Abstract

Background:

The evolution of the provision of palliative care specialised services is important for planning and evaluation.

Aim:

To examine the development between 2005 and 2012 of three specialised palliative care services across the World Health Organization European Region – home care teams, hospital support teams and inpatient palliative care services.

Design and setting:

Data were extracted and analysed from two editions of the European Association for Palliative Care Atlas of Palliative Care in Europe. Significant development of each type of services was demonstrated by adjusted residual analysis, ratio of services per population and 2012 coverage (relationship between provision of available services and demand services estimated to meet the palliative care needs of a population). For the measurement of palliative care coverage, we used European Association for Palliative Care White Paper recommendations: one home care team per 100,000 inhabitants, one hospital support team per 200,000 inhabitants and one inpatient palliative care service per 200,000 inhabitants. To estimate evolution at the supranational level, mean comparison between years and European sub-regions is presented.

Results:

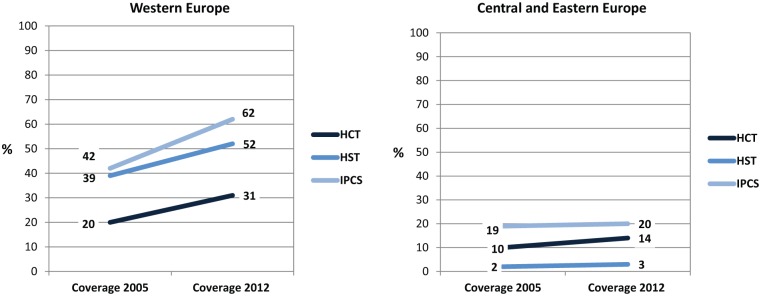

Of 53 countries, 46 (87%) provided data. Europe has developed significant home care team, inpatient palliative care service and hospital support team in 2005–2012. The improvement was statistically significant for Western European countries, but not for Central and Eastern countries. Significant development in at least a type of services was in 21 of 46 (46%) countries. The estimations of 2012 coverage for inpatient palliative care service, home care team and hospital support team are 62%, 52% and 31% for Western European and 20%, 14% and 3% for Central and Eastern, respectively.

Conclusion:

Although there has been a positive development in overall palliative care coverage in Europe between 2005 and 2012, the services available in most countries are still insufficient to meet the palliative care needs of the population.

Keywords: Palliative care, coverage, development, Europe

What is already known about the topic?

Two studies, conducted by the European Association for Palliative Care (EAPC) Task Force on the Development of Palliative Care in Europe in 2005 and 2012, reported the level of provision of PC services in the World Health Organization (WHO) European region (published in the EAPC Atlas of Palliative Care in Europe (2007) and (2013)).

Comparison of development in available services between 2005 and 2012 was limited and required secondary analysis.

European palliative care provision of specific PC services was limited without an analysis of population-based need and an estimation of current coverage per country.

What this paper adds?

Using normative guidelines produced in an EAPC White Paper, we conducted the first assessment of coverage of three types of specialised PC services: home care, hospital support teams and inpatient PC.

We also compared national development in coverage of the three types of specialist PC services between 2005 and 2012 and calculated the overall development of PC development in each country during this period.

A statistical analysis of changes detected both at country and European levels is provided to better estimate the meaning of the differences found over the period studied.

Implications for practice, theory or policy

Results of the article provide the most comprehensive information available on coverage and development of PC in Europe at the present time.

The number of services available in many countries is still insufficient to meet the PC needs of the population.

Introduction

In 2014, the 67th World Health Assembly urged member states to support the comprehensive strengthening of health systems to integrate palliative care (PC) services in the continuum of care, across all levels, with an emphasis on primary care, community and home-based care and universal coverage schemes.1 A World Health Organization (WHO) declaration highlighted ‘the limited availability of PC services in much of the world and the great avoidable suffering for millions of patients and their families’; this declaration reminds us that we need to improve our knowledge about the numbers and types of PC services that exist in specific regions of the world and their coverage at the population level. Such information is essential to inform the decisions and strategies of policy makers and health providers.

During the period 2003–2009, a series of PC mapping studies were conducted around the world.2–6 These established the number and character of PC services existing in a given country and described the associated funding arrangements, the level of policy support and the specific context of opioid availability. In 2008, a ‘world map’7 of the level of PC development for every country in the world (n = 234) was developed, using a four-part typology: (1) no identified activity (78/234, 33%); (2) capacity building, but with no operational services (41/234, 18%); (3) localised provision, without extensive coverage (80/234, 34%) and (4) development approaching integration with the wider healthcare system (35/234, 15%). In 2013, the map was updated with a more refined, six-point typology8 which demonstrated that 136 of the world’s 234 countries (58%) now had one or more hospice-PC service established – an increase of 21 countries (+9%) from 2006. But advanced integration of PC with wider health services (the highest category in the typology) had been achieved in only 20 countries globally (8.5%).

In 2007, an assessment of the state of PC development in 47 countries within the WHO European region9 used the simple expedient of ranking countries by services per million population.10,11 A follow-up study focussed on the 27 member states of the European Union (EU).12 This was important in sketching a more detailed method for ranking countries by the level of their PC development. Two types of indicator were used for each country: (1) numbers of PC services per million population and (2) a measure of the ‘vitality’ of PC based on a number of qualitative indicators (existence of a national association, directory of services, physician accreditation, numbers attending congresses of the European Association for Palliative Care (EAPC), publications on PC development). In the ranking, 75% of the score was attributed to the number of services and 25% to the vitality of PC in a country. United Kingdom was ranked first with a score of 100%; countries ranked at between 50% and 85% of the United Kingdom’s level of development were (in order) as follows: Ireland, Sweden, The Netherlands, Poland, France, Spain, Germany, Belgium, Luxembourg, Austria, Italy, Denmark, Finland and Latvia. Countries ranked at between 25% and 50% of the United Kingdom’s level of development were as follows: Lithuania, Hungary, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Slovenia, Cyprus, Romania, Malta, Greece, Portugal and Slovakia; Estonia was ranked at 8% of the United Kingdom’s level of development.

Based on this work, a public health model was developed to combine publicly available data on PC for 27 countries of the EU.13 Aspects of the model included the following: potential needs based on crude death rates in the 65+ years age group population, standards for purchasing power based on Eurostat data as structure parameters, the EAPC Atlas estimates on provision of PC services as a process parameter and global opioid consumption data (mg/capita) as an outcome. Meaningful statistical associations were found between these indicators, suggesting that the availability of PC in a country appears to be related to both potential population needs and population living standards.

