Abstract

Objective:

5-Fluorouracil (5-FU)-based combination therapies are standard treatments for gastrointestinal cancer, where the modulation of autophagy is becoming increasingly important in offering effective treatment for patients in clinical practice. This review focuses on the role of autophagy in 5-FU-induced tumor suppression and cancer therapy in the digestive system.

Data Sources:

All articles published in English from 1996 to date those assess the synergistic effect of autophagy and 5-FU in gastrointestinal cancer therapy were identified through a systematic online search by use of PubMed. The search terms were “autophagy” and “5-FU” and (“colorectal cancer” or “hepatocellular carcinoma” or “pancreatic adenocarcinoma” or “esophageal cancer” or “gallbladder carcinoma” or “gastric cancer”).

Study Selection:

Critical reviews on relevant aspects and original articles reporting in vitro and/or in vivo results regarding the efficiency of autophagy and 5-FU in gastrointestinal cancer therapy were reviewed, analyzed, and summarized. The exclusion criteria for the articles were as follows: (1) new materials (e.g., nanomaterial)-induced autophagy; (2) clinical and experimental studies on diagnostic and/or prognostic biomarkers in digestive system cancers; and (3) immunogenic cell death for anticancer chemotherapy.

Results:

Most cell and animal experiments showed inhibition of autophagy by either pharmacological approaches or via genetic silencing of autophagy regulatory gene, resulting in a promotion of 5-FU-induced cancer cells death. Meanwhile, autophagy also plays a pro-death role and may mediate cell death in certain cancer cells where apoptosis is defective or difficult to induce. The dual role of autophagy complicates the use of autophagy inhibitor or inducer in cancer chemotherapy and generates inconsistency to an extent in clinic trials.

Conclusion:

Autophagy might be a therapeutic target that sensitizes the 5-FU treatment in gastrointestinal cancer.

Keywords: 5-Fluorouracil, Autophagy, Gastrointestinal Cancer, Tumor

INTRODUCTION

The antimetabolite 5-fluorouracil (5-FU)-based combination therapies have been standard treatments for many patients diagnosed with gastrointestinal cancer in the past decades. However, resistance to 5-FU together with its usage has become a common issue, and this has been recognized as a cause of cancer therapy failure. The resistance to anticancer drugs can be attributed to a wide variety of mechanisms including tumor cell heterogeneity, drug efflux, and other periods of tumor microenvironment stress-induced genetic or epigenetic alterations as a cellular response to drug exposure.[1,2] Among these mechanisms, the adaptation of tumor cell to anticancer drug-induced microenvironment stresses is a vital cause of chemotherapy resistance.

Macroautophagy (hereafter denoted simply as autophagy) is a cell survival pathway involving the degradation of cytoplasmic constituents, and the recycling of adenosine triphosphate and essential building blocks for the maintenance of cellular biosynthesis during nutrient deprivation or metabolic stress.[3] For tumor cells, autophagy is a “double-edged sword” since it can be either protective or damaging, and the effects may change during tumor progression.[4,5] The dual role of autophagy in tumor development remains unclear. Current evidence supports the idea that autophagy eliminates damaged organelles and recycle macromolecules, thus functioning as a tumor suppressive mechanism, particularly during malignant transformation and carcinogenesis.[6,7,8] However, in established tumors, cancer cells may need autophagy for cytoprotection to cope with their hostile microenvironments such as nutrient deprivation, hypoxia, the absence of growth factors, and the presence of chemotherapy or some targeted therapy mediated resistances to anticancer therapies.[9,10] Consequently, the combination of autophagy inhibitors with chemotherapy drug has become more attractive in cancer therapy. Most studies have indicated that 5-FU-treatment-induced autophagy of cancer cells in vivo,[11,12,13] and inhibiting autophagy potentiated the anticancer effects of 5-FU. Inhibitory effect of chloroquine (CQ) and its derivative hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) on autophagy in preclinical models and their safety in clinical trials have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA); it might be possible to treat certain cancer types without the need for phase I studies.

Here, the association between autophagy and 5-FU chemotherapy in various gastrointestinal cancer is summarized, the mechanisms of autophagy in 5-FU chemotherapy are reviewed, and the emerging questions of their promising potential as therapeutic targets for the treatment of gastrointestinal cancer are also highlighted.

AUTOPHAGY PARADOX IN THERAPEUTIC PURPOSES IN CANCER

The pioneer work by Liang et al. embraced the discovery that one copy of the Beclin-1 gene is deleted in some specimens of human breast, ovarian, and prostate tumors[14] suggesting that autophagy may play an anti-tumor role in tumorigenesis. During the following two decades, a large number of autophagy-related genes were found at a reduced expression level or even totally lost in certain types of cancer cells,[15,16,17,18,19,20] supporting the conclusion that basal autophagy may act as a cellular housekeeper to eliminate damaged organelles and recycle macromolecules, and thus protect against cell transformation in the early phase of tumorigenesis. Later, as tumors grew, existing evidence highlighted an indispensable role for autophagy in tumorigenesis.[21] In solid tumors, prior to angiogenesis, autophagy defection induces long-term and chronic inflammation in cancer cells undergoing a continuous low-level of necrosis. Alternatively, autophagy-competent cancer cells could survive this nutrient-limited and low oxygen microenvironment by activating autophagic pathways with both no death and no proliferation. This ability to cope with stress is also useful to cancer cells that disseminate and metastasize.[22] Hence, the paradox leads to a similar contradictory response of autophagy in tumor following anticancer treatments. On one hand, autophagy is activated as a protective mechanism to mediate the acquired resistant phenotype of some cancer cells during chemotherapy. On the other hand, autophagy may also function as a death executioner to induce autophagic cell death (a form of physiological cell death that is contradictory to apoptosis). Accordingly, two therapeutic strategies were currently used in the clinical trials: One was to inhibit the cytoprotective function of autophagy to improve the killing efficacy of chemotherapy drugs or resensitize the chemoresistant tumor cells to drugs; the other was to induce autophagic cell death in the apoptosis-defective tumor cells, which showed high resistance to apoptosis by activating autophagic pathways.

