Abstract

Background

Reducing access to lethal means (especially firearms) might prevent suicide, but counseling of at-risk individuals about this strategy may not be routine. Among emergency department (ED) patients with suicidal ideation or attempts (SI/SA), we sought to describe home firearm access and examine ED provider assessment of access to lethal means.

Methods

This secondary analysis used data from the Emergency Department Safety Assessment and Follow-up Evaluation, a 3-phase, 8-center study of adult ED patients with SI/SA (2010-2013). Research staff surveyed participants about suicide-related factors (including home firearms) and later reviewed the ED chart (including documented assessment of lethal means access).

Results

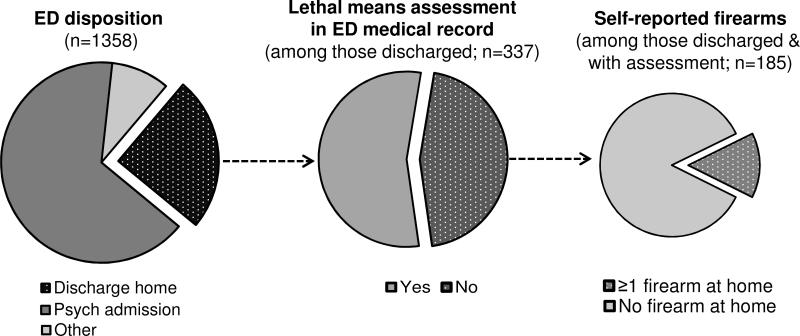

Among 1358 patients with SI/SA, 11% (95%CI 10-13%) reported ≥1 firearm at home; rates varied across sites (range: 6% to 26%) but not over time. On chart review, 50% (95%CI 47-52%) of patients had documentation of lethal means access assessment. Frequency of documented assessment increased over study phases (40% to 60%, p<0.001) but was not associated with state firearm ownership rates. Among the 337 (25%, 95%CI 23-27%) patients discharged to home, 55% (95%CI 49-60%) had no documentation of lethal means assessment; of these, 13% (95%CI 8-19; n=24) actually had ≥1 firearm at home. Among all those reporting ≥1 home firearm to study staff, only half (50%, 95%CI 42-59) had provider documentation of assessment of lethal means access.

Conclusions

Among these ED patients with SI/SA, many did not have documented assessment of home access to lethal means, including patients who were discharged home and had ≥1 firearm at home.

Keywords: Suicide/Self Harm, treatment, Assessment/Diagnosis, Clinical Trials, Depression, Epidemiology

INTRODUCTION

Among suicide prevention interventions, reducing access to highly lethal means of suicide (such as firearms, toxic medications, and other hazards; “lethal means restriction”) has a strong evidence base[1] and is now considered a key component of effective strategies to reduce suicide death rates.[2] Reducing access to firearms (e.g., through locked storage at home or through storage out of the home) is particularly important, since firearm suicide attempts have a high case-fatality rate and firearms account for 51% of all suicide deaths in the United States.[3]

Emergency departments (EDs) are a key setting for suicide prevention, as up to 8% of all ED patients have active or recent suicidal ideation (SI),[4-6] multiple ED visits appear to be a risk factor for suicide,[7] and many suicide victims are seen in an ED shortly before death. [8] Based on models using national suicide statistics, ED-based interventions might help decrease suicide deaths by 20% annually.[9] This includes counseling of patients and family members about lethal means restriction (“lethal means counseling”) by ED providers, which may improve firearm storage behavior[10] and is recommended by several national organizations.[2, 11, 12]

Despite the evidentiary base and widespread authoritative endorsement for lethal means restriction, prior work suggests ED providers are skeptical about its effectiveness as a suicide prevention strategy and, per their self-report, do not routinely ask or counsel suicidal patients about access to lethal means.[13-15] To our knowledge, only one prior study attempted to assess the frequency with which lethal means counseling occurs and is documented in EDs. In that chart review of 298 pediatric (age <18 years) ED patients with behavioral or psychiatric complaints, only 4% had documented assessment of lethal means access, even though 37% of those deemed high risk by a social worker were also identified as having access to lethal means.[16] Similar work in an adult population has not been reported.

The current investigation addresses this knowledge gap by examining lethal means access and assessment in a large cohort of adult ED patients with suicidal ideation or attempts (SI/SA). Our objectives were to use a multi-site, multi-phase cohort of ED patients with SI/SA to: (1) describe patient-reported access to firearms at home; and examine the (2) frequency and (3) predictors of medical record documentation of access to lethal means.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The Emergency Department Safety Assessment and Follow-up Evaluation (ED-SAFE) was a quasi-experimental, 8-center study conducted from August 2, 2010 through November 8, 2013.[17] Designed to test universal screening for suicide risk and post-ED visit telephone counseling, the study had three phases: treatment as usual, universal screening, and intervention (with continued universal screening). In the intervention phase, ED providers were trained on use of a secondary risk assessment tool and a patient safety planning template, which included lethal means access as one component. However, no phase included dedicated provider training on lethal means assessment.

