The increasing incidence of infections by carbapenem-resistant enterobacteria (CRE), in particular carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae (CRKp), is a significant public health challenge worldwide.1 The interim results of the last European survey on CRE (EuSCAPE project 2013) indicate that CRKp is endemic in Italy, and that this endemicity is mostly contributed to by strains producing KPC-type carbapenemases.

CRKp infections are associated with high morbidity and mortality rates, particularly among Intensive Care Units (ICU) patients, recipients of solid organ transplants (SOT) and patients with hematological malignancies.1–3 The Gruppo Italiano Trapianto Midollo Osseo (GITMO) recently performed a retrospective study (2010–2013) which involved 52 stem cell transplant (SCT) centers to assess the epidemiology and the prognostic factors of CRKp infections in autologous and allogeneic SCT.4 Cases of CRKp infection were reported in 53.4% of the centers and were documented in 0.4% of autologous and 2% of allogeneic SCTs. A CRKp colonization was followed by an infection in about 30% of cases. The infection-related mortality rate was 16% in autologous and 64.4% in allogeneic SCT. A pre-transplant CRKp infection and inadequate first-line treatment were independent factors associated with an increase in mortality in allogeneic SCT patients who developed a CRKp infection. Indeed, despite the administration of a first-line CRKp-targeted antibiotic therapy (CTAT) (see below), 55% of patients who received a CTAT still died. These data underscored the challenge regarding CRKp infections, particularly in the allogeneic-SCT setting, in terms of outcome and management of post-transplant complications, and also raised an issue about the eligibility for transplant among patients who got colonized or had developed a CRKp infection before transplant.

Based on these original data and on the recent literature, a multidisciplinary group of experts from GITMO, the Italian Association of Clinical Microbiologists (Associazione Microbiologi Clinici Italiani; AMCLI), the Italian Society of Infectious and Tropical Diseases (Società Italiana Malattie Infettive e Tropicali; SIMIT), and the Italian National Transplant Center (Centro Nazionale Trapianti; CNT) was convened with the aim of providing consensus recommendations for the management of CRKp infection/colonization in autologous and allogeneic-SCT recipients.

The Expert Panel (EP) included 17 specialists in hematology, infectious diseases, clinical microbiology and nursing, who were selected by virtue of their expertise in research and clinical practice of infections in SCT. The areas of major concern were defined by generating clinical key issues using the criterion of clinical relevance, i.e. impact on patient management and risk of inappropriateness, and recommendations were obtained according to a nominal group technique.

The EP focused its discussion on four key-issues considered relevant for the present recommendations that are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Recommendations for the management of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae (CRKp) infections in stem cell transplant recipients.*

Detection of CRKp carriers before and after SCT

Colonization by CRKp represents a condition predictive of a subsequent infection in immunocompromised patients.4–8 The EP agreed that the detection of CRKp carriers seems to be the crucial means for infection control and appropriate therapy, but well-defined colonization survey strategies (i.e. timing and frequency of tests) have not been standardized. Considering that the primary colonization site of enterobacteria is the intestinal tract, screenings are focused on the detection of intestinal carriage of CRKp, usually by analysis of rectal swabs. Three levels of isolation may be considered in the infection control strategy: known to be colonized, known to be not colonized and results pending.

Infection control strategies and management of CRKp carriers in the SCT setting

Infection control of CRE should be planned in every department, throughout the entire hospital, and at regional, national or multinational level. The differences in morbidity and mortality of infections due to CRE in populations of patients with various underlying diseases and comorbidity profiles should be considered for a comprehensive infection control strategy.3,4,7,8 In a recent survey in a tertiary teaching Italian hospital, when compared to internal medicine patients (4.3/1000 colonization days), the highest incidence of CRKp infections among colonized patients was observed in hematology (26.3; P=0.04) and ICU (13.1; P=0.0004), followed by surgery (8.6; P=0.14), transplant (7.4; P=0.34), and long-term care (4.7; P=0.99). CRKp attributable mortality was highest in hematology (75%) followed by ICU (11%), transplant (7%), long term care (5%), internal medicine and surgery (both 2%).7 In a further multicenter matched case-control study of adult CRKp rectal carriers, the rates of infections among carriers in hematology, SOT, ICU and medicine were 38.9%, 18.8%, 18.5% and 16%, respectively.8 These findings underline the unique impact of CRKp infection in hematologic patients, including SCT recipients, and the importance in considering those colonized patients in lower risk units as likely to be an occult reservoir and a source of the spread of microorganisms to high-risk patients in the hospital.

