Abstract

Background: The current chemotherapeutic outcomes for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) are not encouraging, and long-term survival of this patient group remains poor. Recent studies have demonstrated the utility of histone deacetylase inhibitors that can disrupt cell proliferation and survival in HCC management. However, the effects of droxinostat, a type of histone deacetylase inhibitor, on HCC remain to be established. Methods: The effects of droxinostat on HCC cell lines SMMC-7721 and HepG2 were investigated. Histone acetylation and apoptosis-modulating proteins were assessed via Western blot. Proliferation was examined with 3-(4, 5 dimetyl-2-thiazolyl)-2, 5-diphenyl 2H-tetrazolium bromide, cell proliferation, and real-time cell viability assays, and apoptosis with flow cytometry. Results: Droxinostat inhibited proliferation and colony formation of the HCC cell lines examined. Hepatoma cell death was induced through activation of the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway and downregulation of FLIP expression. Droxinostat suppressed histone deacetylase (HDAC) 3 expression and promoted acetylation of histones H3 and H4. Knockdown of HDAC3 induced hepatoma cell apoptosis and histone H3 and H4 acetylation. Conclusions: Droxinostat suppresses HDAC3 expression and induces histone acetylation and HCC cell death through activation of the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway and downregulation of FLIP, supporting its potential application in the treatment of HCC.

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the fifth most common malignancy and constitutes a third of cancer-related mortalities worldwide [1]. Records have shown almost 522,000 new HCC cases in men, 226,000 in women, and an estimated 696,000 deaths in 2008 [2]. Although surgical treatment and liver transplantation are considered two major therapeutic options, these procedures are only viable for about 20% of HCC cases. Surgical treatment is not feasible in 80% patients because of diagnosis at advanced stages [3]. Intraarterial (IA) therapy, including transarterial chemoembolization, is the validated treatment for unresectable HCC, and combining IA with systemic targeted therapies may provide a more efficient strategy in the future [4]. In addition to surgery and IA, chemotherapy is another form of systemic treatment often used at advanced stages of HCC [5]. To date, the outcomes of chemotherapy for HCC have not been encouraging, and long-term survival of HCC patients remains poor [4], [5]. Therefore, the development of novel effective treatment strategies for HCC is an urgent medical necessity.

Histone acetylation status is a result of the balance between the activities of histone deacetylases (HDACs) and histone acetyl transferases (HATs) under normal conditions. Overexpression of HDACs and downregulation of HATs can disrupt this balance, and subsequent abnormalities in chromatin structure and gene transcription lead to tumors, including HCC formation and progression [6]. Kim et al. [7] reported that sustained suppression of HDAC2 attenuates colony formation in the Hep3B cell line in vitro and tumor growth in a mouse xenograft model in vivo. The group of Zheng demonstrated that HDAC3 plays a crucial role in regulating HCC cell proliferation and invasion, suggesting its utility as a candidate biomarker for predicting the prognosis of HCC following liver transplantation [8]. Investigation of the association between HDAC aberrations and HCC led to the hypothesis that HDACs play important roles in regulation of the expression of signaling molecules, constituting novel targets for anticancer drug development. Histone deacetylase inhibitors (HDACIs) interfere with cell proliferation and survival and are therefore feasible for treatment of HCC. Tesoriere et al. [9] reported suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (SAHA)-sensitive human HCC cells at subtoxic doses to Tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-Related Apoptosis-Inducing Ligand (TRAIL)-induced apoptosis, compared with primary human hepatocytes. Experiments by Wang et al. [10] showed that sodium butyrate inhibits HCC migration and invasion by inhibiting HDAC4 and matrix metalloproteinase 7 expression.

Droxinostat (4-(4-chloro-2-methylphenoxy)-N-hydroxybutanamide), an HDACI, was initially identified by Schimmer et al. [11]. The group demonstrated that droxinostat sensitizes PPC-1 cells to FAS and TRAIL via downregulating the expression of c-Fas–associated death domain-like interleukin-1–converting enzyme-like inhibitory protein (c-FLIP) to induce apoptosis [12]. Another study by this group demonstrated that droxinostat sensitizes other cancer cell lines, including PC-3, T47D, DU-145, and OVCAR-3, to anoikis or CH-11–induced apoptosis [11]. Subsequently, these researchers reported that droxinostat selectively suppresses HDAC3, 6, and 8 and promotes histone acetylation [13]. Although droxinostat has been identified as a selective HDACI, its effects on HCC are yet to be established.

In this study, we investigated the effects of droxinostat on human HCC cell lines HepG2 and SMMC-7721 and its underlying mechanisms of action. In particular, the effects of the drug on cell proliferation, apoptosis, and expression of genes or proteins associated with apoptosis pathways were examined. Our results clearly support the potential application of droxinostat as an effective chemotherapeutic agent for HCC.

Materials and Methods

Drugs and Cell Culture

Droxinostat (catalog no: S1422 USA) was purchased from Selleck Chemicals, USA. Human liver carcinoma cell lines (SMMC-7721 and HepG2) were obtained from the State Key Laboratory of Diagnostic and Treatment of Infectious Diseases, First Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University. Cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (Gibco, Grand Island, NY) supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (Gibco), and incubated at 37°C in a humidified incubator containing 5% CO2.

Real-Time Cell Viability Analysis

The xCELLLigence RTCA RT-CES SP system (Real-time Cell-based Electronic Sensor) (Biosciences, San Diego, CA) was used for real-time and time-dependent analysis of the cell index (CI) of SMMC-7721 and HepG2 cells treated with different concentrations of droxinostat. Each well in the 96X E-Plate (Biosciences) was filled with 150 μl of medium. The plate was placed into the xCELLLigence Station and linked to the RECA HT Analyzer. Before replacing the 96X E-Plate, cells were allowed to sediment homogeneously for 30 minutes. HepG2 cells were seeded in 96-well plates at an initial density of 3 × 103 cells/well, and SMMC-7721 cells were seeded at an initial density of 4 × 103 cells/well. After ~ 24 hours, cells were washed with PBS and incubated in complete growth medium with different concentrations (0, 10, 20, 40, and 80 μM) of droxinostat. The control group was treated with 0.9% sodium chloride. The impedance signal was expressed as CI, indicating attachment and adherence of cells to the electrode of the plate, and measured continuously for 96 hours.

