Abstract

We aimed to evaluate a fluorescent-labeled single chain variable fragment (scFv) of the anti-PSMA antibody as a specific probe for the detection of prostate cancer by in vivo fluorescence imaging. An orthotopic model of prostate cancer was generated by injecting LNCaP cells into the prostate lobe. ScFvD2B, a high affinity anti-PSMA antibody fragment, was labeled using a near-infrared fluorophore to generate a specific imaging probe (X770-scFvD2B). PSMA-unrelated scFv-X770 was used as a control. Probes were injected intravenously into mice with prostate tumors and fluorescence was monitored in vivo by fluorescence molecular tomography (FMT). In vitro assays showed that X770-scFvD2B specifically bound to PSMA and was internalized in PSMA-expressing LNCaP cells. After intravenous injection, X770-scFvD2B was detected in vivo by FMT in the prostate region. On excised prostates the scFv probe co-localized with the cancer cells and was found in PSMA-expressing cells. The PSMA-unrelated scFv used as a control did not label the prostate cancer cells. Our data demonstrate that scFvD2B is a high affinity contrast agent for in vivo detection of PSMA-expressing cells in the prostate. NIR-labeled scFvD2B could thus be further developed as a clinical probe for imaging-guided targeted biopsies.

Prostatic carcinoma (PCa) is the most common cancer in men1 and the second cause of cancer-related deaths for North American and European men. Its aggressiveness depends on the extent of the tumor and the Gleason score which ranges from 2 (slow evolution) to 10 (fast evolution). Early detection can greatly enhance life expectancy (with survival rates reaching 100%), whereas survival rates rapidly decrease if the tumor spreads over the prostate gland2.

The current PCa diagnostic strategy which combines digital rectal examination and blood prostate-specific antigen (PSA) screening followed by transrectal guided biopsies may reduce specific mortality, but this comes at the cost of overdiagnosis and overtreatment of indolent tumors3. As such, the clinical benefit of this diagnostic work-up is uncertain4. In clinical practice, the initial biopsy scheme is based on blind sampling of 10–14 cores; this procedure shows a relatively low overall cancer detection rate of 27–40.3%5,6,7. More specific imaging tools to improve the detection rate of significant tumors with biopsies are thus necessary to improve the management of PCa.

Multiparametric magnetic resonance (MR) imaging followed by targeted biopsies has already been demonstrated to improve PCa diagnosis with a decreased detection rate of low-risk PCa and an increased detection rate of intermediate/high-risk PCa8. However, multiparametric MR imaging lacks specificity and the time required for large-scale detection of PCa makes this strategy difficult to implement due to MR scanner accessibility. Moreover, subsequent image-guided targeted biopsies still require sophisticated fusion systems or costly MR-guidance. The development of new specific molecular imaging strategies is required to accurately identify significant prostatic tumors and to guide biopsies of malignant lesions.

Currently, the prostate specific membrane antigen (PSMA), a type II transmembrane protein produced by the prostatic epithelium, is one of the promising molecular targets for PCa detection9. It is a prominent prostate cancer marker due to its over-expression in all stages of the disease, from primary to metastatic9,10,11. PSMA is also expressed in several healthy tissues like the prostatic epithelium, kidney, small intestine and salivary glands, but its expression rate is increased from 100- to 1,000-fold in PCa10. Furthermore, the ability of PSMA to be internalized after ligand binding is an attractive property that may improve efficacy for diagnostic and therapeutic purposes12,13,14.

PSMA has already been approved as a diagnostic target for scintigraphy with ProstaScint®, the radio-labeled murine monoclonal antibody (mAb) 7E11. This mAb recognizes an internal epitope of PSMA not accessible to circulating antibodies and therefore staining necrotic cells only15,16. More recently, the humanized J591monoclonal antibody targeting the extracellular epitope of PSMA available on live and dead cells was proposed and provided significant benefits in PCa imaging, leading to clinical trials in advanced cancer. In addition to antibodies, several small molecules have been described as ligands to the extracellular domain of PSMA, such as DCFBC or HBED-CC17,18. Using these ligands with 68Gallium- or 18Fluor-labeling, there has been a rapid development for PSMA-PET in metastatic or recurrent prostate cancer imaging in several European countries19. Recently, together with a combination of morphological and multiparametric functional information, PET/MRI technology was demonstrated to offer better detection of prostate cancer20, but its low availability and high cost preclude its use in large detection strategies and primary biopsy guidance.

Whereas whole antibodies also produced nonspecific binding due to the engagement of Fc receptors21, antibody fragments such as single chain variable fragments (scFv) of antibodies and minibodies seemed to be even more specific, hence the growing interest for their use as immuno-imaging probes targeting cancer cells22. Alternatively to antibody-based tools, PSMA inhibitors and aptamer to PSMA23 have also been proposed as efficient targeting agents for PCa.

Given the limitations of other imaging modalities to identify prostatic carcinoma on a large scale and to guide targeted biopsies, a hybrid approach combining ultrasound and fluorescence could be an attractive solution, as proposed by several groups24,25,26. Such systems should be able to provide sensitive and specific molecular information through the addition of an optical module to the US systems already used by clinicians and the injection of an optical probe. Several prototypes have been developed and the technique has been successfully demonstrated in vivo on canine prostates27. However, in this context, a fluorescent probe with sufficient specificity is yet to be found.

We thus aimed to evaluate a fluorescent-labeled single chain variable fragment (scFv) of the D2B anti-PSMA antibody21 as a specific probe for the detection of prostate cancer by fluorescence imaging in vivo. The probe was evaluated using an orthotopic tumor mouse model and in vivo fluorescence tomography as the imaging method.

