Abstract

The microalga Emiliania huxleyi produces alkenone lipids which are important proxies for estimating past sea surface temperatures. Field calibrations of this proxy are robust but highly variable results are obtained in culture. Here we present results suggesting that algal-bacterial interactions may be responsible for some of this variability. Co-cultures of E. huxleyi and the bacterium Phaeobacter inhibens resulted in a 2.5-fold decrease in algal alkenone-containing lipid bodies. In addition levels of unsaturated alkenones increase in co-cultures. These changes result in an increase in the reconstructed growth temperature of up to 2°C relative to axenic algal cultures.

Keywords: Emiliania huxleyi, Phaeobacter inhibens, Roseobacter clade, co-culture, alkenone, biomarker, SST

The microalga Emiliania huxleyi (Lohmann) W.W.Hay & H.P.Mohler is the dominant oceanic coccolithophore and the main producer of the long chain (C37) polyunsaturated alkenones, a key ocean temperature biomarker (Okada and Honjo 1973, Okada and Honjo 1975, Okada and McIntyre 1977, Boon et al. 1978, Okada and McIntyre 1979, de Leeuw et al. 1980, Volkman et al. 1980a, Volkman et al. 1980b, Marlowe et al. 1990). The ratio of the di- to di- plus tri-unsaturated C37 methyl alkenones has been defined as the UK'37 index and was shown to vary linearly with the sea surface temperature (SST) in which the algae grow (Prahl and Wakeham 1987, Prahl et al. 1988).

Analysis of environmental samples including seawater, sediment traps and core tops have demonstrated the robustness of alkenones as a paleo-SST proxy (Prahl and Wakeham 1987, Sikes et al. 1991, Conte et al. 1992, Conte and Eglinton 1993, Sikes and Volkman 1993, Prahl et al. 1995, Rosell-Melé et al. 1995, Sikes et al. 1997, Madureira et al. 1997). However, much variation is seen in the relationship between temperature and alkenone unsaturation in laboratory cultures of E. huxleyi (Prahl and Wakeham 1987, Prahl et al. 1988, Conte et al. 1995, Prahl et al. 1995, Conte et al. 1998, Popp et al. 1998, Epstein et al. 1998, Epstein et al. 2001, Laws et al. 2001). The difference between field studies and laboratory experiments has suggested that paleo-temperature reconstructions based on UK’37 contain uncertainties that are related to factors other than temperature (Conte and Eglinton 1993, Sikes and Volkman 1993, Prahl et al. 1995, Sikes et al. 1997, Conte et al. 1998, Epstein et al. 1998, Prahl et al. 2003, Sikes et al. 2005).

Both mutualistic and antagonistic relations have been documented in various algal-bacterial interactions demonstrating that algal physiology is influenced by bacteria (Ashen et al. 1999, Brinkhoff et al. 2004, Miller and Belas 2004, Seyedsayamdost et al. 2011a, Seyedsayamdost et al. 2011b, Sule and Belas 2013, Wang et al. 2014, Amin et al. 2015). We wanted to determine if bacterial influences could account for some of the observed irregularities in UK’37 obtained in culture experiments. To this end we examined alkenones in axenic algal cultures and in cultures of the algae with the Roseobacter Phaeobacter inhibens. We chose a Roseobacter because E. huxleyi blooms contain bacterial populations, at times dominated by Roseobacters (Gonzalez et al. 2000) and P. inhibens was previously found in the bacterial assemblage associated with E. huxleyi (Green et al. 2015).

To determine if P. inhibens affected E. huxleyi alkenones, we grew them in co-culture. Axenic E. huxleyi algae (strain CCMP3266) were cultivated in L1-Si medium (see Appendix S1 in the Supporting Information; Fig. 1a). P. inhibens DSM17395 cannot grow in this medium but grows well in the rich medium 1/2YTSS (see Appendix S1; Fig. 1b). To co-cultivate algae and bacteria, a bacterial inoculum of P. inhibens was introduced into a pre-established axenic algal culture. In the resulting co-culture both algae and bacteria grew. Algae grew from 1 × 106 to 2.5 × 106 cells . mL−1 and bacteria grew from 1 × 102 to 1 × 106 colony forming units (CFU). mL−1 by 14 d in co-culture, with the bacteria attached onto the algal cells (Fig. 1c). Many members of the Roseobacter clade, including P. inhibens, are adapted to surface attachment (Dang and Lovell 2002, Bruhn et al. 2006, Frank et al. 2015).

