Abstract

Aims: Cellular senescence and its secretory phenotype (senescence-associated secretory phenotype [SASP]) develop after long-term expansion of mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs). Further investigation of this phenotype is required to improve the therapeutic efficacy of MSC-based cell therapies. In this study, we show that positive feedback between SASP and inherent senescence processes plays a crucial role in the senescence of umbilical cord blood-derived MSCs (UCB-MSCs). Results: We found that monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) was secreted as a dominant component of the SASP during expansion of UCB-MSCs and reinforced senescence via its cognate receptor chemokine (c-c motif) receptor 2 (CCR2) by activating the ROS-p38-MAPK-p53/p21 signaling cascade in both an autocrine and paracrine manner. The activated p53 in turn increased MCP-1 secretion, completing a feed-forward loop that triggered the senescence program in UCB-MSCs. Accordingly, knockdown of CCR2 in UCB-MSCs significantly improved their therapeutic ability to alleviate airway inflammation in an experimental allergic asthma model. Moreover, BMI1, a polycomb protein, repressed the expression of MCP-1 by binding to its regulatory elements. The reduction in BMI1 levels during UCB-MSC senescence altered the epigenetic status of MCP-1, including the loss of H2AK119Ub, and resulted in derepression of MCP-1. Innovation: Our results provide the first evidence supporting the existence of the SASP as a causative contributor to UCB-MSC senescence and reveal a so far unappreciated link between epigenetic regulation and SASP for maintaining a stable senescent phenotype. Conclusion: Senescence of UCB-MSCs is orchestrated by MCP-1, which is secreted as a major component of the SASP and is epigenetically regulated by BMI1. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 24, 471–485.

Introduction

Human umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stromal cells (UCB-MSCs) have been considered the standard choice for conventional clinical use because of their easy isolation, multipotent ability to differentiate into diverse types of cells (e.g., myocytes, adipocytes, bone osteocytes, chondrocytes, neurons, and hepatocytes), expandable ex vivo culture, little or no immunogenicity due to a lack of HLA-DR expression, and low tumorigenicity (13, 23). To obtain sufficient cells for clinical application, reliable and efficient expansion of MSCs in vitro is required. However, the expansion of UCB-MSCs according to traditional culture techniques comprising serum use, culture onto plasticware, and continuous exposure to oxygen results in a progressive loss of proliferative and differentiation potential with each passage. Similar to primary tissue cells, UCB-MSCs initiate a permanent cessation of cell division, termed senescence, after approximately 50 population doublings (PDs) (19, 49).

Innovation.

Several reports have demonstrated that umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stromal cells (UCB-MSCs) during long-term expansion become susceptible to senescence paralleled with an altered secretory phenotype, termed the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP). However, to what extent and by what means the SASP contributes to the senescence of adult tissue stem cells remain unknown. We showed that monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) is a crucial component of the SASP in human UCB-MSC senescence and determines their responses to allergic asthma treatment in vivo. MCP-1 induction is epigenetically regulated by a reduction in BMI1 in senescent UCB-MSCs. The interplay between BMI1 and MCP-1 consolidates the senescence program in UCB-MSCs, possibly determining their therapeutic potency.

Cellular senescence is triggered by the gradual accumulation of DNA damage and epigenetic alterations that can directly affect the expression of senescence-associated genes (48). Due to incomplete and erratic DNA replication, senescent cells create an intrinsic biological clock for cellular aging and converge on the so-called Hayflick limit of cell division at the molecular level (7, 19, 37, 52). The nuclei of senescent cells are characterized by irreversible changes, resulting in an aberrant nuclear shape (30), loss of heterochromatin-associated protein (e.g., heterochromatin protein-1) structures (22), altered patterns of histone modification that are frequently observed in aged cells (46), and transcriptionally repressive heterochromatin structure called senescence-associated heterochromatin foci, which induces the stable repression of E2F-target genes and represses some growth-promoting genes through the recruitment of the retinoblastoma (Rb) tumor suppressor (36). Furthermore, the conventional cell culture protocol that uses 21% of ambient oxygen could generate reactive oxygen species (ROS) (26), which induce aging-associated cellular responses by activating various signaling pathways, such as tumor protein p53 (p53), nuclear factor of kappa light polypeptide gene enhancer in B-cells (NFκB), phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase (PI3K)/v-akt murine thymoma viral oncogene homolog (AKT), and extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK)/c-Jun kinase (JNK)/p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (p38-MAPK) (15). Although it is suggested that the culture conditions and intrinsic nuclear alterations could cross talk during the senescence process, the detailed mechanism remains to be determined.

Recently, it has been reported that cellular senescence is paralleled by a striking increase in the secretion of many factors that participate in intercellular signaling, termed the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) (16, 29, 44). Although several groups have reported that the execution of cellular senescence involves, and often requires, the secretion of a plethora of factors, it is not immediately clear which soluble factors are major contributors to the SASP and what exact role it plays in cellular senescence (4). In the present study, we show for the first time that senescent UCB-MSCs secrete monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) as a dominant secreted chemokine that positively relays senescence signaling via its cognate receptor chemokine (c-c motif) receptor 2 (CCR2) and reinforces senescence by increasing the protein levels of p53 and p21 via ROS or p38-MAPK signaling. Accordingly, the knockdown (KD) of CCR2 significantly improves the therapeutic outcome of UCB-MSCs by decreasing both cellular and inflammatory mediators in a severe asthma animal model. Moreover, BMI1 protein, a member of the polycomb repressor complex-1 (PRC1), binds to regulatory elements of the MCP-1 locus. Accordingly, a decrease in BMI1 during UCB-MSC senescence derepresses the transcription of MCP-1. Our results thus provide the first evidence supporting the existence of the SASP in senescent UCB-MSCs and contribute novel insights into the role of SASP signaling, which is a causative contributor to UCB-MSC senescence and positively connects the intrinsic and extrinsic circuitry of the process.

Results

Long-term expansion of UCB-MSCs induces cellular senescence

During long-term expansion of UCB-MSCs (more than 11 passages), the cells reached a senescent phase and stopped proliferating in vitro, although the growth rate depended on the donor and passage number (Supplementary Fig. S1A; Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/ars). According to the criteria described in previous reports (2, 24), UCB-MSCs were categorized into early, intermediate, and late phases according to the senescence status. The boundary of each phase corresponded with a marked decrease in PD and the breakpoint of the cumulative PD curve (Supplementary Fig. S1A). Compared with early-phase cells, late-phase UCB-MSCs showed reduced telomerase activity and an enlarged morphology with strong staining of senescence-associated beta-galactosidase (SA-β-gal) (Supplementary Fig. S1B, C). They also exhibited severe defects at the level of proliferation and multilineage differentiation, such as osteogenesis (confirmed by von Kossa staining or alkaline phosphatase [ALP] activity), chondrogenesis (Safranin O staining or glycosaminoglycan [GAG] assay), and adipogenesis (Oil red O staining) (Supplementary Fig. S1D, E). In gene expression analysis, expression of p53 phosphorylated at Ser392, indicative of p53 activation, and the p53 downstream gene p21 began to increase from the intermediate phase, showing full activation in the late phase. Phosphorylated pRb protein, which is observed during cell cycle progression, progressively decreased from the intermediate phase and was barely detected in the late phase (Supplementary Fig. S1F). Notably, the expression of BMI1, which suppresses senescence-triggering genes in adult stem cells (33, 34, 39), was 0.5 ± 0.2-fold lower in late-phase UCB-MSCs than in early-phase cells (Supplementary Fig. S1G). The expression of surface antigens characteristic of MSCs was largely unaffected during UCB-MSC senescence (Supplementary Fig. S2). Taken together, these results indicate that ex vivo expansion of UCB-MSCs up to the late phase induces senescence and results in the loss of stem cell properties, including stemness and differentiation capability, through similar pathways to those of other tissue cells (11). Of note, UCB-MSCs exhibit the heterogeneous kinetics of senescence progress.

Senescent UCB-MSCs possess a secretion profile

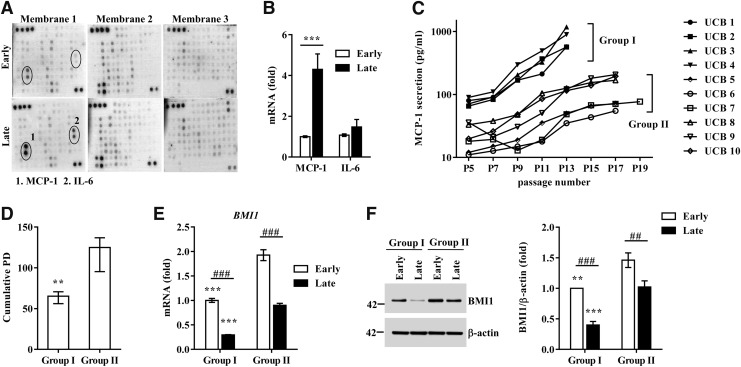

The senescent cells showed their characteristic protein secretion profile (secretome), referred to as the SASP (16). MSCs secrete a variety of cytokines and growth factors with paracrine and autocrine activities that can determine their therapeutic outcomes (20, 42). Thus, we hypothesized that senescent UCB-MSCs would also use a similar SASP phenomenon to actively regulate the senescence process. To address this hypothesis, we performed a cytokine array containing 200 proteins (interleukins, 35; chemokines, 11; other cytokines, 154; Supplementary Fig. S3A) using conditioned medium (CdM) from early- and late-phase UCB-MSCs. The levels of five proteins—MCP-1, interleukin-6 (IL-6), neurotrophin 4 (NT-4), chemokine cxc motif ligand 16 (CXCL16), and Fas-ligand (FASLG)—were markedly increased in the CdM of late-phase cells. Of these, the increase in IL-6 and MCP-1 was the highest (Fig. 1A). When we measured their mRNA expression levels, only the MCP-1 transcript was significantly increased in the late phase of UCB-MSCs compared with early-phase cells (Fig. 1B).

