Significance

Global-scale observations suggest large unexplained emissions of the ozone-depleting chemical carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) despite stringent limits on its production for dispersive uses for many years. Identifying the sources of continued CCl4 emission is necessary before steps can be taken to accelerate the emission decline and limit future ozone depletion. Results from an extensive air sampling network over the United States indicate continued emission of CCl4 with a similar distribution but much larger magnitude than industrial facilities reporting emissions to the US Environmental Protection Agency. If these emissions are attributable to chlorine production and processing and are indicative of release rates of CCl4 from these industries worldwide, a large fraction of ongoing global emissions of CCl4 can be explained.

Keywords: carbon tetrachloride, emissions, United States, ozone-depleting substances, greenhouse gases

Abstract

National-scale emissions of carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) are derived based on inverse modeling of atmospheric observations at multiple sites across the United States from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s flask air sampling network. We estimate an annual average US emission of 4.0 (2.0–6.5) Gg CCl4 y−1 during 2008–2012, which is almost two orders of magnitude larger than reported to the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Toxics Release Inventory (TRI) (mean of 0.06 Gg y−1) but only 8% (3–22%) of global CCl4 emissions during these years. Emissive regions identified by the observations and consistently shown in all inversion results include the Gulf Coast states, the San Francisco Bay Area in California, and the Denver area in Colorado. Both the observation-derived emissions and the US EPA TRI identified Texas and Louisiana as the largest contributors, accounting for one- to two-thirds of the US national total CCl4 emission during 2008–2012. These results are qualitatively consistent with multiple aircraft and ship surveys conducted in earlier years, which suggested significant enhancements in atmospheric mole fractions measured near Houston and surrounding areas. Furthermore, the emission distribution derived for CCl4 throughout the United States is more consistent with the distribution of industrial activities included in the TRI than with the distribution of other potential CCl4 sources such as uncapped landfills or activities related to population density (e.g., use of chlorine-containing bleach).

Carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) is an ozone-depleting substance (ODS) and a potent greenhouse gas (1, 2). Exposure to high concentrations of CCl4 also may have adverse health effects (3–5). As a result of the Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer (Montreal Protocol), a 100% phaseout of CCl4 production for dispersive applications has been in place since 1996 in developed countries and since 2010 in developing countries. Production of CCl4 for nondispersive applications, exempted from the Montreal Protocol, continues at a significant rate and totaled ∼200 Gg in 2012 (6). These nondispersive applications include use as a process agent, use as a feedstock for production of various chemicals (hydrofluorocarbons, hydrofluoroolefins, vinyl chloride monomer, and chlorofluorocarbons) (7), and essential uses defined by the Montreal Protocol.

A mystery persisting for more than a decade stems from the unexpectedly slow rate of atmospheric decline observed for CCl4 given near-zero production magnitudes reported to the United Nation’s Environment Programme’s Ozone Secretariat for dispersive uses and an atmospheric lifetime of 26 (23–37) y (6, 8, 9). The global total emissions of CCl4 derived from observed mole fractions in the remote atmosphere have been 30–80 Gg⋅y−1 since 2008 (6, 9, 10), in contrast to emissions derived from reported production of near zero (<10 Gg⋅y−1) over the same period (6, 9). Global emissions of 30–80 Gg⋅y−1 of CCl4 are substantial compared with those of other ODSs; they accounted for 11–17% of the Ozone Depletion Potential—weighted emissions of all ODSs from 2008 to 2012 (6).

Within the United States, national emissions of CCl4 are thought to be negligible. The national total emissions of CCl4 have been reported as less than 0.5 Gg⋅y−1 in the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Toxic Release Inventory (TRI) and Greenhouse Gas Inventory since 1996 according to industrial reporting (11), reported emission sources, and estimated emission factors (12). For comparison, most atmosphere-based studies have suggested near-zero US emissions in recent years but with uncertainties of up to 14 Gg CCl4⋅y−1 (13–15). Xiao et al. (16) derived North American total emissions of 4.9 ± 1.4 Gg⋅y−1 during 1996–2004 from measurements at remote sites across the globe, including three sites in western North America. Unfortunately, most atmosphere-based estimates have been derived from measurements conducted over limited periods or from only certain regions in the United States, so they are not representative of total US emissions nor can they be appropriately compared with the annualized US national inventory.

Here, we analyze atmospheric measurements of CCl4 in flask air collected from nine tall towers and 16 aircraft profiling sites across North America [part of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA’s) Global Greenhouse Gas Reference Network] from 2008 through 2012 (Fig. 1) (17–19) (SI Text). This allows us to characterize atmospheric mole fractions of CCl4 and their vertical and horizontal variability both in the remote atmosphere upwind of the contiguous United States and in regions with stronger anthropogenic influence within the United States. Given the density and distribution of this flask air sampling network (Fig. 1), the near-surface observations [those collected between 0 km and 1 km above ground level (agl)] are sensitive to emissions from almost all regions within the contiguous United States and, therefore, to many different potential sources of CCl4 (Fig. 1). Furthermore, when combined with an inverse modeling analysis, these observations allow us to characterize spatial and temporal variability of US CCl4 emissions and suggest likely sources that contribute to these ongoing emissions.

Fig. 1.

Map showing the locations of flask air sampling sites where CCl4 was measured as part of this study (aircraft, triangles; tall towers, stars), the resulting sensitivity of this sampling network to CCl4 emissions throughout the United States during 2008–2012 (color shading from yellow to red), and the distribution of emissions reported by different facilities to the US EPA TRI (circles with size indicating emission magnitude). Sites excluded from the inversions and displayed surface sensitivity are indicated as unfilled triangles and stars. Two aircraft sampling sites are not apparent in this map: PFA (65.07°N, 147.29°W) and RTA (21.25°S, 159.83°W).

Observational Evidence for Surface Emissions of CCl4 Within the United States

A near-zero vertical gradient (between 0 km agl and 6 km agl) was observed for CCl4 mole fractions in the remote atmosphere [at the sites THD, ESP, ETL, and during the High-Performance Instrumented Airborne Platform for Environmental Research (HIAPER) Pole-to-Pole Observations (HIPPO) campaign (20)] upwind of the contiguous United States (between 20°N and 55°N), implying a net flux of CCl4 close to zero in the Pacific Ocean basin (Fig. 2, Fig. S1, and ref. 20). Over the contiguous United States, however, particularly near industrial and some populated regions, CCl4 mole fractions were enhanced by up to 60 parts per trillion (ppt) in the planetary boundary layer (PBL) (0–1 km agl) relative to background mole fractions measured in upwind areas and in the free troposphere (3–6 km agl) during 2008–2012 (Fig. 2). Enhanced mole fractions measured in the PBL within the contiguous United States (indicated in Fig. 2) averaged 0.32 ppt at all sites during this period (median: 0.21 ppt; 16th and 84th percentiles: −0.42 ppt and 1.01 ppt); large enhancements (greater than 5 ppt) were observed infrequently (4% of the time). The enhanced mole fractions of CCl4 in the PBL within the contiguous United States (compared with near-zero vertical gradients in the upwind remote atmosphere) imply the presence of ongoing surface emissions of CCl4 from the United States. Furthermore, these observed mole fraction enhancements, as well as the observed vertical gradients, have distinct spatial patterns that imply elevated CCl4 emission rates from specific regions of the United States, including Texas, central California, South Carolina, and Colorado (Fig. 2 and Fig. S2).

