Abstract

Objective

To minimise the intake of industrially produced trans fat (I-TF) and thereby decrease the risk of coronary heart disease (CHD), nearly all European countries rely on food producers to voluntarily reduce the I-TF content in food. The objective of this study was to monitor the change in presence of I-TF in biscuits/cakes/wafers in six countries in South-eastern Europe from 2012 to 2014, including two members of the European Union (Slovenia and Croatia).

Design

Three large supermarkets were visited in each of the six capitals in 2012. Pre-packaged biscuits/cakes/wafers were bought if the products contained more than 15 g of total fat per 100 g of product and if partially hydrogenated oil or a similar term was disclosed at the beginning of the ingredients list. These same supermarkets were revisited in 2014 and the same collection procedure was followed. All foods were subsequently analysed for total fat and trans fat in the same laboratory.

Results

The number of packages bought in the six countries taken together was 266 in 2012 and 643 in 2014. Some were identical, and therefore only 226 were analysed in 2012 and 434 in 2014. Packages with less than 2% of fat from I-TF went up from 69 to 235, while products with more than 2% (illegal in Denmark) doubled from an average of 33 to an average of 68 products for the six countries, with considerable variation across countries. The per cent of I-TF in total fat decreased slightly, from a mean (SD) of 22 (13) in 2012 to 18 (9) in 2014.

Conclusions

The findings suggest that voluntary reduction of I-TF in foods with high amounts is an ineffective strategy in several European countries. Alternative strategies both within and outside the European Union are necessary to protect all subgroups of the populations against an increased risk of CHD.

Keywords: NUTRITION & DIETETICS, EPIDEMIOLOGY, PREVENTIVE MEDICINE

Strengths and limitations of this study.

A strength of this study is that the same procedure to obtain popular foods found in large supermarkets in European capitals in 2012 was followed in the same supermarkets in 2014, and products were analysed for industrially produced trans fat (I-TF) in the same laboratory.

A limitation is that the average daily intake of I-TF was not measured in any subgroup of the population, but instead was inferred from the availability of popular foods with high amounts of I-TF in large supermarkets.

Another limitation is that no other food groups (such as shortenings and margarines) and no unpackaged foods (such as baked goods, sweet rolls, pastries and buns) were investigated. Further, biscuits/cakes/wafers that did not have the words partially hydrogenated fats or similar terms in the list of ingredients were not investigated.

Introduction

High amounts of trans fat (TF) in food originate from the industrial hydrogenation of oils. Compared to non-hydrogenated oils, fats containing industrially produced trans fat (I-TF) are solid at room temperature, have some technical advantages for food processing, and prolong the shelf life of products. A meta-analysis of four large prospective studies found that an average intake of approximately 5 g/day of TF, corresponding to 2% of the total energy intake, was associated with a 23% increase in the risk of coronary heart disease (CHD).1 More recently, I-TF intake was associated with all-cause mortality in a large US-based study.2 A 2013 review concluded that ‘the detrimental effects of industrial trans fatty acids on heart health are beyond dispute’.3

On the basis of the relationship between the intake of I-TF and CHD, several public health organisations, as well as the WHO in 2006, have recommended for years that I-TF intake be lowered as much as possible. More recently, the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and European Association of Rehabilitation and Prevention have also recommended a legislative limit on I-TF in foods.4 In the USA, by a final determination, the Food and Drug Administration FDA recently revoked the previous Generally Recognized As Safe (GRAS) status of partially hydrogenated oils—a step that led the ESC to call on European policymakers to introduce a legislative limit on I-TF in foods.5 6

In 2003, Denmark introduced a legislative sales ban aimed at the final consumer, limiting the I-TF content in the total fat of foods to a maximum of 2%. The legislation applies to locally produced as well as imported foods. In 2009, Austria and Switzerland introduced a legislative ban similar to the Danish ban, followed by Iceland in 2011, Hungary and Norway in 2014 and Latvia starting in 2016. However, currently, only a minority of the population in Europe (less than 50 million of the 500 million people in the European Union) and none of the population of most neighbouring countries are protected by legislation that makes it illegal to sell foods with high amounts of I-TF. One argument against a legislative limit in some large European countries is that I-TF is already gradually disappearing due to voluntary reductions by the food producers. The purpose of the present study was to investigate to what extent this was the case in a number of countries that previously sold many popular products with high amounts of I-TF. The availability of many different prepackaged biscuits/cakes/wafers with high amounts of I-TF in large supermarkets in six countries in South-eastern Europe was observed in 2012.7 In this study, the changes in availability of this type of food from 2012 to 2014 were investigated.

