Abstract

Background:

Claudin-5, claudin-9, and claudin-11 are expressed in endothelial cells to constitute tight junctions, and their deficiency may lead to hyperpermeability, which is the initiating process and pathological basis of cardiovascular disease. Although tongxinluo (TXL) has satisfactory antianginal effects, whether and how it modulates claudin-5, claudin-9, and claudin-11 in hypoxia-stimulated human cardiac microvascular endothelial cells (HCMECs) have not been reported.

Methods:

In this study, HCMECs were stimulated with CoCl2 to mimic hypoxia and treated with TXL. First, the messenger RNA (mRNA) expression of claudin-5, claudin-9, and claudin-11 was confirmed. Then, the protein content and distribution of claudin-9, as well as cell morphological changes were evaluated after TXL treatment. Furthermore, the distribution and content histone H3K9 acetylation (H3K9ac) in the claudin-9 gene promoter, which guarantees transcriptional activation, were examined to explore the underlying mechanism, by which TXL up-regulates claudin-9 in hypoxia-stimulated HCMECs.

Results:

We found that hypoxia-suppressed claudin-9 gene expression in HCMECs (F = 7.244; P = 0.011) and the hypoxia-suppressed claudin-9 could be reversed by TXL (F = 61.911; P = 0.000), which was verified by its protein content changes (F = 29.142; P = 0.000). Moreover, high-dose TXL promoted the cytomembrane localization of claudin-9 in hypoxia-stimulated HCMECs, with attenuation of cell injury. Furthermore, high-dose TXL elevated the hypoxia-inhibited H3K9ac in the claudin-9 gene promoter (F = 37.766; P = 0.000), activating claudin-9 transcription.

Conclusions:

The results manifested that TXL reversed the hypoxia-suppressed claudin-9 by elevating H3K9ac in its gene promoter, playing protective roles in HCMECs.

Keywords: Cardiac Microvascular Endothelial Cells, Claudin-9, H3K9 Acetylation, Hypoxia, Tongxinluo

INTRODUCTION

Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death worldwide, and atherosclerosis and the subsequent vessel obliterations are the primary cause of ischemic disease.[1,2] Microvascular endothelial dysfunction is accepted as the initiating process and pathological basis of cardiovascular disease.[3,4,5]

Endothelial barrier dysfunction, especially loosened intercellular junction may result in hypernomic permeability and the subsequent pathological processes.[6] Tight junctions are the major control points of microvascular permeability and fulfill a central role in ensuring isolation function.[7,8] The claudin family contains more than twenty subtypes, which are critical components of the formation and function of tight junctions.[9] Claudin-5 is generally believed to be the main claudin subtype in endothelial cells, and it plays a crucial role in the endothelial barrier.[10,11] Claudin-9 and claudin-11 have also been reported to be expressed in endothelial cells, and function as important tight junction proteins.[12,13] Hypoxia has been found to disrupt tight junction complexes, especially claudin-5, causing cerebral endothelial barrier dysfunction.[14,15] However, whether hypoxia-suppresses claudin-5, claudin-9, and claudin-11 in cardiac microvascular endothelial cells are unclear.

Tongxinluo (TXL) was registered in the China State Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of angina pectoris in 1996. It is extracted, concentrated, and freeze-dried from a group of herbal medicines, such as ginseng, radix paeoniae rubra, borneol, and spiny jujube seed, which contains multiple active components that may be responsible for its antianginal effects.[16,17,18] However, the protective mechanism of TXL has not been clarified.[19,20] Furthermore, we have found that the effect of TXL is on microvascular endothelial cells.[21,22,23] Although TXL has been reported to have positive effects on the hypoxia-inhibited claudin-1,[24,25] whether TXL regulates claudin-5, claudin-9, and claudin-11, which are expressed in the endothelial cells, has not been explored. Moreover, histone acetylation guarantees of gene transcriptional activation, and histone H3K9 acetylation (H3K9ac) may play a more important role in the gene transactivation in the heart.[26,27] However, there is no report about the effect of TXL on H3K9ac.

Human cardiac microvascular endothelial cells (HCMECs) were adopted in this study. To investigate whether TXL modulate claudin-9 and attenuate cell injury in hypoxia, the cells were exposed to hypoxia and treated with TXL and then the messenger RNA (mRNA) expression of claudin-5, claudin-9, and claudin-11 was examined by real-time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), the claudin-9 protein content was evaluated by western blotting, the claudin-9 distribution was evaluated by immunofluorescence, and cell morphological changes were observed in light microscope. Furthermore, to reveal the mechanism by which TXL up-regulates the hypoxia-suppressed claudin-9 in HCMECs, the H3K9ac distribution was evaluated by immunofluorescence, and the H3K9ac content in the claudin-9 gene promoter was examined by a DNA pull-down assay.

