Abstract

Several species of nonhuman primates respond negatively to inequitable outcomes, a trait shared with humans. Despite previous research, questions regarding the response to inequity remain. In this study, we replicated the methodology from previous studies to address four questions related to inequity. First, we explored the impact of basic social factors. Second, we addressed whether negative responses to inequity require a task, or exist when rewards are given for ‘free’. Third, we addressed whether differences in the experimental procedure or the level of effort required to obtain a reward affected responses. Finally, we explored the interaction between ‘individual’ expectations (based on one's own previous experience) and ‘social’ expectations (based on the partner's experience). These questions were investigated in 16 socially housed adult chimpanzees using eight conditions that varied across the dimensions of reward, effort and procedure. Subjects did respond to inequity, but only in the context of a task. Differences in procedure and level of effort required did not cause individuals to change their behaviour. Males were more sensitive to social than to individual expectation, while females were more sensitive to individual expectation. Finally, subjects also increased refusals when they received a better reward than their partner, which has not been documented previously. These results indicate that chimpanzees are more sensitive to reward inequity than procedures, and that there is interaction between social and individual expectations that depends upon social factors.

Keywords: chimpanzee, expectation, inequity, Pan troglodytes, prosocial behaviour, sex difference

Humans are very sensitive to inequity. Experiments in a variety of disciplines have shown that we respond quite negatively to receiving less than a partner (Walster [Hatfield] et al. 1978; Kahneman et al. 1986; Zizzo & Oswald 2001; Fehr & Rockenbach 2003). Although these responses do vary based on factors such as one's culture (Henrich et al. 2001), the quality of the relationship between the individuals involved (Attridge & Berscheid 1994; Clark & Grote 2003) and one's personality (Colquitt et al. 2006; Wiesenfeld et al. 2007), the presence of this response is remarkably consistent across different groups.

Humans' ability to detect inequity may derive from an evolved characteristic shared more generally among animals, rather than being a hallmark of the human species (Brosnan 2008b). In fact, the presence of a negative response to inequitable outcomes has been documented in two nonhuman primate species, capuchin monkeys, Cebus apella (Brosnan & de Waal 2003; van Wolkenten et al. 2007; Fletcher 2008) and chimpanzees, Pan troglodytes (Brosnan et al. 2005), as well as one nonprimate species, the domestic dog, Canus domesticus (Range et al. 2008). In these studies, subjects had to complete a task, after which they were offered rewards that were less preferred than those their social partners had received. Subjects often refused the rewards or refused to continue participating in the test, which was interpreted as a negative reaction to inequity.

However, as in human studies, primates do not always respond to inequity. Not all studies have found this response (e.g. Bräuer et al. 2009; see below for further discussion), and even within studies, some individuals respond while others do not (e.g. Brosnan et al. 2005). It is difficult to determine why this variation occurs, as studies vary in methodology, and other differences may exist in housing or husbandry practises that affect subjects' reactions. Nevertheless, careful comparisons make it possible to identify the factors that moderate the response. Below we summarize what is known thus far and the goals of the current study.

Basic social factors, such as rank and sex, are not often predictive in measuring responses to inequity. One study investigating the response in all four species of great ape found that dominants were more likely to both ignore food and leave the experimental area than subordinates, although this behaviour did not vary between the conditions of equity and inequity (Bräuer et al. 2006). However, the analysis was not done for the species separately, so it is not clear which species' responses are affected by rank. No sex differences in how primates respond to inequity have been found.

Another social factor that may affect responses to inequity is group membership. This may be caused by differences in group dynamics, colony management, or other factors. However, differences between groups have often been confounded with differences in methodology and procedures among studies. For instance, about half of the current studies require subjects to perform a task to get a reward, while the other half have simply handed the reward for free. This procedural difference predicts responses in the majority of cases (see below for more detail; Brosnan 2008a). Moreover, other smaller methodological differences might also prove significant. For instance, in one set of experiments on chimpanzees, subjects sat across from each other, interacting through a booth while isolated in separate enclosures spaced approximately 1 m apart (Bräuer et al. 2006, 2009), while in another experiment, the chimpanzees sat directly adjacent to each other in a shared enclosure (Brosnan et al. 2005). This represents a substantial change in social arrangement.

Despite these confounds, evidence does exist that, in chimpanzees, at least, social factors affect responses. Brosnan et al. (2005) found that subjects' responses varied depending on the subjects' social group membership. Since Brosnan et al.'s study was performed at a single facility, using the same experimenters and methodology, there were no procedural or methodological differences to confound the results. Pair-housed individuals and those from a large, multimale, multifemale group that had been formed relatively recently (within 8 years of the study) responded to rewards that were less desirable than their partners'. However, subjects from another, similarly sized, social group that had been stable for 30 years showed no such response. Thus, it may be that some feature of these chimpanzees' social environments affected their responses (a phenomenon also known in humans; Clark & Grote 2003), although this was confounded with the length of co-housing (length of co-housing did not affect responses in another study; Bräuer et al. 2006). Hence, one of the goals of the current study was to add to this data set using experimental procedures and arrangements that were identical to the previous study (Brosnan et al. 2005) to test additional chimpanzees from stable, long-term (>30 year) social groups.

As mentioned earlier, a great deal of evidence indicates that a task is necessary, if not sufficient, to elicit a response to inequity (Brosnan 2008a). However, no study has appropriately tested this hypothesis. Among capuchin monkeys, responses to inequity were found in all but one study that involved a task of some sort (Brosnan & de Waal 2003; van Wolkenten et al. 2007; Fletcher 2008; but see Silberberg et al. 2009) and in none of the studies that did not include a task (Dindo & de Waal 2006; Dubreuil et al. 2006; Roma et al. 2006). More importantly, three of these studies used the same group of capuchins (Brosnan & de Waal 2003; Dindo & de Waal 2006; van Wolkenten et al. 2007), which controls for between-group variability and indicates that a task is essential, if not sufficient. Tamarins are more likely to respond negatively to a low-value reward when work is involved than when rewards are given for free, although this, too, was a between-subjects design (Neiworth et al. 2009). Finally, chimpanzees show the same pattern; no response to inequity has been found without a task (Bräuer et al. 2006), and the presence of a task is not sufficient to elicit the response in all groups of chimpanzees (Brosnan et al. 2005; Bräuer et al. 2009). However, in none of these studies were responses to both conditions compared within the same group of subjects. Thus, a second goal of this study was to provide a direct, within-subjects test of the hypothesis that chimpanzees respond more strongly to inequity when a task is involved than when it is not.

