Abstract

Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) incidence varies with migration and nativity, suggesting an influence of acculturation on risk. In population-based California data including 1,483 Hispanic and 348 Asian/Pacific Islander (API) HL cases, we examined HL rates in residential neighborhoods classified by ethnic enclave status (measuring degree of acculturation) and socioeconomic status (SES). Rates were inversely associated with enclave intensity, although associations varied by gender and race. In females, the enclave effect was stronger in low-SES settings, but rates were higher in less-ethnic/high-SES than more-ethnic/low-SES neighborhoods--diminishing enclave intensity affected rates more than higher SES. In Hispanics, associations were modest, and only females experienced SES modification of rates; in APIs, the enclave effect was much stronger. Thus, acculturation measured by residence in ethnic enclaves affects HL rates independently of neighborhood SES but in complex patterns. Living in less-ethnic neighborhoods may increase HL rates by facilitating social isolation and other gender-specific exposures implicated in risk.

Keywords: Hodgkin lymphoma, ethnic enclave, acculturation, epidemiology, immigration

INTRODUCTION

Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) is a B-cell malignancy whose etiology is influenced by socio-environmental conditions, as evidenced by age-specific secular trends in incidence levels [1-3], variation in rates with socioeconomic status (SES) [4-6], and changes over time in risk factors implicating social isolation and timing of key viral infections [7-10]. HL rates also rise after migration from lower- to higher-affluence countries [11,12], and vary by nativity [3,4,13,14], which may offer novel insights into mechanisms underlying HL incidence variation. In particular, the higher HL rates in US-born than foreign-born Hispanics and Asians/Pacific Islanders (APIs), and lower HL rates among US-born Hispanics and APIs than whites [13,14], suggest a role for post-immigration characteristics such as acculturation, the adoption of behaviors and practices of the host country.

One measure of acculturation among migrants is residence in an ethnic enclave, a neighborhood that maintains native cultural mores and is culturally and/or ethnically distinct compared with surrounding areas. For US Hispanics and APIs, living in an ethnic enclave has been shown to enhance social and economic engagement for recent immigrants, as well as to reinforce native customs [15,16]. As residence in ethnic enclaves relates to nativity and affects health behaviors [16,17] and illness [18,19], including numerous cancers [13, 20-26], it also may influence HL incidence.

A first examination of HL rates across neighborhood ethnic enclave status in a small group of APIs in California found lower rates among women, but not men, in neighborhoods of greater ethnic enclave intensity and higher SES [13]. However, the association of ethnic enclave residence with HL incidence has never before been studied in US Hispanics, nor in APIs in the detail appropriate to HL epidemiologic heterogeneity [27]. Therefore, we compared HL rates overall and by selected histologic subtype across ethnic enclave levels by age group, gender, and neighborhood SES in California Hispanics and APIs, populations with sizable immigrant subgroups but differing HL incidence patterns [4,5].

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient Data

We identified all California residents newly diagnosed during the years 1988-1992 and 1998-2002 with primary classical HL (International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, 3rd Edition (ICD-O-3), morphology codes 9650-9655, 9663-9667) reported to the California Cancer Registry (CCR), which comprises four National Cancer Institute Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) registries [28]. We chose these time periods because of the availability of census small-area-level population characteristics for calculating rates by neighborhood ethnic enclave and SES (determined only for decennial census years), and combined data from the two pericensal periods to maximize statistical power for stratified analyses, having found no significant incidence rate differences between the two periods for HL overall, or by gender, age, SES, enclave, or histologic subtype (data not shown). For all cases, we obtained registry data (routinely abstracted from the medical record) on patient age, gender, race/ethnicity, residential address, birthplace (imputed [29] for the 24.3% of Hispanics and 27.9% of APIs with birthplace missing), and tumor histologic subtype at diagnosis. Classification of race and ethnicity (obtained also from death certificates) was enhanced using surname algorithms [30,31]. Because of the unusual epidemiologic profile and elevated incidence of HIV-related HL during the study period [32], we excluded 83 Hispanic (5.4%) and two API (0.6%) cases designated as HIV-positive by registry and/or death-certificate data [33]. These exclusions left 1,463 Hispanic HL cases and 348 API HL cases (74 Chinese, 20 Japanese, 112 Filipinos, 28 Vietnamese, 43 Asian Indians, and 71 others) for analysis (including 220 APIs from our previous study [13]).

Neighborhood Ethnic Enclave and SES

We previously determined neighborhood ethnic enclave status for California cancer patients for the two pericensal periods using the census block group or census tract to which each patient's residential address at diagnosis had been geocoded [34]. The enclave indices were based on Census 2000 long form variables selected via principal components analysis. For Hispanics, these variables were the percentages of: foreign-born residents, recent immigrants, households that are linguistically isolated, Spanish-language-speaking households that are linguistically isolated, all language speakers with limited English proficiency, Spanish language speakers with limited English proficiency, and Hispanic residents. For APIs, the index was based on the percentages of: recent immigrants, API-language-speaking households that are linguistically isolated, API language speakers with limited English proficiency, and API residents. The indices (which explained 67.7% and 63.4% of the variability in the Hispanic and API data, respectively) were classified into quintiles based on their distributions across all California census tracts in the two census periods. To increase sample sizes within exposure categories, enclave quintiles were grouped into three categories of intensity, designated as more ethnic (highest quintile, 5), intermediate (second highest quintile, 4) and less ethnic (lowest three quintiles, 1-3). Each patient was assigned the appropriate ethnic enclave index of his/her neighborhood at diagnosis.

To assign neighborhood SES (hereafter called SES), we used census-tract-level indices that incorporated 1990 and 2000 census data on tract-level education, income, occupation, and housing costs [35]. For these census years, we categorized the respective indices into tertiles based on the distribution of the composite SES indices across all California census tracts (5,858 in 1990, 7,049 in 2000) and assigned each patient the SES tertile of his/her census tract at diagnosis. For sample size reasons, we also dichotomized SES as low (lowest tertile) or high (higher two tertiles). The 0.3% of cases from census tracts where SES values could not be computed were assigned SES values based on a randomly selected census tract within their county of residence, and enclave values were then assigned accordingly.

Population Data

For denominators of ethnic enclave-specific incidence rates, we used 1990 and 2000 US Census population estimates by age group, race/ethnicity, and gender at the census-tract level, assuming the estimates to be constant within the five years surrounding each census.

Incidence Rates and Rate Ratios

We computed average annual age-adjusted (standardized to the 2000 US standard million population) HL incidence rates per 100,000 population and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the period 1988-1992/1998-2002. As overall rates may obscure effect modification by age and gender, we further calculated rates by gender; for the age ranges 0-14, 15-39, 40-54 and ≥ 55 years (hereafter called “children,” “adolescents/young adults (AYAs),” “middle-aged adults,” and “older adults”), which demarcate groups with distinct HL incidence rates and risk factors [36]; and for Hispanics also by 10-year age group. We present these data for classical HL overall and its two most common histologic subtypes, nodular sclerosis (NS) (ICD-O-3 codes 9663-9667) and mixed cellularity (MC) (code 9652); the numbers of Hispanic and API cases, respectively, diagnosed with the other histologic subtypes were 50 and 9 for lymphocyte rich (code 9653-9655), 38 and 5 for lymphocyte depletion (code 9651), and 168 and 49 for classical HL not otherwise specified (code 9650). For APIs, rates are not presented by gender for NS or MC because of sample size constraints. To compare pairs of incidence rates, we calculated incidence rate ratios (IRRs) and 95% CIs, considering as significant any differences between two rates for which 95% CIs around the IRR did not include 1. IRRs are presented for comparisons of rates in less-ethnic to more-ethnic enclaves, i.e., more vs. less acculturation.

All analyses used SEER*Stat software [37], The study had the oversight of the institutional review board at the Cancer Prevention Institute of California.

RESULTS

Hispanics

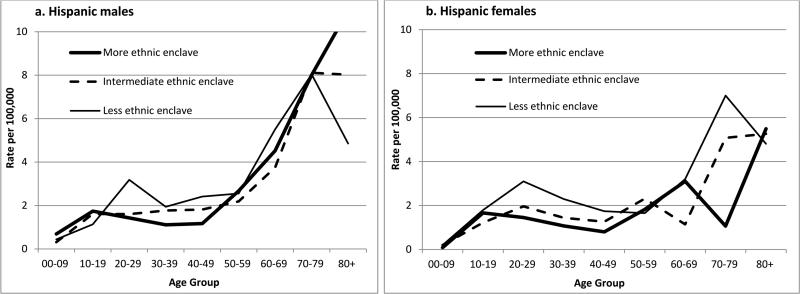

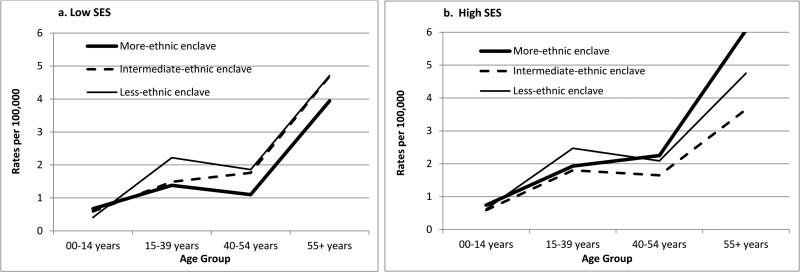

The overall HL incidence rate (2.03 per 100,000 Hispanics) was 35% higher for those residing in less-ethnic relative to more-ethnic enclaves, but significantly higher only for females (Table 1). AYA and middle-aged adults of both genders had higher rates for less-ethnic neighborhoods (Table 2), but among females, the rate elevation occurred over a broader young-adult age range than among males (Figures 1a and 1b). With stratification by SES, enclave-specific rates varied significantly only among low-SES females overall. For AYAs, Figures 2a and b show that rates were higher in less-ethnic than more-ethnic enclaves at both SES levels, although more clearly in low-SES neighborhoods. Similar elevation of rates in less- than more-ethnic enclaves also occurred at both SES levels for NS (IRRs for AYAs: low SES, 1.60 (1.07-2.33); high SES, 1.55 (1.01-2.46)) and for MC.

