Significance

Anti-cytokine therapy has revolutionized the treatment of autoimmune diseases. However, recent data suggest that cytokines, in particular TNF, produced by various cell types may play distinct and sometimes opposite roles in the inflammatory responses. In certain autoimmune diseases TNF produced by monocytes and macrophages plays a pathogenic role, whereas TNF produced by T cells may be protective. In addition, T-cell–derived TNF is indispensable for resistance to infections, such as tuberculosis. To demonstrate that cell-type–restricted anti-cytokine therapy may be advantageous, we generated bispecific antibodies that neutralize TNF produced by myeloid cells. Cell-targeted inhibition of TNF is more effective than systemic TNF ablation in protecting mice from TNF-mediated hepatotoxicity. This provides a rationale for the development of novel anti-TNF agents.

Keywords: anti-cytokine therapy, TNF, bispecific antibody, autoimmunity, humanized mice

Abstract

Overexpression of TNF contributes to pathogenesis of multiple autoimmune diseases, accounting for a remarkable success of anti-TNF therapy. TNF is produced by a variety of cell types, and it can play either a beneficial or a deleterious role. In particular, in autoimmunity pathogenic TNF may be derived from restricted cellular sources. In this study we evaluated the feasibility of cell-type–restricted TNF inhibition in vivo. To this end, we engineered MYSTI (Myeloid-Specific TNF Inhibitor)—a recombinant bispecific antibody that binds to the F4/80 surface molecule on myeloid cells and to human TNF (hTNF). In macrophage cultures derived from TNF humanized mice MYSTI could capture the secreted hTNF, limiting its bioavailability. Additionally, as evaluated in TNF humanized mice, MYSTI was superior to an otherwise analogous systemic TNF inhibitor in protecting mice from lethal LPS/D-Galactosamine–induced hepatotoxicity. Our results suggest a novel and more specific approach to inhibiting TNF in pathologies primarily driven by macrophage-derived TNF.

TNF is a proinflammatory and immunoregulatory cytokine with diverse functions in host defense and in immune homeostasis. When overexpressed systemically or in distinct histological compartments, TNF may contribute to various disease states. In particular, TNF has long been known as one of the key cytokines involved in the development of rheumatoid arthritis (1), ankylosing spondylitis (2), Crohn’s disease (3), multiple sclerosis (4), psoriasis (5), and several other autoimmune diseases (6, 7). Disrupting TNF signaling by recombinant monoclonal antibodies or engineered soluble receptors proved to be effective in patients and became an important therapeutic option in treatment of some of these conditions (8–11), whereas in other cases it was found to be ineffective (12) or even detrimental (13). Importantly, systemic TNF inhibition may itself cause autoimmune conditions (14), disrupt organized lymphoid microstructure (15), and induce severe side effects, such as reactivation of latent tuberculosis infection (16), suggesting a potential divergent nature of TNF-mediated signaling.

Among the cell types capable of producing TNF are macrophages, monocytes, neutrophils, dendritic cells, T and B lymphocytes, and several types of stromal cells (17). We have previously reported that cellular sources of TNF specify its distinct functions in protective and autoreactive immune responses (18, 19) and in controlling of secondary lymphoid organ microstructure (20). TNF derived from myeloid cells was shown to play a nonredundant deleterious role in several disease models. TNF is a transmembrane protein, which needs to be cleaved off to act systemically. The complex multilevel regulation of ADAM17 metalloprotease activity, which cleaves the transmembrane TNF (21, 22), suggests that different cell types may vary in the efficiency of TNF precursor processing.

Monocytes and macrophages play a very prominent role in autoimmunity, in particular, in rheumatoid arthritis (23), and they are among the main cellular sources of TNF (18). As macrophages are also the primary source of systemic pathogenic TNF in the models of severe sepsis and (alongside T-cell–derived TNF) in concanavalin-A–induced hepatitis (18) and experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) (19), we hypothesized that it may be advantageous to selectively target macrophage-derived TNF. One of the approaches to achieve this goal would be to use a bispecific reagent that binds to a membrane-associated molecule expressed selectively on monocytes/macrophages and simultaneously binds (and neutralizes) TNF secreted by the targeted cell.

F4/80 is a cell-surface molecule highly expressed on murine monocytes and tissue macrophages (including Kupffer cells in the liver) and is widely used as a specific lineage marker in flow cytometry and immunohistology (24, 25).

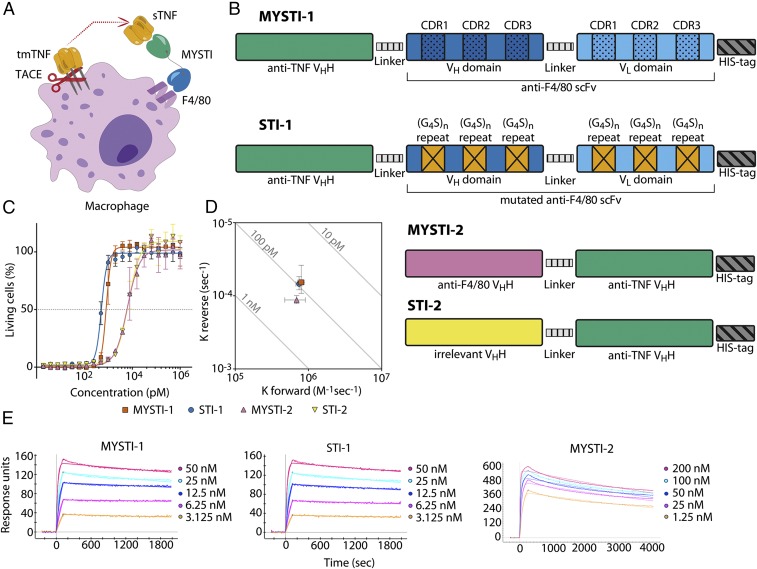

To address the hypothesis that cell-type–restricted TNF inhibition can be advantageous in certain disease models, we have constructed bispecific antibodies designated here as Myeloid-Specific TNF Inhibitors (MYSTI), which simultaneously bind F4/80 and human TNF (hTNF) and inhibit interaction of TNF with its receptors (Fig. 1A), as well as similar control antibodies referred to as Systemic TNF Inhibitors (STI) unable to bind F4/80 but with preserved hTNF binding.

Fig. 1.

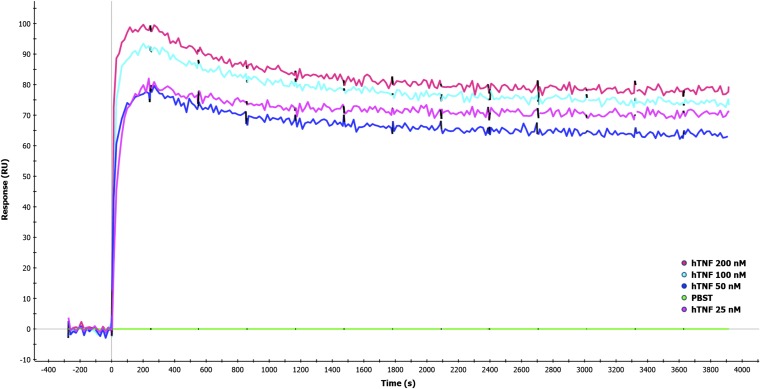

MYSTI and STI had similar kinetics of interaction with hTNF and similar anti-hTNF activity. (A) One specificity of MYSTI attaches to the macrophage surface, whereas another captures and retains secreted TNF. (B) MYSTI-1 from N to C terminus comprises anti-TNF VHH, GSGGGGSG linker, anti-F4/80 scFv, and His-tag. CDRs in anti-F4/80 variable heavy and light chain domains are highlighted. Mutated form of MYSTI-1, designated as STI-1, has the same amino acid sequence except for the six CDRs in anti-F4/80 scFv, all of which were substituted with (G4S)n sequences of the same length. Mutations are marked with crosses in orange boxes. MYSTI-2 comprises anti-F4/80 VHH, flexible linker from the hinge region of camel antibody, anti-TNF VHH, and His-tag. In the corresponding systemic TNF inhibitor, STI-2 anti-F4/80 VHH was replaced by an irrelevant VHH. (C) Anti-TNF activities of MYSTI, STI, MYSTI-2, and STI-2 were determined by cytotoxic assay. L929 cells were incubated in the presence of constant concentration of hTNF and Actinomycin D and serial dilutions of recombinant antibodies. Percentage of living cells ±SD is plotted. (D) Kinetics of interaction of antibodies with recombinant hTNF as measured by SPR. Kforward (on-rate) and Kreverse (off-rate) values of MYSTI-1, STI-1, and MYSTI-2 ±SD are plotted on isoaffinity graph. Diagonal lines represent dissociation constants. (E) Sensograms plus fitted lines of interaction of MYSTI-1, STI-1, and MYSTI-2 with serial dilutions of hTNF are shown. Data in C–E are representative of more than three independent experiments. sTNF: soluble TNF; tmTNF: transmembrane TNF; TACE: TNF converting enzyme.