Methods

Purchase of biscuits/cakes/wafers in supermarkets

The six countries visited encompass Slovenia, Croatia, Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro and the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia (FYROM). In 2012, we asked the main tourist office in the capital of each country to identify three large supermarkets, preferably chain supermarkets with many large shops across the country. The same stores were visited in 2014. Prepackaged biscuits/cakes/wafers were chosen because they are frequently consumed and are easily accessible. Furthermore, these foods traditionally contain I-TF-rich, partially hydrogenated vegetable oils as their major lipid ingredient and I-TF has previously been found in high concentrations in Serbian biscuits.8 The packages of biscuits/cakes/wafers were obtained by systematically examining the labels of the products placed on the appropriate shelves in the supermarkets. Packages were purchased if they met the following criteria:

‘Partially hydrogenated fat’ or a similar term was listed among the first 4 on the list of ingredients (which are ranked according to content). Packages with the term ‘unhydrogenated fat’ or ‘fully hydrogenated fat’ were not purchased.

Total fat content was equal to or exceeded 15 g per 100 g of product. High fat foods are generally defined as containing more than 15–20 g of total fat per 100 g of food.

If the same product appeared in packages of different sizes, only the smallest size was bought. If the same package with the same barcode ID number was found in two different supermarkets in the same capital, only the one with the most distant ‘best before’ date was included in the study. Each package was subsequently labelled, and duplicate samples were taken for analysis. The barcode number, the name of the producer, the country of origin and the ‘best before’ date were all registered and the empty packages were stored. In the occasional event that the food producers had two consecutive names, we allocated only the first name to the food.

Analysis of TF

The foods were homogenised, and the fatty acid content was analysed using gas chromatography on a 60 m highly polar capillary column using a modification of the AOAC 006·06 method. All analytical work on samples obtained in 2012 and in 2014 was conducted by Microbac Laboratories in Warrendale, Pennsylvania, USA, an ISO-17025-certified laboratory. The measurement cannot distinguish I-TF from ruminant TF. If butter as a ruminant fat has been used in the product in addition to partially hydrogenated vegetable oil, some of the TF in the product may be derived from butter that on average contains a few per cent of the fat as TF. In this paper, the term I-TF is used in spite of the fact that a minor part may be TF derived from ruminant fat.

Results

Products

The number of packages bought in the six countries taken together was 266 in 2012 and 643 in 2014. Some were identical, and therefore only 226 were analysed in 2012 and 434 in 2014. Packages with less than 2% of fat from I-TF went up from 69 to 235, while products with more than 2% (illegal in Denmark) went up from 197 to 408. In spite of this absolute increase in numbers, the proportion of products with more than 2% I-TF of all the products fulfilling the inclusion criteria fell from 74% to 63%.