Candidates for SCT often come to the transplant-unit from centers located in other regions or countries with different risks of carrying CRE. This extensive inter-facility sharing of patients has the potential to facilitate widespread regional and even international transmission of CRE. Recent experiences from Israel and France demonstrated the importance of infection control strategies applied at regional/national level when clonal outbreaks of CRE cannot be controlled by local measures.9,10 The central program for controlling CRE spread included recommendations to both isolate and screen for resistant microorganisms those patients who had previously been hospitalized abroad, and bundled measures to control cross transmission. A quick implementation of nursing staff cohorting to avoid cross contamination was a crucial tool of infection control. A supervised adherence to the guidelines with a feedback on performance to hospital directors, and the addition of specific interventions when and where necessary guaranteed the effectiveness of the interventions. The main results of these national infection control strategies were the decrease in the total number of outbreaks, and the containment of the intrahospital and interhospital spread of CRE infections within the space of a few months. The EP agreed that centralized coordination at any level is essential in the epidemiological control of CRKp infections in high-risk populations, including SCT recipients.

Criteria for the timing of antibiotic therapy and choice of the appropriate regimen in patients at risk for and with documented CRKp infection

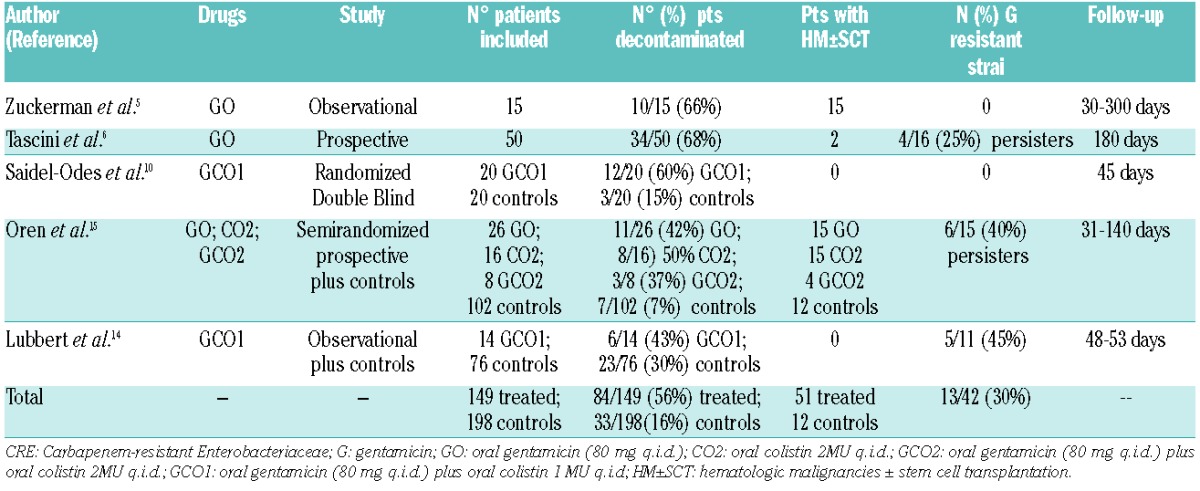

An Expert Panel convened by the 4th European Conference on Infections in Leukemia (ECIL-4) group has recently published guidelines for the management of empirical and targeted therapy in an era of emerging resistant gram-negative pathogens in leukemia patients and SCT recipients.11,12 This group has recommended that empirical therapy should be tailored according to local epidemiology, adopting an escalation/deescalation approach in order to reduce the use of carbapenems and colistin to indispensable amounts. An appropriate CTAT was defined as a combination including at least two among colistin/polymyxin B, tigecycline and gentamicin, preferably with the addition of meropenem, and eventually also fosfomycin. The use of high, unconventional doses for some drugs was suggested.12 The GITMO study confirmed the independent role of a first line CTAT on survival; however, half the patients who received a first line CTAT still died due to the infection.4 It is notable that in this study, out of 22 patients with a CRKp infection documented before allogeneic SCT, 10 (45.4%) relapsed early after transplant, and 9 out of those 10 (90%) who relapsed died despite early CTAT. These findings raise the crucial problem of the unsatisfactory efficacy of the available treatments, the need for infection prevention in patients at risk who need to avoid contact with these pathogens, and an attempt to eradicate their colonization. In the last few years, the efficacy and safety of selective digestive decontamination (SDD) with non absorbable antibiotics for the eradication of CRE carriage was evaluated in populations with various underlying conditions5,6,13–15 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Oral decontamination for Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae in general population and patients with hematologic malignancies.