We demonstrated that in vitro MYSTI, but not STI, could attach to the cell surface of macrophages and prevent TNF secretion into the culture media. Most importantly, in vivo at the same dose MYSTI was superior to its nontargeted counterpart (STI) in protecting mice from lethal LPS/D-Galactosamine (D-Gal) toxicity, an experimental model in which myeloid cells are the principal source of deleterious TNF (18). This study provides a rationale for cell-type–restricted anti-cytokine therapy.

Results

Cloning, Expression, and Purification of MYSTI and STI Recombinant Antibodies.

We have designed two bispecific antibodies comprising anti-F4/80 and anti-hTNF domains that bind and neutralize human TNF secreted by monocytes and macrophages derived from TNF humanized mice (26). For both antibodies we have created appropriate controls serving as systemic TNF inhibitors (Fig. 1B).

MYSTI-1 antibody comprised anti-F4/80 single-chain antibody (scFv) and a previously reported high-affinity single-domain antibody (VHH) targeting human TNF (27–29) joined by a flexible glycine–serine linker. A C-terminal histidine tag was genetically added to facilitate its purification. To create appropriate control antibody STI-1, we used the intact anti-TNF moiety of MYSTI-1, but substituted the cDNA coding for anti-F4/80 scFv with a de-novo–synthesized scFv gene in which all six complementarity determining regions (CDRs) were replaced with (Gly4Ser)n sequences of the same length.

MYSTI-2 antibody comprised a novel anti-F4/80 VHH (Fig. S1; Fig. S2, Table S1; SI Materials and Methods) and the same anti-TNF VHH module as in MYSTI-1/STI-1, whereas its control—STI-2—contained an irrelevant VHH (30) in place of anti-F4/80 moiety, thus acting as a systemic TNF inhibitor.

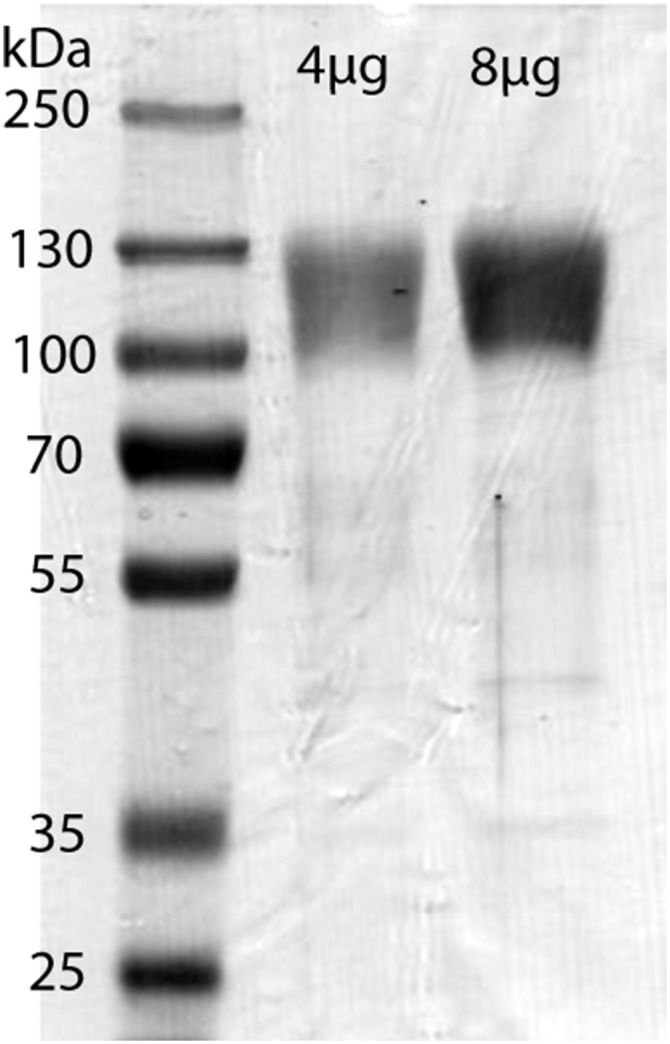

Fig. S1.

Reduced SDS/PAGE of recombinant F4/80 fragment. Coomassie staining. MW marker sizes and amount of protein per lane are indicated.

Fig. S2.

Kinetics of anti-F4/80 VHH interaction with recombinant F4/80. Sensograms are shown for anti-F4/80 VHH immobilized on (A) neutravidin or (B) Ni NTA-covered covered sensor chip.

Table S1.

Kinetic values and dissociation constants for interaction of anti-F4/80 VHH antibody with recombinant F4/80 measured by SPR

| Chip coating | On-rate (M−1 sec−1) | Off-rate (sec−1) | KD (M) |

| Neutravidin | 7.03 × 104 | 1.52 × 10−5 | 2.17 × 10−10 |

| NTA | 5.92 × 104 | 5.91 × 10−6 | 9.98 × 10−11 |

On-rate, off-rate, and dissociation constant (KD) were derived from sensogram data using simultaneous fitting of 1:1 Langmuir interaction model to the association and dissociation phases of all curves in the set. Shown here are dissociation constant, association speed (on-rate), and dissociation speed (off-rate).

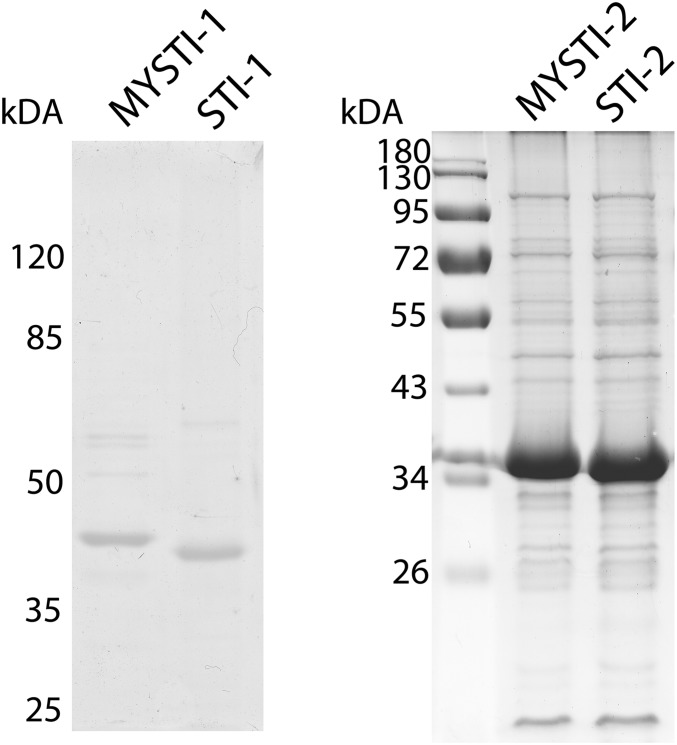

All recombinant antibodies were expressed in Escherichia coli and purified by affinity chromatography (for SDS/PAGE, see Fig. S3).

Fig. S3.

Reduced SDS/PAGE of MYSTI-1, STI-1, MYSTI-2, and STI-2 recombinant antibodies. Coomassie staining. The apparent molecular weights are in good agreement with predictions from the amino acid sequence (45 and 42 kDa for MYSTI-1 and STI-1 and 33 kDA for MYSTI-2 and STI-2).

Binding of MYSTI and STI to Recombinant Human TNF and Inhibition of Its Activity.

Kinetics of interactions of bispecific antibodies with recombinant hTNF was determined by surface plasmon resonance (SPR). All recombinant antibodies demonstrated high-affinity interaction with hTNF and had similar on- and off-rates (Fig. 1 D and E and Table S2). The low dissociation rate of the MYSTI antibodies suggested that they may be capable of remaining bound to the hTNF.

Table S2.

Kinetic values and dissociation constants of interaction of MYSTI and STI with hTNF as measured by SPR

| Sample | KD, M (SD) | On-rate (M−1 sec−1) (SD) | Off-rate (sec−1) (SD) |

| MYSTI-1 | 8.48 × 10−11 (4.21 × 10−11) | 7.97 × 105 (8.95 × 104) | 6.54 × 10−5 (2.71 × 10−5) |

| STI-1 | 9.47 × 10−11 (3.02 × 10−11) | 7.45 × 105 (7.13 × 104) | 6.88 × 10−5 (1.4 × 10−5) |

| MYSTI-2 | 1.69 × 10−10 (5.24 × 10−11) | 1.14 × 105 (1.41 × 105) | 6.91 × 10–5 (2.2 × 10−5) |

On-rate, off-rate, and dissociation constant were derived from sensogram data using simultaneous fitting of 1:1 Langmuir interaction model to the association and dissociation phases of all curves in the set. Shown here are dissociation constant, association speed (on-rate), and dissociation speed (off-rate) ±SD.

