Abstract

Background

The aim of this study was to reveal the association between airflow limitation (AL) severity and reduction with work productivity as well as use of sick leave among Japanese workers.

Methods

This cross-sectional study included 1,378 workers who underwent a lung function test during a health checkup at the Japanese Red Cross Kumamoto Health Care Center. AL was defined as forced expiratory volume in 1 second/forced vital capacity of <0.7. Workers completed a questionnaire on productivity loss at work and sick leave. The quality and quantity of productivity loss at work were measured on a ten-point scale indicating how much work was actually performed on the previous workday. Participants were asked how many days in the past 12 months they were unable to work because of health problems. Logistic regression analysis was used to assess the associations between AL severity and the quality and quantity of productivity loss at work as well as use of sick leave.

Results

Compared with workers without AL, workers with moderate-to-severe AL showed a significant productivity loss (quality: odds ratio [OR] =2.04, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.12–3.71, P=0.02 and quantity: OR =2.19, 95% CI: 1.20–4.00, P=0.011) and use of sick leave (OR =2.69, 95% CI: 1.33–5.44, P=0.006) after adjusting for sex, age, body mass index, smoking status, hypertension, hyperglycemia, dyslipidemia, sleep duration, work hours per day, and workplace smoking environment.

Conclusion

AL severity was significantly associated with work productivity loss and use of sick leave. Our findings suggested that early intervention in the subjects with AL at the workforce might be beneficial for promoting work ability.

Keywords: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, airflow limitation, work productivity, sick leave, presenteeism, absenteeism

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide and results in an economic and social burden that is both substantial and increasing.1–3 COPD is one of the world’s most common noncommunicable health problems.2 The World Health Organization reported that COPD is the third leading cause of death in the world and is presently the fifth leading cause of death among high-income countries, with a rate of 31 deaths per 100,000 people.4 Furthermore, the burden of COPD is expected to continue increasing.4

COPD is considered to be a disease of later years; typical onset is in middle adulthood (>55 years). Estimates suggest that 50% of those with COPD are younger than 65 years of age,5,6 and many of them are likely to be under paid employment.7

COPD is a debilitating disease affecting the daily lives of patients. Physical activity levels are low even in patients in the early stages of COPD.8 Increasing severity of COPD is associated with decreasing physical activity.8,9 Although data exist on the physical activity levels of those with COPD, data on its impact on presenteeism and absenteeism among the working population are limited. Few studies have examined the association between COPD and work ability as well as use of sick leave.7,10–14 Employed adults with COPD reported significantly lower quality of life and work productivity and increased health care resource utilization than employed adults without COPD in the USA.12 Workers diagnosed with COPD had significantly higher levels of presenteeism and overall work impairment.12 Furthermore, there are no data regarding the association between airflow limitation (AL) severity and productivity at work or use of sick leave. We hypothesized that AL could be an important factor associated with loss of productivity at work and use of sick leave. This study aimed to reveal the associations between AL severity and productivity at work as well as use of sick leave among Japanese workers.

