Abstract

Objective: This study examines the effectiveness and tolerability of stimulants in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and disruptive mood dysregulation disorder (DMDD).

Methods: To be eligible, participants had to meet Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed., Text Revision (DSM-IV) criteria for the combined subtype of ADHD and National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) severe mood dysregulation criteria. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed. (DSM-V) DMDD criteria were retrospectively assessed after the study was completed. An open-label medication trial lasting up to 6 weeks was completed to optimize the central nervous system (CNS) stimulant dose. Measures of affective symptoms, ADHD symptoms and other disruptive behaviors, impairment, and structured side effect ratings were collected before and after the medication trial.

Results: Optimization of stimulant medication was associated with a significant decline in depressive symptoms on the Childhood Depression Rating Score–Revised Scale (p<0.05, Cohen's d=0.61) and Mood Severity Index score (p<0.05, Cohen's d=0.55), but not in manic-like symptoms on the Young Mania Rating Scale. There was a significant reduction in ADHD (p<0.05, Cohen's d=0.95), oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) (p<0.05, Cohen's d=0.5), and conduct disorder (CD) symptoms (p<0.05, Cohen's d=0.65) as rated by parents. There was also a significant reduction in teacher-rated ADHD (p<0.05, Cohen's d=0.33) but not in ODD symptoms. Medications were well tolerated and there was no increase in side effect ratings seen with dose optimization. Significant improvement in functioning was reported by clinicians and parents (all p's<0.05), but youth still manifested appreciable impairment at end-point.

Conclusions: CNS simulants were well tolerated by children with ADHD comorbid with a diagnosis of DMDD. CNS stimulants were associated with clinically significant reductions in externalizing symptoms, along with smaller improvements in mood. However, most participants still exhibited significant impairment, suggesting that additional treatments may be needed to optimize functioning.

Introduction

Persistent nonepisodic irritability is one of the most common presentations in child mental health (Safer 2009). The concept of severe mood dysregulation (SMD) was created by the National Institute for Mental Health (NIMH) to foster the systematic assessment of nonepisodic irritability (Leibenluft 2011). SMD was formalized as mental health disorder in Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed. (DSM-V) as disruptive mood dysregulation disorder (DMDD), with the core criteria of chronic nonepisodic irritability and severe temper outbursts (American Psychiatric Association 2013). Despite the increased study of nonepisodic irritability, little is known about its treatment.

Potential first line treatment options are broad, as DMDD spans externalizing and internalizing spectrums. The lack of evidenced-based interventions for youth with DMDD has been theorized to contribute to the high rates of polypharmacy in children with persistent irritability (Parens and Johnston 2010). To date, the only placebo-controlled medication trial in children with SMD or DMDD found no benefit for lithium over placebo (Dickstein et al. 2009). Antipsychotics and mood stabilizers are effective for reducing aggression in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (Blader et al. 2009; Gadow et al. 2014), However, antipsychotics' capacity to cause marked weight gain and metabolic changes make them a controversial first line choice for a disorder whose estimated prevalence hovers around 3% (Brotman at al. 2006; Parens and Johnston 2010; Copeland et al. 2014). Data on mood stabilizers in children with nonepisodic irritability are mixed, and tolerability concerns also exist surrounding their use in children (Henry et al. 2003; Blader et al. 2009; Dickstein et al. 2009).

Many youth meeting criteria for SMD also have ADHD (Leibenluft 2011; Roy et al. 2014), and the presence of nonepisodic irritability in children with ADHD increases the chance that they will present for treatment compared with ADHD children without comorbid irritability (Anastopoulos et al. 2011). However, it is presently unclear if the initial treatment for children with ADHD and dysregulated moods should be stimulants and behavior therapy targeting the externalizing symptoms or mood-stabilizing medications and atypical antipsychotics targeting irritability and aggression. Many youth with ADHD and persistent irritability are being increasingly prescribed mood stabilizing and antipsychotic medications (Comer et al. 2010; Olfson et al. 2010; Kreider et al. 2014). This trend is concerning given the limited evidence base for these medications in ADHD in combination with a more worrisome side effect profile than that for United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved medications for ADHD (Correll and Carlson 2006). Hence, there is a clear need to establish an evidence-based, treatment algorithm for DMDD, especially in youth with comorbid ADHD, where well-established treatment options exist.

There has been little formal investigation of either the efficacy or the tolerability of CNS stimulants in youth with systematically defined SMD or DMDD. As part of a larger National Institutes of Health (NIH)-funded study examining the development of a novel psychosocial treatment for youth with SMD, we systematically examined the safety and effectiveness of CNS stimulants to determine if they hold promise as an appropriate first line treatment for DMDD. It was hypothesized that CNS stimulants would be well tolerated and lead to a significant reduction in externalizing and internalizing symptoms, with larger effects in the externalizing realm. A secondary goal was to ascertain the degree of residual impairment after ADHD has been stabilized, in order to inform the development of additional treatments for DMDD.

Methods

Participants

The trial was run in two separate waves to accommodate the size limits of the therapy groups in the primary study. Between wave 1 and wave 2 of the study, the research center moved from New York State to Florida; however, identical procedures and many of the same staff were used at both sites. The study was approved by the local institutional review boards (IRBs) at both sites. To be eligible, participants had to meet criteria for the combined subtype of ADHD and SMD as defined by the NIMH (Leibenluft 2011). The combined subtype was required, as it is associated with the highest level of externalizing symptoms as well as with the greatest impairment among ADHD youth (Lahey et al. 2005; Lubke et al. 2007). Exclusionary criteria included an intelligence quotient<80, prominent traits of autism spectrum disorder (ASD), the use of any nonstimulant psychotropic medication, or the presence of full Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. (DSM-IV) criteria for bipolar I/II/not otherwised specified (NOS) (using the definition from Course and Outcome of Bipolar Youth [COBY]) (American Psychiatric Association 1994; Birmaher et al. 2006) or any psychotic disorder. Children meeting full diagnostic criteria for a current major depressive disorder (MDD) or an anxiety disorder requiring pharmacological treatment were also excluded, as were children with active suicidal ideation. Participation in psychosocial treatments at the time of assessment was not exclusionary.