To compare TNF-inhibitory properties of MYSTI and STI, we performed a TNF-induced cytotoxicity assay using the L929 murine fibrosarcoma line and found that MYSTI and STI had very similar hTNF inhibitory activity in vitro (Fig. 1C).

MYSTI but Not STI Binds to the Surface of Macrophages via Anti-F4/80 Moiety.

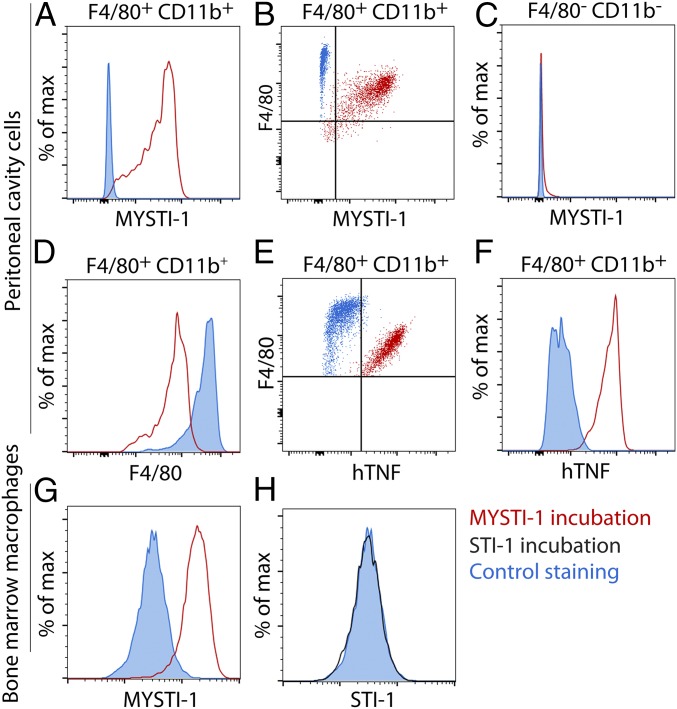

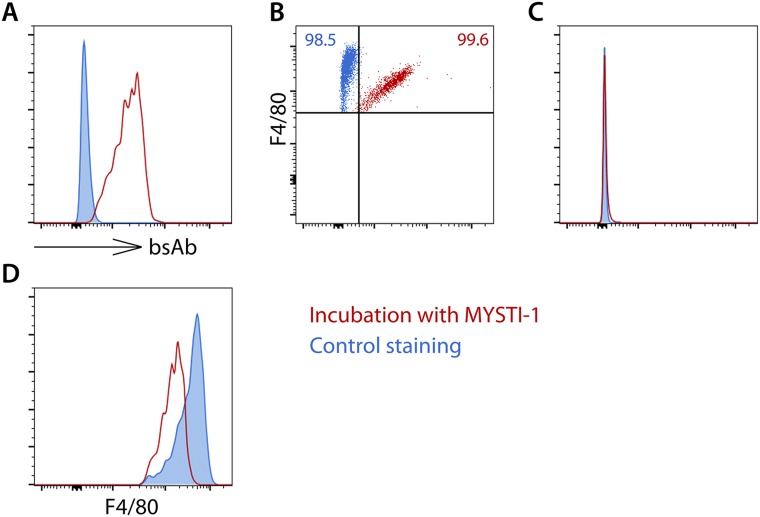

Flow cytometry analysis demonstrated that bispecific antibody MYSTI via interaction with the F4/80 protein could attach to both peritoneal cavity macrophages (Fig. 2 A and B and Fig. S4 A and B) and bone-marrow–derived macrophages (Fig. 2G), whereas mutations or substitutions introduced into STI prevented binding to F4/80 (Fig. 2H). Lack of MYSTI interaction with F4/80 negative cells (mostly B and T cells) (Fig. 2C and Fig. S4C) and observed decrease in F4/80 counterstaining in samples preincubated with MYSTI (Fig. 2D and Fig. S4D) confirmed a specific interaction with F4/80. Importantly, we also demonstrated that MYSTI could bind macrophage-associated F4/80 and hTNF simultaneously (Fig. 2 E and F and Fig. S5). Thus, these bispecific reagents can selectively capture hTNF produced by macrophages.

Fig. 2.

MYSTI attaches to macrophage surface via specific interaction with F4/80 and simultaneously binds hTNF. (A–F) Peritoneal cavity cells from WT mice were incubated with or without MYSTI-1 and then with or without exogenously added recombinant hTNF and stained either with rabbit anti-VHH antibodies and with fluorescently labeled anti-rabbit IgG or with anti-TNF antibodies plus counterstained with anti-F4/80 and anti-CD11b fluorescent antibodies and then analyzed by flow cytometry. (A and B) MYSTI-1 interacts with F4/80- and CD11b-positive cells. (C) MYSTI-1 does not interact with F4/80-negative cells. (D) Incubation with MYSTI-1 decreased the intensity of anti-F4/80 counterstaining. (E and F) Exogenously added hTNF interacted with MYSTI-1 bound to cellular surface. (G and H) MYSTI-1 but not STI-1 interacts with bone-marrow–derived macrophages. Cell gating is indicated at the top of the plots where applicable.

Fig. S4.

MYSTI-1 attaches to macrophage surface via specific interaction with F4/80 and can simultaneously bind hTNF. Peritoneal cavity cells were incubated with or without MYSTI-1 and stained with mouse anti–His-tag antibodies and then with anti-mouse IgG PE-conjugated antibody and counterstained with anti-F4/80 and anti-CD11b fluorescent antibodies and then analyzed by flow cytometry. (A and B) MYSTI-1 interacts with F4/80- and CD11b-positive cells. (C) MYSTI-1 does not interact with F4/80-negative cells. (D) Incubation with MYSTI-1 decreased the intensity of anti-F4/80 counterstaining.

Fig. S5.

MYSTI-2 can simultaneously interact with F4/80 and TNF. Recombinant F4/80 was immobilized to the chip surface, and then MYSTI-2 was applied followed by recombinant human TNF or PBS.

Retention of Endogenously Produced hTNF on the Surface of Macrophages by MYSTI.

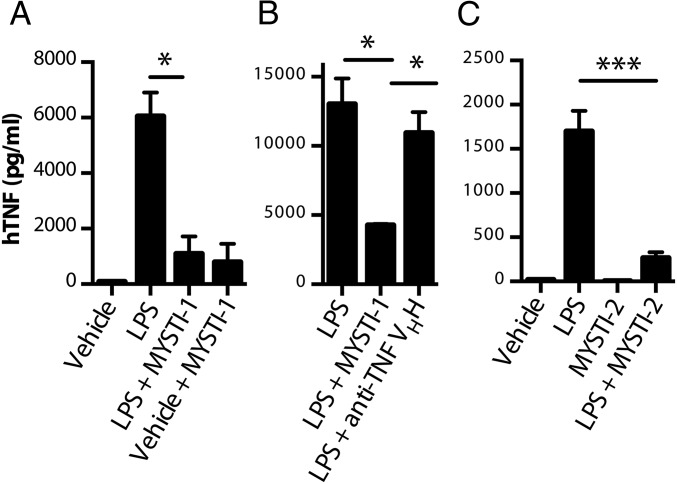

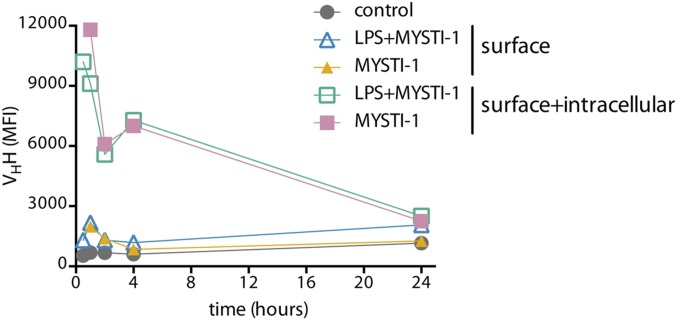

As the anti-TNF moiety of both MYSTI and STI could bind and neutralize human but not murine TNF (27), in all subsequent experiments we used primary cells derived from TNF humanized mice in which the murine TNF gene was substituted by its human counterpart (26, 31, 32). Peritoneal cavity macrophages from such mice were used to test whether MYSTI could prevent the release of soluble hTNF into the culture medium upon LPS stimulation. We found that hTNF levels in the supernatants of macrophage cultures were significantly reduced when macrophages were preincubated with MYSTI and then washed, suggesting that soluble hTNF released by macrophages was captured and retained by bispecific antibody on the surface of the peritoneal cavity macrophages at least for the duration of the experiment (Fig. 3A). These findings were confirmed with bone-marrow–derived macrophage cultures from TNF humanized mice: preincubation with MYSTI significantly decreased hTNF activity in supernatants upon LPS stimulation, whereas preincubation with neutralizing but monospecific anti-TNF VHH or with STI did not (Fig. 3 B and C). Interestingly, MYSTI can be internalized from the macrophage membrane (Fig. S7).

