Abstract

Although recollapse after percutaneous vertebroplasty (PV) is a serious complication that needs salvage surgery, there is no consensus regarding the best operative treatment for this failure. We present cases of 3 patients, diagnosed as having thoracic osteoporotic vertebral fractures, who had undergone PV at other institutes. Within less than half a year, recollapse occurred at the cemented vertebrae in all 3 patients, and we conducted anterior spinal fixation (ASF) on them. In all cases, ASF relieved the patient's severe low back pain, and there was no recurrence of symptoms during the follow-up period of 6 years, on average. ASF is the optimal salvage procedure, since it allows for the direct decompression of nerve tissue with reconstruction of the collapsed spinal column, and preservation of the ligaments and muscles that stabilise the posterior spine. Surgeons who perform PV need to be able to assess this failure early and to perform spinal fixation.

Background

Osteoporotic vertebral fractures (OVFs) are highly prevalent in today’s progressively ageing society, and are especially prevalent in elderly women. OVFs cause severe pain and spinal instability, and are devastating to the patient’s quality of life.1 Percutaneous vertebroplasty (PV), first described by Galibert et al,2 has been widely used to treat OVFs in recent years. PV is a minimally invasive therapeutic procedure in which a bone cement, generally polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA), is injected percutaneously into the vertebral body via the pedicle. This procedure immediately strengthens and stabilises the OVF, and successfully reduces the pain in 80–90% of patients.3

Despite its positive clinical outcome, PV is associated with various complications, including local infection and pyogenic spondylitis, symptomatic cement leakage, pulmonary embolism, cement fragmentation, adjacent vertebral fracture and refracture of cemented vertebrae.4–9 In particular, late collapse of the cemented vertebrae is a devastating complication, because it usually requires additional invasive salvage treatment as the result of progressive local kyphotic deformity and spinal cord compression. The incidence of recollapse is 1.54–3.21%,10 11 and, due to its rarity, there is no consensus regarding the best treatment for PV failure with this complication.12 13 In some cases, repeating the PV effectively relieves the patient’s pain.14–16 However, most surgeons argue that a failed PV requires salvage by spinal fixation.12 13 To date, there are only a few studies on anterior spinal fixation (ASF) as a treatment for failed PV, and its long-term clinical outcomes are lacking.12 13 17

Therefore, we report three cases in which patients were referred to us with recollapse of the cemented vertebral body after PV. These patients underwent revision surgery with ASF at our institute. In all three cases, ASF relieved the patient’s severe low back pain, and there was no recurrence of symptoms during the follow-up period (6 years on average). The patients were informed that data from the cases would be submitted for publication, and gave their consent.

Case presentation

Case 1

An 87-year-old woman with a symptomatic T12 osteoporotic compression fracture was treated at another hospital by PV with PMMA and a laminectomy at the same level (figure 1A, B). According to the surgeon, he did not perform spinal fixation after laminectomy because the patient was geriatric. The patient’s back pain was relieved immediately after PV, but recurred 2 months later without any traumatic episode. The patient was unable to walk due to intense low back pain, and she was referred to our hospital. Physical examination showed no muscle weakness and intact deep tendon reflexes in both legs. Radiographs showed a local kyphotic deformity (Cobb angle 30°) (figure 1C, D). CT scans revealed air collection around the PMMA and PMMA fragmentation in the vertebra (figure 2A, B). MRI showed compressed spinal cord by the disrupted posterior wall of the T12 vertebra (figure 2C, D).

