Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the performance of a non-contact infrared thermometer (NCIT) in comparison with digital axillary thermometer (DAT) and infrared tympanic thermometers (ITT) in a population of healthy at term and preterm newborns nursed in incubators.

Setting

1 level III maternity hospital, and its intensive neonatal care unit.

Participants

119 healthy at term newborns and 70 preterm newborns nursed in incubators were consecutively enrolled. Exclusion criteria were unstable/critical conditions, polymalformative congenital syndromes and severe congenital syndromes.

Interventions

Body temperature readings were prospectively collected. Each participant underwent bilateral axillary temperature measurement with DAT, bilateral tympanic measurement with ITT and mid-forehead temperature measurements using NCIT.

Primary outcome measures

Degree of agreement between methods was evaluated by the Bland and Altman method.

Results

714 measurements in 119 healthy at term newborns and 420 measurements in 70 preterm newborns nursed in incubators were performed. Clinical reproducibility of NCIT was 0.0455°C for infants in incubators and 0.0861°C for infants outside an incubator. Bias was 0.029°C for infants in incubators and <0.0001°C for infants outside an incubator. Zero outliers were recorded. The mean difference between methods was good both for newborns at term (0.12°C for NCIT vs DAT and 0.02°C for NCIT vs ITT) and preterm newborns in incubators (0.10°C for NCIT vs DAT and 0.14°C for NCIT vs ITT). Limits of agreement were 0.99 to −0.75 and 0.78 to −0.75 in at term newborns and were particularly satisfactory in preterm newborns in incubators (95% CI: 0.48 to −0.27 and 0.68 to −0.40).

Conclusions

Our results with Bland and Altman analysis demonstrate that NCIT is a very promising tool, especially in preterm newborns nursed in incubators. Trial registration: The study was approved by the Careggi University Hospital Ethics Committee (07/2011).

Keywords: NEONATOLOGY

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Body temperature readings were prospectively collected in healthy at term newborns and in preterm newborns in incubators in one level III hospital and its neonatal intensive care unit. Bilateral axillary temperature measurements with digital axillary thermometer , bilateral tympanic measurements with infrared tympanic thermometers and mid-forehead temperature measurements using non-contact infrared thermometer (NCIT) were performed. NCIT displayed a good clinical reproducibility in a large group of healthy at term newborns and preterm newborns. No outliers were recorded.

Our results demonstrate that NCIT is a very promising tool, especially in preterm newborns nursed in incubators.

The main limitation of the present study is that the majority of the participants were healthy; no child presented febrile infection and critically ill newborns were excluded.

Introduction

One of the most important vital signs in newborns is body temperature. Owing to relatively large body surface area and immature thermoregulatory mechanisms, preterm infants are particularly prone to temperature maintenance problems. As a result, temperature measurements should be performed regularly and should be accurate, reliable and reproducible, considering that maintaining a normal body temperature, ensuring a stable thermal environment and avoiding cold stress represent some of the goals of preterm newborns’ care.1 Moreover, as frequent disturbance of the newborn may lead to hypoxia and deterioration in their clinical condition, minimal handling is fundamental.

No ideal method to measure body temperature in children has been found yet.2–4 An ideal thermometer should: accurately reflect the core body temperature in all age groups; be convenient, easy and comfortable to use; give rapid results; not cause cross infection among patients; not be influenced by room temperature; and be safe and cost-effective.2–4 In practice, every available method has several advantages and disadvantages,4 but none completely fulfils all the aforementioned criteria. In ambulatory and hospital settings, in infants aged less than 4 weeks, axillary measurement of body temperature using a digital thermometer is recommended by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence,3 and by the Italian guidelines.4 This latter method is also recommended for all children if the body temperature has to be measured at home by parents or caregivers.3 4 Owing to the discomfort related to the procedure, the oral and rectal routes should not be routinely used in children aged 0–5 years.3 4 Available studies on the accuracy of tympanic thermometer in children reached contrasting results.5–9 Another disadvantage of this technique is that the ear canal curvature may make it difficult to reach the tympanic membrane.3 4 The presence of hyperaemia or earwax may also interfere with the measurement.3 4 In a study conducted on sick newborns in neonatal units, Uslu et al5 suggested that tympanic thermometer measurement could be used as an acceptable and practical method. On the contrary, Duru et al6 concluded that, though using the tympanic route for measuring temperature in the newborn is relatively safe and non-invasive, the low sensitivity limits its use.

