Abstract

The human perceptual-motor system is tightly coupled to the physical and informational dynamics of a task environment. These dynamics operate to constrain the high-dimensional order of the human movement system into low-dimensional, task-specific synergies—functional groupings of structural elements that are temporarily constrained to act as a single coordinated unit. The aim of the current study was to determine whether synergistic processes operate when coacting individuals coordinate to perform a discrete joint-action task. Pairs of participants sat next to each other and each used 1 arm to complete a pointer-to-target task. Using the uncontrolled manifold (UCM) analysis for the first time in a discrete joint action, the structure of joint-angle variance was examined to determine whether there was synergistic organization of the degrees of freedom employed at the interpersonal or intrapersonal levels. The results revealed that the motor actions performed by coactors were synergistically organized at both the interpersonal and intrapersonal levels. More importantly, however, the interpersonal synergy was found to be significantly stronger than the intrapersonal synergies. Accordingly, the results provide clear evidence that coacting individuals can become temporarily organized to form single synergistic 2-person systems during performance of a discrete joint action.

Keywords: joint action, interpersonal coordination, motor synergies, motor control, uncontrolled manifold

We often observe individuals expertly coordinating their bodily movements with other individuals around them. Whether crossing a road with a group of individuals at a cross-walk, moving a table and chairs with friends or family, or shaking hands with a colleague, individuals frequently perform social behavioral coordination in a robust and flexible manner, with seemingly little or no effort. Despite it being well known that performing social motor activities is a fundamental property of ongoing human behavior (e.g., Bekkering et al., 2009; Marsh, Richardson, & Schmidt, 2009; Richardson, Marsh, & Schmidt, 2010; Riley, Richardson, Shockley, & Ramenzoni, 2011; Schmidt & Richardson, 2008) the exact nature of how coactors are able to carry out these motor acts remains incompletely understood. Several researchers have argued that the coordinated motor control that takes place during joint or social actions might be synergistic (Anderson, Richardson, & Chemero, 2012; Richardson et al., 2010; Riley et al., 2011). The goal of the present work was to further test this interpersonal synergy hypothesis in the context of a social coordination task involving precision, discrete movements.

The human perceptual-motor system is tightly coupled to the physical and informational dynamics of a task environment. These dynamics operate to constrain the high-dimensional order of the human movement system (Bernstein, 1967) into low-dimensional, task-specific synergies (Kelso, 2009; Turvey & Fonseca, 2009). Here the term synergy is used to refer to a functional grouping of structural elements (neurons, muscles, limbs, individuals, etc.) that are temporarily and functionally constrained to act as a single coordinated unit. Evidence that the human movement system is organized synergistically has been demonstrated in a wide range of individual (i.e., nonsocial) motor tasks including grasping behaviors (Jacquier-Bret, Rezzoug, & Gorce, 2009), piano playing (Furuya & Kinoshita, 2008), and pistol shooting (Scholz et al., 2000). In each case, the movement degrees of freedom (DoF) required for task performance were found to be temporarily coupled, such that the control or modulation of any one DoF functionally constrains and regulates the movement of the other DoF, thereby reducing the dimensionality of the system as a whole and providing a source of goal-relevant error correction by means of reciprocal compensation among the components.

The interpersonal synergy hypothesis has also received empirical support. Research has demonstrated that, rhythmic interpersonal coordination exhibits the same behavioral dynamics as intrapersonal, interlimb coordination (see Schmidt & Richardson, 2008 for a review) and that individuals appear to stabilize movement fluctuations during a continuous, interpersonal rhythmic movement task at a collective level (Black, Riley, & McCord, 2007a). More recently, Ramenzoni, Davis, Riley, Shockley, and Baker (2011) provided evidence for the interpersonal synergy hypothesis by demonstrating that the behavioral control exhibited by a pair of individuals performing a continuous, interpersonal, postural targeting task also appears to be modulated in a collective or synergistic manner. More empirical work is required to verify this hypothesis, however, especially with respect to discrete joint action tasks. No prior research studies have investigated whether discrete joint-action movement tasks, such as when two individuals shake hands or pass an object, are synergistic.