Table 1.

Age-adjusted incidence rates*, incidence rate ratios (IRRs), and 95% confidence intervals (CIs), of classical Hodgkin lymphoma and selected histologic subtypes, by ethnic enclave tertile, Hispanics, California, 1988-1992/1998-2002

| Characteristics | Hispanic Enclave§ | All classical Hodgkin lymphoma | Nodular sclerosis | Mixed cellularity | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 1463 | N = 877 | N = 330 | ||||||||

| N | Rate* (95% CI) | IRR (95% CI) | N | Rate* (95% CI) | IRR (95% CI) | N | Rate* (95% CI) | IRR (95% CI) | ||

| ALL COMBINED | ||||||||||

| More ethnic | 603 | 1.81 (1.63-2.00) | 1.00 (reference) | 356 | 0.89 (0.77-1.02) | 1.00 (reference) | 148 | 0.55 (0.45-0.67) | 1.00 (reference) | |

| Intermediate | 344 | 1.96 (1.71-2.23) | 1.08 (0.91-1.28) | 192 | 0.90 (0.75-1.06) | 1.01 (0.80-1.26) | 83 | 0.55 (0.42-0.71) | 1.01 (0.72-1.40) | |

| Less ethnic | 516 | 2.45 (2.21-2.71) | 1.35 (1.17-1.56) | 329 | 1.29 (1.14-1.46) | 1.46 (1.21-1.76) | 99 | 0.61 (0.48-0.76) | 1.11 (0.82-1.51) | |

| SEX | ||||||||||

| Male | More ethnic | 354 | 2.35 (2.02-2.71) | 1.00 (reference) | 181 | 0.93 (0.75-1.15) | 1.00 (reference) | 109 | 0.86 (0.66-1.11) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Intermediate | 190 | 2.30 (1.89-2.76) | 0.98 (0.77-1.24) | 92 | 0.93 (0.69-1.24) | 1.00 (0.69-1.43) | 53 | 0.71 (0.49-0.99) | 0.82 (0.52-1.27) | |

| Less ethnic | 268 | 2.63 (2.26-3.04) | 1.12 (0.91-1.38) | 159 | 1.23 (1.02-1.47) | 1.31 (0.99-1.75) | 63 | 0.82 (0.60-1.10) | 0.95 (0.63-1.42) | |

| Female | More ethnic | 249 | 1.40 (1.21-1.62) | 1.00 (reference) | 175 | 0.87 (0.72-1.04) | 1.00 (reference) | 39 | 0.30 (0.20-0.42) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Intermediate | 154 | 1.69 (1.40-2.03) | 1.20 (0.94-1.53) | 100 | 0.90 (0.71-1.12) | 1.03 (0.77-1.39) | 30 | 0.42 (0.27-0.61) | 1.39 (0.79-2.42) | |

| Less ethnic | 248 | 2.30 (1.99-2.64) | 1.64 (1.33-2.02) | 170 | 1.36 (1.15-1.61) | 1.57 (1.22-2.01) | 36 | 0.44 (0.30-0.62) | 1.46 (0.86-2.46) | |

| AGE GROUP AT DIAGNOSIS | ||||||||||

| 00-14 years | More ethnic | 92 | 0.68 (0.55-0.83) | 1.00 (reference) | 62 | 0.47 (0.36-0.60) | 1.00 (reference) | 24 | 0.17 (0.11-0.25) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Intermediate | 40 | 0.59 (0.42-0.81) | 0.87 (0.58-1.28) | 25 | 0.38 (0.24-0.55) | 0.81 (0.49-1.30) | 12 | 0.17 (0.09-0.30) | 1.03 (0.47-2.14) | |

| Less ethnic | 40 | 0.58 (0.41-0.79) | 0.85 (0.57-1.25) | 28 | 0.41 (0.27-0.59) | 0.87 (0.54-1.39) | 8 | 0.12 (0.05-0.23) | 0.69 (0.27-1.58) | |

| 15-39 years | More ethnic | 310 | 1.44 (1.28-1.61) | 1.00 (reference) | 220 | 1.01 (0.88-1.15) | 1.00 (reference) | 51 | 0.24 (0.18-0.32) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Intermediate | 179 | 1.67 (1.43-1.94) | 1.16 (0.96-1.41) | 125 | 1.17 (0.97-1.40) | 1.16 (0.92-1.46) | 29 | 0.27 (0.18-0.39) | 1.13 (0.69-1.84) | |

| Less ethnic | 287 | 2.43 (2.16-2.73) | 1.69 (1.43-2.00) | 223 | 1.89 (1.65-2.16) | 1.88 (1.55-2.28) | 28 | 0.24 (0.16-0.35) | 1.02 (0.61-1.66) | |

| 40-54 years | More ethnic | 66 | 1.22 (0.94-1.55) | 1.00 (reference) | 28 | 0.52 (0.34-0.75) | 1.00 (reference) | 19 | 0.34 (0.21-0.54) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Intermediate | 53 | 1.70 (1.27-2.22) | 1.39 (0.95-2.04) | 21 | 0.65 (0.40-1.00) | 1.26 (0.68-2.32) | 18 | 0.62 (0.37-0.98) | 1.80 (0.89-3.64) | |

| Less ethnic | 80 | 2.06 (1.63-2.56) | 1.69 (1.20-2.38) | 45 | 1.12 (0.82-1.51) | 2.18 (1.32-3.65) | 24 | 0.64 (0.41-0.95) | 1.85 (0.97-3.60) | |

| 55+ years | More ethnic | 135 | 4.17 (3.46-4.98) | 1.00 (reference) | 46 | 1.49 (1.07-2.02) | 1.00 (reference) | 54 | 1.66 (1.22-2.19) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Intermediate | 72 | 4.08 (3.15-5.19) | 0.98 (0.71-1.33) | 21 | 1.21 (0.73-1.89) | 0.81 (0.45-1.43) | 24 | 1.33 (0.84-2.02) | 0.81 (0.46-1.36) | |

| Less ethnic | 109 | 4.75 (3.87-5.77) | 1.14 (0.87-1.49) | 33 | 1.37 (0.93-1.94) | 0.92 (0.56-1.50) | 39 | 1.69 (1.18-2.34) | 1.02 (0.64-1.60) | |

| NEIGHBORHOOD SES | ||||||||||

| Low | More ethnic | 523 | 1.72 (1.53-1.91) | 1.00 (reference) | 314 | 0.87 (0.75-1.00) | 1.00 (reference) | 123 | 0.49 (0.39-0.61) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Intermediate | 145 | 2.04 (1.64-2.50) | 1.19 (0.93-1.50) | 75 | 0.84 (0.62-1.12) | 0.97 (0.70-1.34) | 40 | 0.66 (0.43-0.95) | 1.35 (0.84-2.09) | |

| Less ethnic | 80 | 2.29 (1.71-2.99) | 1.33 (0.98-1.78) | 50 | 1.14 (0.79-1.60) | 1.31 (0.88-1.91) | 17 | 0.62 (0.33-1.06) | 1.27 (0.65-2.28) | |

| High | More ethnic | 80 | 2.62 (1.98-3.41) | 1.00 (reference) | 42 | 1.09 (0.73-1.57) | 1.00 (reference) | 25 | 1.07 (0.63-1.66) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Intermediate | 199 | 1.90 (1.60-2.25) | 0.73 (0.53-1.01) | 117 | 0.93 (0.74-1.16) | 0.86 (0.55-1.36) | 43 | 0.48 (0.33-0.67) | 0.45 (0.25-0.84) | |

| Less ethnic | 436 | 2.48 (2.22-2.76) | 0.94 (0.71-1.28) | 279 | 1.32 (1.16-1.51) | 1.22 (0.82-1.86) | 82 | 0.61 (0.47-0.77) | 0.57 (0.34-1.02) | |

| ENCLAVE*SES‡ | ||||||||||

| More Ethnic/Low SES | 523 | 1.72 (1.53-1.91) | 1.00 (reference) | 314 | 0.87 (0.75-1.00) | 1.00 (reference) | 123 | 0.49 (0.39-0.61) | 1.00 (reference) | |

| More Ethnic/High SES | 80 | 2.62 (1.98-3.41) | 1.53 (1.13-2.03) | 42 | 1.09 (0.73-1.57) | 1.26 (0.82-1.87) | 25 | 1.07 (0.63-1.66) | 2.19 (1.24-3.62) | |

| Intermediate/Low SES | 145 | 2.04 (1.64-2.50) | 1.19 (0.93-1.50) | 75 | 0.84 (0.62-1.12) | 0.97 (0.70-1.34) | 40 | 0.66 (0.43-0.95) | 1.35 (0.84-2.09) | |

| Intermediate/High SES | 199 | 1.90 (1.60-2.25) | 1.11 (0.90-1.36) | 117 | 0.93 (0.74-1.16) | 1.08 (0.82-1.41) | 43 | 0.48 (0.33-0.67) | 0.98 (0.64-1.49) | |

| Less Ethnic/Low SES | 80 | 2.29 (1.71-2.99) | 1.33 (0.98-1.78) | 50 | 1.14 (0.79-1.60) | 1.31 (0.88-1.91) | 17 | 0.62 (0.33-1.06) | 1.27 (0.65-2.28) | |

| Less Ethnic/High SES | 436 | 2.48 (2.22-2.76) | 1.44 (1.24-1.69) | 279 | 1.32 (1.16-1.51) | 1.53 (1.25-1.87) | 82 | 0.61 (0.47-0.77) | 1.25 (0.89-1.74) | |

Per 100,000 person-years and standardized to the 2000 U.S. standard population

More ethnic (Enclave Quintile 5); Intermediate (Enclave Quintile 4); Less ethnic (Enclave Quintile 1-3)

--Per confidentiality regulations of the California Cancer Registry, case counts and rates based on fewer than 5 cases are suppressed, and statistics are not computed.