Cell Proliferation Assay

HepG2 cells were seeded in 96-well plates at an initial density of 3 × 103 cells/well, and SMMC-7721 cells were seeded at an initial density of 4 × 103 cells/well. After overnight growth, cells were treated with different concentrations of droxinostat (0, 10, 20, 40, and 80 μM) for 0, 24, 48, 72, 96, and 120 hours. Serum-free Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium was used as the blank control, and the same density of cells as the negative control group. After treatment, 20 μl of 5 mg/ml of 3-(4, 5 dimetyl-2-thiazolyl)-2, 5-diphenyl 2H-tetrazolium bromide (MTT) was added to each well. Plates were incubated for a further 4 hours at 37°C, and 150 μl of DMSO (Sigma, USA) was added to each well after removing the supernatant. After incubation for another 10 minutes, cell viability was assessed via measuring absorbance at 490 nm with iMark Reader (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Cell viability is indirectly represented by absorbance values.

Colony Formation Assay

HepG2 and SMMC-7721 cells were seeded into 10-cm dishes at a very low density of 1000 cells/dish and incubated overnight. Cells were treated with 20 μM droxinostat or vehicle (DMSO) for 48 hours, subsequently replaced with fresh complete medium containing drug, and incubated for an additional 15 days in a humidified incubator at 37°C with 5% CO2. Cell colonies were fixed with methanol, stained with crystal violet, washed several times, and air-dried. Blue colonies were counted to indirectly estimate cell survival.

Flow Cytometric Analysis of Apoptosis

Cells were grown in 6-well plates (HepG2 cells: 2 × 105 cell/well, SMMC-7721 cells: 4 × 105cell/well) after 24 hours of incubation with 0.01% DMSO or 0 to 80 μM droxinostat, and further incubated for 48 hours. Cells were harvested, rinsed with PBS, resuspended with 100 μl of Annexin V binding buffer, and stained with 5 μl of Annexin V-FITC and 5 μl propidium idoide (PI) for 15 minutes in the dark. After the addition of 400 μl of AnnexinV binding buffer, cells were analyzed via flow cytometry (BD Bioscience, USA). Analysis was performed on FACSCalibur using CELL Quest software. Annexin V(+)/PI(−) stained cells represent early apoptotic cells, wheras Annexin V(+)/PI(+) staining indicates late apoptotic cells.

Quantitative Real-Time Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction (q RT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted from control and from 20-μM and 40-μM droxinostat–treated HCC cell lines using RNAiso Plus (TaKaRa, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA was measured based on absorbance values at 260 and 280 nm to determine concentration and purity for further use. cDNA synthesis was carried out with a specific kit (TaKaRa, Japan) using 1 μg of total RNA, in keeping with the manufacturer’s instructions.

For real-time PCR analysis, 10 μl of cDNA template was amplified using Power SYBR Green (ABI, USA) in an ABI 7900 HT Fast Real-Time PCR System with the primers specified in Table 1. All reactions were performed at least three times. For each amplification reaction, we assessed the linear range of the standard curve obtained from serial dilutions. Results were quantitatively calculated with the 2− ΔΔCt method. Relative quantification of target gene expression was performed after normalization with the endogenous β-actin control.

Table 1.

List of Primers Used for q RT-PCR

| Gene | Generic Primers |

|---|---|

| p53 | F 5′-CCTCAGCATCTTATCCGAGTG-3′ |

| R 5′-TCATAGGGCACCACCACAC-3′ | |

| Bcl-2 | F 5′-ATGTGTGTGGAGAGCGTCAA-3′ |

| R 5′-GAGACAGCCAGGAGAAATCAA-3′ | |

| Bax | F 5′-GGGTTGTCGCCCTTTTCTAC-3′ |

| R 5′-TGAGGAGGCTTGAGGAGTCT-3′ | |

| β-actin | F 5′-GTGGCCGAGGACTTTGATTG-3′ |

| R 5′-AGTGGGGTGGCTTTTAGGATG-3′ |

Abbreviations: F, forward primer; R, reverse primer.

Western Blotting

Cells were grown to 70% confluency and treated with 0, 10, 20, or 40 μM droxinostat for 48 hours before harvest. Medium and cells were collected via centrifugation at 800g for 5 minutes and washed with cold PBS. Total protein extraction was carried out with RIPA buffer (Beyotime, Jiangsu, China) and nuclear protein extraction with NE-PER Nuclear and cytoplasmic extraction reagents (Thermo, USA) with 100 mM PMSF, 10% PhosStop, and complete ULTRA mini tablets (Maibio, China) for 15 minutes on ice. Cell extracts were collected and centrifuged at 14,000g for 20 minutes at 4°C. Supernatant fractions were collected, and protein concentrations were determined using the Pierce BCA Protein assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc, Rockford, IL). Proteins were used immediately or stored at − 80°C. Protein samples were mixed with 6 × loading buffer (5:1) (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and heated in a PCR instrument at 95°C for 10 minutes. Equivalent amounts of protein (30 μg) were separated using SDS-PAGE and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore, Billerica, MA) at 300 mA in an ice bath for 45 minutes to 2 hours. Protein bands were determined using Precision Plus protein standards (Bio-Rad, USA). Membranes were blocked in TBST containing 1% BSA for 2 hours at room temperature and incubated with primary antibodies including polyclonal anti-P53 et al. (shown in Table 2) at 4°C overnight on a shaking bed, respectively. Membranes were washed three times with 1 × TBST and incubated with secondary HRP-conjugated anti-mouse or anti-rabbit IgG (Dawen Bioscience, China) for 1 hour at room temperature. After washing three times, blots were visualized and detected with ECL (Minipore, Germany) following exposure to X-ray film in the dark room.