Figure 1.

Algal-bacterial co-cultures. Phase contrast microscopy of (a) Calcified cells of E. huxleyi (CCMP3266) axenic algal culture. Arrow indicates an algal cell and asterisk a shed coccolith. (b) A pure culture of P. inhibens (DSM17395) bacteria. These bacteria tend to form multi-cellular structures called rosettes. Arrow indicates a rosette. (c) Algal-bacterial co-culture showing numerous P. inhibens bacteria surrounding an E. huxleyi algal cell which no longer bears coccoliths. Scale bars correspond to 1 μm.

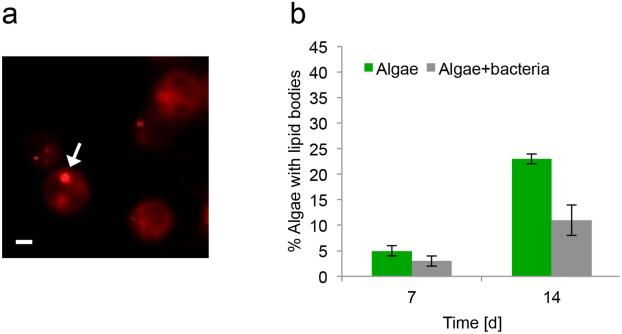

Next, we examined whether the presence of bacteria influences algal alkenones. Alkenones were suggested to be part of the algal membrane (Sawada and Shiraiwa 2004) and they can be found stored in intracellular lipid bodies (Epstein et al. 2001, Eltgroth et al. 2005). We thus tested if the presence of bacteria affected algal lipid bodies. We used Nile red to visualize algal lipid bodies (Cooksey et al. 1987) in the presence and absence of bacteria over a period of 14 d (Fig. 2a). Quantification of Nile red-stained cells revealed that in early stages about 5% of algae in both axenic culture and in co-culture harbor lipid bodies (Fig. 2b). In axenic algal cultures the percent of algae with lipid bodies steadily increased over time, with almost 25% of the population stained by day 14 (Fig. 2b). In contrast, after 14 d, only around 10% of the algae in co-culture had visible lipid bodies (Fig. 2b). These observations demonstrate a quantifiable bacterial influence on the alkenone-rich algal lipid bodies.

Figure 2.

Algal lipid bodies are influenced by the presence of bacteria. (a) Fluorescent image of algae stained with Nile red. Lipid bodies are seen as intracellular droplets. Arrow points to a lipid body. Scale bar corresponds to 1 μm. (b) Quantification of Nile red-stained algal cells containing lipid bodies in algal axenic culture (green bars) and algal-bacterial co-culture (grey bars) (see Appendix S1). For each time point n > 300 cells. Two biological replicates were examined and error bars represent the standard deviation among analyzed fields.

