Significance

The therapeutic potential of protein-based genome editing is dependent on the delivery of proteins to appropriate intracellular targets. Here we report that combining bioreducible lipid nanoparticles and negatively supercharged Cre recombinase or anionic Cas9:single-guide (sg)RNA complexes drives the self-assembly of nanoparticles for potent protein delivery and genome editing. The design of bioreducible lipids facilitates the degradation of nanoparticles inside cells in response to the reductive intracellular environment, enhancing the endosome escape of protein. In addition, modulation of protein charge through either genetic fusion of supercharged protein or complexation of Cas9 with its inherently anionic sgRNA allows highly efficient protein delivery and effective genome editing in mammalian cells and functional recombinase delivery in the rodent brain.

Keywords: genome editing, CRISPR/Cas9, Cre recombinase, protein delivery, lipid nanoparticle

Abstract

A central challenge to the development of protein-based therapeutics is the inefficiency of delivery of protein cargo across the mammalian cell membrane, including escape from endosomes. Here we report that combining bioreducible lipid nanoparticles with negatively supercharged Cre recombinase or anionic Cas9:single-guide (sg)RNA complexes drives the electrostatic assembly of nanoparticles that mediate potent protein delivery and genome editing. These bioreducible lipids efficiently deliver protein cargo into cells, facilitate the escape of protein from endosomes in response to the reductive intracellular environment, and direct protein to its intracellular target sites. The delivery of supercharged Cre protein and Cas9:sgRNA complexed with bioreducible lipids into cultured human cells enables gene recombination and genome editing with efficiencies greater than 70%. In addition, we demonstrate that these lipids are effective for functional protein delivery into mouse brain for gene recombination in vivo. Therefore, the integration of this bioreducible lipid platform with protein engineering has the potential to advance the therapeutic relevance of protein-based genome editing.

Therapeutic proteins are an expanding class of biologics that can be used for specific and transient manipulation of cell function (1). Recently, the programmable nuclease Cas9 and other genome-editing proteins have been shown to mediate editing of disease-associated alleles in the human genome, facilitating new treatments for many genetic diseases (2–5). The transient nature of therapeutic protein delivery makes it an attractive method for delivery of genome-editing proteins (4). A challenge to efficient delivery of genome-editing proteins is their proteolytic instability and poor membrane permeability (6). Developing delivery vehicles to transport active protein to their intracellular target site is thus essential to advance protein-based genome editing. The last few years have witnessed tremendous progress in designing nanocarriers for intracellular protein delivery (7, 8). However, the lack of an effective, general approach to load protein into a stable nanocomplex and the inefficient release of protein from endocytosed nanoparticles pose challenges for protein delivery (6). There remains a great demand for the development of novel platforms that efficiently assemble protein into nanoparticles for intracellular delivery while maintaining biological activity of the protein.

Recently, we developed lipid-like nanoparticles that can be synthesized in a combinatorial manner as highly effective protein and gene delivery vehicles (9–13). We found that electrostatic self-assembly between lipid and protein is essential to form a stable nanocomplex for protein delivery (11). Further, we demonstrated that the integration of a bioreducible disulfide bond into the hydrophobic tail of the lipid enhances efficiency of small interfering RNA (siRNA) delivery (14), due to the improved endosomal escape and cargo release following lipid degradation in the reductive intracellular environment. Meanwhile, we engineered supercharged proteins shown to enhance protein delivery by fusing superpositively charged GFP to a protein of interest (15–17) and using cationic-lipid mediated delivery of supernegatively charged proteins (4). We hypothesized that combining cationic bioreducible lipids and supernegatively charged proteins would drive electrostatic self-assembly of a supramolecular nanocomplex to deliver the genome-editing protein (Fig. 1). In addition, we hypothesized that the bioreduction of these lipid/protein nanocomplexes inside cells in response to the reductive intracellular environment (e.g., high concentration of glutathione) could facilitate endosomal escape of the protein cargo, enabling protein to enter the nucleus for effective genome editing.

Fig. 1.

Design of bioreducible lipid-like materials and negatively supercharged protein for effective protein delivery and genome editing.

In this study, we synthesized 12 bioreducible lipids by a Michael addition of primary or secondary amines and an acrylate that features a disulfide bond and a 14-carbon hydrophobic tail (Fig. 2). Our combinatorial synthesis allows facile generation of lipids with chemically diverse head groups, enabling study of the structure–activity relationship of the head groups. We fused several negatively supercharged GFP variants to Cre recombinase (4) with the aim of enhancing the electrostatic interaction between protein and cationic lipid. Our work also demonstrates that the anionic ribonuceloprotein complex formed between Cas9 and single-guide RNA (sgRNA) (2) is able to form a nanocomplex with our bioreducible lipids for efficient genome editing in human cells. We find that the bioreducible lipids can efficiently deliver active negatively charged proteins complexes with a higher efficiency than commercially available lipids. Our bioreducible lipids enable Cre- and Cas9:sgRNA-mediated gene recombination and gene knockout with efficiencies higher than 70% in cultured human cells. Finally, we demonstrate that these lipid nanoparticles can deliver genome-editing protein into the mouse brain for effective DNA recombination in vivo.

Fig. 2.

Synthesis of bioreducible lipid-like materials. (A) Synthesis route and lipid nomenclature. (B) Chemical structures of amines used as head groups for lipid synthesis.

Results and Discussion

Lipid Synthesis and Nanoparticle Formulation.

The bioreducible lipids were synthesized by heating an amine and acrylate in Teflon-lined glass screw-top vials for 48 h, and the crude products were purified using flash chromatography. The lipids were named with amine number (Fig. 2) and O14B; the latter indicates the carbon number of the hydrophobic tail and the bioreducible nature of lipids. All lipids were formulated with cholesterol, 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (DOPE), and C16-PEG2000-ceramide (SI Materials and Methods) for the following studies.

Screening Lipids for Protein Delivery.

