Abstract

Background

Hypertension and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) are important causes of non-ischaemic heart failure (HF). Understanding the pathophysiology of early HF may guide screening. We hypothesised that the underlying physiology differed according to aetiology.

Methods

In this cross-sectional study of 521 asymptomatic community-based subjects ≥65 years with ≥1 HF risk factors, 187 participants (36%) had T2DM and hypertension (T2DM+/HTN+), 109 (21%) had T2DM with no hypertension (T2DM+/HTN−) and 72 (14%) had neither T2DM nor hypertension (T2DM−/HTN−). In 153 patients (29%), clinic blood pressure was ≥140/90 mm Hg, defined as active hypertension (T2DM−/HTN+). All underwent a comprehensive echocardiogram, including conventional parameters for systolic and diastolic function as well as global longitudinal strain (GLS), diastolic strain (DS) and DS rate (DSR). A 6 min walk (6MW) test was used to assess functional capacity.

Results

GLS in T2DM−/HTN+ group (−18.9±2.7%) was similar to that in T2DM−/HTN− group (−19.4±2.4%) and greater than T2DM+/HTN− (−18.0±2.8%, p=0.005). DS in T2DM−/HTN− (0.47±0.15%) exceeded that in T2DM−/HTN+ (0.43±0.14%) and T2DM+/HTN− (0.43±0.13%). 6MW distance was preserved in T2DM−/HTN+ (482±85 m) and reduced in T2DM+/HTN− (469±93, p<0.001). Those with T2DM and active hypertension had worst GLS, DS, DSR and shortest 6MW distance (p<0.002). In multivariable analysis, GLS was associated with T2DM but neither active hypertension nor a history of hypertension. Diastolic markers and left ventricular (LV) mass were associated with hypertension and T2DM. Thus, patients with HF risk factors show different functional disturbances according to aetiology.

Conclusions

Patients with hypertension had relatively less impaired GLS and preserved 6MW distance but more impaired diastolic function.

Keywords: HEART FAILURE

Key questions.

What is already known about this subject?

New imaging techniques may be used to identify the early stages of heart failure (HF). It is unclear as to whether these are interchangeable or should be used in specific circumstances.

What does this study add?

Patients with HF risk factors show different functional disturbances according to aetiology. Patients with hypertension had relatively preserved global longitudinal strain and 6 min walk test distance but more impaired diastolic strain (DS) and DS rate.

How might this impact on clinical practice?

The epidemiology of HF is changing, with hypertension and type 2 diabetes being the main causes of non-ischaemic HF. Early detection and management may help to reduce presentations with overt HF, and a mechanistic understanding of the different aetiologies may help appropriate therapy.

Introduction

The aetiology and pathophysiology of heart failure (HF) is undergoing a transition. With the decline of coronary artery disease (CAD), hypertension and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) have become the most common aetiologies of incident HF. Among these preclinical individuals with stage A HF,1 the risk of incident HF with hypertension is known to be relatively low than CAD and T2DM;2 the role of hypertension as the leading cause of HF3 reflects its prevalence in the community. In contrast, the risk of incident HF is nearly twice as high in those with T2DM than with hypertension.2 Conventional echocardiographic measures of diastolic dysfunction and myocardial strain analysis have been well studied in T2DM and are early markers of diabetic cardiomyopathy.4–6 Unfortunately, the conventional echocardiographic assessment of diastolic function in hypertension often provides inconsistencies7 which may compromise its use to screen for preclinical HF.

A screening and early treatment process could limit the progression to HF arising from the heavy burden of hypertension and T2DM in the community. However, it is not clear whether strain or conventional diastolic measures would be optimal for this purpose, whether they are analogous, or indeed if the underlying ethology has a differential effect on either marker. An understanding of the pathophysiological differences of different causes of preclinical HF might guide screening for early intervention and disease prevention. We hypothesised that the optimal cardiac markers vary with the underlying aetiology, and that the degree of underlying cardiac dysfunction correlates with their functional capacity measured by 6 min walk (6MW) test distance—a simple measure of the functional status of patients and a predictor of morbidity and mortality in left ventricular (LV) dysfunction.8

Methods

Patient selection

Asymptomatic individuals aged ≥65 years with HF risk factors were recruited through local media advertising based on the presence of ≥1 of the following HF risk factors: (1) hypertension (based on self-report of diagnosis including medication); (2) T2DM (based on self-report of diagnosis including medication); (3) obesity (body mass index (BMI) ≥30); (4) previous chemotherapy; (5) family history of HF and (6) previous history of heart disease (but not existing HF). The exclusion criteria were patients with (1) a history of HF, (2) a history of CAD, (3) a history (or evidence on baseline echocardiogram) of >moderate valvular heart disease, (4) LV ejection fraction (LVEF) <40% on baseline echocardiogram and (5) inability to acquire interpretable images for speckle-tracking imaging analysis at baseline. This study was performed in accordance with a research protocol approved by the Tasmanian Human Research Ethics Committee. A written informed consent was obtained from each participant after explaining the nature and purposes, complexity and level of risk of the study.

Data collection

Data were collected prospectively at facilities in the community from all participants enrolled in the study. All completed standard questionnaires relating to health status (EuroQol 5-dimension index, EQ5D), functional capacity (Duke Activity Score Index, DASI), frailty (Study of Osteoporotic Fractures (SOF) frailty index) and symptom status (Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire, MLHFQ). Anthropometric measurements were obtained and BMI was calculated. Waist and hip measurements were obtained. Standard serial blood pressure (BP) measurements, standard 12-lead ECG and a comprehensive transthoracic echocardiogram including speckle-tracking imaging were performed. 6MW test was used to assess submaximal functional capacity.

Other collected data included socioeconomic indicators, complete medical history, family history, cardiovascular risk factors, heart rate and patient-reported outcome measures.