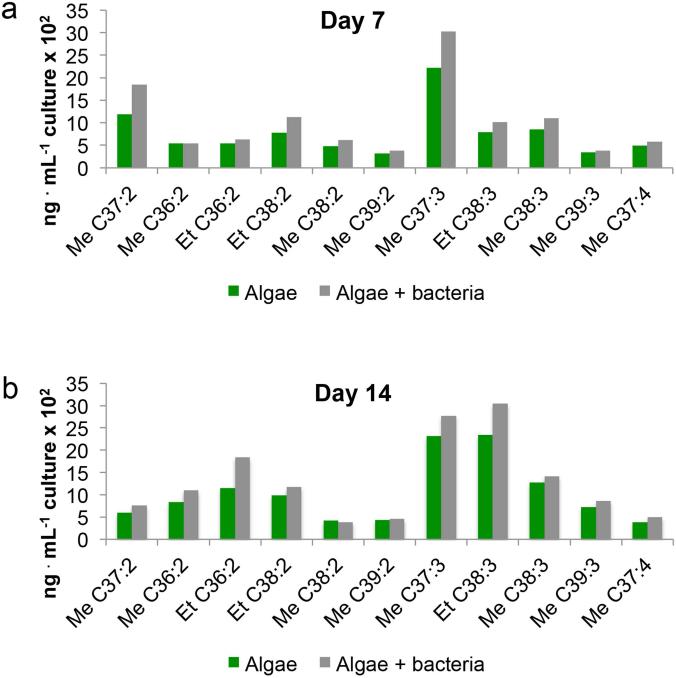

To determine if alkenone distribution was altered by the presence of bacteria, we analyzed the profile of unsaturated alkenones in axenic algal cultures and co-cultures. We extracted total alkenones from 7- and 14-d-old cultures and determined their alkenone profile (see Appendix S1). A pure P. inhibens bacterial culture was processed identically as a negative control and yielded no measurable alkenones. Despite the fact that all algal populations were grown under otherwise identical conditions, we found that in the presence of bacteria, algae were enriched with unsaturated alkenones (Fig. 3, a and b and Fig. S1 in the Supporting Information). The largest enrichment was observed for Me C37:2 alkenones which exhibited over 60% increase in the presence of bacteria at day 7 of incubation (Table 1 and Fig. 3a).

Figure 3.

Bacteria influence algal alkenones. Abundance of algal unsaturated alkenones in the presence (grey bars) and absence (green bars) of bacteria at days 7 (a) and 14 (b). Shown is the abundance of methyl (Me) and ethyl (Et) alkenones (and alkenoates, in the case of C36:2 molecules) with 36 to 39 carbon chains containing two, three, and four double bonds (designated 2, 3 and 4 respectively). In the presence of bacteria all unsaturated forms of alkenones demonstrate higher abundance than in algal pure cultures. For each dataset, two biological replicates were tested and yielded similar results, shown is one representative replicate (data for a second replicate are shown in Fig. S1).

Table 1.

Calculation of UK’37 and the growth temperature of algal cultures and co-cultures.

| Day 7 | Day 14 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pure algal culture |

Co-culture | Pure algal culture |

Co-culture | |

| Me C37:2

[ng · mL−1 culture × 102] |

11.0 | 18.5 | 5.5 | 8.0 |

| Me C37:3

[ng · mL−1 culture × 102] |

23.0 | 30.0 | 23.0 | 27.5 |

| UK’37 | 0.32 | 0.38 | 0.19 | 0.22 |

| Calculated temperature [C] |

8.2 | 10.0 | 4.4 | 5.3 |

The alkenone composition was determined and the UK’37 and growth temperature were calculated (see Appendix S1, Table 1 and Table S1 in the Supporting Information). The resulting temperature estimates deviated substantially from the growth temperature of our experiments. Although all cultures were grown at 18°C, the calculated temperatures were 8.2°C and 10.0°C at day 7 of incubation for the pure algal cultures and the co-cultures, respectively. Large differences between calculated temperatures and actual growth temperatures have been reported for culture experiments, (e.g., Conte et al. 1995, Popp et al. 1998; select studies summarized in Table S2 in the Supporting Information). Together with our data, these studies underscore the problem of reproducing the original UK’37 calibration in cultures (Prahl and Wakeham 1987).

Our data show that the 14-d-old cultures, in which both algal and bacterial populations were denser, yielded even lower UK’37 and consequently lower calculated temperature values relative to the 7-d-old cultures (Table 1 and Fig. 3). These observations are in agreement with previous work by Conte and colleagues (Conte et al. 1997) in which the majority of stationary phase cultures yielded lower UK’37 in comparison to values obtained for exponential phase cultures. Chivall and colleagues also documented a marked impact of growth phase on alkenone distribution (Chivall et al. 2014). At both time points examined in our study, the UK’37 values for the co-cultures were higher than the pure algal cultures. The presence of bacteria consequently brought the calculated UK’37 temperature closer to the actual growth temperature. Of note, algal-bacterial interactions can influence the density of both populations (e.g., Wang et al. 2014); therefore, all data in the current study were normalized in order to account for possible differences in cell density (see sections regarding alkenones and lipid bodies in in Appendix S1).

Since the cellular function of alkenones is unknown, it is difficult to interpret why a decrease in lipid body content was associated with an increase in alkenone abundance. Interestingly, abundant small-sized bodies (less than 100 nm in diameter) were previously reported to be in association with the chloroplasts in E. huxleyi (Eltgroth et al. 2005). In that study, lipid analysis of the chloroplast cell fraction revealed comparable amounts of alkenones in chloroplasts as in lipid bodies (Eltgroth et al. 2005). In light of these observations it is possible that the decrease we observed in Nile-red stained lipid bodies is not indicative of the overall status of the cellular alkenone reservoir. It would be fascinating to further explore the bacterial influence on alkenones in different sub-cellular locations.

