ABSTRACT

The gene transfer agent of Rhodobacter capsulatus (RcGTA) is a genetic exchange element that combines central aspects of bacteriophage-mediated transduction and natural transformation. RcGTA particles resemble a small double-stranded DNA bacteriophage, package random ∼4-kb fragments of the producing cell genome, and are released from a subpopulation (<1%) of cells in a stationary-phase culture. RcGTA particles deliver this DNA to surrounding R. capsulatus cells, and the DNA is integrated into the recipient genome though a process that requires homologs of natural transformation genes and RecA-mediated homologous recombination. Here, we report the identification of the LexA repressor, the master regulator of the SOS response in many bacteria, as a regulator of RcGTA activity. Deletion of the lexA gene resulted in the abolition of detectable RcGTA production and an ∼10-fold reduction in recipient capability. A search for SOS box sequences in the R. capsulatus genome sequence identified a number of putative binding sites located 5′ of typical SOS response coding sequences and also 5′ of the RcGTA regulatory gene cckA, which encodes a hybrid histidine kinase homolog. Expression of cckA was increased >5-fold in the lexA mutant, and a lexA cckA double mutant was found to have the same phenotype as a ΔcckA single mutant in terms of RcGTA production. The data indicate that LexA is required for RcGTA production and maximal recipient capability and that the RcGTA-deficient phenotype of the lexA mutant is largely due to the overexpression of cckA.

IMPORTANCE This work describes an unusual phenotype of a lexA mutant of the alphaproteobacterium Rhodobacter capsulatus in respect to the phage transduction-like genetic exchange carried out by the R. capsulatus gene transfer agent (RcGTA). Instead of the expected SOS response characteristic of prophage induction, this lexA mutation not only abolishes the production of RcGTA particles but also impairs the ability of cells to receive RcGTA-borne genes. The data show that, despite an apparent evolutionary relationship to lambdoid phages, the regulation of RcGTA gene expression differs radically.

INTRODUCTION

The gene transfer agent of Rhodobacter capsulatus (RcGTA) combines features of bacteriophage-mediated transduction with natural transformation. The genes that encode the structural proteins of RcGTA particles are endogenous to the R. capsulatus chromosome and are located in at least two loci (1). In the stationary phase of R. capsulatus cultures, a subset (<1%) of the cell population produces RcGTA particles that resemble a tailed bacteriophage. Essentially random ∼4-kb fragments of genomic DNA are packaged into the RcGTA particles, and particles are released by cell lysis mediated by a canonical endolysin/holin system, as for bacteriophage release (2–4). RcGTA particles recognize a capsular polysaccharide receptor on R. capsulatus cells using spikes located on the RcGTA capsid (5). The current understanding is that RcGTA appears to inject DNA into the periplasmic space, and homologs of the natural-transformation genes comEC and comF are required for the transfer of the DNA fragment into the cytoplasm (6). Integration of the DNA into the recipient's chromosome requires comM, recA, and dprA and may result in allele exchange, again as in natural transformation (7).

The regulation of RcGTA production is complex and involves several bacterial regulatory factors. RcGTA production is stimulated in laboratory cultures of R. capsulatus upon entry into stationary phase, in part because of quorum sensing (8, 9). Transduction requires homologs of the phosphorelay proteins CckA-ChpT-CtrA, originally discovered in Caulobacter crescentus and widespread in the alphaproteobacteria (10). R. capsulatus strains lacking the unlinked cckA, chpT, or ctrA genes are unable to act as transduction donors either because RcGTA structural gene transcripts are not induced (ctrA mutants) or because maturation and release of RcGTA are impaired (cckA and chpT mutants). It appears that nonphosphorylated CtrA is needed for expression of RcGTA structural genes early in the induction process and that phosphorylated CtrA (CtrA∼P) is needed late in the induction process for cell lysis and release of RcGTA particles (4, 11, 12). Furthermore, cells lacking the ctrA gene are unable to act as recipients in RcGTA-mediated gene transfer, because the CtrA protein is also required to induce the expression of comEC, comF, comM, and dprA (6, 7).

In this study, we extend the understanding of RcGTA regulation to include the LexA protein. The LexA protein is the master regulator in many species of a DNA repair pathway termed the SOS response that is induced by damaged DNA (13). Like RcGTA, the SOS response is stimulated during stationary phase but in response to oxidative stress that results in DNA damage, whereas DNA damage has not been shown to induce the production of RcGTA (14, 15).

In many species, LexA directly represses a suite of genes by binding through an N-terminal region to sequences called SOS boxes located in operator regions (14, 16). When DNA is damaged, single-stranded regions become coated with RecA, the same protein that mediates homologous recombination in RcGTA-mediated gene transduction (7, 13, 14). The single-stranded DNA-RecA complex activates a C-terminal autoproteolytic domain within LexA, causing LexA to cleave itself at a largely conserved residue and dissociate from the SOS box, thereby allowing transcription of SOS response genes. Rarely, LexA can act as an activator of transcription (13, 17).

LexA has also been implicated in the induction of Siphoviridae prophages, with which RcGTA has an ancestor of some structural genes in common (1, 18). In the classical Escherichia coli lambda model, the prophage state is maintained by the phage-encoded repressor cI, which binds 5′ of lytic cycle genes. cI contains an autoproteolytic domain similar to that of LexA and thus is cleaved upon induction of the SOS response by DNA damage, resulting in prophage induction (18). There are also examples of prophage induction mediated directly by LexA, as seen in the lambdoid phages Gifsy-1 and Gifsy-3 of Salmonella enterica, where LexA represses the transcription of a phage-encoded antirepressor (18, 19).

Here, we report a connection between the sensor kinase CckA and the SOS response in the regulation of RcGTA. We show that R. capsulatus rcc02361 (here lexA) encodes a protein functionally homologous to the well-studied E. coli LexA repressor. Furthermore, we report that lexA is required for both RcGTA production and maximal recipient capability. We demonstrate binding of His-tagged LexA specifically to cckA and other SOS box-containing DNA fragments in vitro and that the absence of LexA increases the transcription of cckA in vivo. We suggest that the increased expression of cckA because of the absence of LexA repression is at least partially responsible for the RcGTA-deficient phenotype of the lexA mutant.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

The strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1 and described here in more detail. E. coli strains DH5α λpir, S17-1 λpir (20), and BL21(DE3) (Invitrogen) were used for cloning, conjugation of plasmids into R. capsulatus, and protein overexpression, respectively. E. coli strains were grown at 37°C, or at 30°C for protein expression, in LB medium (21) supplemented with the appropriate antibiotics at the following concentrations: ampicillin, 100 μg ml−1; gentamicin sulfate, 10 μg ml−1; kanamycin sulfate, 50 μg ml−1; tetracycline hydrochloride, 10 μg ml−1; chloramphenicol, 35 μg ml−1. E. coli culture turbidity was measured at 600 nm (optical density at 600 nm [OD600] of 1 = ∼109 CFU ml−1).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Description | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| B10 | R. capsulatus WT, Rifs | 15 |

| SB1003 | R. capsulatus WT, Rifr | 52 |

| DE442 | RcGTA overproducer, derived from SB1003 by chemical mutagenesis | 23 |

| SBpG | SB1003 derived, RcGTA promoter-mCherry reporter fusion | This study |

| SBpGΔlexA | SBpG derived, deletion of rcc02361 reading frame (lexA) | This study |

| SBpGΔcckA | SBpG derived, disruption of cckA reading frame with kanamycin resistance cassette | This study, as described in reference 4 |

| SBpGΔlexA ΔcckA | SBpG derived, deletion of rcc02361 reading frame (lexA), disruption of cckA reading frame with kanamycin resistance cassette | This study, as described in reference 4 |

| ΔgtaI | Capsule-deficient mutant | 27 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pCM62 | Broad-host-range vector, Tetr | 30 |

| pLexA | pCM62-derived lexA complementation plasmid, Tetr | This study |

| pRK415 | Broad-host-range vector, Tetr | 53 |

| pCckA | pRK415-derived cckA complementation plasmid, Tetr | 4 |

| pZDJ | Suicide vector, sacB Gmr | 27 |

| pZDJΔlexA | Suicide plasmid for lexA deletion | This study |

| pZDJΔ1081 | pZDJ-derived suicide plasmid, Gmr, used to test capacity for homologous recombination | 27 |

| pET28a(+) | Expression vector | Novagen |

| pETLexA | pET28a(+) derived, for expression of R. capsulatus LexA protein in E. coli BL21(DE3) | This study |

| pXCA601 | lacZ promoter-probe vector, Tetr | 33 |

| pXCA-ghsA | pXCA601-derived RcGTA head spike promoter-lacZ fusion reporter | 5 |

| p601-g65 | pXCA601-derived RcGTA orfg1 promoter-lacZ fusion reporter | 32 |

| pDprALacZ | pXCA601-derived dprA promoter-lacZ fusion reporter | 7 |

| pRhokHi-6 | R. capsulatus expression vector | 39 |

| pRhoCckA | pRhokHi-6 derived, used to express cckA constitutively from aphII promoter | This study |

The R. capsulatus strains used in this study were all derivatives of strain SB1003, whose genome has been sequenced (22) and which is a rifampin-resistant derivative of wild-type (WT) strain B10 (15). The RcGTA overproducer mutant DE442 used in this study as a source of RcGTA for recipient capability assays was derived from SB1003 by chemical mutagenesis (23, 24).