Related to this is the question of whether different levels of effort or procedures may also elicit an inequity response. Previous work in capuchin monkeys indicated that the requirement of greater effort exacerbated the response against unequal rewards (van Wolkenten et al. 2007), but there was not a response to the effort difference itself (Fontenot et al. 2007; van Wolkenten et al. 2007). However, no studies exist for other species. Thus, to determine the generalizability of this finding, we included several variations on procedure and effort to determine whether varying these parameters affects responses in chimpanzees.

A final issue is the relative roles of individual versus social expectations. Primates are known to respond negatively to violations of individual expectations, in which an outcome deviates from that anticipated based on previous experience (Tinklepaugh 1928; Reynolds 1961; Wynne 2004; Roma et al. 2006). However, expectations may also be based on their partner's previous experience, or social expectations. In other words, primates may respond more negatively to situations in which their partner got a better reward for completing the same task (social expectations) than to situations in which the better reward was indicated beforehand, but the lesser reward was given following the task (individual expectations). Of studies directly comparing the two, some have indicated a stronger response to social than individual responses (chimpanzees: Brosnan et al. 2005; capuchins: van Wolkenten et al. 2007), while others have found no response to either (capuchins: Silberberg et al. 2009; chimpanzees: the long-term group in Brosnan et al. 2005). Thus, we replicated this comparison here using a new sample of chimpanzees to obtain additional data regarding the issue.

For the current study, we tested same-sex pairs of adult chimpanzees living in social groups of 6–14 members at a facility at which no previous work on inequity had been done. We included conditions used in previous studies (Brosnan et al. 2005; Bräuer et al. 2009) to directly compare responses between facilities (see Methods for a complete list of conditions). We additionally included new conditions to address specific questions. First, we investigated whether basic social factors (sex and rank) affected the response. Second, we addressed the role of a task by explicitly comparing two conditions in which rewards were inequitable, but in one, subjects completed a task (exchange) to receive them, and in the other, rewards were handed to the subjects ‘for free’, with no task required. This is the first direct test of the hypothesis that the presence of a task affects the response to inequity (Brosnan 2008a). Related to this, we addressed whether differences in the level of effort or the procedure used by the experimenter affected chimpanzees' responses when the material outcome was held constant. Finally, we directly compared social and individual expectations to see how these expectations interacted in the chimpanzees' behaviour. This study provides the most comprehensive test to date of the ways in which chimpanzees' behaviour is or is not altered by the presence of some aspect of inequity.

METHODS

Subjects

Subjects included 16 adult chimpanzees, 10 males and six females, housed in social groups at the Michale E. Keeling Center for Comparative Medicine and Research of The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Bastrop, TX, U.S.A. (hereafter referred to as Bastrop). Six of the subjects were wild-born, six were mother-reared in captivity, and four were nursery-reared in peer groups. All subjects were housed in social groups with indoor/outdoor access and extensive environmental enrichment (climbing structures, ropes and swings, barrels, and other toys). All subjects had ad libitum access to primate chow and water and each group received four meals of fruits and vegetables per day, as well as additional puzzle (or occupational) enrichment with food several times per week. At no time prior to or during testing were the subjects deprived of food or water. All subjects participated voluntarily, coming when called to the indoor dens of their living areas for the experiment. Separating subjects out from their social group in this way limited distractions during the experiment.

Chimpanzees were tested in same-sex pairs with a groupmate. Chimpanzees were chosen to participate in the study if they reliably separated and had a potential partner from within their social group (e.g. another individual of the same sex that also reliably separated). Since chimpanzees were not separated from their partners during the study, but shared the same den through the experiment, both partners also had to be willing to separate with each other, which meant that all partnerships were tolerant. Partnerships were not altered during the course of the study, nor were subjects used in more than one partnership. Thus, in cases in which an odd number of chimpanzees of the same sex were available from the same social group, we chose the pair that more easily separated from the rest of the group as a pair (e.g. was the most tolerant).

One of the advantages of this population was that there had been no previous studies on inequity. The only previous related work regarded prosocial behaviour, but only a quarter of our subjects had participated in these tests. Four subjects (1 male, 3 female) had participated as subjects in one or more of these previous studies on prosocial behaviour (Silk et al. 2005; Vonk et al. 2008; Brosnan et al. 2009). One additional subject (female) was a partner in two of the studies (Silk et al. 2005; Vonk et al. 2008), but received no training and made no choices in any test. The remaining 11 subjects had no previous experience in any test related to prosocial behaviour.

Food Preference Tests

We established food preferences of the subjects through a dichotomous-choice test between a low-value food and a high-value food (Brosnan & de Waal 2004). To determine which foods to use, all of our subjects were given a series of these choice tests for a variety of different fruits and vegetables (e.g. grapes, apple pieces, carrot pieces, cucumber pieces, potato pieces). To determine food preferences, subjects were given 10 successive trials in which the experimenter held up one food in each hand, approximately 30 cm apart, centred on the chimpanzee. Presentation of foods alternated from left to right between trials to control for side biases. Subjects could indicate their choice by gesturing to the desired food item with their hand or by moving their head in front of their preferred option (some subjects had previously been trained to use their lips rather than hands to accept food from experimenters). They always received the food they indicated as soon as they made their choice. The chosen food was considered to be the preferred one.

There were two criteria for food selection. First, each chimpanzee had to prefer the same high-value food to the same low-value food at least 80% of the time (8 of 10 trials) in two consecutive sessions to be considered for the food choice pair. Second, after the preference was established, each chimpanzee was given 10 consecutive pieces of the low-value food (in a separate session) to verify that they were willing to consume all 10 pieces of the food when no other foods were available. It was critical that subjects liked the low-value food in ordinary circumstances, as otherwise they would always reject it. Ultimately, all subjects preferred a single grape to a similarly sized piece of carrot, but they ate carrot pieces in the separate session. Therefore, these choices were used throughout, as the high- and low-value food items, respectively.

Training

Prior to the study, all subjects had been trained to exchange an inedible token for a food reward (this food reward was not used in subsequent testing). Tokens consisted of polyvinyl chloride (PVC) pipes 20 cm in length and 1.9 cm in diameter. For an exchange interaction, the experimenter positioned herself at eye level with the subject, showed the token to the chimpanzee, and then gave it to the chimpanzee. After the chimpanzee took the token completely inside the enclosure, the experimenter held her hand outstretched, palm up, with fingertips a few centimetres from the caging. Upon returning the token into the experimenter's hand, the chimpanzee was given a food reward. Subjects met criterion when they returned at least 18 of 20 tokens in a single session; in practise, chimpanzees typically returned the token on all 20 trials.

Testing

Chimpanzees were tested as same-sex pairs with another adult from their social group. All pairs remained the same throughout the course of testing, and no subject participated in more than one pair. All testing was done in the indoor dens that were part of the chimpanzees' living environment. The pair members shared the same den and thus were not separated from each other during the course of testing. No pair was tested more often than once per day.

