Abstract

A 57-year-old man with iron deficiency anaemia developed general malaise, exertional dyspnoea and features of cardiac failure out of proportion to his anaemia (haemoglobin 120 g/L). Investigations showed a severely dilated left ventricle with an ejection fraction of 15%, due to dilated cardiomyopathy. He was treated with high-dose diuretics, ACE inhibitors and β-blocker therapy. Subsequent investigation into his iron deficiency anaemia revealed a new diagnosis of coeliac disease. After starting a gluten-free diet, his cardiac function improved markedly, with ejection fraction reaching 70%, allowing his cardiac medications to be withdrawn. This case suggests a link between coeliac disease and cardiomyopathy.

Background

Coeliac disease is an autoimmune condition in which gluten damages the small intestinal mucosa and causes chronic malabsorption. It affects approximately 1 in 100 people in the UK,1 2 but many individuals have no symptoms and remain undiagnosed. Coeliac disease classically presents with diarrhoea, weight loss and general malaise. However, it can manifest itself without gastrointestinal symptoms but with dermatitis herpetiformis or iron deficiency anaemia. More atypical presentations of coeliac disease include osteoporosis, infertility, abnormal liver biochemistry and neurological symptoms, again often in the absence of gastrointestinal symptoms.3 Links between cardiac disease and coeliac disease are not widely recognised. There are conflicting data regarding a link between coeliac disease and cardiovascular disease in general.4–7 With regard to cardiomyopathy, it is unclear whether there is an association between coeliac disease in patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. This article presents a case that explores the link between the two diseases.

Case presentation

A 57-year-old man was referred to the gastroenterology clinic for the investigation of his anaemia (haemoglobin 115–125 g/L with mean corpuscular volume (MCV) 70–75 fL). He had a 1-month history of general malaise and loss of appetite, and had recently experienced worsening dyspnoea. He had no gastrointestinal symptoms. He had no significant medical history, was on no medication, drank no alcohol and was a non-smoker. On examination, he looked unwell and was breathless on minimal exertion. His heart rate was 100/min. He had a systolic murmur, a markedly raised jugular venous pressure and gross pitting oedema in his lower limbs. His abdomen was mildly distended. No other abnormalities were found.

Initial investigations confirmed mild iron deficiency anaemia: haemoglobin 121 g/L, MCV 74 fL and ferritin 19 ng/mL (normal range 22–275). White cell and platelet counts were normal. Renal, liver and thyroid function tests were all normal. Chest X-ray showed cardiomegaly. An ECG showed sinus tachycardia of 106/min, left axis deviation ST segment depression and T wave inversions, in leads V5 and V6. The patient was hospitalised with a working diagnosis of heart failure.

Echocardiogram (video 1) showed severe biventricular impairment, with a left ventricular ejection fraction of approximately 15%. The patient also had mild mitral regurgitation, moderate tricuspid regurgitation and a left ventricular diameter of 6 cm. There was mild hepatomegaly on ultrasonography of his abdomen. He was started on ramipril, spironolactone, furosemide and bisoprolol in addition to oral iron supplements to correct his anaemia. Coronary angiography showed normal coronary arteries. Since he had runs of non-sustained ventricular tachycardia, an implantable cardioverter defibrillator was fitted. The final diagnosis was dilated cardiomyopathy. Although there had been no overt prior infective illness, viral myocarditis was considered as a possible cause.

Video 1.

Apical four-chamber ECG at presentation showing an ejection fraction of approximately 15%.