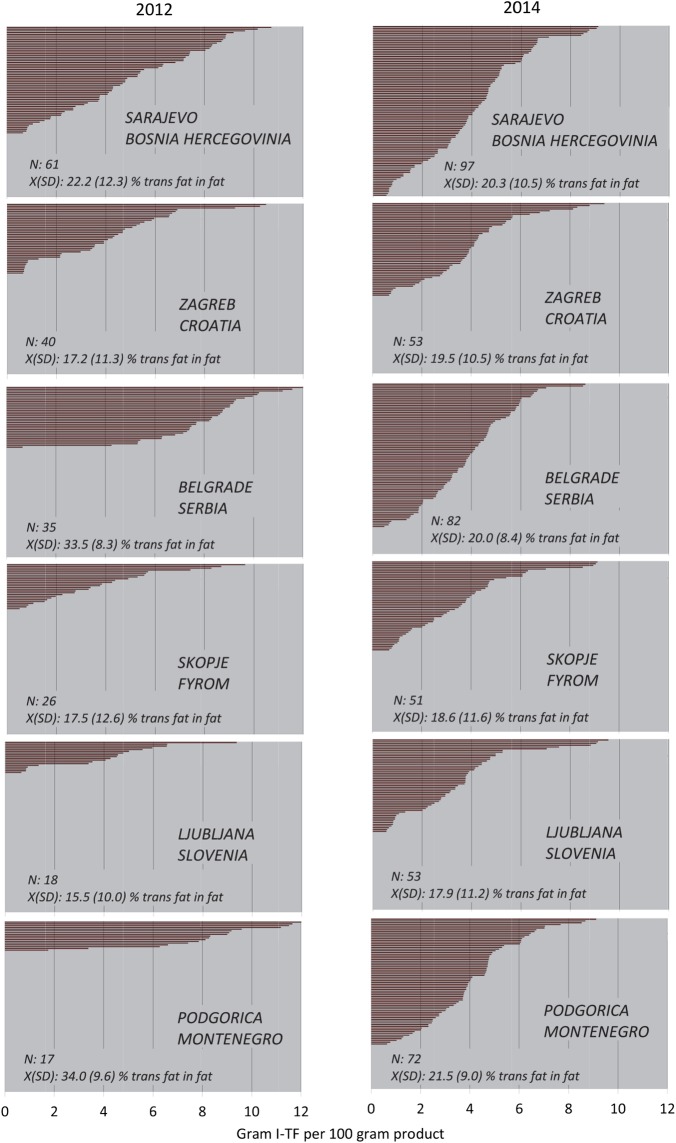

The content of I-TF in the products in each country was ranked according to I-TF level, expressed as grams per 100 g of the product (figure 1). Each bar in each panel represents a product. Only products in which more than 2% of the fat content was I-TF are shown. For each country, the products depicted in the panel are different, but the same product may appear in two or more countries. A large increase in the number of these foods from 2012 to 2014 was observed for each of the six countries shown in figure 1. The mean values of the percentages of fat that were I-TF declined slightly in each of the countries, mainly because of the disappearance of a few products, with more than 40% of the fat as I-TF. In all of the shops, there were more packages that did not have the words partially hydrogenated fats or hydrogenated fats on the label than packages that had these words on the label in 2012 as well as in 2014, which means that there are plenty of biscuits/cakes/wafers without I-TF available in these supermarkets.

Figure 1.

Amounts of industrially produced trans fat (I-TF) in 100 g of prepackaged biscuits/cakes/wafers with more than 2% I-TF of the total fat content purchased in three supermarkets in each of the six capitals in 2012 and again in the same supermarkets in 2014. Each bar in a panel represents a unique product bought in that capital, that is, none of the products had the same barcode number. N is the number of products. X (SD) is the mean value and the SD of the percentages of I-TF in the total fat of the N products.

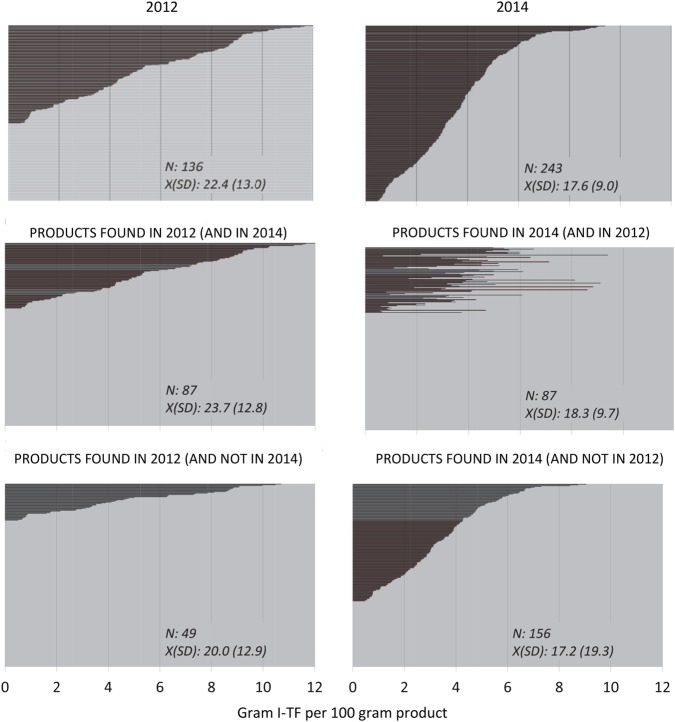

There is a considerable overlap of products with more than 2% of the total fat as I-TF in the six countries in 2012 and in 2014. The numbers of unique products (ie, products with different barcode numbers) in the six countries, taken together in 2012 and in 2014, are shown in figure 2 in the two upper panels. The number of unique products increased from 136 to 248 (80%). The mean concentration of I-TF in total fat in these products went down from 22.4% in 2012 to 17.6% in 2014.

Figure 2.

The numbers of unique products, that is, prepackaged biscuits/cakes/wafers with more than 2% of the total fat as I-TF and with different barcode numbers, in the six countries taken together in 2012 and in 2014 are shown in the two upper panels. The two panels in the middle show, for each of the 87 products that were present in 2012 and 2014 with the same barcode ID-number, how the amounts of I-TF in the same product have changed from 2012 to 2014. The lower panel in the 2012 column shows the amounts of I-TF in products that were present in 2012 but not in 2014. The lower panel in the 2014 column shows the 156 new products in 2014 that did not appear in the supermarkets in 2012. N is the number of products. X (SD) is the mean value and the SD of the percentages of I-TF in the total fat of the N products. The Y-axes in the six panels are all equally spaced. I-TF, industrially produced trans fat.