The non-contact infrared thermometer (NCIT) could represent a valid alternative, consisting of a quick and non-invasive method, not requiring sterilisation and not having to be disposable. These reasons make it a candidate for the screening of febrile individuals (such as, eg, international travellers) or for temperature recording in children, particularly in hospital or ambulatory settings,10–12 but some authors found discordant results on the performance of NCITs.13 14 We recently tested this method in a population of 251 children admitted to paediatric emergency departments and paediatric clinics, in which NCITs showed a good performance and proved to be comfortable for children, with the advantage of measuring body temperature in 2 s.15 These characteristics could be useful in newborns, and particularly in preterm newborns nursed in incubators, for the aforementioned reasons. Some authors have evaluated the accuracy of NCITs in this population, with conflicting results.16–20 In the present study, we aimed at comparing a NCIT with two other methods (digital axillary, DAT and infrared tympanic thermometers, ITT), in a population of healthy at term newborns and preterm newborns nursed in incubators at a level III hospital, and in its neonatal intensive care unit.

Methods

This was a single-centre prospective observational study. Healthy at term newborns and preterm newborns who were born in a level III hospital (Careggi University Hospital, Florence, Italy) and nursed in incubators, were consecutively enrolled between January 2013 and January 2014. Exclusion criteria were unstable/critical conditions, polymalformative congenital syndromes and severe congenital syndromes (ie, severe cardiopathies). Body temperature readings were taken from each newborn by two trained and experienced physicians (SS and CF). Bilateral axillary temperature measurements using a DAT, bilateral tympanic temperature measurements using a ITT and two mid-forehead temperature measurements using the NCIT were performed. In the absence of a gold standard method for the measurement of body temperature in newborns, axillary temperature was chosen as a reference, considering its relative precision reported in previous studies and minimal discomfort for the child, according to the most recent American guidelines,21 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence3 and Italian Guidelines.4 For the same reasons, rectal measurement was excluded for its invasiveness and subsequent child's discomfort. In every child, all the measurements were recorded within 6 min. Age and sex of the newborn and incubator temperature were also recorded and entered into a database. Informed consent for the study was obtained from the children's parents/guardians.

Thermometry measurements

Two NCIT, bilateral axillary and bilateral tympanic temperature measurements were performed in every newborn. NCIT measurements were executed in the mid-forehead following the manufacturer's instructions (Thermofocus, model 0800; Tecnimed, Varese, Italy) and according to the American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM 2009) E 1965–1968 standard specifications for infrared thermometers for intermittent determination of patient temperature.22 Axillary temperatures were measured using a digital axillary thermometer (SANITAS Hans Dislage GmbH, Uttenweiler, Germany). The temperature was read 2 min after placement on the newborn's axilla, after the acoustic alert. Tympanic temperatures were recorded with a infrared tympanic thermometer (Braun ThermoScan PRO 4000). All the measurements were performed at stable incubator temperature, and the infrared thermometer was stabilised before measurements. Calibration of every thermometer was checked before and after the study.

Statistical analysis

To assess the variability of repeated measures (reproducibility) of the NCIT, children had duplicate measures of body temperature. Clinical repeatability was calculated as a measure of the reproducibility of two repeated temperature measurements, defined as the SD of the differences between the two sets of measurements (i.e, T2-T1) in all children undergoing the test.23 Age and gestational age were expressed as median and IQR. Normal distribution of variables was tested by one-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Incubator temperature and body temperature were normally distributed. Thus, these results were presented as mean, SDs and 95% CI. To compare body temperatures obtained in each newborn using the three methods, the mean value of the bilateral axillary measurements with the digital axillary thermometer, the mean value of the bilateral tympanic measurements with the ITT and the mean value of the two mid-forehead measurements with the NCIT, were calculated.