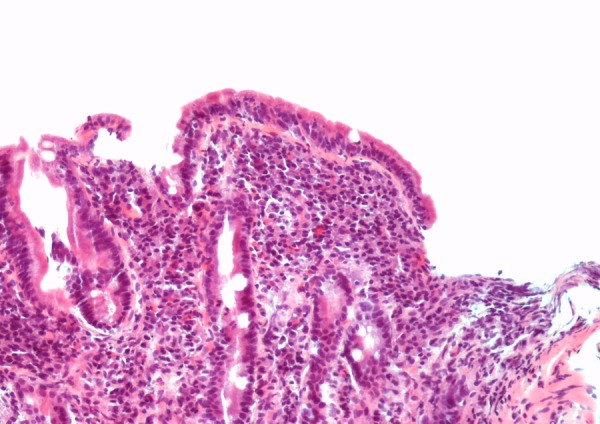

Once the patient's cardiac status stabilised, he was discharged and underwent outpatient gastroenterological investigation into his iron deficiency anaemia. Standard gastrointestinal investigation of iron deficiency anaemia in the absence of overt bleeding or abdominal symptoms includes a search for bleeding from occult upper gastrointestinal cancer or ulceration by gastroscopy, a search for bleeding from an occult proximal colonic cancer by colonoscopy or CT scanning and testing for coeliac disease as a cause of iron malabsorption. This patient continued to deny any gastrointestinal symptoms. A ‘long prep’ abdominal CT scan to image the colon showed no colonic pathology. Tissue transglutaminase antibody was strongly positive at 132 (normal range <10). Subsequent duodenal biopsies taken at an otherwise normal upper gastrointestinal endoscopy confirmed features of coeliac disease, with subtotal villous atrophy and intraepithelial lymphocytosis (figure 1). The patient started a gluten-free diet.

Figure 1.

Distal duodenal biopsy showing villous blunting with an increase in intraepithelial lymphocytes and a significant lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate within the lamina propria (H&E stain, ×20).

Two months after starting the gluten-free diet, he had improved dramatically, with resolution of his dyspnoea and no evidence of any peripheral oedema. A repeat echocardiogram, 18 months after his admission with heart failure, showed that the left ventricle was a normal size with an ejection fraction of 63%, and there was mild aortic and mitral regurgitation. Consequently, the patient's spironolactone and furosemide doses were reduced and stopped completely. A third echocardiogram performed 2 years after his initial admission with heart failure showed that his left ventricular function continued to improve and the ejection fraction had increased to 70% (video 2). More than 2 years after coeliac disease was diagnosed, he remains well without any dyspnoea. He has been mostly compliant with his gluten-free diet but admits to lapses in his dietary adherence. Since being on a gluten-free diet, his haemoglobin has remained greater than 130 g/L, while remaining off iron tablets. Yearly measurement of his tissue transglutaminase antibody concentration shows a marked improvement, but it remains weakly positive at 22, consistent with his dietary lapses.

Video 2.

Apical four-chamber view echocardiogram 2 years after presentation and while following a gluten-free diet. The ejection fraction is approximately 70%.

Differential diagnosis

Differential diagnosis of dilated cardiomyopathy:

Ischaemic heart disease

Valvular heart disease

Hypertension

Inherited (genetic)

Viral myocarditis,

Chagas disease

Alcohol excess

Drugs (eg, doxorubicin) and toxins (heavy metals)

Pregnancy

Metabolic (thyroid disease, vitamin B deficiency, diabetes, haemochromatosis).

Muscular dystrophy

Idiopathic

Discussion

Dilated cardiomyopathy may be due to valvular heart disease, ischaemic heart disease, hypertension or a genetic predisposition. Other causes include viral myocarditis, alcohol excess, drugs, autoimmune disease, pregnancy and metabolic problems including thyroid disease, vitamin B deficiency and haemochromatosis. However, in a large proportion of dilated cardiomyopathies, the cause is unknown.

Our patient's cardiomyopathy improved markedly over time. Although it is difficult to discount the possibility that he had a viral myocarditis, he did not seem to have one of the reversible aetiologies. What is clear is that the improved cardiac function coincided with him starting a gluten-free diet. This would suggest that there is a link between coeliac disease and dilated cardiomyopathy.

There have been other case reports of a possible link between coeliac disease and idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy.8–13 However, there have been few attempts to systematically study such a link. Some studies have searched for coeliac disease in cohorts of patients with dilated cardiomyopathy and reported the prevalence of coeliac to be higher than would be expected in the general population.14 15 However, other studies of dilated cardiomyopathy patients have not found any increased prevalence of coeliac disease.16

More systematic studies have addressed the link between cardiomyopathy and coeliac disease from the other direction: a large Swedish study of children and adults with coeliac disease found no subsequent increased risk of later myocarditis, cardiomyopathy or pericarditis, compared to controls.17 In a subsequent nationwide Swedish study, 29 000 patients with coeliac disease were followed up for the subsequent development of dilated cardiomyopathy. Compared to controls, coeliac patients had a slightly increased risk of developing dilated cardiomyopathy that fell just short of statistical significance.18 The most plausible explanation for any link between coeliac disease and dilated cardiomyopathy is that both conditions might be mediated through inflammation and autoimmune mechanisms.

