ABSTRACT

The extremely halophilic archaeon Haloferax volcanii grows anaerobically by denitrification. A putative DNA-binding protein, NarO, is encoded upstream of the respiratory nitrate reductase gene of H. volcanii. Disruption of the narO gene resulted in a loss of denitrifying growth of H. volcanii, and the expression of the recombinant NarO recovered the denitrification capacity. A novel CXnCXCX7C motif showing no remarkable similarities with known sequences was conserved in the N terminus of the NarO homologous proteins found in the haloarchaea. Restoration of the denitrifying growth was not achieved by expression of any mutant NarO in which any one of the four conserved cysteines was individually replaced by serine. A promoter assay experiment indicated that the narO gene was usually transcribed, regardless of whether it was cultivated under aerobic or anaerobic conditions. Transcription of the genes encoding the denitrifying enzymes nitrate reductase and nitrite reductase was activated under anaerobic conditions. A putative cis element was identified in the promoter sequence of haloarchaeal denitrifying genes. These results demonstrated a significant effect of NarO, probably due to its oxygen-sensing function, on the transcriptional activation of haloarchaeal denitrifying genes.

IMPORTANCE H. volcanii is an extremely halophilic archaeon capable of anaerobic growth by denitrification. The regulatory mechanism of denitrification has been well understood in bacteria but remains unknown in archaea. In this work, we show that the helix-turn-helix (HTH)-type regulator NarO activates transcription of the denitrifying genes of H. volcanii under anaerobic conditions. A novel cysteine-rich motif, which is critical for transcriptional regulation, is present in NarO. A putative cis element was also identified in the promoter sequence of the haloarchaeal denitrifying genes.

INTRODUCTION

Many kinds of microorganisms are facultatively anaerobic, and they carry out energy conversion by anaerobic respiration or fermentation under low-oxygen-tension conditions. Denitrifying capability, which is one of the anaerobic respirations utilizing nitrate as the terminal electron acceptor, is widely distributed among bacteria, archaea, and eukaryotic fungi (1). In archaea, several species of halophilic euryarchaea and thermophilic crenarchaea have been reported to possess this anaerobic capability, carrying out denitrification during the nitrogen cycle in hypersaline or high-temperature environments, respectively (2–4).

Recent progress in the molecular and enzymatic characterization of haloarchaeal denitrification has clarified that, as with its bacterial counterpart, successive reduction steps catalyzed by the four redox enzymes, i.e., nitrate reductase, nitrite reductase, nitric oxide reductase, and probably nitrous oxide reductase, occur (2–4). Respiratory nitrate reductase was purified and cloned from three haloarchaea and was shown to be a unique hybrid enzyme in combination with a molybdenum protein possessing the respiratory cytochrome bc1 (5–10) (Fig. 1). The copper-containing nitrite reductase NirK has been isolated from Haloarcula marismortui (11). The norB and nosZ genes, which encode nitric oxide reductase and nitrous oxide reductase, respectively, were identified in the H. marismortui genome (12), although neither enzyme has been purified and characterized.

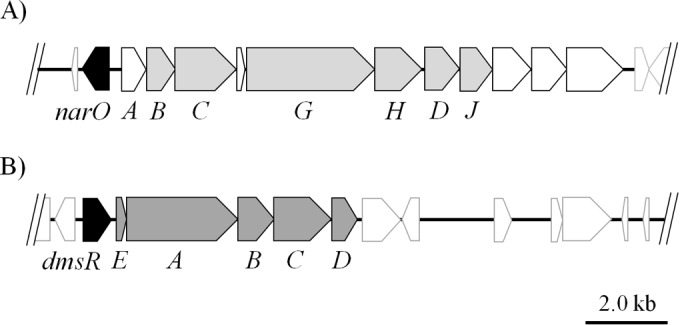

FIG 1.

Gene structures of nitrate reductase and DMSO/TMAO reductase in H. volcanii. A physical map of the nitrate reductase (A) and the DMSO reductase gene (B) loci in H. volcanii is shown. The directions of the open reading frames (ORFs) are indicated by arrows. The narO (HVO_B0159) and dmsR (HVO_B0361) genes, which are the probable transcription regulators of the nitrate reductase and DMSO reductase genes, respectively, are shown in black. In the nitrate reductase gene locus (A), 7 of 11 ORFs, shown in gray, are assigned to narABCGHDJ (HVO_B0160-0166), and their physiological roles in nitrate reduction were estimated, while the functions of the other four ORFs remain unknown (5, 8, 10). (B) The arrangement of the DMSO reductase gene, dmsEABCD (HVO_B0362-0366), in H. volcanii is identical to that in Halobacterium sp. NRC-1. The five ORFs are transcribed as a single mRNA in Halobacterium sp. NRC-1 (21).

In contrast to the progress in knowledge of the biochemistry of denitrification, the regulatory mechanism of this anaerobic respiration has remained unknown in haloarchaea. In Escherichia coli, a facultative anaerobic bacterium capable of nitrate respiration, transcription of the nitrate reductase gene is controlled by a global oxygen response regulator, FNR, and the two-component nitrate/nitrite sensor-transducer NarXL (13, 14). FNR, a DNA-binding protein that is a member of the cyclase-associated protein (CAP) family, harbors four conserved cysteines, which bind an oxygen-sensing iron-sulfur cluster and a helix-turn-helix (HTH) DNA-binding motif in its N and C termini, respectively (15, 16). Another oxygen-dependent transcription regulator has also been identified in root nodule bacteria: anaerobic metabolisms of these bacteria, including denitrification and nitrogen fixation, are activated via the oxygen-sensing two-component FixLJ-dependent regulatory cascade (17, 18). However, homologous proteins with FNR and FixJL are not present in archaea, suggesting the presence of another regulatory mechanism for denitrification in archaea.

In halophilic archaea, oxygen- and light-dependent induction of bacteriorhodopsin by the bacterioopsin activator (Bat) has been investigated (19). Bat involves both the PAS domain, a possible redox sensory motif, and the GAF domain, a light-responsive cyclic GMP (cGMP)-binding motif in the sequence (20). Stimulation by light and anaerobicity activate transcription of the bacterioopsin gene and functionally related genes via the Bat regulator. Halobacterium sp. strain NRC-1 is capable of anaerobic respiration by utilizing dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and/or trimethylamine oxide (TMAO) as an electron acceptor. A novel DNA-binding protein, DmsR, is encoded in the 5′ flank of the dmsEABCD genes that encode DMSO/TMAO reductase, a terminal enzyme of anaerobic respiration. Müller and DasSarma (21) and DasSarma et al. (22) reported that the ΔdmsR mutant lacks the ability to grow anaerobically by DMSO/TMAO respiration (Fig. 1). DmsR contains an HTH-type DNA-binding motif (Pfam HTH10) that is homologous with that of the Bat regulator in its C terminus. Based on a gene disruption and cDNA microarray experiment, they proposed that DmsR itself is an oxygen sensor and directly activates transcription of the dmsEABCD genes under anaerobic conditions (21, 22).

Like H. marismortui, Haloferax volcanii is a facultative aerobic microorganism and can grow by denitrification. A DNA-binding protein, which is homologous with DmsR, is found to be present in the 5′ flank of the putative nitrate reductase gene in H. volcanii. The gene product, named NarO, is expected to be a cytoplasmic protein and involves a conserved cysteine-rich sequence that shows no notable similarity to known sequences having any assigned function in the N terminus.