AUTOPHAGY-MEDIATED CHEMORESISTANCE TO 5-FLUOROURACIL IN GASTROINTESTINAL CANCER

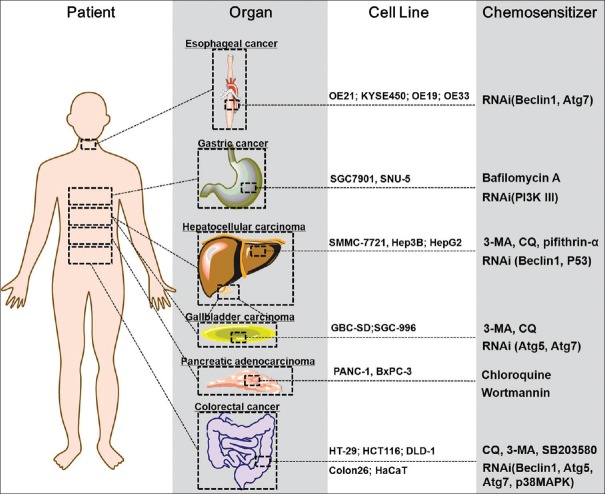

Over the past several years, the selection of chemotherapeutic regimens has expanded greatly due to the development of molecular targeted therapy.[23] Among varieties of those drugs, 5-FU remains the most popular and has been widely used for gastrointestinal cancer for about 40 years.[24] However, the resistance to 5-FU which might result in therapy failure has become a common clinical issue in the treatment of patients with such disease. Regarding the chemoresistance, 5-FU treatment also induces autophagic responses in multiple types of gastrointestinal cancer cells [Figure 1].[25,26,27,28,29,30] So far, the molecular mechanisms of 5-FU-induced autophagy remain poorly defined. Many studies have examined the synergistic effect of autophagy and 5-FU in colorectal cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), pancreatic adenocarcinoma, esophageal cancer, gallbladder carcinoma (GBC), and gastric cancer [Table 1]; some hold great promise and are currently being investigated within the context of phase I and phase II clinical trials [Table 2].

Figure 1.

Autophagy is considered a key mechanism in the development of resistance to 5-fluorouracil. 5-Fluorouracil-based combination therapies are standard treatments for many patients diagnosed with various gastrointestinal tumors. Since autophagy is a mechanism of chemoresistance to 5-fluorouracil, several inhibitors of autophagy, or interference of certain genes will promote sensitivity to 5-fluorouracil in gastrointestinal cancer.

Table 1.

Autophagy in response to 5-FU in different types of gastrointestinal cancer

| Cell lines (cancer type) | Mediating autophagy methods (target) | Regulating mechanisms | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| HT-29 (colorectal cancer) | CQ (lysosome) | p21Cip1, p27Kip1, and CDK2 | [31] |

| DLD-1 (colon cancer) | CQ (lysosome) | p27, p53, CDK2, and cyclin D1 | [32] |

| Colon 26 (colon cancer) | CQ (lysosome) | Bad and Bax | [13] |

| HCT116, HT-29 (colon cancer) | 3-MA (PI3K III), CQ (lysosome), RNAi (Beclin-1, Atg5) | Bcl-2/JNK pathway | [33] |

| HT-29, colon 26 (colon cancer) | 3-MA (PI3K III) | Bcl-xL, cytochrome c/caspase-3/PARP pathway | [34] |

| HCT116, DLD-1 (colon cancer) | 3-MA (PI3K III), RNAi (Atg7) | Bcl-xL, p53-AMPK-mTOR | [11] |

| HaCaT and HCT116 (colon cancer) | SB203580 and RNAi (p38MAPK) | MAP2K, MAPK kinase-3, and MAPK kinase-6 | [35] |

| SMMC-7721, Hep3B, HepG2 (HCC) | 3-MA (PI3K III), CQ (lysosome), RNAi (Beclin-1) | Unknown | [12] |

| HepG2, SMMC7721 (HCC) | Pifithrin-α and RNAi (P53) | ROS | [28] |

| PANC-1, BxPC-3 (pancreatic adenocarcinoma) | CQ (lysosome) and wortmannin (PI3K/PLK1) | Unknown | [27] |

| OE21, KYSE450, OE19, OE33 (esophageal cancer) | RNAi (Beclin-1, Atg7) | Unknown | [30] |

| GBC-SD, SGC-996 (gallbladder carcinoma) | 3-MA, CQ, RNAi (Atg5, Atg7) | Unknown | [26] |

| SGC7901 (gastric cancer) | RNAi (PI3K III) | Unknown | [36] |

| SNU-5 (gastric cancer) | 3’UTR luciferase reporter (Beclin-1) | MiR-30 | [37] |

| SGC-7901 (gastric cancer) | Bafilomycin A1 (vacuolar H+ATPases) | Unknown | [38] |

CQ: Chloroquine; ROS: Reactive oxygen species; HCC: Hepatocellular carcinoma.

Table 2.

Examples of clinical trials involving chloroquine or hydroxychloroquine for the treatment of gastrointestinal cancer

| Condition | HCQ combined therapy | Phase | Clinical trial ID |

|---|---|---|---|

| Liver cancer | TACE | I/II | NCT02013778 |

| Advanced solid tumors | Vorinostat | I | NCT01023737 |

| Colorectal cancer | Vorinostat | II | NCT02316340 |

| Advanced solid tumors, melanoma, prostate or kidney cancer | MK0394 (Akt inhibitor) | I | NCT01480154 |

| Pancreatic cancer | Proton or Photon beam radiation therapy and capecitabine | II | NCT01494155 |

| Pancreatic cancer | Gemcitabine/abraxane | I/II | NCT01506973 |

| Advanced or metastatic cancer | Sirolimus/vorinostat | I | NCT01266057 |

| Pancreatic cancer | Gemcitabine hydrochloride and paclitaxel albumin-stabilized nanoparticle formulation | II | NCT01978184 |

| Colorectal cancer | Fluorouracil, leucovorin calcium, oxaliplatin, and bevacizumab | I/II | NCT01206530 |

| Colorectal cancer | Bevacizumab and combination chemotherapy | II | NCT01006369 |

| Metastatic solid tumors | Temsirolimus | I | NCT00909831 |

| Refractory or relapsed solid tumors | Sorafenib | I | NCT01634893 |

The content of Table 2 was from http://www.cancer.gov/clinicaltrials. HCQ: Hydroxychloroquine; TACE: Transarterial chemoembolization.