BP measurements

Peripheral and derived aortic BP readings were obtained using a validated technique,9 with a commercially available pulse wave analysis system (Mobil-O-Graph PWA, IEM, Stolberg, Germany). Serial measurements were conducted after a 10 min rest in a quiet room, with readings obtained twice in a seated position at rest and immediately after 6MW. To define active hypertension, an averaged (at least two) sitting systolic BP (SBP) ≥140 mm Hg or diastolic BP (DBP) ≥90 mm Hg was used as cut-off.10 11

Standard echocardiographic study

Standard transthoracic two-dimensional (2D) and Doppler echocardiographic studies were performed using a commercial system (Siemens ACUSON SC2000, 4V1c and 4Z1c probes, Siemens Healthcare, Mountain View, California, USA) in accordance with the American Society of Echocardiography guidelines.12 13 LV dimensions during diastole and systole and wall thicknesses were measured from parasternal long-axis views according to the recommended criteria. LV mass was calculated according to the guidelines and indexed for body surface area (BSA; g/m2). LV hypertrophy (LVH) was defined as LV mass index (LVMi) >115 g/m2 in men and >95 g/m2 in women.12 LV and left atrial (LA) volumes were calculated by the Simpson biplane method, and indexed to BSA (LAVi). Abnormal LAVi was defined as >34 mL/m2.12 For diastolic function assessment, mitral inflow peak early diastolic velocity (E), peak late diastolic velocity (A), E/A ratio and E wave deceleration time (DT) were measured; E/A<0.8 identified delayed relaxation. Tissue Doppler mitral annular early diastolic velocity (e′) was assessed at septal and lateral walls and averaged for calculation of E/e′; an average E/e′≥15 was considered consistent with raised filling pressure.

Myocardial strain

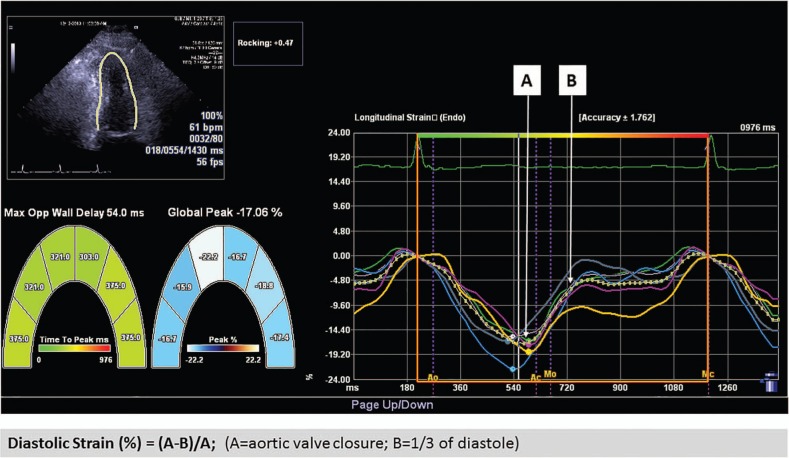

Speckle tracking was used for the measurement of global longitudinal strain (GLS), from three standard apical views, using commercial software (Syngo VVI, Siemens Medical Solutions). After manual tracing of LV endocardial border during end systole, this was automatically tracked throughout the cardiac cycle. GLS was obtained by averaging all 18 segment strain values from the three standard views; abnormal GLS is defined as >−18%.14 Global diastolic strain (DS) was obtained by averaging of all 18 segment strain values and measured according to method published by Ishii et al.15 Calculation of DS was determined as (A−B)/A×100% (A=the systolic value of strain at closure of aortic valve; B=the value of strain at the one-third point of diastole duration) (figure 1). DS rate (DSR) was determined from the average of 18 segments of early DSR.

Figure 1.

Measurement of GLS and DS. DS, diastolic strain; GLS, global longitudinal strain.

Functional capacity assessment

The 6MW test distance was used for the measurement of submaximal functional capacity in this study. 6MW was conducted following a standardised protocol.16

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean±SD after testing for normal distribution with the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Data deviating from normality are expressed as median and IQR. Categorical variables are expressed as percentages. Multigroup comparison was performed by the analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni post hoc analysis when data showed a normal distribution. Otherwise, the Kruskal-Wallis test was used for comparison of non-normally distributed variables. Linear regression analysis was used to examine the associations between clinical, echocardiographic and functional variables before and after adjustment for age, gender and other clinical variables. Logistic regression analysis was used to examine the association of low functional capacity and abnormal GLS. Statistical analysis was performed using a standard statistical software package (SPSS software 22.0, SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois, USA). Statistical significance was defined by p<0.05.

Results

Population characteristics

There were 535 community individuals potentially eligible for assessment during the study period. After exclusion of 14 individuals after the baseline echo screening due to valvular pathology and poor LVEF, the final number of individuals included in this study was 521 (age 71±5 years (IQR 67–74)), 49% of whom were men. All had completed assessment according to the standard protocol. The listed HF risk factors were present in all of these participants, with self-reported hypertension being the most common (82%), followed by T2DM (54%), obesity (47%), family history of heart disease at young age (36%), a known cardiac condition without overt HF (10%) and previous chemotherapy (9.2%). All had normal LVEF (≥50%). A total of 340 out of 521 participants (65%) met the criteria of active hypertension (SBP ≥140 mm Hg and or DBP≥90 mm Hg).

Four groups were derived according to the status of T2DM and the presence of hypertension, namely T2DM+/HTN−, T2DM/HTN+, T2DM+/HTN+ and T2DM−/HTN−. These four aetiological groups were studied to test the individual effect of hypertension versus T2DM and combined effect of T2DM+HTN (table 1). There was no difference in age and gender between T2DM−/HTN+ and T2DM+/HTN−. Other risk factors including obesity, chemotherapy, family history and history of heart disease were also similar between the two groups (table 1). However, compared with T2DM−/HTN+, T2DM+/HTN− had significantly higher prevalence of dyslipidaemia (p<0.001) and higher Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) and Framingham Heart Study (FHS) score (p<0.001). The T2DM+/HTN+ group had significantly greater BMI and dyslipidaemia. Baseline medication history (including β-blocker (BB), angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEi), angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB), diuretics and calcium antagonists) was similar. A greater percentage of participants with T2DM+/HTN+ were on statin therapy than other groups.