Procedures

Families were recruited through a combination of direct advertisement and referrals from local community mental health clinics. Interested families completed a phone interview to screen for ADHD and SMD symptoms. Written consent was obtained from one or both parents, and the children gave oral assent. Prior to inclusion in the study, participants underwent a physical examination to ensure all children could safely use CNS stimulants. SMD and other DSM-IV mood disorders were evaluated using the mood modules from the Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Aged Children, Washington University version (WASH-U-K-SADS). The WASH-U-KSADS inquires about developmentally appropriate symptoms of pediatric mood disorders and has probes designed to differentiate mood from ADHD symptoms (Geller et al. 1996, 2001). Its depression items specifically query for the frequency, severity, and duration of irritable moods as well as the degree of emotional reactivity, which are core criteria for DMDD and SMD (Leibenluft 2011). Parent interviews were completed by MD/PhD level staff, whereas child assessments were completed by experienced graduate students. Integration of both reports was used to achieve a final composite score, with greater weight given to the reporter deemed most reliable on an item-by-item basis. All raters completed a systematic training course consisting of video reviews and then live assessment in clinical cases (κ>0.9 at the diagnosis level) before completing study ratings.

ADHD, oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), and conduct disorder (CD) were assessed using the Disruptive Behavior Disorders (DBD) Structured Parent Interview (Pelham 1998). The DBD interview assesses the triggers, frequency, and duration of temper outbursts that are required for the presence of DMDD. The presence of ADHD symptoms at school was obtained using the DBD Teacher Rating Scale (Pelham et al. 1992). The K-SADS Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL) was used to assess all other comorbidities. MD/PhD staff confirmed all comorbid diagnoses using best estimate procedures prior to enrollment. The Social Communications Questionnaire (Rutter et al. 2003) was used to define prominent ASD traits leading to exclusion. As the finalized DMDD criterion for DSM-V were not available at study conception (American Psychiatric Association 2013), the DSM-V DMDD criteria were retrospectively assessed after the study was completed using the same diagnostic information described previously (Table 1).

Table 1.

Diagnosis Assessment Methods

| SMD criteria (Leibenluft 2011) | Questions | Scale | Informant |

|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Markedly increased reactivity to negative emotional stimuli manifesting verbally or behaviorally on average at least three times weekly | • Often loses temper Has this been a problem for at least 6 months? |

DBD Parent Interview | Parent |

| • Loses temper: Has there ever been a time when you would get upset easily and lose your temper? Did it take much to get you mad? How often did you get really mad or annoyed and lose your temper? Where do you lose your temper? What do you do when you have a temper tantrum? | K-SADS-PL | Parent Child |

|

| (2) Abnormal mood (anger or sadness), present at least half of the day most days | • Is often angry and resentful Has this been a problem for at least 6 months? |

DBD Parent Interview | Parent |

| • Irritability and anger: Subjective feeling of irritability, anger, crankiness, bad temper, short temper, resentment or annoyance, whether expressed overtly or not. Rate the intensity and duration of such feelings. Was there ever a time when you got annoyed, irritated, or cranky at little things? • Duration of irritable mood |

K-SADS-PL | Parent Child |

|

| (3) Hyperarousal (≥3 of insomnia, agitation, distractibility, racing thoughts or flight of ideas, pressured speech, intrusiveness) | • Easily distracted • Often talks excessively • Often interrupts or intrudes on others Has this been a problem for at least 6 months? |

DBD Parent Interview | Parent |

| • Depressive disorders Insomnia • Bipolar disorder Decreased need for sleep Accelerated, pressured speech or increased amount of speech Racing thoughts Flight of ideas Distractibility |

K-SADS-PL | Parent Child |

|

| (4) Symptoms cause severe impairment in at least one setting (home, school, or with peers) and at least mild impairment in a second setting; | DBD Parent Interview KSADS PL |

Parent | |

| (5) SMD symptom onset must be before age 12 and must be currently present for at least 12 months without symptom-free periods>2 months | DBD Parent Interview KSADS PL |

Parent | |

| (6) Absence of manic or psychotic symptoms. | K-SADS-PL | Parent Child |

|

| (7) Absence of pervasive developmental disorder | Social Communications Questionnaire | Parent | |

| (8) IQ >70 | WISC-IV | Child |

Additional disruptive mood dysregulation disorder (DMDD) criteria: 1) Considered abnormal mood only if irritable or angry, not sad or depressed. 2) Criterion 1 required severe recurrent temper outbursts, three or more times/week. 3) Required age of onset before 10.

SMD, severe mood dysregulation; DBD, disruptive behavior disorder; K-SADS-PL, Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Aged Children – Present and Lifetime Version; IQ, intelligence quotient; WISC-IV, Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, 4th ed.

There is no consensus measure of irritability or mood dysregulation for children (Leibenluft 2011). Therefore, to maximize the chances that participants exhibited abnormalities in mood beyond what is typically seen in children with ADHD and ODD, all participants were also required to have elevated scores on either the Children's Depression Rating Scale - Revised (CDRS-R) (Poznanski and Mikos 1996) or the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) (Young et al. 1978). The YMRS, with scores ranging from 0 to 64, has been found to be a valid measure of change in manic symptoms in children, with acceptable interrater reliability (κ>0.85) (Youngstrom et al. 2002). Likewise, the CDRS, in which scores range from 17 to 177, has been well established as a reliable measure of change in depressive symptoms in children. Both scales are widely used in clinical trials of pediatric mood disorders to quantify treatment effects (Pavuluri et al. 2005). Scores≥12 on the YMRS and ≥28 on the CDRS-R were used to define subthreshold symptoms, as these are the cutoffs for remission on the respective scales. Children with purely a disruptive behavioral disorder typically do not score above these thresholds (Fristad et al. 1992; Waxmonsky et al. 2008). Both measures were administered by MD/PhD level clinicians experienced in the treatment of pediatric mood disorders, using the same methods described previously for the WASH-U-KSADS, to obtain a final composite rating. Prior to joining the study, raters had to complete a systematic training course consisting of scoring of videotaped assessments (κ>0.8 for the final score).

Children not using stimulant medication at intake were allowed to enroll. All other psychotropic medications were stopped prior to study enrollment. Participants were seen weekly by study physicians until the dose was optimized using a combination of symptom, impairment, and side effect ratings obtained from teacher and parents. This open-label trial could last up to 6 weeks. Optimal dose was defined as the tolerable dose leading to the greatest reduction in externalizing symptoms without intolerable side effects. Doses could be lowered at time, for tolerability concerns. Eligible participants entering the therapy trial who were deemed to be on an optimal dose of stimulant by two study physicians were exempted from this phase.