Table 2.

Antibody Information

| Antibody | Company | Dilution |

|---|---|---|

| P53 | Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA | 1:2000 |

| Phospho-p53 | Cell Signaling | 1:2000 |

| Bcl-2 | Life Technologies | 1:3000 |

| Bax | Life Technologies | 1:3000 |

| Caspase 3 | Cell Signaling | 1:1000 |

| Cleaved caspase 3 | Cell Signaling | 1:1000 |

| Cleaved PARP | Cell Signaling | 1:2000 |

| FLIP | Cell Signaling | 1:1000 |

| Caspase 8 | Cell Signaling | 1:1000 |

| HDAC3 | Cell Signaling | 1:1000 |

| Histone H3 | Cell Signaling | 1:10,000 |

| Ac-Histone H3 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA | 1:10,000 |

| Ac-Histone H4 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | 1:10,000 |

| β-actin | Dawen Biotech, Hang Zhou, China | 1:2500 |

RNA Interference

Small interfering RNA for HDAC3 (si-HDAC3) (catalog no: sc35538) and nonspecific siRNA (si-Control) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). HepG2 and SMMC-7721 cells were seeded at concentrations of 2 × 105/well in 6-well plates and grown overnight. Cells in each well were transfected with 100 nM siRNA using Lipofectamine RNAi MAX Reagent (Invitrogen, CA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. After 48 hours of transfection, cells were employed for gene knockdown, flow cytometric analysis of apoptosis, and Western blot.

Statistical Analysis

Results are expressed as mean ± standard error (SE) from at least three independent experiments. Differences between groups were examined for statistical significance using one-way analysis of variance. All P values are two-sided, and values < .05 were considered statistically significant (denoted *).

Results

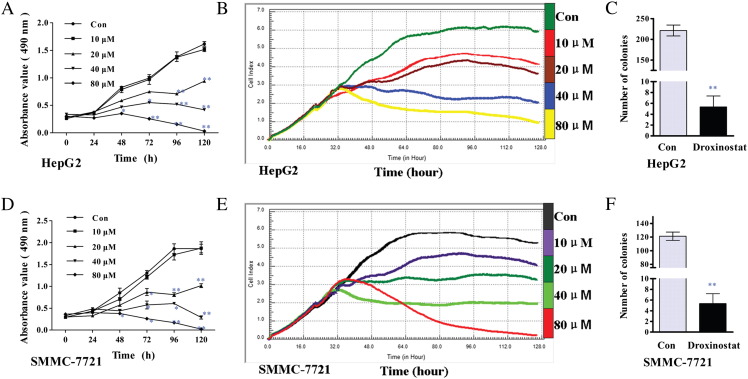

Droxinostat Inhibits Cell Proliferation of HCC Cell Lines

To determine the effects of droxinostat on HCC cell proliferation, two human hepatoma cell lines (HepG2 and SMMC-7721) were analyzed using the MTT assay and the RTCA RT-CES SP system. We observed a time- and dose-dependent decrease in viability in both cell lines cultured in the presence of micromolar concentrations of droxinostat for 120 hours in the MTT assay and 96 hours in the RT-CES SP system (Figure 1, A, B, D, and E). A concentration of 10 μM droxinostat had no effect on the 2 cell lines in the MTT assay (Figure 1, A and D), whereas these cell lines displayed sensitivity to the agent of 10 μM with the RT-CES SP system (Figure 1, B and E). Accordingly, the drug concentration used for inhibiting colony formation was selected as 20 μM. The numbers of colonies formed in the drug-treated groups, compared with their control counterparts, are depicted in Figure 1, C and F.

Figure 1.

Droxinostat inhibits cell proliferation and colony formation in HepG2 and SMMC-7721 cells. (A, D) MTT assay illustrating cell proliferation (0 to 120 hours) following treatment with various concentrations of droxinostat in HepG2 (A) and SMMC-7721 (D) cells. Data are expressed as absorbance values (490 nm), compared with untreated control cells. (B, E) The Real-time cell viability analysis ( RTCA RT-CES SP) system, another cell proliferation method, shown the following 96-hour treatment with various concentrations of droxinostat added at 24 hours in HepG2 (b) and SMMC-7721 (E) cells. Data are expressed as CI, compared with untreated control cells. (C, F) Number of colonies in HepG2 (C) and SMMC-7721 (F) cells after treatment with 20 μM droxinostat at 15 days. Results are expressed as number of colonies, compared with the control group (mean ± SE) (*P < .05, **P < .01).

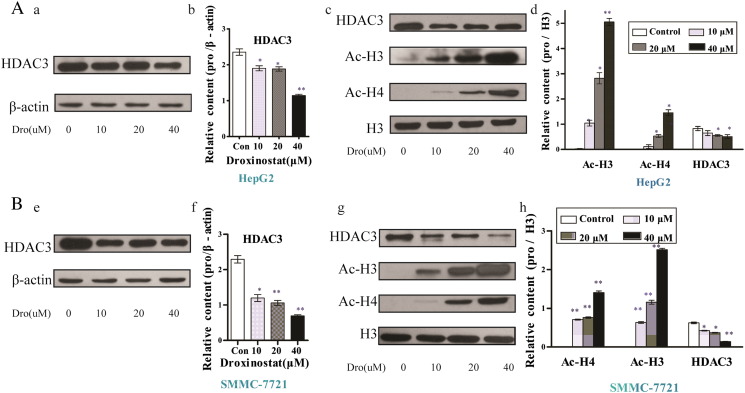

Droxinostat Suppresses HDAC3 Expression and Induces Acetylation of Histones H3 and H4