Materials and methods

Participants

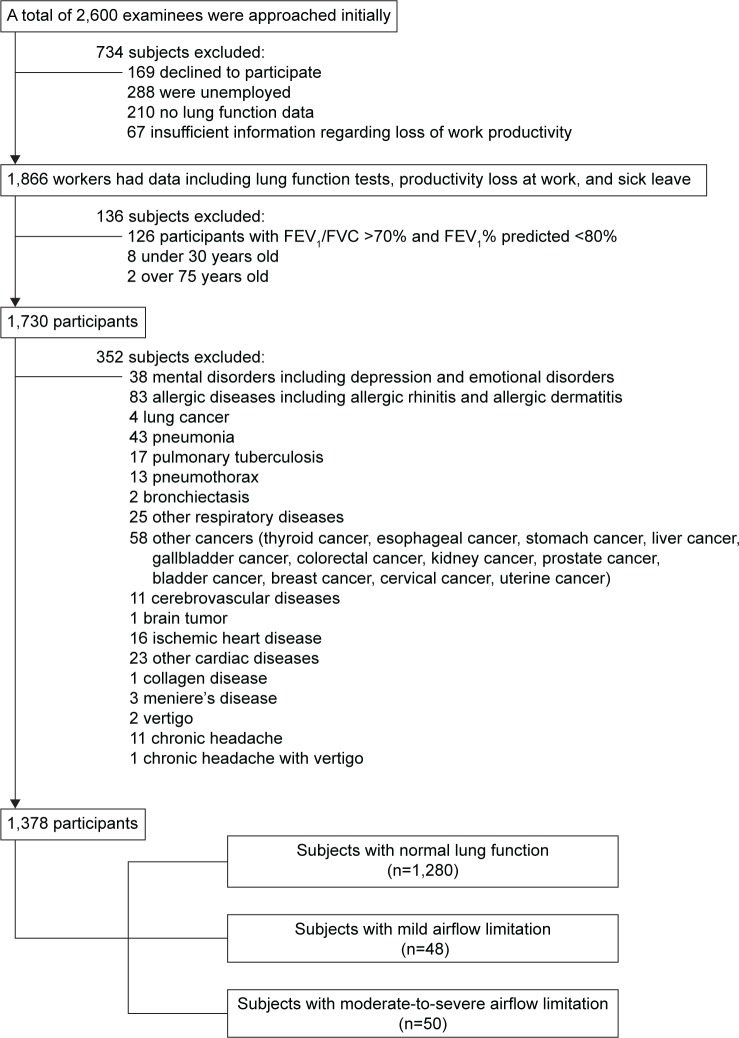

Figure 1 demonstrates the flow chart for selection of the participants with either AL or normal lung function. Participants were employees who underwent medical health checkups at the Japanese Red Cross Kumamoto Health Care Center and were selected between July 2012 and September 2013. The medical health checkups included interview questionnaires, a physical examination, blood sampling, and spirometry, as previously described.15–18

Figure 1.

Flowchart of selecting the subjects with airflow limitation or normal lung function.

Abbreviations: FEV1/FVC, forced expiratory volume in 1 second to forced vital capacity; FEV1% predicted, forced expiratory volume in 1 second as percentage of predicted.

The interview questionnaires were conducted by a trained public health nurse to obtain data regarding medical history, smoking status, sleep duration, work hours per day, workplace smoking environment, productivity loss at work, and sickness absence. History of disease included past diagnosis and current treatment. All the participants were evaluated by a physician. The nonsmokers were of those who denied any past or current smoking. The former smokers were those who reported smoking cessation before the examination. The current smokers were those who reported smoking at least one cigarette a day. Pack-years were calculated by multiplying the number of years of smoking by the average number of cigarettes smoked per day and dividing it by 20.

According to the interview questionnaires, sleep duration was categorized into <6 hours, 6–8 hours, and >8 hours. Work hours per day were categorized into ≤8 hours, 8–10 hours, and >10 hours.

Workplace smoking environment was categorized into smoke-free policies, restrictive policies (prohibitive policies using designated smoking rooms), and nonrestrictive (nonprohibitive) policies.

A total of 2,600 examinees were approached initially; 169 declined to participate. Those without jobs (n=288) were excluded, as were those without lung function data (n=210) and those for whom there was insufficient information regarding loss of work productivity (n=67). Complete data on lung function tests, productivity loss at work, and sickness absence were obtained from 1,866 workers. Additionally, participants with forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1)/forced vital capacity (FVC) >70% and FEV1 predicted <80% (n=126) were excluded from this study. We excluded data obtained from participants younger than 30 years (n=8) and older than 75 years of age (n=2). We further excluded participants with a history or clinical evidence of mental disorder, allergic disease, respiratory disease except for COPD and asthma, cancer, cerebrovascular disease, brain tumor, cardiac disease, and collagen disease. Those with Ménière’s disease, vertigo, chronic headache, and chronic headache with vertigo were also excluded. Further details are given in Figure 1. None of the subjects were diagnosed with COPD with acute exacerbation. Data from a total of 1,378 participants (921 males and 457 females) aged 30–74 years were included in the final analysis. The main occupation of the participants consisted of managers (n=105), professionals and technicians (n=375), clerks (n=545), sales (n=110), service (n=57), agriculture and fishery (n=79), manufacturing (n=57), construction (n=13), and others (n=37). None of the subjects had a history of exposure to workplace dust. Subjects were divided according to lung function (1,280 had normal lung function, 48 had mild AL, and 50 had moderate-to-severe AL) (Table 1).

Table 1.

The characteristics of the study subjects

| Characteristics | Normal lung function, n=1,280 | Mild AL, n=48 | Moderate-to-severe AL, n=50 | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||

| Male, n (%) | 836 (65.3) | 38 (79.2) | 47 (94.0) | <0.001 |

| Female, n (%) | 444 (34.7) | 10 (20.8) | 3 (6.0) | |

| Age, years | 49.3 (8.8) | 53.0 (9.5)* | 55.9 (9.7)** | <0.001 |

| Height, cm | 165.7 (8.2) | 168.0 (8.4) | 167.9 (7.7) | 0.027 |

| Weight, kg | 64.1 (11.3) | 64.4 (11.1) | 68.2 (12.4)* | 0.112 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 23.3 (3.2) | 22.7 (3.0) | 24.1 (3.2) | 0.048 |