Fig. 3.

MYSTI prevented release of hTNF from LPS-stimulated macrophages derived from TNF humanized mice. (A) Peritoneal cavity macrophages were preincubated with or without MYSTI-1 and then stimulated with LPS for 4 h. Subsequently, concentrations of hTNF in the supernatants were measured by ELISA (MYSTI at the relevant concentrations did not affect hTNF detection in this assay) (Fig. S6). (B) Bone-marrow–derived macrophages were preincubated with MYSTI-1 or anti-TNF VHH or vehicle buffer and then stimulated with LPS for 4 h. Concentrations of active hTNF were measured by cytotoxic assay on L929 cells. (C) Bone-marrow–derived macrophages were preincubated with MYSTI-2 or STI-2 or vehicle buffer and then stimulated with LPS for 4 h. Concentrations of hTNF in the supernatants were measured by ELISA. Mean levels of hTNF in duplicates ±SD are plotted. Data are representative of several independent experiments. (*P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001.)

Fig. S7.

Bispecific antibody can be internalized from the surface of macrophages. Bone-marrow–derived macrophages prepared from TNF humanized mice were incubated with LPS only, MYSTI-1 only, or MYSTI-1 followed by LPS. Cells were collected at various time points. To estimate surface levels of MYSTI-1, live cells were stained with anti-VHH antibody and then fixed. To quantify the total levels of both surface and intracellular fractions of MYSTI-1, cells were permeabilized and further stained with anti-VHH antibody. MYSTI-1 levels were estimated by flow cytometry as mean of fluorescence intensity (MFI). Data are representative of at least two independent experiments.

Advantage of Macrophage-Targeted Versus Systemic TNF Inhibition in LPS/D-Galactosamine–Induced Hepatotoxicity.

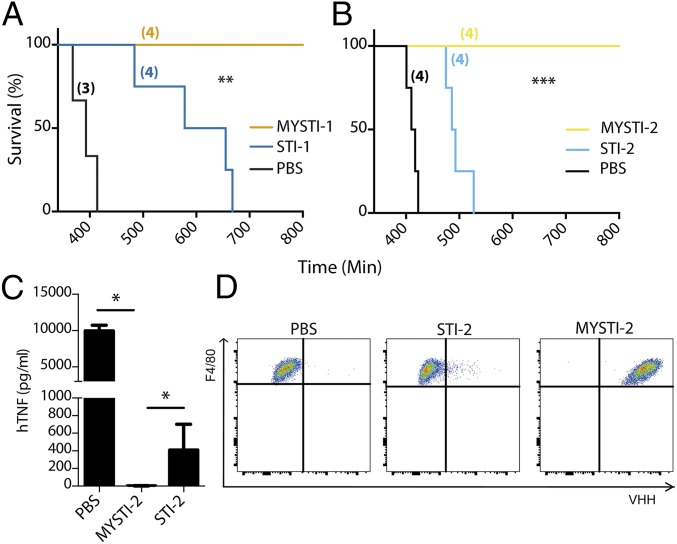

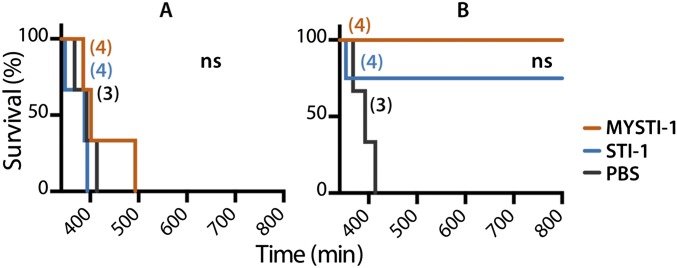

We established previously that macrophages are the source of deleterious TNF in LPS/D-Gal–induced hepatotoxicity (18). We also found that this toxicity can be inhibited by administration of anti-hTNF antibodies or soluble TNF receptors in TNF humanized mice (32). To compare the effects of macrophage/monocyte targeted TNF retention (represented by MYSTI) as opposed to systemic TNF inhibition (represented by STI), we compared these two pairs of recombinant antibodies in the experimental model of acute hepatotoxicity in TNF humanized mice. MYSTI-1 and STI-1 at doses of 750 U/g or the vehicle buffer were injected 30 min before LPS/D-Gal administration. All of the mice that received MYSTI-1 survived (Fig. 4A) whereas a similar dose of STI-1 antibody, which had otherwise the same anti-TNF activity and similar molecular weight (MW) and pI, was insufficient to protect mice from lethality, although at higher doses STI also prevented the hepatotoxicity (Fig. S8).

Fig. 4.

Targeting the inhibitor to the surface of myeloid cells substantially increases effectiveness of TNF inhibition in vivo. TNF humanized mice were injected either with MYSTI, STI, or buffer. Number of mice per group is indicated in parentheses. (A and B) Thirty minutes later mice were injected with an otherwise lethal dose of LPS/D-Gal. (C and D) Thirty minutes later mice were injected with 10 µg of LPS, and 1 h later mice were killed for peritoneal cells and blood sera collection. (A) Survival curves of mice injected with 750 U/g of MYSTI-1 or STI-1 compared with buffer. (B) Survival curves of mice injected with 130 U/g of MYSTI-2 or STI-2 compared with buffer. (C) Levels of hTNF in blood serum as measured by ELISA. (D) Surface levels of MYSTI on peritoneal F4/80+ cells as measured by flow cytometry. MYSTI and STI were compared pairwise using log-rank test (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001). Data are representative of at least three independent experiments.

Fig. S8.

Protection from LPS/D-Gal toxicity in vivo by MYSTI and STI. TNF humanized mice were injected either with macrophage/monocyte targeted anti-hTNF MYSTI-1, control systemic hTNF-inhibitor (STI-1), or buffer. Thirty minutes later mice were injected with otherwise lethal dose of LPS/D-Gal. Survival curves of mice injected with (A) 300 U/g of (B) 1,500 U/g of MYSTI-1 or STI-1 compared with buffer. Systemic and macrophage-targeted inhibitors were compared pairwise using log-rank test. ns, Not significant. Number of mice per group is indicated in parentheses. Data are representative of at least three independent experiments.

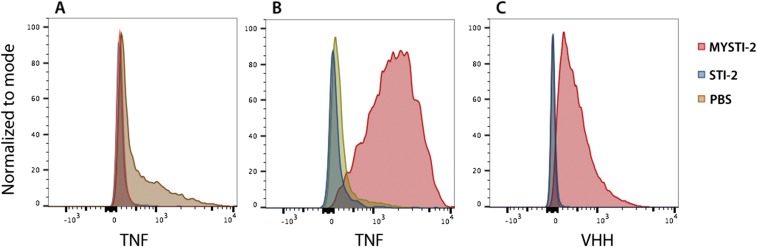

The superior efficiency of macrophage-targeted anti-TNF therapy was reproduced in a comparison of independently developed macrophage-specific TNF inhibitor MYSTI-2 with its respective control antibody STI-2 (Fig. 4B). This result is consistent with significantly lower levels of hTNF in sera of TNF humanized mice stimulated with LPS after MYSTI-2 administration compared with STI, despite the fact that both reagents carried an identical hTNF-binding VHH module (Fig. 4C). MYSTI but not STI was able to bind to F4/80-positive peritoneal macrophages in vivo (Fig. 4D), thereby preventing LPS-mediated TNF production (Fig. S9).

Fig. S9.

MYSTI-2 binds to F4/80-positive peritoneal cells in vivo, blocks LPS-induced hTNF production, and retains the ability to capture hTNF. (A) TNF humanized mice were injected with PBS or MYSTI-2 or STI-2. Thirty minutes later, mice were challenged with LPS. One hour later, peritoneal cavity cells were collected, stained against F4/80 and anti-TNF, and analyzed by flow cytometry. (B) TNF humanized mice were injected with PBS or MYSTI-2 or STI-2. Thirty minutes later, mice were challenged with LPS. One hour later, peritoneal cavity cells were collected, and incubated with recombinant human TNF. Cells were stained against F4/80 and anti-TNF and analyzed by flow cytometry. Data are representative of at least two independent experiments.

Overall these results suggested that macrophage-targeted inhibition of TNF is advantageous in terms of required drug dose for protection/survival.

SI Materials and Methods

Generation of Anti-F4/80 VHH Antibody.

To obtain F4/80-specific VHH antibody, we cloned the extracellular portion of F4/80 protein, expressed it in a eukaryotic system, and used it to immunize camel, after which F4/80-specific VHHs were selected by phage display from the immune library, as outlined below.

F4/80 cloning, expression, and purification.

