Abstract

Objectives:

The initial goal was to validate the use of a self-report measure of disability in the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF). The main goal was to document the extent of disability in personnel with and without mental disorders.

Methods:

Data were obtained from the 2013 Canadian Forces Mental Health Survey; the sample included 6700 Regular Forces personnel. Disability was measured with the 12-item version of the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule (WHODAS-2); established cut points were used to demarcate severe, moderate, minimal, and no disability. The following recent (past-year) and remote (lifetime but not past-year) disorders were assessed with diagnostic interviews: posttraumatic stress disorder, major depressive episode, generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, and alcohol use disorder.

Results:

The WHODAS-2 showed good internal consistency (α = 0.89) and a 1-factor structure. Most personnel had no disability (59.2%) or minimal disability (30.8%). However, an important minority had moderate or severe disability (8.4% and 1.6%, respectively). Individuals with recent disorders reported greater disability than those without lifetime disorders, although many had minimal or no disability (41.2% and 24.7%, respectively). Disability increased with the number of recent disorders. Relative to those without lifetime disorders, individuals with remote disorders showed slightly greater disability, but most had no disabilty (57.1%) or minimal disability (35.0%).

Conclusions:

The 12-item WHODAS-2 is a valid measure of disability in the CAF. Mental disorders may be important drivers of disability in this population, although limited residual disability is seen in individuals with remote disorders.

Keywords: mental disorders, disability, military, World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule

Abstract

Objectif:

L’objectif initial était de valider l’utilisation d’un instrument d’auto-évaluation d’invalidité dans les Forces armées canadiennes (FAC). Le but principal était de documenter l’étendue de l’invalidité chez le personnel avec et sans troubles mentaux.

Méthode:

Les données ont été obtenues de l’Enquête sur la santé mentale des Forces armées canadiennes de 2013; l’échantillon comprenait 6 700 membres de la Force régulière. L’invalidité était mesurée par la version en 12 items du WHODAS-2; des points de découpage établis ont servi à démarquer l’invalidité grave, modérée, minimale et nulle. Les troubles suivants récents (l’année précédente) et distants (de durée de vie mais pas l’année précédente) ont été évalués par des entrevues diagnostiques : trouble de stress post-traumatique, épisode de dépression majeure, trouble d’anxiété généralisée, trouble panique, et trouble lié à l’alcool.

Résultats:

Le WHODAS-2 a révélé une bonne cohésion interne (α = 0,89) et une structure unifactorielle. Pour la plupart, le personnel n’avait pas d’invalidité (59,2 %) ou une invalidité minimale (30,8 %). Cependant, une importante minorité avait une invalidité modérée ou grave (8,4 % et 1,6 %, respectivement). Les personnes ayant des troubles récents ont déclaré une plus grande invalidité que ceux n’ayant pas de troubles de durée de vie, même si beaucoup avaient une invalidité minimale ou nulle (41,2 % et 24,7 %, respectivement). L’invalidité augmentait avec le nombre de troubles récents. Relativement à ceux n’ayant pas de troubles de durée de vie, ceux ayant des troubles distants indiquaient une invalidité légèrement plus élevée, mais la plupart n’avait pas d’invalidité (57,1 %) ou une invalidité minimale (35,0 %).

Conclusions:

Le WHODAS-2 en 12 items est une mesure valide de l’invalidité dans les FAC. Les troubles mentaux peuvent être d’importants facteurs d’invalidité dans cette population, bien qu’une invalidité résiduelle limitée s’observe chez ceux ayant des troubles distants.

Clinical Implications

Optimal treatment of past-year mental disorders may mitigate the burden of disability in the Canadian Armed Forces.

The broad range of disability seen with past-year mental disorders argues for individualized assessment and targeted rehabilitation of disability.

Military personnel with a remote mental disorder largely have little or no residual disability.

Limitations

The WHODAS-2 was not developed for use in military populations.

The cross-sectional nature of this study does not allow for conclusions regarding causality between mental disorders and disability.

This study did not account for potentially important confounders.

Mental disorders are known to have a strong, negative effect on the well-being of individuals. In the workplace, such disorders can result in physical, cognitive, and social impairments. These can, in turn, lead to disability, including activity limitations and participation restrictions. Disability represents a significant problems for employers, because it can lead to lower productivity,1 higher turnover, and increased costs as a result of disability benefits.2

Differences in the military workforce, the military workplace, and the nature of military duties may drive differences in mental disorder–related disability in military versus civilian populations. For example, operational duties can expose military personnel to psychological trauma, leading to an increased risk of developing a service-related mental disorder.3–5 There are also differences in the prevalence of mental disorders such as depression and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in military personnel relative to civilians.6–9 Moreover, the stringent fitness standards in military organizations can result in those who develop a mental disorder being found unfit for service,10 leading to substantial unwanted turnover.11 The resulting costs may be particularly impactful in military organizations, which invest heavily in training in order to prepare their employees for the unique demands of the military workplace.