Each subject underwent a series of eight tests, completing two sessions of each test in the subject role (and two additional sessions in the partner role; see below for details). The order of sessions was randomized for each pair. There were three conditions in which the actions of both individuals, the procedure and the rewards received were the same (the equity test and food control conditions; see Table 1). For these conditions, in which each member of the pair was functionally in the subject role, each pair (instead of each individual) received two sessions of each test, and it was randomly decided which individual went first on the first session (the other went first on the second session). Thus, because of these symmetrical conditions, each pair received a total of 26 test sessions, rather than 32.

Table 1.

Description of experimental conditions

| Abbreviation | Condition name | Exchange | Food | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ETLV | Equity test, low value | Both exchange | Both low value (carrot) | Both subject and partner exchanged for low-value reward |

| ETHV | Equity test, high value | Both exchange | Both high value (grape) | Both subject and partner exchanged for high-value reward |

| FC | Food control | Both exchange | Both see high value (grape) before exchange, receive low value (carrot) following exchange | Prior to exchange, high-value reward was held in front of exchanger, then placed back in container; after successful completion of exchange, exchanger received low-value reward |

| IT | Inequity test | Both exchange | Subject low value (carrot); partner high value (grape) | Partner exchanged for high-value reward and subject exchanged for low-value reward |

| GR | Gift reward | No exchange | Subject low value (carrot); partner high value (grape) | Partner was given a high-value reward for ‘free’ (e.g. without exchange), then the subject was given a low-value reward |

| DT | Delay test | Both exchange, subject waits 10 s after exchange before receiving food | Both high value (grape) | Partner and subject had to exchange for high-value reward, but the subject had to wait 10 s before receiving it |

| DETLV | Differential exchange test, low value | Subject exchanges; partner does not exchange | Both low value (carrot) | Partner was given a low-value reward for ‘free’ (e.g. without exchange) and subject had to exchange for a low-value reward |

| DETHV | Differential exchange test, high value | Subject exchanges; partner does not exchange | Both high value (grape) | Partner was given a high-value reward for ‘free’ (e.g. without exchange) and subject had to exchange for a high-value reward |

Each test session consisted of 50 alternating trials between the partner and subject, so that each individual received 25 trials per test session, beginning with the partner on trial 1. Trials were separated only by the time it took the experimenter to record the response and prepare for the next trial, which was approximately 5 s.

In trials in which exchange was required, the chimpanzee had 10 s to accept the token and another 30 s to complete the exchange (the mean latency for a completed exchange was 4.37 s). Exchanges were considered successful if the subject returned the token to the experimenter's hand. Sharing the token with a partner, pushing the token out of the mesh (away from the experimenter's hand), or placing the token down inside the cage and ignoring it were not considered successful exchanges (see Table 2). When the token had been returned, the experimenter held it up in front of the chimpanzee, but just out of reach, then lifted the correct reward from the container visible to both chimpanzees and gave it to the chimpanzee that had just completed the exchange. If no exchange was required, food rewards were held up in the same manner, but without the token. Subjects occasionally did not take these rewards, again either refusing to accept them, sharing them with their partner, ignoring them, or throwing them away (see Table 2). These results were considered a refusal to accept the reward.

Table 2.

Dependent variables for refusing tokens and rewards

| Chimpanzee behaviour | Token variables | Reward variables |

|---|---|---|

| Refuse | Does not accept token w/in 10 s | Does not accept food w/in 5 s |

| Ignore | Does not return token w/in 30 s | Does not eat food for 30 s |

| Share | Allows partner to take token (no protest) | Allows partner to take food (no protest) |

| Reject | Push out token | Push away food |

To ensure that the presence of the rewards did not cue the subject or create differences in reactions, we placed rewards in containers (one for the low-value food and one for the high-value food), which were always present, full and in the same position, regardless of whether they were used in the session. Responses were immediately recorded on data sheets by the experimenter and all test sessions were videotaped for later analysis and coding.

Test Conditions

The goal of the experiment was to determine how different rewards and different procedures (e.g. level of effort or time delay) affect responses to inequity. To accomplish this, we varied (1) whether the subject and partner had to exchange for the reward, (2) which reward the subject and partner received and (3) whether there was a delay in receiving the reward after completing the test (see Table 1). We designed the study so that tests of different hypotheses varied on only one dimension. However, because there were three factors involved, some of the tests varied on more than one parameter (e.g. different delay and different food rewards). We primarily discuss only those pairs in which a single factor varied, but discuss below three instances in which another comparison was included to test a specific prediction.

To test whether chimpanzees would respond differently when they received different rewards, we included three conditions: an inequity test and two equity control tests. There were no procedural differences between these tests; all individuals exchanged and received a reward in every trial. For the inequity test, both chimpanzees completed an exchange, but the subject received a low-value carrot and the partner received a high-value grape. In the two equity tests, both chimpanzees completed an exchange and both received either the low-value carrot (low-value equity test) or the high-value grape (high-value equity test). To test how subjects responded when their partner got a better reward, we compared their reactions in the inequity test to their reactions in the low-value equity test. To compare how partners responded when the subject got a less preferred reward, we compared their reactions in the partner role in the inequity test to their reactions in the high-value equity test.

To compare social and individual expectations, we included a test that was identical to the low-value equity test except that the subjects both saw a grape prior to every exchange. In this test, the food control test, both chimpanzees were shown a grape until they gestured towards it, but after completing the exchange, they received a low-value carrot. Note that the food control test differed from the low-value equity test only in the way the chimpanzees' attention was drawn to the grape; the container of grapes was present in the same location for every test, including the low-value equity test. We also compared chimpanzees' responses during the food control test and the inequity test, although these two tests differed on two dimensions, to see which reaction was stronger.

To compare the two previous methodologies, we compared the inequity test to a gift reward test, in which the subject received a carrot and the partner received a grape, but both individuals received their respective reward for ‘free’, without having to exchange a token beforehand. Although the gift reward test and the inequity test differed on two parameters (the presence of a task and the length of the interaction; exchange took 4.37 s on average), they are appropriate for comparing methodologies. Note also that the results from the delay test (see details below; 10 s delay) indicated that a delay twice this long was not sufficient to cause a response.

Finally, we examined the effects of effort and procedure. In the delay test, both individuals exchanged and received a grape (as in the high-value equity test), however the subject was given a 10 s delay between returning the token and receiving the reward. We compared the subjects' behaviour in the delay test to their behaviour in the high-value equity test to examine whether the addition of a delay caused changes in their response. It is also possible that a delay is not sufficient to trigger a response, but that a difference in the level of effort is. To investigate this, we developed two tests: (1) a low-value differential exchange test, in which both chimpanzees received a carrot, but the subject received the reward for free, while the partner had to complete an exchange, and (2) a high-value differential exchange test, which was identical, except that both chimpanzees received a grape. These two tests were then compared to the low- and high-value equity tests, respectively, to determine whether the presence of an exchange caused a difference in response. These latter comparisons also differed on two parameters; there was an exchange present in some conditions, and some conditions lasted somewhat longer than others. However, the results of the delay test ruled out the effect of a delay alone on the chimpanzees' responses.