Sequence coding for the extracellular part of F4/80 flanked at both N and C termini with affinity tags was codon-optimized for mammalian expression, synthesized by GenScript, and subcloned into pOptiVec vector (Invitrogen). A transfection grade plasmid DNA was purified using a Qiagen Plasmid Maxi kit, digested with SalI, and then purified with a QIAquick DNA extraction kit. Linearized vector was used for transfection of DG44 cells (Invitrogen) and cultured in Erlenmeyer flasks in CD DG44 medium (Gibco) supplemented with 8 mM Glutamax-1 and HT supplement at 37 °C at 8% CO2 in a humidified incubator with shaking. Before transfection, cells were collected and resuspended in CHO-S SFMII media (Gibco). Transfection was performed with PeiProTM (Polyplus Transfections) at a cell density of 4 × 106 cells/mL 6 h posttransfection; 3 vol of CD OptiCHO medium (Invitrogen) with HT supplement were added, and cells were cultured for another 48 h. Next, the media was changed for CD OptiCHO without HT supplement, and cells were maintained at 0.3–0.5 × 106/mL for 4 wk until the viability increased to 95%.

Transfected cells were next cultured in CD OptiCHO medium lacking hypoxanthine and thymidine with daily monitoring of cell viability. After reaching viability values higher than 95% (in approximately 3 wk), the cells were collected and subjected to gene amplification with 500 nM of methotrexate (Sigma).

For recombinant protein production, cell pool was plated in CD OptiCHO medium supplemented with 20% of Cell Boost5 (HyClone). Culture was collected after 6 d at a cell density of 8–9 million per milliliter. Cells were centrifuged, and culture media was filtered and used for protein purification.

Conditioned medium was loaded onto a column with CL-4B Sepharose with attached anti-tag antibodies. The column was subsequently washed with 20 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.5 (buffer A), 20 mM Tris, 700 mM NaCl, pH 7.5 (buffer B) and 20 mM Tris, 700 mM NaCl, pH 7.5 (buffer C). Bound protein was eluted with 0.1 M Glycine (pH 2.5), and the eluate was immediately neutralized with Tris buffer. SDS/PAGE is shown in Fig. S1.

Camel immunization and phage display.

Recombinant F4/80 was used to immunize Camelus bactrianus. After repeated immunizations, immune VHH library was generated and anti-F4/80 VHH antibodies were selected by phage display according to previously published protocol (45, 46).

Several selected clones containing C-terminal HIS-tag were purified by immobilized metal-affinity chromatography, and then their affinity to F4/80 was evaluated by surface plasmon resonance (Fig. S2).

Design and Generation of Bispecific Recombinant Antibodies.

MYSTI-1 and STI-1.

DNA sequence encoding MYSTI-1, as shown in Fig. 1B, was assembled by overlap PCR as follows: the gene encoding previously described anti-hTNF VHH (27–29) was joined by a flexible glycine–serine linker to anti-F4/80 scFv antibody (GenBank accession nos. KU677977 and KU677978). NcoI and XhoI restriction sites were included in forward and reverse primer sequences, respectively, so that, when cloned to expression vector pET-28b (Novagen), the C-terminal 6XHis tag sequence was in the same reading frame as the rest of the cDNA. To obtain control antibody, the STI-1 gene encoding the mutated anti-F4/80 scFv part was synthesized de novo (Geneart) and cloned into position of the original anti-F4/80 scFv sequence. As a result, STI-1 had the same nucleotide and amino acid sequence as MYSTI-1, except that all six of its CDRs in the anti-F4/80 scFv portion were substituted by (Gly4Ser)n insertions of the same length as the original CDR nucleotide sequence.

MYSTI-2 and STI-2.

One of the selected anti-F4/80 VHH antibodies with highest affinity to F4/80 was cloned into expression vector as a fusion protein with anti-TNF VHH (27–29), joined by a flexible linker derived from amino acid sequence of the hinge region of camelid antibody. To create an appropriate control, an irrelevant VHH antibody, specific to human lactoferrin (30), was cloned in place of the anti-F4/80 VHH.

Expression and Purification of Bispecific Antibodies.

MYSTI-1 and STI-1.

Expression vectors carrying MYSTI-1 and STI-1 genes were used to transform Rosetta2(DE3)pLysS cells (Novagen). Best producers were selected from transformed clones by colony blot procedure using HisProbe-HRP Conjugate (Pierce, 15165). Bacterial cultures were grown in LB media containing 50 µg/mL Carbenicillin (Sigma-Aldrich, C1389) and 50 µg/mL Chloramphenicol (Sigma-Aldrich, C1863) until midlog phase and induced with 0.2 mM isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside. After 4 h of induction, cultures were centrifuged at 3,200 × g for 30 min. Pellets were frozen and later resuspended in lysis buffer [50 mM Tris⋅HCl, 300 mM NaCl, 5% (vol/vol) glycerol, 0.5% Triton X-100, 10,000 U/mL lysozyme, 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol] and disrupted by ultrasound. After centrifugation at 17,000 × g for 40 min, supernatant was collected and passed through a 0.22-µm filter. Recombinant antibodies were purified from supernatant using Ni-NTA agarose (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Elution fraction containing recombinant antibodies was concentrated, dialyzed against PBS, sterile-filtered, and stored at 4 °C. Concentrations were measured by bicinchoninic acid assay (Pierce) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Sample purity was assessed by SDS/PAGE (Fig. S3A). Average yield was around 1 mg/L.

MYSTI-2 and STI-2.

E. coli cells containing similarly cloned MYSTI-2 or STI-2 were resuspended in 20 mL buffer 1 [25 mM Hepes buffer, pH 7.0, containing 0.5 M NaCl, 1% Triton ×100, 10% (vol/vol) glycerol, 5 mM imidazole, 4 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 0.2 mM PMSF, and a mixture of 10 µg DNaseI, 10 µg RNaseA, and 50 µg lysozyme] and were disintegrated by sonication. After centrifugation at 17,000 × g for 40 min, supernatant was collected and passed through a 0.22-μm filter. MYSTI-2/STI-2 recombinant antibodies were purified from the supernatant using Ni-NTA agarose metal affinity resin (Invitrogen) equilibrated with buffer 1. The column was washed with 20 column bed volumes of buffer 2 [25 mM Hepes buffer, pH 7.0, containing 0.5 M NaCl, 0.1% Triton ×100, 10% (vol/vol) glycerol, 10 mM imidazole, 4 mM 2-mercaptoethanol]. Protein was eluted with buffer 3 [25 mM Hepes buffer, pH 7.0, containing 0.5 M NaCl, 0.1% Triton ×100, 10% (vol/vol) glycerol, 300 mM imidazole, 4 mM 2-mercaptoethanol]. Eluted protein was dialyzed against buffer 4 [25 mM Hepes, pH 7.0, 150 mM NaCl, 5% (vol/vol) glycerol] and concentrated using a 15-mL Amicon Ultra concentrator (Millipore). Sample purity was assessed by SDS/PAGE (Fig. S3B). Average yield was around 50–60 mg/L.

Measurement of Kinetics of Protein–Protein Interactions by Surface Plasmon Resonance Technology.

SPR experiments were performed using the ProteOn XPR36 system (Bio-Rad). PBS with 0.005% Tween 20, pH 7.4, was used as running buffer throughout, and kinetics were measured at 25 °C.

Anti-F4/80 VHH versus recombinant F4/80 protein.

NTA-covered HTG chip (Bio-Rad) was activated by 10 mM NiSO4 injection at 30 µL/min for 120 s. Then anti-F4/80 VHHs at a concentration of 25 nM were immobilized to the surface at flow rate 30 µL/min for 300 s in vertical orientation. Immobilization level was 416–452 RU. Signal was stabilized by injection of running buffer at 100 µL/min for 60 s with dissociation value set to 2,400 s first in a vertical and then in a horizontal direction. Recombinant F4/80 was injected at serial dilutions 200–12.5 nM at the speed of 70 µL/min for 345 s, and dissociation was measured for 3,600 s. Sensogram for the antibody having the highest affinity is shown in Fig. S2. Kinetic values are shown in Table S1.

A separate batch of anti-F4/80 VHHs was biotinylated, and its affinity of interaction was measured using neutravidin-coated chip.

Biotinylated anti-F4/80 VHHs at a concentration of 5 nM was immobilized at the surface of a neutravidin-coated NLC chip (Bio-Rad) at a flow rate of 30 µL/min for 300 s in the vertical orientation. Unbound VHHs were removed by injection of 1 M NaCl at 100 µL/min for 30 s in the vertical orientation. Immobilization level was 640–627 RU. Chip orientation was then changed to horizontal, and signal was stabilized by injection of running buffer at 100 µL/min for 60 s with dissociation value set to 3,600 s. Recombinant F4/80 was injected at serial dilutions 200–12.5 nM at the maximum speed—100 µL/min for 245 s—and dissociation was measured for 3,600 s. Sensogram for the antibody having the highest affinity (the same as in the previous experiment) is shown in Fig. S6. Kinetic values are shown in Table S1.

