INTRODUCTION

The American Society of Anesthesiologists Physical Status (ASA-PS) classification is a widely used grading system for the pre-operative health of a surgical patient. It was originally developed in 1941 by Saklad et al. and then modified in 1961 by Dripps et al.[1] into a five-class version.

According to other researchers, the ASA-PS classification should be modified and adapted to the paediatric population because there are many differences between the physiology and pathology of adults and children. Many studies have tested the relation between the ASA classification and several outcomes[2,3] such as mortality, cardiac arrest, morbidity, length of stay and predictors of blood loss. The reliability of the ASA-PS classification has been widely evaluated,[4,5] but there are different conclusions on the ASA-PS classification reliability. There is no agreement on the level of reliability of the scale.

We conducted a systematic review on the state of studies on the reliability of the ASA-PS classification. To our knowledge, there is only one review on the ASA-PS classification,[6] and there are no systematic reviews on its reliability.

The primary aim was to check the state of studies on the reliability of the ASA-PS classification for the broad population of adults and children waiting for surgery.

METHODS

The questions for the review were as follows: (1) What is the level of reliability of the ASA-PS system among the selected studies? (2) How is the quality of reporting among published studies on reliability of the ASA-PS system? (3) How is the quality of statistical methodology among published studies on reliability of the ASA-PS system?