Parental depressive and ADHD symptoms have been found to reduce the efficacy of treatments for their offspring's psychopathology; therefore, both were assessed using standardized rating scales (Brent et al. 1998; Jensen et al. 2007). The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) was used to screen for depression in caretakers (Beck and Steer 1984). Scores≥14 were used to score as elevated depressive symptoms. Each participating caretaker was screened for parental ADHD using the Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale (ASRS) (Murphy and Adler 2004). The ASRS rates all DSM symptoms of ADHD modified to reflect adult manifestations of the disorder. Parents scoring above the identified threshold for six or more symptoms in either domain were deemed as having elevated symptoms of ADHD.

Outcome assessments

Efficacy and tolerability ratings were completed at baseline (week 0) and end-point (week 6). All clinician-rated assessments (i.e., CDRS-R, YMRS, Children's Global Assessment Scale [CGAS]) were completed by MD/PhD level staff experienced in the assessment of childhood mood disorders who had completed the same training procedures as the raters used in the baseline phase. The Disruptive Behavior Disorders Rating Scale (DBD-RS), which measures all DSM-IV symptoms of ADHD, ODD, and CD on a 0–3 Likert scale (Pelham et al. 1992) and the Clinical Global Impressions (CGI) ADHD scale (Guy 1976) served as the ADHD efficacy measures. In accordance with previous studies examining nonepisodic irritability, we computed the irritability subscale score for ODD (Fernandez de la Cruz et al. 2015), which is composed of the items: “is often angry and resentful,” “is often touchy or easily annoyed by others, ” and “often loses temper.” The scores ranged from 0 to 9. In addition, parents reported on their child's domain specific functioning on the Impairment Rating Scale (IRS). The IRS is an eight item visual analogue scale that evaluates the child's problem level and need for treatment in developmentally important areas, such as peer relationships, parent relationships, academic performance, classroom behavior, and self-esteem. Scores>3 indicate clinically appreciable impairment (Fabiano et al. 2006).

The Pittsburgh Side Effect Rating Scale (PSERS), which rates common stimulant-related adverse events as none (0), mild (1), moderate (2), or severe (3), was completed by parents at baseline and end-point (Pelham 1993). PSERS mood score was generated by adding up the following six PSERS items on the parent-reported PSERS: “Worried/anxious,” “Dull, tired, listless,” “Crabby, irritable,” “Tearful, sad, depressed,” “Socially withdrawn,” and “Trouble Sleeping.” The scores could range from 0 to 18.

Teacher completed the IOWA Conners at baseline and end-point (Goyette et al. 1978; Loney and Milich 1982). It was employed instead of the longer DBD-RS because briefer measures of externalizing symptoms have been found to promote completion of scheduled assessments (Pelham et al. 2005). Teachers also completed the ADHD-related impairment section on the teacher version of the IRS.

As subjects were recruited for the broader construct of mood dysregulation rather than for mania or depression, the Mood Severity Index (MSI) (Fristad et al. 2009) was calculated following the procedures used by Fristad in her treatment trial for children with a range of mood disorders {[(CDRS-R score−17)×11/17]+YMRS}. Unlike Fristad, we did not reduce the score on irritability items by half, as irritability is a core construct of DMDD. Clinicians also completed the CGAS, to assess global functioning for an individual on a 0–100 scale at each assessment (Shaffer et al. 1983).

Data analysis

Preliminary analyses examined several variables as potential cofounders, including parental psychopathology, age, gender, ethnicity, medication status at entry, and whether or not the subject was receiving outside counseling services, but none was correlated with change in any of the outcome measures. Therefore, the main analyses consisted of paired t tests to examine differences between baseline and end-point on the MSI score, DBD-RS cluster scores, DSM-V ODD irritability score, IOWA cluster scores, CDRS-R total score, YMRS total score, PSERS ratings, IRS ratings, and CGI severity score. All t tests were two tailed with significance set at p<0.05. Standardized mean difference effect sizes (Cohen's d) of CNS stimulants were then computed by calculating differences between the baseline and end-point means and dividing the results by pooled standard deviations. The linear relationship between change in MSI score and parent-rated DBD-RS score was determined with Pearson correlations to examine if change in externalizing symptoms was associated with change in internalizing symptoms.

Results

Study flow

There were 68 participants enrolled in in the primary study, with 65 entering the medication phase. An additional participant was removed after intake when it was determined that that person no longer met SMD/DMDD criteria because of the detection of prominent traits of ASD. Among these 64, 41 (64%) participants had their CNS stimulant adjusted, with the rest being deemed to be on their optimal dose at study entry. Only three (7%) of these participants failed to meet full DMD-V criteria for DMDD, primarily because of having fewer than three severe outbursts per week. Only participants meeting DMDD criteria (n=38) who had their stimulant dose adjusted are included in the effectiveness analysis. Inclusion of the three cases not meeting criteria for DMDD did not appreciably impact results. Sixteen (42%) of these participants were stimulant naïve at entry.

The average age of participants at entry was 9.4. More than a quarter of the participants were of minority racial or ethnic status, with 28% of the total sample being female. Participants were predominantly from middle class households (Hauser and Warren 1997). The majority of participants were actively engaged in community based counseling services and had previously used ADHD medications. None of the participants met criteria for a current mood disorder or nonphobic anxiety, although several had previously met criteria for depression or an anxiety disorder. More than half (55%) of parents had either active mood or ADHD symptoms (Table 2). However, no differences in treatment response or tolerability were seen in children with versus those without elevated symptoms of depression or ADHD.

Table 2.

Subject Characteristics

| Intake | |

|---|---|

| n | 38 |

| Age mean (SD) | 9.4 (1.7) |

| Male (%) | 27 (72%) |

| Racial/ethnic minority (%) | 10 (26.3%) |

| IQ mean (SD) | 100.3 (12.1) |

| Medicated for ADHD at entry (%) | 22 (58%) |

| Using outside counseling services (%) | 23 (61%) |

| With parental ADHD symptoms (ASRS) (%) | 15 (40%) |

| With parental depressive symptoms (BDI) (%) | 13 (34%) |

| aSocioeconomic index mean (SD) | 42.7 (16.5) |

Calculated using method from Hauser and Warren, 1997.

SD, standard deviation; IQ, intelligence quotient; ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; ASRS, Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory.

