Abstract

Key points

Transient receptor potential vanilloid type 1 (TRPV1) receptors transduce noxious thermal stimuli and are responsible for the thermal hyperalgesia associated with inflammatory pain.

A large population of dorsal root ganglia (DRG) neurons, including the C low threshold mechanoreceptors (C‐LTMRs), express tyrosine hydroxylase, and probably release dopamine.

We found that dopamine and SKF 81297 (an agonist at D1/D5 receptors), but not quinpirole (an agonist at D2 receptors), downregulate the activity of TRPV1 channels in DRG neurons.

The inhibitory effect of SKF 81297 on TRPV1 channels was strongly dependent on external calcium and preferentially linked to calcium–calmodulin‐dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII).

We suggest that modulation of TRPV1 channels by dopamine in nociceptive neurons may represent a way for dopamine to modulate incoming noxious stimuli.

Abstract

The transient receptor potential vanilloid type 1 (TRPV1) receptor plays a key role in the modulation of nociceptor excitability. To address whether dopamine can modulate the activity of TRPV1 channels in nociceptive neurons, the effects of dopamine and dopamine receptor agonists were tested on the capsaicin‐activated current recorded from acutely dissociated small diameter (<27 μm) dorsal root ganglia (DRG) neurons. Dopamine or SKF 81297 (an agonist at D1/D5 receptors), caused inhibition of both inward and outward currents by ∼60% and ∼48%, respectively. The effect of SKF 81297 was reversed by SCH 23390 (an antagonist at D1/D5 receptors), confirming that it was mediated by activation of D1/D5 dopamine receptors. In contrast, quinpirole (an agonist at D2 receptors) had no significant effect on the capsaicin‐activated current. Inhibition of the capsaicin‐activated current by SKF 81297 was mediated by G protein coupled receptors (GPCRs), and highly dependent on external calcium. The inhibitory effect of SKF 81297 on the capsaicin‐activated current was not affected when the protein kinase A (PKA) activity was blocked with H89, or when the protein kinase C (PKC) activity was blocked with bisindolylmaleimide II (BIM). In contrast, when the calcium–calmodulin‐dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) was blocked with KN‐93, the inhibitory effect of SKF 81297 on the capsaicin‐activated current was greatly reduced, suggesting that activation of D1/D5 dopamine receptors may be preferentially linked to CaMKII activity. We suggest that modulation of TRPV1 channels by dopamine in nociceptive neurons may represent a way for dopamine to modulate incoming noxious stimuli.

Key points

Transient receptor potential vanilloid type 1 (TRPV1) receptors transduce noxious thermal stimuli and are responsible for the thermal hyperalgesia associated with inflammatory pain.

A large population of dorsal root ganglia (DRG) neurons, including the C low threshold mechanoreceptors (C‐LTMRs), express tyrosine hydroxylase, and probably release dopamine.

We found that dopamine and SKF 81297 (an agonist at D1/D5 receptors), but not quinpirole (an agonist at D2 receptors), downregulate the activity of TRPV1 channels in DRG neurons.

The inhibitory effect of SKF 81297 on TRPV1 channels was strongly dependent on external calcium and preferentially linked to calcium–calmodulin‐dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII).

We suggest that modulation of TRPV1 channels by dopamine in nociceptive neurons may represent a way for dopamine to modulate incoming noxious stimuli.

Abbreviations

- AADC

aromatic acid decarboxylase

- BIM

sisindolylmaleimide II

- CaMKII

calcium–calmodulin‐dependent protein kinase II

- C‐LTMRs

C low threshold mechanoreceptors

- DBH

dopamine β‐hydroxylase

- DOPAC

dihydroxyphenylacetic acid

- DRG

dorsal root ganglia

- EPSC

excitatory postsynaptic current

- GPCRs

G protein coupled receptors

- HVA

homovanillic acid

- IB4

isolectin B4

- PKA

protein kinase A

- PKC

protein kinase C

- PLC

phospholipase C

- TG

trigeminal ganglia

- TH

tyrosine hydroxylase

- TRPV1

transient receptor potential vanilloid type 1

- TTX‐R

tetrodotoxin‐resistant

Introduction

The transient receptor potential vanilloid type 1 (TRPV1) receptor is a polymodal molecular integrator in the pain pathway preferentially expressed in Aδ‐ and C‐fibre nociceptors in dorsal root ganglia (DRG) and trigeminal ganglia (TG) (Szallasi et al. 1995; Caterina et al. 1997; Cavanaugh et al. 2011). The TRPV1 channel is a non‐selective cation channel that can be activated by vanilloid compounds (i.e. capsaicin and resineferatoxin), endogenous lipids such as anandamide, protons (Ahern et al. 2005; Dhaka et al. 2009), polyamines (Ahern et al. 2006), and noxious heat (Cesare & McNaughton, 1996; Caterina et al. 1997; Caterina & Julius, 2001). Studies with TRPV1 knockout mice have provided strong support for a major contribution of TRPV1 channels to thermal hyperalgesia associated with inflammatory pain (Caterina et al. 2000; Davis et al. 2000).

A large population of DRG neurons, including the C low threshold mechanoreceptors (C‐LTMRs) specialized in detecting low‐threshold mechanosensory stimuli and those innervating pelvic organs (Price & Mudge, 1983; Philippe et al. 1993; Brumovsky et al. 2006, 2012; Li et al. 2011) express tyrosine hydroxylase (TH), the rate limiting enzyme in the synthesis of catecholamines. The C‐LTMRs represent a molecularly distinct population of non‐peptidergic, small‐diameter sensory neurons which do not express TRPV1 channels (Li et al. 2011). They can be activated by stretch or indentation of the skin or deflection of air follicles, and play a major role in the affective component of touch and the mechanical hypersensitivity associated with nerve injury (Seal et al. 2009; Olausson et al. 2010). Although it is not known which catecholamine(s) are synthetized and/or released from TH‐positive DRG neurons, dopamine and its metabolites dihydroxyphenylacetic acid (DOPAC) and homovanillic acid (HVA) have been detected in DRG neurons and in dorsal spinal nerve roots, but not in satellite and Schwann cells (Lackovic & Neff, 1980; Philippe et al. 1993; Weil‐Fugazza et al. 1993). This supports the possibility that TH‐positive DRG neurons may release dopamine both in the dorsal root ganglia and in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord. In addition to possible release of dopamine by sensory neurons, dopamine is released in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord by supraspinal descending dopaminergic projections (Skagerberg et al. 1982; Ridet et al. 1992; Holstege et al. 1996; Qu et al. 2006; Benarroch, 2008; Koblinger et al. 2014).

A functional role for dopamine in the pain pathway is supported by several lines of evidence: (i) dopamine receptors are expressed in DRG neurons and spinal cord (Xie et al. 1998; Zhu et al. 2007; Galbavy et al. 2013); (ii) recordings from neurons in lamina II–III in the dorsal horn spinal cord have suggested a postsynaptic effect of dopamine mediated by D2 dopamine receptors (Tamae et al. 2005; Taniguchi et al. 2011); (iii) behavioral studies in intact animals support antinociceptive actions of dopamine during acute pain (Jensen & Yaksh, 1984; Barasi & Duggal, 1985), as well as in the setting of injury or inflammation (Wei et al. 2009; Gao et al. 2001; Cobacho et al. 2010); (iv) a recent behavioral pharmacological study supports a role for dopamine in a model of hyperalgesic priming (Kim et al. 2015).

In the dorsal root ganglia, dopamine has been shown to modulate the activity of calcium channels (Marchetti et al. 1986; Formenti et al. 1993, 1998) and the intrinsic excitability of DRG neurons (Gallagher et al. 1980; Abramets & Samoilovich, 1991; Molokanova & Tamarova, 1995). Recently we have provided evidence that stimulation of D1/D5 dopamine receptors results in reduction of tetrodotoxin‐resistant (TTX‐R) sodium current in nociceptors (Galbavy et al. 2013). Here, using an in vitro preparation of acutely dissociated DRG neurons, we show that dopamine downregulates TRPV1 channels expressed in small diameter (<27 μm) DRG neurons. Pharmacological studies indicate that the effect of dopamine is mediated by G protein coupled receptors (GPCRs), requires binding of dopamine to D1/D5 dopamine receptors, and is mainly dependent on calcium influx and activation of CaMKII.

Methods

Animals

Sprague‐Dawley rats (both male and female) at postnatal days 14–28 were used in this study. All procedures were performed in strict accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health and were approved by Stony Brook University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Rats were anaesthetized with isoflurane prior to decapitation.

Dissociated DRG neurons

Rats were deeply anaesthetized with isoflurane and decapitated. Both thoracic and lumbar segments of the spinal cord were removed and placed in a cold Ca2+, Mg2+‐free Hank's solution containing (in mm): 137 NaCl, 5.3 KCl, 0.33 Na2HPO4, 0.44 KH2PO4, 5 Hepes, 5.5 glucose, pH = 7.4 with NaOH. The bone surrounding the spinal cord was removed and dorsal root ganglia were exposed and pulled out. After removing the roots, ganglia were cut in half and incubated for 20 min at 34°C in Ca2+, Mg2+‐free Hank's solution containing 20 U ml−1 papain (Worthington Biochemical, Lakewood, NJ, USA) and 5 mm dl‐cysteine. Ganglia were then treated for 20 min at 34°C with 3 mg ml−1 collagenase (Type I, Sigma‐Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) and 4 mg ml−1 dispase II (Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, IN, USA) in Ca2+, Mg2+‐free Hank's solution. Ganglia were then washed with Leibovitz's L‐15 medium (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum and 5 mm Hepes. Individual cells were dispersed by mechanical trituration using fire‐polished Pasteur pipettes with decreasing bore size and plated on glass coverslip treated with 30–50 μg ml−1 poly‐d‐lysine. Cells were incubated in the supplemented L‐15 solution at 34°C (in 5% CO2) for 2 h, and then stored at room temperature in Neurobasal medium (Gibco) and used over the next 4–6 h. This protocol yields spherical cell bodies without neurites. The cells can be lifted from the cover slip after establishing the whole‐cell configuration in order to facilitate rapid solution changes using flow pipes. Small DRG neurons (diameters < 27 μm) were chosen for recording. Small DRG neurons were initially selected by measuring the diameter from images captured to a computer by a CCD camera Oly‐150 (Olympus Imaging America Inc., Center Valley, PA, USA) using a video acquisition card (dP dPict Imaging, Inc., Indianapolis, IN, USA). A more accurate measurement of cell diameter was obtained from measurements of whole‐cell capacitance assuming a membrane capacitance of 1 μF cm−2 and spherical shape. Cell capacitance was measured by integrating the average of 5–10 current responses to a –5 mV step from −80 mV filtered at 10 kHz and acquired at 50 kHz.