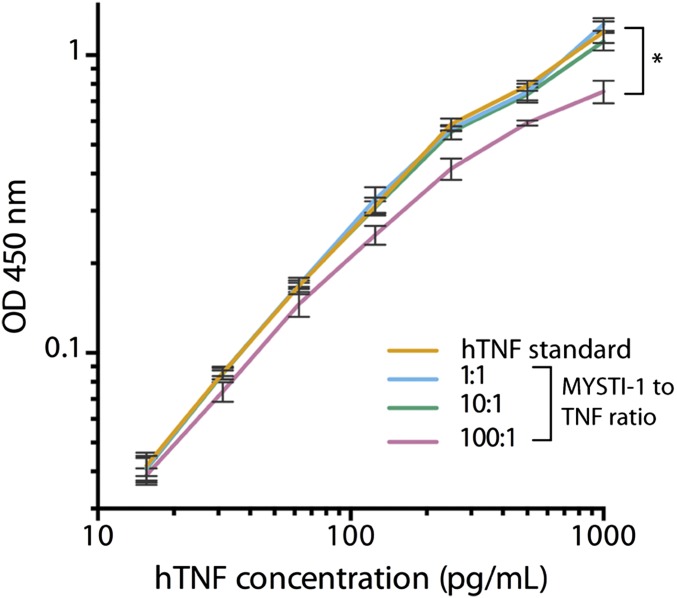

Fig. S6.

MYSTI-1 preincubation with hTNF does not interfere with hTNF detection by ELISA in physiologically relevant ratios. hTNF was incubated with MYSTI at 1:1, 10:1, and 100:1 ratios and compared with hTNF standard by ELISA. (*P < 0.05.)

Bispecific antibodies versus recombinant TNF.

Recombinant hTNF was expressed in E. coli and purified as described previously (47). A total of 50 nM of MYSTI-1 or STI-1 was immobilized on a ProteOn GLC sensor chip (Bio-Rad) using standard amine-coupling chemistry. Next, five analyte concentrations in twofold dilutions (hTNF: 50–3 nM) were injected into the six analyte channels orthogonal to the ligand channels. Thus, all hTNF dilutions reacted simultaneously with bispecific antibody in a single injection. Running buffer was injected into the sixth analyte channel, which was used as a reference. The data were analyzed and fitted to a 1:1 Langmuir interaction model by ProteOn Manager software (Bio-Rad). At least three independent experiments were performed for each antibody.

A total of 100 nM of hTNF were immobilized on a ProteOn GLC sensor chip (Bio-Rad) using standard amine-coupling chemistry. Next, five analyte concentrations in twofold dilutions (MYSTI-2: 200–12.5 nM) were injected into the six analyte channels orthogonal to the ligand channels. Thus, all antibody dilutions reacted simultaneously with hTNF in a single injection. Running buffer was injected into the sixth analyte channel, which was used as a reference. The data were analyzed and fitted to a 1:1 Langmuir interaction model by ProteOn Manager software (Bio-Rad). At least three independent experiments were performed.

Simultaneous interaction of bispecific antibodies with hTNF and F4/80.

To analyze the ability of MYSTI-2 to simultaneously interact with its two targets, recombinant F4/80 was immobilized on a GLC chip as described previously. MYSTI-2 was injected in a vertical direction at 30 µL/min for 800 s at a concentration of 250 nM. Level of immobilization was 200 RU. Then hTNF was injected in the horizontal orientation at serial dilutions 200–12.5 nM at the maximum speed—100 µL/min for 245 s—and dissociation was measured for 3,600 s. A sensogram is shown in Fig. S5.

Cytotoxic Assay.

L929 cells were plated in 96-well culture plates at 5,000 cells/well. Recombinant hTNF and Actinomycin D (Sigma-Aldrich, A5156) were added at constant concentrations of 100 U/mL and 4 μg/mL, respectively. Bispecific antibodies were applied at serial dilutions 1 µM–2 pM. After 24 h of incubation, 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT, Sigma-Aldrich, M5655) was added at a concentration of 4 μg/mL. After 24 h, formazan crystals were solubilized in 10% wt/vol SDS solution in DMSO, and optical density was measured at 540 nm with a 492-nm reference. The percentage of living cells was calculated and fitted to a nonlinear regression curve using GraphPad Prism software. One unit was defined as the amount of TNF inhibitor sufficient to mediate half-maximal protection from cytotoxicity in the presence of 100 U of hTNF. One unit corresponded to approximately 3 ng of protein for MYSTY-1/STI-1 and 10 ng for MYSTI-2/STI-2.

Flow Cytometry Analysis.

Peritoneal cavity cells were isolated and directly stained. Bone marrow was isolated and macrophages were cultured for 10 d in DMEM, 10% (vol/vol) FCS, P/S, and 20% (vol/vol) horse serum with the addition of 30% (vol/vol) of L929 conditioned medium and then detached with ice-cold PBS. Fc-gamma receptor was blocked using anti-Fcgamma receptor antibodies (2.4G2), and then cells were incubated with or without bispecific antibodies at 2.5 µg/mL, washed, and stained in one of three ways: (i) with polyclonal rabbit antibodies to anti-hTNF VHH (produced in house) and then with anti-rabbit IgG (Cell Signaling) FITC or Alexa647-conjugated antibodies; (ii) with mouse anti-His-tag antibodies (Novagen, 70796) and then with anti-mouse IgG PE-conjugated antibody (Cell Signaling); or (iii) with recombinant hTNF and then with anti-hTNF (Miltenyi Biotec, clone: cA2) conjugated with Pacific blue. Cells were counterstained with anti-F4/80 (Clone: C1:A3-1) and FITC-, PE-, or APC-conjugated and anti-CD11b (Clone: M1/70) FITC- or APC-conjugated antibodies. Samples were analyzed on the either FACSAria (BDBiosciences) or Guava EasyCyte 8HT system (Millipore), and data were analyzed using FlowJo (Treestar Inc.).

Analysis of hTNF Sequestration at Macrophage Surface.

Peritoneal cavity macrophages were isolated from TNF humanized mice (31) and plated at 100,000 cells/well on 96-well plates. After 2 h incubation at 37 °C, 5% (vol/vol) CO2 nonadherent cells were removed by rinsing with warm PBS. Cells were further incubated overnight at 37 °C, 5% (vol/vol) CO2. After rinsing with 200 µL of warm DMEM, cells were incubated with MYSTI at a concentration of 2 µg/mL or DMEM for 30 min at 37 °C. After rinsing with 200 µL of warm DMEM, cells were stimulated with LPS (Sigma-Aldrich, L2630) at 100 ng/mL. After 4 h, culture supernatant was collected and hTNF concentration was determined by an hTNF ELISA kit (Invitrogen, CHC1753) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Bone marrow was isolated from TNF humanized mice, and macrophages were cultured for 10 d in DMEM, 10% (vol/vol) FCS, Pen/Strep, 20% (vol/vol) horse serum, 30% (vol/vol) of L929 conditioned medium and then detached with ice-cold PBS, counted, and plated to 96-well plates at 50,000 cells/well. A total of 25 M of MYSTI-1 or anti-TNF VHH, on which MYSTI-1 is based, or vehicle (DMEM) was added to replicate wells containing macrophages. After 30 min, incubation wells were rinsed with PBS. Then cells were stimulated with 100 ng/mL LPS (Sigma-Aldrich, L2630). After 4 h, supernatants were collected and analyzed for the presence of hTNF by cytotoxic test on L929 cells by the protocol similar to the one described above.

ELISA Measurements of the Effects of MYSТI Preincubation on hTNF Concentration in Supernatants.

ELISA using anti-hTNF antibody pair (Invitrogen, CHC1753) was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. MYSTI-1 was added to hTNF standard in 1:1, 10:1, and 100:1 ratio (three replicas each) and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. Then serial dilutions of either hTNF standard or hTNF standard mixed with MYSTI-1 at various ratios were made. TMB (3,3′,5,5′-Tetramethylbenzidine) (eBioscience, 00–4201-56) was used as a substrate, reaction was stopped by adding 1 M H3PO4, and OD was measured at 450 nm. Curves were plotted and analyzed in Prism software (GraphPad).

LPS/D-Galactosamine–Induced Acute Hepatotoxicity Model.

Female TNF humanized mice were randomly distributed in seven groups, three to four mice per group. MYSTI-1 and STI-1 were injected i.p. each at three different doses: 1,500, 750, and 300 U/g, and MYSTI-2 and STI-2 were injected at the dose of 130 U/g (activity previously determined in cytotoxic assay as described above). The latter group received vehicle buffer only (PBS). Thirty minutes later, mice were injected i.p. with 400 ng/g LPS (Sigma-Aldrich, L2630) and 800 µg/g D-Galactosamine (Sigma-Aldrich, G1639). Mice were observed for 800 min after LPS/D-Gal injection. Moribund animals were euthanized, and time of death was noted. Kaplan–Meier survival curves were plotted, and pairwise statistical comparisons of bispecific antibodies and their respective controls using a log-rank (Mantel–Cox) test were performed for each concentration using Prism software (GraphPad). Survival data for MYSTI-1/STI-1 at doses 300 and 1,500 U/g are plotted in Fig. S8.