To demonstrate the necessity of the negative charge on the protein for assembling a nanocomplex with cationic lipids, we first fused a negatively supercharged GFP variant, (–27)GFP, to Cre recombinase and generated (–27)GFP-Cre. The fusion of (–27)GFP with Cre allows the study of protein uptake by analysis of intracellular GFP fluorescence, as well as a functional readout of Cre activity. In this study, we used HeLa-DsRed cells that express red fluorescent DsRed on Cre-mediated gene recombination to evaluate (–27)GFP-Cre delivery efficiency using different lipids. After delivery of protein-containing nanoparticles, the cellular uptake of different (–27)GFP-Cre/lipid complexes was quantified by counting GFP-positive cells. As shown in Fig. 3A, treatment of (–27)GFP-Cre (25 nM protein) without lipids showed a very low ratio of GFP-positive cells, indicating that the protein is not able to enter cells without cationic lipid. Interestingly, the proportion of GFP-positive cells after treatment was dependent on the nature of the lipid headgroup used in the delivery. Seven of the 12 lipids delivered (–27)GFP-Cre with a higher efficiency than that of a commercial lipid reagent, Lipofectamine 2000 (LPF2K). Complexation of (–27)GFP-Cre with lipids 6-O14B, 7-O14B, and 8-O14B resulted in more than 50% GFP-positive cells. In particular, 8-O14B (chemical structure shown in Figs. 1 and 2) delivered (–27)GFP-Cre in the highest efficiency among the 12 lipids, with more than 80% GFP-positive cells observed after treatment.

Fig. 3.

Cellular uptake (A) and DsRed expression profile (B) of HeLa-DsRed cells treated with (–27)GFP-Cre alone or different lipid complexes. For the cellular uptake study, cells were treated with complexes of 25 nM protein and 2 µg/mL lipid for 6 h, and DsRed expression was quantified 24 h after delivery. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 compared with treatment with protein alone (no lipid).

Lipid and (–27)GFP-Cre Binding Study.

The complexation of 8-O14B and (–27)GFP-Cre to form nanoparticles was examined using dynamic light scattering (DLS; Table S1) analysis and transmission electronic microscopy (TEM) imaging (Fig. S1). The size of 8-O14B nanoparticles increased from 100 to 240 nm with the addition of (–27)GFP-Cre (Table S1), indicating formation of a nanocomplex between the lipid and (–27)GFP-Cre. ζ Potential measurement indicated the surface charge decrease of 8-O14B from 7 to –18 mV, confirming that the electrostatic binding of (–27)GFP-Cre and 8-O14B neutralized the positive charge of the lipid nanoparticles. In contrast, the addition of the same concentration of Cre protein [without the supernegative (–27)GFP fusion] had a negligible effect on the size and surface charge of the 8-O14B nanoparticles (Table S1). The DLS study indicates the necessity of electrostatic attraction between protein and lipid for nanoparticle loading.

Table S1.

Size and ζ potential of representative lipid and lipid/protein nanoparticles measured by DLS

| Sample | Size (nm) | ζ potential (mV) |

| 8-O14B | 106.6 ± 2.5 | 7.1 ± 1.8 |

| 8-O14B/(–27)GFP-Cre | 241.2 ± 2.6 | −18.5 ± 1.5 |

| 8-O14B/Cre | 124.6 ± 3.5 | 5.0 ± 2.7 |

| 3-O14B | 74.7 ± 0.2 | 12.5 ± 2.6 |

| 3-O14B/Cas9:sgRNA | 292.2 ± 15.4 | −9.1 ± 2.5 |

Fig. S1.

TEM image of (–27)GFP-Cre/8-O14B nanoparticles; 25 nM protein and 2 µg/mL lipid were mixed in 25 mM phosphate buffer (pH = 7.4) for TEM imaging. (Scale bar, 100 nm.)

Circular dichroism (CD) spectra showed negligible change in the secondary structure of (–27)GFP-Cre in the presence of 8-O14B (Fig. S2A). Moreover, no shift in the wavelength for GFP fluorescence from (–27)GFP-Cre was observed, further confirming the retention of the native structure of (–27)GFP-Cre after complexation with bioreducible lipids (Fig. S2B).

Fig. S2.

Lipid and protein binding study. (A) CD. (B) Fluorescence spectra of (–27)GFP-Cre in the presence and absence of 8-O14B nanoparticles; 0.5 µM (–27)GFP-Cre protein was mixed with 24 µg 8-O14B nanoparticles in 25 mM phosphate buffer (pH = 7.4) for CD and GFP fluorescence (excitation: 480 nm) spectra measurement.

Endocytosis and Endosome Escape of Lipid/Protein Nanoparticles.

We previously reported that the lipid-like nanoparticles deliver protein mainly through an endocytosis-dependent pathway (11). To probe the detailed mechanism of bioreducible lipid to deliver protein, we treated HeLa-DsRed cells with 8-O14B/(–27)GFP-Cre complexes in the presence of endocytosis inhibitors. As shown in Fig. S3, both sucrose, a clathrin-mediated endocytosis inhibitor, and the cholesterol-depleting agent methyl-β-cyclodextrin (M-β-CD), strongly suppressed cellular uptake of 8-O14B/(–27)GFP-Cre nanoparticles. In addition, treatment of the dynamin II inhibitor dynasore significantly reduced the delivery of (–27)GFP-Cre. In contrast, an inhibitor of caveolin-mediated endocytosis, nystatin, had minimal effect on the delivery of (–27)GFP-Cre. These data indicate that 8-O14B/(–27)GFP-Cre nanoparticles enter cells mainly through clathrin-mediated endocytosis, in which plasma cholesterol and dynamin also play roles in the uptake of the lipid/protein nanocomplex.

Fig. S3.

Cellular uptake of (–27)GFP-Cre/8-O14B nanoparticle was suppressed by endocytosis inhibitors. HeLa-DsRed cells were pretreated with sucrose (450 mM), M-β-CD (2 mM), dynasore (80 µM), or nystatin (100 nM) for 1 h before exposed to 25 nM (–27)GFP-Cre nanoparticles. ***P < 0.001 compared with normalized control.