Fig. 2.

Measured atmospheric mole fractions of CCl4 in different regions (A and B) and site-specific mole fraction enhancements above remote atmosphere or “background” values (measured at 3–6 km agl) (C), and over time in observations and in forward calculations using different emissions (D). Measured mole fractions in the free troposphere (3–6 km agl) (gray points) are very similar to those measured in the lower atmosphere (0–1 km agl) (black points) at remote sites upwind of the contiguous United States (THD, ESP, and ETL) (A); in the midcontinent, samples with CCl4 mole fractions above background values are observed (B) (the few results above 110 ppt observed at midcontinent sites are not visible). The distribution of enhanced mole fractions measured near the surface (0–500 m agl) has significant spatial variability (C) likely indicative of spatial variations in emission strength (error bars represent the standard error of mean mole fraction enhancements, and site code + “a” indicates aircraft sites). (D) Observed (obs, black unfilled squares connected with a black line) and simulated (sim) monthly median mole fraction enhancements in the lower atmosphere (0–500 m agl) using emissions reported in the US EPA TRI (blue line) and posterior emissions derived here (red line with gray shading representing uncertainty of simulations).

Fig. S1.

A comparison of background and free tropospheric CCl4 mole fractions from different regions and sampling programs. CCl4 mole fractions in the free troposphere (3–6 km agl) at midcontinental nonremote sites as in Fig. 2 (gray) and remote sites upwind of the contiguous United States (THD, ESP, and ETL; blue), as well as those from the HIPPO campaign measured on the same GCMS instrument (red). CCl4 mole fractions in the lower atmosphere (0–3 km agl) in the remote atmosphere are also shown as cyan (THD, ESP, and ETL) and yellow (HIPPO) symbols.

Fig. S2.

Observed average vertical gradients of CCl4 at aircraft sites during 2008–2012. Error bars represent standard errors of average enhancements at different altitudes.

Some loss processes could also cause a vertical mole fraction gradient that mimics or offsets the influence of emissions. For example, CCl4 is removed from the atmosphere primarily by photolysis in the stratosphere, and smaller losses are associated with irreversible degradation in the ocean and by soils. The partial atmospheric lifetimes of CCl4 owing to these processes are estimated to be 44 (36–58) y for photolysis (21), 94 (82–191) y for oceanic loss (22), and 245 y for loss to soils (23). The near-zero vertical gradient in observations made in the remote atmosphere upwind of the contiguous United States implies that the net influence of all loss processes (and far upwind emissions, e.g., from Asia) on the vertical gradient of CCl4 in background air reaching the United States (<6 km asl between 20°N and 55°N) is likely minimal (Fig. 2 and Fig. S1).

Modeling CCl4 Emissions from Atmospheric Observations

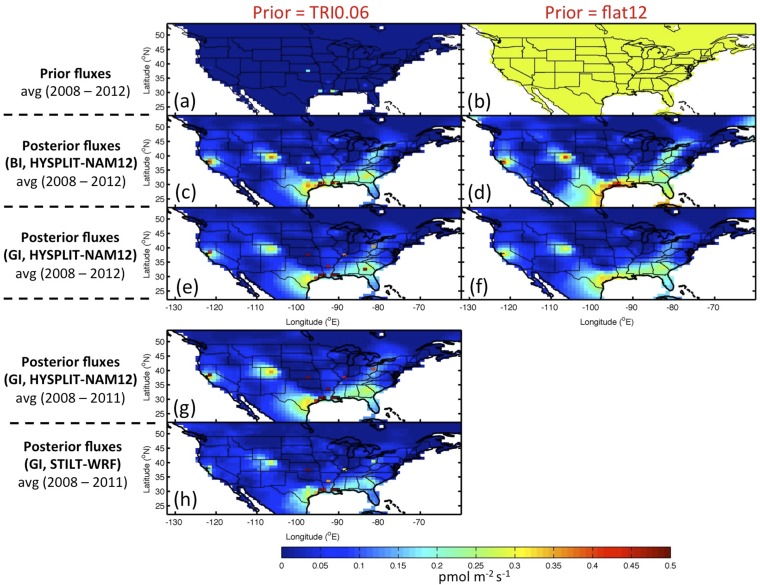

To derive spatiotemporally resolved emissions of CCl4 from observed atmospheric mole fractions, we use both Bayesian and geostatistical inverse analyses (SI Text) (e.g., refs. 19 and 24–31). These inverse approaches find an optimal solution of emissions distribution and magnitude necessary to explain observed enhancements in atmospheric mole fractions (relative to those in the background atmosphere; see SI Text) given the model-computed sensitivity of observations to upstream emissions (or “footprints”; see below) and assumed a priori (“prior” or first guess) emission distributions and magnitudes. A Bayesian Inversion uses a prior emission field (with prescribed distribution and magnitude), whereas a geostatistical inversion optimizes scaling factors of multiple prior spatial activity data (spatial information related to potential emissive sources) and uses the optimally weighted linear combination of these spatial datasets as a deterministic component in the inverse calculation. The geostatistical inversion framework also provides an optimization on stochastic emission residuals that are not prescribed in the deterministic component (SI Text) (31). Here, we use two prior emission distributions and magnitudes including the CCl4 emissions from the US EPA TRI (TRI0.06) (Fig. 1 and Fig. S3), and a prior having temporally and spatially constant emissions (flat12) (Fig. S3). TRI0.06 has an average national total emission of 0.06 Gg⋅y−1 during 2008–2012, whereas flat12 has a constant national total emission of 12 Gg⋅y−1 over this period. The flat12 prior allows the spatial distribution of the corresponding a posteriori (“posterior” or final optimized) emissions to be determined primarily by the atmospheric observations and, when considered with the much smaller TRI0.06 prior, allows the sensitivity of derived posterior fluxes to assumed prior emission magnitudes to be tested.

Fig. S3.

The distribution and magnitude of emissions used as priors and derived as posteriors from multiple approaches and input data to the inverse calculation. Prior emissions were from the US EPA TRI, which yielded an average national total emission of 0.06 Gg⋅y−1 during 2008–2012 (TRI0.06 in A), and a spatially flat prior with a constant national total emission of 12 Gg⋅y−1 (flat12 in B). Posterior emissions of CCl4 averaged over 2008–2012 were derived with a Bayesian inverse analysis (BI) and air transport simulated by HYSPLIT-NAM12 and the different priors (TRI0.06 in C and flat12 in D); they were also derived with the same representation of transport and a Geostatistical inverse analysis (GI) and the different priors (TRI0.06 in E and flat12 in F). Finally, the influence of a different approach to simulating transport (STILT-WRF) is apparent in the comparison of derived emissions averaged over a subset of years (2008–2011), the TRI0.06 prior, and a GI approach using HYSPLIT-NAM (G) or STILT-WRF (H).