Although a number of recent studies highlight the effects of mental disorders on disability in military organizations,12–17 the existing research is limited in several respects.

First, this research has focused largely on the US military, and the findings may not be generalisable to the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) because of variations in demographic factors, rates of mental disorders,18 and occupational standards across militaries, as well as disability measurement scales across studies, all of which may impede cross-national comparisons. Moreover, studies conducted with individuals in the CAF have only examined deployment-related mental disorders and occupational outcomes that do not assess how these individuals with diagnosed mental disorders are functioning more generally.10,19 Second, existing studies have focused primarily on individual past-year disorders.12,17 Little research has explored the compounding effect of comorbidity on disability20; futhermore, no studies have examined the contribution of lifetime mental disorder history to disability, although general population research has examined the economic effect of lifetime disorders.21,22

A more comprehensive description of disability in the CAF necessitates the use of a standard disability measure, although such measures have not been validated in the military context. The World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule (WHODAS-2)23 is a widely used and highly reliable self-report questionnaire that assesses disability during the past 30 days. Nevertheless, it remains unclear whether the WHODAS-2 represents a valid measure of disability in the CAF. A full description of disability in the CAF also requires an examination of sociodemographic and military variables that may represent subgroups of military personnel with varying levels of reported disability. Previous research has shown that sex, age, rank, service, and deployment status are associated with disability in military populations.24,25

This study was designed to address these limitations by conducting a comprehensive evaluation of the extent of mental disorder–related disability in a representative sample of CAF Regular Force members using the WHODAS-2,23 a validated measurement scale of disability. The primary objectives were to 1) describe the extent of disability in this population across several sociodemographic and military characteristics, 2) describe the relationship of any past-year (that is, recent) mental disorder on disability as well as each individual past-year mental disorder, 3) describe the effect of the number of recent disorders on disability severity to examine comorbidity effects, and 4) examine those with lifetime disorders in the absence of past-year disorders (that is, remote disorders) to assess the relative effect of the recency of disorders on disability. A secondary objective was to validate the WHODAS-2 as a measure of disability in this population.

Methods

Data Source

The data source was the Canadian Forces Mental Health Survey (CFMHS), a cross-sectional survey of mental health of CAF personnel, which was administered by Statistics Canada. Survey coverage included all CAF Regular Force personnel, as well as reservists who were deployed in support of the mission in Afghanistan. However, our analysis included only the Regular Force sample (N = about 6700; response rate = 79.8%), representative of the roughly 68 000 Regular Force personnel in the CAF in 2012. Statistics Canada personnel collected the data using a computer-assisted, face-to-face interview. Additional details on the CFMHS are described elsewhere.26

Measures

Disability

The main measure of disability was the 12-item version of the WHODAS-2.23 Although this scale has mainly been used in clinical samples with chronic physical conditions27,28 and mental disorders,29,30 it has also been validated in general civilian populations.23,31 Questions are preceded by “In the past 30 days, how much difficulty did you have in…” and rated on a scale from 1 (none) to 5 (extreme/cannot do). Items are grouped into six subscales of two items each, representing various domains of functioning: 1) understanding and communication (“concentrating on doing something for 10 minutes”), 2) self-care (“getting dressed”), 3) mobility (“standing for long periods, such as 30 minutes”), 4) interpersonal relationships (“dealing with people you do not know”), 5) work and household roles (“your day-to-day work”), and 6) community and civic roles (“joining in community activities [for example, festivities or religious or other activities] in the same way as anyone else can”). In the CFMHS, total WHODAS-2 scores were computed using the “complex” scoring method recommended in the WHODAS-2 manual,23 yielding scores from 0 (no disability) to 100 (full disability). In addition to these total scores, we created 4 severity categories following the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF)32 severity ranges (no disability, 0 to 4; mild disability, 5 to 24; moderate disability, 25 to 49; and severe/extreme disability, 50 to 100). Previous research among civilians reported good internal consistency for this measure.23,31

Mental Disorders

Mental disorders were assessed with the World Health Organization (WHO) World Mental Health Composite International Diagnostic Interview (WMH-CIDI).33 The WMH-CIDI is a lay-administered psychiatric interview for the assessment of mental disorders according to ICD-10 and DSM-IV criteria. In the CFMHS, the WMH-CIDI was used to measure the following mental disorders: posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), major depressive episode (MDE), generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), panic disorder (PD), alcohol abuse, and alcohol dependence. For our study, alcohol abuse and dependence were combined as “alcohol use disorder” (AUD). WMH-CIDI assessments determined whether individuals had ever met criteria for mental disorders in their lifetime (lifetime disorders) and whether these criteria had been met during the past 12 months (recent disorders). In addition, we identified those with a WMH-CIDI diagnosed lifetime disorder but no recent disorder (remote disorders).