Here, we investigated the function of NarO in the denitrifying growth of a ΔnarO mutant of H. volcanii. The ΔnarO mutant did not grow anaerobically in the presence of nitrate, while denitrifying growth was recovered by the expression of recombinant NarO. Site-specific mutagenesis of the recombinant NarO demonstrated the significance of the conserved cysteine residues in NarO. A promoter assay indicated that transcription of the nitrate reductase and nitrite reductase genes was activated when the archaeal cells were incubated anaerobically in the absence of nitrate, and the result is consistent with the observation that only anaerobic conditions are essential for inducing nitrate-reducing activity. Transcription of the denitrifying genes was inactivated in the ΔnarO mutant. A promoter assay also revealed that the narO gene was usually transcribed, regardless of whether it was cultivated under aerobic or anaerobic conditions. These results suggested that NarO is the transcription regulator possessing an oxygen-sensing function and that activated transcription of the denitrifying genes under anaerobic conditions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and growth conditions.

H. volcanii strain H26 was kindly supplied by T. Allers (Institute of Genetics, Nottingham University, United Kingdom) (23). The growth medium contained 5.0 g liter−1 Bacto yeast extract (Becton, Dickinson and Company, Sparks, MD), 2.0 g liter−1 tryptone (Oxoid Ltd., Basingstoke, Hampshire, United Kingdom), 2.0 g liter−1 KCl, 176.0 g liter−1 NaCl, 20.0 g liter−1 MgCl2·6H2O, and 0.1 g liter−1 CaCl2·2H2O and was adjusted to pH 7.4 before autoclaving. Solutions of chelated iron (100 mg liter−1 FeSO4·7H2O and 100 mg liter−1 EDTA) and trace elements (100 mg liter−1 Na2MoO4·2H2O, 200 mg liter−1 MnCl2·6H2O, 2 mg liter−1 CoCl2·6H2O, 100 mg liter−1 ZnSO4·7H2O, and 100 mg liter−1 CuSO4·5H2O), which were also prepared and autoclaved separately, were mixed with the medium at a volume of 1/1,000 each. The resulting Hv medium was used for cultivation of the strain. Aerobic cultivation was performed in the Hv medium at 37°C in the dark with shaking (120 rpm) for aeration. Cultivation of the strain under anaerobic conditions was carried out by using the medium supplemented with 50 mM KNO3 as a terminal electron acceptor of denitrification. The cultivation vessel, which was 150 ml in volume and contained 40 ml of medium, was sealed with butyl rubber; the gas phase in the vessel was then exchanged by gentle bubbling with O2-N2 (0.2:99.8 [vol/vol]) mixed gas (Shizuoka Sanso Co., Shizuoka, Japan) for 5 min using a sterile needle. The cultivation vessels were shaken at 80 rpm at 37°C in the dark. The gas phase in the vessel was changed every 24 h. Growth was monitored by measuring the optical density at 600 nm (OD600) using a model MPS-2000 spectrophotometer (Shimadzu Co., Kyoto, Japan) equipped with a cell holder for analysis of the suspension.

Disruption of narO gene in H. volcanii.

Strain H26, an orotate phosphoribosyl transferase (PyrE2) mutant of the H. volcanii strain DS2 (wild type), was used to disrupt the narO gene by double integration (23), as outlined in Fig. S1A and B in the supplemental material. Standard protocols used for DNA handling in E. coli and H. volcanii were according to Sambrook and Russell (24) and Dyall-Smith (25), respectively. PCR amplification of a 670-bp DNA fragment upstream of narO (HVO_B0159) was carried out using KOD-plus DNA polymerase (Toyobo Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan) with a set of oligonucleotide primers, narOUf and narOUr, against the H. volcanii genome as a template. The DNA sequence of the PCR product was determined using a CEQ 8000 genetic analysis system (Beckman Coulter, Inc., Brea, CA). An 800-bp DNA fragment downstream of the narO gene was also amplified using the primers narODf and narODr. Both fragments, narOU and narOD, were cloned into a pTA131 plasmid (supplied by T. Allers) (23), which harbored a functional pyrE2 gene, generating pΔnarO. Demethylation of the pΔnarO plasmid was carried out using E. coli strain SCS110 (Δdam) for the efficient transformation of halophilic archaea (26). The sequences of oligonucleotide primers used for PCR amplification are shown in Table S1 in the supplemental material.

Transformation of the pΔnarO to H. volcanii H26 was carried out according to a previously described protocol (25). A transformant was streaked on Casamino Acids (Hv-Ca) agar plates that contained no uracil and incubated at 37°C for about 2 weeks (23). One of the integrants that appeared on the agar plate, which had gained uracil prototrophy by pyrE2 integration, was chosen. Next, the pop-in strain, designated NO01, was streaked again on Hv-Ca agar plates supplemented with 10 mg liter−1 uracil and 50 mg liter−1 5′-fluoroorotate (5′-FOA) and incubated at 37°C. The colonies appearing on the plate, which showed tolerance to 5′-FOA by their inability to convert this compound to the toxic analog 5-fluorouracil by a pyrE2 pop-out via homologous recombination, were confirmed by PCR amplification using the primers narOUf and narODr, as shown in Fig. S1C in the supplemental material. The narO deletion mutant derived from H. volcanii H26 thus obtained was designated NO02. The haloarchaeal strains prepared and used in this study are summarized in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Strains of H. volcanii used in this study

| Strain | Derivation (reference) | Genotypea |

|---|---|---|

| H26 | Allers et al. (23) | ΔpyrE2 |

| NO01 | H26/pΔnarO pop-in | ΔpyrE2 narO+::[ΔnarO pyrE2+] |

| NO02 | NO01 pop-out | ΔpyrE2 ΔnarO |

| NO03 | NO02, pMLH32EV transformed | ΔpyrE2 ΔnarO {nov} |

| NO04 | NO02, pkGnarO transformed | ΔpyrE2 ΔnarO {pkatG::narO::His6 tag + nov} |

| NO05 | NO02, pkGnarOC17S transformed | ΔpyrE2 ΔnarO {pkatG::narO(C17S)::His6 tag + nov} |

| NO06 | NO02, pkGnarOC81S transformed | ΔpyrE2 ΔnarO {pkatG::narO(C81S)::His6 tag + nov} |

| NO07 | NO02, pkGnarOC83S transformed | ΔpyrE2 ΔnarO {pkatG::narO(C83S)::His6 tag + nov} |

| NO08 | NO02, pkGnarOC91S transformed | ΔpyrE2 ΔnarO {pkatG::narO(C91S)::His6 tag + nov} |

| NO09 | NO02, pkGnarOC100S transformed | ΔpyrE2 ΔnarO {pkatG::narO(C100S)::His6 tag + nov} |

| NOP01 | H26, pnarObgaH transformed | ΔpyrE2 {pnarO::bgaH + nov} |

| NOP02 | NO02, pnarObgaH transformed | ΔpyrE2 ΔnarO {pnarO::bgaH + nov} |

| NAP01 | H26, pnarAbgaH transformed | ΔpyrE2{pnarA::bgaH + nov} |

| NAP02 | NO02, pnarAbgaH transformed | ΔpyrE2 ΔnarO {pnarA::bgaH + nov} |

| NKP01 | H26, pnirKbgaH transformed | ΔpyrE2{pnirK::bgaH + nov} |

| NKP02 | NO02, pnirKbgaH transformed | ΔpyrE2 ΔnarO {pnirK::bgaH + nov} |

| NKP03 | H26, pnirKG2CbgaH transformed | ΔpyrE2{pnirKG2C::bgaH + nov} pnirKG2C; second G in inverted repeat was replaced by C |

| NKP04 | H26, pnirKA3TbgaH transformed | ΔpyrE2{pnirKA3T::bgaH + nov} pnirKA3T; third A was replaced by T |

| NKP05 | H26, pnirKA4TbgaH transformed | ΔpyrE2{pnirKA4T::bgaH + nov} pnirKA4T; fourth A was replaced by T |

Plasmids integrated on the chromosome are indicated by brackets, and episomal plasmids are indicated by braces. nov, novobiocin resistance.

Expression of H. volcanii NarO.