Colorectal cancer

5-FU is a cornerstone in chemotherapy of advanced colorectal cancer;[39] improved combinations of 5-FU with irinotecan; or oxaliplatin have progressively increased tumor response as well as the median survival time of patients with unresectable tumor.[40] Previous studies have demonstrated that inhibition of autophagy augments anticancer effects of 5-FU in colorectal cancer,[13,31] and autophagy responds to 5-FU through the regulation of Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL.[34,33] Bcl-2 inhibits autophagy and negatively regulates the autophagy-promoting Beclin-1-VPS34 complex by binding to the BH3 domain of Beclin-1.[41,42] To date, many small molecule BH3 mimetics have been designed to inhibit the anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 proteins and induce apoptosis. However, most of them failed to exhibit antitumor effects in the preclinical and clinical trials,[43] suggesting the induction of autophagic cell death might be better suited at present to the strategies focusing on the inhibition of anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 proteins for overcoming 5-FU resistance.[44]

Recently, the p38MAPK signaling pathways were found to play a critical role in controlling the balance between apoptosis and autophagy in response to 5-FU. The genotoxic stress-induced by 5-FU is mediated by ataxia telangiectasia mutated, and ataxia telangiectasia and Rad3 related proteins, which also promote the activation of the signaling axis, MAPK kinase 6/3-p38MAPK-p53 driven apoptosis.[35] Another mechanism that may participate in the 5-FU-induced autophagy response is p53-AMPK-mTOR pathway.[11,45] 5-FU chemotherapy causes genotoxic stress and then increases p53 expression in colon cancer cells; p53 positively regulates autophagy by activation of AMPK, and subsequent inhibition of mTOR, a process that requires TSC1/2.[46,47] Pharmacologic interference with these interactions might provide a novel therapeutic strategy targeting colorectal cancer cells with high 5-FU treatment resistance. In fact, the combination of oxaliplatin/bevacizumab with HCQ is currently being investigated in clinic trials [Table 2].

Hepatocellular carcinoma

Over the past decades, the surgical operation has been the most effective therapeutic strategy for HCC patients at early stages,[48] but most patients reach an advanced stage for the first diagnosis of HCC and lose the opportunity of surgical resection. In those patients with advanced HCC, chemotherapy is mostly ineffective with a low response rate.[49] It has been revealed that suppression of autophagy enhances oxaliplatin-induced cell death[50] while combining it with bevacizumab markedly inhibits the growth of HCC.[51] Moreover, the combination of CQ with sorafenib (a potent multikinase inhibitor that has been recognized as the standard systemic treatment for patients with advanced HCC-based on the results of Study of Heart and Renal Protection trial)[52] can generate more ER stress-induced cell death in HCC both in vivo and in vitro.[53]

Several genes and signal pathways contribute to autophagy-mediated chemoresistance in HCC. Recent research revealed that p53 contributes to cell survival and chemoresistance in HCC under nutrient-deprived conditions by modulating autophagy activation.[28] Blocking p53 leads to impaired activation of autophagy, increased nutrient starvation, and 5-FU-induced cell death in nutrient-deprived HCC accompanied by a remarkable increase in the reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation and mitochondrial damage.

Activation of Mek/Erk signaling could activate autophagy in tumor cells.[54] Recently, linifanib has been reported to inhibit PDGFR-β and its downstream Akt/mTOR and Mek/Erk signal pathways and activate autophagy in HCC cells, which contributes to their survival both in vitro and in vivo.[55] Several other mechanisms triggering autophagy have also been investigated. For instance, Zhou et al. reported that autophagy inhibits chemotherapy-induced apoptosis through downregulation of Bad and Bim in HCC cells.[56] JNK-Bcl-2/Bcl-xL-Bax/Bak pathway and SMAD2 signaling have also been determined as contributors to autophagy of HCC.[57,58]

Pancreatic adenocarcinoma

Autophagy plays a cytoprotective role in response to chemotherapy in pancreatic cancer cells lines, PANC-1, and BxPC-3.[27] In a recent study, genistein potentiates the antitumor effect of 5-FU by inducing apoptosis and autophagy in MIA PaCa-2 human pancreatic cancer cells and their derived xenografts.[59] Furthermore, in phase I/II clinical trial, preoperative inhibition of autophagy with HCQ and gemcitabine in patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma is safe, well-tolerated, and effective.[60] However, a contradictive study showed that HCQ monotherapy achieved inconsistent autophagy inhibition and demonstrated negligible therapeutic efficacy,[61] which might be because the use of HCQ with concurrent chemotherapy may obviate the need for complete autophagy inhibition in tumors, but the exact mechanisms explaining the inconsistency in those clinic trials are yet to be determined.

Inhibition of autophagy with CQ promotes apoptotic cell death in response to inhibition of the PI3K-mTOR pathway in pancreatic adenocarcinoma both in vitro and in vivo.[62] Activation of PI3K results in sequential AKT and mTOR activation, ultimately suppressing autophagy.[63,64] Inhibition of autophagy results in enhanced apoptosis following treatment with PI3K inhibitors, in particular, dual-targeted PI3K/mTOR inhibitors. In this sense, Type I PI3K inhibitors (lithium and carbamazepine), type III PI3K inhibitors (3-MA, LY294002 and wortmannin), AKT inhibitors (perifosine and API-2), and mTORinhibitors (rapamycin, RAD001 and CCI-779) currently undergoing clinical evaluation are all promising anticancer agents to improve treatment outcomes in pancreatic adenocarcinoma.[65,66,67]

Esophageal cancer

Malignant cell clones resistance to chemotherapy is a major cause of treatment failure in esophageal squamous carcinoma cells. Several studies have revealed that induction of autophagy plays a significant role in the resistance and recovery of chemotherapeutic drug-treated esophageal cancer cells.[30,68,69,70,71] In most studies, the inhibition of autophagy leads to increased esophageal cancer cell apoptosis, indicating that autophagy might be a prosurvival mechanism rather than a cell death mechanism. Efforts have been made to investigate the exact self-protective mechanism of autophagy, and it was found to be associated with PI3K/Akt/mTOR[72,73] and Stat3/Bcl-2 pathway.[74] Recently, a typical protein kinase CI (PKCI) has been reported to regulate β-catenin in an autophagy-dependent manner in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma cells.[75] Moreover, PKCI may regulate autophagy via intracellular ROS, a known autophagy inducer that promotes autophagy by inactivating the mTOR pathway[76] or inhibiting ATG4,[77] indicating that PKCI could be used as an autophagy inducer in killing esophageal cancer cells.