Table 1.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with stage A heart failure, categorised by aetiology

| Total (n=521) | T2DM−/HTN+ (n=153) | p (HTN-control) | T2DM+/HTN− (n=109) | p (T2DM-control) | p (HTN-T2DM) | T2DM+/HTN+ (n=187) | p (both-control) | p (both-HTN) | p (both-T2DM) | T2DM−/HTN− (n=72) | p (total) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 71 (5) | 71 (5) | 71 (4) | 71 (5) | 71 (5) | 0.742 | ||||||

| Gender male, n (%) | 256 (49) | 65 (43) | 0.478 | 59 (54) | 0.028 | 0.063 | 105 (56) | 0.007 | 0.012 | 0.736 | 27 (38) | 0.010 |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 67 (59–75) | 66 (58–74) | 1.000 | 68 (60–76) | 0.102 | 0.324 | 68 (61–75) | 0.162 | 0.530 | 1.000 | 64 (59–72) | 0.035 |

| SBP (mm Hg) | 146 (18) | 156 (15) | <0.001 | 130 (8) | 1.000 | <0.001 | 154 (14) | <0.001 | 0.460 | <0.001 | 128 (10) | <0.001 |

| DBP (mm Hg) | 82 (11) | 90 (11) | <0.001 | 74 (7) | 1.000 | <0.001 | 84 (10) | <0.001 | 0.315 | <0.001 | 74 (7) | <0.001 |

| Pulse pressure (mm Hg) | 64 (15) | 67 (15) | <0.001 | 55 (8) | 1.000 | <0.001 | 69 (15) | <0.001 | 0.324 | <0.001 | 54 (12) | <0.001 |

| Mean artery pressure | 108 (12) | 114 (13) | <0.001 | 99 (7) | 1.000 | <0.001 | 111 (9) | <0.001 | 0.149 | <0.001 | 100 (9) | <0.001 |

| Central SBP (mm Hg) | 149 (20) | 158 (20) | <0.001 | 131 (13) | 0.947 | <0.001 | 154 (18) | <0.001 | 0.451 | <0.001 | 138 (15) | <0.001 |

| Central DBP (mm Hg) | 83 (10) | 87 (11) | <0.001 | 78 (6) | 1.000 | <0.001 | 85 (9) | <0.001 | 0.215 | <0.001 | 77 (9) | <0.001 |

| ΔSBP (pre-post 6MW) | 18 (20) | 18 (24) | 20 (19) | 0.392 | <0.001 | 18 (19) | 16 (16) | 0.722 | ||||

| Body mass index (g/m2) | 29 (26–33) | 29 (26–32) | 1.000 | 28 (26–32) | 1.000 | 1.000 | 31 (27–34) | 0.005 | 0.050 | 0.032 | 28 (25–31) | 0.002 |

| HF risk factors | ||||||||||||

| ARIC risk (4 year) (%) | 6.2 (3.6–11.4) | 4.2 (2.5–7.3) | 0.104 | 7.3 (4.6–11.9) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 9.2 (6.2–14.9) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.048 | 3.2 (1.8–4.9) | <0.001 |

| FHS risk (4 year) (%) | 4.0 (2.0–6.5) | 3.0 (2–4) | 0.186 | 4.0 (3–10) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 5.0 (3–14) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 1.000 | 2.5 (1.8–3) | <0.001 |

| T2DM, n (%) | 296 (57) | 0 (0) | n/a | 109 (100) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 187 (100) | <0.001 | <0.001 | n/a | 0 (0) | <0.001 |

| Obesity, n (%) | 245 (47) | 67 (44) | 0.197 | 46 (42) | 0.313 | 0.798 | 107 (57) | 0.001 | 0.014 | 0.013 | 25 (35) | 0.003 |

| History HTN, n (%) | 421 (81) | 134 (88) | 0.556 | 75 (67) | 0.015 | <0.001 | 151 (81) | 0.457 | 0.089 | 0.020 | 61 (85) | 0.002 |

| Chemotherapy, n (%) | 46 (9) | 13 (9) | 0.529 | 7 (6) | 0.263 | 0.533 | 18 (10) | 0.722 | 0.719 | 0.339 | 8 (11) | 0.701 |

| Family history, n (%) | 184 (35) | 63 (41) | 0.944 | 44 (40) | 0.862 | 0.895 | 47 (25) | 0.009 | 0.002 | 0.006 | 30 (42) | 0.004 |

| History of heart disease, n (%) | 47 (9) | 21 (14) | 0.011 | 9 (8) | 0.131 | 0.171 | 15 (8) | 0.127 | 0.089 | 0.943 | 2 (3) | 0.049 |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 284 (55) | 60 (41) | 0.580 | 64 (63) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 121 (72) | 0.018 | <0.001 | 0.159 | 39 (56) | <0.001 |

| Charlson score | 1.0 (0.0–2.0) | 0 (0–1) | 1.000 | 1.0 (1–3) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 1.0 (1–2) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 1.000 | 0 (0–1) | <0.001 |

| Medication, n (%) | ||||||||||||

| β-blocker | 38 (7) | 12 (7.8) | 11 (10) | 10 (5.3) | 5 (6.9) | 0.495 | ||||||

| ACEi/ARB | 360 (69) | 104 (68) | 69 (63) | 137 (73) | 50 (69) | 0.344 | ||||||

| Diuretics | 67 (13) | 22 (16) | 11 (11) | 21 (13) | 13 (19) | 0.432 | ||||||

| Calcium antagonist | 115 (22) | 26 (19) | 24 (25) | 47 (28) | 18 (27) | 0.273 | ||||||

| Lipid-lowering medications | 287 (55) | 57 (41) | 0.580 | 75 (76) | <0.001 | 125 (75) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.933 | 30 (45) | <0.001 | |

| Antiplatelet | 193 (37) | 44 (32) | 0.163 | 41 (41) | 0.961 | 80 (49) | 0.334 | 0.003 | 0.246 | 28 (42) | 0.031 | |

| Functional capacity | ||||||||||||

| 6MW (m) | 463 (101) | 482 (85) | 1.000 | 469 (93) | 1.000 | 1.000 | 438 (119) | 0.019 | <0.001 | 0.067 | 479 (81) | <0.001 |

| Patient-reported outcome measure | ||||||||||||

| DASI MET | 8.3 (1.0–8.9) | 8.9 (7.6–9.0) | 1.000 | 8.0 (6.6–9.0) | 0.036 | 0.053 | 7.7 (6.6–9.0) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 1.000 | 8.9 (8.0–9.0) | <0.001 |

| EQ5D | 0.837 (0.74–1.0) | 0.837 (0.77–1.0) | 1.000 | 0.837 (0.72–1.0) | 0.144 | 0.177 | 0.806 (0.73–1.0) | 0.039 | 0.027 | 1.000 | 0.879 (0.77–1.0) | 0.004 |

| EQ VAS | 80 (70–90) | 85 (70–93) | 1.000 | 80 (70–90) | 0.029 | 0.202 | 80 (70–90) | 0.024 | 0.179 | 1.000 | 88 (79–95) | 0.005 |

| MLHF | 1.0 (0.0–9.0) | 1.0 (0–7) | 1.0 (0–9.5) | 1.0 (0–12) | 1.0 (0–6.8) | 0.971 | ||||||

Continuous variables are listed either as mean (SD) or median (low quartile-upper quartile); categorical variables are listed as number (%).

