Abstract

Objectives

To investigate the rate of recording of premenstrual syndrome diagnoses in UK primary care and describe pharmacological treatments initiated following a premenstrual syndrome (PMS) diagnosis.

Design

Retrospective cohort study.

Setting

UK primary care.

Participants

Women registered with a practice contributing to The Health Improvement Network primary care database between 1995 and 2013.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

The primary outcome was the rate of first premenstrual syndrome records per 1000 person years, stratified by calendar year and age. The secondary outcome was the proportions of women with a premenstrual syndrome record prescribed a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, progestogen, oestrogen, combined oral contraceptive, progestin only contraceptive, gonadotrophin-releasing hormone, danazol and vitamin B6.

Results

The rate of recording of premenstrual syndrome diagnoses decreased over calendar time from 8.43 in 1995 to 1.72 in 2013. Of the 38 614 women without treatment in the 6 months prior to diagnosis, 54% received a potentially premenstrual syndrome-related prescription on the day of their first PMS record while 77% received a prescription in the 24 months after. Between 1995 and 1999, the majority of women were prescribed progestogens (23%) or vitamin B6 (20%) on the day of their first PMS record; after 1999, these figures fell to 3% for progestogen and vitamin B6 with the majority of women instead being prescribed a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (28%) or combined oral contraceptive (17%).

Conclusions

Recording of premenstrual syndrome diagnoses in UK primary care has declined substantially over time and preferred prescription treatment has changed from progestogen to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor and combined oral contraceptives.

Keywords: premenstrual, EPIDEMIOLOGY, REPRODUCTIVE MEDICINE

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The UK primary care database used in this study contains data on the routine clinical management of a representative sample of the UK general population.

The longitudinal nature of the database allowed us to report on changes in the recording and treatment of premenstrual syndrome over an 18-year period (1995–2013).

Cases were ascertained using diagnostic codes recorded in general practice rather than through prospective methods, and case certainty is therefore less than 100%.

Since the indication for prescriptions is not recorded in the data source, prescriptions were assumed to be for premenstrual syndrome (PMS) based on their timing with regard to the first PMS diagnosis record.

Background

Premenstrual syndrome (PMS) comprises a range of physical, psychological and behavioural symptoms experienced by many premenopausal women during the luteal phase of their menstrual cycle.1 Common symptoms include anxiety, irritability, depression, mood swings, sleep disorders, fatigue, altered interest in sex, breast tenderness, weight gain, headaches, change in appetite, general aches and pain and feeling bloated.1 Premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD), a severe subtype of PMS, has been defined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) as occurring when a woman suffers from at least five distinct psychological premenstrual symptoms.2

Prevalence estimates of PMS vary depending on the methods used to identify and classify cases. The proportion of women of reproductive age reporting at least one PMS symptom has been reported to range between 50% and 90%, the proportion reporting severe PMS symptoms or symptoms that interfere with daily activities to range between 10% and 30%, and the proportion meeting the strict DSM PMDD criteria of having at least five psychological symptoms to range between 1% and 8%.3

While the proportion of women of reproductive age suffering clinically relevant PMS symptoms appears to be high, the proportion of women who seek medical help has been less well studied. A survey of 300 women in the UK in 1998 classified 31% as having severe PMS symptoms, of whom 53% sought medical help.4 This compares with 45% and 29% of women with severe premenstrual symptoms seeking medical attention in the USA and France in 1998, respectively, while 41% of women with severe PMS in a separate study in Switzerland reported consulting a doctor between 1986 and 1993.5