Gallbladder carcinoma

So far, there are no adjuvant chemotherapeutic combinations widely accepted for the primary GBC due to their toxicity, drug resistance, and limited efficacy resulting in a low survival rate, and almost half of patients already have metastatic disease at the time of surgery.[78,79] Currently, 5-FU has been used in phase II trial of combination chemotherapy for advanced cancers of the gallbladder; the toxicity was tolerable but substantial.[80]

We recently observed that combination treatment of CQ and 5-FU was more efficient in killing GBC cells, and pretreatment with CQ increased the 5-FU-induced apoptosis and the G0/G1 arrest in vitro.[81] It is possible that cell cycle influences autophagic degradation, and inhibition of autophagy may cause cells to be arrested to the G0/G1-phase.[26] Given that both apoptosis and autophagy are crucial mechanisms regulating cell survival and homeostasis, the relationship between them is quite complicated.[82] In some cases, they had no connection[83,84] while, in some instances, it was demonstrated that autophagy might promote or even restrain apoptosis.[85,86] The exact mechanism for the inhibition of autophagy through an increase in the cytotoxicity of 5-FU in GBC cells needs to be verified.

Gastric cancer

The cytoprotective role of autophagy in response to chemotherapy has been confirmed in the 5-FU treatment of gastric cancer cells.[38,87] In agreement with this, Zhu et al. showed that PI3K inhibitor promotes the antitumor activity of 5-FU through autophagy.[36] Interestingly, a study that was conducted recently showed that 5-FU may suppress miR-30 to upregulate Beclin-1 and thus induce autophagic cell death and cell proliferation arrest in GC cells[37] indicating that 5-FU may have its inhibitory effect through induced autophagy and specifically autophagic cell death.

AUTOPHAGIC CELL DEATH CONTRIBUTES TO 5-FLUOROURACIL-BASED CHEMOTHERAPY

Autophagy is generally considered to be a survival mechanism. However, when the severity or the duration of the stress is too long, or in apoptotic-deficient cells, autophagy may participate in cell death. Therefore, it is called a nonapoptotic form of programmed cell death (PCD) as autophagic cell death or type II PCD (type I being apoptosis itself).

As mentioned above, autophagy is believed to have both pro- and anti-oncogenic effects on tumor cells.[88] Besides the protective mechanism to mediate the acquired resistance phenotype of certain cancer cells during chemotherapy, autophagy is also considered to play a pro-death role associated with autophagosome, potentially functioning as a tumor suppressor mechanism similar to apoptosis.[6,89] To date, autophagy inducers are widely used to kill cancer cells;[90,91,92,93] it has been reported that some drugs were used for cancer treatment due to their effect on cell autophagy. For example, aloe-emodin-induced rat C6 glioma autophagic death;[94] Resveratrol-induced ovarian cancer cell death through autophagy;[95] 6-shogaol-induced A549 autophagy by suppressing the AKT/mTOR pathway.[96]

In gastrointestinal cancer types, many studies demonstrated that autophagy may mediate cell death in certain cancer cells where apoptosis is defective or difficult to induce. For instance, triptolide, the precursor of tripchlorolide, inhibits the growth of hamster cholangiocarcinoma,[97] and human tumors transplanted into nude mice.[98] It also suppresses the growth of pancreatic cancer[99] and induces cell death through apoptosis and autophagy.[100] Furthermore, at the molecular level, autophagic cell death could be induced in PUMA- or Bax- deficient human colon cancer cells after treatment with 5-FU, resulting in significantly reduced cell proliferation.[101] Thus, inducing autophagy when apoptosis is inhibited or directly triggering autophagic signaling such as PI3K-Akt-mTOR pathway,[102] and inhibitors are possible strategies that can be applied to cancer therapy. These strategies complicate the use of autophagy inhibitor or inducer in cancer chemotherapy and the specific role that autophagy plays at different stages in cancer progression and determination of its cell type and genetic context-dependency needs to be clarified.

CONCLUSIONS AND PERSPECTIVES

Although research on autophagy in chemotherapy has expanded dramatically, it is still controversial whether autophagy activation leads to cell survival or cell death in cancer chemotherapy since autophagy plays a dual role in tumor promotion and tumor suppression. Understanding the novel function of autophagy may allow us to develop a promising therapeutic strategy to enhance the effects of chemotherapy and improve clinical outcomes in the treatment of cancer patients.

Prior to the clinical applications, a mechanistic understanding of the biology of autophagy is urgently needed. There are several questions to be addressed in future studies. First, although 5-FU induces autophagy in many gastrointestinal cancer cells, it is still difficult to explain whether the autophagy accompanies or induces cell death, or only functions as a protective mechanism activated in response to stress-induced by the treatment of 5-FU or is a cell death pathway activated when apoptosis is disabled, or whether all the effects arise in different contexts. In fact, it is very likely that the outcome of autophagy activation is highly dependent on the tumor types.[103,104] Second, more new and reliable methods for measuring autophagy in 5-FU treated samples are needed to be developed to maximize the potential of autophagy in the stringent clinical study. Third, among the autophagy inhibitors, only CQ and HCQ are approved by the FDA, but the toxicities and minimal single-agent anticancer efficacy of CQ or HCQ have restricted their clinical application. New and exciting autophagy inhibitors are worthy of further investigation in the future. Overall, our efforts in these areas would increase the understanding of the functional relevance of autophagy within the tumor microenvironment and ongoing dialogue between emerging laboratory and clinical research about targeting autophagy and provide a promising therapeutic strategy to circumvent resistance and enhance the effects of anticancer therapies for cancer patients.

Financial support and sponsorship

This study was supported by a grant of Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (No. LY13H180001).

