Abstract

Objective: Diagnostic criteria for disruptive mood dysregulation disorder (DMDD) require 1) periodic rageful outbursts and 2) disturbed mood (anger or irritability) that persists most of the time in between outbursts. Stimulant monotherapy, methodically titrated, often culminates in remission of severe aggressive behavior, but it is unclear whether those with persistent mood symptoms benefit less.This study examined the association between the presence of persistent mood disturbances and treatment outcomes among children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and periodic aggressive, rageful outbursts.

Methods: Within a cohort of children with ADHD and aggressive behavior (n = 156), the prevalence of persistent mood symptoms was evaluated at baseline and after completion of a treatment protocol that provided stimulant monotherapy and family-based behavioral treatment (duration mean [SD] = 70.04 [37.83] days). The relationship of persistent mood symptoms on posttreatment aggressive behavior was assessed, as well as changes in mood symptoms.

Results: Aggressive behavior and periodic rageful outbursts remitted among 51% of the participants. Persistent mood symptoms at baseline did not affect the odds that aggressive behavior would remit during treatment. Reductions in symptoms of sustained mood disturbance accompanied reductions in periodic outbursts. Children who at baseline had high irritability but low depression ratings showed elevated aggression scores at baseline and after treatment; however, they still displayed large reductions in aggression.

Conclusions: Among aggressive children with ADHD, aggressive behaviors are just as likely to decrease following stimulant monotherapy and behavioral treatment among those with sustained mood symptoms and those without. Improvements in mood problems are evident as well. Therefore, the abnormalities in persistent mood described by DMDD's criteria do not contraindicate stimulant therapy as initial treatment among those with comorbid ADHD. Rather, substantial improvements may be anticipated, and remission of both behavioral and mood symptoms seems achievable for a proportion of patients.

Trial Registration: ClinicalTrials.gov (U.S.); IDs: NCT00228046 and NCT00794625; www.clinicaltrials.gov

Introduction

Chronic rageful outbursts following minimal provocation are among the leading reasons children are seen for mental health services. Nevertheless, characterizing this clinical presentation within available diagnostic concepts has eluded consensus. Brittle frustration tolerance and affective volatility are prevalent among children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Some consider these emotion-related features integral to ADHD's hyperactive/impulsive components even though they are not part of current diagnostic criteria (Nigg and Casey 2005; Sagvolden et al. 2005; Barkley 2015). A subgroup of youth with ADHD and heightened irritability may be distinguished on psychometric, autonomic, and central neural indices (Karalunas et al. 2014). Frequent loss of temper and anger displays are also highly prevalent symptoms of oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) (Stringaris and Goodman 2009; Althoff et al. 2014; Burke et al. 2014). ADHD and ODD are common in samples of children with rage outbursts and irritability in clinical (Leibenluft 2011; Axelson et al. 2012) and some community (Althoff et al. 2014) samples. However, because dysregulated affect is not always a feature of ADHD or ODD, concern arose that these diagnoses underemphasized the affective disturbance these patients' lability and explosiveness suggest.

Consequently, for some years, it became common to diagnose this presentation as a form of bipolar disorder (BD). This practice acutely inflated the incidence of BD diagnoses among youth in United States clinical settings (Moreno et al. 2007; Blader 2011). However, preadolescents only rarely present with demarcated episodes of mood disturbance that signify deterioration from their usual functioning, as BD's diagnostic criteria require. There were also concerns that other criteria of BD were stretched beyond their traditional meaning to cover behavioral problems among children that other common childhood disorders or developmental variations describe (Blader and Carlson 2007, 2013).

Disruptive mood dysregulation disorder (DMDD) is intended partly to provide an alternative rubric for chronic, non-episodic negative emotional reactivity (American Psychiatric Association 2013). However, DMDD's requirement for chronically irritable or angry mood that persists between rageful outbursts distinguishes a subgroup of those with temper dyscontrol, because the majority of children with such outbursts are euthymic when not acutely provoked or frustrated. In a mixed clinical and community sample of 5–18-year-olds, both parents and youth far less often endorsed the items “Angry most of the time” and “Stay angry for a long time” compared with “Often lose temper,” “Easily annoyed by others,” and “Get angry frequently” (Stringaris et al. 2012).

It is important to determine whether children with periodic aggressive outbursts might gain less benefit from treatment when they also experience persistent irritability or anger. Stimulant treatment and guidance in behavioral management strategies lead to remission of severe aggression for many preadolescents with ADHD and a disruptive disorder, especially when the medication is methodically titrated to optimize response (Blader et al. 2009, 2013; Aman et al. 2014). However, because stimulant treatment and behavioral interventions for conduct problems are not usually considered treatments for pervasive mood disturbances, one might expect worse outcomes among those who experience such mood problems. Behavioral interventions for disruptive behavior symptoms often make desirable items, events, or positive attention contingent on more adaptive behaviors, but persistently negative mood that diminishes capacity for enjoyment may undermine this treatment.

This study examined the relationships between persistent negative mood and treatment outcomes among a cohort of children with severe aggressive behavior who had ADHD and a disruptive behavior disorder. Children received treatment that implemented an algorithm for optimizing stimulant medication and structured family-based behavioral therapy. We evaluated 1) associations between two required elements of DMDD diagnosis, aggressive outbursts and persistently disturbed mood, at baseline and posttreatment assessments; 2) moderating effects that sustained mood disturbances at baseline might have on changes in aggressive behavior; and 3) changes in sustained mood symptoms with this treatment approach.

Method

Data source

Two clinical trials furnished the data for this report. These trials enrolled children 6–13 years old with significant aggressive behavior who met diagnostic criteria for ADHD and a disruptive behavior disorder (i.e., ODD or conduct disorder [CD]) and who had had prior stimulant treatment. Descriptions of the trials' methodology, including inclusion/exclusion criteria and the treatments studied, have been published earlier (Blader et al. 2009, 2010, 2013). In both studies, after completing baseline assessments to determine eligibility and providing informed consent, patients first underwent a protocol to openly titrate and optimize monotherapy with stimulant medication. Families received concurrent psychosocial treatment that emphasized parents' adoption of strategies to minimize and manage disruptive behaviors and to promote cooperative behaviors (Cunningham et al. 2009).

This open treatment with stimulant medication and family-based behavioral intervention was designed to identify patients whose aggressive behavior was refractory to these first-line treatments (i.e., stimulant monotherapy and guidance in behavioral management strategies). Patients whose aggressive behavior remained problematic were eligible for randomization to adjunctive pharmacotherapy conditions, which, in the first trial, compared divalproex sodium (DVPX) to placebo added to the stimulant regimen, and, in the second trial, evaluated adjunctive DVPX, risperidone, and placebo. Because the lead-in procedures for both trials were identical, we combined the samples for this report.

