Abstract

Electronic circular dichroism and circularly polarized luminescence acid-base switching activity is demonstrated in helicene-bipyridine proligand (1a) and in its “rollover” cycloplatinated derivative (2a). While proligand 1a displays a strong bathochromic shift (>160 nm) of the non polarized and circularly luminescence upon protonation, complex 2a displays slightly stronger emission. This striking different behavior between singlet emission in the organic helicene and triplet emission in the organometallic one is rationalized using theory. The very large bathochromic shift of the emission observed upon protonation of azahelicene-bipyridine 1a was rationalized by the decrease of aromaticity (promoting a charge transfer-type transition rather than a π–π* one) along with an increase of the HOMO-LUMO character of the transition and stabilization of the LUMO level upon protonation.

Keywords: helicene; 2,2′-bipyridine; chiroptical switch; CPL; time-dependent density functional theory

Graphical abstract

A [6]Helicene-bipyridine derivative is used as a proligand for “rollover” cycloplatination and for the conception of acid-base chiroptical switches. The protonation triggers the nature of the HOMO-LUMO transition, from a π–π* type to a charge transfer one and significantly modifies the circularly polarized luminescence and electronic circular dichroism spectra of organic and organometallic helicenes

Introduction

The development of chiral molecules displaying large chiroptical properties may lead to novel multifunctional molecular materials.[1] In this area, helicenes show great potential. Due to their π-conjugated helical backbone, they combine high optical activity with other properties such as intense emission.[2,3] Recently, organometallic helicenes in which a transition metal (Pt, Ir, Os) is included within the helical π-framework have emerged as promising candidates for opto-electronic applications and as good chiral emitters.[3e,4] Devices displaying circularly polarized luminescence (CPL) are of great interest since CPL activity may be a powerful method to address encoded information (cryptography) or for 3D displays.[5a] More generally, systems that possess switchable CPL functionality may lead to new possibilities for molecular information processing and storage.[5b]

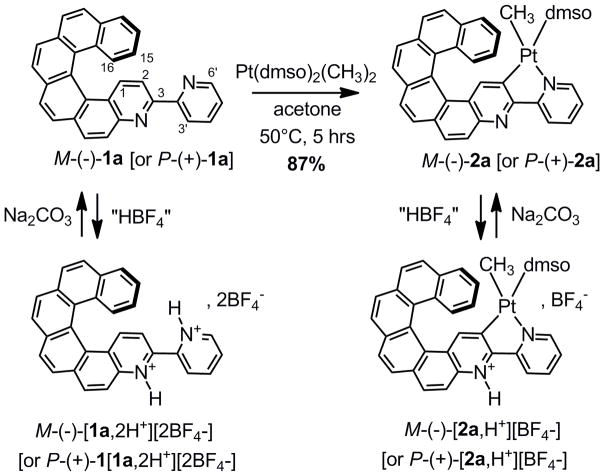

In this paper, we describe the regioselective rollover cycloplatination of a helicene-2,2′-bipyridine proligand,[6] namely 3-(2-pyridyl)-4-aza[6]helicene (1a), Scheme 1. The new organic and organometallic helicene derivatives act as unprecedented multifunctional pH-switchable chemical systems due to the reversible tuning of their optical and chiroptical properties: optical rotation (OR), electronic circular dichroism (ECD), non-polarized luminescence and CPL. The different behaviors of these ECD and CPL switches are interpreted based on results from first-principles calculations.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of enantiopure rollover cycloplatinated Pt(CH3)(dmso)(bipy - H) complexes M-(−)- and P-(+)-2a from enantiopure helicene-bipy proligands M-(−)- and P-(+)-1a. Reversible protonation/deprotonation in acetone.

Results and Discussion

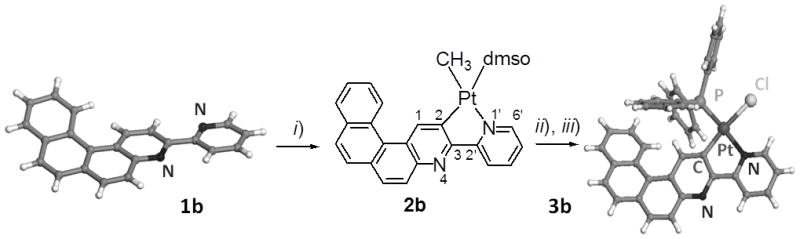

The synthesis of racemic 3-(2-pyridyl)-4-aza[6]helicene 1a was performed in two steps from 2,2′-bipyridine-6-carboxaldehyde, by a Wittig reaction with 2-methylbenzophenanthrene phosphonium bromide[7] followed by a photocyclization reaction (83% overall yield),[2] and enantiopure M- and P-1a (ee’s >99%) were subsequently obtained by HPLC over a Chiralpak IC stationary phase (see Supporting Information, SI). 3-(2-Pyridyl)-4-aza[6]helicene (1a) has been fully characterized and displays classical spectrocopic features of helicenes (see Experimental Part). The X-ray crystallographic structure of a smaller model molecule, i.e. 3-(2-pyridyl)-4-aza[4]helicene 1b displayed in Scheme 2 shows i) the helical aza[4]helicene part (helicity 25.13°), ii) the grafted 2-pyridyl group which is coplanar with the helicene part (dihedral angles of −1.17 and 5.35 between the two pyridyl rings) and iii) the two nitrogen atoms in mutually trans positions.

Scheme 2.

Reactivity of rollover cycloplatinated Pt(CH3)(dmso)(bipy - H) complex 2b. i) Pt(dmso)2(CH3)2, acetone, 50°C, 5 hrs, 89%. ii) HCl (0.1N), acetone, dmso, 8 hrs, 70%; iii) PPh3, CH2Cl2, 2 hrs, 98%. X-ray crystallographic structures of proligand 1b and of cycloplatinated complex 3b.

Examples of molecular materials based on chiral bipy ligands and their complexes are still rare.[8] Apart from their common 1,4-N,N′ chelating behavior, 2,2′-bipyridines can act as 1,4-C,N chelates through the direct metal-mediated C-H bond activation at the 3-position of the 2-pyridyl ring and undergo the so-called “rollover” cyclometalation.[9,10] The N1′-C2 rollover cycloplatination of M- and P-1a to enantiopure complexes M- and P-2a (Scheme 1) was performed by reacting respectively M- and P-1a with electron-rich [Pt(dmso)2(CH3)2] precursor at 50°C in acetone for 5 hours (87% yield). The formation, regioselectivity, and stereochemistry of the neutral square-planar Pt(II) complex 2a was established by multinuclear NMR spectroscopy. For example, the 1H NMR spectrum at 400 MHz revealed the disappearance of the H2 signal, the strong deshielding (1 ppm) of proton H6′ (9.5 ppm) with satellites due to a 3J(195Pt, 1H) coupling constant of 20 Hz, and the H1 proton appearing at 8.1 ppm with a 3J(195Pt, 1H) of 63 Hz, all confirming the C2–Pt and N1′–Pt bond formation. These results show that the CH activation process proceeded regioselectively at the C2 position only.[10] Due to trans effects, the cycloplatination is also stereoselective, with the dmso S-ligand placed trans to the C2 carbon. Note that the Pt–CH3 signal appears at −0.34 ppm (2J(195Pt, 1H) = 83 Hz) while the two dmso methyl groups are diastereotopic with the 3J(195Pt, 1H) coupling constant (18 Hz).[10] Using the same conditions as for 2a, the regio- and stereoselective N1′-C2 rollover cycloplatination of model proligand 1b gave complex 2b with 89% yield (Scheme 2). This compound displayed the same spectroscopic features as 2a. Furthermore, reaction of complex 2b with HCl (0.1N) followed by reaction with triphenylphosphine, yielded complex 3b in which the PPh3 ligand is trans to the N1′ nitrogen and a chlorine is placed trans to the C2 carbon.[10d] The X-ray crystallographic structure of 3b finally ascertained the presence of the platinacycle (Scheme 2).[11] Noteworthy, very low dihedral angles (2–3°) between the two pyridyl rings ensure that the π-conjugation extends across the whole molecule. The N atom of the helical moiety remains free for protonation (vide infra).[10e]

Azahelicenes are known to exhibit high proton affinities[12] and some of them behave as proton sponges,[12b] while, according to Zucca et al., in the protonated rollover cycloplatinated complex the ligand may be considered as an “abnormal remote heterocyclic chelated carbene or simply as mesoionic cyclometalated ligand”.[10e] Therefore, in our quest for original new organometallic helicene-based chiroptical switches,[13a,14] we investigated the acid-base reactivity and the use of organic helicene 1a and cycloplatinated helicene 2a as potential multifunctional pH-triggered UV-vis, OR, ECD and/or CPL switches. The acid [H2O.HBF4]2[18C6] (“HBF4”)[10d,15] in acetone or CH2Cl2 was used to protonate either proligand 1a or rollover complex 2a into respectively M-(−) and P-(+) enantiopure forms of [1a,2H+][2BF4−] and [2a,H+][BF4−] while treatment with Na2CO3 or NEt3 enabled the recovery of the neutral forms (Scheme 1). The unusual electronic properties of these systems were rationalized with the help of density functional theory (DFT) and time-dependent DFT, using the BHLYP functional (50% exact exchange) and a split-valence basis with polarization functions for non-hydrogen atoms (SV(P)) for most calculations. Computational details, detailed analyses, and additional results not discussed herein, are provided in the Supplementary Information (SI).