Sample

The 8 participating EDs were located in 7 states distributed across all four US census regions. At each site, research staff prospectively screened ED charts and approached potentially eligible patients for additional screening. Eligible patients were adults (age ≥18 years) with: SI (thoughts of killing oneself) or an SA (actual, aborted, or interrupted) in the past week, including the current visit; ability to consent and participate (alert, fully oriented, not intoxicated, able to paraphrase the study requirements, no hostile behavior or psychosis, no severe pain or persistent vomiting); willingness and ability to complete telephone follow-up at specified intervals for one year; current stable, permanent residence in the community (not in a facility, shelter, or nursing home, and not in state custody or with pending legal action); and without an insurmountable language barrier. Participants provided written informed consent after receiving a complete description of the study, and the institutional review boards at each site approved all study procedures and protocols. The National Institute of Mental Health Data and Safety Monitoring Board conducted overall study oversight and monitoring.

Study procedures and measures

At the time of enrollment, research staff administered a questionnaire to participants in a private area within the ED. These responses were not shared with the treating ED providers. After enrollment, staff reviewed the electronic medical record for the patient's ED visit using a standardized abstraction form; this abstraction included notes from physicians, nurses, mental health consultants, and other providers involved in the visit. In the current analysis, we examine linked data from the baseline questionnaire (patient self-report) and the baseline ED visit (medical record review) from all three study phases combined.

Self-reported measures

Sociodemographic variables included age, sex, race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, marital and cohabitation status, education, employment, and current or prior military service. Psychiatric variables included prior diagnoses of mood disorders (including depression, bipolar disorder or anxiety), substance or alcohol abuse, schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, or any other psychiatric condition. Participants were also asked about alcohol and drug use, use of medications for mental health problems, prior psychiatric hospitalizations, and recent interpersonal violence. Questions about suicidal thoughts and behaviors assessed content, frequency and severity, as well as specific suicide methods either considered or used. Concerning firearm access, participants were asked “Are any firearms currently kept in or around your home?” Those who said yes were asked about firearm ownership, storage, and ease of access.

Medical record measures

Variables abstracted from the ED medical record included documentation of: SI or SA (including timing); alcohol abuse; acute alcohol intoxication (based on site hospital's lab definition); intentional illegal or prescription drug abuse; interpersonal violence; and domestic violence. Staff also recorded data related to the ED visit, including whether the visit was for a psychiatric issue, whether the patient was evaluated by a mental health provider during the ED stay, and the ED disposition. Staff recorded whether there was documentation in the chart (by any ED provider) of assessment of “means to complete suicide (e.g., firearms or presence of medications).” Although there was not specification of type of means, so we could not separate assessment of access to firearms from medications or other hazards, we assumed that this chart abstraction variable included all mentions of firearms. For patients discharged home, staff recorded whether there was documentation of a personalized safety plan, including who made it.

Outcomes

Our primary outcomes were (1) whether the patient reported having ≥1 firearm at home and (2) whether there was documentation in the ED medical record that a provider assessed access to lethal means.

Analysis

We used descriptive statistics to examine self-reported patient variables associated with having ≥1 firearm at home and to examine medical record variables associated with documented assessment of lethal means access. For both descriptive analyses, we tested for statistically significant (p<0.05) differences among groups using Chi-square tests for categorical variables and Wilcoxon rank-sum for the continuous variable of age. Finally, we used unadjusted and multivariable logistic regression to identify factors (from the medical record) associated with documented assessment of lethal means access, after adjustment for study phase and site The adjusted model was built with variables significant at p<0.25 in unadjusted analysis, followed by sequential backwards elimination of the least significant variables. The final model included only variables significant at p<0.05 in the adjusted model. . Analyses were performed using SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina).

RESULTS

The ED-SAFE cohort included 1,376 participants. For this analysis, we excluded those with missing responses to questions about firearms (n=17) or about lethal means assessment (n=1), leaving 1,358 participants. The median participant age was 36 years (interquartile range: 25-47), and 56% were women.

Overall, 11% (95%CI 10-13) of these suicidal ED patients reported having ≥1 firearm in the home (Table 1). Rates varied significantly across the geographically diverse study sites (p<0.001) but not over the three study phases. Rates ranged from a high in the southern site (26% of participants reported having ≥1 firearm at home), to sites in the midwest (10% and 13%) and west (9% and 13%), to lows in the northeastern sites (6%, 6% and 7%).