Previous studies by Zhou et al. indicate a crucial role of HDAC3 in regulating HCC cell proliferation and invasion [8]. Droxinostat acts as a selective inhibitor of HDACs [13]. To ascertain whether droxinostat suppresses HDAC3 expression in HCC, HepG2 and SMMC-7721 cells were incubated with the drug for 48 hours, and HDAC3 levels were analyzed via Western blot. Significantly lower expression of HDAC3 was evident in both cell lines treated with droxinostat (Figure 2, A–E). Furthermore, our experiments revealed dose-dependent downregulation of HDAC3, compared with the control groups, in HepG2 and SMMC-7721 cell lines (Figure 2, B and F). To determine whether inhibition of HDAC3 induces histone acetylation, lysates obtained from droxinostat-treated cells were examined. Droxinostat significantly enhanced the expression of acetyl-H3 (Ac-H3) and acetyl-H4 (Ac-H4) in HepG2 and SMMC-7721 cells in a dose-dependent manner, as shown in Figure 2, C, G, D, and H.

Figure 2.

Droxinostat suppresses HDAC3 expression and acetylates histones H3 and H4. HepG2 (A) and SMMC-7721(B) cells were cultured with 0, 10, 20, or 40 μM droxinostat for 48 hours. Western blot analysis using antibodies against HDAC3, Ac-H3, and Ac-H4 was performed after 48-hour incubation with droxinostat. Internal reference protein loading was verified via the detection of β-actin. (B, D, F, H) Protein expression, expressed as relative content, was examined using Gray analysis and compared with that in the control group (mean ± SE) (*P < .05, **P < .01).

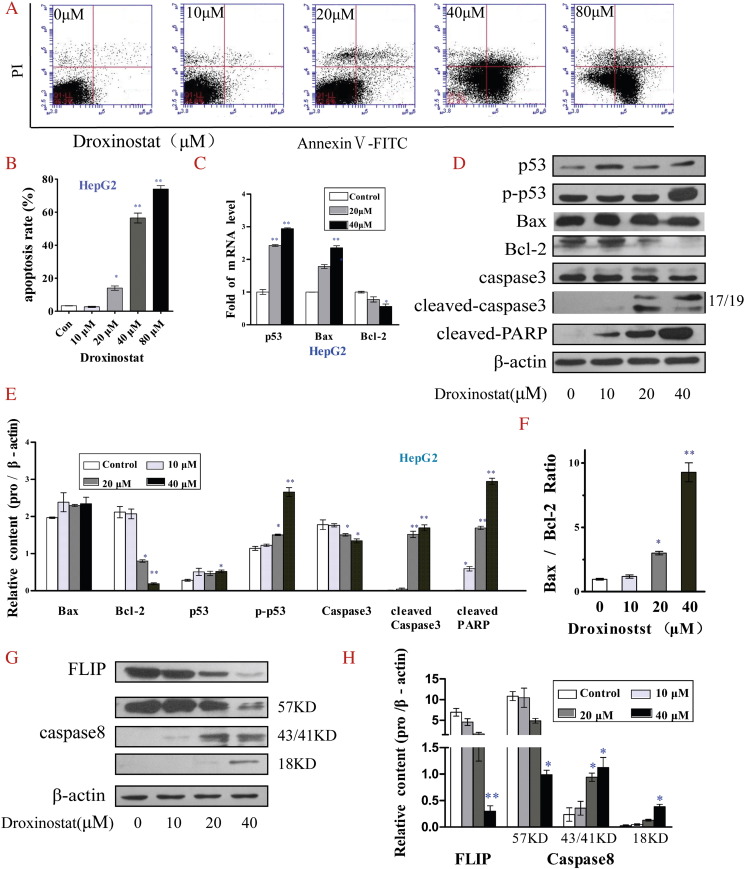

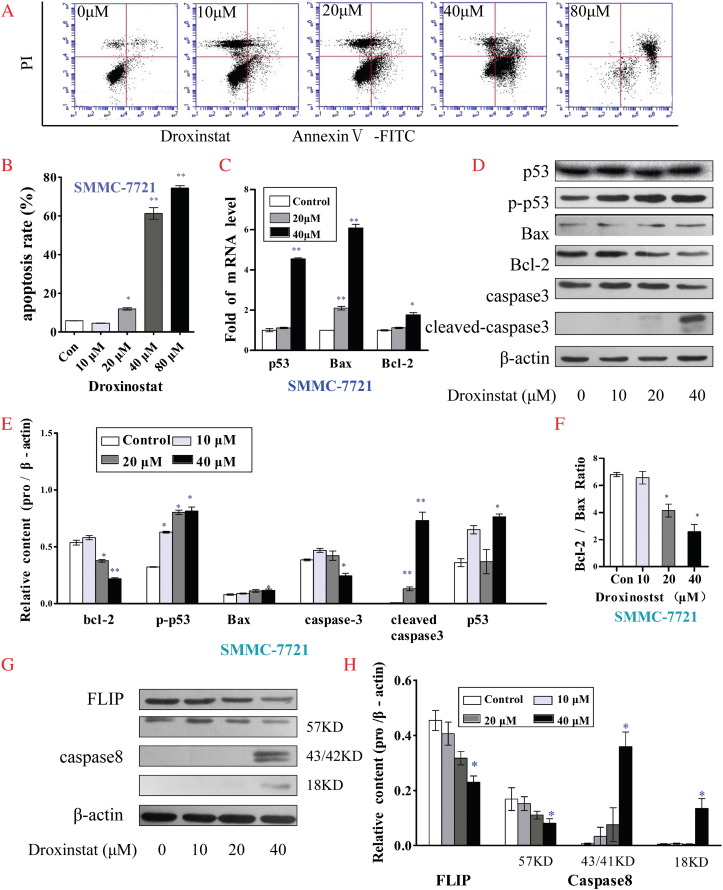

Droxinostat Induces Hepatoma Cell Apoptosis by Activating Mitochondrial Apoptotic Pathways and Downregulating FLIP

We examined the apoptotic status of HepG2 and SMMC-7721 cells incubated with different concentrations of droxinostat after 48 hours via flow cytometry. Droxinostat treatment of HepG2 (Figure 3A) and SMMC-7721 cells (Figure 4A) clearly led to dose-dependent apoptosis. Notably, 10 μM droxinostat did not induce hepatoma cell apoptosis, whereas a starting concentration of 20 μM had an apoptotic effect (Figures 3B and 4B).