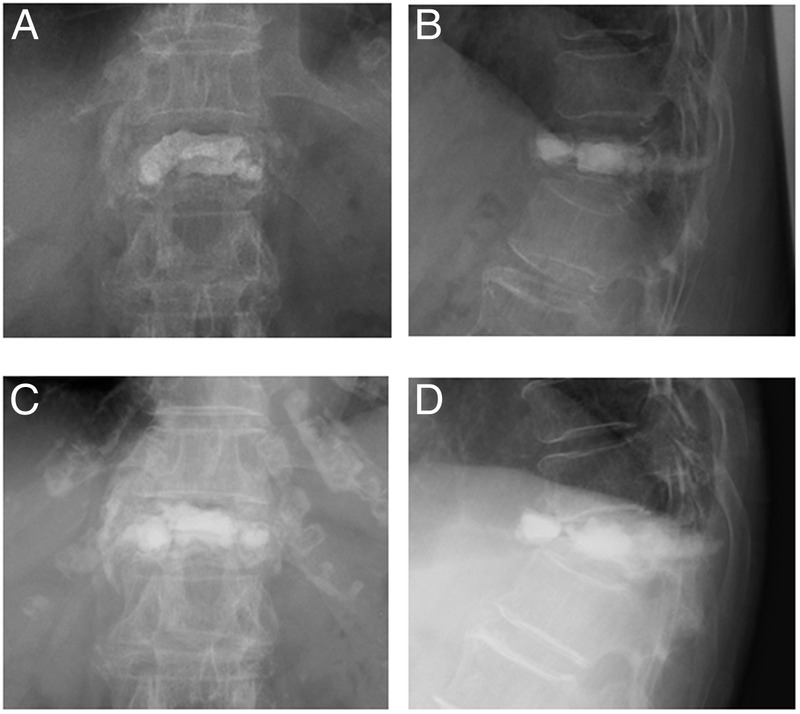

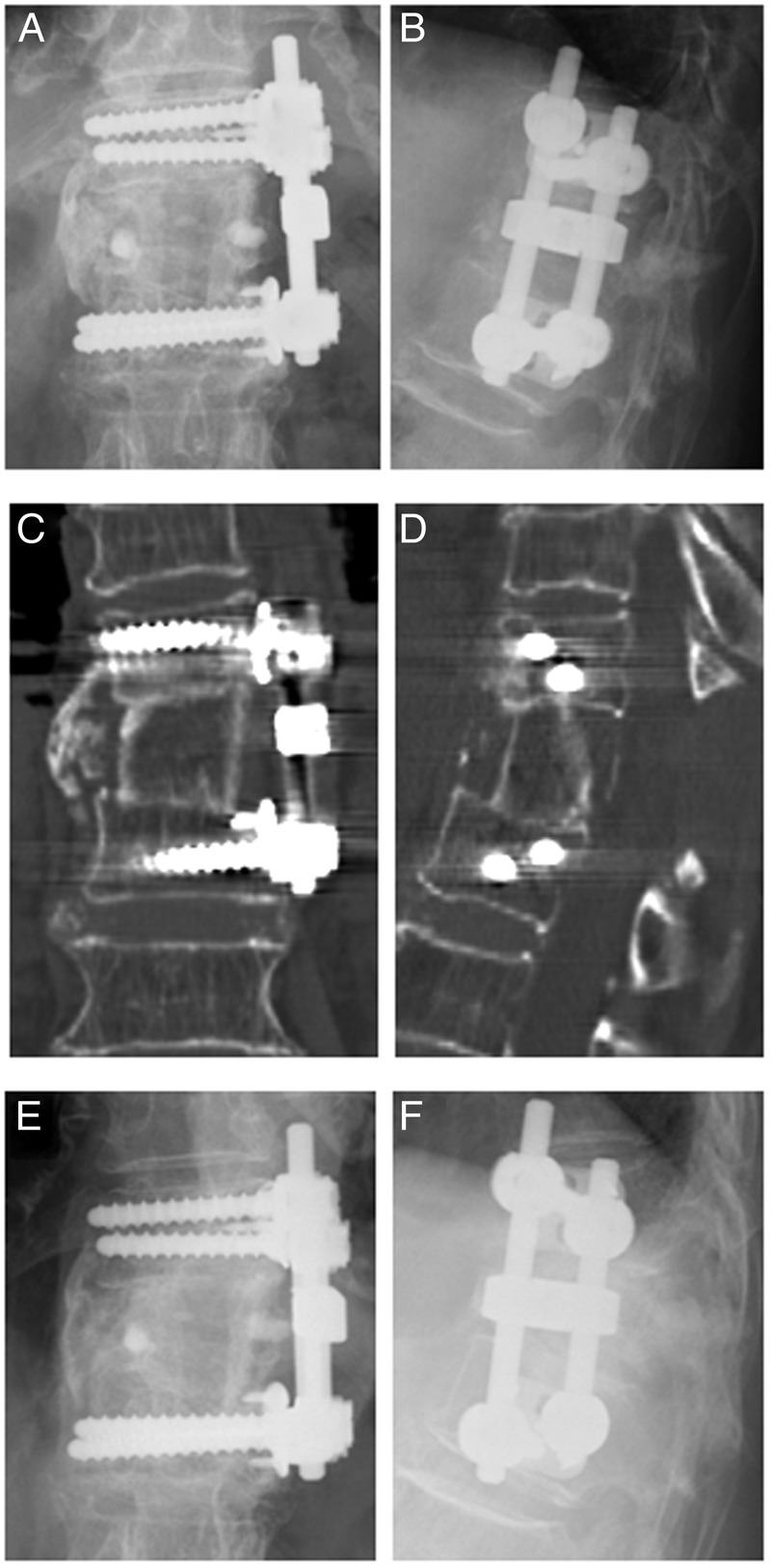

Figure 1.

Case 1: An 87-year-old woman with a postpercutaneous vertebroplasty T12 recollapse. Radiographs showing the cemented vertebra just after the vertebroplasty (A and B) and 4 months later (C and D). Recollapse of the T12 vertebra progressed over time.