Results

Detection of PSMA in LNCaP-lucF cells by D2B and scFvD2B

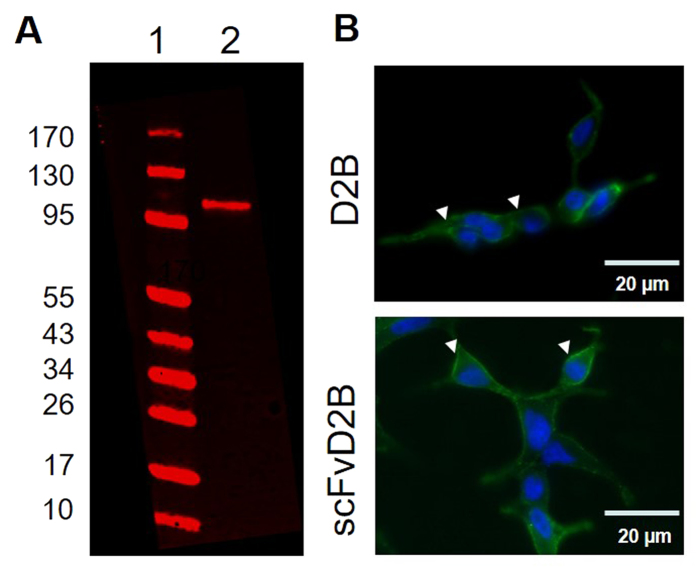

The LNCaP-lucF cell line, expressing firefly luciferase constitutively, was obtained by stable transfection with pcDNA6.2-CMV-lucF and was first tested for PSMA expression by Western blot using the anti-PSMA D2B antibody (Fig. 1A). The whole D2B antibody and the scFvD2B format were further used for immunocytochemistry on living cells. D2B or scFvD2B (800 ng each/ 500 μL) were incubated for 1 hour with living LNCaP-lucF cells on coverslips at 37 °C. Then the D2B antibody was revealed with a goat fluorescent anti-mouse IgG and the scFvD2B was revealed with an anti-His antibody, itself revealed with a goat fluorescent anti-mouse IgG. A strong immunostaining signal was detected on the cell membranes and within the soma for both D2B and scFvD2B (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1.

Evidence for PSMA expression and cell uptake by LNCaP-lucF cells (A) Western blot of LNCaP-lucF cell lysates using anti–PSMA D2B monoclonal antibody. Line 1: PageRuler marker, line 2: LNCaP-lucF cell lysate (20 μg proteins), (B) Immunocytochemistry on LNCaP-lucF living cells incubated with D2B or scFvD2B. Then D2B antibody was revealed with a goat fluorescent anti-mouse IgG and scFvD2B was revealed with an anti-His antibody, itself revealed with a goat fluorescent anti-mouse IgG. (n = 3 experiments)

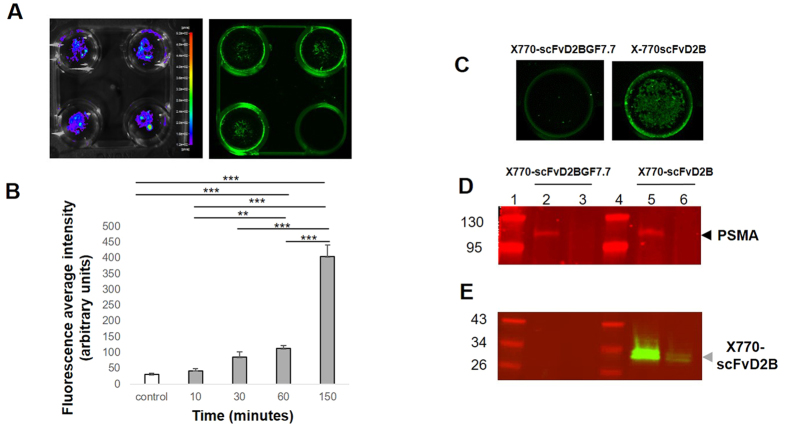

After labeling scFvD2B with Xenolight 770, other in vitro experiments were designed to monitor the binding properties of this new probe. LNCaP-lucF living cells were incubated with X770-scFvD2B probe (2 μg in 500 μL per wells) for up to 150 min. Cell distribution and viability were also followed by bioluminescence imaging (BLI) (Fig. 2A). At various time points and after a washing step cells were scanned for fluorescence and signals were compared with mock treated wells. As shown on Fig. 2A, a fluorescent signal remains within the cell after PBS washing. A significant increase of the average fluorescence signal within wells over the incubation time (from 10 to 150 min) was observed compared to the mock-treated controls (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2. Internalization of the X770-scFvD2B by LNCaP-lucF cells.

(A) LNCaP-lucF living cells were incubated with X770-scFvD2B probe and after washing scanned for fluorescence at 800 nm. As a control the lower right well did not contain X770-scFvD2B probe. BLI confirmed the presence of LNCaP-lucF living cells in each well. (B) Internalization of the X770-scFvD2B probe by LNCaP-lucF cells was followed by measuring the average fluorescence intensity at different times and compared to control wells without probes (n = 3; *** p < 0.01). (C) Fluorescence imaging of wells containing LNCaP-lucF cells incubated for 150 min with labeled scFvD2BGF7.7 or scFvD2B probes. (D,E) LNCaP-lucF incubated with labeled scFvD2BGF7.7 or scFvD2B probes were extracted for both cytosolic and membrane compartments. PSMA was detected by western blot using D2B antibody at 700 nm (D) and were mainly detected in membrane fraction (line 2 & 5) but not in cytosolic fraction (line 3 & 6). (E) X770-scFvD2B probe was detected at 800 nm in both membrane and cytosolic fractions (line 5 & 6) while X770-scFvD2BGF7.7 probe was not detected (line 2 & 3). PageRuler markers are lines 1 & 4. Each line corresponded to 119 000 LNCaP-lucF equivalent.

To further investigate the link between probe internalization and scFv/PSMA interactions, a control scFv fragment called scFvD2BGF7.7 that cannot bind the PSMA antigen was synthesized. ScFvD2BGF7.7 was obtained by replacing the sequence of the D2B variable light chain with the sequence of the surrogate light chain VpreB28. The scFvD2BGF7.7 was further labeled with Xenolight 770 (X770-scFvD2B7.7). Living LNCaP-lucF cells were incubated (37 °C) with either X770-scFvD2B or X770-scFvD2BGF7.7 probes (2 μg/well) for 150 min and uptake was compared by measuring the fluorescence signal (Fig. 2C). In the wells containing LNCaP-lucF, no staining at 800 nm was detected with X770-scFvD2BGF7.7, whereas a fluorescent signal was observed with X770-scFvD2B (n = 6). Cells of each well were harvested, processed to isolate both membrane-bound and cytosolic proteins and submitted to Western blot using the anti PSMA D2B antibody. As expected, PSMA was detected at 700 nm mainly in the membrane fractions (Fig. 2D). A strong fluorescent 800 nm-signal (2 major bands) was found at about 30 kD in the membrane fraction, consistent with the molecular weight (MW) of the X770-labeled scFvD2B, and more slightly in the cytosolic fraction of the LNCaP-lucF cells incubated with the X770-scFvD2B probe (Fig. 2E). The observed MW suggested that scFvD2B and PSMA are not bound after extraction. No fluorescent signals were detected in samples from LNCaP-lucF cells incubated with the X770-scFvD2BGF7.7 probe. These results confirmed that probe internalization observed by LNCaP-lucF living cells is linked to interactions between PSMA and scFvD2B.