Sensitivities of observed mole fractions to upstream surface fluxes associated with each sampling event, also called a sample footprint [as ppt (pmol m−2⋅s−1)−1], were computed using two air transport models: the Hybrid Single-Particle Lagrangian Integrated Trajectory (HYSPLIT) model (ready.arl.noaa.gov/HYSPLIT_disp.php) (32, 33) driven with archived meteorological data from the 12-km-resolution North American Mesoscale Forecast System model (NAM12, domain: ∼60–140°W, 20–60°N), and the Stochastic Time-Inverted Lagrangian Transport (STILT) model with the Weather Research and Forecasting (WRF) meteorology (34). The WRF meteorology has nested domains with resolution of 10 km over the contiguous United States (∼25–55°N; 135–65°W) and 40 km over the rest of North America (∼10–80°N; 170–50°W). STILT-WRF has parameterized convection in the outer domain. HYSPLIT-NAM12 footprints were calculated for each sample collected throughout the entire study period (2008–2012), whereas STILT-WRF footprints were only calculated for samples collected during January 2008 to September 2012.

US National and Regional Emissions of CCl4

The average US CCl4 emission rate derived during 2008–2012 from inverse modeling of these atmospheric observations ranged from 3.3 (± 0.2, 1σ) Gg⋅y−1 to 3.7 (± 0.2, 1σ) Gg⋅y−1 (Fig. 3). The 1σ uncertainty quoted here represents the posterior uncertainty derived from each inversion. The range (3.3–3.7 Gg⋅y−1) reflects emission magnitudes computed from an ensemble of inversions with different prior national emission totals (0.06–12 Gg⋅y−1), different inverse modeling techniques (Bayesian and geostatistical inversions; see SI Text), and a single estimate of background mole fractions (SI Text) and air transport (HYSPLIT-NAM12) (Fig. 3 and Fig. S3). A number of other sources of uncertainty exist when deriving emissions with inverse techniques that are not readily incorporated into the uncertainty stated above. For example, the derived national total emission was 20–30% lower when an alternative representation of air transport (STILT-WRF) was considered during 2008–2011 (Fig. 3 and Fig. S3). Uncertainty in background atmospheric mole fractions, determined from 1,000 Monte Carlo random samplings of the free tropospheric data, adds an uncertainty of ± 0.3 Gg⋅y−1 (∼10%) to the derived 5-y mean US national total emission (Fig. 3 and Fig. S4). Additional uncertainty in the derived national total emissions arises from changes in the air sampling network over time, such as gaps in the measurement record, initiation and termination of air sampling sites, and changes in sampling frequency during the study period. For example, although sampling at the tower sampling sites AMT, SCT, and MWO was initiated in 2009 (AMT and SCT) and 2010 (MWO), sampling at the aircraft sampling sites AAO and BNE was terminated at the end of 2009 and mid-2011. Moreover, sampling frequencies at tower and aircraft sites were reduced by 50% after mid-2011. To understand the influence of these network changes on derived emission magnitudes, we performed inversions with data only from sites where measurements were made throughout 2008–2012. Eliminating data from five sites (i.e., AMT, SCT, MWO, AAO, and BNE) in the inversion caused a −30% to +10% change in derived annual national total emissions during 2010–2012. Additionally, if sampling frequencies were artificially reduced by 50% at all sites during 2008–2010, derived national total emissions were unchanged, although uncertainty in derived emissions increased. Considering all these uncertainties from prior emissions, air transport simulations, background mole fractions, changes in the sampling frequency and locations, and minor corrections to observations (SI Text), derived mean US national total emissions during 2008–2012 ranged between 1.7 Gg⋅y−1 and 6.1 Gg⋅y−1, with a best estimate of 3.6 Gg⋅y−1. This estimate neglects the amount of CCl4 that is irreversibly lost to soils within the contiguous United States. If we consider the soil uptake of CCl4 within the contiguous United States (estimated at 0.3–0.4 Gg⋅y−1; see SI Text), the gross emission of CCl4 from the contiguous United States would be adjusted to 4.0 (2.0–6.5) Gg⋅y−1.

Fig. 3.

The magnitude and distribution of annual CCl4 emissions derived for the contiguous United States in this study from a flat prior (flat12) (A) and reported to the US EPA TRI (B) averaged over 2008–2012 (displayed as annual emissions per grid cell). (C) National total emissions of CCl4 derived here for each year during 2008–2012 from geostatistical inversions (GI) (red lines with error bars) and Bayesian inversions (BI) (blue lines with error bars) with air transport simulated by HYSPLIT-NAM12 and two different priors: TRI0.06 and flat12 (dashed lines). A range of annual national total emissions (yellow lines) were derived with the GI based on uncertainty of background mole fractions of CCl4. Uncertainty of derived national total emissions associated with 1σ uncertainty of atmospheric background mole fractions is shown as gray shading. It was then augmented (pink shading) to account for changes in air sampling network over time. Annual national total emissions of CCl4 derived based on an alternative transport, STILT-WRF, are shown as a cyan line. (D) The 5-y averaged national and state total emissions of CCl4 from the TRI (red; note expanded scale) and derived here (cyan). The six states shown account for the majority of CCl4 emissions derived from the current study.

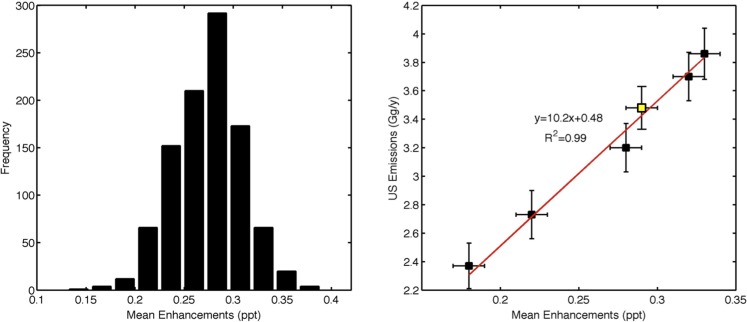

Fig. S4.

(Left) A histogram of mean enhancements for CCl4 mole fractions in samples collected at 0–3 km agl during 2008–2012 calculated with 1,000 different representations of background values. The 1,000 representations of background values at aircraft sites were derived from 1,000 Monte Carlo samplings among free tropospheric data (3–6 km agl) on a flight-by-flight basis. The 1,000 representations of background values at tower sites were derived from 1,000 Monte Carlo samplings among free tropospheric data from aircraft profiles (3–6 km agl) binned by latitudes (every 10 degrees) in a 3-mo interval. (Right) Derived annual mean US total emissions over 2008–2012 regressed against average enhancements derived from five different representations of background (out of the 1,000 Monte Carlo-sampled background time series) using TRI0.06 as a prior. Derived average national total emission based on background mole fractions calculated from 3-mo median free tropospheric mole fractions is shown as the yellow-filled square.