Figure 3.

Droxinostat induces HepG2 cell apoptosis by activating the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway and downregulating expression of FLIP. (A) Apoptotic cells were determined via flow cytometry following staining with Annexin V and PI. (B) Apoptosis rates of HepG2 cells treated with different concentrations of droxinostat were analyzed using bar graphs. (C) mRNA levels of genes related to the mitochondrial p53 apoptosis pathway were analyzed using qRT-PCR. (D) Levels of proteins associated with the mitochondrial p53 apoptosis pathway were analyzed via Western blot. (E) The relative contents of proteins of the mitochondrial p53 apoptosis pathway were analyzed using bar graphs. (F) Bax/Bcl-2 protein ratio. (G) Protein levels related to FLIP and caspase-8 were analyzed via Western blot. (H) Relative FLIP and caspase-8 levels were analyzed using bar graphs. Data are shown as means ± SE of three independent experiments, *P < .05, **P < .01, compared with untreated control cells (no droxinostat).

Figure 4.

Droxinostat induces apoptosis in SMMC-7721 cells by activating the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway and downregulating FLIP. (A) Apoptotic cells were determined via flow cytometry following staining with Annexin V and PI. (B) Apoptosis rates of SMMC-7721 cells treated with different concentrations of droxinostat were analyzed using bar graphs. (C) mRNA levels of genes related to the mitochondrial p53 apoptosis pathway were analyzed using qRT- PCR. (D) Levels of proteins associated with the mitochondrial p53 apoptosis pathway were analyzed via Western blot. (E) Relative contents of proteins from the mitochondrial p53 apoptosis pathway were analyzed using bar graphs. (F) Bax /Bcl-2 protein ratio. (G) Protein levels of FLIP and caspase-8 were analyzed via Western blot. (H) Relative contents of FLIP and caspase-8 were analyzed using bar graphs. Data are presented as means ± SE of three independent experiments, *P < .05, **P < .001, compared with untreated control cells (no droxinostat).

To gain insights into the mechanisms underlying droxinostat-mediated HCC cell apoptosis, expression patterns of key proteins related to apoptotic signaling pathways were explored via qRT-PCR and Western blot analyses. As shown in Figures 3C and 4C, mRNA levels of Bax and p53 genes associated with the mitochondrial p53 apoptosis pathway were significantly increased in HepG2 and SMMC-7721 cells treated with droxinostat in a dose-dependent manner. Although Bcl-2 mRNA levels were significantly increased in SMMC-7721 cells at a treatment concentration of 40 μM, the Bax/Bcl-2 mRNA ratio was also increased. Expression levels of proteins related to the mitochondrial p53 apoptosis pathway were additionally analyzed via Western blot (Figures 3D and 4D). Evident upregulation of phospho-p53 and cleaved caspase 3 protein and downregulation of Bcl-2 suggested a role of the mitochondrial p53 pathway in droxinostat-mediated apoptosis (Figures 3E and 4E). Interestingly, although Bax, a critical factor in inducing apoptosis, was not significantly increased, the Bax/Bcl-2 ratio was markedly increased upon treatment in a dose-dependent manner (Figures 3F and 4F). In HepG2 cells, expression of cleaved PARP protein was increased in a dose-dependent manner (Figures 3D and 4E). However, this result was not observed in SMMC-7721 cells.

To further clarify whether FLIP participates in droxinostat-mediated HCC cell apoptosis, we examined changes in FLIP and caspase 8 protein expression via Western blot. Strikingly, both HepG2 (Figure 3G) and SMMC-7721 (Figure 4G) cell groups displayed a significant reduction in FLIP expression and enhanced caspase 8 activity.

Our experiments collectively suggest that the ability of droxinostat to induce hepatoma cell apoptosis is attributable to activation of the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway and reduction of FLIP.

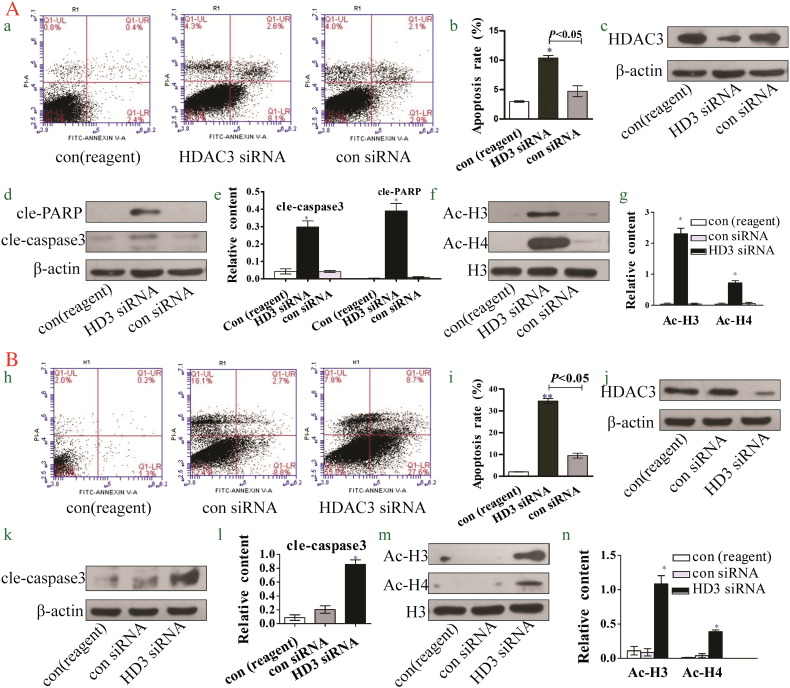

Knockdown of HDAC3 Induces Hepatoma Cell Apoptosis and Acetylation of Histones H3 and H4

Droxinostat has been shown to suppress HDAC3 expression and induce hepatoma cell apoptosis. To determine the potential link between droxinostat-mediated suppression of HDAC3 and its effects on hepatoma cell apoptosis, HDAC3 expression in hepatoma cells was silenced and the effects examined.