The two panels in the middle of figure 2 show how, for each of the 87 different products that fulfilled the inclusion criteria in 2012 and 2014 and had the same barcode ID number and the same selling name on the packages, the amounts of I-TF in the same product have changed during this period. The amounts of I-TF as a per cent of total fat decreased in 59 of the packages from 2012 to 2014. The largest decrease was 34% points (from 40% to 6%). The mean decrease for the 59 products was 11.5 (8.5) % points. Products in three of the 87 packages had the same per cent of I-TF in the total fat in 2012 and 2014, whereas 25 of the products had a higher per cent of I-TF in 2014 than in 2012. The highest increase was 34% point (from 8% to 42%). The mean increase for the 25 products was 8.4 (7.8) % points. The mean value for all 87 products taken together decreased from 23.7% to 18.3% I-TF in the total fat.

The lower panel in the 2012 column in figure 2 shows the amounts of I-TF in products that were present in 2012 but not in 2014. Some 49 different products with an average of 20 (13) % of I-TF in total fat were removed between 2012 and 2014. The lower panel in the 2014 column shows in the same way the amounts of I-TF per 100 g product of the 156 new products in 2014 that did not appear in the supermarkets in 2012. Some of these new products were very high in amounts of I-TF.

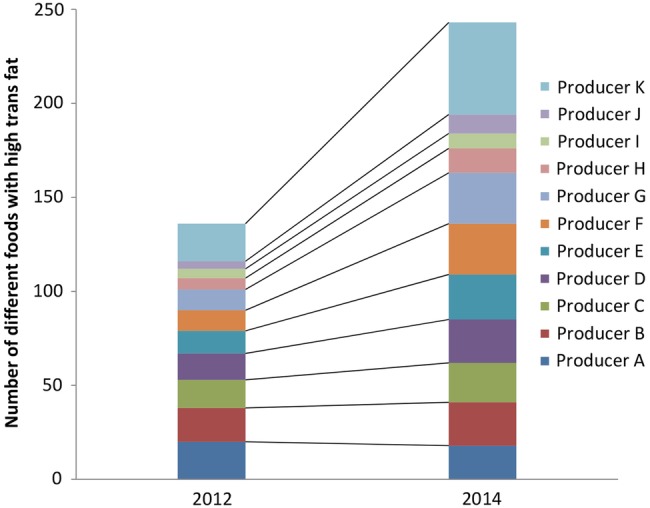

Producers of biscuits/cakes/wafers

The number of different producers of biscuits/cakes/wafers with more than 2% of the total fat as I-TF increased from 24 to 33 between 2012 and 2014. The top 10 producers were the same in 2012 and 2014 and together provided approximately 80% of the products in 2012 as well as in 2014 (figure 3). Table 1 show some characteristics of the products from each of the main producers.

Figure 3.

Number of different prepackaged biscuits/cakes/wafers with more than 2% of the total fat as I-TF bought in one or more of the six capitals in South-eastern Europe and allocated to the top 10 producers designated producer A to producer J, with producer A with the highest number of different products (20) in 2012. For 2012, producer K represents the sum of products from the remaining 14 producers. For 2014, producer K represents the sum of products from the remaining 23 producers. I-TF, industrially produced trans fat.

Table 1.

Each of the top 10 producers designated producer A to producer J with mean and maximum values of I-TF as % of total fat for their different prepackaged biscuits/cakes/wafers with more than 2% of total fat as I-TF, obtained in one or more of three supermarkets in one or more of six countries in South-eastern Europe in 2012 and again in 2014

|

Trans fat as % of total fat |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) |

Max values |

|||||

| 2012 |

2014 |

2012 | 2014 | |||

| Producer A | 6.4 | (4.9) | 8.4 | (5.7) | 16.8 | 15.7 |

| Producer B | 15.4 | (5.9) | 14.2 | (8.4) | 27.4 | 39.6 |

| Producer C | 37.2 | (3.8) | 17.6 | (6.4) | 42.3 | 29.7 |

| Producer D | 18.7 | (10.1) | 28.2 | (9.8) | 41.8 | 43.7 |

| Producer E | 31.4 | (9.1) | 17.5 | (7.5) | 42.7 | 28.3 |

| Producer F | 29.3 | (7.3) | 21.9 | (6.4) | 35.5 | 32.9 |

| Producer G | 31.1 | (12.2) | 24.5 | (7.6) | 44.7 | 34.2 |

| Producer H | 33.6 | (10.8) | 24.0 | (2.5) | 41.3 | 27.8 |

| Producer I | 23.2 | (7.9) | 12.3 | (4.9) | 36.8 | 17.4 |

| Producer J | 4.4 | (2.0) | 4.2 | (1.3) | 6.3 | 6.1 |

| Producer K* | 22 | (11.7) | 13.5 | (7.9) | 40.9 | 34.1 |

*For 2012, producer K represents the sum of products from the remaining 14 producers. For 2014, producer K represents the sum of products from the remaining 23 producers.