Sociodemographic/Military Variables

Sex, age group (aged 17 to 24, 25 to 34, 35 to 44, and 45 to 60 years), rank (junior noncommissioned member [NCM], senior NCM, or officer), service (Army, Navy, or Air Force), and deployment status (“any deployment overseas” versus “no deployment”) were considered important subgroups for examining disability in the CAF.

Ethical Aspects

Ethical aspects of the research protocol were approved by the relevant entities within Statistics Canada. Participation was voluntary, and respondents provided written consent.

Statistical Analysis

Factor analytic approaches were used to explore the validity of the WHODAS-2 in the study population. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed to assess the overall fit of 1 strong disability factor (that is, all 12 items loading on a single factor). This 1-factor model was then compared with a model including 6 first-order factors representing each 2-item subscale of the WHODAS-2 as well as 1 higher-order “overall disability” factor, which has been supported by previous research.23,31 CFA models were fitted using weighted least-squares estimation for the analysis of ordinal data. Model fit was considered to be acceptable if recommended cutoffs were met for the comparative fit index (CFI > 0.95), Tucker-Lewis fit index (TLI > 0.95), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA ≤ 0.06).34

Mean disability scores were calculated and differences in these scores among sociodemographic/military factors and mental disorder categories were examined with t tests and 1-way analysis of variance, which are valid in large data sets even for non-normally distributed data.35 Proportions reporting each level of disability severity were calculated for sociodemographic/military and mental disorder subgroups. All analyses incorporated sampling weights provided by Statistics Canada that ensure representativeness of the sample and account for person nonresponse.36 Variance estimates (SDs for means and 95% confidence intervals for proportions) were calculated by taking into account the complex design of the survey, using bootstrapping or Taylor series linearization.

MPlus software37 (version 6; Muthén & Muthén, Los Angeles, CA) was used for CFA. All other analyses were performed using SAS 9.3 software (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

Results

Validation of the WHODAS-2

Internal consistency of the WHODAS-2 items was high (alpha = 0.89). Results from CFA indicated an acceptable overall fit of the 1-factor model (chi-square = 1047.50, CFI = 0.96, TLI = 0.95, RMSEA = 0.052). Similarly, the CFA for the higher-order model with 6 “domain” factors and 1 “general disability” factor suggested an acceptable and improved overall fit (chi-square = 697.71, CFI = 0.98, TLI > 0.98, RMSEA = 0.045). Together, these results point to 1 strong disability factor, mirroring findings of a civilian population study using the same version of the WHODAS-2.31

Disability Patterns

Mean disability scores and patterns of disability severity broken down by sample characteristics are presented in Table 1. The mean disability score of the whole sample was 7.6 (SD = 13.05, skew = 2.44, range = 0 to 94.4). Of the whole sample, 59% had no disability, whereas 30.8%, 8.4%, and 1.6% had mild, moderate, and severe disability, respectively. Female participants had significantly higher disability scores than male participants (t = 4.12, df = 6671, P < 0.0001). Disability scores were significantly higher with increasing age ranges (F = 56.3, df = 3/6671, P < .0001), although individuals aged 35 to 44 years did not differ from those aged 45 to 60 years (t = 0.53, df = 6671, P = 0.60). Rank had a significant effect on disability (F = 59.9, df = 2/6671, P < 0.0001), with senior NCMs reporting greater disability than junior NCMs (t = 4.10, df = 6671, P < 0.0001), who in turn reported greater disability than officers (t = 7.11, df = 6671, P < 0.0001). Army personnel reported greater disability than Air Force personnel (t = 2.79, df = 6671, P = 0.005). In addition, those who had been deployed overseas reported greater disability than those who had never been deployed (t = 6.01, df = 6676, P < 0.0001).

Table 1.

Mean disability score and prevalence of disability severity categories, by demographic and military characteristics.

| Group | Percentage of sample | Mean disability score (SD) | Disability severity category (95% confidence interval) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | Mild | Moderate | Severe | |||

| Whole sample | 7.6 (13.1) | 59.2 (58.0 to 60.5) | 30.8 (58.0 to 60.5) | 8.4 (7.6 to 9.1) | 1.6 (1.3 to 2.0) | |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 86.1 | 7.3 (12.4)* | 60.3 (59.0 to 60.6) | 30.4 (29.1 to 31.6) | 7.8 (7.0 to 8.5) | 1.6 (1.2 to 1.9) |

| Female | 13.9 | 9.3 (14.7)† | 52.7 (49.3 to 56.1) | 33.2 (30.0 to 36.5) | 12.1 (9.8 to 14.4) | 2.0 (0.9 to 3.0)a |

| Age, y | ||||||

| 17 to 24 | 13.3 | 4.4 (9.1)* | 71.5 (67.8 to 74.9) | 24.3 (20.8 to 27.7) | 4.0 (2.4 to 5.5)a | 0.5 (0.0 to 1.1)a |