An expression plasmid of H. volcanii NarO was constructed by utilizing an H. volcanii-E. coli shuttle vector and promoter sequence of the haloarchaeal constitutive gene encoding KatG catalase-peroxidase (27, 28). The pHKH6 plasmid harbors H. marismortui katG (rrnAC1171) and its promoter sequence (77 bp in length) and the 3′-flanking 114-bp DNA region, into which a (CAC)6 sequence as a His6 tag had been introduced into the 3′ end of katG (28). Using the pHKH6 plasmid as a template, inverse PCR was carried out with oligonucleotide primers HmKPr and HmKTf to remove the DNA region encoding the KatG protein from pHKH6. In addition, a 640-bp DNA fragment containing narO was amplified using the primers narOf and narOr. The amplified narO gene was inserted into the manipulated pHKH6 using a ligation kit (Ligation high version 2; Toyobo), generating pUCkGnarO. Finally, the pUCkGnarO insert was cut out using BamHI and XbaI and cloned into a pMLH32EV vector, generating pkGnarO as an expression plasmid for NarO. Here, pMLH32EV is a shuttle vector derived from pMLH32 (kindly supplied by D. M. Dyall-Smith) by EcoRV digestion and self-ligation to demolish the bgaH gene, which encoded haloarchaeal β-galactosidase from Haloferax lucentense (JCM 9276T) and was originally present in pMLH32 (27).

Point mutagenesis at five cysteine residues (Cys17, Cys81, Cys83, Cys91, and Cys100) in the recombinant NarO was carried out by technical application of PCR. Five sets of oligonucleotide primers, C17Sf and C17Sr, C81Sf and C81Sr, C83Sf and C83Sr, C91Sf and C91Sr, and C100Sf and C100Sr, in which the corresponding Cys codon (TGC or TGT) was replaced with a Ser codon (TCG), were amplified by using the pUCkGnarO plasmid separately as a template. After treatment with DpnI to decompose the template DNA, the linear PCR products were cyclized by homologous recombination between the 5′ and 3′ regions in E. coli JM109 cells. The inserts in the five plasmids were cut out and cloned into pMLH32EV, generating pkGnarOC17S, pkGnarOC81S, pkGnarOC83S, pkGnarOC91S, and pkGnarOC100S, respectively, as expression plasmids for the mutant NarO proteins.

The six constructs, pkGnarO, pkGnarOC17S, pkGnarOC81S, pkGnarOC83S, pkGnarOC91S, and pkGnarOC100S, were introduced into strain NO02. The transformants were selected by tolerance to 0.5 mg liter−1 novobiocin, a DNA gyrase inhibitor, on the Hv agar medium. The colonies appearing on the plate were obtained and designated NO04 (+pkGnarO), NO05 (+pkGnarOC17S), NO06 (+pkGnarOC81S), NO07 (+pkGnarOC83S), NO08 (+pkGnarOC91S), and NO09 (+pkGnarOC100S). A transformation of NO02 with pMLH32EV was also carried out and designated NO03.

Reporter plasmid for narO, narA, and nirK gene promoters.

The bgaH gene was used for construction of the reporter assay plasmid (27). The 2.11-kbp bgaH gene was amplified using a set of oligonucleotide primers, bgaHf and bgaHr. Genome DNA of H. lucentense was used for the template. The 270-bp DNA fragment, including the total region of the H. volcanii narO gene promoter, was also amplified using a set of oligonucleotide primers, pnarOf and pnarOr, against the H. volcanii genome DNA as the template. Both amplified fragments were cloned into the pMLH32EV vector, generating pnarObgaH as a reporter plasmid for measuring the transcription activity of the narO promoter. pnarObgaH was introduced into strains H26 and NO02, yielding NOP01 and NOP02, respectively.

To analyze the transcription activity of the promoter of the putative nitrate reductase gene, a reporter plasmid was prepared from the 5′-flanking region of the narA gene. The 270-bp DNA fragment, including the total region of the narA gene promoter, was amplified using the oligonucleotide primer set pnarAf and pnarAr. The reporter plasmid pnarAbgaH was constructed using a procedure similar to that for the preparation of pnarObgaH. The plasmid was introduced into strains H26 and NO02, yielding NAP01 and NAP02, respectively.

The 5′-flanking sequence with 249 nucleotides of the H. volcanii nitrite reductase NirK gene (HVO_2141), including the putative promoter, was amplified by PCR using primers pnirKf and pnirKr. The reporter plasmid pnirKbgaH was constructed by the same procedure. Strains H26 and NO02 were transformed by the plasmid, yielding NKP01 and NKP02, respectively.

Site-directed mutagenesis of the promoter sequence of the nirK gene was carried out, according to Kunkel's method (29), with a slight modification. pUCpnirK, which contains the putative promoter sequence of the nirK gene in the pUC119 vector, was transformed to E. coli strain CJ236 (dut1 ung1 thi-1 relA1/pCJ105 [F′ Cmr]). The transformant was infected by an M13KO7 helper phage and then incubated in the kanamycin-supplemented medium. Uracil-substituted single-stranded pUCpnirK was collected from the supernatant of the medium by polyethylene glycol precipitation. After annealing with a nirKPG2C primer, which was designed for a transversion mutation at the 2nd nucleotide (G to C) in the inverted repeat sequence in the nirK promoter, a complementary strand of the single-stranded pUCpnirK was synthesized by using T4 DNA polymerase (TaKaRa). The chimeric double-stranded DNA thus obtained was transformed to E. coli strain JM109. The plasmid was isolated from the transformant, and the intended substitution was confirmed by DNA sequencing. The mutant pUCpnirKG2C thus obtained was used for the preparation of plasmid pnirKG2CbgaH and transformant NKP03 (host strain, H. volcanii H26) for a reporter assay experiment. Transversion mutations at the 3rd (A to T) and 4th (A to T) nucleotides were also individually carried out by using nirKPA3T and nirKPA4T, respectively. Two mutant plasmids, pnirKA3TbgaH and pnirKA4TbgaH, and the corresponding transformants, NKP04 and NKP05, respectively, were also prepared and used for the experiment.

Assay of transcription activities of gene promoters.

BgaH activity was measured by using o-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (ONPG) as the substrate, according to a previous report (27). Precultured cells of strains NOP01, NOP02, NAP01, NAP02, NKP01, and NKP02 were prepared for inoculation by aerobic cultivation in the Hv medium supplemented with 0.5 mg liter−1 novobiocin. After inoculation of the precultured medium with a 10% volume of the cultivation medium, the strains were cultivated in low-oxygen-tension conditions described in “Strains and growth conditions” above, using the Hv medium supplemented with 0.5 mg liter−1 novobiocin with or without 50 mM KNO3. The medium (1 ml) was sampled every 24 h using a sterile needle. After the OD600 of the medium was measured, the medium was centrifuged at 22,000 × g for 5 min to separate the cell pellet and supernatant using a centrifugal separator model 3700 (Kubota Co., Tokyo, Japan). The cell pellet obtained was suspended in 800 μl of the assay solution containing 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.2), 2.5 M NaCl, 10 μM MnCl2, and 0.1% β-mercaptoethanol. The cells were solubilized by adding 100 μl of 2% Triton X-100 to the suspension and vortexing for 10 s. The solution was transferred to a cuvette with a 1-cm light path, and the BgaH reaction was started by adding 100 μl of an 8-mg/ml ONPG solution. Increasing absorbance at 405 nm of the solution was monitored using a spectrophotometer. BgaH activity (in Miller units) was calculated according to the formula (ΔA405/OD600/min) × 103.

Assay of nitrate- and nitrite-reducing activities.

