Abstract

A 55-year-old non-diabetic, normotensive man presented with dull aching pain in the left upper abdomen of 2-year duration. He had no significant medical, surgical or family history. Relevant blood tests and chest skiagram were normal. 24 h urinary vanillylmandelic acid levels and serum electrolyte levels were normal. Ultrasonogram and CT findings were suggestive of a 15×11 cm giant left adrenal myelolipoma. A left adrenalectomy was performed using a laparoscopic transperitoneal approach employing three ports. Pneumoperitoneum was achieved by this closed method. After successful excision, the internal contents were suctioned and the capsule was retrieved through a 2.5 cm incision. The operating time was 210 min and total blood loss 50–60 mL; no blood transfusions were needed. The patient was discharged on the third postoperative day. Histopathology confirmed an adrenal myelolipoma. The cited case is of the largest adrenal myelolipoma resected entirely using a laparoscopic approach.

Background

Adrenal myelolipomas are rare tumours with an estimated incidence of 0.1%. Giant myelolipomas exceeding 10 cm are rarer yet. Such lesions are prone to spontaneous rupture and their surgical excision is indicated. There are several case reports describing the excision of such large size tumours using an open approach.

As per the Cochrane database, the cited case is the largest adrenal myelolipoma resected entirely through a laparoscopic approach. We wish to highlight that, with sufficient expertise, it may be possible to deal with giant adrenal myelolipomas employing a laparoscopic approach.

Case presentation

A 55-year-old man presented with dull aching pain in the left upper quadrant of the abdomen of 2-year duration. He had no history of bowel or bladder disturbance nor of weight loss. He had no significant medical or family history. There was no history of any surgical intervention. He was non-diabetic and normotensive. Physical examination was unremarkable.

Investigations

Relevant blood tests and chest X-ray were normal. Twenty-four-hour urinary vanillylmandelic acid levels and serum electrolyte levels were normal.

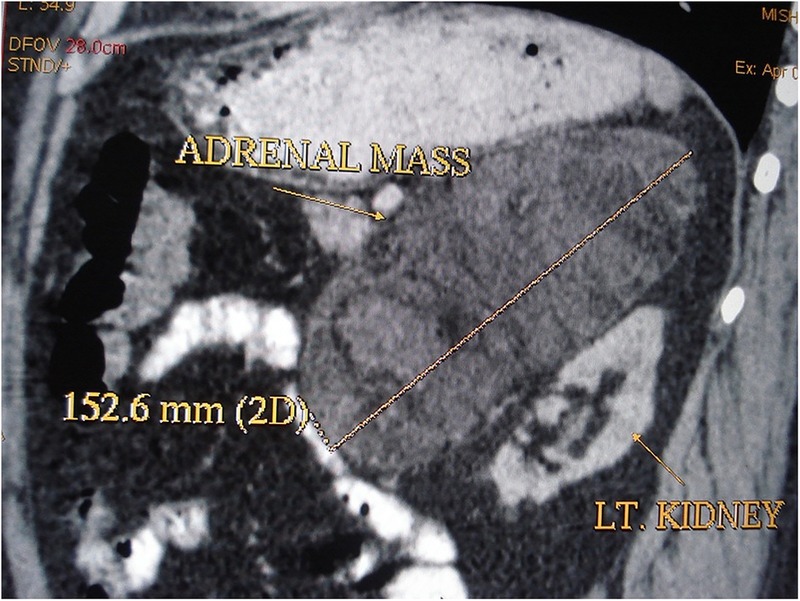

Ultrasonogram revealed a large (15×10 cm) hyperechoic left adrenal mass. CT revealed a 15×11 cm hypoechoic minimally enhancing lesion of mixed density (figure 1). A large amount of fat was seen interspersed with higher attenuation myeloid tissue. The attenuation values ranged from 60 to 20 Hounsfield units, reflecting a mixture of adipose and myeloid elements. An intact capsule having a well-defined plane with surrounding organs was seen. No calcification was seen, ruling out any episode of previous intratumoural haemorrhage. The left kidney was pushed down by the tumour.

Figure 1.

Contrast-enhanced CT image showing the left adrenal mass.

Differential diagnosis

Adrenal lipomas, teratomas, angiomyolipomas, metastases and well-differentiated liposarcomas.

Treatment

We decided to perform a left adrenalectomy using a laparoscopic transperitoneal approach after obtaining informed written consent from the patient. Preoperatively, mechanical bowel preparation was carried out by administration of Peglec.

One milligram of midazolam and 0.2 mg of glycopyrrolate were administered for premedication. Thereafter, the patient was subjected to general anaesthesia by orotracheal intubation, and a nasogastric tube and urethral catheter were inserted.

The patient was placed in a right lateral position. Pneumoperitoneum was achieved using the closed method. We employed three ports. The first was a 10 mm optical port inserted at the lateral border of the left rectus abdominis about 2 cm above the umbilicus. Two accessory ports were inserted for hand instruments, on the left was a 5 mm port just below the costal margin in the line of the camera port, and on the right was a 10 mm port in the mid-clavicular line at the spinoumbilical line (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Postoperative picture showing sites of port placement and specimen retrieval.

