ABSTRACT

The acetogenic bacterium Acetobacterium woodii is able to grow by the oxidation of diols, such as 1,2-propanediol, 2,3-butanediol, or ethylene glycol. Recent analyses demonstrated fundamentally different ways for oxidation of 1,2-propanediol and 2,3-butanediol. Here, we analyzed the metabolism of ethylene glycol. Our data demonstrate that ethylene glycol is dehydrated to acetaldehyde, which is then disproportionated to ethanol and acetyl coenzyme A (acetyl-CoA). The latter is further converted to acetate, and this pathway is coupled to ATP formation by substrate-level phosphorylation. Apparently, the product ethanol is in part further oxidized and the reducing equivalents are recycled by reduction of CO2 to acetate in the Wood-Ljungdahl pathway. Biochemical data as well as the results of protein synthesis analysis are consistent with the hypothesis that the propane diol dehydratase (PduCDE) and CoA-dependent propionaldehyde dehydrogenase (PduP) proteins, encoded by the pdu gene cluster, also catalyze ethylene glycol dehydration to acetaldehyde and its CoA-dependent oxidation to acetyl-CoA. Moreover, genes encoding bacterial microcompartments as part of the pdu gene cluster are also expressed during growth on ethylene glycol, arguing for a dual function of the Pdu microcompartment system.

IMPORTANCE Acetogenic bacteria are characterized by their ability to use CO2 as a terminal electron acceptor by a specific pathway, the Wood-Ljungdahl pathway, enabling in most acetogens chemolithoautotrophic growth with H2 and CO2. However, acetogens are very versatile and can use a wide variety of different substrates for growth. Here we report on the elucidation of the pathway for utilization of ethylene glycol by the model acetogen Acetobacterium woodii. This diol is degraded by dehydration to acetaldehyde followed by a disproportionation to acetate and ethanol. We present evidence that this pathway is catalyzed by the same enzyme system recently described for the utilization of 1,2-propanediol. The enzymes for ethylene glycol utilization seem to be encapsulated in protein compartments, known as bacterial microcompartments.

INTRODUCTION

In the absence of other energetically more favorable electron acceptors, CO2 is the only electron acceptor used for energy conservation in anoxic ecosystems. Only two groups of organisms are able to utilize CO2 as a terminal electron acceptor, namely, methanogenic archaea and acetogenic bacteria. Acetogenic bacteria are a specialized group of strictly anaerobic bacteria that, in most cases, can use molecular hydrogen as an electron donor for CO2 reduction and can thus grow autotrophically with H2 and CO2. Therefore, they reduce two molecules of CO2 to acetyl coenzyme A (acetyl-CoA) via the reductive acetyl-CoA pathway (the Wood-Ljungdahl pathway [WLP]) (1–3). This pathway of CO2 fixation also provides energy for growth by a chemiosmotic mechanism: an electrochemical ion gradient is established in the course of CO2 reduction (4–6) and can be used by an ATP synthase to drive the phosphorylation of ADP (7, 8). The nature of the coupling ion can be either H+ (5) or Na+ (4). In the Na+-dependent model organism Acetobacterium woodii, a membrane-bound Fd2−:NAD+ oxidoreductase, most likely encoded by the rnf genes, uses the exergonic electron transfer from reduced ferredoxin to NAD+ to drive the export of Na+ (9, 10). A. woodii, like most acetogens, can use molecular hydrogen as the electron donor for the reduction of CO2 and can also grow autotrophically. The thermodynamically unfavorable reduction of ferredoxin with H2 as a reductant is catalyzed by an electron-bifurcating hydrogenase that transfers electrons from molecular hydrogen in equal amounts to NAD+ and ferredoxin (11).

Whereas methanogens are restricted to the use of H2 and CO2, some C1 substrates, and acetate as growth substrates, acetogenic bacteria are metabolically more versatile and can also grow chemoorganoheterotrophically. Alternative energy and carbon sources can be several sugars, alcohols, acids, or methyl groups (12–14). Under most of these conditions, the energy and carbon sources are oxidized and the electrons generated are funneled to CO2, which is reduced in the WLP to acetate. However, some substrates are disproportionated, and thus, there is no need for CO2 reduction. Nonacetogenic growth on cinnamate derivatives (e.g., ferulate or sinapate) was already discovered in 1981 (12), and recently, we discovered that the model acetogen A. woodii also grows nonacetogenically on 1,2-propanediol (1,2-PD). This substrate is dehydrated to propionaldehyde, which is eventually disproportionated to form propionate and propanol. This fermentation does not involve CO2 reduction, and ATP is synthesized by substrate-level phosphorylation only (15). The degradation of 1,2-PD was shown to involve the formation of bacterial microcompartments, and these compartments were also present when growing on other alcohols, such as 2,3-butanediol (2,3-BD) (15). However, 2,3-BD metabolism follows another scheme. It is not dehydrated but is oxidized to acetoin, which is then split into acetaldehyde and acetyl-CoA. Both are converted into acetate. The electrons are then channeled into the WLP to reduce CO2 (16). Thus, whether or not oxidation of a diol is coupled to the WLP cannot be generalized and depends on the substrate. Another diol of biotechnological interest that A. woodii can grow on is ethylene glycol (17). The metabolism of ethylene glycol has not been studied in great detail in acetogens in general (13, 18) and in A. woodii in particular. Theoretically, there are various options for metabolic routes for the acetogenic as well as the nonacetogenic conversion of ethylene glycol. Here, we have addressed this question and present a pathway for ethylene glycol oxidation in A. woodii based on physiological and biochemical data.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Growth conditions.

Acetobacterium woodii DSM 1030 was cultivated under anaerobic conditions at 30°C. Complex medium was prepared as described previously (4). Ethylene glycol (50 mM) or fructose (20 mM) was used as the substrate. All cultivations were performed under an N2-CO2 (80%/20% [vol/vol]) atmosphere. Growth was followed by measuring the optical density (OD) at 600 nm (OD600). As specified below, the optical density was either measured directly in Hungate tubes without dilution in a visible (Vis) spectrophotometer (Spectronic 200; Thermo Scientific, Germany) or after taking 1-ml samples that were appropriately diluted before measuring the OD in cuvettes with a 1-cm light path. Samples were reduced with sodium dithionite to avoid interference with resazurin.