Bacteria have been shown to play a key role in alkenone geochemistry in early diagenetic processes (Rontani et al. 2013). Previous studies demonstrated the capability of bacteria to degrade alkenones in dead algae under oxic and anoxic conditions (Teece et al. 1998, Rontani et al. 2005). Several studies have shown selective degradation of the more unsaturated alkenones that resulted in a bias towards warmer calculated temperatures (Rontani et al. 2008, Prahl et al. 2010, Zabeti et al. 2010). While these previous studies focused on degradative processes carried out by bacteria after algal death when alkenones have become part of the ocean’s detrital organic matter, our data are the first to reveal modifications during biosynthesis. Thus our observations demonstrate the importance of microbial interactions during the initial production of unsaturated alkenones throughout the life of the algae.

While alkenone unsaturation is a powerful paleo-oceanographic tool, our observations introduce microbial interactions as a novel factor that may affect the biosynthesis of alkenones and thus has implications for the interpretation of Uk’37 temperature reconstructions. Several previous studies have elucidated environmental and physiological factors that affect E. huxleyi-derived organic biomarkers (Conte et al. 1998, Epstein et al. 1998, Popp et al. 1998, Yamamoto et al. 2000, Epstein et al. 2001, Laws et al. 2001, Pan and Sun 2011). Laboratory analyses utilizing the original Uk’37 calibration (Prahl and Wakeham 1987) result in considerable deviations between the calculated and measured temperature in culture (Conte et al. 1995, Conte et al. 1998, Popp et al. 1998, Pan and Sun 2011; see Table S2). This contrasts with field studies, which show a much tighter fit to the accepted calibration (Prahl and Wakeham 1987, Sikes et al. 1991, Conte et al. 1992, Conte and Eglinton 1993, Sikes and Volkman 1993, Prahl et al. 1995, Rosell-Melé et al. 1995, Sikes et al. 1997, Madureira et al. 1997). Our results demonstrate that the deviations in culture may be in part attributed to the presence or absence of bacteria. Therefore, culture-based analyses should assess the bacterial population and maintain a reproducible bacterial assemblage. Of note, differences between model algal strains that have been cultivated in laboratories for many years and their relatives in the wild should also be accounted for prior to comparing laboratory results to environmental samples. In light of our findings, mesocosm experiments in which the natural algal strains and their bacterial assemblage are present might offer a more robust experimental set up. Indeed, a previous mesocosm study conducted by Conte et al. (Conte et al. 1994) showed a linear correlation between growth temperature and alkenone unsaturation in temperatures higher than 9°C using the UK37 index. Thus, algal-bacterial interactions should be considered a significant influence on algal derived biomarkers.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all members of the Kolter lab for valuable discussions and assistance. We are thankful to Natasha Barteneva for assistance with flow cytometry. This study was supported by fellowships from the European Molecular Biology Organization and from the Human Frontier Science Program granted to E.S., and NIH grants GM58213 and GM82137 to R.K.

Abbreviations

- SST

sea surface temperature

- CFU

colony forming units

- Me

methyl

- Et

ethyl

Footnotes

Submitted: July 20, 2015

Contributor Information

Einat Segev, Department of Microbiology and Immunobiology, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, USA. 02115.

Isla S. Castañeda, Department of Geosciences, University of Massachusetts Amherst, Amherst, Massachusetts, USA. 01003

Elisabeth L. Sikes, Department of Marine and Coastal Sciences, Rutgers the State University of New Jersey, New Brunswick, New Jersey, USA. 08901

Hera Vlamakis, Department of Microbiology and Immunobiology, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA. 02115.

Roberto Kolter, Department of Microbiology and Immunobiology, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA. 02115.