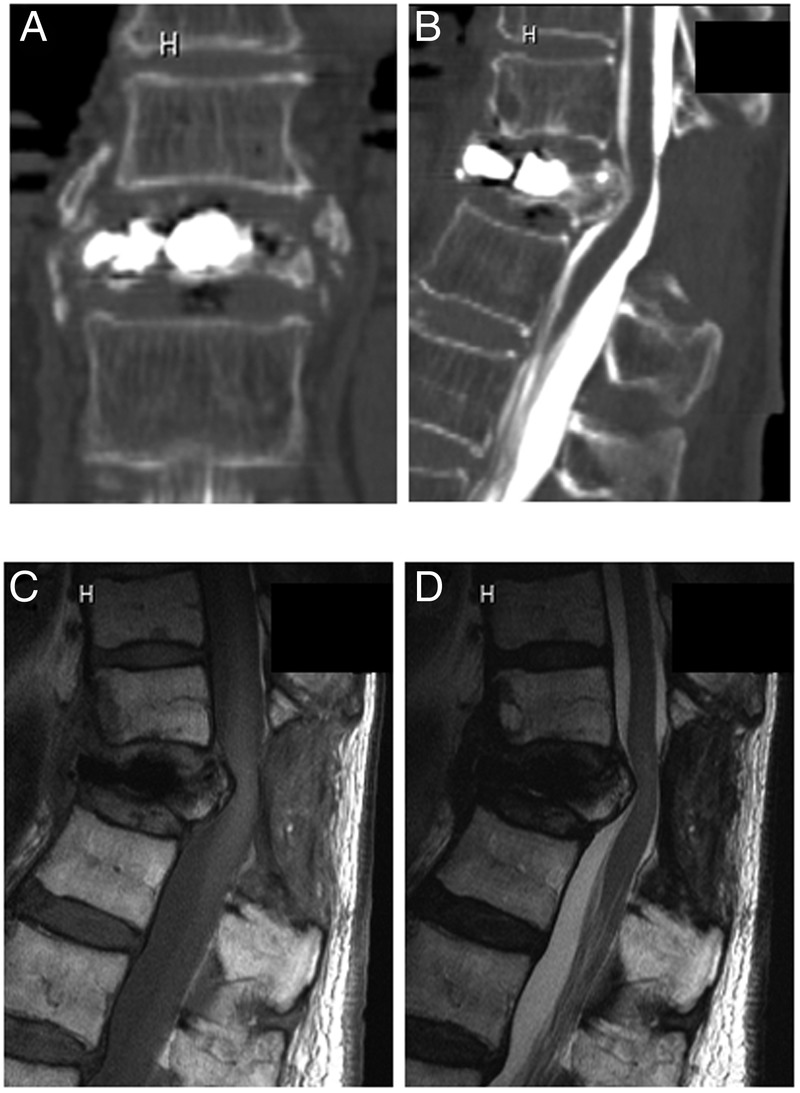

Figure 2.

Two months after percutaneous vertebroplasty in case 1. (A and B) CT images showing cement fragmentation in the T12 vertebra. (C) T1-weighted and (D) T2-weighted MRI showing vertebral recollapse.

Case 2

A 74-year-old woman with T11 and T12 osteoporotic compression fractures was treated at another hospital by PV with PMMA at the same levels (figure 3A). Cement leakage into the spinal canal was already detected by CT scans just after PV (figure 3B). Six months after the PV, her back pain recurred with no traumatic episode. She was referred to our hospital because of intense, progressive back pain; she was unable to lie in a supine position due to the pain. Radiographs showed a local kyphotic deformity (Cobb angle 43°) (figure 3C). CT scans again showed the existing PMMA leakage into the spinal canal (figure 3D). MRI of the T12 vertebra revealed fluid collection around the cement, with low and high intensity in the T1-weighted and T2-weighted images, respectively (figure 4A, B). This pathological condition might reflect osteonecrosis, since MRI fluid sign is correlated with the histopathological evidence of osteonecrosis.18