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Edited by: Yuan-Yuan Ji

REFERENCES

- 1.Ringborg U, Platz A. Chemotherapy resistance mechanisms. Acta Oncol. 1996;35(Suppl 5):76–80. doi: 10.3109/02841869609083976. doi: 10.3109/02841869609083976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Szakács G, Paterson JK, Ludwig JA, Booth-Genthe C, Gottesman MM. Targeting multidrug resistance in cancer. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2006;5:219–34. doi: 10.1038/nrd1984. doi: 10.1038/nrd1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yang Z, Klionsky DJ. Eaten alive: A history of macroautophagy. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:814–22. doi: 10.1038/ncb0910-814. doi: 10.1038/ncb0910-814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yousefi S, Simon HU. Autophagy in cancer and chemotherapy. Results Probl Cell Differ. 2009;49:183–90. doi: 10.1007/400_2008_25. doi: 10.1007/400_2008_25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Notte A, Leclere L, Michiels C. Autophagy as a mediator of chemotherapy-induced cell death in cancer. Biochem Pharmacol. 2011;82:427–34. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2011.06.015. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2011.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mathew R, Kongara S, Beaudoin B, Karp CM, Bray K, Degenhardt K, et al. Autophagy suppresses tumor progression by limiting chromosomal instability. Genes Dev. 2007;21:1367–81. doi: 10.1101/gad.1545107. doi: 10.1101/gad.1545107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mathew R, Karp CM, Beaudoin B, Vuong N, Chen G, Chen HY, et al. Autophagy suppresses tumorigenesis through elimination of p62. Cell. 2009;137:1062–75. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.03.048. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.03.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Degenhardt K, Mathew R, Beaudoin B, Bray K, Anderson D, Chen G, et al. Autophagy promotes tumor cell survival and restricts necrosis, inflammation, and tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell. 2006;10:51–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.06.001. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ccr.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maycotte P, Thorburn A. Autophagy and cancer therapy. Cancer Biol Ther. 2011;11:127–37. doi: 10.4161/cbt.11.2.14627. doi: 10.4161/cbt.11.2.14627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sui X, Chen R, Wang Z, Huang Z, Kong N, Zhang M, et al. Autophagy and chemotherapy resistance: A promising therapeutic target for cancer treatment. Cell Death Dis. 2013;4:e838. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.350. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li J, Hou N, Faried A, Tsutsumi S, Kuwano H. Inhibition of autophagy augments 5-fluorouracil chemotherapy in human colon cancer in vitro and in vivo model. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46:1900–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.02.021. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guo XL, Li D, Hu F, Song JR, Zhang SS, Deng WJ, et al. Targeting autophagy potentiates chemotherapy-induced apoptosis and proliferation inhibition in hepatocarcinoma cells. Cancer Lett. 2012;320:171–9. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2012.03.002. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.canlet.2012.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sasaki K, Tsuno NH, Sunami E, Kawai K, Hongo K, Hiyoshi M, et al. Resistance of colon cancer to 5-fluorouracil may be overcome by combination with chloroquine, an in vivo study. Anticancer Drugs. 2012;23:675–82. doi: 10.1097/CAD.0b013e328353f8c7. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2012.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liang XH, Jackson S, Seaman M, Brown K, Kempkes B, Hibshoosh H, et al. Induction of autophagy and inhibition of tumorigenesis by beclin 1. Nature. 1999;402:672–6. doi: 10.1038/45257. doi: 10.1038/45257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miracco C, Cosci E, Oliveri G, Luzi P, Pacenti L, Monciatti I, et al. Protein and mRNA expression of autophagy gene Beclin 1 in human brain tumours. Int J Oncol. 2007;30:429–36. doi: 10.3892/ijo.30.2.429. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liang C, Feng P, Ku B, Dotan I, Canaani D, Oh BH, et al. Autophagic and tumour suppressor activity of a novel Beclin1-binding protein UVRAG. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:688–99. doi: 10.1038/ncb1426. doi: 10.1038/ncb1426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kang MR, Kim MS, Oh JE, Kim YR, Song SY, Kim SS, et al. Frameshift mutations of autophagy-related genes ATG2B, ATG5, ATG9B and ATG12 in gastric and colorectal cancers with microsatellite instability. J Pathol. 2009;217:702–6. doi: 10.1002/path.2509. doi: 10.1002/path.2509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coppola D, Khalil F, Eschrich SA, Boulware D, Yeatman T, Wang HG. Down-regulation of Bax-interacting factor-1 in colorectal adenocarcinoma. Cancer. 2008;113:2665–70. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23892. doi: 10.1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takamura A, Komatsu M, Hara T, Sakamoto A, Kishi C, Waguri S, et al. Autophagy-deficient mice develop multiple liver tumors. Genes Dev. 2011;25:795–800. doi: 10.1101/gad.2016211. doi: 10.1101/gad.2016211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hervouet E, Claude-Taupin A, Gauthier T, Perez V, Fraichard A, Adami P, et al. The autophagy GABARAPL1 gene is epigenetically regulated in breast cancer models. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:729. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1761-4. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1761-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kenific CM, Thorburn A, Debnath J. Autophagy and metastasis: Another double-edged sword. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2010;22:241–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.10.008. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fung C, Lock R, Gao S, Salas E, Debnath J. Induction of autophagy during extracellular matrix detachment promotes cell survival. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:797–806. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-10-1092. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-10-1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Giantonio BJ, Catalano PJ, Meropol NJ, O’Dwyer PJ, Mitchell EP, Alberts SR, et al. Bevacizumab in combination with oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin (FOLFOX4) for previously treated metastatic colorectal cancer: Results from the Eastern cooperative oncology group study E3200. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1539–44. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.6305. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.6305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hamilton SR. Targeted therapy of cancer: New roles for pathologists in colorectal cancer. Mod Pathol. 2008;21(Suppl 2):S23–30. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2008.14. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2008.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schonewolf CA, Mehta M, Schiff D, Wu H, Haffty BG, Karantza V, et al. Autophagy inhibition by chloroquine sensitizes HT-29 colorectal cancer cells to concurrent chemoradiation. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2014;6:74–82. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v6.i3.74. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v6.i3.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liang X, Tang J, Liang Y, Jin R, Cai X. Suppression of autophagy by chloroquine sensitizes 5-fluorouracil-mediated cell death in gallbladder carcinoma cells. Cell Biosci. 2014;4:10. doi: 10.1186/2045-3701-4-10. doi: 10.1186/2045-3701-4-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hashimoto D, Bläuer M, Hirota M, Ikonen NH, Sand J, Laukkarinen J. Autophagy is needed for the growth of pancreatic adenocarcinoma and has a cytoprotective effect against anticancer drugs. Eur J Cancer. 