Cell classification

DRG neurons were first tested for capsaicin sensitivity, and only those responding to capsaicin (52% of those tested), corresponding to a subset of nociceptors (Cardenas et al. 1995; Caterina et al. 1997; Petruska et al. 2000), were used for further experiments. Because nociceptors are neurochemically and functionally distinct (Nagy & Hunt, 1982; Silverman & Kruger, 1990; Stucky & Lewin, 1999; Dirajlal et al. 2003), a further classification was made by testing the ability of TRPV1‐positive DRG neurons to bind the isolectin B4 (IB4) FITC conjugate and classified as peptidergic [IB4(−)] or non‐peptidergic [IB4(+)]. Because there were no obvious differences in the ability of dopamine or SKF 81297 (agonist at D1/D5 dopamine receptors) to inhibit the capsaicin‐activated current between IB4(−) and IB4(+) DRG neurons, data were pooled.

Electrophysiology

Whole‐cell recordings were made with a Multiclamp 700B amplifier (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Patch pipettes were pulled from borosilicate glass (A‐M Systems, Sequim, WA, USA) using a Sutter P97 puller (Sutter Instrument, Novato, CA, USA). The resistance of the patch pipette was 1.8‐2.5 MΩ when filled with the standard internal CsCl‐based solution. The shank of the patch pipette was wrapped with Parafilm to reduce pipette capacitance. In whole‐cell mode, the capacity current was reduced by using the amplifier circuitry. To reduce voltage errors, 70–80% of series resistance compensation was applied. After the whole‐cell configuration was established, the cell was lifted up and placed in front of an array of quartz fibre flow pipes (320 μm internal diameter) glued on an aluminum rod and containing the test solutions. Solutions were changed in ∼1 s by moving the cell from one pipe to another. All experiments were done at room temperature (22 ± 1°C), with the exception of those in Fig. 5 which were carried out at physiological temperature (35 ± 1°C). Solutions were heated with a temperature controller (Warner TC‐344B, Warner Instruments, Hamden, CT, USA).

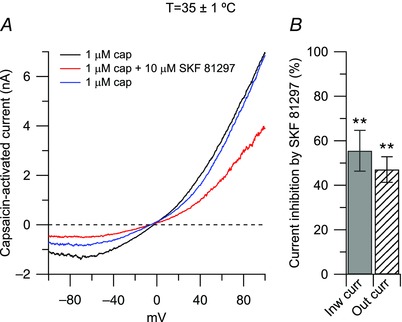

Figure 5. Effects of SKF 81297 on the capsaicin‐activated current at physiological temperature .

A, representative capsaicin‐activated currents recorded at physiological temperature (35 ± 1°C) in control (black trace), in the presence of 10 μm SKF 81297 (agonist at D1/D5 dopamine receptors, red trace), and upon washing out SKF 81297 (blue trace). B, in collected results, 10 μm SKF 81297, applied on top of capsaicin (third application), inhibited the inward current by 56 ± 9% (n = 9), **P < 0.01, paired t test) and the outward current by 47 ± 6% (n = 9), **P < 0.01, paired t test).

Solutions

In voltage clamp experiments a caesium‐based internal solution was used to block outward currents through potassium channels. This solution contained (in mm): 125 CsCl, 10 NaCl, 2 MgCl2, 10 EGTA, 10 Hepes, 14 Tris‐creatine phosphate, 4 Mg‐ATP, and 0.3 Na‐GTP, pH = 7.2 with CsOH.

The standard external solution was a modified Tyrode solution containing (in mm): 151 NaCl, 2 CaCl2, 10 Hepes, 13 glucose, pH 7.4 with NaOH.

Voltage clamp protocols

TRPV1 current was determined as the capsaicin‐activated current by subtracting currents before and after application of 1 μm capsaicin. The current–voltage relationship for TRPV1 current was determined using 2 mV ms−1 voltage ramps. Ramps were delivered in the same sweep from −100 to +100 mV and then from +100 to −100 mV (Fig. 1 A, inset), with the ‘down ramp’ preceded by 50–200 ms at +100 mV. With this procedure, currents carried by voltage‐dependent sodium and calcium channels were largely inactivated before the ‘down ramp’, which allowed more precise determination of TRPV1 currents by eliminating overlapping sodium and calcium channel currents (Puopolo et al. 2013). Current–voltage relationships for TRPV1 channels were therefore determined by using the ‘down ramp’. TRPV1 channels showed some degree of desensitization upon sustained or repeated application of the agonist capsaicin (Caterina et al. 1997). Usually, the desensitization of TRPV1 channels reached its maximum during the first application of capsaicin, with small additional desensitization during the second and third applications (Fig. 1 D). Thus, in order to allow reliable comparison between capsaicin‐activated currents before and after drug treatment, the effect of drugs on the capsaicin‐activated currents was measured during the third application of capsaicin. Capsaicin was applied three times for 40 s with a 1 min interval. The typical protocol is illustrated in Fig. 1 D.

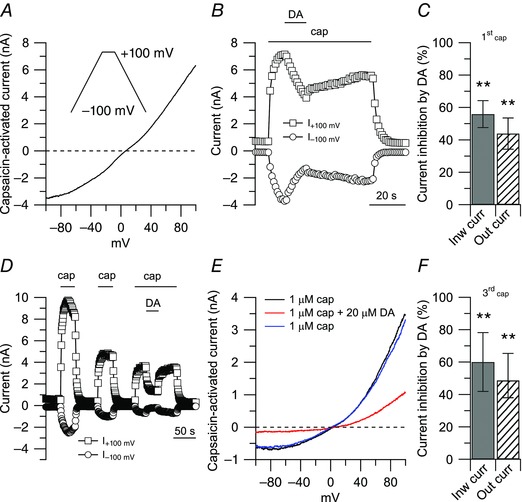

Figure 1. Inhibition of capsaicin‐activated current by dopamine .

A, ionic currents through TRPV1 channels were determined by subtracting currents before and after application of 1 μm capsaicin (cap). Inset: voltage clamp protocol. Ramps (2 mV ms−1) were delivered in the same sweep from −100 to +100 mV and from +100 to −100 mV with the ‘down ramp’ preceded by 50–200 ms at +100 mV to inactivate voltage‐dependent sodium and calcium channels. The trace shown is the capsaicin‐activated current during the ‘down ramp’. B, effects of dopamine (DA) on the capsaicin‐activated current during a single application of capsaicin. Inward and outward currents were measured at −100 and +100 mV, respectively. Note that, because of desensitization of TRPV1 channels induced by capsaicin, the washout after dopamine was not complete. C, in collected results, 20 μm dopamine, applied on top of capsaicin (first application), inhibited the inward current by 56 ± 8% (n = 10, **P < 0.01, paired t test), and the outward current by 44 ± 9% (n = 10, **P < 0.01, paired t test), with respect to control. D, effects of dopamine on the capsaicin‐activated current during repeated application of capsaicin. Note a full recovery upon washing out dopamine. E, capsaicin‐activated currents from the cell in D: 1 μm capsaicin (black trace), 20 μm dopamine on top of capsaicin (red trace), 1 μm capsaicin (upon washing out dopamine, blue trace). F, in collected results, 20 μm dopamine, applied on top of capsaicin (third application), inhibited the inward current by 60 ± 18% (n = 9, **P < 0.01, paired t test) and the outward current by 48 ± 16% (n = 9, **P < 0.01, paired t test), with respect to control.

Data acquisition and analysis

Currents and voltages were controlled and sampled using a Digidata 1440A interface and pCLAMP 10.3 software (Molecular Devices). Current or voltage signals were filtered at 10 kHz (3 dB, 4‐pole Bessel) and digitized at 50 kHz. Analysis was performed using Clampfit 10.3 and IGOR Pro (version 6.2; WaveMetrics, Lake Oswego, OR, USA) using DataAccess (Bruxton, Seattle, WA, USA) to import pCLAMP files into IGOR.

Statistics

Statistical differences between data sets were analysed using Student's t test or one‐way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's post hoc comparison. Differences were considered significant at *P < 0.05 or **P < 0.01. Data are reported as means ± SD.

Results

Dopamine inhibition of TRPV1 current

Ionic current through TRPV1 channels was determined by challenging small DRG neurons with 1 μm capsaicin, and by subtracting currents before and after application of capsaicin (Fig. 1 A). The capsaicin activated‐current showed the typical outward rectification and reversal potential close to 0 mV (1.7 ± 2.4 mV, n = 39), as expected for a non‐selective cation channel (Caterina et al. 1997). When dopamine was applied on top of capsaicin to a small DRG neuron sensitive to capsaicin, there was a substantial inhibition of both outward and inward currents, indicating a strong modulation of TRPV1 channels by dopamine (Fig. 1 B). In collected results, 20 μm dopamine inhibited the inward current (measured at –100 mV) by 56 ± 8% (n = 10) and the outward current (measured at +100 mV) by 44 ± 9% (Fig. 1 C). As previously reported (Caterina et al. 1997), with 2 mm Ca2+ in the external solution, there was some desensitization of TRPV1 channels upon sustained application of capsaicin (usually about 40 s in our experimental conditions). The desensitization of TRPV1 channels induced by capsaicin was reflected in the incomplete recovery of the capsaicin‐activated current upon washing out dopamine (Fig. 1 B), and reduced size during the second and third application of capsaicin (Fig. 1 D). The degree of desensitization usually reached its maximum during the first application of capsaicin, with little additional change during the second and third applications. On average, the capsaicin‐activated current during the second capsaicin application was 70 ± 19% of that during the first application, and the current during a third application was 62 ± 20% of that during the first application (n = 14). Though smaller, capsaicin‐activated current was typically maintained without decay during the second and third applications of capsaicin, allowing a clearer assay of the effect of dopamine without the complication of concurrent desensitization. When neurons were challenged by dopamine during the third application of capsaicin, there was still a robust inhibition of the capsaicin‐activated current induced by dopamine, but also a complete recovery of the effect upon washing out dopamine (Fig. 1 D and E). Thus, to allow the most accurate measurement of the effect of dopamine and other treatments on TRPV1 current without the confounding factor of concurrent desensitization, test compounds were applied during the third application of capsaicin. In collected results (Fig. 1 F), 20 μm dopamine applied during the third application of capsaicin inhibited the capsaicin‐activated inward current by 60 ± 18% (n = 9).