Preparation of cell suspensions.

All buffers and the medium were prepared using the anaerobic techniques described previously (19, 20). All preparation steps were performed at room temperature under strictly anoxic conditions in an anaerobic chamber (Coy Laboratory Products, Grass Lake, MI) filled with 95 to 98% N2 and 2 to 5% H2. A. woodii was grown with ethylene glycol as the substrate to an OD600 of 0.7 to 0.8, harvested by centrifugation (8,000 × g, 10 min), washed, and resuspended in imidazole buffer (50 mM imidazole-HCl, 20 mM MgSO4, 20 mM KCl, 2 mM dithioerythritol [DTE], 4 μM resazurin, pH 7.0). The protein concentration of the cell suspension was determined as described previously (21). The gas phase of the cell suspension was changed to 100% N2, and the cells were stored on ice until use. For analysis of ethylene glycol degradation, 100-ml serum flasks (containing a 100% N2 atmosphere at 0.5 × 105 Pa) were filled with 10 ml imidazole buffer containing 20 mM ethylene glycol. If indicated, 20 mM NaCl and/or 60 mM KHCO3 was added. The gas phase of the cell suspensions containing 60 mM KHCO3 was changed to 0.5 × 105 Pa N2-CO2 (80%/20% [vol/vol]). All experiments were performed at 30°C and started by addition of cell suspensions at a final concentration of 1 mg/ml. For the determination of the substrate and product pool, samples were taken at the time points indicated below, the cells were removed by centrifugation (14,000 × g, 1 min), and the supernatant was stored at −20°C for further analysis.

Determination of ethylene glycol, acetate, and ethanol.

Samples of 400 μl were mixed with 50 μl of 2 M phosphoric acid and 500 μl of 13.6 M acetone. As an internal standard, 50 μl of 200 mM 1-propanol was added. The samples were analyzed by gas chromatography on a Clarus 580 gas chromatograph (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA) with an Elite-FFAP capillary column (30 m by 0.32 mm; PerkinElmer). The following temperature profile was used: 60°C for 3 min followed by a temperature gradient to 165°C at 10°C/min. Ethylene glycol, acetate, and ethanol were analyzed with a flame ionization detector at 250°C. The peak areas were proportional to the concentration of each substance and calibrated with standard curves.

Preparation of cell extract.

A. woodii was cultivated with either fructose or ethylene glycol and harvested as described above for the preparation of the cell suspensions. Cells were washed in washing buffer (25 mM Tris HCl, 420 mM sucrose, 2 mM DTE, 4 μM resazurin, pH 7.5), resuspended in 20 ml washing buffer containing 5 mg/ml lysozyme, and incubated at 37°C for 60 min. Afterwards, the cells were sedimented by centrifugation (8,000 × g, 10 min), resuspended in 3 ml lysis buffer (25 mM Tris HCl, 20 mM MgSO4, 2 mM DTE, 4 μM resazurin, pH 7.5), and disrupted by two passages through a French press (SLM Aminco; SLM Instruments, USA) at 100 MPa. Intact cells and cell debris were removed by centrifugation, and the supernatant was stored at 4°C for further analysis. To remove the remaining H2 from the anaerobic chamber, the gas phase of the cell extract was changed to 100% N2.

Measurement of enzymatic activities.

All enzymatic measurements were carried out in 1.8-ml cuvettes (Glasgerätebau Ochs, Bovenden-Lenglern, Germany) that contained 1 ml buffer in a 100% N2 atmosphere and that were sealed with rubber stoppers. Measurements were performed at 30°C using a UV/Vis spectrometer (Uvikon XL; Bio-Tek Instruments, Neufahrn, Germany). Alcohol dehydrogenase activity was measured by determination of the acetaldehyde-dependent oxidation of NADH at 340 nm (ε = 6.2 mM−1 cm−1) in buffer containing 0.1 M Na4P2O7, 20 mM MgSO4, 22 mM glycine, 4 μM resazurin, pH 9.0. Then, 0.5 mM NADH and 10 mM acetaldehyde were added to the assay mixture. CoA-dependent aldehyde dehydrogenase activity was measured by determination of the acetaldehyde-dependent reduction of NAD at 340 nm in buffer containing 33.15 mM K2HPO4, 1.85 mM KH2PO4, 50 mM KCl, 2 mM DTE, 4 μM resazurin, pH 8.0. Then, 1.8 mM NAD, 0.2 mM CoA, and 10 mM acetaldehyde were added to the assay mixture. Formate dehydrogenase (hydrogen-dependent CO2 reductase [HDCR]), Rnf, and CO dehydrogenase (CODH) activities were measured as described previously (22, 23).

Analytical methods.

Protein concentrations were measured as described by Bradford (24). For Western blot analysis, the preparation of the samples was performed as described previously (25). Proteins were separated on 12% polyacrylamide gels. Gel staining was performed with Coomassie brilliant blue G250.

Calculations.

Determination of the kinetic parameters maximal enzyme velocity (Vmax) and Michaelis constant (Km) was performed with GraphPad Prism (version 4.03) software. Curve fittings were performed by using a nonlinear fit of the Michaelis-Menten equation.

RESULTS

Growth of A. woodii on ethylene glycol.