Evidence-based6–13 guidelines for the management of PMS have been published by the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG)14 and, more recently, by the International Society for Premenstrual Disorders (ISPMD).15 The RCOG guidelines suggest the use of exercise, cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT), vitamin B6, new generation combined oral contraceptives (cyclically or continuously) and/or low dose selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) (used continuously or only during the luteal phase) as first-line treatment and the use of oestradiol patches and/or higher dose SSRIs (also used continuously or only during the luteal phase) as second-line treatment. Gondaotrophin analogues (with add-back hormone replacement therapy) are recommended as third-line treatment, and total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral oophorectomy with hormone replacement therapy as fourth-line treatment. The ISPMD recommends both SSRIs and all of the oestrogen suppressing treatments listed above but does not recommend different treatments and dosing schedules for specific treatment lines. A study investigating treatments prescribed in UK primary care on the day of a PMS record found that between 1993 and 1998 progestogens were the most commonly prescribed treatment and that vitamin B6 prescribing decreased over the period while SSRI prescribing increased.6 However, there is little information on current prescribing practices.

This study seeks to estimate the rate of recording of PMS diagnoses in UK primary care over a 19-year period and establish which pharmacological treatments were most commonly initiated following a PMS diagnosis.

Methods

This study was carried out using The Health Improvement Network (THIN). THIN is an electronic healthcare database containing the anonymised primary care medical records of more than 12 million individuals in the UK general population. Patient data routinely available in the database include demographic details, diagnoses and symptoms (including those leading to hospital admissions), immunisations, pregnancies, laboratory tests, referrals to specialists, prescriptions issued by the general practitioner (GP), hospital discharge and clinic summaries and deaths. Clinical events in primary care are recorded against clinical codes, known as a Read codes.16 17 There are currently over 100 000 Read codes, each of which is associated with a short description of varying specificity. Recording of additional, unstructured textual information in association with a Read code is possible. This information, commonly referred to as ‘free text’, generally contains elaborations on the information in the coded record.

The study population consisted of all women registered with a GP practice contributing to THIN, aged between 12 and 49 years. The follow-up of each woman began at the latest of 1 January 1995, 182 days after their registration date, 12 years of age and the date their practice recording reached acceptable levels.18 19 The follow-up of each woman ended at the earliest of 1 January 2014, 50 years of age, the date the woman transferred out of their practice, the date data were last collected from their practice and the patient's date of death.

Code lists defining PMS diagnoses and prescriptions were developed following the method described by Davé and Petersen and are provided in online supplementary tables S1 and S2.16 Prescriptions were categorised in one of the following categories of interest, based on the British National Formulary: SSRI, progestogen, oestrogen, combined oral contraceptive (COC), progesterone only contraceptive (POC), danazol, gonadotrophin releasing hormone (GnRH) analogues and vitamin B6.

bmjopen-2015-010244supp.pdf (490.2KB, pdf)

All women with PMS diagnostic codes recorded during follow-up were identified and the rate of recording was calculated as the number of first PMS diagnosis codes recorded divided by the total amount of follow-up time at risk. Among individuals with a PMS event, follow-up was censored at the date of the first PMS record. Recording rates were calculated per 1000 person years and are presented stratified by calendar year and age; 95% CIs were calculated assuming a Poisson distribution.

Among those women with a first PMS record meeting the inclusion criteria, the proportion with a first record of one of the PMS-related drugs listed above in the 6 months before their PMS record was calculated, and these women were considered prevalent users. We also estimated the proportion of women by calendar year with a first PMS record meeting the inclusion criteria with a prescription for PMS-related drugs on the day of their PMS record or in the 24 months after the PMS record (but not in the 6 months before the PMS record was made in the notes). We use cumulative incidence plots to describe the proportions of individuals initiating each treatment at the time of, or in the 24 months after, a PMS record as a function of time. The proportion of women receiving prescriptions for different types of SSRI and COC were calculated stratified by calendar year, and for SSRIs the daily dose prescribed was also tabulated.

Stata V.13 was used in the management and analysis of all data.

Results

There were 2 860 143 eligible women contributing 12.6 million person years (PY) of data. Of these, there were 42 754 individuals with a first PMS event recorded providing an overall rate of recording of 3.38 PMS records per 1000 PY (95% CI 3.35 to 3.41).