FIG. 1.

Senescent umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stromal cells (UCB-MSCs) display senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP). (A) Cytokine array analysis using conditioned medium collected from early- and late-phase UCB-MSCs (UCB #3). Two spots in membrane 1 showing significant increases in the late-phase group are marked with circles. (B) qPCR analysis of MCP-1 and IL-6 in early- and late-phase UCB-MSCs (UCB #3, 6, 10). The levels of the genes were normalized to those of β-actin, with the expression levels in the early phase defined as 1 (mean ± SEM; n = 4; **p < 0.01). (C) Based on the monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) protein secretion profile, 10 cases of UCB-MSCs were divided into two groups showing significant differences in the basal level of MCP-1 secretion at the initial passage and a fold increase from the initial passage to the final passage: group I (UCB #1 to #4) and group II (UCB #5 to #10). (D, E) The cumulative population doublings (PD) (D) and expression levels of the BMI1 transcript (E) and protein (F) in group I (UCB #3) and group II (UCB #10) UCB-MSCs at early (passage 4 or 5) and late (passage 10 or 14) phases. The expression level of BMI1 protein was normalized to that of β-actin (BMI1/β-actin). Data are shown as the median ± interquartile range (D, n = 6; Mann–Whitney U test) or mean ± SEM (E, n = 4; F, n = 6; two-way ANOVA). **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 compared with group II. ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001.

To further validate the association between MCP-1 secretion and UCB-MSC senescence, we quantified the amount of MCP-1 protein in CdM of UCB-MSCs derived from 10 individual donors. As shown in Figure 1C, the secretion of MCP-1 gradually increased as the passage number increased in all of the UCB-MSCs tested. Notably, according to the amount and rate of the increase in MCP-1 secretion with each passage, UCB-MSCs could be classified into two groups. These groups showed significant differences in basal MCP-1 secretion at the initial passage (group I vs. group II: 76.7 ± 10.8 pg/ml vs. 21.6 ± 11.0 pg/ml; p < 0.05) and the increase from the initial passage to the final passage (group I vs. group II: 10.6 ± 4.1-fold vs. 5.7 ± 2.3-fold; p < 0.01). Particularly, the cells in group I ceased to proliferate sooner and characteristically showed a faster senescence pattern with a lower cumulative PD and shorter time to doubling cessation than the cells in group II (group I vs. group II: 63.9 ± 6.7 PD vs. 119.7 ± 20.2 PD; p < 0.01) (Fig. 1D). In addition, the levels of both BMI1 transcript and protein were significantly higher in group II than in group I (Fig. 1E, F). We also observed significantly increased secretion of IL-6 protein in the late-phase UCB-MSCs (Supplementary Fig. S3B). However, this tendency varied considerably depending on the donor, which could be the reason for the minor change in the IL-6 transcript (Fig. 1B). Taken together, these data demonstrate that long-term cultivation of UCB-MSCs stimulates the SASP, which releases MCP-1 protein and determines the heterogeneity regarding the senescence process in UCB-MSCs.

MCP-1 increases senescence in UCB-MSCs

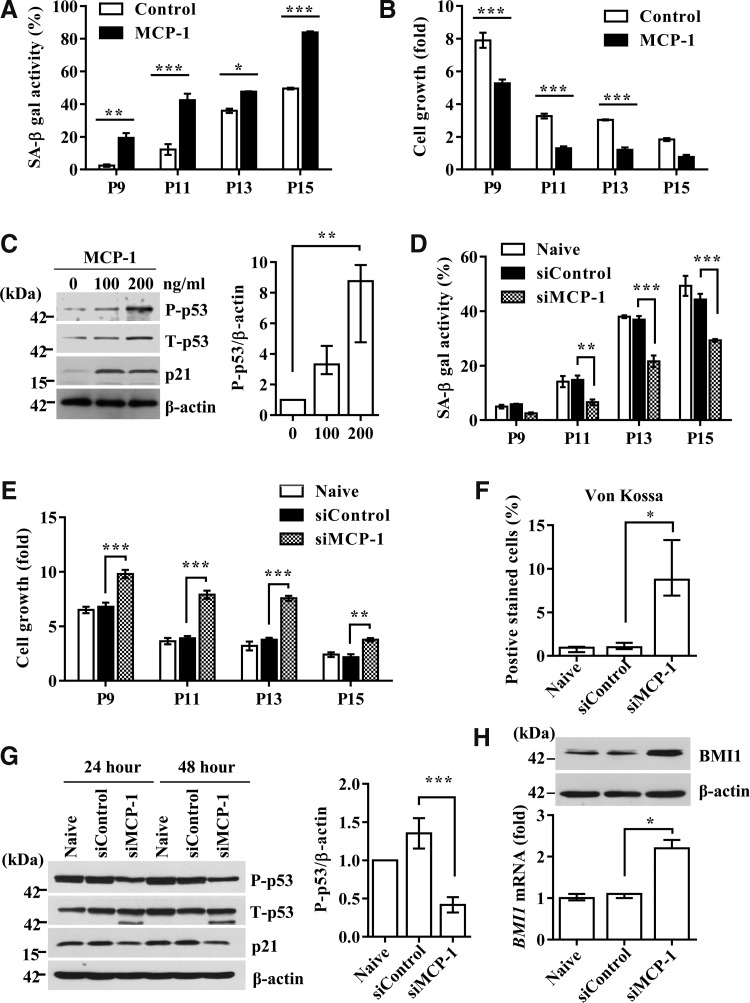

To examine the causative role of MCP-1 in UCB-MSC senescence, 100 ng/ml of recombinant MCP-1 protein (54, 56) was added for 48 h to UCB-MSCs at each passage from the intermediate phase (average P9–11), in which cells showed prominent growth arrest and MCP-1 secretion, up to the late phase. Compared with the untreated control, MCP-1 treatments significantly increased SA-β-gal activity with passaging by up to eight-fold (Fig. 2A and Supplementary Fig. S4A), concomitantly with a considerable delay in cell growth (Fig. 2B). MCP-1 treatment activated the p53-p21 signaling cascade, increasing the protein level of p53 phosphorylated at Ser392 and total p21 (Fig. 2C). In contrast, the pRb pathway was largely unaffected by MCP-1 treatment.

FIG. 2.

MCP-1 stimulates the senescence phenotypes of UCB-MSCs. (A, B) Percentage of cells with positive SA-β-gal staining (A) and growth kinetics (B) in cells exposed to human recombinant MCP-1 for 48 h at each passage from the intermediate phase up to the late phase. Data are shown as the mean ± SEM (n = 3; two-way ANOVA). (C) Western blot analysis of cell cycle inhibitors, including phospho-p53 and p21. β-actin was used as a loading control. The expression level of P-p53 protein normalized to that of β-actin (P-p53/β-actin) is shown as median ± interquartile range (n = 5; Kruskal–Wallis test). (D, E) Quantitative analysis of SA-β-gal activity (D) and cell growth (E) in cells transfected with control (siControl) or MCP-1 siRNA (siMCP-1) at the indicated passage number. Data are shown as mean ± SEM (n = 3; two-way ANOVA). (F) After 3 weeks of osteogenic induction, the level of osteogenic differentiation was quantified by measuring the percentage of cells positive for von Kossa staining (median ± interquartile range; n = 6; Kruskal–Wallis test). (G) Western blot analysis of cell cycle inhibitors in intermediate-phase (passage 11) cells treated with MCP-1 siRNA for 24 or 48 h. The expression level of P-p53 protein is shown as mean ± SEM (n = 7; one-way ANOVA). (H) qPCR and Western blot analysis of BMI1 in naïve cells or cells (UCB-MSC #6) transfected with MCP-1 or control siRNA. The level of BMI1 transcript was normalized to that of β-actin, with the level of expression in the early phase defined as 1 (median ± interquartile range; n = 5; Kruskal–Wallis test). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. P, passage.

The use of siRNA to silence MCP-1 in UCB-MSCs (Supplementary Fig. 4B) significantly blocked both SA-β-gal activity induction and delayed cell growth (Fig. 2D, E, and Supplementary Fig. S4C). Moreover, MCP-1 KD UCB-MSCs showed restored osteogenic differentiation with passaging (Fig. 2F and Supplementary Fig. S4D). At the molecular level, MCP-1 KD cells showed attenuated activation of the p53-p21 pathway (Fig. 2G) and, simultaneously, a 2.2-fold increased expression of BMI1 transcript, which increased the level of BMI1 protein (Fig. 2H). Taken together, these data demonstrate that MCP-1 protein secreted as a component of the SASP plays a causative role in inducing the senescence of UCB-MSCs.