Dependent Variables

For all conditions, the variables of interest were how the subject responded to the food and the token (if present). As discussed above, subjects could refuse to accept the token or the reward by ignoring it, refusing it, rejecting it, or sharing it (see Table 2). Subjects that refused the token or did not complete the exchange were not given a food reward and, therefore, had no opportunity to refuse to accept the reward. In conditions in which exchange was not used, only subjects' interactions with the food were measured. It is possible that these different types of refusals may indicate different levels of arousal on the part of the subjects. However, as the frequency of different types of refusals did not differ between conditions (see Results), analyses were done with the types of refusals combined into a single measure.

We also measured subjects' latency to return the token as an additional measure of hesitation or change in motivation. Latency was measured from the time the chimpanzee grasped the token from the experimenter to the time the experimenter brought it fully back to the other side of the mesh. This was required as chimpanzees sometimes allowed the experimenter to grasp the distal end of the token, but they did not let go of their own end. Thus, the chimpanzee had to fully relinquish the token before the interaction was considered complete.

Finally, we looked at the effects of several basic social factors, including the subjects' sex and rank. All subjects were paired with same-sex partners. For rank, we measured only which chimpanzee was dominant to the other in dyadic interactions with no other chimpanzee present, as these were the conditions under which the test took place. We did not attempt to quantify rank distance differences between the different partnerships.

Statistics

To determine whether chimpanzee behaviour varied between conditions, we conducted omnibus Friedman's tests (because the condition of sphericity was violated, contraindicating parametric tests). Comparisons between males and females were done using nonparametric Mann–Whitney U tests for unrelated samples. Comparisons between conditions within a sex category were done using nonparametric Wilcoxon signed-ranks tests for related samples. For the Wilcoxon tests, some sample sizes differed from the number of subjects as a result of ties. All tests were two tailed.

All analyses were done on the data collected by the experimenter. One-third (33%) of the data were re-coded from the videotapes by coders blind to the hypotheses to verify its accuracy. Coders showed high agreement on whether or not an interaction resulted in a rejection (agreed on 98.5% of trials, Cohen's κ = 0.87).

RESULTS

Overall Refusals

We first investigated whether chimpanzee behaviour varied between the eight conditions used in the experiment. For this analysis, we combined the four types of refusals (refuse, ignore, share, reject) into one measure. Overall, subjects showed significant variation in their refusal rates across conditions (Friedman's test: , P < 0.001). Subjects were less likely to refuse the food than the tokens (Wilcoxon signed-ranks test: T+ = 120, N = 16, P < 0.001). Chimpanzees also showed significant variation in token rejections (only 7 conditions, as no tokens were used in the gift reward condition; Friedman's test: , P = 0.001). Although subjects did refuse foods in some situations, there was no variation based only on food refusals, probably because of the small sample size (Friedman's test: , P = 0.185). To include all eight conditions and all possible mechanisms of refusal, we completed all subsequent analyses using the total refusal rate (refusals to return the token and refusals to accept the food combined).

Sex and Rank Differences

Subjects' rank affected refusal rates. The higher-ranking of the two individuals was more likely to refuse than was the lower-ranking of the two (Mann–Whitney U test: U = 90.5, N1 = N2 = 8, P = 0.015).

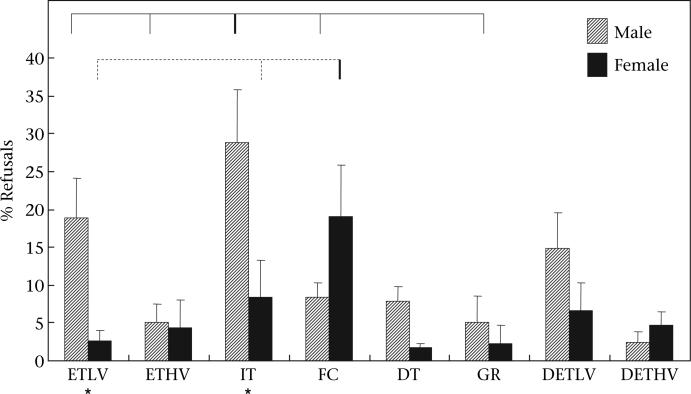

Subjects' sex also affected results. Overall, males were more likely than females to show a reaction to inequity (Mann–Whitney U test: inequity test: U = 106, N1 = 10, N2 = 6, P = 0.022; Fig. 1). This was manifest different reactions to the different conditions. Males were more likely to refuse to participate in the inequity test than in the equity test conditions, regardless of whether the test involved an exchange (low-value equity test: T+ = 55, N = 10, P = 0.005) or not (food control: T+ = 40, N = 9, P = 0.038). Male refusal rates did not differ between the low-value equity test and the food control test (T+ = 33.5, N = 9, P = 0.192).

Figure 1.

Percentage of total refusals (to return the token and to accept the food reward combined) by male and female chimpanzees in each condition. ETLV: equity test, low value; ETHV: equity test, high value; IT: inequity test; FC: food control; DT: delay test; GR: gift reward; DETLV: differential exchange test, low value; DETHV: differential exchange test, high value (see Table 1 for details of each condition). Significant differences (P < 0.05) between sexes within each condition are indicated with an asterisk below the X axis. Significant differences (P < 0.05) between conditions for males (solid line) and females (dashed line) are indicated by a bold hatch.

Females, in contrast, did not differ in their responses to the inequity test and the low-value equity test (T+ = 10, N = 5, P = 0.496). They were, however, significantly more likely to refuse to participate in the food control test than in the inequity test (T+ = 15, N = 5, P = 0.042), and marginally more likely to refuse to participate in the food control test than in the low-value equity test (T+ = 14, N = 5, P = 0.080). Because of this sex difference in response in the inequity test condition, males and females were addressed separately in subsequent analyses, unless otherwise indicated.

Comparing Task and Gift Methodologies

Males responded to inequity only in the context of a task. They were significantly more likely to participate (e.g. refused less often) in the gift reward condition than in the inequity condition (T+ = 55, N = 10, P = 0.005). Females responded only marginally differently between the two conditions (T+ = 10, N = 4, P = 0.066), although this similarity was because they did not often refuse in the inequity condition, not because they refused frequently in the gift reward condition.