In light of the differences between the control of continuous and discrete movements (e.g., Ghez et al., 1997; Hogan & Sternad, 2007; Howard, Ingram, & Wolpert, 2011; Huys, Studenka, Rheaume, Zelaznik, & Jirsa, 2008; Spencer, Verstynen, Brett, & Ivry, 2007; Torre & Balasubramaniam, 2009), it is important to test the interpersonal synergy hypothesis in the context of a discrete task in order to determine how general the synergistic nature of joint action may be. Coordination that occurs between two coacting individuals (effective, successful, or otherwise) does not always have to be synergistic—it can simply reflect the coincidental activity of two individuals coordinating their movement independently (i.e., movement control and coordination are determined at an individualistic, rather than collective level). Empirically determining whether discrete interpersonal behaviors are synergistic is therefore an important and necessary endeavor. Accordingly, the objective of the current study was to investigate whether the motor behavior that occurs between two coacting individuals performing a discrete joint-action task is synergistically organized.

Motor Synergies

To be considered synergistic, a multi-DoF action should exhibit two key characteristics: dimensional compression (DC) and reciprocal compensation (RC) (Riley et al., 2011). DC refers to the processes of intercomponent constraints that couple the relevant DoF together and effectively reduce overall motor system dimensionality. DC, coupled with the motor abundance characteristic of the human movement system (Latash, 2012), brings about RC, which refers to how the movement of one motor DoF is connected or dependent on the movement of others in a way that allows the system to adaptively react to movement noise or unexpected changes. In other words, if one DoF is perturbed during a task, a separate (and sometimes remote) DoF can be used to compensate for the perturbation in order to bring about successful task completion. Together, DC and RC make it possible to modulate the movement of all components necessary for an action by controlling only one of them (Kugler, Kelso, & Turvey, 1982; Riley et al., 2011; Turvey, 2007) or by controlling a higher-order collective parameter (Black et al., 2007a; Riley et al., 2011). These complementary processes reduce the overall dimensionality of a goal directed movement while ensuring the system’s flexibility to resist and overcome unexpected situational constrains or perturbations via nonlocal component adaptations (Kelso, Tuller, Vatikiotis-Bateson, & Fowler, 1984; Riley et al., 2011).

Research by Kelso, Tuller, Vatikiotis-Bateson, and Fowler (1984) investigating the interconnections among the DoF of the vocal apparatus during speech production exemplifies these synergistic processes. In that study, a participant sat on a chair and uttered syllables multiple times while the movement of different vocal effectors was measured. Kelso and colleagues introduced a random perturbation on some trials—they pulled the participant’s jaw down during the utterance. If the perturbation occurred at the beginning of the trial the participant was able to successfully utter the syllable. The correction necessary to complete the utterance successfully did not come from correcting the position of the jaw, but rather from changing the position of the tongue and the lips. That is, the intercomponent connections inherent to the speaking synergy (DC) made it possible for the person to successfully compensate for the unexpected perturbation with another interconnected DoF (RC).

Experimentally Investigating Synergies and the Uncontrolled Manifold

As noted, not all actions require a synergy to be successful. It is also the case that synergies can differ in strength and that the interconnected processes or behavioral outcomes that define a synergistic behavior can change over time (with practice, e.g.). The goal of several motor control researchers over the last several decades has, therefore, been to develop a set of methods that enable quantification of the presence and strength of a synergy (e.g., Cusumano & Cesari, 2006; Latash et al., 2002; Müller & Sternad, 2004, 2009; Scholz & Schöner, 1999). Experimentally testing whether a motor action is a synergy can be challenging both practically and mathematically. This is because (a) one may need to record the same action repeatedly over a long period of time and (b) the computational complexity involved in modeling the degree of DC and RC becomes incredibly difficult when more than five or six components are involved (Domkin, Laczko, Jaric, Johansson, & Latash, 2002). A task that requires the use of an unrestrained human arm considered only at the level muscular level, for example, involves 26 DoF. If each muscle is controlled independently, this would require a complex control system of 26 variables that would need to be controlled continuously. For a two-arm task or a joint-action task involving unrestrained arm movements of each individual the complexity of control rises twofold. To experimentally investigate motor synergies researchers must therefore employ simplified motor control tasks (e.g., restricting possible movement in some planes) that are not too taxing for participants and can be performed in a relatively short period of time. An excellent example of how this can be achieved was provided by Domkin, Laczko, Jaric, Johansson, and Latash (2002) who devised an experimental task in which a single participant bent both his or her arms from a lateral, outstretched position to the forward frontal position such that a pointer located on the right hand was connected with a target located on the left hand. They asked their participants to repeat this movement several times and looked at the effects of learning (repetitive performance) by comparing the configuration of the joint angles at the beginning of the experiment to that at the end. They were particularly interested in whether the control employed to ensure the meeting of the pointer and target was manifested at each arm separately, or if the two arms were controlled together as a single, higher-order synergy.