I-TF, industrially produced trans fat.

The average amount of I-TF as a percentage of total fat among the top 10 producers ranged from 4.4 (2) to 37.2 (3.8) in 2012 and from 4.2 (1.3) to 28.2 (9.8) in 2014. Among the top 10 providers in 2012, seven used fat with more than 30% I-TF in total fat in some of their products; in 2014, five of the top 10 providers still used fat with more than 30% I-TF of total fat in some of their products.

Discussion

The principal finding

The findings of this study clearly demonstrate that in 2014, I-TF was still present in high concentrations in many different brands of popular foods in each of the six countries in South–eastern Europe, and the number of different packages with high amounts of I-TF has increased considerably since 2012 (figure 1). The voluntary reduction in the amount of I-TF in foods by food producers appears to work well in some European countries but not—as demonstrated here—in others.7 With altogether 23 different producers of prepackaged biscuits/cakes/wafers with high amounts of I-TF in 2012 and with an increase to 33 different producers in 2014 (figure 3) and a competitive market, the possibility of an effective voluntary reduction in I-TF is probably slim.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

A strength of this study is that the same procedure to obtain popular foods found in large supermarkets in six European capitals in 2012 was followed in the same supermarkets in 2014, and that the products were analysed for I-TF in the same laboratory. The study demonstrates that I-TF is used in the prepackaged foods that were analysed and that the presence of these foods has increased considerably in just 2 years. I-TF was not measured in products collected in 2012 and in 2014 that did not meet the inclusion criteria. It leaves the theoretical possibility that more products contained I-TF in 2012 than appears from the measurements (but there is also the possibility that more products contained I-TF in 2014 than was observed in this study). The suggestion about an increase in the presence of foods with high amounts of I-TF from 2012 to 2014 rests on the assumption that the number of foods with appreciable amounts of I-TF but without partially hydrogenated fat or similar term in the list of ingredients is small in 2012 and in 2014 compared with the number of foods that fulfil the inclusion criteria. The assumption seems justified, first of all, because it is illegal in most European countries to omit labelling if partly hydrogenated fat is present in prepackaged food. Many of the prepacked biscuits/cakes/wafers on the shelves in the supermarkets in the six countries have in the list of ingredients several other languages such as English, German or French in addition to the local language and the language of the country of origin. This means that the products were also meant for export. It seems unlikely that food producers would risk an export to a big market because of misleading information that public food or health authorities in any country could easily reveal.

A considerable number of products had less than 2% of total fat as I-TF in spite of the term partly hydrogenated fat or similar term in the list of ingredients. This may be due to the consideration of some food producers that a mixture of cis unsaturated fat and fully hydrogenated fat without I-TF is understood to be partially hydrogenated fat. An additional explanation is an effort of the producer to empty stores of old package material after a change of the recipe to fat without I-TF even if the recipe is permanently changed. If the recipe only is temporarily changed due to favourite prices for non-hydrogenated fat, the producer may find it better to maintain the term partly hydrogenated fat even though the food temporarily is without I-TF. The increase in number of these packages, together with an increase in number of packages containing foods with more than 2% of the fat as I-TF, suggests an increase in sale of all biscuits/cakes/wafers. The competition of shelf space in supermarkets is usually fierce. If products do not sell, they are rapidly replaced by other products.

It is unknown why there has been such a large increase in the availability of these foods with high amounts of I-TF in all of these six European countries between 2012 and 2014. One possibility is aggressive marketing efforts by the relatively few large producers in these countries (figure 1). Another possibility is that the economic downturn that all of these countries experienced in 2013 and 2014 created financial constraints and led consumer demand for cheap candy-like food such as prepackaged biscuits/cakes/wafers to increase.

The presence of high concentrations of I-TF in biscuits/cakes/wafers may be a sign that I-TF is used in other foods as well. This is supported by the high concentrations recently reported in certain brands of Serbian margarine.9 Other internationally published reports about I-TF in other foods in these countries are non-existent.

A limitation of this study is that no other food groups (such as shortenings and margarines) and no unpackaged foods (such as baked goods, sweet rolls, pastries and buns) were investigated. Another limitation is that the average daily intake of I-TF was not measured in any subgroup of the populations but instead was inferred from the availability of popular foods with high amounts of I-TF in large supermarkets. A relevant subgroup would be the consumers who buy biscuits/cakes/wafers.