| Smoking status | ||||

| Never, n (%) | 657 (51.3) | 16 (33.3) | 12 (24.0) | |

| Former, n (%) | 363 (28.4) | 12 (25.0) | 20 (40.0) | |

| Current, n (%) | 260 (20.3) | 20 (41.7) | 18 (36.0) | <0.001 |

| Pack-years | 10.0 (15.3) | 18.0 (24.0)* | 22.2 (26.6)** | <0.001 |

| Lung function | ||||

| FEV1, mL | 3,081.3 (631.1) | 2,885.0 (596.6) | 2,281.4 (517.0)**,## | <0.001 |

| FVC, mL | 3,861.1 (799.2) | 4,368.5 (896.8)** | 3,715.8 (829.5)## | <0.001 |

| FEV1/FVC, % | 80.1 (5.3) | 66.1 (2.4)** | 61.8 (6.9)**,## | <0.001 |

| FEV1%, predicted, % | 98.6 (11.1) | 89.1 (7.4)** | 69.4 (9.7)**,## | <0.001 |

| Clinical information | ||||

| Hypertension, n (%) | 410 (32.0) | 14 (29.2) | 23 (46.0) | 0.104 |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 566 (44.2) | 21 (43.8) | 30 (60.0) | 0.088 |

| Hyperglycemia, n (%) | 167 (13.0) | 8 (16.7) | 12 (24.0) | 0.070 |

| Sleep duration | ||||

| 6–8 h, n (%) | 1,088 (85.0) | 39 (81.2) | 42 (84.0) | |

| <6 h, n (%) | 182 (14.2) | 8 (16.7) | 5 (10.0) | |

| >8 h, n (%) | 10 (0.8) | 1 (2.1) | 3 (6.0) | 0.006 |

| Work hours per day | ||||

| ≤8 h, n (%) | 674 (52.6) | 23 (47.9) | 26 (52.0) | |

| >8≤10 h, n (%) | 440 (34.4) | 16 (33.3) | 19 (38.0) | |

| >10 h, n (%) | 166 (13.0) | 9 (18.8) | 5 (10.0) | 0.743 |

| Smoking environment at workplace, n=1,307a | n=1,216a | n=43a | n=48a | |

| Smoke-free, n (%) | 403 (33.2)a | 10 (23.3)a | 13 (27.1)a | |

| Restrictive, n (%) | 707 (58.1)a | 28 (65.1)a | 23 (47.9)a | |

| Nonrestrictive, n (%) | 106 (8.7)a | 5 (11.6)a | 12 (25.0)a | 0.010 |

| Productivity loss at workb | ||||

| Quality, n (%) | 518 (40.5) | 22 (45.8) | 26 (52.0) | 0.211 |

| Quantity, n (%) | 515 (40.2) | 20 (41.7) | 27 (54.0) | 0.150 |

| Sick leave, n=1,111c | n=1,038c | n=36c | n=37c | |

| Sick leave, n (%) | 410 (39.5)c | 15 (41.7)c | 20 (54.1)c | 0.203 |

Notes: Total number of study subjects =1,378. Data presented are mean (standard deviation) unless otherwise stated.

P<0.05,

P<0.001 compared with normal lung function;

P<0.001 compared with mild airflow limitation. Airflow limitation was defined as FEV1/FVC <0.7. Pack-years: (number of cigarettes smoked per day × number of years smoked)/20.

Smoking environment at workplace was only recorded for 1,307 of the 1,378 total subjects, 1,216 of the 1,280 normal lung function, 43 of the 48 mild AL, and 48 of the 50 moderate-to-severe.

Total number of study subjects for productivity loss at work was 1,378.

Sick leave was only recorded for 1,111 of 1,378 total subjects, 1,038 of the 1,280 normal lung function, 36 of the 48 mild AL, and 37 of the 50 moderate-to-severe.

Abbreviations: AL, airflow limitation; BMI, body mass index; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; FVC, forced vital capacity; FEV1/FVC, forced expiratory volume in 1 second to forced vital capacity; FEV1% predicted, forced expiratory volume in 1 second as percentage of predicted; h, hours.

All study participants gave their written informed consent regarding all aspects of the study and to undergo this examination. Our research protocol was approved by the Human Ethics Committee of Kumamoto University (Numbers 436, 816, and 870) and the Japanese Red Cross Kumamoto Health Care Center.