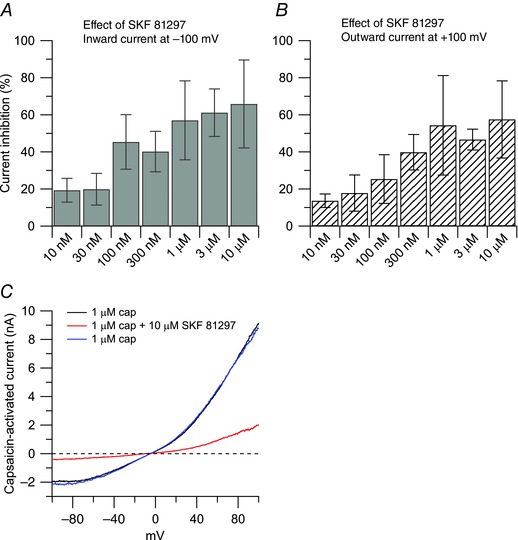

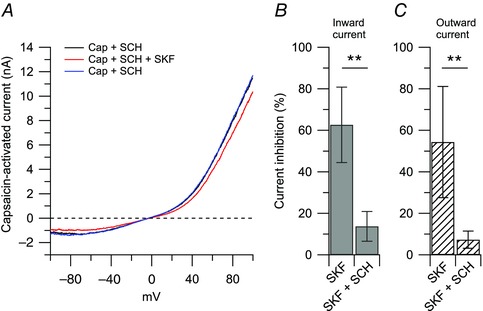

The next step was to identify which dopamine receptors mediate the effect of dopamine. The D1/D5 dopamine receptor agonist SKF 81297 induced inhibition of the capsaicin‐activated current very similar to dopamine, in a dose‐dependent manner (Fig. 2). Capsaicin‐activated inward current was reduced by 57 ± 21% by 1 μm SKF 81297 (n = 5), with no further effect at 3 μm SKF 81297 (reduction by 61 ± 13%, n = 8) or at 10 μm SKF 81297 (reduction by 66 ± 24%, n = 10). The potency and saturation of the effects of SKF 81297 suggest mediation by a receptor rather than a direct blocking effect on the channel. Mediation by a receptor was further tested by applying SKF 81297 in combination with SCH 23390, a selective antagonist at D1/D5 dopamine receptors (Schiffmann et al. 1995; Cantrell et al. 1997). In this series of experiments, the inhibitory effect of 1 μm SKF 81297 on the capsaicin‐activated inward current was reduced from 63 ± 18% (n = 5) when used alone to 14 ± 7% (n = 6) when applied in combination with 100 nm SCH 23390 (Fig. 3). In contrast, the D2 dopamine receptor agonist quinpirole had very little effect on the capsaicin‐activated inward and outward and currents (reduction of inward current by 11 ± 7% after 20 μm quinpirole, Fig. 4, n = 6). Taken together, the data suggest that the inhibitory effect of dopamine on the capsaicin‐activated outward and inward currents is mediated predominantly by D1/D5 dopamine receptors, with little contribution of D2 dopamine receptors.

Figure 2. Inhibition of capsaicin‐activated current by the D1/D5 dopamine receptor agonist SKF 81297 .

Dose‐dependent inhibition of capsaicin‐activated currents by the D1/D5 agonist SKF 81297, showing similar effects on inward and outward currents. Each bar represents an independent experiment. For each concentration, statistical significance was assessed with paired t test by comparing the effect of the drug to its own control. The IC50 was determined using a log inhibitor versus normalized response equation: Y = 100/(1 + 10^((X − logIC50))). A, the inward current was reduced by 19 ± 6% (n = 7, **P < 0.01) by 10 nm SKF 81297; by 20 ± 9% (n = 8, *P < 0.05) by 30 nm SKF 81297; by 45 ± 15% (n = 6, *P < 0.05) by 100 nm SKF 81297, by 40 ± 11% (n = 8, **P < 0.01) by 300 nm SKF 81297; by 63 ± 18% (n = 5, *P < 0.05) by 1 μm SKF 81297; by 61 ± 13% (n = 8, **P < 0.01) by 3 μm SKF 81297; by 66 ± 24% (n = 10, **P < 0.01) by 10 μm SKF 81297. The IC50 for the inward current was determined at 5.5 nm. B, the outward current was reduced by 14 ± 4% (n = 7, **P < 0.01) by 10 nm SKF 81297; by 18 ± 10% (n = 8, **P < 0.01) by 30 nm SKF 81297; by 25 ± 13% (n = 6, *P < 0.05) by 100 nm SKF 81297; by 40 ± 10% (n = 8, **P < 0.01) by 300 nm SKF 81297; by 54 ± 27% (n = 5, *P < 0.05) by 1 μm SKF 81297; by 47 ± 6% (n = 8, **P < 0.01) by 3 μm SKF 81297; by 57 ± 21% (n = 10, *P < 0.05) by 10 μm SKF 81297. The IC50 for the outward current was determined at 3.3 nm. C, representative capsaicin‐activated currents in 1 μm capsaicin (black trace), 10 μm SKF 81297 on top of capsaicin (red trace), 1 μm capsaicin (washout, blue trace).

Figure 3. The effects of SKF 81297 (D1/D5 agonist) were reversed by SCH 23390 (D1/D5 antagonist) .

A, representative capsaicin‐activated current (nA) recorded in the presence of 100 nm SCH 23390 (black trace), after application of 1 μm SKF 81297 on top of SCH 23390 (red trace), and upon removal of SKF 81297 (blue trace). B, in collected results, the inward current was reduced by 63 ± 18% by 1 μm SKF 81297 (n = 5) and by 14 ± 7% by 1 μm SKF 81297 + 100 nm SCH 23390 (n = 6), **P < 0.01, unpaired t test. C, the outward current was reduced by 54 ± 26% by 1 μm SKF 81297 (n = 5) and by 7 ± 4% by 1 μm SKF 81297 + 100 nm SCH 23390 (n = 6), **P < 0.01, unpaired t test.

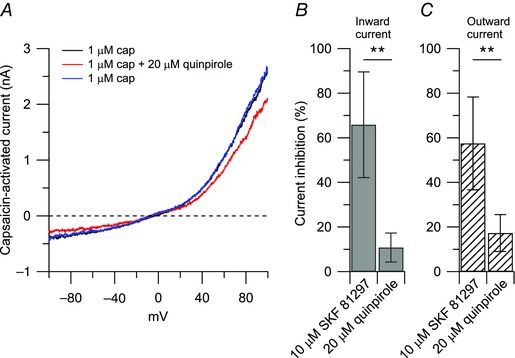

Figure 4. Effects of quinpirole (D2 agonist) on the capsaicin‐activated current .

A, representative capsaicin‐activated currents recorded in control (black trace), in the presence of 20 μm quinpirole (agonist at D2 dopamine receptors, red trace), and upon washing out quinpirole (blue trace). B and C, collected results show comparison of 10 μm SKF 81297 and 20 μm quinpirole effects on the capsaicin‐activated currents. The inward current was reduced by 66 ± 24% (n = 10) by 10 μm SKF 81297 and by 11 ± 7% (n = 5) by 20 μm quinpirole, **P < 0.01, unpaired t test. The outward current was reduced by 57 ± 21% (n = 10) by 10 μm SKF 81297 and by 17 ± 8% (n = 5) by 20 μm quinpirole, **P < 0.01, unpaired t test.

Change in temperature can affect the response of TRPV1 channel to agonists (Neelands et al. 2008), its modulation by protons (Neelands et al. 2010), and the voltage dependence of activation (Voets et al. 2004). We therefore determined whether the inhibitory effect of SKF 81297 on the capsaicin‐activated current was affected by temperature. To this purpose, we tested the effects of SKF 81297 on the capsaicin‐activated current at a more physiological temperature of 35 ± 1°C. As shown in Fig. 5, 10 μm SKF 81297 inhibited the inward current by 56 ± 9% and the outward current by 47 ± 6%, similar to that observed at room temperature.

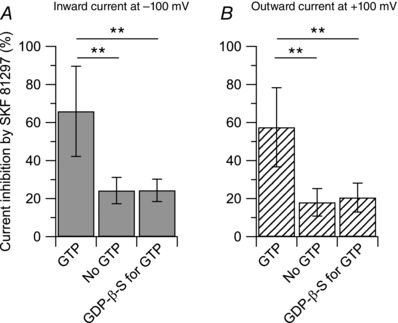

Our standard intracellular solution contained 0.3 mm GTP (see Methods). To test if the effect of SKF 81297 was dependent on GTP, we tested intracellular solutions in which GTP was either removed or replaced by the non‐hydrolysable analogue GDP‐β‐S. When GTP was removed from the intracellular solution, the inhibitory effect of 10 μm SKF 81297 on the capsaicin‐activated inward current was reduced from 64 ± 23% (n = 11) with GTP included in the intracellular solution, to 24 ± 7% (n = 6) with intracellular solution lacking GTP. Similarly, when GTP was replaced by the non‐hydrolysable analogue GDP‐β‐S, the inhibitory effect of 10 μm SKF 81297 on the capsaicin‐activated inward current was reduced to 24 ± 6% (n = 10) (Fig. 6). Taken together, these results confirm that the coupling between dopamine receptors and TRPV1 channels is dependent on GTP acting via G‐proteins.

Figure 6. The effects of SKF 81297 on the capsaicin‐activated current are mediated by G protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) .