The intracellular trafficking of 8-O14B/(–27)GFP-Cre nanoparticles after entering cells was studied by visualizing subcellular (–27)GFP-Cre accumulation and protein localization using confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) imaging. As shown in Fig. 4, treatment of HeLa-DsRed cells with (–27)GFP-Cre alone (12.5 nM protein) showed no (–27)GFP delivery, which was consistent with the cellular uptake study (Fig. 2A). Treatment with 8-O14B/(–27)GFP-Cre nanocomplexes (12.5 nM protein) showed significant accumulation of GFP fluorescence in the cytosol and nucleus, with a low level of colocalization with endosome/lysosome, indicating the efficient endosome escape of 8-O14B/(–27)GFP-Cre nanoparticles. The inherent nuclear localization signal presented on the Cre recombinase enables the accumulation of (–27)GFP-Cre in nuclei for effective gene recombination (18).

Fig. 4.

CLSM images of HeLa-DsRed cells treated with (–27)GFP-Cre alone (12.5 nM protein) or complexed with 1 µg/mL lipid 8-O14B for 6 h. Endosome/lysosome was stained using LysoTracker Red. (Scale bar, 20 µm.)

Cre Protein Delivery-Mediated Gene Recombination.

The resulting DsRed expression from successful Cre-mediated recombination in (–27)GFP-Cre lipid nanoparticle-treated HeLa-DsRed cells was analyzed 24 h after protein delivery. As shown in Fig. 3B, (–27)GFP-Cre alone is incapable of inducing DsRed expression. Treatment of cells with nanoparticles formulated from (–27)GFP-Cre and the seven lipids that efficiently delivered (–27)GFP-Cre in the cellular uptake study (Fig. 3A) showed comparable or higher percentages of DsRed-positive cells than that of LPF2K. The best lipid for protein delivery identified in the cellular uptake analysis, 8-O14B, delivered (–27)GFP-Cre to a high efficiency, resulting in 80% DsRed-positive cells. In addition, 8-O14B/(–27)GFP-Cre delivery resulted in significantly enhanced recombination efficiency compared with treatment with Lipofectamine RNAiMax (4), indicating that efficient escape of 8-O14B/(–27)GFP-Cre from the endosome facilitates improved Cre-mediated gene recombination.

Delivery of (–27)GFP-Cre/8-O14B induced DsRed expression in a protein concentration-dependent manner. When the concentration of (–27)GFP-Cre delivered to cells was increased from 6.25 to 25 nM, the DsRed-positive cells increased from 10% to 80% (Fig. 5A), and no Ds-Red positive cells were observed when treatment was performed with uncomplexed protein, demonstrating the necessity of lipid for an effective Cre-mediated gene recombination. Furthermore, HeLa-DsRed cells treated with 8-O14B/(–27)GFP-Cre nanoparticles retained viability above 85% at all protein concentrations studied (0–50 nM) as measured by a MTT assay (Fig. S4), indicating that the 8-O14B lipid is highly biocompatible and displays low cytotoxicity.

Fig. 5.

(A) Protein dose-dependent DsRed expression of HeLa-DsRed cells treated with (–27)GFP-Cre in the absence and presence of lipid 8-O14B (2 µg/mL). (B) Tail length of bioreducible lipid determines Cre recombination efficiency. HeLa-DsRed cells were treated with 25 nM (–27)GFP-Cre complexed with 2 µg/mL lipid derived from amine 8 featuring different hydrophobic tail length. ***P < 0.001 compared with 8-O14B.

Fig. S4.

Cytotoxicity assay of (–27)GFP-Cre/8-O14B nanoparticles. HeLa-DsRed cells were treated with the nanocomplex of 2 µg/mL lipid and increased concentration of protein for 24 h, followed by cell viability measurement using MTT assay.

We next studied the chemical structure–activity relationship of the bioreducible lipids for protein delivery, and this study was enabled by our facile, combinatorial lipid synthesis approach. For this purpose, lipids conjugated from amine 8 and acrylates featuring tails with 12, 14, 16, and 18 carbon atoms, were synthesized for (–27)GFP-Cre delivery. All four lipids showed comparable protein encapsulation efficiency, with more than 90% (–27)GFP-Cre encapsulated under the optimized delivery condition using 8-O14B (Fig. S5A). However, these lipids showed quite different capability for protein delivery. Lipids with tails containing 14, 16, or 18 carbons (8-O14B, 8-O16B, or 8-O18B) delivered to more than 90% of cells when 25 nM (–27)GFP-Cre nanoparticles was exposed to HeLa-DsRed cells (Fig. S5B). The percentage of DsRed expressed cells was as high as 80% following these treatments (Fig. 5B). 8-O12B, on the other hand, had the lowest protein delivery efficiency, with less than 20% GFP-positive and DsRed-recombined cells under the same conditions (Fig. S5B and Fig. 5B). These findings demonstrate that lipid nanoparticles with the shorter 12-carbon hydrophobic tail had lower protein delivery efficiency, consistent with our previous observations (11). Taken together, these findings highlight the advantages of using a combinatorial strategy to identify effective protein delivery vehicles.

Fig. S5.

(A) Encapsulation efficiency and (B) intracellular delivery of (–27)GFP-Cre ino HeLa-DsRed cells using lipid with different hydrocarbon tails. See SI Materials and Methods for experimental details. ***P < 0.001 compared with 8-O14B–mediated delivery.

Protein Charge Determines Gene Recombination Efficiency.

To further demonstrate the essential role of the electrostatic binding between lipids and negatively supercharged proteins for an effective protein delivery, Cre recombinase with and without different supernegative GFP fusions were designed and evaluated for their ability to mediate gene recombination. To this end, we fused Cre recombinase to four GFP variants with negative charges of –7, –20, –27, or –30. The negative charge density of negative GFP-fused proteins determines their encapsulation efficiency by 8-O14B nanoparticles. More than 90% of (–27) and (–30)GFP-Cre was encapsulated into 8-O14B (Fig. S6A), whereas less than 30% of (–7) and (–20)GFP-Cre was encapsulated with 8-O14B nanoparticles under the same conditions.

Fig. S6.

(A) Encapsulation efficiency and (B) intracellular delivery of Cre recombinase fused with different supernegative GFP variants ino HeLa-DsRed cells using 8-O14B nanoparticles. See SI Materials and Methods for experimental details. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 compared with the encapsulation of (–27)GFP-Cre.