Low SES comprises the lowest SES tertile; high SES comprises the middle and highest SES tertiles.

Bolding denotes statistical significance.

Table 2.

Age-adjusted incidence rates*, incidence rate ratios (IRRs), and 95% confidence intervals (CIs), of classical Hodgkin lymphoma and selected histologic subtypes, by ethnic enclave tertile, Hispanics, California, 1988-92/1998-02

| Characteristics | Hispanic Enclave§ | All classical Hodgkin lymphoma | Nodular sclerosis | Mixed cellularity | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | ||||||||||||||

| N = 812 | N = 651 | N = 432 | N = 445 | N = 225 | N = 105 | ||||||||||||||

| N | Rate* (95% CI) | IRR (95% CI) | N | Rate* (95% CI) | IRR (95% CI) | N | Rate* (95% CI) | IRR (95% CI) | N | Rate* (95% CI) | IRR (95% CI) | N | Rate* (95% CI) | IRR (95% CI) | N | Rate* (95% CI) | IRR (95% CI) | ||

| ALL COMBINED | |||||||||||||||||||

| More ethnic | 354 | 2.35 (2.02-2.71) | 1.00 (reference) | 249 | 1.40 (1.21-1.62) | 1.00 (reference) | 181 | 0.93 (0.75-1.15) | 1.00 (reference) | 175 | 0.87 (0.72-1.04) | 1.00 (reference) | 109 | 0.86 (0.66-1.11) | 1.00 (reference) | 39 | 0.30 (0.20-0.42) | 1.00 (reference) | |

| Intermediate | 190 | 2.30 (1.89-2.76) | 0.98 (0.77-1.24) | 154 | 1.69 (1.40-2.03) | 1.20 (0.94-1.53) | 92 | 0.93 (0.69-1.24) | 1.00 (0.69-1.43) | 100 | 0.90 (0.71-1.12) | 1.03 (0.77-1.39) | 53 | 0.71 (0.49-0.99) | 0.82 (0.52-1.27) | 30 | 0.42 (0.27-0.61) | 1.39 (0.79-2.42) | |

| Less ethnic | 268 | 2.63 (2.26-3.04) | 1.12 (0.91-1.38) | 248 | 2.30 (1.99-2.64) | 1.64 (1.33-2.02) | 159 | 1.23 (1.02-1.47) | 1.31 (0.99-1.75) | 170 | 1.36 (1.15-1.61) | 1.57 (1.22-2.01) | 63 | 0.82 (0.60-1.10) | 0.95 (0.63-1.42) | 36 | 0.44 (0.30-0.62) | 1.46 (0.86-2.46) | |

| AGE GROUP AT DIAGNOSIS | |||||||||||||||||||

| 00-14 years | More ethnic | 65 | 0.92 (0.71-1.17) | 1.00 (reference) | 27 | 0.43 (0.29-0.63) | 1.00 (reference) | 39 | 0.56 (0.40-0.76) | 1.00 (reference) | 23 | 0.37 (0.23-0.55) | 1.00 (reference) | 21 | 0.28 (0.18-0.44) | 1.00 (reference) | -- | -- | -- |

| Intermediate | 24 | 0.69 (0.44-1.03) | 0.76 (0.45-1.22) | 16 | 0.49 (0.28-0.79) | 1.12 (0.57-2.16) | 13 | 0.38 (0.20-0.65) | 0.69 (0.34-1.31) | 12 | 0.37 (0.19-0.64) | 1.00 (0.45-2.08) | 9 | 0.26 (0.12-0.49) | 0.91 (0.36-2.07) | -- | -- | -- | |

| Less ethnic | 22 | 0.62 (0.39-0.93) | 0.67 (0.39-1.11) | 18 | 0.54 (0.32-0.85) | 1.25 (0.65-2.35) | 15 | 0.42 (0.23-0.69) | 0.75 (0.39-1.40) | 13 | 0.39 (0.21-0.67) | 1.07 (0.50-2.19) | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| 15-39 years | More ethnic | 167 | 1.43 (1.22-1.68) | 1.00 (reference) | 143 | 1.44 (1.21-1.70) | 1.00 (reference) | 102 | 0.86 (0.70-1.04) | 1.00 (reference) | 118 | 1.19 (0.98-1.43) | 1.00 (reference) | 40 | 0.35 (0.24-0.48) | 1.00 (reference) | 11 | 0.11 (0.06-0.21) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Intermediate | 96 | 1.71 (1.38-2.09) | 1.19 (0.91-1.55) | 83 | 1.63 (1.29-2.03) | 1.13 (0.85-1.50) | 58 | 1.06 (0.80-1.37) | 1.23 (0.87-1.73) | 67 | 1.30 (1.00-1.66) | 1.10 (0.80-1.50) | 20 | 0.35 (0.21-0.54) | 1.00 (0.55-1.77) | 9 | 0.19 (0.09-0.36) | 1.66 (0.60-4.46) | |

| Less ethnic | 143 | 2.26 (1.90-2.67) | 1.58 (1.25-1.99) | 144 | 2.61 (2.20-3.08) | 1.81 (1.42-2.31) | 106 | 1.69 (1.38-2.05) | 1.97 (1.48-2.62) | 117 | 2.11 (1.75-2.54) | 1.78 (1.36-2.33) | 19 | 0.30 (0.18-0.47) | 0.87 (0.47-1.55) | 9 | 0.18 (0.08-0.33) | 1.55 (0.56-4.16) | |

| 40-54 years | More ethnic | 41 | 1.53 (1.10-2.09) | 1.00 (reference) | 25 | 0.91 (0.59-1.34) | 1.00 (reference) | 15 | 0.54 (0.30-0.89) | 1.00 (reference) | 13 | 0.49 (0.26-0.84) | 1.00 (reference) | 15 | 0.56 (0.31-0.93) | 1.00 (reference) | -- | -- | -- |

| Intermediate | 30 | 1.91 (1.28-2.74) | 1.24 (0.75-2.05) | 23 | 1.48 (0.94-2.23) | 1.63 (0.88-3.01) | 11 | 0.67 (0.33-1.22) | 1.25 (0.52-2.97) | 10 | 0.63 (0.30-1.16) | 1.27 (0.50-3.17) | 10 | 0.69 (0.33-1.27) | 1.23 (0.49-2.93) | 8 | 0.55 (0.24-1.08) | 4.25 (1.11-19.24) | |

| Less ethnic | 47 | 2.48 (1.82-3.31) | 1.62 (1.04-2.53) | 33 | 1.65 (1.13-2.33) | 1.82 (1.05-3.21) | 22 | 1.13 (0.71-1.72) | 2.10 (1.03-4.42) | 23 | 1.12 (0.71-1.69) | 2.28 (1.11-4.95) | 17 | 0.90 (0.52-1.44) | 1.59 (0.74-3.44) | 7 | 0.39 (0.15-0.79) | 2.98 (0.74-13.87) | |

| 55+ years | More ethnic | 81 | 6.13 (4.78-7.75) | 1.00 (reference) | 54 | 2.81 (2.09-3.71) | 1.00 (reference) | 25 | 1.84 (1.14-2.81) | 1.00 (reference) | 21 | 1.23 (0.75-1.90) | 1.00 (reference) | 33 | 2.61 (1.74-3.76) | 1.00 (reference) | 21 | 1.03 (0.63-1.60) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Intermediate | 40 | 5.27 (3.65-7.36) | 0.86 (0.55-1.31) | 32 | 3.21 (2.17-4.57) | 1.14 (0.70-1.82) | 10 | 1.55 (0.69-2.96) | 0.84 (0.33-1.92) | 11 | 1.04 (0.51-1.89) | 0.85 (0.36-1.89) | 14 | 1.78 (0.93-3.11) | 0.68 (0.32-1.38) | 10 | 0.99 (0.46-1.84) | 0.96 (0.39-2.18) | |

| Less ethnic | 56 | 5.40 (4.01-7.15) | 0.88 (0.60-1.29) | 53 | 4.21 (3.13-5.54) | 1.50 (0.99-2.25) | 16 | 1.37 (0.77-2.32) | 0.74 (0.36-1.55) | 17 | 1.33 (0.76-2.14) | 1.08 (0.53-2.20) | 23 | 2.33 (1.41-3.62) | 0.89 (0.48-1.64) | 16 | 1.23 (0.69-2.03) | 1.20 (0.57-2.46) | |