References

- Amin SA, Hmelo LR, van Tol HM, Durham BP, Carlson LT, Heal KR, Morales RL, Berthiaume CT, Parker MS, Djunaedi B, Ingalls AE, Parsek MR, Moran MA, Armbrust EV. Interaction and signalling between a cosmopolitan phytoplankton and associated bacteria. Nature. 2015;522:98–101. doi: 10.1038/nature14488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashen JB, Cohen JD, Goff LJ. GC-SIM-MS detection and quantification of free indole-3-acetic acid in bacterial galls on marine alga Prionitis lanceolata (Rhodophyta) J. Phycol. 1999;35:493–500. [Google Scholar]

- Boon JJ, Meer F. W. V. d., Schuyl PWJ, Leeuw JWD, Schenck PA. Organic geochemical analysis of core samples from site 362, Walvis Ridge, DSDP Leg 40. Initial Rep. Deep Sea Drill. Proj. 1978;40:627–637. [Google Scholar]

- Brinkhoff T, Bach G, Heidorn T, Liang L, Schlingloff A, Simon M. Antibiotic production by a Roseobacter clade-affiliated species from the German Wadden Sea and its antagonistic effects on indigenous isolates. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2004;70:2560–2565. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.4.2560-2565.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruhn JB, Haagensen JAJ, Bagge-Ravn D, Gram L. Culture conditions of Roseobacter strain 27-4 affect its attachment and biofilm formation as quantified by real-time PCR. App. Environ. Microbiol. 2006;72:3011–3015. doi: 10.1128/AEM.72.4.3011-3015.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chivall D, M'Boule D, Sinke-Schoen D, Damste JSS, Schouten S, van der Meer MTJ. Impact of salinity and growth phase on alkenone distributions in coastal haptophytes. Organic Geochem. 2014;67:31–34. [Google Scholar]

- Conte MH, Eglinton G. Alkenone and alkenoate distributions within the euphotic zone of the eastern north-atlantic - correlation with production temperature. Deep-Sea Res. Part I. 1993;40:1935–1961. [Google Scholar]

- Conte MH, Eglinton G, Madureira LAS. Long-chain alkenones and alkyl alkenoates as palaeotemperature indicators: their production, flux and early sedimentary diagenesis in the Eastern North Atlantic. Org. Geochem. 1992;19:287–298. [Google Scholar]

- Conte MH, Thompson A, Eglinton G. Primary production of lipid biomarker compounds by Emiliania huxleyi - results from an experimental mesocosm study in fjords of southwestern Norway. Sarsia. 1994;79:319–331. [Google Scholar]

- Conte MH, Thompson A, Eglinton G, Green JC. Lipid biomarker diversity in the coccolithophorid Emiliania huxleyi (Prymnesiophyceae) and the related species Gephyrocapsa oceanica. J. Phycol. 1995;31:272–282. [Google Scholar]

- Conte MH, Thompson A, Lesley D, Harris RP. Genetic and physiological influences on the alkenone/alkenoate versus growth temperature relationship in Emiliania huxleyi and Gephyrocapsa oceanica. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 1998;62:51–68. [Google Scholar]

- Cooksey KE, Guckert JB, Williams SA, Callis PR. Fluorometric determination of the neutral lipid content of microalgal cells using Nile Red. J. Microbiol. Meth. 1987;6:333–345. [Google Scholar]

- Dang HY, Lovell CR. Numerical dominance and phylotype diversity of marine Rhodobacter species during early colonization of submerged surfaces in coastal marine waters as determined by 16S ribosomal DNA sequence analysis and fluorescence in situ hybridization. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2002;68:496–504. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.2.496-504.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Leeuw JW, Van der Meer FW, Rijpstra WIC, Schenck PA. On the occurrence and structural identification of long chain unsaturated ketones and hydrocarbons in sediments. In: Douglas AG, Maxwell JR, editors. Advances in Organic Geochemistry. Pergamon, Tarrytown; New York: 1980. pp. 211–217. [Google Scholar]

- Eltgroth ML, Watwood RL, Wolfe GV. Production and cellular localization of neutral long-chain lipids in the haptophyte algae Isochrysis galbana and Emiliania huxleyi. J. Phycol. 2005;41:1000–1009. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein BL, D'Hondt S, Hargraves PE. The possible metabolic role of C37 alkenones in Emiliania huxleyi. Org. Geochem. 2001;32:867–875. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein BL, D'Hondt S, Quinn JG, Zhang JP, Hargraves PE. An effect of dissolved nutrient concentrations on alkenone-based temperature estimates. Paleoceanography. 1998;13:122–126. [Google Scholar]