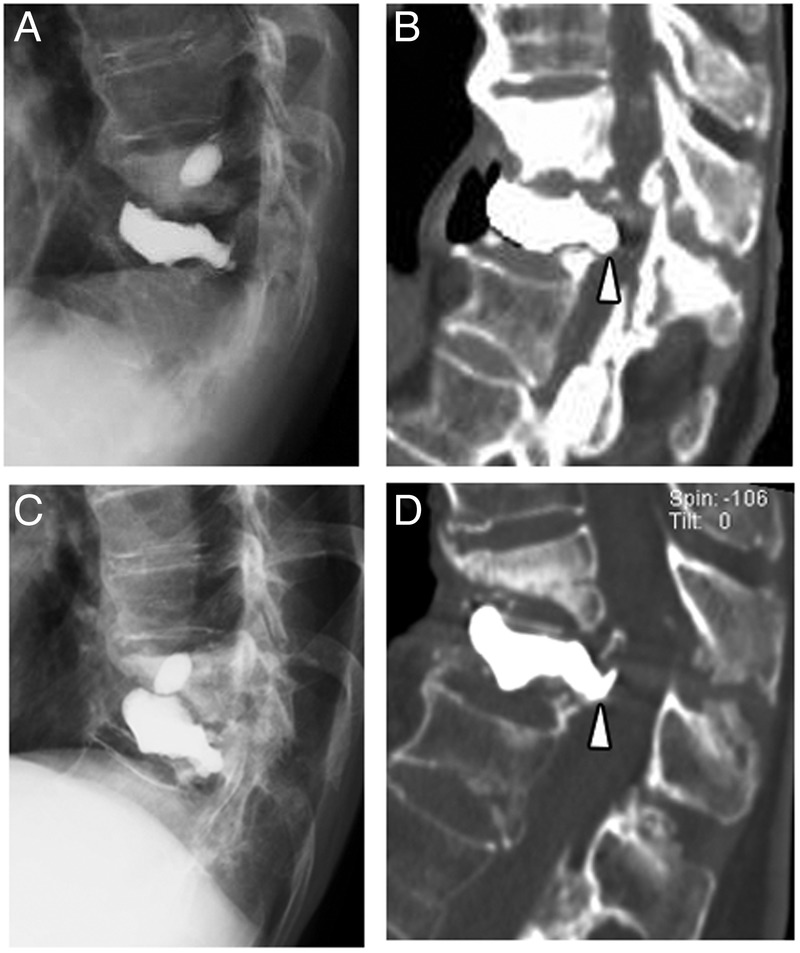

Figure 3.

Case 2: a 74-year-old woman with postpercutaneous vertebroplasty T11 and T12 recollapse. (A) Radiographic and (B) CT images showing cemented T11 and T12 vertebrae just after vertebroplasty. Cement leakage into the spinal canal was observed at T12 (B: arrowhead). Seven months after vertebroplasty, (C) radiographic and (D) CT images showing progressive recollapse and cement leakage (arrowhead).

Figure 4.

(A) T1-weighted and (B) T2-weighted MRI in case 2 showing fluid collection around the cement at the T12 vertebra.

Case 3

A 64-year-old woman had neurological deficit in her lower extremities, and her condition was diagnosed at another hospital as L1 osteoporotic burst fracture. She underwent PV using PMMA at that institute; the PV was repeated when the first PV did not resolve her back pain. Her back pain was relieved immediately after the second PV, but recurred 1 month later without any traumatic episode. She was referred to our hospital due to numbness of the lower extremities and intense low back pain that made it difficult to walk. Physical examination showed reduced deep tendon reflex and weakness of the anterior tibial muscles in both legs. Radiographs showed a local kyphotic deformity (Cobb angle 13°) and recollapse of the cemented vertebra (figure 5A, B).