| NEIGHBORHOOD SES‡ | |||||||||||||||||||

| Low | More ethnic | 309 | 2.25 (1.92-2.63) | 1.00 (reference) | 214 | 1.31 (1.11-1.53) | 1.00 (reference) | 163 | 0.94 (0.74-1.17) | 1.00 (reference) | 151 | 0.83 (0.67-1.00) | 1.00 (reference) | 92 | 0.79 (0.59-1.03) | 1.00 (reference) | 31 | 0.24 (0.16-0.36) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Intermediate | 87 | 2.36 (1.75-3.11) | 1.05 (0.75-1.45) | 58 | 1.73 (1.24-2.33) | 1.32 (0.91-1.86) | 43 | 1.03 (0.64-1.56) | 1.09 (0.65-1.77) | 32 | 0.71 (0.46-1.06) | 0.86 (0.53-1.35) | 25 | 0.77 (0.43-1.26) | 0.97 (0.51-1.74) | 15 | 0.55 (0.28-0.95) | 2.27 (1.04-4.64) | |

| Less ethnic | 42 | 2.49 (1.62-3.66) | 1.11 (0.70-1.68) | 38 | 2.12 (1.39-3.08) | 1.62 (1.03-2.45) | 22 | 0.95 (0.56-1.59) | 1.01 (0.56-1.79) | 28 | 1.30 (0.78-2.04) | 1.57 (0.91-2.60) | 12 | 0.93 (0.40-1.81) | 1.18 (0.48-2.46) | 5 | 0.35 (0.11-0.87) | 1.46 (0.40-4.08) | |

| High | More ethnic | 45 | 3.18 (2.06-4.66) | 1.00 (reference) | 35 | 2.23 (1.48-3.22) | 1.00 (reference) | 18 | 0.87 (0.46-1.57) | 1.00 (reference) | 24 | 1.28 (0.76-2.03) | 1.00 (reference) | 17 | 1.53 (0.69-2.82) | 1.00 (reference) | 8 | 0.75 (0.31-1.47) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Intermediate | 103 | 2.23 (1.71-2.87) | 0.70 (0.44-1.16) | 96 | 1.69 (1.33-2.12) | 0.76 (0.49-1.22) | 49 | 0.86 (0.56-1.25) | 0.99 (0.47-2.09) | 68 | 1.04 (0.78-1.36) | 0.81 (0.47-1.47) | 28 | 0.66 (0.40-1.03) | 0.43 (0.19-1.09) | 15 | 0.33 (0.17-0.56) | 0.44 (0.17-1.24) | |

| Less ethnic | 226 | 2.65 (2.25-3.10) | 0.83 (0.55-1.32) | 210 | 2.34 (2.00-2.71) | 1.05 (0.70-1.62) | 137 | 1.29 (1.05-1.57) | 1.48 (0.79-2.89) | 142 | 1.37 (1.14-1.63) | 1.07 (0.65-1.86) | 51 | 0.80 (0.56-1.10) | 0.52 (0.25-1.23) | 31 | 0.45 (0.30-0.65) | 0.60 (0.27-1.56) | |

| ENCLAVE*SES‡ | |||||||||||||||||||

| More Ethnic/Low SES | 309 | 2.25 (1.92-2.63) | 1.00 (reference) | 214 | 1.31 (1.11-1.53) | 1.00 (reference) | 163 | 0.94 (0.74-1.17) | 1.00 (reference) | 151 | 0.83 (0.67-1.00) | 1.00 (reference) | 92 | 0.79 (0.59-1.03) | 1.00 (reference) | 31 | 0.24 (0.16-0.36) | 1.00 (reference) | |

| More Ethnic/High SES | 45 | 3.18 (2.06-4.66) | 1.41 (0.89-2.14) | 35 | 2.23 (1.48-3.22) | 1.70 (1.10-2.56) | 18 | 0.87 (0.46-1.57) | 0.93 (0.47-1.76) | 24 | 1.28 (0.76-2.03) | 1.55 (0.89-2.58) | 17 | 1.53 (0.69-2.82) | 1.94 (0.84-3.85) | 8 | 0.75 (0.31-1.47) | 3.08 (1.18-7.02) | |

| Intermediate/Low SES | 87 | 2.36 (1.75-3.11) | 1.05 (0.75-1.45) | 58 | 1.73 (1.24-2.33) | 1.32 (0.91-1.86) | 43 | 1.03 (0.64-1.56) | 1.09 (0.65-1.77) | 32 | 0.71 (0.46-1.06) | 0.86 (0.53-1.35) | 25 | 0.77 (0.43-1.26) | 0.97 (0.51-1.74) | 15 | 0.55 (0.28-0.95) | 2.27 (1.04-4.64) | |

| Intermediate/High SES | 103 | 2.23 (1.71-2.87) | 0.99 (0.73-1.34) | 96 | 1.69 (1.33-2.12) | 1.29 (0.97-1.72) | 49 | 0.86 (0.56-1.25) | 0.91 (0.57-1.43) | 68 | 1.04 (0.78-1.36) | 1.26 (0.89-1.78) | 28 | 0.66 (0.40-1.03) | 0.84 (0.47-1.44) | -- | -- | -- | |

| Less Ethnic/Low SES | 42 | 2.49 (1.62-3.66) | 1.11 (0.70-1.68) | 38 | 2.12 (1.39-3.08) | 1.62 (1.03-2.45) | 22 | 0.95 (0.56-1.59) | 1.01 (0.56-1.79) | 28 | 1.30 (0.78-2.04) | 1.57 (0.91-2.60) | 12 | 0.93 (0.40-1.81) | 1.18 (0.48-2.46) | -- | -- | -- | |

| Less Ethnic/High SES | 226 | 2.65 (2.25-3.10) | 1.18 (0.94-1.48) | 210 | 2.34 (2.00-2.71) | 1.79 (1.43-2.24) | 137 | 1.29 (1.05-1.57) | 1.37 (1.01-1.87) | 142 | 1.37 (1.14-1.63) | 1.66 (1.26-2.17) | 51 | 0.80 (0.56-1.10) | 1.01 (0.64-1.57) | 31 | 0.45 (0.30-0.65) | 1.86 (1.03-3.35) | |

Per 100,000 person-years and standardized to the 2000 U.S. standard population

More ethnic (Enclave Quintile 5); Intermediate (Enclave Quintile 4); Less ethnic (Enclave Quintile 1-3)

--Per confidentiality regulations of the California Cancer Registry, case counts and rates based on fewer than 5 cases are suppressed, and statistics are not computed.

Low SES comprises the lowest SES tertile; high SES comprises the middle and highest SES tertiles.

Bolding denotes statistical significance.

Figure 1.

Age-specific incidence rates of Hodgkin lymphoma, by gender and neighborhood ethnic enclave tertile, Hispanics, California, 1988-92/1998-02

Figure 2.

Age-specific incidence rates of Hodgkin lymphoma by neighborhood SES and ethnic enclave tertile, Hispanics, California, 1988-1992/1998-2002

Across joint enclave-SES groups (Table 2, bottom rows), female rates for HL overall were lowest in the more-ethnic/low-SES neighborhoods, 70% higher in the more-ethnic/high-SES neighborhoods (IRR: 1.70 (1.10-2.56)), and elevated to a similar degree in less-ethnic enclaves regardless of SES (IRRs: less ethnic/low SES, 1.62 (1.03-2.45); less ethnic/high SES 1.79 (1.43-2.24)). For males, rates did not differ across the joint categories, although an effect of higher SES was suggested within more-ethnic enclaves. For NS overall, rates were higher in less-ethnic/high-SES than more-ethnic/low-SES neighborhoods for both genders. For MC, the effects on rates of enclave intensity and of higher SES within more-ethnic enclaves were stronger and noted only in females.

Asians/Pacific Islanders

The overall HL incidence rate per 100,000 APIs was 1.01. Rates for less-ethnic enclaves were nearly double those of more-ethnic enclaves overall (Table 3), reflecting elevation among AYAs and older adults. Per Table 4, these patterns were stronger for females than males for all ages combined, and for AYAs and particularly older adults. This inverse association between ethnic enclave and HL incidence was more marked in low-SES than high-SES females, while detected only in high-SES males. For NS, rates similarly were higher in less-ethnic than more-ethnic neighborhoods but limited to females overall (Table 3), and suggestively among AYAs (IRRs: females, 1.39 (0.78-2.41); males, 1.00 (0.48-1.94)). For MC, the inverse association was somewhat stronger than for NS and seen among both males and females.

Table 3.