The available data seem to show that SDD, in particular with oral gentamicin, may be in general a suitable option in CRKp carriers with a moderate risk of developing resistance to gentamicin (see Table 2), especially in persistent carriers during decontamination. However, in view of the limited experience in hematologic populations and the need for further data about safety, there is poor evidence to support a recommendation on SDD in SCT patients colonized by CRKp, but this topic may deserve appropriate investigation.

The impact of CRKp issues on patients eligibility for SCT and on SCT strategies

The EP found no data in the literature about the impact of the CRKp issue on eligibility for SCT and other related strategies and based the discussion on the GITMO experience,4 and the opinions of the experts. The EP agreed that, considering the crucial importance of SCT in the comprehensive treatment strategy for some hematological patients, CRKp colonization does not represent a contraindication to both autologous and allogeneic-SCT. On the contrary, a recent CRKp infection before SCT, which is associated with a high-risk of a fatal relapse, requires a careful evaluation of the risk-benefit ratio for performing SCT.

In conclusion, CRKp infections in SCT patients have a dramatic impact on outcome, particularly in the allogeneic setting. Carrier detection represents a critical aspect, and any intervention requires coordination at intrahospital and interhospital level. In the present report, experts in the field produced recommendations for the prevention and management of CRKp infection/colonization in SCT patients and suggested some topics of investigation. The questions raised by, and the conclusions drawn from this consensus conference may form the basis for improving infection control of CRE infections in the SCT population.

Footnotes

Information on authorship, contributions, and financial & other disclosures was provided by the authors and is available with the online version of this article at www.haematologica.org.

References

- 1.Munoz-Price LS, Poirel L, Bonomo RA, et al. Clinical epidemiology of the global expansion of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemases. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13(9):785–796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Satlin MJ, Jenkins SG, Walsh TJ. The Global Challenge of Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae in Transplant Recipients and Patients With Hematologic Malignancies. Clin Infect Dis. 2014; 58(9):1274–1283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pagano L, Caira M, Trecarichi EM, et al. Carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae and hematologic malignancies. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20(7):1235–1236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Girmenia C, Rossolini GM, Piciocchi A, et al. Infections by carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in stem cell transplant recipients: a nationwide retrospective survey from Italy. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2015;50(2):282–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zuckerman T, Benyamini N, Sprecher H, et al. SCT in patients with carbapenem resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae: a single center experience with oral gentamicin for the eradication of carrier state. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2011;46(9):1226–1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tascini C, Sbrana F, Flammini S, et al. Oral gentamicin gut decontamination for prevention of KPC-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae infections: the relevance of concomitant systemic antibiotic therapy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58(4):1972–1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bartoletti M, Lewis RE, Tumietto F, et al. Prospective, Cross-Sectional Observational Study of Hospitalized Patients Colonized with Carbapenemase-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae (CR-KP). Presented at: 23rd European Conference on Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases Berlin, Germany, 27–30 April 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giannella M, Trecarichi EM, De Rosa FG, et al. Risk factors for carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae bloodstream infection among rectal carriers: a prospective observational multicentre study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20(12):1357–1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schwaber MJ, Lev B, Israeli A, et al. Containment of a country-wide outbreak of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in Israeli hospitals via a nationally implemented intervention. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(7):848–855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fournier S, Monteil C, Lepainteur M, et al. Long-term control of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae at the scale of a large French multihospital institution: a nine-year experience, France, 2004 to 2012. Euro Surveill. 2014;19(19):20802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Averbuch D, Orasch C, Cordonnier C, et al. European guidelines for empirical antibacterial therapy for febrile neutropenic patients in the era of growing resistance: summary of the 2011 4th European Conference on Infections in Leukemia. Haematologica. 2013; 98(12):1826–1835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Averbuch D, Cordonnier C, Livermore DM, et al. Targeted therapy against multi-resistant bacteria in leukemic and hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients: guidelines of the 4th European Conference on Infections in Leukemia (ECIL-4, 2011). Haematologica. 2013;98(12):1836–1847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saidel-Odes L, Polachek H, Peled N, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of selective digestive decontamination using oral gentamicin and oral polymyxin E for eradication of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae carriage. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2012;33(1):14–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lübbert C, Faucheux S, Becker-Rux D, et al. Rapid emergence of secondary resistance to gentamicin and colistin following selective digestive decontamination in patients with KPC-2-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae: a single-centre experience. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2013;42(6):565–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oren I, Sprecher H, Finkelstein R, et al. Eradication of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae gastrointestinal colonization with non-absorbable oral antibiotic treatment: A prospective controlled trial. Am J Infect Control. 2013;41(12):1167–1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]