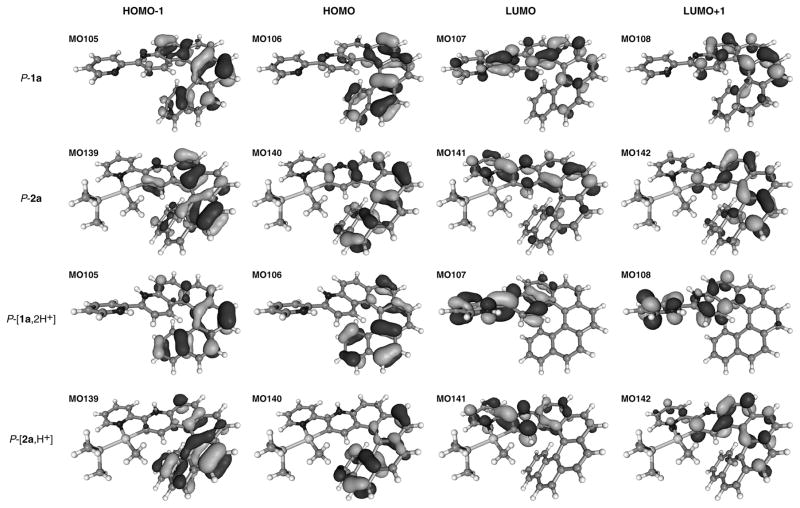

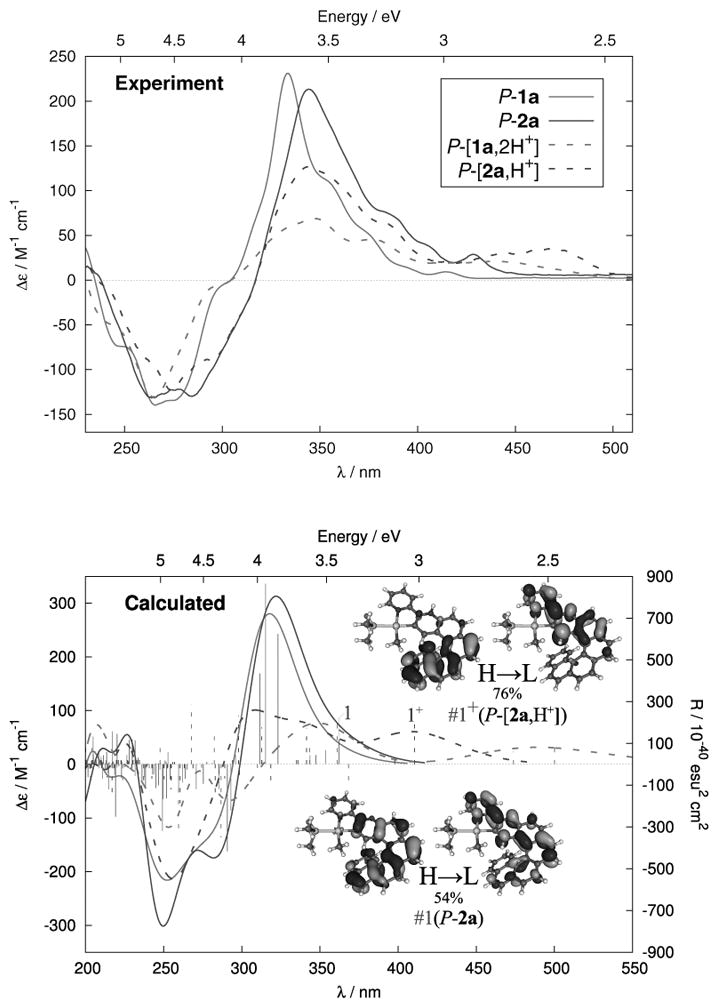

The UV-vis absorption spectrum of 1a (SI) is typical of an extended π-conjugated system, with a strong band (ε > 50×103 M−1 cm−1) at 266 nm, and several structured broad bands around 330, 350 and 393 nm. Proligand P-1a displays a strong, structured, negative CD band at c.a. 264 nm (Δε = −183 M−1cm−1) and strong positive bands at 333, 352 and 375 nm (Δε = +235, +107, +42 M−1cm−1), Figure 1. These values are stronger than for unsubstituted 4-aza[6]helicene,[13] owing to the extended π-conjugation and partial charge transfer (CT) character of the lowest-energy π–π* excitations (dominantly from the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO, H, Figure 3) to the lowest unoccupied MO (LUMO,L). A high molar rotation is observed for 1a (P-1a: [ϕ]D = +12000 ∘ cm2 dmol−1 (±5%), in CH2Cl2, 6.5×10−5 M, calc. BHLYP +14176).

Figure 1.

Measured (up, CH2Cl2, ~10−5 M) and calculated (bottom) BHLYP CD spectra of proligand P-1a (plain grey), P-[1a,2H+][2BF4−] (dotted grey), and of complexes P-2a (plain black) P-[2a,H+][BF4−] (dotted black). Frontier MOs (0.03 au) of P-2a and P-[2a,H+]. For assignments of the spectra see the SI.

Figure 3.

Isosurfaces (0.04 au) of selected MOs of 1a, [1a,2H+] and 2a, [2a,H+].

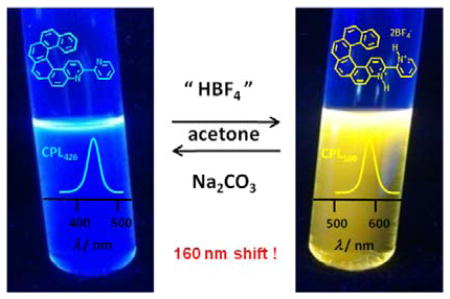

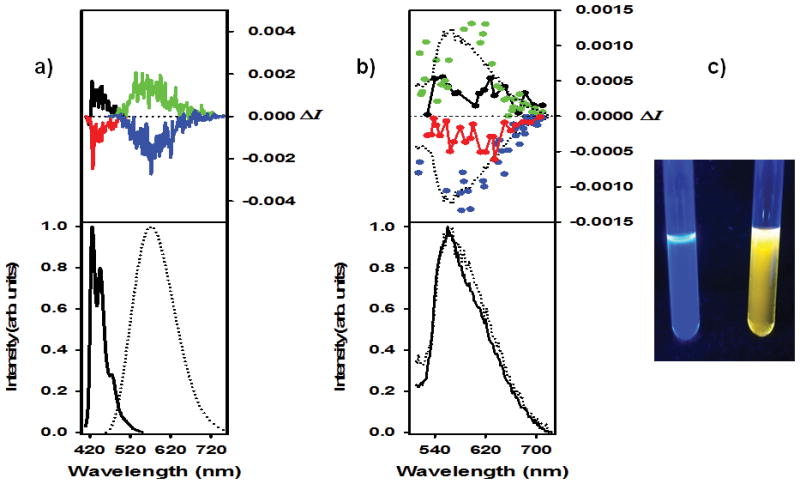

Proligand 1a exhibits emission behavior typical of π-conjugated polyaromatic hydrocarbons and previously described helicenes.[2,3,13c] In CH2Cl2 solution at r.t., 1a displays classical structured blue fluorescence with a maximum (λ0-0) at 421 nm and a vibronic progression of 1400 cm−1 (quantum yield Φ 8.4% and fluorescence lifetime τ 6.6 ns, see Figure 2 and Figure S16; emission data for all compounds are summarized in Tables 1 and S3). A particularly interesting feature of fluorescent derivatives P-(+) and M-(−)-1a is that they exhibit CPL (Figures 2a)[3] with mirror-imaged spectra and respective luminescence dissymmetry ratios glum of +3.4×10−3 and −3×10−3 around the emission maximum (426 nm). These glum values are comparable to other fluorescent organic azahelicene derivatives.[3]