As shown in Figure 5C, Western blot analysis revealed a significant decrease in HDAC3 expression in HepG2 cells upon siRNA transfection. Moreover, the apoptotic rate was significantly increased in HDAC3 siRNA than control siRNA and reagent-treated groups (Figure 5, A and B), and expression of cleaved PARP and caspase 3 proteins was upregulated (Figure 5, D and E). Simultaneously, transfection of HepG2 with HDAC3 siRNA induced a significant increase in expression of Ac-H3 and Ac-H4 proteins (Figure 5, G and H).

Figure 5.

Knockdown of HDAC3 induces hepatoma cell apoptosis and acetylation of histones H3 and H4. A: Data obtained with HepG2 cells. (A) Apoptotic populations of HepG2 HDAC3-silenced cells determined via flow cytometry. (B) Analysis of apoptosis rates using bar graphs. (C) HDAC3 protein is downregulated by siRNA against HDAC3 in HepG2 cells. (D, E) Expression of cleaved PARP and cleaved caspase 3 proteins is significantly increased upon knockdown of HDAC3 in HepG2 cells. (F, G) Expression of Ace-H3 and Ace-H4 proteins is significantly increased upon knockdown of HDAC3 in HepG2 cells. B: Data obtained with SMMC-7721 cells. (H) Apoptotic population of SMMC-7721 HDAC3-silenced cells determined via flow cytometry. (I) Analysis of apoptosis rates using bar graphs. (J) HDAC3 is downregulated by siRNA against HDAC3 in SMMC-7721 cells. (H, L) Expression of cleaved caspase 3 is significantly increased upon knockdown of HDAC3 in SMMC-7721 cells. (M, N) Expression of Ace-H3 and Ace-H4 proteins is significantly increased upon knockdown of HDAC3 in SMMC-7721 cells.

In both HepG2 and SMMC-7721 cell lines, silencing of HDAC3 led to a marked increase in cellular apoptosis (Figure 5, H and I), expression of cleaved caspase 3 (Figure 5, K and L), and acetylated histones (Figure 5, M and N).

Discussion

HCC is one of the most common progressive malignancies associated with significant mortality worldwide. Although surgical treatment and liver transplantation are considered two major efficacious therapeutic options for early disease, prognosis for patients with HCC remains very poor owing to frequent diagnosis at advanced stages. Outcomes of chemotherapy for HCC are not encouraging, and long-term survival of these patients is poor [3]. Droxinostat has been reported to sensitize cancer cell lines, including PPC-1, PC-3, T47D, DU-145, and OVCAR-3, to apoptosis [11]. Data from the current study showed that droxinostat inhibits proliferation of the hepatocellular cell lines SMMC-7721 and HepG2 and colony formation in vitro.

Induction of cellular apoptosis is one of the key mechanisms of action of anticancer drugs. In our experiments, droxinostat inhibited HCC growth and induced apoptosis. Droxinosat has been shown to induce apoptosis in prostate cancer and breast cancer cells via downregulating c-FLIP [12]. Here, we showed that induction of apoptosis by droxinostat is mediated through modulation of proteins of the mitochondrial pathway and expression of FLIP in the HCC cell lines HepG2 and SMMC-7721.

HDACIs induce tumor apoptosis via the intrinsic/mitochondrial and death receptor (DR)/extrinsic pathways [14]. The mitochondrion is an important participant in apoptosis following exposure to various death stimuli, including UV- and γ-irradiation, hypoxia, hyperthermia, chemotherapeutic drugs, viral infections, and free radicals [15], [16]. The mitochondrial pathway is regulated by pro- and antiapoptotic Bcl-2 multidomain family members [17]. Antiapoptotic Bcl-2 proteins (Bcl-2, Bcl-XL, Bcl-w) maintain the integrity of the mitochondrial membrane [18]. Proapoptotic Bcl-2 proteins (Bax, Bak, Bim, Bad, Bid, Bik, Bmf) are necessary for the onset of mitochondrial dysfunction and cell death following diverse signals [19]. Once the pro/antiapoptotic balance is disrupted, proapoptotic Bcl-2 proteins activate cytochrome c and second mitochondria derived activator of caspase release from the intermembrane space. Cytochrome c triggers a postmitochondrial pathway, forming an “apoptosome” of cytochrome c, Apaf-1, and caspase-9, in turn activating caspase-9, which subsequently cleaves the downstream effectors caspases-3 and -7 [20].

HDACIs enhance extrinsic apoptosis signaling through diverse mechanisms, including upregulation of TRAIL (it also known as Apo2L, TNFS10) [9], [21], and DR [9], [21], and reduction in the c-FLIP level [21]. The DR/extrinsic apoptosis pathway is activated by binding of TRAIL/Apo2L and TNF-α to TRAIL-R1 (DR-4) or TRAIL-R2 (DR-5) in human cells [14], [9], [21], [22]. Formation of the death-inducing signaling complex ultimately results in initiation of apoptosis via cleavage of caspase-8/10, and activation of downstream caspases-3 and -7 [20]. In addition to activation of the mitochondrial pathway by death stimuli, DRs activate the mitochondrial pathway through caspase 8–mediated cleavage and activation of Bid. In this way, Bid serves as a molecular link between the two pathways [23].