Collected results show reduction of the effect of 10 μm SFK 81297 on the capsaicin‐activated inward and outward currents when the usual 0.3 mm GTP was omitted from the internal solution or replaced by the non‐hydrolysable analogue GDP‐β‐S. A, the inward current was reduced by 66 ± 24% (n = 10) with GTP included in the intracellular solution, by 24 ± 7% (n = 6) with intracellular solution lacking GTP, and by 24 ± 6% (n = 10) when GTP was replaced by equimolar concentration of the non‐hydrolysable analogue GDP‐β‐S. No GTP versus GTP: **P < 0.01, one‐way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's post hoc comparison test. GDP‐β‐S for GTP versus GTP: **P < 0.01, one‐way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's post hoc comparison test. B, the outward current was reduced by 57 ± 21% (n = 10) with GTP included in the intracellular solution, by 18 ± 7% (n = 6) with intracellular solution lacking GTP, and by 20 ± 8% (n = 10) when GTP was replaced by equimolar concentration of the non‐hydrolysable analogue GDP‐β‐S. No GTP versus GTP: **P < 0.01, one‐way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's post hoc comparison test. GDP‐β‐S for GTP versus GTP: **P < 0.01, one‐way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's post hoc comparison test.

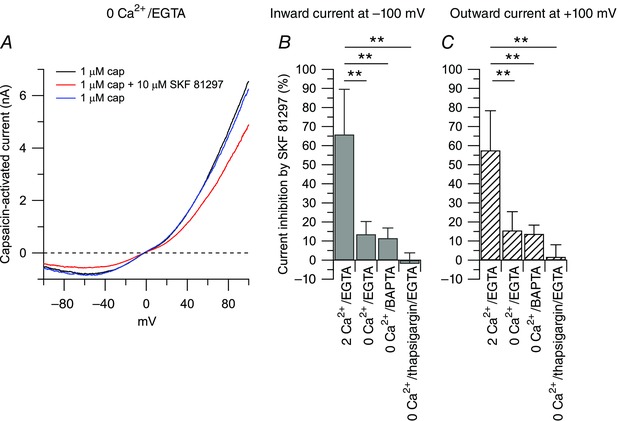

The TRPV1 channel is a non‐selective cation channel with higher permeability to Ca2+ than Na+ () (Caterina et al. 1997; Pedersen et al. 2005). To test whether the inhibitory effect of SFK 81297 on the capsaicin‐activated outward and inward currents was dependent on external calcium, we replaced external Ca2+ (2 mm) with an equimolar concentration of Mg2+, such that the external solution contained a final concentration of 0 mm Ca2+ and 3 mm Mg2+. Using 10 mm EGTA as the intracellular calcium chelator, the inhibitory effect of 10 μm SKF 81297 on the capsaicin‐activated inward current was reduced from 66 ± 24% (n = 10) in 2 mm Ca2+–1 mm Mg2+ to 14 ± 7% (n = 9) in 0 mm Ca2+–3 mm Mg2+ (Fig. 7). The residual inhibitory effect of SKF 81297 on the capsaicin‐activated current in zero external calcium–internal EGTA could reflect the contribution from free calcium that was not chelated by the slow calcium buffer EGTA, or the contribution from calcium released from internal stores, or a calcium‐independent effect. To test these possibilities, first we replaced 10 mm internal EGTA with 10 mm BAPTA, a faster calcium chelator. With internal BAPTA and 0 mm Ca2+–3 mm Mg2+ in the external solution, the inhibitory effect of 10 μm SKF 81297 on the capsaicin‐activated inward current was reduced to 11 ± 5% (n = 11), which was not different from the effect of SKF 81297 observed when the intracellular solution contained the slow calcium buffer EGTA. Second, we used thapsigargin, an inhibitor of the sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+‐ATPase (SERCA). When the intracellular calcium stores were depleted by pre‐incubating DRG neurons with 1 μm thapsigargin for 15 min, the residual inhibitory effect of 10 μm SKF 81297 on the capsaicin‐activated currents observed in zero external calcium–internal EGTA was completely abolished. Taken together, the data suggest that the inhibitory effect of SKF 81297 on the capsaicin‐activated current is strongly Ca2+ dependent.

Figure 7. The effects of SKF 81297 on the capsaicin‐activated current are dependent on calcium .

A, representative capsaicin‐activated currents recorded in 0 Ca2+/EGTA in control (black trace), in the presence of 10 μm SKF 81297 (red trace), and upon washing out SKF 81297 (blue trace). The reversal potential of the capsaicin‐activated current in 0 Ca2+/EGTA was determined at −3.8 ± 2.4 mV (n = 19). Collected results show the effect of 10 μm SKF 81297 on the capsaicin‐activated inward and outward currents with manipulation of external and/or internal calcium. The effect of 10 μm SKF 81297 was determined with 2 mm Ca2+ in the external solution and 10 mm EGTA in the internal solution (2 Ca2+/EGTA), or when 2 mm Ca2+ in the external solution was replaced by 2 mm Mg2+ (0 Ca2+/EGTA), or when the 0 Ca2+ external solution was tested with an internal solution in which 10 mm BAPTA replaced 10 mm EGTA (0 Ca2+/BAPTA), or when the 0 Ca2+/EGTA solution was tested after depleting the internal calcium stores by pre‐incubating the cells with 1 μm thapsigargin for 15 min (0 Ca2+/thapsigargin/EGTA). B, the inward current was reduced by 66 ± 24% (n = 10) in 2 Ca2+/EGTA, by 14 ± 6% (n = 9) in 0 Ca2+/EGTA, by 11 ± 5% (n = 11) in 0 Ca2+/BAPTA, and by −2 ± 5% (n = 11) in 0 Ca2+/thapsigargin/EGTA. 0 Ca2+/EGTA versus 2 Ca2+/EGTA: **P < 0.01, one‐way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's post hoc comparison test. 0 Ca2+/BAPTA versus 2 Ca2+/EGTA: **P < 0.01, one‐way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's post hoc comparison test. 0 Ca2+/thapsigargin/EGTA versus 2 Ca2+/EGTA: **P < 0.01, one‐way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's post hoc comparison test. C, the outward current was reduced by 57 ± 21% (n = 10) in 2 Ca2+/EGTA, by 16 ± 10% (n = 9) in 0 Ca2+/EGTA, by 14 ± 5% (n = 11) in 0 Ca2+/BAPTA, and by 2 ± 6% (n = 11) in 0 Ca2+/thapsigargin/EGTA. 0 Ca2+/EGTA versus 2 Ca2+/EGTA: **P < 0.01, one‐way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's post hoc comparison test. 0 Ca2+/BAPTA versus 2 Ca2+/EGTA: **P < 0.01, one‐way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's post hoc comparison test. 0 Ca2+/thapsigargin/EGTA versus 2 Ca2+/EGTA: **P < 0.01, one‐way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's post hoc comparison test.

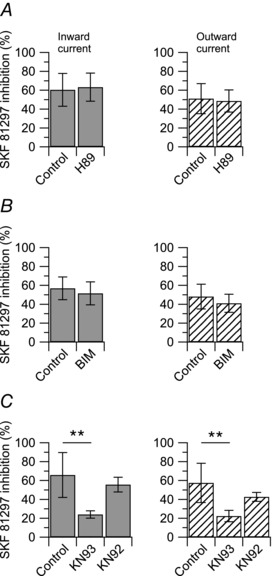

Protein phosphorylation by protein kinase A (PKA), protein kinase C (PKC), and calcium–Calmodulin‐dependent kinase II (CaMKII) has been shown to play a prominent role in the modulation of TRPV1 channels (Vellani et al. 2001; Bhave et al. 2002; Jung et al. 2004; Bangaru et al. 2015). Therefore, we tested whether PKA, or PKC, or CaMKII activity were linked to D1/D5 dopamine receptor activation. When the PKA activity was blocked by pre‐incubating DRG neurons with 1 μm H89 for 30 min, the inhibitory effect of 10 μm SKF 81297 on the capsaicin‐activated current was not affected: 10 μm SKF 81297 inhibited the capsaicin‐activated inward current by 60 ± 17% (n = 10) in control and by 63 ± 14% (n = 9) in H89 (Fig. 8 A). Similar results were obtained when the PKC activity was blocked by pre‐incubating DRG neurons with 1 μm bisindolylmaleimide II (BIM) for 30 min: 10 μm SKF 81297 inhibited the capsaicin‐activated inward current by 57 ± 12% (n = 9) in control and by 49 ± 12% (n = 9) in BMI (Fig. 8 B). In contrast, when the CaMKII activity was blocked by including 10 μm KN‐93 in the patch pipette, the inhibitory effect of 10 μm SKF 81297 on the capsaicin‐activated current was significantly affected: 10 μm SKF 81297 inhibited the capsaicin‐activated inward current by 66 ± 24% (n = 10) in control and by 24 ± 4% (n = 8) with intracellular KN‐93 (Fig. 8 C). When KN‐93 was replaced by the inactive analogue KN‐92 (10 μm), 10 μm SKF 81297 inhibited the capsaicin‐activated inward current by 66 ± 24% (n = 10) in control and by 56 ± 8% (n = 8) with intracellular KN‐92. Taken together, these results suggest that activation of D1/D5 dopamine receptors is linked mainly to CaMKII activity.

Figure 8. Intracellular pathways linked to D1/D5 dopamine receptors activation .

Collected results show the effect of 10 μm SKF 81297 on the capsaicin‐activated inward and outward currents with manipulation of intracellular protein kinases. A, blockade of PKA by pre‐incubation with 1 μm H89 for 30 min. The inward current was reduced by 60 ± 17% (n = 10) in SKF 81297 alone, and by 63 ± 15% (n = 9) following incubation with H89, P = 0.704, unpaired t test. Similarly, the outward current was reduced by 51 ± 16% (n = 10) in SKF 81297 alone, and by 49 ± 12% (n = 9) following incubation with H89, P = 0.711, unpaired t test. B, blockade of PKC by pre‐incubation with 1 μm bisindolylmaleimide II (BIM) for 30 min. The inward current was reduced by 57 ± 12% (n = 9) in SKF 81297 alone, and by 52 ± 12% (n = 9) following incubation with BIM, P = 0.362, unpaired t test. Similarly, the outward current was reduced by 48 ± 13% (n = 9) in SKF 81297 alone, and by 41 ± 10% (n = 9) following incubation with BIM, P = 0.233, unpaired t test. C, blockade of CaMKII with 10 μm KN‐93 or 10 μm KN‐92 (inactive control) included in the patch pipette. The inward current was reduced by 66 ± 24% (n = 10) in SKF alone, by 24 ± 4% (n = 8) with KN‐93, and by 56 ± 8% (n = 8) with KN‐92. KN‐93 versus control: **P < 0.01, one‐way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's post hoc comparison test. KN‐92 versus control: P = 0.306, one‐way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's post hoc comparison test. The outward current was reduced by 57 ± 21% (n = 10) in SKF 81297 alone, by 22 ± 6% (n = 8) with KN‐93, and by 43 ± 5% (n = 8) with KN‐92. KN‐93 versus control: **P < 0.01, one‐way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's post hoc comparison test. KN‐92 versus control: P = 0.058, one‐way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's post hoc comparison test.