H. volcanii strains H26 and NO02 were cultivated aerobically in the Hv medium. Anaerobic cultivation of the two strains was also carried out using Hv medium supplemented with 50 mM KNO3 or 77 mM DMSO. Anaerobic incubation of the strains was also performed in the medium without supplementation of any respiratory substrates. The harvested archaeal cells were sonicated by the VP-30S supersonic oscillator (Taitec Corp., Saitama, Japan). The suspension thus treated was centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 10 min, and the enzymatic activity of the cell extract supernatant was measured. The enzymatic activities of nitrate and nitrite reductions in the cell extract were measured according to the methods of Yoshimatsu et al. (30) and Ichiki et al. (11), respectively, with a slight modification. The protein concentration was measured by using a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL) using bovine serum albumin as the standard.

Nitrate reductase activity was detected on polyacrylamide gel, as follows: H. volcanii H26 and NO02 (ΔnarO) were cultivated in the Hv medium under aerobic, anaerobic, or denitrifying conditions. The cells were harvested from 6.0 ml of medium by centrifugation after 4 days of cultivation. Total proteins were extracted by treating the cell pellet with a minimum volume of 10 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.0) containing 1% (wt/vol) Triton X-100 (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), followed by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE), according to the method of Davis (31). After electrophoresis, the gel was enclosed in a sealed glass container filled with 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) containing 1.0 M NaCl and 0.2 mM methyl viologen (MV). Sodium dithionite solution (final concentration, 2.3 mM) was injected into the container to reduce MV, and then the gel was incubated for about 10 min until infiltration of enough of the reduced MV had turned the gel blue. The reaction was started by the injection of NaNO3 to a concentration of 10 mM. An image of the colorless spot appearing on the gel due to the oxidation of MV catalyzed by nitrate reductase was recorded by a scanning apparatus.

Other methods.

A primer extension experiment to determine the transcription start point of the nirK gene is described in the supplemental material. The immunological method for detection of the recombinant NarO is also explained in the supplemental material. A homology search was carried out using the BLAST site (http://blast.genome.jp/), and sequence alignment by the neighbor-joining method was performed using Clustal W (http://clustalw.genome.ad.jp/). All chemicals used in the experiments were of the highest grade commercially available.

RESULTS

Phenotype analysis and complementation of ΔnarO mutation.

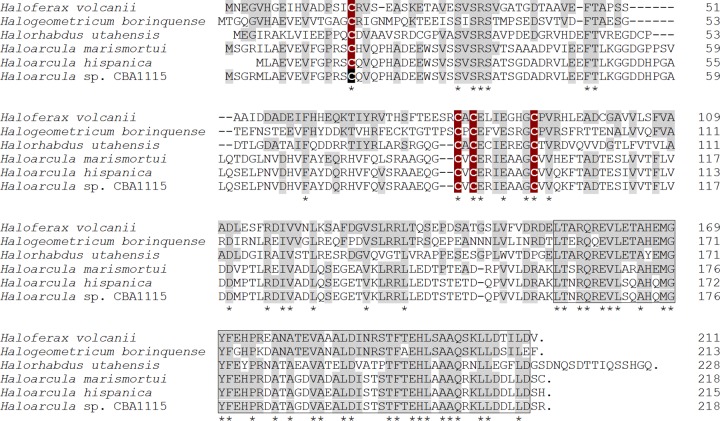

The putative nitrate reductase gene cluster, with a unique structure combining the respiratory quinol oxidase genes (narABC) and membrane-bound nitrate reductase genes (narGHDJ), is shown in Fig. 1. Homologous gene clusters have been identified in the genomes of nine haloarchaeal strains (H. volcanii, Haloferax mediterranei, H. marismortui, Haloarcula hispanica ATCC 33960 and N601, Haloarcula sp. strain CBA1115, Halorhabdus utahensis, Halogeometricum borinquense, Halomicrobium mukohataei, and Halorubrum lacusprofundi). NarO and its homologous proteins were identified in the 5′ flank of the nitrate reductase genes of six strains: H. volcanii, H. marismortui, two strains of H. hispanica, Haloarcula sp. CBA1115, H. utahensis, and H. borinquense. The alignment of the amino acid sequences of the seven NarO proteins is shown in Fig. 2. NarO proteins are expected to be soluble proteins, with molecular weights of about 22,000, and they lack a translocation signal sequence. The C-terminal amino acid sequence with 58 residues (174 to 201, using H. volcanii NarO numbering) showed significant similarity with the HTH-type DNA-binding motif of the Bat regulator that controls the oxygen- and light-dependent activation of the bop gene and its related genes in haloarchaea (17, 20). The four cysteines with the arrangement CXnCXCX7C (n ≈70), corresponding to Cys17, Cys81, Cys83, and Cys91 (H. volcanii NarO numbering), were conserved. The sequence of the N-terminal side of the NarO homologues showed no notable similarity to sequences with any assigned function involving that of bacterial FNR proteins, the most-investigated oxygen-sensing transcription regulator.

FIG 2.

Sequence alignment of NarO proteins. The deduced amino acid sequence of H. volcanii NarO (product of HVO_B0159) was aligned with that of orthologous proteins from H. borinquense (Hbor_34990, 49.8% identity to H. volcanii NarO), H. utahensis (Huta_0019, 40.4%), H. marismortui (rrnAC1193, 41.7%), H. hispanica (HAH_1793, 41.4%), and Haloarcula sp. CBA1115 (SG26_16865, 41.3%). The NarO sequences from the two strains of H. hispanica, ATCC 33960 (HAH_1793) and N601 (HISP_09150), are identical. The four conserved cysteines are indicated in white letters. The asterisks reveal the amino acid residues conserved among the seven NarO proteins. Residues identical to those of the H. volcanii NarO are emphasized by gray shading. The HTH-type DNA-binding domain is boxed. Residue numbers are shown on the right.

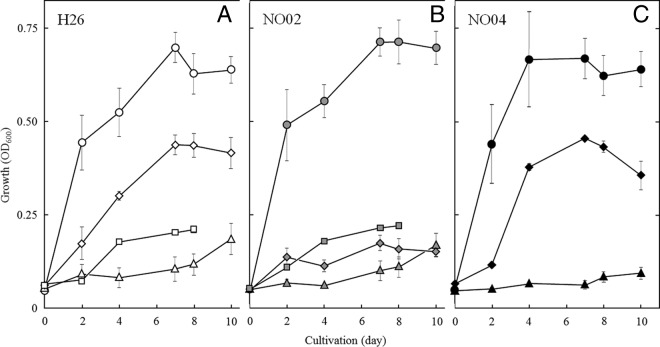

To elucidate the function of NarO, the narO gene was disrupted by a double integration method using uracil auxotrophic H. volcanii strain H26 (ΔpyrE2), as shown in Fig. S1 in the supplemental material. Under aerobic conditions, the narO mutant NO02 grew as well as the parental strain H26, as shown in Fig. 3A and B. When the strains of H. volcanii were incubated anaerobically in the absence of a respiratory substrate, a gradual increase in the OD600 of the medium was observed (Fig. 3, triangles). The observation suggests that the H. volcanii might be able to grow slowly by microaerobic respiration, as discussed below. Unlike the parental strain, NO02 grew poorly when cultivated anaerobically in the presence of nitrate (Fig. 3B). Notably, strain NO02 maintained the ability of DMSO respiration, indicating that NarO participates only in the regulation of denitrification in H. volcanii.

FIG 3.

Complementation of denitrifying growth of ΔnarO mutant by recombinant NarO. Strains H26 (A), NO02 (ΔnarO) (B), and NO04 (NO02/pkGnarO) (C) were cultivated as described in Materials and Methods. The increase in optical density of the medium was measured at 600 nm. The OD600 values of H26, NO02, and NO04, which grew aerobically without nitrate (circles), anaerobically without supplementation of any respiratory substrate (triangles), anaerobically with nitrate (diamonds), and anaerobically with DMSO (squares), are shown. The experiments were performed independently three times. The error bars represent the standard error (SE). When H26 and NO02 were cultivated by DMSO respiration, the SE values were very small; therefore, the error bars are masked by the square symbols.