The first trial was conducted at two outpatient child psychiatric service settings, Stony Brook University and the North Shore–LIJ Health System, both in New York. These sites conducted the second trial, joined by the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio.

Participants

These trials enrolled girls and boys between the ages of 6 and 13 (the second trial's maximum age was 12). Diagnostic inclusion criteria comprised 1) ADHD (any subtype, per Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed., Text Revision [DSM-IV-TR]), and 2) either ODD or CD (American Psychiatric Association 2000). Exclusionary psychiatric disorders were any psychotic illness, intellectual disability (intelligence quotient [IQ] <70), major depressive or bipolar disorders, anxiety disorder that was judged primary (that is, aggressive behavior occurred almost exclusively when the child was exposed to specific anxiogenic situations), or autistic disorder. Other exclusions included medical contraindication for any study medication, seizure disorders, psychiatric hospitalization in the preceding 6 months, active suicidal ideation, and history of intolerance to any study medications severe enough to make rechallenge imprudent. Enrollment also required that the child reside with an adult able to complete written and interview assessments in English, and the availability and willingness of a guardian legally empowered to consent to participation.

Inclusion criteria required that severity of ADHD and aggressive behavior exceed thresholds on rating scales that the next section describes. Parent ratings on the Restless/Inattentive subscale of the Conners Global Index (ConnGI-P) (Conners 1997, 2008) and the Aggressive Behavior subscale of the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) (Achenbach 2001) had to be at least 1.5 standard deviations above the normative mean for the child's age and gender. Aggressive behavior during the preceding week had to be clinically significant, gauged by a total score ≥24 on the parent-completed Retrospective – Modified Overt Aggression Scale (R-MOAS), as an earlier publication described (Blader et al. 2009)

Study enrollment and assessment methods

Parents interested in their child's participation completed a screening interview with the study coordinator, usually by telephone. Eligible families were then invited for an evaluation visit. After complete description of the study, parents or legal guardians provided written informed permission, and children >8 years of age gave written assent. Institutional Review Boards at each site approved the protocol and conducted annual reviews.

Diagnostic assessment included interviews with both parent and child utilizing an adaptation of the Kiddie–Schedule of Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children (K-SADS) (Kaufman et al. 1997) by a clinical child psychologist or a child and adolescent psychiatrist. A second clinician (child and adolescent psychiatrist or advanced-practice nurse practitioner) conducted a separate clinical diagnostic evaluation and obtained a medical history. The K-SADS interviewer and the clinical assessor conferred to arrive at consensus diagnoses.

Measures of aggressive behavior, conduct problems, and ADHD

The trials' primary outcome, aggressive behavior, was assessed using the R-MOAS. This instrument is adapted from the Overt Aggression Scale (Yudofsky et al. 1986) so that parents could rate the frequency of their children's aggressive behaviors using predefined intervals, rather than clinician estimates of the number of incidents as in the original version. Parents rated the frequency of four categories of aggression (verbal, physical, toward property, and toward oneself) with four types of behavior in each category. Scoring used weights to accord greater significance to more severe forms of aggression.

ADHD severity was quantified using the Restless/Inattentive subscale of the ConnGI-P, a 10 item scale with norms for 6–17-year-olds.

Parents completed the R-MOAS and ConnGI-P at each study visit.

Measures of persistent negative mood

Two study measures completed at baseline and at the end of the stimulant monotherapy protocol contained 14 items that indicated persistent negative mood. Most reflected irritability or anger. Although depression is not among the persistent mood abnormalities of DMDD, a predecessor construct, severe emotional dysregulation (Leibenluft 2011), did include sadness. We therefore augmented the irritability and anger items with those other depressive symptoms including sadness and anhedonia.

Emotion Regulation Checklist (ERC)

Parents rated the frequencies of child characteristics on a scale from “Rarely/Never” to “Almost Always” (Shields and Cicchetti 1997). This study included eight items bearing on persistent mood disturbances. Six were counted as present when rated as “Almost Always” (“Is easily frustrated,” “Is prone to angry outbursts /tantrums easily,” “Seems sad or listless,” “Displays flat affect,” “Is whiny or clingy with adults,” “Responds negatively to neutral or friendly overtures by peers”), and two counted as present when rated “Rarely/Never” (“Is a cheerful child,” “Can recover quickly from upset or distress”).

Children's Depression Rating Scale – Revised (CDRS)

Clinical assessors rated symptoms based on information from parent and child interviews and observations (Poznanski and Mokros 1996). Each symptom has anchors to specify severity on a 1–7 scale, most of which include duration and frequency criteria. We analyzed the following items: “Difficulty having fun,” “Social withdrawal,” “Irritability,” “Excessive guilt,” “Low self-esteem,” and “Depressed feelings.” Items were classified as persistent when the severity rating reflected their presence at least most of the time.

Treatment protocol

After discontinuation of any nonstimulant medication (preceded by tapering and followed by a washout period, as indicated), stimulant titration usually started with an osmotically releasing methylphenidate (MPH) preparation given once daily. As clinically needed, a once-daily MPH preparation with a shorter overall duration of action, using a bead-coating mechanism to control release, was also used. Children whose ADHD symptoms did not respond to these MPH products could switch to extended-release mixed amphetamine salts (MAS-XR).

Adjustments to medication and dosage took place at weekly office visits, and concluded when 1) ADHD symptoms resolved, 2) unacceptable or unmanageable adverse effects required dose reduction or discontinuation, or 3) the agent's daily ceiling was attained (MPH, 90 mg/day; MAS-XR, 35 mg/day). Clinicians reviewed ConnGI-P and R-MOAS data at each visit, to identify the best tolerated regimen associated with greatest symptomatic improvement. The stimulant monotherapy end-point assessment occurred thereafter.

Families had behaviorally oriented psychosocial treatment throughout the trial. Treatment content was the Community Parent Education (COPE) program (Cunningham et al. 2000) adapted for trials involving children with ADHD (Pelham et al. 2001). Clinical psychologists or advanced graduate students provided this treatment.

Classification of remitted versus refractory aggressive behavior

At the end-point assessment, children with R-MOAS scores ≥15 were classified as stimulant refractory. Those with lower scores were classified as having remission of their aggressive behavior, based on prior work indicating that this range was associated with no or negligible aggressive behavior (Blader et al. 2009, 2010).