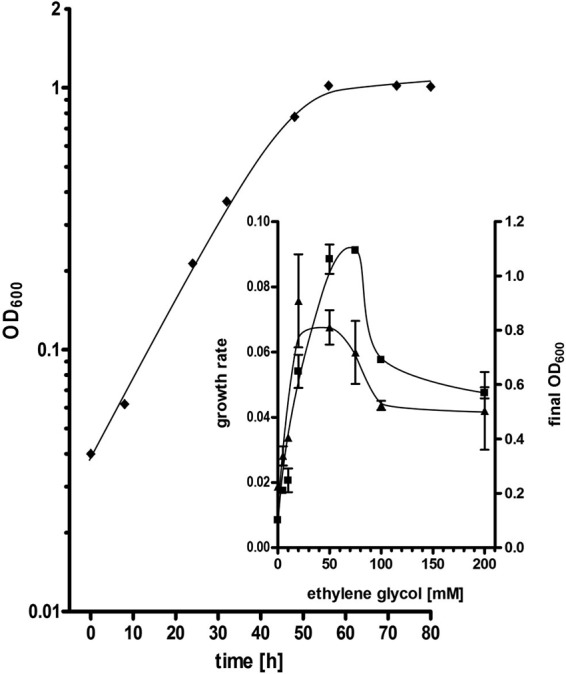

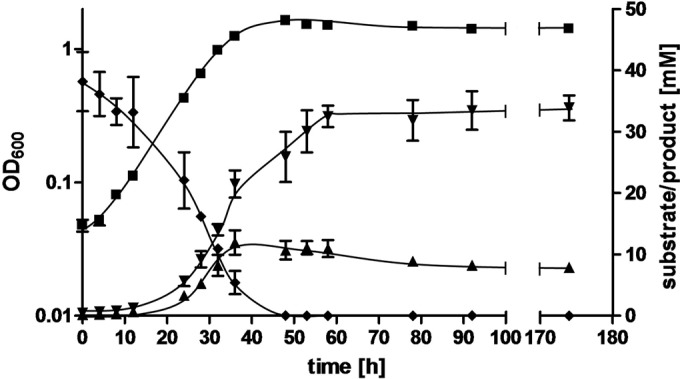

A. woodii was transferred on carbonate-buffered complex medium containing 20 mM ethylene glycol from a preculture grown on fructose. After three transfers, the growth rate increased from 0.03 ± 0.004 h−1 to 0.07 ± 0.007 h−1, indicating that the cells had adapted to this substrate. The growth of A. woodii on ethylene glycol was further characterized with an adapted culture. Under optimal conditions, ethylene glycol allowed the growth of A. woodii DSM 1030 up to a final optical density at 600 nm of 1.1 ± 0.01 within 55 h with an optimal substrate concentration of 75 mM ethylene glycol (Fig. 1, inset). A reduction as well as an increase in the substrate concentration resulted in reduced final optical densities. At 50 mM ethylene glycol, the growth rate was 0.07 ± 0.01 h−1. Again, an increase or decrease in the ethylene glycol concentration resulted in a decrease in the growth rate (Fig. 1, inset). Analysis of the final product pool revealed that 40 mM ethylene glycol was converted to 33.5 ± 3.1 mM acetate as well as 8.2 ± 0.3 mM ethanol. Time course determination of the products revealed a biphasic behavior. In the first phase during exponential growth, ethylene glycol was converted to acetate and ethanol in a roughly 2:1 stoichiometry (product concentrations, 5.7 mM acetate and 3.3 mM ethanol determined in the mid-exponential growth phase and 21.5 mM acetate and 11.9 mM ethanol determined in the end-exponential growth phase) (Fig. 2). The culture reached the stationary growth phase after ethylene glycol was completely consumed. In this phase, the ethanol concentration decreased and acetate was still produced as the sole end product. During this second production phase, about 3 mM ethanol was consumed and 8 mM acetate was produced. This amount of acetate is possible only if, in addition to ethanol, CO2 is converted to acetate in the WLP. The emergence of the complete amount of carbon in the products (41.7 mM C2 products from 40 mM C2 substrate) can be explained only if additional carbon from CO2 was converted to biomass.

FIG 1.

Growth of A. woodii on ethylene glycol. A. woodii DSM 1030 was cultivated at 30°C in 5 ml CO2-bicarbonate-buffered medium containing 50 mM ethylene glycol under an N2-CO2 (80%/20% [vol/vol]) atmosphere. Growth was followed by measuring the OD at 600 nm in Hungate tubes. The results of one representative experiment are shown. (Inset) Dependence of the growth rate (▲) and the final OD600 (■) on the ethylene glycol concentration. Final OD600 values and growth rates are averages from two independent biological experiments.

FIG 2.

Degradation of ethylene glycol by growing cells of A. woodii. A. woodii DSM 1030 was cultivated at 30°C in 50 ml CO2-bicarbonate-buffered medium containing 40 mM ethylene glycol under an atmosphere of N2-CO2 (80%/20% [vol/vol]). Growth was followed by measuring the OD at 600 nm of samples taken from a 1-liter-flask (■). The concentrations of ethylene glycol (◆), acetate (▼), and ethanol (▲) were determined by gas chromatography. Acetaldehyde could not be detected. All data points are means ± SEMs (n = 3 independent experiments).

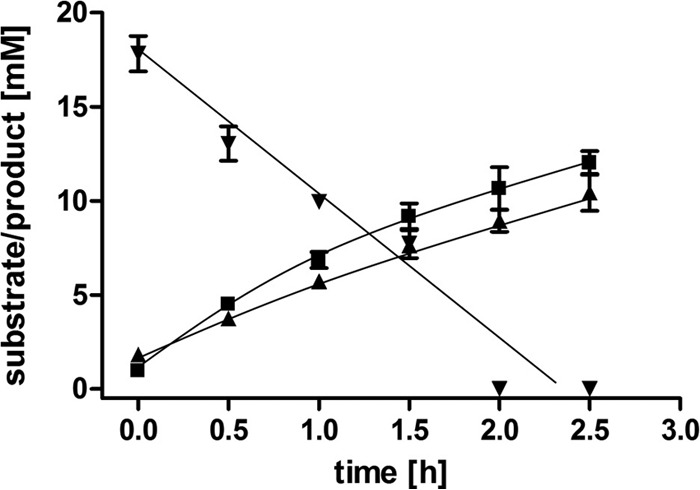

Resting cells of A. woodii convert ethylene glycol to equal amounts of acetate and ethanol.