R. capsulatus cultures were grown at 30°C in either YPS complex medium (25) or defined RCV medium (26). For RcGTA transduction assays (measuring RcGTA production), donor strains were grown phototrophically in YPS medium and harvested in the early stationary phase, whereas recipient strain B10 was grown phototrophically in RCV medium and harvested in the stationary phase. When appropriate, media were supplemented with gentamicin sulfate at 3 μg ml−1, kanamycin sulfate at 10 μg ml−1, rifampin at 80 μg ml−1, or tetracycline hydrochloride at 1 μg ml−1. In all assays except for RcGTA production, the OD650 was used as a measure of the number of R. capsulatus cells per milliliter (OD650 of 1 = ∼4.5 × 108 CFU ml−1); alternatively, cell concentration was monitored in a Klett-Summerson photometer (red filter no. 66; 100 Klett units = ∼4 × 108 CFU ml−1).

Construction of WT SB1003-derived strain SBpG.

The ΔlexA and ΔlexA ΔcckA mutants were constructed in a WT SB1003-derived strain called SBpG that has an mCherry reporter gene fused to the promoter for the main RcGTA structural gene cluster (pGTA) on the chromosome. The integration of the fusion sequence was performed by introducing it into R. capsulatus for allelic exchange on suicide plasmid pZDJ (27).

The pGTA-mCherry fusion sequence was constructed essentially as described previously (3), except that the pGTA fragment (625 bp) was PCR amplified with primers pGTA5SacI (pGTA5 with a SacI restriction site replacing the PstI site) and pGTA2.6 (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). The mCherry gene was excised from plasmid pmCherry (Clontech) by digestion with BamHI and EcoRI. These two fragments were sequentially subcloned into pBlueScriptSK, yielding a plasmid called pBSpGmC. The RcGTA 3′ fragment was generated by PCR with primers pGTARarmF and pGTARarmR (see Table S1 in the supplemental material), followed by sequential subcloning of the EcoRI- and SalI-digested fragments (an EcoRI-SalI fragment and then an EcoRI-EcoRI fragment) into pBSpGmC, giving plasmid pBSpGmCGTA. The DNA sequence was confirmed, the plasmid was digested with SacI and BamHI, and the pGmCGTA segment was subcloned into suicide vector pZDJ, yielding plasmid pZDJ::pGmCGTA, which was conjugated into SB1003, and allele exchange was selected by resistance to sucrose and screening for sensitivity to gentamicin. Candidate clones were confirmed by PCR.

Construction of the ΔlexA mutant.

The ΔlexA mutant created for this study is a markerless deletion of the entire rcc02361 coding sequence except the first three and last three codons. The rcc02361 coding region and ∼1-kb 5′ and 3′ sequences were amplified by PCR from SB1003 genomic DNA with primers lexA_XbaI_F and lexA_XbaI_R (see Fig. S3 and Table S1 in the supplemental material). This PCR product was digested with SphI and cloned into suicide plasmid pZDJ (27). The resultant plasmid was used as the template for a PCR with primers del_lexA_F and del_lexA_R (see Fig. S3 and Table S1 in the supplemental material). By the FastCloning method (28), this linear product was circularized upon transformation into E. coli DH5α λpir, yielding plasmid pZDJΔlexA. The sequences of the flanking regions and deleted coding region were verified by DNA sequencing.

The pZDJΔlexA construct was conjugated into R. capsulatus strain SBpG containing a transposon-disrupted rcc02361 allele. First crossovers of pZDJΔlexA into the chromosome were selected by using the gentamicin marker on the pZDJ vector. Second crossovers where the transposon-disrupted rcc02361 allele had been lost, leaving behind the markerless ΔlexA allele, were identified by screening for kanamycin-sensitive colonies. The loss of the transposon-disrupted rcc02361 allele and the retention of the ΔlexA allele were confirmed by PCR.

Construction of the ΔlexA ΔcckA double mutant.

A kanamycin resistance cassette-disrupted cckA allele cloned into vector pUC19 (4) was introduced into the SBpG ΔlexA background by RcGTA-mediated transduction and kanamycin resistance selection, essentially as described previously (29).

Construction of complementing plasmid pLexA.

The rcc02361 coding region and flanking sequences were amplified from SB1003 genomic DNA with primers lexA_HindIII_F and lexA_HindIII_R (see Fig. S3 and Table S1 in the supplemental material). This PCR product was digested with HindIII and cloned into plasmid pCM62 (30). The DNA sequences of the flanking regions and coding region were verified.

Construction of plasmid pRhoCckA.

The cckA open reading frame (ORF) was amplified with primers CckARho-F and CckARho-R (see Table S1 in the supplemental material), and the amplicon was cloned into pRhokHi-6 at introduced NdeI and SacI sites to produce plasmid pRhoCckA, which expresses cckA constitutively from the aphII gene promoter.

RcGTA transduction assay.

Gene transfer from a donor to a recipient strain was quantified with a gene transfer assay by a method similar to that previously described (9). In this study, rifampin resistance was transduced into the rifampin/gentamicin-sensitive WT strain B10 recipient.

Donor cultures were grown phototrophically for 48 h in YPS broth. No antibiotics were added to the donor culture carrying trans complementation plasmids, as it was observed that the plasmids are maintained without selection and preliminary results showed that antibiotics in the donor supernatant interfered with the recipient culture upon coincubation. Recipient cultures were grown anaerobically for 72 h in RCV broth. Culture turbidities were monitored to ensure that a turbidity exceeding 400 Klett units had been reached before harvesting.

Harvested donor cultures were pelleted by centrifugation, and the RcGTA-containing supernatant was passed through a 0.2-μm-pore-size filter. A suspension of recipient cells was prepared by centrifuging 3 ml of recipient culture, discarding the supernatant, and suspending the pellet in 10 ml of G buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.8], 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM CaCl2, 1 mM NaCl, 500 μg/ml bovine serum albumin [BSA]). Five hundred microliters of recipient cell suspension was incubated with 100 μl of filtered donor supernatant for 90 min on a shaking platform at 30°C, 900 μl of RCV was added, and then the cells were allowed to acquire and express genes for 4 h under the same conditions. Cells were plated on YPS agar containing rifampin and incubated at 30°C for 48 h before inspection for colony formation.

Transposon mutagenesis.

The Δ280pG::lacZ mutant strain used for transposon Tn5 mutagenesis (31) was created by PCR amplifying the RcGTA promoter region as described previously (32) and subcloning it into SacI/BamHI double-digested suicide plasmid pZDJ (27), resulting in pZDJ::pGTA. The lacZ gene was PCR amplified from plasmid pXCA601 (33) with primers lacZ_F_BamHI and lacZ_R_HindIII (see Table S1 in the supplemental material), and the resulting fragment was digested with BamHI and HindIII and subcloned into BamHI/HindIII double-digested plasmid pBluescript, resulting in pBS-lacZ. The RcGTA right arm fragment was PCR amplified from WT strain SB1003 genomic DNA with primers GTARarmF_HindIII and GTARramR. The resulting fragment was double digested with HindIII and SalI and ligated to HindIII/SalI double-digested pBS-lacZ, resulting in pBS-lacZ-GTA. The lacZ-GTA fragment was then excised with BamHI/SalI and subcloned into BamHI/SalI-digested pZDJ::pGTA, resulting in pZDJ:pGTA-lacZ-GTA, which was then conjugated into R. capsulatus overproducer strain Δ280 as described previously (27), with allele exchange selection by resistance to sucrose and screening for sensitivity to gentamicin and blue color on media containing 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (X-Gal). Candidate clones were confirmed by PCR.

Transposon mutagenesis was carried out by conjugation of a Tn5 hyperproducer suicide plasmid (31) into the Δ280pG::lacZ mutant strain, followed by selection for kanamycin resistance on RCV medium. Kanamycin-resistant clones were screened for a decrease in RcGTA promoter activity (indicated by a decrease in β-galactosidase activity) on the basis of a decrease in the blue color of colonies arising on agar medium containing X-Gal.

RcGTA recipient capability assays.

An RcGTA stock was prepared from a DE442 overproducer mutant harboring a plasmid containing the rcc01080 gene (pd1080Gm) interrupted by a gentamicin resistance (Gmr) cassette (6). This RcGTA stock was used because the Gmr gene is not present in the WT and mutant R. capsulatus strains studied in our work. A transduction assay was performed as described previously (6); cells were spread on plates of RCV medium containing gentamicin, and the gentamicin-resistant colonies were counted after 3 days of growth. Because of variability in the total numbers of transductants between individual experiments and because the ΔlexA mutant strain yielded ∼10% of the number of CFU/OD unit of the WT strain (attributed to filamentation; see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material), RcGTA recipient capability efficiencies are expressed as a percentage of the total number of calculated CFU, with each experimental strain being compared to the WT control within the same experiment.