Data analysis

Data reduction of mood symptom ratings

Principal factors analysis of the selected ERC and CDRS-R items identified composite factors that parsimoniously reflect persistent negative mood. SAS® PROC FACTOR implemented an iterated principal factors algorithm, and we used item-factor loadings and scoring coefficients based on varimax rotation. A two factor solution was optimal (Table 1). Factor 1 reflects sadness and anhedonia, and Factor 2 reflects irritability and low frustration tolerance (eigenvalues of the rotated solution are 2.42 and 2.07, respectively).

Table 1.

Principal Factors Analysis of Items Indicative of Persistent Mood Symptoms

| Item (source) | Factor 1 | Factor 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Is a cheerful child (ERC) | −0.52399 | −0.27252 |

| Can recover quickly from upset or distress (ERC) | −0.14323 | −0.30504 |

| Is easily frustrated (ERC) | 0.10391 | 0.66185 |

| Is prone to angry outbursts/tantrums easily (ERC) | −0.00090 | 0.86718 |

| Seems sad or listless (ERC) | 0.66980 | 0.21539 |

| Displays flat affect (ERC) | 0.29964 | 0.19756 |

| Is whiney or clingy with adults (ERC) | 0.08333 | 0.39699 |

| Responds negatively to neutral or friendly overtures by peers (ERC) | 0.24115 | 0.36349 |

| Difficulty having fun (CDRS) | 0.61804 | 0.13983 |

| Social withdrawal (CDRS) | 0.04079 | 0.06134 |

| Irritability (CDRS) | 0.29849 | 0.50047 |

| Excessive guilt (CDRS) | 0.39716 | 0.02459 |

| Low self-esteem (CDRS) | 0.51471 | 0.20918 |

| Depressed feelings (CDRS) | 0.78556 | 0.12872 |

Factor loading with absolute value higher than 0.5 are in boldface.

ERC, Emotion Regulation Checklist; CDRS, Children's Depression Rating Scale – Revised.

Baseline mood symptoms and relation to aggressive behavior outcomes

We tabulated the frequencies of persistent mood symptoms for the cohort as a whole. Analysis of variance compared baseline aggressive behavior ratings for groups formed by the persistence versus nonpersistence of each symptom. Logistic regression using PROC GLIMMIX of SAS® (SAS Institute Inc. 2011) tested the association between each mood symptom's baseline value (categorized as persistent vs. not) and subsequent treatment response (aggression remitted vs. not).

Mixed-models regression evaluated the change over time in aggressive behavior as a function of depression and irritability factor scores. R-MOAS scores from baseline to stimulant monotherapy end-point were regressed onto baseline mood symptom factor scores, time, and their interactions.

Changes in mood symptoms from baseline to stimulant monotherapy end-point

Mixed-models regression analyzed changes from baseline to stimulant monotherapy end-point in the prevalence of each mood symptom (as a binomial variable, persistent vs. not), also with PROC GLIMMIX. These regression models evaluated the interaction between time and treatment response group (aggression remitted vs. not) in predicting symptom prevalence. Supplementing these analyses of mood symptoms dichotomized as persistent versus not, mixed-models regression examined changes in the depression and irritability factor scores over time and in relation to treatment response group.

Results

Participant sample

Data for this report come from the same cohort of trial participants described elsewhere (Blader et al. 2013), minus four patients with missing data on baseline mood symptoms. Mean age (SD) of the resulting sample of 156 children (123 males, 33 females) was 9.28 (2.16) years. The sample included 25 African American children (16.03%), 31 of Hispanic ethnicity (19.87%), 91 white children (58.33%), and 9 of mixed heritage (5.77%). In addition to the diagnosis of ADHD required for study enrollment, 90.32% had ODD at initial assessment and 9.68% had CD. A mood disorder (usually depressive disorder not otherwise specified) was diagnosed among 10.39% and an anxiety disorder among 24.68%.

Characteristics of open treatment

The mean (SD) number of days from trial entry to the stimulant monotherapy end-point assessment was 70.04 (37.83). Of the 156 participants, 79 (51%) fulfilled criteria for remission of aggressive behavior (31/60 [51.67%] in the first trial, 46/96 [47.92%] in the second). Another 21 (13.5%) did not meet remission criteria, but residual aggressive behavior was below the severity threshold warranting adjunctive medication. For 118 participants (76%), the optimized stimulant regimen was an MPH product (mean [SD] daily dose of 49 [17] mg), and for the other 38 patients (24%) the mean [SD] MAS-XR dose was 24 [7.7] mg.

Baseline mood symptom frequencies and treatment outcomes for aggressive behavior

Table 2 presents the prevalence of persistent mood disturbance symptoms for this cohort. The middle portion of the table contains the baseline R-MOAS scores for children persistently affected by the symptom and for those who were not. The rightmost section of the table shows the proportion in each group who attained remission of aggressive behavior at the end of the stimulant monotherapy protocol.

Table 2.

Prevalence of Symptoms of Persistent Mood Disturbance at Baseline and Associations with Initial Aggressive Behavior Ratings and Treatment Outcomes

| Baseline R-MOAS least-squares mean (SE) | Aggression remitted % (n) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symptom | Persistent % (n) | Persistent | Not persistent | F, p | Persistent | Not persistent | OR (95% CI) |

| Is a cheerful child (rarely) | 45.51% (71) | 54.30 (2.75) | 54.43 (2.58) | 0.00 0.972 | 56.34% (40) | 45.88% (39) | 1.52 (0.803 – 2.883) |

| Can recover quickly from upset or distress (rarely) | 73.08% (114) | 55.16 (2.25) | 52.53 (3.42) | 0.41 0.521 | 49.12% (56) | 54.76% (23) | 0.80 (0.390 – 1.631) |

| Is easily frustrated | 72.44% (113) | 56.10 (2.16) | 49.31 (3.70) | 2.52 0.114 | 48.67% (55) | 55.81% (24) | 0.75 (0.369 – 1.529) |

| Is prone to angry outbursts/tantrums easily | 79.49% (124) | 57.51 (2.09) | 43.80 (3.83) | 9.90 0.002 | 48.39% (60) | 59.38% (19) | 0.64 (0.290 – 1.420) |

| Seems sad or listless | 10.90% (17) | 57.14 (5.68) | 54.03 (1.99) | 0.27 0.605 | 52.94% (9) | 50.36% (70) | 1.11 (0.401 – 3.065) |

| Displays flat affect | 7.69% (12) | 71.07 (6.61) | 52.95 (1.92) | 6.93 0.009 | 75.00% (9) | 48.61% (70) | 3.17 (0.816 – 12.33) |

| Is whiney or clingy with adults | 35.90% (56) | 59.36 (3.15) | 51.70 (2.31) | 3.85 0.051 | 42.86% (24) | 55.00% (55) | 0.61 (0.316 – 1.193) |