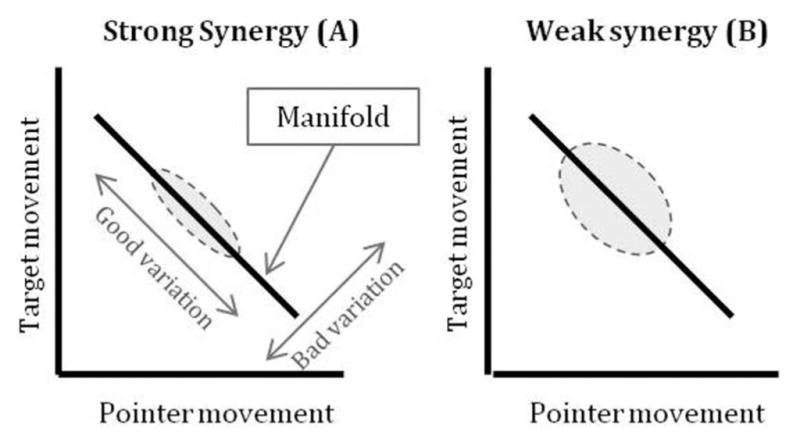

To determine whether task control was organized at the unimanual or bimanual level, Domkin et al. (2002) employed the uncontrolled manifold (UCM) method. The UCM method, first introduced by Scholz and Schöner (1999), enables one to analyze data and compare different hypotheses about synergistic organization. This method is useful in simple tasks in which successful completion can be clearly measured. For example, in the task employed by Domkin et al. (2002) successful completion is achieved by bringing the tip of the pointer to the intended target. For such tasks, a task space of all possible end-effector positions can be created in which a subspace or manifold within the task space specifies all of the joint-angle configurations (i.e., between elbows, wrists, shoulders) that result in successful task completion (Scholz & Schöner, 1999). Variation along this manifold does not need to be corrected, hence the name UCM. Variation along this manifold results in task completion and is referred to as compensatory or uncontrolled variation. Variation that is orthogonal to that manifold is considered uncompensated because it corresponds to variation that negatively affects the ability to successfully complete the task. A synergy is said to be present when the ratio of uncontrolled variation to orthogonal variation is above one. Figure 1 illustrates an example task subspace and manifold (in this case a line).

Figure 1.

Schematic depiction of a task space with either (A) a strong synergy present or (B) a weak synergy present.

RC is addressed explicitly by the UCM method in terms of the variation occurring along the UCM—the very notion is that if the overall task variable remains constant despite variation among the component DoF, then that variation must be structured in a compensatory manner. When comparing different DoF configuration hypotheses at different organizational levels (i.e., interpersonal vs. intrapersonal), the UCM method also addresses DC, albeit less directly. The identification of a synergy using the ratio of uncontrolled to orthogonal variation means that component DoF have been effectively reduced because they become interdependent or coupled in order to achieve the reciprocal compensation that preserves a desired value of the macroscopic task variable.

Domkin et al. (2002) used the UCM method to test three competing hypotheses.

Hypothesis 1 (H1): The target and pointer position are stabilized by interactions among the joints of both arms.

Hypothesis 2 (H2): The target position is stabilized by controlling the joints in the left arm.

Hypothesis 3 (H3): The pointer is stabilized by controlling the joints in the right arm.

They found that a bimanual synergy (H1) was formed in order to complete the task effectively, and that this bimanual synergy was stronger than each of the unimanual synergies (H2 and H3). In other words, the two-arm-system was controlled as a unitary system (i.e., DC) and worked to bring about successful completion of the task by restricting variation perpendicular to the UCM— variation that would lead to task failure—while allowing variation along the UCM (i.e., RC).