Lung function tests

Spirometry was performed with an electronic spirometer (DISCOM-21 FX: CHEST M.I., Inc., Tokyo, Japan), as previously described,15–18 using equipment and quality criteria that complied with international recommendations.19 Reversibility tests were not performed for this study, and the classifications were based on prebronchodilator levels. According to guidelines from the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (GOLD), we defined AL as an FEV1/FVC ratio <70%.1 The predicted values were determined from the prediction equations published by the Japanese Respiratory Society:20 males, 0.036× height (cm) − 0.028× age − 1.178; females, 0.022× height (cm) − 0.022× age − 0.005. The criteria used for the AL staging were also developed according to the GOLD guidelines and were as follows: Stage I (mild AL): FEV1/FVC <70% and FEV1 ≥80% of predicted value; Stage II (moderate AL): FEV1/FVC <70% and 50%≤FEV1<80% of predicted value; Stage III (severe AL): FEV1/FVC <70% and 30%≤FEV1<50% of predicted value; and Stage IV (very severe AL): FEV1/FVC <70% and FEV1 <30% of predicted value. The subjects were divided into three groups: a control group (normal lung function), GOLD Stage I (mild AL), and GOLD Stages II–IV (moderate-to-very severe AL). The participants with normal lung function were defined as having a FEV1/FVC >70% and FEV1 >80% of the predicted values.

Productivity loss at work and sick leave

Productivity loss at work was measured according to the quality and quantity scale of the quantity and quality (QQ) method,21 as described by Robroek et al.22,23 Participants were requested to indicate how much work they actually performed during regular hours on their most recent regular workday compared to that on a normal workday. The amount of the quality and quantity of productivity was measured on a scale from 0 (nothing) to 10 (regular amount). The outcome productivity loss at work was classified into two categories: no productivity loss (score =10) and productivity loss at work (score of 9 or lower).

Participants were asked how many days in the past 12 months they were not able to work due to health problems.22,23 Those reporting sick leave were categorized into two categories: no sick leave (0 day) and use of sick leave (1 day or more).

Clinical information

Systolic and diastolic blood pressure were measured by trained nurses using an automated digital sphygmomanometer (HEM-904; Omron, Kyoto, Japan) placed on the upper arm at heart height while the participant was seated, following 5 minutes of rest. Hypertension was defined as antihypertensive medication use, systolic blood pressure of 130 mmHg or more, or diastolic blood pressure of 85 mmHg or more. Dyslipidemia was defined as medication use, triglyceride level of 150 mg/dL or more, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol level of 140 mg/dL or more, or high-density lipoprotein cholesterol level of <40 mg/dL. Hyperglycemia was defined as blood glucose-lowering medication use or fasting glucose level of 110 mg/dL or more, as previously described.15

Statistical analyses

The results are given as mean (standard deviation). Differences among normal lung function, mild AL, and moderate-to-severe AL were compared using an analysis of variance, the Kruskal–Wallis test for continuous variables, or the chi-square test for categorical variables. The post hoc Scheffe’s test was used to assess the difference in characteristics according to lung function status. A multivariate logistic regression model adjusted for sex, age, body mass index (BMI), smoking status, hypertension, hyperglycemia, dyslipidemia, sleep duration, work hours per day, and workplace smoking environment was used to assess the relationship between severity of AL and productivity loss at work as well as use of sick leave, with “normal lung function” as the reference. The odds ratios (ORs) were estimated as measures of association with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs).

Adjustments were made according to sex, age, and BMI (model 1). In order to study the influence of lifestyle-related factors (such as models 2 [model 1 + smoking status], 3 [model 2 + hypertension, hyperglycemia, and dyslipidemia], and 4 [model 3 + sleep duration]) and work-related factors (such as models 5 [model 4 + work hours per day] and 6 [model 5 + workplace smoking environment]), these factors were added separately to the basic statistical model (model 1) describing the association between AL severity and productivity loss at work or the presence of sick leave. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 22.0 software (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). Whether the data showed normal distribution was assessed by Shapiro–Wilk test. Values of P<0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Participant characteristics

Table 1 shows the study participants’ characteristics based on lung function status. Of the 1,378 participants, 98 (7.1%) had AL, similar to the percentage reported by the NICE study.24 The prevalence of AL in this study population for the “mild” and “moderate-to-severe” GOLD stages of AL was 3.5% (n=48) and 3.6% (n=50), respectively. In this study, none of the participants demonstrated very severe AL. The prevalence of self-reported obstructive lung disease such as asthma and COPD among participants with AL was 23.5% (n=23) and 1.0% (n=1), respectively.

Significant differences were seen between the normal lung function and mild AL groups in terms of age and pack-years. Significant differences were also seen between those with normal lung function and moderate-to-severe AL in terms of age, weight, and pack-years. No significant difference was seen in relation to BMI.