| Responds negatively to neutral or friendly overtures by peers | 21.79% (34) | 59.71 (4.04) | 52.92 (2.11) | 2.22 0.138 | 50.00% (17) | 50.82% (62) | 0.97 (0.450 – 2.082) |

| Difficulty having fun | 1.28% (2) | 38.50 (18.38) | 54.54 (1.89) | 0.75 0.386 | 50.00% (1) | 50.65% (78) | 0.97 (0.059 – 16.21) |

| Social withdrawal | 3.21% (5) | 44.17 (10.61) | 54.70 (1.90) | 0.96 0.330 | 20.00% (1) | 51.66% (78) | 0.23 (0.025 – 2.180) |

| Irritability | 30.77% (48) | 59.93 (3.45) | 52.08 (2.21) | 3.67 0.057 | 43.75% (21) | 53.70% (58) | 0.67 (0.336 – 1.336) |

| Excessive guilt | 0% (0) | 0 (0) | 54.37 (1.87) | n/a | 0% (0) | 50.64% (79) | n/a |

| Low self-esteem | 7.69% (12) | 45.27 (6.69) | 55.14 (1.95) | 2.01 0.158 | 41.67% (5) | 51.39% (74) | 0.68 (0.203 – 2.249) |

| Depressed feelings | 1.92% (3) | 40.67 (15.00) | 54.59 (1.89) | 0.85 0.358 | 33.33% (1) | 50.98% (78) | 0.48 (0.042 – 5.518) |

R-MOAS, Retrospective – Modified Overt Aggression Scale.

There were two negative mood symptoms for which patients rated as experiencing them “almost always” had higher baseline aggression scores than those who did not. These were “Is prone to angry outbursts,” with overall sample prevalence of 74.49%, and “Displays flat affect,” occurring among 7.69%. Notable but statistically unreliable elevations in baseline aggression ratings were observed for those rated as persistently “Whiny or clingy with adults” (p = .051) and showing “Irritability” (p = .057) (with overall prevalence of 35.69% and 30.77%, respectively).

However, no single persistent negative mood symptom at baseline predicted a reduced likelihood that aggression would remit (confidence intervals [CIs] for all odds ratios [ORs] include 1).

If we use ratings of persistent irritability (based on the CDRS-R) as a proxy for DMDD's diagnostic criterion irritability or anger as the child's prevailing mood state between outbursts, then 30.77% would fulfill criteria for DMDD. Items relating to anger essentially queried the frequency of outbursts (e.g., “Is prone to angry outbursts/tantrums easily,” “Is easily frustrated”) were much more prevalent (79.5% and 72.44%, respectively).

Effects of baseline irritability and depression factor scores on aggressive behavior

Table 3 shows the results of mixed-models regression analyses for the effect of baseline mood symptom factor scores (irritability and depression), time, and their interactions on R-MOAS scores. There are two main effects on R-MOAS ratings, those for time and baseline irritability, the latter reflecting overall higher aggression ratings with higher initial irritability.

Table 3.

Effects of Baseline Mood Symptom Factor Scores on Aggressive Behavior Outcomes (R-MOAS Total Score)

| Predictor | Estimate | Std error | df | t value | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time | 29.11 | 2.51 | 138 | 11.59 | 0.000 |

| Baseline irritability | 6.33 | 2.84 | 138 | 2.23 | 0.028 |

| Baseline depression | 3.06 | 2.31 | 138 | 1.32 | 0.188 |

| Depression x irritability | −7.94 | 2.71 | 138 | −2.93 | 0.004 |

| Irritability x time | 0.67 | 3.26 | 138 | 0.21 | 0.837 |

| Depression x time | −5.06 | 2.65 | 138 | −1.91 | 0.058 |

| Depression x irritability x time | 6.53 | 3.11 | 138 | 2.10 | 0.037 |

R-MOAS, Retrospective – Modified Overt Aggression Scale.

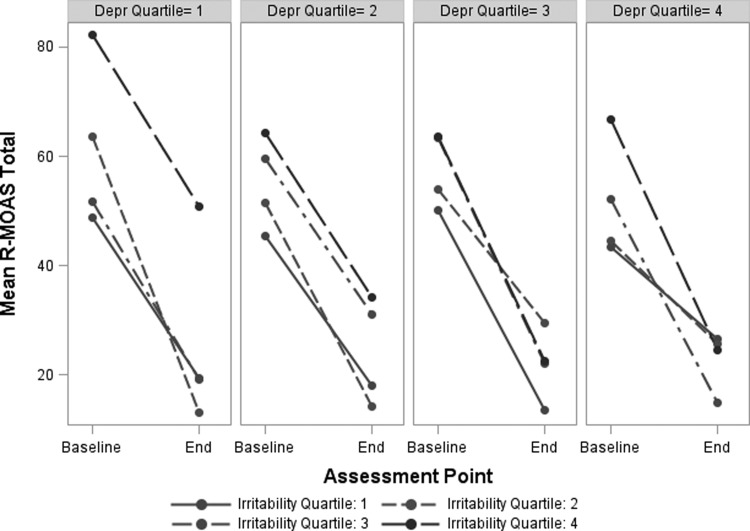

However, the three-way interaction among the baseline depression and irritability factor scores and time is significant. This results from the shifting relationship between baseline irritability and change in aggression scores as a function of baseline depression. Figure 1 illustrates these effects by showing mean R-MOAS scores at baseline and end-point for groups stratified by depression quartile (separate graphs) and irritability quartile (lines within graphs). Among those with the lowest baseline depression factor scores (1st quartile, on left), children with high irritability (4th quartile, top line) show the highest aggression scores at both times and improve less. Groups with higher baseline depression (quartiles 2–4) show smaller effects of high irritability on overall aggressive behavior. That is, across depression quartiles 2–4, end-point aggression scores for children with high irritability show increasingly smaller differences from the other irritability quartiles. In other words, with increasing depression scores, high baseline irritability seems less likely to hamper improvements in aggressive behavior.

FIG. 1.

Association of changes in aggressive behavior with baseline irritability and depression factor scores. To depict the significant irritability x depression x time interaction effect, panels are arranged by groups in increasing order of baseline depression factor scores. Each one shows the change over time in mean total aggressive behavior ratings for subgroups stratified by baseline irritability factor score. R-MOAS, Retrospective-Modified Overt Aggression Scale.

Figure 1 also clarifies the significant interaction shown in Table 3 between baseline irritability and depression factor scores on overall aggression. The regression coefficient for this effect is negative. Accordingly, Figure 1 indicates that higher depression reduces the effect of baseline irritability in raising R-MOAS scores.