The higher encapsulation of (–27)GFP-Cre and (–30)GFP-Cre into 8-O14B nanoparticles enhanced protein delivery and gene recombination efficiency of these proteins relative to the (–7) and (–20)GFP-Cre constructs. Analysis of the cellular uptake of different protein/lipid complexes indicated that (–27)GFP-Cre and (–30)GFP-Cre nanoparticle treatment showed higher GFP fluorescence intensity than cells treated with (–7)GFP-Cre and (–20)GFP-Cre (Fig. S6B). In addition, the treatment of HeLa-DsRed cells with the 8-O14B complex of (–27)GFP-Cre or (–30)GFP-Cre both resulted in 80% DsRed-positive cells (Fig. 6), demonstrating a significantly higher gene recombination efficiency than that of (–7)GFP-Cre, (–20)GFP-Cre, or Cre without supernegative GFP fusion delivery (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

The charge density of negatively supercharged protein determines Cre-mediated recombination efficiency. HeLa-DsRed cells were treated with the complex of 8-O14B (2 µg/mL) and 25 nM Cre protein fused to GFP with the charge as indicated. ***P < 0.001 compared with the delivery of (–27) GFP-Cre.

Anionic Cas9:sgRNA Delivery for Genome Modification.

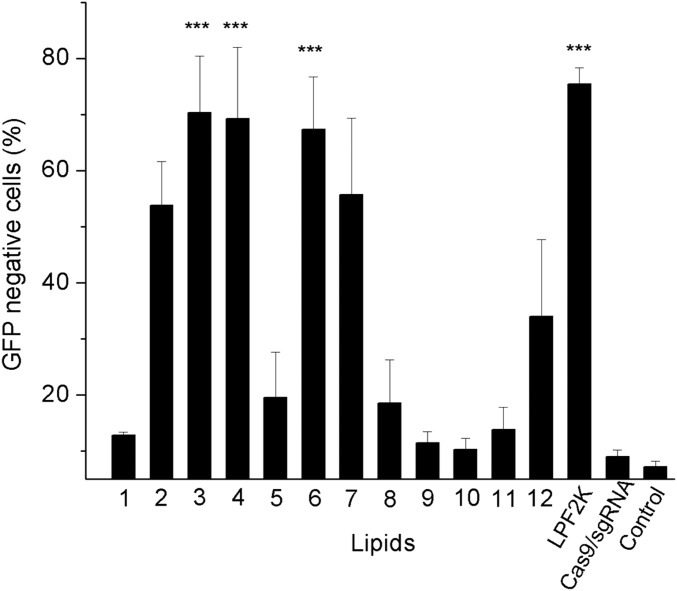

Having demonstrated the success and high efficiency of bioreducible lipids to deliver Cre recombinase for gene recombination, we next investigated whether these lipids are able to deliver the genome-editing protein Cas9 and facilitate Cas9-mediated genetic modification of mammalian cells. CRISPR-associated protein 9 (Cas9) can bind to and cleave a target DNA sequence that is complementary to the first 20 nucleotides of an sgRNA (19). Cas9-induced double-strand breaks could be repaired by nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ) or homology-directed repair (HDR) in mammalian cells, enabling targeted genome editing and cell engineering for the treatment of genetic diseases (3, 20, 21). Two limitations for the use of the Cas9:sgRNA complex for genome editing are delivery into target cells and modification at off-target DNA sites (22–24). We and others have shown that delivery of the Cas9:sgRNA ribonucleoprotein complex results in comparable efficacy and reduced off-target cleavage events compared with traditional plasmid-based delivery methods (4, 25). The ribonucleoprotein complex is anionic, facilitating complexation with cationic nanoparticles without the need for fusion with a supernegatively charged protein. The ability of bioreducible lipids to deliver anionic Cas9:sgRNA complex for genome editing was demonstrated by targeting genomic EGFP reporter gene in HEK cells. The efficient delivery of Cas9:sgRNA and on-target Cas9 cleavage of GFP-expressing HEK cells induce NHEJ in the EGFP reporter gene and result in the loss of cell fluorescence. For this purpose, we treated HEK cells with 25 nM Cas9 and 25 nM EGFP-targeting sgRNA with and without lipid complexation, and the GFP expression profile was analyzed and summarized in Fig. 7. Five of the 12 lipids delivered the Cas9/sgRNA complex and induced the loss of EGFP-positive cells with an efficiency higher than 50%. In particular, lipids 3-O14B, 4-O14B, and 6-O14B showed 70% EGFP expression loss, a comparable genome editing efficiency to that of commercial LPF2K. Meanwhile, no significant EGFP disruption was observed when the cells were treated with Cas9:sgRNA alone, confirming that the delivery of Cas9:sgRNA complex using bioreducible lipids allows effective genome editing. Similarly as with negatively supercharged GFP-Cre lipid complexes, we show that the electrostatic self-assembly of anionic Cas9:sgRNA with cationic lipids forms nanoparticles similar to that of lipid/(–27)GFP-Cre complex as confirmed by DLS analysis of 3-O14B/Cas9:sgRNA nanocomplexes (Table S1). On addition of the Cas9:sgRNA complex, the size of 3-O14B nanoparticles increased from 74 to 292 nm, and the ζ potential of 3-O14B decreased from 12.5 to –9.1 mV, indicating that binding of Cas9:sgRNA neutralized the positive charge of the 3-O14B nanoparticles. The nanoparticle morphology was similarly visualized by TEM imaging, as shown in Fig. S7. Taken together, these results show efficient Cas9-mediated gene editing using bioredicible lipids which efficiently complex with Cas9:sgRNA.

Fig. 7.

Delivery of Cas9:sgRNA complex into cultured human cells for genome editing. GFP stably expressing HEK cells were treated with 25 nM Cas9:sgRNA complex targeting the GFP locus, with and without lipid (6 µg/mL). The GFP KO efficiency was quantified after 3 d. ***P < 0.001 compared with Cas9/sgRNA alone treated cells.

Fig. S7.

TEM image of 3-O14B/Cas9:sgRNA nanoparticle; 50 pmol Cas9:sgRNA complex was mixed with 8 µg 3-O14B in 25 mM phosphate buffer (pH = 7.4) for TEM imaging. (Scale bar, 200 nm.)