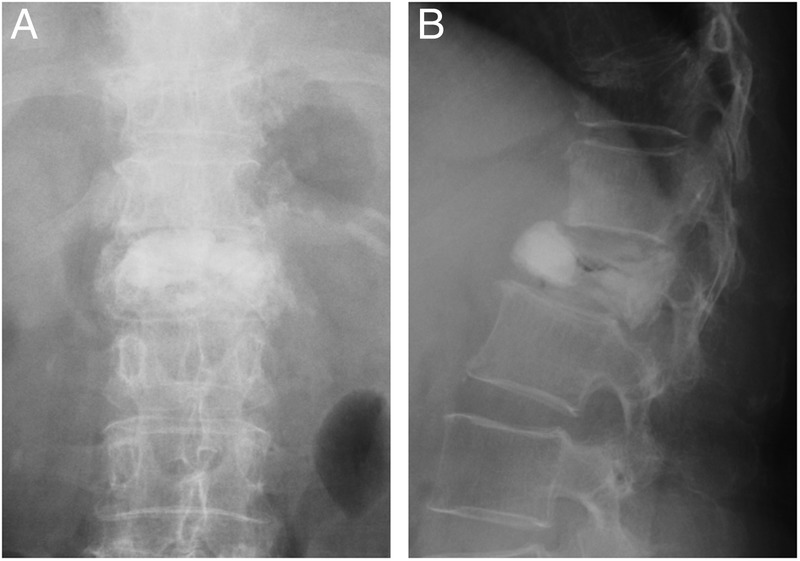

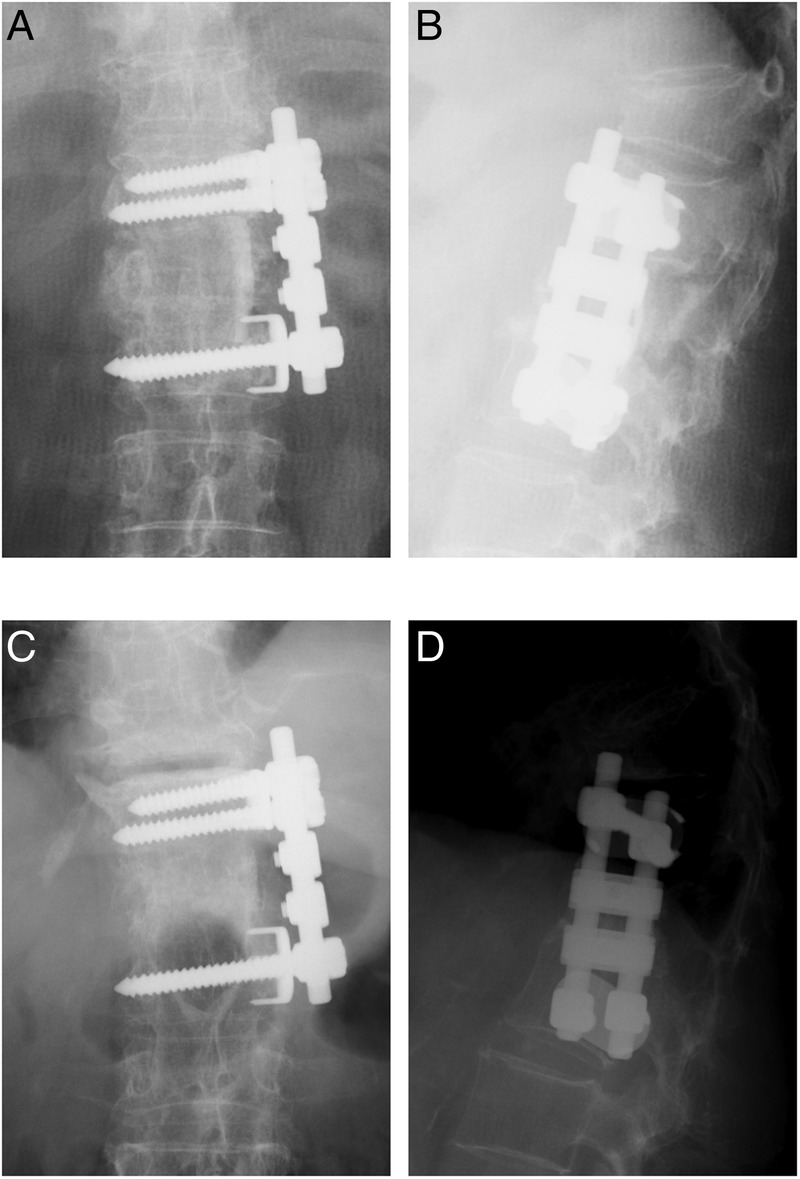

Figure 5.

(A and B) Case 3: A 64-year-old woman with postpercutaneous vertebroplasty L1 recollapse seen on radiographs.

Outcome and follow-up

Case 1

The patient underwent ASF with an iliac crest autograft at the T11-L1 levels (figure 6A–D). Intraoperative findings revealed no adhesion of the PMMA to the vertebral bone, and the PMMA was easily removed. One year after the ASF, radiographs showed solid bony fusion at the T11-L1 levels and the local kyphotic deformity was improved to 22° (figure 6E, F). The patient could walk with a hand crutch, and reported complete relief from low back pain.

Figure 6.

Post-anterior spinal fixation (ASF) images for case 1. (A and B) Radiographic and (C and D) CT images showing successful ASF with an iliac crest autograft. (E and F) One year after ASF, radiographic images showing bony fusion.

Case 2

The patient was treated by removal of the cement and ASF with a fibula autograft at the T10-L1 levels. Radiographs obtained 7 years after the ASF showed solid bony fusion at the T10-L1 levels, and improvement of the local kyphotic deformity to 28° (figure 7A, B). The patient was free of low back pain at the final follow-up.