Since the UCM method was introduced by Scholz and Schöner (1999) it has been employed to determine the synergistic character of a range of individual motor tasks. For instance, research has explored the presence and strength of synergistic organization in tasks such as standing from a seated position (Scholz & Schöner, 1999), pointing at targets of varying diameters (Tseng, Scholz, Schöner, & Hotchkins, 2003), and multifinger force production (Gorniak, Zatsiorsky, & Latash, 2007; Kang, Shinohara, Zatsiorsky, & Latash, 2004; Scholz, Danion, Latash, & Schöner, 2002). Other studies have examined the effects of unexpected perturbations on movement synergies during the execution of an action (Scholz et al., 2007) and at the differences that exist between movement synergies formed by typically developed people and those with motor disorders (Black, Smith, Wu, & Ulrich, 2007b; Latash & Anson, 2006; Reisman & Scholz, 2003; Scholz, Kang, Patterson, & Latash, 2003). Müller and Sternad (2004) developed a similar method for detecting and describing synergies that employs three types of variable contribution (stochastic noise, task tolerance, and covariation between central variables) instead of two (compensated variance vs. uncompensated variance). This method (TNC) has also shown the presence of intrapersonal synergies in multiple contexts (Cohen & Sternad, 2009; Müller & Sternad, 2004, 2009; Ronsse, Sternad, & Lefèvre, 2009).

Joint Action Research

An increasing amount of theoretical work has been developed with the idea of interpersonal synergies enhancing the outcome of different social interactions, such as having conversations (Fusaroli, Rączaszek-Leonardi, & Tylén, 2014) and in team sport interactions (Passos et al., 2009). A great deal of previous research on joint-action and social movement coordination has provided clear evidence that the movements of copresent and interacting individuals are coordinated in the service of mutual task goals (see, e.g., Black et al., 2007a; Marsh et al., 2009; Sebanz & Knoblich, 2009). Of particular significance is that even though the visual, haptic, or auditory information that couples the movements of coacting individuals is much weaker than the biomechanical constraints inherent to interlimb coordination of an individual, the same coordination dynamics typically are found in interpersonal coordination (Schmidt & Richardson, 2008). This phenomenon has been demonstrated in simple rhythmic coordination tasks such as when participants are instructed to coordinate the swinging of handheld pendulums (Schmidt, Bienvenu, Fitzpatrick, & Amazeen, 1998) or rocking chairs (Richardson, Marsh, Isenhower, Goodman, & Schmidt, 2007). In these tasks, pairs of participants show the same movement dynamics exhibited by individuals in interlimb movements (see Schmidt & Richardson, 2008 for a review). For example, coacting individuals are constrained to in-phase and antiphase patterns of coordination with increased movement frequency resulting in a decrease in the stability of coordination.

Finding that the same rhythmic coordination dynamics are observed across individuals and pairs, however, only provides indirect support for the potential presence of synergies at an interpersonal level. Black, Riley, and McCord (2007a) conducted a UCM study in order to more directly determine whether interpersonal rhythmic coordination is synergistic. Participants sat next to each other facing the same direction, each holding a pendulum in one hand. They looked at the other person’s pendulum throughout each trial. The pairs were instructed to coordinate pendulum swinging in either an in-phase or antiphase manner with the period (timing) of movement dictated by a metronome. Using relative phase stabilization as the hypothesized task variable for the UCM analysis, Black et al. determined that the ratio of compensated to uncompensated variance was greater for the interpersonal synergy, providing direct support for the hypothesis that rhythmic interpersonal coordination exhibits synergistic characteristics at an interpersonal level.

Ramenzoni et al. (2011) also found evidence that interpersonal movement coordination can be synergistically organized. Instead of employing a rhythmic coordination task like Black et al. (2007a), Ramenzoni and colleagues devised a continuous, two-person, suprapostural targeting task. In their first experiment, one participant was instructed to stand and hold a pointer inside a target circle (without touching its sides), and the target circle was held by another standing participant (coactor). Task difficulty was manipulated by varying the target circle diameter (the smallest target was the most difficult condition). For the second experiment they added another dimension of task difficulty by requiring participants to sometimes perform the task in a less stable (and thus more difficult) stance. Principal component analysis (PCA) was applied to determine the degree of DC at both individual and interpersonal levels. Consistent with the interpersonal synergy hypothesis, this analysis demonstrated that in order to account for 90% of movement variation six components were needed at the intrapersonal level compared to only four at the interpersonal level. That is, DC was greater when considering the DoF of both participants as a single, interpersonal, synergistic system compared to when the DoF of each individual were considered as independent, yet coordinated, intrapersonal synergies.