6MW, 6 min walk test; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; ARIC, the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities; Both=HTN+/T2DM+; Control=HTN−/T2DM−; DASI MET, Duke Activity Score Index with metabolic equivalent task; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; EQ5D, European Quality of Life-5 dimensions; EQVAS, European Quality of Life Visual Analogue Scale; FHS, Framingham Heart Study; HTN, hypertension; MLHF, Minnesota Living with Heart Failure score; PROMs, patient-reported outcome measures; SBP, systolic blood pressure; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Echocardiographic assessment

Baseline echocardiographic measures stratified by the four aetiological groups are summarised in table 2. LVMi was higher in hypertensive groups (T2DM−/HTN+ and T2DM+/HTN+), but LVEF, LV end-diastolic volume (LVEDV) and relative wall thickness (RWT) were similar among the groups. Of the conventional diastolic parameters, mitral annular e′ (average of medial and lateral) was lower and E/e′ (average of medial and lateral) was higher in T2DM−/HTN+ and T2DM+/HTN+ than T2DM+/HTN−. Using E/e′ >15 as cut-off, the percentage of abnormal E/e′ in the groups was different (p=0.049). T2DM+/HTN+ had the highest prevalence of diastolic dysfunction (82%) according to the current recommendations of the American Society of Echocardiography,13 although this was not statistically significant among the groups.

Table 2.

Echocardiographic characteristics of patients with stage A heart failure, categorised by aetiology

| Total (n=521) | T2DM−/HTN+ (n=153) | p (HTN-control) | T2DM+/HTN− (n=109) | p (T2DM-control) | p (HTN-T2DM) | T2DM+/HTN+ (n=187) | p (both-control) | P (HTN-both) | p (T2DM-both) | T2DM−/HTN− (n=72) | p (total) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LVIDd | 4.6 (0.6) | 4.6 (0.6) | 4.6 (0.5) | 4.6 (0.6) | 4.5 (0.5) | 0.376 | ||||||

| LVEDV (2D) (mL) | 88 (26) | 88 (22) | 85 (25) | 91 (27) | 86 (28) | 0.189 | ||||||

| LVEF (%) | 63 (6) | 64 (6) | 64 (6) | 63 (7) | 65 (6) | 0.115 | ||||||

| RWT | 0.43 (0.1) | 0.43 (0.1) | 0.43 (0.1) | 0.44 (0.1) | 0.42 (0.1) | 0.289 | ||||||

| GLS (%) | −18.3 (2.7) | −18.9 (3) | 1.000 | −18.0 (3) | 0.005 | 0.056 | −17.4 (3) | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.436 | −19.4 (2) | <0.01 |

| Abnormal GLS, n (%) | 220 (42) | 50 (33) | 51 (47) | 102 (55) | 17 (24) | <0.01 | ||||||

| DD (grade_0), n (%) | 102 (20) | 32 (21) | 23 (21) | 30 (16) | 17 (24) | 0.649 | ||||||

| DD (grade_I), n (%) | 298 (57) | 87 (57) | 58 (53) | 116 (62) | 37 (51) | |||||||

| DD (grade_II), n (%) | 100 (19) | 27 (18) | 21 (19) | 36 (19) | 16 (22) | |||||||

| E/A | 0.8 (0.2) | 0.80 (0.2) | 0.82 (0.21) | 0.78 (0.20) | 0.83 (0.18) | 0.203 | ||||||

| DT (ms) | 249 (51) | 247 (54) | 248 (53) | 253 (52) | 245 (39) | 0.597 | ||||||

| e′’ (cm/s) | 7.7 (1.6) | 7.6 (1.6) | 0.170 | 7.9 (1.7) | 1.000 | 1.000 | 7.5 (1.5) | 0.013 | 1.000 | 0.160 | 8.2 (1.6) | 0.010 |

| E/e′ | 10.1 (3) | 10.1 (3.2) | 0.135 | 10.0 (2.7) | 0.279 | 1.000 | 10.6 (3.2) | 0.003 | 0.817 | 0.731 | 9.1 (2.6) | 0.006 |

| Preclinical HF (E/e′15) (n, %) | 70 (13) | 22 (14) | 11 (10) | 33 (20) | 4 (6) | 0.049 | ||||||

| Diastolic strain (%) | 0.41 (0.15) | 0.43 (0.15) | 0.278 | 0.43 (0.13) | 0.411 | 1.000 | 0.39 (0.15) | 0.003 | 0.417 | 0.411 | 0.47 (0.15) | 0.006 |

| Diastolic SR (1/s) | 0.96 (0.26) | 0.97 (0.26) | 0.280 | 0.97 (0.27) | 0.278 | 1.000 | 0.91 (0.25) | 0.001 | 0.117 | 0.297 | 1.05 (0.25) | 0.001 |

| LAVi (mL/m2) | 31 (10) | 31 (10) | 31 (10) | 33 (10) | 30 (10) | 0.148 | ||||||

| LVMi (g/m2) | 93 (24) | 96 (22) | 0.023 | 88 (21) | 1.000 | 0.033 | 96 (26) | 0.017 | 1.000 | 0.024 | 86 (21) | 0.001 |

| Preclinical HF (LVH) (n, %) | 143 (27) | 58 (38) | 16 (15) | 58 (31) | 11 (15) | <0.01 |

Continuous variables are listed as mean (SD); categorical variables are listed as number (%).

Both=HTN+/T2DM+; control=HTN−/T2DM−; DD, diastolic dysfunction grading according to ASE recommendation; GLS, global longitudinal strain; HTN, hypertension; LAVi, left atrium volume index; LVEDV, left ventricular end-diastolic volume; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVH, left ventricular hypertrophy; LVIDd, left ventricular internal dimension during end diastole; LVMi, left ventricular mass index; RWT, relative wall thickness; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus.