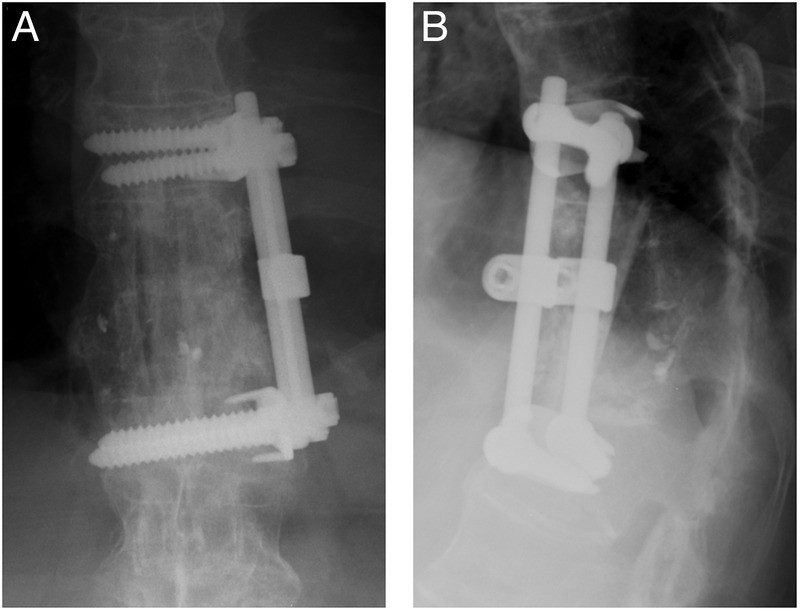

Figure 7.

Post-anterior spinal fixation (ASF) radiographs for case 2. (A and B) Radiographs obtained 7 years after ASF showing bony fusion at the T10-L1 levels.

Case 3

The patient underwent revision surgery with removal of the cement and ASF with an iliac crest autograft at the T12-L2 levels (figure 8A, B). Radiographs obtained 10 years after the ASF showed solid bony fusion at the T12-L2 levels (figure 8C, D). Even though the local kyphotic deformity progressed to 23°, the pain did not recur.

Figure 8.

(A and B) Case 3: after recollapse of cemented vertebra, the patient underwent anterior spinal fixation with iliac crest autografts at T12-L2. (C and D) Radiographs at 10-year follow-up showing solid bony fusion at T12-L2.

Discussion

PV is a minimally invasive technique that has been used successfully to treat painful OVFs.19–21 However, as with the three cases reported here, the cemented vertebrae can recollapse after PV.10 12 13 16 22 23 Regarding the risk factors for this complication, Kang et al23 suggested that a higher preoperative local kyphotic angle and a higher sagittal index24 may result in refracture, based on a comparison of patients with or without refracture. Chen et al16 demonstrated that an MRI finding of preoperative osteonecrosis and a relatively large postoperative restoration of anterior vertebral height without a corresponding correction in the kyphotic angle increased the risk of refracture. Therefore, surgeons should judge the indications for PV carefully. If the patient has a large preoperative local kyphosis and MRIs show necrosis with air or fluid collection in the vertebral body, surgical fixation should be considered as the initial treatment for OVF.

There are a few options for revision strategies for failed PV. If radiographs show poor cement augmentation after PV, repeating the PV may be an option.13 He et al15 reported that repeating a PV effectively relieved pain in all of 15 cases in which pain persisted after an initial PV, and concluded that inadequate filling of the unstable vertebral body with cement was responsible for the lack of pain relief after the first PV.

If an initial PV has used a unipedicle approach, it may be possible to repeat the PV from the other side of the pedicle.13 If the initial approach was bipedicle, it is still possible to repeat the PV, since a normal-sized pedicle is larger than the diameter of the spinal needle used for PV.13 However, this procedure is more difficult than the initial PV, and should only be performed by experienced spine surgeons.

Not all PV failure can be resolved by repeating the PV. In particular, spinal fixation should be decisively selected if severe low back pain worsens and neurological deficits occur due to spinal instability.13 Therefore, surgeons who perform PV need to be able to assess PV failure quickly and to perform the specialised techniques involved in spinal fixation.

Fixation to salvage a failed PV can take an anterior, posterior, or combined anterior and posterior approach. Although there is no strong evidence for choosing one surgical approach over another, some studies have shown that combined anterior and posterior surgery was the most reliable method for treating complications related to PV.13 17 Chou et al10 performed posterior decompression with instrumentation fixation or posterior decompression alone for patients with progressive kyphosis after PV. In these studies, however, the clinical outcomes after salvage surgery were not reported, and the follow-up period was shorter than in our cases. We believe that ASF is the optimal salvage procedure, since it allows for the direct decompression of nerve tissue, reconstruction of the collapsed spinal column, and preservation of the ligaments and muscles that stabilise the posterior spine.25 Moreover, anterior fixation enables a shorter fusion length than posterior fixation. Loss of correction after ASF is a concern, as shown in our cases. However, ASF provided long-term pain relief for these patients, even with the progression of the kyphotic deformity. In fact, Lakshmanan et al26 demonstrated that there was no significant relationship between patients’ quality of life and loss of kyphosis correction after spinal fusion for thoracolumbar vertebral fractures. Our present cases indicate that ASF can be an appropriate procedure for salvaging a failed PV, although additional posterior fixation might become necessary because multilevel corpectomies or severe osteoporosis in geriatric patients require posterior reinforcement in some cases.27

In case 1 and 3, we used iliac crest as a bone strut because longitudinal length of the grafted area was <6 cm. If the iliac crest harvested is longer than 6 cm, the crest bone has a curvature structure and is not appropriate as a strut for ASF. In fact, when performing corpectomy with removal of two vertebrae length usually longer than 6 cm is needed. Therefore, we used fibula autograft for case 2 to acquire stabilised fixation with sufficient length of strut.