The descending colon was mobilised and lienorenal and splenocolic ligaments were divided. The adrenal gland was mobilised on all sides, except laterally, with the help of a harmonic scalpel. The adrenal vein was ligated by LT-300 titanium clips, two clips were applied on the side of the renal vein and one clip was placed on the gland’s side; the adrenal vein was divided by scissors between these clips. After lateral mobilisation, the adrenal mass was dissected off the kidney. Thereafter, the soft tissue contents were aspirated using a suction cannula, leaving behind only the capsule. This was delivered by a 2.5 cm oblique incision in the anterior axillary line at the level of the umbilicus (figure 2). The specimen measured 15 cm at its longest dimension (figure 3). No drains were kept.

Figure 3.

Retrieved specimen.

The operating time was 210 min and total blood loss 50–60 mL; no blood transfusions were needed.

Outcome and follow-up

Postoperatively, the per urethral catheter was removed and the patient ambulated on the morning after surgery. Orally, liquids were started on the same day. In total, 100 mg of tramadol as analgaesic were needed only on the day of surgery and for the first two postoperative days.

The patient was discharged on the third postoperative day.

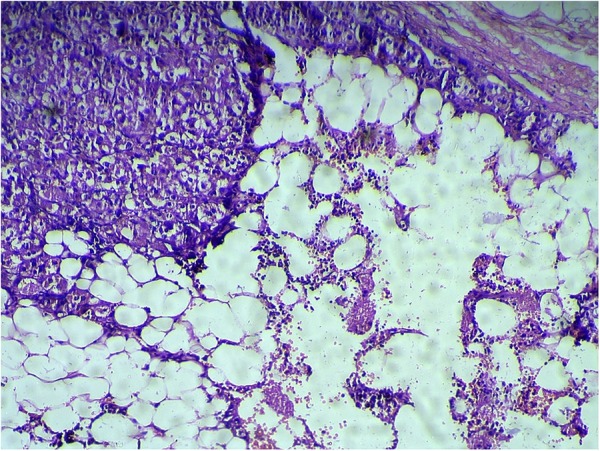

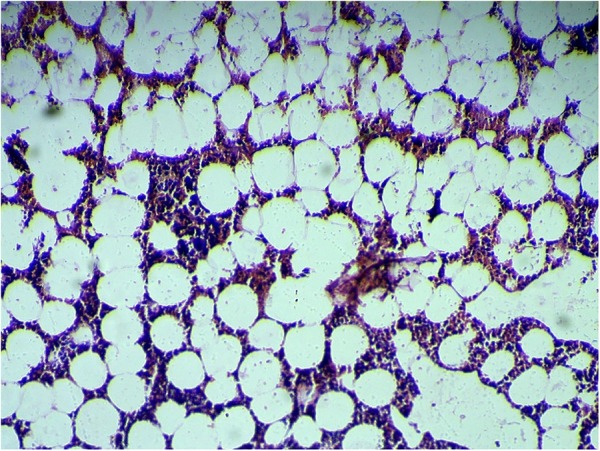

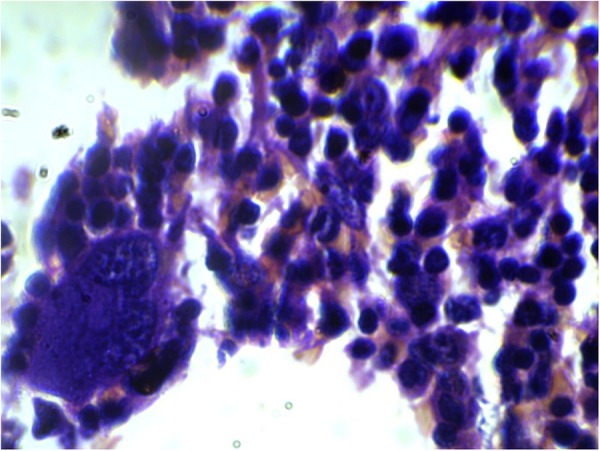

Histopathology (figures 4–6) showed a mixture of normal adrenal tissue, fat and a full trilineage maturation of the three major blood-forming elements: myeloid (white cell forming), erythroid (red blood cell forming) and megakaryocytic (platelet forming) lines confirming a diagnosis of myelolipoma.

Figure 4.

Myelolipoma with normal adrenal gland.

Figure 5.

Myeloid elements showing ×10 magnification.

Figure 6.

Myeloid elements with megakaryocytes showing ×10 magnification.

Discussion

Myelolipomas are rare tumours with an estimated incidence of <1 in a 1000. They are benign and do not produce any hormones. There is no gender or site predilection.