In order to unravel the ethylene glycol metabolism in A. woodii in more detail, we analyzed the product pool during oxidation of ethylene glycol by suspensions of resting cells. These experiments allowed the determination of the stoichiometry between substrates and products without a bias of biomass formation. As evident from Fig. 3, 20 mM ethylene glycol was degraded within 2 h at an initial rate of 8.2 ± 0.6 μmol ethylene glycol mg−1 h−1. Concomitantly, ethanol and acetate were produced, with the final product concentrations being 12.0 ± 0.9 mM and 10.4 ± 1.4 mM, respectively. Initial formation rates were 4.8 ± 0.4 μmol ethanol mg−1 h−1 and 3.6 ± 0.2 μmol acetate mg−1 h−1. The conversion of ethylene glycol by resting cells resembles the conversion in the exponential phase by growing cells. The production of ethanol and acetate in nearly equal amounts indicates that ethylene glycol is disproportionated according to the equation

| (1) |

A closely related acetogen, Acetobacterium carbinolicum, oxidizes ethylene glycol to acetate (13) according to the equation

| (2) |

followed by disposal of the reducing equivalents by reduction of CO2 to acetate in the WLP according to the equation

| (3) |

In sum, this results in substrate conversion according to the equation

| (4) |

The observed conversion by resting cells of A. woodii argues against this mode of ethylene glycol utilization and against an involvement of the WLP. Consistent with this hypothesis is the finding that the conversion of ethylene glycol did not depend on the presence of either CO2-bicarbonate or Na+ (data not shown), both of which are essential for the WLP in A. woodii. In both cases, ethylene glycol was disproportionated to almost equal amounts of ethanol and acetate.

FIG 3.

Degradation of ethylene glycol by resting cells of A. woodii goes along with the formation of acetate and ethanol. Resting cells (1 mg/ml) of A. woodii were incubated in 10 ml imidazole buffer (50 mM imidazole, 20 mM KCl, 50 mM MgSO4, 2 mM DTE, 4 μM resazurin, pH 7.0) containing 20 mM ethylene glycol in a 100% N2 atmosphere at 30°C. The concentrations of ethylene glycol (▼), acetate (▲), and ethanol (■) were determined by gas chromatography. Acetaldehyde could not be detected under the conditions tested. All data points are means ± SEMs (n = 3 independent experiments).