| 25 to 34 | 37.6 | 6.4 (11.5)† | 62.6 (60.5 to 64.7) | 29.6 (27.6 to 31.7) | 6.9 (5.6 to 8.1) | 0.9 (0.5 to 1.3)a |

| 35 to 44 | 27.7 | 9.3 (15.3)‡ | 54.0 (51.7 to 56.2) | 33.0 (30.9 to 35.2) | 10.4 (9.0 to 11.8) | 2.6 (1.8 to 3.4) |

| 45 to 60 | 21.3 | 9.5 (14.1)‡ | 52.7 (50.1 to 55.1) | 33.9 (31.5 to 36.3) | 11.2 (9.6 to 12.8) | 2.3 (1.5 to 3.1)a |

| Rank | ||||||

| Junior NCM | 55.1 | 7.7 (12.6)* | 59.1 (57.3 to 61.0) | 30.5 (28.7 to 32.4) | 8.6 (7.5 to 9.7) | 1.7 (1.2 to 2.2) |

| Senior NCM | 24.1 | 9.2 (13.6)† | 52.9 (50.7 to 55.1) | 34.5 (32.4 to 36.5) | 10.5 (9.1 to 11.8) | 2.2 (1.5 to 2.9) |

| Officer | 20.9 | 5.5 (9.4)‡ | 66.7 (64.7 to 68.8) | 27.0 (25.1 to 29.1) | 5.4 (4.3 to 6.5) | 0.7 (0.4 to 1.1)a |

| Service | ||||||

| Army | 53.2 | 8.0 (13.0)* | 58.5 (56.8 to 60.2) | 30.51 (28.9 to 32.2) | 9.1 (8.1 to 10.1) | 1.9 (1.4 to 2.4) |

| Navy | 17.2 | 7.4 (12.4)*,† | 58.5 (55.5 to 61.4) | 32.0 (29.2 to 34.8) | 7.9 (6.3 to 9.5) | 1.6 (0.9 to 2.3)a |

| Air Force | 29.6 | 7.0 (11.9)† | 61.1 (58.9 to 63.2) | 30.5 (28.3 to 32.6) | 7.4 (6.2 to 8.6) | 1.1 (0.6 to 1.6)a |

| Deployment status | ||||||

| Deployed | 61.5 | 8.4 (13.2)* | 56.3 (54.7 to 57.7) | 32.3 (30.9 to 33.8) | 9.5 (8.6 to 10.3) | 2.0 (1.5 to 2.4) |

| Not deployed | 38.5 | 6.4 (11.5)† | 64.1 (61.9 to 66.2) | 28.2 (26.1 to 30.3) | 6.6 (5.4 to 7.8) | 1.1 (0.6 to 1.6)a |

Disability means not sharing a superscript symbol are significantly different at P < 0.05. NCM = noncommissioned member.

aBecause of a high level of variation, estimates may be unreliable.

Disability and Mental Disorders

As shown in Table 2, individuals with any recent disorder reported greater disability than those with no lifetime disorder (t = 25.5, df = 6454, P < 0.0001). However, individuals with any recent disorder had varying levels of disability, with 24.7% reporting no disability and 42.1%, 26.0%, and 7.4% reporting mild, moderate, and severe disability, respectively.

Table 2.

Mean disability score and prevalence of disability severity categories for each mental disorder, by recency of disorder.

| Group | Percentage of sample | Mean disability score (SD) | Disability severity category (95% confidence interval) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | Mild | Moderate | Severe | |||

| Any mental disorder | ||||||

| No lifetime | 51.6 | 4.3 (8.4)* | 71.6 (70.1 to 73.1) | 24.5 (23.0 to 26.0) | 3.5 (2.8 to 4.2) | 0.4 (0.2 to 0.6)a |

| Remote | 31.2 | 7.2 (11.5)† | 57.1 (54.7 to 59.4) | 35.0 (32.8 to 37.3) | 7.1 (5.9 to 8.3) | 0.8 (0.4 to 1.3)a |

| Recent | 16.5 | 18.8 (18.6)‡ | 24.7 (21.9 to 27.3) | 42.1 (39.0 to 45.3) | 26.0 (23.0 to 29.0) | 7.4 (5.6 to 9.0) |

| Posttraumatic stress disorder | ||||||

| No lifetime | 88.9 | 6.3 (11.0)* | 63.3 (62.0 to 64.6) | 29.4 (28.2 to 30.7) | 6.5 (5.8 to 7.2) | 0.8 (0.6 to 1.1)a |

| Remote | 5.8 | 10.5 (14.5)† | 43.2 (37.9 to 48.5) | 42.2 (37.1 to 47.5) | 12.4 (9.2 to 15.8) | 2.2 (0.4 to 3.8)a |