Building on this general approach, a study commissioned by the Lien Foundation in Singapore and carried out by the Economist Intelligence Unit was published in 2010.14 This study attempted a ranking of PC development in 40 countries of the world, with a more complex set of indicators in four categories, each with a separate weighting: (1) basic end-of-life healthcare environment (20%), (2) availability of end-of-life care (25%), (3) cost of end-of-life care (15%) and (4) quality of end-of-life (40%). The study again ranked the United Kingdom with the best ‘quality of death’, but some wealthier nations ranked poorly on the index – for instance, Finland was ranked in 28th place and South Korea ranked in 32nd place, while the United States (with the largest spending on healthcare of any country in the world) was ranked in only 9th place overall.

Using data from two major European surveys published in 20079 and 2013,15 we set out to measure changes in PC over time, focussing on three types of specialised service: home care teams (HCTs), hospital support teams (HSTs) and inpatient services. Data on the levels of provision for each specialised service plus the estimate of services required enable us to calculate PC coverage for each type of specialist service across different time periods. PC coverage is the relationship between provision (the number of available services) and demand (the number of services estimated to meet the PC needs of a given population).

Methods

The authors were responsible for the creation, collection and dissemination of the two Atlas survey results (20079,11 and 201315); they are presenting here for the first time a secondary analysis of these data, focussed on the development and coverage of PC services over time. For this purpose, we use the term ‘development’ in the common language sense to denote a general direction in which something is ‘developing’ or ‘changing’.

Specialist services studied

An EAPC White Paper16 describes ‘specialist’ PC services as those where the main activity is the provision of PC. These services generally care for patients with complex and difficult clinical problems; specialist PC therefore requires a high level of education, appropriate staff and other resources. In this study, data relating to three main types of specialist PC services were examined: HCTs consisting of four to five full-time professionals, HSTs (providing specialist PC advice and consultation with at least one physician and a nurse) and inpatient palliative care services (IPCSs) (PC units with an optimal size of 8–12 beds, inpatient hospices with capacity of at least eight beds). Our study method was inspired by work which sought to identify the degree of coverage required for specialised PC services in Portugal.17

Study population

WHO European Region: 53 countries and a population of 879 million people.

Sources of information

Data for PC services were extracted from the EAPC Atlas of Palliative Care in Europe (2007)9 and the EAPC Atlas of Palliative Care in Europe (2013);15 these publications contain information collected by questionnaire in both 2005 and 2012. To complete the questionnaire, each National Palliative Care Association nominated several ‘key persons’ with extensive local knowledge of PC. Where this was not possible, ‘key persons’ were selected either through previous participation in studies or recommendation from other PC institutions, mainly the EAPC Head Office. The mission of this key informant was to provide data relating to the provision of PC services in their respective countries. The Atlas publishes the source from which the informant obtained the information (national directory, studies published, website or own survey or own estimation when no data are published) or when there is a published reference. Also presented in the Atlas are all explanatory notes that are intended to provide an improved interpretation of the data.

A detailed description of the survey questions and collection of results is published elsewhere. The methods of the Atlas studies are described in detail in the respective publications. The data of specialised services are presented in the Atlas in complete form with a National Palliative Care Country Report (the length of each country report is approximately 5–10 pages of quantitative and qualitative information).

The major guarantee that can be provided relating to the accuracy of the data is that (1) a careful process to select the informant, (2) the source of data for each country is openly acknowledged within the Atlas and (3) peer-review process was completed with either the National PC Association or a second or third informant. In both surveys, the election of key informant followed criteria that are published elsewhere; the process was slightly different in the two surveys (improved in the second survey). In both the surveys, the National Association (wherever it existed) and/or a second or third reviewer was involved in the peer-review process after data have been received. There were no changes in the method of data collection (the exception being in relation to the concept of ‘mixed teams’ as described in the text), but the quality of the second survey was improved in several ways: on the basis of experience from the first survey, with better questions that included concrete definitions of services and improved data management. Differences in services reflect changes in the provision of PC over time and not the changes in the way data were collected or by which expert was selected to participate in the survey.

The authors acknowledge that this in an imperfect method to collect information, but it is almost the only possible way to gather facts on PC specialist services in such a large number of European countries at one time. We await a minimum dataset of PC indicators for each country to be incorporated into European public health databases. Demographic data for 2005 were extracted from http://worldgazetteer.com/home.php18 and for 2012 from the World Population Prospects: The 2010 revision of the United Nations for the year (2012).19 Data of population for each country are not shown here.

Design and analysis

As primary data, the total number of specialist PC services (2005–2012) is shown.

A secondary analysis is offered:

Analysis of development of PC services (2005–2012) in each country: by obtaining the difference in the total numbers of services detected between years in a contingency table computing standardised adjusted residual analysis.20 A residual was considered significant when its absolute value was higher than 1.96. This technique was used because it allowed to detect in which countries there were differences described as follows. In a contingency table, the chi-square can be computed using the following formula: . In this formula, the expected value of a cell is computed multiplying the total of the column times by the total of the row and dividing this by the total of the table. The residual is the difference between the observed and the expected values. The residuals should be adjusted because it is not the same as residual of 1 when the expected value is 3, than a residual of 1 when the expected value is 1000. When the adjusted residual is standardised, they can be easily interpreted as Z test. So, those residual with an absolute value higher than 1.96 are statistically significant.

Analysis of the ratio of services per 100,000 inhabitants (2005–2012) in each country: obtaining the difference in ratio of PC services between those years.

Analysis of 2012 coverage of each of the three types of services in each country. According to the EAPC White Paper, the required number of HCT is one team per 100,000 inhabitants; the required number of both HST and IPCS is one team per 200,000 inhabitants. As cited in the White Paper, Nemeth and Rottenhofer21 suggest that PC coverage is the relation between provision (the number of available services) and demand (the number of services estimated to meet the PC needs of a given population). To calculate the demand of services needed, the population of 100,000 units is multiplied by that ratio recommended for 100,000. To simplify the presentation of data in tables, data on 2005 coverage are not shown by country and are presented instead by European Region in Figure 1.

Analysis of the European Development of each type of PC specialised services (2005–2012) is achieved by comparison of the mean of total services and ratio per population between the 2 years. The statistical analysis is by Student’s t-test showing the level of statistical significance of the difference.

Analysis of the PC development in sub-regions of the WHO Europe by the same procedure.