Voluntary reduction of I-TF in foods

Each of the top 10 producers in 2012 of biscuits/cakes/wafers except one—producer A—has increased the number of different foods with high I-TF in 2014 compared with 2012 (figure 3). It suggests that the intake of I-TF increased during this period. A considerable increase or reduction in the concentration of I-TF in a given product appeared when products obtained in 2014 were compared with products obtained in 2012 with the same barcode number and the same selling name (figure 2, right panel in the middle). This variation suggests that the recipe for some of the products do not require the same I-TF concentration from batch to batch. The I-TF concentration apparently depends on the price and availability of the fat used for the production of the product, considerations that seem to outweigh the recommendation to minimise the use of I-TF in human food. If a producer removed I-TF from a product between 2012 and 2014 and, at the same time, removed the term partially hydrogenated fat from the list of ingredients, the product will not appear in our 2014 purchase, since it did not fulfil the inclusion criteria. This may explain the disappearance of at least some of the 49 products between 2012 and 2014 (figure 2 lowest panel to the left).

When voluntary reduction of I-TF in foods does not work, labelling of prepackaged foods with the contents of I-TF is an alternative. This method has been used in the USA since 2006 but will be eliminated when the new regulation fully takes effect in 2018.5 Although labelling prepackaged foods in Europe with I-TF content may further reduce the mean intake of I-TF, such labelling still allows for the intake of high amounts because unpacked foods and foods in restaurants are not labelled, and also because consumers might not pay attention to or understand the labels.10 An important advantage of a legislative limit on the I-TF content of food is that it does not require that the population learn about the health risks of I-TF. Furthermore, it is simpler and less expensive to monitor the presence of I-TF in foods at the sales level than to monitor the actual intake of I-TF at the individual level in at-risk subgroups of the population.

Intake of I-TF in subgroups

Certain subgroups, such as patients with severe atherosclerotic heart disease, have been told by their physicians or have read in the lay press since 1994 that I-TF is bad for the heart; many will thus avoid this type of food and have a low intake of I-TF. This may explain the very low TF concentrations found in the red blood cells of patients admitted to a tertiary heart centre in Germany between 1997 and 2001 for coronary angiography due to chest pain or other signs of myocardial ischaemia.11 The TF concentrations in red blood cells reflect the intake of TF of only several weeks.12 Even people who accept to be enrolled in studies concerning diet and health may comprise a relatively health-conscious subgroup with a low intake of I-TF.13 The low contents of TF in the blood in health-conscious subgroups of the population thus do not preclude the existence of other subgroups with a much higher intake of I-TF. A recent study from 9 EU countries reports that in spite of a low average daily intake of TF, specific subgroups exist with average intake values above the WHO maximum recommended level of 1 energy % of total TF.14 A vicious cycle apparently occurs: as long as foods with high amounts of I-TF are present in the shops, some consumers will buy them, and as long as they are bought, the foods will be available.

Since many of the biscuits/cakes/wafers in the 18 supermarkets that were visited and revisited in this study did not have the words partially hydrogenated fat or hydrogenated fat on the label, a legislative I-TF limit would not affect the supply of these foods. Even a one-to-one replacement of I-TF with saturated fat may confer a health benefit.15

WHO-Europe recently investigated the various ways to reduce I-TF in foods and concluded that establishing a legal limit for the content of I-TF in foods is potentially the only available option that reduces the risks associated with I-TF faced by all consumers, and doing so may contribute to reducing inequalities. Such a policy is unique in its combination of efficacy, cost-effectiveness and low potential for negative impact. Removing I-TF from the food supply is possibly one of the most straightforward public health interventions for reducing risk of CHD.16