Figure 2.

a) CPL (top) and total emission (bottom) of fluorescent 3-(2-pyridyl)-4-aza[6]helicene P-1a (black), and M-1a (red) enantiomers to respectively P-[1a,2H+][2BF4−] (green) and M-[1a,2H+][2BF4−] (blue), at 426 nm and at 590 nm respectively, in CH2Cl2 at r.t.; b) CPL (top) and total emission (bottom) of phosphorescent complex P-2a (black), and M-2a (red) enantiomers to respectively P-[2a,H+][BF4−] (green) and M-[2a,H+][BF4−] (blue), at 547 nm and at 555 nm respectively, in acetone at r.t. c) visual acid-base fluorescence switching of 1a.

Table 1.

Experimental and calculated emission data of ligand species 1a and [1a,2H+] and of cycloplatinated complexes 2a and [2a,H+]. Energies, in eV. Oscillator strength/rotatory strength values in 10−40 cgs are listed in parentheses.

| P-1a |

P-[1a,2H+]-# a

|

P-2a | P-[2a,H+] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | ||||

| Expt. b | |||||

| 298 K | 2.94, 2.79, 2.62 | 2.10 | 2.27, 2.12 | 2.23, 2.10 | |

| 77 K | F: 2.97, 2.81, 2.63 | F: 3.13, 2.98, 2.81, 2.63 g | 2.31, 2.13, 1.95 | 2.29, 2.10, 1.94g | |

| P: 2.33, 2.15, 1.99 | P: 2.34, 2.15, 2.00 g | ||||

|

| |||||

| Calc. BHLYP/SV(P) c | |||||

| S1{TDDFT} d | 2.99 (0.4642/427.88) | 1.86 (0.1631/174.24) | 1.87 (0.1741/194.33) | 2.94 (0.5507/459.99) | 2.66 (0.3444/268.69) |

| T1{TDDFT} e | 2.18 | 1.49 | 1.50 | 2.16 | 2.08 |

| T1{DFT} f | 2.08 | 1.60 | 1.61 | 2.06 | 2.08 |

Conformer #1: dihedral angle N-C-C′-N′ of −150.0°, −170.5°, −175.7°, and −170.9° for S0 ground state, S1 excited state, T1 excited state, and triplet configuration, respectively. Conformer #2: dihedral angle N-C-C′-N′ of 151.0°, 171.5°, 172.2°, and 168.7° for S0 ground state, S1 excited state, T1 excited state, and triplet configuration, respectively.

298 K: DCM/acetone data for ligand/cycloplatinated species, 77 K: recorded in diethyl ether/isopentane/ethanol. F = fluorescence. P = phosphorescence.

DCM/acetone calculations for ligand/cycloplatinated species.

TDDFT S1-S0 energy difference at TDDFT BHLYP/SV(P) optimized S1 geometry. In parentheses oscillator strength/rotatory strength values in 10−40 cgs are listed. To convert to integrated CPL intensity, in cgs units of power output per molecule, the following expression can be used: ΔI = 1.60041320 · 1037 · Rcgs · Ecgs4.

TDDFT T1-S0 energy difference at TDDFT BHLYP/SV(P) optimized T1 geometry.

TDDFT T1-S0 energy difference at DFT BP/SV(P) optimized triplet configuration.

At 77K, the equilibrium B+H+ ⇄ BH+ is frozen.

The UV-vis spectrum of 2a shows a similar shape as 1a and has a similar helicene-centered assignment. The CD spectrum of P-2a (Figure 1) displays two strong negative bands at 264 and 287 nm (Δε = −131, −130 M−1cm−1) and several strong to moderate positive bands at 343, 386, 403, 429 nm (Δε= 212, 73, 41, 23 M−1cm−1) that are ~10 nm red-shifted compared to P-1a with the lower-energy π–π* excitations exhibiting significant intra-ligand charge transfer (ILCT) character. The MOs involved in the lower-energy excitations do not indicate a strong involvement of Pt 5d orbitals. The metal’s dominant role is to render the structure of the chromophore rigid and to promotes intersystem crossing (vide infra). A high molar rotation value is observed for 2a (P-2a: [ϕ]D = +18730 (±5%), in CH2Cl2, 7×10−5 M, calc. BHLYP +19345). In contrast to 1a, the rollover cycloplatinated helicene 2a displays red phosphorescence at r.t. (λmax = 547 nm, Φ = 0.3%, τ = 8.2 μs), with no fluorescence band (Figures 2 and S18, Tables 1 and S3). Such behaviour is expected for cycloplatinated complexes due to strong spin-orbit coupling. The low quantum yield and estimated radiative rate constant of around 200 s−1 suggest that the phosphorescence is relatively inefficient, reflecting the decreasing contribution of the metal to the excited state, in agreement with the calculations. Phosphorescent derivatives P-(+) and M-(−)-2a are CPL active (Figure 2b),[3] and display mirror-imaged CPL spectra with glum values of +1×10−3 and −1.1×10−3 around the emission maximum (547 nm). These values are lower than those of previously published platina[6]helicenes (glum~10−2),[3e] because the Pt center is less involved in the helical π-core of the molecule, as indicated by the calculations.[5c-f]

Upon protonation by an excess of “HBF4” in acetone, P-[2a,H+][BF4−] and M-[2a,H+][BF4−] were obtained quantitatively within two hours (Scheme 1). Their 1H NMR spectra displayed overall downfield shifted signals and the appearance of the NH+ signal at 13.5 ppm (SI). Interestingly, the UV-vis spectra of protonated complexes P-[2a,H+][BF4−] and M-[2a,H+][BF4−] were significantly different from the non-protonated P-and M-2a, with a stronger broad band at longer wavelengths (380–510 nm, λmax = 467 nm, ε = 8260 M−1cm−1, Figure S9) than the corresponding neutral species (380–460 nm, λmax = 429 nm, ε = 5800 M−1cm−1). Similarly, ECD spectra were substantially modified, with ~10 nm red-shifted negative bands at 273 and 293 nm (Δε = −116, −86 M−1cm−1), a less intense positive band at 345 nm (Δε = +135 M−1cm−1), and strong band at 465 nm (Δε = +34 M−1cm−1) for the P-[2a,H+][BF4−] enantiomer (Figure 1). Note that several isosbestic points are appearing in the UV-vis and CD spectra upon successive addition of 0.1 eq of “HBF4” (see Figures S9 and S11). The protonation of enantiopure M- and P-proligands 1a was also performed under the same conditions, i.e. by reacting with a slight excess of “HBF4” in either acetone or CH2Cl2 thus yielding M- and P-[1a,2H+][2BF4−] quantitatively. The 1H NMR spectrum displayes downfield shifts of all the signals, i.e. aza[6]helicene and pyridyl moiety (for example Δδ = 0.6 and 0.2 ppm for H6′ and H15 respectively), consistent with the presence of two NH+.