METHODS

Cells and treatment

HCMECs were purchased from ScienCell and cultured in Endothelial Cell Medium (ScienCell, Carlsbad, USA). After the cells had been treated with CoCl2 (dissolved in phosphate buffered saline [PBS] to a final concentration of 100 μmol/L) to mimic hypoxia,[28] the gene expression of claudin-5, claudin-9, and claudin-11was examined at different time points to verify the optimal hypoxia-stimulation time. Then, the cells were divided into control (Con), hypoxia (Hx), hypoxia plus low-dose TXL (200 μg/ml), hypoxia plus middle-dose TXL (400 μg/ml), hypoxia plus high-dose TXL (600 μg/ml), and high-dose TXL groups. After the hypoxia-stimulated cells were treated with TXL for 24 h, the mRNA expression of claudin-5, claudin-9, and claudin-11 was measured. The claudin-9 protein content was measured after 24 h of TXL treatment, and its distribution as well as cell morphological changes was illustrated for 24 h of high-dose TXL treatment. The overall H3K9ac distribution and the content of H3K9ac in the claudin-9 gene promoter were also detected after high-dose TXL treatment for 24 h. TXL was provided by Yiling Medical Research Institution of Hebei.

Real-time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction

The mRNA expression of claudin-5, claudin-9, and claudin-11 was quantified by real-time RT-PCR. Total RNA was isolated using Trizol reagent (Takara) and reverse transcribed into complementary DNA (cDNA) using RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Fermentas, Shanghai, China), followed by real-time PCR amplification using specific primers [Table 1]. Actin primers were used as an internal standard.

Table 1.

Primers used for real-time PCR detection

| Items | Primers (5’–3’) | Annealing temperature (°C) | Product size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Claudin-5 | |||

| Sense | CTGGTTCGCCAACATTGTCGTC | 60 | 239 |

| Anti-sense | AGTTCTTCTTGTCGTAGTCGCCG | ||

| Claudin-9 | |||

| Sense | AGACACACCCTCTGAGTCACCTAGG | 55 | 183 |

| Anti-sense | ACGATGCTGTTGCCGATGAAG | ||

| Claudin-11 | |||

| Sense | GGTCTCGAACTCCTGGACTCAAAG | 60 | 232 |

| Anti-sense | CGTTCCACTATTGCCCTCCCTC | ||

| β-actin | |||

| Sense | CTCCATCCTGGCCTCGCTGT | 60 | 268 |

| Anti-sense | GCTGTCACCTTCACCGTTCC |

PCR: Polymerase chain reaction.

Western blotting

Claudin-9 protein content was detected by western blotting, using a previously described protocol.[29] Briefly, cells were lysed in lysis buffer (RIPA, Solarbio, Beijing, China) to extract whole proteins. Protein content was determined by NanoDrop-1000 (Thermo Scientific, Shanghai, China). Then, samples were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane (Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany). After the membrane was blocked with milk, anti-claudin-9 (Santa Cruz, Texas, USA) or anti-beta actin (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China) was used. Band intensity was quantified and calculated.

Immunofluorescence

The distribution of claudin-9 and H3K9ac was measured by immunofluorescence using a procedure previously reported.[30] The primary antibody used was an anti-claudin-9 or anti-H3K9ac antibody and the corresponding secondary antibody was conjugated to fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC; Zhongshan, Beijing, China). The fluorescent dye Dil was used for cytomembrane staining and 4’, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole was used for nucleus staining. The images were taken at the same intervals with a laser confocal scanning microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). To get exact results, controls (PBS instead of the first antibody or the second antibody) were designed.