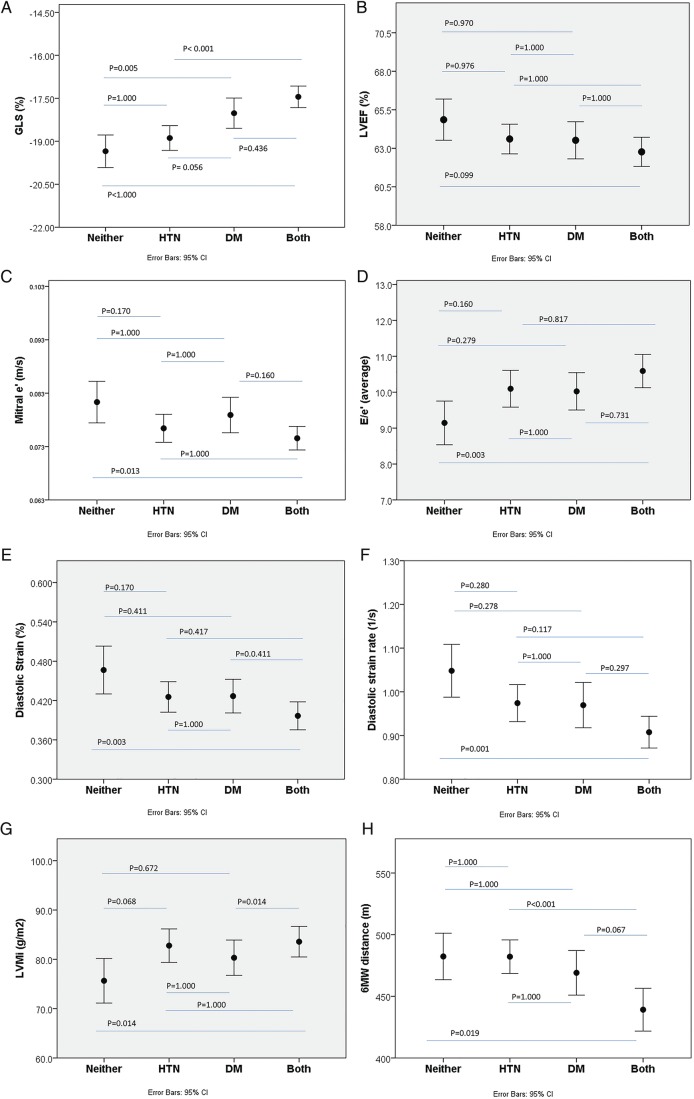

Echocardiographic assessment using speckle-tracking analysis is also summarised in table 2. GLS was significantly lower in T2DM+/HTN− and T2DM+/HTN+. Using −18% as cut-off, abnormal GLS was present in 42% of the whole cohort, most commonly in those with T2DM (T2DM+/HTN− and T2DM+/HTN+). DS and DSR were reduced in T2DM−/HTN+, T2DM+/HTN− and T2DM+/HTN+. Comparison of conventional and speckle tracking echocardiography (STE). analysis measures among and between four groups is shown in figure 2A–H.

Figure 2.

Association of LV function with four groups of hypertension and T2DM. Abnormal strain (A) but not EF (B). Diastolic markers (C–F), LV mass (G) and exercise capacity (H) were impaired in the presence of hypertension and T2DM. LV, left ventricular; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Association of hypertension and T2DM with cardiac changes

The association between abnormal functional parameters and T2DM and hypertension was tested using univariable analysis, followed by two multivariable models to test the independent association between T2DM, a history of hypertension and active hypertension (the latter two being entered into each model separately) (table 3). When modelled with age, gender, BMI and HR, reduced GLS was independently associated with T2DM but not hypertension (either history or active). In contrast, diastolic parameters were generally associated with active hypertension as well as T2DM.

Table 3.

Association of T2DM, history and actual hypertension with abnormal myocardial function

| GLS | DS | DSR | e′ | E/e′ | E/A | LVMi | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ß (95% CI) | p Value | ß (95% CI) | p Value | ß (95% CI) | p Value | ß (95% CI) | p Value | ß (95% CI) | p Value | ß (95% CI) | p Value | ß (95% CI) | p Value | |

| Univariate analysis | ||||||||||||||

| T2DM | 1.383 (0.922 to 1.845) | <0.001 | −0.031 (−0.056 to −0.01) | 0.017 | −0.068 (−0.11 to −0.022) | 0.004 | −0.002 (−0.005 to 0.001) | 0.191 | 0.603 (0.073 to 1.134) | 0.026 | −0.015 (−0.051 to 0.020) | 0.396 | 0.097 (−3.99 to 4.19) | 0.963 |

| History HTN | −0.156 (−0.755 to 0.443) | 0.608 | −0.007 (−0.040 to 0.025) | 0.649 | −0.012 (−0.07 to 0.046) | 0.679 | −0.002 (−0.006 to 0.001) | 0.214 | 0.689 (0.021 to 1.357) | 0.043 | 0.011 (−0.034 to 0.057) | 0.622 | 5.82 (0.695 to 10.94) | 0.026 |

| Active HTN | 0.463 (−0.031 to 0.957) | 0.066 | −0.033 (−0.06 to −0.007) | 0.014 | −0.063 (−0.11 to −0.016) | 0.009 | −0.005 (−0.007 to −0.002) | 0.002 | 0.711 (0.160 to 1.262) | 0.012 | −0.037 (−0.074 to 0.001) | 0.053 | 8.72 (4.53 to 12.92) | 0.000 |

| Model with history of HTN* | ||||||||||||||

| T2DM | 0.972 (0.522 to 1.423) | <0.001 | −0.021 (−0.043 to 0.000) | 0.054 | −0.062 (−0.11 to −0.015) | 0.01 | −0.003 (−0.006 to −0.001) | 0.02 | 0.764 (0.229 to 1.298) | 0.005 | −0.000 (−0.025 to 0.035) | 0.996 | −1.553 (−5/43 to 2.321) | 0.431 |

| History HTN | −0.025 (−0.578 to 0.529) | 0.931 | −0.015 (−0.042 to 0.012) | 0.275 | −0.016 (−0.073 to 0.042) | 0.59 | −0.002 (−0.006 to 0.001) | 0.164 | 0.742 (0.086 to 1.399) | 0.027 | 0.011 (−0.032 to 0.055) | 0.615 | 4.26 (−0.493 to 9.02) | 0.098 |

| Model with active HTN* | ||||||||||||||

| T2DM | 1.00 (0.56 to 1.45) | <0.001 | −0.022 (−0.04 to −0.001) | 0.044 | −0.064 (−0.11 to −0.02) | 0.01 | −0.003 (−0.006 to −0.001) | 0.017 | 0.726 (0.19 to 1.26) | 0.007 | −0.003 (−0.04 to 0.03) | 0.848 | −1.564 (−5.375 to 2.247) | 0.421 |

| Active HTN | 0.408 (−0.05 to 0.86) | 0.079 | −0.035 (−0.06 to −0.013) | 0.002 | −0.059 (−0.11 to −0.013) | 0.013 | −0.005 (−0.007 to −0.002) | 0.001 | 0.691 (0.151 to 1.23) | 0.012 | −0.033 (−0.069 to 0.032) | 0.848 | 7.029 (3.144 to 10.91) | 0.000 |

*Adjusted for age, gender, BMI and HR.