Complementation of the growth capability by denitrification was examined by the expression of recombinant NarO in NO02. The expression plasmid pkGnarO was constructed from the shuttle vector pMLH32EV and the promoter of the katG gene. The recombinant NarO was engineered to contain a C-terminal His6 tag, with the aim of immunological detection and purification of the recombinant protein. The pMLH32EV vector was derived from pMLH32, which is a low-copy-number vector, whose copy number in the H. volcanii cell is about six (27). Cultivation experiments of strain NO04, the transformant of NO02 by pkGnarO, demonstrated that the anaerobic growth by denitrification was restored by expression of the recombinant NarO, as shown in Fig. 3C.

Functional analysis of conserved cysteines in NarO.

Point mutagenesis of the narO gene carried out on pkGnarO was performed to replace each of the four conserved cysteines of the recombinant NarO with serines. Plasmids for the expression of the mutant NarO proteins were inserted into NO02 to generate strains NO05, NO06, NO07, and NO08, which harbor the expression plasmids for the Cys17, Cys81, Cys83, and Cys91 mutant NarO proteins, respectively, and were examined in comparison to NO04. Mutation of the nonconserved cysteine (Cys100 in H. volcanii NarO) was also performed, generating strain NO09. As shown in Fig. 4, under aerobic conditions, the five strains with Cys→Ser narO mutations grew as well as strain NO04; however, when cultivated under denitrifying conditions, four of the five narO mutants, except for that with a mutation of the unconserved 5th Cys, were unable to grow. The results demonstrated that all four conserved cysteines are essential for the function of NarO to regulate denitrification.

FIG 4.

Functional analysis of conserved cysteines of NarO. Strains H26, NO02 (ΔnarO), NO03 (NO02/pMLH32EV), NO04 (NO02/pkGnarO), NO05 (Cys17 mutant NarO was expressed in NO02), NO06 (Cys81), NO07 (Cys83), NO08 (Cys91), and NO09 (Cys100) were cultivated under aerobic (white bars), anaerobic with nitrate (gray), and anaerobic without nitrate (black) conditions. The OD600 of each medium after 8 days of cultivation is indicated. The experiments were performed independently three times. The error bars represent the SE.

Transcription activities of narO gene promoter.

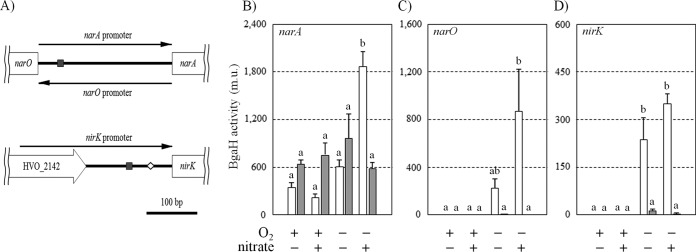

The narO gene is present in the 5′-flanking sequence of the narA gene in the reverse direction, and the narO and narA genes are separated by a 264-bp DNA sequence. The genetic function of the transcriptional regulation of both the narO gene and the putative nitrate reductase gene would involve the DNA region (Fig. 5A). Transcription activity was analyzed using the bgaH as the reporter gene and with the forward and reverse directions of the 264-bp DNA sequence as the narA and narO promoter, respectively.

FIG 5.

Transcription activities of the narO, narA, and nirK gene promoters were analyzed by a reporter assay using the bgaH gene encoding haloarchaeal β-galactosidase. (A) Schematic representation of the promoter regions used for reporter plasmid construction, where the conserved inverted repeat and putative haloarchaeal TATA box are shown by gray boxes and a diamond, respectively. (B) Transcription activities of the narO gene promoters were analyzed. Strains NOP01 (H26/pnarObgaH) and NOP02 (NO02/pnarObgaH) were cultivated under aerobic (O2, +; nitrate, − and +), anaerobic (O2, −; nitrate, −), or denitrifying (O2, +; nitrate, +) conditions for 4 days. The mean values of induced BgaH activities (in Miller units) for NOP01 and NOP02 are indicated by white and gray bars, respectively. The experiments were performed independently at least three times. The error bars represent the SE. Different letters denote significantly different means (P < 0.05, one-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni's test for multiple comparisons). Analysis of the transcription activity of the narA and nirK gene promoters was also carried out in the same manner. (C and D) The results obtained using strains NAP01 (H26/pnarAbgaH, white bars) and NAP02 (NO02/pnarAbgaH, gray bars) (C) and those obtained using strains NKP01 (H26/pnirKbgaH, white bars) and NKP02 (NO02/pnirKbgaH, gray bars) (D).

Strains NOP01 and NOP02 were derived from H26 and NO02, respectively, by transformation of the pnarObgaH plasmid. Both strains were cultivated under several conditions, and the induced BgaH activities were measured every 24 h. Figure 5B shows the BgaH activities at 72 h after starting cultivation; here, aerobic cells were in the late exponential phase, and denitrifying cells were in the mid-exponential phase. Very slow growth was observed in strains NOP01 and NOP02 under anaerobic incubation in the absence of nitrate. BgaH activities were observed in NOP02 under all cultivation conditions (637 to 963 Miller units [m.u.]), and no significant differences were detected among the activities, according to Bonferroni's multiple-comparison test. In contrast, enhancement of BgaH activity (1,863 ± 192 m.u. [mean ± standard error]), which was about three times the activity in the NOP02 cells, was observed in the denitrifying NOP01 cells. A similar result was obtained when using the microbial cells harvested at 48 h after starting cultivation (data not shown).

Transcription activities of narA gene promoter and expression of nitrate reductase.

Strains NAP01 and NAP02 were derived from H26 and NO02, respectively, by transformation of the pnarAbgaH plasmid for the narA promoter activity assay. The narA promoter was highly activated in the denitrifying NAP01 cells (868 ± 351 m.u.), as shown in Fig. 5C. Low BgaH activity (226 ± 46 m.u.) was observed in the starved NAP01 cells that had been incubated anaerobically in the absence of nitrate. No BgaH activity was detected in the aerobic cells of NAP01. The NAP02 cells showed very low BgaH activity (2.6 ± 2.0 m.u.) under denitrifying conditions.

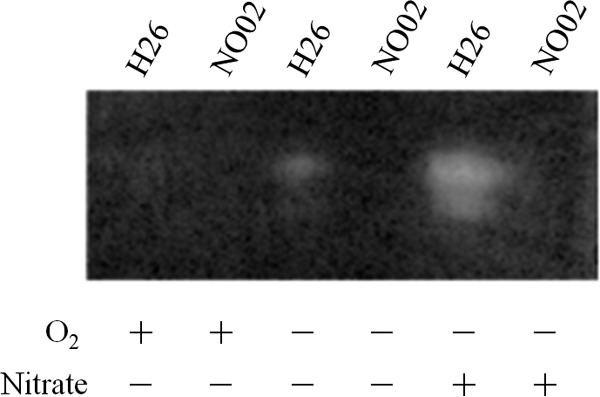

The expression of nitrate reductase under each cultivation condition was also examined. Nitrate-reducing activities induced in the H26 and NO02 cells, which were cultivated anaerobically in the presence or absence of nitrate for 72 h, were visualized on polyacrylamide gel by activity staining. Aerobic cells were also prepared and used as the experimental control. As shown in Fig. 6, a colorless spot that corresponded to the nitrate-dependent oxidation of reduced MV appeared on the gel where the total proteins solubilized from the denitrifying cells of H26 had been loaded. Relatively weak activity also appeared in the H26 cells cultivated anaerobically in the absence of nitrate. No enzymatic activity was detected in the aerobic cells of H26. Nitrate reductase was not induced in the NO02 cells even under denitrifying growth conditions. The conditional expression of nitrate reductase was consistent with the action of the narA promoter, as shown in Fig. 5C.