Age-adjusted incidence rates*, incidence rate ratios (IRRs), and 95% confidence intervals (CIs), of classical Hodgkin lymphoma and selected histologic subtypes, by ethnic enclave tertile, Asians/Pacific Islanders (API), California, 1988-1992/1998-2002

| Characteristics | API Enclave§ | All classical Hodgkin lymphoma | Nodular sclerosis | Mixed cellularity | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 348 | N = 218 | N = 67 | ||||||||

| N | Rate* (95% CI) | IRR (95% CI) | N | Rate* (95% CI) | IRR (95% CI) | N | Rate* (95% CI) | IRR (95% CI) | ||

| ALL COMBINED | ||||||||||

| More ethnic | 158 | 0.87 (0.73-1.02) | 1.00 (reference) | 106 | 0.55 (0.45-0.67) | 1.00 (reference) | 24 | 0.16 (0.10-0.24) | 1.00 (reference) | |

| Intermediate | 77 | 1.12 (0.87-1.42) | 1.29 (0.95-1.74) | 52 | 0.71 (0.52-0.95) | 1.30 (0.89-1.86) | 13 | 0.21 (0.11-0.37) | 1.35 (0.62-2.85) | |

| Less ethnic | 113 | 1.69 (1.37-2.05) | 1.95 (1.50-2.52) | 60 | 0.83 (0.62-1.08) | 1.51 (1.06-2.11) | 30 | 0.50 (0.33-0.73) | 3.23 (1.77-5.95) | |

| SEX | ||||||||||

| Male | More ethnic | 95 | 1.11 (0.89-1.37) | 1.00 (reference) | 54 | 0.59 (0.44-0.78) | 1.00 (reference) | 17 | 0.22 (0.13-0.36) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Intermediate | 47 | 1.57 (1.13-2.14) | 1.42 (0.95-2.08) | 25 | 0.76 (0.47-1.16) | 1.28 (0.73-2.17) | 12 | 0.44 (0.22-0.78) | 1.95 (0.82-4.45) | |

| Less ethnic | 49 | 1.59 (1.15-2.14) | 1.43 (0.97-2.09) | 23 | 0.68 (0.41-1.05) | 1.15 (0.64-1.97) | 18 | 0.62 (0.35-1.00) | 2.75 (1.28-5.85) | |

| Female | More ethnic | 63 | 0.65 (0.50-0.84) | 1.00 (reference) | 52 | 0.52 (0.39-0.68) | 1.00 (reference) | 7 | 0.09 (0.04-0.20) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Intermediate | 30 | 0.75 (0.49-1.10) | 1.14 (0.70-1.84) | 27 | 0.68 (0.43-1.01) | 1.30 (0.77-2.17) | -- | -- | -- | |

| Less ethnic | 64 | 1.80 (1.37-2.33) | 2.75 (1.88-4.02) | 37 | 0.97 (0.68-1.36) | 1.88 (1.18-2.96) | 12 | 0.41 (0.21-0.73) | 4.42 (1.55-14.06) | |

| AGE GROUP AT DIAGNOSIS | ||||||||||

| 00-14 years | More ethnic | 11 | 0.29 (0.15-0.52) | 1.00 (reference) | 8 | 0.21 (0.09-0.42) | 1.00 (reference) | -- | -- | -- |

| Intermediate | 10 | 0.68 (0.33-1.25) | 2.32 (0.88-6.00) | 9 | 0.61 (0.28-1.16) | 2.86 (0.98-8.52) | -- | -- | -- | |

| Less ethnic | 5 | 0.33 (0.11-0.76) | 1.11 (0.30-3.48) | 5 | 0.33 (0.11-0.76) | 1.53 (0.40-5.31) | -- | -- | -- | |

| 15-39 years | More ethnic | 93 | 1.22 (0.98-1.49) | 1.00 (reference) | 73 | 0.96 (0.75-1.21) | 1.00 (reference) | 7 | 0.09 (0.04-0.19) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Intermediate | 42 | 1.35 (0.97-1.83) | 1.11 (0.75-1.62) | 33 | 1.07 (0.73-1.50) | 1.11 (0.71-1.70) | 3 | 0.10 (0.02-0.28) | 1.08 (0.18-4.77) | |

| Less ethnic | 54 | 1.76 (1.32-2.30) | 1.45 (1.01-2.05) | 35 | 1.15 (0.80-1.60) | 1.20 (0.78-1.82) | 11 | 0.35 (0.17-0.62) | 3.90 (1.37-11.92) | |

| 40-54 years | More ethnic | 21 | 0.60 (0.37-0.92) | 1.00 (reference) | 13 | 0.38 (0.20-0.64) | 1.00 (reference) | -- | -- | -- |

| Intermediate | 8 | 0.55 (0.24-1.09) | 0.91 (0.35-2.15) | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| Less ethnic | 16 | 1.03 (0.59-1.68) | 1.71 (0.83-3.44) | 9 | 0.57 (0.26-1.08) | 1.51 (0.57-3.84) | -- | -- | -- | |

| 55+ years | More ethnic | 33 | 1.13 (0.77-1.61) | 1.00 (reference) | 12 | 0.38 (0.19-0.68) | 1.00 (reference) | 12 | 0.44 (0.22-0.78) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Intermediate | 17 | 1.75 (0.99-2.86) | 1.55 (0.79-2.93) | 6 | 0.67 (0.22-1.51) | 1.77 (0.49-5.25) | 6 | 0.55 (0.20-1.24) | 1.25 (0.38-3.78) | |

| Less ethnic | 38 | 3.60 (2.51-5.01) | 3.19 (1.91-5.34) | 11 | 1.05 (0.50-1.93) | 2.78 (1.05-7.06) | 17 | 1.65 (0.94-2.67) | 3.75 (1.64-8.88) | |

| NEIGHBORHOOD SES | ||||||||||

| Low | More ethnic | 38 | 0.88 (0.62-1.21) | 1.00 (reference) | 19 | 0.42 (0.25-0.66) | 1.00 (reference) | 9 | 0.21 (0.09-0.39) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Intermediate | 15 | 0.99 (0.55-1.66) | 1.13 (0.57-2.14) | 11 | 0.66 (0.33-1.21) | 1.58 (0.67-3.59) | -- | -- | -- | |

| Less ethnic | 26 | 1.53 (0.98-2.26) | 1.74 (1.00-2.97) | 11 | 0.59 (0.28-1.08) | 1.41 (0.58-3.20) | 9 | 0.60 (0.27-1.13) | 2.90 (0.99-8.27) | |

| High | More ethnic | 120 | 0.86 (0.70-1.03) | 1.00 (reference) | 87 | 0.59 (0.47-0.74) | 1.00 (reference) | 15 | 0.14 (0.07-0.24) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Intermediate | 62 | 1.19 (0.89-1.56) | 1.39 (0.98-1.95) | 41 | 0.75 (0.52-1.06) | 1.27 (0.82-1.91) | 11 | 0.24 (0.12-0.44) | 1.74 (0.70-4.30) | |

| Less ethnic | 87 | 1.72 (1.36-2.16) | 2.02 (1.48-2.73) | 49 | 0.90 (0.65-1.21) | 1.51 (1.02-2.20) | 21 | 0.46 (0.27-0.72) | 3.29 (1.54-7.34) | |

| ENCLAVE*SES‡ | ||||||||||

| More Ethnic/Low SES | 38 | 0.88 (0.62-1.21) | 1.00 (reference) | 19 | 0.42 (0.25-0.66) | 1.00 (reference) | 9 | 0.21 (0.09-0.39) | 1.00 (reference) | |

| More Ethnic/High SES | 120 | 0.86 (0.70-1.03) | 0.97 (0.67-1.46) | 87 | 0.59 (0.47-0.74) | 1.42 (0.85-2.51) | 15 | 0.14 (0.07-0.24) | 0.68 (0.26-1.79) | |

| Intermediate/Low SES | 15 | 0.99 (0.55-1.66) | 1.13 (0.57-2.14) | 11 | 0.66 (0.33-1.21) | 1.58 (0.67-3.59) | -- | -- | -- | |

| Intermediate/High SES | 62 | 1.19 (0.89-1.56) | 1.36 (0.87-2.13) | 41 | 0.75 (0.52-1.06) | 1.80 (0.99-3.37) | 11 | 0.24 (0.12-0.44) | 1.17 (0.43-3.27) | |

| Less Ethnic/Low SES | 26 | 1.53 (0.98-2.26) | 1.74 (1.00-2.97) | 11 | 0.59 (0.28-1.08) | 1.41 (0.58-3.20) | 9 | 0.60 (0.27-1.13) | 2.90 (0.99-8.27) | |

| Less Ethnic/High SES | 87 | 1.72 (1.36-2.16) | 1.96 (1.31-3.00) | 49 | 0.90 (0.65-1.21) | 2.14 (1.22-3.93) | 21 | 0.46 (0.27-0.72) | 2.22 (0.94-5.64) | |

Per 100,000 person-years and standardized to the 2000 U.S. standard population

More ethnic (Enclave Quintile 5); Intermediate (Enclave Quintile 4); Less ethnic (Enclave Quintile 1-3)

--Per confidentiality regulations of the California Cancer Registry, case counts and rates based on fewer than 5 cases are suppressed, and statistics are not computed.

Low SES comprises the lowest SES tertile; high SES comprises the middle and highest SES tertiles.

Bolding denotes statistical significance.

Table 4.

Age-adjusted incidence rates* of classical Hodgkin lymphoma, incidence rate ratios (IRRs), and 95% confidence intervals (CIs), by ethnic enclave tertile and gender, Asians/Pacific Islanders, California, 1988-1992/1998-2002

| Characteristics | API Enclave§ | All classical Hodgkin lymphoma | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males | Females | ||||||

| N = 191 | N = 157 | ||||||

| N | Rate* (95% CI) | IRR (95% CI) | N | Rate* (95% CI) | IRR (95% CI) | ||

| ALL COMBINED | |||||||

| More ethnic | 95 | 1.11 (0.89-1.37) | 1.00 (reference) | 63 | 0.65 (0.50-0.84) | 1.00 (reference) | |

| Intermediate | 47 | 1.57 (1.13-2.14) | 1.42 (0.95-2.08) | 30 | 0.75 (0.49-1.10) | 1.14 (0.70-1.84) | |

| Less ethnic | 49 | 1.59 (1.15-2.14) | 1.43 (0.97-2.09) | 64 | 1.80 (1.37-2.33) | 2.75 (1.88-4.02) | |

| AGE GROUP AT DIAGNOSIS | |||||||

| 00-14 years | More ethnic | 6 | 0.31 (0.11-0.67) | 1.00 (reference) | 5 | 0.27 (0.09-0.64) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Intermediate | 7 | 0.92 (0.37-1.88) | 2.96 (0.85-10.65) | -- | -- | -- | |