Table 1.

Self-Reported Participant Characteristics, by Patient-Reported Presence of ≥1 Firearm at Home (n=1,358)

| Total | No firearm at home (n=1,205) | ≥ 1 firearm at home (n=153) | p | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | n | % | n | % | n | ||

| Demographics | |||||||

| Age in years | Median: 36 | IQR: 25-47 | Median: 36 | IQR: 25-46 | Median: 37 | IQR: 26-47 | 0.48a |

| Gender | |||||||

| Male | 44 | 597 | 43 | 520 | 50 | 77 | 0.09 |

| Female | 56 | 761 | 57 | 685 | 50 | 76 | |

| Race | |||||||

| White | 75 | 1016 | 74 | 884 | 86 | 132 | 0.003 |

| Black/African American | 17 | 224 | 18 | 210 | 9.2 | 14 | |

| Other | 8.5 | 115 | 9.0 | 108 | 4.6 | 7 | |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 12 | 168 | 13 | 155 | 8.5 | 13 | 0.12 |

| Education; High school graduate or lower | 49 | 668 | 49 | 592 | 50 | 76 | 0.90 |

| Gay/lesbian/bisexual | 13 | 171 | 14 | 160 | 7.4 | 11 | 0.03 |

| Employment | |||||||

| Employed | 31 | 407 | 31 | 361 | 31 | 46 | 0.98 |

| Unemployed | 53 | 701 | 53 | 623 | 52 | 78 | |

| Physically/mentally disabled | 17 | 223 | 17 | 197 | 17 | 26 | |

| Current marital status | |||||||

| Never married | 51 | 689 | 52 | 626 | 41 | 63 | 0.02 |

| Married | 19 | 257 | 18 | 214 | 28 | 43 | |

| Widowed | 2.7 | 37 | 2.7 | 33 | 2.6 | 4 | |

| Divorced | 21 | 282 | 21 | 248 | 22 | 34 | |

| Other | 6.9 | 93 | 7.0 | 84 | 5.9 | 9 | |

| Live alone | 26 | 357 | 28 | 333 | 16 | 129 | 0.002 |

| Lifetime military service (including National Guard/reserves) | 6.1 | 83 | 6.1 | 73 | 6.6 | 10 | 0.80 |

| Alcohol misuse above threshold set by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism | 34 | 463 | 35 | 417 | 30 | 46 | 0.28 |

| Have used drugs other than those required for medical reasons (past 12 months) | 48 | 656 | 48 | 581 | 49 | 75 | 0.85 |

| Psychiatric history | |||||||

| Mood disorder diagnosis | 87 | 1183 | 87 | 1051 | 86 | 132 | 0.74 |

| Drug/alcohol abuse disorder diagnosis | 29 | 390 | 29 | 349 | 27 | 41 | 0.58 |

| Schizophrenia/schizoaffective disorder diagnosis | 11 | 147 | 12 | 138 | 6.0 | 9 | 0.04 |

| Any psychiatric diagnosis | 90 | 1218 | 90 | 1083 | 88 | 135 | 0.53 |

| Currently taking medications for emotional or psychological problem | 60 | 811 | 60 | 716 | 62 | 95 | 0.59 |

| Ever hospitalized for an emotional or psychological problem | 63 | 848 | 63 | 760 | 58 | 88 | 0.17 |

| Physically harmed by someone in past 30 days | 11 | 152 | 12 | 139 | 8.5 | 13 | 0.26 |

| Suicidal thoughts (past week) | |||||||

| Wished were dead or wouldn't wake up | 99 | 1341 | 99 | 1191 | 98 | 150 | 0.43 F |

| Had thoughts of killing self | 99 | 1350 | 99 | 1197 | 100 | 153 | 0.61 F |

| Considered method of killing self (n=1345) | 85 | 1138 | 84 | 1004 | 88 | 134 | 0.28 |

| Method thought of most often (n=1137) | |||||||

| Medication | 47 | 536 | 48 | 481 | 41 | 55 | <.0001 |

| Hanging | 5.7 | 65 | 5.7 | 57 | 6.0 | 8 | |

| Jumping | 5.4 | 61 | 5.3 | 53 | 6.0 | 8 | |

| Firearm | 7.8 | 89 | 6.0 | 60 | 22 | 29 | |

| Cutting | 13 | 150 | 14 | 138 | 9.0 | 12 | |

| Other | 21 | 236 | 21 | 215 | 16 | 21 | |

| Had intent to act on thoughts (n=1344) | 70 | 938 | 70 | 836 | 67 | 102 | 0.44 |