Detection of X770-scFvD2B labeled LNCaP-lucF cells in the prostate using fluorescence molecular tomography (FMT)

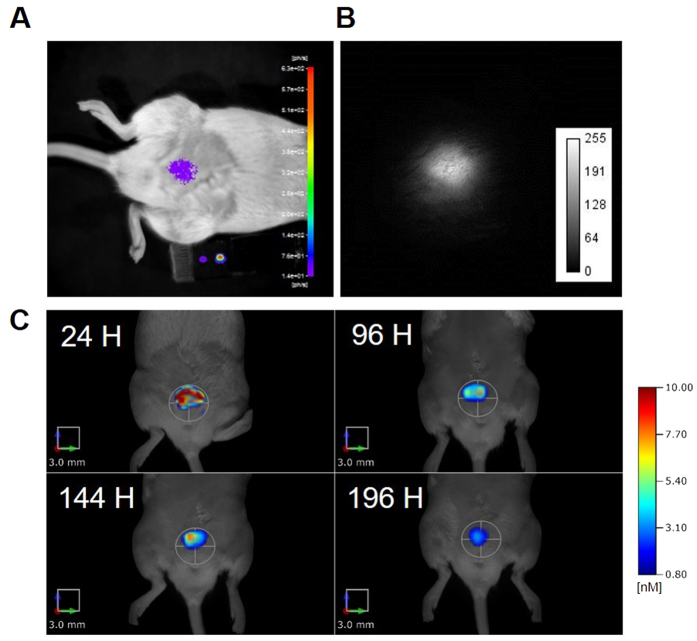

To test the feasibility of in vivo detection of fluorescent signals into the prostate, LNCaP-lucF cells were first incubated with X770-scFvD2B (10 μg/106 cells) for 2 hours at room temperature to allow for internalization. Then, after 2 washes, cells (106) were injected into the prostate by surgery (n = 3). Cell implantation and tumor growth were followed by BLI, fluorescent reflectance imaging (FRI) and FMT, daily. The X770-scFvD2B-labeled LNCaP-lucF cells, injected into prostate dorsal lobes, were detectable using BLI (Fig. 3A), FRI (Fig. 3B) and FMT (Fig. 3C). X770-scFvD2B-labeled LNCaP-lucF cells were detected by FMT from day one until day eight after surgery (Fig. 3C). These results showed that deep luciferase firefly activity could be detected in vivo in the prostate, and moreover the fluorescence signal from X770-scFvD2B-labeled cells could be followed daily in the prostate with FMT technology.

Figure 3.

In vivo detection of X770-scFvD2B-labeled LNCaP-lucF cells injected into the prostate by BLI (A), FRI at 820 nm (B) and FMT at 790 nm (C), one day after surgical implantation of X770-scFvD2B-labeled LNCaP-lucF 106 cells incubated for 2 hours with 10 μg X770-scFvD2B. (C) Time-course of the fluorescence signal (FMT) in the prostate 24, 96, 144 and 192 hours after surgery.

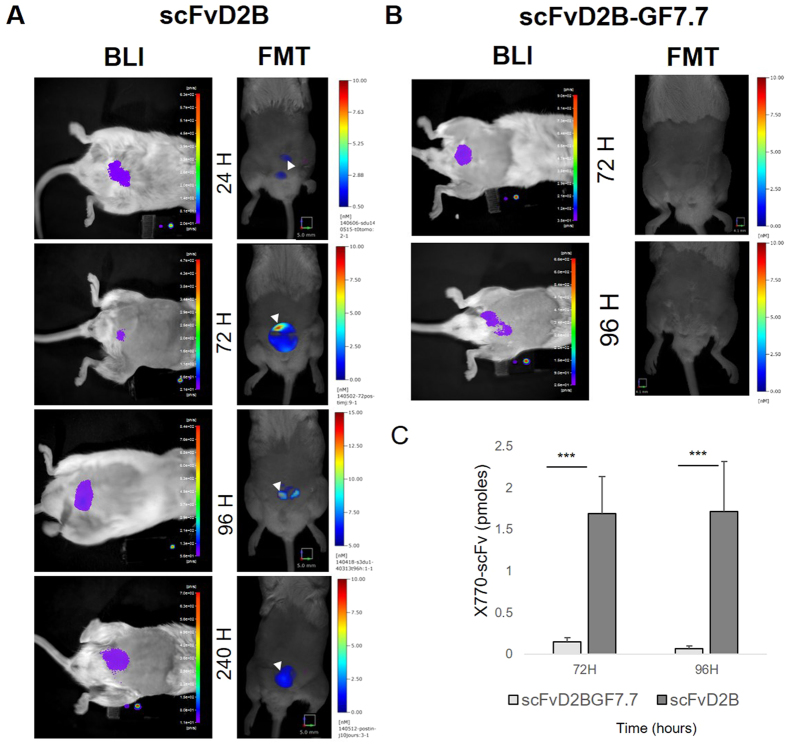

In vivo targeting of prostate tumors by X770-scFvD2BGF7.7 versus X770-scFvD2B probes