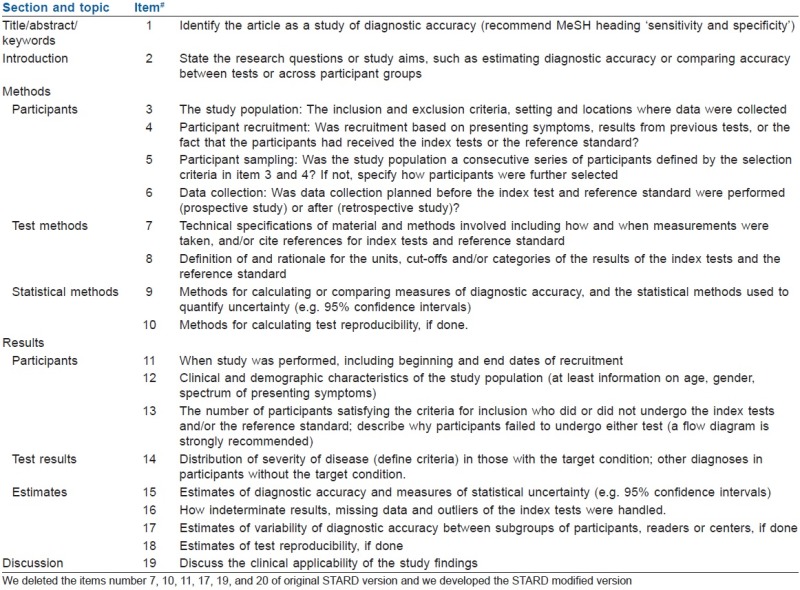

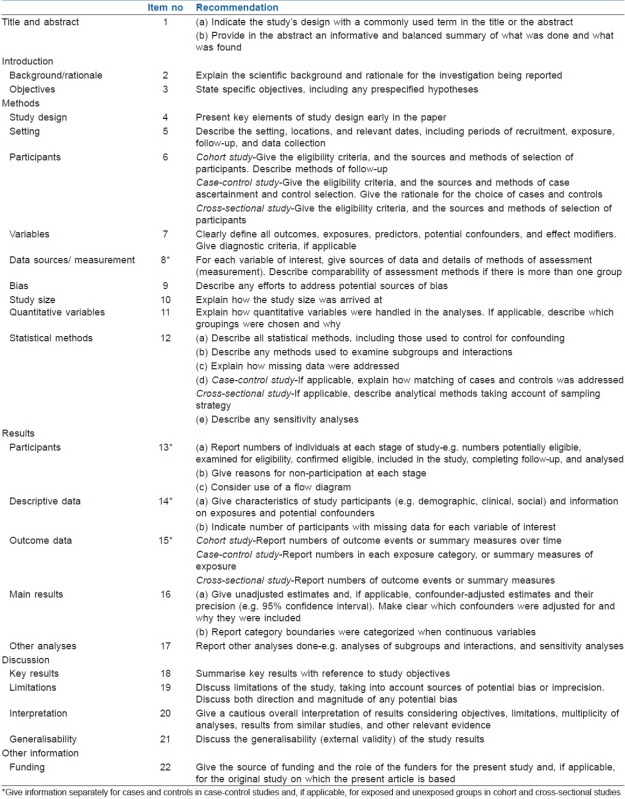

We used the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Guideline for the first part of the review protocol, the selection of studies. Then, we used a modified version of the Standards for the Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy (STARD)[7] and Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Guidelines (http://www.strobe-statement.org) to analyse the quality of reporting among studies selected [Appendix 1 and 2]. Finally, we used the Statistical Analyses and Methods in the Published Literature (SAMPL) Guidelines (http://www.equator-network.org/reporting-guidelines/sampl) to test the quality of statistical methodology among the collected studies.

The outcome measures were reliability tested using the k statistic, Cohen's kappa or the intra-class correlation coefficient; the percentage of STARD, STROBE, SAMPL items respected.

The inclusion and exclusion criteria and the methodology to assess the risk bias (of individual studies and of the cumulative evidence of included studies) are shown in Appendix 3.

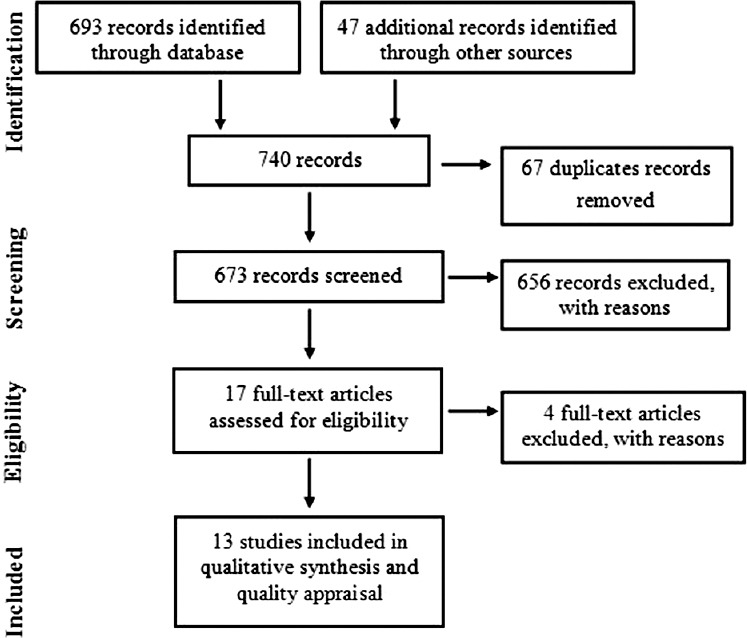

The systematic search of the international literature published from 1941 through 30 November 2014 was performed using keywords and strategy as shown in Appendix 4. After literature searches, we found 693 records. The selection of articles included in the review was performed in a three-phase process [Figure 1] according to PRISMA Guidelines and is shown in the Appendix 3.

Figure 1.