Significant differences were seen in relation to sleep duration and workplace smoking environment. On the other hand, no significant difference was seen in relation to work hours per day.

Productivity loss at work

Tables 2 and 3 show the ORs for the quality and quantity of productivity loss at work with normal lung function as the reference. In logistic regression models adjusting for sex, age, and BMI (model 1), the presence of the quality of productivity loss was higher in participants with moderate-to-severe AL compared to those with normal lung function (OR =1.97, 95% CI: 1.10–3.52, P=0.022). In logistic regression models 2 (model 1 + smoking status), 3 (model 2 + hypertension, hyperglycemia, and dyslipidemia), 4 (model 3 + sleep duration), 5 (model 4 + work hours per day), and 6 (model 5 + workplace smoking environment), ORs, 95% CI, and P-values were 2.01, 1.12–3.60, and 0.019; 1.99, 1.11–3.58, and 0.021; 1.95, 1.08–3.51, and 0.027; 1.94, 1.07–3.50, and 0.028; and 2.04, 1.12–3.71, and 0.02, respectively. There were no significant differences between normal lung function and mild AL (Table 2).

Table 2.

Multivariable adjusted OR (95% CI) for quality of work productivity at work and airflow limitation severity

| Normal lung function, n=1,280 | Mild AL, n=48 | P-value | Moderate-to-severe AL, n=50 | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude | Reference | 1.25 (0.70–2.22) | 0.46 | 1.59 (0.91–2.81) | 0.11 |

| Model 1: sex, age, BMI | Reference | 1.40 (0.78–2.51) | 0.27 | 1.97 (1.10–3.52) | 0.02 |

| Model 2: model 1 + smoking status | Reference | 1.40 (0.78–2.52) | 0.27 | 2.01 (1.12–3.60) | 0.02 |

| Model 3: model 2 + hypertension, hyperglycemia, dyslipidemia | Reference | 1.40 (0.78–2.53) | 0.26 | 1.99 (1.11–3.58) | 0.02 |

| Model 4: model 3 + sleep duration | Reference | 1.38 (0.76–2.49) | 0.29 | 1.95 (1.08–3.51) | 0.03 |

| Model 5: model 4 + work hours per day | Reference | 1.35 (0.76–2.45) | 0.32 | 1.94 (1.07–3.50) | 0.03 |

| Model 6: model 5 + smoking environment at workplace | Reference | 1.51 (0.81–2.82) | 0.20 | 2.04 (1.12–3.71) | 0.02 |

Note: Total number of study subjects =1,378.

Abbreviations: AL, airflow limitation; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; BMI, body mass index.

Table 3.

Multivariable adjusted OR (95% CI) for quantity of work productivity at work and airflow limitation severity

| Normal lung function, n=1,280 | Mild AL, n=48 | P-value | Moderate-to-severe AL, n=50 | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude | Reference | 1.06 (0.59–1.90) | 0.84 | 1.74 (0.99–3.08) | 0.06 |

| Model 1: sex, age, BMI | Reference | 1.20 (0.66–2.17) | 0.55 | 2.16 (1.21–3.87) | 0.01 |

| Model 2: model 1 + smoking status | Reference | 1.17 (0.64–2.12) | 0.61 | 2.17 (1.21–3.90) | 0.01 |

| Model 3: model 2 + hypertension, hyperglycemia, dyslipidemia | Reference | 1.17 (0.64–2.12) | 0.61 | 2.16 (1.20–3.89) | 0.01 |

| Model 4: model 3 + sleep duration | Reference | 1.15 (0.63–2.09) | 0.65 | 2.11 (1.17–3.81) | 0.01 |

| Model 5: model 4 + work hours per day | Reference | 1.12 (0.61–2.04) | 0.72 | 2.10 (1.16–3.80) | 0.01 |

| Model 6: model 5 + smoking environment at workplace | Reference | 1.31 (0.70–2.46) | 0.40 | 2.19 (1.20–4.00) | 0.01 |

Note: Total number of study subjects =1,378.

Abbreviations: AL, airflow limitation; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; BMI, body mass index.

In logistic regression models adjusting for sex, age, and BMI (model 1), the quantity of productivity loss was higher in participants with moderate-to-severe AL compared to those with normal lung function (OR =2.16, 95% CI: 1.21–3.87, P=0.01). In logistic regression models 2 (model 1 + smoking status), 3 (model 2 + hypertension, hyperglycemia, and dyslipidemia), 4 (model 3 + sleep duration), 5 (model 4 + work hours per day), and 6 (model 5 + workplace smoking environment), ORs, 95% CI, and P-values were 2.17, 1.21–3.90, and 0.01; 2.16, 1.20–3.89, and 0.011; 2.11, 1.17–3.81, and 0.013; 2.10, 1.16–3.80, and 0.014; and 2.19, 1.20–4.00, and 0.011, respectively. There were no significant differences between normal lung function and mild AL (Table 3).