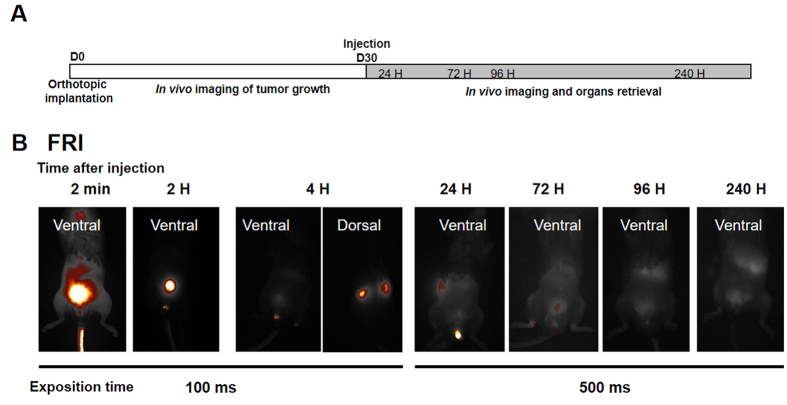

The flowchart for the experimental procedure is summarized in Fig. 4A. All mice received LNCaP-lucF cells injected into the 2 dorsal prostate lobes (0.5 × 106 cells per lobe). Tumor growth was checked by BLI (Fig. 5). Thirty days after intraprostatic cell inoculation of LNCaP-lucF, tumor growth was detected in all mice. X770-scFvD2B or X770-scFvD2BGF7.7 probes (80 μg) were injected in the tail vein and fluorescence distribution of the labeled probes was monitored by FRI and FMT at 24, 72, 96 and 240 hours. FRI revealed maximum fluorescence intensity at the injection site and in the bladder a few minutes after injection, then fluorescence slowly decreased but could still be detected in the kidneys at around 4 hours, and in the bladder and liver areas up to day 10 (Fig. 4B). By FRI, no fluorescent signal could be detected to the prostatic gland region. Detection and quantification of the fluorescence signal from X770-scFvD2B in the prostatic tumor (Fig. 5A, white arrows) was made possible by FMT analysis focused in the prostate region. The fluorescence signal was quantified 72 and 96 hours after injection. A very low fluorescence level was detected in the prostate region after X770-scFvD2BGF7.7 injection (Fig. 5B). Moreover, accumulation of the labeled scFvD2B with respect to the labeled control scFv increased 10-fold at 72 hours and 20-fold at 96 hours (Fig. 5C).

Figure 4. In vivo prostate tumor targeting by X770-scFvD2B.

(A) Experiment flowchart. (B) Selected images by FRI of mice 30 days after LNCaP-lucF cell (0.5 × 106 cells for each dorsal lobe) implantation. Mice were imaged by FRI at different times after X770-scFvD2B (80 μg) intravenous injection.

Figure 5. In vivo prostate tumor targeting by X770-scFvD2B (A) and X770-scFvD2BGF7.7 (B) probes.

BLI of mice 30 days after LNCaP-lucF cell (0.5 × 106 cells for each dorsal lobe) implantation at the time of intravenous 770-scFv probes (80 μg) injection. Each mouse was imaged by FMT at 24, 72, 96 or 240 hours after X770-scFvD2B (A) or X770-scFvD2BGF7.7 (B) injection. Quantification of the fluorescence signal recovered from FMT imaging at 72 and 96 h were plotted (C) allowing for comparison between X-770scFvD2B (n = 6 at 72 and 96 h) and X770-scFvD2BGF7.7-injected mice (n = 9 at 72 h and n = 4 at 96 h; *** p < 0.01).

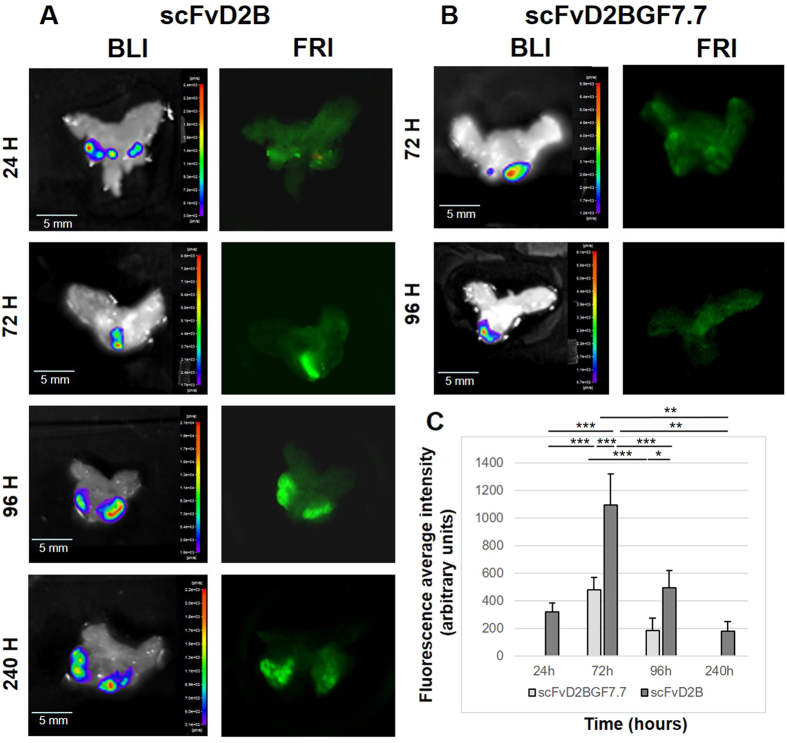

Ex vivo analysis of the prostate

Mice were sacrificed at 24, 72, 96 and 240 hours after intravenous administration of X770-scFvD2B and at 72 and 96 hours after X770-scFvD2BGF7.7 injection. Ten minutes before euthanasia, mice were injected with D-luciferin, thus excised prostates exhibited a BLI signal corresponding to lucF activity of LNCaP-lucF cells (Fig. 6A,B). Prostate from mice who received X770-scFvD2B injections exhibited a fluorescent signal overlapping the BLI signal (Fig. 6A). Animals injected with X770-scFvD2BGF7.7 showed low fluorescence retention within the tumor (Fig. 6B) that did not overlap with the BLI signal. X770-ScFvD2B fluorescence signals were quantified by scanning the prostate using an Odyssey scanner at 800 nm. As shown on Fig. 6C, the fluorescent signal in prostates from the X770-scFvD2B probe-injected mice peaked at 72 hours after injection and the fluorescence signal was significantly higher than in the prostates from control X770-scFvD2BGF7.7-injected mice.

Figure 6. Ex vivo imaging of the prostate tumor after intravenous injection of X770-scFvD2B (A) or X770-scFvD2BGF7.7 (B) probes.