Figure 1.

Changes in coverage in 46 European countries per type of PC service: home care teams (HCTs), hospital support teams (HSTs) and inpatient PC services (IPCSs).

An example for Spain of primary data of HCT, inpatient palliative care unit (IPCU) and HST and secondary analysis of their development (2005–2012) and 2012 coverage is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Example for Spain of primary data of HCTs, IPCUs and HSTs and the secondary analysis of 2005–2012 development and 2012 coverage.

| Indicators (Spain) | Abbr. | Source or formula | HCT | IPCUa | HST |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preliminary information | |||||

| Recommended ratio of services × 100,000 inhabitants | RRS | EAPC White Paper | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| 2005 Spain population | POP05 | http://worldgazetteer.com/home.php | 43,435,136 inhabitants | ||

| 2012 Spain population | POP12 | World Population Prospects | 46,771,596 inhabitants | ||

| Primary data | |||||

| 2005 Number of services detected | SD05 | EAPC Atlas 2006 | 139 | 96 | 27 |

| 2012 Number of services detected | SD12 | EAPC Atlas 2013b | 185 | 112 | 78 |

| Secondary analysis: development of services (2005–2012) | |||||

| Services developed 2005–2012 | – | SD12-SD05 | +46 | +16 | +51 |

| Statistical analysis of the difference | – | Adjusted residual standardised | p < 0.01 | n.s. | p < 0.001 |

| Secondary analysis: ratio services per 100,000 inhabitants | |||||

| 2005 Ratio of services per 100,000 inhabitants | RS05 | SD05/POP05 × 100,000 | 0.32 | 0.22 | 0.06 |

| 2012 Ratio of services per 100,000 inhabitants | RS12 | SD12/POP12 × 100,000 | 0.40 | 0.24 | 0.17 |

| Ratio difference | RS12 − RS05 | 0.08 | 0.02 | 0.11 | |

| Secondary analysis: 2012 coverage | |||||

| 2012 Services needed | SN12 | RRS × (POP12/100,000) | 468 | 234 | 234 |

| 2012 Coverage | – | SD12/SN12 (%) | 185/468 (40%) | 112/234 (48%) | 78/234 (33%) |

HCT: home care team; IPCU: inpatient palliative care unit; HST: hospital support team; EAPC: European Association for Palliative Care; n.s.: not significant.

IPCUs include palliative care units and hospices.

Spain reports the existence of 38 ‘mixed teams’ (providing PC both in hospital and at home) for 2012. This category was not considered in the 2005 survey. For the comparison between years, the total number of mixed teams was divided by two: 19 teams were added to the Atlas data of HCTs and 19 teams were added to inpatient services.

HCT and HST coverage in 2012 includes mixed teams (providing PC both in hospital and at home); the 2005 survey did not specifically request data for mixed teams. In total, 17 of 46 (37%) countries report the existence of mixed teams for 2012 (Albania, Bulgaria, Lithuania, Macedonia, Poland, Slovenia, Austria, Denmark, Luxembourg, Malta, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey and United Kingdom). The total number of mixed teams for these 17 countries was divided by two: one-half of the total was added to HCT and one-half of the total was added to HST. Data for IPCS combine both inpatient PC units and inpatient free-standing hospices.

There were anomalies in data for Andorra (data were not available for 2005), Germany (data on HST were not available for 2012) and The Netherlands (data on HCT were not available for 2005 or HST in 2012). Also anomalies in data occurred in Serbia and Montenegro (the countries were combined in 2005, but separated in 2012).

Results

A total of 46 of 53 (87%) countries provided data covering the two time periods (Tables 2–4). In 2012, there were more than 5000 specialised PC services in Europe (2063 HCT, 1879 IPCS and 1088 HST) – an increase of 1449 since the same survey in 2005. European countries have also developed significantly in relation to the three main types of specialised services (HCT, IPCS and HST) during the period 2005–2012 (Table 5). This improvement was also statistically significant for the Western European (WE) region, but not for Central and Eastern (CEE) region.

Table 2.

Development and coverage of HCTs across WHO European region (2005–2012).

| Country | Total number of HCT services detecteda between 2005 and 2013 |

Rate of HCT services per 100,000 inhabitants (2005–2013) (population changes considered) |

2012 Coverage for HCTb (recommended ratio 1 service per 100,000 inhabitants) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 Atlas survey | 2012 Atlas survey | Difference | p Valuec | 2005 Rate | 2012 Rate | Difference | HCT detected/HCT needed | % | |

| Western Europe | |||||||||

| Andorra | ND | 0 | ND | – | ND | 0.00 | ND | 0/1 | 0 |

| Austria | 17 | 49 | 32 | * | 0.21 | 0.58 | 0.37 | 49/84 | 58 |

| Belgium | 15 | 28 | 13 | n.s. | 0.14 | 0.26 | 0.12 | 28/108 | 26 |

| Cyprus | 2 | 2 | 0 | n.s. | 0.21 | 0.18 | −0.03 | 2/11 | 18 |

| Denmark | 5 | 13 | 8 | n.s. | 0.09 | 0.23 | 0.14 | 13/56 | 23 |

| Finland | 10 | 12 | 2 | n.s. | 0.19 | 0.22 | 0.03 | 12/54 | 22 |

| France | 84 | 118 | 34 | n.s. | 0.14 | 0.19 | 0.05 | 118/635 | 19 |

| Germany | 30 | 180 | 150 | *** | 0.04 | 0.22 | 0.18 | 180/820 | 22 |

| Greece | 9 | 1 | −8 | ** | 0.08 | 0.01 | −0.07 | 1/114 | 1 |

| Iceland | 3 | 4 | 1 | n.s. | 1.02 | 1.22 | 0.20 | 4/3 | 133 |

| Ireland | 14 | 35 | 21 | n.s. | 0.35 | 0.76 | 0.42 | 35/46 | 76 |

| Israel | 14 | 20 | 6 | n.s. | 0.20 | 0.26 | 0.06 | 20/77 | 26 |

| Italy | 153 | 312 | 159 | * | 0.26 | 0.51 | 0.25 | 312/610 | 51 |

| Luxembourg | 2 | 3 | 1 | n.s. | 0.44 | 0.57 | 0.13 | 3/5 | 60 |

| Malta | 0 | 2 | 2 | n.s. | 0.00 | 0.36 | 0.36 | 2/4 | 50 |

| The Netherlands | ND | 44 | ND | – | ND | 0.26 | ND | 44/167 | 26 |

| Norway | 1 | 20 | 19 | ** | 0.02 | 0.40 | 0.38 | 20/50 | 40 |

| Portugal | 3 | 12 | 9 | n.s. | 0.03 | 0.11 | 0.08 | 12/107 | 11 |

| Spain | 139 | 185 | 46 | ** | 0.32 | 0.40 | 0.08 | 185/468 | 40 |

| Sweden | 50 | 107 | 57 | n.s. | 0.55 | 1.13 | 0.57 | 107/95 | 113 |

| Switzerland | 14 | 21 | 7 | n.s. | 0.19 | 0.27 | 0.08 | 21/77 | 27 |

| Turkey | 0 | 5 | 5 | n.s. | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 5/745 | 1 |