The national average CCl4 emission magnitude for 2008–2012 derived from this extensive air sampling network throughout the United States is 4.0 (2.0–6.5) Gg⋅y−1, or substantially larger than the average reported to the US EPA TRI over this same period (0.06 Gg⋅y−1). The TRI reported emissions can only explain 0.1% of the magnitudes of monthly median enhancements observed in the lower atmosphere (0–500 m agl) for the period of 2008–2012, and simulated enhancements with the derived emissions account for 90–110% of the observed monthly median enhancements (Fig. 2 and SI Text). These results strongly suggest that some combination of underreported emissions and nonreporting sources currently account for the majority of US CCl4 emissions. Although the derived national total emission rate is almost two orders of magnitude larger than reported in the US EPA TRI, the spatial distributions of inventory and atmosphere-derived emissions are similar (Fig. S5). Both estimates (derived here and from the US EPA TRI) suggest the largest emissions of CCl4 come from Texas and Louisiana (Fig. 3), which together account for more than a third (60% in the US EPA TRI) of the national total emissions.

Fig. S5.

US national and regional emissions of CCl4 derived from this study and reported by the US EPA TRI. (Top) Six defined regions within the contiguous United States: Northeast (NE), Southeast (SE), Central North (CN), Central South (CS), Mountain (M), and West (W). (Middle) Annual regional emissions from the assumed priors (TRI0.06 and flat12) (dashed lines) and the derived posteriors in an ensemble of inversions (vertical bars with uncertainties). (Bottom) Relative fractions of regional emissions derived from this study (cyan; normalized by 4.0 Gg⋅y−1 total emission) and reported by the US EPA TRI (red; normalized by 0.06 Gg⋅y−1 total emission).

Spatial distributions and interannual variability of the total emissions derived for the United States are not sensitive to the details of the assumed prior emission distribution and magnitude, air transport models, and inverse approaches (i.e., Bayesian vs. geostatistical inversions) (Fig. 3 and Fig. S3). Results from an ensemble of inversions (including uses of multiple prior fluxes, inverse approaches, and air transport models) consistently show enhanced emissions in states around the Gulf Coast and near the Denver area in Colorado and the San Francisco Bay Area in California (Fig. 3 and Fig. S3). This distribution is consistently suggested by the tower data and aircraft data: An inversion performed with only data from tower sites yields a similar posterior emission distribution for CCl4, and data obtained from aircraft show larger mean vertical gradients in the more emissive regions (Fig. 2 and Fig. S2). Among the ensemble of inversions described above (Fig. 3), derived US national total emissions of CCl4 in 2010 are 2−3 times higher than in all other years (Fig. 3). This increase stems from larger emissions being derived for the central and mountain regions of the United States (Fig. S5). Although it is unclear what caused the increased emission of CCl4 from these regions in 2010, it is not attributable to changes in the sampling locations or sampling frequency (based on inversion results with a static sampling network over time).

Previous independent atmospheric CCl4 observations from aircraft and ship surveys and continuous in situ measurements showed substantially elevated mole fractions of CCl4 near regions identified here as providing significant emissions. They also reported mole fractions close to background levels in the same regions where low emissions are derived in the present work (Fig. 4). For example, in Houston, TX, substantial enhancements of CCl4 (up to 500 ppt) were repeatedly observed in the lower troposphere (0–3 km agl) during multiple aircraft and ship campaigns between 2000 and 2006 [i.e., the Texas Air Quality Study (TexAQS) in 2000 and 2006, and the Gulf of Mexico Atmospheric Composition and Climate Study (GoMACCS) in 2006] (Fig. 4). Near Denver, CO, where considerable ongoing emissions are implied from both surface and aircraft observations and are derived from the inversions (Figs. 2 and 3 and Figs. S2 and S3), elevated mole fractions of CCl4 (averaging 1.5 ppt) have been measured independently by aircraft in 2012 [the Deep Convective Clouds & Chemistry Experiment (DC3) campaign] (35) (Fig. S6) and by in situ instrumentation at the Niwot Ridge site (NWR) (Fig. 4). Significant but infrequent enhancements (up to 50 ppt; approximately five events per year) in atmospheric mole fractions observed at NWR (Fig. 4) clearly imply ongoing emissions (but with unknown sources) of CCl4 within Colorado. In other areas well sampled by aircraft (Fig. 4), such as the northeastern United States and the south-central United States, no substantial enhancements of atmospheric CCl4 mole fractions have been observed recently in other studies (Fig. 4). At a site in the northeastern United States (LEW) (Fig. 1) where we have made measurements since 2013, near-zero enhancements in CCl4 mole fractions are observed, consistent with there being no significant emissions in this region. In the San Francisco Bay Area, however, enhancements observed at the sites STR and WGC suggest emissions of CCl4 from surrounding areas (Figs. 2 and 3 and Fig. S3), whereas implications of data from a summertime aircraft campaign over California in 2010 [i.e., during the California Nexus of Air Quality and Climate Change (CALNEX) experiment] are less clear. We find that the variability in the CALNEX free tropospheric data are large compared with the typical enhancements observed at the STR and WGC sites, making it difficult to quantify small emissions from these CALNEX results.

Fig. 4.

CCl4 mole fractions observed independently from aircraft, ship, and quasi-continuous in situ measurements within the contiguous United States. (A) Locations of continuous in situ atmospheric CCl4 measurements at the site Niwot Ridge (NWR) (green star) and selected aircraft or ship surveys in which atmospheric measurements of CCl4 were made within 0–3 km agl (colored dots). (B) CCl4 mole fractions observed at NWR (black) and from all samples collected during the surveys (colored symbols) shown in A. A small number of samples with mole fractions above 140 ppt are not visible (in 2000, 2006, and 2010). The subset of observations considered to be unaffected by recent emissions (i.e., background) are indicated as light gray points. For the aircraft surveys, they are mole fractions measured in the free troposphere; for the ship survey (GOMACCS) and in situ data (at NWR), they represent the lowest 90th percentile of the detrended data. (C) The spatial distribution of emissions derived in this study from a flat prior (flat12) (black shading as Gg/y/grid cell) and samples showing substantial CCl4 mole fraction enhancements (red) and those with background CCl4 mole fractions (blue) during TexAQS in 2000 and 2006, and GoMACCS in 2006. Industrial facilities reporting emissions during 2008–2012 to the TRI are shown as cyan circles.

Fig. S6.