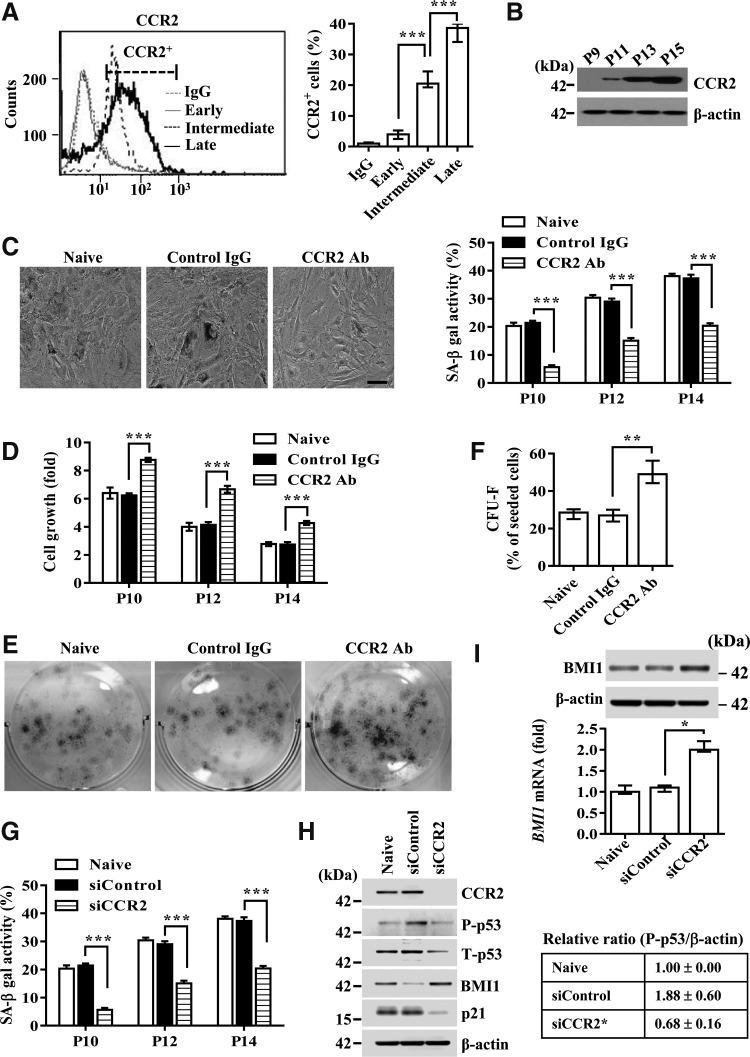

MCP-1-induced UCB-MSC senescence is mediated by its canonical receptor, CCR2

MCP-1 is a proinflammatory cytokine that exerts its biological effects through its cognate receptor, CCR2 (5, 45). The expression of CCR2 in UCB-MSCs was lower in the early phase, but it was considerably upregulated in the intermediate phase and further increased in the terminal senescent phase (Fig. 3A, B). Importantly, treatment with CCR2 blocking antibody significantly reduced SA-β-gal expression (Fig. 3C) and enhanced the growth rate (Fig. 3D) and colony-forming capacity (Fig. 3E, F) of UCB-MSCs in the intermediate phase. The significance of CCR2 was further validated by the fact that CCR2 KD cells had decreased SA-β-gal activity (Fig. 3G) and p53-p21 pathway activation (Fig. 3H). However, they had a 1.9-fold increased expression of BMI1 transcript, which simultaneously increased the level of BMI protein (Fig. 3I). Furthermore, overexpression of CCR2 in early-phase UCB-MSCs remarkably increased cellular senescence, as indicated by induction of SA-β-gal activity (Supplementary Fig. S5A), activation of the p53-p21 signaling cascade, and downregulation of BMI1 expression (Supplementary Fig. S5B). Notably, silencing of MCP-1 less affected the senescence triggered by overexpression of CCR2. These results collectively suggest that CCR2 is a key signaling factor for the secreted MCP-1 that triggers the cellular senescence of UCB-MSCs.

FIG. 3.

CCR2 is a crucial mediator of UCB-MSC senescence. (A) Flow cytometric analysis of CCR2 expression in early, intermediate, and late passages of UCB-MSCs. The percentage of CCR2+ cells is shown on the right side of the FACS histogram (mean ± SEM; n = 5; one-way ANOVA). (B–E) Western blot analysis of CCR2 protein (B), SA-β-gal staining (C), cell growth kinetics (D), and colony-forming assay (E, F) in UCB #6 cells at the indicated passage (P) number treated with isotype (control IgG) or CCR2 blocking antibody (CCR2 Ab) for 48 h. (F) CFU-F activity was quantified as colony counts as the percentage of seeded cells and is shown as median ± interquartile range (n = 6; Kruskal–Wallis test). (G–I) SA-β-gal staining (G) and expression of the cell cycle inhibitor proteins (p21 and P-p53) (H) and BMI1 transcript and protein (I) in UCB #6 cells at the indicated passage number transfected with scrambled control (siControl) or CCR2 (siCCR2) siRNA. β-actin was used as a control for Western blot analysis. The level of BMI1 transcript relative to the value of naïve cells is shown as the median ± interquartile range (n = 5; Kruskal–Wallis test). (H) The relative level of P-p53 to β-actin was quantified and is shown as the median ± interquartile range (n = 3; Kruskal–Wallis test). Data for SA-β-gal staining (C, G, n = 5) and cell growth (D, n = 3) are shown as mean ± SEM (two-way ANOVA). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

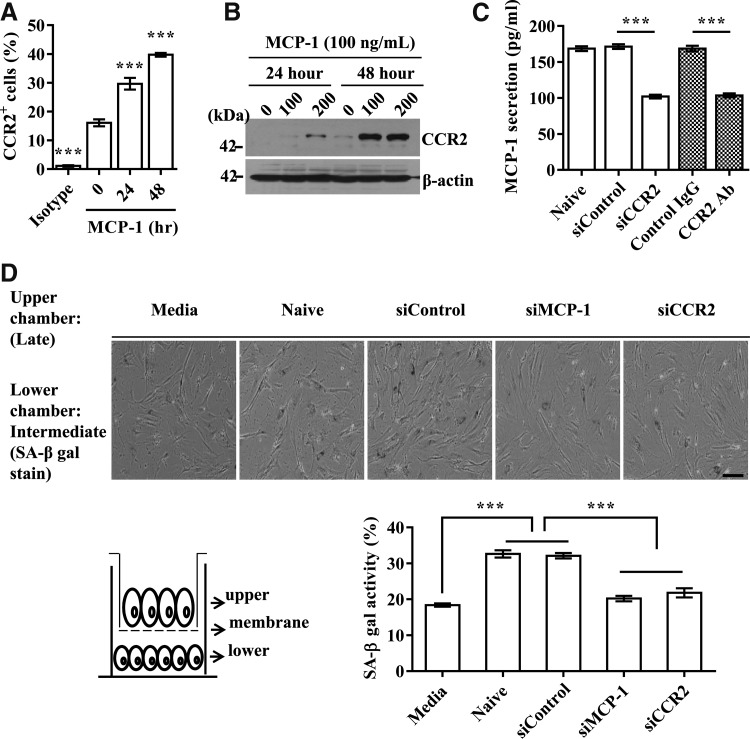

Autocrine/paracrine-positive loop of MCP-1 secretion through CCR2

Cellular senescence can be stably sustained by the autocrine/paracrine-positive regulatory loop of secreted SASP factors (28, 43). To test whether the MCP-1 and CCR2 signaling cascade can use a similar mechanism, we first examined whether MCP-1 and CCR2 could regulate each other's expression. Exposure of intermediate-phase UCB-MSCs to MCP-1 protein increased the expression of CCR2 in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 4A, B). Similarly, the repression of CCR2 by either siRNA or a blocking antibody decreased the secretion of MCP-1 by 1.5-fold (Fig. 4C), suggesting positive feedback between MCP-1 and CCR2.

FIG. 4.

Positive feedback between MCP-1 and CCR2 in autocrine and paracrine manner. (A, B) Increased CCR2 expression analyzed by flow cytometry (A) and Western blot (B) following MCP-1 (100 ng/ml) treatment of UCB-MSC #10 cells. (C) Secretion of MCP-1 was examined following inhibition of CCR2 by blocking antibody (CCR2 Ab) or siRNA (siCCR2). (D) Representative images of SA-β-gal staining (upper panel) and quantification of SA-β-gal-positive cells (low panel) in intermediate-phase cells (UCB #10; passage 9) after coculture with late-phase cells transfected with the indicated siRNA for 48 h. Note that a Transwell chamber with a small pore size (1 μm) blocks physical contact between cells in the upper and chambers. The numbers of SA-β-gal-positive cells of the intermediate phase in the lower chamber were measured. Data are shown as the mean ± SEM (n = 5; one-way ANOVA). ***p < 0.001. Scale bar: 50 μm.

Next, to determine whether the MCP-1 and CCR2 cascade can trigger UCB-MSC senescence as a paracrine action, we cocultured intermediate- and late-phase UCB-MSCs in a Transwell chamber that prevents direct cell–cell contact due to its small pore size (1 μm). The SA-β-gal activity in intermediate-phase cells was increased by coculture with late-phase senescent cells. However, SA-β-gal activity was significantly reduced when the late-phase cells in the upper chamber were treated with MCP-1 or CCR2 siRNA (Fig. 4D). Together, these results demonstrate that the autocrine/paracrine amplification feedback between MCP-1 and CCR2 is essential to the progression of UCB-MSC senescence.