| United Kingdom | 356 | 389 | 33 | n.s. | 0.59 | 0.62 | 0.03 | 389/628 | 62 |

| Central and Eastern Europe | |||||||||

| Albania | 4 | 2 | −2 | n.s. | 0.13 | 0.08 | −0.05 | 3/32 | 9 |

| Armenia | 8 | 4 | −4 | * | 0.27 | 0.13 | −0.14 | 4/31 | 13 |

| Azerbaijan | 1 | 0 | −1 | n.s. | 0.01 | 0.00 | −0.01 | 0/94 | 0 |

| Belarus | 1 | 5 | 4 | n.s. | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 5/95 | 5 |

| Bulgaria | 25 | 19 | −6 | ** | 0.33 | 0.26 | −0.08 | 19/74 | 26 |

| Croatia | 3 | 4 | 1 | n.s. | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.02 | 4/44 | 9 |

| Czech Republic | 4 | 4 | 0 | n.s. | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 4/106 | 4 |

| Estonia | 0 | 15 | 15 | ** | 0.00 | 1.12 | 1.12 | 15/13 | 112 |

| Georgia | 1 | 13 | 12 | * | 0.02 | 0.30 | 0.28 | 13/43 | 30 |

| Hungary | 28 | 69 | 41 | * | 0.28 | 0.69 | 0.42 | 69/99 | 69 |

| Kazakhstan | 2 | 1 | −1 | n.s. | 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 1/164 | 1 |

| Latvia | 0 | 0 | 0 | n.s. | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0/22 | 0 |

| Lithuania | 3 | 15 | 12 | * | 0.09 | 0.44 | 0.35 | 15/33 | 45 |

| Macedonia | 2 | 4 | 2 | n.s. | 0.10 | 0.17 | 0.07 | 4/21 | 19 |

| Moldova | 13 | 5 | −8 | ** | 0.33 | 0.14 | −0.19 | 5/35 | 14 |

| Montenegro | ND | 0 | ND | – | ND | 0.00 | ND | 0/6 | 0 |

| Poland | 232 | 322 | 90 | ** | 0.61 | 0.84 | 0.23 | 322/383 | 84 |

| Romania | 10 | 15 | 5 | n.s. | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 15/214 | 7 |

| Russia | 0 | 0 | 0 | n.s. | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0/1427 | 0 |

| Serbia | ND | 1 | ND | – | ND | 0.01 | ND | 1/98 | 1 |

| Slovakia | 0 | 0 | 0 | n.s. | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0/55 | 0 |

| Slovenia | 2 | 1 | −1 | n.s. | 0.10 | 0.05 | −0.05 | 1/20 | 5 |

| Ukraine | 1 | 3 | 2 | n.s. | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 3/449 | 1 |

| Europe | 1261 | 2063 | 801 | – | 0.17 | 0.31 | 0.13 | 2063/8526 | 24 |

| Western Europe | 921 | 1561 | 640 | – | 0.23 | 0.40 | 0.17 | 1561/4965 | 31 |

| Central and Eastern Europe | 340 | 502 | 161 | – | 0.12 | 0.21 | 0.10 | 502/3561 | 14 |

HCT: home care team; WHO: World Health Organization; ND: not determined; n.s.: not significant.

In total, 17 of 46 (37%) countries report the existence of ‘mixed teams’ (providing PC both in hospital and at home) for 2012. This category was not considered in the 2005 survey. For the comparison between years, the total number of mixed teams for these 17 countries in 2012 was divided by two: one-half of the total was added to HCTs and the other half was added to inpatient services. See details of these countries in the text.

Services needed estimate following the proportion suggested by the EAPC White Paper: 1 HCT per 100,000 inhabitants (2012 country population data used).

Adjusted residual standardised analysis: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

Table 3.

Development and coverage of IPCSs across WHO European region (2005–2012).

| Country | Total number of IPCS services detecteda between 2005 and 2013 |

Rate of IPCS services per 100,000 inhabitants (2005–2013) (population changes considered) |

2012 Coverage for IPCSb (recommended ratio 0.5 services per 100,000 inhabitants) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 2012 | Difference | p Valuec | 2005 Rate | 2012 Rate | Difference | IPCS detected/IPCS needed | % | |

| Western Europe | |||||||||

| Andorra | ND | 0 | ND | n.s. | ND | 0.00 | ND | 0/0 | 0 |

| Austria | 25 | 37 | 12 | n.s. | 0.31 | 0.44 | 0.13 | 37/42 | 88 |

| Belgium | 29 | 51 | 22 | n.s. | 0.28 | 0.47 | 0.20 | 51/54 | 94 |

| Cyprus | 1 | 1 | 0 | n.s. | 0.11 | 0.09 | −0.02 | 1/6 | 17 |

| Denmark | 7 | 28 | 21 | ** | 0.13 | 0.50 | 0.37 | 28/28 | 100 |

| Finland | 6 | 10 | 4 | n.s. | 0.11 | 0.19 | 0.07 | 10/27 | 37 |

| France | 78 | 107 | 29 | n.s. | 0.13 | 0.17 | 0.04 | 107/317 | 34 |

| Germany | 245 | 420 | 175 | ** | 0.30 | 0.51 | 0.22 | 420/410 | 102 |

| Greece | 0 | 1 | 1 | n.s. | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 1/57 | 2 |

| Iceland | 2 | 2 | 0 | n.s. | 0.68 | 0.61 | −0.07 | 2/2 | 100 |

| Ireland | 8 | 9 | 1 | n.s. | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.00 | 9/23 | 39 |

| Israel | 9 | 10 | 1 | n.s. | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.00 | 10/38 | 26S |