Discussion

The data presented here provide strong evidence that dopamine and SKF 81297 (an agonist at D1/D5 dopamine receptors) downregulate the capsaicin‐activated current and the activity of TRPV1 channels expressed in nociceptors. Only small DRG neurons (diameter of 24.4 ± 2.5 μm and cell capacitance of 18.9 ± 3.9 pF, n = 247) sensitive to capsaicin (52% of those tested) were included in the study, suggestive of nociceptors (Cardenas et al. 1995; Petruska et al. 2000; Ho & O'Leary, 2011). Although nociceptors are neurochemically and functionally distinct (Nagy & Hunt, 1982; Silverman & Kruger, 1990; Stucky & Lewin, 1999; Dirajlal et al. 2003), no obvious differences were observed in the inhibitory effect of dopamine or SKF 81297 on the capsaicin‐activated current between peptidergic [IB4(−)] and non‐peptidergic [IB4(+)] DRG neurons. This is consistent with the expression of D1 and D5 dopamine receptors both in peptidergic and non‐peptidergic DRG neurons (Galbavy et al. 2013).

The effect of SKF 81297 on the capsaicin‐activated current was strongly reduced by removing GTP from the intracellular solution or by replacing GTP with GDP‐β‐S, a non‐hydrolysable analogue of GDP (Fig. 6), confirming that the effect of dopamine requires activation of GPCRs as expected for dopamine receptors (Beaulieu & Gainetdinov, 2011).

Several observations support a functional role for dopamine in the dorsal root ganglia. (1) TH, the rate limiting enzyme for the synthesis of cathecolamines, is expressed in a large population of DRG neurons (∼8–10%), including the C‐LTMRs, specialized in detecting low‐threshold mechanosensory stimuli, and those innervating pelvic organs (Price & Mudge, 1983; Philippe et al. 1993; Brumovsky et al. 2006, 2012; Li et al. 2011; Lou et al. 2013). (2) Dopamine and its metabolites dihydroxyphenylacetic acid (DOPAC) and homovanillic acid (HVA) have been detected in DRG neurons and in dorsal spinal nerve roots (Lackovic & Neff, 1980; Philippe et al. 1993; Weil‐Fugazza et al. 1993; Bertrand & Weil‐Fugazza, 1995). (3) Dopamine receptors are expressed in DRG neurons (Xie et al. 1998; Galbavy et al. 2013). A question, however, remains about why it has been difficult to detect other enzymes necessary for the synthesis of catecholamines, i.e. aromatic acid decarboxylase (AADC) and dopamine β‐hydroxylase (DBH) (Price & Mudge, 1983; Kummer et al. 1990; Vega et al. 1991; Brumovsky et al. 2006), even though in some cases AADC and DBH have been detected in TH‐negative [TH(−)] DRG neurons (Brumovsky et al. 2006). A possible explanation could be that the protein levels of AADC and DBH are too low to be detected by immunocytochemistry in these neurons. Alternatively, TH‐positive DRG neurons may synthesize l‐DOPA, which after release is converted to dopamine by AADC localized in other cell types.

Using Western blotting and immunofluorescence, we recently showed that DRG neurons express D1 and D5 (both in peptidergic and non‐peptidergic DRG neurons), but not D2 dopamine receptors (Galbavy et al. 2013). This is consistent with our pharmacological studies showing that SKF 81297 (an agonist at D1/D5 dopamine receptors), but not quinpirole (an agonist at D2 dopamine receptors) can mimic the inhibitory effect of dopamine on the capsaicin‐activated current, as well as on the TTX‐R sodium current (Galbavy et al. 2013). Using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and DNA sequencing, transcripts for D1–D5 dopamine receptors, including D2 receptors, have been detected in dorsal root ganglia (Xie et al. 1998; Peiser et al. 2005). A possible explanation for this discrepancy could be that, even though the transcript for D2 dopamine receptors is detectable with PCR, the protein level could be too low to be detected by Western blotting and pharmacological analysis. Alternatively, it is possible that once translated into protein, D2 dopamine receptors are rapidly transported from the cell body to the terminals, and thus are missed with our analysis.

D1/D5 dopamine receptors may be linked to different protein kinases, according to cell type or tissue specificity, including PKA (Schiffmann et al. 1995; Cantrell et al. 1997; Maurice et al. 2001), PKC (Young & Yang, 2004; Galbavy et al. 2013), and CaMKII (Chen et al. 2007; Anderson et al. 2008; Xing et al. 2010). Protein phosphorylation plays a major role in the modulation of TRPV1 channels. Several serine and threonine residues have been reported to be phosphorylated by PKC (Tominaga et al. 2001; Numazaki et al. 2002; Bhave et al. 2003; Premkumar et al. 2004), or by PKA (De Petrocellis et al. 2001; Bhave et al. 2002; Rathee et al. 2002; Vlachova et al. 2003; Mohapatra & Nau, 2005; Jeske et al. 2006), or by CaMKII (Jung et al. 2004; Price et al. 2005; Hucho et al. 2012). Phosphorylation by PKC sensitizes TRPV1 channels by increasing the channel open probability (Vellani et al. 2001), while phosphorylation by PKA may reverse the desensitization of TRPV1 channels induced by repeated application of the agonist (Bhave et al. 2002). Activation of PKC or PKA by dopamine would be likely to produce an increase of the capsaicin‐activated current. However, our data show that dopamine or SKF 81297 consistently downregulated the capsaicin‐activated current, arguing against a direct involvement of PKC or PKA. In contrast, the inhibitory effect of SKF 81297 on the capsaicin‐activated current was reduced by ∼50% when the CaMKII activity was blocked, suggesting that D1/D5 receptors may be linked to CaMKII. Phosphorylation/dephosphorylation of TRPV1 channels by CaMKII/calcineurin has been suggested to modulate vanilloid binding to TRPV1 channels (Jung et al. 2004). Thus, an intriguing possibility is that activation of D1/D5 dopamine receptors may modulate the function of TRPV1 channels by modulating vanilloid binding to the channel. Because Ca2+ signalling regulates both CaMKII and calcineurin, different mechanisms have been proposed to explain the fine balance between phosphorylation and dephosphorylation, including different activation kinetics, different sensitivities to Ca2+ and calmodulin, or cross‐talk between these two enzymes‐signalling pathways (Hashimoto et al. 1988; Klee, 1991; Tian & Karin, 1999). Future experiments are required to fully elucidate the interaction between D1/D5 dopamine receptors and the CaMKII–calcineurin pathway.

Our results in Fig. 7 support the conclusion that the inhibitory effect of SKF 81297 on the capsaicin‐activated current is highly dependent on calcium. Removal of Ca2+ from the external solution strongly reduced the inhibitory effect of SKF 81297 on the capsaicin‐activated current, arguing in favour of a major contribution of Ca2+ influx. While our experiments were designed to minimize the contribution of calcium channels, activation of voltage‐dependent calcium channels during action potential firing in nociceptors probably provides the major source of Ca2+ influx under physiological conditions (Carbone & Lux, 1984; Scroggs & Fox, 1991, 1992; Blair & Bean, 2002; Bell et al. 2004; Castiglioni et al. 2006; Gemes et al. 2010), contributing to a subsequent rise in cytoplasmic Ca2+ sufficient to engage downstream targets such as CaMKII. However, because of their high permeability to Ca2+ (), membrane‐delimited TRPV1 channels (Caterina et al. 1997), together with those expressed on the endoplasmic reticulum (Olah et al. 2001; Wong et al. 2014), may contribute, at least in part, to the rise in cytoplasmic Ca2+. Indeed, experiments using thapsigargin indicate that Ca2+ released from internal stores contributes to the effects of SKF 81297.

D5 receptors have been shown to couple to phospholipase C (PLC) through Gαq and induce mobilization of Ca2+ from internal stores (So et al. 2009). In contrast, D1 receptors appear to require the presence of D2 receptors to activate PLC (Lee et al. 2004; Rashid et al. 2007). Because we find that

D2 receptor levels are low in DRG neurons (Galbavy et al. 2013), and quinpirole (D2 agonist) has very little effect on the capsaicin‐activated current (Fig. 4), we infer that D5 receptors, coupled to PLC, may constitute the principal pathway for dopamine modulation of TRPV1 channels. This pathway should stimulate hydrolysis of plasma membrane phosphatidylinositol 4,5‐bisphosphate (PIP2) and phosphatidylinositol 4‐phosphate (PI4P), which are well known to modulate the activity of TRP channels (Rohacs & Nilius, 2007), as well as release Ca2+ from inositol 1,4,5‐trisphosphate (IP3)‐sensitive stores (Berridge, 2009).

The high permeability of TRPV1 channels to Ca2+ () (Caterina et al. 1997) may be of particular significance for the modulation and integration of incoming noxious stimuli. Calcium influx is suggested to play a prominent role in the desensitization of TRPV1 channels upon repeated stimulation with the agonist (Cholewinski et al. 1993; Docherty et al. 1996; Liu & Simon, 1996; Koplas et al. 1997; Jung et al. 2004; Rosenbaum et al. 2004), which predicts a reduced response of nociceptors to repeated noxious stimuli. Our data show that dopamine can not only downregulate fully activated TRPV1 channels (e.g. during the first application of capsaicin, Fig. 1 B), but can also downregulate TRPV1 channels that are partially desensitized during repeated applications of the agonist (Fig. 1 D). This suggests that the downregulation of TRPV1 channels by dopamine may occur through a mechanism different from Ca2+‐induced desensitization. The downregulation of TRPV1 channels by dopamine could provide an additional level of modulation to further reduce the activity of TRPV1 channels and the response of nociceptors to repeated incoming noxious stimuli.