Responses to Procedural and Effort Variations

Although food differences are often used to generate inequity, differences in procedure or effort may also lead to the same outcome. Subjects did not react to the delay, refusing no more often in the delay test condition than in the high-value equity test condition (Wilcoxon signed-ranks test: delay test versus high-value equity test: males: T+ = 32.5, N = 9, P = 0.235; females: T+ = 6, N = 4, P = 0.705). Negative reactions may also increase if different tasks are required. However, chimpanzees' responses did not vary dependent on whether the partner had to exchange (the subject always exchanged; Wilcoxon signed-ranks test: low-value equity test versus low-value differential exchange test: males: T+ = 30, N = 10, P = 0.797; females: T+ = 11.5, N = 5, P = 0.276; high-value equity test versus high-value differential exchange test: males: T+ = 18.5, N = 9, P = 0.084; females: T+ = 6, N = 4, P = 0.713).

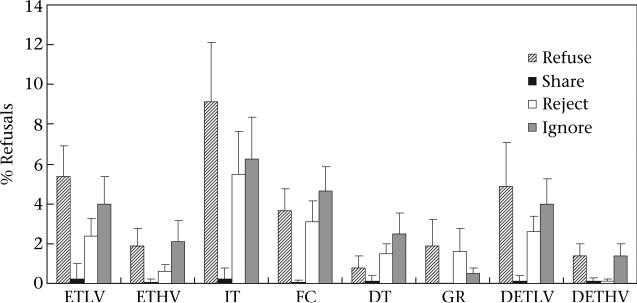

Types of Refusals

Overall, refusal type did not differ between males and females (comparing males' and females' responses across all tests, Mann–Whitney U test: inequity test: refuse: U = 82, N1 = N2 = 8, P = 0.161; share: U = 79, N1 = N2 = 8, P = 0.279; reject: U = 81.5, N1 = N2 = 8, P = 0.161; ignore: U = 79, N1 = N2 = 8, P = 0.279), so we combined the sexes to examine overall differences in refusal in response to food rewards and tokens. There was an overall effect of refusal type (Friedman's test: , P < 0.001; Fig. 2), most likely because of the low rate of sharing in both the food reward and token conditions. Moreover, as with the combined measure, subjects were more likely to refuse to interact at the level of the token than at the level of the food reward; this was the case for refuse (T+ = 28, N = 7, P = 0.018), share (T+ = 21, N = 6, P = 0.026) and reject (T+ = 28, N = 7, P = 0.018), and there was a nonsignificant tendency in this direction for ignore (T+ = 25, N = 7, P = 0.063).

Figure 2.

Percentage of total refusals (to return the token and to accept the food reward combined) for chimpanzees in each condition, broken down by the four types of refusals (refuse, share, reject, ignore). ETLV: equity test, low value; ETHV: equity test, high value; IT: inequity test; FC: food control; DT: delay test; GR: gift reward; DETLV: differential exchange test, low value; DETHV: differential exchange test, high value (see Table 1 for details of each condition).

Latency to Refuse

We examined the latency to return the token to the experimenter (this included only seven conditions, because there was no task in the gift reward condition). There was no overall effect on latency (Friedman's test: , P = 0.395).

Response of the Partner

We compared the refusal rate for each partner in the inequity test (i.e. when the subject received a carrot and the partner received a grape) to their refusal rates in the high-value equity test and to their own refusal rate in the inequity test when they got the lower-value carrot (e.g. when they were the subject, as a control for responses to different rewards in general). Subjects' refusal rates varied across these three conditions (Friedman's test: , P < 0.001). Post hoc comparisons revealed that, as expected, part of this variation was due to a higher refusal rate when individuals received a carrot in the inequity test (subject role) as compared to when they received a grape in the inequity test (partner role: T+ = 76, N = 12, P = 0.004). However, subjects receiving a grape also refused more often when the other chimpanzee got a carrot as compared to when the other chimpanzee also got a grape (e.g. partner role in inequity test versus high-value equity test: T+ = 95, N = 14, P = 0.008). There was no difference in latency between these three conditions (Friedman's test: , P = 0.174). Finally, in the gift reward condition, only one subject refused the grape (she did so four times). Similarly, the majority of refusals by individuals in the partner role of the inequity test were refusals to exchange; only two subjects refused a grape.

DISCUSSION

Chimpanzees in this study responded to inequity between themselves and a partner, either refusing to complete the exchange task or refusing to accept the food rewards when a partner received a better food reward for completing the same task. Subjects were much more likely to refuse tokens than foods, probably because of the challenge of giving up food in one's possession. Thus, in some situations, chimpanzees base their expectations for their own outcomes on their knowledge of the outcomes of others. These results reiterate the importance of social expectations in chimpanzees' decision making.

Unlike in previous studies, we found a sex difference in the response to inequity. Specifically, males responded to violations of social expectations, or inequity, refusing to complete the interaction with the experimenter when the partner received a better outcome (reward; inequity test) more often than when the partner got the same low-value reward (low-value equity test). Females, on the other hand, were more sensitive to violations of individual expectations; they showed no difference in response when they received a lower-value food item than their partner (inequity test) as compared to situations in which both individuals received the same low-value reward (low-value equity test). However, they showed a significantly increased refusal rate when they and their partner were shown a high-value food reward, but were given a low-value reward for completing the task (food control).

This sex difference, which has not been reported previously (chimpanzees: Brosnan et al. 2005; Bräuer et al. 2009; capuchins: van Wolkenten et al. 2007; tamarins: Neiworth et al. 2009), fits with chimpanzee behaviour. Chimpanzee males typically spend their days together, and their interactions are characterized by extensive male–male coalitions and alliances (de Waal 1982, 1992; Goodall 1986). Because of these interactions, males may be sensitive to situations in which they receive less than another male. In humans, such variance is hypothesized to signal a change in one's status relative to the partner, and hence represents a threat to one's position (Tyler & Lind 1992; Lind & Tyler 1998), which may also be true in chimpanzees. Human males are also hypothesized to be more involved in decisions regarding justice than females (e.g. Singer et al. 2006), which could also be true in other primates, including chimpanzees.

Females, in contrast, have a different social structure and so may have different motivations than males. Females in the wild typically forage and spend the majority of their time with only their offspring as company, and are much less engaged in coalitions and alliances than are males (Goodall 1986). Thus, the females may be much less focused on their rank, and the implications of different rewards for their rank.

Chimpanzees' responses also varied dependent upon their rank, with high-ranking individuals refusing more frequently than their lower-ranking partners. Higher-ranking individuals should be more accustomed to receiving the better reward, however, a rank difference has been found in only one other study, and in that study, the chimpanzees' rank did not affect reactions to the equity and inequity conditions differently (Bräuer et al. 2006). The absence of an effect of rank in other studies (Brosnan et al. 2005; see also studies on capuchin monkeys: van Wolkenten et al. 2007) may be because inequity was caused by the experimenter, not a conspecific (Brosnan 2006). Thus, reactions may have been directed at the experimenter rather than the partner.