I-TF legislation and CHD

Danish males and females appear to have had the highest reduction in CHD mortality in the European Union from 2000 to 2009.17 This was further investigated by comparing the decline in CHD mortality in a so-called synthetic Denmark, consisting of a composite group of OECD countries, with the observed decline in Denmark. The composite group simulated the observed decline in Denmark from 1990 to 2004, but from 2004 to 2007 the CHD mortality observed was lower than in the synthetic Denmark, corresponding to 14.2 fewer deaths per 100 000 inhabitants per year.18 The authors ascribe this reduction to the Danish I-TF legislation implemented in 2004, 3 years before the Danish antismoking legislation. Owing to reports in 1994, 2001 and 2003 from the Danish Nutrition Council about the harmful effects of I-TF in foods and subsequent media interest, most health-conscious Danes did not consume products with potentially high amounts of I-TF several years before the I-TF legislation in 2004. The extra decline in CHD mortality after the 2004 I-TF legislation in Denmark may have been due to the effect on less health-conscious consumers in particular and thereby helped reduce health inequalities. This observation supports the hypothesis that healthy environments appear to promote health more than healthy choices, as suggested by a British study quantifying the socioeconomic benefits of reducing I-TF in foods.19 Findings based on ecological data should be interpreted with care. A change in treatment guidelines for CHD in Denmark in 2003 and 2004 was therefore scrutinised. Late in 2003, acute PCI (percutaneous coronary intervention) was introduced in Denmark as the recommended treatment for acute myocardial infarct with ST-segment-elevation in the ECG (STEMI). Patients with STEMI were transported to the nearest of five centres for acute PCI. This plan was based on the findings that acute PCI at the nearest heart centre was superior to fibrinolysis, the usual treatment at the local hospital.20 Although there was a significant reduction in the composite end point consisting of death and reinfarction in the group from the referral hospital receiving acute PCI compared with the group receiving the usual fibrinolytic treatment, there was no significant difference in coronary mortality. After a 7.8 years follow-up period, the cumulative coronary death rate in the group from the referral hospital that received acute PCI was 12.4% versus 15.6% (p=0.06) in the group that received fibrinolysis at the local hospital.21 The national change in treatment of STEMI may thus have added only marginally to the reduction in coronary death in 2004 and the following years.

An investigation of the effect on CHD mortality of a legislative TF limit in some counties in New York State compared with counties that did not have this limit suggests that the policy reduced the CHD mortality to the same extent as was observed in Denmark.22

Unanswered questions and future research

It is of considerable interest if coronary mortality did change after introduction of trans fat legislation in countries such as Iceland, Switzerland, Austria and Hungary and if it will change in Norway, Latvia and Georgia,23 countries that more recently have introduced legislation that restricts the use of I-TF.

If reduction of I-TF in foods reduces CHD, as seems likely, it follows that increased I-TF in foods increases CHD. It is of interest to discover the extent to which the increasing intake of I-TF contributed to the increase in CHD in the Western hemisphere from 1950 until its peak in 1970 to 1980 and to what extent the decline in intake of I-TF has contributed to the subsequent decline in CHD.

Globally, CHD is still the leading cause of death in spite of the recent decline in several countries. On the basis of data from 2009 to 2011, there is a 10-fold difference in age-standardised mortality rates of CHD between some countries within WHO-Europe, with countries in Central Europe, Eastern Europe and Central Asia having the highest rates.24 It is unknown why, when taken together, these countries had only a 2.8% reduction in CHD mortality between 1990 and 2010, in contrast to the global reduction of 19.5% and the more than 40% reduction in several Western European countries during the same period.25 It seems obvious to investigate the presence of I-TF in popular foods in these countries with excessively high CHD mortality.

Finally, it will be interesting to investigate the reasons for the resistance to implementing a legal limit for I-TF in foods in the European Union for more than 10 years now in spite of the facts that such a legislation has already been introduced in several European countries, is strongly recommended by various scientific organisations, and has been found by the WHO to be the cheapest and most effective way to reduce CHD.26

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support from Jenny Vissings Foundation, University of Copenhagen and the Department of Clinical Biochemistry, Copenhagen University Hospital, Gentofte.

Footnotes

Contributors: SS was responsible for the concept design of the study, for collection of food items, registration and labelling. SS produced the first draft of the study and SS, JD and AA were responsible for critical revision of the manuscript. SS is the manuscripts guarantor.

Funding: Department of Clinical Biochemistry, Gentofte Hospital; Jenny Vissings Foundation.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Mozaffarian D, Katan MB, Ascherio A et al. . Trans fatty acids and cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med 2006;354:1601–3. 10.1056/NEJMra054035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kiage JN, Merrill PD, Robinson CJ et al. . Intake of trans fat and all-cause mortality in the Reasons for geographical and Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) cohort. Am J Clin Nutr 2013;97:1121–8. 10.3945/ajcn.112.049064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brouwer IA, Wanders AJ, Katan MB. Trans fatty acids and cardiovascular health: research completed? Eur J Clin Nutr 2013;67:541–7. 10.1038/ejcn.2013.43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Position Paper on Industrial Trans Fatty Acids. http://www.escardio.org/static_file/Escardio/EU-Affairs/esc-position-paper-on-tfa.pdf?hit=escweb… (accessed Feb 2016).

- 5.FDA Cuts Trans Fat in Processed Foods. http://www.fda.gov/ForConsumers/ConsumerUpdates/ucm372915.htm (accessed Feb 2016).