In participants who were switched from one class of stimulant to another class of stimulant (n=11), mean doses decreased from baseline (0.86 mg/kg/day of methylphenidate [MPH] equivalents) to end-point (0.78 mg/kg/day of MPH equivalents). In participants whose stimulant class was not changed (n=11), mean doses at baseline (0.78 mg/kg/day) increased to 1.03 mg/kg/day of MPH equivalents. In stimulant-naïve participants, mean dose was 0.71 mg/kg/day of MPH equivalents at end-point.

Mood symptoms

Baseline mood ratings were consistent with a mild to moderate level of manic-like and depressive symptoms (Table 3). Optimization of CNS stimulant dose was associated with a significant decline in CDRS–R from baseline (mean=34.3[5.8]) to end-point (mean=30.9[5.3], effect size=0.29, t=4.5, p<0.05). Reduction in YMRS score was nonsignificant (mean=13[4.3]) to end-point (mean=12[4.4], effect size=0.12, t=1.5, p=0.14). The decline of the MSI score was significant from baseline (mean=24.2 6]) to end-point (mean=21[5.6], effect size=0.26, t=3.3, p<0.05). There was no significant difference (p<0.05) in the degree of change in CDRS-R, YMRS, and MSI scores in stimulant-naïve (n=16) versus previously medicated participants (n=22).

Table 3.

Change in Mood, DBD-RS, IOWA, CGI, CGAS, and TIRS Scores from Baseline to End-Point (n=38)

| Measure | Baseline mean (SD) | End-point mean (SD) | p value | ES |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CDRS – R | 34.3 (5.8) | 30.9 (5.3) | <0.001 | 0.29 |

| YMRS | 13 (4.3) | 12 (4.4) | 0.14 | 0.12 |

| MSI | 24.2 (6) | 21 (5.6) | <0.001 | 0.26 |

| DBD-RS Parent ADHD | 35.2 (8.5) | 26.3 (10.2) | <0.001 | 0.43 |

| DBD-RS Parent ODD | 14.5 (5.1) | 11.9 (5.4) | <0.001 | 0.24 |

| DBD-RS Parent CD | 5.3 (3.1) | 3.3 (3.1) | <0.001 | 0.3 |

| DSM -V ODD irritability | 5.9 (2.2) | 4.6 (2.3) | <0.001 | 0.29 |

| IOWA Teacher I/O | 7.9 (4.1) | 6.6 (3.8) | 0.04 | 0.17 |

| IOWA Teacher ODD | 5.4 (4.4) | 4.3 (4.5) | 0.12 | 0.13 |

| CGI-S ADHD | 4.4 (0.5) | 3.8 (0.6) | <0.001 | 0.48 |

| CGAS | 54.6 (4.9) | 56.8 (5.8) | 0.03 | −0.2 |

| TIRS Item 1 | 3.4 (1.3) | 3.3 (1.4) | 0.44 | 0.04 |

| TIRS Item 2 | 2.7 (1.5) | 2.6 (1.5) | 0.65 | 0.03 |

| TIRS Item 3 | 3.8 (1.3) | 3.5 (1.3) | 0.16 | 0.11 |

| TIRS Item 4 | 3.6 (1.2) | 3.3 (1.2) | 0.14 | 0.12 |

| TIRS Item 5 | 3.4 (1.3) | 3.1 (1.5) | 0.17 | 0.11 |

| TIRS Item 6 | 3.7 (1.1) | 3.4 (1.2) | 0.1 | 0.13 |

SD, standard deviation; CDRS–R, Childhood Depression Rating Score–Revised; YMRS, Young Mania Rating Scale Total Score; MSI, Mood Severity Index (Fristad et al. 2009); DBD-RS, Disruptive Behavior Disorders Rating Scale; ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; ODD, oppositional defiant disorder; CD, conduct disorder; DSM-V, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; IOWA, IOWA Conners Rating Scale; I/O, Inattentive/Overactive subscale; CGI-S, Clinical Global Impressions - Severity scale; CGAS, Children's Global Assessment Scale; TIRS, Teacher Impairment Rating Scale (Range 1–5) (1, Definitely Not a Problem, 2, Probably Not, 3, Maybe, 4, Probably Yes, 5, Definitely Yes a Problem); Item 1, relationship with other children; Item 2, relationship with teacher; Item 3, academic progress; Item 4, self-esteem; Item 5, classroom functioning; Item 6, need for additional treatment/services.

There were no cases of new onset mania or suicidal ideation. Two participants (5.3%) no longer met criteria of DMDD at the end of the study. All three participants who met criteria for SMD but not DMDD at study entry no longer met criteria for either disorder after their CNS dose was optimized.

Behavioral symptoms

‘Baseline parent ratings were consistent with a moderate level of ADHD and ODD symptoms and a mild intensity of CD symptoms (Table 3). There was significant decline in the parent-rated DBD-RS ADHD score (effect size=0.43, t=6.2, p<0.05), ODD score (effect size=0.24, t=4.2, p<0.05), and CD score (effect size=0.3, t=6.0, p<0.05). A significant and comparable decline to the total score was seen for the DSM-V ODD irritability subscale (mean=5.9[2.2]) to end-point (mean=4.6[2.3], effect size=0.29, t=5.1, p<0.05). Change in mood symptoms as measured by the MSI did not correlate with change in total behavioral symptoms as measured by the DBD-RS total score (rp=0.11, p=0.49).

Baseline teacher ratings showed a moderate level of ADHD symptoms but only mild intensity of ODD symptoms, in contrast to parent ratings. There was significant decline for teacher-rated IOWA I/O score (effect size=0.17, t=2.1, p<0.05) but not for ODD score (effect size=0.13, t=1.66, p=0.12).

Comparisons of observed effects in treatment-naïve (n=16) versus previously medicated participants (n=22) revealed larger improvements in naïve youth in parent-rated ADHD (effect size=0.56 vs. 0.34) and ODD scores (effect size=0.35 vs. 0.19). Little difference was noted in teacher ratings of ADHD (I/O score [effect size=0.19 vs. 0.14] and ODD [effect size=0.17 vs. 0.11]).

Global improvement and impairment

At study entry, children presented with an appreciable level of global and domain-specific impairment as measured on the CGAS and IRS respectively. Total impairment rated by the clinicians using the CGAS improved from baseline (mean=54.6[4.9]) to end-point (mean=56.8[5.8], effect size=−0.2, t=−2.3, p=0.03) (Table 3).