The prostates were sequentially imaged by BLI and FRI at different times (C) Average intensity on whole prostate fluorescence after Odyssey scanning (n = 4 to 8 animals for each bar; ***p < 0.01).

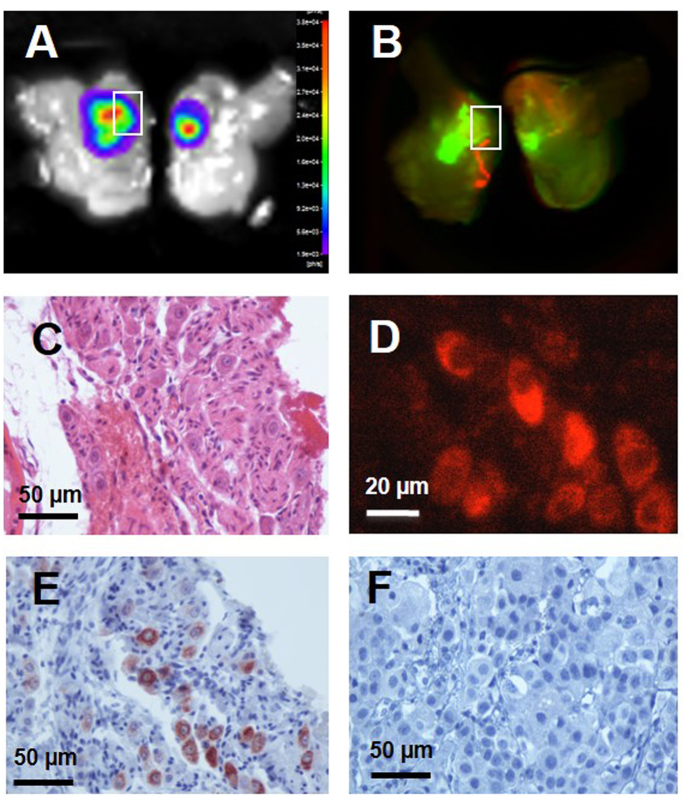

Immunohistochemical localization of X770-scFvD2B and X770-scFvD2BGF7.7 in the prostate cells

Histochemical and immunohistochemical detection were used to confirm the presence of prostatic carcinoma cells and to detect the X770-scFvD2B probe in the prostate (Fig. 7). Prostates were imaged by BLI (Fig. 7A) and FRI (Fig. 7B) to confirm colocalization of luminescent and fluorescent signals, then fixed and paraffin-embedded. HES staining revealed cancer cells and invasion of the prostatic parenchyma by the tumor cells (Fig. 7C). X770-scFvD2B was detected either directly by NIR microscopy due to the Xenolight 770 fluorophore (Fig. 7D) or by immunohistochemistry detection of the poly-histidine tag of the scFv fragment (Fig. 7E). No NIR fluorescence (data not shown) and no immunostaining was observed in mice injected with X770-scFvD2BGF7.7 (Fig. 7F).

Figure 7. Detection of the X770-scFvD2B probe in the prostate 72 hours after in vivo injection.

On bisected prostates (A) BLI revealed a prostate cancer tumor and (B) fluorescence scanning revealed the X770-scFvD2B probe. On the paraffin prostate slice (4 μm) tumor cells were revealed (C) by hematoxylin-eosin-safran staining and (D) X770-scFvD2B probe was detected by X770 fluorescence or (E) scFv His-tag detection using anti-His tag antibody (immunoperoxydase/DAB labeling). (F) No scFv His-tag was detected by immunohistochemistry after in vivo injection of the control fragment X770-scFvD2BGF7.7.

Discussion

In this study, we successfully applied, for the first time, noninvasive in vivo optical imaging to detect prostate cancer in an orthotopic mouse model using a fluorescent-labeled anti-PSMA antibody fragment scFvD2B. Specificity and binding properties of scFvD2B and its ability to internalize in PSMA-expressing cells both in vitro and in vivo has been previously described21. The present data showed that NIR fluorescent-labeled scFv, intravenously administrated reached the tumor and was internalized into PSMA-expressing cells. We further provided quantification of the fluorescence signal over time, corresponding to the presence of scFvD2B within the tumor. A control scFv that does not recognize PSMA did not label the malignant prostate tissue.

First, we developed an orthotopic mouse model of prostate cancer by intraprostatic inoculation of LNCaP cells genetically modified to follow tumor growth by BLI. Tumors occurred in 100% of operated mice and none of them developed metastases,29 mimicking the human clinical situation of a localized disease29.

As targeting moiety, we investigated the scFv format of the D2B antibody, described to have the same affinity for PSMA as the J591 whole antibody21 currently used in clinical trials30. The scFvD2B recognizes the extracellular domain of the PSMA protein. In the present work, we demonstrate that the scFvD2B is able to specifically detect PSMA on LNCaP cells in vitro. After intravenous injection of X770-scFvD2B in mice with PCa, a fluorescent signal was detected in the prostate, and this increased over 72 hours. Detection of the fluorescence was made possible by the use of FMT. FMT allows for 3D localization of deep fluorescent signals within the prostate, also allowing for absolute quantification. The localization of the X770-scFvD2B in PCa tumors was further confirmed on excised prostates by monitoring PCa tumor location by BLI and probe distribution by FRI. Our results showed that X770-scFvD2B binds to PSMA-positive cells and tumors with a strong staining, stable for at least 8 days after injection, whereas only a basal fluorescence was observed with the control antibody fragment scFvD2BGF7.7.

It has been shown that PSMA is internalized from the cell surface to the intracellular compartment via clathrin-dependent mechanisms12,31. Binding of antibodies or antibody fragments to the extracellular domain of PSMA has been shown to increase its rate of internalization 3-fold12 and PSMA internalization has been proposed as a vehicle to transport therapeutic molecules inside the cell32. In the current study, when LNCaP cells were treated with X770-scFvD2B, the fluorescent scFv fragment was found both in the membrane and in the cytosolic fraction, suggesting that the X770-scFvD2B probe is translocated into the cell through PSMA internalization. After intravenous injection of the X770-scFvD2B, the scFv fragment was detected in the tumor cells while injection of the control fragment scFvD2BGF7.7 did not accumulate in PCa cells. Overall, these observations suggest that internalization of the X770-scFvD2B probe is related to PSMA recognition and subsequent internalization. This mechanism may result in probe accumulation in PCa cells with maximal fluorescence intensity at 72 hours, but remaining detectable up to 7–8 days.