HDACIs have been shown to induce HCC cell apoptosis [24], [25], [26]. Moreover, a number of studies have demonstrated apoptosis induction with a combination of HDACIs and other antitumor drugs [27], [28].

Here, we have shown that droxinostat, an effective inhibitor of HDACs, sensitizes human HCC cell lines (HepG2 and SMMC-7721) to induce apoptosis. Previously, droxinostat was identified as a selective HDACI that can induce anoikis or CH-11–induced apoptosis in cancer cell lines, including PC-3, T47D, DU-145, and OVCAR-3 [12]. The effects of droxinostat on HCC have not been established to date. Our experiments initially demonstrated that droxinostat inhibits hepatoma cell proliferation and induces cell apoptosis. To elucidate the potential mechanisms underlying cell apoptosis, we examined the effects of the compound on expression of mitochondrial pathway proteins and FLIP in HepG2 and SMMC-7721 cell lines. Droxinostat induced dose-dependent significant downregulation of Bcl-2 protein, upregulation of Bax, and enhanced Bax/Bcl-2 ratio. These findings support the activation of an intrinsic apoptotic pathway by droxinostat in the HCC cell lines. Moreover, low doses of droxinostat suppressed the level of FLIP and activated caspase-8. These results suggest that droxinostat sensitizes human hepatocarcinoma cells to the extrinsic apoptosis pathway through downregulating FLIP. Meanwhile, cleaved PARP expression was upregulated in HepG2, but not SMMC-7721 cells, indicating the involvement of other regulation factors that requires further investigation.

Epigenetic aberrations play a critical role in the development and progression of human HCC [29]. Histone modification is one of the most important types of epigenetic changes, and its status is balanced by the activities of HDACs and HATs. Several studies have disclosed an important role of HDAC3 in the development and progression of HCC. Zheng et al. reported that HDAC3 is highly expressed and an unfavorable independent prognostic factor in HCC patients. Inhibition of HDAC3 leads to suppression of proliferation and invasiveness of HCC cells in vitro, supporting its applicability as a candidate biomarker for predicting recurrence of HCC following liver transplantation [8]. Meanwhile, Yang et al. showed that hypoxia improves HDAC3 expression by affecting the level of histone acetylation and nuclear factor-90 expression to promote HCC cell invasion and metastasis [30].

Thus, HDAC3 is overexpressed in HCC tissues and cells. Droxinostat, a specific HDACI, specifically inhibits HDAC3, 6, and 8 expression. Here, we examined the hypothesis that droxinostat mediates suppression of tumor development through inhibition of HDAC3. Our experiments showed that droxinostat inhibits HDAC3 and promotes AceH3 and AceH4 expression. These effects may be related to facilitation of gene transcription through increasing acetylation levels and further relaxation of the chromosome status. Because of acetylation of lysine residues, the positive charge at the N-terminal tail domains of histone is decreased and interactions with DNA are weakened, allowing transcription factors to bind to DNA and initiate transcriptional machinery [31]. To further investigate the relationship between droxinostat-induced HCC cell apoptosis and expression of HDAC3, we disrupted HDAC3 expression in HCC cells. Apoptosis rates and cleaved caspase 3 levels were increased under these conditions, supporting the theory that droxinostat induces HCC cell apoptosis via suppression of HDAC3.

In conclusion, droxinostat induces apoptosis in HepG2 and SMMC-7721 cells through activating the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway and downregulating expression of FLIP. In view of the complex pathways of apoptosis, other extrinsic apoptosis and endoplasmic reticulum–mediated signaling pathways cannot be overlooked and should be investigated in the future. Acetylation of histones plays an essential role in the pathogenesis of HCC and is dependent on the counterbalance between HDAC and HAT activities. Our results showed that droxinostat suppresses HDAC3 expression and induces acetylation of histones H3 and H4. We propose that inhibition of HDAC3 promotes histone acetylation, which may be the molecular mechanism underlying the proapoptotic function of droxinostat in HCC. The antitumor effects of droxinostat require further research in vivo and in vitro to establish its potential as a novel inhibitory agent for HCC.

Conflict of Interest

The authors disclose that there is no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgement

We sincerely thank associate professor Shu-ping Li who provided laboratory platform and expect technical assistance. This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Gansu province (1010RJZA087).

Footnotes

Foundation: This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Gansu province (1010RJZA087).