Changes in persistent mood symptom frequencies from baseline to stimulant monotherapy end-point

Table 4 shows the rates of persistent mood symptoms at baseline and end-point for aggression-remitted and aggression-unremitted groups separately.

Table 4.

Prevalence of Persistent Mood Disturbance Symptoms at Baseline and Stimulant Monotherapy End-Point, by Treatment Response Group

| Symptom | Aggressive behavior outcome group | Baseline % (n) | End % (n) | Odds ratio end vs. baseline (95% CI) | Group x time interaction β | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cheerful (reverse scored) | remitted | 50.63% (40) | 58.23% (46) | 1.37 (0.718 – 2.626) | |||

| unremitted | 40.26% (31) | 46.75% (36) | 1.38 (0.674 – 2.825) | 0.04 | 0.08 | 0.936 | |

| Quickly recovers from upset (reverse scored) | remitted | 70.89% (56) | 60.76% (48) | 0.64 (0.324 – 1.247) | |||

| unremitted | 75.32% (58) | 79.22% (61) | 1.26 (0.577 – 2.736) | −0.68 | −1.32 | 0.188 | |

| Easily frustrated | remitted | 69.62% (55) | 35.44% (28) | 0.23 (0.116 – 0.458) | |||

| unremitted | 75.32% (58) | 74.03% (57) | 0.93 (0.439 – 1.977) | −1.41 | −2.76 | 0.007 | |

| Prone to angry outbursts | remitted | 75.95% (60) | 24.05% (19) | 0.09 (0.042 – 0.193) | |||

| unremitted | 83.12% (64) | 68.83% (53) | 0.44 (0.200 – 0.968) | −1.56 | −2.83 | 0.005 | |

| Sad or listless | remitted | 11.39% (9) | 3.80% (3) | 0.28 (0.066 – 1.147) | |||

| unremitted | 10.39% (8) | 11.69% (9) | 1.15 (0.399 – 3.318) | −1.40 | −1.58 | 0.116 | |

| Flat affect | remitted | 11.39% (9) | 6.33% (5) | 0.51 (0.154 – 1.667) | |||

| unremitted | 3.90% (3) | 3.90% (3) | 1.00 (0.190 – 5.253) | −0.66 | −0.65 | 0.517 | |

| Whiny/clingy with adults | remitted | 30.38% (24) | 11.39% (9) | 0.26 (0.107 – 0.642) | |||

| unremitted | 41.56% (32) | 27.27% (21) | 0.50 (0.246 – 1.025) | −0.61 | −1.07 | 0.289 | |

| Neg resp to peers' neutral or friendly overtures | remitted | 21.52% (17) | 6.33% (5) | 0.24 (0.081 – 0.703) | |||

| unremitted | 22.08% (17) | 6.49% (5) | 0.23 (0.076 – 0.683) | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.987 | |

| Difficulty having fun | remitted | 1.27% (1) | 0.00% (0) | n/a | |||

| unremitted | 1.30% (1) | 2.60% (2) | 2.03 (0.173 – 23.74) | ||||

| Withdrawn | remitted | 1.27% (1) | 0.00% (0) | n/a | |||

| unremitted | 5.19% (4) | 2.60% (2) | 0.48 (0.080 – 2.827) | ||||

| Irritable | remitted | 26.58% (21) | 2.53% (2) | 0.07 (0.016 – 0.324) | |||

| unremitted | 35.06% (27) | 24.68% (19) | 0.61 (0.298 – 1.233) | −2.13 | −2.54 | 0.012 | |

| Guilt | remitted | 0.00% (0) | 1.27% (1) | 0.07 (0.016 – 0.324) | |||

| unremitted | 0.00% (0) | 1.30% (1) | 0.61 (0.298 – 1.233) | −2.13 | −2.54 | 0.012 | |

| Low self-esteem | remitted | 6.33% (5) | 2.53% (2) | 0.38 (0.068 – 2.089) | |||

| unremitted | 9.09% (7) | 7.79% (6) | 0.84 (0.254 – 2.757) | −0.80 | −0.76 | 0.446 | |

| Depressed feelings | remitted | 1.27% (1) | 1.27% (1) | n/a | |||

| unremitted | 2.60% (2) | 3.90% (3) | 1.52 (0.240 – 9.642) | −0.43 | −0.25 | 0.805 |

Several persistent mood disturbance symptoms showed greater reductions in prevalence among patients whose aggression remitted than in those whose aggression did not remit (that is, the group x time interaction is significant). Among remitters, the proportion of those rated as almost always “Easily frustrated” decreased from 69.62% at baseline to 35.44% at the end-point (OR, 0.23; 95% CI, 0.12–0.46); among nonremitters, the rate was essentially unchanged (from 75.32 to 74.03%). Similarly, persistent irritability fell precipitously among aggressive behavior remitters (26.58% to 2.53%; OR, 0.07 [95% CI, 0.02–0.32]), while not changing significantly among nonremitters (35.06 to 24.68%; OR, 0.61 [95% CI, 0.30–1.23]). The prevalence of an “almost always” rating for “Prone to angry outbursts,” however, decreased over time in both treatment response groups, but significantly more so for remitters (75.32 to 24.05%; OR, 0.09 [95% CI, 0.04–0.19]) than for nonremitters (83.12–68.83%; OR, 0.44 [95% CI, 0.20–0.97]). Although the decrease in “Whiny/clingy with adults” was more marked among remitters (30.38 to 11.39%; OR, 0.26 [95% CI, 0.11–0.64]) than nonremitters (41.56 to 27.27%; OR, 0.50 [95% CI, 0.25–1.03]), the time x group interaction was not significant. The decline in the rate of persistently “Negative response to peers' neutral or friendly overtures” was significant and equivalent for both groups (see Table 4).