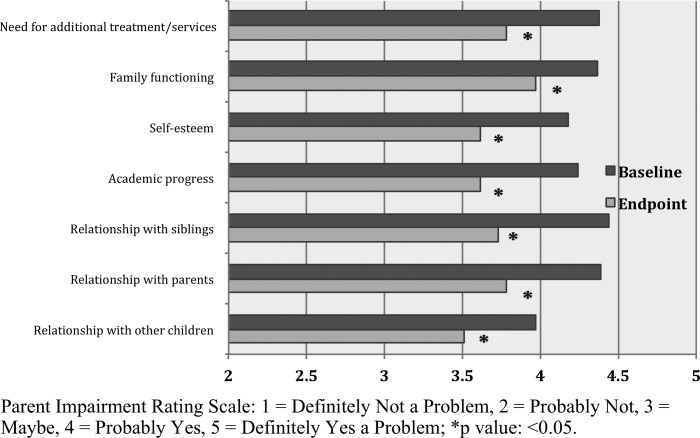

Parents reported more impairment on the IRS than did teachers (mean score 4.3 vs. 3.5). Optimization of CNS stimulant dose was associated with significant improvement in parent-reported impairment in all measured domains (Fig. 1). Effect sizes were moderate (>0.4) in all domains except for family functioning (0.36). In contrast to parents' ratings, there was no significant change in teacher-rated impairment (Table 3).

FIG. 1.

Parent rating on the Impairment Rating Scale.

Tolerability

There was significant decline in the crabby/irritable score on the parent-rated PSERS from baseline (mean=1.4[0.9]) to end-point (mean=1.1[0.8], t=2.1, p<0.05). No significant changes were seen in any other category, with no individual side effect increasing in severity (Table 4). Comparisons of observed side effects in treatment-naïve (n=16) versus previously medicated participants (n=22) revealed no significant difference in mean changes in total score (1 vs. 0.01), mood score (0.7 vs. 1.1), or each item except for loss of appetite (−0.62 vs. 0.5, t=3.8, p<0.05) and stomachache (−0.4 vs. 0.1, t=2.2, p<0.05), with greater severity seen in naïve youth.

Table 4.

Side Effect Ratings

| PSERS | Baseline Mean (SD) | End-point Mean (SD) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| PSERS Total Score | 7.5 (4.2) | 6.9 (4.2) | 0.45 |

| PSERS Mood Score | 4.8 (2.7) | 4 (3) | 0.15 |

| Motor tics | 0.05 (0.2) | 0.2 (0.5) | 0.06 |

| Buccal-lingual movements | 0.08 (0.4) | 0.2 (0.5) | 0.25 |

| Picking at skin or fingers, nail biting, lip or cheek chewing | 0.95 (0.84) | 0.82 (0.93) | 0.34 |

| Worried/anxious | 0.95 (0.84) | 0.82 (0.87) | 0.40 |

| Dull, tired, listless | 0.5 (0.7) | 0.4 (0.6) | 0.59 |

| Headaches | 0.3 (0.6) | 0.4 (0.7) | 0.62 |

| Stomachache | 0.4 (0.7) | 0.5 (0.7) | 0.30 |

| Crabby, irritable | 1.4 (0.9) | 1.1 (0.8) | 0.04* |

| Tearful, sad, depressed | 0.7 (0.8) | 0.5 (0.7) | 0.24 |

| Socially withdrawn | 0.5 (0.7) | 0.4 (0.7) | 0.60 |

| Hallucinations | 0.1 (0.4) | 0.08 (0.4) | 0.57 |

| Loss of appetite | 0.9 (1.1) | 0.9 (0.7) | 1 |

| Trouble sleeping | 0.7 (0.9) | 0.7 (0.7) | 0.87 |

p value: <0.05.

SD, standard deviation; PSERS Total Score, Pittsburgh Side Effect Rating Scale – Total Score (range 0–39); PSERS Mood Score, Pittsburgh Side Effect Rating Scale – Mood Score (range (0–18; addition of the following six PSERS items “Worried/anxious,” “Dull, tired, listless,” “Crabby, irritable,” “Tearful, sad, depressed,” “Socially withdrawn,” and “Trouble sleeping”); PSERS Item: 0=None, 1=Mild, 2=Moderate, 3=Severe.

Two children, who had both previously used atypical antipsychotics for behavioral concerns, were prescribed antipsychotics for increasing aggression by nonstudy physicians during the course of the study. Neither case is included in the effectiveness analysis because one never had the stimulant dose adjusted and the second was removed from the study because of the detection of prominent autistic spectrum behaviors. In both cases, there was no clear temporal association between the use of a CNS stimulant and increasing irritability, with the same CNS stimulant medications being continued at the same dose after the prescription of the atypical antipsychotics. A third child dropped out of the medication phase prior to collection of any effectiveness data, because of complaints of blurry vision with the study-prescribed CNS stimulant.

Discussion

Over the past decade, there has been increasing investigation into the prevalence, prognosis, and etiology of nonepisodic irritability in children (Leibenluft 2011; Copeland et al. 2014). However, comparatively little work has focused on the treatment of this condition despite clear evidence that children with severe nonepisodic irritability present with significant impairments across multiple settings (Anastopoulos et al. 2001; Leibenluft et al. 2003; Waxmonsky et al. 2008; Roy et al. 2014). As DMDD and the related construct of SMD tend to commonly co-occur with ADHD, it is important to examine the efficacy and tolerability of evidence-based ADHD treatments in this population. However, there has not been any formal investigation into their safety and efficacy in youth systematically diagnosed with DMDD.

Using standardized ratings collected at regular intervals from parents and teachers, we observed significant but relatively modest improvements in parent-rated ADHD symptoms, especially for an open-label trial in which effect sizes may be inflated by expectancy effects. In comparison, controlled trials of CNS stimulants in non-DMDD youth using comparable ratings have found large effects for ADHD (Greenhill et al. 2002; Pliszka et al. 2007) and moderate effects for ODD (Spencer et al. 2006). These results suggest that, similar to youth with ASD (Aman et al. 2005), those with DMDD may exhibit reduced responsiveness to CNS stimulants. However, results could also have been impacted by the fact that the majority of youth were already medicated at a typically effective dose of stimulant at study entry (Greenhill et al. 2002). Even though observed effects were almost double in stimulant-naïve youth, results were still appreciably less than what has been traditionally observed in controlled trials, suggesting that DMDD symptoms may be associated with a reduced response. In addition, the majority of participants had a parent with elevated symptoms of ADHD or MDD, which has been found to reduce rates of response to CNS stimulants (Hoza et al. 2000; Owens et al. 2003; Jensen et al. 2007). However, in this analysis, parental psychopathology does not impact results, again pointing to the presence of DMDD as a plausible cause for the reduced degree of improvement. Improvements in teacher-rated symptoms were even less, but may have been impacted by the milder level of baseline symptoms. Future work should examine the efficacy of CNS stimulants in DMDD youth under blinded and randomized conditions.