Discussion

Anti-TNF therapy is currently widely used for multiple autoimmune disorders. However, due to intrinsic nonredundant beneficial functions of TNF, its inhibition is associated with several side effects, such as increased susceptibility to infections (33), secondary autoimmune manifestations (34, 35), and potentially increased risk of lymphoma development (36). Therefore, there is an interest in the development of anti-TNF agents, which would be able to discriminate between mainly pathogenic TNF and “physiological” TNF required for immune homeostasis as more selective reagents may result in fewer side effects.

The apparent nonredundancy of TNF produced by various cellular subsets could be attributed to kinetics, level of the expression, and/or compartmentalization of TNF-producing cells during a particular disease state. Kinetics and the level of expression by various cell types is induced by a variety of stimuli and controlled by distinct intracellular cascades that may differ in specific cell types. For example, macrophages can rapidly produce large TNF quantities upon triggering of Toll-like receptors (TLRs), whereas T cells require other stimuli, such as T-cell receptor engagement, and may produce TNF with different kinetics (37, 38).

Additionally, TNF is initially synthesized by all cells as a type II transmembrane protein that is subsequently cleaved by metalloprotease ADAM17 (TACE) to generate the soluble form of the cytokine. Thus, one of the explanations for the potential difference in the functions of TNF produced by myeloid cells versus T cells could be related to the molecular form of TNF (membrane bound vs. soluble) as their relative levels may differ in these cell types. Obviously, membrane-bound TNF cannot enter the circulation and produce the massive systemic effects observed in several experimental models, including LPS/D-Gal challenge. Indeed, mice producing only membrane-bound TNF are protected from this type of lethal toxicity (39, 40). We have previously provided evidence for the significance of both the cellular source and the molecular form of TNF in the maintenance of the microstructure of lymphoid tissues (20). Thus, cell-type–restricted TNF blockade may selectively disrupt certain signaling circuits deleterious for the host, but not necessarily neutralize the entire “homeostatic” or protective TNF signaling.

Myeloid cells are critical players in many autoimmune diseases, found in large quantities at the effector sites, and one of the major producers of TNF in the body. Taking this into account, a possible improvement of existing anti-TNF therapeutic options by selective inhibition of TNF produced by macrophages appears reasonable. A recent study demonstrated that for the resistance to Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in mice T-cell–derived TNF appears critical and nonredundant for immune protection (41). This is consistent with the mode of protection through the formation of bactericidal granulomas whose structural integrity depends on TNF produced by T cells, presumably in membrane-bound form (41, 42). In both humans and mice, systemic anti-TNF treatment is known to affect granuloma integrity and may cause reactivation of latent disease (43).

The strategy developed in our study employs targeting TNF-neutralizing antibody to the macrophage surface via interaction with membrane protein F4/80. Binding to the surface molecule could induce internalization of antibody and/or induce intracellular signaling events via F4/80. Potentially, such antibody may also bind transmembrane TNF on the surface of macrophages and thus mediate an anti-inflammatory effect by the mechanism of reverse TNF signaling (44). Regardless of the mechanism, our in vivo and in vitro experiments indicate that binding of antibody per se does not activate macrophages as determined by TNF production. However, in primary macrophages prepared from TNF humanized mice, MYSTI (but not STI) can bind and retain TNF on the surface of macrophages, preventing its bioavailability. In vivo administration of MYSTI before LPS challenge resulted in a dramatic reduction in LPS-induced hTNF serum levels in humanized mice with STI having appreciably smaller effect. Interestingly, MYSTI administration blocked very early TNF production by peritoneal macrophages (Fig. S9). Most importantly, MYSTI can block in vivo TNF activity during acute septic shock more efficiently than the control antibody representing a systemic TNF inhibitor.

Altogether, we propose a novel anti-cytokine therapeutic strategy based on selective inhibition of a cytokine from restricted cellular subsets known to be the main source of pathogenic activity in disease. In the future it will be interesting to assess the efficacy of such reagents (perhaps targeting other proinflammatory cytokines) in relevant chronic disease models, such as experimental arthritis, colitis, and EAE.

Materials and Methods

Mice.

As recombinant hTNF inhibitors with the sole exception of Etanercept do not bind murine TNF with sufficient affinity to block its biological effects, we have generated human TNF knock-in mice here designated as TNF humanized mice (31). In these mice, lacking murine TNF, human TNF mediates protective and pathogenic functions and could be neutralized with the entire panel of available anti-TNF drugs. hTNF KI mice were bred at the Animal Breeding Facility of Shemyakin & Ovchinnikov Institute of Bioorganic Chemistry, Puschino, Moscow Region, Russia, and housed under specific pathogen free conditions on 12 h light/dark cycle at room temperature. All animal procedures were approved by the Scientific Council of the Engelhardt Institute of Molecular Biology.

Design, Expression, and Purification of MYSTI and STI Recombinant Antibodies.

MYSTI and STI were generated using standard molecular cloning methods, expressed in E. coli and purified by immobilized metal ion affinity chromatography. Detailed procedures are described in SI Materials and Methods. Calculated molecular masses for MYSTI-1, STI-1, MYSTI-2, and STI-2 were 45, 42, 35, and 36 kDa; pIs were 6.8, 6.2, 8.6, and 8.1, respectively. Average yield was around 1 mg/L for MYSTI-1/STI-1 and around 50 mg/L for MYSTI-2/STI-2. All proteins were stable in solution at 4 °C for at least 1 mo.

hTNF Interaction Assay by SPR.

SPR experiments were performed using the ProteOn XPR36 system (Bio-Rad). MYSTI-1 and STI-1 were immobilized on a sensor chip by amine coupling, and then serial dilutions of hTNF were injected as analyte. MYSTI-2 was applied as analyte over immobilized hTNF. Further details can be found in SI Materials and Methods.

Cytotoxic Assay.

Activity of MYSTI and STI in inhibiting TNF-mediated cytotoxicity was analyzed on L929 cell line. Detailed procedures are described in SI Materials and Methods.

Flow Cytometry Analysis.

Peritoneal cavity cells and bone-marrow–derived macrophages from C57BL/6 mice were incubated with MYSTI or STI or culture media, then with or without recombinant hTNF, and stained for F4/80, for CD11b, and for either bound recombinant antibodies or hTNF. Samples were analyzed on FACSAria (BD Biosciences) or Guava EasyCyte 8HT system (Millipore), and data were analyzed using FlowJo (Treestar Inc.). Details of the experimental procedures and used antibodies can be found in SI Materials and Methods.

Analysis of Sequestration of hTNF on Macrophage Surface.

Bone-marrow–derived macrophages from TNF humanized mice (26) or peritoneal cavity cells enriched for macrophages were incubated with or without MYSTI or STI or anti-TNF VHH, washed, and stimulated with LPS. hTNF concentration in supernatants was determined by ELISA or by cytotoxic assay. A detailed description of the experimental design and procedures is provided in SI Materials and Methods.

LPS/D-Galactosamine–Induced Acute Hepatotoxicity Model.

TNF humanized mice were maintained in a specific pathogen-free (SPF) facility. All animal experiments were performed in accordance with local ethical guidelines. Mice received 300, 750, and 1,500 U/g (activity was measured in cytotoxic assay) of either MYSTI-1 or STI-1 or vehicle buffer followed 30 min later by an otherwise lethal dose of LPS/D-Gal. In a separate set of experiments mice received 130 U/g of either MYSTI-2 or STI-2 or vehicle buffer and LPS/D-Gal injection 30 min later. Kaplan–Meier survival curves were plotted and pairwise statistical comparison of MYSTI and STI was performed for each concentration.

LPS Stimulation.

TNF humanized mice received 25 µg of MYSTI-2 or STI-2 or vehicle buffer followed 30 min later by 10 µg of LPS. One hour later, peritoneal cavity cells and blood sera were collected. Cells were stained for surface MYSTI and analyzed by flow cytometry, and levels of hTNF in sera were measured by ELISA.

Statistical Analyses.

Differences in Kaplan–Meier survival curves were analyzed by the log-rank (Mantel–Cox) test; other statistical comparisons were conducted using an unpaired two-tailed (Student’s) t test. All statistical analyses were done using Prism software (GraphPad). Differences were considered significant when P values were <0.05.