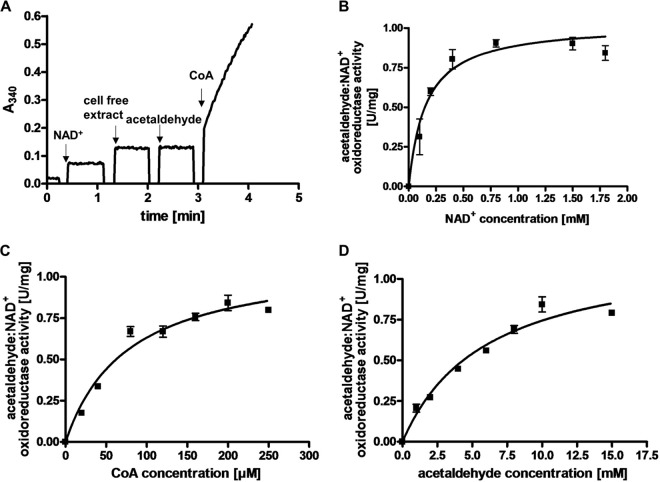

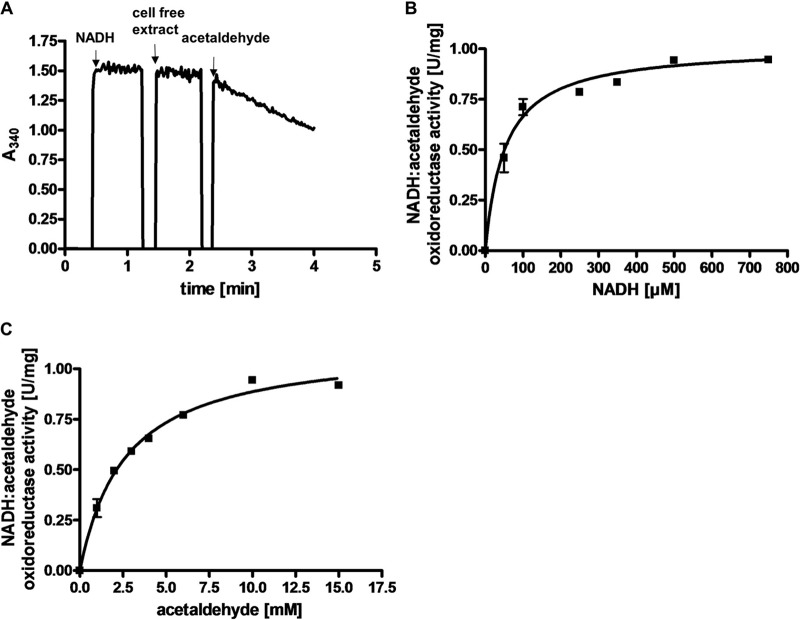

The disproportionation of ethylene glycol resembles the utilization of another diol, 1,2-propanediol (1,2-PD), by A. woodii (15). In this pathway, 1,2-PD is first dehydrated to propionaldehyde followed by an oxidation to propionyl-CoA and conversion to propionate via propionyl-phosphate. The reduced electron carrier NADH is recycled by reduction of a second propionaldehyde to propanol. Growth on 1,2-PD is accompanied by the formation of bacterial microcompartments, proposed to include the 1,2-PD degradation pathway to protect the cell from the toxic intermediate propionaldehyde. Likewise, ethylene glycol could be dehydrated to acetaldehyde to form the observed products ethanol and acetate. There is only one dehydratase encoded by the genome of A. woodii, and it is annotated PduCDE. This protein is encoded by the pdu gene cluster (Awo_c25780 to Awo_c25910), which has previously been shown to encode not only this dehydratase but also a CoA-dependent aldehyde dehydrogenase and proteins building the bacterial microcompartment. Western blot analysis with antibodies against subunit PduC of the dehydratase actually revealed that this protein is produced not only in 1,2-PD-grown cells (15) but also in ethylene glycol-grown cells (Fig. 4A). This shows that the pdu gene cluster is also expressed in ethylene glycol-grown cells and that the same enzyme machinery responsible for 1,2-PD utilization could convert ethylene glycol to the observed end products. Indeed, resting cells of A. woodii grown on 1,2-PD were also able to use ethylene glycol: 20 mM ethylene glycol was converted to equal amounts of ethanol and acetate. However, ethylene glycol was utilized much more slowly. Ethylene glycol in 1,2-PD-grown cells decreased at a rate of 1.5 ± 0.1 μmol mg−1 h−1, whereas it decreased at a rate of 8.2 ± 0.6 μmol mg−1 h−1 in ethylene glycol-grown cells. Consistent with the proposed reaction scheme of ethylene glycol utilization, we were able to detect an acetaldehyde-dependent reduction of NAD+ in extracts of ethylene glycol-grown cells, which was also strictly dependent on the presence of CoA (Fig. 5A). The specific activity of the reaction was 0.9 ± 0.1 U/mg, the dependence on acetaldehyde, CoA, and NAD+ followed Michaelis-Menten kinetics (Fig. 5B to D), and the apparent Km values were determined to be 6 ± 1.1 mM for acetaldehyde, 77.1 ± 13.5 μM for CoA, and 160 ± 3 μM for NAD+. A CoA-dependent acetaldehyde dehydrogenase is also encoded by the pdu cluster (PduP), and Western blot analysis revealed that the production of PduP is induced by ethylene glycol (Fig. 4B). These data are fully consistent with the hypothesis that the products of the pdu gene cluster catalyze not only 1,2-PD disproportionation but also ethylene glycol disproportionation. Since the second end product of the ethylene glycol conversion was shown to be ethanol, it was tested whether the extract of ethylene glycol-grown cells catalyzes an NADH-dependent reduction of acetaldehyde. Indeed, NADH was oxidized upon addition of acetaldehyde (Fig. 6A). The specific activity of the electron transfer was 1 ± 0.05 U/mg, and the dependence on NADH and acetaldehyde followed Michaelis-Menten kinetics (Fig. 6B and C). Km values were determined to be 52.1 ± 7.1 μM for NADH and 2.6 ± 0.2 mM for acetaldehyde. CoA-dependent acetaldehyde dehydrogenase and alcohol dehydrogenase activities were negligible in cells grown on fructose.

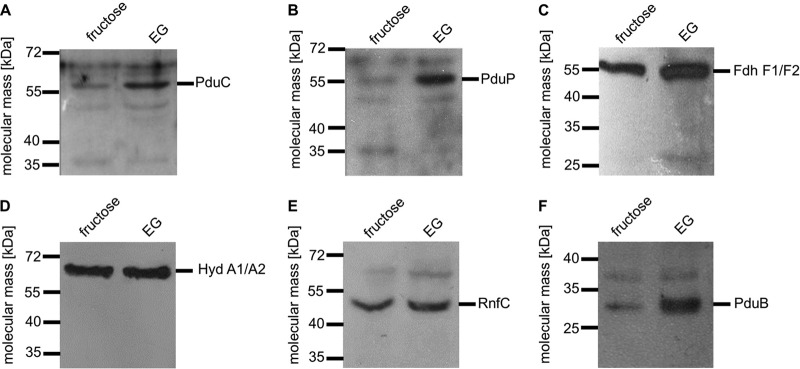

FIG 4.

Immunological determination of key enzymes of the WLP and ethylene glycol (EG) metabolism in cells grown on ethylene glycol or fructose. A. woodii was grown on either fructose or ethylene glycol and harvested in the mid-exponential growth phase. Whole-cell extracts were separated on a 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gel. The presence of PduC (A), PduP (B), FdhF (C), HydA (D), RnfC (E), and PduB (F) was determined immunologically.

FIG 5.

Characterization of the CoA-dependent acetaldehyde:NAD+ oxidoreductase activity in extracts of A. woodii cells grown on ethylene glycol. (A) Electron transfer from acetaldehyde to NAD+ in the cell extract was measured in a 100% N2 atmosphere at 30°C in buffer containing 33.15 mM K2HPO4, 1.85 mM KH2PO4 (pH 8.0), 50 mM KCl, 2 mM DTE, and 4 μM resazurin. NAD+, CoA, and acetaldehyde were added to concentrations of 1.8, 0.2, and 10 mM, respectively. Michaelis-Menten kinetics for NAD+ (B), CoA (C), and acetaldehyde (D) are shown. All data points are means ± SEMs (n = 3 independent experiments).

FIG 6.

Characterization of the NADH:acetaldehyde oxidoreductase activity in extract of A. woodii cells grown on ethylene glycol. (A) Electron transfer from NADH to acetaldehyde in cell extracts was measured in a 100% N2 atmosphere at 30°C in buffer containing 0.1 M Na4P2O7, 20 mM MgSO4, 22 mM glycine, 2 mM DTE, pH 9.0. NADH and acetaldehyde were added to concentrations of 0.5 and 10 mM, respectively. Michaelis-Menten kinetics for NADH (B) and acetaldehyde (C) are shown. All data points are means ± SEMs (n = 3 independent experiments).