It is worth noting that improvements were seen with smaller doses when medication class was switched versus when only the dose was changed. Results suggest the value of switching stimulant class rather than escalating to the maximum tolerable dose in children with DMDD who exhibit partial responses to therapeutic doses of CNS stimulants. It is also noteworthy that all three participants who met the criteria for SMD but not DMDD no longer met the criteria for either disorder at end of the study. In contrast, only 5% of DMDD participants remitted by study end-point. Although preliminary, results suggest that DMDD may represent a more stable construct than SMD in youth with ADHD. The findings also emphasize the importance of waiting to make a diagnosis of DMDD in ADHD youth until treatment has been initiated.

Mild improvements in mood symptoms were seen over the course of the trial, suggesting that CNS stimulants can be safely used in this population. However, for an open trial, the observed reductions in mood symptoms are small, and suggest that additional interventions may be needed for ADHD youth with prominent affective symptomatology. Results are consistent with the published work on CNS stimulants' capacity to improve mood dysregulation in ADHD (Shaw et al. 2014). Furthermore, change in externalizing symptoms does not appear to be predictive of change in mood symptoms, necessitating reassessment of both symptom domains after initiation of medication treatment for ADHD.

Impairment findings are consistent with prior reports documenting appreciably disturbed functioning across a wide range of domains in youth with nonepisodic irritability, with greater impairment at home than at school (Thuppal et al. 2002; Waxmonsky et al. 2008; Anastopoulos et al. 2011). Clinically meaningful gains in the participants' relationship with their parents, family, and peers, as well as parent-rated academic progress and self-esteem were seen. However, little impact was seen on teachers' ratings of impairment, and end-point CGAS scores were indicative of high levels of residual global impairment. Results suggest that medication treatment of ADHD is not sufficient by itself to optimize functioning in youth with DMDD and ADHD.

Medication was well tolerated, with most side effect ratings decreasing from baseline to end-point, especially those with a mood component (e.g., sleep, anxiety, irritability). These encouraging tolerability results suggest that CNS stimulants can be safely used in most children with DMDD. Two children did progress to use of antipsychotics for increasing aggressive behaviors, both with a prior history of antipsychotic usage. In both cases, there was not a clear association between CNS stimulant use and increased aggression, suggesting that symptom exacerbations more likely stemmed from issues regarding suboptimal effectiveness than from intolerability. Nonetheless, response to CNS stimulants should be monitored closely in youth with DMDD, especially in those with a prior history of antipsychotic usage.

The combination of stimulant medication and behavioral parent training has proven effective for reducing aggression in children with ADHD. In the Multimodal Treatment Study of Children with ADHD (MTA), participants with ADHD, ODD, and internalizing symptoms, as well as those with manic-like symptoms, were most responsive to treatments integrating pharmacological and behavioral modalities (Jensen et al. 2001; Galanter et al. 2005). A prior study by our group examined the impact of intensive behavioral services plus stimulant medication in children with SMD and found the combination to be effective, with larger gains seen than that reported here (Waxmonsky et al. 2008). Future work should investigate the effects of combination treatment with CNS stimulants and specialized psychosocial therapies targeting mood dysregulation in youth with DMDD and ADHD.

Limitations

The primary limitation of this study is its open label design, as expectancy bias may have inflated observed treatment effects. Results, particularly that of reduced effectiveness for CNS stimulants in children with DMDD, require confirmation under controlled settings. In addition, prior psychotropic medications were not discontinued prior to baseline ratings, unlike in many CNS stimulant trials. However, this practice is consistent with clinical care, in which decisions are more likely to focus on comparing one medication to another than on comparing a medication against the unmedicated state. We saw little difference in side effect rates and change in mood symptoms between medicated and treatment-naïve participants, suggesting that prior medication status did not dramatically impact tolerability results. Still, it is important to recognize that use of a medicated baseline state could have impacted effectiveness and tolerability findings.

Diagnosis of SMD was ascertained through a systematic multimethod assessment battery integrating clinician, child, and parent reports. All but three cases met criteria for DMDD, and inclusion of the SMD only cases did not appreciably impact results. There is no gold standard measure for either irritability or mood dysregulation that has been found to reliably detect treatment effects (Leibenluft 2011). Therefore, as with other trials of nonepisodic irritability (Dickstein et al. 2009; Blader et al. 2010) we employed the CDRS and YMRS, as both scales have been found to reliably detect change in mood symptoms in children. However, it is important to recognize that these measures were not designed to specifically assess irritability. Lastly, this trial was run in the specialty mental health research center, and participants were predominantly Caucasian males from middle class families, limiting the ability to generalize findings.

Conclusions

Results from this open label study of CNS stimulants in children with ADHD and DMDD suggest that optimizing CNS stimulant dose is well tolerated and leads to mild to moderate improvements in externalizing symptoms and parent-rated impairment. Smaller effects were observed in teachers rated behavioral problems and for internalizing symptoms. CNS stimulants appear to be a reasonable first line treatment for youth with ADHD and DMDD. However, the limited gains and large degree of residual impairment suggest that additional treatments may be needed, and emphasizes the need to develop specific treatments for youth with DMDD.

Clinical Significance

CNS simulants are well tolerated by children with ADHD and DMDD, producing clinically significant improvements. However, additional treatments are needed to optimize functioning.

Disclosures

In the past 3 years, Dr. Waxmonsky has received research funding from Janssen (drug donation), NIMH, and Shire Pharmaceuticals; served on the advisory board for Noven Pharmaceuticals, and served as a speaker for continuing medical education (CME) talks provided by Quintiles. Dr. Pelham has served on the advisory board for Noven Pharmaceuticals. Drs. Baweja, Humphrey, Babocsai, Pariseau, Waschbusch, Hoffman, Akinnusi, and Haak, and Mr. Belin have no conflicts of interest or financial ties to report.