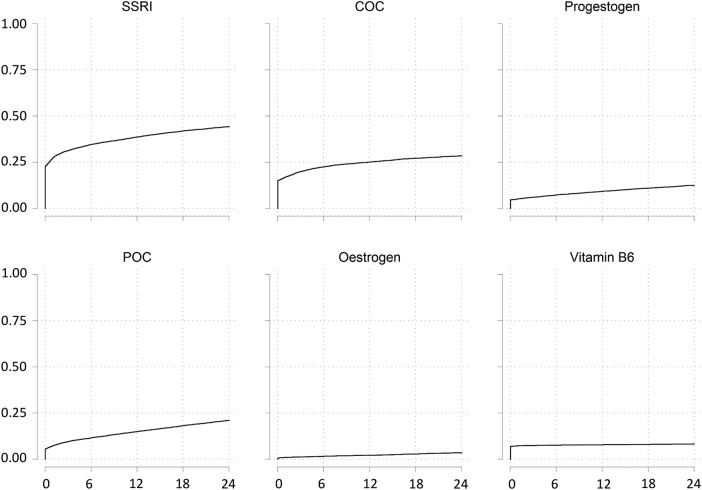

The rate of PMS recording decreased dramatically over time from 8.43/1000 PY (95% CI 8.02 to 8.85) in 1995 to 1.72/1000 PY (95% CI 1.63 to 1.81) in 2013 (figure 1). The decrease was relatively rapid between 1995 and 2000, levelled off between 1999 and 2000 and then began to decrease again after 2000.

Figure 1.

Calendar year specific rates (per 1000 person years) of first PMS records in UK general practice. PMS, premenstrual syndrome.

The rate of recording of PMS diagnoses increased by age from 1.21/1000 PY (95% CI 1.13 to 1.28) in those aged between 11 and 14 years to 5.61/1000 PY (95% CI 5.50 to 5.71) in those aged 35–40 years at which point the rate peaked and began to fall again reaching 2.07/1000 PY (95% CI 2.00 to 2.13) in those aged 45–50 years (table 1).

Table 1.

Age-specific rates (per 1000 person years) of first PMS records in UK general practice

| Age (years) | N | IR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| 12–14 | 1056 | 1.21 | (1.14 to 1.28) |

| 15–19 | 1975 | 1.50 | (1.43 to 1.57) |

| 20–24 | 2475 | 1.80 | (1.73 to 1.87) |

| 25–29 | 5165 | 3.28 | (3.19 to 3.37) |

| 30–34 | 8947 | 5.04 | (4.94 to 5.15) |

| 35–39 | 10 768 | 5.61 | (5.50 to 5.71) |

| 40–44 | 8540 | 4.39 | (4.30 to 4.49) |

| 45–49 | 3808 | 2.07 | (2.00 to 2.13) |

PMS, premenstrual syndrome.

Ten per cent of women received a prescription for one of the drugs of interest in the 6 months before their first PMS record. Prevalent treatment remained relatively stable across the study period for all drug categories other than COCs. The proportion of women with a COC prescription in the 6 months before their PMS record was 9% (141/1567) in 1995 but decreased to between 2% and 5% between 1996 and 2011.