As mentioned above, ethylene glycol conversion in growing cells showed a biphasic behavior, with a first phase of ethylene glycol disproportionation being followed by a phase of production of acetate as the sole end product, and the degradation of ethanol. A. woodii is able to grow by the conversion of ethanol to acetate according to the equation

| (5) |

(13, 26, 27). We therefore conclude that ethylene glycol utilization starts by the disproportionation to acetate and ethanol as seen here. The ethanol produced is reoxidized in a second step to form acetate. The reducing equivalents are channeled to the WLP to reduce CO2 to acetate. This is most pronounced when ethylene glycol is depleted and acetate formation continues. To further confirm this conclusion, the enzymatic activities of some of the enzymes involved in the WLP and the concomitant energy conservation were measured in cells grown on either fructose or ethylene glycol. In ethylene glycol-grown cells, the activities of CO dehydrogenase (CODH), the Rnf complex, as well as the hydrogen-dependent CO2 reductase (HDCR) were only slightly reduced compared to their activities in fructose-grown cells. With fructose as the substrate, a third of the product is generated via the WLP. The activities measured in extracts of ethylene glycol-grown cells were 74% (Rnf), 75% (CODH), and 67% (HDCR) of the activities measured in extracts of fructose-grown cells. In addition, immunological detection of important enzymes for the conversion of CO2 to acetate, HDCR, electron-bifurcating hydrogenase HydABCD, and RnfC showed comparable enzyme levels in ethylene glycol-grown cells and fructose-grown cells (Fig. 4C to E).

The pdu gene cluster contains genes coding for enzymes as well as for shell proteins of bacterial microcompartments. As recently shown, the expression of the shell proteins correlates with the presence of bacterial microcompartments in the cytoplasm of A. woodii (15). Finally, we tested for the presence of the shell protein PduB by immunological detection, and again, as observed for 1,2-PD, the level of the shell protein was increased in cells grown on ethylene glycol compared to the level in cells grown on fructose (Fig. 4F).

DISCUSSION

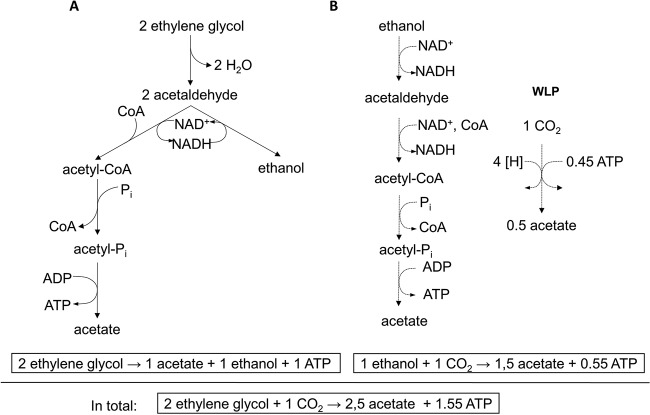

Acetogenic bacteria are characterized by their ability to use a variety of electron donors to reduce two molecules of CO2 to acetate via the WLP. Recently, we showed that the model acetogen A. woodii oxidizes the diol 2,3-BD to form acetate and the resulting reducing equivalents are channeled into the WLP to form another acetate via CO2 reduction (16). In contrast, the diol 1,2-PD is disproportionated by a bacterial microcompartment-dependent metabolism to equal amounts of propionate and propanol, thus favoring this reaction over the WLP-dependent disposal of reducing equivalents by the reduction of CO2 (15). The diol ethylene glycol was reported to enable the growth of A. woodii strain NZva16, and this strain was shown to convert ethylene glycol solely to acetate with 100% carbon recovery (17). In the present study, we show that the degradation of ethylene glycol by A. woodii DSM 1030 shows a biphasic behavior. The alcohol is first disproportionated to ethanol and acetate (Fig. 7A), and this is followed by a phase of acetate production from ethanol (Fig. 7B).

FIG 7.

Model of ethylene glycol metabolism in A. woodii. For explanations, see the text. (A) Initial disproportionation of ethylene glycol to acetate and ethanol; (B) the following oxidation of ethanol to acetate (27). Note that the WLP requires H2, Fd2−, and NADH as reductant. Reduction of ferredoxin with NADH as reductant catalyzed by the Rnf complex requires reverse electron transfer, which is driven by the electrochemical sodium potential that is established by ATP hydrolysis (27). Here, 0.45 mol of ATP has to be hydrolyzed to drive the reaction.

As elucidated, the enzymes that catalyze the degradation of ethylene glycol in A. woodii are presumably the same ones that were already shown to mediate the conversion of 1,2-PD to propionate and propanol, and this hypothesis is strengthened further when the kinetic parameters determined for the conversion of the intermediates of both pathways are compared: the conversion of propionaldehyde to propionyl-CoA in 1,2-PD degradation is catalyzed by the CoA-dependent aldehyde dehydrogenase PduP. It was shown that propionaldehyde conversion occurred at a rate of 3 U/mg. However, cells grown on 1,2-PD converted not only propionaldehyde but also acetaldehyde (an intermediate of the ethylene glycol degradation pathway) at a rate of 1 U/mg (15). The very same rate (0.9 U/mg) was observed here when extracts of cells grown on ethylene glycol converted acetaldehyde to acetyl-CoA. Also, the apparent Km values determined on both diols for the substrates CoA and NAD+, as well as the respective aldehyde, are very much alike (120 μM for CoA, 400 μM for NAD+, and 8 mM for propionaldehyde in 1,2-PD grown cells [15], compared to values of 77 μM for CoA, 160 μM for NAD+, and 6 mM for acetaldehyde in ethylene glycol-grown cells). Similarly, both in 1,2-PD-grown cells and in ethylene glycol-grown cells, an NAD-dependent alcohol dehydrogenase activity is significantly induced. The identity of the alcohol dehydrogenase in 1,2-PD-grown cells is still unsolved, and a gene coding for such an enzyme is missing in the pdu gene cluster.