Western blotting.

R. capsulatus cultures were grown under phototrophic conditions in YPS medium, and cells were harvested by centrifugation at stationary phase and lysed by the addition of SDS to 2% and boiling for 10 min. Aliquots of lysate or culture supernatant from equivalent numbers of cells, according to the OD660, were separated by 12% SDS-PAGE and blotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane (PerkinElmer). Blotting was done with a Mini Trans-Blot apparatus (Bio-Rad) according to the manufacturer's specifications at 100 V (constant voltage) for ∼1.5 h.

The primary antibody (rabbit) was raised against the R. capsulatus RcGTA capsid protein (34). Primary antibody binding was detected with a peroxidase-linked donkey anti-rabbit Ig secondary antibody (Amersham) as part of the enhanced-chemiluminescence kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Amersham). To detect His-tagged protein, an anti-6His primary antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was used.

Purification of LexA-6His.

The R. capsulatus lexA gene was amplified as an NdeI-EcoRI fragment with primers lexA_pET28_for/rev (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) and ligated into plasmid pET28a(+), generating pETLexA, which encodes N-terminally 6His-tagged LexA (LexA-6His). Plasmid pETLexA was transformed into E. coli BL21(DE3) for protein expression.

Cultures were grown in LB medium supplemented with 50 μg ml−1 kanamycin sulfate at 30°C with shaking at 200 rpm at a starting OD600 of 0.1. At an OD600 of 0.5, expression was induced with 0.5 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) and cultures were grown to an OD600 of 1.0. Cells were harvested by centrifugation, resuspended in buffer A (5% glycerol, 50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.0], 100 mM NaCl, 2 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 1× Roche cOmplete Mini Protease Inhibitor) plus 10 mM imidazole, and then treated with 1 mg ml−1 lysozyme and 1 mg ml−1 DNase I for 1 h on ice. Cells were lysed by French press, cellular debris was removed by centrifugation, and the supernatant was loaded onto an Ni2+-nitrilotriacetic acid-agarose (Qiagen) column and washed with 30 column volumes of buffer A plus 25 mM imidazole. Protein was eluted in buffer A plus 300 mM imidazole and stored in elution buffer at −80°C. Protein purity was analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie blue staining. Samples of LexA elutions were boiled for 10 min in sample loading buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 6.8], 2% SDS, 10% glycerol, 0.1% bromophenol blue, 1% β-mercaptoethanol), and proteins were separated by 12% SDS-PAGE, stained with 40% methanol–10% acetic acid–0.025% Coomassie blue, and destained in 40% methanol–10% acetic acid. Gels stained with Coomassie blue revealed a band of ∼30 kDa at an estimated purity of >95% homogeneity. The band's identity as LexA-6His was confirmed by probing a Western blot with 6His antiserum. Protein concentrations were determined in a modified Lowry assay using BSA for the standard curve.

EMSA.

The DNA fragments used for electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) were generated by PCR with primer sets lexA_prom_for/lexA_prom_rev, recA_prom_for/recA_prom_rec, cckA_prom_for/cckA_prom_rev, and puhA_for/puhA_rev (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). The 6His-LexA protein was diluted in LexA binding buffer (20 mM Tris [pH 7.6], 50 mM KCl, 10% glycerol, 1 μM β-mercaptoethanol) to equalize the volume of protein dilution added to each binding reaction mixture. Binding of 6His-LexA to 50 nM target DNA (final concentration in DNA molecules) was done in 10-μl reaction mixtures containing LexA binding buffer, each target DNA, and dilutions of a LexA-6His solution ranging in concentration from 0 to 2 μM. Reaction mixtures were incubated at 30°C for 45 min and separated on a 5% native acrylamide gel for 60 min at 40 V (constant voltage) in TBE buffer (446 mM Tris base, 445 mM boric acid, 10 mM EDTA [pH 8.0]), at room temperature. Gels were stained with ethidium bromide and photographed with UV illumination.

qRT-PCR analysis.

Total RNA was extracted from 1.5-ml early stationary-phase cultures of the WT, ΔlexA, and ΔlexA(pLexA) strains with the RNeasy purification kit (Qiagen) and treated with DNase I (Ambion) for 1 h prior to use in quantitative reverse transcription (qRT)-PCR analysis. cDNA from each strain was generated with 1 μg of RNA with the SuperScript VILO master mix (ThermoFisher), which uses random hexamers as primers for RT, and qRT-PCR was performed with 10 ng of cDNA from each strain as a template. The primer sets used (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) were cckA_qPCR_for/lexA_qPCR_rev to quantify levels of cckA cDNA, recA_qPCR_for/recA_qPCR_rev to quantify levels of recA, orfg1_qPCR_for/orfg1_qPCR_rev to detect RcGTA orfg1 expression levels, and puhA_qPCR_for/puhA_qPCR_rev to detect puhA transcript levels as an internal control. The SYBR select master mix (Applied Biosystems) was used in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. Reaction mixtures of 20 μl containing SYBR select master mix, 400 nM specific primers, and the target template were used to quantify target DNA in an Applied Biosystems StepOnePlus real-time PCR system by using the following program: 50°C for 2 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s, 60°C for 15 s, and 72°C for 60 s (amplification) and then 95°C for 15 s, 60°C for 15 s, and 95°C for 15 s (melting curve analysis). Amplicons were clearly distinguishable from primer dimers on the basis of melting curve analysis. Amplification of targets occurred from 15 to 25 cycles. As negative controls, reaction mixtures containing no template DNA and DNase-treated RNA with no RT were included. The relative expression of each target gene was normalized to the puhA photosynthesis gene with the Applied Biosystems StepOnePlus real-time PCR ΔΔCT algorithm. Because of variability, the expression values in each run were normalized to the WT control run in parallel.

Microscopy.

Images of R. capsulatus cells from stationary-phase cultures grown in RCV defined medium at 30°C were taken with a Sony DSC-S75 digital camera mounted on a Zeiss Axioskop fluorescence microscope equipped with a 100× (oil immersion) objective.

RcGTA adsorption capability, capsule production, and conjugation capability assays.

RcGTA adsorption capability assays were done as previously described (7), with gentamicin-resistant RcGTA from DE442(pd1080) instead of rifampin resistance as a genetic marker. Conjugation recipient capability was measured as previously described (7). Capsule production was evaluated as previously described (27). In brief, phototrophic cultures of R. capsulatus were grown to the stationary phase in RCV defined medium and normalized to a density of 450 Klett units. One milliliter of culture of each strain was harvested at 14,500 × g in a tabletop microcentrifuge for 1 min, and the resultant pellets were imaged with a digital camera. A thick, loose pellet indicates the presence of a capsule polysaccharide layer surrounding cells, whereas a dense, thinner pellet indicates the absence of a capsular polysaccharide layer.

β-Galactosidase assay.

The RcGTA orfg1-lacZ, ghsA-lacZ, and dprA-lacZ promoter fusion plasmids used were described previously (5, 7, 32). Strains containing a reporter plasmid were grown phototrophically in RCV medium to the stationary phase. The β-galactosidase specific activity of cells was assayed as previously described (32, 35). Sonication was used to break cells, and total protein was measured by the Lowry method (36) with BSA as the standard. β-Galactosidase specific activities are presented in units per milligram of total protein.

RESULTS

The R. capsulatus LexA homolog is required for RcGTA production.

A transposon screen to identify new regulators of the RcGTA structural gene promoter returned LexA as a new candidate regulator. The transposon insertion mapped to bp 529 from the start of the annotated lexA coding region (rcc02361). Bioinformatic analysis indicated that the R. capsulatus and E. coli LexA amino acid sequences are only 26% identical over their entire lengths (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Much of the difference is due to ∼40 amino acids present in the R. capsulatus predicted hinge region linking the N- and C-terminal domains, while similarity is greater in the N-terminal DNA-binding region and around the key Ser119 and Lys156 residues (catalytic dyad; E. coli numbering) and Ala84 and Gly85 (flanking the peptide bond that is cleaved by the catalytic dyad) (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). On the basis of this bioinformatic analysis, the protein encoded by the annotated R. capsulatus lexA gene appears to be a genuine homolog of the E. coli LexA repressor.