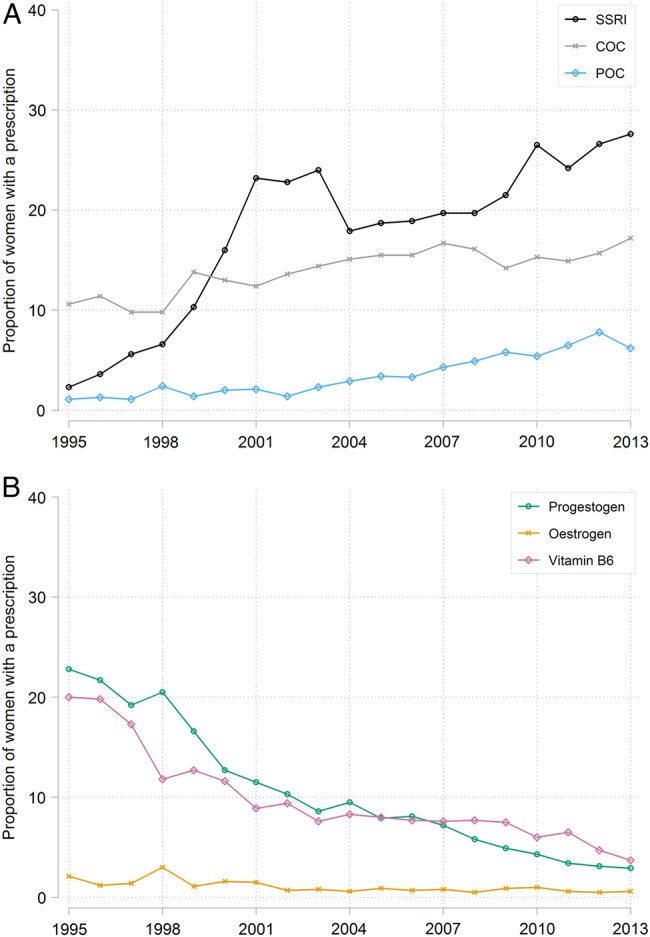

Fifty-four per cent of women (20 996/38 614) without a given prescription in the 6 months before their PMS record had a prescription of interest on the day of diagnosis. While the overall proportion receiving a prescription of interest remained stable over time, the proportions initiating specific drug types changed (figure 2). The proportion of women initiating SSRIs has increased from 2.3% (35/1522) to 27.6% (381/1380), POCs from 1.1% (17/1545) to 6.2% (87/1403) and COCs from 10.6% (151/1425) to 17.2% (239/1390) over the study period (figure 2A). In contrast, the proportion initiating progestogen has declined from 22.8% (350/1535) to 2.9% (41/1414), oestrogen from 2.1% (32/1524) to 0.6% (8/1333) and vitamin B6 from 20.0% (310/1550) to 3.7% (52/1405; figure 2B). Prescribing of GnRH analogues and danazol on the day of a PMS record was too low (<1%) to observe trends over time.

Figure 2.

Calendar year specific proportion of women without a given prescription in the 6 months before their PMS record who had (A) an SSRI, COC or POC prescription or (B) a progestogen, oestrogen or vitamin B6 prescription on the day of their first PMS record. COC, combined oral contraceptive; PMS, premenstrual syndrome; POC, progesterone only contraceptive; SSRIs, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.

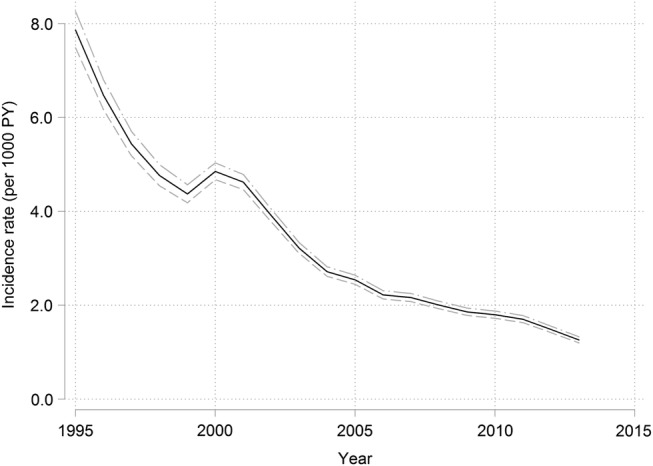

Seventy-seven per cent of women (29 891/38 614) had a prescription of interest on the day of their PMS record or in the 24 months after; this proportion remained stable over time. Figure 3 shows the cumulative proportion of prescriptions in the 24 months following the first PMS record between 2008 and 2011 for each drug type. With the exception of vitamin B6, the proportion of women with a prescription in this time period increased considerably over the 24 months for all drug types such that by 24 months 44% (3648/8365) had received an SSRI prescription, 28% (2363/8434) a COC prescription, 12% (1030/8475) a progestogen prescription, 20% (1727/8463) a POC prescription and 3% (293/8557) an oestrogen prescription.