Review process

RESULTS

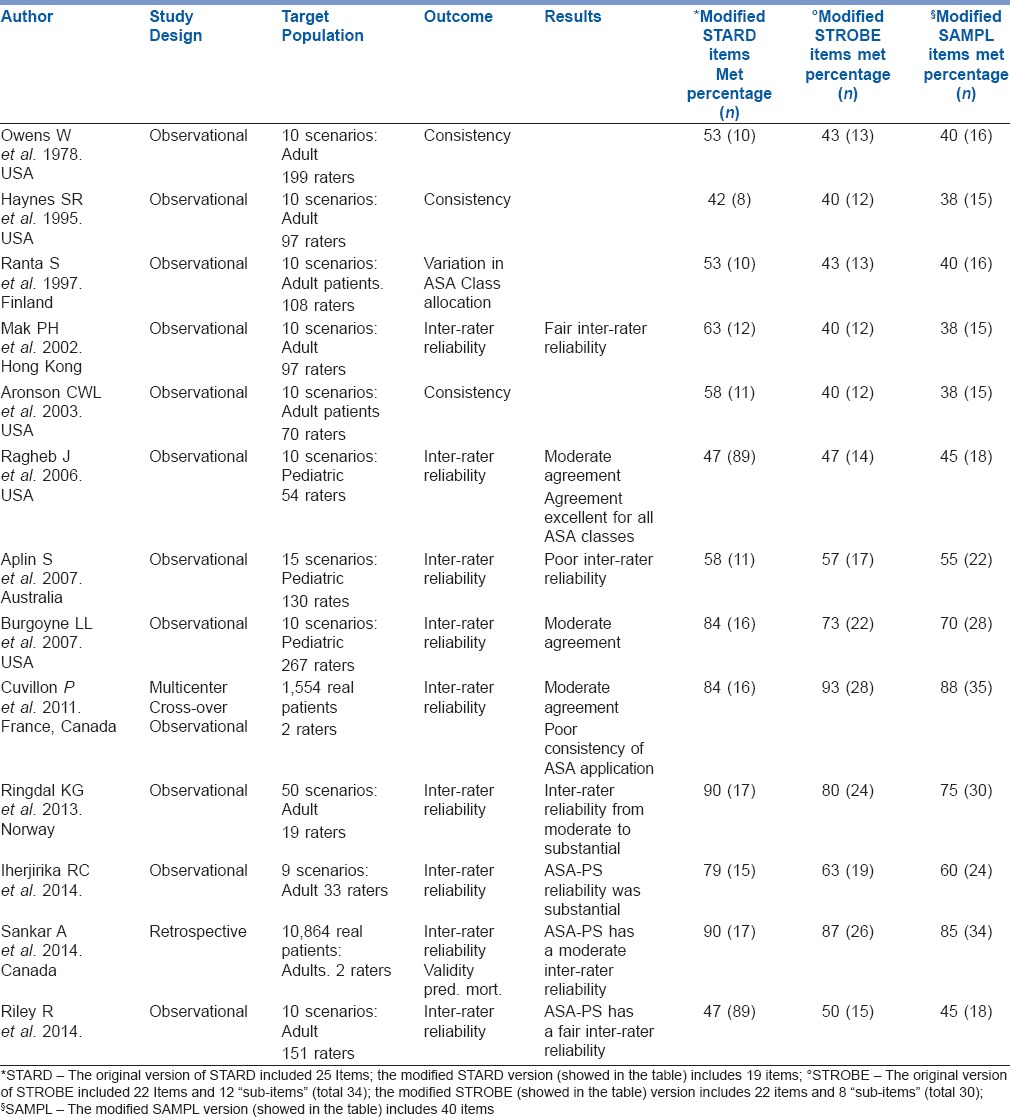

We collected 13 studies for final analysis Table 1. Three of the studies collected were conducted on a paediatric population and only two were done on real patients. The prevalent study design was observational with scenarios. We found only one multi-centric study.

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies selected

The ASA-PS classification reliability was tested among anaesthesiologists and nurses from public and private hospitals.

Eight of the 13 studies tested the inter-rater reliability using the kappa statistic, but the researchers used a very heterogeneous statistical methodology namely, un-weighted, weighted, quadratic kappa. According to the Landis and Koch terminology and classification of kappa value,[8] two of the eight studies found fair inter-rater reliability (k range = 0.21–0.40), three had moderate reliability (k range = 0.47–0.53) and three had good reliability (k range = 0.61–0.82).

All studies conducted on children found a moderate (k range = 0.47–0.50) inter-rater reliability.

Seven studies respected less than 60% of STARD items, and eight respected less than 60% of STROBE and SAMPLE items [Table 1].

None of the studies selected met all 25 items of the STARD, STROBE and SAMPL guidelines.