As with our cases, Miyagi et al12 also used ASF to treat patients with a late collapse of cemented vertebrae, and found that the patients improved after surgery, although the patients were only followed within a year. Our cases demonstrate good surgical outcomes over a longer follow-up period, emphasising the efficacy of ASF after a failed PV.

In case 1, the patient underwent laminectomy in addition to PV. We believe that this procedure is contraindicated for the treatment of OVF. Decompressive laminectomy without fixation for OVF patients further destabilises the spine and increases kyphotic deformity, with subsequent neurological deterioration. In fact, a previous study reported the complete failure of decompressive laminectomy for osteoporotic vertebral collapse.28 Since the posterior column and the associated soft tissues are key to stabilising the spine,25 preserving the posterior complex is an important initial consideration when treating OVFs. If posterior spinal decompression is absolutely necessary, fixation is mandatory to stabilise the spinal column.

Although we only reported OVF cases that were initially treated by PV, balloon kyphoplasty (BKP) is also widely used to manage OVFs. In BKP, inflatable bone tamps are used before injecting the bone cement, with the goal of correcting vertebral deformity and controlling the distribution of the cement.29 30 BKP has less risk of cement leakage, a tendency toward longer fracture-free survival and less loss of kyphotic-deformity correction compared with PV.30 Similar to PV, however, BKP carries a risk of recollapse of the cemented vertebra,31 which requires a similar salvage technique.

Learning points.

We presented three patients diagnosed with thoracic osteoporotic vertebral fractures who had undergone percutaneous vertebroplasty (PV) at other institutes.

After recollapse occurred at the cemented vertebrae, we performed anterior spinal fixation (ASF).

In all cases, ASF relieved the patient’s severe low back pain, and there was no recurrence of symptoms during the follow-up period of 6 years, on average.

ASF is the optimal salvage procedure, since it allows for (1) the direct decompression of nerve tissue, (2) reconstruction of the collapsed spinal column, (3) preservation of the ligaments and muscles that stabilise the posterior spine and (4) shorter fusion length.

Surgeons who perform PV need to be able to perform spinal fixation as salvage surgery for PV failure.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Mikihito Ito at St Luke's International Hospital, for providing detailed information on one of the patients.