| Developed plan (n=1345) | 54 | 723 | 53 | 634 | 58 | 89 | 0.24 |

| Had intent to follow plan (n=718) | 85 | 607 | 85 | 537 | 79 | 70 | 0.10 |

| Suicide attempts | |||||||

| ≥1 lifetime attempt | 72 | 975 | 73 | 875 | 65 | 100 | 0.06 |

| Current visit due to suicide attempt (n=455) | 77 | 352 | 78 | 314 | 73 | 38 | 0.20 |

| Method of most serious attempt (n=975) | |||||||

| Medication | 55 | 535 | 56 | 489 | 46 | 46 | <.0001 |

| Hanging | 6.5 | 63 | 6.3 | 55 | 8.0 | 8 | |

| Jumping | 2.7 | 26 | 2.6 | 23 | 3.0 | 3 | |

| Firearm | 3.6 | 35 | 2.5 | 22 | 13 | 13 | |

| Cutting | 14 | 132 | 14 | 118 | 14 | 14 | |

| Other/multiple | 19 | 183 | 19 | 167 | 16 | 16 | |

Indicates Wilcoxon test

In unadjusted analysis, suicidal ED patients who reported having ≥1 firearm at home were significantly more likely to be white, heterosexual, married or live with someone (Table 1). Those with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder were less likely to have a firearm at home, but no other mental health diagnosis—nor prior psychiatric hospitalization—was associated with home firearm access. Those with and without ≥1 firearm at home had similar rates of reporting considering a method of suicide, developing a plan, and having intent to act on thoughts or plans. When asked what method they considered most often and what method they had used in their most serious past attempt (if applicable), approximately half of those both with and without firearms at home reported medication overdose. However, more of those with a firearm at home (versus those without one) reported considering a firearm most often as a suicide method (22% [95%CI 15-30] versus 6% [95%CI 5-8%], respectively) or using a firearm in a prior attempt: (13% [95%CI 7-21%] versus 3% [95%CI 2-4%]).

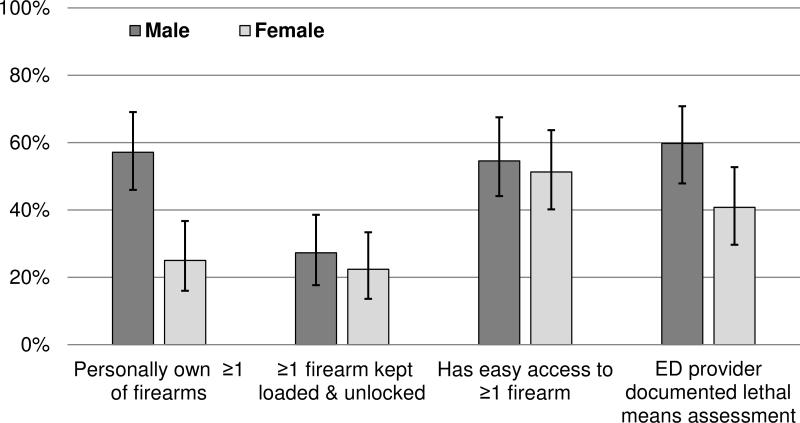

When asked about having ≥1 firearm at home, there was no significant gender difference (13% of men versus 10% of women; Table 1). However, among those with a firearm at home, men were more likely to personally own ≥1 of the firearms (58 %, 95%CI 46-69%, vs 25%, 95%CI 15-37%; Figure 1). In this cohort of participants with SI/SA, 25% (95%CI 18-32%) reported keeping ≥1 firearm loaded and unlocked and 54 % (95%CI 46-62%) said they had easy access to ≥1 firearm, without significant differences by gender.

Figure 1. Firearm Access Among Suicidal Emergency Department Patients Reporting ≥1 Firearm at Home (n=153).

Bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

Almost all (91%, 95%CI 89-93%) of these patients with SI/SA had presented to the ED with some kind of psychiatric issue, and 13% (95%CI 11-15%) were intoxicated (Table 2). Most (88%, 95%CI 86-90%) were evaluated by a mental health professional during the ED visit, and 66% (95%CI 63-68%) were admitted to a psychiatric facility. Of those discharged home (25%, 95%CI 23-27%), only 37% (95%CI 32-42%) had documentation that a safety plan was created.

Table 2.