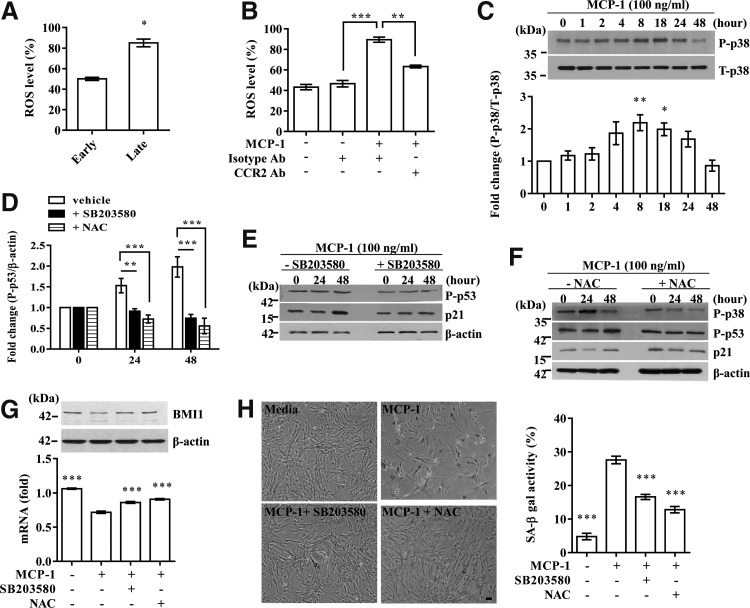

Role of oxidative stress and p38-MAPK in MCP-1-mediated UCB-MSC senescence

Oxidative stress is a central contributor to senescence-like cell arrest (12,18) and is induced by the MCP-1 and CCR2 cascade in immune cells (17). Accordingly, the level of ROS was significantly increased by long-term expansion of UCB-MSCs (Fig. 5A) and treatment with MCP-1 recombinant protein. However, this increase was prevented by CCR2 blocking antibody (Fig. 5B). Moreover, p38-MAPK, a crucial mediator of ROS-induced senescence, was activated from 8 h and peaked at 18 h after MCP-1 stimulation (Fig. 5C). Importantly, treatment with SB203580, a chemical inhibitor of p38-MAPK, significantly abrogated the increase in phosphorylated p53 and p21 proteins induced by MCP-1 stimulation (Fig. 5D, E). Addition of N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC), an ROS scavenger, also markedly suppressed the activation of both p38-MAPK and p53-p21 cascades (Fig. 5D, F). Accordingly, SA-β-gal activity (Fig. 5H) as well as the decrease in the levels of BMI1 transcript and protein (Fig. 5G) in the MCP-1-treated UCB-MSCs was significantly abrogated by the interference of p38-MAPK or ROS. Thus, these results suggest a significant role of ROS in MCP-1-mediated UCB-MSC senescence.

FIG. 5.

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) and the p38-MAPK pathway mediate MCP-1-dependent UCB-MSC senescence. (A, B) Quantification of ROS production by long-term expansion of UCB-MSC #10 cells (A) and by treatment with recombinant MCP-1 protein (B) in the presence or absence of CCR2 blocking antibody (CCR2 Ab). Data are shown as the median ± interquartile range (A, n = 4; Mann–Whitney U test) or mean ± SEM (B, n = 5; one-way ANOVA). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. (C) Activation of p38-MAPK, a mediator of ROS signaling, was measured by Western blot. The relative level of P-p38 to T-p38 was quantified and is shown as the mean ± SEM (n = 3; one-way ANOVA). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 compared with 0 h. (D–F) The effects of a chemical inhibitor of p38-MAPK, SB203580 (E), and N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC) (F) on phosphorylated p53 and p21 expression were measured by Western blot. (D) The relative level of P-p53 to β-actin was quantified and is shown as the median ± interquartile range (n = 3; Kruskal–Wallis test). (G and H) Treatment with SB203580 or NAC prevented the increase in SA-β-gal staining (H) and the downregulation of BMI1 transcript and protein (G) induced by MCP-1 treatment. Data for BMI1 expression (G) and SA-β-gal staining activity (H) are shown as the mean ± SEM of at least five independent experiments in UCB-MSC #10 cells (one-way ANOVA). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 compared with MCP-1 treatment. Scale bar: 50 μm.

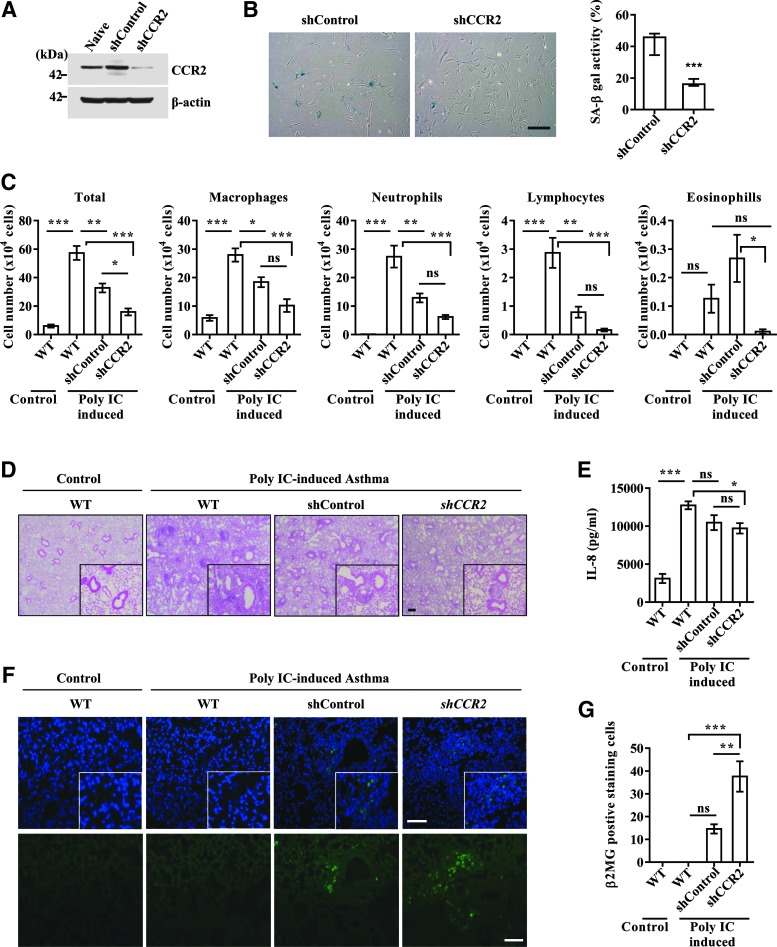

Blocking the MCP-1-CCR2 cascade enhances the therapeutic capacity of UCB-MSCs in an asthma animal model

Next, we investigated the significance of MCP-1-mediated UCB-MSC senescence under in vivo conditions. To address this issue, we compared the therapeutic outcome of UCB-MSCs stably expressing shRNA targeted against CCR2 and scrambled shRNA using a severe murine asthma model. Before injection of the cells, we confirmed the decreased level of CCR2 protein and SA-β-gal activity in CCR2 KD UCB-MSCs (Fig. 6A, B). Furthermore, silencing of CCR2 cells significantly prevented the MCP-1-induced senescent phenotypes, including activation of SA-β-gal and p53-p21 cascades (Supplementary Fig. S5C, D). Similar to previous reports (3, 31), the OVA- and polyIC-sensitized mice had significantly increased levels of cellularity and inflammatory cells, including macrophages, neutrophils, and lymphocytes, in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) (Fig. 6C) and around the bronchial and vascular area in lung tissues (Fig. 6D). These parameters were reduced by administration of both control and CCR2 KD UCB-MSCs. However, CCR2 KD cells more effectively attenuated the infiltration of inflammatory cells in BALF and lung tissues than control UCB-MSCs (Fig. 6C, D). When inflammatory cytokines were measured, injection of UCB-MSCs reduced the level of IL-8 proteins in BALF regardless of the expression level of CCR2, with a greater reduction in CCR2 KD UCB-MSC-injected mice (Fig. 6E). The expression levels of IL-5, IFN-γ, and IL-17 were largely unaffected in the BALF of all of the groups tested (data not shown). When we compared the number of engrafted cells by staining the lung tissue with antibody specific to human β2 microglobulin, CCR2 KD UCB-MSCs yielded greater engraftment capacity in the lung than control cells (Fig. 6F, G). Thus, these results demonstrate that repression of the MCP-1 and CCR2 cascade reinforces the ability of UCB-MSCs to alleviate the inflammatory response in the experimental allergic asthma model.

FIG. 6.

Improved therapeutic outcomes of UCB-MSCs by CCR2 KD in a murine allergic asthma model. All animals were sensitized and challenged with PBS (Control) or OVA and polyI:C (Poly IC-induced asthma). Fifteen days after the first sensitization, mice were intravascularly injected with 3 × 105 UCB-MSCs (UCB #6, passage 8) stably expressing the scrambled (shControl) or CCR2 (shCCR2) shRNA. Twenty-four hours after the final challenge, blood, lung tissue, and BALF were collected. (A, B) Expression of CCR2 protein (A) and the activity of SA-β-gal (B) according to CCR2 KD. (C) Number of total cells, macrophages, neutrophils, lymphocytes, and eosinophils in BALF. (D) Hematoxylin and eosin staining of lung tissues (magnification, ×40). Photomicrographs with higher magnification (×200) are shown in the lower right-hand corner of each panel. (E) Quantification of IL-8 in BALF (n = 9). (F) Immunohistochemical detection of human β-2 microglobulin (green) in lung tissues (magnification, ×100). Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Scale bar: 50 μm. (G) The number of human β-2 microglobulin-expressing cells was assessed from at least seven randomly selected fields. Data are represented as the median ± interquartile range (B, n = 9; Mann–Whitney U test) or mean ± SEM (n ≥ 5; one-way ANOVA). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. ns; nonsignificant.