FIG 6.

Nitrate reductase activity. H26 and NO02 (ΔnarO) were cultivated under aerobic (O2, +; nitrate, −), anaerobic (O2, −; nitrate, −), or denitrifying (O2, −; nitrate, +) conditions. Total proteins were extracted from the cells by treating them with detergent, as described in Materials and Methods. After electrophoresis on polyacrylamide gel, the nitrate-reducing activity on the gel was visualized as a colorless spot that revealed the oxidation of reduced MV catalyzed by the induced nitrate reductase.

Transcription activities of nirK gene promoter.

The 169-bp-long DNA sequence that exists at the 5′-flanking region of the nirK gene (HVO_2141) should include elements to regulate transcription activity. The nucleotide sequence of 300 bp in length containing the whole region of the putative nirK promoter was used to construct the pnirKbgaH plasmid (Fig. 5A). The pnirKbgaH plasmid was transformed to strains H26 and NO02, and then the transformants NKP01 and NKP02, respectively, were prepared. As shown in Fig. 5D, BgaH activity was induced in the NKP01 strain when it was cultivated anaerobically. Like the narA promoter in the H26 cell, transcriptional activity of the nirK gene promoter appeared under anaerobic conditions whether the nitrate was supplemented or not, but a significant difference was found between the two activity levels: the activities of denitrifying cells and starved cells of NKP01 were estimated to be 350 ± 32 m.u. and 237 ± 69 m.u., respectively. Very low BgaH activity, at 3.3 ± 2.0 m.u., was detected in the denitrifying cells of NKP02, while no activity was observed in the aerobic cells. Similar to the conditional activation found in the narA gene promoter, these results provide persuasive evidence that the narO gene plays a critical role in the activation of the nirK promoter.

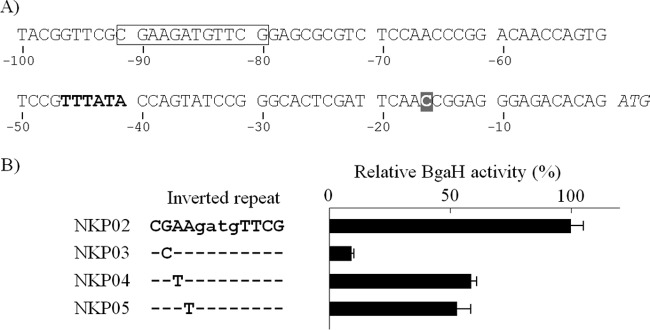

As indicated in Fig. S2 in the supplemental material, a primer extension experiment was performed to determine the transcription start point of the nirK gene in Haloferax denitrificans JCM 8864 (=ATCC 35960). H. denitrificans is phylogenetically close to H. volcanii, and the nucleotide sequence of its nirK promoter is very similar to that of H. volcanii (see Fig. S2A in the supplemental material). The result suggests that the transcription of the H. denitrificans nirK gene was initiated at a C residue located 15 bp upstream of the translation start ATG codon and 25 bp downstream of a putative TATA box (see Fig. S2B in the supplemental material). Due to the 92.7% identity of the nucleotide sequence, it is most likely that transcription of the H. volcanii nirK gene starts at the corresponding C residue located 14 bp upstream of the translation start codon and 25 bp downstream of the putative TATA box (Fig. 7A; see also Fig. S2 in the supplemental material).

FIG 7.

Mutation analysis of the inverted repeat of the nirK promoter region. (A) The DNA region located upstream of the nirK gene. An inverted repeat (CGAAX4TTCG) is boxed, and a putative haloarchaeal TATA box (consensus TTTWWW) is in bold type. The transcription start C residue, indicated by a shaded white letter, was inferred from primer extension analysis of the H. denitrificans nirK (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). The translation start codon of nirK is italicized. The DNA sequence is numbered relative to the translation start point. (B) Transcription activity was examined using a reporter plasmid in which the 2nd to 4th nucleotides of the inverted repeat were individually substituted. The experiments were performed independently three times. The error bars represent the SE. Cultivation of the four strains, NKP02, NKP03, NKP04, and NKP05, and measurement of the induced BgaH activities are described in Materials and Methods.

Nucleotide sequences of the 5′-flanking region of the denitrifying genes narA, nirK, norB, and nosZ of the haloarchaeal genome were aligned, as shown in Fig. S3 to S6 in the supplemental material, respectively. The inverted repeat sequence CGAAX4TTGC, which seems to be the recognition site of an HTH-type DNA-binding protein, was identified in a large part of the promoter of the denitrifying genes. As revealed in Fig. 7, a single mutation into the inverted repeat at the 2nd guanine caused a dramatic decrease in the transcriptional activity of the nirK promoter, and only 9% of the activity was detected. Substitutions of the 3rd and 4th adenines also decreased the transcription activity of the nirK promoter to about half, with 59% and 53% activity retained, respectively. These results demonstrated that the inverted repeat plays a significant role in the transcriptional regulation of the denitrifying genes.

DISCUSSION

Of the 31 species of haloarchaea for which total genomic information is presently available, six species include a putative nitrate reductase gene in combination with the gene encoding the regulatory protein NarO in the 5′-flanking region of the gene (Fig. 2). Interestingly, the regulatory gene encoding the protein that was homologous to NarO, named DmsR, is also present in the 5′-flanking region of the DMSO/TMAO reductase gene of 10 haloarchaeal strains (Halobacterium sp. NRC-1, Halobacterium salinarum R-1, H. volcanii, H. mediterranei, H. marismortui, two strains of H. hispanica, Haloarcula sp. CBA1115, Natronobacterium gregoryi, Natrinema sp. J7-2, and H. mukohataei) (Fig. 1). Although the unique cysteine-rich motif is conserved in DmsR, the internal sequence between the 1st and 2nd cysteines is about 20 residues shorter than that of NarO (21, 32). DmsR has been reported to have a significant role in the conditional expression of DMSO/TMAO reductase in Halobacterium sp. NRC-1 (21, 22) and in H. volcanii (32).

We performed gene disruption studies on H. volcanii NarO in combination with expression of a recombinant and a reporter assay experiment of denitrifying gene promoters. The narO deletion mutant of H. volcanii strain NO02 retained the ability to grow aerobically, with a growth rate similar to that of strain H26, whereas the mutant did not grow anaerobically by denitrification (Fig. 3). The result demonstrated the critical function of NarO in the induction of the denitrifying ability in H. volcanii. Anaerobic growth of H. volcanii with supplementation of DMSO instead of nitrate was not affected by disruption of the narO gene. In contrast, the dmsR deletion mutant of H. volcanii, which already had been prepared in our laboratory, lost the ability of anaerobic DMSO/TMAO respiration but did grow by denitrification, indicating that the functions of NarO and DmsR as the transcription regulator are not redundant (32).

In this study, anaerobic cultivation of H. volcanii was carried out under N2 gas containing 0.2% O2. The microaerobic condition is essential for the reproducibility of the anaerobic growth of H. volcanii, as reported previously (32). Although the reason for the instability of the growth under strict anaerobic conditions is not clear, one possibility is that the energy generation by microaerobic respiration is significant for H. volcanii for smooth adaptation to the anaerobic conditions and induction of the denitrifying enzymes. Very slow growth of strain H26 under anaerobic conditions without nitrate and strain NO02 (ΔnarO) under denitrifying conditions was observed, as shown in Fig. 3. The results might also correspond to a low energy yield by microaerobic respiration of H. volcanii.