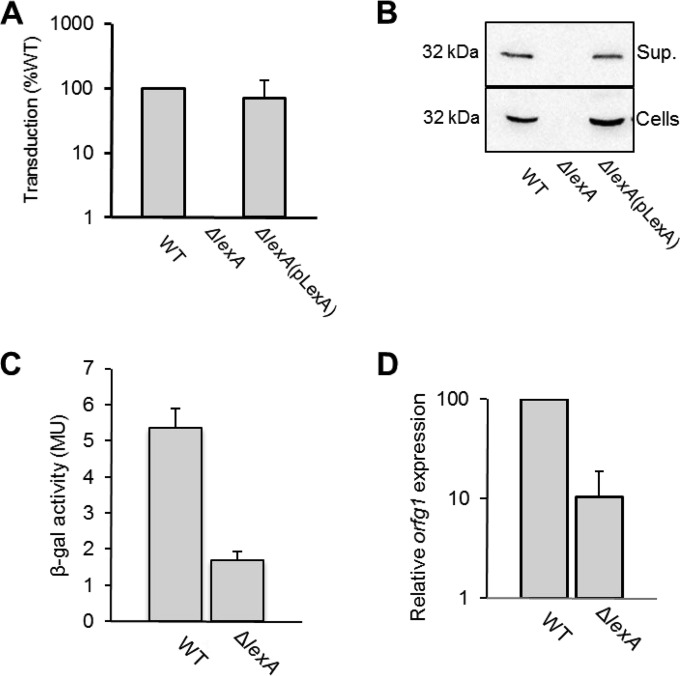

To further study the involvement of LexA in RcGTA production, we generated a markerless knockout (in-frame deletion) of the lexA (rcc02361) coding region in SB1003-derived WT strain SBpG. The resultant ΔlexA mutant strain produced no detectable RcGTA in a transduction assay (Fig. 1A), and transduction frequencies were restored to WT levels in the ΔlexA(pLexA) trans-complemented strain. Additionally, Western blots probed with RcGTA capsid protein antiserum indicated that the ΔlexA mutant did not produce capsid in either the intra- or extracellular fraction, and WT levels of capsid production were restored in the ΔlexA(pLexA) plasmid-trans-complemented strain, confirming the transduction results (Fig. 1B). The absence of detectable capsid protein from intact cells indicates that LexA is needed for transcription of the capsid gene, the 5th of 15 genes in the RcGTA structural gene major cluster, which are thought to be cotranscribed (1).

FIG 1.

RcGTA donor activity is decreased in the ΔlexA mutant because of decreased RcGTA structural gene expression. (A) RcGTA-mediated gene transfer from stationary-phase cultures of the ΔlexA mutant is undetectable, while gene transfer from the trans-complemented mutant is comparable to that from the WT. (B) Western blotting of intact cells and cell-free supernatant (Sup.) of stationary-phase cultures separated by centrifugation and probing with antisera raised against RcGTA capsid protein (rcc01687), showing that the ΔlexA mutant does not produce observable capsid. (C) β-Galactosidase (β-gal) activities of stationary-phase cultures of the WT and ΔlexA mutant strains containing an RcGTA promoter-lacZ reporter plasmid construct. MU, Miller units. (D) The relative expression of orfg1 is decreased in WT and ΔlexA strains, as measured by qRT-PCR. In the bar graphs, error bars represent the standard deviation from the mean of three biological replicates. For statistical data, see Table S3 in the supplemental material.

To confirm that the decrease in gene transfer frequency from the ΔlexA mutant is associated with a decrease in transcription of the RcGTA structural gene cluster, the β-galactosidase activities of WT and ΔlexA mutant cells containing a plasmid with the RcGTA promoter fused to lacZ were compared. We found that RcGTA promoter activity was approximately 3-fold lower in the ΔlexA mutant than in the WT (Fig. 1C). Additionally, qRT-PCR was used to directly measure the relative levels of RcGTA orfg1 (rcc01682) transcripts, and a 10-fold lower level was observed in the ΔlexA mutant than in the WT strain (Fig. 1D). Although it is not clear why the magnitude of the effect of the ΔlexA mutation with a plasmid-borne reporter as opposed to qRT-PCR differed by a factor of 3, the data are consistent in showing that the LexA protein is needed for maximal induction of RcGTA gene transcription and hence for production of RcGTA particles.

RcGTA recipient capability is decreased in the ΔlexA mutant.

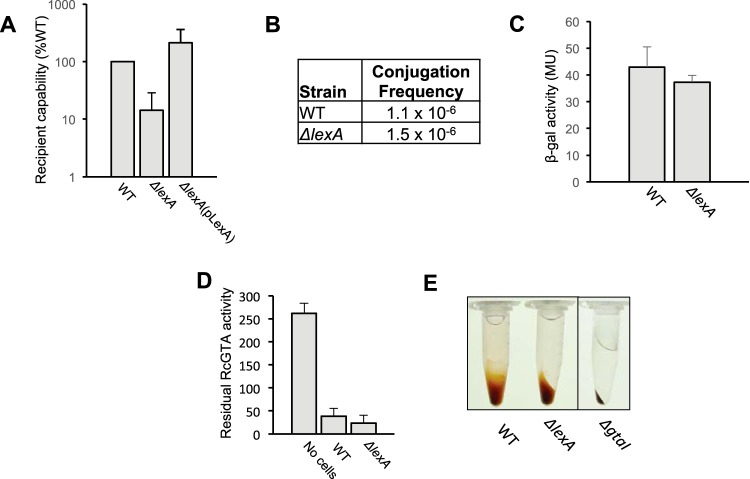

Other studies have shown that regulatory mutants with reduced RcGTA donor activity are also deficient in the ability to receive RcGTA-borne DNA (termed recipient capability) because of downregulation of competence-related genes and dprA (6, 7). The recipient capability of the ΔlexA mutant was only 14% of that of the WT strain, and this defect was rescued by providing the lexA gene in trans on plasmid pLexA (Fig. 2A).

FIG 2.

RcGTA recipient capability is decreased in the ΔlexA mutant, but the defect is independent of homologous recombination, competence genes, and RcGTA particle adsorption. (A) RcGTA-mediated gene transfer to ΔlexA mutant and WT recipient cells. (B) Conjugation frequency (number of transconjugants per recipient cell) of a suicide plasmid into WT and ΔlexA mutant cells. (C) β-Galactosidase (β-gal) activities of stationary-phase cultures of WT and the ΔlexA mutant strains containing a dprA promoter-lacZ reporter plasmid construct. MU, Miller units. (D) RcGTA adsorption capabilities of WT and ΔlexA mutant cells. In the bar graphs, error bars represent the standard deviation from the mean of three biological replicates. For statistical data, see Table S3 in the supplemental material. (E) Macroscopic examination of capsule production in WT, ΔlexA mutant, and capsule-deficient ΔgtaI mutant cells.

To establish if the ΔlexA mutant's impaired recipient capability is due to a defect in the general pathway of homologous recombination, we measured the ΔlexA mutant's ability to acquire a genetic marker on a suicide plasmid via conjugation, which requires RecA-mediated homologous recombination into the chromosome for stable acquisition of a gentamicin resistance marker (Fig. 2B) (7). We observed similar frequencies of the acquisition of suicide plasmid-borne gentamicin resistance by the WT and ΔlexA mutant strains, indicating that the ΔlexA mutant's reduced ability to acquire RcGTA-borne genetic markers is not the result of a defect in RecA-dependent recombination.

Next, we evaluated if the impaired recipient capability seen was due to a defect in the general pathway of natural transformation. To determine if the competence-related genes (com genes and dprA) are differentially regulated in the ΔlexA mutant, we compared the levels of expression of a dprA promoter-lacZ reporter fusion in WT and ΔlexA mutant strains and observed no difference (Fig. 2C). This indicates that the defect in the ΔlexA mutant's recipient capability is not due to the downregulation of dprA and presumably the other coregulated com genes (6, 7).

The RcGTA adsorption capability of the ΔlexA mutant was determined, and it was found that the ΔlexA mutant adsorbs RcGTA particles with an affinity similar to that of the WT strain (Fig. 2D). Furthermore, on the basis of a macroscopic assay, it was found that WT and ΔlexA mutant cells form similar levels of capsule, a binding receptor for RcGTA (27), compared to the capsule-deficient quorum-sensing ΔgtaI mutant strain (Fig. 3E).

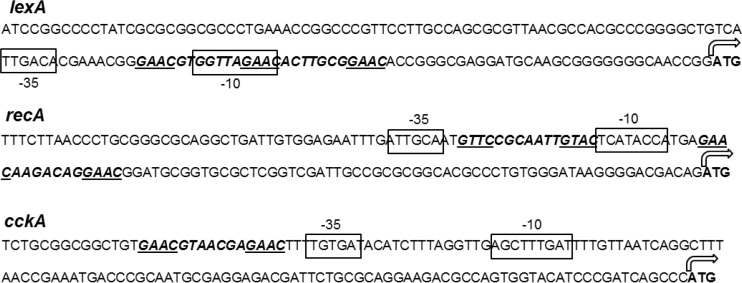

FIG 3.

Sequences located 5′ of the R. capsulatus lexA, recA, and cckA coding regions, showing putative SOS boxes (in bold with binding recognition tetramers underlined) and predicted promoter elements.

Taken together, these results indicate that the defect in RcGTA recipient capability is at some stage after particle adsorption to cells and independent of the homologous-recombination and natural-transformation-like pathways.

Putative LexA binding sites are present 5′ of SOS response gene homologs and the RcGTA regulatory gene cckA.