| Italy | 95 | 175 | 80 | * | 0.16 | 0.29 | 0.12 | 175/305 | 57 |

| Luxembourg | 1 | 5 | 4 | n.s. | 0.22 | 0.76 | 0.54 | 4/3 | 133 |

| Malta | 0 | 1 | 1 | n.s. | 0.00 | 0.24 | 0.24 | 1/2 | 50 |

| The Netherlands | 88 | 212 | 124 | *** | 0.54 | 1.27 | 0.73 | 212/84 | 253 |

| Norway | 14 | 17 | 3 | n.s. | 0.30 | 0.34 | 0.04 | 17/25 | 68 |

| Portugal | 4 | 22 | 18 | ** | 0.04 | 0.21 | 0.17 | 22/53 | 41 |

| Spain | 96 | 112 | 16 | n.s. | 0.22 | 0.24 | 0.02 | 112/234 | 48 |

| Sweden | 45 | 38 | −7 | * | 0.50 | 0.40 | −0.10 | 38/47 | 81 |

| Switzerland | 17 | 25 | 8 | n.s. | 0.23 | 0.32 | 0.10 | 25/39 | 64 |

| Turkey | 11 | 25 | 14 | n.s. | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 25/373 | 7 |

| United Kingdom | 221 | 220 | −1 | n.s. | 0.37 | 0.35 | −0.02 | 220/314 | 70 |

| Central and Eastern Europe | |||||||||

| Albania | 1 | 0 | −1 | n.s. | 0.03 | 0.00 | −0.03 | 0/16 | 0 |

| Armenia | 6 | 0 | −6 | ** | 0.20 | 0.00 | −0.20 | 0/16 | 0 |

| Azerbaijan | 0 | 0 | 0 | n.s. | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0/47 | 0 |

| Belarus | 0 | 15 | 15 | *** | 0.00 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 15/48 | 31 |

| Bulgaria | 16 | 22 | 6 | n.s. | 0.21 | 0.30 | 0.08 | 22/37 | 59 |

| Croatia | 0 | 0 | 0 | n.s. | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0/22 | 0 |

| Czech Republic | 10 | 17 | 7 | n.s. | 0.10 | 0.16 | 0.06 | 17/53 | 32 |

| Estonia | 0 | 0 | 0 | n.s. | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0/7 | 0 |

| Georgia | 1 | 2 | 1 | n.s. | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 2/22 | 9 |

| Hungary | 11 | 13 | 2 | n.s. | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.02 | 13/50 | 26 |

| Kazakhstan | 5 | 5 | 0 | n.s. | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 5/85 | 6 |

| Latvia | 5 | 6 | 1 | n.s. | 0.22 | 0.27 | 0.05 | 6/11 | 54 |

| Lithuania | 6 | 9 | 3 | n.s. | 0.17 | 0.27 | 0.10 | 9/16 | 56 |

| Macedonia | 2 | 12 | 10 | * | 0.10 | 0.58 | 0.48 | 12/10 | 120 |

| Moldova | 0 | 2 | 2 | n.s. | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 2/18 | 11 |

| Montenegro | ND | 0 | ND | n.s. | ND | 0.00 | ND | 0/3 | 0 |

| Poland | 128 | 145 | 17 | * | 0.34 | 0.38 | 0.04 | 145/192 | 76 |

| Romania | 9 | 25 | 16 | n.s. | 0.04 | 0.12 | 0.07 | 25/107 | 23 |

| Russia | 107 | 62 | −45 | *** | 0.07 | 0.04 | −0.03 | 62/714 | 9 |

| Serbia | 0 | 0 | 0 | n.s. | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0/49 | 0 |

| Slovakia | 6 | 11 | 5 | n.s. | 0.11 | 0.20 | 0.09 | 11/27 | 41 |

| Slovenia | 4 | 6 | 2 | n.s. | 0.20 | 0.29 | 0.09 | 6/10 | 60 |

| Ukraine | 14 | 0 | −14 | *** | 0.03 | 0.00 | −0.03 | 0/225 | 0 |

| Europe | 1333 | 1879 | 546 | – | 0.16 | 0.25 | 0.09 | 1879/4263 | 44 |

| Western Europe | 1002 | 1527 | 525 | – | 0.23 | 0.35 | 0.13 | 1527/2482 | 62 |

| Central and Eastern Europe | 331 | 352 | 21 | – | 0.09 | 0.14 | 0.05 | 352/1780 | 20 |

IPCS: inpatient palliative care service; WHO: World Health Organization; ND: not determined; n.s.: not significant.

In total, 17 of 46 (37%) countries report the existence of ‘mixed teams’ (providing PC both in hospital and at home) for 2012. This category was not considered in the 2005 survey. For the comparison between years, the total number of mixed teams for these 17 countries in 2012 was divided by two: one-half of the total was added to HCTs and the other half was added to inpatient services. See details of these countries in the text.

Services needed estimate following the proportion suggested by the EAPC White Paper: 5 IPCSs (8–12 beds) or hospice (8 beds) per million inhabitants (2012 country population data used).

Adjusted residual standardised analysis: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

Table 4.

Development and coverage of HSTs across WHO European region (2005–2012).

| Country | Total number of HST services detected between 2005 and 2013 |

Rate of HST services per 100,000 inhabitants (2005–2013) (population changes considered) |

2012 Coverage for HSTa (recommended ratio 0.5 services/100,000 inhabitants) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 2012 | Difference | p Valueb | 2005 Rate | 2012 Rate | Difference | HST detected/HST needed | % | |

| Western Europe | |||||||||

| Andorra | ND | 1 | ND | – | N/A | 1.14 | N/A | 1/1 | 100 |

| Austria | 10 | 29 | 19 | ** | 0.12 | 0.34 | 0.22 | 29/42 | 69 |

| Belgium | 77 | 116 | 39 | * | 0.74 | 1.08 | 0.34 | 116/54 | 215 |

| Cyprus | 0 | 0 | 0 | n.s. | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0/6 | 0 |

| Denmark | 6 | 13 | 7 | n.s. | 0.11 | 0.23 | 0.12 | 13/28 | 46 |

| Finland | 10 | 1 | −9 | ** | 0.19 | 0.02 | −0.17 | 1/27 | 4 |

| France | 309 | 260 | −49 | *** | 0.51 | 0.41 | −0.10 | 260/317 | 82 |

| Germany | 56 | ND | NDc | – | 0.07 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| Greece | 20 | 0 | −20 | *** | 0.18 | 0.00 | −0.18 | 0/57 | 0 |