Figure 3.

Cumulative incidence of prescriptions in the 24 months following a PMS diagnosis record for the period 2008–2011. PMS, premenstrual syndrome.

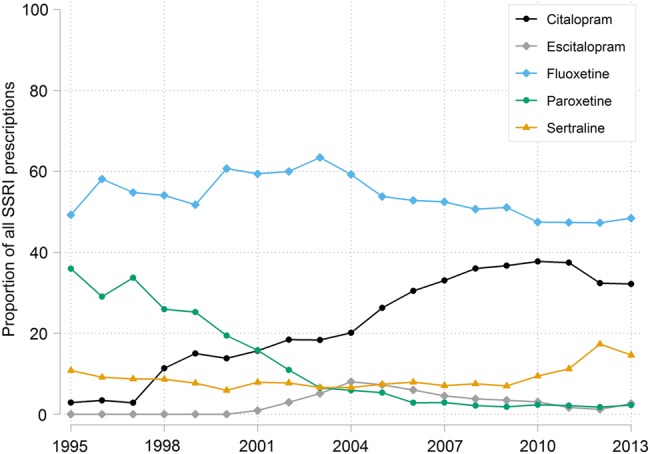

The type of SSRI prescribed on the day of the first PMS record is shown in figure 4 as a proportion of all SSRI prescriptions. Fluoxetine is the most prescribed SSRI throughout the study period, making up more than 50% of SSRI prescriptions. Citalopram and, more recently, sertraline make up an increasing proportion of SSRI prescriptions over time, while paroxetine and escitalopram make up a decreasing proportion. The dose of SSRI prescribed per day is shown in table 2 and is primarily 10 or 20 mg for citalopram, 5, 10 or 20 mg for escitalopram, 10 mg for fluoxetine, 10, 20 or 30 mg for paroxetine and 50 or 100 mg for sertraline.

Figure 4.

Type of SSRI prescribed on the day of the first PMS record over time, as a proportion of all SSRI prescriptions. PMS, premenstrual syndrome; SSRIs, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.

Table 2.

Type and daily dose of SSRI prescribed on the day of a PMS record

| Citalopram |

Escitalopram |

Fluoxetine |

Paroxetine |

Sertraline |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daily dose (mg) | n | Per cent | n | Per cent | n | Per cent | n | Per cent | n | Per cent |

| 5 | 0 | (0) | 27 | (15.7) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) |

| 7.5 | 1 | (0.1) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) |

| 10 | 452 | (30.4) | 80 | (46.5) | 16 | (0.3) | 26 | (4.9) | 0 | (0) |

| 15 | 4 | (0.3) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 1 | (0.2) | 0 | (0) |

| 20 | 501 | (33.7) | 18 | (10.5) | 3880 | (79.5) | 356 | (67.6) | 0 | (0) |

| 25 | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 3 | (0.6) |

| 30 | 3 | (0.2) | 0 | (0) | 3 | (0.1) | 47 | (8.9) | 0 | (0) |

| 40 | 67 | (4.5) | 0 | (0) | 81 | (1.7) | 16 | (3) | 0 | (0) |

| 45 | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 1 | (0.2) | 0 | (0) |

| 50 | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 333 | (62.6) |

| 60 | 1 | (0.1) | 0 | (0) | 15 | (0.3) | 1 | (0.2) | 0 | (0) |

| 75 | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 4 | (0.8) |

| 100 | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 40 | (7.5) |

| 200 | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 5 | (0.9) |

| Unknown | 458 | (30.8) | 47 | (27.3) | 883 | (18.1) | 79 | (15) | 147 | (27.6) |

| Total | 1487 | (100) | 172 | (100) | 4878 | (100) | 527 | (100) | 532 | (100) |

Fluvoxamine prescriptions (n=4) not shown.

PMS, premenstrual syndrome; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.