DS, diastolic strain; DSR, diastolic strain rate; GLS, global longitudinal strain; HTN, hypertension; LVMi, left ventricular mass index; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Association of exercise capacity with cardiac changes in hypertension and T2DM

The 6MW test distance in the entire cohort correlated with GLS (r=−0.11, p=0.01) and E/e′ (r=−0.10, p=0.03) but not other diastolic parameters or LV mass. 6MW distance in subgroups is shown in figure 2H. Compared with T2DM−/HTN−, T2DM−/HTN+ had preserved 6MW distance, while T2DM+/HTN− had a non-significant reduction and T2DM+/HTN+ had significantly lower 6MW distance (p=0.019). Multivariable analysis showed T2DM was independently associated with reduced 6MW in both models (history of hypertension and active hypertension). In contrast, active or history of hypertension was associated with preserved 6MW after adjustment for age, gender, height, SBP and heart rate (table 4). Table 5 summarises the association of 6MW distance with abnormal cardiac functional parameters, after adjusting for age, gender, height, HR, SBP and T2DM. 6MW was independently associated with GLS, DS and LVMi, not with other diastolic parameters. In multivariable logistic analysis using GLS (−18% cut-off) and 6MW (lower quartile distance: 410 cut-off), those with 6MW distance <410 m were associated with abnormal GLS with an OR of 1.61 (95% CI 1.07 to 2.42, p=0.02).

Table 4.

Association of 6MW distance with hypertension and T2DM status

| Univariable analysis | Model with history of hypertension | Model with active hypertension |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r2 | ß (95% CI) | p Value | ß (95% CI) | r2 | p Value | ß (95% CI) | p Value | r2 | |

| Age | 0.090 | −6.314 (−8.06 to −4.56) | 0.000 | 0.182 | 0.181 | ||||

| Male | 0.023 | 30.8 (13.4 to 48.1) | 0.001 | ||||||

| Height | 0.050 | 2.274 (1.41 to 3.14) | 0.000 | ||||||

| SBP | 0.017 | −0.742 (−1.24 to −0.25) | 0.003 | ||||||

| HR | 0.029 | −1.559 (−2.345 to −0.773) | 0.000 | ||||||

| T2DM | 0.024 | −31.66 (−49.1 to −14.2) | 0.000 | −34.5 (−51.2 to −17.8) | <0.001 | −35.29 (−51.8 to −18.7) | <0.001 | ||

| History of HTN | 0.000 | 2.72 (−19.44 to 24.88) | 0.810 | 7.056 (−13.9 to 28.0) | 0.508 | 0.687 | |||

| Active HTN | 0.005 | −15.14 (−33.56 to 3.28) | 0.107 | −4.88 (−28.7 to 18.9) | |||||

HR, heart rate; HTN, hypertension; SBP, systolic blood pressure; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Table 5.

Association of 6MW with echocardiographic measures

| r2 | β (95% CI) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| GLS* | 0.149 | −0.003 (−0.005 to 0.000) | 0.018 |

| DS* | 0.346 | 0.000 (0.000 to 0.000) | 0.009 |

| DSR* | 0.057 | 0.000 (0.000 to 0.000) | 0.967 |

| e′* | 0.116 | 0.000 (0.000 to 0.000) | 0.114 |

| E/e′* | 0.071 | 0.000 (−0.003 to 0.003) | 0.849 |

| E/A* | 0.110 | 0.000 (0.000 to 0.000) | 0.686 |

| LVMi* | 0.149 | −0.020 (−0.038 to −0.003) | 0.024 |

*Adjusted with age, gender, height, HR and SBP.

DS, diastolic strain; DSR, diastolic strain rate; GLS, global longitudinal strain; LVMi, left ventricular mass index.

Discussion

This study demonstrated that in individuals with non-ischaemic stage A HF risks, T2DM is associated with more impaired cardiac function and reduced exercise capacity than is present in those with hypertension. Although patients with well-controlled and poorly controlled BP showed abnormal diastolic function, it appears that abnormal GLS is an independent marker for diabetic cardiomyopathy rather than hypertensive heart disease. Poor BP control is associated with more impaired cardiac function with or without the presence of diabetes.

Combined effect of T2DM and hypertension on LV function

Diabetes and hypertension constitute two powerful independent risk factors for cardiovascular disease. T2DM is known to be a strong predictor of incident HF, independent of other concomitant risk factors.6 17–21 Subclinical diastolic dysfunction and systolic impairment assessed using GLS are believed to be early markers of diabetic cardiomyopathy.5 18 However, hypertension is present in 40–80% of patients with long-standing diabetes,22 and most of these studies were performed in populations with a high prevalence of hypertension and therefore reflect the combined impact of hypertension and T2DM. In our study, patients with mixed T2DM and hypertension had a 20% prevalence of E/e′>15, analogous to a 23% prevalence in another community-based study of 1760 patients with T2DM with 86% of hypertension and 36% prevalence of CAD. Follow-up of that group showed that the HR of hypertension (HR 4.27, 95% CI 1.92 to 12.15) for subsequent HF was almost double that of CAD (HR 2.2, 95% CI 1.62 to 3.01). The negative synergistic effect of hypertension and diabetes was likely the cause of high prevalence of impaired diastolic and systolic dysfunction and associated adverse outcome.6 18 23 However, the exact underlying pathophysiology of this combined impact is unclear. Diabetes is a metabolic disorder characterised by intracellular accumulation of toxic fatty acid intermediates.24 This change also affects cardiac mitochondria, resulting in contractile dysfunction.25 There is a well-recognised tendency to develop diastolic dysfunction even in the absence of significant hypertension; however, the presence of hypertension may accelerate the adverse changes and cause end-organ damage.26 Quantitative measure using fibrosis score showed the degree of myocardial and interstitial fibrosis contributes to the pathological involvement.27 The score was found to be lowest for hypertensive, midrange for diabetic and highest for hypertensive diabetic. It is presumed that fibrosis and metabolic consequences of myocyte in diabetes lead to impaired systolic and diastolic function, while chronic afterload causes interstitial fibrosis, leading to a more impaired diastolic than systolic function in hypertension. The coexisting hypertension exacerbates functional changes by producing larger amount of fibrosis. Another observation was described that abnormal GLS and diastolic dysfunction were not analogous to each other. As an early marker, diastolic function was documented in 47% of patients with T2DM, Ernande showed abnormal strain in 28% of those with normal diastolic function.5 In multivariable analysis, a history of hypertension but not T2DM was associated with diastolic parameters. This relationship was mirrored in our study, in which the prevalence of diastolic dysfunction was 72% in those with T2DM with abnormal strain in 47% of them (table 2)—a higher prevalence found in our study was likely due to older age (71±5 vs 52±5 years) and higher prevalence of history of hypertension (67% vs 38%). A history of hypertension but controlled BP was associated with increased E/e′, which may represent a combined impact. The findings parallel the finding that hypertension (either historical or high BP at the time of the echocardiogram) was independently associated with e′ and E/e′ and diabetes was associated with E/e′.23