| Iceland | 1 | 1 | 0 | n.s. | 0.34 | 0.30 | −0.03 | 1/2 | 50 |

| Ireland | 22 | 39 | 17 | n.s. | 0.55 | 0.85 | 0.31 | 39/23 | 170 |

| Israel | 3 | 3 | 0 | n.s. | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 3/39 | 8 |

| Italy | 0 | 0 | 0 | n.s. | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0/304 | 0 |

| Luxembourg | 1 | 3 | 2 | n.s. | 0.22 | 0.57 | 0.35 | 3/3 | 100 |

| Malta | 1 | 2 | 1 | n.s. | 0.26 | 0.36 | 0.10 | 2/3 | 67 |

| The Netherlands | 50 | ND | ND | – | 0.31 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| Norway | 16 | 19 | 3 | n.s. | 0.35 | 0.38 | 0.04 | 19/25 | 77 |

| Portugal | 1 | 20 | 19 | *** | 0.01 | 0.19 | 0.18 | 20/53 | 38 |

| Spain | 27 | 78 | 51 | *** | 0.06 | 0.17 | 0.10 | 78/234 | 33 |

| Sweden | 10 | 13 | 3 | n.s. | 0.11 | 0.14 | 0.03 | 13/47 | 28 |

| Switzerland | 7 | 16 | 9 | n.s. | 0.09 | 0.20 | 0.11 | 16/39 | 41 |

| Turkey | 10 | 55 | 45 | *** | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 55/373 | 15 |

| United Kingdom | 305 | 360 | 55 | n.s. | 0.51 | 0.57 | 0.06 | 360/314 | 115 |

| Central and Eastern Europe | |||||||||

| Albania | 0 | 1 | 1 | n.s. | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 1/16 | 1 |

| Armenia | 10 | 0 | −10 | *** | 0.34 | 0.00 | −0.34 | 0/15 | 0 |

| Azerbaijan | 0 | 0 | 0 | n.s. | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0/48 | 0 |

| Belarus | 1 | 0 | −1 | n.s. | 0.01 | 0.00 | −0.01 | 0/48 | 0 |

| Bulgaria | 0 | 9 | 9 | ** | 0.00 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 9/37 | 24 |

| Croatia | 0 | 0 | 0 | n.s. | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0/22 | 0 |

| Czech Republic | 1 | 2 | 1 | n.s. | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 2/53 | 4 |

| Estonia | 0 | 0 | 0 | n.s. | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0/7 | 0 |

| Georgia | 0 | 1 | 1 | n.s. | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 1/21 | 5 |

| Hungary | 4 | 3 | −1 | n.s. | 0.04 | 0.03 | −0.01 | 3/50 | 6 |

| Kazakhstan | 0 | 0 | 0 | n.s. | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0/82 | 0 |

| Latvia | 0 | 7 | 7 | ** | 0.00 | 0.31 | 0.31 | 7/11 | 63 |

| Lithuania | 1 | 1 | −1 | n.s. | 0.03 | 0.02 | −0.01 | 1/16 | 6 |

| Macedonia | 2 | 7 | 5 | n.s. | 0.10 | 0.31 | 0.22 | 7/10 | 70 |

| Moldova | 0 | 1 | 1 | n.s. | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 1/18 | 6 |

| Montenegro | ND | 0 | ND | – | ND | 0.00 | ND | 0/3 | ND |

| Poland | 2 | 9 | 7 | * | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 9/192 | 5 |

| Romania | 2 | 2 | 0 | n.s. | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 2/107 | 2 |

| Russia | 17 | 0 | −17 | *** | 0.01 | 0.00 | −0.01 | 0/714 | 0 |

| Serbia | ND | 1 | ND | – | ND | 0.01 | ND | 1/49 | 2 |

| Slovakia | 0 | 0 | 0 | n.s. | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0/27 | 0 |

| Slovenia | 2 | 17 | 15 | ** | 0.10 | 0.83 | 0.73 | 17/10 | 170 |

| Ukraine | 0 | 0 | 0 | n.s. | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0/225 | 0 |

| Europe | 984 | 1088 | 102 | – | 0.12 | 0.19 | 0.06 | 1088/3769 | 29 |

| Western Europe | 942 | 1028 | 85 | – | 0.22 | 0.30 | 0.08 | 1028/1989 | 52 |

| Central and Eastern Europe | 42 | 60 | 17 | – | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 60/1780 | 3 |

HST: home support team; WHO: World Health Organization; ND: not determined; N/A: not available; n.s.: not significant.

Services needed estimate following the proportion suggested by the EAPC White Paper: 0.5 HSTs per million inhabitants (2012 country population data used).

Adjusted residual standardised analysis: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

For Germany in the EAPC Atlas, the data of HST were unavailable. Following publication of the Atlas, the number was revealed as 90 HSTs. That means six services less than the previous 2005 survey. The 2012 coverage would therefore be 50 of 410 (12%).

Table 5.

Analysis of the European Development of specialised PC services (2005–2012) by comparison of the mean of total services and ratio per population.

| Type of service | Total specialised PC services |

Ratio of specialised PC services per 100,000 inhabitants |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 |

2012 |

2005–2012 Mean differencea |

2005 |

2012 |

2005–2012 Mean differencea |

|||||

| Mean | Mean | Mean difference | 95% Conf. interval | p Value | Mean | Mean | n | 95% Conf. interval | p Value | |

| Western Europe | ||||||||||

| HCT | 43.86 | 72.24 | 28.38 | (7.82/48.94) | 0.009* | 0.23 | 0.4 | 0.17 | (0.09/0.24) | 0.001* |

| IPCS | 45.54 | 69.41 | 23.86 | (3.87/43.85) | 0.022* | 0.23 | 0.35 | 0.13 | (0.04/0.22) | 0.007* |

| HST | 41.80 | 51.35 | 9.55 | (−1.91/21.01) | 0.097 | 0.22 | 0.3 | 0.08 | (0.01/0.15) | 0.035* |

| Central and Eastern Europe | ||||||||||

| HCT | 16.19 | 23.83 | 7.64 | (−2.13/17.42) | 0.119 | 0.12 | 0.21 | 0.10 | (−0.03/0.22) | 0.128 |

| IPCS | 15.05 | 16.00 | 0.95 | (−4.55/6.46) | 0.722 | 0.09 | 0.14 | 0.05 | (−0.01/0.10) | 0.079 |

| HST | 2.00 | 2.79 | 0.79 | (−2.10/3.68) | 0.577 | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.05 | (−0.04/0.14) | 0.232 |

| Total WHO Europe | ||||||||||

| HCT | 30.02 | 48.04 | 18.00 | (6.65/29.38) | 0.003* | 0.17 | 0.31 | 0.13 | (0.06/0.20) | 0.001* |

| IPCS | 30.30 | 42.70 | 12.41 | (1.86/22.95) | 0.022* | 0.16 | 0.25 | 0.09 | (0.04/0.14) | 0.001* |

| HST | 21.41 | 26.48 | 5.06 | (−0.62/10.75) | 0.080 | 0.12 | 0.19 | 0.06 | (0.01/0.12) | 0.022* |

PC: palliative care; HCT: home care team; IPCS: inpatient palliative care service; HST: hospital support team; WHO: World Health Organization.