In contrast to growth on 1,2-PD, where the conversion stops at the products propionate and propanol, the conversion of ethylene glycol starts with a disproportionation, as described above, but the product ethanol is oxidized in a second step to acetate, accompanied by CO2 reduction to acetate. The ethanol metabolism in A. woodii was recently characterized (27). Ethanol is first oxidized to acetate, and the reducing equivalents are used to reduce 2 molecules of CO2 to 1 molecule of acetate via the WLP. One of the key enzymes of ethanol metabolism is the bifunctional AdhE. This enzyme catalyzes the oxidation of ethanol to acetaldehyde and also the CoA-dependent oxidation of acetaldehyde to acetyl-CoA. AdhE was present in cells grown on ethanol as well as in ethylene glycol-grown cells but not in 1,2-propanediol-grown cells. Therefore, AdhE is also apparently involved in ethylene glycol metabolism. It may catalyze the disproportionation of acetaldehyde to acetyl-CoA and ethanol and, additionally, the oxidation of ethanol to acetyl-CoA after ethylene glycol is completely consumed. The enzymatic characterization, however, revealed in the absence of CoA a high Km value of 40 mM for ethanol, which indicates that ethanol oxidation may proceed very slowly at lower ethanol concentrations. That can be one reason why A. woodii could not completely consume the produced ethanol. The biphasic metabolism is supported by the observed stoichiometry of the products during growth, especially a carbon recovery of over 100% and the continued production of acetate when ethylene glycol is depleted. For a complete carbon recovery, CO2 needs to be fixed to explain the formed biomass. In addition, enzyme activities and immunological analysis proved the presence of the enzymes of the WLP.

Summing up, our data are consistent with the metabolic pathway shown in Fig. 7: ethylene glycol is initially dehydrated to acetaldehyde. Since the PduC subunit of the 1,2-propanediol dehydratase PduCDE is produced in ethylene glycol-grown cells and this is the only dehydratase encoded by the genome of A. woodii, the initial conversion of ethylene glycol is most likely catalyzed by this enzyme, which is also responsible for the initial dehydration of 1,2-PD (15). This is similar to ethylene glycol fermentation in the strict anaerobe Clostridium glycolicum (28). This organism disproportionates ethylene glycol and 1,2-PD into the corresponding acid and alcohol utilizing one dehydratase specific for both 1,2-PD and ethylene glycol in the first step (29). The first intermediate of ethylene glycol degradation following dehydration is acetaldehyde. Extracts of ethylene glycol-grown cells of A. woodii can either reduce acetaldehyde using NADH or oxidize the same in a CoA-dependent reaction, thereby transferring electrons onto NAD+. Thus, acetaldehyde is disproportionated to form equal amounts of both ethanol and acetyl-CoA. The oxidation of acetaldehyde is probably catalyzed by a CoA-dependent aldehyde dehydrogenase, PduP, whereas the production of ethanol might be performed by a yet-to-be identified alcohol dehydrogenase. Ethanol is further converted as described in reference 27 by oxidation to acetate coupled with the reduction of CO2 to acetate.

Growth on ethylene glycol as the sole carbon and energy source has been described for many aerobic and anaerobic organisms, despite the fact that it is not usually found in soil or waste samples. However, Asiatic clams as well as the fungus Tricholoma matsutake were reported to produce ethylene glycol (30, 31), and it is also known to be a product of ethylene metabolism in a number of higher plants (32). Whereas many aerobic bacteria utilize ethylene glycol by oxidation to glycolaldehyde and glycolate followed by an oxidase reaction to glyoxylate (33–36), anaerobic bacteria use the alternative route via the acetaldehyde resulting from ethylene glycol dehydration catalyzed by the very oxygen-sensitive diol dehydratase (13, 28, 29). As recently shown, growth on 1,2-PD leads to the formation of bacterial microcompartments in the cytoplasm of Acetonema longum and A. woodii cells (15, 37). In a previous study (15), we also demonstrated the presence of the microcompartment shell proteins of the PDU1 core locus (38) in comparable amounts in cells grown on ethylene glycol. This is in accordance with the model that ethylene glycol degradation is catalyzed by the same enzyme machinery described here. Encapsulation of a pathway for ethylene glycol degradation into microcompartments has, to our knowledge, not been reported before. Protection from the toxic intermediate acetaldehyde might necessitate this encapsulation. In A. woodii, the bacterial microcompartment might be a more general mechanism for protection from toxic aldehydes, as is obvious from the dual function of the microcompartments for 1,2-PD and ethylene glycol degradation. In addition, synthesis of a microcompartment shell protein has been observed in A. woodii cells grown on ethanol, 2,3-butanediol, and, to a lesser extent, fructose and H2 and CO2, all of which, except for H2 and CO2, are substrates that lead to small amounts of ethanol or aldehyde intermediates (16, 26, 27).

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by a grant from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft.