Our results also affirm the hypothesis that reactions to inequity are more likely when a task of some sort (here, exchange) is used (Neiworth et al. 2009; Brosnan 2008a). Chimpanzees did not respond to inequity of rewards when those rewards were simply handed to the individuals for ‘free’, without a task being required. Although previous correlational data have implied this relationship (see Introduction), our study is the first to provide data based upon counterbalanced conditions within the same series of sessions in the same subjects.

There are several possible explanations for why chimpanzees might be more likely to respond to inequity when a task is involved. A rather prosaic point is that the subjects in the present study were captive, and that they routinely (often daily) receive food hand-outs from humans. These rewards are typically not distributed perfectly evenly (despite caregivers' best efforts), and the primates have undoubtedly learned that their actions do not affect the outcome. In fact, at the Bastrop chimpanzee facility, subjects have been trained in a procedure, cooperative feeding, designed to ensure that all animals, including subordinates, receive a full portion of desirable foods during the four daily enrichment meals. In this procedure, dominant individuals are rewarded with extra treats for not stealing the subordinates' food (Bloomsmith et al. 1994; Schapiro et al. 2003). Thus, one level of inequity is systematically created (extra treats for dominants) to avoid more excessive and variable inequity at another level (dominants stealing the food of others). Chimpanzees at the Bastrop facility are therefore already accustomed to some inequity in a situation with ‘free’ hand-outs, and thus may not expect equity (Bräuer et al. 2006).

A second possible explanation is that primates respond differently to others' rewards acquired by ‘good fortune’ than they do to rewards that require the effort of others to obtain. In a cooperative species, individuals that can assess their relative level of effort and reward as compared to their partners will benefit by ceasing interactions that do not provide a net benefit and continuing those that do. However, even among these species, there is no fitness benefit to reacting against other individuals' good fortune, if these benefits were not gained at one's own expense. This fits with a previous hypothesis that joint efforts require joint payoffs to be sustainable (van Wolkenten et al. 2007). It is possible that the presence of a task when other conspecifics are present triggers these joint behaviours, hence the influence of the task on inequity responses in the present set of experiments. Further tests investigating this response in cooperative versus noncooperative situations or species may help to tease apart these two hypotheses.

This study also demonstrates that, at least under situations of moderate effort, chimpanzees respond to differences in material outcome, not differences in either procedure or the level of effort required to achieve a reward. The presence of a delay (10 s, delay test) between the completion of the task and the receipt of the reward did not affect responses, as compared to the situation in which both chimpanzees were rewarded within the same time frame (no delay; high-value equity test). This delay represented what could be a frustrating inequality in the procedure used to distribute the rewards. However, this condition also involved high-value food items, which may have ameliorated the chimpanzees' reactions. Moreover, 10 s may not have been a sufficient delay; it is well within the capabilities of chimpanzees to delay gratification for this period of time in experimental (Beran & Evans 2006; Dufour et al. 2007) and natural (e.g. meat sharing, Gomes & Boesch 2009) situations.

The chimpanzees also responded similarly when their partner got the same reward as they did for ‘free’ versus when both individuals had to exchange to receive the reward (e.g. low-value differential exchange test versus low-value equity test; high-value differential exchange test versus high-value equity test). These data are in accord with those from capuchin monkeys, which do not respond to differences in effort only (Fontenot et al. 2007; van Wolkenten et al. 2007). Thus, this study, taken with previous work on capuchins, provides strong evidence that effort differentials alone are not sufficient to trigger a response to inequity, either in chimpanzees or, more broadly, among primates.

We unexpectedly found that chimpanzees were more likely to refuse a high-value grape when the other chimpanzee got a lower-value carrot than when the other chimpanzee also received a grape. This is quite interesting in light of the current debate in the literature regarding the role of prosocial preferences in primates' behaviour. Focusing on chimpanzees, several studies explicitly designed to look for prosocial preferences in chimpanzees found no evidence that chimpanzees behave in ways that benefit their partners, even when it costs them nothing (Silk et al. 2005; Jensen et al. 2006; Vonk et al. 2008); prosocial preferences have been found using similar experimental designs in capuchin monkeys (Lakshminarayanan & Santos 2008; de Waal et al. 2008; Takimoto et al. 2009) and marmosets (Burkart et al. 2007), but not in tamarins (Cronin et al. 2009). However, chimpanzees do provide helping behaviour in non-food-related situations (Warneken & Tomasello 2006; Warneken et al. 2007; Yamamoto & Tanaka 2009). Thus, it has been argued that chimpanzees do not show prosocial preferences in the context of food rewards because of the inherent competition (Warneken et al. 2007).

Nevertheless, this paper provides the first experimental evidence that chimpanzees respond behaviourally to receiving more food than a conspecific partner. In the current study, chimpanzees that received a higher-value grape refused to participate more often when the other chimpanzee received an inferior carrot (e.g. partner role in the inequity test) than they did when the other chimpanzee also received a grape (e.g. high-value equity test). This reaction was not seen in previous studies of inequity in primates, either among chimpanzees (Brosnan et al. 2005) or among capuchin monkeys (Brosnan & de Waal 2003; van Wolkenten et al. 2007). These results cannot ascertain the underlying motivations for this behaviour; chimpanzees' responses may have been due to prosocial motivations, but may also have resulted from concern over accepting a higher-value reward in the presence of a conspecific (e.g. potential retaliation).

Responses to inequity have now been investigated in four studies utilizing three different colonies of chimpanzees (see Table 3). Based on this evidence, it is clear that the reaction to inequity is quite variable, both between and within groups. This is not a surprise, as this variability is also found for other social behaviours in primates (e.g. prosocial behaviour: Silk et al. 2005; Jensen et al. 2006; Warneken et al. 2007; social learning: Fragaszy & Visalberghi 1996; Bonnie & de Waal 2007). Several possibilities are emerging as potential mediators. First, the physical arrangement of the subjects may affect social interactions. Moreover, a task is apparently necessary (if not sufficient). Finally, the length of time that the social group has been stable does not appear to be related to subjects' responses. However, this is a coarse measure of social group dynamics, and further studies investigating the effect of relationships in more detail are required.

Table 3.