2014;50:1382–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2014.01.011. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2014.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guo XL, Hu F, Zhang SS, Zhao QD, Zong C, Ye F, et al. Inhibition of p53 increases chemosensitivity to 5-FU in nutrient-deprived hepatocarcinoma cells by suppressing autophagy. Cancer Lett. 2014;346:278–84. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2014.01.011. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2014.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yen CY, Chiang WF, Liu SY, Cheng PC, Lee SY, Hong WZ, et al. Long-term stimulation of areca nut components results in increased chemoresistance through elevated autophagic activity. J Oral Pathol Med. 2014;43:91–6. doi: 10.1111/jop.12102. doi: 10.1111/jop.12102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.O’Donovan TR, O’Sullivan GC, McKenna SL. Induction of autophagy by drug-resistant esophageal cancer cells promotes their survival and recovery following treatment with chemotherapeutics. Autophagy. 2011;7:509–24. doi: 10.4161/auto.7.6.15066. doi: 10.4161/auto.7.6.15066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sasaki K, Tsuno NH, Sunami E, Tsurita G, Kawai K, Okaji Y, et al. Chloroquine potentiates the anti-cancer effect of 5-fluorouracil on colon cancer cells. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:370. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-370. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Choi JH, Yoon JS, Won YW, Park BB, Lee YY. Chloroquine enhances the chemotherapeutic activity of 5-fluorouracil in a colon cancer cell line via cell cycle alteration. APMIS. 2012;120:597–604. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2012.02876.x. doi: 10.1111/j. 1600-0463.2012.02876.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sui X, Kong N, Wang X, Fang Y, Hu X, Xu Y, et al. JNK confers 5-fluorouracil resistance in p53-deficient and mutant p53-expressing colon cancer cells by inducing survival autophagy. Sci Rep. 2013;4:4694. doi: 10.1038/srep04694. doi: 10.1038/srep04694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 34.Li J, Hou N, Faried A, Tsutsumi S, Takeuchi T, Kuwano H. Inhibition of autophagy by 3-MA enhances the effect of 5-FU-induced apoptosis in colon cancer cells. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:761–71. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-0260-0. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-0260-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.de la Cruz-Morcillo MA, Valero ML, Callejas-Valera JL, Arias-González L, Melgar-Rojas P, Galán-Moya EM, et al. P38MAPK is a major determinant of the balance between apoptosis and autophagy triggered by 5-fluorouracil: Implication in resistance. Oncogene. 2012;31:1073–85. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.321. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhu BS, Sun JL, Gong W, Zhang XD, Wu YY, Xing CG. Effects of 5-fluorouracil and class III phosphoinositide 3-kinase small interfering RNA combination therapy on SGC7901 human gastric cancer cells. Mol Med Rep. 2015;11:1891–8. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2014.2926. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2014.2926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang C, Pan Y. Fluorouracil induces autophagy-related gastric carcinoma cell death through Beclin-1 upregulation by miR-30 suppression. Tumour Biol. 2015:1–6. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-3775-6. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-3775-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li LQ, Xie WJ, Pan D, Chen H, Zhang L. Inhibition of autophagy by bafilomycin A1 promotes chemosensitivity of gastric cancer cells. Tumor Biol. 2015:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-3842-z. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-3842-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xu R, Zhou B, Fung PC, Li X. Recent advances in the treatment of colon cancer. Histol Histopathol. 2006;21:867–72. doi: 10.14670/HH-21.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.de Gramont A, Figer A, Seymour M, Homerin M, Hmissi A, Cassidy J, et al. Leucovorin and fluorouracil with or without oxaliplatin as first-line treatment in advanced colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:2938–47. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.16.2938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shimizu S, Kanaseki T, Mizushima N, Mizuta T, Arakawa-Kobayashi S, Thompson CB, et al. Role of Bcl-2 family proteins in a non-apoptotic programmed cell death dependent on autophagy genes. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:1221–8. doi: 10.1038/ncb1192. doi: 10.1038/ncb1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pattingre S, Tassa A, Qu X, Garuti R, Liang XH, Mizushima N, et al. Bcl-2 antiapoptotic proteins inhibit Beclin 1-dependent autophagy. Cell. 2005;122:927–39. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.07.002. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.07.00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Billard C. BH3 mimetics: Status of the field and new developments. Mol Cancer Ther. 2013;12:1691–700. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-13-0058. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hersey P, Zhang XD. Overcoming resistance of cancer cells to apoptosis. J Cell Physiol. 2003;196:9–18. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10256. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hu T, Wang L, Zhang L, Lu L, Shen J, Chan RL, et al. Sensitivity of apoptosis-resistant colon cancer cells to tanshinones is mediated by autophagic cell death and p53-independent cytotoxicity. Phytomedicine. 2015;22:536–44. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2015.03.010. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2015.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Feng Z, Zhang H, Levine AJ, Jin S. The coordinate regulation of the p53 and mTOR pathways in cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:8204–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502857102. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502857102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ju J, Schmitz JC, Song B, Kudo K, Chu E. Regulation of p53 expression in response to 5-fluorouracil in human cancer RKO cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:4245–51. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2890. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Raza A, Sood GK. Hepatocellular carcinoma review: Current treatment, and evidence-based medicine. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:4115–27. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i15.4115. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i15.4115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Uhm JE, Park JO, Lee J, Park YS, Park SH, Yoo BC, et al. A phase II study of oxaliplatin in combination with doxorubicin as first-line systemic chemotherapy in patients with inoperable hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2009;63:929–35. doi: 10.1007/s00280-008-0817-4. doi: 10.1007/s00280-008-0817-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ding ZB, Hui B, Shi YH, Zhou J, Peng YF, Gu CY, et al. Autophagy activation in hepatocellular carcinoma contributes to the tolerance of oxaliplatin via reactive oxygen species modulation. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:6229–38. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0816. doi: 1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Guo XL, Li D, Sun K, Wang J, Liu Y, Song JR, et al. Inhibition of autophagy enhances anticancer effects of bevacizumab in hepatocarcinoma. J Mol Med (Berl) 2013;91:473–83. doi: 10.1007/s00109-012-0966-0. doi: 10.1007/s00109-012-0966-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, Hilgard P, Gane E, Blanc JF, et al. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:378–90. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0708857. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0708857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shi YH, Ding ZB, Zhou J, Hui B, Shi GM, Ke AW, et al. Targeting autophagy enhances sorafenib lethality for hepatocellular carcinoma via ER stress-related apoptosis. Autophagy. 2011;7:1159–72. doi: 10.4161/auto.7.10.16818. doi: 10.4161/auto.7.10.16818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang J, Whiteman MW, Lian H, Wang G, Singh A, Huang D, et al. A non-canonical MEK/ERK signaling pathway regulates autophagy via regulating Beclin 1. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:21412–24. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.026013. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.026013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pan H, Wang Z, Jiang L, Sui X, You L, Shou J, et al. Autophagy inhibition sensitizes hepatocellular carcinoma to the multikinase inhibitor linifanib. Sci Rep. 2014;4:6683. doi: 10.1038/srep06683. doi: 10.1038/srep06683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhou Y, Sun K, Ma Y, Yang H, Zhang Y, Kong X, et al. Autophagy inhibits chemotherapy-induced apoptosis through downregulating Bad and Bim in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Sci Rep. 2014;4:5382. doi: 10.1038/srep05382. doi: 10.1038/srep05382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yang J, Yao S. JNK-Bcl-2/Bcl-xL-Bax/Bak pathway mediates the crosstalk between matrine-induced autophagy and apoptosis via interplay with Beclin 1. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16:25744–58. doi: 10.3390/ijms161025744. doi: 10.3390/ijms161025744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sun R, Luo Y, Li J, Wang Q, Li J, Chen X, et al. Ammonium chloride inhibits autophagy of hepatocellular carcinoma cells through SMAD2 signaling. Tumour Biol. 2015;36:1173–7. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-2699-x. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-2699-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Suzuki R, Kang Y, Li X, Roife D, Zhang R, Fleming JB. Genistein potentiates the antitumor effect of 5-Fluorouracil by inducing apoptosis and autophagy in human pancreatic cancer cells. Anticancer Res. 2014;34:4685–92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Boone BA, Bahary N, Zureikat AH, Moser AJ, Normolle DP, Wu WC, et al. Safety and biologic response of pre-operative autophagy inhibition in combination with gemcitabine in patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:4402–10. doi: 10.1245/s10434-015-4566-4. doi: 10.1245/s10434-015-4566-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wolpin BM, Rubinson DA, Wang X, Chan JA, Cleary JM, Enzinger PC, et al. Phase II and pharmacodynamic study of autophagy inhibition using hydroxychloroquine in patients with metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Oncologist. 2014;19:637–8. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2014-0086. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2014-0086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mirzoeva OK, Hann B, Hom YK, Debnath J, Aftab D, Shokat K, et al. Autophagy suppression promotes apoptotic cell death in response to inhibition of the PI3K-mTOR pathway in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. J Mol Med (Berl) 2011;89:877–89. doi: 10.1007/s00109-011-0774-y. doi: 10.1007/s00109-011-0774-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.LoPiccolo J, Blumenthal GM, Bernstein WB, Dennis PA. Targeting the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway: Effective combinations and clinical considerations. Drug Resist Updat. 2008;11:32–50. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2007.11.003. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mamane Y, Petroulakis E, LeBacquer O, Sonenberg N. mTOR, translation initiation and cancer. Oncogene. 2006;25:6416–22. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209888. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chen N, Karantza-Wadsworth V. Role and regulation of autophagy in cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1793:1516–23. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.12.013. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Crazzolara R, Bradstock KF, Bendall LJ. RAD001 (Everolimus) induces autophagy in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Autophagy. 2009;5:727–8. doi: 10.4161/auto.5.5.8507. doi: 10.4161/auto.5.5.8507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tanemura M, Saga A, Kawamoto K, Machida T, Deguchi T, Nishida T, et al. Rapamycin induces autophagy in islets: Relevance in islet transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2009;41:334–8. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2008.10.032. doi: 10.1016/j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kong J, Whelan KA, Laczkó D, Dang B, Caro Monroig A, Soroush A, et al. Autophagy levels are elevated in Barrett's esophagus and promote cell survival from acid and oxidative stress. Mol Carcinog. 2015:1–16. doi: 10.1002/mc.22406. doi: 10.1002/mc.22406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yu L, Gu C, Zhong D, Shi L, Kong Y, Zhou Z, et al. Induction of autophagy counteracts the anticancer effect of cisplatin in human esophageal cancer cells with acquired drug resistance. Cancer Lett. 2014;355:34–45. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2014.09.020. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2014.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Liu D, Yang Y, Liu Q, Wang J. Inhibition of autophagy by 3-MA potentiates cisplatin-induced apoptosis in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma cells. Med Oncol. 2011;28:105–11. doi: 10.1007/s12032-009-9397-3. doi: 10.1007/s12032-009-9397-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yang Y, Wen F, Dang L, Fan Y, Liu D, Wu K, et al. Insulin enhances apoptosis induced by cisplatin in human esophageal squamous cell carcinoma EC9706 cells related to inhibition of autophagy. Chin Med J. 2014;127:353–8. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0366-6999.20130996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yang Y, Sun X, Yang Y, Yang X, Zhu H, Dai S, et al. Gambogic acid enhances the radiosensitivity of human esophageal cancer cells by inducing reactive oxygen species via targeting Akt/mTOR pathway. Tumour Biol. 2015:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-3974-1. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-3974-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Liu D, Gao M, Yang Y, Qi YU, Wu K, Zhao S. Inhibition of autophagy promotes cell apoptosis induced by the proteasome inhibitor MG-132 in human esophageal squamous cell carcinoma EC9706 cells. Oncol Lett. 2015;9:2278–82. doi: 10.3892/ol.2015.3047. doi: 10.3892/ol.2015.3047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Feng Y, Ke C, Tang Q, Dong H, Zheng X, Lin W, et al. Metformin promotes autophagy and apoptosis in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma by downregulating Stat3 signaling. Cell Death Dis. 2014;5:e1088. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2014.59. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2014.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wang BS, Yang Y, Lu HZ, Shang L, Zhang Y, Hao JJ, et al. Inhibition of atypical protein kinase Cι induces apoptosis through autophagic degradation of ß-catenin in esophageal cancer cells. Mol Carcinog. 2014;53:514–25. doi: 10.1002/mc.22003. doi: 10.1002/mc.22003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Klionsky DJ. Autophagy: From phenomenology to molecular understanding in less than a decade. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:931–7. doi: 10.1038/nrm2245. doi: 10.1038/nrm2245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Scherz-Shouval R, Shvets E, Fass E, Shorer H, Gil L, Elazar Z. Reactive oxygen species are essential for autophagy and specifically regulate the activity of Atg4. EMBO J. 2007;26:1749–60. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601623. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chen Y, Chen Y, Yu G, Ding H. Lymphangiogenic and angiogentic microvessel density in gallbladder carcinoma. Hepatogastroenterology. 2011;58:20–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wang SJ, Kalpathy-Cramer J, Kim JS, Fuller CD, Thomas CR. Parametric survival models for predicting the benefit of adjuvant chemoradiotherapy in gallbladder cancer. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2010;2010:847–51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sohn BS, Yuh YJ, Kim KH, Jeon TJ, Kim NS, Kim SR. Phase II trial of combination chemotherapy with gemcitabine, 5-fluorouracil and cisplatin for advanced cancers of the bile duct, gallbladder, and ampulla of Vater. Tumori. 2013;99:139–44. doi: 10.1177/030089161309900203. doi: 10.1700/1283.14182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Tang J, Liang X, Ma R, Liu J, Liu X, Cai X. Effects of autophagy on 5-fluorouracil cytotoxicity for gallbladder carcinoma GBC-SD cell (in Chinese) Natl Med J China. 2014;94:612–6. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0376-2491.2014.08.015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Maiuri MC, Zalckvar E, Kimchi A, Kroemer G. Self-eating and self-killing: Crosstalk between autophagy and apoptosis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:741–52. doi: 10.1038/nrm2239. doi: 10.1038/nrm223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zhang YH, Wu YL, Tashiro S, Onodera S, Ikejima T. Reactive oxygen species contribute to oridonin-induced apoptosis and autophagy in human cervical carcinoma HeLa cells. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2011;32:1266–75. doi: 10.1038/aps.2011.92. doi: 10.1038/aps.2011.92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wang L, Yu C, Lu Y, He P, Guo J, Zhang C, et al. TMEM166, a novel transmembrane protein, regulates cell autophagy and apoptosis. Apoptosis. 2007;12:1489–502. doi: 10.1007/s10495-007-0073-9. doi: 10.1007/s10495-007-0073-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Xue L, Fletcher GC, Tolkovsky AM. Autophagy is activated by apoptotic signalling in sympathetic neurons: An alternative mechanism of death execution. Mol Cell Neurosci. 1999;14:180–98. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1999.0780. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1999.0780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Viola G, Bortolozzi R, Hamel E, Moro S, Brun P, Castagliuolo I, et al. MG-2477, a new tubulin inhibitor, induces autophagy through inhibition of the Akt/mTOR pathway and delayed apoptosis in A549 cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2012;83:16–26. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2011.09.017. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2011.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bhattacharya B, Low SH, Soh C, Kamal Mustapa N, Beloueche-Babari M, Koh KX, et al. Increased drug resistance is associated with reduced glucose levels and an enhanced glycolysis phenotype. Br J Pharmacol. 2014;171:3255–67. doi: 10.1111/bph.12668. doi: 10.1111/bph.12668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Czyzyk-Krzeska MF, Meller J, Plas DR. Not all autophagy is equal. Autophagy. 2012;8:1155–6. doi: 10.4161/auto.20650. doi: 10.4161/auto. 20650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Brech A, Ahlquist T, Lothe RA, Stenmark H. Autophagy in tumour suppression and promotion. Mol Oncol. 2009;3:366–75. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2009.05.007. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2009.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Turcotte S, Giaccia AJ. Targeting cancer cells through autophagy for anticancer therapy. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2010;22:246–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.12.007. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hao J, Pei Y, Ji G, Li W, Feng S, Qiu S. Autophagy is induced by 3ß-O-succinyl-lupeol (LD9-4) in A549 cells via up-regulation of Beclin 1 and down-regulation mTOR pathway. Eur J Pharmacol. 2011;670:29–38. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2011.08.045. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2011.08.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Zhou X, Qiu J, Wang Z, Huang N, Li X, Li Q, et al. In vitro and in vivo anti-tumor activities of anti-EGFR single-chain variable fragment fused with recombinant gelonin toxin. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2012;138:1081–90. doi: 10.1007/s00432-012-1181-7. doi: 10.1007/s00432-012-1181-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Chen L, Liu Q, Huang Z, Wu F, Li Z, Chen X, et al. Tripchlorolide induces cell death in lung cancer cells by autophagy. Int J Oncol. 2012;40:1066–70. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2011.1278. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2011.1278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Mijatovic S, Maksimovic-Ivanic D, Radovic J, Miljkovic Dj, Harhaji Lj, Vuckovic O, et al. Anti-glioma action of aloe emodin: The role of ERK inhibition. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2005;62:589–98. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-4425-8. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-4425-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Opipari AW, Jr, Tan L, Boitano AE, Sorenson DR, Aurora A, Liu JR. Resveratrol-induced autophagocytosis in ovarian cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2004;64:696–703. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-2404. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-2404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Hung JY, Hsu YL, Li CT, Ko YC, Ni WC, Huang MS, et al. 6-Shogaol, an active constituent of dietary ginger, induces autophagy by inhibiting the AKT/mTOR pathway in human non-small cell lung cancer A549 cells. J Agric Food Chem. 2009;57:9809–16. doi: 10.1021/jf902315e. doi: 10.1021/jf902315e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Tengchaisri T, Chawengkirttikul R, Rachaphaew N, Reutrakul V, Sangsuwan R, Sirisinha S. Antitumor activity of triptolide against cholangiocarcinoma growth in vitro and in hamsters. Cancer Lett. 1998;133:169–75. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(98)00222-5. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3835(98)00222-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Yang S, Chen J, Guo Z, Xu XM, Wang L, Pei XF, et al. Triptolide inhibits the growth and metastasis of solid tumors. Mol Cancer Ther. 2003;2:65–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Phillips PA, Dudeja V, McCarroll JA, Borja-Cacho D, Dawra RK, Grizzle WE, et al. Triptolide induces pancreatic cancer cell death via inhibition of heat shock protein 70. Cancer Res. 2007;67:9407–16. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Mujumdar N, Mackenzie TN, Dudeja V, Chugh R, Antonoff MB, Borja-Cacho D, et al. Triptolide induces cell death in pancreatic cancer cells by apoptotic and autophagic pathways. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:598–608. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.04.046. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.04.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Xiong HY, Guo XL, Bu XX, Zhang SS, Ma NN, Song JR, et al. Autophagic cell death induced by 5-FU in Bax or PUMA deficient human colon cancer cell. Cancer Lett. 2010;288:68–74. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2009.06.039. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2009.06.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Pal I, Parida S, Prashanth Kumar BN, Banik P, Kumar Dey K, Chakraborty S, et al. Blockade of autophagy enhances proapoptotic potential of BI-69A11, a novel Akt inhibitor, in colon carcinoma. Eur J Pharmacol. 2015;765:217–27. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2015.08.039. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2015.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Amaravadi RK, Lippincott-Schwartz J, Yin XM, Weiss WA, Takebe N, Timmer W, et al. Principles and current strategies for targeting autophagy for cancer treatment. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:654–66. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2634. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Choi KS. Autophagy and cancer. Exp Mol Med. 2012;44:109–20. doi: 10.3858/emm.2012.44.2.033. doi: 10.3858/emm.2012.44.2.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]