In Vivo Cre Delivery for Gene Recombination in Mouse Brain.

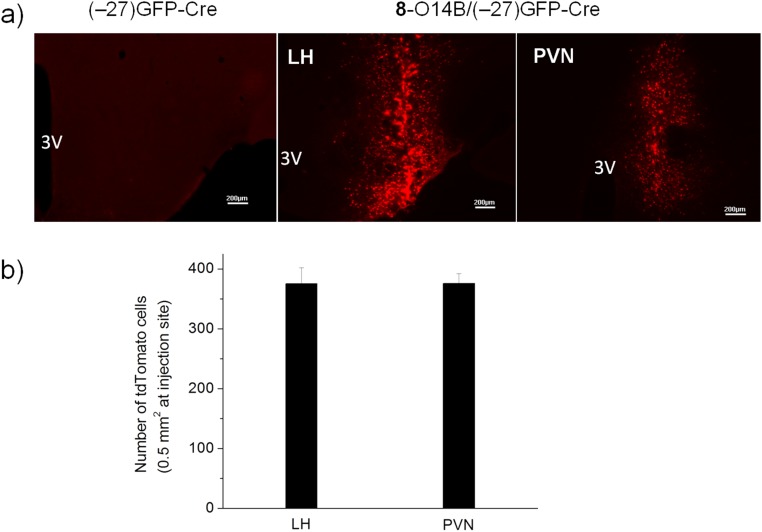

In vivo delivery of genome-editing proteins has the potential to correct a wide range of genetic diseases. Delivering protein for genome modification in the brain would enable the treatment of neurological disorders. In this study, we demonstrate the potency of the bioreducible lipids for brain protein delivery by delivering (–27)GFP-Cre into the mouse brain for Cre-mediated gene recombination. We prepared the (–27)GFP-Cre/8-O14B complex under optimized in vitro conditions and injected the nanocomplexes into the brain of a Rosa26tdTomato mouse. This mouse has a genetically integrated loxP-flanked STOP cassette that prevents the transcription of red fluorescent protein (tdTomato), whereas Cre-mediated gene recombination results in tdTomato expression. We injected the (–27)GFP-Cre/8-O14B complex into the following regions of brain: DM, DG, MD, cortex, BNST, LSV, paraventricular nucleus of hypothalamus (PVN), and lateral hypothalamus (LH). Injection of the (–27)GFP-Cre protein without lipid served as a negative control. Six days following the injection, brain tissues were collected and analyzed for (–27)GFP-Cre delivery and tdTomato expression. As shown in Fig. 8 and Figs. S8 and S9, a strong tdTomato signal was localized in all regions of the brain that received injections. Conversely, no tdTomato expression in the brain was observed for the mouse injected with (–27)GFP-Cre alone. The tdTomato-positive cells in the PVN and LH regions of mouse brain were around 350 in a 0.5-mm2 area at injection sites (Fig. S9). In addition, we found that the (–27)GFP-Cre/8-O14B nanoparticles delivered into brain are confined to the injection site with minimal diffusion (Fig. S10). Taken together, our results showed that by delivering the lipid/protein nanoparticles, it is possible to target an extremely small region in the brain, permitting genome editing in a highly specific neuronal population. This approach could be useful to perform genome editing in vivo to treat neurological diseases because it allows for targeting of specific genes in a local subset of neurons.

Fig. 8.

In vivo delivery of Cre recombinase to mouse brain. Rosa26tdTomato mouse was microinjected with 0.1 µL 50 µM (–27)GFP-Cre alone or the same amount of protein complexed with lipid 8-O14B. After 6 d, the tdTomato expression indicative of Cre-mediated recombination in dorsomedial hypothalamic nucleus (DM; X = +0.20, Y = −1.6, Z = −5.0), mediodorsal thalamic nucleus (MD; X = +0.25, Y = −1.4, Z = −2.2), and bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST; X = +0.9, Y = +0.4, Z = −4.0) was visualized using fluorescent microscopy. (Scale bar, 100 µm.)

Fig. S8.

In vivo delivery of Cre recombinase to mouse brain. Rosa26tdTomato mouse was microinjected with 0.1 µL 50 µM (–27)GFP-Cre alone or the sample amount of protein complexed with lipid 8-O14B. After 6 d, the tdTomato expression indicative of Cre-mediated recombination in dentate gyrus (DG; X = +0.25, Y = −1.5, Z = −2.2), cortex (X = +0.25, Y = −1.4, Z = −1.0), and ventral lateral septal nucleus (LSV; X = +0.8, Y = +0.4, Z = −3.5) was visualized using fluorescent microscopy. (Scale bar, 100 µm.)

Fig. S9.

In vivo delivery of Cre recombinase to hypothalamus of mouse brain. Rosa26tdTomato mouse was microinjected with 0.1 µL 50 µM (–27)GFP-Cre alone or the same amount of protein complexed with lipid 8-O14B. After 6 d, the tdTomato expression indicative of Cre-mediated recombination in hypothalamus was visualized using fluorescence microscopy (A) or counted in 0.5 mm2 at the injection sites of each brain slice (B). (Scale bar, 200 µm.)

Fig. S10.

Accumulation of (–27)GFP-Cre and tdTomato expression in DM (A), MD (B), and BNST (C) following (–27)GFP-Cre/8-O14B nanoparticle injections. (Scale bar, 50 µm in A and B; 100 µm in C.)

SI Materials and Methods

General.

All chemicals used for lipid synthesis were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and directly used as received. All protein constructs were generated from previously reported Cre recombinase and S. pyogenes Cas9 expression plasmids (4). Generation of sgRNA was done using a generic sgRNA expression plasmid as a template for a PCR product containing a T7 promoter adapter sequence, which was then in vitro transcribed according to previous reports (4). HeLa-DsRed and GFP-HEK cells were maintained in DMEM (Sigma-Aldrich) supplemented with 10% FBS (Sigma-Aldrich) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Life Technologies). Nanoparticle size and ζ potential were recorded on ZetaPALS particle size analyzer. TEM images were captured using an FEI Technai Spirit Transmission Electron Microscope.