Medical Record Characteristics of Participants, by Whether Assessment of Access to Lethal Means (Including but not Limited to Firearms) was Documented in the Medical Record for that Visit (n=1,358)

| No lethal means assessment (n=684) | Lethal means assessment (n=674) | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | n | % | n | ||

| Demographics | |||||

| Median age in years (25%-75%) | Median: 37 | IQR: 25-47 | Median: 35 | IQR: 25-46 | 0.34 |

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 42 | 287 | 46 | 310 | 0.13 |

| Female | 58 | 397 | 54 | 364 | |

| Race | |||||

| White | 75 | 511 | 75 | 505 | 0.97 |

| Black/African American | 17 | 114 | 16 | 110 | |

| Other | 8.6 | 59 | 8.4 | 56 | |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 14 | 92 | 11 | 76 | 0.22 |

| Psychiatric history | |||||

| Documented suicidal ideation | 99 | 675 | 100 | 673 | 0.22 |

| Documented history of suicide attempt | |||||

| Yes, past week | 30 | 204 | 27 | 181 | |

| Yes > 1 week ago | 20 | 137 | 25 | 171 | |

| Yes, no time specified | 9.4 | 64 | 11 | 74 | |

| No | 24 | 163 | 28 | 185 | |

| Missing | 17 | 116 | 9.4 | 63 | 0.0001 |

| Documented alcohol abuse | 23 | 159 | 26 | 172 | 0.33 |

| Intoxicated (based on blood alcohol level) | 15 | 103 | 11 | 75 | 0.03 |

| Documented intentional illegal or prescription drug misuse | 34 | 234 | 39 | 261 | 0.08 |

| ED visit characteristics | |||||

| Chief complaint involves psychiatric issue | 87 | 595 | 95 | 642 | <.0001 |

| Documented interpersonal violence | |||||

| Yes (any time frame) | 10 | 70 | 24 | 160 | <.0001 |

| No | 23 | 155 | 32 | 216 | |

| Missing | 67 | 459 | 44 | 298 | |

| Documented domestic violence | |||||

| Yes (any time frame) | 6.4 | 44 | 12 | 80 | <.0001 |

| No | 66 | 448 | 55 | 373 | |

| Missing | 28 | 192 | 33 | 221 | |

| Evaluated by a mental health professional during visit | |||||

| Yes | 80 | 546 | 96 | 647 | <.0001 |

| No | 11 | 75 | 2.2 | 15 | |

| Missing | 9.2 | 63 | 1.8 | 12 | |

| ED visit disposition | |||||

| Admitted/transferred to psychiatric/mental health facility | 60 | 408 | 72 | 485 | <.0001 |

| Discharged home | 27 | 185 | 23 | 152 | |

| Other | 13 | 91 | 5.5 | 37 | |

| If discharged home, documented creation of safety plan (n=337) | 35 | 65 | 40 | 60 | 0.41 |

Overall, 50% (95%CI 47-52%) of suicidal ED patients had medical record documentation of lethal means access assessment (Table 2). The frequency of such questioning appeared to increase with time, as the proportion of patients with documented assessment grew steadily from the first study phase (40%, 95%CI 36-45%), to the second (47%, 95%CI 42-52%), to the third (60%, 55-64%; p<0.001). This trend persisted even after adjustment for the variability in rates of assessment among sites (ranging from 18% [95%CI 12%-26%] up to 75% [95% CI 68-81%]). Site-specific rates of assessment were not correlated with prevalence of home firearms (either as reported by participants or based on national estimates).

In unadjusted comparisons, patients were more likely to have documented assessment of lethal means access if they had a psychiatric chief complaint, were not intoxicated, were evaluated by a mental health professional, or were admitted to a psychiatric facility. Documented interpersonal or domestic violence also appeared associated with a greater likelihood of assessment for lethal means for suicide, although a high proportion of charts were missing documentation about interpersonal violence or domestic violence.

In multivariable logistic regression adjusted for site and study phase (Online Table), factors associated with a decreased likelihood of documented lethal means assessment included intoxication (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] 0.42, 95%CI 0.27-0.67), evaluation by ED providers only (not a mental health professional; AOR 0.08, 95%CI 0.04-0.16), and missing documentation about interpersonal violence (AOR 0.18, 95%CI 0.12-0.28). A psychiatric chief complaint was associated with a higher likelihood of lethal means assessment (AOR 1.81, 95%CI 1.04-3.15). An ED visit disposition other than psychiatric hospitalization was associated with a lower likelihood of lethal means assessment in unadjusted analysis only (Online Table).

Figure 2 displays the overlapping populations of patients with documented lethal means access assessment, discharge home, and self-report of ≥1 firearm at home. Of note, 55% (95%CI 49-60) of those discharged home did not have documentation about whether a provider asked about access to lethal methods; of these, 13% (95%CI 8-19; n=24) had ≥1 firearm at home. Also of note, of those reporting ≥1 firearm at home, only half (50%, 95%CI 42-59) had documented questioning about lethal means access; among those reporting ≥1 firearm at home who were also discharged home (23%, 95%CI 16-30%), the proportion with documented assessment dropped to 31% (95%CI 17-49%).