Discussion

Summary

Recording of PMS diagnoses in UK primary care decreased substantially between 1995 and 2013, and among those women with a PMS record, the preferred treatment has changed from progestogen to SSRIs and COCs.

Diagnoses

The main limitation of this study relates to the completeness of recording of PMS diagnoses. GPs may record the symptoms of a woman presenting with PMS, but not record a specific PMS diagnosis code. As a result, rates reported in this study represent the number of recorded diagnoses, and are unlikely to reflect the ‘true’ incidence of PMS in the community. Since the prevalence of ‘true’ diagnoses of PMS reported in prospective studies has not decreased over time,20 we suspect that the decrease in recording of PMS in primary care is likely to result from factors that influence the rate of consultations for premenstrual symptoms or recording practices such as changes in the perception of the syndrome by women and/or healthcare professionals.

Wyatt et al21 and Weisz and Knaapen22 investigated PMS recording in UK primary care from 1993 to 1998 and from 2004 to 2006, respectively. Direct comparison of our results with these two studies is not possible as the two previous studies used the total number of primary care consultations as the denominator for their recording rates. However, similar to our study, these two studies found that, relative to the prevalence of premenstrual symptoms reported in the literature, PMS diagnoses did not appear to be commonly recorded in UK primary care. The studies by Wyatt et al21 and Weisz and Knaapen22 also reported a decrease in recording rates over time; our results support these findings and illustrate that rates have continued to decrease to 2013.

Prescribing

Since prescriptions in THIN are not specifically linked to an indication, we cannot be certain that prescriptions issued after, or even on the date of, the PMS record were issued for the treatment of PMS. However, prescriptions issued on the date of a PMS record and not during the prior 6 months are likely to be specific to the treatment of PMS. While prescriptions issued over the 24 months after a PMS record are increasingly likely to be for indications other than PMS, delays between the first PMS record and initiation of pharmacological treatment may arise due to the completion of symptom diaries or initiation of non-pharmacological treatments as a first-line approach. As a result, the total proportion of women prescribed a pharmacological treatment in primary care after a PMS diagnosis should lie somewhere between the proportion with a prescription on the date of their PMS record (54%) and the proportion with a prescription in the 24 months after their PMS record (77%). If one assumes that women with a PMS record in our study are primarily those with moderate to severe symptoms, the above proportions compare with 40% of women in the UK, 44% of women in the USA and 25% of women in France with self-reported moderate to severe symptoms on prescription treatment in 1998.4

The changes in prescribing from 1995 to 1998 compare favourably with those reported by Wyatt et al21 for this period. Weisz and Knaapen22 reported stable proportions of prescriptions for different drug types in the UK over their 3-year study period (2004–2006); taken in isolation, our data for the same period also appear relatively stable. Our study, however, by covering a longer period allowed better observation of the changes in the type of PMS treatment prescribed over time with SSRIs and COCs superseding progestogen and oestrogen as the preferred treatments for PMS in primary care after 1999. The increasing use of SSRIs and decreasing use of progestogen in primary care is largely in line with the evolving evidence base for PMS treatments with a number of meta-analyses and guidelines supporting the effectiveness of SSRIs6 7 and questioning the effectiveness of progestogens.6 8 The increased prescribing of COCs is somewhat surprising given the limited evidence supporting their efficacy in the treatment of PMS.9 23 24 The limited evidence supporting the efficacy of oestrogen treatment for PMS25 26 and concerns surrounding its safety may explain the considerable decline in its use in the treatment of PMS. Notably, while concomitant progestogen treatment can mitigate some of the risk associated with oestrogen-based therapy, PMS symptoms produced by the progestogens limit the efficacy of combined oestrogen-progestogen therapy as a treatment for PMS. The preference for COCs over oestrogen therapy may reflect GPs’ greater familiarity with COCs relative to transdermal oestrogen therapy. Notably, since our data do not include gynaecologist and psychiatrist prescribing, the results cannot be generalised to changes in prescribing practices within such specialties.