References

- 1.Bosch FX, Ribes J, Cleries R, Diza M. Epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma [J] Clin Liver Dis. 2005;9(2):191–211. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2004.12.009. [v] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008 [J] Int J Cancer. 2010;127(12):2893–2917. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rahbari NN, Mehrabi A, Mollberg NM, Muller SA, Koch M, Buchler MW, Weitz J. Hepatocellular carcinoma: current management and perspectives for the future [J] Ann Surg. 2011;253(3):453–469. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31820d944f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsochatzis EA, Germani G, Burroughs AK. Transarterial chemoembolization, transarterial chemotherapy, and intra-arterial chemotherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma treatment [J] Semin Oncol. 2010;37(2):89–93. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2010.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Czaja AJ. Current management strategies for hepatocellular carcinoma [J] Minerva Gastroenterol Dietol. 2013;59(2):143–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Orr JA, Hamilton PW. Histone acetylation and chromatin pattern in cancer—a review [J] Anal Quant Cytol Histol. 2007;29(1):17–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Noh JH, Jung KH, Kim JK, Eun JW, Xie HJ, Chang YG, Kim MG, Park WS, Lee JY. Aberrant regulation of HDAC2 mediates proliferation of hepatocellular carcinoma cells by deregulating expression of G1/S cell cycle proteins [J] PLos One. 2011;6(11) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu LM, Yang Z, Zhou L, Zhang F, Xie HY, Feng XW, Wu J, Zheng SS. Identification of histone deacetylase 3 as a biomarker for tumor recurrence following liver transplantation in HBV-associated hepatocellular carcinoma [J] PLos One. 2010;5(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 9.Carlisi D, Lauricella M, D'Anneo A, Emanuele S, Angileri L, Di Fazio P, Santulli A, Vento R, Tesoriere G. The histone deacetylase inhibitor suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid sensitises human hepatocellular carcinoma cells to TRAIL-induced apoptosis by TRAIL-DISC activation [J] Eur J Cancer. 2009;45(13):2425–2438. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2009.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang HG, Huang XD, Shen P, Li LR, Xue HT, Ji GZ. Anticancer effects of sodium butyrate on hepatocellular carcinoma cells in vitro [J] Int J Mol Med. 2013;31(4):967–974. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2013.1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mawji IA, Simpson CD, Hurren R, Gronda M, Williams MA, Filmus J, Da Costa RS, Wilson BC, Thomas MP. Critical role for Fas-associated death domain-like interleukin-1-converting enzyme-like inhibitory protein in anoikis resistance and distant tumor formation [J] J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99(10):811–822. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djk182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schimmer AD, Thomas MP, Hurren R, Gronda M, Pellecchia M, Pond GR, Konopleva M, Gurfinkel D, Mawji IA, Brown E. Identification of small molecules that sensitize resistant tumor cells to tumor necrosis factor-family death receptors [J] Cancer Res. 2006;66(4):2367–2375. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wood TE, Dalili S, Simpson CD, Sukhai MA, Hurren R, Anyiwe K, Mao X, Suarez Saiz F, Gronda M, Eberhard Y. Selective inhibition of histone deacetylases sensitizes malignant cells to death receptor ligands [J] Mol Cancer Ther. 2010;9(1):246–256. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matthews GM, Newbold A, Johnstone RW. Intrinsic and extrinsic apoptotic pathway signaling as determinants of histone deacetylase inhibitor antitumor activity [J] Adv Cancer Res. 2012;116:165–197. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-394387-3.00005-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kroemer G, Dallaporta B, Resche-Rigon M. The mitochondrial death/life regulator in apoptosis and necrosis [J] Annu Rev Physiol. 1998;60:619–642. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.60.1.619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elmore S. Apoptosis: a review of programmed cell death [J] Toxicol Pathol. 2007;35(4):495–516. doi: 10.1080/01926230701320337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cory S, Adams JM. The Bcl2 family: regulators of the cellular life-or-death switch [J] Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2(9):647–656. doi: 10.1038/nrc883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cory S, Huang DC, Adams JM. The Bcl-2 family: roles in cell survival and oncogenesis [J] Oncogene. 2003;22(53):8590–8607. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Adams JM, Cory S. The Bcl-2 protein family: arbiters of cell survival [J] Science. 1998;281(5381):1322–1326. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5381.1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnstone RW, Ruefli AA, Lowe SW. Apoptosis: a link between cancer genetics and chemotherapy [J] Cell. 2002;108(2):153–164. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00625-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schuchmann M, Schulze-Bergkamen H, Fleischer B, Schattenberg JM, Weinmann A, Teufel A, Worns M, Fischer T. Histone deacetylase inhibition by valproic acid down-regulates c-FLIP/CASH and sensitizes hepatoma cells towards CD95- and TRAIL receptor-mediated apoptosis and chemotherapy [J] Oncol Rep. 2006;15(1):227–230. doi: 10.3892/or.15.1.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dzieran J, Beck JF, Sonnemann J. Differential responsiveness of human hepatoma cells versus normal hepatocytes to TRAIL in combination with either histone deacetylase inhibitors or conventional cytostatics [J] Cancer Sci. 2008;99(8):1685–1692. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2008.00868.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li H, Zhu H, Xu CJ, Yuan J. Cleavage of BID by caspase 8 mediates the mitochondrial damage in the Fas pathway of apoptosis [J] Cell. 1998;94(4):491–501. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81590-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang W, Zhao X, Pei F, Ji M, Ma W, Wang Y, Jiang G. Activation of the intrinsic apoptosis pathway contributes to the induction of apoptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma cells by valproic acid [J] Oncol Lett. 2015;9(2):881–886. doi: 10.3892/ol.2014.2739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang YC, Kong WZ, Xing LH, Yang X. Effects and mechanism of suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid on the proliferation and apoptosis of human hepatoma cell line Bel-7402 [J] J BUON. 2014;19(3):698–704. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang YC, Yang X, Xing LH, Kong WZ. Effects of SAHA on proliferation and apoptosis of hepatocellular carcinoma cells and hepatitis B virus replication [J] World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19(31):5159–5164. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i31.5159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yuan H, Li AJ, Ma SL, Cui LJ, Wu B, Yin L, Wu MC. Inhibition of autophagy signi fi cantly enhances combination therapy with sorafenib and HDAC inhibitors for human hepatoma cells [J] World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(17):4953–4962. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i17.4953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hamed HA, Yamaguchi Y, Fisher PB, Grant S, Dent P. Sorafenib and HDAC inhibitors synergize with TRAIL to kill tumor cells [J] J Cell Physiol. 2013;228(10):1996–2005. doi: 10.1002/jcp.24362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pogribny IP, Rusyn I. Role of epigenetic aberrations in the development and progression of human hepatocellular carcinoma [J] Cancer Lett. 2014;342(2):223–230. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2012.01.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang F, Huo XS, Yuan SX, Zhang L, Zhou WP, Wang F, Sun SH. Repression of the long noncoding RNA-LET by histone deacetylase 3 contributes to hypoxia-mediated metastasis [J] Mol Cell. 2013;49(6):1083–1096. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gallinari P, Di Marco S, Jones P, Pallaoro M, Steinkuhler C. HDACs, histone deacetylation and gene transcription: from molecular biology to cancer therapeutics [J] Cell Res. 2007;17(3):195–211. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7310149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]