References

- Aman MG, Arnold LE, Ramadan Y, Witwer A, Lindsay R, McDougle CJ, Posey DJ, Swiezy N, Kohn A, McCracken JT, Shah B, Cronin P, McGough J, Lee JSY, Scahill L, Martin A, Koenig K, Carroll D, Young C, Lancor A, Tierney E, Ghuman J, Gonzalez NM, Grados M, Vitiello B, Ritz L, Chuang S, Davies M, Robinson J, McMahon D: Randomized, controlled, crossover trial of methylphenidate in pervasive developmental disorders with hyperactivity. Arch Gen Psychiatry 62:1266–1274, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994 [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013 [Google Scholar]

- Anastopoulos AD, Smith TF, Garrett ME, Morrissey-Kane E, Schatz NK, Sommer JL, Kollins SH, Ashley-Koch A: Self-Regulation of emotion, functional impairment, and comorbidity among children with AD/HD. J Atten Disord 15:583–592, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA: Internal consistencies of the original and revised Beck Depression Inventory. J Clin Psychol 40:1365–1367, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birmaher B, Axelson D, Strober M, Gill MK, Valeri S, Chiappetta L, Ryan N, Leonard H, Hunt J, Iyengar S, Keller M: Clinical course of children and adolescents with bipolar spectrum disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry 63:175–183, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blader JC, Pliszka SR, Jensen PS, Schooler NR, Kafantaris V: Stimulant-responsive and stimulant-refractory aggressive behavior among children with ADHD. Pediatrics 126:e796–806, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blader JC, Schooler NR, Jensen PS, Pliszka SR, Kafantaris V: Adjunctive divalproex versus placebo for children with ADHD and aggression refractory to stimulant monotherapy. Am J Psychiatry 166:1392–1401, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brent DA, Kolko D, Birmaher B, Baugher M, Bridge J, Roth C, Holder D: Predictors of treatment efficacy in a clinical trial of three psychosocial treatments for adolescent depression. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 37:906–914, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brotman MA, Schmajuk M, Rich BA, Dickstein DP, Guyer AE, Costello EJ, Egger HL, Angold A, Pine DS, Leibenluft E: Prevalence, clinical correlates, and longitudinal course of severe mood dysregulation in children. Biol Psychiatry 60: 991–997, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comer JS, Olfson M, Mojtabai R: National trends in child and adolescent psychotropic polypharmacy in office-based practice, 1996–2007. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 49:1001–1010, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland WE, Shanahan L, Egger H, Angold A, Costello EJ: Adult diagnostic and functional outcomes of DSM-5 disruptive mood dysregulation disorder. Am J Psychiatry 171:668–674, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correll CU, Carlson HE: Endocrine and metabolic adverse effects of psychotropic medications in children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 45:771–791, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickstein DP, Towbin KE, Van Der Veen JW, Rich BA, Brotman MA, Knopf L, Onelio L, Pine DS, Leibenluft E: Randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial of lithium in youths with severe mood dysregulation. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 19:61–73, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabiano GA, Pelham WE, Waschbusch DA, Gnagy EM, Lahey BB, Chronis AM, Onyango AN, Kipp H, Lopez–Williams A, Burrows–Maclean L: A practical measure of impairment: psychometric properties of the impairment rating scale in samples of children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and two school-based samples. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 35:369–385, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez de la Cruz L, Simonoff E, McGough JJ, Halperin JM, Arnold LE, Stringaris A: Treatment of children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and irritability: Results From the Multimodal Treatment Study of Children with ADHD (MTA). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 54:62–70, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fristad MA, Verducci JS, Walters K, Young ME: Impact of multifamily psychoeducational psychotherapy in treating children aged 8 to 12 years with mood disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry 66:1013–1021, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fristad MA, Weller EB, Weller RA: The Mania Rating Scale: Can it be used in children? A preliminary report. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 31:252–257, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadow KD, Arnold LE, Molina BS, Findling RL, Bukstein OG, Brown NV, McNamara NK, Rundberg–Rivera EV, Li X, Kipp HL, Schneider J, Farmer CA, Baker JL, Sprafkin J, Rice RR, Bangalore SS, Butter EM, Buchan–Page KA, Hurt EA, Austin AB, Grondhuis SN, Aman MG: Risperidone added to parent training and stimulant medication: Effects on attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, conduct disorder, and peer aggression. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 53:948–959, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galanter CA, Pagar DL, Davies M, Li W, Carlson G, Abikoff HB, Arnold LE, Bukstein OG, Pelham W, Elliott GR, Hinshaw S, Epstein JN, Wells K, Hechtman L, Newcorn JH, Greenhill L, Wigal T, Swanson JM, Jensen PS: ADHD and manic symptoms: Diagnostic and treatment implications. Clin Neurosci Res 5:283–294, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- Geller B, Williams M, Zimmerman B, Frazier J: Washington University in St. Louis Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (WASH-K-KSADS). St. Louis: Washington University; 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geller B, Zimerman B, Williams M, Bolhofner K, Craney JL, DelBello MP, Soutullo C: Reliability of the Washington University in St. Louis Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (WASH-U-KSADS) mania and rapid cycling sections. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 40: 450–455, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goyette CH, Conners CK, Ulrich RF: Normative data on revised Conners Parent and Teacher Rating Scales. J Abnorm Child Psychol 6:221–236, 1978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenhill LL, Pliszka S, Dulcan MK, Bernet W, Arnold V, Beitchman J, Benson RS, Bukstein O, Kinlan J, McClellan J, Rue D, Shaw JA, Stock S: Parameter for the use of stimulant medications in the treatment of children, adolescents, and adults. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 41:26S–49S, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guy W: ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology, revised. United States Department of Health, Education, and Welfare publication (ADM) 76–338. Rockville, MD: National Institute of Mental Health; 1976 [Google Scholar]

- Hauser RM, Warren JR: Socioeconomic indexes for occupations: A review, update, and critique. Sociol Methodol 27:177–298, 1997 [Google Scholar]