- Frank O, Michael V, Pauker O, Boedeker C, Jogler C, Rohde M, Petersen J. Plasmid curing and the loss of grip - The 65-kb replicon of Phaeobacter inhibens DSM 17395 is required for biofilm formation, motility and the colonization of marine algae. Sys. App. Microbiol. 2015;38:120–127. doi: 10.1016/j.syapm.2014.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez JM, Simo R, Massana R, Covert JS, Casamayor EO, Pedros-Alio C, Moran MA. Bacterial community structure associated with a dimethylsulfoniopropionate-producing North Atlantic algal bloom. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2000;66:4237–4246. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.10.4237-4246.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green DH, Echavarri-Bravo V, Brennan D, Hart MC. Bacterial diversity associated with the coccolithophorid algae Emiliania huxleyi and Coccolithus pelagicus f. braarudii. Biomed. Res. International. 2015 doi: 10.1155/2015/194540. DOI 10.1155/2015/194540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laws EA, Popp BN, Bidigare RR, Riesbell U, Burkhardt S, Wakeham SG. Controls on the molecular distribution and carbon isotopic composition of alkenones in certain haptophyte algae. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 2001;2 Paper number 2000GC000057. [Google Scholar]

- Madureira LAS, vanKreveld SA, Eglinton G, Conte M, Ganssen G, vanHinte JE, Ottens JJ. Late Quaternary high-resolution biomarker and other sedimentary climate proxies in a northeast Atlantic core. Paleoceanography. 1997;12:255–269. [Google Scholar]

- Marlowe IT, Brassell SC, Eglinton G, Green JC. Long-chain alkenones and alkyl alkenoates and the fossil coccolith record of marine sediments. Chem. Geol. 1990;88:349–375. [Google Scholar]

- Miller TR, Belas R. Dimethylsulfoniopropionate metabolism by Pfiesteria-associated Roseobacter spp. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2004;70:3383–3391. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.6.3383-3391.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada H, Honjo S. The distributions of oceanic coccolithophorids in the Pacific. Deep Sea Res. 1973;20:355–374. [Google Scholar]

- Okada H, Honjo S. Distribution of coccolilhophores in marginal seas along the western Pacific Ocean and in the Red Sea. Mar. Biol. 1975;31:271–285. [Google Scholar]

- Okada H, McIntyre A. Modern coccolithophores of the Pacific and North Atlantic Ocean. Micropaleontology. 1977;23:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Okada H, McIntyre A. Seasonal distribution of modern coccolithophores in the western North Atlantic Ocean. Mar. Biol. 1979;54:319–328. [Google Scholar]

- Pan H, Sun MY. Variations of alkenone based paleotemperature index (Uk'37) during Emiliania huxleyi cell growth, respiration (auto-metabolism) and microbial degradation. Org. Geochem. 2011;42:678–687. [Google Scholar]

- Popp BN, Kenig F, Wakeham SG, Laws EA, Bidigare RR. Does growth rate affect ketone unsaturation and intracellular carbon isotopic variability in Emiliania huxleyi? Paleoceanography. 1998;13:35–41. [Google Scholar]

- Prahl FG, Muehlhausen LA, Zahnle DL. Further evaluation of long-chain alkenones as indicators of paleoceanographic conditions. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 1988;52:2303–2310. [Google Scholar]

- Prahl FG, Pisias N, Sparrow MA, Sabin A. Assessment of sea-surface temperature at 42-degrees-N in the California current over the last 30,000 Years. Paleoceanography. 1995;10:763–773. [Google Scholar]

- Prahl FG, Rontani JF, Zabeti N, Walinsky SE, Sparrow MA. Systematic pattern in Uk'37 - Temperature residuals for surface sediments from high latitude and other oceanographic settings. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 2010;74:131–143. [Google Scholar]

- Prahl FG, Wakeham SG. Calibration of unsaturation patterns in long-chain ketone compositions for palaeotemperature assessment. Nature. 1987;330:367–369. [Google Scholar]

- Prahl FG, Wolfe GV, Sparrow MA. Physiological impacts on alkenone paleothermometry. Paleoceanography. 2003;18 DOI 10.1029/2002PA000803. [Google Scholar]

- Rontani JF, Bonin P, Jameson I, Volkman JK. Degradation of alkenones and related compounds during oxic and anoxic incubation of the marine haptophyte Emiliania huxleyi with bacterial consortia isolated from microbial mats from the Camargue, France. Org. Geochem. 2005;36:603–618. [Google Scholar]