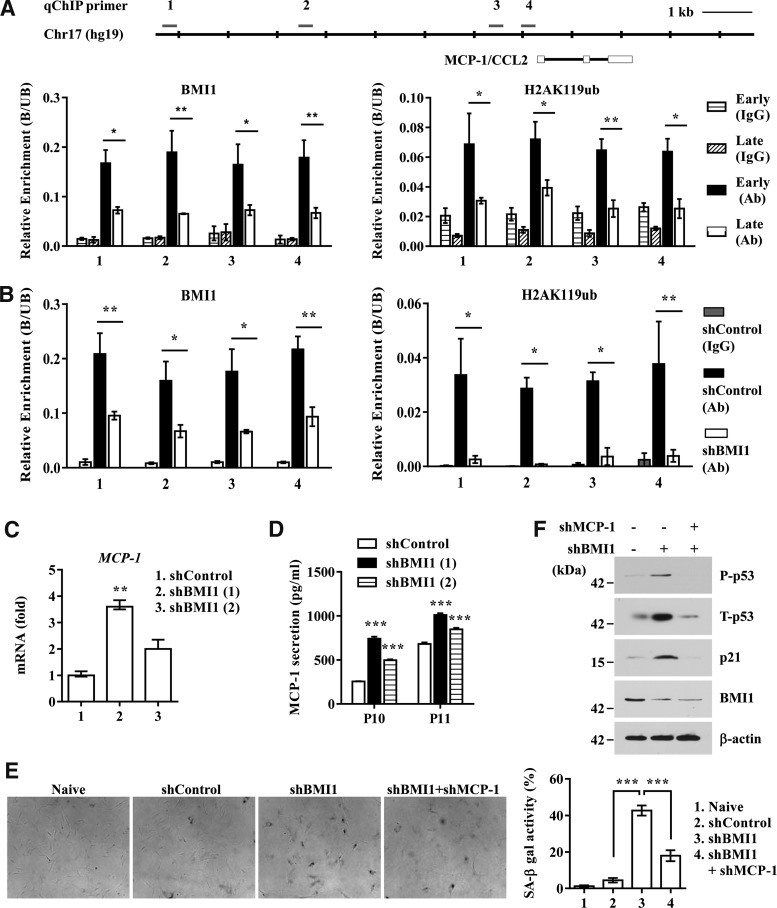

Decline in BMI1 during UCB-MSC senescence derepresses the transcription of MCP-1

Next, we investigated whether the cell-intrinsic senescent program could be linked to the MCP-1-mediated SASP. According to our molecular analysis, p53, p21, and BMI1 were consistently implicated in the MCP-1-mediated SASP observed in senescent UCB-MSCs. The significance of p53 was further confirmed by the finding that ectopic expression of p53 or treatment with nutilin-3, a p53 activator, remarkably increased the secretion of MCP-1 in early-phase UCB-MSCs (Supplementary Fig. S6).

BMI1, a transcriptional repressor, prevents the premature activation of senescence-associated genes, including INK4a and ARF, in a variety of adult stem cells by binding to its target loci (8, 34, 39). Thus, we tested whether MCP-1 expression could be epigenetically regulated by BMI1 protein during UCB-MSC senescence. According to DNase I hypersensitivity and the ChIP-seq database (histone modifications and two transcription repressors, EZH2 and HDAC1) of the entire MCP-1 locus, which is available via the ENCODE project with the UCSC genome browser (http://genome.cse.ucsc.edu/cgi-bin/hgTracks) (Supplementary Fig. S7A), we selected four putative sites and performed chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) analysis to examine the binding of BMI1 to them. We found that BMI1 strongly bound to the MCP-1 locus in early-phase UCB-MSCs, but its enrichment was significantly decreased in senescent late-phase cells (Fig. 7A). Indeed, the distal (−7 kb) and proximal (within–1.5 kb) promoter regions in late-phase cells lost the monoubiquitination at lysine 119 of histone2A (H2AK119Ub) that is catalyzed by BMI1 (Fig. 7A), concomitant with the increase in trimethylation at lysine-4 of histone3 (H3K4me3), a transcriptionally active histone modification (Supplementary Fig. S7B).

FIG. 7.

BMI1 epigenetically represses MCP-1 in UCB-MSCs. (A) The MCP-1 locus marked with the regions of DNase I hypersensitivity and enriched with H3K4me3, H3K27me3, EZH2, and HDAC1 is described in Supplementary Figure S7A. The location of primer sets used in the ChIP assay is marked with a line. ChIP analysis for early- (passage 4) and late- (passage 13) passage UCB-MSCs (UCB #10). The enrichment of BMI1 (left panel) or H2AK119Ub (right panel) is represented as the ratio of the bound to the unbound fraction (B/UB) of ChIP products. (B) ChIP for BMI1-bound (left panel) or H2AK119Ub-modified (right panel) chromatin in UCB-MSCs (UCB #10) stably expressing empty (shControl) or BMI1 (shBMI1) shRNA. Data are shown as the mean ± SEM (n = 3; two-way ANOVA). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. (C, D) Quantification of MCP-1 transcript (C) or secreted MCP-1 protein (D) following BMI1 knockdown in UCB-MSCs (UCB #10). Data are represented as the median ± interquartile range (C, n = 5; Kruskal–Wallis test) or mean ± SEM (n = 3; two-way ANOVA). **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 compared with shControl. (E, F) SA-β-gal staining (E) and expression of the cellular senescence marker proteins (P-p53, p21, and BMI1) (F) in UCB #6 cells transfected with BMI1 shRNA (shBMI1) in the presence or absence of MCP-1 shRNA (shMCP-1). β-actin was used as a control for Western blot analysis. Quantitative data for SA-β-gal staining (E) are shown as the mean ± SEM (n = 5; one-way ANOVA). ***p < 0.001.

Finally, to better support a role for BMI1 protein in maintaining the repressive epigenetic status of the MCP-1 locus in early-phase UCB-MSCs, we established stable cells expressing BMI1 shRNA (Supplementary Fig. S8A). As previously reported, BMI1 KD UCB-MSCs exhibited the typical senescent phenotype, such as an enlarged and flattened morphology and increased SA-β-gal activity (Supplementary Fig. S8B, C). As expected, the promoters of MCP-1 in BMI1 KD cells lost the recruitment of BMI1 and the concomitant H2AK119Ub histone modification (Fig. 7B). The epigenetic change in the MCP-1 locus in BMI1 KD cells coincided with derepression of MCP-1 transcription (Fig. 7C), which resulted in increased secretion of MCP-1 protein (Fig. 7D). The enhanced secretion of MCP-1 protein in BMI1 KD cells triggered cellular senescence, as judged by the increase in SA-β-gal activity (Fig. 7E) and the activation of the p53-p21 signaling pathway (Fig. 7F). Most importantly, the senescent phenotypes shown in BMI1 KD cells were significantly rescued after silencing of MCP-1 (Fig. 7E, F). Taken together, these results demonstrate that BMI1, using a similar mechanism to that seen in the INK4 locus, is responsible for sustaining the repressive epigenetic stability in the promoter of MCP-1, which plays a key role in SASP-mediated stimulation of senescence of UCB-MSCs.

Discussion

Extensive ex vivo expansion by long-term cultivation is required to acquire sufficient numbers of cells for MSC-based therapies. Our present study demonstrated that senescent features of UCB-MSCs that develop through expansion in culture were stimulated by MCP-1, a main mediator of the SASP in UCB-MSCs whose expression was epigenetically regulated by the BMI1 polycomb group protein. In addition, depending on basal MCP-1 secretion, UCB-MSCs exhibited heterogeneous susceptibility to senescence during sustained culture (Fig. 1C), and the expression level of CCR2 was strongly associated with the senescent phenotype of UCB-MSCs (Fig. 3). These results suggest that the status of MCP-1 and CCR2 signaling activity could be adopted as an index for assessing the commitment of the cell to senescence. The MCP-1 and CCR2 signaling activity could also be a good predictor of susceptibility to senescence in response to environmental stresses, which is critical for their therapeutic outcomes. Indeed, in an allergic asthma animal model, CCR2 KD in UCB-MSCs led to greater beneficial effects by not only improving the engraftment capacity of infused stem cells but also reducing the airway inflammation response (Fig. 6). Moreover, since senescence-associated MCP-1 secretion was also seen in bone marrow-derived MSCs (data not shown), the roles of the MCP-1-centered SASP in other adult stem cells, such as hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) and neural stem cells (NSCs), should be investigated to verify whether the SASP could be exploited to regulate the senescence progress of adult stem cells. Interestingly, extracellular vesicles released from bone marrow-derived MSCs play a beneficial paracrine role in reversing injury to renal (9, 10) and lung (41) tissues. The secreted extracellular vesicles, enclosed in a lipid bilayer vesicle with a diameter of ∼50–100 nm, can alter the phenotype of neighboring cells by delivering proteins, mRNA, microRNA, and long noncoding RNA contained in the extracellular vesicle to target cells (41). Thus, elucidation of a potential role of extracellular vesicles in the SASP in UCB-MSCs could be required for further studies.