As pointed out by Wyatt et al,21 the decrease in vitamin B6 use in 1998 and 1999 is likely to have resulted from the discovery that high doses might result in peripheral neuropathy and subsequent proposals to restrict access to the drug. Our data confirm that vitamin B6 prescribing has continued to decrease slightly since 1998. However, since vitamin B6 is also sold over the counter (OTC), this decrease in use may result from an increase in the consumption of OTC vitamin B6. Since Danazol and GnRH analogues are not typically used as first-line or second-line treatment, it is unsurprising that few women are prescribed these drugs in the 24 months after their first PMS record.

The increasing proportion of SSRI prescriptions for citalopram and sertraline, decreasing proportion for paroxetine and escitalopram and stable proportion for fluoxetine are in line with trends in the use of SSRIs in general in the UK (R McCrea, C Sammon, I Nazareth, et al. Initiation and duration of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor prescribing over time: a UK cohort study. Br J Psychiatry (manuscript in preparation) 2015). However, in the general population, the rate of initiation of citalopram is now greater than that of fluoxetine, whereas in our study fluoxetine remains the treatment most commonly initiated on the day of a PMS record (R McCrea, et al. (Under review) 2015). This difference may reflect the larger evidence base for the use of fluoxetine for the treatment of premenstrual syndrome, with a recent meta-analysis7 and systematic review6 including 6–10 studies on fluoxetine but only one on citalopram. The doses of each SSRI prescribed were largely in line with the recommended dose for the treatment of depression in the UK.27 Unfortunately, no information was available on the dosing schedule for SSRIs (continuous vs luteal phase only) or COCs (cyclical vs continuous).

We were unable to investigate the prevalence of use of non-prescription medications, dietary supplements, complementary and alternative therapies and lifestyle/behaviour changes in the treatment of PMS in this study. While few data on trends in the use of these therapies for PMS have been published, increases in the use of these treatment options may have contributed to the reduction in the use of some of the prescription medications observed in this study. Additionally, the increased use of such therapies may lead women not to consult GPs, thereby contributing to the decreased rate of PMS diagnoses recorded in primary care.

Conclusions

The recording of PMS diagnoses in UK primary care has declined between 1995 and 2013. Further work is needed to establish whether this is due to the decreased recording of PMS diagnoses in the records of women with premenstrual symptoms or whether it is due to a decrease in the number of women presenting in primary care with premenstrual symptoms. If the former is true, future research might investigate how the perception of PMS among GPs has changed, while if the latter is true future research might focus on how the perception of PMS among women has changed and whether the use and/or efficacy of non-prescription therapies for PMS has influenced women's healthcare-seeking behaviour. Changes in the preferred prescription treatment for PMS in primary care, from progestogens to SSRIs and COCs, are largely in line with current evidence and guidelines.