- Rontani JF, Harji R, Guasco S, Prahl FG, Volkman JK, Bhosle NB, Bonin P. Degradation of alkenones by aerobic heterotrophic bacteria: Selective or not? Org. Geochem. 2008;39:34–51. [Google Scholar]

- Rontani JF, Volkman JK, Prahl FG, Wakeham SG. Biotic and abiotic degradation of alkenones and implications for Uk'37 paleoproxy applications: A review. Org. Geochem. 2013;59:95–113. [Google Scholar]

- Rosell-Melé A, Eglinton G, Pflaumann U, Sarnthein M. Atlantic core-top calibration of the Uk'37 index as a sea-surface paleotemperature indicator. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 1995;59:3099–3107. [Google Scholar]

- Sawada K, Shiraiwa Y. Alkenone and alkenoic acid compositions of the membrane fractions of Emiliania huxleyi. Phytochemistry. 2004;65:1299–1307. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2004.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seyedsayamdost MR, Carr G, Kolter R, Clardy J. Roseobacticides: small molecule modulators of an algal-bacterial symbiosis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011a;133:18343–18349. doi: 10.1021/ja207172s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seyedsayamdost MR, Case RJ, Kolter R, Clardy J. The Jekyll-and-Hyde chemistry of Phaeobacter gallaeciensis. Nat. Chem. 2011b;3:331–335. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikes EL, Farrington JW, Keigwin LD. Use of the alkenone unsaturation ratio UK37 to determine past sea surface temperatures: Coretop SST calibrations and methodology considerations. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 1991;104:36–47. [Google Scholar]

- Sikes EL, O'Leary T, Nodder SD, Volkman JK. Alkenone temperature records and biomarker flux at the subtropical front on the chatham rise, SW Pacific Ocean. Deep-Sea Res. Part I. 2005;52:721–748. [Google Scholar]

- Sikes EL, Volkman JK. Calibration of alkenone unsaturation ratios (Uk'37) for paleotemperature estimation in cold polar waters. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 1993;57:1883–1889. [Google Scholar]

- Sikes EL, Volkman JK, Robertson LG, Pichon JJ. Alkenones and alkenes in surface waters and sediments of the Southern Ocean: Implications for paleotemperature estimation in polar regions. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 1997;61:1495–1505. [Google Scholar]

- Sule P, Belas R. A novel inducer of Roseobacter motility is also a disruptor of algal symbiosis. J. Bact. 2013;195:637–646. doi: 10.1128/JB.01777-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teece MA, Getliff JM, Leftley JW, Parkes RJ, Maxwell JR. Microbial degradation of the marine prymnesiophyte Emiliania huxleyi under oxic and anoxic conditions as a model for early diagenesis: long chain alkadienes, alkenones and alkyl alkenoates. Org. Geochem. 1998;29:863–880. [Google Scholar]

- Volkman JK, Eglinton G, Corner EDS, Forsberg TEV. Long chain alkenes and alkenones in the marine coccolithophorid Emiliania huxleyi. Phytochemistry. 1980a;19:2619–2622. [Google Scholar]

- Volkman JK, Eglinton G, Corner EDS, Sargent JR. Novel unsaturated straight chain C37- C39 methyl and ethyl ketones in marine sediments and a coccolithophore Emiliania huxleyi. In: Douglas AG, Maxwell JR, editors. Advances in Organic Geochemistry. Pergamon Press; Oxford: 1980b. pp. 219–228. [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Tomasch J, Jarek M, Wagner-Dobler I. A dual-species co-cultivation system to study the interactions between Roseobacters and dinoflagellates. Front. Microbiol. 2014;5:311. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto M, Shiraiwa Y, Inouye I. Physiological responses of lipids in Emiliania huxleyi and Gephyrocapsa oceanica (Haptophyceae) to growth status and their implications for alkenone paleothermometry. Org. Geochem. 2000;31:799–811. [Google Scholar]

- Zabeti N, Bonin P, Volkman JK, Jameson ID, Guasco S, Rontani JF. Potential alteration of Uk'37 paleothermometer due to selective degradation of alkenones by marine bacteria isolated from the haptophyte Emiliania huxleyi. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2010;73:83–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2010.00885.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.