DNA pull-down assay

The protein content of H3K9ac in the claudin-9 gene promoter was measured by a DNA pull-down assay, as previously reported.[29] Briefly, nuclear proteins were extracted, and DNA affinity precipitation assay was performed. The − 40 bp sequence upstream of the claudin-9 (Gene ID: 9080) gene promoter was found. The following oligonucleotides containing biotin on the 5’-end of each strand were used: biotin-5’-GGGAGCTAGCGGGGCCACTGGGCTGAGACGGGGGATGGAT-3’ (forward) and biotin-5’-ATCCATCCCCCGTCTCAGCCCAGTGGCCCCGCTAGCTCCC-3’ (reverse). Each pair of oligonucleotides was annealed following standard protocols. Nuclear protein extracts were precleared with ImmunoPure streptavidin-agarose beads (Thermo, Shanghai, China), and the supernatant was incubated with 4 μg of biotinylated double-stranded oligonucleotides. Twenty microliters of streptavidin-agarose beads were added and the protein-DNA-streptavidin-agarose complex was washed, separated, and subjected to western blotting with anti-H3K9ac (Cell Signaling Technology, Shanghai, China) and anti-histone H3 (Cell Signaling Technology) antibodies.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis of the data was performed using SPSS 17.0 software (Chicago, IL, USA). The experiments were repeated 3 times and presented as a mean ± standard deviation (SD). One-way analysis of variances (ANOVA) was used to analyze the differences among the groups, and the differences between two groups were evaluated by the least-significant difference. A P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Tongxinluo reversed the hypoxia-suppressed claudin-9 gene expression

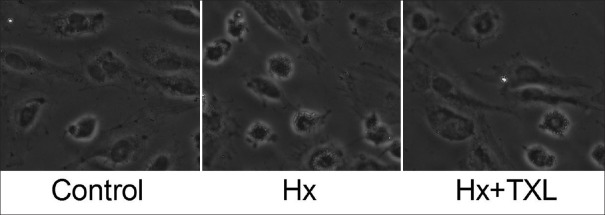

First, we analyzed claudins by the BioGPS and found that claudin-5, claudin-9, and claudin-11 are highly expressed in the heart. Then, after the cells were stimulated by hypoxia for different periods of time, the gene expression of claudin-5, claudin-9, and claudin-11 was examined by real-time RT-PCR [Figure 1a]. Although the expression of claudin-5 and claudin-11 showed no significant changes, claudin-9 gene expression decreased at 24 h and 48 h hypoxia treatments (F = 7.244; P = 0.011). Then, the hypoxia-stimulated cells were treated with TXL for 24 h, and the gene expression of claudin-5, claudin-9, and claudin-11 was detected by real-time RT-PCR [Figure 1b]. The hypoxia-suppressed claudin-9 gene expression was up-regulated by middle-dose and high-dose TXL treatments (F = 61.911; P = 0.000). However, claudin-5 and claudin-11 hardly changed after TXL treatment. In addition, high-dose TXL itself had no obvious effect on the gene expressions of claudin-5, claudin-9, and claudin-11. The results showed that TXL, especially in a high-dose, reversed the hypoxia-suppressed claudin-9 expression in HCMECs.

Figure 1.

Tongxinluo reversed the Hx-suppressed claudin-9 gene expression. The gene expressions were detected by real-time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction. (a) Hx suppressed claudin-9, without significant effects on claudin-5 and claudin-11. *P < 0.05, compared with 0 h group. (b) Tongxinluo significantly increased the Hx-suppressed claudin-9. *P < 0.05, compared with Con group. †P < 0.01, compared with Hx group. The data were repeated 3 times and presented as a mean ± standard deviation. LT: Low-dose tongxinluo; MT: Middle-dose tongxinluo; HT: High-dose tongxinluo; Con: Control; Hx: Hypoxia.