The requirement of lexA for RcGTA production and maximal recipient capability prompted a search for putative LexA binding sites (SOS boxes) in the R. capsulatus genome. Previous studies have proposed the SOS box motif GTTCN7GT(A/T)C for R. capsulatus recA and uvrA genes (37) and identified the nearly identical motif GTTCN7G(A/T)TC for the closely related species R. sphaeroides (38). Using these sequences as a query in a search of the R. capsulatus WT strain SB1003 genome, we found SOS boxes upstream of canonical SOS response genes, including putative DNA repair enzymes and lexA itself (Table 2 and Fig. 3; see Table S2 in the supplemental material). Additionally, an SOS box was found 121 bp 5′ of the start codon of cckA (Table 2; Fig. 3), which encodes a hybrid sensor kinase homolog that is a component of an RcGTA regulatory system (4, 12). We hypothesized that the R. capsulatus LexA protein binds to promoter regions containing these SOS boxes and that binding represses the transcription of these genes, and we tested this hypothesis as described in the following text.

TABLE 2.

R. capsulatus chromosomal ORFs that have a putative SOS boxa within 300 bp 5′ of the start codon and predicted SOS response, DNA repair, or RcGTA regulatory functions

| ORF | Annotation |

|---|---|

| ORFs for SOS response regulators | |

| rcc02361 | LexA protein |

| rcc01751 | RecA protein |

| ORFs for DNA repair enzymes | |

| rcc00038 | Double-strand break repair protein AddB |

| rcc00138 | Error-prone DNA polymerase |

| rcc00139 | Nucleotidyltransferase/DNA polymerase involved in DNA repair |

| rcc00854 | Arginyl-tRNA synthetase |

| rcc01384 | UvrABC system protein B |

| rcc01491 | DNA helicase II |

| rcc01558 | UvrABC system protein A |

| RcGTA regulator rcc01749 | CckA signal transduction histidine kinase |

GTTCN7GT(A/T)C or GTTCN7G(A/T)TC.

R. capsulatus LexA binds to the predicted promoter regions of lexA, recA, and cckA and represses cckA and recA transcription.

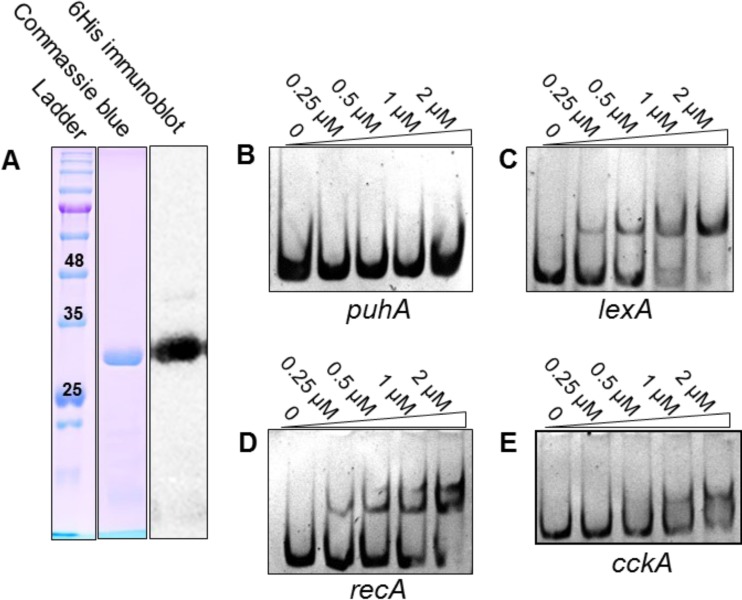

To evaluate the DNA-binding properties of R. capsulatus LexA, recombinant LexA-6His, was purified (Fig. 4A) and used in EMSAs of DNA fragments. EMSAs using an internal segment of the puhA photosynthesis gene that does not contain an SOS box showed no alteration in mobility after incubation with LexA-6His concentrations ranging from 0 to 2 μM (Fig. 4B). EMSAs of DNA fragments from the 5′ regions of the lexA and recA genes, which contain Rhodobacter SOS boxes and are canonical SOS response genes, showed bands of decreased mobility, the intensity of which increased with an increase in the concentration of LexA-6His (Fig. 4C and D). These data indicate that LexA-6His bound specifically to these fragments. A fragment of DNA upstream of the cckA gene, which contains a single SOS box, was also tested for LexA binding, and a band of decreased mobility was observed (Fig. 4E). In comparison to the negative-control puhA fragment, the cckA fragment clearly showed a mobility shift, although higher concentrations of LexA-6His were required for a visible shift compared to the lexA and recA fragments, which both contain two SOS boxes. These data indicate that R. capsulatus LexA binds to the lexA and recA 5′ regions with similar affinities and to the cckA 5′ region with less affinity.

FIG 4.

R. capsulatus LexA binds specifically to DNA fragments containing the putative SOS boxes of lexA, recA, and cckA. (A) SDS-PAGE of purified LexA-6His stained with Coomassie blue and confirmed by anti-6His immunoblotting. The values in the leftmost lane are molecular sizes in kilodaltons. (B to E) EMSAs of DNA fragments containing 5′ sequences of puhA (negative control with no SOS box), lexA, recA (canonical SOS response gene with two SOS boxes), and cckA (RcGTA regulator with a putative SOS box) using increasing concentrations of purified LexA-6His, as indicated above the gels. The concentration of target DNA was held constant at 50 nM.

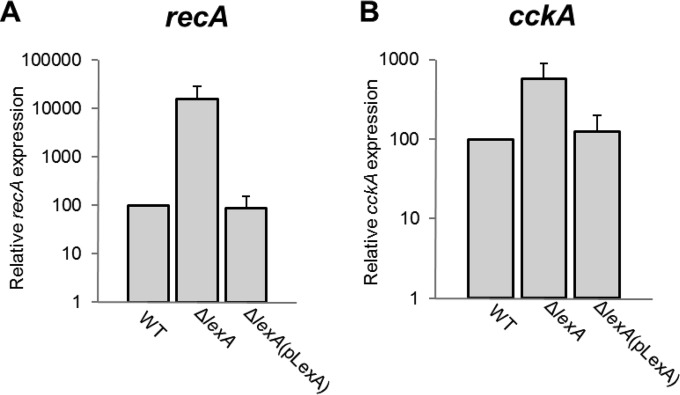

LexA-mediated repression of recA expression is a hallmark of the prototypical SOS response. To determine if the EMSA data showing LexA binding to the region 5′ of the recA ORF correlated with LexA repression of recA transcription, we performed qRT-PCR analysis of recA transcript levels in the WT, ΔlexA, and ΔlexA(pLexA) strains. Approximately 150-fold higher recA expression was found in the ΔlexA mutant than in the WT strain, and WT levels of recA expression were obtained in the ΔlexA(pLexA) complemented strain (Fig. 5A). These data confirm that LexA regulates recA expression and that this regulation is due to direct repression, as in typical SOS response systems.

FIG 5.

LexA negatively regulates recA and cckA transcription. qRT-PCR of recA (A) and cckA (B) transcript levels in the WT, ΔlexA mutant, and trans-complemented ΔlexA mutant strains.

To evaluate whether cckA expression is modulated by LexA, we measured cckA expression by qRT-PCR analysis to compare the levels of cckA transcripts in the WT, ΔlexA mutant, and ΔlexA(pLexA) complemented strains. It was found that cckA expression in the ΔlexA mutant was approximately 5.6 times that of the WT strain, and in the ΔlexA(pLexA) complemented strain, cckA expression was similar to that of the WT (Fig. 5B).

Taken together, these data indicate that LexA negatively regulates the transcription of SOS genes and also cckA. Because of the in vitro binding of purified LexA-6His to the cckA fragment (Fig. 4E), this repression of cckA expression appears to be due to LexA binding to the cckA promoter region.

Epistatic interaction between lexA and cckA.