| Less ethnic | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| 15-39 years | More ethnic | 50 | 1.30 (0.97-1.72) | 1.00 (reference) | 43 | 1.13 (0.82-1.53) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Intermediate | 20 | 1.36 (0.83-2.10) | 1.04 (0.59-1.78) | 22 | 1.36 (0.85-2.06) | 1.20 (0.68-2.06) | |

| Less ethnic | 22 | 1.49 (0.93-2.25) | 1.14 (0.66-1.92) | 32 | 2.06 (1.40-2.91) | 1.82 (1.11-2.95) | |

| 40-54 years | More ethnic | 16 | 0.97 (0.55-1.57) | 1.00 (reference) | 5 | 0.27 (0.09-0.64) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Intermediate | 5 | 0.75 (0.24-1.75) | 0.77 (0.22-2.21) | -- | -- | -- | |

| Less ethnic | 8 | 1.15 (0.50-2.27) | 1.19 (0.44-2.95) | 8 | 0.94 (0.40-1.85) | 3.42 (0.99-13.32) | |

| 55+ years | More ethnic | 23 | 1.74 (1.09-2.65) | 1.00 (reference) | 10 | 0.63 (0.29-1.19) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Intermediate | 15 | 3.43 (1.87-5.80) | 1.98 (0.93-4.06) | -- | -- | -- | |

| Less ethnic | 17 | 3.55 (2.02-5.80) | 2.05 (1.00-4.10) | 21 | 3.66 (2.22-5.70) | 5.81 (2.53-14.30) | |

| NEIGHBORHOOD SES‡ | |||||||

| Low | More ethnic | 31 | 1.55 (1.05-2.22) | 1.00 (reference) | 7 | 0.29 (0.12-0.60) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Intermediate | 7 | 0.99 (0.38-2.10) | 0.64 (0.23-1.52) | 8 | 0.99 (0.42-1.98) | 3.42 (1.06-11.26) | |

| Less ethnic | 12 | 1.54 (0.77-2.74) | 0.99 (0.45-2.03) | 14 | 1.51 (0.81-2.57) | 5.24 (1.93-15.47) | |

| High | More ethnic | 64 | 0.94 (0.72-1.22) | 1.00 (reference) | 56 | 0.77 (0.58-1.02) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Intermediate | 40 | 1.78 (1.23-2.50) | 1.89 (1.19-2.94) | 22 | 0.71 (0.43-1.12) | 0.92 (0.51-1.60) | |

| Less ethnic | 37 | 1.56 (1.08-2.20) | 1.65 (1.04-2.58) | 50 | 1.89 (1.37-2.54) | 2.45 (1.60-3.74) | |

| ENCLAVE*SES‡ | |||||||

| More Ethnic/Low SES | 31 | 1.55 (1.05-2.22) | 1.00 (reference) | 7 | 0.29 (0.12-0.60) | 1.00 (reference) | |

| More Ethnic/High SES | 64 | 0.94 (0.72-1.22) | 0.61 (0.39-0.98) | 56 | 0.77 (0.58-1.02) | 2.67 (1.19-7.00) | |

| Intermediate/Low SES | 7 | 0.99 (0.38-2.10) | 0.64 (0.23-1.52) | 8 | 0.99 (0.42-1.98) | 3.42 (1.06-11.26) | |

| Intermediate/High SES | 40 | 1.78 (1.23-2.50) | 1.15 (0.68-1.95) | 22 | 0.71 (0.43-1.12) | 2.47 (0.98-7.00) | |

| Less Ethnic/Low SES | 12 | 1.54 (0.77-2.74) | 0.99 (0.45-2.03) | 14 | 1.51 (0.81-2.57) | 5.24 (1.93-15.47) | |

| Less Ethnic/High SES | 37 | 1.56 (1.08-2.20) | 1.01 (0.59-1.71) | 50 | 1.89 (1.37-2.54) | 6.55 (2.89-17.25) | |

Per 100,000 person-year and standardized to the 2000 U.S. standard population

More ethnic (Enclave Quintile 5); Intermediate (Enclave Quintile 4); Less ethnic (Enclave Quintile 1-3)

Per confidentiality requirements of the California Cancer Registry, case counts based on fewer than 4 cases are suppressed, and statistics are not computed

Low SES comprises the lowest SES tertile; high SES comprises the middle and highest SES tertiles.

Bolding denotes statistical significance.

The joint effect of enclave and SES on overall HL rates in APIs differed notably by gender. For females, rates were lowest in more-ethnic/low-SES neighborhoods and five- to six-fold higher with lessening enclave intensity, with a limited additional effect of SES. For males, the only rate differences occurred within more-ethnic neighborhoods, with higher SES linked to lower HL rates. For both NS and MC, rates were higher for less-ethnic than more-ethnic enclaves (Table 3); the data did not support gender-specific rates for these subtypes.

DISCUSSION

This first study of HL incidence and neighborhood ethnic enclave level, a measure of acculturation, in California Hispanics and APIs found that rates were higher in less-ethnic than more-ethnic enclaves in both populations. This inverse association was stronger in females than males, present in both young and older adults, and more marked in low-SES settings in females. Rates in females were highest in less-ethnic/high-SES neighborhoods, and diminishing ethnic enclave intensity appeared to affect rates more than higher SES. However, the effect of enclave on rates also differed by race/ethnicity. In Hispanics, the association of lesser enclave with higher HL rates was modest, modification by SES was limited to females, and the impact of SES within more-ethnic enclaves was of similar magnitude to that for the overall effect of less-ethnic vs. more-ethnic enclaves. In APIs, the effect of lesser enclave intensity on rates was stronger, particularly marked for MC, seen in males of higher SES, and in females progressively higher with lessening enclave intensity and increasing SES. Together, these findings suggest that acculturation as indicated by neighborhood ethnic enclave status affects HL rates independently of neighborhood SES, but in complex and race/ethnicity-varying patterns characteristic of classical HL incidence [27,38].

Our findings are consistent with prior research showing that residing in an ethnic enclave is related to risk of disease [16,19], including several cancers [13,20-26]. The direction of our observed associations was anticipated based on our previous findings regarding HL incidence by nativity [13,14], which is one component of our neighborhood enclave index. The single prior study addressing HL incidence and ethnic enclave residence, based on 220 API cases also included in the present analyses, similarly found elevated rates for females in less-ethnic and higher-SES neighborhoods [13].

Ethnic enclaves have been interpreted to affect health and disease risk through a broad range of community-level influences, including economic opportunity, social networks, health care access, diet, physical activity, reproductive behaviors, etc. [15,16,19,39-43]. Given established risk factors for HL, the observed association with ethnic enclave residence likely relates to relevant social community characteristics (e.g., education, family size [8], SES [4-6], household crowding [44]) and/or other environmental influences (e.g., smoking [45]). Indeed, in California populations, enclave levels showed strong inverse correlations among Hispanics with both neighborhood SES (percentages of block groups in the lowest and highest SES quintiles among more-ethnic enclaves = 66.8% and 0.0%, and among less-ethnic neighborhoods = 3.9% and 32.6%, respectively) and population density (percentages of block groups in the highest and lowest population density quintiles among more-ethnic enclaves = 52.2% and 7.9%, and among less-ethnic neighborhoods = 8.7% and 24.7%, respectively), but only very slight associations among Asians (data not shown). Nevertheless, our observation of enclave associations with HL that are present over and above some modifications by SES, together with the suggestion that residence in lesser-ethnic enclaves was more strongly associated with elevated HL rates than higher SES, support SES-independent mechanisms by which acculturation also may affect incidence. Some mechanisms are suggested by our subgroup findings. In Hispanic women, the absence of an enclave association in high-SES neighborhoods suggests that features of more-ethnic enclaves that protect against HL may be superseded in high-SES environments by other factors related to HL risk [8,44]. For AYAs, in whom HL development is associated with early social isolation [8,44], the elevated HL rates in less-ethnic enclaves irrespective of SES suggest that more concurrent aspects of acculturation may override SES-based risks set during childhood. The higher HL rates in more-ethnic/high-SES than more-ethnic/low-SES Hispanic enclaves suggest a prevailing effect of risk established by high childhood SES.

The persistently stronger impact among women than men of living in lesser ethnic enclaves recalls gender differences in HL incidence by neighborhood SES [5] and nativity [13]. These differences may reflect women's reproductive experience together with exposures to small children, which may influence HL risk [46] and vary across ethnic enclaves [47]. Thus, for Hispanic women, the relatively high fertility among immigrants [43] could provide protection against HL, leading to the observed lower rates for women in more-ethnic enclaves. The stronger association of HL incidence with less-ethnic enclaves for API than Hispanic women also is consistent with this hypothesis, as in California, Asian women are less parous than Hispanics, irrespective of birthplace (≥3 children born to 41% of foreign-born and 17% of US-born Hispanic AYA women vs. 10% of foreign-born and 4% of US-born AYA Asian women [48]). Moreover, while API women living in less-ethnic enclaves had higher HL rates regardless of SES, the association was stronger in low-SES neighborhoods, a pattern similar to that among Hispanic women. However, among API men, the impact of lesser enclave was observed only in high-SES neighborhoods, which may reflect male-female variation in social behavior and community involvement [49]; males may be less influenced by community factors, as might result from more time spent in employment out of the residential neighborhood. For HL in high-SES males, these circumstances may combine to favor social isolation that increases risk.