As shown in Fig. 5, the transcription activity of the narO gene promoter was higher than that of the genes of the catabolic enzymes nitrate reductase and nitrite reductase, which are expressed in the microbial cells in large amounts (11, 30). However, until now, identification of the recombinant NarO expressed in the H. volcanii cells has not been followed by immunoblotting experiments using anti-His6 antibody. Purification of the recombinant NarO protein by Ni2+-affinity resin also failed. It is probable that the NarO molecule has a very short life span and is immediately decomposed by proteolysis in H. volcanii cells. Another explanation is also possible, e.g., the mRNA of the narO gene is very unstable, and therefore, the concentration of recombinant NarO molecules is lower than what can be detected immunologically.

As indicated in Fig. 5B, transcription of the narO gene was ordinarily activated at similar transcription levels whether cultivated under aerobic or anaerobic conditions, except for the remarkable increase in the activity observed in the denitrifying NOP01 cells. The results indicated that transcription of the narO gene is usually activated, regardless of the anaerobicity of the growing conditions, and it is enhanced by the NarO protein. In addition, the results shown in Fig. 5C and D demonstrate that NarO is critical for activation of the transcription of the denitrifying genes under anaerobic conditions. In bacteria, the transcription of denitrifying genes is controlled by dual regulatory systems, one being the oxygen/redox-sensing mechanism, and the other depending on nitrogen oxide species as the respiratory substrate (1, 33). The expression of denitrifying enzymes in bacteria, therefore, hardly occurs when they are cultivated anaerobically in the absence of nitrate (34, 35). The present result suggests that the H. volcanii denitrifying genes are mainly controlled by a NarO-dependent regulatory system that responds to anaerobic cultivation conditions. The results also revealed that NarO-dependent activation of transcription of the denitrifying genes was enhanced under the presence of nitrate, while the genetic mechanism is unknown so far.

The unique arrangement of the four conserved cysteines as CXnCXCX7C (n ≈70) is a structural characteristic of NarO and its homologous proteins (Fig. 2). Site-directed mutation experiments clearly demonstrated that all four cysteines in NarO were essential for the induction of denitrification, as shown in Fig. 4. In addition, transcription of the denitrifying genes required the narO gene and was activated under anaerobic conditions (Fig. 5C and D). The results are most explicable by the hypothesis that NarO participated in regulation of the oxygen and/or redox potential-dependent transcription of the denitrifying genes. The NarO homologs do not comprise a PAS domain, which is one of the oxygen/redox sensor motifs found in haloarchaeal Bat and other redox-dependent regulatory proteins (17, 20). One possible scenario is that, like the bacterial FNR, metal centers bound to the side chains of cysteines respond to oxygen molecules or low redox potential in the environment, causing the activation of NarO (15, 16). In this case, it should be noted that the arrangement of the four conserved cysteines in NarO shows no similarity to that of the iron-sulfur binding domain of the bacterial FNR. It is also plausible that the formation of a disulfide bridge between the consensus cysteines in the presence of oxygen or high redox potential inactivates NarO, as is likely for the E. coli OxyR, which controls the transcription of the genes encoding HPII catalase and other components for protection of the cell against oxidative stress (36). Another hypothesis is that a heme molecule is a functional center for oxygen sensing. Heme lyase, which takes part in the biosynthesis of c-type cytochrome, comprises the consensus Cys-Pro-Val sequence as a heme-binding motif (37). This Cys-Pro-Val sequence is highly conserved at the positions of two of four cysteines corresponding to Cys17 and Cys91 in H. volcanii NarO (Fig. 2).

An FNR-like regulator protein was not identified by searching the haloarchaeal genomic information, suggesting another regulatory mechanism for denitrification in haloarchaea. Interestingly, comparative searching of the putative DNA contact site in the haloarchaeal denitrification gene promoters demonstrated that an inverted repeat, CGAAX4TTGC, which was expected to interact with the HTH-type regulator in the dimeric state, was commonly present. The DNA sequence of the nirK promoter reveals a typical arrangement of the putative transcriptional elements in the haloarchaeal denitrifying gene promoter. As represented in Fig. 5A and 7A, and in Fig. S4 in the supplemental material, CGAAGATGTTCG is centered 39 bp upstream of the haloarchaeal TATA box (consensus TTTWWW, where W is A or T) in the H. volcanii nirK promoter (38). The transcription start point of the H. volcanii nirK gene was expected to be 25 bp downstream of the TATA box, based on the primer extinction analysis of the nirK gene of H. denitrificans, whose nirK promoter sequence was very similar (91% identical) to that of H. volcanii (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). A similar arrangement was also found in a large number of the promoters of the haloarchaeal denitrifying genes nirK, norB, and nosZ (see Fig. S4 to S6 in the supplemental material, respectively). Point mutagenesis at the 2nd nucleotide of the inverted repeat caused a drastic decrease (only 9.1% remaining) in the transcriptional activity of the nirK promoter (Fig. 7). Additionally, mutations at the 3rd and 4th nucleotides of the inverted repeat resulted in 41% and 47% decreases, respectively, in the nirK promoter activity. These results support our hypothesis that the genetic function of this inverted repeat sequence is the transcriptional regulation of denitrification in haloarchaea.

In contrast to the well-ordered structure of transcriptional elements in the nirK, norB, and nosZ gene promoters, the arrangements of the inverted repeat and putative TATA box were not comprehensive in the narA and narO promoters. The inverted repeat sequence was centered from 220 bp, 214 bp, and 191 bp upstream of the putative translation start position of the H. volcanii, H. mukohataei, and H. utahensis narA genes, respectively (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). A TATA box-like motif was not identified due to the A/T-rich nature of the putative promoter regions. The inverted repeat was 135 bp upstream from the translation start position of the narA genes of four Haloarcula species, but it was not found to be present in the narA promoter of H. mediterranei and H. lacusprofundi. Mutagenetic analysis of the reporter assay experiment and identification of the transcription starting point of the denitrifying genes are now under way.

Our present study suggests that NarO is a key regulator of denitrifying growth in H. volcanii. The cysteine-rich motif was critical for transcriptional regulation under anaerobic conditions. The inverted repeat CGAAX4TTCG was often present in the haloarchaeal denitrifying gene promoters and was shown to play a significant role in transcription regulation. The most important problem that remains unsolved is whether NarO binds directly with the inverted repeat and activates the transcription of denitrifying genes. In addition, the 46 proteins homologous to H. volcanii NarO were identified in 21 species of the 31 haloarchaea for which the total genome sequence is now available. However, except for the seven NarO proteins and 11 DmsR proteins, the regulatory targets of the remaining 29 homologs have remained uncertain. Further investigations, especially purification of the recombinant NarO protein, identification of the NarO binding site on the genomic DNA, and assignment of the functions of the NarO homologs, are required for total understanding of the regulation of haloarchaeal anaerobic metabolisms.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by research grants from the Noda Institute for Scientific Research, the Japan Space Forum (Exploratory Research for Space Utilization), and the True Nano Research Program of Shizuoka University to T.F.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JB.00833-15.