Today, the most widely-used strategies for molecular imaging of prostate cancer combine development of antibodies and small molecules (ligand or inhibitor)33,34 and radioactivity-based imaging. Currently the only FDA-approved antibody is 7E11 ProstaScint® 15,16 that binds the intracellular domain of PSMA. An alternative antibody J591 is currently being evaluated in a phase II clinical trial35. A small ligand for PSMA (BIND-014) is also currently being evaluated in a phase II trial,36 demonstrating the growing clinical interest in targeting PSMA. Recently, an anti-PSMA mAb, D2B, tagged with both111 In and IRDye 800CW was shown to be able to detect in vivo prostatic cancer cells in a subcutaneous xenograft model17. Regarding whole antibodies, scFv offered several advantages including lower immunogenicity. Its small size is also expected to facilitate better penetration within the tumor37 and may explain the rapid and strong signal observed in the current study using X770-scFvD2B probes. Furthermore, the peculiar feature of this scFv to show a high affinity in the nanomolar range (8.6 nM21), and the high level of internalization explain the persistence of this probe in the malignant prostate lesions of the treated mice.

Given the low rates of positive biopsies with current diagnosis techniques, new strategies are needed. MR-guided, MRI-US fusion-guided and contrast-enhanced US-guided biopsies are some of the currently proposed imaging solutions38. Targeting the primary tumor with optical probes, as reported in the current work using a high affinity and the very specific fluorescent-labeled anti-PSMA scFv, is, according to these preliminary preclinical results, a promising additional option. This method may help to specifically identify the tumor location and to guide transrectal sampling. This will require new imaging bi-functional (optical and US) devices, as reported recently24,25,27, and new algorithms for spatial co-localization of sonographic and optical data26. Thus, this approach consisting in in vivo staining of prostate cancer cells combined with an intraoperative optical imaging device could be used further to guide resection of malignant tumors providing a sensitive, real-time solution to reduce the risk of positive margins18.

Materials and Methods

Animals

All animal experiments were approved by the local ethical comity (CEEA 50) under agreement 50120196-A and all experiments were performed in accordance with European guidelines and regulations. Immunodeficient NOG (NOD/SCID/IL-2Rγnull) mice (6- to 10-weeks-old) were reared at the University of Bordeaux animal facilities. Animals were maintained in standard conditions under a 12-hours light/dark cycle with water and food provided ad libitum. Animals were anesthetized with 2% isoflurane (Belamont, Nicholas Piramal Limited, London, UK) in air for all surgical and imaging procedures.

For cell injection into the prostate, anesthetized mice were incised by a short abdominal longitudinal section of the skin and of the abdominal muscles. The seminal glands were grasped and pulled back outside the body. LNCaP-lucF cells (0.5 × 106/10 μL per lobe) were injected in the dorsal prostate lobes. The seminal glands were repositioned within the abdomen and the incision was closed with sutures. Mice were imaged weekly by bioluminescence to monitor tumor growth starting three weeks after implantation. At selected times, labeled scFvD2B or scFvD2BGF7.7 (80 μg) was injected via the tail vein. Prostates were removed from euthanized animals, placed in cold PBS buffer on a glass slide and imaged.

Production, purification of D2B, scFvD2B and scFvD2BGF7.7 and labeling

The monoclonal antibody D2B recognizing an external epitope of the PSMA antigen was produced by hybridoma technology and purified on protein G columns.21 The scFv format was synthesized by DNA technology from the purified mRNA of the D2B hybridoma as previously described21. The cDNA of scFv D2B was cloned in PHEN2 plasmid. The protein was produced in E.Coli HB2151 bacterial strain and purified on NiNTA columns (Qiagen, Courtaboeuf, France). The purification was checked by SDS-PAGE, binding capability and specificity were assessed by flow cytometry.

The control scFvD2BGF7.7, that is not able to bind PSMA antigen, was obtained replacing the sequence of the D2B variable light chain with the sequence of the surrogate light chain VpreB28.

The labeling reaction was made using Xenolight CF770 antibody labeling kit (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA) on batches of 500 μg of each scFv. Labeled scFv were stored in the dark at 4 °C. Quantification of the labeling was made on 2 μg of each antibody fragments by Fluorescence Molecular Tomography (FMT 4000, PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA) using system software (TrueQuant) calibrated with the fluorophore Xenolight770 CF (X770). Fluorescence labeling of scFvD2 and scfvD2BGF7.7 were 0.415 pmol/μg and 0.285 pmol/μg respectively. Fluorescence level of scfvD2BGF7.7 was thus corrected by a 1.45 factor for comparison with scFv.

Cell line generation, culture and labeling

Prostate cancer cell line LNCaP (PSMA+) (ATCC® CRL-1740™) was obtained from ATCC (Manassas, MD, USA). LNCaP cell line was grown in RPMI 1640 with Glutamax and 25 mM HEPES medium supplemented in 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% antibiotic-antimycotic mix (Life Technologies, Illkirch, France). LNCaP were stably transfected with pCDNA6.2-CMV-lucF using TransFast™ Transfection Reagent (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). The pCDNA6.2-CMV-lucF providing blasticidin resistance (10 μg/mL, Euromedex, Souffelweyersheim, France) was obtained by cloning lucF cDNA from a pGL3-basic vector (Promega) into pCDNA6.2 downstream the CMV promoter. Cells were incubated in humidified atmosphere 5% CO2/air at 37 °C.

For in vitro labeling of LNCaP-lucF with scFv, the cells were incubated with 2 μg/ 500μL of fragment at 37 °C, then washed (2 × 1 mL PBS (Life Technologies)). Samples were first scanned using Odyssey scanner (Li-Cor Biosciences, Nebraska, USA) then lysed using the Qproteome cells compartment kit (Qiagen).

