiple molecular pathways may be similarly potent at lysing target cells, there may exist differences with respect to their ability to kill pathogens. We were unable to assess perforin expression in these experiments, as a reliable method for intracellular perforin staining in murine cells has been elusive until recently (48). Nonetheless, CD8+ T cells retain a high degree of cytolytic activity even in the absence of IL-12, indicating that cytolysis is a robust effector mechanism found even in dysfunctional cells, such as IL-12R−/− CD8+ T cells.

Using IL-12R, IFNAR, and IL-27R retrogenic mice as a source for naïve Ag-specific CD8+ T cells, we were able to determine how these cytokines affect T cell priming. In contrast to many infections, T cell priming following Mtb infection is delayed until ~days 11–13 following aerosol infection. Furthermore, T cell priming appears to occur only after bacterial dissemination to the draining LN, which occurs ~days 9–11 after infection (24, 36, 38). Thus, there is a window of ~48hrs for the bacteria to stimulate the production of soluble mediators including cytokines that can influence T cell priming. We tracked the fate of naïve TB10Rg CD8+ T cells to determine how IL-12, type I IFN, and IL-27 affects T cell priming during Mtb infection. IL-12 was critical for supporting CD8+ T cell priming; however, naïve IL-12R−/− CD8+ T cells were primed and expanded in all of our experiments. Thus, other signals support CD8+ T cell priming in the absence of IL-12. During tuberculosis, IL-23 can compensate for the absence of IL-12 to promote CD4+ T cell responses (2, 49). As we used IL-12Rβ2−/− cells in all our experiments, IL-23 signaling remained intact. While it is possible that IL-23 supports CD8+ T cell expansion, in vitro experiments have failed to associate IL-23 with signal 3 activity, making it an unlikely candidate (50). During vaccinia virus infection, neither IL-12 nor type I IFN are required to generate CD8+ T cell responses, raising the possibility that additional sources of signal 3 exist (15).

Our data illuminate a portion of the cytokine network regulating CD8+ T cells and illustrate the complex ways in which inflammation shapes adaptive immunity. CD8+ T cells are similar to CD4+ T cells in their requirement for IL-12, but have the opposite response to IL-27 signaling. It is intriguing to consider that IL-27 functions to limit a pathological CD4+ T cell response while simultaneously supporting the expansion of CD8+ T cells. In this way, IL-27 can possibly achieve a balance of IFN-γ-producing cells in the lungs. These issues are crucial not only for understanding how CD8+ T cells function during infection but also how to optimally elicit a protective T cell response by vaccination. In addition to CD4+ T cell help, the subtleties of signal 3 cytokines on durable T cell memory will be important to understand if we hope to design better vaccination strategies in the future.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank G. Cottle, K. Steblenko, and B. Stowell for their expert technical assistance with the mouse experiments. We also thank S. Urban for her thoughtful input on the project, and R. Welsh for generously providing the IFNAR−/− mice.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R21-AI100766-01 and R01-AI106725-01.