Present Study

The objective of this study was to use the UCM method to directly determine whether synergistic processes constrain and organize behavior in a simple, discrete joint-action task. As noted previously, control of discrete tasks may differ in important ways from control of continuous tasks. To date, no research has used UCM to assess the extent to which the movement of two coacting individuals performing a discrete joint-action task is synergistic. By examining a discrete joint-action task, as opposed to a continuous task, the current study therefore has the potential to improve scientific understanding of social coordination in general. Moreover, discrete joint action tasks are very typical of the kinds of interactive behaviors carried out between individuals every day (e.g., passing a plate when loading a dishwasher or throwing a ball to someone).

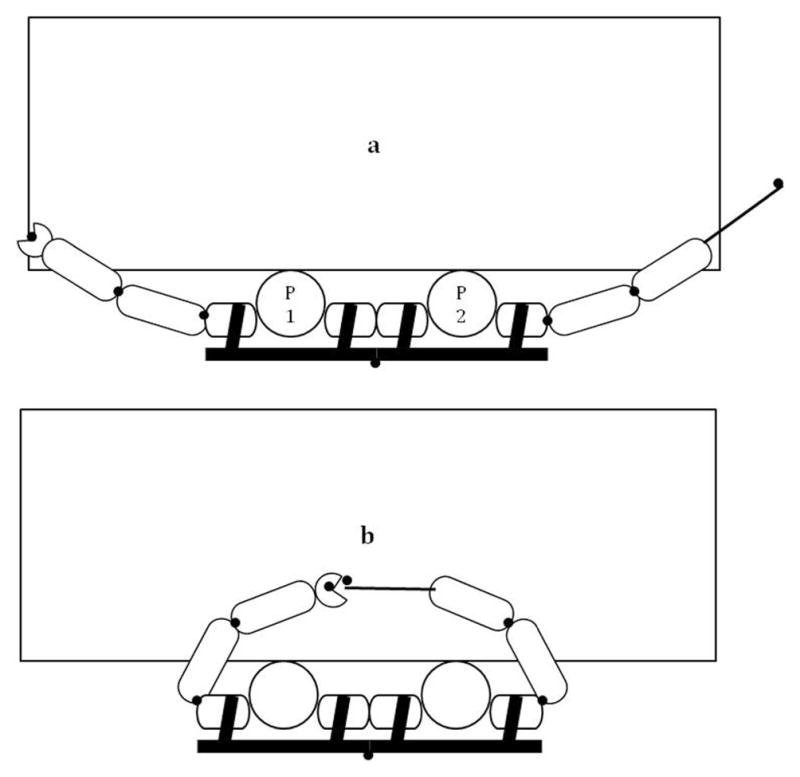

Given the qualitative similarity to the simple joint action of shaking hands with another person, a two-participant version of the Domkin et al. (2002) target-pointing task was employed. Pairs of participants sat next to each other and each used one arm to complete the two-dimensional pointer-to-target task together (see Figure 2). By determining the UCM ratio of compensated-to-uncompensated variation at the interpersonal and intrapersonal arm-system levels, the study tested the hypothesis (H1) that successful task completion is stabilized by the collective and nonadditive interaction of each participant’s arm (i.e., participants form a unitary interpersonal synergy) against the hypotheses (H2 and H3) that successful task completion is stabilized by participants controlling the joints in their respective arm (i.e., intrapersonal left and intrapersonal right) in a coordinated, yet additive, manner (i.e., the coordinated interpersonal action is not a synergy).

Figure 2.

Bird’s-eye view of the experimental set-up with Participant 1 sitting on the left side using his or her left arm to hold the target and Participant 2 using his or her right hand to hold the pointer at (a) the initial and (b) objective position. Black dots represent markers placed on the participants and on the back of the chairs.

Method

Participants

Thirty students (15 pairs; 13 males, 17 females) from the Center for Cognition, Action, and Perception at the University of Cincinnati participated in the experiment. Participants ranged in age from 19 to 34 years, were all right-handed, and had healthy motor function and normal or corrected-to-normal vision. Participants were matched within pairs by height.