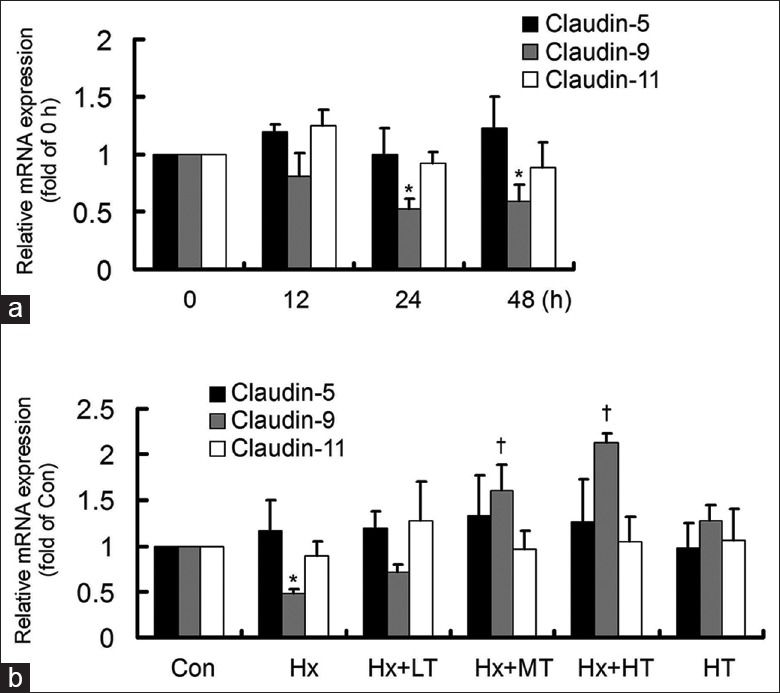

Tongxinluo up-regulated claudin-9 protein content

The hypoxia-stimulated cells were treated with low, middle, or high-dose TXL for 24 h, and then claudin-9 protein content was examined by western blotting [Figure 2]. Although hypoxia significantly suppressed claudin-9 protein content, TXL reversed the hypoxia-suppressed claudin-9 protein content in a concentration-dependent manner (F = 29.142; P = 0.000). The changes in claudin-9 protein content were in accordance with those of the mRNA expression, confirming that TXL up-regulated on the hypoxia-suppressed claudin-9 expression in HCMECs.

Figure 2.

Tongxinluo up-regulated the Hx-suppressed claudin-9 protein content. (a) The claudin-9 protein content was detected by western blotting. (b) Tongxinluo up-regulated the Hx-suppressed claudin-9 protein content in a concentration-dependent manner. *P < 0.05, compared with Con group; †P < 0.01, compared with Hx group. The data were repeated 3 times and presented as a mean ± standard deviation. LT: Low-dose tongxinluo; MT: Middle-dose tongxinluo; HT: High-dose tongxinluo; Con: Control; Hx: Hypoxia.

Tongxinluo promoted the cytomembrane localization of claudin-9

After the cells had been treated with high-dose TXL, the claudin-9 distribution was evaluated by immunofluorescence [Figure 3]. As illustrated, claudin-9 was obvious and localized in the cytomembrane in the control group but was hardly seen in hypoxia-treated HCMECs. However, the hypoxia-suppressed claudin-9 was overt and conspicuously localized in the cytomembrane after TXL treatment. The results showed that besides up-regulating it, TXL promoted the cytomembrane localization of claudin-9.

Figure 3.

TXL promoted claudin-9 content and its cytomembrane localization (original magnification ×400). Compared with the control group, claudin-9 was hardly seen in Hx group. TXL dramatically increased claudin-9 content and obviously promoted its cytomembrane localization. 4’, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole was used for nucleus staining and Dil for cytomembrane staining. Hx: Hypoxia; TXL: Tongxinluo.

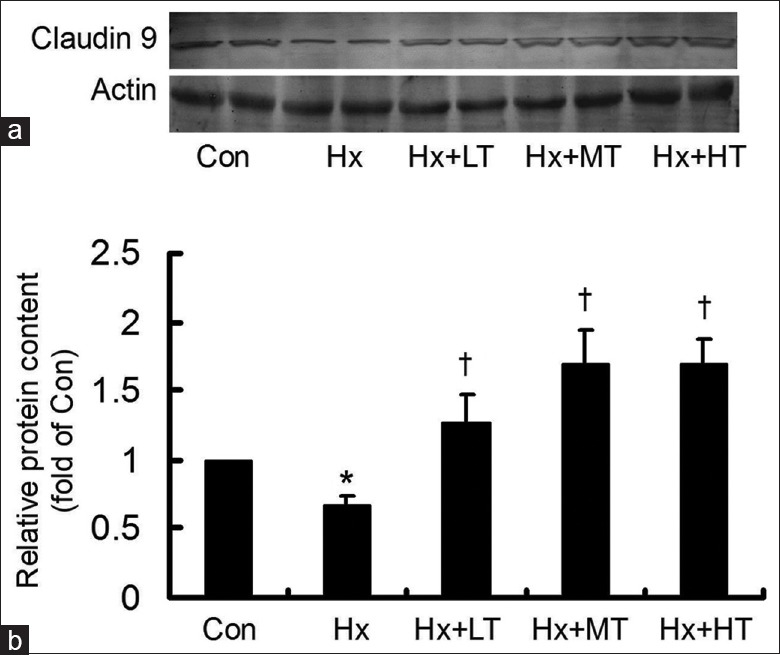

Tongxinluo attenuated the hypoxia-induced human cardiac microvascular endothelial cell injury

After the cells had been treated with high-dose TXL for 24 h, the cell morphological changes were observed under a light microscope [Figure 4]. In contrast to the control group, the cells shrank, turned round, and seemed to detach and die in Hx group. However, the morphological cell injury was overtly attenuated by TXL treatment. The results indicated that TXL attenuated cell injury, playing protective roles in hypoxia-stimulated HCMECs.