Student’s t paired test.

Statistical significance: p < 0.05.

Despite the significant improvement, estimations of coverage (Figure 1) for IPCS, HCT and HST are 62%, 52% and 31% for WE and 20%, 14% and 3% for CEE, respectively. IPCS demonstrated the most positive development overall and also attained the highest rate of coverage. The second most developed type of specialised PC service was the HST; a significant improvement was revealed during the 7-year period that we examined in WE, although this type of service was almost non-existent in CEE throughout this period.

Tables 2–4 show the changes in the total number of each type of service country by country, the changes in rate per 100,000 habitants and the estimation for 2012 coverage with statistical analysis of the WHO Europe and sub-regions. Of the 46 countries analysed, 21 countries (46%) demonstrated a significant development in services. These countries were, in WE, as follows: Austria (HCT and HST), Belgium (HST), Denmark (IPCS), Finland (HST), Germany (HCT and IPCS), Italy (HCT and IPCS), The Netherlands (IPCS), Norway (HCT), Portugal (IPCS and HST), Spain (HCT and HST) and Sweden (IPCS); in CEE, only Poland developed significantly across all three types of PC services. Other countries with significant development in services were Belarus (IPCS), Bulgaria (HCT and HST), Estonia (HCT), Georgia (HCT), Hungary (HCT), Latvia (HST), Lithuania (HCT), Macedonia (IPCS) and Slovenia (HST).

In addition to these significant changes, improvement in the total number of services and the ratios per population has been seen in a majority of other countries without reaching statistical level in the difference. In some instances, countries striving to improve PC services more than doubled their absolute number of services over the period. The more representative of these include the following: Portugal (from 8 to 54 services, +575%), Denmark (from 18 to 54, +200%) and Germany (from 331 to 690, +108%) in WE; Slovenia (from 8 to 24 services (300%)), Romania (from 21 to 42 (200%)), Georgia (from 2 to 16 services (800%)) and Latvia (from 5 to 13 (260%)) in CEE.

Provision of IPCS (hospital units and hospices considered) is greater than any other kind of PC services with coverage higher than 80% in The Netherlands, Luxembourg, Iceland, Germany, Denmark, Belgium, Austria, Sweden and Macedonia. The best HCT coverage was found in Iceland (122%), Sweden (113%), Estonia (112%), Poland (84%) and Ireland (76%). Complete PC coverage for inpatients was found in Belgium, Denmark, The Netherlands and Germany with 100% coverage. Impressive development of HST coverage was found in Belgium, Ireland, United Kingdom, Luxembourg, Andorra and France with around 100% coverage. The most striking results were revealed in the coverage of IPCS: 19 countries have almost 50% coverage in this type of service.

United Kingdom and Iceland are the countries with the most balanced average coverage across the three types of PC service with higher than 60% coverage across all services. In CEE, there are good examples of IPCS in Republic of Macedonia (116%) and HST in Slovenia (167%).

Discussion

The results of the article provide the most comprehensive information available on the coverage and development of PC services in Europe at the present time. Healthcare professionals and National PC Associations could use these data for advocacy to promote PC development comparing their development with that of neighbouring countries. The authors intentionally maintain a low profile in the discussion with only a few global and international comments, as they prefer to estimate national or regional development on the basis of input from local PC activists who ‘give voice’ to each country; the tables detailed in this article ‘speak for themselves’ without the need for many additional comments. For more concrete interpretation of the country, data could be useful to complete the information with the Atlas country report: this could permit a more comprehensive and detailed analysis. Researchers could also utilise the data for other secondary analysis as demonstrated in a recent publication.22

Viewing the data overall, significant changes have occurred in WE countries in the three types of specialised services between 2005 and 2012. In CEE, the trend is also increasing albeit at a slower pace; with exceptions, the total number of specialised PC services in the CEE region is very limited (Figure 1).

In CEE, HSTs are almost non-existent with few exceptions despite this being the easy, cheapest and most effective way to integrate PC in the health system, being there, in the hospitals, with the other specialist care. In contrast, most US hospitals have PC services in hospitals.23 Healthcare professionals and policy makers are called to promote this type of specialist PC services.

In many countries, the number of HCT doubled between 2005 and 2012. This could have resulted from the efforts of health systems to facilitate a dying at home and to save money by avoiding prolonged hospital stays. However, the total coverage is still very low with most countries achieving less than 25% of what is needed. We have calculated that there is a lack of more than 8500 HCT that means at least two or three times this number of PC professionals that must be trained in the future.

Our results demonstrate that between 2005 and 2012, there has been significant change in specialised PC services in 12–14 of 46 countries of Europe. It is also meaningful to see that in almost all countries, the availability of PC services per population is higher after this 7-year period. However, development of specialised PC services in a number of European countries has been slow and limited, with only IPCS coverage in WE increasing at more than +20% during this period. The development of PC services remains insufficient because the average coverage across all three types of specialised service is less than 40% when set against EAPC guidelines; the exception being the coverage of IPCS in WE (approximately 60%) and the coverage of HST in WE (52%). It is noted that in few countries, coverage of some services is over 100%; this could mean that the White Paper estimates are too low, or that a specific country has particular requirements (or that there is over provision in relation to population need). In CEE, coverage of specialised PC services is very low; there is HCT coverage for only 1 in 10 patients that require it and the coverage of HST is negligible.

In relation to the handful of countries that demonstrate a negative development in PC coverage, it should be taken into account that the size of a population in some countries has increased, thereby skewing the ratio of services/population. Also, a negative development may be attributed to use of more rigorous definitions of a service included in the EAPC White Paper (this is applied, for example, in Greece, Finland and Republic of Moldova).