It needs to be noted that our finding of GLS consistently associated with diabetes but not hypertension in the multivariable analysis should not be interpreted as a normal GLS in this population. Influence of afterload on LV causing reduced GLS in early disease stage was described in animal model and human studies.28–30 Understanding these differences would be important and beneficial to guide effective screening and early intervention in the community as hypertension and diabetes are the two leading aetiologies of preclinical HF in this population.

Effects of controlled and uncontrolled hypertension on LV impairment

Hypertension has been shown to precede the development of HF in men and women.31 Although there have been improvements in the overall management of hypertension, there remain a significant number of hypertensive patients who remain untreated or fail to achieve optimal control.32 33 Of the 82% with a known history of hypertension in our study, 92% were on antihypertensive therapy, but only 33% had good control of BP (table 1). Our study demonstrated uncontrolled BP was independently associated with more severe cardiac dysfunction including abnormal e′, E/e′, DS, DSR and LV mass. However, GLS appeared to be relatively preserved in those with hypertension compared with those with neither hypertension nor T2DM. These findings are inconsistent with previous work in a small group of younger (46±14 years) hypertensive patients with controlled BP showing lower peak strain and strain rate at rest, with blunting of strain increment during exercise.29 The dependence of myocardial strain on haemodynamic conditions has been reported in hypertension34 35 and valve disease.36

Assessment of exercise capacity using 6MW

Impaired exercise capacity and functional changes during exercise were known to be early markers of subclinical LV dysfunction in patients with hypertension and diabetes.37–39 However, a standard exercise testing protocol is not feasible in community-based screening for subclinical LV dysfunction. Owing to its simplicity and inexpensiveness, the 6MW test is often used to estimate submaximal functional capacity in this setting; the predictive value of 6MW for peak oxygen uptake is of moderate accuracy.40 In our study, 6MW distance correlated with subclinical cardiac dysfunction and was significantly reduced in those with T2DM+HTN+ individuals but relatively preserved in those with hypertension alone.

Limitations

The present analysis was based on a cross-sectional sample from a clinical trial population of participants aged ≥65 years with at least one of the listed non-ischaemic stage A HF risks. The control group without T2DM or hypertension had other HF risks (mainly obesity), but there were no age-matched controls without HF risk factors. Another important limitation of this study was the concomitant presence of CAD was not assessed. Our intention and focus was on non-ischaemic population with a very low prevalence of known CAD (<5%). However, diabetic cardiomyopathy and hypertensive heart disease are known as part of atherosclerosis process, which make their heart susceptible to ischaemia coronary changes. Some of the functional change may be caused by underlying ischaemic and non-ischaemic pathophysiological changes. A possible approach to address this limitation would be a stress test to identify those with underlying CAD, but we could not perform this in the context of a community-based study.

Conclusions

Hypertension is associated with less impairment of GLS and exercise capacity than is T2DM. Those with well-controlled and poorly controlled BP showed abnormal diastolic functional markers, and more severely impaired cardiac function was associated with worse BP control. However, GLS appears to be associated with diabetic cardiomyopathy rather than hypertensive heart disease in this population at risk of HF.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the contribution of our tireless volunteer coordinators, Diane Binns and Jasmine Prichard.

Footnotes

Contributors: HY designed the study, gathered and analysed the data, and wrote the first draft. YW, KN and MN assisted with gathering and analysis of the data and contributed to the revision of drafts. THM designed the study, analysed the data and edited the drafts.