Changes in depression and irritability factor scores from baseline to treatment end-point

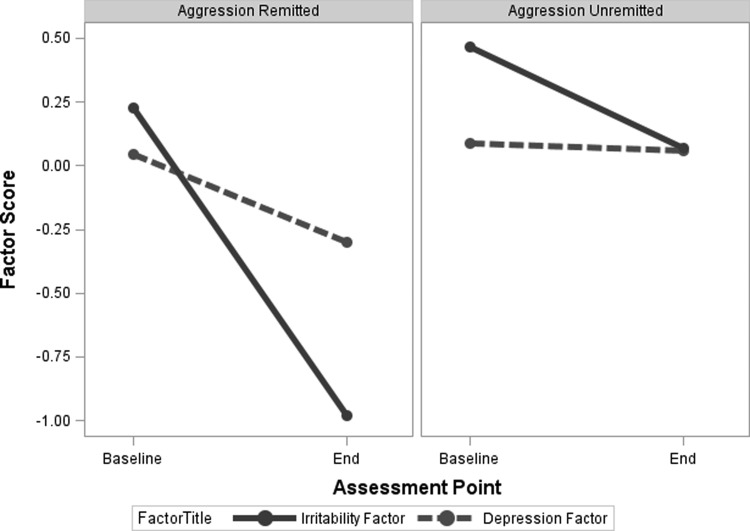

Figure 2 displays changes in mood factor scores from baseline to trial end-point over the treatment period, distinguishing children whose aggressive behavior remitted from those whose aggression did not. For the irritability factor score, a significant time x group interaction reflected the steep improvement among aggression remitters that was attenuated for nonremitters (F [1, 119] = 31.78, p < 0.001). The main effect for time was significant (F [1, 119] = 126.11, p < 0.001). The main effect for group (F [1, 119] = 37.37, p < 0.001) indicated that nonremitters had overall higher aggression ratings across assessment times.

FIG. 2.

Depression and irritability factor scores at baseline and stimulant monotherapy end-point, by treatment response group.

For the depression factor score, a significant time x group interaction (F [1, 119] = 5.30, p = 0.023), indicated improvement among remitters that was absent for nonremitters. Although the significant main effect for time was significant (F [1, 119] = 7.46, p = 0.007), that for group was not (F [1, 119] = 2.13, p = 0.147).

Discussion

In this study's cohort of children with ADHD and persistent aggressive behavior – all of whom would fulfill DMDD's “A” and “C” criteria for periodic temper outbursts – we confirmed that only ∼30% appeared to fulfill DMDD's “D” criterion for irritability or anger as their prevailing mood state between outbursts. A larger group (∼75%) were reported by parents to be “prone to angry outbursts” almost all of the time; although this feature does not necessarily characterize their inter-outburst mood precisely enough to satisfy the “D” criterion, its prevalence in this cohort signifies the tenuous emotional regulation of the patients we enrolled.

Children with persistent irritability at baseline had only a slight, statistically nonsignificant elevation in baseline aggression scores. This sample of youth selected for significant aggressive behavior does not support the contention in Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed. (DSM-5) that children with DMDD will necessarily have more severe temper outbursts (American Psychiatric Association 2013). We found some evidence for that this may be true among children with low ratings of sadness and anhedonia, and we elaborate on this finding below.

Children with sustained irritability at baseline had a lower but statistically nonsignificant likelihood, relative to other children, that their aggressive behavior would remit following stimulant monotherapy and family-based psychosocial treatment (44% vs. 54%). A continuous measure of baseline irritability also showed no moderating effect on treatment outcome. Rather than dampening response to treatment, we found that irritability and depression ratings declined markedly in tandem with improvement in aggressive behavior.

It is too soon to know if the availability of DMDD as a diagnostic option will curb the clinical use of BD to characterize children with non-episodic, chronic irritability, or address concerns that overdiagnosis of BD contributed to the proliferation of antipsychotic treatments for young patients in the United States (Blader and Carlson 2007; Moreno et al. 2007; Vitiello et al. 2009; Blader 2011; Birnbaum et al. 2013; Olfson et al. 2014). DMDD also faces questions about its test–retest reliability (Regier et al. 2013), the stability over time of the severe mood dysregulation construct (Brotman et al. 2006), and the limited scientific basis to support its validity and uniqueness from other conditions such as ODD and depressive disorders (Axelson 2013; McGough 2014). The implications of a DMDD diagnosis for treatment remain unclear. This study contributes toward an evidence-based approach for the initial treatment of sustained irritability that presents with persistent aggressive behavior and ADHD. It has often been supposed that ameliorating unstable mood is a prerequisite for impulse control to improve (e.g., Biederman et al. 1999), which may also have accelerated use of medications with mood stabilizing properties, including antipsychotics, among volatile, explosive children with ADHD. In contrast, we have shown previously that ADHD symptoms decrease markedly following stimulant monotherapy optimization among highly aggressive children, even when aggressive behavior does not fully remit (Blader et al. 2010; Blader et al. 2013). This study's data further indicate that improvements in irritability and other persistent mood-related disturbances accompany stimulant monotherapy in this patient group.

One might expect a less favorable outcome of this study's treatment protocol for children with sustained irritability who also experience sadness or anhedonia. However, this study's data indicate the opposite. As Figure 1 shows, children with high baseline irritability have the highest aggressive behavior ratings at both baseline and posttreatment assessments when depression ratings are low. At higher levels of depressive symptoms, high irritability remains associated with higher baseline aggression, but not with aggression scores after treatment. We can, for now, only speculate on possible reasons for this somewhat complicated pattern. Anergia associated with greater depressive symptoms could reduce behavioral activation and volatility. We have reported elsewhere that high internalizing symptoms correlated with less pervasive behavioral problems and emotional dysregulation (Carlson and Blader 2011), a finding consistent with the current results. Although it seems unlikely because our inclusion criteria emphasized chronic aggressive behavior, it is possible that children with high initial depression scores may have had a more episodic form of mood disorder that, on average, remitted over the period of open treatment and resulted in decreased aggressive behavior.

These data suggest the value of initial efforts to optimize stimulant monotherapy when preadolescents have high irritability and high depression (although not MDD) in the context of ADHD and disruptive behavior symptoms that feature significant aggression and explosiveness. These youngsters were found to experience equally robust, if not greater, response for behavioral symptoms. Furthermore, mood symptoms also improved with decreased aggression (Fig. 2). We recognize the clinical temptation to consider antidepressant therapy early on for these patients, but lacking data on the efficacy of these agents for irritability in this context, we infer that optimizing stimulant treatment first is the approach with stronger evidence, and may minimize polypharmacy.

These trials included open stimulant titration to ensure that only children with insufficient response to a lead-in with this first-line treatment received adjunctive medications in the trials' randomized and blinded phases. Lacking a blinded comparator group (placebo or other medication) for stimulant monotherapy impairs the ability to fully distinguish medication effects from other factors, such as nonspecific effects of trial involvement or regression to the mean. It is also unclear whether youth with DMDD but without ADHD would experience improvements with stimulant medications. At least one earlier placebo-controlled trial, however, showed benefits for MPH treatment on disruptive behavior symptoms, even among those not diagnosed with ADHD (Klein et al. 1997). Notwithstanding our finding that pretreatment persistent mood disturbance symptoms do not diminish response to stimulant monotherapy, there are a sizable number of children whose aggressive behavior and emotional dysregulation were refractory to it. For these youth, it is important to determine the relationship between mood-related symptoms and other pharmacotherapies. Analyses to address this issue are forthcoming from our controlled trial of adjunctive mood stabilizer and antipsychotic medications for stimulant-refractory aggression in children with ADHD.