As a general cause of senescence, oxidative stress and activation of its associated signaling cascades (e.g., p38-MAPK, NF-κB, C/EBPβ, p53, p21) could be generated by chronic exposure to extrinsic stresses. The secreted MCP-1 protein, acting through the CCR2 receptor, increased ROS and in turn activated p38-MAPK and p53/p21 signaling (Fig. 5A–F). Notably, p53, activated by either ectopic expression or its chemical activator, significantly increased the secretion of MCP-1 (Supplementary Fig. S6). Thus, oxidative stress acts as a pivotal second messenger in consolidating MCP-1-mediated stem cell senescence through positive feedback amplification. Indeed, treatment with NAC effectively prevented the senescence of UCB-MSCs after exposure to recombinant MCP-1 protein (Fig. 5G, H). It is well recognized that stem cells in the mesenchymal niches in the body have a relatively low concentration of oxygen at 1%–8% (6, 32). Thus, 21% ambient oxygen would produce oxidized biological macromolecules and result in the generation of ROS (26). Indeed, UCB-MSCs maintained under hypoxic (5% oxygen) conditions showed improved cell growth capacity (Supplementary Fig. S9A) and expression of BMI1 protein (Supplementary Fig. S9B), but reduced induction of the p53-p21 signaling cascade (Supplementary Fig. S9B) and MCP-1 protein secretion (Supplementary Fig. S9C) compared with cells under normoxic (21% oxygen) conditions. These results suggest that the culture conditions relevant to the cellular level of ROS could be a practical strategy to retard the progression of cellular senescence during ex vivo expansion of UCB-MSCs.

In addition, we suggest BMI1 as another possible candidate that mediates this positive feedback because its expression in UCB-MSCs was decreased by MCP-1 and because BMI1 stably maintained the repressive epigenetic status of the MCP-1 locus in early-phase UCB-MSCs (Fig. 7). Since BMI1 is downregulated in replicative senescent fibroblasts, both cell-intrinsic and -extrinsic stimuli converged on reduced BMI1 activity, which could stably reprogram the stressed cells to adopt a senescent phenotype by an epigenetic mechanism.

BMI1 is highly expressed in numerous adult stem cells to protect them against premature aging by epigenetically repressing aging-associated gene expression (38). Indeed, a deficiency of Bmi-1 in HSCs and NSCs results in premature aging and a decreased regenerative capacity (34, 39). The best-characterized target of Bmi-1 is the Ink4 locus, which, by alternative splicing, encodes two important tumor suppressors, p16Ink4a and p19Arf (8). As Bmi-1 tends to be repressed during aging, the Ink4 locus genes become progressively derepressed in several tissues (27) and stem cells (47) from older individuals. Notably, deletion of Ink4a or Arf from Bmi-1−/− mice partially rescued the self-renewal capability of HSCs and NSCs (33,51), suggesting that an additional pathway must also function downstream of Bmi-1 in regulating stem cell aging. The present study provides experimental evidence that MCP-1 is a novel target gene for BMI1 protein to orchestrate stem cell senescence (Fig. 7).

Chronic inflammation has long been regarded as a causative contributor to age-associated degenerative ailments, including diabetes mellitus, atherosclerosis, osteoarthritis, neurodegenerative diseases, and cancers, which are major potential targets of MSC-based cell therapeutics (40). Chronic inflammatory responses redirect the protective inflammatory response to danger signals in the acute phase of inflammation into a self-destructive, damaging, and deregulated proliferation-prone environment. In this regard, chronic inflammation might be the origin site of cancer, and inflammatory microenvironments could be more common in aged tissues. Given that cell therapies are being clinically administered to treat chronic degenerative diseases with persistent inflammation, such an inflammation-prone micromilieu might affect the final outcome of cell therapies by affecting the senescence program of MSCs in a cell-autonomous or noncell-autonomous manner (1, 28, 43). Several studies have reported that a long-lasting deviant profile of inflammatory molecules, including MCP-1, was causatively involved in the initiation and maintenance of aging-related diseases and aging processes (21, 35, 50).

With this in mind, several new angles on the preparation of next-generation MSC-based cellular therapies should be considered. First, ready-to-use MSC-based cell therapies should be cautiously monitored to remove contamination from senescent cells, which could be conducted via a surrogate marker such as MCP-1 and CCR2 that can reveal how far the cells have committed to senescence. Even a small population of senescent cells in the therapy may trigger a stress response inside the other young healthy cells that reinforces itself through a vicious loop. Accordingly, the fewer the cells undergoing senescence in the therapy, the greater the benefit to patients. Once the senescence program in MSCs begins, functional compromise of their multipotency and consecutive loss of therapeutic competence inevitably result. Therefore, screening and depletion of the CCR2-expressing population could be of tremendous value when monitoring the quality of the expanded UCB-MSCs. Notably, these important concepts for MSC therapy were experimentally proven in vivo using the severe murine asthma model (Fig. 6). Thus, cell therapies should be furnished as interfered MCP-1/CCR2 signaling acting on the senescence program, although the preparation of such customized cell therapies would be costly and challenging.

In the present study, we provide the first evidence supporting the existence of the SASP as a causative contributor to UCB-MSC senescence and positive feedback between the intrinsic and extrinsic circuitry of the process. Therefore, our current results provide important insights into an enhanced and integrative understanding of both the functional aspects and regulation of the SASP, which may open up new therapeutic modalities for the preparation of next-generation MSC-based cell therapies.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of MEDIPOST Co., Ltd. UCB was collected from umbilical veins after neonatal delivery with maternal informed consent (Supplementary Table S1). UCB harvests were processed within 24 h of collection. UCB was separated by isolating mononuclear cells with Ficoll-Hypaque solution (density, 1.077 g/cm3; Sigma, St. Louis, MO). The separated mononuclear cells were washed, suspended in Minimum Essential Medium α modification (MEM α; Gibco, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco), and seeded at a concentration of 5 × 105 cells/cm2. Cultures were maintained at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere (21% O2) containing 5% CO2 with a change of culture medium twice a week (55). To maintain cells under hypoxic conditions, the oxygen concentration in the chamber was maintained at 5% with a residual gas mixture consisting of 5% carbon dioxide and balanced nitrogen. Primary bone marrow MSCs (five lots) were purchased from Lonza (PT-2501; Basel, Switzerland).

Reagents

Human recombinant MCP-1 protein (279-MC) was purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). The p38-MAPK inhibitor, SB203580, was obtained from Sigma. Anti-CCR2 antibody (ab32144; Abcam, Cambridge, MA) was used to block CCR2 stimulation. NAC, used to assess antioxidant effects, was purchased from Sigma. Detailed information on the reagents is provided in Supplementary Table S2.

Growth kinetics

Expansion during time in culture was measured using the trypan blue exclusion method. Each passage was cultured for 5 days and cells were obtained with trypsin-EDTA (Gibco), counted, and reseeded at a density of 2000 cells/cm2. Culture medium was replaced twice weekly. The PD was calculated for each passage by dividing the logarithm of the fold increase value obtained at the end of the passage by the logarithm of 2 (24). The PD and cumulative PD were continuously monitored until cells ceased to proliferate between 11 and 19 passages (Supplementary Fig. S1A). Cell growth in the experimental conditions was depicted as the fold increase in the cell number for each passage. A colony-forming unit–fibroblast (CFU-F) assay was performed by seeding 100 cells in a 35-mm culture dish (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) and incubating them in humidified 5% CO2 at 37°C; culture medium was exchanged every 3 days. After 2 weeks, the dishes were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Gibco), fixed with 100% methanol, and stained with 3% crystal violet (Sigma). The number of colonies was counted.

Detection of the intracellular ROS level

ROS stress was assessed using a fluorescent probe (carboxy-H2DCFDA; C400; Invitrogen, La Jolla, CA) as previously described (53). Briefly, cells seeded in a T75 tissue culture flask at a density of 2000 cells/cm2 were maintained for 5 days before incubating with 10 μM C400 for 1 h. The ROS fluorescence intensity was analyzed using an FACSCalibur flow cytometer, and the ROS level was represented as the percentage of C400-stained cells.

Evaluation of the multilineage differentiation potential

Multilineage potential was assessed by incubating cells under specific conditions to induce differentiation into osteocytes, chondrocytes, and adipocytes (25). The procedures used are detailed in the Supplementary Materials and Methods.

Cytokine antibody array and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

To obtain CdM, cells were serum starved for 24 h, washed, and then cultivated for a further 24 h with fresh serum-free medium. CdM was collected and clarified by centrifugation at 200 g for 5 min. The presence of cytokines within the harvested CdM was detected using a commercially available proteome profiler array membrane, the Human Inflammatory Cytokine Array C2000 and Analysis Tool (AAH-CYT-2000) (RayBiotech, Norcross, GA). The detail of array maps in each membrane is described in Supplementary Figure S3A. Human MCP-1 (DCP00) and IL-6 (D6050) protein were quantified by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA; R&D Systems) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Results were obtained by measuring absorbance at 450 nm and were normalized per 1 × 104 cell number.

Real-time polymerase chain reaction

Total RNA was isolated using an RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Crawley, UK) according to the manufacturer's instructions. One microgram of total RNA was reverse transcribed to cDNA using oligo-dT primers (Invitrogen) and superscript II polymerase (Invitrogen). Amplification was performed with the LightCycler real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) system using LightCycler TaqMan Master Mixtures (Roche), sequence-specific probes (Roche), and specific primers (Supplementary Table S3). Relative quantities of the mRNA of interest were calculated by the comparative threshold cycle (2−ΔΔCt) method and normalized to those of β-actin. Values are expressed as fold increases relative to the levels of uninduced cells, defined as 1.