Curione et al19 explored the effects of a gluten-free diet on three people with coeliac disease and idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Two of these case studies who adhered to a gluten-free diet showed an improvement in cardiac function over a 29-month period. It was hypothesised that the gluten-free diet supressed auto-immune function and thus allowed cardiac function to improve. If there is an increased prevalence of coeliac disease in idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy, it is possible that a gluten-free diet could benefit this population.

In summary, this case report of a patient with both coeliac disease and dilated cardiomyopathy, whose cardiac function improved dramatically with a gluten-free diet, supports an as yet unproven link between the two conditions.

Learning points.

Coeliac disease is a common autoimmune disease that causes chronic malabsorption and is primarily treated with a lifelong gluten-free diet.

In many cases of dilated cardiomyopathy, the cause is unknown.

There may be a link between coeliac disease and cardiomyopathy.

Testing for coeliac disease should be considered in unexplained dilated cardiomyopathy.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Fasano A, Catassi C. Clinical practice. Celiac disease. N Engl J Med 2012;367:2419–26. 10.1056/NEJMcp1113994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ludvigsson JF, Bai JC, Biagi F et al. . Diagnosis and management of adult coeliac disease: guidelines from the British Society of Gastroenterology. Gut 2014;63:1210–28. 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-306578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Green PH. The many faces of celiac disease: clinical presentation of celiac disease in the adult population. Gastroenterology 2005;128(4, Suppl 1):S74–8. 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.02.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wei L, Spiers E, Reynolds N et al. . Association between coeliac disease and cardiovascular disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2008;27:514–19. 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03594.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.West J, Logan RF, Card TR et al. . Risk of vascular disease in adults with diagnosed coeliac disease: a population-based study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2004;20:73–9. 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.02008.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ludvigsson JF, James S, Askling J et al. . Nationwide cohort study of risk of ischemic heart disease in patients with celiac disease. Circulation 2011;123:483–90. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.965624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Emilsson L, Lebwohl B, Sundström J et al. . Cardiovascular disease in patients with coeliac disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Dig Liver Dis 2015;47:847–52. 10.1016/j.dld.2015.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barrio JP, Cura G, Ramallo G et al. . Heart transplantation in rapidly progressive end-stage heart failure associated with celiac disease. BMJ Case Rep 2011;2011:pii: bcr1220103624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boskovic A, Kitic I, Prokic D et al. . Cardiomyopathy associated with celiac disease in childhood. Case Rep Gastroint Med 2012;2012:170760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Milisavljević N, Cvetković M, Nikolić G et al. . Dilated cardiomyopathy associated with celiac disease: case report and literature review. Srp Arh Celok Lek 2012;140:641–3. 10.2298/SARH1210641M [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goel NK, McBane RD, Kamath PS. Cardiomyopathy associated with celiac disease. Mayo Clin Proc 2005;80:674–6. 10.4065/80.5.674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Romagnoli E, Boldrini E, Pietrangelo A. Association between celiac disease and idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy: a case report. Intern Emerg Med 2011;6:125–8. 10.1007/s11739-010-0442-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lodha A, Haran M, Hollander G et al. . Celiac disease associated with dilated cardiomyopathy. South Med J 2009;102:1052–4. 10.1097/SMJ.0b013e3181b64dd9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Bem RS, Da Ro Sa Utiyama SR, Nisihara RM et al. . Celiac disease prevalence in Brazilian dilated cardiomyopathy patients. Dig Dis Sci 2006;51:1016–19. 10.1007/s10620-006-9337-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Not T, Faleschini E, Tommasini A et al. . Celiac disease in patients with sporadic and inherited cardiomyopathies and in their relatives. Eur Heart J 2003;24:1455–61. 10.1016/S0195-668X(03)00310-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vizzardi E, Lanzarotto F, Carabellese N et al. . Lack of association of coeliac disease with idiopathic and ischaemic dilated cardiomyopathies. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 2008;68:692–5. 10.1080/00365510802085370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elfström P, Hamsten A, Montgomery SM et al. . Cardiomyopathy, pericarditis and myocarditis in a population based cohort of inpatients with coeliac disease. J Intern Med 2007;262:545–54. 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2007.01843.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Emilsson L, Andersson B, Elfström P et al. . Risk of idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy in 29 000 patients with celiac disease. J Am Heart Assoc 2012;1:e001594 10.1161/JAHA.112.001594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Curione M, Barbato M, Viola F et al. . Idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy associated with coeliac disease: the effect of a gluten-free diet on cardiac performance. Dig Liver Dis 2002;34:866–9. 10.1016/S1590-8658(02)80258-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]