Atmospheric CCl4 observations from the aircraft campaign, DC3 (35). (Left) Enhanced (red) and background (blue) CCl4 mole fractions observed within the lower atmosphere (0–3 km agl). Gray shading indicates CCl4 emissions derived from this study with a flat prior (flat12). (Right) Average vertical profiles observed over the Front Range area in Colorado during DC3. Uncertainties represent one standard error of average mole fractions observed at different altitudes; note that a calibration update from 18 Oct 2015 is included in these results.

Possible Sources for Ongoing CCl4 Emissions

Currently, atmospheric observations in the remote atmosphere and our understanding of the CCl4 lifetime suggest emissions of 30–80 Gg⋅y−1 globally (6, 9, 10); results presented here imply that the United States only accounts for 8% (3–22%) of these ongoing global CCl4 emissions. A number of processes have been suggested as contributing to the ongoing global CCl4 emissions, including fugitive emissions from feedstock uses and applications as process agents in chloralkali production plants, methane chlorination, petrochemical, rubber, flame retardant, and pesticide industries (7, 11, 36), and emissions from toxic wastes and treatment facilities (11, 37), uncapped landfills (36, 37), and chlorine-bleach-containing household products (when mixed with detergent) (38, 39).

A simple visual inspection of the results (Fig. S7) and a rigorous statistical analysis using the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) (SI Text and Table S1) (31, 40, 41) both suggest that the distribution of derived posterior emissions is more consistent with that of industrial sources reported by the US EPA TRI (particularly chloralkali production plants) than the distribution of uncapped landfills or population (Fig. S7 and Table S1). BIC scores rank different spatial activity data based on the goodness of fit to the observations and the number of spatial datasets included as fitting parameters. The spatial distribution giving the lowest BIC score represents the one that best explains the observations without overfitting them. Here, we consider a few spatial distributions: industrial sources reported by the US EPA TRI (in which CCl4 emissions were dominantly from chlorine production and processing industries), chloralkali production plants, uncapped landfills, population (so as to represent the distribution of CCl4 from, e.g., household bleach use), and their combinations (Fig. S7 and Table S1). Among all spatial datasets considered here, distributions of industrial sources in the US EPA TRI (and chloralkali production plants alone) have the lowest BIC scores (Table S1), as well as the highest correlation with atmospheric observations (when these distributions were converted to mole fraction enhancements using atmospheric transport models) (SI Text and Table S1). This suggests that, among the limited source distributions tested here, industrial sources included in the TRI provide the best representation of the atmospheric observations. The relatively low CCl4 emission rate derived for the densely populated northeastern United States and the poor correlation of the derived emission distribution with population (Table S1) suggests that household bleach use does not account for an appreciable fraction of total US emissions.

Fig. S7.

The distribution of posterior emissions of CCl4 derived in this work (with the flat prior, flat12) compared with the distributions of CCl4 emissions from the US EPA TRI, locations of chloralkali production plants, uncapped landfills, and population.

Table S1.

Statistics showing the relation between observed and simulated CCl4 mole fraction enhancements using different spatial models: the correlation coefficient (r), BIC scores of different spatial models, differences in BIC scores (ΔBIC), and relative likelihood compared to the model with the lowest BIC score

| Spatial models | r* | BIC score | ΔBIC | Relative likelihood |

| TRI (industrial) | 0.17 | 7,759 | 0 | 1 |

| Chloralkali (industrial) | 0.17 | 7,759 | 0 | 1 |

| Uncapped landfills | 0.04 | 7,769 | 10 | 0.006 |

| Population | 0.03 | 7,779 | 20 | 0.00004 |

| TRI + uncapped landfills | 0.16 | 7,765 | 6 | 0.04 |

| TRI + uncapped landfills + population | 0.18 | 7,773 | 14 | 0.0009 |

All correlation coefficients are statistically significant with P < 0.01.

Summary and Global Implications

Atmospheric observations in and around the contiguous United States provide robust evidence for continued emissions of the ODS, CCl4, during 2008–2012. An ensemble of inverse modeling of those observations suggests a gross emission of 4.0 (2.0–6.5) Gg⋅y−1 averaged between 2008 and 2012. The national total emission of CCl4 estimated here is almost two orders of magnitude greater than emissions reported to the US EPA TRI over this same period. Despite this large discrepancy, the distributions of derived and inventory emissions are similar. The regions identified as contributing significantly to ongoing US CCl4 emissions (except for the San Francisco Bay Area) also exhibited enhanced CCl4 mole fractions during independent aircraft campaigns, ship surveys, and quasi-continuous in situ measurements.

Our findings suggest that the majority of US CCl4 emissions could be related to industrial sources associated with chlorine production and processing. Thus, we consider here global implications of these findings, because emissions of CCl4 from this industry are not likely to be restricted to the United States alone. If we assume that the rate of CCl4 release is proportional to chlorine demand or emissions of other gaseous chemicals (e.g., CH4) from chemical industrial processes (as defined by and reported in the Emission Database for Global Atmospheric Research inventory) between the United States and other countries throughout the globe, we derive global emissions of CCl4 in the range of 12–50 (best estimate: 28) Gg⋅y−1. This could explain a large fraction of the current global emission rate (30–80 Gg⋅y−1) (6, 9, 10) derived from remote atmospheric observations and our understanding of global CCl4 losses. Although there are many uncertainties in this extrapolation, an even higher CCl4 emission from chlorine production and processing is plausible given reports suggesting a higher coproduction rate of CCl4 during methane chlorination in some developing countries (42), and the fact that developing countries are not required to capture emissions of CCl4 associated with evaporative losses or as storage tanks are filled (42).

SI Text

Atmospheric Measurements of CCl4

Flask air samples were collected approximately daily at tower sites between 2008 and mid-2011. Flasks were also filled during aircraft vertical profiling (6–12 flasks/profile) and were obtained biweekly over this same period. The location of these sampling sites is apparent in Fig. 1; more information about these sites is available at www.esrl.noaa.gov/gmd/ccgg/aircraft/index.html and www.esrl.noaa.gov/gmd/ccgg/insitu/index.html. Sampling frequency in both the tower and aircraft sampling programs was reduced by 50% from mid-2011 through 2012. Paired flasks were sometimes filled to assess reproducibility of sampling and analysis. Collected flask air was analyzed by gas chromatography and mass spectrometry (GCMS) in our Boulder laboratory. Measured dry air mole fractions (pmol CCl4 per mol dry air, or ppt) were determined by calibration against a high-pressure real air primary reference sample in which the CCl4 mole fraction had been determined by periodic comparisons to a suite of gravimetric standards with known CCl4 mole fractions. The scale accuracy is estimated to be 1–2%, which is a magnitude comparable to differences in global annual mean mole fractions derived by NOAA and other global sampling networks (6). The average precision of measured CCl4 mole fractions determined from paired flask air samples was 0.4 (±0.4) % (1σ, n = 2,701) during 2008–2012. Long-term consistency of our measurement scale is assessed by repeat analyses of gravimetric standards, repeat analyses of the primary reference samples, and repeat analyses of air from a suite of archived tanks (Acculife-treated aluminum cylinders and 30-L electropolished stainless steel canisters) initially filled to high pressure (900−2,000 psi) with humidified real air.