Figure 4.

TXL attenuated the hypoxia-stimulated human cardiac microvascular endothelial cell injury (original magnification ×200). The cells shrank, turned round, and seemed to detach and die in Hx group, which was clearly attenuated by TXL treatment. Hx: Hypoxia; TXL: Tongxinluo.

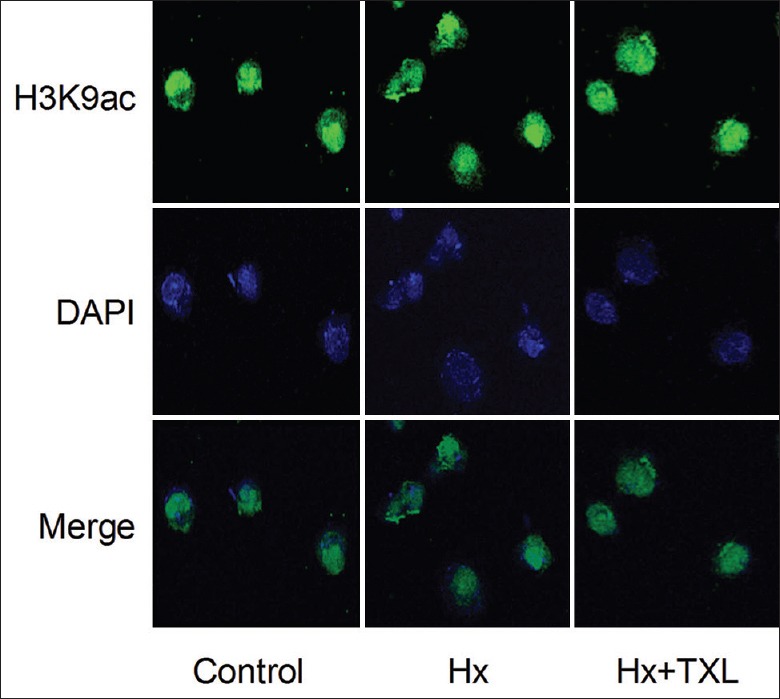

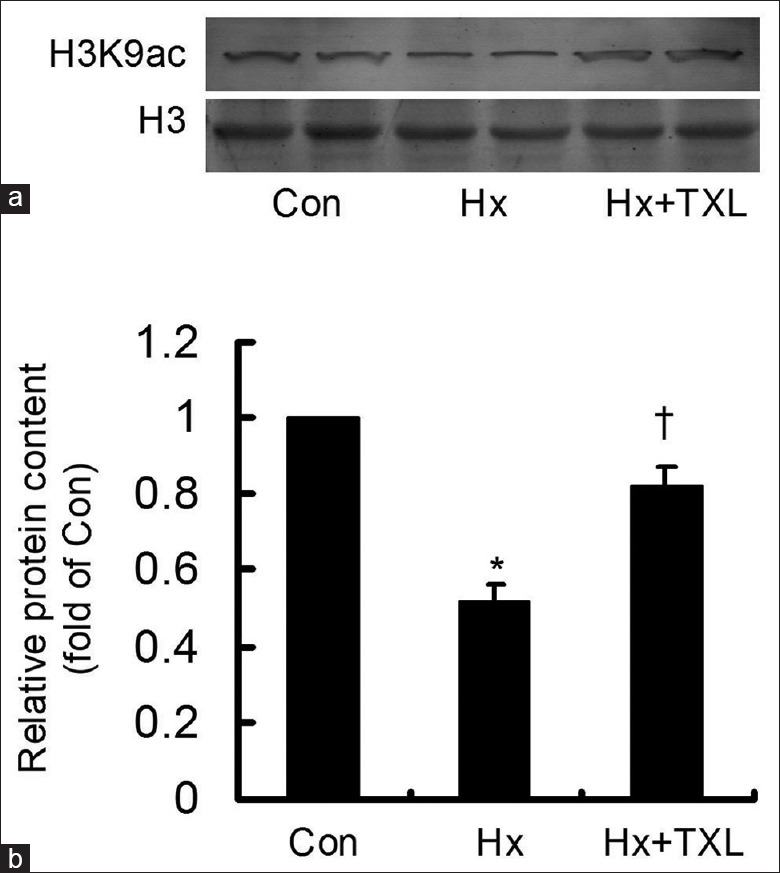

Tongxinluo elevated the hypoxia-inhibited H3K9 acetylation in the claudin-9 gene promoter