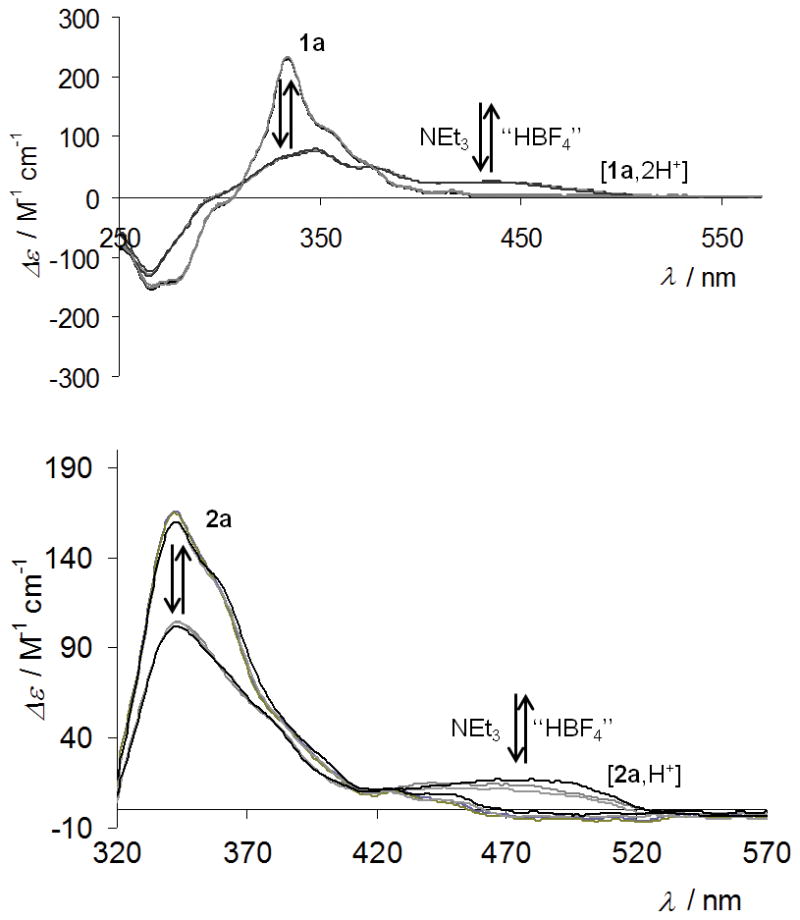

Compared to 1a, the UV-vis spectrum of protonated [1a,2H+][2BF4−] displays a new low-energy band of moderate intensity (ε = 3500 M−1cm−1, Figure S8) between 430 and 530 nm and is slightly different in the 250–350 nm region. The ECD-active bands in the 250–350 nm region are significantly lowered (for example Δε = +44 vs. 111 M−1cm−1 at 348 nm for P-[1a,2H+][2BF4−] and P-1a, respectively) while a new ECD-active band has appeared around 430–530 nm (Δε = +14 M−1cm−1 at 430 nm), Figure 1.[12a] The UV-vis and CD spectra are accompanied with the appearance of several isosbestic points upon successive addition of 0.1 eq of “HBF4” (see Figures S8 and S10). However, it was not possible to identify a mono-protonated intermediate, which suggests that both pyridyl cycles undergo protonation simultaneously. Intramolecular proton transfer between the two pyridyls may also occur.[12d] Note that the charged protonated systems are very challenging for the calculations due to solvent- [12a] and counter-ion – effects (see SI). However, the most important trends upon protonation observed experimentally are correctly reproduced by the calculations, in particular the appearance of low-energy absorption and ECD bands. Protonation has a strong effect on the delocalization of the extended π-systems of both 1a and 2a. For instance, the new lowest-energy ECD band in [2a,H+] is assigned as dominantly H-L π–π* similar to 2a, but unlike 2a the transition is now a much more clear-cut CT case from the helicene moiety to the other side of the ligand. The frontier MOs of 2a are conjugated through the pyridyl, but upon protonation the orbitals become spatially separated as demonstrated in Figure 1. Nucleus-independent chemical shift calculations for a model system as described in the SI suggest that the pyridyl becomes less aromatic upon protonation. Therefore, we attribute the increase in CT character to a loss of conjugation of the frontier orbitals caused by a reduction of aromatic character in the pyridyl moiety. The overall contribution of the H-L pair to the transition increases upon protonation, which further amplifies the increase of CT character (Table 2). Similar changes upon protonation can be observed for 1a. The S0–S1 absorption becomes even more purely of H-L character here. Inspection of the orbital energies (Table S7) shows that protonation has a strongly stabilizing effect on the LUMO of 2a and even more so on 1a, and to a much lesser extent on the HOMO, reducing the H-L gap. The frontier MOs calculated for both 1a and 2a appear very similar (Figure 3). All exhibit large values of the LUMOs around the pendant pyridyl nitrogen while the HOMOs have nodes at this position. The same was found for MOs at the S1 and T1 optimized geometries (Figure S33, vide infra). Therefore, the appearance of the low-energy ECD bands upon protonation of both systems can be rationalized mainly by its impact on the LUMO and simultaneously the S0–S1 transition becoming more dominant in H-L character. The protonation has also an effect on the optical rotation. Molar rotations appeared lower for bis-protonated P-[1a,2H+][2BF4−] ([ϕ]D = +10000 (±5%), in CH2Cl2, 1.7×10−4 M) than for P-1a, and decreased even more for the protonated complex P-[2a,H+][BF4−] ([ϕ]D = +9145 (±5%), CH2Cl2, 1.5×10−5 M). Calculations (Table S4) indicate that the counterion(s) may play a role in these strong reductions. Furthermore, as depicted in Figure 4, successive addition of “HBF4” and NEt3 in either acetone or CH2Cl2 to 3-(2-pyridyl)-4-aza[6]helicene (1a) and its cycloplatinated complex 2a enabled reversible and repeatable modification of the OR and ECD values, and hence the system constitutes a pH-triggered chiroptical switch.

Table 2.

HOMO-to-LUMO character (in %) of S0-S1 absorption along with S1-S0 and T1-S0 emission transitions for ligand species 1a and [1a,2H+] and of cycloplatinated complexes 2a and [2a,H+]. BHLYP/SV(P) calculations with continuum solvent model for DCM.

| S0-S1 | S1-S0 | T1-S0 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| P-1a | 33.0 | 93.7 | 72.3 |

| P-[1a,2H+] a | 91.7 | 96.5 | 76.0 |

| 96.4 | 75.9 | ||

| P-2a | 53.8 | 92.3 | 68.9 |

| P-[2a,H+] | 75.5 | 90.1 | 61.6 |

Results for two conformers are listed in the case of S1 and T1 excited states of P-[1a,2H+], compare Table 1 (conformer #1 and #2).

Figure 4.

Reversibility of the acid/base switching process by ECD spectroscopy for ligand 1a (top) and complex 2a (bottom) after several successive stoechiomeric addings of acid and base.

The luminescence λmax of 2a undergoes much less of a change upon protonation than its ECD or the ECD and CPL of 1a (Figure 2b). The calculated T1–S0 emission energies are likewise very similar for 2a and its protonated form (Table 1) and in good agreement with experiment. Only for this transition we found a decrease of H-L character upon protonation which renders the reduction of the H-L orbital energy gap due to protonation less important (Table 1), leading to a decrease of the calculated emission energy by only 0.1 eV. The estimated radiative rate constant remains around 200 s−1, but the phosphorescence quantum yield is larger and the lifetime longer (λmax = 555, 590 nm, Φ = 2.7%, τ = 120 μs), suggesting that non-radiative decay pathways are impeded in the protonated form. The CPL activity is doubled in the protonated species (glum= +1.8×10−3 and −2.2×10−3 for P- and M-[2a,H+][BF4−] respectively, Figure 2b).

Helicene 1a shows a more striking change in its luminescence upon protonation. The emission is strongly bathochromically shifted, from λmax = 426 nm in 1a to 590 nm in [1a,2H+][2BF4−] (a shift of −0.8 eV, in CH2Cl2 solution at r.t., Figure 2a, Table S3). The calculations also produce a large bathochromic shift (−1.1 eV) for the S1-S0 emission upon protonation of 1a, Table S8, mirroring a similar shift in the calculated S0-S1 excitation energies. The S1-S0 transitions afford slightly increasing contributions from the H-L pair upon protonation, meaning that the strong stabilization of the LUMO is more clearly reflected in the emission energy of [1a,2H+] than it is in the T1-S0 emission of [2a,H+]. The emission remains quite intense with a similar quantum yield and lifetime (Φ = 8.2%, τ = 5.4 ns, Table S3). Similar glum values as for P- and M-1a were obtained for protonated samples (P-[1a,2H+][BF4−]: +3.2×10−3 and M-[1a,2H+][BF4−]: −2.5×10−3 at 590 nm). Overall, this significant λem change from the blue to yellow fluorescence (Figure 2c) accompanied by CPL enables us to consider this system as a reversible CPL-active pH-triggered on-off chiroptical switch at either 426 or 590 nm by successive addition of either “HBF4” or Na2CO3/NEt3 to acetone or CH2Cl2 solution of 3-(2-pyridyl)-4-aza[6]helicene 1a. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first example of a helicene-based multi-responsive acid-base chiroptical switch.[14]

Conclusions

In conclusion, we have performed unprecedented pH-triggered switching of OR, CD and CPL activity using organic and organometallic helicene derivatives. The very large bathochromic shift of the emission observed upon protonation of azahelicene-bipy was theoretically rationalized by the decrease of aromaticity and stabilization of the LUMO level. Overall, this example illustrates the use of a chiral bipyridine ligand exhibiting “multiple personalities”[16] since it reveals original chiroptical and photophysical properties as well as N,C chelate behavior and it opens up new routes to chiral materials.