Although it is often expedient to connect a medication with a specific disorder or symptom, as with MPH or amphetamine products for ADHD, the practice risks oversimplifying biology and ingrains clinical reasoning that may be disadvantageous for patients. A syllogism that stems from this line of thought is that “children with chronic mood dysregulation or DMDD have ‘more’ than ‘just’ ADHD and ODD; stimulant medications are for ADHD; therefore, stimulant monotherapy is bound to be unsatisfactory for children with chronic mood dysregulation or DMDD comorbid with ADHD.” One practical effect of this approach may have been to hasten initiation of treatments that ostensibly target mood disturbances (Birnbaum et al. 2013) before exhausting the range of potentially beneficial stimulant monotherapy regimens.

Moreover, there is increasing evidence that children and adults with ADHD show differences in blood oxygenation level dependent (BOLD) signal in functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) during paradigms that assess reward and general affective processing (von Rhein et al. 2015). There is certainly a need to better define these effects in light of task and sample differences. Nonetheless, this research highlights the relevance of neural systems subserving reward and loss for understanding the pathophysiology of ADHD and its strong relationship to aggression and negative mood symptoms. These neural systems are conceptually and empirically linked to hedonic tone, frustration tolerance, and, irritability. Moreover, the brain regions most consistently showing these group differences (the ventral striatum, which is chiefly the nucleus accumbens, and orbitofrontal and medial prefrontal cortices) are dopamine (DA)-receptor rich and susceptible to the effect of agents, such as stimulant medications, that inhibit DA transporter activity (Beaulieu and Gainetdinov 2011). Reduced DA signaling and reward responding in the striatum has also been linked to increased irritability and negative mood symptoms (Laakso et al. 2003; Forbes and Dahl 2005), which may provide basis for the positive effects on mood in children with ADHD that we observed with stimulant agents.

Conclusions

Children with ADHD and a disruptive behavior disorder who also fulfill DMDD's criterion for chronically irritable or angry mood in between temper outbursts exhibit aggressive behavior that is more severe at baseline but that also diminishes robustly following optimized stimulant monotherapy. In addition, chronic irritable mood itself lessens in tandem with decreased aggression. Children with ADHD whose aggressive behavior does not decrease satisfactorily with stimulant treatment alone likely require augmentative pharmacotherapy and extended behavioral interventions to attain improved behavioral and affective stability.

Clinical Significance

We conclude that this study furnishes additional evidence that children whose aggressive and rageful outbursts develop in the context of chronic irritability, a disruptive behavior disorder, and ADHD may be best served by initial pharmacotherapy that endeavors to optimize response to stimulant treatment, while reserving alternative medications, including second-generation antipsychotics and polytherapy, until the initial treatment regimen is demonstrably ineffective or poorly tolerated.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the contributions of Drs. Brigitte Y. Bailey, W. Burleson Daviss, Thomas Matthews, Christa Sinha, and Jeffrey Sverd. We also thank the families who participated in this study.

Disclosures

Dr. Blader has received research funding from Abbott Laboratories and Supernus, and he was a paid consultant for Shire and Supernus. Dr. Pliszka has received research fundings from Ironshore Pharmaceuticals, Janssen, Purdue Pharma, and Shire, was a paid consultant for Shire and Ironshore, was a paid speaker for Shire and McNeil Pharmaceuticals, and was a compensated expert witness for Eli Lilly. Dr. Kafantaris has received research support from Astra-Zeneca, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Merck, and Pfizer. Dr. Posner has received research support from Shire. Dr. Carlson has received research support from Pfizer. Drs. Sauder, Foley, Crowell, and Margulies report no disclosures or conflicts of interests.

References

- Achenbach TM: The Manual for the ASEBA School-Age Forms and Profiles. Burlington, VT: ASEBA, University of Vermont; 2001 [Google Scholar]

- Althoff RR, Kuny-Slock AV, Verhulst FC, Hudziak JJ, van der Ende J: Classes of oppositional-defiant behavior: concurrent and predictive validity. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 55:1162–1171, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aman MG, Bukstein OG, Gadow KD, Arnold LE, Molina BS, McNamara NK, Rundberg–Rivera EV, Li X, Kipp H, Schneider J, Butter EM, Baker J, Sprafkin J, Rice RR, Jr, Bangalore SS, Farmer CA, Austin AB, Buchan–Page KA, Brown NV, Hurt EA, Grondhuis SN, Findling RL: What does risperidone add to parent training and stimulant for severe aggression in child attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder? J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 53:47–60, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed., Text Revision. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000 [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013 [Google Scholar]

- Axelson D: Taking disruptive mood dysregulation disorder out for a test drive. Am J Psychiatry 170:136–139, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axelson D, Findling RL, Fristad MA, Kowatch RA, Youngstrom EA, Horwitz SM, Arnold LE, Frazier TW, Ryan N, Demeter C, Gill MK, Hauser–Harrington JC, Depew J, Kennedy SM, Gron BA, Rowles BM, Birmaher B: Examining the proposed disruptive mood dysregulation disorder diagnosis in children in the Longitudinal Assessment of Manic Symptoms study. J Clin Psychiatry 73:1342–1350, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkley RA: Emotional dysregulation is a core component of ADHD. In: Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: A Handbook for Diagnosis & Treatment. Edited by Barkley RA R.A. New York: Guilford Press; 2015; pp. 81–115 [Google Scholar]

- Beaulieu J-M, Gainetdinov RR: The physiology, signaling, and pharmacology of dopamine receptors. Pharmacol Rev 63:182–217, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biederman J, Mick E, Prince J, Bostic JQ, Wilens TE, Spencer T, Wozniak J, Faraone SV: Systematic chart review of the pharmacologic treatment of comorbid attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in youth with bipolar disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 9:247–256, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birnbaum M, Saito E, Gerhard T, Winterstein A, Olfson M, Kane J, Correll C: Pharmacoepidemiology of antipsychotic use in youth with ADHD: Trends and clinical implications. Curr Psychiatry Rep 15:1–13, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blader JC: Acute inpatient care for psychiatric disorders in the United States, 1996 through 2007. Arch Gen Psychiatry 68:1276–1283, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blader JC, Carlson GA: Increased rates of bipolar disorder diagnoses among U.S. child, adolescent, and adult inpatients, 1996–2004. Biol Psychiatry 62:107–114, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blader JC, Carlson GA: Bipolar disorder. In: Child and Adolescent Psychopathology. Edited by T.P. Beauchaine S.P. Hinshaw. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2013; pp. 613–648 [Google Scholar]