| Recent | 5.3 | 25.6 (21.7)‡ | 13.2 (9.4 to 16.4) | 38.9 (33.3 to 44.1) | 34.1 (28.8 to 40.0) | 13.8 (10.0 to 18.0) |

| Major depressive episode | ||||||

| No lifetime | 84.3 | 6.0 (10.7)* | 64.2 (62.9 to 65.4) | 29.1 (27.8 to 30.3) | 6.1 (5.4 to 6.8) | 0.7 (0.4 to 1.0)a |

| Remote | 7.7 | 9.1 (13.1)† | 50.4 (45.9 to 55.0) | 38.3 (33.6 to 42.9) | 9.7 (7.0 to 12.2) | 1.6 (0.4 to 3.0) |

| Recent | 8.0 | 23.3 (19.3)‡ | 16.0 (12.9 to 19.4) | 41.0 (36.3 to 45.7) | 31.3 (26.8 to 35.8) | 11.3 (8.6 to 14.5) |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | ||||||

| No lifetime | 87.9 | 6.2 (10.9)* | 63.6 (62.4 to 64.9) | 29.2 (28.0 to 30.4) | 6.2 (5.5 to 6.9) | 0.9 (0.6 to 1.2) |

| Remote | 7.4 | 12.7 (14.3)† | 36.0 (31.6 to 40.6) | 43.2 (38.5 to 48.2) | 18.6 (14.8 to 22.3) | 2.1 (0.7 to 3.4)a |

| Recent | 4.7 | 25.4 (21.7)‡ | 14.7 (10.3 to 18.5) | 38.0 (32.0 to 44.2) | 33.3 (27.1 to 38.8) | 14.7 (10.1 to 19.0) |

| Panic disorder | ||||||

| No lifetime | 94.2 | 6.7 (11.2)* | 61.6 (60.4 to 62.9) | 30.2 (29.0 to 31.4) | 7.2 (6.5 to 7.9) | 0.9 (0.7 to 1.2) |

| Remote | 2.4 | 14.5 (16.9)† | 35.1 (28.1 to 43.0) | 39.0 (31.3 to 46.5) | 23.4 (16.1 to 30.5) | 2.6 (0.0 to 4.5)a |

| Recent | 3.4 | 27.1 (24.1)‡ | 14.0 (9.2 to 18.7)a | 34.6 (28.4 to 41.6) | 29.9 (23.7 to 36.9) | 20.6 (14.5 to 27.1) |

| Alcohol use disorder | ||||||

| No lifetime | 68.1 | 6.5 (12.1)* | 65.6 (61.8 to 64.8) | 28.7 (27.3 to 30.1) | 6.8 (6.0 to 7.7) | 1.2 (0.8 to 1.5) |

| Remote | 27.4 | 9.5 (14.3)† | 52.3 (49.8 to 54.6) | 34.4 (32.2 to 36.7) | 11.0 (9.6 to 12.6) | 2.3 (1.5 to 3.0) |

| Recent | 4.5 | 13.5 (17.5)‡ | 39.6 (33.4 to 45.9) | 41.0 (34.3 to 47.1) | 14.6 (10.0 to 19.5) | 4.9 (2.2 to 7.6)a |

Disability means not sharing a superscript symbol are significantly different at P < 0.05. aBecause of a high level of variation, estimates may be unreliable.

An examination of individual disorders showed that the difference in disability between recent and no lifetime disability was a consistent finding across disorders. However, although recent PTSD, MDE, GAD, and PD were all similar in terms of the level of reported disability, AUD was by far the least disabling disorder, with 14.6% and 4.9% reporting moderate and severe disability, respectively. This is in contrast with other recent disorders, in which between 29.9% and 34.1% of individuals reported moderate disability and between 11.3% and 20.6% reported severe disability (Table 2).

Each increase in the number of recent disorders was associated with an increase in disability (F = 227.4, df = 3/6428, P < 0.0001). In addition, the disproportionate amount of disability became more pronounced with each increase in the number of disorders, with severe disability reported by 26% of those with 3 or more disorders, compared with 2% and 7.9% of those with 1 and 2 disorders, respectively (Table 3).

Table 3.