Experimental Section

Most experiments were performed using standard Schlenk techniques. Solvents were freshly distilled under argon from sodium/benzophenone (THF) or from phosphorus pentoxide (CH2Cl2). Starting materials were purchased from Aldrich. Column chromatography purifications were performed in air over silica gel (Merck Geduran 60, 0.063–0.200 mm). Irradiation reactions were conducted using a Heraeus TQ 700 mercury vapor lamp. NMR spectra 1H, 13C and 31P were recorded at room temperature on a Bruker AV400 spectrometer equipped with a QNP switchable probe 13C-31P-19F-1H and operating at proton resonance frequency of 400 MHz. Chemical shifts are reported in parts per million (ppm) relative to Me4Si as external standard. Assignment of proton atoms is based on COSY experiment.31P NMR downfield chemical shifts are expressed with a positive sign, in ppm, relative to external 85% H3PO4. All spectra were obtained using deuterated dichloromethane or chloroform as solvents. The terms s, d, t, q, m indicate respectively singlet, doublet, triplet, quartet, multiplet; b is for broad and, dd is doublet of doublets, dt doublet of triplets, td triplet of doublets. Assignment of proton atoms is based on COSY, HMBC, HMQC experiments. Carbon atoms were assigned based on DEPT-135 experiments. Elemental analyses were performed by the CRMPO, University of Rennes 1. Specific rotations (in deg cm2g−1) were measured in a 1 dm thermostated quartz cell on a Perkin Elmer-341 polarimeter. Circular dichroism (in M−1cm−1) was measured on a Jasco J-815 Circular Dichroism Spectrometer (IFR140 facility - Biosit platform - Université de Rennes 1). UV/vis spectroscopy was conducted on a Varian Cary 5000 spectrometer. 2,2′-Bipyridine-6-carbaldehyde,[17,18] (benzo[c]phenanthren-3-ylmethyl)-triphenylphosphonium bromide[7] and cis-(dmso)2PtMe2[19] were prepared according to literature procedures.

Racemic 3-(2-pyridyl)-4-aza[6]helicene (±)-1a

A solution of (benzo[c]phenanthren-3-ylmethyl)triphenylphosphonium bromide[7] (1.465 g, 2.5 mmol) in 40 ml of anhydrous THF was placed in a Schlenk tube under argon and cooled to −78 °C for 5 minutes. To the stirred suspension n-BuLi (2.5 solution in hexanes, 1 ml, 26 mmol) was added dropwise. The reaction mixture turned deep red then warmed to room temperature slowly. After 45 minutes, the reaction mixture was cooled again to −78 °C, then 2,2′-bipyridine-6-carbaldehyde[17,18] (440 mg, 2.39 mmol) was added in one portion; the reaction mixture was warmed to room temperature and the color turned yellow white with stirring for 3 hours. The reaction mixture was filtered over celite and concentrated under vacuum, and the crude oily product was purified by column chromatography (silica gel, heptane/ethyl acetate 7:3) to give the olefine (cis and trans mixture) as a yellow solid (890 mg, 92%). 1H NMR (300 MHz, CD2Cl2): δ 9.26 (1H, s), 9.20 (1H, d, J = 8.5 Hz), 9.17 (0.45H, s), 8.75 (1H, d, J = 3.6 Hz), 8.72 (0.5H, s), 8.65 (1.4H, d, J = 7.8 Hz), 8.33 (1.4H, t, J = 7.4 Hz), 8.15–7.73 (14.5H, m), 7.68 (2H, t, J = 7.8 Hz), 7.53 (1H, dd, J = 14.4, 7.3 Hz), 7.48–7.31 (4H, m), 7.28 (0.3H, s), 7.26–7.19 (0.4H, m), 7.16 (0.4H, d, J = 12.3 Hz), 6.93 (0.4H, d, J = 12.2 Hz). Elemental analysis, calcd. (%) for C30H20N2: C, 88.21; H, 4.93; N, 6.86; found C 87.98, H 4.85, N 6.80.

The mixture of cis and trans olefin 6-(2-(benzo[c]phenanthren-2-yl)vinyl)-2,2′-bipyridine (100 mg) in 1 L toluene/THF (9:1) was irradiated for 5 hrs in the presence of catalytic amount of iodine using a 700W mercury vapor lamp. Then the solvent was stripped off and the crude product was purified over silica gel (heptane/ethyl acetate 8:2) to give (±)-1a as a yellow solid (90 mg, 90%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD2Cl2): δ 8.56 (1 H, m, H3′), 8.49 – 8.53 (1H, m, H6′), 8.14 (2 H, s), 7.94 – 8.03 (4 H, m), 7.90 (2H, s), 7.86 (1H, d, J = 8.9 Hz), 7.80 (1H, d, J = 8 Hz, H13), 7.79–7.74 (m, 1H, H4′), 7.65 (1 H, d, J = 8.7 Hz), 7.57 (d, J = 9 Hz, 1 H, H16), 7.22 (1 H, ddd, J = 7.3, 4.8, 1.1 Hz, H5′), 7.15 (1 H, ddd, J = 8, 6.9, 1.1 Hz, H14), 6.64 (1 H, ddd, J = 8.5, 6.9, 1.4 Hz, 1 H, H15). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CD2Cl2): δ 156.33 (C), 154.86 (C), 149.45 (CH), 147.54 (C), 137.13 (CH), 135.94 (CH), 133.69 (C), 132.59 (C), 132.07 (C), 131.74 (C), 130.63 (CH), 129.88 (C), 129.81 (CH), 128.61 (CH), 128.31 (CH), 128.12 (CH), 128.04 (CH), 128.03 (CH), 127.97 (C), 127.60 (CH), 127.42 (CH), 126.54 (CH), 126.15 (CH), 125.77 (C), 125.58 (CH), 124.39 (C), 124.27 (CH), 121.54 (CH), 116.94 (CH). Elemental analysis, calcd. (%) for C30H18N2: C, 88.64; H, 4.46; N, 6.89; found C 88.55, H 4.39, N 6.83.

3-Pyridinium-4-azonia[6]helicene [1a,2H+][2BF4−]

Compound 1a (10 mg, 0.024 mmol) was dissolved in 4 ml CH2Cl2 then [H2O.HBF4]2[18C6][15] (0.027 mmol, 13 mg) was added and the reaction mixture was stirred for 2 hours at room temperature. CH2Cl2 was evaporated to small volume, and then ether was added to observe yellow precipitate that was filtrated and washed with ether to remove the excess acid. Finally, the precipitate was dried under vacuum to obtain [1a,2H+][2BF4−] as yellow-orange powder (12.6 mg, 90%). 1H NMR (300 MHz, CD2Cl2): δ 9.08 – 9.15 (1 H, m, H6′), 8.47 – 8.59 (2 H, AB, J = 9.1 Hz), 8.34 – 8.43 (2 H, m), 8.27 (2 H, d, J = 8.3 Hz), 8.12 – 8.19 (3 H, m), 8.02 – 8.09 (2 H, m), 7.94 (1 H, dd, J = 8.10, 0.8 Hz, H13), 7.88 (1 H, ddd, J = 7.6, 5.4, 1.1 Hz, H5′), 7.65 (1 H, 6, J = 8.6 Hz, H16), 7.47 (1 H, d, J = 9.0 Hz), 7.29 (1 H, ddd, J = 8, 6.9, 1.1 Hz, H14), 6.83 (1 H, ddd, J = 8.5, 7.0, 1.4 Hz, H15). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CD2Cl2): δ 147.07 (C), 146.53 (CH), 144.34 (CH), 144.25 (C), 140.42 (CH), 135.39 (CH), 134.28 (C) 132.78 (C), 132.68 (C), 132.62 (C), 130.30 (1 CH), 129.19 (CH), 129.18 (CH), 129.06 (C), 128.68 (CH), 127.99 (CH), 127.70 (CH), 127.68 (CH), 127.56 (CH), 127.40 (C), 127.26 (C), 126.80 (C), 126.66 (CH), 126.61 (CH), 126.30 (CH), 125.81 (CH), 124.10 (C), 123.55 (CH), 116.10 (CH). One C is missing. Elemental analysis, calcd. (%) for C30H20B2F8N2: C, 61.90; H, 3.46; N, 4.81; found C 62.63, H 3.56, N 4.57.