Bias (mean of differences) and numbers of outliers (defined as a difference >1°C) were recorded.24 The Bland and Altman 24 method was used to compare two sets of measurements, and the limit of agreement was defined as±2 SDs of the differences, as previously described.25 According to previous studies, mean of difference and limits of agreement were considered a priori good if <0.5°C, and satisfactory if <0.6°C.16 18 Statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS software package (SPSS V.11.5; Chicago, Illinois, USA) and Medcalc 9.2 (MedCalc Software bvba, Mariakerke, Belgium).

Results

Overall, 189 children were enrolled in the study. In particular, 714 measurements in 119 healthy at term newborns and 420 measurements in 70 preterm newborns nursed in incubators were performed. Twenty-eight of 70 (40%) preterm newborns and 64/119 (53%) at term newborns were males. Mean gestational age at birth (median and IQR) was 39 weeks + 6 days (IQR 38 weeks + 3 days—40 weeks + 3 days) for at term newborns and 27 weeks + 3 days (IQR 25 weeks+ 1 day—27 weeks + 5 days) for preterm newborns. The mean incubator temperature was 32.8°C (SD 1.4; median 32.6; IQR 31.9–34.0). The mean room temperature was 27.5°C (SD 1.1; median:27.6; IQR26.8–28.3).

Mean body temperatures obtained by NCIT, DAT and ITT in preterm newborns nursed in incubators were 37.24°C (SD+0.46°C), 37.14°C (SD+0.49°C), 37.10°C (SD+0.51), respectively. Mean body temperatures obtained by NCIT, DAT and ITT in healthy newborns were 36.82°C (SD+0.44°C), 36.40°C (SD+0.42°C), 36.80°C (SD+0.33), respectively.

Clinical repeatability and other reproducibility measures of thermometers in infants inside and outside the incubator

Globally, the clinical reproducibility of NCIT (two measurements on the forehead) was 0.0794°C (0.0455 for infants in incubator and 0.0861 for infants outside the incubator). Bias was 0.047°C (0.029 for infants in incubator and <0.0001 for infants outside the incubator). Zero outliers (defined as a difference >1°C) were recorded.

Reproducibility of tympanic thermometer (dx vs sin) was 0.2931 (0.1800 for infants in incubators and 0.3250 for infants outside the incubator). Bias was 0.348°C (0.233 for infants in incubators and 0.416 for infants outside the incubator). Eight of 188 (4.25%) outliers (defined as a difference >1°C) were recorded (all outside the incubator).

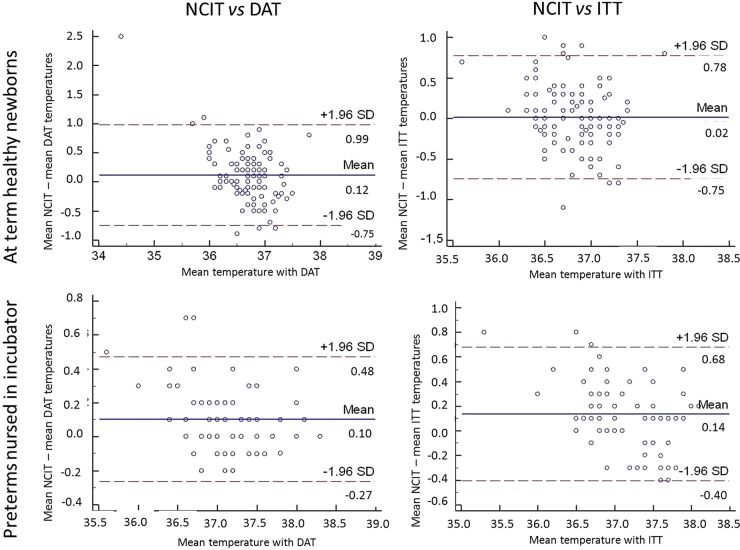

Reproducibility of the axillary electronic thermometer (dx vs sin) was 0.1921 (0.0995 for infants in incubator and 0.2207 for infants outside the incubator). Bias was 0.159°C (0.090 for infants in incubators and 0.200 for infants outside the incubator). Two of 188 (1.06%) outliers (defined as a difference >1°C) were recorded. The correlation between measurements obtained with NCIT and axillary electronic thermometer is reported in figure 1, showing the Bland and Altman diagrams. The mean difference between methods was good both for newborns at term (0.12°C for NCIT vs DAT and 0.02°C for NCIT vs ITT) and preterm newborns in incubators (0.10°C for NCIT vs DAT and 0.14°C for NCIT vs ITT). Limits of agreement were 0.99 to −0.75 for NCIT versus DAT, and 0.78 to −0.75 for NCIT versus ITT for at term newborns and 95% CI 0.48 to −0.27 and 0.68 to −0.40 for preterm newborns in incubators.