Sick leave

Table 4 shows the ORs for the use of sick leave with normal lung function as the reference. In logistic regression models adjusting for sex, age, and BMI (model 1), use of sick leave was higher in participants with moderate-to-severe AL compared to those with normal lung function (OR =2.45, 95% CI: 1.24–4.86, P=0.01). In logistic regression models 2 (model 1 + smoking status), 3 (model 2 + hypertension, hyperglycemia, and dyslipidemia), 4 (model 3 + sleep duration), 5 (model 4 + work hours per day), and 6 (model 5 + workplace smoking environment), ORs, 95% CI, and P-values were 2.40, 1.21–4.76, and 0.012; 2.43, 1.22–4.85, and 0.012; 2.50, 1.25–5.00, and 0.01; 2.51, 1.25–5.02, and 0.01; and 2.69, 1.33–5.44, and 0.006, respectively. There were no significant differences between normal lung function and mild AL (Table 4).

Table 4.

Multivariable adjusted OR (95% CI) for the presence of sick leave and airflow limitation severity

| Normal lung function, n=1,038 | Mild AL, n=36 | P-value | Moderate-to-severe AL, n=37 | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude | Reference | 1.09 (0.56–2.15) | 0.79 | 1.80 (0.93–3.48) | 0.08 |

| Model 1: sex, age, BMI | Reference | 1.23 (0.62–2.44) | 0.56 | 2.45 (1.24–4.86) | 0.01 |

| Model 2: model 1 + smoking status | Reference | 1.19 (0.59–2.36) | 0.63 | 2.40 (1.21–4.76) | 0.01 |

| Model 3: model 2 + hypertension, hyperglycemia, dyslipidemia | Reference | 1.22 (0.61–2.43) | 0.58 | 2.43 (1.22–4.85) | 0.01 |

| Model 4: model 3 + sleep duration | Reference | 1.21 (0.61–2.43) | 0.59 | 2.50 (1.25–5.00) | 0.01 |

| Model 5: model 4 + work hours per day | Reference | 1.24 (0.62–2.49) | 0.55 | 2.51 (1.25–5.02) | 0.01 |

| Model 6: model 5 + smoking environment at workplace | Reference | 1.36 (0.67–2.76) | 0.40 | 2.69 (1.33–5.44) | 0.006 |

Notes: Total number of study subjects was 1,111 including 1,038 normal lung function, 36 mild AL, and 37 moderate-to-severe AL.

Abbreviations: AL, airflow limitation; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; BMI, body mass index.

Discussion

The main findings of this study are that productivity loss and use of sick leaves were significantly higher in participants with moderate-to-severe AL. This study focused on the possible relationship of AL severity with work productivity loss and sick leave and revealed that productivity loss at work and use of sick leave increased with AL severity in Japanese workers.

In this study, we demonstrated that workers with moderate-to-severe AL were more likely to report quality and quantity of productivity loss at work (OR =2.04, 95% CI: 1.12–3.71, P=0.02 and OR =2.19, 95% CI: 1.20–4.00, P=0.011, respectively) and use of sick leave (OR =2.69, 95% CI: 1.33–5.44, P=0.006) after adjusting for sex, age, BMI, smoking status, hypertension, hyperglycemia, dyslipidemia, sleep duration, work hours per day, and workplace smoking environment. No significant differences were found between normal lung function and mild AL. Thus, these results suggested that increasing severity of AL was associated with productivity loss at work and use of sick leave.

Previous research by Robroek et al22 found that lifestyle-related factors, especially smoking and obesity, were associated with productivity loss at work and use of sick leave. Our results are in line with this study in terms of smoking status.

Comorbidities are major determinants of health status and health expenditure in patients with COPD.1,25,26 Patients with COPD with comorbidities have poorer health outcomes than those without comorbidities.1,25,26 Both insomnia and short sleep duration were independently associated with poor work ability.27 In this study, none of the participants demonstrated insomnia.

Health problems, as shown in the following paragraphs, might relate to work productivity. Therefore, in this study, participants with respiratory diseases except for COPD and asthma, mental disorders,28,29 allergic diseases, all kinds of cancer, cerebrovascular disease, brain tumor, ischemic heart disease, other cardiac diseases, collagen disease, Ménière’s disease, vertigo, and chronic headache were excluded from this study. Mental disorders were independently associated with absenteeism and presenteeism.28,29

Moreover, workplace smoking environment is related to absenteeism and productivity costs.30 Therefore, these factors were added separately to the basic statistical model describing the association between AL severity and productivity loss at work or use of sick leave.