After the hypoxia-stimulated cells were treated with high-dose TXL for 24 h, the H3K9ac distribution was evaluated by immunofluorescence [Figure 5]. As shown, H3K9ac was mainly localized in the nucleus, and a distinct difference was hardly seen among the groups. Then, the H3K9ac content in the claudin-9 gene promoter was detected by the DNA pull-down assay [Figure 6]. The H3K9ac content was significantly inhibited by hypoxia. However, TXL treatment reversed the hypoxia-inhibited H3K9ac content with a significant difference (F = 37.766; P = 0.000). The results revealed that TXL elevated the hypoxia-inhibited H3K9ac in the claudin-9 gene promoter, activating claudin-9 gene expression.

Figure 5.

Effect of TXL on the H3K9 acetylation content and distribution (original magnification ×200). H3K9 acetylation was mainly localized in the nucleus, and no distinct difference was seen among the groups. 4’, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole was used to stain the nucleus. Hx: Hypoxia; TXL: Tongxinluo.

Figure 6.

TXL elevated the hypoxia-inhibited H3K9 acetylation in the claudin-9 gene promoter. (a) The H3K9 acetylation content in the claudin-9 gene promoter was detected by the DNA pull-down assay. (b) TXL significantly elevated the hypoxia-inhibited H3K9 acetylation content in the claudin-9 gene promoter. *P < 0.01, compared with Con group;†P < 0.05, compared with Hx group. The data were repeated 3 times and presented as a mean ± standard deviation. Con: Control; Hx: Hypoxia; TXL: Tongxinluo.

DISCUSSION

Claudin-5, claudin-9, and claudin-11 are expressed in endothelial cells to constitute tight junctions, and their deficiency may lead to endothelial hyperpermeability, which is considered as the initiating process and pathological basis of cardiovascular disease. Although TXL can effectively improve cardiac microcirculation to antagonize hypoxia, whether and how TXL affects claudin-5, claudin-9, and claudin-11 in hypoxia-stimulated HCMECs are unknown. In this study, we found that TXL reversed the hypoxia-suppressed claudin-9 and promoted its cytomembrane localization in HCMECs, with attenuation of cell injury. Moreover, TXL elevated the H3K9ac content in the claudin-9 gene promoter. The results manifested that TXL could reverse the hypoxia-suppressed claudin-9 via elevating H3K9ac in its gene promoter, playing protective roles in HCMECs.

Claudins are critical components of the formation and function of tight junctions, which are the major control points of microvascular permeability.[7,8,9] We analyzed and found that claudin-5, claudin-9, and claudin-11 are highly expressed in the heart, and they have all been reported to be expressed in endothelial cells.[10,11,12,13] Although hypoxia has been found to disrupt tight junctions, especially claudin-5 in cerebral endothelial cells,[14,15] the effects of hypoxia on claudin-5, claudin-9, and claudin-11 in cardiac microcirculation have not been explored.

The mRNA expression of claudin-5, claudin-9, and claudin-11 in hypoxia-stimulated HCMECs was investigated. The results demonstrated that hypoxia dramatically suppressed claudin-9 expression, without a notable effect on claudin-5 and claudin-11. The protein content analysis verified the mRNA expression results, confirming the suppression of claudin-9 by hypoxia in HCMECs.

TXL has satisfactory beneficial effects on cardiovascular disease, particularly in the modulation of microcirculation, which has also been proven by our research.[23,24,25] Although TXL has been reported to have a positive effect on the hypoxia-inhibited claudin-1,[26,27] whether TXL regulates claudin-5, claudin-9, and claudin-11, which are highly expressed in the heart, has not been explored. Moreover, we did not find any report about the effect of TXL on H3K9ac.

In this study, it revealed that TXL reversed the hypoxia-suppressed claudin-9 mRNA expression and protein content in HCMECs. Moreover, the distribution pattern illustrated that besides content up-regulation, TXL promoted the cytomembrane localization of claudin-9 in hypoxia-stimulated HCMECs. In addition, the hypoxia-caused morphological cell injury was overtly attenuated by TXL treatment, indicating that TXL up-regulated claudin-9 and promoted its cytomembrane localization, playing protective roles in hypoxia-stimulated HCMECs. Furthermore, TXL elevated the hypoxia-inhibited H3K9ac in the claudin-9 gene promoter, providing a guaranteed claudin-9 gene transcription in HCMECs. However, the intrinsic mechanism of up-regulation of claudin-9 by TXL still needs further clarification.