Figure 1.

Bland and Altman diagrams comparing mid-forehead temperature recorded by non-contact infrared thermometer (NCIT) and axillary temperature recorded with digital axillary thermometer (DAT); and mid-forehead temperature recorded by NCIT and temperature recorded with infrared tympanic thermometer (ITT) in at term healthy newborns (n=119) and in preterm infants nursed in incubators (n=70).

Discussion and conclusions

Monitoring changes in newborn's body temperature can help prevent harm caused by abnormally high and low body temperatures.1 The infrared forehead thermometer has been reported by some authors to be a simple, non-invasive instrument for measuring temperature accurately in the newborn. De Curtis et al16 found, in a cohort of 107 newborns, that the use of the infrared skin thermometer was associated with low operator-related variability and acceptable limits of agreement with temperature measurements obtained with a rectal mercury thermometer, concluding that the NCIT is a comfortable and reliable way of measuring body temperature in newborns. Duran et al tested NCITs on a cohort of 34 preterm infants with <1500 g birth weight nursed in an incubator, recording temperature from mid-forehead, temporal artery and axilla six times a day for 7 days beginning at the end of the first week of life. Pain assessment was also recorded, using the premature infant pain profile (PIPP). No statistically significant difference was noted between the means of mid-forehead and axillary temperatures. Moreover, the mean PIPP score of axillary temperature measurements was statistically higher than the means of mid-forehead and temporal artery measurements, demonstrating that the infrared skin thermometer applied to the mid-forehead is a useful and valid device for easy and less painful measurement of skin temperature in preterm infants <1500 g.16 In a recently published study conducted on 42 very low birth weight infants, Jarvis et al evaluated the impact on newborn behavioural states and accuracy of three infrared thermometers compared with DATs. One hundred measurements were collected from each device. Temperature measurements taken with infrared thermometers demonstrated less disruption to preterm infants’ behavioural state, however, accuracy of the devices varied: only one infrared device showed satisfactory agreement (bias −0.071; 95% CI −0.68 to 0.54).18

In our study, NCIT displayed good clinical reproducibility in a large group of healthy at term and preterm newborns. No outliers were recorded. Mean of differences were good in all the newborns and limits of agreement were satisfactory in preterm newborns nursed in incubators, suggesting a good performance of NCITs in this particular subpopulation. The finding of wider limits of agreement in at term newborns might be influenced by external factors and further studies are needed in this regard. The main limitation of the present study is that the majority of the participants were healthy, no child presented febrile infection, and critically ill newborns were excluded. In conclusion, the NCIT is a promising, quick, non-invasive and accurate method to measure body temperature in newborns, particularly in preterm infants nursed in incubators.