Limitations to the study and implications for the future

This has been an ecological study in which the unit of analysis corresponds to geographically well-defined populations or communities in European countries or regions. This type of study works with aggregated information, but not with individual information. Therefore, the study cannot say specifically how many people benefit from PC services and, for example, coverage does not mean that all patients who need the service receive the appropriate level of service.

The use of ‘key persons’ as a primary source of information is widely accepted in health service studies, and particularly in those focussing on the end-of-life,24,25 though it is acknowledged that this source of data collection may also be prone to problems.26 We sought to overcome these difficulties and to increase the validity of responses in a number of ways: multiple informants per country, a request for both quantitative and qualitative information and independent verification of data through a peer-review consensus process.

We have calculated only the crude value of the indicators and we did not perform any age adjustment or epidemiological evaluation of cancer incidence in the countries (although this could be undertaken in the future).

Measuring the international development of PC is a difficult and challenging task. Data are presented here as a ‘work in progress’ using various sources of verification. Within this context, we would welcome suggestions or comments that could potentially improve the methods described in this article. However, we do believe that the results of the article provide the most comprehensive data available on PC services in Europe at the present time.

Although there has been an overall positive development in PC coverage in Europe between 2005 and 2012, the number of services available in many countries is still insufficient to meet the PC needs of the population and falls well below EAPC population-based guidelines.

Acknowledgments

The Task Force would like to take this opportunity to thank the 55 ‘key persons’ who provided invaluable primary data for the compilation of this article and other 46 professionals who reviewed and verified data from their country (see additional information in annex). We also thank Professor Sheila Payne for comments on an earlier draft of this article.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding: Support for this work was received from the Institute for Culture and Society (ICS) of the University of Navarra, particularly since 2012 as part of the ATLANTES Project (unrestricted research grant ad hoc). Additional support has been received from the Fondazione Maruzza Lefebvre D’Ovidio Onlus, in Rome (unrestricted research grant ad hoc), and the University of Glasgow Knowledge Exchange Fund (unrestricted grant ad hoc).

Supplementary materials: Any of our original data are available under justified request.

References

- 1. World Health Organization (WHO). Strengthening of palliative care as a component of integrated treatment throughout the life course. Geneva: WHO, http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA67/A67_31-en.pdf (accessed 4 April–27 May 2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Clark D, Wright M. The international observatory on end of life care: a global view of palliative care development. J Pain Symptom Manage 2007; 33: 542–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wright M, Clark D. Hospice and Palliative Care Development in Africa: a review of developments and challenges. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bingley A, Clark D. A comparative review of palliative care development in six countries represented by the Middle East Cancer Consortium (MECC). J Pain Symptom Manage 2009; 37: 287–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wright M. Hospice and palliative care in Southeast Asia. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 6. McDermott E, Selman L, Wright M, et al. Hospice and palliative care development in India: a multi-method review of services and experiences. J Pain Symptom Manage 2008; 35: 583–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wright M, Wood J, Lynch T, et al. Mapping levels of palliative care development: a global view. J Pain Symptom Manage 2008; 35: 469–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lynch T, Connor S, Clark D. Mapping levels of palliative care development: a global update. J Pain Symptom Manage 2013; 45: 1094–2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Centeno C, Clark D, Lynch T, et al. EAPC Atlas of palliative care in Europe. Houston, TX: IAHPC Press, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Clark D, Centeno C. Palliative care in Europe: an emerging approach to comparative analysis. Clin Med 2006; 6: 197–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Centeno C, Clark D, Rocafort J, et al. Facts and indicators on PC development in 52 countries of the WHO European region: results of an EAPC Task Force. Palliat Med 2007; 21: 463–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Martin-Moreno J, Harris M, Gorgojo L, et al. Palliative Care in the European Union. European Economic and Scientific Policy Department 2008. IP/A/ENVI/ST/2007-22; PE404.899, http://www.europarl.europa.eu/activities/committees/studies/download.do?file=21421 (accessed March 2010).

- 13. Hasselaar J, Centeno C, Engels Y, et al. Towards a public health model for PC in Europe. In: 13th world congress of the European Association for PC, Prague, 30 May–2 June 2013. (Book of abstract P2-350: 206). [Google Scholar]

- 14.http://www.lifebeforedeath.com/qualityofdeath/index.shtml (accessed March 2011).

- 15. Centeno C, Lynch T, Donea O, et al. EAPC Atlas of PC in Europe 2013-Full Edition. Milano: EAPC, http://hdl.handle.net/10171/29291 (2013, accessed 15 June 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 16. Radbruch L, Payne S. EAPC White Paper on standards and norms for hospice and PC: part 2. Eur J Palliat Care 2010; 17: 22–33. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Capelas ML, Flores R, Roque E, et al. Palliative care services in Portugal: what is our coverage of needs? In: 12th congress of the European Association for Palliative Care, Lisbon, 18–21 May 2011. (Book of abstract. P345: 130). [Google Scholar]

- 18. http://worldgazetteer.com/home.php

- 19. United Nations (UN). World Population Prospects: The 2010 revision of the United Nations for the year 2012. http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/trends/population-prospects_2010_revision.shtml

- 20. Haberman SJ. The analysis of residuals in cross-classified tables. Biometrics 1973; 29(1): 205–220. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Nemeth C, Rottenhofer I. Abgestufte Hospiz- und Palliativversorgung in Österreich. Wien: Österreichisches Bundesinstitut für Gesundheitswesen, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chambaere K, Bernheim JL. Does legal physician-assisted dying impede development of palliative care? The Belgian and Benelux experience. J Med Ethics. Epub ahead of print 3 February 2015. DOI: 10.1136/medethics-2014-102116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Dumanovsky T. Growth of Palliative Care in U.S. Hospitals 2014 Snapshot, https://www.capc.org/topics/metrics-and-measurement-palliative-care/ (accessed 15 March 2015).

- 24. Pivodic L, Pardon K, Van den Block L, et al. EURO IMPACT. Palliative care service use in four European countries: a cross-national retrospective study via representative networks of general practitioners. PLoS ONE 2013; 8: e84440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Van den Block L, Deschepper R, Bossuyt N, et al. Care for patients in the last months of life: the Belgian Sentinel Network Monitoring End-of-Life Care study. Arch Intern Med 2008; 168: 1747–1754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Loucka M, Payne S, Brearley S. How to measure the international development of PC? A critique and discussion of current approaches. J Pain Symptom Manage 2013; 47: 154–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]