In the retina and the olfactory bulb, spontaneously active dopaminergic neurons provide tonic release of dopamine (Feigenspan et al. 1998; Puopolo et al. 2005), which plays an important function in sensory adaptation. In the retina, dopamine sets the gain of the retinal networks for vision in bright light (Witkovsky, 2004); in the olfactory system, dopamine sets the gain for odour discrimination (Nowycky et al. 1983; Duchamp‐Viret et al. 1997; Hsia et al. 1999; Berkowicz & Trombley, 2000; Davison et al. 2004). The C‐LTMRs are usually silent, but in response to light mechanical force, such as stretch of the skin or deflection of hair follicles, fire action potentials (Li et al. 2011) that may trigger the release of dopamine in the dorsal root ganglia as well as in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord. In the dorsal root ganglia, the cell bodies of DRG neurons are usually encapsulated by a single satellite glial cell, rarely in direct contact, and synaptic inputs are virtually absent (Pannese et al. 1991; Shinder et al. 1999). DRG neurons release various peptides and ATP from their soma (Huang & Neher, 1996; Zhang et al. 2007), and when loaded with dopamine, dopamine release can be evoked by high potassium stimulation and detected by amperometric means (Zhang & Zhou, 2002), suggesting that DRG neurons may carry the necessary release machinery for dopamine. Thus, once released from C‐LTMRs, dopamine could modulate the activity of neighbouring cells by inter‐neuron signalling (Amir & Devor, 1996; Rozanski et al. 2012). Increasing or decreasing levels of dopamine may serve to adjust the sensitivity of nociceptors to incoming noxious stimuli, with increasing levels of dopamine raising the threshold for pain and reduced levels increasing the sensitivity to noxious stimuli.

TRPV1 channels are expressed not only on the cell body and peripheral terminals of nociceptors, but also on central terminals that make synaptic contacts in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord (Holzer, 1991; Winter et al. 1993; Szallasi et al. 1995; Tominaga et al. 1998; Guo et al. 1999; Hwang et al. 2004). Activation of presynaptic TRPV1 channels on central terminals with endovanilloids or capsaicin has been shown to trigger the release of peptides and modulate glutamatergic transmission (Yang et al. 1998; Tognetto et al. 2001; Nakatsuka et al. 2002; Baccei et al. 2003; Labrakakis & MacDermott, 2003; Tong & MacDermott, 2006; Medvedeva et al. 2008). In the dorsal horn of the spinal cord, dopamine induces antinociceptive actions by decreasing the frequency and amplitude of spontaneous and miniature EPSC in substantia gelatinosa neurons (Taniguchi et al. 2011), depresses dorsal root potentials evoked by stimulation of cutaneous and muscle afferents (Garcia‐Ramirez et al. 2014), and induces inhibition of the responses to noxious stimuli in superficial neurons (Fleetwood‐Walker et al. 1988). Thus, in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord, dopamine may interact with presynaptic TRPV1 channels to modulate synaptic transmission between nociceptors and dorsal horn neurons.

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author contributions

Conception and design of the experiments: M.P., M.R., M.K. Collection, analysis and interpretation of data: S.C., M.P, M.R., M.K. Drafting the article: S.C., M.P, M.R., M.K. All authors have approved the final version of the manuscript and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work. All persons designated as authors qualify for authorship, and all those who qualify for authorship are listed.

Funding

This work was supported by internal funds from the Department of Anesthesiology, Stony Brook Medicine, Stony Brook, NY, to M.P.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Bruce Bean for helpful comments on the manuscript and William Galbavy for technical assistance.