Apparatus

Participant pairs sat in rigid chairs that were constructed to accommodate adjustable shoulder straps. The chairs were positioned side-by-side in front of a 74 cm high table. The participant seated to the left (Participant 1) held the target, a plastic semicircle if 11.1 cm diameter, in her/his left hand. The target was taped to the participant’s left index finger and thumb. The participant located to the right (Participant 2) held a pointer on her/his right hand. The pointer was a 23 cm long wooden stick that was taped to her/his right index finger.

An optical, marker-based, Optotrak Certus motion tracking system (Northern Digital, Inc.) was employed to track the three-dimensional (3D) position of arm joints. Markers were placed on standard bony landmarks that correspond to participants’ shoulder (the acromion), elbow (lateral epicondyle), and wrist (between the radius and ulnar bones; Domkin et al., 2002). Additionally, markers were placed at the tip of the pointer and the center of the target. Finally, a marker was placed between the two chairs at the level of the participants’ shoulders so that the position of all other markers could be rescaled for analysis (see below for more details). Position data for each marker were recorded at a sampling rate of 100 Hz and filtered using a second-order Butterworth infinite impulse response (IIR) filter with a cutoff frequency of 10 Hz.

Procedure

Upon entering the experimental room, participants were asked to sit side-by-side in the chairs and their shoulders were strapped securely in place. The table was then placed in front of them and the motion tracking markers were attached to each participant. The participants were informed that the task objective was to bring the pointer to the center of the target as fast and as accurately as possible. They were informed that the straps were placed on their shoulder to prevent the use of their torso during completion of the movement. Additionally, they were instructed to perform movements parallel to the table so as to prevent movement in the vertical plane. Participants were instructed to open their arms until they were flush with the end of the table (thereby enabling full arm extension) and to wait for a verbal command to perform the movement quickly and accurately. They were then allowed to practice the movement two times, so the experimenter could verify that they were in fact limiting their movements to the sagittal and coronal planes (see Figure 2).

Pairs completed 300 trials across two separate sessions, with both sessions performed in 1 week. In the first session pairs completed two sequences of 100 trials each, with a pause of at least 5 min between each sequence. They were also allowed breaks every 25 trials if they desired. In the second session pairs completed another 100 trials. Following Domkin et al. (2002), only the first and last 15 successfully completed trials were used for analysis. More specifically, the first 15 successfully completed trials from the first 30 trials of the first 100 trial sequence (pretest) and last 15 successfully completed trials within the last 30 trials of the third 100 trial sequence (posttest) were used in the analyses.1

Measures

The same measures and UCM model calculations employed by Domkin et al. (2002) were used for the current analyses.2

Kinematic variables

The kinematic measures detailed below were calculated as preliminary measures, both to assess whether the shoulder straps had the intended consequence of reducing the movement of the torso and as preparation for the UCM calculations. Movement time was based on the calculated initiation and termination times, defined respectively as the moment where the velocity of the target and pointer sensors exceeded 10% of the maximum velocity over the whole trial and the point at which the velocity fell below 10% of its maximum. Both initiation and termination times were calculated for both arms and when these times were different the earliest initiation time and the latest termination time were adopted as respective trial beginning and end markers. All measures reported below were calculated with respect to these movement period markers.

The final movement position was considered to be 100 ms after the termination time of the movement (Domkin et al., 2002). It was at this final movement position that the constant and variable errors were calculated as a function of the target and pointer positions in the x (coronal) and y (sagittal) planes. Constant error was calculated for each plane separately and was determined as the spatial separation between the pointer and target at the final movement position. This measure quantified successful completion and variability of placement at the termination of the movement. Variable error was the SD of the constant error in individual trials with respect to the mean position of the pointer sensor in each plane. This variable provided a measure of variability at the meeting point in each trial compared with the other trials.

The two-dimensional (x, y) meeting point position (where the pointer and the target sensors actually met in the final movement position) was also examined within the movement plane. Because there was inherent variability in how participants performed the task from trial-to-trial (even when they completed it successfully), it was necessary to assess how scattered the meeting point was within the movement plane. The variability of the meeting point was calculated as the difference in planar distance of the meeting points in the individual trials from the averaged planar distance across the 15 trials of the respective trial block.