Comparison of previous studies of inequity completed at Yerkes (Brosnan et al. 2005), Leipzig (Bräuer et al. 2006, 2009) and Bastrop (current study)

| Yerkes |

Leipzig |

Bastrop |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Long-term | Short-term | Pair-housed | Bräuer et al. 2006 | Bräuer et al. 2009 | Males | Females | |

| Group stability (years) | 30 | 8 | Variable | 6 | 6+* | 30+ | |

| Social group | Multimale, multifemale | Pair-housed | Multimale, multifemale | Multimale, multifemale | |||

| Individuals tested | 1 M, 9 F | 4 M, 2 F | 2 M, 2 F | 13, sex not reported | 2 M, 4 F | 10 M, 6 F | |

| Tests | ETLV, IT, FC | ETLV, ETHV, IT | ETLV, IT | ETLV, ETHV, FC, IT, GR, DT, DETLV, DETHV | |||

| Task | Exchange | None | Exchange | Exchange | |||

| Orientation | Side by side | Across† | Across† | Side by side | |||

| Physical interaction | Yes | No (separated)† | No (separated)† | Yes | |||

| Social contrast | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No |

| Individual contrast | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes |

| Effect of rank | No | No | No | Yes‡ | No | Yes | Yes |

ETLV: equity test, low value; ETHV: equity test, high value; FC: food control; IT: inequity test; GR: gift reward; DT: delay test; DETLV: differential exchange test, low value; DETHV: differential exchange test, high value. See Table 1 for details of each test.

Estimated from Bräuer et al. (2006).

Based on the description provided, chimpanzees were in separate enclosures, separated by a booth approximately 1 m wide. Rewards were presented in the booth, so chimpanzees interacted while facing each other through the windows in the booth.

High-ranking chimpanzees were more likely to ignore food and leave the experimental area, but this behaviour did not differ between conditions of equity and inequity.

The response to inequity appears to be widely present in chimpanzees. However, there is variability in the response, probably due to both procedural factors involved in the experiments and social factors like sex, rank and relationship quality. Such variability, found in other social behaviours as well, highlights the flexibility of chimpanzee social cognition, and the importance of studying a large and diverse sample of chimpanzees. We further demonstrate the necessity of a task in eliciting a response to social expectations. However, differences in either the procedure or the amount of effort required to receive a reward did not elicit responses to inequity. Finally, we found that chimpanzees are sensitive to overcompensation, or receiving a greater reward, as well as undercompensation, or receiving a lesser reward. This finding indicates that social expectations can be both positive and negative, and provides the first evidence of behaviour consistent with prosocial outcomes in a food-related experimental task in chimpanzees. It seems likely that this sensitivity to social expectations evolved in the context of sociality, and may be found in a wide variety of other cooperative species.

Acknowledgments

We thank Marina Bushkanets, Patrick Dougall, Carla Heyler and Michael McAleer for help with data coding. S.F.B. was funded by a National Science Foundation Human and Social Dynamics grant (SES 0729244) and a National Science Foundation CAREER award (SES 0847351). Support for the Bastrop chimpanzee colony comes from National Institutes of Health NIH/NCRR U42-RR015090. The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center is fully accredited by American Association for the Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care-International (AAALAC-I). We thank the animal care and enrichment staff for maintaining the health and well-being of the chimpanzees and making this research possible.

References

- Attridge M, Berscheid E. Entitlement in romantic relationships in the United States. In: Lerner MJ, Mikula G, editors. Entitlement and the Affectional Bond: Justice in Close Relationships. Plenum; New York: 1994. pp. 117–148. [Google Scholar]

- Beran MJ, Evans TA. Maintenance of delay of gratification by four chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes): the effects of delayed reward visibility, experimenter presence, and extended delay intervals. Behavioural Processes. 2006;73:315–324. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2006.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloomsmith MA, Laule GE, Alford PL, Thurston RH. Use of training to moderate chimpanzee aggression during feeding. Zoo Biology. 1994;13:557–566. [Google Scholar]

- Bonnie K, de Waal FBM. Copying without rewards: socially influenced foraging decisions among brown capuchin monkeys. Animal Cognition. 2007;10:283–292. doi: 10.1007/s10071-006-0069-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bräuer J, Call J, Tomasello M. Are apes really inequity averse? Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 2006;273:3123–3128. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2006.3693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bräuer J, Call J, Tomasello M. Are apes inequity averse? New data on the token-exchange paradigm. American Journal of Primatology. 2009;7:175–181. doi: 10.1002/ajp.20639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brosnan SF. Nonhuman species' reactions to inequity & their implications for fairness. Journal of Social Justice. 2006;19:153–185. [Google Scholar]

- Brosnan SF. The evolution of inequity. In: Houser D, McCabe K, editors. Neuroeconomics. Emerald; Bingley: 2008a. pp. 99–124. [Google Scholar]

- Brosnan SF. Responses to inequity in nonhuman primates. In: Glimcher PW, Camerer C, Fehr E, Poldrack R, editors. Neuro-economics: Decision Making and the Brain. Elsevier; Amsterdam: 2008b. pp. 285–302. [Google Scholar]

- Brosnan SF, de Waal FBM. Monkeys reject unequal pay. Nature. 2003;425:297–299. doi: 10.1038/nature01963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brosnan SF, de Waal FBM. Socially learned preferences for differentially rewarded tokens in the brown capuchin monkey, Cebus apella. Journal of Comparative Psychology. 2004;118:133–139. doi: 10.1037/0735-7036.118.2.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brosnan SF, Schiff HC, de Waal FBM. Tolerance for inequity may increase with social closeness in chimpanzees. Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 2005;1560:253–258. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2004.2947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brosnan SF, Henrich J, Mareno MC, Lambeth S, Schapiro S, Silk JB. Chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) do note develop contingent reciprocity in an experimental task. Animal Cognition. 2009;12:587–597. doi: 10.1007/s10071-009-0218-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkart J, Fehr E, Efferson C, van Schaik CP. Other-regarding preferences in a nonhuman primate: common marmosets provision food altruistically. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, U.S.A. 2007;104:19762–19766. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710310104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark MS, Grote NK. Close relationships. In: Millon T, Lerner MJ, editors. Handbook of Psychology: Personality and Social Psychology. Vol. 5. J. Wiley; New York: 2003. pp. 447–461. [Google Scholar]

- Colquitt JA, Scott BA, Judge TA, Shaw JC. Justice and personality: using integrative theories to derive moderators of justice effects. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 2006;100:110–127. [Google Scholar]