Flux Calculation via Inverse Modeling

We use Bayesian and geostatistical inversions (e.g., refs. 19 and 24–31) to derive gridded monthly emissions based on atmospheric CCl4 observations. Both inversion techniques are based on a linear relation between observed mole fraction enhancements (z) and upstream fluxes (s).

| [S1] |

where H is the sensitivity of observed enhancements to upstream emissions, or footprints [ppt (pmol m−2⋅s−1)−1] or the Jacobian matrix. Epsilon (ε) represents the model−data mismatch error and reflects the sum of errors from observations and atmospheric transport models. H is calculated with two different atmospheric transport models, HYSPLIT-NAM12 and WRF-STILT, by running the models backward in time (19). For each sampling event, 500 particles were released at the sampling location in the model, and their positions were recorded at 15-min intervals backward in time for 10 d or until all particles exited the model domain (HYSPLIT-NAM12: ∼60–140°W, 20–60°N; WRF-STILT: ∼10–80°N; 170–50°W). The magnitude of the time-dependent sensitivity for each observation to emissions in a certain grid cell is determined by the number of particles within the boundary layer in that grid cell at each time step (43).

A Bayesian inversion (BI) (e.g., refs. 19, 24–28, and 30) starts with a prior emission field with prescribed distribution and magnitude (sp). The optimal solution of posterior emissions (s) reflects a balance between emissions suggested by observations and prior emissions, given their corresponding uncertainties. These uncertainties are expressed as model−data mismatch (R) and prior flux error covariance (Q) matrices. The optimal solution is obtained by minimizing the cost function (LBI) defined as

| [S2] |

The structure and magnitudes of R and Q, along with H, determine the relative weight of observations and prior emissions in the optimal solution (posterior flux).

Compared with a BI, the geostatistical inversion (GI) (e.g., refs. 29 and 31) considers a weighted linear combination of multiple spatial activity data as prior information, and it provides an optimal solution for scaling factors associated with each of the selected spatial activity data as well as a stochastic component of fluxes not prescribed by any of the spatial datasets being considered (29, 31). The modified cost function is

| [S3] |

where each column of X includes individual spatial activity data; β is a vector with unknown scaling factors for spatial activity data contained in X. The stochastic component of fluxes is the difference between s and Xβ.

In both Bayesian and geostatistical inversions, we assume no correlated errors between observations associated with measurements or air transport in the inversion setup; thus R is a diagonal matrix. To reduce correlated errors between observations for data included in inversion, we average mole fractions measured in samples collected within 30 min at tower sites and within 500 m at aircraft sites. A measure of the influence of correlated errors in simulated air transport on derived fluxes is reflected in part by the differences in fluxes derived with the different air transport models (HYSPLIT-NAM12 and WRF-STILT). We only include data below 3 km agl in inversions. Data between 3 km agl and 6 km agl were used to determine atmospheric background mole fractions of CCl4 (see below). We also exclude nighttime data to minimize enhanced transport errors at night.

Appropriately representing uncertainties in the model−data mismatch and the prior fluxes (R and Q) is critical in finding an accurate solution to this inverse problem. We used maximum likelihood estimation (44) and a restricted maximum likelihood method (31) to objectively determine seasonally and interannually varying model−data mismatch errors at individual sites (diagonal elements in R), as well as interannually varying prior flux error covariance matrices (Q) (19). In deriving the prior flux error covariance matrix (Q), we considered temporal and spatial correlation in prior flux errors (e.g., refs. 19, 29, and 31). This allows the model to correct the systematic biases in prior fluxes on large spatial and temporal scales.

Uncertainties of posterior emissions (or posterior covariance of flux errors) (V) derived from Bayesian and geostatistical inversions can be estimated by the following equations:

| [S4] |

| [S5] |

where, M and Λ are defined as

| [S6] |

| [S7] |

Note that we conducted five batch inversions to obtain monthly gridded fluxes of CCl4 during 2008–2012 (5). Each batch had a 15 to 18-mo time interval. Between two sequential batches, there was a 6-mo overlap period that minimizes the discontinuity problem in derived fluxes. We used algorithms developed by Yadav and Michalak (45) to avoid building a full matrix of Q and meanwhile improve the computational efficiency for inverting large matrices. Annual national, regional, and state total fluxes and their associated errors were then computed based on derived monthly gridded fluxes, monthly gridded flux errors, and their temporal and spatial correlation.

Determination of Atmospheric Background Levels of CCl4

At aircraft sites, background mole fractions are derived from median free tropospheric mole fractions measured between 3 km agl and 6 km agl on a flight-by-flight basis. At tower sites, background mole fractions were derived from the 3-mo median free tropospheric mole fractions measured at all aircraft sites except SGP (see below) after binning by latitude (centered on 30°N, 40°N, and 50°N). Uncertainty of background mole fractions was estimated using 1,000 random samplings of free tropospheric data (between 3 km agl and 6 km agl) in each 3-mo time interval (Fig. S4). To minimize the influence of stratospheric air mixing down to the troposphere on our estimation of background mole fractions (which would lead to a positive vertical gradient in the troposphere that was unrelated to emission magnitudes), we did not use observations above 6 km agl. Randomly sampling free tropospheric data between 3 km agl and 6 km agl and using them as our background levels allows us to account for the small influence of stratospheric air on estimated background values.

CCl4 mole fractions in the free troposphere at nonremote sites within the midcontinent of the contiguous United States are comparable with those observed at remote sites upwind of the contiguous United States (i.e., THD, ESP, and ETL) (Fig. 1) and over the Pacific Oceanic basin during HIPPO (20) within our modeled latitudes (Fig. S1), suggesting that mole fractions of CCl4 in the free troposphere over the contiguous United States are not measurably altered by venting of the continental boundary layer as air passes from the west to east coast. Additionally, they are in the same range as CCl4 mole fractions observed in the lower atmosphere (0–3 km agl) in remote areas (i.e., at THD, ESP, and ETL and during HIPPO) (Fig. S1), indicating no measurable vertical gradient of CCl4 in the remote atmosphere below 6 km agl and no significant sampling artifacts among these multiple sampling locations and programs.

At SGP, mole fractions in the free troposphere were always offset anomalously low by 1–2% and suggested the presence of sampling artifacts associated with unique sampling equipment in place there; the low bias at SGP was only observed for CCl4 and not for other compounds that are lost by photolysis in the upper atmosphere (e.g., N2O, Halon 1211), further suggesting sampling artifacts and not real atmospheric variability. Therefore, SGP was excluded in the calculation of background levels.