Figure 2. ED Visit Disposition, Documented Assessment of Access to Lethal Means (Including Firearms), and Self-Reported Access to Firearms.

Dotted areas represent patient populations of higher concern (discharged home; without documented assessment of access to lethal means; and with ≥1 firearm at home).

DISCUSSION

In this study—the first objective examination of both self-reported firearm access and documented lethal means assessment—11% of ED patients with SI/SA reported having ≥1 firearm at home, and only half of patients had documented questioning about access to lethal means (including though not limited to firearms). This rate of assessment falls far short of national guidelines recommending that all suicidal patients receive counseling about reducing access to firearms and other lethal means.[11] There was an interesting relationship between documented lethal means assessment and ED visit disposition, in that assessment appeared more common in those admitted to a psychiatric facility (suggesting it is associated with overall assessment of risk severity) as compared to those discharged home (who, though at lower risk of suicide, might have unmonitored access sooner to lethal means and thus should also be questioned). Having an evaluation by a mental health provider, rather than just an ED provider, was associated with assessment of lethal means, yet even mental health specialists did not always document such questioning. Additional interesting findings related to geographic location and patient gender also have implications for future training and program implementation.

Lethal means assessment is important for both overall risk assessment and for safety planning for patients being discharged. Reducing access to potentially toxic medications can be a challenge, given that many of the medications used to treat mental illness can be toxic in an overdose. In our sample, 60% of patients reported currently taking at least one medication for an emotional or psychological problem, and medication overdose was the most suicide method most commonly reported as having been considered. Access to other lethal means of suicide–such as sharp objects or supplies for hanging–can also be difficult to control given their widespread availability for other purposes. But patients with firearm access at home might be considered at particularly high risk for discharge home, given that firearm access is a risk factor for suicide, [2, 3, 18] the actual act of a suicide attempt often occurs within only minutes of the decision to attempt, [19] and approximately 90% of firearm suicide attempts are fatal (compared to as few as 2% of medication overdoses). [20] Thus the finding that those admitted to a psychiatric facility appeared more likely to have a documented assessment about lethal means makes sense, as this assessment may have contributed to the decision for admission. However, while access to firearms and other lethal means in a patient with SI/SA by itself does not mandate psychiatric admission, it is a key component of home safety planning that should be addressed with all patients with SI/SA being discharged;[11] in our study, 25% of patients with SI/SA were discharged home. Safe storage of firearms and potentially toxic medications (i.e., inaccessible by the person with SI/SA) has been associated with less risk for suicide among adults and youth,[21, 22] and lethal means counseling in EDs might affect storage behavior.[10] Thus our finding that 55% of ED patients with SI/SA discharged home did not documented assessment of home access to lethal means should raise concern.

The suboptimal rates of lethal means assessment may stem from issues related to providers (e.g., inadequate training or unclear delineation of responsibilities)[13, 14, 23-25] and the ED environment (e.g., busy and crowded).[26] In our study, patients seen only by an ED physician, without an evaluation by a mental health consultant, were less likely to have documented lethal means assessment. This may relate to differences in training or awareness about lethal means counseling among ED and mental health providers, but it may also stem from overall perceived level of risk. That is, ED providers are more likely to request a consultation with a mental health provider for patients with the highest perceived level of risk,[11] and they may also be more likely to consider lethal means access in patients about whom they are the most worried. However, our findings comparing self-reported and medical record documentation about home firearm access suggests providers did not accurately suspect who did or did not have firearm access, again supporting the message that all ED patients with SI/SA should receive lethal means assessment and counseling.[11]

Our study identified some differences across the geographically-diverse sites; although not designed to examine geographic issues in detail, it does highlight areas for future research. A large body of work has demonstrated that firearm access increases suicide risk,[18, 27-29] and firearm ownership rates vary by state, from approximately 5% to 62%.[30, 31] In our study, across sites, reported rates of firearms at home were approximately half of those from estimates of the general population in the same state in 2004.[31] This discrepancy may stem from truly lower ownership rates among those with elevated suicide risk, from temporal changes, or differences between this ED population and the general population. It may also reflect under-reporting by participants, who may have worried that disclosure would lead to hospitalization or firearm confiscation. Discomfort with the politically-sensitive topic of firearm ownership may be an issue for both patients and providers, although prior work suggests patients are open to respectful, nonjudgmental discussions.[32, 33] Community norms can influence firearm ownership, in that people may be more likely to purchase firearms if they are part of a “social gun culture” (i.e., a culture with social activities related to firearms).[31] The challenge is how to integrate lethal means restriction and suicide prevention messages into the definition of responsible firearm ownership; firearm retailers and advocates are key partners in this effort.[34]