The studies that met more items of the STARD and STROBE checklists were those of Ringdal et al., Sankar et al. and Cuvillon et al.[5,9,10] All of these studies respected more than 80% of items of both checklists Table 1; however, only Sankar et al. and Cuvillon et al. respected more than 80% of SAMPL items.

DISCUSSION

In this review, the ASA-PS classification shows a wide inter-rater agreement range among all studies included, from fair to very good agreement; however, there was a prevalence of moderate agreement. Seven of the nine studies reported a k inter value higher than 0.4.

Because there are limited data on intra-rater reliability for ASA-PS classification, we think future studies should be planned on these topics. Finally, there are few data on the reliability for patients included in ASA Classes V and VI and limited data on the ASA-PS scale performance with younger children, but it shows moderate agreement with the research available.

We chose to plan a review on the ASA-PS classification reliability because the reliability is a fundamental characteristic of clinical scale.

There is an inter-rater reliability and intra-rater reliability for clinical scores. They are usually analysed using the k statistic, Cohen's kappa.

The wide inter-rater agreement range among all studies included could be explained by the fact that there is a wide discrepancy on the statistical methodology used.

Among the studies collected, we found a prevalence of moderate agreement for the ASA-PS classification; this does not mean that the classification has bad performance, but it could be caused by the bad educational training of the raters.

Furthermore, in our opinion, many previous studies on ASA-PS reliability have several limitations in the methodology: very few studies used a statistical methodology to estimate the right sample size of scenarios or patients; many studies used very few scenarios; finally, almost all of the previous studies used paper scenarios instead of real patients.

The quality of future research on ASA-PS classification should improve: there need to be prospective multi-centre studies based on real patients, planned with a better statistical methodology.

CONCLUSION

The ASA-PS classification seems to have a wide range of inter-rater agreement with a prevalence of moderate value. The administrative staff should be careful to use the ASA-PS classification for administrative billing procedures because of its heterogeneous reliability. Moreover, the physicians should consider the moderate and wide range of agreement of the classification when they use it for general communications. Ideally before using the ASA-PS classification, a test on its reliability among the users should be performed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Appendix 1: Modified STARD guidelines

Appendix 2: Modified STROBE checklist

APPENDIX 3. METHODS

We included all studies on the reliability of ASA conducted on all ages of patients in all languages

To assess the risk of bias of individual studies included, pairs of reviewers worked independently and determined the adequacy of randomization, blinding of patients, health care providers, data collectors, and outcome assessors

According to PRISMA guidelines, to assess the risk of bias that may affect the cumulative evidence of included studies we compared the outcomes in the studies’ protocol (or listed in methods section) with the published reports in the result section

We excluded the duplicate studies and the studies that did not include reliability as an outcome measure

We did not perform any pre-specified analyses for assessing risk of bias across studies because too few included studies

The three reviewers’ yes/no agreement for each study were entered into an Excel 2010 (Microsoft Corporation) spreadsheet, and Fleiss’ kappa for observed agreement was performed. We obtained a Fleiss’ kappa score of k=0,70, equating to a ’substantial” level of agreement between the raters

Review process [Figure 1]

In the first phase, one author, an expert in literature research, conducted a literature search of the following databases: PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Library, Web of Science and Scopus. In the second phase, three researchers independently, blind to the assignment of each other, performed a screening by regarding eligibility criteria of the five lists of articles (title and abstract) selected in phase one. All duplicates were removed. In this way, potentially useful articles were selected with their full text. In the third phase, three researchers independently examined all full-text articles to select the studies that met the inclusion criteria for the systematic review

APPENDIX 4.LITERATURE STRATEGY RESEARCH

PubMed

Search strategy with Mesh 119 records retrieved:

#1 Search “Patients/classification”[Mesh] OR “Health Status”[Mesh] OR “Health Status Indicators” [Mesh:noexp] OR “Health Surveys” [Mesh:noexp] OR “Preoperative Care”[Mesh:noexp] OR “Physical Examination”[Mesh:noexp] OR “Health Status”[Mesh:noexp] AND ((“Anesthesiology”[Mesh] OR “Anesthesia”[Mesh:noexp]) AND (asa OR American society of anesthesiologists OR American society of anaesthesiologists))