Using free tropospheric aircraft data as a proxy for background values at towers requires both aircraft and tower data to be on the same scale. However, we observed an average of 0.3 ppt discrepancy in tower and aircraft samples collected within the PBL (<1 km agl) at similar time windows (±1 d) at the sites LEF and WBI. Thus, we adjusted CCl4 mole fractions downward by 0.3 ppt for all air samples collected from towers. Although we consider this correction to be appropriate, if we had chosen to apply this adjustment only at the LEF and WBI sites where the difference was explicitly measured, the derived US national total emissions would be 1.2 Gg⋅y−1 higher (3.2–6.5 Gg⋅y−1 as opposed to 2.0–5.3 Gg⋅y−1).

Evaluation of Derived Posterior Fluxes

With derived posterior fluxes, simulated mole fraction enhancements agree much better with observations than those simulated with prior fluxes (Fig. 2). When we use fluxes reported by the US EPA TRI (TRI0.06) or a flat prior (flat12), simulated monthly median mole fractions were about 0.1% or 350% of observed monthly median enhancements in mole fractions. With our derived posterior fluxes, simulated monthly median enhancements (in mole fractions) are within 10% of those determined from observations (Fig. 2). Our derived emissions can explain the majority of the small enhancements (<5 ppt) observed in the lower atmosphere (0–3 km agl) within the contiguous United States (Fig. S8). However, these derived emissions do not provide a good fit to observations with large enhancements (those larger than 5 ppt, which is more than 15 times greater than the average enhancement we observed within the contiguous United States and which accounts for about 4% of the data in the lower atmosphere) (Fig. S8). This is likely due to errors associated with near-field air transport and underestimated prior flux errors in areas near measurement locations.

Fig. S8.

Residuals between simulated (sim) and observed (obs) mole fractions for all data included in the inversion. (Top) Time series of residuals by sample (gray dots), by monthly mean (blue), and by monthly median (red). Residuals below −5 ppt (which account for 4% of the data) are not shown in the graph. (Bottom) Histograms of all residuals. Insert (whose y axis is on a log scale) shows the full range of the residual histogram.

Estimation of Soil Uptake Rate of CCl4 Within the Contiguous United States

We estimate a soil flux within the contiguous United States of 0.3–0.4 Gg⋅y−1 based on loss rates derived from static soil flux chamber studies for seven different biomes (23) (scaled to account for CCl4 mole fraction differences between their study and our atmospheric observations within the contiguous United States) and the area of those biomes over the contiguous United States (23, 46). This calculation assumes first-order kinetics for soil uptake processes.

BIC

We use BIC (40, 47, 48) to evaluate which spatial activity data can best explain the spatial variability of observed enhancements in CCl4 mole fractions, and thus inform us which are the most likely sources of CCl4 among all available spatial activity data. The BIC score (Eq. S7 and Table S1) not only takes account of how well the converted observational signal of the scaled spatial activity data (by multiplying with the footprints) can fit the atmospheric observations but also introduces a penalty for adding parameters to avoid overfitting.

| [S8] |

where p is the number of spatial activity data; n is the number of CCl4 observations; and L is the posterior log-likelihood of the model, which can be approximated by the following expression (31, 44):

| [S9] |

| [S10] |

Each BIC score corresponds to a posterior likelihood. The difference of BIC scores (ΔBIC) approximates the relative likelihood of one model relative to another (RL) (49). The lower the BIC score, the higher the likelihood of the model it represents.

| [S11] |

To help interpret the BIC scores, we have included correlation coefficients of various spatial datasets considered here (converted to enhancements in mole fractions using atmospheric transport models) with observations in Table S1. Note that, because the ongoing emissions of CCl4 from the United States are small, the ratio of enhancements to measurement noise is small compared with compounds that currently have strong emissions. Therefore, it is expected that correlation between observed and simulated enhancements with any distribution will be small (Table S1). Nevertheless, the observed variability of CCl4 that can be explained by the distributions of the TRI or chloralkali production plants (r = 0.17, P < 0.01) accounts for one quarter of that which could be explained by the derived posterior emissions (r = 0.36, P < 0.01) (Table S1).

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Daniel, D. Godwin, S. Yvon-Lewis, A. Jacobson, K. Masarie, L. Bruhwiler, D. Baker, and S. Basu for discussion, R. Draxler and A. Stein for advice on running Hybrid Single-Particle Lagrangian Integrated Trajectory (HYSPLIT) simulations, and J. Butler, M. S. Torn, D. Mondeel, J. Higgs, M. Crotwell, P. Lang, W. Wolter, D. Neff, J. Kofler, I. Simpson, N. Blake, and others involved with program management, sampling, analysis, and logistics. We also thank members of the HIAPER HIPPO team, particularly S. Wofsy, for enabling flask sampling during that mission and Earth Networks for sample collection at the LEW site. This study was supported in part by National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Climate Program Office's AC4 program. Flask sampling at the tower sites WGC and STR was partially supported by a California Energy Commission Public Interest Environmental Research Program Grant to the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory under Contract DE-AC02-05CH11231.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1522284113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Myhre G, et al. Anthropogenic and natural radiative forcing. In: Stocker TF, et al., editors. Climate Change 2013: The physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Chlimate Change. Cambridge Univ Press; Cambridge, UK: 2013. pp. 659–740. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Meteorological Organization . Scientific Assessment of Ozone Depletion: 2014. World Meteorol Org; Geneva: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hua I, Hoffmann MR. Kinetics and mechanism of the sonolytic degradation of CCl4: Intermediates and byproducts. Environ Sci Technol. 1996;30(3):864–871. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pavanato A, et al. Effects of quercetin on liver damage in rats with carbon tetrachloride-induced cirrhosis. Dig Dis Sci. 2003;48(4):824–829. doi: 10.1023/a:1022869716643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rusu MA, Tamas M, Puica C, Roman I, Sabadas M. The hepatoprotective action of ten herbal extracts in CCl4 intoxicated liver. Phytother Res. 2005;19(9):744–749. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carpenter LJ, et al. 2014. Ozone-depleting substances (ODSs) and other gases of interest to the Montreal Protocol. Scientific Assessment of Ozone Depletion: 2014 (World Meteorol Org, Geneva), pp 1−101.

- 7.United Nations Environment Programme/Technology and Economic Assessment Panel . Report on the Technology and Economic Assessment Panel. UN Environ Programme; Nairobi: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Montzka SA, et al. 2011. Ozone-depleting substances (ODSs) and related chemicals. Scientific Assessment of Ozone Depletion 2010 (World Meteorol Org, Geneva), pp 1−108.

- 9.Liang Q, et al. Constraining the carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) budget using its global trend and inter-hemispheric gradient. Geophys Res Lett. 2014;41(14):2014GL060754. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rigby M, et al. Recent and future trends in synthetic greenhouse gas radiative forcing. Geophys Res Lett. 2014;41(7):5307–5315. [Google Scholar]

- 11.US Environmental Protection Agency TRI Explorer 2013 Dataset (released March 2015) 2015 Available at iaspub.epa.gov/triexplorer/tri_release.chemical. Accessed June 2, 2015.