Footnotes

Contributors: EC, SS, EB, CF and CD contributed to the conception and design of the work. SS, EB and CF contributed to the acquisition of data. EC, SS and EB performed the analyses and interpretation of data, and drafted the work. LG, MdM and CD revised the work and gave the final approval for publication.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Careggi University Hospital Ethics Committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Lyon AJ, Freer Y. Goals and options in keeping preterm babies warm. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2011;96:F71–4. 10.1136/adc.2009.161158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.El-Radhi AS. Determining fever in children: the search for an ideal thermometer. Br J Nurs 2014;23:91–4. 10.12968/bjon.2014.23.2.91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (2013) NICE Clinical Guideline. Feverish illness in children: assessment and initial management in children younger than 5 years. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg160 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Chiappini E, Venturini E, Principi N et al. , Writing Committee of the Italian Pediatric Society Panel for the Management of Fever in Children. Update of the 2009 Italian Pediatric Society Guidelines about management of fever in children. Clin Ther 2012;34:1648–53. 10.1016/j.clinthera.2012.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Uslu S, Ozdemir H, Bulbul A et al. . A comparison of different methods of temperature measurements in sick newborns. J Trop Pediatr 2011;57:418–23. 10.1093/tropej/fmq120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duru CO, Akinbami FO, Orimadegun AE. A comparison of tympanic and rectal temperatures in term Nigerian neonates. BMC Pediatr 2012;12:86 10.1186/1471-2431-12-86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dodd SR, Lancaster GA, Craig JV et al. . In a systematic review, infrared ear thermometry for fever diagnosis in children finds poor sensitivity. J Clin Epidemiol 2006;59:354–7. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Apa H, Gözmen S, Bayram N et al. . Clinical accuracy of tympanic thermometer and noncontact infrared skin thermometer in pediatric practice: an alternative for axillary digital thermometer. Pediatr Emerg Care 2013;29:992–7. 10.1097/PEC.0b013e3182a2d419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhen C, Xia Z, Long L et al. . Accuracy of infrared ear thermometry in children: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2014;53:1158–65. 10.1177/0009922814536774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mounier-Jack S, Jas R, Coker R. Progress and shortcomings in European national strategic plans for pandemic influenza. Bull World Health Organ 2007;85:923–9. 10.2471/BLT.06.039834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Osio CE, Carnelli V. Comparative study of body temperature measured with a non-contact infrared thermometer versus conventional devices. The first Italian study on 90 pediatric patients. Minerva Pediatr 2007;59:327–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Teran CG, Torrez-Llanos J, Teran-Miranda TE et al. . Clinical accuracy of a non-contact infrared skin thermometer in paediatric practice. Child Care Health Dev 2012;38:471–6. 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2011.01264.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Teller J, Ragazzi M, Simonetti GD et al. . Accuracy of tympanic and forehead thermometers in private paediatric practice. Acta Paediatr 2014;103:e80–3. 10.1111/apa.12464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Trevisanuto D, Martellan B, Zanconato S et al. . Accuracy of infrared skin thermometers in children. Arch Dis Child 2011;96:785–6. 10.1136/adc.2011.213330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chiappini E, Sollai S, Longhi R et al. . Performance of non-contact infrared thermometer for detecting febrile children in hospital and ambulatory settings. J Clin Nurs 2011;20:1311–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Curtis M, Calzolari F, Marciano A et al. . Comparison between rectal and infrared skin temperature in the newborn. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2008;93:F55–7. 10.1136/adc.2006.114314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Duran R, Vatansever U, Acunas B et al. . Comparison of temporal artery, mid-forehead skin and axillary temperature recordings in preterm infants<1500 g of birthweight. J Paediatr Child Health 2009;45:444–7. 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2009.01526.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jarvis M, Guy KJ, König K. Accuracy of infrared thermometers in very low birth weight infants and impact on newborn behavioural states. J Paediatr Child Health 2013;49:471–4. 10.1111/jpc.12207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sethi A, Patel D, Nimbalkar A et al. . Comparison of forehead infrared thermometry with axillary digital thermometry in neonates. Indian Pediatr 2013;50:1153–4. 10.1007/s13312-013-0302-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robertson-Smith J, McCaffrey FT, Sayers R et al. . A comparison of mid-forehead and axillary temperatures in newborn intensive care. J Perinatol 2015;35:120–2. 10.1038/jp.2014.148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sullivan JE, Farrar HC, Section on Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics, Committee on Drugs. Fever and antipyretic use in children. Pediatrics 2011;127:580–7. 10.1542/peds.2010-3852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM) International. Standard specification for infrared thermometers for intermittent determination of patient temperature, 1998–2009. http://www.astm.org

- 23.Chamberlain JM, Terndrup TE, Alexander DT et al. . Determination of normal ear temperature with an infrared emission detection thermometer. Ann Emerg Med 1995;25:15–20. 10.1016/S0196-0644(95)70349-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet 1986;327:307–10. 10.1016/S0140-6736(86)90837-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Giavarina D. Understanding Bland Altman analysis. Biochem Med (Zagreb) 2015;25:141–51. 10.11613/BM.2015.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]