Abbreviations used

- −/−

knockout

- BM

bone marrow

- DPEC

Double Positive Effector Cell

- EEC

Early Effector Cells

- KO

knockout

- MBMC

1:1 Mixed Bone Marrow Chimera

- Mtb

Mycobacterium tuberculosis

- MPEC

Memory Precursor Effector Cell

- SLEC

Short-Lived Effector Cells

- WT

wild-type

References

- 1.Cooper AM, Magram J, Ferrante J, Orme IM. Interleukin 12 (IL-12) is crucial to the development of protective immunity in mice intravenously infected with mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Exp. Med. 1997;186:39–45. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.1.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cooper AM, Kipnis A, Turner J, Magram J, Ferrante J, Orme IM. Mice lacking bioactive IL-12 can generate protective, antigen-specific cellular responses to mycobacterial infection only if the IL-12 p40 subunit is present. J. Immunol. 2002;168:1322–1327. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.3.1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pearl JE, Khader SA, Solache A, Gilmartin L, Ghilardi N, deSauvage F, Cooper AM. IL-27 signaling compromises control of bacterial growth in mycobacteria-infected mice. J. Immunol. 2004;173:7490–7496. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.12.7490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hölscher C, Hölscher A, Rückerl D, Yoshimoto T, Yoshida H, Mak T, Saris C, Ehlers S. The IL-27 receptor chain WSX-1 differentially regulates antibacterial immunity and survival during experimental tuberculosis. J. Immunol. 2005;174:3534–3544. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.6.3534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McNab F, Mayer-Barber K, Sher A, Wack A, O'Garra A. Type I interferons in infectious disease. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2015;15:87–103. doi: 10.1038/nri3787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Manca C, Tsenova L, Freeman S, Barczak AK, Tovey M, Murray PJ, Barry C, Kaplan G. Hypervirulent M. tuberculosis W/Beijing strains upregulate type I IFNs and increase expression of negative regulators of the Jak-Stat pathway. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 2005;25:694–701. doi: 10.1089/jir.2005.25.694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ordway D, Henao-Tamayo M, Harton M, Palanisamy G, Troudt J, Shanley C, Basaraba RJ, Orme IM. The hypervirulent Mycobacterium tuberculosis strain HN878 induces a potent TH1 response followed by rapid down-regulation. J. Immunol. 2007;179:522–531. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.1.522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stanley SA, Johndrow JE, Manzanillo P, Cox JS. The Type I IFN response to infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis requires ESX-1-mediated secretion and contributes to pathogenesis. J. Immunol. 2007;178:3143–3152. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.5.3143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dorhoi A, Yeremeev V, Nouailles G, Weiner J, Jörg S, Heinemann E, Oberbeck-Müller D, Knaul JK, Vogelzang A, Reece ST, Hahnke K, Mollenkopf H-J, Brinkmann V, Kaufmann SHE. Type I IFN signaling triggers immunopathology in tuberculosis-susceptible mice by modulating lung phagocyte dynamics. Eur. J. Immunol. 2014;44:2380–2393. doi: 10.1002/eji.201344219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berry MPR, Graham CM, McNab FW, Xu Z, Bloch SAA, Oni T, Wilkinson KA, Banchereau R, Skinner J, Wilkinson RJ, Quinn C, Blankenship D, Dhawan R, Cush JJ, Mejias A, Ramilo O, Kon OM, Pascual V, Banchereau J, Chaussabel D, O'Garra A. An interferon-inducible neutrophil-driven blood transcriptional signature in human tuberculosis. Nature. 2010;466:973–977. doi: 10.1038/nature09247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Curtsinger JM, Schmidt CS, Mondino A, Lins DC, Kedl RM, Jenkins MK, Mescher MF. Inflammatory cytokines provide a third signal for activation of naive CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. J. Immunol. 1999;162:3256–3262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Curtsinger JM, Valenzuela JO, Agarwal P, Lins D, Mescher MF. Type I IFNs provide a third signal to CD8 T cells to stimulate clonal expansion and differentiation. J. Immunol. 2005;174:4465–4469. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.8.4465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mescher MF, Curtsinger JM, Agarwal P, Casey KA, Gerner M, Hammerbeck CD, Popescu F, Xiao Z. Signals required for programming effector and memory development by CD8+ T cells. Immunol. Rev. 2006;211:81–92. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00382.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Keppler SJ, Theil K, Vucikuja S, Aichele P. Effector T-cell differentiation during viral and bacterial infections: Role of direct IL-12 signals for cell fate decision of CD8+ T cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 2009;39:1774–1783. doi: 10.1002/eji.200839093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keppler SJ, Rosenits K, Koegl T, Vucikuja S, Aichele P. Signal 3 cytokines as modulators of primary immune responses during infections: the interplay of type I IFN and IL-12 in CD8 T cell responses. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e40865. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pennock ND, Gapin L, Kedl RM. IL-27 is required for shaping the magnitude, affinity distribution, and memory of T cells responding to subunit immunization. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2014;111:16472–16477. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1407393111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Obar JJ, Jellison ER, Sheridan BS, Blair DA, Pham Q-M, Zickovich JM, Lefrançois L. Pathogen-induced inflammatory environment controls effector and memory CD8+ T cell differentiation. The Journal of Immunology. 2011;187:4967–4978. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mayer KD, Mohrs K, Reiley W, Wittmer S, Kohlmeier JE, Pearl JE, Cooper AM, Johnson LL, Woodland DL, Mohrs M. Cutting edge: T-bet and IL-27R are critical for in vivo IFN-gamma production by CD8 T cells during infection. J. Immunol. 2008;180:693–697. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.2.693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Woodworth JSM, Behar SM. Mycobacterium tuberculosis-specific CD8+ T cells and their role in immunity. Crit. Rev. Immunol. 2006;26:317–352. doi: 10.1615/critrevimmunol.v26.i4.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Flynn JL, Gideon HP, Mattila JT, Lin PL. Immunology studies in non-human primate models of tuberculosis. Immunol. Rev. 2015;264:60–73. doi: 10.1111/imr.12258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Woodworth JS, Wu Y, Behar SM. Mycobacterium tuberculosis-specific CD8+ T cells require perforin to kill target cells and provide protection in vivo. The Journal of Immunology. 2008;181:8595–8603. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.12.8595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Müller U, Steinhoff U, Reis LF, Hemmi S, Pavlovic J, Zinkernagel RM, Aguet M. Functional role of type I and type II interferons in antiviral defense. Science. 1994;264:1918–1921. doi: 10.1126/science.8009221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marshall HD, Urban SL, Welsh RM. Virus-induced transient immune suppression and the inhibition of T cell proliferation by type I interferon. Journal of Virology. 2011;85:5929–5939. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02516-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nunes-Alves C, Booty MG, Carpenter SM, Rothchild AC, Martin CJ, Desjardins D, Steblenko K, Kløverpris HN, Madansein R, Ramsuran D, Leslie A, Correia-Neves M, Behar SM. Human and Murine Clonal CD8+ T Cell Expansions Arise during Tuberculosis Because of TCR Selection. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11:e1004849. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Holst J, Szymczak-Workman AL, Vignali KM, Burton AR, Workman CJ, Vignali DAA. Generation of T-cell receptor retrogenic mice. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:406–417. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kang DD, Lin Y, Moreno J-R, Randall TD, Khader SA. Profiling early lung immune responses in the mouse model of tuberculosis. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e16161. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mayer-Barber KD, Andrade BB, Oland SD, Amaral EP, Barber DL, Gonzales J, Derrick SC, Shi R, Kumar NP, Wei W, Yuan X, Zhang G, Cai Y, Babu S, Catalfamo M, Salazar AM, Via LE, Barry CE, Sher A. Host-directed therapy of tuberculosis based on interleukin-1 and type I interferon crosstalk. Nature. 2014;511:99–103. doi: 10.1038/nature13489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Woodworth JS, Shin D, Volman M, Nunes-Alves C, Fortune SM, Behar SM. Mycobacterium tuberculosis directs immunofocusing of CD8+ T cell responses despite vaccination. The Journal of Immunology. 2011;186:1627–1637. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Joshi NS, Cui W, Chandele A, Lee HK, Urso DR, Hagman J, Gapin L, Kaech SM. Inflammation directs memory precursor and short-lived effector CD8(+) T cell fates via the graded expression of T-bet transcription factor. Immunity. 2007;27:281–295. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sarkar S, Kalia V, Haining WN, Konieczny BT, Subramaniam S, Ahmed R. Functional and genomic profiling of effector CD8 T cell subsets with distinct memory fates. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2008;205:625–640. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lefrançois L, Obar JJ. Once a killer, always a killer: from cytotoxic T cell to memory cell. Immunol. Rev. 2010;235:206–218. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2010.00895.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kaech SM, Tan JT, Wherry EJ, Konieczny BT, Surh CD, Ahmed R. Selective expression of the interleukin 7 receptor identifies effector CD8 T cells that give rise to long-lived memory cells. Nat. Immunol. 2003;4:1191–1198. doi: 10.1038/ni1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Plumlee CR, Sheridan BS, Cicek BB, Lefrançois L. Environmental cues dictate the fate of individual CD8(+) T cells responding to infection. Immunity. 2013;39:347–356. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Serbina NV, Flynn JL. Early emergence of CD8(+) T cells primed for production of type 1 cytokines in the lungs of Mycobacterium tuberculosis-infected mice. Infection and Immunity. 