About 15% of myelolipomas are found outside the adrenal gland and the majority of these (50%) arise from the presacral area. Apart from this, myelolipoma has been reported in thoracic, retroperitoneal, pelvic, renal, hepatic and osseous locations.1

Apparently, myelolipomas are a result of clonal stem cell proliferation. As the name suggests, these tumours comprise of mature adipose tissue and bone marrow along with all three lineages of haematopoietic elements. However, the haematopoietic cells within these lesions are not released into the circulation and, with ageing, the cellularity in the bone marrow component does not decrease.2

Myelolipomas may result from an adrenal stress response as, in rats, it has been observed that these tumours are induced after injection with adrenocorticotropic hormone and necrotic tumour tissues.3

A large variability in the size of these tumours has been reported and, occasionally, they may be larger than 10 cm. In a series of 21 cases, the average size reported was 21 cm. Being retroperitoneal, these lesions do not cause any symptoms, but when they achieve a large size, some patients may report of a dull nagging pain in the flanks or abdomen.4 As they increase in size, these tumours, rarely, may rupture spontaneously. However, this is seen in myelolipomas larger than 10 cm (ranging from 6.3 to 14.7 cm).5

Although myelolipomas do not classically produce any hormones, they may coexist with a metabolically active adrenal adenoma, usually producing excess cortisol.6

Cross-sectional imaging is fairly accurate in the diagnosis of myelolipomas. On CT scan, these lesions are well circumscribed, encompassing low-density fat along with higher density marrow. Adrenal calcifications are seen in more than 25% cases and a significant proportion have haemorrhagic areas.7 MRI is highly sensitive in identifying macroscopic fatty tissue components in an adrenal mass, which is pathognomonic of a myelolipoma.8 However, very rarely, macroscopic fat on imaging has been seen in adrenal lipomas, teratomas, angiomyolipomas, metastases and liposarcomas.9

The National Institutes of Health Consensus Panel on adrenal incidentaloma has recommended that a myelolipoma can be exempted from the metabolic work up considered essential for a newly diagnosed adrenal mass, which in this case should be considered only if there is a high index of suspicion for a concomitant metabolically active tumour.10

Surgery is recommended for symptomatic myelolipomas.11 Asymptomatic tumours are usually treated conservatively with serial evaluations by ultrasonography or axial imaging.

Previously, it was thought to be a contraindication for laparoscopic approach when the adrenal tumour size exceeded 5–6 cm. But several recent studies have shown that a laparoscopic approach can be extended for larger size adrenal tumours.12

An extensive search of the current literature made us believe that this is perhaps the largest adrenal myelolipoma that has been resected by the laparoscopic approach.

Learning points.

Myelolipomas are rare, benign, metabolically silent lesions with an estimated incidence of <0.1%.

Spontaneous rupture of myelolipomas is a rare event, the mean tumour size of myelolipomas that have ruptured exceeds 10 cm.

Contrary to the conventional notion that a laparoscopic approach is contraindicated for an adrenal tumour exceeding 5–6 cm, several recent studies have shown that a laparoscopic approach can be extended for larger size adrenal tumours.

Footnotes

Contributors: RC and AD operated on the patient and prepared the manuscript. KS and RB helped in preparing the manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Wagner JR, Kleiner DE, Walther MM et al. . Perirenal myelolipoma. Urology 1997;49:128–30. 10.1016/S0090-4295(97)00368-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bishop E, Eble JN, Cheng Liang et al. . Adrenal myelolipomas show nonrandom X-chromosome inactivation in hematopoietic elements and fat: support for a clonal origin of myelolipomas. Am J Surg Pathol 2006;30:838–43. 10.1097/01.pas.0000202044.05333.17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Selye H, Stone H. Hormonally induced transformation of adrenal into myeloid tissue. Am J Pathol 1950;26:211–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Han M, Burnett AL, Fishman EK et al. . The natural history and treatment of adrenal myelolipoma. J Urol 1997;157:1213–16. 10.1016/S0022-5347(01)64926-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Russell C, Goodacre BW, van Sonnenberg E et al. . Spontaneous rupture of adrenal myelolipoma: spiral CT appearance. Abdom Imaging 2000;25:431–4. 10.1007/s002610000061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hisamatsu H, Sakai H, Tsuda S et al. . Combined adrenal adenoma and myelolipoma in a patient with Cushing's syndrome: case report and review of the literature. Int J Urol 2004;11:416–18. 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2004.00815.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kenney PJ, Wagner BJ, Rao P et al. . Myelolipoma: CT and pathologic features. Radiology 1998;208:87–95. 10.1148/radiology.208.1.9646797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cyran KM, Kenney PJ, Memel DS et al. . Adrenal myelolipoma. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1996;166:395–400. 10.2214/ajr.166.2.8553954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lam KY, Lo CY. Adrenal lipomatous tumours: a 30 year clinicopathological experience at a single institution. J Clin Pathol 2001;54:707–12. 10.1136/jcp.54.9.707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grumbach MM, Biller BMK, Braunstein GD et al. . Management of the clinically inapparent adrenal mass (“incidentaloma”). Ann Intern Med 2003;138:424–9. 10.7326/0003-4819-138-5-200303040-00013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schaeffer EM, Kavoussi LR. Adrenal myelolipoma. J Urol 2005;173:1760 10.1097/01.ju.0000160080.20391.c6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.MacGillivray DC, Scichman SJ, Ferrer FA et al. . A comparison of open vs laparoscopic adrenalectomy. Surg Endosc 1996;10:987–90. 10.1007/s004649900220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]