Lipid Synthesis.

All head amines used for lipid synthesis are commercial available from Sigma-Aldrich. Bioreducible acrylate featuring disulfide bond was synthesized according to our previous report (14). To synthesize lipid, head amine and acrylate were mixed and heated at 1:2.4 molar ratio in Telfon-lined glass screw-top vials for 48 h. The crude product was purified using flash chromatography on silica gel. The lipid structure was confirmed using 1H NMR and electrospray ionization (ESI) MS.

Lipid Nanoparticle Formulation.

Lipid was formulated into nanoparticles for all delivery applications. The as-synthesized lipid was mixed with cholesterol, DOPE, and C16-PEG2000-Ceramide (Avanti Polar Lipids) at a wt/wt ratio of 16:4:1:1. Briefly, lipid, cholesterol, and DOPE were mixed in a chloroform solution in a 0.5-dr vial. The organic solvent was evaporated under vacuum and further dried over night to form a thin layer film on the vial. The lipid film was hydrated using a mixed solution of ethanol/sodium acetate buffer (200 mM, pH = 5.2, vol:vol = 9:1). The above solution was added dropwise to an aqueous solution of C16-PEG2000-ceramide, and the resulted solution was incubated at 37 °C for 30 min before subjecting to dialysis against water or PBS in 3500 molecular weight cut-off (MWCO) cassettes (Pierce/Thermo Scientific).

Expression and Purification of S. pyogenes Cas9 and Negatively Charged GFP-Cre Variants.

E. coli BL21 STAR (DE3)-competent cells (Life Technologies) were transformed with Cas9-nuclear localization signal (NLS)-6xHis (Addgene #62933) encoding the S. pyogenes Cas9 fused with a C-terminal NLS followed by His-tag. The resulting expression strain was inoculated in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth containing 100 mg/mL ampicillin at 37 °C overnight. The cells were diluted 1:100 into the same growth medium and grown at 37 °C to OD600 = ∼0.6. The culture was incubated at 20 °C for 30 min, and isopropyl b-d-1- thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) was added at 0.5 mM to induce Cas9 expression. After ∼16 h, the cells were collected by centrifugation at 8,000 × g and resuspended in lysis buffer [50 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 8.0, 1 M NaCl, 20% (vol/vol) glycerol, and 5 mM Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP; Soltec Ventures)]. The cells were lysed by sonication (3-s pulse-on, 3-s pulse-off for 10 min total at 6-W output), and the soluble lysate was obtained by centrifugation at 20,000 × g for 30 min.

The cell lysate was incubated with 2 mL His-Pur nickel-nitriloacetic acid (nickel-NTA) resin (Thermo Scientific) at 4 °C for 30 min to capture His-tagged Cas9. The resin was transferred to a 20-mL gravity column (Bio-Rad) and washed with 20 column volumes of lysis buffer. Cas9 was eluted in 50 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 8), 0.1 M NaCl, 20% glycerol, 10 mM TCEP, and 300 mM imidazole and concentrated by an Amicon ultracentrifugal filter (Millipore; 100-kDa molecular weight cutoff) to ∼50 mg/mL before being diluted fivefold in low salt buffer containing 50 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 8), 20% glycerol, and 10 mM TCEP. The eluent was injected into a HiTrap SP HP column (GE Healthcare) in purification buffer containing 50 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 8), 0.1 M NaCl, 20% glycerol, and 10 mM TCEP. Cas9 was eluted with purification buffer containing a linear NaCl gradient from 0 to 1 M over five column volumes. The eluted fractions containing Cas9 were concentrated to 200 µM as quantified by bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay (Pierce Biotechnology), snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored in aliquots at –80 °C. All supernegative GFP variants were purified by this same method but using an anion exchange using a Hi-Trap Q HP anion exchange column (GE Healthcare).

Intracellular Delivery of (–27)GFP-Cre/Lipid Nanoparticles.

For the cellular uptake study of lipid/(–27)GFP-Cre nanoparticles, HeLa-DsRed cells were seeded in 24-well plate a day before experiment at a density of 60 K per cell. At the day of experiment, 25 nM (–27)GFP-Cre was mixed without or with 2 μg/mL lipid (all concentrations refer to the final protein and lipid concentration added to cells) in phosphate buffer (25 mM, pH = 7.2), followed by 15 min. of incubation at room temperature. The lipid/protein complexes were then added to cells, and incubated for 6 h at 37 °C before flow cytometry analysis. To evaluate and compare the delivery of (–27)GFP-Cre mediated gene recombination using different lipids, DsRed expression profile was analyzed 24h post delivery.

To study the endocytosis pathway of (–27)GFP-Cre/8-O14B nanoparticles, HeLa-DsRed cells were pretreated with sucrose (450 mM), M-β-CD (2 mM), dynasore (80 µM), or nystatin (100 nM) for 1 h before being exposed to 25 nM (–27)GFP-Cre nanoparticles. The cells were incubated for another 6 h before flow cytometry analysis.

CLSM Study of (–27)GFP-Cre/8-O14B Nanoparticles.

For CLSM imaging of the cellular uptake and intracellular trafficking of (–27)GFP-Cre/8-O14B nanoparticles, HeLa-DsRed cells were seeded in a glass bottom culture dish (MatTeck) at a density of 20,000 cells per well 24 h before the experiment. On the day of the experiment, 12.5 nM (–27)GFP-Cre was mixed without or with 1 μg/mL lipid /8-O14B and incubated with cells for 6 h. At the end of incubation, the medium containing (–27)GFP-Cre/8-O14B nanoparticles was removed, and cells were washed twice using PBS. The endosome/lysosomes were stained with LysoTrackerRed (Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The CLSM images were captured on Leica TCS-SP2 laser scanning confocal microscope (Leica Microsystems).

Cytotoxicity Assay of (–27)GFP-Cre/8-O14B Nanoparticles.

HeLa-DsRed cells were seeded in a 96-well plate a day before the experiment. Cells were treated with (–27)GFP-Cre/8-O14B nanoparticles containing 2 μg/mL lipid, and increased concentrations of (–27)GFP-Cre, from 0 to 50 nM, was added to cells and incubated for additional 24 h. The cell viability was analyzed using the MTT [3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium] assay.