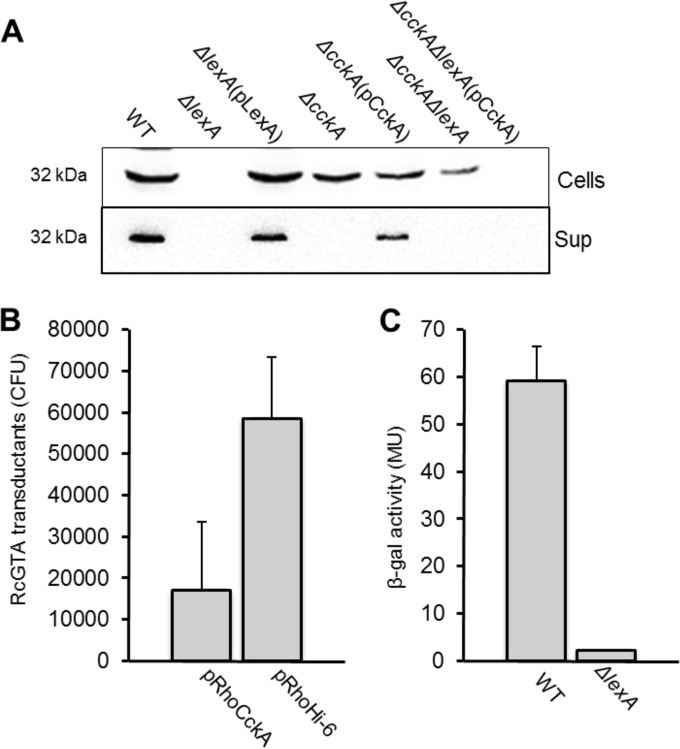

To further evaluate the genetic interaction between lexA and cckA, a ΔlexA ΔcckA double mutant was generated, and RcGTA capsid production and release were evaluated in this strain, relative to those in ΔlexA and ΔcckA single gene mutants. We hypothesized that constitutive derepression of cckA transcription resulting from the deletion of lexA caused increased production of CckA and contributed to the RcGTA-deficient lexA phenotype. Therefore, we determined whether deletion of cckA from the ΔlexA mutant would at least partially rescue the ΔlexA defect and mimic the phenotype of a ΔcckA single mutant (capsid production and intracellular accumulation due to a lysis deficiency) (4).

Cultures of the WT strain, the ΔlexA and ΔcckA single mutants, and the ΔlexA ΔcckA double mutant were grown to the stationary phase and evaluated for RcGTA production by Western blot assay probed with capsid antiserum (Fig. 6A). As previously reported (4, 12), we found that the RcGTA capsid was detectable in the cell fraction from the ΔcckA mutant but not in the cell-free culture supernatant. As in Fig. 1, the ΔlexA mutant again lacked the RcGTA capsid in the cell and culture supernatant fractions (Fig. 6A). However, the phenotype of the ΔlexA ΔcckA double mutant differs from that of the ΔlexA single mutant in that the RcGTA capsid was detected in the cell fraction of the double mutant and none was released from cells. This is similar to the ΔcckA single mutant phenotype, although the intensity of the band was less than that seen in the ΔcckA single mutant. To confirm that expression of the cckA gene alone contributed to the ΔlexA ΔcckA phenotype, the cckA gene was reintroduced into the ΔlexA ΔcckA double mutant on complementing plasmid pCckA, and the ΔlexA single mutant phenotype (the absence of the capsid protein) was restored (Fig. 6A).

FIG 6.

Epistatic interaction between lexA and cckA. (A) Immunoblot assay of intact cells and cell-free supernatant (Sup) of stationary-phase cultures and probing with antiserum raised against the RcGTA capsid protein (rcc01687), showing that the capsid-deficient phenotype of the ΔlexA mutant depends on the presence of cckA. (B) Expression of cckA driven by the constitutive aphII (kanamycin resistance) promoter results in less RcGTA-mediated transduction from the WT strain than from an empty-plasmid control. (C) β-Galactosidase (β-gal) activities of WT and ΔlexA mutant cells with a lacZ reporter fused to the CtrA∼P-dependent ghsA/ghsB promoter, indicating that cckA overexpression in the ΔlexA mutant does not result in increased levels of CtrA∼P. MU, Miller units.

These results show an epistatic relationship between lexA and cckA, where the deletion of cckA from a ΔlexA mutant restores intracellular RcGTA capsid production. Therefore, the absence of capsid production in the ΔlexA mutant is dependent on cckA, a gene that is overexpressed in the ΔlexA mutant because LexA represses cckA directly.

We reasoned that if overexpression of the CckA protein represses RcGTA structural gene expression in the ΔlexA mutant, increased expression of the cckA gene in a WT strain would also decrease the production of RcGTA particles. This idea was tested by using the constitutive aphII (kanamycin resistance) promoter of plasmid pRhokHi-6 (39) to increase cckA expression in the WT strain. Indeed, it was found that constitutive expression of cckA resulted in a decrease in transduction frequency, compared to the empty-plasmid control (Fig. 6B).

The absence of capsid in the ΔlexA mutant is not explained by CtrA phosphorylation.

The CckA protein of C. crescentus has been reported to be bifunctional, acting as either a kinase or a phosphatase, depending on the level of cckA expression. Overexpression of cckA in C. crescentus was reported to result in a cellular environment where CckA acts primarily as a phosphatase, resulting in a lack of phosphorylated CtrA (40). However, nonphosphorylated CtrA was shown to stimulate RcGTA capsid production (12), in contrast to the absence of capsid production by the ΔlexA mutant (Fig. 1B). We therefore tested if the overexpression of cckA in the ΔlexA mutant increased the levels of CtrA phosphorylation. This was determined by measuring the activity of a CtrA∼P-dependent promoter. Expression of ghsA and ghsB, the genes encoding the RcGTA head spike, requires CckA, ChpT, and CtrA (5) and is greatly stimulated by CtrA∼P (A. B. Westbye, unpublished data). Promoter activity in ΔlexA mutant cells containing the pXCA-ghsA reporter plasmid was reduced to 1.8% of the levels in WT cells (Fig. 6C), indicating that cckA overexpression in the ΔlexA mutant does not result in increased levels of CtrA∼P.

Morphology of ΔlexA mutant cells.

In other bacteria, lexA mutants have been observed to form elongated, filamentous cells compared to those of a WT strain (41), and this phenotype is common in an SOS response (42, 43). The severity of cell elongation is species specific and appears to be due to a decrease in septum formation in cell division (44). To determine whether the R. capsulatus ΔlexA mutant forms elongated cells, we examined WT, ΔlexA, and ΔlexA(pLexA) cells by phase-contrast microscopy. It was found that, like ΔlexA mutants of other bacterial species, the R. capsulatus ΔlexA mutant forms elongated, sometimes filamentous cells, and cells of the ΔlexA(pLexA) complemented strain return to a WT-like morphology (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). Therefore, the absence of LexA in R. capsulatus appears to result in a modest impairment of cell septum formation. In contrast to the effect on RcGTA production, the addition of the ΔcckA mutation in the ΔlexA background did not abrogate cell elongation.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we demonstrate that the rcc02361 gene product functions as the LexA homolog of R. capsulatus and participates in the regulation of RcGTA. The lexA gene is required for RcGTA production, and LexA represses the transcription of cckA, which was previously found to be needed for maturation and release of RcGTA particles from cells (4, 12). Furthermore, it is shown that recipient capability is greatly affected by the presence of lexA. Although connections have been identified between the SOS response and other forms of horizontal gene transfer that share features with RcGTA, such as natural transformation and phage-mediated transduction, the relationship of RcGTA with the SOS response appears to be unique in several aspects, as described in the following sections.

cckA as part of the LexA regulon.

LexA appears to directly repress the expression of the histidine kinase homolog CckA, which is involved in the CckA-ChpT-CtrA phosphorelay that regulates several aspects of RcGTA biology, including production, recipient capability, particle maturation, and particle release (4, 6, 7, 12). Because an SOS box is present in the promoter sequence of cckA in environmental isolates B6, YW1, and YW2 (data not shown), whose genomes have been sequenced, in addition to strain SB1003, repression of cckA by LexA appears to be conserved in all strains of R. capsulatus. In contrast, no convincing SOS box (45) was detected in the promoter region of CckA for the other well-studied alphaproteobacteria R. sphaeroides, C. crescentus, Agrobacterium tumefaciens, Sinorhizobium meliloti, and Brucella melitensis (data not shown). Therefore, among these species, repression of cckA by LexA appears to be unique to R. capsulatus.

Because LexA-6His bound to a DNA fragment containing the cckA SOS box, LexA appears to directly repress cckA transcription and cckA transcripts were greatly increased in the ΔlexA mutant. We propose that the ΔlexA mutant's capsid-deficient phenotype is largely the result of this cckA overexpression because of the strong epistasis we observed: the deletion of cckA largely restored capsid production in the ΔlexA background, where it was otherwise undetectable (Fig. 6A). The effect of cckA overexpression in the ΔlexA mutant on downstream pathways is unclear, however, and the phenotype of the ΔlexA mutant diverges from predictions based on existing models of CckA-ChpT-CtrA interaction in C. crescentus and R. capsulatus.

In C. crescentus, in which the CckA-CtrA phosphorelay has been best studied, CckA has both kinase and phosphatase activities; the phosphatase activity is default, and kinase activity is stimulated by interaction with the protein DivL (46). Overexpression of CckA in C. crescentus was shown to result in the dephosphorylation of CtrA (40), apparently because the CckA proteins in stoichiometric excess of DivL proteins do not have their kinase activity stimulated and behave as phosphatases by default.