Funding: This study was partially supported by Tasmanian Community Fund and Diabetes Australia Research Trust. HY is supported by a Health Professional Scholarship from the National Heart Foundation of Australia (100307).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committees of participating centres in Australia and New Zealand, and the NRES Committee East Midlands—Nottingham in the UK.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Hunt SA, Abraham WT, Chin MH et al. Focused update incorporated into the ACC/AHA 2005 guidelines for the diagnosis and management of heart failure in adults A Report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines Developed in Collaboration With the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009;53:e1–e90. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2008.11.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang H, Negishi K, Otahal P et al. Clinical prediction of incident heart failure risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Open heart 2015;2:e000222 doi:10.1136/openhrt-2014-000222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levy D, Larson MG, Vasan RS et al. The progression from hypertension to congestive heart failure. JAMA 1996;275:1557–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marwick TH. Tissue Doppler imaging for evaluation of myocardial function in patients with diabetes mellitus. Curr Opin Cardiol 2004;19:442–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ernande L, Bergerot C, Rietzschel ER et al. Diastolic dysfunction in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: is it really the first marker of iabetic cardiomyopathy? J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2011;24:1268–75.e1. doi:10.1016/j.echo.2011.07.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.From AM, Scott CG, Chen HH. The development of heart failure in patients with diabetes mellitus and pre-clinical diastolic dysfunction a population-based study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010;55:300–5. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2009.12.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Almuntaser I, Brown A, Murphy R et al. Comparison of echocardiographic measures of left ventricular diastolic function in early hypertension. Am J Cardiol 2007;100:1771–5. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.07.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bittner V, Weiner DH, Yusuf S et al. Prediction of mortality and morbidity with a 6-minute walk test in patients with left ventricular dysfunction. SOLVD Investigators. JAMA 1993;270:1702–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weiss W, Gohlisch C, Harsch-Gladisch C et al. Oscillometric estimation of central blood pressure: validation of the Mobil-O-Graph in comparison with the SphygmoCor device. Blood Press Monit 2012;17:128–31. doi:10.1097/MBP.0b013e328353ff63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pickering TG, Hall JE, Appel LJ et al. Recommendations for blood pressure measurement in humans: an AHA scientific statement from the Council on High Blood Pressure Research Professional and Public Education Subcommittee. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2005;7:102–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mancia G, Fagard R, Narkiewicz K et al. 2013 ESH/ESC practice guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. Blood Press 2014;23:3–16. doi:10.3109/08037051.2014.868629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lang RM, Badano LP, Mor-Avi V et al. Recommendations for cardiac chamber quantification by echocardiography in adults: an update from the American society of echocardiography and the European association of cardiovascular imaging. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2015;28:1–39.e14 e14 doi:10.1016/j.echo.2014.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nagueh SF, Appleton CP, Gillebert TC et al. Recommendations for the evaluation of left ventricular diastolic function by echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2009;22:107–33. doi:10.1016/j.echo.2008.11.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yingchoncharoen T, Agarwal S, Popovic ZB et al. Normal ranges of left ventricular strain: a meta-analysis. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2013;26:185–91. doi:10.1016/j.echo.2012.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ishii K, Imai M, Suyama T et al. Exercise-induced post-ischemic left ventricular delayed relaxation or diastolic stunning: is it a reliable marker in detecting coronary artery disease? J Am Coll Cardiol 2009;53:698–705. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2008.09.057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brooks D, Solway S, Gibbons WJ. ATS statement on six-minute walk test. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003;167:1287 doi:10.1164/ajrccm.167.9.950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kannel WB, McGee DL. Diabetes and cardiovascular disease. The Framingham study. JAMA 1979;241:2035–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holland DJ, Marwick TH, Haluska BA et al. Subclinical LV dysfunction and 10-year outcomes in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Heart 2015;101:1061–6. doi:10.1136/heartjnl-2014-307391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kiencke S, Handschin R, von Dahlen R et al. Pre-clinical diabetic cardiomyopathy: prevalence, screening, and outcome. Eur J Heart Fail 2010;12:951–7. doi:10.1093/eurjhf/hfq110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Simone G, Devereux RB, Roman MJ et al. Does cardiovascular phenotype explain the association between diabetes and incident heart failure? The Strong Heart Study. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2013;23:285–91. doi:10.1016/j.numecd.2011.06.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Voulgari C, Papadogiannis D, Tentolouris N. Diabetic cardiomyopathy: from the pathophysiology of the cardiac myocytes to current diagnosis and management strategies. Vasc Health Risk Manag 2010;6:883–903. doi:10.2147/VHRM.S11681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Christlieb AR. Diabetes and hypertensive vascular disease. Mechanisms and treatment. Am J Cardiol 1973;32:592–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Russo C, Jin Z, Homma S et al. Effect of diabetes and hypertension on left ventricular diastolic function in a high-risk population without evidence of heart disease. Eur J Heart Fail 2010;12:454–61. doi:10.1093/eurjhf/hfq022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rodrigues B, Cam MC, McNeill JH. Metabolic disturbances in diabetic cardiomyopathy. Mol Cell Biochem 1998;180:53–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Montaigne D, Marechal X, Coisne A et al. Myocardial contractile dysfunction is associated with impaired mitochondrial function and dynamics in type 2 diabetic but not in obese patients. Circulation 2014;130:554–64. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.008476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sowers JR, Levy J, Zemel MB. Hypertension and diabetes. Med Clin North Am 1988;72:1399–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Hoeven KH, Factor SM. A comparison of the pathological spectrum of hypertensive, diabetic, and hypertensive-diabetic heart disease. Circulation 1990;82:848–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Donal E, Bergerot C, Thibault H et al. Influence of afterload on left ventricular radial and longitudinal systolic functions: a two-dimensional strain imaging study. Eur J Echocardiogr 2009;10:914–21. doi:10.1093/ejechocard/jep095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hensel KO, Jenke A, Leischik R. Speckle-tracking and tissue-Doppler stress echocardiography in arterial hypertension: a sensitive tool for detection of subclinical LV impairment. BioMed Res Int 2014;2014:472562 doi:10.1155/2014/472562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Szelenyi Z, Fazakas A, Szenasi G et al. The mechanism of reduced longitudinal left ventricular systolic function in hypertensive patients with normal ejection fraction. J Hypertens 2015;33:1962–9. doi:10.1097/HJH.0000000000000624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meredith PA, Ostergren J. From hypertension to heart failure -- are there better primary prevention strategies? J Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone Syst 2006;7:64–73. doi:10.3317/jraas.2006.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR et al. Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Hypertension 2003;42:1206–52. doi:10.1161/01.HYP.0000107251.49515.c2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang TJ, Vasan RS. Epidemiology of uncontrolled hypertension in the United States. Circulation 2005;112:1651–62. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.490599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Celic V, Tadic M, Suzic-Lazic J et al. Two- and three-dimensional speckle tracking analysis of the relation between myocardial deformation and functional capacity in patients with systemic hypertension. Am J Cardiol 2014;113:832–9. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2013.11.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tadic M, Majstorovic A, Pencic B et al. The impact of high-normal blood pressure on left ventricular mechanics: a three-dimensional and speckle tracking echocardiography study. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 2014;30:699–711. doi:10.1007/s10554-014-0382-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mizariene V, Bucyte S, Zaliaduonyte-Peksiene D et al. Left ventricular mechanics in asymptomatic normotensive and hypertensive patients with aortic regurgitation. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2011;24:385–91. doi:10.1016/j.echo.2010.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fang ZY, Schull-Meade R, Leano R et al. Screening for heart disease in diabetic subjects. Am Heart J 2005;149:349–54. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2004.06.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kosmala W, Jellis CL, Marwick TH. Exercise limitation associated with asymptomatic left ventricular impairment: analogy with stage B heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015;65:257–66. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2014.10.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yuda S, Short L, Leano R et al. Myocardial abnormalities in hypertensive patients with normal and abnormal left ventricular filling: a study of ultrasound tissue characterization and strain. Clin Sci (Lond) 2002;103:283–93. doi:10.1042/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ingle L, Goode K, Rigby AS et al. Predicting peak oxygen uptake from 6-min walk test performance in Male patients with left ventricular systolic dysfunction. Eur J Heart Fail 2006;8:198–202. doi:10.1016/j.ejheart.2005.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]