In conclusion, TXL reversed the hypoxia-suppressed claudin-9 via elevating H3K9ac in its gene promoter, playing protective roles in HCMECs.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by grants from the Major State Basic Research Development Program of China (973 Program) (No. 2012CB518601), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81470595), and the Hebei Natural Science Foundation (No. H2015206101).

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Edited by: Li-Min Chen

REFERENCES

- 1.Tano JY, Gollasch M. Hypoxia and ischemia-reperfusion: A bik contribution? Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2014;307:H811–7. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00319.2014. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00319.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schiano C, Casamassimi A, Vietri MT, Rienzo M, Napoli C. The roles of mediator complex in cardiovascular diseases. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1839:444–51. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2014.04.012. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2014.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mohammed SF, Hussain S, Mirzoyev SA, Edwards WD, Maleszewski JJ, Redfield MM. Coronary microvascular rarefaction and myocardial fibrosis in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Circulation. 2015;131:550–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.009625. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.009625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Petersen JW, Pepine CJ. Microvascular coronary dysfunction and ischemic heart disease: Where are we in 2014? Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2015;25:98–103. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2014.09.013. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2014.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fernlund E, Schlegel TT, Platonov PG, Carlson J, Carlsson M, Liuba P. Peripheral microvascular function is altered in young individuals at risk for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and correlates with myocardial diastolic function. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2015;308:H1351–8. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00714.2014. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00714.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheng X, Wang X, Wan Y, Zhou Q, Zhu H, Wang Y. Myosin light chain kinase inhibitor ML7 improves vascular endothelial dysfunction via tight junction regulation in a rabbit model of atherosclerosis. Mol Med Rep. 2015;12:4109–16. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2015.3973. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2015.3973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hu D, Yu Y, Wang C, Li D, Tai Y, Fang L. microRNA-98 mediated microvascular hyperpermeability during burn shock phase via inhibiting FIH-1. Eur J Med Res. 2015;20:51. doi: 10.1186/s40001-015-0141-5. doi: 10.1186/s40001-015-0141-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ma X, Zhang H, Pan Q, Zhao Y, Chen J, Zhao B, et al. Hypoxia/Aglycemia-induced endothelial barrier dysfunction and tight junction protein downregulation can be ameliorated by citicoline. PLoS One. 2013;8:e82604. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0082604. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0082604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krause G, Protze J, Piontek J. Assembly and function of claudins: Structure-function relationships based on homology models and crystal structures. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2015;42:3–12. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2015.04.010. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2015.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang H, Yu PK, Cringle SJ, Sun X, Yu DY. Intracellular cytoskeleton and junction proteins of endothelial cells in the porcine iris microvasculature. Exp Eye Res. 2015;140:106–16. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2015.08.025. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2015.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu J, Weaver J, Jin X, Zhang Y, Xu J, Liu KJ, et al. Nitric oxide interacts with caveolin-1 to facilitate autophagy-lysosome-mediated claudin-5 degradation in oxygen-glucose deprivation-treated endothelial cells. Mol Neurobiol. 2015;52:1–13. doi: 10.1007/s12035-015-9504-8. doi: 10.1007/s12035-015-9504-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nelson GM, Padera TP, Garkavtsev I, Shioda T, Jain RK. Differential gene expression of primary cultured lymphatic and blood vascular endothelial cells. Neoplasia. 2007;9:1038–45. doi: 10.1593/neo.07643. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wessells H, Sullivan CJ, Tsubota Y, Engel KL, Kim B, Olson NE, et al. Transcriptional profiling of human cavernosal endothelial cells reveals distinctive cell adhesion phenotype and role for claudin 11 in vascular barrier function. Physiol Genomics. 2009;39:100–8. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.90354.2008. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.90354.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Engelhardt S, Al-Ahmad AJ, Gassmann M, Ogunshola OO. Hypoxia selectively disrupts brain microvascular endothelial tight junction complexes through a hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1) dependent mechanism. J Cell Physiol. 2014;229:1096–105. doi: 10.1002/jcp.24544. doi: 10.1002/jcp.24544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boroujerdi A, Welser-Alves JV, Milner R. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 mediates post-hypoxic vascular pruning of cerebral blood vessels by degrading laminin and claudin-5. Angiogenesis. 2015;18:255–64. doi: 10.1007/s10456-015-9464-7. doi: 10.1007/s10456-015-9464-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jia Y, Leung SW. Comparative efficacy of tongxinluo capsule and beta-blockers in treating angina pectoris: Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Altern Complement Med. 2015;21:686–99. doi: 10.1089/acm.2014.0290. doi: 10.1089/acm.2014.0290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li XD, Yang YJ, Cheng YT, Dou KF, Tian Y, Meng XM. Protein kinase A-mediated cardioprotection of tongxinluo relates to the inhibition of myocardial inflammation, apoptosis, and edema in reperfused swine hearts. Chin Med J. 2013;126:1469–79. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0366-6999.2013022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jia Y, Bao F, Huang F, Leung SW. Is tongxinluo more effective than isosorbide dinitrate in treating angina pectoris? A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Altern Complement Med. 2011;17:1109–17. doi: 10.1089/acm.2010.0788. doi: 10.1089/acm.2010.0788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Qi K, Li L, Li X, Zhao J, Wang Y, You S, et al. Cardiac microvascular barrier function mediates the protection of tongxinluo against myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0119846. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0119846. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0119846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shen FF, Jiang TH, Jiang JQ, Lou Y, Hou XM. Traditional Chinese medicine tongxinluo improves cardiac function of rats with dilated cardiomyopathy. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2014. 2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/323870. 323870. doi: 10.1155/2014/323870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li YN, Wang XJ, Li B, Liu K, Qi JS, Liu BH, et al. Tongxinluo inhibits cyclooxygenase-2, inducible nitric oxide synthase, hypoxia-inducible factor-2α/vascular endothelial growth factor to antagonize injury in hypoxia-stimulated cardiac microvascular endothelial cells. Chin Med J. 2015;128:1114–20. doi: 10.4103/0366-6999.155119. doi: 10.4103/0366-6999.155119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dai W, Wei C, Kong H, Jia Z, Han J, Zhang F, et al. Effect of the traditional Chinese medicine tongxinluo on endothelial dysfunction rats studied by using urinary metabonomics based on liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2011;56:86–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2011.04.020. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2011.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cui H, Li X, Li N, Qi K, Li Q, Jin C, et al. Induction of autophagy by tongxinluo through the MEK/ERK pathway protects human cardiac microvascular endothelial cells from hypoxia/reoxygenation injury. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2014;64:180–90. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0000000000000104. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0000000000000104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zheng CY, Song LL, Wen JK, Li LM, Guo ZW, Zhou PP, et al. Tongxinluo (TXL), a traditional Chinese medicinal compound, improves endothelial function after chronic hypoxia both in vivo and in vitro. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2015;65:579–86. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0000000000000226. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0000000000000226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li LM, Zheng B, Zhang RN, Jin LS, Zheng CY, Wang C, et al. Chinese medicine tongxinluo increases tight junction protein levels by inducing KLF5 expression in microvascular endothelial cells. Cell Biochem Funct. 2015;33:226–34. doi: 10.1002/cbf.3108. doi: 10.1002/cbf.3108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fu SP, He SY, Xu B, Hu CJ, Lu SF, Shen WX, et al. Acupuncture promotes angiogenesis after myocardial ischemia through H3K9 acetylation regulation at VEGF gene. PLoS One. 2014;9:e94604. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094604. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lu H, Li Y, Wang Y, Liu Y, Wang W, Jia Z, et al. Wnt-promoted Isl1 expression through a novel TCF/LEF1 binding site and H3K9 acetylation in early stages of cardiomyocyte differentiation of P19CL6 cells. Mol Cell Biochem. 2014;391:183–92. doi: 10.1007/s11010-014-2001-y. doi: 10.1007/s11010-014-2001-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee S, Chen TT, Barber CL, Jordan MC, Murdock J, Desai S, et al. Autocrine VEGF signaling is required for vascular homeostasis. Cell. 2007;130:691–703. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.054. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li Y, Liu D, Zong Y, Qi J, Li B, Liu K, et al. Developmental stage-specific hepatocytes induce maturation of HepG2 cells by rebuilding the regulatory circuit. Mol Med. 2015;21:285–95. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2014.00173. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2014.00173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li Y, Zhao M, Li B, Qi J. Dynamic localization and functional implications of C-peptide might for suppression of iNOS in high glucose-stimulated rat mesangial cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2013;381:255–60. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2013.08.007. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2013.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]