On the basis of the C. crescentus model, it would be predicted that excess CckA protein present in the ΔlexA mutant is predominantly in a phosphatase state, resulting in decreased CtrA phosphorylation. However, the phenotype of the ΔlexA mutant does not match the previously reported phenotypes resulting from an absence of CtrA phosphorylation. An increase in intracellular RcGTA capsid production was observed for an R. capsulatus mutant expressing a ctrA allele that cannot be phosphorylated (12). Similarly, a ΔcckA knockout, which should not be capable of phosphorylating CtrA, was shown to produce the RcGTA capsid protein (4, 12). These previous findings demonstrate that capsid protein is produced in cells that contain unphosphorylated CtrA. In the ΔlexA mutant, however, there is no detectable capsid protein. This made us speculate that the overexpression of cckA in the ΔlexA mutant caused overphosphorylation of CtrA that, by an unknown mechanism, abolished capsid production. However, expression of the CtrA∼P-dependent ghsA/ghsB promoter was dramatically reduced in the ΔlexA mutant, indicating that no overphosphorylation of CtrA occurred.

Taken together, our results are not consistent with a model of the R. capsulatus CckA-ChpT-CtrA phosphorelay in which CckA only regulates the phosphorylation state of CtrA. An intriguing possibility is that cckA overexpression in R. capsulatus causes a decrease in cellular CtrA. In C. crescentus, CckA regulates proteolytic degradation of CtrA by controlling the phosphorylation state of CpdR (47). Furthermore, the absence of detectable capsid in the ΔlexA mutant resembles a ΔctrA mutant, which also lacks capsid production (12). However, we observed that the activity of the CtrA-dependent dprA promoter (7) was not altered in the ΔlexA mutant. Therefore, the ΔlexA mutant must produce sufficient CtrA protein for this and presumably other CtrA-dependent promoters to be active. Ultimately, our results and the phenotypes of the ΔlexA mutant reveal that regulation of RcGTA by the CckA-ChpT-CtrA phosphorelay is more complex than previously believed.

The SOS response and RcGTA production.

The involvement of LexA in the regulation of RcGTA capsid production might appear to indicate a role for the SOS response in RcGTA induction. Nonetheless, we suggest that the phenotype of the ΔlexA mutant has limited usefulness when it comes to speculating how LexA activation during the SOS response might affect RcGTA, especially through pathways regulated by the CckA-ChpT-CtrA phosphorelay. We suggest that overexpression of the lexA regulon is artificially exaggerated in the ΔlexA mutant compared to the upregulation of the lexA regulon that occurs during the SOS response in a WT cell. Because LexA appears to repress its own expression in R. capsulatus (Fig. 4) as in other species (13), self-cleaved LexA would result in derepression of the lexA gene, limiting the magnitude and duration of SOS induction (depending on the extent and duration of DNA damage). This feedback inhibition would not occur in the ΔlexA mutant because the LexA coding region was deleted, which allows for a magnitude of lexA regulon overexpression that may be exaggerated. This indicates that the overexpression of cckA in the ΔlexA mutant would not be comparable to the upregulation of cckA during an SOS response in a WT cell. Indeed, it was previously shown that mitomycin C-induced expression of the SOS response genes recA and uvrA in R. capsulatus was modest (4.5- and 2.1-fold, respectively, based on lacZ reporter plasmids) (37) compared to the approximately 150-fold increase in recA induction we observed in the ΔlexA mutant.

Comparison to LexA involvement in the bacteriophage life cycle and natural competence.

The finding that the R. capsulatus lexA homolog is involved in the regulation of both RcGTA particle production and recipient capability indicates a complex connection between the SOS response and the RcGTA gene transfer process.

The lytic cycle of some lysogenic bacteriophages is induced when the host cell's SOS response becomes active. This has been extensively studied in lambdoid Siphoviridae, a group of bacteriophages with which RcGTA has an ancestor of some structural genes in common (1). In these phages, the conditions that activate LexA cleavage result in prophage induction because the factors that initiate lysis are under direct repression by LexA or LexA homologs (18).

The results of this study indicate that the role of LexA in RcGTA regulation diverges from the one it plays in lysogenic phage induction. Deletion of lexA resulted in the absence of RcGTA production, and there is no SOS box 5′ of the RcGTA structural genes. Instead, we found that LexA modulates capsid production, and presumably the other genes encoding proteins of the RcGTA particle, by repressing the expression of cckA, which encodes a putative bidirectional signal transduction protein in a phosphorelay system. Because CtrA, the response regulator of this phosphorelay, does not directly control the transcription of RcGTA structural genes (1), this role for LexA is well upstream in the RcGTA induction pathway compared to its role in pathways that lead to prophage induction.

The connections between the SOS response and natural transformation have not been extensively studied. Because some organisms lack a LexA homolog that represses DNA repair functions and have no conventional SOS response, it has been proposed that natural transformation acts as an SOS response substitute, with incoming DNA used for repair in Campylobacter jejuni, Legionella pneumophila, and some streptococcal species (48–50). In studies of Streptococcus thermophilus, which is naturally transformable and also contains a lexA homolog, it was found that SOS and transformation appear to be antagonistic processes: disruption of the lexA homolog hdiR reduced transformability, and treatment with mitomycin C reduced transformability and downregulated com genes (51).

The significance of the antagonistic effect found in S. thermophilus is unclear in the context of R. capsulatus and RcGTA. On the one hand, an antagonism appears to exist when the R. capsulatus lexA regulon is constitutively derepressed, because recipient capability was greatly reduced in the ΔlexA mutant. As explained above, however, the extent to which the RcGTA phenotype of the ΔlexA mutant mimics a WT cell during the SOS response is unclear because of the exaggerated upregulation of the lexA regulon caused by deletion of the lexA coding region. This is especially complicated when evaluating the RcGTA production and recipient capability systems that are regulated by the CckA-ChpT-CtrA phosphorelay, because CckA may have opposing activities, depending on the magnitude of expression. Furthermore, our results showed that dprA is not differentially expressed in the ΔlexA mutant, and because competence genes are coregulated with dprA, they are likely not differentially expressed (6, 7).

In summary, our results show that any connection existing between an SOS response and RcGTA induction and recipient capability is fundamentally different from those existing between the SOS response and other forms of horizontal gene transfer in other species with which RcGTA has features in common. These findings contribute to an emerging view that the origin and evolution of RcGTA are much more complex than those of a simply defective or hijacked prophage.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Sarah Thompson for expert technical assistance.

We thank the Canadian Institutes of Health Research for operating grants (93779 and 142720 to J.T.B.) and the University of British Columbia for a postgraduate scholarship (to C.A.B.).