The common findings for Hispanics and APIs suggest consistency in the effects of acculturation and related aspects of the social environment on HL incidence, at least under conditions common to these study populations. In 2001, California Hispanics and Asians both comprised large proportions of recent immigrants (46% of Hispanics and 66% of Asians were foreign-born; approximately one-third of both groups had resided in the US for fewer than 10 years) [48]. These populations had achieved similar levels of some acculturation indicators (55% of Hispanics and 50% of Asians spoke English and one other language [48]). On the other hand, differences between the two study populations in study findings may relate to other sociodemographic differences. Hispanics reported less education and more poverty than APIs among both the foreign-born (84% vs. 34% completing high school or less; 42% vs. 16% living at or below the federal poverty level), and the US-born (57% vs. 29% completing high school or less; 28% vs. 9% living at or below the federal poverty level) [48]. Hispanics also had evidence of being less acculturated than Asians (e.g., 49% vs. 27% reporting not speaking English well [48]). Thus, the stronger effects of acculturation among APIs (and, for API females, irrespective of SES) we noted may imply that acculturation has more of an effect on HL development in populations lacking the prior protections against HL correlated with lower SES (e.g., larger family size in childhood [44,50] and, in females, more exposure to children in childhood and adulthood [46]). However, Hispanics and APIs also have well-described and persistent HL incidence rate variation [3-5], suggesting that other underlying differences may come into play with enclave associations.

Nativity likely influences our findings [13,14]. The lack of census-tract-level population data by nativity precluded our incorporating nativity into this analysis. Nevertheless, the decreasing percentages across enclaves of Hispanic HL cases who were foreign-born (more-ethnic (41%), intermediate (35%), less-ethnic (28%)) are consistent with a contribution of US birthplace to the higher HL rates in less-ethnic enclaves. The smaller proportion of foreign-born Hispanics in more-ethnic enclaves of low SES (45%) than high SES (59%) might predict higher HL rates for more-ethnic/low-SES neighborhoods. However, our findings show the opposite, perhaps because foreign-born Hispanics in more-ethnic/high-SES neighborhoods may have experienced childhood social isolation prior to immigration, thereby increasing HL risk. Among APIs, nativity seems less likely to affect our findings, as the percentage foreign-born varied less across more-ethnic, intermediate, and less-ethnic enclaves (62%, 53%, and 58%, respectively) than in Hispanic HL cases.

As immigration patterns, existence of ethnic enclaves, and acculturation processes change over time, the impact of ethnic enclave residence on HL incidence rates may evolve. The smaller proportions of foreign-born Hispanics (39%) and APIs (59%) in California in 2011-12 than 2001, and higher education levels in both groups (high school or less completed by 76% and 28% of the foreign-born, and 48% and 24% of the US-born), would predict higher HL rates in both groups going forward [48]. However, persistent socioeconomic disparities between Hispanics and APIs suggest that racial/ethnic differences in HL rates will continue.

Our study is subject to some limitations. Our enclave index did not capture all aspects of acculturation, may not have included those most influential for HL etiology, and cannot account for the effect of duration in an enclave [15]. The index reflects residence at HL diagnosis, and some etiologically exposures occur long before diagnosis [8,36]; however, other HL risk factors occur closer to disease onset [51], and some tumor promoters could act late in the carcinogenic process. Without individual-level information, we could not partition the respective effects of individual- and neighborhood-level acculturation and SES on HL incidence [16,47]. We lacked information on tumor Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) status, which defines etiologically distinct forms of HL [52] and modifies risk related to both nativity and SES [14,53]. While the more pronounced findings in females and in young adults are consistent with a stronger effect in EBV-negative HL, the somewhat larger IRRs for MC HL (mostly EBV-positive [53,54]) than NS HL (mostly EBV-negative [53,54]) suggest the opposite. The numbers of HL cases were sparse in some strata. Small sample sizes mandated calculating rates for all APIs combined, limiting the precision of our findings across Asian ethnic groups [55]. The numerous associations tested may have yielded some statistically significant associations by chance.

Nevertheless, our study offers the strength of a broad evaluation of the effect of ethnic enclave residence on HL rates by including two racial/ethnic groups with differing HL incidence and sociodemographic characteristics. Our large case series allowed us to address HL heterogeneity by calculating HL enclave-specific rates simultaneously by age group, gender, and selected histologic subtype separately for Hispanics and APIs; the larger group of APIs cases assembled here permitted more detailed, stratified enclave rates for this race group than were possible previously [13]. The high-quality population-based data of our data source [56] ensured reliable conclusions generalizable to similar populations, relative ethnic homogeneity of the Hispanic population for more precise study findings [57], and race/ethnicity and nativity enhanced [30,31,58] to reduce misclassification [59]. Our ethnic enclave indices, based on race/ethnicity-specific measures, captured acculturation appropriate to the study populations [16].

Conclusion

In two California racial/ethnic populations with large proportions of recent immigrants, HL rates varied by ethnic enclave, a neighborhood measure of acculturation. The higher HL rates in less-ethnic neighborhoods support an influence on HL risk of community-level sociodemographic characteristics that change following immigration and acculturation to a westernized lifestyle. Limited rate modification by SES, and elevation of rates in less-ethnic/high-SES compared to more-ethnic/low-SES neighborhoods, suggest that acculturation affects HL incidence independently of neighborhood SES. Less-ethnic and/or high-SES neighborhoods may increase HL risk by facilitating protected social interactions, especially early in life, that are associated with increases in HL risk. The stronger impact of acculturation on HL rates for females than males is consistent with a role of reproductive experience and exposures to young children on HL occurrence, and/or with gender differences in social and behavioral interactions with enclave environments. Differences in findings between Hispanics and APIs may reflect differing socioeconomic, demographic, and cultural profiles of immigrants in these groups, and changes in these profiles over time may alter acculturation-based variation in HL rates. Nevertheless, the results of this ecologic study justify further investigation of genetic, hormonal, and behavioral factors, that interact with environmental influences associated with HL occurrence in groups defined by patient race/ethnicity and tumor EBV tumor-cell status. Although such studies require large samples with sufficient racial/ethnic diversity, they might be contemplated in data pooled across extant case-control and cohort studies within the International Lymphoma Epidemiology Consortium (InterLymph) [45].

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS AND DECLARATION OF INTEREST

We thank Kristine Winters and Meg McKinley for their help with this study. The collection of cancer incidence data used in this study was supported by the California Department of Health Services as part of the statewide cancer-reporting program mandated by California Health and Safety Code, Section 103885; by the National Cancer Institute's Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program under contracts N01-PC-35136 awarded to the Cancer Prevention Institute of California, N02-PC-15105 awarded to the Public Health Institute, HHSN261201000140C awarded to the Cancer Prevention Institute of California, HHSN261201000035C awarded to the University of Southern California, and HHSN261201000034C awarded to the Public Health Institute; and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's National Program of Cancer Registries, under agreements U55/CCR921930-02 awarded to the Public Health Institute and U58DP003862-01 awarded to the California Department of Public Health. The ideas and opinions expressed herein are those of the authors, and endorsement by the State of California Department of Public Health, the National Cancer Institute, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or their contractors and subcontractors is not intended nor should be inferred.

Ellen T. Chang is employed by Exponent, Inc., a for-profit corporation that provides engineering and scientific consulting services to private and government organizations. As part of her employment for Exponent, Dr. Chang has been a consultant on the epidemiology of HL.