Western blotting

LNCaP-lucF (2 × 106) cells were lysed using 400 μL of cold RIPA buffer (Sigma-Aldrich, Lyon, France) in the presence of a protease inhibitor cocktail (Fermentas, Illkirch, France). Samples (20 μg proteins) were analyzed by electrophoresis on 4–15% TGX stain-free gels (BioRad, Marne-la-Coquette, France) under denaturing conditions. Proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane using Transblot Turbo (Bio-Rad). PSMA was detected using mouse monoclonal D2B antibody (10 μg) and goat anti-mouse IRDye680-labeled (Li-Cor) as secondary antibody and analyzed on an Odyssey scanner at 700 nm. X770-scFvD2B or X770-scFvD2BGF7.7 were directly detected on the same membrane at 800 nm on an Odyssey scanner.

Imaging

Bioluminescence imaging (BLI)

BLI was performed at Vivoptic (Bordeaux University) using a NightOWL II-LB 983 system (Berthold Technologies, Bad-Wildbad, Germany). Mice received an intra-peritoneal injection of D-luciferin (Promega, 2.9 mg in 100 μL PBS) and were sedated 7 min later. Bioluminescence images (1 min, 4 × 4 binning) and photographs (100 ms) were taken 10 min after luciferin injection. The bioluminescence signal was analyzed using Indigo software. Prostates, removed from euthanized animals immediately after in vivo BLI, were placed in cold PBS on a glass slide and imaged (1 min). LNCaP-lucF cells in PBS in 12-well culture plates were imaged (1 min) by BLI immediately after adding D-luciferin (6.10−4 M in 200 μL PBS).

Fluorescence Molecular Tomography (FMT)

Anesthetized mice were placed in a FMT 4000 apparatus (Perkin Elmer Inc., Boston, MA, USA). Scanning was performed using the 790EX channel on the abdominal part of mice. The images were reconstructed using the TrueQuant software. The same ROI were drawn to encompass the prostate region in each animal. The total amount of fluorescence (pmoles) was calculated relative to calibration with Xenolight770 CF.

Fluorescence reflectance imaging (FRI)

Animals were imaged using the real-time intraoperative camera system Fluobeam® (Fluoptics, Grenoble, France) at a spectral window of excitation at 780 nm and emission at 820 nm. Prostates with tumor were placed into 12-well plates in cold PBS and scanned at 800 nm on Odyssey scanner.

Immunocytochemistry on living cells

LNCaP-lucF were cultured on coverslips, were incubated with D2B antibody or scFvD2B (800 ng/ 500 μL) in RPMI complete medium for 1 hour at 37 °C and fixed 10 min in 4% paraformaldehyde. Using D2B antibody, cells were incubated with goat Alexa-Fluor 488 anti-mouse IgG (Invitrogen, 1/400 in PBS 1% BSA) with DAPI (1/5000) for 1 hour and finally mounted in Fluoromount medium (Deltamicroscopies, Mauressac, France). Using scFvD2B, cells were incubated with mouse anti-His monoclonal antibody (HIS-H8, Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA) 1/500 in PBS 1% (w/v) BSA) for 1 hour at 20 °C, with Alexa-Fluor 488 anti-mouse IgG (1/500 in PBS) with DAPI (1/5000) for 1 hour and finally mounted. Observations were performed on a Leica DM 5500 microscope (Wetzlar, Germany).

Histochemistry and Immunohistochemistry

Prostates with tumors were fixed overnight at 4 °C with 4% paraformaldehyde. Then the tissues were dehydrated and embedded in paraffin. Sections (4 μm) were used for hematoxylin/eosin/safran (HES), scFvD2B and scFvD2BGF7.7 staining after dewaxing and rehydration in alcohol. The scFv fragments (scFvD2B and scFvD2BGF7.7) were detected using anti-Histidine antibody HIS-H8 (Pierce). The DAKO Envision FLEX detection system included pretreatment with DAKO PT Link (pre-treatment module) and target retrieval solution, pH 6 (K800521) 97 °C for 20 min. All steps of immunostaining were done in an automated immunostainer (Autostainer Plus, DAKO, Les Ulis, France). Inhibition of endogenous peroxidases (H2O2 3% in water, 10 min) was followed by incubation of the primary antibody (1/250, 45 min). Sections were incubated with HRP conjugated Envision (DAKO, 20 °C, 20 min) and revealed with DAB. Images were obtained on Nikon Eclipse 50i using NIS-element F software. Fluorescence from X770 was also detected on the processing slices using Leica DM 5500 microscope fitted with pE-100 (Ex 770 nm) Cool LED and a indocyanine (775/845 nm) filter (Leica Microsystems).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis included the ANOVA test for independent data and a post hoc test of Bonferroni. In all figures, error bars indicate standard deviations. *** for p < 0.01; ** for p < 0.05; * for p < 0.1.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Mazzocco, C. et al. In vivo imaging of prostate cancer using an anti-PSMA scFv fragment as a probe. Sci. Rep. 6, 23314; doi: 10.1038/srep23314 (2016).

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Muriel Busson (Montpellier, France) for teaching the surgical procedure, Dr Mokrane Yacoub (Bordeaux) for his pathology expertise, Dr. Benoit Rousseau, Dr. Pierre Costet and Laetitia Medan for rearing and taking care of mice. This work was supported in part by public grants from the French Agence Nationale de la Recherche: BITUM (ANR-10-IANN-007), Labex TRAIL (ANR-10-LABX-57) and France Life Imaging (ANR-11-INBS-006). MC and GF gratefully acknowledges Fondazione Cariverona Interceptin Project, Verona Nanomedicine Initiative and Italian Minister of Health RF-2010-2305526 for supporting this work.