Effect of Lipid Tail Length on Protein Delivery.

Lipid nanoparticles 8-O12B, 8-O16B, or 8-O18B were formulated in the same manner as 8-O14B. The efficiency of these lipids for encapsulation of (–27)GFP-Cre was determined by mixing 300 pmol protein and lipid nanoparticles in 150 µL phosphate buffer (25 mM, pH 7.2) under the optimized delivery condition, followed by a 15-min incubation at room temperature. The nanoparticles were then centrifuged at 1,7000 × g for 20 min at 4 °C, and the protein concentration in the supernatant was measured and normalized to protein concentration in the absence of lipid nanoparticles. The cellular uptake and subsequent Cre-mediated DNA recombination by (–27)GFP-Cre nanoparticles were evaluated by treating HeLa-DsRed cells with lipids for 6 and 24 h to quantify GFP-positive and DsRed-positive cells, respectively.

Protein Charge Density-Determined Delivery Efficiency.

The encapsulation efficiency of Cre fused with (–7)GFP, (–20)GFP, (–27)GFP, or (–30)GFP into 8-O14B nanoparticles was determined similarly as described above. The delivery of these proteins into HeLa-DsRed cells was evaluated by treating cells with 25 nM lipid/protein nanoparticles for 6 h to quantify the cellular uptake of protein or 24 h to analyze the DsRed protein expression profile. In addition, Cre recombinase without negatively supercharged GFP fusion was mixed with 8-O14B and added to cells as a negative control.

Cas9:sgRNA Complex Delivery to KO GFP Gene.

GFP-HEK cells were seeded in a 48-well plate on the day before the experiment at a density of 25,000 cells per well. On the day of transfection, 25 nM S. pyogenes Cas9 with a C-terminal NLS, Cas9-NLS, was incubated with 25 nM sgRNA targeting the EGFP locus for 5 min before being mixed with lipid nanoparticles in phosphate buffer (25 mM, pH = 7.2). The cells were incubated with the lipid/Cas9:sgRNA complex for 4 h, at which time the medium was changed. After this media change, cells were incubated for 72 h before genome editing efficiency was analyzed.

Microinjection of Protein to Mouse Brain.

Rosa26tdTomato mice were housed in a temperature- and humidity-controlled facility with a 12-h light/dark cycle. To deliver (–27)GFP-Cre into mouse brain, (–27)GFP-Cre and 8-O14B were mixed under the optimized in vitro condition and incubated for 5 min at room temperature before each injection. Under anesthesia, mice were microinjected with 5 pmol (0.1 µL) (–27)GFP-Cre or 0.2 µL (–27)GFP-Cre/8-O14B nanoparticles containing 5 pmol protein into the target brain regions. The coordinates for brain nucleus are as follows: dorsomedial hypothalamic nucleus (DM; X = +0.20, Y = −1.6, Z = −5.0); dentate gyrus (DG; X = +0.25, Y = −1.5, Z = −2.2); mediodorsal thalamic nucleus (MD; X = +0.25, Y = −1.4, Z = −2.2); cortex (X = +0.25, Y = −1.4, Z = −1.0); bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST; X = +0.9, Y = +0.4, Z = −4.0); ventral lateral septal nucleus (LSV; X = +0.8, Y = +0.4, Z = −3.5); paraventricular nucleus of hypothalamus (PVN; X = +0.2, Y = −1.4, Z = −5.0); lateral hypothalamus (LH; X = +0.8, Y = −1.6, Z = −5.2). Brain tissues from all groups of mice were collected 6 d after the injections. The brains were cut to 25 µm in depth, and the slices were collected in order. Every other slice around the injection sites was selected for cell counting. tdTomato-positive cells were counted by 0.5 mm2 at the injection sites of each brain slice. The totals from five slices were averaged.

Conclusions

We report the synthesis and utilization of a bioreducible lipid nanoparticle with negatively supercharged proteins or anionic Cas9:sgRNA complexes for genome editing in mammalian cells and in the rodent brain. The integration of a bioreducible disulfide bond into lipids facilitates endosomal escape of nanoparticles containing protein cargo, enabling delivery into the nucleus for protein-based genome editing. In addition, the genetic engineering of supernegative GFP variants or the spontaneous interaction between Cas9 and highly anionic sgRNA mediates the electrostatic self-assembly of the protein with cationic lipids, further improving the nanoparticle-based protein delivery. Moreover, given that the in vivo application and therapeutic relevance of commercial Lipofectamine are restricted by its toxicity and inflammatory side effects (26, 27), our combinatorial strategy to develop synthetic lipids has the potential to discover lipids that overcome these barriers. We (11) and others (28) have previously shown that lipids designed in a combinatorial fashion have low immunogenicity and toxicity.

The efficient and localized delivery of genome-editing proteins to the mouse brain demonstrated here may eventually lead to a protein-based approach for correcting genetic diseases and neurological disorders. For example, the single injection of nanoparticles containing a Cas9:sgRNA complex into brain regions rich in dopaminergic neurons could enhance dopamine signaling and potentially alleviate some symptoms of Parkinson’s disease. One current treatment for Parkinson’s disease is deep brain stimulation. Genome editing offers several potential advantages including being less invasive and avoiding the risk of electrode-induced inflammation, because genome editing can affect a permanent genomic change following a single injection. We showed here how injection into the brain effects highly spatially localized delivery of our nanoparticles, potentially enabling control over the subpopulation of cells to which our agent is delivered and minimizing the risk of unintended effects in other cells. We predict that one of the major challenges for this approach will be to deliver the genome editing protein to enough cells to effect a significant change in phenotype. More experiments must be done to characterize and optimize the pharmacokinetics, efficacy, and safety of this strategy in animal models.