Mean disability score and prevalence of disability severity categories, by number of recent mental disorders.

| Group | Percentage of sample | Mean disability score (SD) | Disability severity category (95% confidence interval) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | Mild | Moderate | Severe | |||

| Number of recent mental disorders | ||||||

| 0 | 83.9 | 5.4 (10.0)* | 66.2 (64.8 to 67.5) | 28.4 (27.1 to 29.7) | 4.9 (4.3 to 5.5) | 0.6 (0.3 to 0.8)a |

| 1 | 9.8 | 13.6 (14.5)† | 33.1 (29.3 to 37.0) | 44.9 (41.1 to 48.8) | 20.0 (16.7 to 23.4) | 2.0 (0.8 to 3.0)a |

| 2 | 3.7 | 22.6 (18.1)‡ | 15.8 (10.9 to 21.0) | 38.6 (31.8 to 46.3) | 36.8 (30.1 to 44.1) | 7.9 (4.2 to 11.7)a |

| ≥3 | 2.5 | 33.1 (21.4)§ | 6.5 (2.0 to 9.7)a | 32.5 (24.0 to 40.1) | 35.1 (27.2 to 43.9) | 26.0 (18.9 to 34.1) |

Disability means not sharing a superscript symbol are significantly different at P < 0.05.

aBecause of a high level of variation, estimates may be unreliable.

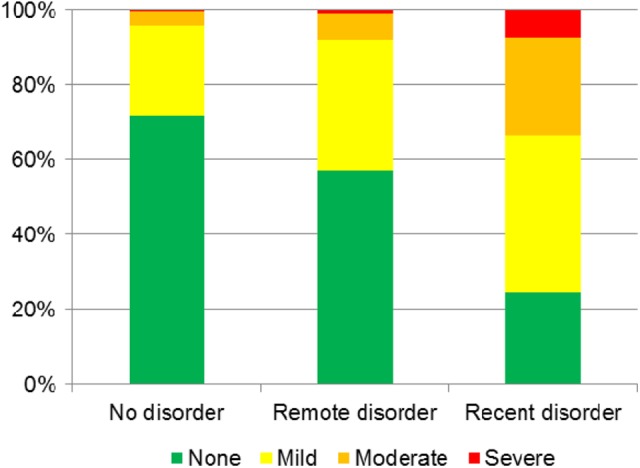

The recency of mental disorders was associated with disability severity (F = 349.9, df = 2/6454, P < 0.0001). Although individuals with remote disorders reported greater disability than those with no lifetime disorder (t = 10.0, df = 6454, P < 0.0001), they also reported significantly lower disability than those with recent disorders (t = 19.4, df = 6454, P < 0.0001) (Table 2). In fact, 57.1% of those with remote disorders reported no disability and only 7.1% and 0.8% reported moderate and severe disability, respectively—a pattern that was much closer to that of the group with no lifetime disability (Figure 1; Table 2).

Figure 1.

Extent of disability in those with and without any mental disorder.

Discussion

Key Findings

The main goal of this study was to provide a preliminary description of mental disorders and disability in the CAF. The results confirm that the WHODAS-2 is a valid measure of disability in this population. As expected, we saw greater disability in CAF members with recent mental disorders than those with no lifetime disorder, and disability increased with the number of recent mental disorders. Although individual disorders were generally similar in terms of proportions of disability categories, AUD was associated with lower disability compared with other disorders. Compared with recent disorders, remote disorders were associated with a much smaller increase in disability. Finally, consistent with previous research,24,31,38,39 the level of reported disability varied as a function of the following sociodemographic and military factors: sex, age, rank, service, and deployment status; this provides additional support for the validity of the measure.

Our findings are consistent with previous civilian31 and military15,20,40 research linking recent mental disorders to disability. In particular, we found similar prevalences of past-year MDE and PTSD with severe disability, as have been reported in the US military.12 More importantly, individuals with each of the recent mood and anxiety disorders assessed by the survey had relatively similar levels of disability. Recent AUD was associated with lower levels of disability relative to other mental disorders, although alcohol-related disorders have other important health effects of interest to the CAF as an employer and as a provider of health services. The finding of a dose-response effect of mental disorders is consistent with research highlighting the potentially negative effects of mental illness comorbidity on disability in civilians31 and military personnel.20

Those with remote disorders were little different from those with no lifetime disorders in terms of disability. This suggests that many of these individuals have almost fully recovered from their condition. Although there is some indirect evidence in civilian research to support this,22,41 it is largely a novel finding.

Strengths and Limitations

This study is an important first step in assessing the true effect of mental disorders on disability in the CAF. Its strengths include 1) the large, representative sample; 2) careful assessment of both past-year and lifetime mental disorders; and 3) the use of a widely used, well-validated disability measure. However, a number of important limitations should be noted. First, as mentioned, the WHODAS-2 was not designed for use in military populations and was designed to assess more severe disability than might be expected in these populations, which are composed largely of young, physically fit individuals.17 Indeed, the nature of the military workplace and of military fitness standards is such that some people with little or no reported disability may be judged to be unfit for service because fitness determinations take into account the ability to remain functioning if deployed to any environment with little or no medical support and/or to a combat zone. Along these lines, Herrell et al17 developed a military-specific disability measure that could be useful in future CAF research. Second, we did not assess criterion validity using some independent measure of disability (such as medical release, workplace performance, or absenteeism). Third, the CFMHS is a cross-sectional study and, despite evidence that disability is more likely to result from mental disorders than vice versa,42 temporality in this relationship cannot be established with these data. Fourth, our study represents only an initial examination of mental health and disability. Future studies will more comprehensively assess the role of mental health in disability in multivariate models that incorporate important confounders, especially chronic physical disorders, and that explore various modifiers of disability.