RNA interference

siRNAs for MCP-1, CCR2, and control were purchased from Dharmacon (Chicago, IL). The siRNA pool consisted of four duplexes (Supplementary Table S3). Cells were treated with control siRNA (50 nM), MCP-1 siRNA (50 nM), or CCR2 siRNA (50 nM) for 24 h using DharmaFECT reagent (Dharmacon). When cells were examined at multiple passages, de novo transfection of siRNAs was performed at each passage. To establish UCB-MSCs stably expressing MCP-1, CCR2, or BMI1 shRNA, the shRNA was cloned into pSicoR lentiviral vector (Addgene plasmid 12084). Lentivirus was produced by a four-plasmid transfection system according to the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen) and concentrated by precipitation using polyethylene glycol 6000. The concentrated virus was infected into UCB-MSCs with 10 μg/ml polybrene (Invitrogen). The cells were further maintained for at least 3 weeks in the presence of 1 μg/ml puromycin (Invitrogen) for selection, and the effect of ectopic expression was examined by quantitative PCR (qPCR) and Western blotting. The target sequences for each shRNA are indicated in Supplementary Table S3.

Overexpression and activation of p53 and CCR2

To overexpress the p53 protein, the coding sequence of full-length human p53 was cloned into the PCDNA3 expression vector. Cells were then transfected using transfection reagent (Invitrogen). For p53 activation, cells were treated with 10 μM nutilin-3 for 24 h (Sigma). Human CCR2 cDNA amplified by PCR using a human CCR2 open-reading frame clone (BC074751; Dharmacon) as a template was cloned into the pLenti7.5/V5 TOPO lentiviral vector (Invitrogen). Five days after infection of lentivirus containing the CCR2-expressing cassette, the effects of ectopic expression of CCR2 were examined using Western blot analysis.

SA-β-gal staining

SA-β-gal staining was used as a biomarker of senescence in UCB-MSCs. SA-β-gal activity was qualitatively assessed with a histochemical staining kit (CS0030; Sigma) according to the manufacturer's instructions, followed by inverted microscopy. The percentage of senescent cells was represented by the number of stained cells per the total number of cells.

Telomerase activity assay

Telomerase activity was measured by a telomeric repeat amplification protocol (TRAP) assay with a telomerase PCR ELISA kit (TeloTAGGG Telomerase PCR ELISA, 11854666910; Roche) according to a published protocol (14). Approximately 2 × 105 cells were harvested for each reaction and centrifuged at 3000 g for 10 min at 4°C. The absorbance for the final product was acquired by measuring absorbance at 450 nm.

Western blotting

Cell extracts were prepared in buffer containing 9.8 M urea, 4% CHAPS, 130 mM dithiothreitol, 40 mM Tris-HCl, and 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate. Protein concentrations were measured by a bicinchoninic acid assay (Sigma). Protein extracts (15 μg) were separated by SDS-PAGE and the resolved proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Each membrane was incubated with anti-phospho-p53 (Ser392) (#9281), anti-p53 (#9282), anti-CCR2 (ab32144; Abcam), anti-p21 (#3688), anti-phospho-Rb (Ser780) (#9307), anti-Rb (#9309), anti-phospho-p38 (Thr180/Tyr182) (#9211), anti-p27 (#3688) (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA), anti-BMI1 (39993; Active Motif, Carlsbad, CA), or anti-β-actin (A5441; Sigma). The density of signals for the indicated proteins was measured and quantified using NIH ImageJ software.

Asthma animal model

All animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Ulsan College of Medicine. To generate a murine model of severe asthma, 6-week-old BALB/c mice (OrientBio, Gapyong, Gyeonggi-do, Korea) were sensitized and challenged by intranasal administration with 75 μg OVA (Sigma) and 10 μg polyI:C (Calbiochem) at days 0, 1, 2, 3, 7, 14, 21, 22, and 23. Mice were injected with 3 × 105 UCB-MSCs by intravascular injection at day 15. BALF, lymph nodes, and lung tissues were obtained from the mice 24 h after the last immunization. The number of monocytes, eosinophils, neutrophils, and lymphocytes and the concentrations of IL-10 and IL-8 in BALF were measured as previously described (3, 31). For histopathological evaluation, the lungs were perfused with 5 ml PBS through the right ventricle and inflated with 1 ml PBS through the trachea. The inflated lungs were fixed by immersing them in 10% neutral buffered formalin solution for 24 h. Fixed lung tissues were embedded in paraffin and sectioned to 4 μm thickness and the magnitude of inflammation around the bronchial and vascular area was examined by hematoxylin and eosin staining. The engraftment of the infused UCB-MSCs was determined by immunofluorescence analysis of human B2-microglobulin (ab15976; Abcam) visualized using an FITC-labeled secondary antibody. Nuclei were counterstained using 4′,6-diamino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Sigma).

ChIP assay

ChIP analysis was performed using a Magna ChIP™ G kit (Upstate-Millipore, Billerica, MA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The procedures used are detailed in the Supplementary Materials and Methods section.

Statistical analyses

Data are reported as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) if the total sample size was more than 20 or as median ± interquartile range if the total sample size was smaller than 20 and were analyzed by GraphPad Prism 6.0 software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). Differences and significance were verified by one-way or two-way ANOVA, followed by Bonferroni post hoc tests when the total sample size was more than 20. Otherwise, we performed a nonparametric Kruskal–Wallis and Mann–Whitney U test for comparing three and two groups, respectively. All p-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary data include Supplementary Materials and Methods, nine figures, and three tables and can be found with this article online.

Supplementary Material

Abbreviations Used

- ALP

alkaline phosphatase

- BALF

bronchoalveolar lavage fluids

- CCR2

chemokine (c-c motif) receptor 2

- CdM

conditioned medium

- ChIP

chromatin immunoprecipitation

- H2AK119Ub

monoubiquitination at lysine-119 of histone2A

- H3K4me3

trimethylation at lysine-4 of histone3

- HSCs

hematopoietic stem cells

- IL-6

interleukin-6

- KD

knockdown

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- MCP-1

monocyte chemoattractant protein-1

- MSCs

mesenchymal stromal cells

- NAC

N-acetyl-L-cysteine

- NSCs

neural stem cells

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- PDs

population doublings

- Rb

retinoblastoma

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SASP

senescence-associated secretory phenotype

- SA-β-gal

senescence-associated beta-galactosidase

- UCB-MSCs

umbilical cord blood-derived MSCs

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Mariusz Ratajczak for critical comments. This work was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) (2010-0029521 and 2015R1A2A2A01003235), the Korea Korean Health Technology R&D Project, Ministry of Health and Welfare of the Republic of Korea (A120216 and HI14C3339), and the Asan Institute for Life Science (2014-526).