- Henry CA, Zamvil LS, Lam C, Rosenquist KJ, Ghaemi SN: Long-term outcome with divalproex in children and adolescents with bipolar disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 13:523–529, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoza B, Owens JS, Pelham WE, Swanson JM, Conners CK, Hinshaw SP, Arnold LE, Kraemer HC: Parent cognitions as predictors of child treatment response in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Abnorm Child Psychol 28:569–583, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen PS, Arnold LE, Swanson JM, Vitiello B, Abikoff HB, Greenhill LL, Hechtman L, Hinshaw SP, Pelham WE, Wells KC, Conners CK, Elliott GR, Epstein JN, Hoza B, March JS, Molina BS, Newcorn JH, Severe JB, Wigal T, Gibbons RD, Hur K: 3-year follow-up of the NIMH MTA study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 46:989–1002, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen PS, Hinshaw SP, Kraemer HC, Lenora N, Newcorn JH, Abikoff HB, March JS, Arnold LE, Cantwell DP, Conners CK, Elliott GR, Greenhill LL, Hechtman L, Hoza B, Pelham WE, Severe JB, Swanson JM, Wells KC, Wigal T, Vitiello B: ADHD comorbidity findings from the MTA study: Comparing comorbid subgroups. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 40:147–158, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreider AR, Matone M, Bellonci C, dosReis S, Feudtner C, Huang YS, Localio R, Rubin DM: Growth in the concurrent use of antipsychotics with other psychotropic medications in Medicaid-enrolled children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 53:960–970, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahey BB, Pelham WE, Loney J, Lee SS, Willcutt E: Instability of the DSM-IV subtypes of ADHD from preschool through elementary school. Arch Gen Psychiatry 62:896–902, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leibenluft E: Severe mood dysregulation, irritability, and the diagnostic boundaries of bipolar disorder in youths. Am J Psychiatry 168:129–142, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leibenluft E, Blair RJ, Charney DS, Pine DS: Irritability in pediatric mania and other childhood psychopathology. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1008:201–218, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loney J, Milich R: Hyperactivity, inattention, and aggression in clinical practice. In: Advances in Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, Vol. 3, edited by Wolraich M., Routh D.K. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press, 113–147, 1982 [Google Scholar]

- Lubke GH, Muthen B, Moilanen IK, McGough JJ, Loo SK, Swanson JM, Yang MH, Taanila A, Hurtig T, Järvelin MR, Smalley SL: Subtypes versus severity differences in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in the Northern Finnish birth cohort. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 46:1584–1593, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy KR, Adler LA: Assessing attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adults: Focus on rating scales. J Clin Psychiatry 65 Suppl 3:12–17, 2004 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olfson M, Crystal S, Huang C, Gerhard T: Trends in antipsychotic drug use by very young, privately insured children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 49:13–23, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens EB, Hinshaw SP, Kraemer HC, Arnold LE, Abikoff HB, Cantwell DP, Conners CK, Elliott G, Greenhill LL, Hechtman L, Hoza B, Jensen PS, March JS, Newcorn JH, Pelham WE, Severe JB, Swanson JM, Vitiello B, Wells KC, Wigal T: Which treatment for whom for ADHD? Moderators of treatment response in the MTA. J Consult Clin Psychol 71:540–552, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parens E, Johnston J: Controversies concerning the diagnosis and treatment of bipolar disorder in children. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 4:1–14, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavuluri MN, Birmaher B, Naylor MW: Pediatric bipolar disorder: A review of the past 10 years. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 44:846–871, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelham WE: Disruptive Behavior Disorders Interview. Buffalo: Comprehensive Treatment of ADHD; 1998 [Google Scholar]

- Pelham W: Pharmacotherapy for children with ADHD. School Psych Rev 22:199–227, 1993 [Google Scholar]

- Pelham WE, Fabiano GA, Massetti GM: Evidence-based assessment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 34:449–476, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelham WE, Gnagy EM, Greenslade KE, Milich R: Teacher ratings of DSM-III-R symptoms for the disruptive behavior disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 31:210–218, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pliszka SR, Bernet W, Bukstein O, Walter HJ, Arnold V, Beitchman J, Benson RS, Chrisman A, Farchione T, Hamilton J, Keable H, Kinlan J, McClellan J, Rue D, Schoettle U, Shaw JA, Stock S: The American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) Work Group on Quality Issues. Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with attention- deficit–hyperactivity disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 46:894–921, 2007. 17581453 [Google Scholar]

- Poznanski EO, Mikos H: Children Depression Rating Scale–Revised (CDRS-R). Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services; 1996 [Google Scholar]

- Roy AK, Lopes V, Klein RG: Disruptive mood dysregulation disorder: A new diagnostic approach to chronic irritability in youth. Am J Psychiatry 171:918–924, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M, Bailey A, Lord C: The social communication questionnaire: Manual. Western Psychological Services, Los Angeles, CA; 2003 [Google Scholar]

- Safer DJ: Irritable mood and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 3:35, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer D, Gould MS, Brasic J, Ambrosini P, Fisher P, Bird H, Aluwahlia S: A children's global assessment scale (CGAS). Arch Gen Psychiatry 40:1228–1231, 1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw P, Stringaris A, Nigg J, Leibenluft E: Emotion dysregulation in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am J Psychiatry 171:276–293, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer TJ, Abikoff HB, Connor DF, Biederman J, Pliszka SR, Boellner S, Read SC, Pratt R: Efficacy and safety of mixed amphetamine salts extended release (Adderall XR) in the management of oppositional defiant disorder with or without comorbid attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in school-aged children and adolescents: A 4-week, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, placebo-controlled, forced-dose-escalation study. Clin Ther 28:402–418, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thuppal M, Carlson GA, Sprafkin J, Gadow K: Correspondence between adolescent report, parent report, and teacher report of manic symptoms. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 12:27–35, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waxmonsky J, Pelham WE, Gnagy E, Cummings MR, O'Connor B, Majumdar A, Verley J, Hoffman MT, Massetti GA, Burrows–MacLean L, Fabiano GA, Waschbusch DA, Chacko A, Arnold FW, Walker KS, Garefino AC, Robb JA: The efficacy and tolerability of methylphenidate and behavior modification in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and severe mood dysregulation. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 18:573–588, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young RC, Biggs JT, Ziegler VE, Meyer DA: A rating scale for mania: Reliability, validity and sensitivity. Br J Psychiatry 133:429–435, 1978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youngstrom EA, Danielson CK, Findling RL, Gracious BL, Calabrese JR: Factor structure of the Young Mania Rating Scale for use with youths ages 5 to 17 years. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 31:567–572, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]