Implications

There are a number of important implications stemming from this study. First, the validation of the WHODAS-2 in the CAF will allow for its use in subsequent research as a means of identifying various degrees of disability in this population. Importantly, this short version of the WHODAS-2 may have greater clinical application than the full 36-item version recommended in DSM-5.43

Next, the strong association between recent mental disorders and disability may have important implications for the CAF in terms of the potential costs associated with disability, including impaired operational readiness, absenteeism, lower productivity, and increased turnover. This underscores the negative effect of mental disorders (particularly when comorbid) as well as the importance of identification and effective treatment of such disorders in the CAF. The finding that the mood and anxiety disorders assessed in the survey had relatively similar associations with disability suggests that priorities for disability mitigation for these disorders should be driven by the disorder’s prevalence, with MDE, PTSD, and GAD therefore being attractive targets. However, individuals with recent disorders nevertheless also showed a broad range of disability. About one-quarter had no disability, close to one-half had only minimal disability, and relatively few were severely disabled; this points to the need for individualized assessment and rehabilitation.

Finally, our results regarding individuals with remote disorders suggest that the majority of individuals with past disorders are likely recovering enough to not require accommodation for their current duties, which speaks to the capacity for recovery from mental disorders and suggests that remote mental disorders result in little disability. Overall, our results suggest that efforts to reduce disability in the CAF should indeed be focused on current, rather than past, mental disorders.

Conclusion

This study is an important first step in characterizing the effects of mental disorders on disability in the CAF. We found that recent mental disorders are strongly associated with disability in this population, whereas past disorders are far less so, suggesting that many individuals are mostly recovering from their disorder. However, future research is needed to understand the role of physical disorders and to explore CAF occupational impairments in those who have recovered from mental disorders.

Acknowledgements

A version of this paper was presented at the Military and Veteran Health Research Forum; 2015 Nov 23-25; Quebec City (QC).

Footnotes

Authors’ Note: The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not represent the official policy of the Department of National Defence, the Canadian Armed Forces, or the Government of Canada.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Salary support for this work was provided by the Department of National Defence (Canada).