REFERENCES

- 1.Zumft WG. 1997. Cell biology and molecular basis of denitrification. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 61:533–616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bonete MJ, Martínez-Espinosa RM, Pire C, Zafrilla B, Richardson DJ. 2008. Nitrogen metabolism in haloarchaea. Saline Systems 4:9. doi: 10.1186/1746-1448-4-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cabello P, Roldan MD, Moreno-Vivián C. 2004. Nitrate reduction and the nitrogen cycle in archaea. Microbiology 150:3527–3546. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27303-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Philippot L. 2002. Denitrifying genes in bacterial and archaeal genomes. Biochim Biophys Acta 1577:355–376. doi: 10.1016/S0167-4781(02)00420-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martínez-Espinosa RM, Richardson DJ, Butt JN, Bonete MJ. 2006. Respiratory nitrate and nitrite pathway in the denitrifier haloarchaeon Haloferax mediterranei. Biochem Soc Trans 34:115–117. doi: 10.1042/BST0340115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martinez-Espinosa RM, Dridge EJ, Bonete MJ, Butt JN, Butler CS, Sargent F, Richardson DJ. 2007. Look on the positive side! The orientation, identification and bioenergetics of ‘archaeal’ membrane-bound nitrate reductases. FEMS Microbiol Lett 276:129–139. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2007.00887.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yoshimatsu K, Iwasaki T, Fujiwara T. 2002. Sequence and electron paramagnetic resonance analyses of nitrate reductase NarGH from a denitrifying halophilic euryarchaeote Haloarcula marismortui. FEBS Lett 516:145–150. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(02)02524-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yoshimatsu K, Araya O, Fujiwara T. 2007. Haloarcula marismortui cytochrome b-561 is encoded by the narC gene in the dissimilatory nitrate reductase operon. Extremophiles 11:41–47. doi: 10.1007/s00792-006-0016-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lledó B, Martínez-Espinosa RM, Marhuenda-Egea FC, Bonete MJ. 2004. Respiratory nitrate reductase from haloarchaeon Haloferax mediterranei: biochemical and genetic analysis. Biochim Biophys Acta 1674:50–59. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2004.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yoshimatsu K, Fujiwara T. 2010. Nitrogen cycle in the extremely halophilic environment: biochemistry of haloarchaeal denitrification. Seikagaku 81:1087–1093. (In Japanese.) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ichiki H, Tanaka Y, Mochizuki K, Yoshimatsu K, Sakurai T, Fujiwara T. 2001. Purification, characterization, and genetic analysis of Cu-containing dissimilatory nitrite reductase from a denitrifying halophilic archaeon, Haloarcula marismortui. J Bacteriol 183:4149–4156. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.14.4149-4156.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baliga NS, Bonneau R, Facciotti MT, Pan M, Glusman G, Deutsch EW, Shannon P, Chiu Y, Weng RS, Gan RR, Hung P, Date SV, Marcotte E, Hood L, Ng WV. 2004. Genome sequence of Haloarcula marismortui: a halophilic archaeon from the Dead Sea. Genome Res 14:2221–2234. doi: 10.1101/gr.2700304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stewart V. 1993. Nitrate regulation of anaerobic respiratory gene expression in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol 9:425–434. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01704.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Constantinidou C, Hobman JL, Griffiths L, Patel MD, Penn CW, Cole JA, Overton TW. 2006. A reassessment of the FNR regulon and transcriptomic analysis of the effects of nitrate, nitrite, NarXL, and NarQP as Escherichia coli K-12 adapts from aerobic to anaerobic growth. J Biol Chem 281:4802–4815. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512312200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kiley PJ, Beinert H. 1998. Oxygen sensing by the global regulator, FNR: the role of the iron-sulfur cluster. FEMS Microbiol Rev 22:341–352. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.1998.tb00375.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dibden DP, Green J. 2005. In vivo cycling of the Escherichia coli transcription factor FNR between active and inactive states. Microbiol 151:4063–4070. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.28253-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gong W, Hao B, Mansy SS, Gonzalez G, Gilles-Gonzalez MA, Chan MK. 1998. Structure of a biological oxygen sensor: a new mechanism for heme-driven signal transduction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95:15177–15182. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mesa S, Bedmar EJ, Chanfon A, Hennecke H, Fischer HM. 2003. Bradyrhizobium japonicum NnrR, a denitrification regulator, expands the FixLJ-FixK2 regulatory cascade. J Bacteriol 185:3978–3982. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.13.3978-3982.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gropp F, Betlach MC. 1994. The bat gene of Halobacterium halobium encodes a trans-acting oxygen inducibility factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 91:5475–5479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baliga NS, Kennedy SP, Ng WV, Hood L, DasSarma S. 2001. Genomic and genetic dissection of an archaeal regulon. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98:2521–2525. doi: 10.1073/pnas.051632498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Müller JA, DasSarma S. 2005. Genomic analysis of anaerobic respiration in the archaeon Halobacterium sp. strain NRC-1: dimethyl sulfoxide and trimethylamine N-oxide as terminal electron acceptors. J Bacteriol 187:1659–1667. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.5.1659-1667.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.DasSarma P, Zamora RC, Müller JA, DasSarma S. 2012. Genome-wide responses of the model archaeon Halobacterium sp. strain NRC-1 to oxygen limitation. J Bacteriol 194:5530–5537. doi: 10.1128/JB.01153-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Allers T, Ngo HP, Mevarech M, Lloyd RG. 2004. Development of additional selectable markers for the halophilic archaeon Haloferax volcanii based on the leuB and trpA genes. Appl Environ Microbiol 70:943–953. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.2.943-953.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sambrook J, Russell DW. 2001. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 3nd ed Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dyall-Smith DM. 2009. The halohandbook: protocols for haloarchaeal genetics. Version 7.1. http://www.haloarchaea.com/resources/halohandbook/Halohandbook_2009_v7.1.pdf.

- 26.Holmes ML, Nuttall SD, Dyall-Smith ML. 1991. Construction and use of halobacterial shuttle vectors and further studies on Haloferax DNA gyrase. J Bacteriol 173:3807–3813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Holmes M, Pfeifer F, Dyall-Smith M. 1994. Improved shuttle vectors for Haloferax volcanii including a dual-resistance plasmid. Gene 146:117–121. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90844-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ten-i T, Kumasaka T, Higuchi W, Tanaka S, Yoshimatsu K, Fujiwara T, Sato T. 2007. Expression, purification, crystallization and preliminary X-ray analysis of the Met244Ala variant of catalase-peroxidase (KatG) from the haloarchaeon Haloarcula marismortui. Acta Crystallogr Sect F Struct Biol Cryst Commun 63:940–943. doi: 10.1107/S1744309107046489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kunkel TA. 1985. Rapid and efficient site-specific mutagenesis without phenotypic selection. Proc Nat Acad Sci U S A 82:488–492. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.2.488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yoshimatsu K, Sakurai T, Fujiwara T. 2000. Purification and characterization of dissimilatory nitrate reductase from a denitrifying halophilic archaeon, Haloarcula marismortui. FEBS Lett 470:216–220. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(00)01321-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Davis BJ. 1964. Disc electrophoresis. II. Method and application to human serum proteins. Ann N Y Acad Sci 121:404–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Qi QZ, Ito Y, Yoshimatsu K, Fujiwara T. 2015. Transcriptional regulation of dimethyl sulfoxide respiration in a haloarchaeon, Haloferax volcanii. Extremophiles 20:27–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Walker MS, DeMoss JA. 1992. Role of alternative promoter elements in transcription from the nar promoter of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 174:1119–1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stewart V, Parales J Jr. 1988. Identification and expression of genes narL and narX of the nar (nitrate reductase) locus in Escherichia coli K-12. J Bacteriol 170:1589–1597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kalman LV, Gunsalus RP. 1990. Nitrate- and molybdenum-independent signal transduction mutations in narX that alter regulation of anaerobic respiratory genes in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 172:7049–7056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zheng M, Aslund F, Storz G. 1998. Activation of the OxyR transcription factor by reversible disulfide bond formation. Science 279:1718–1721. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5357.1718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Steiner H, Kispal G, Zollner A, Haid A, Neupert W, Lill R. 1996. Heme binding to a conserved Cys-Pro-Val motif is crucial for the catalytic function of mitochondrial heme lyases. J Biol Chem 271:32605–32611. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.51.32605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Soppa J. 1999. Normalized nucleotide frequencies allow the definition of archaeal promoter elements for different archaeal groups and reveal base-specific TFB contacts upstream of the TATA box. Mol Microbiol 31:1589–1601. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01274.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.