Search strategy with Text words 158 records retrieved:

#2 Search (physical OR score* OR scoring OR criteria OR grade* OR classification* OR class OR index OR parameter* OR standard* OR grading) AND (american society anesthesiologists OR american society anaesthesiologists OR ASA) Field: Title

Previouses strategies combined with OR 239 records retrieved:

#3 Search #1 OR #2

EMBASE

Search strategy with EmTree 102 records retrieved:

#1 Search (‘anesthesia’/de OR ‘anesthesist’/de OR ‘anesthesiology’/de AND (‘patient’/de OR ‘health status’/de OR ‘health survey’/exp OR ‘physical examination’/de OR ‘preoperative evaluation’/de OR ‘classification’/de OR ‘functional status’/de OR ‘procedures’/de)) AND (asa OR “American society of anesthesiologists” OR “American society of anaesthesiologists”)

Search strategy with Text words 168 records retrieved:

#2 Search (physical OR score* OR scoring OR criteria OR grade* OR classification* OR class OR index OR parameter* OR standard* OR grading AND (american society anesthesiologists OR american society anaesthesiologists OR ASA)):ti Previouses strategies combined with OR 220 records retrieved:

#3 Search #1 OR #2

Web of Science

Search strategy with Text words 178 records retrieved:

#1 Search Field title: (physical OR score* OR scoring OR criteria OR grade* OR classification* OR class OR index OR parameter* OR standard* OR grading) AND (american society anesthesiologists OR ASA OR american society anaesthesiologists) 178 records

Scopus

Search strategy with Text words 56 records retrieved:

#1 Search Field title: (physical OR score* OR scoring OR criteria OR grade* OR classification* OR class OR index OR parameter* OR standard* OR grading) AND (american society anesthesiologists OR ASA OR american society anaesthesiologists)

Cochrane Library

Search strategy with Text words none records retrieved

#1 Search Field title: american society of anesthesiologists OR ASA OR american society of anaesthesiologists

REFERENCES

- 1.Dripps RD, Lamont A, Eckenhoff JE. The role of anesthesia in surgical mortality. JAMA. 1961;178:261–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.1961.03040420001001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tiret L, Hatton F, Desmonts JM, Vourc’h G. Prediction of outcome of anaesthesia in patients over 40 years: A multifactorial risk index. Stat Med. 1988;7:947–54. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780070906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wolters U, Wolf T, Stützer H, Schröder T. ASA classification and perioperative variables as predictors of postoperative outcome. Br J Anaesth. 1996;77:217–22. doi: 10.1093/bja/77.2.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haynes SR, Lawler PG. An assessment of the consistency of ASA physical status classification allocation. Anaesthesia. 1995;50:195–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1995.tb04554.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sankar A, Johnson SR, Beattie WS, Tait G, Wijeysundera DN. Reliability of the American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status scale in clinical practice. Br J Anaesth. 2014;113:424–32. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeu100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Daabiss M. American Society of Anaesthesiologists physical status classification. Indian J Anaesth. 2011;55:111–5. doi: 10.4103/0019-5049.79879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bossuyt PM, Reitsma JB, Bruns DE, Gatsonis CA, Glasziou PP, Irwig LM, et al. The STARD statement for reporting studies of diagnostic accuracy: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:W1–12. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-1-200301070-00012-w1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33:159–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ringdal KG, Skaga NO, Steen PA, Hestnes M, Laake P, Jones JM, et al. Classification of comorbidity in trauma: the reliability of pre-injury ASA physical status classification. Injury. 2013;44:29–35. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2011.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cuvillon P, Nouvellon E, Marret E, Albaladejo P, Fortier LP, Fabbro-Perray P, et al. American Society of Anesthesiologists’ physical status system: a multicentre Francophone study to analyse reasons for classification disagreement. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2011;28:742–7. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0b013e328348fc9d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]