1999;67:3980–3988. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.8.3980-3988.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mogues T, Goodrich ME, Ryan L, LaCourse R, North RJ. The relative importance of T cell subsets in immunity and immunopathology of airborne Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in mice. J. Exp. Med. 2001;193:271–280. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.3.271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chackerian AA, Alt JM, Perera TV, Dascher CC, Behar SM. Dissemination of Mycobacterium tuberculosis is influenced by host factors and precedes the initiation of T-cell immunity. Infection and Immunity. 2002;70:4501–4509. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.8.4501-4509.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tian T, Woodworth J, Sköld M, Behar SM. In vivo depletion of CD11c+ cells delays the CD4+ T cell response to Mycobacterium tuberculosis and exacerbates the outcome of infection. J. Immunol. 2005;175:3268–3272. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.5.3268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wolf AJ, Desvignes L, Linas B, Banaiee N, Tamura T, Takatsu K, Ernst JD. Initiation of the adaptive immune response to Mycobacterium tuberculosis depends on antigen production in the local lymph node, not the lungs. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2008;205:105–115. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Flynn JL, Goldstein MM, Triebold KJ, Koller B, Bloom BR. Major histocompatibility complex class I-restricted T cells are required for resistance to Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1992;89:12013–12017. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.24.12013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Behar SM, Dascher CC, Grusby MJ, Wang CR, Brenner MB. Susceptibility of mice deficient in CD1D or TAP1 to infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Exp. Med. 1999;189:1973–1980. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.12.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen CY, Huang D, Wang RC, Shen L, Zeng G, Yao S, Shen Y, Halliday L, Fortman J, McAllister M, Estep J, Hunt R, Vasconcelos D, Du G, Porcelli SA, Larsen MH, Jacobs WR, Haynes BF, Letvin NL, Chen ZW. A critical role for CD8 T cells in a nonhuman primate model of tuberculosis. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000392. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kamath AB, Woodworth J, Xiong X, Taylor C, Weng Y, Behar SM. Cytolytic CD8+ T cells recognizing CFP10 are recruited to the lung after Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. J. Exp. Med. 2004;200:1479–1489. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Behar SM, Carpenter SM, Booty MG, Barber DL, Jayaraman P. Orchestration of pulmonary T cell immunity during Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection: immunity interruptus. Seminars in Immunology. 2014;26:559–577. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2014.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Torrado E, Fountain JJ, Liao M, Tighe M, Reiley WW, Lai RP, Meintjes G, Pearl JE, Chen X, Zak DE, Thompson EG, Aderem A, Ghilardi N, Solache A, McKinstry KK, Strutt TM, Wilkinson RJ, Swain SL, Cooper AM. Interleukin 27R regulates CD4+ T cell phenotype and impacts protective immunity during Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2015 doi: 10.1084/jem.20141520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wilson DC, Matthews S, Yap GS. IL-12 signaling drives CD8+ T cell IFN-gamma production and differentiation of KLRG1+ effector subpopulations during Toxoplasma gondii Infection. J. Immunol. 2008;180:5935–5945. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.9.5935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sher A, Collazzo C, Scanga C, Jankovic D, Yap G, Aliberti J. Induction and regulation of IL-12-dependent host resistance to Toxoplasma gondii. Immunol Res. 2003;27:521–528. doi: 10.1385/IR:27:2-3:521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bhadra R, Gigley JP, Khan IA. The CD8 T-cell road to immunotherapy of toxoplasmosis. Immunotherapy. 2011;3:789–801. doi: 10.2217/imt.11.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brennan AJ, House IG, Oliaro J, Ramsbottom KM, Hagn M, Yagita H, Trapani JA, Voskoboinik I. A method for detecting intracellular perforin in mouse lymphocytes. The Journal of Immunology. 2014;193:5744–5750. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1402207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Khader SA, Pearl JE, Sakamoto K, Gilmartin L, Bell GK, Jelley-Gibbs DM, Ghilardi N, deSauvage F, Cooper AM. IL-23 compensates for the absence of IL-12p70 and is essential for the IL-17 response during tuberculosis but is dispensable for protection and antigen-specific IFN-gamma responses if IL-12p70 is available. J. Immunol. 2005;175:788–795. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.2.788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xiao Z, Casey KA, Jameson SC, Curtsinger JM, Mescher MF. Programming for CD8 T cell memory development requires IL-12 or type I IFN. The Journal of Immunology. 2009;182:2786–2794. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.