3-Pyridyl-4-aza[4]helicene 1b

A solution of 2-methylnaphtyltriphenylphosphonium bromide (433 mg, 0.89 mmol) in 15 ml of anhydrous THF was placed in a Schlenk tube under argon and cooled to −78 °C. To the stirred suspension n-BuLi (1.6N solution in hexanes, 0.58 ml, 0.93 mmol) was added dropwise. The reaction mixture turned deep red then warmed to room temperature slowly. After 45 minutes, the reaction mixture was cooled again to −78 °C. Then 2,2′-bipyridine-6-carbaldehyde[17,18] (157 mg, 0.85 mmol) was added in one portion; the reaction mixture was warmed to room temperature and the color turned yellow white with stirring overnight. The reaction mixture was filtered over celite and concentrated under vacuum, and the crude oily product was purified by column chromatography (silica gel, heptane/ethyl acetate 8:2) to give the olefin (cis and trans mixture) as a yellow solid (215 mg, 82%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.63 (1 H, d, J = 4.0 Hz), 8.51 – 8.58 (2 H, m), 8.22 (1 H, d, J = 8.0 Hz), 8.14 (1 H, d, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.85 – 7.95 (3 H, m), 7.70 – 7.84 (7 H, m), 7.59 – 7.69 (2 H, m), 7.53 (1 H, t, J = 7.9 Hz), 7.34 – 7.48 (7 H, m), 7.23 – 7.34 (2 H, m), 7.11 – 7.17 (2 H, m), 6.96 (1 H, d, J = 12.3 Hz), 6.76 (1 H, d, J = 12.3 Hz). Elemental analysis, calcd. (%) for C22H16N2: C, 85.69; H, 5.23; N, 9.08; found C 84.50, H 5.19, N 9.03.

The mixture of cis and trans olefin 6-(2-(benzo[c]phenanthren-2-yl)vinyl)-2,2′-bipyridine (500 mg) in 700 mL toluene/THF (9:1) was irradiated for 15 hrs in the presence of catalytic amount of iodine using a 150W mercury vapor lamp. Then the solvent was stripped off and the crude product was purified over silica gel (heptane/ethyl acetate; 9:1) to give 1b as yellow solid (370 mg, 75%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 9.41 (1 H, d, J = 9 Hz, H1), 8.98 (1 H, d, J = 8.1 Hz, H12), 8.59 – 8.68 (3 H, m, H6′, H2′, H2), 8.00 – 8.12 (2H, AB, J = 8.7 Hz, H5, H6) 7.98 (1 H, dd, J = 7.9, 1.7 Hz, H12), 7.78 – 7.89 (2 H, AB, J = 8.5 Hz, H7,8), 7.81 (1 H, m, H4′), 7.63 – 7.69 (1 H, m, H11), 7.56 – 7.62 (1 H, m, H10), 7.29 (1 H, ddd, J = 7.4, 4.8, 1.3 Hz, H5′). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CD2Cl2): δ 156.46 (C), 155.23 (C), 149.67 (CH), 148.95 (C), 137.28 (CH), 136.67 (CH), 133.98 (C), 131.53 (C), 131.11 (CH), 130.56 (C), 129.43 (CH), 129.20 (CH), 128.67 (CH), 127.86 (CH), 127.31 (C), 127.15 (CH), 127.08 (CH), 126.75 (CH), 125.87 (C), 124.45 (CH), 121.80 (CH), 118.36 (CH). Elemental analysis, calcd. (%) for C22H14N2: C, 86.25; H, 4.61; N, 9.14; found C 86.12, H 4.55, N 9.05.

Complex 2b

To a solution of cis-(dmso)2PtMe2[19] (20 mg, 0.05 mmol) in acetone (5 mL) was added 16 mg of proligand 1b (0.05 mmol). The stirred solution was heated to 50° C and kept under a nitrogen atmosphere. After 5 h the mixture was cooled to room temperature, concentrated to small volume, and treated with pentane to form a precipitate. The solid was filtered off, washed with pentane, and vacuum-pumped to give the analytical sample 2b (27 mg, 90%) as an orange solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD2Cl2): δ 9.77 (1 H, d, JH-H = 6.0 Hz, 3JPt-H = 12.1 Hz, H6′), 9.54 (1 H, s, 3JPt-H = 32 Hz, H1), 9.04 (1 H, d, J = 8.5 Hz, H12), 8.53 (1 H, d, J = 7.3 Hz, H3′), 7.95 – 8.04 (3 H, m, H5,4′,9), 7.90 – 7.94 (1 H, m, H6), 7.78–7.88 (2 H, AB, J = 8.5 Hz, H7,8), 7.65 (1 H, t, J = 6.9 Hz, H11), 7.58 (1 H, t, J = 7.3 Hz, H10), 7.39 (1 H, t, J = 5.8 Hz, H5′), 3.15 – 3.25 (6 H, s, 3JPt-H = 18.4 Hz, Hdmso), 0.78 (3 H, s, 2JPt-H = 83 Hz, HMe-Pt). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CD2Cl2): δ 164.75 (C), 161.97 (C), 150.64 (CH), 146.61 (C), 141.42 (C), 138.93 (CH), 138.56 (CH), 133.51 (C), 131.15 (C), 130.48 (C), 128.98 (CH), 128.75 (CH), 128.60 (CH), 128.08 (CH), 127.78 (CH), 127.02 (C), 126.72 (CH), 126.24 (CH), 126.09 (C), 125.98 (CH), 125.11 (CH), 122.13 (CH), 43.82 (2CH3), −13.52 (CH3). Elemental analysis, calcd. (%) for C25H22N2OPtS: C 50.58; H, 3.74; found C, 50.47, H 3.68.

Complex Pt(1b)Cl(dmso)

To a solution of 2b (40 mg, 0.067 mmol) in 8 mL of acetone was added with vigorous stirring 0.34 mL of dmso and 0.67 mL of aqueous 0.1 M HCl (0.067 mmol). After 8 h the solution was concentrated to a small volume then extracted with CH2Cl2, dried with Na2SO4, and concentrated to a small volume. The residue was then treated with pentane to form a precipitate which was filtered, washed with pentane, and vacuum-pumped to give the analytical sample Pt(1b)Cl(dmso) (29 mg, 70%) as a yellow solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD2Cl2): δ 10.17 (1 H, s, 3JPt-H=25 Hz, H1), 9.64 (1 H, d, J=6.0 Hz, H6′), 9.13 (1 H, d, J=8.3 Hz, H12), 8.46 (1 H, d, J=9.0 Hz, H3′), 7.91 – 8.07 (4 H, m, H5,6,4′,9), 7.77 – 7.89 (2H, AB, J=8.5 Hz, H7,8), 7.53 – 7.67 (2 H, m, H10,11), 7.43 (1 H, t, J=6.0 Hz, H5′), 3.62 (6 H, s, 3JPt-H=12 Hz, Hdmso). Elemental analysis, calcd. (%) for C24H19ClN2OPtS: C, 46.95; H, 3.12; found C 46.78, H 3.01.