References

- Abramets, II & Samoilovich IM (1991). Analysis of two types of dopaminergic responses of neurons of the spinal ganglia of rats. Neurosci Behav Physiol 21, 435–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahern GP, Brooks IM, Miyares RL & Wang XB (2005). Extracellular cations sensitize and gate capsaicin receptor TRPV1 modulating pain signaling. J Neurosci 25, 5109–5116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahern GP, Wang X & Miyares RL (2006). Polyamines are potent ligands for the capsaicin receptor TRPV1. J Biol Chem 281, 8991–8995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amir R & Devor M (1996). Chemically mediated cross‐excitation in rat dorsal root ganglia. J Neurosci 16, 4733–4741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson SM, Famous KR, Sadri‐Vakili G, Kumaresan V, Schmidt HD, Bass CE, Terwilliger EF, Cha JH & Pierce RC (2008). CaMKII: a biochemical bridge linking accumbens dopamine and glutamate systems in cocaine seeking. Nat Neurosci 11, 344–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baccei ML, Bardoni R & Fitzgerald M (2003). Development of nociceptive synaptic inputs to the neonatal rat dorsal horn: glutamate release by capsaicin and menthol. J Physiol 549, 231–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bangaru ML, Meng J, Kaiser DJ, Yu H, Fischer G, Hogan QH & Hudmon A (2015). Differential expression of CaMKII isoforms and overall kinase activity in rat dorsal root ganglia after injury. Neuroscience 300, 116–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barasi S & Duggal KN (1985). The effect of local and systemic application of dopaminergic agents on tail flick latency in the rat. Eur J Pharmacol 117, 287–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaulieu JM & Gainetdinov RR (2011). The physiology, signaling, and pharmacology of dopamine receptors. Pharmacol Rev 63, 182–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell TJ, Thaler C, Castiglioni AJ, Helton TD & Lipscombe D (2004). Cell‐specific alternative splicing increases calcium channel current density in the pain pathway. Neuron 41, 127–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benarroch EE (2008). Descending monoaminergic pain modulation: bidirectional control and clinical relevance. Neurology 71, 217–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkowicz DA & Trombley PQ (2000). Dopaminergic modulation at the olfactory nerve synapse. Brain Res 855, 90–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge MJ (2009). Inositol trisphosphate and calcium signalling mechanisms. Biochim Biophys Acta 1793, 933–940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand A & Weil‐Fugazza J (1995). Sympathectomy does not modify the levels of dopa or dopamine in the rat dorsal root ganglion. Brain Res 681, 201–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhave G, Hu HJ, Glauner KS, Zhu W, Wang H, Brasier DJ, Oxford GS & Gereau RWt (2003). Protein kinase C phosphorylation sensitizes but does not activate the capsaicin receptor transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV1). Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100, 12480–12485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhave G, Zhu W, Wang H, Brasier DJ, Oxford GS & Gereau RWt (2002). cAMP‐dependent protein kinase regulates desensitization of the capsaicin receptor (VR1) by direct phosphorylation. Neuron 35, 721–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair NT & Bean BP (2002). Roles of tetrodotoxin (TTX)‐sensitive Na+ current, TTX‐resistant Na+ current, and Ca2+ current in the action potentials of nociceptive sensory neurons. J Neurosci 22, 10277–10290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brumovsky P, Villar MJ & Hokfelt T (2006). Tyrosine hydroxylase is expressed in a subpopulation of small dorsal root ganglion neurons in the adult mouse. Exp Neurol 200, 153–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brumovsky PR, La JH, McCarthy CJ, Hokfelt T & Gebhart GF (2012). Dorsal root ganglion neurons innervating pelvic organs in the mouse express tyrosine hydroxylase. Neuroscience 223, 77–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantrell AR, Smith RD, Goldin AL, Scheuer T & Catterall WA (1997). Dopaminergic modulation of sodium current in hippocampal neurons via cAMP‐dependent phosphorylation of specific sites in the sodium channel alpha subunit. J Neurosci 17, 7330–7338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carbone E & Lux HD (1984). A low voltage‐activated, fully inactivating Ca channel in vertebrate sensory neurones. Nature 310, 501–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardenas CG, Del Mar LP & Scroggs RS (1995). Variation in serotonergic inhibition of calcium channel currents in four types of rat sensory neurons differentiated by membrane properties. J Neurophysiol 74, 1870–1879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castiglioni AJ, Raingo J & Lipscombe D (2006). Alternative splicing in the C‐terminus of CaV2.2 controls expression and gating of N‐type calcium channels. J Physiol 576, 119–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caterina MJ & Julius D (2001). The vanilloid receptor: a molecular gateway to the pain pathway. Ann Rev Neurosci 24, 487–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caterina MJ, Leffler A, Malmberg AB, Martin WJ, Trafton J, Petersen‐Zeitz KR, Koltzenburg M, Basbaum AI & Julius D (2000). Impaired nociception and pain sensation in mice lacking the capsaicin receptor. Science 288, 306–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caterina MJ, Schumacher MA, Tominaga M, Rosen TA, Levine JD & Julius D (1997). The capsaicin receptor: a heat‐activated ion channel in the pain pathway. Nature 389, 816–824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanaugh DJ, Chesler AT, Jackson AC, Sigal YM, Yamanaka H, Grant R, O'Donnell D, Nicoll RA, Shah NM, Julius D & Basbaum AI (2011). Trpv1 reporter mice reveal highly restricted brain distribution and functional expression in arteriolar smooth muscle cells. J Neurosci 31, 5067–5077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cesare P & McNaughton P (1996). A novel heat‐activated current in nociceptive neurons and its sensitization by bradykinin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93, 15435–15439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Bohanick JD, Nishihara M, Seamans JK & Yang CR (2007). Dopamine D1/5 receptor‐mediated long‐term potentiation of intrinsic excitability in rat prefrontal cortical neurons: Ca2+‐dependent intracellular signaling. J Neurophysiol 97, 2448–2464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cholewinski A, Burgess GM & Bevan S (1993). The role of calcium in capsaicin‐induced desensitization in rat cultured dorsal root ganglion neurons. Neuroscience 55, 1015–1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobacho N, De la Calle JL, Gonzalez‐Escalada JR & Paino CL (2010). Levodopa analgesia in experimental neuropathic pain. Brain Res Bull 83, 304–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis JB, Gray J, Gunthorpe MJ, Hatcher JP, Davey PT, Overend P, Harries MH, Latcham J, Clapham C, Atkinson K, Hughes SA, Rance K, Grau E, Harper AJ, Pugh PL, Rogers DC, Bingham S, Randall A & Sheardown SA (2000). Vanilloid receptor‐1 is essential for inflammatory thermal hyperalgesia. Nature 405, 183–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davison IG, Boyd JD & Delaney KR (2004). Dopamine inhibits mitral/tufted→ granule cell synapses in the frog olfactory bulb. J Neurosci 24, 8057–8067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Petrocellis L, Harrison S, Bisogno T, Tognetto M, Brandi I, Smith GD, Creminon C, Davis JB, Geppetti P & Di Marzo V (2001). The vanilloid receptor (VR1)‐mediated effects of anandamide are potently enhanced by the cAMP‐dependent protein kinase. J Neurochem 77, 1660–1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhaka A, Uzzell V, Dubin AE, Mathur J, Petrus M, Bandell M & Patapoutian A (2009). TRPV1 is activated by both acidic and basic pH. J Neurosci 29, 153–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dirajlal S, Pauers LE & Stucky CL (2003). Differential response properties of IB4‐positive and ‐negative unmyelinated sensory neurons to protons and capsaicin. J Neurophysiol 89, 513–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Docherty RJ, Yeats JC, Bevan S & Boddeke HW (1996). Inhibition of calcineurin inhibits the desensitization of capsaicin‐evoked currents in cultured dorsal root ganglion neurones from adult rats. Pflugers Archiv 431, 828–837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duchamp‐Viret P, Coronas V, Delaleu JC, Moyse E & Duchamp A (1997). Dopaminergic modulation of mitral cell activity in the frog olfactory bulb: a combined radioligand binding‐electrophysiological study. Neuroscience 79, 203–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feigenspan A, Gustincich S, Bean BP & Raviola E (1998). Spontaneous activity of solitary dopaminergic cells of the retina. J Neurosci 18, 6776–6789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleetwood‐Walker SM, Hope PJ & Mitchell R (1988). Antinociceptive actions of descending dopaminergic tracts on cat and rat dorsal horn somatosensory neurones. J Physiol 399, 335–348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Formenti A, Arrigoni E & Mancia M (1993). Two distinct modulatory effects on calcium channels in adult rat sensory neurons. Biophys J 64, 1029–1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Formenti A, Martina M, Plebani A & Mancia M (1998). Multiple modulatory effects of dopamine on calcium channel kinetics in adult rat sensory neurons. J Physiol 509, 395–409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galbavy W, Safaie E, Rebecchi MJ & Puopolo M (2013). Inhibition of tetrodotoxin‐resistant sodium current in dorsal root ganglia neurons mediated by D1/D5 dopamine receptors. Mol Pain 9, 60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher JP, Inokuchi H & Shinnick‐Gallagher P (1980). Dopamine depolarisation of mammalian primary afferent neurones. Nature 283, 770–772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao X, Zhang Y & Wu G (2001). Effects of dopaminergic agents on carrageenan hyperalgesia after intrathecal administration to rats. Eur J Pharmacol 418, 73–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia‐Ramirez DL, Calvo JR, Hochman S & Quevedo JN (2014). Serotonin, dopamine and noradrenaline adjust actions of myelinated afferents via modulation of presynaptic inhibition in the mouse spinal cord. PloS One 9, e89999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gemes G, Rigaud M, Koopmeiners AS, Poroli MJ, Zoga V & Hogan QH (2010). Calcium signaling in intact dorsal root ganglia: new observations and the effect of injury. Anesthesiology 113, 134–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo A, Vulchanova L, Wang J, Li X & Elde R (1999). Immunocytochemical localization of the vanilloid receptor 1 (VR1): relationship to neuropeptides, the P2×3 purinoceptor and IB4 binding sites. Eur J Neurosci 11, 946–958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto Y, King MM & Soderling TR (1988). Regulatory interactions of calmodulin‐binding proteins: phosphorylation of calcineurin by autophosphorylated Ca2+/calmodulin‐dependent protein kinase II. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 85, 7001–7005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho C & O'Leary ME (2011). Single‐cell analysis of sodium channel expression in dorsal root ganglion neurons. Mol Cell Neurosci 46, 159–166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holstege JC, Van Dijken H, Buijs RM, Goedknegt H, Gosens T & Bongers CM (1996). Distribution of dopamine immunoreactivity in the rat, cat and monkey spinal cord. J Comp Neurol 376, 631–652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holzer P (1991). Capsaicin: cellular targets, mechanisms of action, and selectivity for thin sensory neurons. Pharmacol Rev 43, 143–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsia AY, Vincent JD & Lledo PM (1999). Dopamine depresses synaptic inputs into the olfactory bulb. J Neurophysiol 82, 1082–1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang LY & Neher E (1996). Ca2+‐dependent exocytosis in the somata of dorsal root ganglion neurons. Neuron 17, 135–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hucho T, Suckow V, Joseph EK, Kuhn J, Schmoranzer J, Dina OA, Chen X, Karst M, Bernateck M, Levine JD & Ropers HH (2012). Ca2+/CaMKII switches nociceptor‐sensitizing stimuli into desensitizing stimuli. J Neurochem 123, 589–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang SJ, Burette A, Rustioni A & Valtschanoff JG (2004). Vanilloid receptor VR1‐positive primary afferents are glutamatergic and contact spinal neurons that co‐express neurokinin receptor NK1 and glutamate receptors. J Neurocytol 33, 321–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen TS & Yaksh TL (1984). Effects of an intrathecal dopamine agonist, apomorphine, on thermal and chemical evoked noxious responses in rats. Brain Res 296, 285–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeske NA, Patwardhan AM, Gamper N, Price TJ, Akopian AN & Hargreaves KM (2006). Cannabinoid WIN 55,212‐2 regulates TRPV1 phosphorylation in sensory neurons. J Biol Chem 281, 32879–32890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung J, Shin JS, Lee SY, Hwang SW, Koo J, Cho H & Oh U (2004). Phosphorylation of vanilloid receptor 1 by Ca2+/calmodulin‐dependent kinase II regulates its vanilloid binding. J Biol Chem 279, 7048–7054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JY, Tillu DV, Quinn TL, Mejia GL, Shy A, Asiedu MN, Murad E, Schumann AP, Totsch SK, Sorge RE, Mantyh PW, Dussor G & Price TJ (2015). Spinal dopaminergic projections control the transition to pathological pain plasticity via a D1/D5‐mediated mechanism. J Neurosci 35, 6307–6317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klee CB (1991). Concerted regulation of protein phosphorylation and dephosphorylation by calmodulin. Neurochem Res 16, 1059–1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koblinger K, Fuzesi T, Ejdrygiewicz J, Krajacic A, Bains JS & Whelan PJ (2014). Characterization of A11 neurons projecting to the spinal cord of mice. PloS One 9, e109636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koplas PA, Rosenberg RL & Oxford GS (1997). The role of calcium in the desensitization of capsaicin responses in rat dorsal root ganglion neurons. J Neurosci 17, 3525–3537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kummer W, Gibbins IL, Stefan P & Kapoor V (1990). Catecholamines and catecholamine‐synthesizing enzymes in guinea‐pig sensory ganglia. Cell Tissue Res 261, 595–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labrakakis C & MacDermott AB (2003). Neurokinin receptor 1‐expressing spinal cord neurons in lamina I and III/IV of postnatal rats receive inputs from capsaicin sensitive fibers. Neurosci Lett 352, 121–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lackovic Z & Neff NH (1980). Evidence for the existence of peripheral dopaminergic neurons. Brain Res 193, 