REFERENCES

- 1.Morton LM, Wang SS, Devesa SS, Hartge P, Weisenburger DD, Linet MS. Lymphoma incidence patterns by WHO subtype in the United States, 1992-2001. Blood. 2006;107:265–276. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-06-2508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hjalgrim H, Seow A, Rostgaard K, Friborg J. Changing patterns of Hodgkin lymphoma incidence in Singapore. Int J Cancer. 2008;123:716–719. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Evens AM, Antillón M, Aschebrook-Kilfoy B, Chiu BC-H. Racial disparities in Hodgkin's lymphoma: a comprehensive population-based analysis. Annals of Oncology. 2012;23:2128–2137. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cozen W, Katz J, Mack TM. Risk patterns of Hodgkin's disease in Los Angeles vary by cell type. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1992;1:261–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clarke CA, Glaser SL, Keegan THM, Stroup A. Neighborhood socioeconomic status and Hodgkin lymphoma incidence in California. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:1441–1447. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boscoe FP, Johnson CJ, Sherman RL, Stinchcomb DG, Lin G, Henry KA. The relationship between area poverty rate and site-specific cancer incidence in the United States. Cancer. 2014;120:2191–2198. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Glaser SL, Clarke CA, Nugent RA, Stearns CB, Dorfman RF. Social class and risk of Hodgkin's disease in young-adult women in 1988-94. Int J Cancer. 2002;98:110–117. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang ET, Zheng T, Weir EG, et al. Childhood social environment and Hodgkin's lymphoma: new findings from a population-based case-control study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2004;13:1361–1370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hjalgrim H, Smedby KE, Rostgaard K, et al. Infectious mononucleosis, childhood social environment, and risk of Hodgkin lymphoma. Cancer Res. 2007;67:2382–2388. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crump C, Sundquist K, Sieh W, Winkleby MA, Sundquist J. Perinatal and family risk factors for Hodgkin lymphoma in childhood through young adulthood. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;176:1147–1158. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Glaser SL, Hsu JL. Hodgkin's disease in Asians: incidence patterns and risk factors in population-based data. Leuk Res. 2002;26:261–269. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2126(01)00126-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Au WY, Gascoyne RD, Gallagher RE, et al. Hodgkin's lymphoma in Chinese migrants to British Columbia: a 25-year survey. Ann Oncol. 2004;15:626–630. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdh132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clarke CA, Glaser SL, Gomez SL, et al. Lymphoid malignancies in U.S. Asians: incidence rate differences by birthplace and acculturation. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20:1064–1077. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Glaser SL, Clarke CA, Chang ET, Yang J, Gomez SL, Keegan TH. Hodgkin lymphoma incidence in California Hispanics: Influence of nativity and tumor Epstein–Barr virus. Cancer Causes Control. 2014;25:709–725. doi: 10.1007/s10552-014-0374-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Edin P-A, Fredriksson P, Aslund O. Ethnic enclaves and the economic success of immigrants--evidence from a natural experiment. Quarterly Journal Economics. 2003;118:329–357. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Osypuk TL, Diez Roux AV, Hadley C, Kandula NR. Are immigrant enclaves healthy places to live? The Multi-ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Social Science & Medicine. 2009;69:110–120. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cantrell J. A multilevel analysis of gender, Latino immigrant enclaves, and tobacco use behavior. J Urban Health. 2014:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s11524-014-9881-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roy A, Hughes D, Yoshikawa H. Intersections between nativity, ethnic density, and neighborhood SES: Using an ethnic enclave framework to explore variation in Puerto Ricans’ physical health. Amer J Comm Psychol. 2013;51:468–479. doi: 10.1007/s10464-012-9564-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Epstein D, Reibel M, Unger J, et al. The effect of neighborhood and individual characteristics on pediatric critical illness. J Comm Health. 2014;39:753–759. doi: 10.1007/s10900-014-9823-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keegan TH, John EM, Fish KM, Alfaro-Velcamp T, Clarke CA, Gomez SL. Breast cancer incidence patterns among California Hispanic women: differences by nativity and residence in an enclave. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19:1208–1218. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chang ET, Yang J, Alfaro-Velcamp T, So SK, Glaser SL, Gomez SL. Disparities in liver cancer incidence by nativity, acculturation, and socioeconomic status in California Hispanics and Asians. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19:3106–3118. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ladabaum U, Clarke CA, Press DJ, et al. Colorectal cancer incidence in Asian Populations in California: Effect of nativity and neighborhood-level factors. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:579–588. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chang ET, Gomez SL, Fish K, et al. Gastric cancer incidence among Hispanics in California: Patterns by time, nativity, and neighborhood characteristics. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012;21:709–719. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-1208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Froment M-A, Gomez SL, Roux A, DeRouen MC, Kidd EA. Impact of socioeconomic status and ethnic enclave on cervical cancer incidence among Hispanics and Asians in California. Gynecologic Oncology. 2014;133:409–415. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2014.03.559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schupp CW, Press DJ, Gomez SL. Immigration factors and prostate cancer survival among Hispanic men in California: Does neighborhood matter? Cancer. 2014;120:1401–1408. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Horn-Ross PL, Lichtensztajn DY, Clarke CA, et al. Continued rapid increase in thyroid cancer incidence in California: Trends by patient, tumor, and neighborhood characteristics. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2014;23:1067–1079. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-13-1089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Glaser SL, Chang ET, Clarke CA, Keegan TH. Epidemiology. In: Engert A, Younes A, editors. Hodgkin Lymphoma, A comprehensive overview. 2nd ed Springer; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 28. [2013 October 14];Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Website. About SEER. List of SEER Registries. 2013 Oct 14; < http://seer.cancer.gov/registries/list.html>.

- 29.Gomez SL, Quach T, Horn-Ross PL, et al. Hidden breast cancer disparities in Asian women: disaggregating incidence rates by ethnicity and migrant status. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(Suppl 1):S125–131. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.163931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.NAACCR Latino Research Work Group . NAACCR guideline for enhancing Hispanic-Latino identification: revised NAACCR Hispanic/Latino identification algorithm [NHIA v2] North American Association of Central Cancer Registries; Springfield, IL: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 31.NAACCR Asian/Pacific Islander Work Group . NAACCR Asian/Pacific Islander identification algorithm [NAPIIAv1.1] North American Association of Central Cancer Registries (NAACCR); Springfield, IL: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Glaser SL, Clarke CA, Gulley ML, et al. Population-based patterns of human immunodeficiency virus-related Hodgkin lymphoma in the Greater San Francisco Bay Area, 1988-1998. Cancer. 2003;98:300–309. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Clarke C, Glaser SL. Population-based surveillance of HIV-associated cancers: utility of cancer registry data. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004;36:1083–1091. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200408150-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gomez SL, Clarke CA, Shema SJ, Chang ET, Keegan TH, Glaser SL. Disparities in breast cancer survival among Asian women by ethnicity and immigrant status: a population-based study. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:861–869. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.176651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yost K, Perkins C, Cohen R, Morris C, Wright W. Socioeconomic status and breast cancer incidence in California for different race/ethnic groups. Cancer Causes Control. 2001;12:703–711. doi: 10.1023/a:1011240019516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hjalgrim H, Engels EA. Infectious aetiology of Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphomas: a review of the epidemiological evidence. J Int Medicine. 2008;264:537–548. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2008.02031.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. [2009 March 31, 2014];Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Website. SEER*Stat Software Version 8.1.5 - March 31, 2014. 2014 Mar 31; 2014 < http://seer.cancer.gov/seerstat/>.

- 38.Caporaso NE, Goldin LR, Anderson WF, Landgren O. Current insight on trends, causes, and mechanisms of Hodgkin's lymphoma. Cancer Journal. 2009;15:117–123. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0b013e3181a39585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Haas JS, Phillips KA, Sonneborn D, et al. Variation in access to health care for different racial/ethnic groups by the racial/ethnic composition of an individual's county of residence. Medical Care. 2004;42:707–714. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000129906.95881.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Larson NI, Story MT, Nelson MC. Neighborhood environments: Disparities in access to healthy foods in the U.S. Amer J Prev Med. 2009;36:74–81. e10. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cagney KA, Browning CR, Wallace DM. The Latino paradox in neighborhood context: the case of asthma and other respiratory conditions. Amer J Pub Health. 2007;97:919–925. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.071472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xie Y, Gough M. Ethnic enclaves and the earnings of immigrants. Demography. 2011;48:1293–1315. doi: 10.1007/s13524-011-0058-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lichter DT, Johnson KM, Turner RN, Churilla A. Hispanic assimilation and fertility in new U.S. destinations. International Migration Review. 2012;46:767–791. doi: 10.1111/imre.12000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gutensohn (Mueller) N, Cole P. Childhood social environment and Hodgkin's disease. New Engl J Med. 1981;304:135–140. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198101153040302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kamper-Jorgensen M, Rostgaard K, Glaser SL, et al. Cigarette smoking and risk of Hodgkin lymphoma and its subtypes: a pooled analysis from the International Lymphoma Epidemiology Consortium (InterLymph). Ann Oncol. 2013;24:2245–2255. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Glaser SL, Clarke CA, Nugent RA, Stearns CB, Dorfman RF. Reproductive risk factors in Hodgkin's disease in women. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;158:553–563. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Osypuk TL, Bates LM, Acevedo-Garcia D. Another Mexican birthweight paradox? The role of residential enclaves and neighborhood poverty in the birthweight of Mexican- origin infants. Social Science & Medicine. 2010;70:550–560. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.10.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.California Health Interview Survey (CHIS) [Internet] UCLA Center for Health Policy Research; Los Angeles, CA: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Eagly AH, Wood W. Explaining sex differences in social behavior: A meta-analytic perspective. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 1991;17:306–315. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chang ET, Montgomery SM, Richiardi L, Ehlin A, Ekbom A, Lambe M. Number of siblings and risk of Hodgkin's lymphoma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2004;13:1236–1243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hjalgrim H, Askling J, Rostgaard K, et al. Characteristics of Hodgkin's lymphoma after infectious mononucleosis. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1324–1332. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa023141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chang ET, Zheng T, Lennette ET, et al. Heterogeneity of risk factors and antibody profiles in Epstein-Barr virus genome-positive and -negative Hodgkin lymphoma. J Infect Dis. 2004;189:2271–2281. doi: 10.1086/420886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Glaser SL, Gulley ML, Clarke CA, et al. Racial/ethnic variation in EBV-positive classical Hodgkin lymphoma in California populations. Int J Cancer. 2008;123:1499–1507. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Glaser SL, Lin RJ, Stewart SL, et al. Epstein-Barr virus-associated Hodgkin's disease: epidemiologic characteristics in international data. Int J Cancer. 1997;70:375–382. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19970207)70:4<375::aid-ijc1>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Carreon D, Morton L, Devesa S, et al. Incidence of lymphoid neoplasms by subtype among six Asian ethnic groups in the United States, 1996–2004. Cancer Causes Control. 2008;19:1171–1181. doi: 10.1007/s10552-008-9184-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gomez SL, Glaser SL, McClure LA, et al. The California Neighborhoods Data System: a new resource for examining the impact of neighborhood characteristics on cancer incidence and outcomes in populations. Cancer Causes Control. 2011;22:631–647. doi: 10.1007/s10552-011-9736-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Klitz W, Gragert L, Maiers M, et al. Four-locus high-resolution HLA typing in a sample of Mexican Americans. Tissue Antigens. 2009;74:508–513. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.2009.01374.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Raz DJ, Gomez SL, Chang ET, et al. Epidemiology of non-small cell lung cancer in Asian Americans: Incidence patterns among six subgroups by nativity. J Thoracic Oncol. 2008;3:1391–1397. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31818ddff7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gomez SL, Glaser SL. Misclassification of race/ethnicity in a population-based cancer registry (United States). Cancer Causes Control. 2006;17:771–781. doi: 10.1007/s10552-006-0013-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]