- Cronin KA, Schroeder KKE, Rothwell ES, Silk JB, Snowdon C. Cooperatively breeding cottontop tamarins (Saguinus oedipus) do not donate rewards to their long-term mates. Journal of Comparative Psychology. 2009;123:231–241. doi: 10.1037/a0015094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dindo M, de Waal FBM. Partner effects on food consumption in brown capuchin monkeys. American Journal of Primatology. 2006;69:1–6. doi: 10.1002/ajp.20362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubreuil D, Gentile MS, Visalberghi E. Are capuchin monkeys (Cebus apella) inequity averse? Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 2006;273:1223–1228. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2005.3433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dufour V, Sterck EHM, Pele M, Theirry B. Chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes) anticipation of food return: coping with waiting time in an exchange task. Journal of Comparative Psychology. 2007;121:145–155. doi: 10.1037/0735-7036.121.2.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fehr E, Rockenbach B. Detrimental effects of sanctions on human altruism. Nature. 2003;422:137–140. doi: 10.1038/nature01474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher GE. Attending to the outcome of others: disadvantageous inequity aversion in male capuchin monkeys (Cebus apella). American Journal of Prima-tology. 2008;70:901–905. doi: 10.1002/ajp.20576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontenot MB, Watson SL, Roberts KA, Miller RW. Effects of food preferences on token exchange and behavioural responses to inequality in tufted capuchin monkeys, Cebus apella. Animal Behaviour. 2007;74:487–496. [Google Scholar]

- Fragaszy DM, Visalberghi E. Social learning in monkeys: primate “primacy” reconsidered. In: Heyes CM, Galef BG, editors. In: Social Learning in Animals: the Roots of Culture. Academic Press; San Diego: 1996. pp. 65–84. [Google Scholar]

- Gomes CM, Boesch C. Wild chimpanzees exchange meat for sex on a long-term basis. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5116. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodall J. The Chimpanzees of Gombe. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press; Cambridge, Massachusetts: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Henrich J, Boyd R, Bowles S, Camerer C, Fehr E, Gintis H, McElreath R. In search of Homo economicus: behavioral experiments in 15 small-scale societies. American Economic Review. 2001;91:73–78. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen K, Hare B, Call J, Tomasello M. What's in it for me? Self-regard precludes altruism and spite in chimpanzees. Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 2006;273:1013–1021. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2005.3417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman D, Knetsch JL, Thaler R. Fairness as a constraint on profit seeking: entitlements in the market. American Economic Review. 1986;76:728–741. [Google Scholar]

- Lakshminarayanan V, Santos LR. Capuchin monkeys are sensitive to others' welfare. Current Biology. 2008;18:R999–R1000. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.08.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lind EA, Tyler TR. The Social Psychology of Procedural Justice. Plenum; New York: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Neiworth JJ, Johnson ET, Whillock K, Greenberg J, Brown V. Is a sense of inequity an ancestral primate trait? Testing social inequity in cotton top tamarins (Saguinus oedipus). Journal of Comparative Psychology. 2009;123:10–17. doi: 10.1037/a0012662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Range F, Horn L, Viranyi Z, Huber L. The absence of reward induces inequity aversion in dogs. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, U.S.A. 2008;106:340–345. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810957105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds GS. Behavioral contrast. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behaviour. 1961;4:441–466. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1961.4-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roma PG, Silberberg A, Ruggiero AM, Suomi SJ. Capuchin monkeys, inequity aversion, and the frustration effect. Journal of Comparative Psychology. 2006;120:67–73. doi: 10.1037/0735-7036.120.1.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schapiro SJ, Bloomsmith MA, Laule GE. Positive reinforcement training as a technique to alter nonhuman primate behavior: quantitative assessments of effectiveness. Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science. 2003;6:175–187. doi: 10.1207/S15327604JAWS0603_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silberberg A, Crescimbene L, Addessi E, Anderson JR, Visalberghi E. Does inequity aversion depend on a frustration effect? A test with capuchin monkeys (Cebus apella). Animal Cognition. 2009;12:505–509. doi: 10.1007/s10071-009-0211-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silk JB, Brosnan SF, Vonk J, Henrich J, Povinelli DJ, Richardson AS, Lambeth SP, Mascaro J, Schapiro SJ. Chimpanzees are indifferent to the welfare of unrelated group members. Nature. 2005;437:1357–1359. doi: 10.1038/nature04243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer T, Seymour B, O'Doherty JP, Stephan KE, Dolan RJ, Frith CD. Empathetic neural responses are modulated by the perceived fairness of others. Nature. 2006;439:466–469. doi: 10.1038/nature04271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takimoto A, Kuroshima H, Fujita K. Capuchin monkeys (Cebus apella) are sensitive to others' reward: an experimental analysis of food-choice for conspecifics. Animal Cognition. 2009;13:249–261. doi: 10.1007/s10071-009-0262-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tinklepaugh OL. An experimental study of representative factors in monkeys. Journal of Comparative Psychology. 1928;8:197–236. [Google Scholar]

- Tyler TR, Lind EA. A relational model of authority in groups. In: Zanna M, editor. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. Vol. 25. Academic Press; New York: 1992. pp. 115–191. [Google Scholar]

- Vonk J, Brosnan SF, Silk JB, Henrich J, Richardson AS, Lambeth SP, Schapiro SJ, Povinelli DJ. Chimpanzees do not take advantage of very low cost opportunities to deliver food to unrelated group members. Animal Behaviour. 2008;75:1757–1770. doi: 10.1016/j.anbehav.2007.09.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Waal FBM. Chimpanzee Politics: Power and Sex Among Apes. Johns Hopkins University Press; Baltimore: 1982. [Google Scholar]

- de Waal FBM. Coalitions as part of reciprocal relations in the Arnhem chimpanzee colony. In: Harcourt AH, de Waal FBM, editors. Coalitions and Alliances in Humans and Other Animals. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 1992. pp. 233–258. [Google Scholar]

- de Waal FBM, Leimgruber K, Greenberg A. Giving is self-rewarding for monkeys. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, U.S.A. 2008;105:13685–13689. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807060105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walster [Hatfield] E, Walster GW, Berscheid E. Equity: Theory and Research. Allyn & Bacon; Boston: 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Warneken F, Hare B, Melis AP, Hanus D, Tomasello M. Spontaneous altruism by chimpanzees and young children. PLoS Biology. 2007;5:e184. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warneken F, Tomasello M. Altruistic helping in human infants and young chimpanzees. Science. 2006;311:1301–1303. doi: 10.1126/science.1121448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiesenfeld BM, Swann WB, Jr, Brockner J, Bartel CA. Is more fairness always preferred? Self-esteem moderates reactions to procedural justice. Academy of Management Journal. 2007;50:1235–1253. [Google Scholar]

- van Wolkenten M, Brosnan SF, de Waal FBM. Inequity responses in monkeys modified by effort. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, U.S. A. 2007;104:18854–18859. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707182104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wynne CDL. Fair refusal by capuchin monkeys. Nature. 2004;428:140. doi: 10.1038/428140a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto S, Tanaka M. How did altruism and reciprocity evolve in humans? Perspectives from experiments on chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes). Journal of Interaction Studies. 2009;10:150–182. [Google Scholar]

- Zizzo DJ, Oswald A. Are people willing to pay to reduce other's incomes? Annales d'Economie et de Statistique. 2001;63–64:39–62. [Google Scholar]