289–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SP, So CH, Rashid AJ, Varghese G, Cheng R, Lanca AJ, O'Dowd BF & George SR (2004). Dopamine D1 and D2 receptor co‐activation generates a novel phospholipase C‐mediated calcium signal. J Biol Chem 279, 35671–35678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Rutlin M, Abraira VE, Cassidy C, Kus L, Gong S, Jankowski MP, Luo W, Heintz N, Koerber HR, Woodbury CJ & Ginty DD (2011). The functional organization of cutaneous low‐threshold mechanosensory neurons. Cell 147, 1615–1627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L & Simon SA (1996). Capsaicin‐induced currents with distinct desensitization and Ca2+ dependence in rat trigeminal ganglion cells. J Neurophysiol 75, 1503–1514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lou S, Duan B, Vong L, Lowell BB & Ma Q (2013). Runx1 controls terminal morphology and mechanosensitivity of VGLUT3‐expressing C‐mechanoreceptors. J Neurosci 33, 870–882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchetti C, Carbone E & Lux HD (1986). Effects of dopamine and noradrenaline on Ca channels of cultured sensory and sympathetic neurons of chick. Pflugers Archiv 406, 104–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurice N, Tkatch T, Meisler M, Sprunger LK & Surmeier DJ (2001). D1/D5 dopamine receptor activation differentially modulates rapidly inactivating and persistent sodium currents in prefrontal cortex pyramidal neurons. J Neurosci 21, 2268–2277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medvedeva YV, Kim MS & Usachev YM (2008). Mechanisms of prolonged presynaptic Ca2+ signaling and glutamate release induced by TRPV1 activation in rat sensory neurons. J Neurosci 28, 5295–5311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohapatra DP & Nau C (2005). Regulation of Ca2+‐dependent desensitization in the vanilloid receptor TRPV1 by calcineurin and cAMP‐dependent protein kinase. J Biol Chem 280, 13424–13432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molokanova EA & Tamarova ZA (1995). The effects of dopamine and serotonin on rat dorsal root ganglion neurons: an intracellular study. Neuroscience 65, 859–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagy JI & Hunt SP (1982). Fluoride‐resistant acid phosphatase‐containing neurones in dorsal root ganglia are separate from those containing substance P or somatostatin. Neuroscience 7, 89–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakatsuka T, Furue H, Yoshimura M & Gu JG (2002). Activation of central terminal vanilloid receptor‐1 receptors and αβ‐methylene‐ATP‐sensitive P2X receptors reveals a converged synaptic activity onto the deep dorsal horn neurons of the spinal cord. J Neurosci 22, 1228–1237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neelands TR, Jarvis MF, Faltynek CR & Surowy CS (2008). Elevated temperatures alter TRPV1 agonist‐evoked excitability of dorsal root ganglion neurons. Inflamm Res 57, 404–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neelands TR, Zhang XF, McDonald H & Puttfarcken P (2010). Differential effects of temperature on acid‐activated currents mediated by TRPV1 and ASIC channels in rat dorsal root ganglion neurons. Brain Res 1329, 55–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowycky MC, Halasz N & Shepherd GM (1983). Evoked field potential analysis of dopaminergic mechanisms in the isolated turtle olfactory bulb. Neuroscience 8, 717–722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Numazaki M, Tominaga T, Toyooka H & Tominaga M (2002). Direct phosphorylation of capsaicin receptor VR1 by protein kinase Cepsilon and identification of two target serine residues. J Biol Chem 277, 13375–13378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olah Z, Szabo T, Karai L, Hough C, Fields RD, Caudle RM, Blumberg PM & Iadarola MJ (2001). Ligand‐induced dynamic membrane changes and cell deletion conferred by vanilloid receptor 1. J Biol Chem 276, 11021–11030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olausson H, Wessberg J, Morrison I, McGlone F & Vallbo A (2010). The neurophysiology of unmyelinated tactile afferents. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 34, 185–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pannese E, Ledda M, Arcidiacono G & Rigamonti L (1991). Clusters of nerve cell bodies enclosed within a common connective tissue envelope in the spinal ganglia of the lizard and rat. Cell Tissue Res 264, 209–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen SF, Owsianik G & Nilius B (2005). TRP channels: an overview. Cell Calcium 38, 233–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peiser C, Trevisani M, Groneberg DA, Dinh QT, Lencer D, Amadesi S, Maggiore B, Harrison S, Geppetti P & Fischer A (2005). Dopamine type 2 receptor expression and function in rodent sensory neurons projecting to the airways. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 289, L153–L158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petruska JC, Napaporn J, Johnson RD, Gu JG & Cooper BY (2000). Subclassified acutely dissociated cells of rat DRG: histochemistry and patterns of capsaicin‐, proton‐, and ATP‐activated currents. J Neurophysiol 84, 2365–2379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philippe E, Zhou C, Audet G, Geffard M & Gaulin F (1993). Expression of dopamine by chick primary sensory neurons and their related targets. Brain Res Bull 30, 227–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Premkumar LS, Qi ZH, Van Buren J & Raisinghani M (2004). Enhancement of potency and efficacy of NADA by PKC‐mediated phosphorylation of vanilloid receptor. J Neurophysiol 91, 1442–1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price J & Mudge AW (1983). A subpopulation of rat dorsal root ganglion neurones is catecholaminergic. Nature 301, 241–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price TJ, Jeske NA, Flores CM & Hargreaves KM (2005). Pharmacological interactions between calcium–calmodulin‐dependent kinase II alpha and TRPV1 receptors in rat trigeminal sensory neurons. Neurosci Lett 389, 94–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puopolo M, Bean BP & Raviola E (2005). Spontaneous activity of isolated dopaminergic periglomerular cells of the main olfactory bulb. J Neurophysiol 94, 3618–3627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puopolo M, Binshtok AM, Yao GL, Oh SB, Woolf CJ & Bean BP (2013). Permeation and block of TRPV1 channels by the cationic lidocaine derivative QX‐314. J Neurophysiol 109, 1704–1712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu S, Ondo WG, Zhang X, Xie WJ, Pan TH & Le WD (2006). Projections of diencephalic dopamine neurons into the spinal cord in mice. Exp Brain Res 168, 152–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rashid AJ, So CH, Kong MM, Furtak T, El‐Ghundi M, Cheng R, O'Dowd BF & George SR (2007). D1–D2 dopamine receptor heterooligomers with unique pharmacology are coupled to rapid activation of Gq/11 in the striatum. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104, 654–659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rathee PK, Distler C, Obreja O, Neuhuber W, Wang GK, Wang SY, Nau C & Kress M (2002). PKA/AKAP/VR‐1 module: A common link of Gs‐mediated signaling to thermal hyperalgesia. J Neurosci 22, 4740–4745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridet JL, Sandillon F, Rajaofetra N, Geffard M & Privat A (1992). Spinal dopaminergic system of the rat: light and electron microscopic study using an antiserum against dopamine, with particular emphasis on synaptic incidence. Brain Res 598, 233–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohacs T & Nilius B (2007). Regulation of transient receptor potential (TRP) channels by phosphoinositides. Pflugers Archiv 455, 157–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum T, Gordon‐Shaag A, Munari M & Gordon SE (2004). Ca2+/calmodulin modulates TRPV1 activation by capsaicin. J Gen Physiol 123, 53–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozanski GM, Kim H, Li Q, Wong FK & Stanley EF (2012). Slow chemical transmission between dorsal root ganglion neuron somata. Eur J Neurosci 36, 3314–3321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiffmann SN, Lledo PM & Vincent JD (1995). Dopamine D1 receptor modulates the voltage‐gated sodium current in rat striatal neurones through a protein kinase A. J Physiol 483, 95–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scroggs RS & Fox AP (1991). Distribution of dihydropyridine and omega‐conotoxin‐sensitive calcium currents in acutely isolated rat and frog sensory neuron somata: diameter‐dependent L channel expression in frog. J Neurosci 11, 1334–1346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scroggs RS & Fox AP (1992). Calcium current variation between acutely isolated adult rat dorsal root ganglion neurons of different size. J Physiol 445, 639–658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seal RP, Wang X, Guan Y, Raja SN, Woodbury CJ, Basbaum AI & Edwards RH (2009). Injury‐induced mechanical hypersensitivity requires C‐low threshold mechanoreceptors. Nature 462, 651–655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinder V, Govrin‐Lippmann R, Cohen S, Belenky M, Ilin P, Fried K, Wilkinson HA & Devor M (1999). Structural basis of sympathetic–sensory coupling in rat and human dorsal root ganglia following peripheral nerve injury. J Neurocytol 28, 743–761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman JD & Kruger L (1990). Selective neuronal glycoconjugate expression in sensory and autonomic ganglia: relation of lectin reactivity to peptide and enzyme markers. J Neurocytol 19, 789–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skagerberg G, Bjorklund A, Lindvall O & Schmidt RH (1982). Origin and termination of the diencephalo‐spinal dopamine system in the rat. Brain Res Bull 9, 237–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- So CH, Verma V, Alijaniaram M, Cheng R, Rashid AJ, O'Dowd BF & George SR (2009). Calcium signaling by dopamine D5 receptor and D5–D2 receptor hetero‐oligomers occurs by a mechanism distinct from that for dopamine D1–D2 receptor hetero‐oligomers. Mol Pharmacol 75, 843–854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stucky CL & Lewin GR (1999). Isolectin B4‐positive and ‐negative nociceptors are functionally distinct. J Neurosci 19, 6497–6505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szallasi A, Nilsson S, Farkas‐Szallasi T, Blumberg PM, Hokfelt T & Lundberg JM (1995). Vanilloid (capsaicin) receptors in the rat: distribution in the brain, regional differences in the spinal cord, axonal transport to the periphery, and depletion by systemic vanilloid treatment. Brain Res 703, 175–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamae A, Nakatsuka T, Koga K, Kato G, Furue H, Katafuchi T & Yoshimura M (2005). Direct inhibition of substantia gelatinosa neurones in the rat spinal cord by activation of dopamine D2‐like receptors. J Physiol 568, 243–253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taniguchi W, Nakatsuka T, Miyazaki N, Yamada H, Takeda D, Fujita T, Kumamoto E & Yoshida M (2011). In vivo patch‐clamp analysis of dopaminergic antinociceptive actions on substantia gelatinosa neurons in the spinal cord. Pain 152, 95–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian J & Karin M (1999). Stimulation of Elk1 transcriptional activity by mitogen‐activated protein kinases is negatively regulated by protein phosphatase 2B (calcineurin). J Biol Chem 274, 15173–15180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tognetto M, Amadesi S, Harrison S, Creminon C, Trevisani M, Carreras M, Matera M, Geppetti P & Bianchi A (2001). Anandamide excites central terminals of dorsal root ganglion neurons via vanilloid receptor‐1 activation. J Neurosci 21, 1104–1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tominaga M, Caterina MJ, Malmberg AB, Rosen TA, Gilbert H, Skinner K, Raumann BE, Basbaum AI & Julius D (1998). The cloned capsaicin receptor integrates multiple pain‐producing stimuli. Neuron 21, 531–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tominaga M, Wada M & Masu M (2001). Potentiation of capsaicin receptor activity by metabotropic ATP receptors as a possible mechanism for ATP‐evoked pain and hyperalgesia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98, 6951–6956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong CK & MacDermott AB (2006). Both Ca2+‐permeable and ‐impermeable AMPA receptors contribute to primary synaptic drive onto rat dorsal horn neurons. J Physiol 575, 133–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vega JA, Amenta F, Hernandez LC & del Valle ME (1991). Presence of catecholamine‐related enzymes in a subpopulation of primary sensory neurons in dorsal root ganglia of the rat. Cell Mol Biol 37, 519–530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vellani V, Mapplebeck S, Moriondo A, Davis JB & McNaughton PA (2001). Protein kinase C activation potentiates gating of the vanilloid receptor VR1 by capsaicin, protons, heat and anandamide. J Physiol 534, 813–825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlachova V, Teisinger J, Susankova K, Lyfenko A, Ettrich R & Vyklicky L (2003). Functional role of C‐terminal cytoplasmic tail of rat vanilloid receptor 1. J Neurosci 23, 1340–1350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voets T, Droogmans G, Wissenbach U, Janssens A, Flockerzi V & Nilius B (2004). The principle of temperature‐dependent gating in cold‐ and heat‐sensitive TRP channels. Nature 430, 748–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei H, Viisanen H & Pertovaara A (2009). Descending modulation of neuropathic hypersensitivity by dopamine D2 receptors in or adjacent to the hypothalamic A11 cell group. Pharmacol Res 59, 355–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weil‐Fugazza J, Onteniente B, Audet G & Philippe E (1993). Dopamine as trace amine in the dorsal root ganglia. Neurochem Res 18, 965–969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter J, Walpole CS, Bevan S & James IF (1993). Characterization of resiniferatoxin binding sites on sensory neurons: co‐regulation of resiniferatoxin binding and capsaicin sensitivity in adult rat dorsal root ganglia. Neuroscience 57, 747–757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witkovsky P (2004). Dopamine and retinal function. Doc Ophthalmol 108, 17–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong CO, Chen K, Lin YQ, Chao Y, Duraine L, Lu Z, Yoon WH, Sullivan JM, Broadhead GT, Sumner CJ, Lloyd TE, Macleod GT, Bellen HJ & Venkatachalam K (2014). A TRPV channel in Drosophila motor neurons regulates presynaptic resting Ca2+ levels, synapse growth, and synaptic transmission. Neuron 84, 764–777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie GX, Jones K, Peroutka SJ & Palmer PP (1998). Detection of mRNAs and alternatively spliced transcripts of dopamine receptors in rat peripheral sensory and sympathetic ganglia. Brain Res 785, 129–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xing B, Kong H, Meng X, Wei SG, Xu M & Li SB (2010). Dopamine D1 but not D3 receptor is critical for spatial learning and related signaling in the hippocampus. Neuroscience 169, 1511–1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]