Labor input includes two aspects: quality and quantity. AL might impact both work quality and quantity. The underlying mechanisms of productivity loss at work in participants with AL remain poorly understood at present. A previous report suggested a possible explanation of effects of health problems in terms of AL on work productivity;8,9 participants with AL might slow the pace at which they work and/or take more breaks (quantity). In addition, they may be less careful and have to repeat work due to mistakes (quality). Watz et al9 also reported that significant limitations of physical activity are present in patients with COPD from GOLD Stage II (moderate AL).8 Thus, limitations of physical activity in participants with moderate-to-severe AL might reflect work productivity. More information is needed on how AL impacts work performance.

The authors are aware of possible limitations of this study. First, we did not employ reversibility testing since our Institutional Review Board considered it unacceptable in the absence of a high suspicion of disease. For this reason, participants with AL may have included some with a postbronchodilator FEV1/FVC ratio >70%. In this study, the prevalence of self-reported obstructive lung disease such as asthma and COPD among participants with AL was 23.5% (n=23) and 1.0% (n=1), respectively. Undiagnosed individuals may have had COPD, and they may even have had asthma; thus, we expressed it as “AL” rather than COPD. This limitation has also been reported in previous studies by Oda et al.15

Second, we used subjective single measures of productivity loss at work and use of sick leave according to the QQ questionnaire.21–23 Variability of work ability, which is closely linked to measurement reliability, is an important issue in presenteeism studies. The quantity question of the QQ method was associated with objective work output among floor layers (r=0.48). A disadvantage of this method is that productivity loss is assessed during the previous regular workday, and it does not take into account the expected fluctuations in productivity loss within workers across workdays. This limitation has also been reported in previous studies by Robroek et al.22,23 Other useful instruments have been developed to evaluate presenteeism, such as the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire.31 However, it has not been concluded which instrument provides a better presenteeism estimate.32 Third, this was a cross-sectional study, and the relatively small sample size for the group of AL meant that comparisons against normal lung function had less statistical power. Further studies are needed in a larger sample that includes subjects with a wider severity range of AL. Large-scale prospective studies are needed to further confirm these findings. Finally, this study was a single-center study performed with participants who were interested in this research project. This may limit applicability across different centers and clinical settings.

Despite these limitations, we consider this study to be worthwhile because it is the first to reveal the relationship of AL severity with productivity loss at work and use of sick leave in Japanese workers, as far as the authors know.

Conclusion

AL severity was associated with productivity loss at work and use of sick leave. This relationship remained significant even after adjusting for a range of potential confounders. Even if the cause–effect relationships are still unknown, early intervention in the participants with AL at the workplace might be beneficial for promoting work ability. Additional research is needed to clarify this aspect of presenteeism and absenteeism due to AL.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by a Grant-in-Aid for occupational research from Kumamoto Occupational Health Support Center in Japan, by Health and Labor Sciences Research Grants of the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan (H25-Junkankitou [Seisaku]-Ippan-009), and by the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (15ek0210004h0002). We thank the technicians at the Japanese Red Cross Kumamoto Health Care Center for their excellent technical assistance.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, Updated 2015. [Accessed August 16, 2015]. Available from: http://www.goldcopd.com/

- 2.Lopez AD, Shibuya K, Rao C, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: current burden and future projections. Eur Respir J. 2006;27:397–412. doi: 10.1183/09031936.06.00025805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mathers CD, Mathers CD, Loncar D. Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e442. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization (WHO) The Top 10 Causes of Death Fact Sheet No 310. 2014. [Accessed May 28, 2015]. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs310/en/