While men and women were equally likely to report having ≥1 firearm at home, men were more likely to personally own the firearm, which is consistent with general trends in firearm ownership. Across age groups, men have higher suicide death rates than women in the general population, in part because they are more likely than women to use firearms. Among all those who die by firearm suicide, only a small minority use a recently-purchased firearm.[34, 35] In our study, over half of those of those with a firearm at home said they had easy access to it, emphasizing an opportunity for lethal means counseling and enhanced home safety. Future areas for exploration include gender differences in choice of method – including whether easy access to a home firearm makes a woman more likely to choose it over another method – and in likelihood of and response to lethal means counseling.[25]

A primary study limitation is that the chart review abstraction form asked about assessment of “means to complete suicide (e.g., firearms or presence of medications)”, without separation of assessment of access to different kinds of means. Thus we cannot, from these data, know what proportion of suicidal ED patients had firearm-specific lethal means assessment. In addition, the baseline participant questionnaire did not asses actual access to particular types or quantities of medications or to other lethal means, so we could not further explore these issues. Other limitations include that this was a secondary analysis of a cohort of patients enrolled in a larger trial, and our results may not generalize to the other population. For example, patients who were homeless or without a working phone were not eligible, and individuals with firearms at home may have been less (or more) interested in participating in the ED-SAFE trial, which involved repeated phone calls, among other study activities.

CONCLUSION

Our findings represent an important step forward in suicide prevention. By understanding current patterns of care for patients with acute suicidal thoughts or behaviors, clinical and public health interventions can be tailored to enhance lethal means counseling in emergency departments and other relevant settings. Increasing rates of assessment over the study phases – even without dedicated training of providers – should provide hope of the feasibility of lethal means assessment and counseling in EDs. Yet the fact that a high proportion of patients – including half of those with a firearm at home – did not have documented assessment of lethal means access highlights the need for further work. Future research might explore aspects of counseling itself, including identifying the best messages and messengers for population subgroups, and ways to increase partnerships with firearm retailers, advocates, and related organizations.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Acknowledgments: We would like to acknowledge the time and effort of the ED-SAFE steering committee and of the ED-SAFE investigators, research coordinators and research assistants from the 8 participating sites.

Grant support: This work was supported by U01MH088278 (National Institute of Mental Health), by Paul Beeson Career Development Award K23AG043123 [National Institute on Aging; AFAR; John A. Hartford Foundation; and Atlantic Philanthropies] and by Award number 14-36094 (Joyce Foundation). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Mental Health, the National Institutes of Health, or the other funders.

Footnotes

Disclosures: None of the authors reports any competing interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Yip PS, Caine E, Yousuf S, et al. Means restriction for suicide prevention. Lancet. 2012;379(9834):2393–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60521-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General and National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention [July 29, 2015];2012 National Strategy for Suicide Prevention: Goals and Objectives for Action. 2012 Available at: http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/reports/national-strategy-suicide-prevention/full_report-rev.pdf. [PubMed]

- 3.Barber CW, Miller MJ. Reducing a suicidal person’s access to lethal means of suicide: A research agenda. Am J Prev Med. 2014;47(3, Supplement 2):S264–S272. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boudreaux ED, Cagande C, Kilgannon H, et al. A prospective study of depression among adult patients in an urban emergency department. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;8(2):66–70. doi: 10.4088/pcc.v08n0202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Claassen CA, Larkin GL. Occult suicidality in an emergency department population. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;186:352–3. doi: 10.1192/bjp.186.4.352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ilgen MA, Walton MA, Cunningham RM, et al. Recent suicidal ideation among patients in an inner city emergency department. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2009;39(5):508–17. doi: 10.1521/suli.2009.39.5.508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kvaran RB, Gunnarsdottir OS, Kristbjornsdottir A, et al. Number of visits to the emergency department and risk of suicide: A population-based case-control study. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:227. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1544-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gairin I, House A, Owens D. Attendance at the accident and emergency department in the year before suicide: Retrospective study. Br J Psychiatry. 2003;183:28–33. doi: 10.1192/bjp.183.1.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention Research Prioritization Task Force. A Prioritized Research Agenda for Suicide Prevention: An Action Plan to Save Lives. 2014 Available at: http://actionallianceforsuicideprevention.org/task-force/research-prioritization. Accessed June 18, 2015.