Footnotes

Author Contributions C.M., N.G. and F.C. conceived and designed the experiments. C.M. and C.G.-G. performed all cell, mouse, imaging and biochemistry experiments, C.M. and N.D-S. performed histology. G.F., M.F. and M.C. design and produced ScFv. C.M. and F.C. wrote the manuscript with input from all authors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- Siegel R., Naishadham D. & Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2012. CA. Cancer J. Clin. 62, 10–29 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brawley O. W. Prostate cancer epidemiology in the United States. World J. Urol. 30, 195–200 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyer V. A. & U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for prostate cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 157, 120–134 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andriole G. L. et al. Mortality results from a randomized prostate-cancer screening trial. N. Engl. J. Med. 360, 1310–1319 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babaian R. J. et al. A comparative analysis of sextant and an extended 11-core multisite directed biopsy strategy. J. Urol. 163, 152–157 (2000). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naughton C. K., Miller D. C. & Yan Y. Impact of transrectal ultrasound guided prostate biopsy on quality of life: a prospective randomized trial comparing 6 versus 12 cores. J. Urol. 165, 100–103 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Presti J. C., O’Dowd G. J., Miller M. C., Mattu R. & Veltri R. W. Extended peripheral zone biopsy schemes increase cancer detection rates and minimize variance in prostate specific antigen and age related cancer rates: results of a community multi-practice study. J. Urol. 169, 125–129 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pokorny M. R. et al. Prospective study of diagnostic accuracy comparing prostate cancer detection by transrectal ultrasound-guided biopsy versus magnetic resonance (MR) imaging with subsequent MR-guided biopsy in men without previous prostate biopsies. Eur. Urol. 66, 22–29 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silver D. A., Pellicer I., Fair W. R., Heston W. D. & Cordon-Cardo C. Prostate-specific membrane antigen expression in normal and malignant human tissues. Clin. Cancer Res. 3, 81–85 (1997). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israeli R. S., Powell C. T., Corr J. G., Fair W. R. & Heston W. D. W. Expression of the prostate-specific membrane antigen. Cancer Res. 54, 1807–1811 (1994). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laydner H. et al. Robotic real-time near infrared targeted fluorescence imaging in a murine model of prostate cancer: A feasibility study. Urology 81, 451–457 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H. et al. Constitutive and antibody-induced internalization of prostate-specific membrane antigen. Cancer Res. 58, 4055–4060 (1998). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu T., Wu L. Y., Kazak M. & Berkman C. E. Cell-surface labeling and internalization by a fluorescent inhibitor of prostate-specific membrane antigen. The Prostate 68, 955–964 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajasekaran S. A. et al. A novel cytoplasmic tail MXXXL motif mediates the internalization of prostate-specific membrane antigen. Mol. Biol. Cell 14, 4835–4845 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troyer J. K., Beckett M. L. & Wright G. L. Location of prostate-specific membrane antigen in the LNCaP prostate carcinoma cell line. The Prostate 30, 232–242 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bander N. H. Technology insight: monoclonal antibody imaging of prostate cancer. Nat. Clin. Pract. Urol. 3, 216–225 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lütje S. et al. Dual-modality image-guided surgery of prostate cancer with a radiolabeled fluorescent anti-PSMA monoclonal antibody. J. Nucl. Med. 55, 995–1001 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietlein M. et al. Comparison of [(18)F]DCFPyL and [(68)Ga]Ga-PSMA-HBED-CC for PSMA-PET imaging in patients with relapsed prostate cancer. Mol. Imaging Biol. MIB Off. Publ. Acad. Mol. Imaging 17, 575–584 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afshar-Oromieh A. et al. The diagnostic value of PET/CT imaging with the (68)Ga-labelled PSMA ligand HBED-CC in the diagnosis of recurrent prostate cancer. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 42, 197–209 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eiber M. et al. (68)Ga-PSMA PET/MR with multimodality image analysis for primary prostate cancer. Abdom. Imaging 40, 1769–1771 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frigerio B. et al. A single-chain fragment against prostate specific membrane antigen as a tool to build theranostic reagents for prostate cancer. Eur. J. Cancer 49, 2223–2232 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne J. R. et al. Prostate-specific membrane antigen-based imaging. Urol. Oncol. Semin. Orig. Investig. 31, 144–154 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dassie J. P. et al. Targeted inhibition of prostate cancer metastases with an RNA aptamer to prostate-specific membrane antigen. Mol. Ther. J. Am. Soc. Gene Ther. 10.1038/mt (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Z. et al. Trans-rectal ultrasound-coupled near-infrared optical tomography of the prostate, part II: experimental demonstration. Opt. Express 16, 17505–17520 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boutet J. et al. Bimodal ultrasound and fluorescence approach for prostate cancer diagnosis. J. Biomed. Opt. 14, 064001 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laidevant A. et al. Fluorescence time-resolved imaging system embedded in an ultrasound prostate probe. Biomed. Opt. Express 2, 194–206 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Z. et al. In vivo trans-rectal ultrasound–coupled optical tomography of a transmissible venereal tumor model in the canine pelvic canal. J. Biomed. Opt. 14, 030506–030506–3 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morstadt L. et al. Engineering and characterization of a single chain surrogate light chain variable domain. Protein Sci. Publ. Protein Soc. 17, 458–465 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rembrink K., Romijn J. C., van der Kwast T. H., Rübben H. & Schröder F. H. Orthotopic implantation of human prostate cancer cell lines: A clinically relevant animal model for metastatic prostate cancer. The Prostate 31, 168–174 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akhtar N. H., Pail O., Saran A., Tyrell L. & Tagawa S. T. Prostate-Specific Membrane Antigen-Based Therapeutics. Adv. Urol. 2012, e973820 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouchelouche K., Choyke P. L. & Capala J. Prostate specific membrane antigen- a target for imaging and therapy with radionuclides. Discov. Med. 9, 55–61 (2010). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fracasso G. et al. Anti-tumor effects of toxins targeted to the prostate specific membrane antigen. The Prostate 53, 9–23 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X. et al. Development of targeted near-infrared imaging agents for prostate cancer. Mol. Cancer Ther. 13, 2595–2606 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ristau B. T., O’Keefe D. S. & Bacich D. J. The prostate-specific membrane antigen: Lessons and current clinical implications from 20 years of research. Urol. Oncol. Semin. Orig. Investig. 32, 272–279 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris M. J. et al. Phase I evaluation of J591 as a vascular targeting agent in progressive solid tumors. Clin. Cancer Res. 13, 2707–2713 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hrkach J. et al. Preclinical development and clinical translation of a PSMA-targeted docetaxel nanoparticle with a differentiated pharmacological profile. Sci. Transl. Med. 4, 128ra39 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokota T., Milenic D. E., Whitlow M. & Schlom J. Rapid tumor penetration of a single-chain Fv and comparison with other immunoglobulin forms. Cancer Res. 52, 3402–3408 (1992). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornelis F. et al. Real-time contrast-enhanced transrectal US-guided prostate biopsy: diagnostic accuracy in men with previously negative biopsy results and positive MR imaging findings. Radiology 269, 159–166 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]