K.S.K., C.A.B., H.D., and A.B.W. designed research, performed experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript. J.T.B. designed research, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JB.00839-15.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lang AS, Zhaxybayeva O, Beatty JT. 2012. Gene transfer agents: phage-like elements of genetic exchange. Nat Rev Microbiol 10:472–482. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hynes AP, Mercer RG, Watton DE, Buckley CB, Lang AS. 2012. DNA packaging bias and differential expression of gene transfer agent genes within a population during production and release of the Rhodobacter capsulatus gene transfer agent, RcGTA. Mol Microbiol 85:314–325. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2012.08113.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fogg PCM, Westbye AB, Beatty JT. 2012. One for all or all for one: heterogeneous expression and host cell lysis are key to gene transfer agent activity in Rhodobacter capsulatus. PLoS One 7:e43772. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Westbye AB, Leung MM, Florizone SM, Taylor TA, Johnson JA, Fogg PC, Beatty JT. 2013. Phosphate concentration and the putative sensor kinase protein CckA modulate cell lysis and release of the Rhodobacter capsulatus gene transfer agent. J Bacteriol 195:5025–5040. doi: 10.1128/JB.00669-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Westbye AB, Kuchinski K, Yip CK, Beatty JT. 2016. The gene transfer agent RcGTA contains head spikes needed for binding to the Rhodobacter capsulatus polysaccharide cell capsule. J Mol Biol 428:477–491. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2015.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brimacombe CA, Ding H, Johnson JA, Beatty JT. 2015. Homologues of genetic transformation DNA import genes are required for Rhodobacter capsulatus gene transfer agent recipient capability regulated by the response regulator CtrA. J Bacteriol 197:2653–2663. doi: 10.1128/JB.00332-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brimacombe CA, Ding H, Beatty JT. 2014. Rhodobacter capsulatus DprA is essential for RecA-mediated gene transfer agent (RcGTA) recipient capability regulated by quorum-sensing and the CtrA response regulator. Mol Microbiol 92:1260–1278. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schaefer AL, Taylor TA, Beatty JT, Greenberg EP. 2002. Long-chain acyl-homoserine lactone quorum-sensing regulation of Rhodobacter capsulatus gene transfer agent production. J Bacteriol 184:6515–6521. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.23.6515-6521.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Solioz M, Yen HC, Marris B. 1975. Release and uptake of gene transfer agent by Rhodopseudomonas capsulata. J Bacteriol 123:651–657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brilli M, Fondi M, Fani R, Mengoni A, Ferri L, Bazzicalupo M, Biondi EG. 2010. The diversity and evolution of cell cycle regulation in alpha-proteobacteria: a comparative genomic analysis. BMC Syst Biol 4:52. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-4-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lang AS, Beatty JT. 2000. Genetic analysis of a bacterial genetic exchange element: the gene transfer agent of Rhodobacter capsulatus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97:859–864. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.2.859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mercer RG, Quinlan M, Rose AR, Noll S, Beatty JT, Lang AS. 2012. Regulatory systems controlling motility and gene transfer agent production and release in Rhodobacter capsulatus. FEMS Microbiol Lett 331:53–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2012.02553.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Butala M, Zgur-Bertok D, Busby SJ. 2009. The bacterial LexA transcriptional repressor. Cell Mol Life Sci 66:82–93. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8378-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yeiser B, Pepper ED, Goodman MF, Finkel SE. 2002. SOS-induced DNA polymerases enhance long-term survival and evolutionary fitness. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99:8737–8741. doi: 10.1073/pnas.092269199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marrs B. 1974. Genetic recombination in Rhodopseudomonas capsulata. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 71:971–973. doi: 10.1073/pnas.71.3.971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Erill I, Campoy S, Barbé J. 2007. Aeons of distress: an evolutionary perspective on the bacterial SOS response. FEMS Microbiol Rev 31:637–656. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2007.00082.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gutekunst K, Phunpruch S, Schwarz C, Schuchardt S, Schulz-Friedrich R, Appel J. 2005. LexA regulates the bidirectional hydrogenase in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 as a transcription activator. Mol Microbiol 58:810–823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lemire S, Figueroa-Bossi N, Bossi L. 2011. Bacteriophage crosstalk: coordination of prophage induction by trans-acting antirepressors. PLoS Genet 7:e1002149. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bunny K, Liu J, Roth J. 2002. Phenotypes of lexA mutations in Salmonella enterica: evidence for a lethal lexA null phenotype due to the Fels-2 prophage. J Bacteriol 184:6235–6249. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.22.6235-6249.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Simon R, Priefer U, Pühler A. 1983. A broad host range mobilization system for in vivo genetic engineering: transposon mutagenesis in Gram negative bacteria. Nat Biotechnol 1:784–791. doi: 10.1038/nbt1183-784. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mercer RG, Callister SJ, Lipton MS, Pasa-Tolic L, Strnad H, Paces V, Beatty JT, Lang AS. 2010. Loss of the response regulator CtrA causes pleiotropic effects on gene expression but does not affect growth phase regulation in Rhodobacter capsulatus. J Bacteriol 192:2701–2710. doi: 10.1128/JB.00160-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yen HC, Hu NT, Marrs BL. 1979. Characterization of the gene transfer agent made by an overproducer mutant of Rhodopseudomonas capsulata. J Mol Biol 131:157–168. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(79)90071-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ding H, Moksa MM, Hirst M, Beatty JT. 2014. Draft genome sequences of six Rhodobacter capsulatus strains, YW1, YW2, B6, Y262, R121, and DE442. Genome Announc 2:e00050-14. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00050-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wall JD, Weaver PF, Gest H. 1975. Gene transfer agents, bacteriophages, and bacteriocins of Rhodopseudomonas capsulata. Arch Microbiol 105:217–224. doi: 10.1007/BF00447140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beatty JT, Gest H. 1981. Biosynthetic and bioenergetic functions of citric acid cycle reactions in Rhodopseudomonas capsulata. J Bacteriol 148:584–593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brimacombe CA, Stevens A, Jun D, Mercer R, Lang AS, Beatty JT. 2013. Quorum-sensing regulation of a capsular polysaccharide receptor for the Rhodobacter capsulatus gene transfer agent (RcGTA). Mol Microbiol 87:802–817. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li C, Wen A, Shen B, Lu J, Huang Y, Chang Y. 2011. FastCloning: a highly simplified, purification-free, sequence- and ligation-independent PCR cloning method. BMC Biotechnol 11:92. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-11-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aklujkar M, Harmer AL, Prince RC, Beatty JT. 2000. The orf162b sequence of Rhodobacter capsulatus encodes a protein required for optimal levels of photosynthetic pigment-protein complexes. J Bacteriol 182:5440–5447. doi: 10.1128/JB.182.19.5440-5447.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marx CJ, Lidstrom ME. 2001. Development of improved versatile broad-host-range vectors for use in methylotrophs and other Gram-negative bacteria. Microbiology 147:2065–2075. doi: 10.1099/00221287-147-8-2065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Larsen RA, Wilson MM, Guss AM, Metcalf WW. 2002. Genetic analysis of pigment biosynthesis in Xanthobacter autotrophicus Py2 using a new, highly efficient transposon mutagenesis system that is functional in a wide variety of bacteria. Arch Microbiol 178:193–201. doi: 10.1007/s00203-002-0442-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leung MM, Brimacombe CA, Spiegelman GB, Beatty JT. 2012. The GtaR protein negatively regulates transcription of the gtaRI operon and modulates gene transfer agent (RcGTA) expression in Rhodobacter capsulatus. Mol Microbiol 83:759–774. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07963.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Adams CW, Forrest ME, Cohen SN, Beatty JT. 1989. Structural and functional analysis of transcriptional control of the Rhodobacter capsulatus puf operon. J Bacteriol 171:473–482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Taylor TA. 2004. Evolution and regulation of the gene transfer agent (GTA) of Rhodobacter capsulatus. M.S. thesis. University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Leung MM-L. 2010. CtrA and GtaR: two systems that regulate the gene transfer agent of Rhodobacter capsulatus. Ph.D. dissertation. University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Peterson G. 1983. Determination of total protein. Methods Enzymol 91:95–119. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(83)91014-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Labazi M, del Rey A, Fernández de Henestrosa AR, Barbé J. 1999. A consensus sequence for the Rhodospirillaceae SOS operators. FEMS Microbiol Lett 171:37–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb13409.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fernández de Henestrosa AR, Rivera E, Tapias A, Barbé J. 1998. Identification of the Rhodobacter sphaeroides SOS box. Mol Microbiol 28:991–1003. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00860.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Katzke N, Arvani S, Bergmann R, Circolone F, Markert A, Svensson V, Jaeger KE, Heck A, Drepper T. 2010. A novel T7 RNA polymerase dependent expression system for high-level protein production in the phototrophic bacterium Rhodobacter capsulatus. Protein Expr Purif 69:137–146. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2009.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen YE, Tsokos CG, Biondi EG, Perchuk BS, Laub MT. 2009. Dynamics of two phosphorelays controlling cell cycle progression in Caulobacter crescentus. J Bacteriol 191:7417–7429. doi: 10.1128/JB.00992-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Howe W, Mount D. 1979. Distribution of cell lengths in cultures of a lexA mutant of Escherichia coli K-12. J Bacteriol 138:273–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Crowley DJ, Courcelle J. 2002. Answering the call: coping with DNA damage at the most inopportune time. J Biomed Biotechnol 2:66–74. doi: 10.1155/S1110724302202016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huisman O, D'Ari R, Gottesman S. 1984. Cell-division control in Escherichia coli: specific induction of the SOS function SfiA protein is sufficient to block septation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 81:4490–4494. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.14.4490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hill TM, Sharma B, Valjavec-Gratian M, Smith J. 1997. sfi-independent filamentation in Escherichia coli is lexA dependent and requires DNA damage for induction. J Bacteriol 179:1931–1939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Erill I, Jara M, Salvador N, Escribano M, Campoy S, Barbé J. 2004. Differences in LexA regulon structure among proteobacteria through in vivo assisted comparative genomics. Nucleic Acids Res 32:6617–6626. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tsokos CG, Perchuk BS, Laub MT. 2011. A dynamic complex of signaling proteins uses polar localization to regulate cell-fate asymmetry in Caulobacter crescentus. Dev Cell 20:329–341. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Iniesta AA, McGrath PT, Reisenauer A, McAdams HH, Shapiro L. 2006. A phospho-signaling pathway controls the localization and activity of a protease complex critical for bacterial cell cycle progression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103:10935–10940. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604554103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Žgur-Bertok D. 2013. DNA damage repair and bacterial pathogens. PLoS Pathog 9:e1003711. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gasc AM, Sicard N, Claverys JP, Sicard AM. 1980. Lack of SOS repair in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Mutat Res 70:157–165. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(80)90155-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Prudhomme M, Attaiech L, Sanchez G, Martin B, Claverys JP. 2006. Antibiotic stress induces genetic transformability in the human pathogen Streptococcus pneumoniae. Science 313:89–92. doi: 10.1126/science.1127912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Boutry C, Delplace B, Clippe A, Fontaine L, Hols P. 2013. SOS response activation and competence development are antagonistic mechanisms in Streptococcus thermophilus. J Bacteriol 195:696–707. doi: 10.1128/JB.01605-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Strnad H, Lapidus A, Paces J, Ulbrich P, Vlcek C, Paces V, Haselkorn R. 2010. Complete genome sequence of the photosynthetic purple nonsulfur bacterium Rhodobacter capsulatus SB 1003. J Bacteriol 192:3545–3546. doi: 10.1128/JB.00366-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Keen NT, Tamaki S, Kobayashi D, Trollinger D. 1988. Improved broad-host-range plasmids for DNA cloning in gram-negative bacteria. Gene 70:191–197. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90117-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.