- 10.Kruesi MJP, Grossman J, Pennington JM, et al. Suicide and violence prevention: Parent education in the emergency department. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1999;38(3):250–255. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199903000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Capoccia L, Labre M. Caring for Adult Patients with Suicide Risk: A Consensus-Based Guide for Emergency Departments. Education Development Center, Inc., Suicide Resource Prevention Center; Waltham, MA: 2015. Available at: http://www.sprc.org/ed-guide. Accessed December 10, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weinberger SE, Hoyt DB, Lawrence Iii HC, et al. Firearm-related injury and death in the United States: A call to action from 8 health professional organizations and the American Bar Association. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(7):513–516. doi: 10.7326/M15-0337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Betz ME, Barber C, Miller M. Lethal means restriction as suicide prevention: Variation in belief and practice among providers in an urban ED. Inj Prev. 2010;16:278–281. doi: 10.1136/ip.2009.025296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Betz ME, Miller M, Barber C, et al. Lethal means restriction for suicide prevention: Beliefs and behaviors of emergency department providers. Depress Anxiety. 2013;30(10):1013–20. doi: 10.1002/da.22075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Betz ME, Arias SA, Miller M, et al. Change in emergency department providers’ beliefs and practices after use of new protocols for suicidal patients. Psychiat Serv. 2015;66(6):625–631. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201400244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rogers SC, DiVietro S, Borrup K, et al. Restricting youth suicide: Behavioral health patients in an urban pediatric emergency department. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014;77(3 Suppl 1):S23–8. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boudreaux ED, Miller I, Goldstein AB, et al. The Emergency Department Safety Assessment and Follow-up Evaluation (ED-SAFE): Method and design considerations. Contemp Clin Trials. 2013;36(1):14–24. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2013.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brent DA, Bridge J. Firearms availability and suicide: Evidence, interventions, and future directions. Am Behav Sci. 2003;46(9):1192–1210. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deisenhammer EA, Ing CM, Strauss R, et al. The duration of the suicidal process: How much time is left for intervention between consideration and accomplishment of a suicide attempt? J Clin Psychiat. 2009;70(1):19–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Elnour AA, Harrison J. Lethality of suicide methods. Inj Prev. 2008;14(1):39–45. doi: 10.1136/ip.2007.016246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grossman DC, Mueller BA, Riedy C, et al. Gun storage practices and risk of youth suicide and unintentional firearm injuries. JAMA. 2005;293(6):707–14. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.6.707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shenassa ED, Rogers ML, Spalding KL, et al. Safer storage of firearms at home and risk of suicide: A study of protective factors in a nationally representative sample. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2004;58(10):841–8. doi: 10.1136/jech.2003.017343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grossman J, Dontes A, Kruesi MJP, et al. Emergency nurses’ responses to a survey about means restriction: An adolescent suicide prevention strategy. J Am Psychiatr Nurses Assoc. 2003;9(3):77–85. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Slovak K, Brewer TW. Suicide and firearm means restriction: Can training make a difference? Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2010;40(1):63–73. doi: 10.1521/suli.2010.40.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Slovak K, Brewer TW, Carlson K. Client firearm assessment and safety counseling: The role of social workers. Soc Work. 2008;53(4):358–66. doi: 10.1093/sw/53.4.358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Petrik ML, Gutierrez PM, Berlin JS, et al. Barriers and facilitators of suicide risk assessment in emergency departments: A qualitative study of provider perspectives. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2015.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miller M, Barber C, White RA, et al. Firearms and suicide in the United States: Is risk independent of underlying suicidal behavior? Am J Epidemiol. 2013;178(6):946–955. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwt197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miller M, Lippmann SJ, Azrael D, et al. Household firearm ownership and rates of suicide across the 50 United States. J Trauma. 2007;62(4):1029–34. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000198214.24056.40. discussion 1034-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miller M, Azrael D, Barber C. Suicide mortality in the United States: The importance of attending to method in understanding population-level disparities in the burden of suicide. Annu Rev Public Health. 2012;33:393–408. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031811-124636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Swedler DI, Simmons MM, Dominici F, et al. Firearm prevalence and homicides of law enforcement officers in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(10):2042–8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kalesan B, Villarreal MD, Keyes KM, et al. Gun ownership and social gun culture. Inj Prev. 2015 doi: 10.1136/injuryprev-2015-041586. Epub Jun 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Walters H, Kulkarni M, Forman J, et al. Feasibility and acceptability of interventions to delay gun access in VA mental health settings. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2012;34(6):692–8. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2012.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Betz ME, Wintemute GJ. Physician counseling on firearm safety: A new kind of cultural competence. JAMA. 2015;314(5):449–450. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.7055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vriniotis M, Barber C, Frank E, et al. A suicide prevention campaign for firearm dealers in New Hampshire. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2015;45(2):157–63. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kellermann AL, Rivara FP, Somes G, et al. Suicide in the home in relation to gun ownership. N Engl J Med. 1992;327(7):467–72. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199208133270705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.