- Blader JC, Pliszka SR, Jensen PS, Schooler NR, Kafantaris V: Stimulant-responsive and stimulant-refractory aggressive behavior among children with ADHD. Pediatrics 126:e796–e806, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blader JC, Pliszka SR, Kafantaris V, Foley CA, Crowell JA, Carlson GA, Sauder CL, Margulies DM, Sinha C, Sverd J, Matthews TL, Bailey BY, Daviss WB: Callous-unemotional traits, proactive aggression, and treatment outcomes of aggressive children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 52:1281–1293, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blader JC, Schooler NR, Jensen PS, Pliszka SR, Kafantaris V: Adjunctive divalproex sodium vs. placebo for children with ADHD and aggression refractory to stimulant monotherapy. Am J Psychiatry 166:1392–1401, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brotman MA, Schmajuk M, Rich BA, Dickstein DP, Guyer AE, Costello EJ, Egger HL, Angold A, Pine DS, Leibenluft E: Prevalence, clinical correlates, and longitudinal course of severe mood dysregulation in children. Biol Psychiatry 60:991–997, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke JD, Boylan K, Rowe R, Duku E, Stepp SD, Hipwell AE, Waldman ID: Identifying the irritability dimension of ODD: Application of a modified bifactor model across five large community samples of children. J Abnorm Psychol 123:841–851, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson GA, Blader JC: Diagnostic implications of informant disagreement for manic symptoms. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 21:399–405, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conners CK: Conners' Rating Scales – Revised. Technical manual. North Tonawanda, NY: Multi-Health Systems; 1997 [Google Scholar]

- Conners CK: Conners 3rd Edition™ Manual. Toronto: Multi-Health Systems; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham CE, Bremner RB, Secord–Gilbert M: COPE: The Community Parent Education Program: A School-Based Family Systems Oriented Workshop for Parents of Children with Disruptive Behavior Disorders. Hamilton, Ontario: COPE Works! 2000 [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham CE, Bremner R, Secord M, Harrison R: COPE The Community Parent Education Program: A School-Based Family Systems Oriented Workshop for Parents of Children with Disruptive Behavior Disorders. 2nd ed. Hamilton, Ontario: COPE Works! 2009 [Google Scholar]

- Forbes EE, Dahl RE: Neural systems of positive affect: Relevance to understanding child and adolescent depression? Dev Psychopathol 17:827–850, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karalunas SL, Fair D, Musser ED, Aykes K, Iyer SP, Nigg JT: Subtyping attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder using temperament dimensions: Toward biologically based nosologic criteria. JAMA Psychiatry 71:1015–1024, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, Rao U, Flynn C, Moreci P, Williamson D, Ryan N: Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL): Initial reliability and validity. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 36:980–988, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein RG, Abikoff H, Klass E, Ganeles D, Seese LM, Pollack S: Clinical efficacy of methylphenidate in conduct disorder with and without attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 54:1073–1080, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laakso A, Wallius E, Kajander J, Bergman J, Eskola O, Solin O, Ilonen T, Salokangas RK, Syvalahti E, Hietala J: Personality traits and striatal dopamine synthesis capacity in healthy subjects. Am J Psychiatry 160:904–910, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leibenluft E: Severe mood dysregulation, irritability, and the diagnostic boundaries of bipolar disorder in youths. Am J Psychiatry 168:129–142, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGough JJ: Chronic non-episodic irritability in childhood: Current and future challenges. Am J Psychiatry 171:607–610, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno C, Laje G, Blanco C, Jiang H, Schmidt AB, Olfson M: National trends in the outpatient diagnosis and treatment of bipolar disorder in youth. Arch Gen Psychiatry 64:1032–1039, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigg JT, Casey BJ: An integrative theory of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder based on the cognitive and affective neurosciences. Dev Psychopathol 17:785–806, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olfson M, Blanco C, Wang S, Laje G, Correll CU: National trends in the mental health care of children, adolescents, and adults by office-based physicians. JAMA Psychiatry 71:81–90, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelham WE, Gnagy EM, Burrows–Maclean L, Williams A, Morrisey SM, Chronis AM, Forehand GL, Nguyen CA, Hoffman MT, Lock TM, Fiebelkorn K, Coles EK, Panahon CJ, Steiner RL, Meichenbaum DL, Onyango AN, Morse GD: Once-a-day Concerta methylphenidate versus three-times-daily methylphenidate in laboratory and natural settings. Pediatrics 107:e105, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poznanski EO, Mokros HB: Children's Depression Rating Scale™, Revised. Torrance, CA: Western Psychological Services; 1996 [Google Scholar]

- Regier DA, Narrow WE, Clarke DE, Kraemer HC, Kuramoto SJ, Kuhl EA, Kupfer DJ: DSM-5 field trials in the United States and Canada, Part II: Test–retest reliability of selected categorical diagnoses. Am J Psychiatry 170:59–70, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagvolden T, Johansen EB, Aase H, Russell VA: A dynamic developmental theory of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) predominantly hyperactive/impulsive and combined subtypes. Behav Brain Sci 28:397–419; 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute Inc.: SAS/STAT® 9.3 User's Guide. Cary, NC: SAS Institute; 2011 [Google Scholar]

- Shields A, Cicchetti D: Emotion regulation among school-age children: The development and validation of a new criterion Q-sort scale. Dev Psychol 33:906–916, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stringaris A, Goodman R: Three dimensions of oppositionality in youth. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 50:216–223, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stringaris A, Goodman R, Ferdinando S, Razdan V, Muhrer E, Leibenluft E, Brotman MA: The Affective Reactivity Index: A concise irritability scale for clinical and research settings. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 53:1109–1117, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitiello B, Correll C, van Zwieten–Boot B, Zuddas A, Parellada M, Arango C: Antipsychotics in children and adolescents: Increasing use, evidence for efficacy and safety concerns. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 19:629–635, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Rhein D, Cools R, Zwiers MP, van der Schaaf M, Franke B, Luman M, Oosterlaan J, Heslenfeld DJ, Hoekstra PJ, Hartman CA, Faraone SV, van Rooij D, van Dongen EV, Lojowska M, Mennes M, Buitelaar J: Increased neural responses to reward in adolescents and young adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and their unaffected siblings. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 54:394–402, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yudofsky SC, Silver JM, Jackson W, Endicott J, Williams D: The Overt Aggression Scale for the objective rating of verbal and physical aggression. Am J Psychiatry 143:35–39, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]