Complex 3b

To a solution of Pt(1b)Cl(dmso) (14.6 mg, 0.024 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (5 mL) was added 6.2 mg of PPh3 (0.024 mmol). The stirred solution was kept under a nitrogen atmosphere. After 2 h the mixture was concentrated to small volume and treated with pentane to form a precipitate. The solid was filtered off, washed with pentane, and vacuum-pumped to give the analytical sample 3b as a yellow solid (19 mg, 98%) that was crystallized with slow diffusion of pentane into CH2Cl2 solution. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD2Cl2): δ 9.86 (1 H, m, H6′), 8.52 (1 H, d, J = 8.3 Hz, H3′), 8.35 (1 H, s, 3JPt-H = 56 Hz, H1), 8.01 – 8.08 (1 H, m, H4′), 7.89 (1 H, d, J = 9 Hz), 7.74 – 7.81 (6 H, m), 7.71 (1 H, d, J = 8.3 Hz, H12), 7.66 (1 H, d, J = 8.8 Hz), 7.53 – 7.60 (2 H, m), 7.45 – 7.52 (1 H, m), 7.36 – 7.43 (1 H, m), 7.31 (1 H, ddd, J = 8.1, 6.9, 1 Hz, H5′), 7.23 – 7.29 (3 H, m), 7.11 – 7.20 (6 H, m), 6.40 (1 H, ddd, J = 8.4, 7.0, 1.4 Hz, H11). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CD2Cl2): δ 163.27 (CH), 148.5 (C), 145.05 (C), 142.30 (CH), 140.12 (CH), 135.32 – 135.87 (6CH), 133.0 (C), 130.97 (CH), 130.96 (CH), 129.91 (C), 129.53 (C), 129.29 (C), 128.94 (CH), 128.79 (CH), 128.60 (C), 128.53 (C), 128.41 (C), 127.7 – 128.14 (9CH), 127.36 (CH), 126.56 (C), 126.35 (CH), 126.09 (C), 126.03 (CH), 125.44 (CH), 125.21 (C), 124.74 (CH), 122.14 (CH). 31P NMR (162 MHz, CD2Cl2) δ 22.70 (JPt-P = 4301.5 Hz). Elemental analysis, calcd. (%) for C40H28ClN2PPt: C, 60.19; H, 3.54; found C 60.03, H 3.45.

Complexes P- and M-2a

To a solution of cis-(dmso)2PtMe2[19] (20 mg, 0.05 mmol) in acetone (5 mL) was added 21.3 mg of P-1a (0.05 mmol). The stirred solution was heated to 50° C and kept under a nitrogen atmosphere. After 5 h the mixture was cooled to room temperature, concentrated to small volume, and treated with pentane to form a precipitate. The solid was filtered off, washed with pentane, and vacuum-pumped to give the analytical sample P-2a (31 mg, 90%) as an orange solid. The same procedure was used to prepare M-2a from M-1a. 1H NMR (400 MHz CD2Cl2): δ 9.48 – 9.57 (1 H, m, 3JPt-H = 20 Hz, H6′), 8.36 – 8.41 (1 H, m), 8.10 (1 H, s, 3JPt-H = 62.5 Hz), 7.98 (2 H, s), 7.80 – 7.96 (7 H, m), 7.72 (1 H, dd, J = 8.1, 1.40 Hz), 7.61 – 7.67 (1 H, m), 7.24 (1 H, ddd, J = 7.4, 5.6, 1.5 Hz), 7.13 (1 H, ddd, J=8, 6.9, 1.1 Hz), 6.63 (1 H, ddd, J = 8.5, 6.9, 1.4 Hz), 2.99 (3 H, s, 3JPt-H = 18 Hz), 2.89 (3 H, s, 3JPt-H = 18 Hz), −0.38 (3 H, s, 2JPt-H = 83.3 Hz). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CD2Cl2): δ 162.18 (C), 148.49 (CH), 150.80 (CH), 145.68 (C), 140.90 (C), 138.69 (CH), 138.41 (CH), 133.56 (C), 131.73 (C), 131.70 (C), 130.04 (C), 129.63 (CH), 128.80 (CH), 128.44 (CH), 128.42 (C), 128.23 (C), 128.16 (CH), 128.01 (CH), 127.80 (CH), 127.56 (CH), 127.50 (CH), 127.21 (C), 127.17 (CH), 126.41 (CH), 126.05 (CH), 126.03 (C), 125.28 (2CH), 124.62 (C), 122.24 (CH), 44.05 (CH3), 43.88 (CH3), −14.21 (CH3). Elemental analysis, calcd. (%) for C33H26N2OPtS: C, 57.13; H, 3.78; found C 57.05, H 3.72.

Complexes P- and M-[2a,H+][BF4−]

To a solution of P-2a (5 mg, 7.2 μmol) in CH2Cl2 (2 mL) was added 3 mg of [H2O.HBF4]2[18C6][15] (2 mg, 4 μmol). After 2 h the mixture was concentrated to small volume and treated with Et2O to form a precipitate. The solid was filtered off, washed with Et2O, and vacuum pumped to give the analytical sample P-[2a,H+][BF4−] (5.2 mg, 92%) as a bright-orange solid. The same procedure was used to prepare M-[2a,H+][BF4−] from M-2a. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD2Cl2): δ 13.58 (1 H, br, NH), 9.87 (1 H, d, J = 5.5 Hz, 3JPt-H = 20 Hz, H6′), 9.00 (1 H, s, 3JPt-H = 64.2 Hz, H1), 8.79 (1 H, d, J = 7.8 Hz, H3′), 8.52 (2 H, s), 8.21 – 8.33 (2 H, m), 8.06 – 8.17 (2 H, m), 7.95 – 8.05 (2 H, m), 7.88 (1 H, d, J = 7.5 Hz, H13), 7.59 – 7.70 (2 H, m, H5′,16), 7.29 (1 H, m, H14), 6.87 (1 H, m, H15), 3.16 (3 H, s, 3JPt-H = 21 Hz), 3.06 (3 H, s, 3JPt-H = 21 Hz, Hdmso), −0.21 (3 H, s, 3JPt-H = 82 Hz, HMe-Pt). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CD2Cl2): δ 152.03(CH), 146.98 (CH), 140.99 (C), 140.22 (CH), 136.03 (C), 135.53 (CH), 134.1 (C), 134.14 (C), 133.01 (C), 132.18 (C), 131.70 (C), 129.94 (CH), 129.11 (CH), 128.88 (CH), 128.31 (C), 128.15 (CH), 128.01 (CH), 127.92 (CH), 127.25 (CH), 127.20 (C), 127.11 (CH), 126.75 (C), 126.71 (CH), 126.23 (CH), 126.15 (C), 126.04 (CH), 125.88 (C), 123.59 (C), 123.43 (CH), 120.03 (CH), 43.76 (CH3), 43.73 (CH3), −13.81 (CH3). Elemental analysis, calcd. (%) for C33H27BF4N2OPtS: C, 50.72; H, 3.48; N, 3.58; found C 50.83, H 3.53, N 3.49.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Ministère de l’Education Nationale, de la Recherche et de la Technologie, the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS), the ANR (12-BS07-0004-METALHEL-01 and ANR-10-BLAN-724-1-NCPCHEM) and the LIA CNRS Rennes-Durham (MMC) for financial support. G.M. thanks the National Institute of Health, Minority Biomedical Research Support (1 SC3 GM089589-04 and 3 S06 GM008192-27S1) and the Henry Dreyfus Teacher-Scholar Award for financial support, while K.K.D. thanks the NIH MARC Grant 2T34GM008253-26 for a research fellowship. J.A. acknowledges support from the National Science Foundation grant CHE-1265833 and the Center for Computational Research at the University at Buffalo for providing computational resources. M.S. is grateful from financial support from the Foundation for Polish Science Homing Plus programme co-financed by the European Regional Development Fund and the Ministry of Science and Higher Education in Poland ‘Outstanding Young Scientist’ scholarship.

Footnotes

Supplementary information for this article is given via a link at the end of the document.

Contributor Information

Jochen Autschbach, Email: jochena@buffalo.edu..

Jeanne Crassous, Email: jeanne.crassous@univ-rennes1.fr.