REFERENCES

- 1.Drake HL. 1994. Acetogenesis, acetogenic bacteria, and the acetyl-CoA pathway: past and current perspectives, p 3–60. In Drake HL. (ed), Acetogenesis. Chapman and Hall, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Müller V. 2003. Energy conservation in acetogenic bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol 69:6345–6353. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.11.6345-6353.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ragsdale SW, Pierce E. 2008. Acetogenesis and the Wood-Ljungdahl pathway of CO2 fixation. Biochim Biophys Acta 1784:1873–1898. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2008.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heise R, Müller V, Gottschalk G. 1989. Sodium dependence of acetate formation by the acetogenic bacterium Acetobacterium woodii. J Bacteriol 171:5473–5478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hugenholtz J, Ljungdahl LG. 1989. Electron transport and electrochemical proton gradient in membrane vesicles of Clostridium thermoaceticum. J Bacteriol 171:2873–2875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schuchmann K, Müller V. 2014. Autotrophy at the thermodynamic limit of life: a model for energy conservation in acetogenic bacteria. Nat Rev Microbiol 12:809–821. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heise R, Müller V, Gottschalk G. 1992. Presence of a sodium-translocating ATPase in membrane vesicles of the homoacetogenic bacterium Acetobacterium woodii. Eur J Biochem 206:553–557. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb16959.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ivey DM, Ljungdahl LG. 1986. Purification and characterization of the F1-ATPase from Clostridium thermoaceticum. J Bacteriol 165:252–257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Biegel E, Müller V. 2010. Bacterial Na+-translocating ferredoxin:NAD+ oxidoreductase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107:18138–18142. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010318107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Biegel E, Schmidt S, González JM, Müller V. 2011. Biochemistry, evolution and physiological function of the Rnf complex, a novel ion-motive electron transport complex in prokaryotes. Cell Mol Life Sci 68:613–634. doi: 10.1007/s00018-010-0555-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schuchmann K, Müller V. 2012. A bacterial electron bifurcating hydrogenase. J Biol Chem 287:31165–31171. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.395038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bache R, Pfennig N. 1981. Selective isolation of Acetobacterium woodii on methoxylated aromatic acids and determination of growth yields. Arch Microbiol 130:255–261. doi: 10.1007/BF00459530. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eichler B, Schink B. 1984. Oxidation of primary aliphatic alcohols by Acetobacterium carbinolicum sp. nov., a homoacetogenic anaerobe. Arch Microbiol 140:147–152. doi: 10.1007/BF00454917. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Drake HL, Gößner AS, Daniel SL. 2008. Old acetogens, new light. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1125:100–128. doi: 10.1196/annals.1419.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schuchmann K, Schmidt S, Martinez Lopez A, Kaberline C, Kuhns M, Lorenzen W, Bode HB, Joos F, Müller V. 2015. Nonacetogenic growth of the acetogen Acetobacterium woodii on 1,2-propanediol. J Bacteriol 197:382–391. doi: 10.1128/JB.02383-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hess V, Oyrik O, Trifunovic D, Müller V. 2015. 2,3-Butanediol metabolism in the acetogen Acetobacterium woodii. Appl Environ Microbiol 81:4711–4719. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00960-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schink B, Stieb M. 1983. Fermentative degradation of polyethylene glycol by a strictly anaerobic, gram-negative, nonsporeforming bacterium, Pelobacter venetianus sp. nov. Appl Environ Microbiol 45:1905–1913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eichler B, Schink B. 1985. Fermentation of primary alcohols and diols and pure culture of syntrophically alcohol-oxidizing anaerobes. Arch Microbiol 143:60–66. doi: 10.1007/BF00414769. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hungate RE. 1969. A roll tube method for cultivation of strict anaerobes. Methods Microbiol 3b:117–132. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bryant MP. 1972. Commentary on the Hungate technique for culture of anaerobic bacteria. Am J Clin Nutr 25:1324–1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schmidt K, Liaaen-Jensen S, Schlegel HG. 1963. Die Carotinoide der Thiorhodaceae. Arch Mikrobiol 46:117–126. doi: 10.1007/BF00408204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schuchmann K, Müller V. 2013. Direct and reversible hydrogenation of CO2 to formate by a bacterial carbon dioxide reductase. Science 342:1382–1385. doi: 10.1126/science.1244758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hess V, Schuchmann K, Müller V. 2013. The ferredoxin:NAD+ oxidoreductase (Rnf) from the acetogen Acetobacterium woodii requires Na+ and is reversibly coupled to the membrane potential. J Biol Chem 288:31496–31502. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.510255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bradford MM. 1976. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantification of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem 72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hess V, Vitt S, Müller V. 2011. A caffeyl-coenzyme A synthetase initiates caffeate activation prior to caffeate reduction in the acetogenic bacterium Acetobacterium woodii. J Bacteriol 193:971–978. doi: 10.1128/JB.01126-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Buschhorn H, Dürre P, Gottschalk G. 1989. Production and utilization of ethanol by the homoacetogen Acetobacterium woodii. Appl Environ Microbiol 55:1835–1840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bertsch J, Siemund AL, Kremp F, Müller V. 16 October 2015. A novel route for ethanol oxidation in the acetogenic bacterium Acetobacterium woodii: the AdhE pathway. Environ Microbiol doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.13082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gaston LW, Stadtman ER. 1963. Fermentation of ethylene glycol by Clostridium glycolicum, sp. n. J Bacteriol 85:356–362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hartmanis MG, Stadtman TC. 1986. Diol metabolism and diol dehydratase in Clostridium glycolicum. Arch Biochem Biophys 245:144–152. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(86)90198-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee NE, Haag WR, Jolley RL. 1983. Cooling water pollutants: bioaccumulation by Corbicula, p 851–870. In Jolley RL, Brungs WA, Cotruvo JA, Cumming RB, Mattice JS, Jacobs VA (ed), Water chlorination: chemistry, environmental impact and health effects, vol 4 Ann Arbor Science Publishers, Ann Arbor, MI. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ahn JS, Lee KH. 1986. Studies on the volatile aroma components of edible mushroom (Tricholoma matsutake) of Korea. J Korean Soc Food Nutr 15:253–257. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Blomstrom DC, Beyer EM. 1980. Plants metabolise ethylene to ethylene glycol. Nature 283:66–68. doi: 10.1038/283066a0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mückschel B, Simon O, Klebensberger J, Graf N, Rosche B, Altenbuchner J, Pfannstiel J, Huber A, Hauer B. 2012. Ethylene glycol metabolism by Pseudomonas putida. Appl Environ Microbiol 78:8531–8539. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02062-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Caskey WH, Taber WA. 1981. Oxidation of ethylene glycol by a salt-requiring bacterium. Appl Environ Microbiol 42:180–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gonzalez CF, Taber WA, Zeitoun MA. 1972. Biodegradation of ethylene glycol by a salt-requiring bacterium. Appl Microbiol 24:911–919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Görisch H. 2003. The ethanol oxidation system and its regulation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Biochim Biophys Acta 1647:98–102. doi: 10.1016/S1570-9639(03)00066-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tocheva EI, Matson EG, Cheng SN, Chen WG, Leadbetter JR, Jensen GJ. 2014. Structure and expression of propanediol utilization microcompartments in Acetonema longum. J Bacteriol 196:1651–1658. doi: 10.1128/JB.00049-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Axen SD, Erbilgin O, Kerfeld CA. 2014. A taxonomy of bacterial microcompartment loci constructed by a novel scoring method. PLoS Comput Biol 10:e1003898. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]