- 5.Buist AS, McBurnie MA, Vollmer WM, et al. BOLD Collaborative Research Group International variation in the prevalence of COPD (the BOLD Study): a population-based prevalence study. Lancet. 2007;370(9589):741–750. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61377-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Marco R, Accordini S, Cerveri I, et al. European Community Respiratory Health Survey Study Group An international survey of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in young adults according to GOLD stages. Thorax. 2004;59(2):120–125. doi: 10.1136/thorax.2003.011163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fletcher MJ, Upton J, Taylor-Fishwick J, et al. COPD uncovered: an international survey on the impact of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD] on a working age population. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:612. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Troosters T, Sciurba F, Battaglia S, et al. Physical inactivity in patients with COPD, a controlled multi-center pilot-study. Respir Med. 2010;104:1005–1011. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2010.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Watz H, Waschki B, Meyer T, Magnussen H. Physical activity in patients with COPD. Eur Respir J. 2009;33:262–272. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00024608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Halpern MT, Stanford RH, Borker R. The burden of COPD in the U.S.A.: results from the confronting COPD survey. Respir Med. 2003;97(suppl C):S81–S89. doi: 10.1016/s0954-6111(03)80028-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Britton M. The burden of COPD in the U.K.: results from the confronting COPD survey. Respir Med. 2003;97(suppl C):S71–S79. doi: 10.1016/s0954-6111(03)80027-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DiBonaventura Md, Paulose-Ram R, Su J, et al. The burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease among employed adults. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2012;7:211–219. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S29280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Allen-Ramey FC, Gupta S, DiBonaventura Md. Patient characteristics, treatment patterns, and health outcomes among COPD phenotypes. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2012;7:779–797. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S35501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Patel JG, Nagar SP, Dalal AA. Indirect costs in chronic pulmonary disease: a review of economic burden on employers and individuals in the United States. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2012;7:779–797. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S57157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oda M, Omori H, Onoue A, et al. Association between airflow limitation severity and arterial stiffness as determined by the brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity: a cross-sectional study. Intern Med. 2015;54:2569–2575. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.54.3778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Omori H, Tsuji M, Sata K, et al. Correlation of C-reactive protein with disease severity in CT diagnosed emphysema. Respirology. 2009;14:551–558. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2009.01519.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Funakoshi Y, Omori H, Mihara S, Marubayashi T, Katoh T. Association between airflow obstruction and the metabolic syndrome or its components in Japanese men. Intern Med. 2010;49(19):2093–2099. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.49.3882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Funakoshi Y, Omori H, Mihara S, et al. C-reactive protein levels, airflow obstruction, and chronic kidney disease. Environ Health Prev Med. 2012;17(1):18–26. doi: 10.1007/s12199-011-0214-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller MR, Hankinson J, Brusasco V, et al. ATS/ERS Task Force Standardisation of spirometry. Eur Respir J. 2005;26:319–338. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00034805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Japanese Respiratory Society Reference Values for Spirometry in Japanese Adults, in Japanese. [Accessed August 5, 2015]. [cited June 14, 2014]. Available from: http://www.jrs.or.jp/modules/guidelines/index.php?content_id=12.

- 21.Brouwer WBF, Koopmanschap M, Rutten FFH. Productivity losses without absence: measurement validation and empirical evidence. Health Policy. 1999;48:13–27. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8510(99)00028-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Robroek SJW, Van den Berg TIJ, Plat JF, Burdorf A. The role of obesity and lifestyle behaviours in a productive workforce. Occup Environ Med. 2011;68:134–139. doi: 10.1136/oem.2010.055962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Robroek SJW, van Lenthe FJ, Burdorf A. The role of lifestyle, health, and work in educational inequalities in sick leave and productivity loss at work. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2013;86:619–627. doi: 10.1007/s00420-012-0793-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fukuchi Y, Nishimura M, Ichinose M, et al. COPD in Japan: the Nippon COPD Epidemiology Study. Respirology. 2004;9:458–465. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2004.00637.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mannino DM, Thorn D, Swenson A, Holguin F. Prevalence and outcomes of diabetes, hypertension and cardiovascular disease in COPD. Eur Respir J. 2008;32(4):962–969. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00012408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mannino DM, Higuchi K, Yu TC, et al. Economic burden of COPD in the presence of comorbidities. Chest. 2015;148(1):138–150. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-2434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lian Y, Xiao J, Liu Y, et al. Associations between insomnia, sleep duration and poor work ability. J Psychosom Res. 2015;78:45–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2014.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gupta S, Isherwood G, Jones K, van Impe K. Productivity loss and resource utilization, and associated indirect and direct costs in individuals providing care for adults with schizophrenia in the EU5. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2015;7:593–602. doi: 10.2147/CEOR.S94334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rost KM, Meng H, Xu S. Work productivity loss from depression: evidence from an employer survey. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:597–605. doi: 10.1186/s12913-014-0597-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tsai SP, Wen CP, Hu SC, Cheng TY, Huang SJ. Workplace smoking related absenteeism and productivity costs in Taiwan. Tob Control. 2005;14(suppl I):i33–i37. doi: 10.1136/tc.2003.005561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reilly MC, Zbrozek AS, Dukes EM. The validity and reproducibility of a work productivity and activity impairment instrument. Pharmacoeconomics. 1993;4(5):353–365. doi: 10.2165/00019053-199304050-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang W, Bansback N, Anis AH. Measuring and valuing productivity loss due to poor health: a critical review. Soc Sci Med. 2011;72:185–192. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]