References

- 1. Lenssinck ML, Burdorf A, Boonen A, et al. Consequences of inflammatory arthritis for workplace productivity loss and sick leave: a systematic review. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72(4):493–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. The Conference Board of Canada. Mental health issues in the labour force: reducing the economic impact on Canada. Ottawa (ON: ): Conference Board of Canada; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sareen J, Cox BJ, Afifi TO, et al. Combat and peacekeeping operations in relation to prevalence of mental disorders and perceived need for mental health care: findings from a large representative sample of military personnel. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(7):843–852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Boulos D, Zamorski MA. Do shorter delays to care and mental health system renewal translate into better occupational outcome after mental disorder diagnosis in a cohort of Canadian military personnel who returned from an Afghanistan deployment?. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e008591 doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Smith TC, Ryan MA, Wingard DL, et al. New onset and persistent symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder self reported after deployment and combat exposures: prospective population based US military cohort study. BMJ. 2008;336(7640):366–371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Erickson J, Kinley DJ, Bolton JM, et al. A sex-specific comparison of major depressive disorder symptomatology in the canadian forces and the general population. Can J Psychiatry. 2014;59(7):393–398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hodson SE, McFarlane AC, Van Hoof M, et al. Mental health in the Australian Defence Force—2010 ADF Mental Health Prevalence and Wellbeing Study: executive report. Canberra (AU: ): Department of Defence; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Goodwin L, Wessely S, Hotopf M, et al. Are common mental disorders more prevalent in the UK serving military compared to the general working population? Psychol Med. 2015;45(9):1881–1891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rosellini AJ, Heeringa SG, Stein MB, et al. Lifetime prevalence of DSM-IV mental disorders among new soldiers in the U.S. Army: results from the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS). Depress Anxiety. 2015;32(1):13–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Boulos D, Zamorski MA. Military occupational outcomes in Canadian Armed Forces personnel with and without deployment-related mental disorders. Can J Psychiatry. Forthcoming 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hoge CW, Auchterlonie JL, Milliken CS. Mental health problems, use of mental health services, and attrition from military service after returning from deployment to Iraq or Afghanistan. JAMA. 2006;295(9):1023–1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Thomas JL, Wilk JE, Riviere LA, et al. Prevalence of mental health problems and functional impairment among active component and National Guard soldiers 3 and 12 months following combat in Iraq. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(6):614–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Packnett ER, Gubata ME, Cowan DN, et al. Temporal trends in the epidemiology of disabilities related to posttraumatic stress disorder in the U.S. Army and Marine Corps from 2005-2010. J Trauma Stress. 2012;25(5):485–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kessler RC, Heeringa SG, Stein MB, et al. Thirty-day prevalence of DSM-IV mental disorders among nondeployed soldiers in the US Army: results from the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS). JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(5):504–513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Stevelink SA, Malcolm EM, Mason C, et al. The prevalence of mental health disorders in (ex-)military personnel with a physical impairment: a systematic review. Occup Environ Med. 2015;72(4):243–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Clarke PM, Gregory R, Salomon JA. Long-term disability associated with war-related experience among Vietnam veterans: retrospective cohort study. Med Care. 2015;53(5):401–408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Herrell RK, Edens EN, Riviere LA, et al. Assessing functional impairment in a working military population: the Walter Reed functional impairment scale. Psychol Serv. 2014;11(3):254–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gould M, Adler A, Zamorski M, et al. Do stigma and other perceived barriers to mental health care differ across Armed Forces? J R Soc Med. 2010;103(4):148–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Garber BG, Zamorski MA, Jetly R. Mental health of Canadian Forces personnel while on deployment to Afghanistan. Can J Psychiatry. 2012;57(12):736–744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Armour C, Contractor A, Elhai JD, et al. Identifying latent profiles of posttraumatic stress and major depression symptoms in Canadian veterans: exploring differences across profiles in health related functioning. Psychiatry Res. 2015;228(1):1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sareen J, Afifi TO, McMillan KA, et al. Relationship between household income and mental disorders: findings from a population-based longitudinal study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(4):419–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kessler RC, Heeringa S, Lakoma MD, et al. Individual and societal effects of mental disorders on earnings in the United States: results from the national comorbidity survey replication. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(6):703–711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ustun TB, Chatterji S, Kostanjsek N, et al. Developing the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0. Bull World Health Organ. 2010;88(11):815–823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Thompson JM, Pranger T, Sweet J, et al. Disability correlates in Canadian Armed Forces Regular Force veterans. Disabil Rehabil. 2015;37(10):884–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bell NS, Schwartz CE, Harford TC, et al. Temporal changes in the nature of disability: U.S. Army soldiers discharged with disability, 1981-2005. Disabil Health J. 2008;1(3):163–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zamorski M, Bennett RE, Boulos D, et al. The 2013 Canadian Forces Mental Health Survey: background and methods Can J Psychiatry. 2016;61 Suppl 1:10S–25S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Garin O, Ayuso-Mateos JL, Almansa J, et al. Validation of the “World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule, WHODAS-2” in patients with chronic diseases. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2010;8:51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Magistrale G, Pisani V, Argento O, et al. Validation of the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule II (WHODAS-II) in patients with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2015;21(4):448–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Galindo-Garre F, Hidalgo MD, Guilera G, et al. Modeling the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule II using non-parametric item response models. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2015;24(1):1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Guilera G, Gomez-Benito J, Pino O, et al. Disability in bipolar I disorder: the 36-item World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0. J Affect Disord. 2015;174:353–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Andrews G, Kemp A, Sunderland M, et al. Normative data for the 12 item WHO Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0. PLoS One. 2009;4(12):e8343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. World Health Organization. International classification of functioning, disability and health. Geneva (CH): World Health Organization; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kessler RC, Ustun TB. The World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative Version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI). Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13(2):93–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hu L, Bentler P. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Modeling. 1999;6(1):1–55. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lumley T, Diehr P, Emerson S, et al. The importance of the normality assumption in large public health data sets. Annu Rev Public Health. 2002;23:151–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Statistics Canada. Candian Forces Mental Health Survey (CFMHS). 2014 May 11 [cited 2015 Jul 24]. Available from http://www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb/p2SV.pl?Function=getSurvey&SDDS=5084.

- 37. Muthén LK, Muthén BO. MPlus user’s guide. 6th ed Los Angeles (CA; ): Muthén and Muthén; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bell NS, Schwartz CE, Harford T, et al. The changing profile of disability in the U.S. Army: 1981-2005. Disabil Health J. 2008;1(1):14–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Merrill SS, Seeman TE, Kasl SV, et al. Gender differences in the comparison of self-reported disability and performance measures. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1997;52(1):M19–M26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Erickson J, Kinley DJ, Afifi TO, et al. Epidemiology of generalized anxiety disorder in Canadian military personnel. J Mil Veteran Fam Health. 2015;1(1):25–36. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Monson E, Brunet A, Caron J. Domains of quality of life and social support across the trauma spectrum. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2015;50(8):1243–1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Schweininger S, Forbes D, Creamer M, et al. The temporal relationship between mental health and disability after injury. Depress Anxiety. 2015;32(1):64–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Gold LH. DSM-5 and the assessment of functioning: the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0 (WHODAS 2.0). J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2014;42(2):173–181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]