Materials and Methods

Details describing synthesis, formulation, and characterization of lipid nanoparticles; protein expression procedure; protein delivery in vitro and in vivo; and cellular uptake mechanism studies can be found in SI Materials and Methods. All animal care and experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees (#AN-6598) at Baylor College of Medicine.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Science Foundation Grant DMR 1452122 (to Q.X.), National Institutes of Health Grant R01 GM095501 (to D.R.L.), a Broad Institute BN10 Award (to D.R.L.), the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (D.R.L.), American Cancer Society Research Scholar Grant RSG-09-174-01-CCE (to I.G.), and an Onassis Foundation scholarship (to D.P.). Q.X. and Q.W. also acknowledge the Pew Scholar for Biomedical Sciences program from Pew Charitable Trusts. This work was in part supported by American Diabetes Association Junior Faculty Award 7-13-JF-61 (to Q.W.), Baylor Collaborative Faculty Research Investment Program grants (to Q.W.), US Department of Agriculture/Agricultural Research Service Current Research Information System (ARS CRIS) grants (to Q.W.), and new faculty start-up grants from Baylor College of Medicine (to Q.W.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1520244113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Leader B, Baca QJ, Golan DE. Protein therapeutics: A summary and pharmacological classification. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7(1):21–39. doi: 10.1038/nrd2399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Doudna JA, Charpentier E. Genome editing. The new frontier of genome engineering with CRISPR-Cas9. Science. 2014;346(6213):1258096. doi: 10.1126/science.1258096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hsu PD, Lander ES, Zhang F. Development and applications of CRISPR-Cas9 for genome engineering. Cell. 2014;157(6):1262–1278. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zuris JA, et al. Cationic lipid-mediated delivery of proteins enables efficient protein-based genome editing in vitro and in vivo. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33(1):73–80. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davis KM, Pattanayak V, Thompson DB, Zuris JA, Liu DR. Small molecule-triggered Cas9 protein with improved genome-editing specificity. Nat Chem Biol. 2015;11(5):316–318. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fu A, Tang R, Hardie J, Farkas ME, Rotello VM. Promises and pitfalls of intracellular delivery of proteins. Bioconjug Chem. 2014;25(9):1602–1608. doi: 10.1021/bc500320j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gu Z, Biswas A, Zhao M, Tang Y. Tailoring nanocarriers for intracellular protein delivery. Chem Soc Rev. 2011;40(7):3638–3655. doi: 10.1039/c0cs00227e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lu Y, Sun W, Gu Z. Stimuli-responsive nanomaterials for therapeutic protein delivery. J Control Release. 2014;194(0):1–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2014.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Altınoglu S, Wang M, Xu Q. Combinatorial library strategies for synthesis of cationic lipid-like nanoparticles and their potential medical applications. Nanomedicine (Lond) 2015;10(4):643–657. doi: 10.2217/nnm.14.192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang M, Sun S, Neufeld CI, Perez-Ramirez B, Xu Q. Reactive oxygen species-responsive protein modification and its intracellular delivery for targeted cancer therapy. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2014;53(49):13444–13448. doi: 10.1002/anie.201407234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang M, Alberti K, Sun S, Arellano CL, Xu Q. Combinatorially designed lipid-like nanoparticles for intracellular delivery of cytotoxic protein for cancer therapy. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2014;53(11):2893–2898. doi: 10.1002/anie.201311245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang M, Sun S, Alberti KA, Xu Q. A combinatorial library of unsaturated lipidoids for efficient intracellular gene delivery. ACS Synth Biol. 2012;1(9):403–407. doi: 10.1021/sb300023h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sun S, et al. Combinatorial library of lipidoids for in vitro DNA delivery. Bioconjug Chem. 2012;23(1):135–140. doi: 10.1021/bc200572w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang M, et al. Enhanced intracellular siRNA delivery using bioreducible lipid-like nanoparticles. Adv Healthc Mater. 2014;3(9):1398–1403. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201400039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cronican JJ, et al. Potent delivery of functional proteins into Mammalian cells in vitro and in vivo using a supercharged protein. ACS Chem Biol. 2010;5(8):747–752. doi: 10.1021/cb1001153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McNaughton BR, Cronican JJ, Thompson DB, Liu DR. Mammalian cell penetration, siRNA transfection, and DNA transfection by supercharged proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(15):6111–6116. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807883106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lawrence MS, Phillips KJ, Liu DR. Supercharging proteins can impart unusual resilience. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129(33):10110–10112. doi: 10.1021/ja071641y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Le Y, Gagneten S, Tombaccini D, Bethke B, Sauer B. Nuclear targeting determinants of the phage P1 cre DNA recombinase. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27(24):4703–4709. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.24.4703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cong L, et al. Multiplex genome engineering using CRISPR/Cas systems. Science. 2013;339(6121):819–823. doi: 10.1126/science.1231143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cox DBT, Platt RJ, Zhang F. Therapeutic genome editing: Prospects and challenges. Nat Med. 2015;21(2):121–131. doi: 10.1038/nm.3793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gersbach CA. Genome engineering: The next genomic revolution. Nat Methods. 2014;11(10):1009–1011. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.D’Astolfo DS, et al. Efficient intracellular delivery of native proteins. Cell. 2015;161(3):674–690. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim S, Kim D, Cho SW, Kim J, Kim J-S. Highly efficient RNA-guided genome editing in human cells via delivery of purified Cas9 ribonucleoproteins. Genome Res. 2014;24(6):1012–1019. doi: 10.1101/gr.171322.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ramakrishna S, et al. Gene disruption by cell-penetrating peptide-mediated delivery of Cas9 protein and guide RNA. Genome Res. 2014;24(6):1020–1027. doi: 10.1101/gr.171264.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liang X, et al. Rapid and highly efficient mammalian cell engineering via Cas9 protein transfection. J Biotechnol. 2015;208(0):44–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2015.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Armeanu S, et al. Optimization of nonviral gene transfer of vascular smooth muscle cells in vitro and in vivo. Mol Ther. 2000;1(4):366–375. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2000.0053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dokka S, Toledo D, Shi X, Castranova V, Rojanasakul Y. Oxygen radical-mediated pulmonary toxicity induced by some cationic liposomes. Pharm Res. 2000;17(5):521–525. doi: 10.1023/a:1007504613351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Akinc A, et al. A combinatorial library of lipid-like materials for delivery of RNAi therapeutics. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26(5):561–569. doi: 10.1038/nbt1402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]