References

- 1.a) Amabilino D, editor. Chirality at the Nanoscale, Nanoparticles, Surfaces, Materials and more. Wiley-VCH; 2009. [Google Scholar]; b) Feringa BL, Browne WR, editors. Molecular Switches. 2. Wiley-VCH; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.a) Shen Y, Chen C-F. Chem Rev. 2012;112:1463–1535. doi: 10.1021/cr200087r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Gingras M. Chem Soc Rev. 2013;42:1051–1095. doi: 10.1039/c2cs35134j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Bosson J, Gouin J, Lacour J. Chem Soc Rev. 2014;43:2824–2840. doi: 10.1039/c3cs60461f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Saleh N, Shen C, Crassous J. Chem Sci. 2014;5:3680–3694. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Selected examples of CPL active helicenes: Field JE, Muller G, Riehl JP, Venkataraman D. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:11808–11809. doi: 10.1021/ja035626e.Sawada Y, Furumi S, Takai A, Takeuchi M, Noguchi K, Tanaka K. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:4080–4083. doi: 10.1021/ja300278e.Phillips KES, Katz TJ, Jockusch S, Lovinger AJ, Turro NJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:11899–11907. doi: 10.1021/ja011706b.Kaseyama T, Furumi S, Zhang X, Tanaka K, Takeuchi M. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2011;50:3684–3687. doi: 10.1002/anie.201007849.Shen C, Anger E, Srebro M, Vanthuyne N, Deol KK, Jefferson TD, Jr, Muller G, Williams JAG, Toupet L, Roussel C, Autschbach J, Réau R, Crassous J. Chem Sci. 2014;5:1915–1927. doi: 10.1039/C3SC53442A.Nakamura K, Furumi S, Takeuchi M, Shibuya T, Tanaka K. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:5555–5558. doi: 10.1021/ja500841f.

- 4.a) Norel L, Rudolph M, Vanthuyne N, Williams JAG, Lescop C, Roussel C, Autschbach J, Crassous J, Réau R. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2010;49:99–102. doi: 10.1002/anie.200905099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Anger E, Rudolph M, Norel L, Zrig S, Shen C, Vanthuyne N, Toupet L, Williams JAG, Roussel C, Autschbach J, Crassous J, Réau R. Chem Eur J. 2011;17:14178–14198. doi: 10.1002/chem.201101866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Anger E, Rudolph M, Shen C, Vanthuyne N, Toupet L, Roussel C, Autschbach J, Crassous J, Réau R. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:3800–3803. doi: 10.1021/ja200129y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Shen C, Anger E, Srebro M, Vanthuyne N, Toupet L, Roussel C, Autschbach J, Réau R, Crassous J. Chem Eur J. 2013;19:16722–16728. doi: 10.1002/chem.201302479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Crespo O, Eguillor B, Esteruelas MA, Fernandez I, Garcia-Raboso J, Gomez-Gallego M, Martin-Ortiz M, Olivan M, Sierra MA. Chem Comm. 2012;48:5328–5330. doi: 10.1039/c2cc30356f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maeda H, Bando Y. Pure Appl Chem. 2013;85:1967–1978.Balzani V, Venturi M, Credi A, editors. Molecular Devices and Machines: A Journey into the Nanoworld. Wiley; 2006. Examples of CPL-active cyclo-iridiated complexes: Schaffner-Hamann C, von Zelewsky A, Barbieri A, Barigelletti F, Muller G, Riehl JP, Neels A. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:9339–9348. doi: 10.1021/ja048655d.Walters RS, Kraml CM, Byrne N, Ho DM, Qin Q, Coughlin FJ, Bernhard S, Pascal RA., Jr J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:16435–16441. doi: 10.1021/ja806958x.Yang L, von Zelewsky A, Nguyen HP, Muller G, Labat G, Stoeckli-Evans H. Inorg Chim Acta. 2009;362:3853–3856. doi: 10.1016/j.ica.2008.10.011.Ashizawa M, Yang L, Kobayashi K, Sato H, Yamagishi A, Okuda F, Harada T, Kuroda R, Haga M. Dalton Trans. 2009:1700–1702. doi: 10.1039/b820821m.

- 6.For previous helicenes with bipyridine moieties see: Fox JM, Katz TJ. J Org Chem. 1999;64:302–305. doi: 10.1021/jo9817570.Deshayes K, Broene RD, Chao I, Knobler CB, Diederich F. J Org Chem. 1991;56:6787–6795.Takenaka N, Sarangthem RS, Captain B. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2008;47:9708–9710. doi: 10.1002/anie.200803338.Chen J, Captain B, Takenaka N. Org Lett. 2011;13:1654–1657. doi: 10.1021/ol200102c.

- 7.Lightner DA, Hefelfinger DT, Powers TW, Frank GW, Trueblood KN. J Am Chem Soc. 1972;94:3492–3497. [Google Scholar]

- 8.a) Crassous J. Chem Soc Rev. 2009;38:830–845. doi: 10.1039/b806203j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Crassous J. Chem Comm. 2012;48:9684–9692. doi: 10.1039/c2cc31542d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Zhou YH, Li J, Wu T, Zhao XP, Xu QL, Li X-L, Yu M-B, Wang LL, Sun P, Zheng YX. Inorg Chem Commun. 2013;29:18–21. [Google Scholar]; d) Kaes C, Katz A, Hosseini MW. Chem Rev. 2000;100:3553–3590. doi: 10.1021/cr990376z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.a) Butschke B, Schwarz H. Chem Sci. 2012;3:308–326. [Google Scholar]; b) Moorlag C, Wolf MO, Bohne C, Patrick BO. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:6382–6393. doi: 10.1021/ja043573a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Selected examples: Minghetti G, Stoccoro S, Cinellu MA, Soro B, Zucca A. Organometallics. 2003;22:4770–4777.Zucca A, Cordeschi D, Stoccoro S, Cinellu MA, Minghetti G, Chelucci G, Manassero M. Organometallics. 2011;30:3064–3074.Zucca A, Cordeschi D, Maidich L, Pilo MI, Masolo E, Stoccoro S, Cinellu MA, Galli S. Inorg Chem. 2013;52:7717–7731. doi: 10.1021/ic400908f.Petretto GL, Rourke JP, Maidich L, Stoccoro S, Cinellu MA, Minghetti G, Clarkson GJ, Zucca A. Organometallics. 2012;31:2971–2977.Maidich L, Zuri G, Stoccoro S, Cinellu MA, Masia M, Zucca A. Organometallics. 2013;32:438–448.

- 11.The same successive reactions achieved on proligand 1a resulted in a mixture of compounds, probably due to the steric hindrance of the helix and of the PPh3 ligand.

- 12.Nakai Y, Mori T, Sato K, Inoue Y. J Phys Chem A. 2013;117:5082–5092. doi: 10.1021/jp403426w.Napagoda M, Rulisek L, Jancarik A, Klivar J, Samal M, Stara IG, Stary I, Solinova V, Kasicka V, Svatos A. Chem Plus Chem. 2013;78:937. doi: 10.1002/cplu.201300258. and references therein; Latterini L, Galletti E, Passeri R, Barbafina A, Urbanelli L, Emiliani C, Elisei F, Fontana F, Mele A, Caronna T. J Photochem Photobio A: Chem. 2011;222:307–313.Alkorta I, Elguero J, Roussel C. Comput Theor Chem. 2011;966:334–339.

- 13.a) Anger E, Srebro M, Vanthuyne N, Toupet L, Rigaut S, Roussel C, Autschbach J, Crassous J, Réau R. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:15628–15631. doi: 10.1021/ja304424t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Graule S, Rudolph M, Vanthuyne N, Autschbach J, Roussel C, Crassous J, Réau R. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:3183–3185. doi: 10.1021/ja809396f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Graule S, Rudolph M, Shen W, Lescop C, Williams JAG, Autschbach J, Crassous J, Réau R. Chem Eur J. 2010;16:5976–6005. doi: 10.1002/chem.200903234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Mendola D, Saleh N, Vanthuyne N, Roussel C, Toupet L, Castiglione F, Caronna T, Mele A, Crassous J. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2014;53:5786–5790. doi: 10.1002/anie.201401004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.For an example of acid-base ECD switch see: Anger E, Srebro M, Vanthuyne N, Roussel C, Toupet L, Autschbach J, Réau R, Crassous J. Chem Comm. 2014;50:2854–2856. doi: 10.1039/c3cc47825d.For an example of chemical-stimuli CPL switch see: Maeda H, Bando Y, Shimomura K, Yamada I, Naito M, Nobusawa K, Tsumatori H, Kawai T. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:9266–9269. doi: 10.1021/ja203206g.

- 15.Atwood JL, Alvanipour A, Zhang H. J Cryst Spectrosc Res. 1992;22:349–352. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crabtree RH. Science. 2010;330:455–456. doi: 10.1126/science.1197652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fang Y-Q, Hanan GS. Synlett. 2003;6:852–854. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ramírez-Monroy A, Swager TM. Organometallics. 2011;30:2464–2467. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Appleton TG, Hall JR, Williams MA. J Organomet Chem. 1986;303:139–149. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.