Footnotes

Contributors: NN, KF and MS conducted the surgeries. NN wrote the manuscript and MM supervised the writing of the manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Silverman SL. The clinical consequences of vertebral compression fracture. Bone 1992;13(Suppl 2):S27–31. 10.1016/8756-3282(92)90193-Z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Galibert P, Deramond H, Rosat P et al. [Preliminary note on the treatment of vertebral angioma by percutaneous acrylic vertebroplasty]. Neurochirurgie 1987;33:166–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yimin Y, Zhiwei R, Wei M et al. Current status of percutaneous vertebroplasty and percutaneous kyphoplasty—a review. Med Sci Monit 2013;19:826–36. 10.12659/MSM.889479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abdul-Jalil Y, Bartels J, Alberti O et al. Delayed presentation of pulmonary polymethylmethacrylate emboli after percutaneous vertebroplasty. Spine 2007;32:E589–93. 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31814b84ba [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baumann C, Fuchs H, Kiwit J et al. Complications in percutaneous vertebroplasty associated with puncture or cement leakage. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2007;30:161–8. 10.1007/s00270-006-0133-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nussbaum DA, Gailloud P, Murphy K. A review of complications associated with vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty as reported to the Food and Drug Administration medical device related web site. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2004;15:1185–92. 10.1097/01.RVI.0000144757.14780.E0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patel AA, Vaccaro AR, Martyak GG et al. Neurologic deficit following percutaneous vertebral stabilization. Spine 2007;32:1728–34. 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3180dc9c36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsai TT, Chen WJ, Lai PL et al. Polymethylmethacrylate cement dislodgment following percutaneous vertebroplasty: a case report. Spine 2003;28:E457–60. 10.1097/01.BRS.0000096668.54378.25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vats HS, McKiernan FE. Infected vertebroplasty: case report and review of literature. Spine 2006;31:E859–62. 10.1097/01.brs.0000240665.56414.88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chou KN, Lin BJ, Wu YC et al. Progressive kyphosis after vertebroplasty in osteoporotic vertebral compression fracture. Spine 2014;39:68–73. 10.1097/BRS.0000000000000042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heo DH, Chin DK, Yoon YS et al. Recollapse of previous vertebral compression fracture after percutaneous vertebroplasty. Osteoporos Int 2009;20:473–80. 10.1007/s00198-008-0682-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miyagi R, Sakai T, Bhatia NN et al. Anterior thoracolumbar reconstruction surgery for late collapse following vertebroplasty: report of three cases. J Med Invest 2011;58:148–53. 10.2152/jmi.58.148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang SC, Chen WJ, Yu SW et al. Revision strategies for complications and failure of vertebroplasties. Eur Spine J 2008;17:982–8. 10.1007/s00586-008-0680-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chiu YC, Yang SC, Chen HS et al. Clinical evaluation of repeat percutaneous vertebroplasty for symptomatic cemented vertebrae. J Spinal Disord Tech 2012;25:E245–53. 10.1097/BSD.0b013e31825ef90f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.He SC, Teng GJ, Deng G et al. Repeat vertebroplasty for unrelieved pain at previously treated vertebral levels with osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures. Spine 2008;33:640–7. 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318166955f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen LH, Hsieh MK, Liao JC et al. Repeated percutaneous vertebroplasty for refracture of cemented vertebrae. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2011; 131:927–33. 10.1007/s00402-010-1236-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ha KY, Kim YH, Chang DG et al. Causes of late revision surgery after bone cement augmentation in osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures. Asian Spine J 2013;7:294–300. 10.4184/asj.2013.7.4.294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lin CL, Lin RM, Huang KY et al. MRI fluid sign is reliable in correlation with osteonecrosis after vertebral fractures: a histopathologic study. Eur Spine J 2013;22:1617–23. 10.1007/s00586-012-2618-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jensen ME, Evans AJ, Mathis JM et al. Percutaneous polymethylmethacrylate vertebroplasty in the treatment of osteoporotic vertebral body compression fractures: technical aspects. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1997;18:1897–904. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lieberman IH, Dudeney S, Reinhardt MK et al. Initial outcome and efficacy of “kyphoplasty” in the treatment of painful osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2001;26:1631–8. 10.1097/00007632-200107150-00026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peh WC, Gilula LA, Peck DD. Percutaneous vertebroplasty for severe osteoporotic vertebral body compression fractures. Radiology 2002;223:121–6. 10.1148/radiol.2231010234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Choi SS, Hur WS, Lee JJ et al. Repeat vertebroplasty for the subsequent refracture of procedured vertebra. Korean J Pain 2013;26:94–7. 10.3344/kjp.2013.26.1.94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kang SK, Lee CW, Park NK et al. Predictive risk factors for refracture after percutaneous vertebroplasty. Ann Rehabil Med 2011;35:844–51. 10.5535/arm.2011.35.6.844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Farcy JP, Weidenbaum M, Glassman SD. Sagittal index in management of thoracolumbar burst fractures. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1990;15:958–65. 10.1097/00007632-199009000-00022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaneda K, Asano S, Hashimoto T et al. The treatment of osteoporotic-posttraumatic vertebral collapse using the Kaneda device and a bioactive ceramic vertebral prosthesis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1992;17(8 Suppl):295–303. 10.1097/00007632-199208001-00015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lakshmanan P, Jones A, Mehta J et al. Recurrence of kyphosis and its functional implications after surgical stabilization of dorsolumbar unstable burst fractures. Spine J 2009;9:1003–9. 10.1016/j.spinee.2009.08.457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kanayama M, Ishida T, Hashimoto T et al. Role of major spine surgery using Kaneda anterior instrumentation for osteoporotic vertebral collapse. J Spinal Disord Tech 2010;23:53–6. 10.1097/BSD.0b013e318193e3a5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kempinsky WH, Morgan PP, Boniface WR. Osteoporotic kyphosis with paraplegia. Neurology 1958;8:181–6. 10.1212/WNL.8.3.181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garfin SR, Yuan HA, Reiley MA. New technologies in spine: kyphoplasty and vertebroplasty for the treatment of painful osteoporotic compression fractures. Spine 2001;26:1511–15. 10.1097/00007632-200107150-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dohm M, Black CM, Dacre A et al. KAVIAR investigators. A randomized trial comparing balloon kyphoplasty and vertebroplasty for vertebral compression fractures due to osteoporosis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2014;35:2227–36. 10.3174/ajnr.A4127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li X, Lou X, Lin X et al. Refracture of osteoporotic vertebral body concurrent with cement fragmentation at the previously treated vertebral level after balloon kyphoplasty: a case report. Osteoporos Int 2014;25:1647–50. 10.1007/s00198-014-2626-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]