Acknowledgments

We thank K. Horn, D. Schlienz, D. Shvarev, E. Shilov, and E. Vasilenko for their help with the experiments and A. Sazykin for recombinant hTNF purification. This work was supported by Russian Science Foundation Grant 14-50-00060 (Figs. 1 A and B, 3, and 4; and Figs. S4 and S7–S9); Russian Ministry of Science and Education Grant 14.Z50.31.0008; Russian Foundation for Basic Research Grant 14-04-01656; and Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft Grants NE 1466/2 and SFB877, Project A1.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The sequences reported in this paper have been deposited in the GenBank database (accession nos. KU677977, KU677978, KU695528, and KU695529).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1520175113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Brennan FM, Maini RN, Feldmann M. TNF alpha: A pivotal role in rheumatoid arthritis? Br J Rheumatol. 1992;31(5):293–298. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/31.5.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Braun J, et al. Use of immunohistologic and in situ hybridization techniques in the examination of sacroiliac joint biopsy specimens from patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38(4):499–505. doi: 10.1002/art.1780380407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reinecker HC, et al. Enhanced secretion of tumour necrosis factor-alpha, IL-6, and IL-1 beta by isolated lamina propria mononuclear cells from patients with ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. Clin Exp Immunol. 1993;94(1):174–181. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1993.tb05997.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sharief MK, Hentges R. Association between tumor necrosis factor-alpha and disease progression in patients with multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 1991;325(7):467–472. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199108153250704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mussi A, et al. Serum TNF-alpha levels correlate with disease severity and are reduced by effective therapy in plaque-type psoriasis. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 1997;11(3):115–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koski H, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha and receptors for it in labial salivary glands in Sjögren’s syndrome. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2001;19(2):131–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reimund JM, et al. Mucosal inflammatory cytokine production by intestinal biopsies in patients with ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. J Clin Immunol. 1996;16(3):144–150. doi: 10.1007/BF01540912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maini RN, et al. Therapeutic efficacy of multiple intravenous infusions of anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha monoclonal antibody combined with low-dose weekly methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41(9):1552–1563. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199809)41:9<1552::AID-ART5>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Dullemen HM, et al. Treatment of Crohn’s disease with anti-tumor necrosis factor chimeric monoclonal antibody (cA2) Gastroenterology. 1995;109(1):129–135. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90277-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Braun J, et al. Treatment of active ankylosing spondylitis with infliximab: A randomised controlled multicentre trial. Lancet. 2002;359(9313):1187–1193. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)08215-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chaudhari U, et al. Efficacy and safety of infliximab monotherapy for plaque-type psoriasis: A randomised trial. Lancet. 2001;357(9271):1842–1847. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)04954-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mariette X, et al. Inefficacy of infliximab in primary Sjögren’s syndrome: Results of the randomized, controlled Trial of Remicade in Primary Sjögren’s Syndrome (TRIPSS) Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50(4):1270–1276. doi: 10.1002/art.20146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.The Lenercept Multiple Sclerosis Study Group and The University of British Columbia MS/MRI Analysis Group TNF neutralization in MS: Results of a randomized, placebo-controlled multicenter study. Neurology. 1999;53(3):457–465. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ramos-Casals M, et al. Autoimmune diseases induced by TNF-targeted therapies: Analysis of 233 cases. Medicine (Baltimore) 2007;86(4):242–251. doi: 10.1097/MD.0b013e3181441a68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anolik JH, et al. Cutting edge: Anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy in rheumatoid arthritis inhibits memory B lymphocytes via effects on lymphoid germinal centers and follicular dendritic cell networks. J Immunol. 2008;180(2):688–692. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.2.688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mohan AK, Coté TR, Siegel JN, Braun MM. Infectious complications of biologic treatments of rheumatoid arthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2003;15(3):179–184. doi: 10.1097/00002281-200305000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pfeffer K. Biological functions of tumor necrosis factor cytokines and their receptors. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2003;14(3-4):185–191. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6101(03)00022-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grivennikov SI, et al. Distinct and nonredundant in vivo functions of TNF produced by t cells and macrophages/neutrophils: Protective and deleterious effects. Immunity. 2005;22(1):93–104. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kruglov AA, Lampropoulou V, Fillatreau S, Nedospasov SA. Pathogenic and protective functions of TNF in neuroinflammation are defined by its expression in T lymphocytes and myeloid cells. J Immunol. 2011;187(11):5660–5670. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tumanov AV, et al. Cellular source and molecular form of TNF specify its distinct functions in organization of secondary lymphoid organs. Blood. 2010;116(18):3456–3464. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-10-249177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gooz M. ADAM-17: The enzyme that does it all. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2010;45(2):146–169. doi: 10.3109/10409231003628015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scheller J, Chalaris A, Garbers C, Rose-John S. ADAM17: A molecular switch to control inflammation and tissue regeneration. Trends Immunol. 2011;32(8):380–387. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2011.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kinne RW, Bräuer R, Stuhlmüller B, Palombo-Kinne E, Burmester GR. Macrophages in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res. 2000;2(3):189–202. doi: 10.1186/ar86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Austyn JM, Gordon S. F4/80, a monoclonal antibody directed specifically against the mouse macrophage. Eur J Immunol. 1981;11(10):805–815. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830111013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gordon S, Hamann J, Lin H-H, Stacey M. F4/80 and the related adhesion-GPCRs. Eur J Immunol. 2011;41(9):2472–2476. doi: 10.1002/eji.201141715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kruglov A, et al. Mice in which human TNF is mediating both beneficial and deleterious functions: A model comparison of different blockade strategies. Cytokine. 2008;43(3):271. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Coppieters K, et al. Formatted anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha VHH proteins derived from camelids show superior potency and targeting to inflamed joints in a murine model of collagen-induced arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(6):1856–1866. doi: 10.1002/art.21827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Plagmann I, et al. Transglutaminase-catalyzed covalent multimerization of Camelidae anti-human TNF single domain antibodies improves neutralizing activity. J Biotechnol. 2009;142(2):170–178. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2009.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Conrad U, et al. ELPylated anti-human TNF therapeutic single-domain antibodies for prevention of lethal septic shock. Plant Biotechnol J. 2011;9(1):22–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2010.00523.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tillib SV, et al. Single-domain antibody-based ligands for immunoaffinity separation of recombinant human lactoferrin from the goat lactoferrin of transgenic goat milk. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2014;949–950:48–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2013.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Olleros ML, et al. Control of mycobacterial infections in mice expressing human tumor necrosis factor (TNF) but not mouse TNF. Infect Immun. 2015;83(9):3612–3623. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00743-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kruglov AA, et al. Modalities of experimental TNF blockade in vivo: Mouse models. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2011;691:421–431. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-6612-4_44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Keane J, et al. Tuberculosis associated with infliximab, a tumor necrosis factor alpha-neutralizing agent. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(15):1098–1104. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Williams EL, Gadola S, Edwards CJ. Anti-TNF-induced lupus. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2009;48(7):716–720. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kep080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Korkmaz U, et al. Adalimumab-induced psoriasis in a patient with Crohn’s disease. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2013;32(2):135–136. doi: 10.1007/s12664-012-0281-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wolfe F, Michaud K. Lymphoma in rheumatoid arthritis: The effect of methotrexate and anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy in 18,572 patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50(6):1740–1751. doi: 10.1002/art.20311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Falvo JV, Tsytsykova AV, Goldfeld AE. Transcriptional control of the TNF gene. Curr Dir Autoimmun. 2010;11:27–60. doi: 10.1159/000289196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shebzukhov YV, et al. Dynamic changes in chromatin conformation at the TNF transcription start site in T helper lymphocyte subsets. Eur J Immunol. 2014;44(1):251–264. doi: 10.1002/eji.201243297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ruuls SR, et al. Membrane-bound TNF supports secondary lymphoid organ structure but is subservient to secreted TNF in driving autoimmune inflammation. Immunity. 2001;15(4):533–543. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00215-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Alexopoulou L, et al. Transmembrane TNF protects mutant mice against intracellular bacterial infections, chronic inflammation and autoimmunity. Eur J Immunol. 2006;36(10):2768–2780. doi: 10.1002/eji.200635921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Allie N, et al. Prominent role for T cell-derived tumour necrosis factor for sustained control of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Sci Rep. 2013;3:1809. doi: 10.1038/srep01809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Garcia I, et al. Roles of soluble and membrane TNF and related ligands in mycobacterial infections: Effects of selective and non-selective TNF inhibitors during infection. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2011;691:187–201. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-6612-4_20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Flynn JL, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha is required in the protective immune response against Mycobacterium tuberculosis in mice. Immunity. 1995;2(6):561–572. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90001-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Eissner G, et al. Reverse signaling through transmembrane TNF confers resistance to lipopolysaccharide in human monocytes and macrophages. J Immunol. 2000;164(12):6193–6198. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.12.6193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Arbabi Ghahroudi M, Desmyter A, Wyns L, Hamers R, Muyldermans S. Selection and identification of single domain antibody fragments from camel heavy-chain antibodies. FEBS Lett. 1997;414(3):521–526. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)01062-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tillib SV, Ivanova TI, Vasilev LA. Fingerprint-like analysis of “nanoantibody” selection by phage display using two helper phage variants. Acta Naturae. 2010;2(3):85–93. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shingarova LN, et al. Human tumor necrosis factor mutants: Preparation and some properties. Bioorg Khim. 1996;22(4):243–251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]