- 6.ESC statement in response to the FDA determination. http://www.escardio.org/The-ESC/Press-Office/Press-releases/Last-5-years/esc-press-release-in-response-to-the-fda-determination-that-trans-fatty-acids-ar… (accessed Feb 2016).

- 7.Stender S, Astrup A, Dyerberg J. Tracing artificial trans fat in popular foods in Europe: a market basket investigation. BMJ Open 2014;4:e005218 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kravic SZ, Suturovic ZJ, Svarc-Gajic JV et al. . Fatty acid composition including trans-isomers of Serbian biscuits. Hem Ind 2011;65:139–46. 10.2298/HEMIND101001078K [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vučić V, Arsić A, Petrović S et al. . Trans fatty acid content in Serbian margarines: urgent need for legislative changes and consumer information. Food Chem 2015;185:437–40. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.04.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jasti S, Kovacs S. Use of trans fat information on food labels and its determinants in a multiethnic college student population. J Nutr Educ Behav 2010;42:307–14. 10.1016/j.jneb.2009.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kleber ME, Delgado GE, Lorkowski S et al. . Trans fatty acids and mortality in patients referred for coronary angiography: the Ludwigshafen Risk and Cardiovascular Health Study. Eur Heart J 2015:pii: ehv446. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hodson L, Skeaff CM, Fielding BA. Fatty acid composition of adipose tissue and blood in humans and its use as a biomarker of dietary intake. Prog Lipid Res 2008;47:348–80. 10.1016/j.plipres.2008.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kröger J, Zietemann V, Enzenbach C et al. . Erythrocyte membrane phospholipid fatty acids, desaturase activity, and dietary fatty acids in relation to risk of type 2 diabetes in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC)-Potsdam Study. Am J Clin Nutr 2011;93:127–42. 10.3945/ajcn.110.005447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mouratidou, et al. Trans Fatty acids in Europe: where do we stand? JRC Science and Policy Reports 2014:30–35. https://ec.europa.eu/jrc/en/publication/eur-scientific-and-technical-research-reports/trans-fatty-acids-europe-where-do-we-stand (accessed Feb 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Souza RJ, Mente A, Maroleanu A et al. . Intake of saturated and trans unsaturated fatty acids and risk of all cause mortality, cardiovascular disease, and type 2 diabetes: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. BMJ 2015;351:h3978 10.1136/bmj.h3978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eliminating trans fats in Europe—A policy brief (2015). http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/disease-prevention/nutrition/publications/2015/eliminating-trans-fats-in-europe-a-policy-brief-2015 (accessed Feb 2016).

- 17.Nichols M, Townsend N, Scarborough P et al. . Trends in age-specific coronary heart disease mortality in the European Union over three decades: 1980–2009. Eur Heart J 2013;34:3017–27. 10.1093/eurheartj/eht159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Restrepo BJ, Rieger M. Denmark's policy on artificial trans fat and cardiovascular disease. Am J Prev Med 2016;50:69–76. 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.06.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Allen K, Pearson-Stuttard J, Hooton W et al. . Potential of trans fats policies to reduce socioeconomic inequalities in mortality from coronary heart disease in England: cost effectiveness modelling study. BMJ 2015;351:h4583 10.1136/bmj.h4583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Andersen HR, Nielsen TT, Rasmussen K et al. . A comparison of coronary angioplasty with fibrinolytic therapy in acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 2003;349:733–42. 10.1056/NEJMoa025142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nielsen PH, Maeng M, Busk M et al. . Primary angioplasty versus fibrinolysis in acute myocardial infarction: long-term follow-up in the Danish acute myocardial infarction 2 trial. Circulation 2010;121:1484–91. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.873224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Restrepo BJ, Rieger M. Trans fat and cardiovascular disease mortality: evidence from bans in restaurants in New York. J Health Econ 2016;45:176–96 (accessed Feb 2016). 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2015.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.https://matsne.gov.ge/ka/document/view/3071941 (accessed Feb 2016).

- 24.Nichols M, Townsend N, Scarborough P et al. . Cardiovascular disease in Europe 2014: epidemiological update. Eur Heart J 2014;35:2950–9. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barquera S, Pedroza-Tobías A, Medina C et al. . Global overview of the epidemiology of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Arch Med Res 2015;46:32838 10.1016/j.arcmed.2015.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Report from the Commission to the European parliament and the Council regarding trans fats in foods and in the overall diet of the Union population (03–12–2015). http://ec.europa.eu/dgs/health_food-safety/dyna/enews/enews.cfm?al_id=1650 (accessed Feb 2016).