Footnotes

Contributors: CS had the original idea for the study. CS, IN and IP designed the study. CS performed the analysis. CS, IN and IP interpreted the results. CS drafted the manuscript. IP and IN revised it critically for important intellectual content. CS, IN and IP approved the final version to be published.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: THIN has overall ethical approval from the South East Multicentre Research Ethics Committee (reference number: 07/H1102/103).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Usman SB, Indusekhar R, O'Brien S. Hormonal management of premenstrual syndrome. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2008;22:251–60. 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2007.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th edn Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Halbreich U, Borenstein J, Pearlstein T et al. The prevalence, impairment, impact, and burden of premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMS/PMDD). Psychoneuroendocrinology 2003;28(Suppl 3):1–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hylan TR, Sundell K, Judge R. The impact of premenstrual symptomatology on functioning and treatment-seeking behavior: experience from the United States, United Kingdom, and France. J Womens Health Gend Based Med 1999;8:1043–52. 10.1089/jwh.1.1999.8.1043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Angst J, Sellaro R, Merikangas KR et al. The epidemiology of perimenstrual psychological symptoms. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2001;104:110–16. 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2001.00412.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown J, O’ Brien PM, Marjoribanks J et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for premenstrual syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009;(2):CD001396 10.1002/14651858.CD001396.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shah NR, Jones JB, Aperi J et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder: a meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol 2008;111: 1175–82. 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31816fd73b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wyatt K, Dimmock P, Jones P et al. Efficacy of progesterone and progestogens in management of premenstrual syndrome: systematic review. BMJ 2001;323:776–80. 10.1136/bmj.323.7316.776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lopez LM, Kaptein AA, Helmerhorst FM. Oral contraceptives containing drospirenone for premenstrual syndrome. In: Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2012. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD006586.pub4/abstract. (accessed 6 Aug 2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Daley A. Exercise and premenstrual symptomatology: a comprehensive review. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2009;18:895–9. 10.1089/jwh.2008.1098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dante G, Facchinetti F. Herbal treatments for alleviating premenstrual symptoms: a systematic review. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol 2011;32:42–51. 10.3109/0167482X.2010.538102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Whelan AM, Jurgens TM, Naylor H. Herbs, vitamins and minerals in the treatment of premenstrual syndrome: a systematic review. Can J Clin Pharmacol J Can Pharmacol Clin 2009;16:e407–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lustyk MKB, Gerrish WG, Shaver S et al. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder: a systematic review. Arch Womens Ment Health 2009;12:85–96. 10.1007/s00737-009-0052-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Green-top Guideline No. 48 Management of Premenstrul Syndrome 2007. https://www.rcog.org.uk/globalassets/documents/guidelines/gt48managementpremensturalsyndrome.pdf (accessed 12 Mar 2014).

- 15.Nevatte T, O'Brien PM, Bäckström T et al. ISPMD consensus on the management of premenstrual disorders. Arch Womens Ment Health 2013;16:279–91. 10.1007/s00737-013-0346-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davé S, Petersen I. Creating medical and drug code lists to identify cases in primary care databases. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2009;18:704–7. 10.1002/pds.1770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chisholm J. The Read clinical classification. BMJ 1990;300:1092 10.1136/bmj.300.6732.1092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maguire A, Blak BT, Thompson M. The importance of defining periods of complete mortality reporting for research using automated data from primary care. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2009;18:76–83. 10.1002/pds.1688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Horsfall L, Walters K, Petersen I. Identifying periods of acceptable computer usage in primary care research databases. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2013;22:64–9. 10.1002/pds.3368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ashraf DM, Kourosh S, Ali D et al. Epidemiology of Premenstrual Syndrome (PMS)-A systematic review and meta-analysis study. J Clin Diagn Res 2014;8:106–9. 10.7860/JCDR/2014/8024.4021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wyatt KM, Dimmock PW, Frischer M et al. Prescribing patterns in premenstrual syndrome. BMC Womens Health 2002;2:4 10.1186/1472-6874-2-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weisz G, Knaapen L. Diagnosing and treating premenstrual syndrome in five western nations. Soc Sci Med 2009;68:1498–505. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.01.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bancroft J, Rennie D. The impact of oral contraceptives on the experience of perimenstrual mood, clumsiness, food craving and other symptoms. J Psychosom Res 1993;37:195–202. 10.1016/0022-3999(93)90086-U [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Graham CA, Sherwin BB. A prospective treatment study of premenstrual symptoms using a triphasic oral contraceptive. J Psychosom Res 1992;36:257–66. 10.1016/0022-3999(92)90090-O [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Studd J, Cronje W. Transdermal estrogens for the treatment of premenstrual syndrome 2015. http://www.studd.co.uk/pms_transdermal.php (accessed 8 Jun 2015).

- 26.Magos AL, Brincat M, Studd JW. Treatment of the premenstrual syndrome by subcutaneous estradiol implants and cyclical oral norethisterone: placebo controlled study. BMJ 1986;292:1629–33. 10.1136/bmj.292.6536.1629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Joint Formulary Committee. British National Formulary (BNF). 66th edn. London, UK: Pharmaceutical Press, 2013. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2015-010244supp.pdf (490.2KB, pdf)