- 12.US Environmental Protection Agency . Inventory of U.S. Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Sinks: 1990−2011. US Environ Prot Agency; Washington, DC: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hurst DF, et al. Continuing global significance of emissions of Montreal Protocol–restricted halocarbons in the United States and Canada. J Geophys Res. 2006;111(D15):D15302. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miller JB, et al. Linking emissions of fossil fuel CO2 and other anthropogenic trace gases using atmospheric 14CO2. J Geophys Res. 2012;117(D8):D08302. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Millet DB, et al. Halocarbon emissions from the United States and Mexico and their global warming potential. Environ Sci Technol. 2009;43(4):1055–1060. doi: 10.1021/es802146j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xiao X, et al. Atmospheric three-dimensional inverse modeling of regional industrial emissions and global oceanic uptake of carbon tetrachloride. Atmos Chem Phys. 2010;10(21):10421–10434. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Andrews AE, et al. CO2, CO, and CH4 measurements from tall towers in the NOAA Earth System Research Laboratory’s Global Greenhouse Gas Reference Network: instrumentation, uncertainty analysis, and recommendations for future high-accuracy greenhouse gas monitoring efforts. Atmos Meas Tech. 2014;7(2):647–687. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sweeney C, et al. Seasonal climatology of CO2 across North America from aircraft measurements in the NOAA/ESRL Global Greenhouse Gas Reference Network. J Geophys Res. 2015;120(10):5155–5190. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hu L, et al. U.S. emissions of HFC-134a derived for 2008–2012 from an extensive flask-air sampling network. J Geophys Res. 2015;120(2):821–825. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wofsy SC. HIAPER Pole-to-Pole Observations (HIPPO): Fine-grained, global-scale measurements of climatically important atmospheric gases and aerosols. Philos Trans A Math Phys Eng Sci. 2011;369(1943):2073–2086. doi: 10.1098/rsta.2010.0313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ko MKW, Newman PA, Reimann S, Strahan SE (Eds) (2013) Lifetimes of Stratospheric Ozone-Depleting Substances, Their Replacements, and Related Species, SPARC Rep 6 (World Clim Res Programme, Geneva)

- 22.Yvon-Lewis SA, Butler JH. Effect of oceanic uptake on atmospheric lifetimes of selected trace gases. J Geophys Res. 2002;107(D20):4414. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Happell J, Mendoza Y, Goodwin K. A reassessment of the soil sink for atmospheric carbon tetrachloride based upon static flux chamber measurements. J Atmos Chem. 2014;71(2):113–123. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rodgers CD. Inverse Methods for Atmospheric Sounding. World Sci; Tokyo: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bruhwiler LMP, Michalak AM, Peters W, Baker DF, Tans P. An improved Kalman Smoother for atmospheric inversions. Atmos Chem Phys. 2005;5(10):2691–2702. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brunner D, et al. An extended Kalman-filter for regional scale inverse emission estimation. Atmos Chem Phys. 2012;12(7):3455–3478. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maione M, et al. Estimates of European emissions of methyl chloroform using a Bayesian inversion method. Atmos Chem Phys. 2014;14(6):9755–9770. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Manning AJ, Ryall DB, Derwent RG, Simmonds PG, O’Doherty S. Estimating European emissions of ozone-depleting and greenhouse gases using observations and a modeling back-attribution technique. J Geophys Res. 2003;108(D14):4405. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Michalak AM, Bruhwiler L, Tans PP. A geostatistical approach to surface flux estimation of atmospheric trace gases. J Geophys Res. 2004;109(D14):D14109. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rigby M, Manning AJ, Prinn RG. Inversion of long-lived trace gas emissions using combined Eulerian and Lagrangian chemical transport models. Atmos Chem Phys. 2011;11(18):9887–9898. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miller SM, et al. Anthropogenic emissions of methane in the United States. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(50):20018–20022. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1314392110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Draxler RR, Hess G. An overview of the HYSPLIT_4 modelling system for trajectories. Aust Meteorol Mag. 1998;47(4):295–308. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stein AF, et al. 2015. NOAA’s HYSPLIT atmospheric transport and dispersion modeling system Bull Am Meteorol Soc 96(12):2059−2077.

- 34.Nehrkorn T, et al. Coupled weather research and forecasting–stochastic time-inverted Lagrangian transport (WRF–STILT) model. Meteorol Atmos Phys. 2010;107(1-2):51–64. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Blake D. 2012. DC3 Data. Available at www-air.larc.nasa.gov/cgi-bin/ArcView/dc3?MERGE=1. Accessed March 18, 2015.

- 36.United Nations Environment Programme/Chemicals Technical Options Committee 2006. 2006 Report of the Chemicals Technical Options Committee (UN Environ Programme, Nairobi)

- 37.Fraser PJ, et al. Australian carbon tetrachloride emissions in a global context. Environ Chem. 2014;11(1):77–88. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Odabasi M, Elbir T, Dumanoglu Y, Sofuoglu SC. Halogenated volatile organic compounds in chlorine-bleach-containing household products and implications for their use. Atmos Environ. 2014;92:376–383. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Odabasi M. Halogenated volatile organic compounds from the use of chlorine-bleach-containing household products. Environ Sci Technol. 2008;42(5):1445–1451. doi: 10.1021/es702355u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Posada D, Buckley TR. Model selection and model averaging in phylogenetics: Advantages of akaike information criterion and bayesian approaches over likelihood ratio tests. Syst Biol. 2004;53(5):793–808. doi: 10.1080/10635150490522304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Burnham KP, Anderson DR. Multimodel Inference: Understanding AIC and BIC in Model Selection. Sociol Methods Res. 2004;33(2):261–304. [Google Scholar]

- 42.United Nations Environment Programme 2009. Report on Emission Reduction and Phase-Out of CTC (Decision 55/45) (UN Environ Programme, Nairobi)

- 43.Lin JC, et al. A near-field tool for simulating the upstream influence of atmospheric observations: The Stochastic Time-Inverted Lagrangian Transport (STILT) model. J Geophys Res. 2003;108(D16):4493. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Michalak AM, et al. Maximum likelihood estimation of covariance parameters for Bayesian atmospheric trace gas surface flux inversions. J Geophys Res. 2005;110(D24):D24107. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yadav V, Michalak AM. Improving computational efficiency in large linear inverse problems: An example from carbon dioxide flux estimation. Geosci Model Dev. 2013;6(3):583–590. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Matthews E. Global vegetation and land use: New high-resolution data bases for climate studies. J Clim Appl Meteorol. 1983;22(3):474–487. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wit E, van den Heuvel E, Romeijn JW. ‘All models are wrong...’: An introduction to model uncertainty. Stat Neerl. 2012;66(3):217–236. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tamura Y, Sato T, Ooe M, Ishiguro M. A procedure for tidal analysis with a Bayesian information criterion. Geophys J Int. 1991;104(3):507–516. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Akaike H. Information measures and model selection. B Int Statist Inst. 1983;50(1):277–291. [Google Scholar]