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Acosta JC, O'Loghlen A, Banito A, Guijarro MV, Augert A, Raguz S, Fumagalli M, Da Costa M, Brown C, Popov N, Takatsu Y, Melamed J, d'Adda di Fagagna F, Bernard D, Hernando E, and Gil J. Chemokine signaling via the CXCR2 receptor reinforces senescence. Cell 133: 1006–1018, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahmadbeigi N, Soleimani M, Gheisari Y, Vasei M, Amanpour S, Bagherizadeh I, Shariati SA, Azadmanesh K, Amini S, Shafiee A, Arabkari V, and Nardi NB. Dormant phase and multinuclear cells: two key phenomena in early culture of murine bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells Dev 20: 1337–1347, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bang B-R, Kwon H-S, Kim S-H, Yoon S-Y, Choi J-D, Hong GH, Park S, Kim T-B, Moon H-B, and Cho YS. Interleukin-32γ suppresses allergic airway inflammation in mouse models of asthma. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 50: 1021–1030, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bartek J, Hodny Z, and Lukas J. Cytokine loops driving senescence. Nat Cell Biol 10: 887–889, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bartoli C, Civatte M, Pellissier JF, Figarella-Branger D. CCR2A and CCR2B, the two isoforms of the monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 receptor are up-regulated and expressed by different cell subsets in idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. Acta Neuropathol 102: 385–392, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Basciano L, Nemos C, Foliguet B, de Isla N, de Carvalho M, Tran N, and Dalloul A. Long term culture of mesenchymal stem cells in hypoxia promotes a genetic program maintaining their undifferentiated and multipotent status. BMC Cell Biol 12: 12, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blasco MA. Telomeres and human disease: ageing, cancer and beyond. Nat Rev Genet 6: 611–622, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bracken AP, Kleine-Kohlbrecher D, Dietrich N, Pasini D, Gargiulo G, Beekman C, Theilgaard-Monch K, Minucci S, Porse BT, Marine JC, Hansen KH, and Helin K. The Polycomb group proteins bind throughout the INK4A-ARF locus and are disassociated in senescent cells. Genes Dev 21: 525–530, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bruno S, Grange C, Collino F, Deregibus MC, Cantaluppi V, Biancone L, Tetta C, and Camussi G. Microvesicles Derived from Mesenchymal Stem Cells Enhance Survival in a Lethal Model of Acute Kidney Injury. PLoS ONE 7: e33115, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bruno S, Grange C, Deregibus MC, Calogero RA, Saviozzi S, Collino F, Morando L, Busca A, Falda M, Bussolati B, Tetta C, and Camussi G. Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Microvesicles Protect Against Acute Tubular Injury. J Am Soc Nephrol 20: 1053–1067, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Campisi J. Senescent cells, tumor suppression, and organismal aging: good citizens, bad neighbors. Cell 120: 513–522, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chung HY, Cesari M, Anton S, Marzetti E, Giovannini S, Seo AY, Carter C, Yu BP, and Leeuwenburgh C. Molecular inflammation: underpinnings of aging and age-related diseases. Ageing Res Rev 8: 18–30, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Damien P. and Allan DS. Regenerative therapy and immune modulation using umbilical cord blood–derived cells. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 21: 1545–1554, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Du C, Li D, Lin Y, and Wu M. Differentiation of human nasopharyngeal carcinoma xenografts and repression of telomerase activity induced by arsenic trioxide. Natl Med J India 17: 67–70, 2004 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Finkel T. and Holbrook NJ. Oxidants, oxidative stress and the biology of ageing. Nature 408: 239–247, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Freund A, Orjalo AV, Desprez PY, and Campisi J. Inflammatory networks during cellular senescence: causes and consequences. Trends Mol Med 16: 238–246, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Freund A, Patil CK, and Campisi J. p38MAPK is a novel DNA damage response-independent regulator of the senescence-associated secretory phenotype. EMBO J 30: 1536–1548, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gharibi B, Farzadi S, Ghuman M, and Hughes FJ. Inhibition of Akt/mTOR attenuates age-related changes in mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells 32: 2256–2266, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hayflick L. THE limited in vitro lifetime of human diploid cell strains. Exp Cell Res 37: 614–636, 1965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hodgkinson CP, Naidoo V, Patti KG, Gomez JA, Schmeckpeper J, Zhang Z, Davis B, Pratt RE, Mirotsou M, and Dzau VJ. Abi3bp is a multifunctional autocrine/paracrine factor that regulates mesenchymal stem cell biology. Stem Cells 31: 1669–1682, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hughes PM, Allegrini PR, Rudin M, Perry VH, Mir AK, and Wiessner C. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 deficiency is protective in a murine stroke model. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 22: 308–317, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Imai S. and Kitano H. Heterochromatin islands and their dynamic reorganization: a hypothesis for three distinctive features of cellular aging. Exp Gerontol 33: 555–570, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jaing T-H. Umbilical cord blood: a trustworthy source of multipotent stem cells for regenerative medicine. Cell Transplant 23: 493–496, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jin HJ, Bae YK, Kim M, Kwon SJ, Jeon HB, Choi SJ, Kim SW, Yang YS, Oh W, and Chang JW. Comparative analysis of human mesenchymal stem cells from bone marrow, adipose tissue, and umbilical cord blood as sources of cell therapy. Int J Mol Sci 14: 17986–18001, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jin HJ, Nam HY, Bae YK, Kim SY, Im IR, Oh W, Yang YS, Choi SJ, and Kim SW. GD2 expression is closely associated with neuronal differentiation of human umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Cell Mol Life Sci 67: 1845–1858, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jung Min R, Hyun Jik L, Young Hyun J, Ki Hoon L, Dah Ihm K, Jeong Yeon K, So Hee K, Gee Euhn C, Ing Ing C, Eun Ju S, Ji Young O, Sei-Jung L, and Ho Jae H. Regulation of stem cell fate by ROS-mediated alteration of metabolism. Int J Stem Cells 8: 24–35, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krishnamurthy J, Torrice C, Ramsey MR, Kovalev GI, Al-Regaiey K, Su L, and Sharpless NE. Ink4a/Arf expression is a biomarker of aging. J Clin Invest 114: 1299–1307, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kuilman T, Michaloglou C, Vredeveld LC, Douma S, van Doorn R, Desmet CJ, Aarden LA, Mooi WJ, and Peeper DS. Oncogene-induced senescence relayed by an interleukin-dependent inflammatory network. Cell 133: 1019–1031, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kumar M, Seeger W, and Voswinckel R. Senescence-associated secretory phenotype and its possible role in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 51: 323–333, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lans H. and Hoeijmakers JH. Cell biology: ageing nucleus gets out of shape. Nature 440: 32–34, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee T, Kwon H-S, Bang B-R, Lee Y, Park M-Y, Moon K-A, Kim T-B, Lee K-Y, Moon H-B, and Cho Y. Grape seed proanthocyanidin extract attenuates allergic inflammation in murine models of asthma. J Clin Immunol 32: 1292–1304, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mohyeldin A, Garzón-Muvdi T, Quiñones-Hinojosa A. Oxygen in stem cell biology: a critical component of the stem cell niche. Cell Stem Cell 7: 150–161, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Molofsky AV, He S, Bydon M, Morrison SJ, and Pardal R. Bmi-1 promotes neural stem cell self-renewal and neural development but not mouse growth and survival by repressing the p16Ink4a and p19Arf senescence pathways. Genes Dev 19: 1432–1437, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Molofsky AV, Pardal R, Iwashita T, Park IK, Clarke MF, and Morrison SJ. Bmi-1 dependence distinguishes neural stem cell self-renewal from progenitor proliferation. Nature 425: 962–967, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nakamachi Y, Kawano S, Takenokuchi M, Nishimura K, Sakai Y, Chin T, Saura R, Kurosaka M, and Kumagai S. MicroRNA-124a is a key regulator of proliferation and monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 secretion in fibroblast-like synoviocytes from patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 60: 1294–1304, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Narita M, Nunez S, Heard E, Narita M, Lin AW, Hearn SA, Spector DL, Hannon GJ, and Lowe SW. Rb-mediated heterochromatin formation and silencing of E2F target genes during cellular senescence. Cell 113: 703–716, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oberdoerffer P. and Sinclair DA. The role of nuclear architecture in genomic instability and ageing. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 8: 692–702, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Park IK, Morrison SJ, and Clarke MF. Bmi1, stem cells, and senescence regulation. J Clin Invest 113: 175–179, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Park IK, Qian D, Kiel M, Becker MW, Pihalja M, Weissman IL, Morrison SJ, and Clarke MF. Bmi-1 is required for maintenance of adult self-renewing haematopoietic stem cells. Nature 423: 302–305, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Prockop DJ. Concise Review: two negative feedback loops place mesenchymal stem/stromal cells at the center of early regulators of inflammation. Stem Cells 31: 2042–2046, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Quesenberry PJ, Goldberg LR, Aliotta JM, Dooner MS, Pereira MG, Wen S, and Camussi G. Cellular phenotype and extracellular vesicles: basic and clinical considerations. Stem Cells Dev 23: 1429–1436, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ranganath SH, Levy O, Inamdar MS, and Karp JM. Harnessing the mesenchymal stem cell secretome for the treatment of cardiovascular disease. Cell Stem Cell 10: 244–258, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rodier F. and Campisi J. Four faces of cellular senescence. J Cell Biol 192: 547–556, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Salama R, Sadaie M, Hoare M, and Narita M. Cellular senescence and its effector programs. Genes Dev 28: 99–114, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sanders SK, Crean SM, Boxer PA, Kellner D, LaRosa GJ, Hunt SW., 3rd. Functional differences between monocyte chemotactic protein-1 receptor A and monocyte chemotactic protein-1 receptor B expressed in a Jurkat T cell. J Immunol 165: 4877–4883, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sarg B, Koutzamani E, Helliger W, Rundquist I, and Lindner HH. Postsynthetic trimethylation of histone H4 at lysine 20 in mammalian tissues is associated with aging. J Biol Chem 277: 39195–39201, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sharpless NE. and DePinho RA. How stem cells age and why this makes us grow old. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 8: 703–713, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shin DM, Kucia M, and Ratajczak MZ. Nuclear and chromatin reorganization during cell senescence and aging - a mini-review. Gerontology 57: 76–84, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Singh L, Brennan TA, Kim J-H, Egan KP, McMillan EA, Chen Q, Hankenson KD, Zhang Y, Emerson SG, Johnson FB, and Pignolo RJ. Brief report: long-term functional engraftment of mesenchymal progenitor cells in a mouse model of accelerated aging. Stem Cells 31: 607–611, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Spinetti G, Wang M, Monticone R, Zhang J, Zhao D, and Lakatta EG. Rat aortic MCP-1 and its receptor CCR2 increase with age and alter vascular smooth muscle cell function. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 24: 1397–1402, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stepanova L. and Sorrentino BP. A limited role for p16Ink4a and p19Arf in the loss of hematopoietic stem cells during proliferative stress. Blood 106: 827–832, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stewart SA. and Weinberg RA. Telomeres: cancer to human aging. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 22: 531–557, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tetz LM, Kamau PW, Cheng AA, Meeker JD, Loch-Caruso R. Troubleshooting the dichlorofluorescein assay to avoid artifacts in measurement of toxicant-stimulated cellular production of reactive oxidant species. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods 67: 56–60, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.van Golen KL, Ying C, Sequeira L, Dubyk CW, Reisenberger T, Chinnaiyan AM, Pienta KJ, and Loberg RD. CCL2 induces prostate cancer transendothelial cell migration via activation of the small GTPase Rac. J Cell Biochem 104: 1587–1597, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yang SE, Ha CW, Jung M, Jin HJ, Lee M, Song H, Choi S, Oh W, and Yang YS. Mesenchymal stem/progenitor cells developed in cultures from UC blood. Cytotherapy 6: 476–486, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zaritsky LA, Gama L, and Clements JE. Canonical type I IFN signaling in simian immunodeficiency virus-infected macrophages is disrupted by astrocyte-secreted CCL2. J Immunol 188: 3876–3885, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.