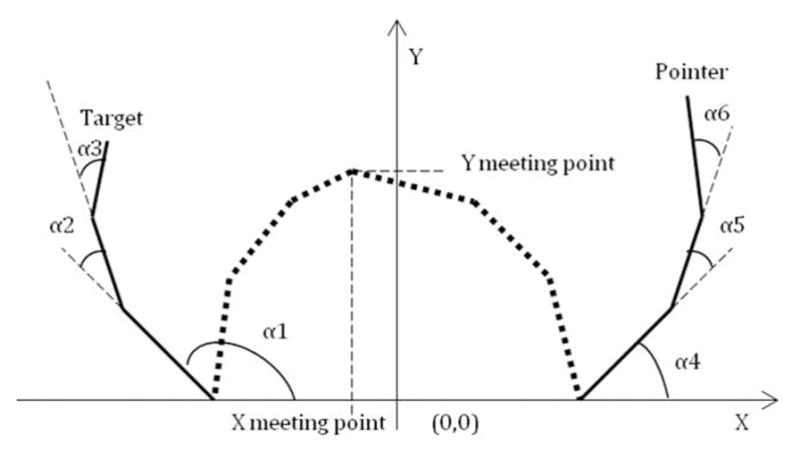

The average shoulder displacement of participants was 1.59 cm. This is consistent with the 1 cm displacement found by Domkin et al. (2002) and indicates that the shoulder straps on the chairs did largely prevent participants from using torso motion to complete the task. Thus, only the three arm joints (shoulder, elbow, and wrist) for each participant needed to be considered. The contribution of each joint to the movement was first determined by calculating the range of motion of each joint. Range of motion was calculated as the difference between the largest and the smallest joint angle during each movement (i.e., between the initial and final movement markers defined above). As was the case in Domkin et al., joint angles were calculated using approximations of arm segment lengths obtained by calculating the Euclidian distance between the markers at the joints (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Schematic version of the way joint angles (α1: Participant 1’s shoulder, α2: P1’s elbow, α3: P1’s wrist, α4: P2’s shoulder, α5: P2’s elbow, and α6: P2’s wrist) were calculated for the task. The thick lines represent the arm sections of each participant’s arm. Also captured is the way the meeting point was determined for each plane.

Total joint variance of joint configuration

Because trials varied in duration, angular trajectories were time-normalized using a cubic spline interpolation within the pre- and the posttest blocks. The movement time in each trial was divided into 10 even time bins. This normalization made direct comparison between trials possible.

The mean joint configuration was then computed for each time bin and also across the whole trial. This measure indexed how much each joint moved and contributed to completing the task. Joint variance was the variable considered to be stabilized in the formation of the synergy and was therefore the main variable used for the UCM analysis detailed below. Finally, the deviation of the mean configuration of each time bin [Δk(t)] from the mean for the whole trial was calculated and then divided by the number of trials in the block (i.e., 15) and the number of DoF available (six when considering both arms simultaneously and three when considering each arm separately) to obtain the total variance per DoF of joint configuration (VTOT) for each trial,

VTOT quantifies the degree of variability present in each trial when compared with the other trials in the block. Because it is dependent on the DoF used, it can be calculated at both the interpersonal (H1) and intrapersonal (H2 and H3) levels.

Control hypotheses and task variables

Following Domkin et al. (2002), three stabilization hypotheses were tested. The first hypothesis (H1) was whether the necessary joint stabilization needed to complete the task was distributed across both arms (interpersonal hypothesis). In contrast, the second hypothesis (H2) was that control focused on stabilizing the target and, therefore, that the joint configuration of the left arm of Participant 1 was central to task performance (intrapersonal left). The third hypothesis (H3) was that the right arm pointer (Participant 2) stabilization was the focus of control (intrapersonal right).

VTOT was partitioned into the variance that occurred along the uncontrolled manifold (VUCM) subspace—which is considered to be compensated variance—and the variance occurring orthogonal (VORT) to this subspace—which is considered uncompensated. VUCM and VORT were calculated for each time bin of each trial in the pre- and posttest blocks for each pair for each hypothesis level. The detailed computations can be found in the Appendix.

Finally, the ratio of VUCM to VORT was calculated for each hypothesis (by averaging VUCM and VORT across pairs and time bins). If the variance along the UCM was found to be higher than that found along the orthogonal task-space dimensions (ratio >1), the organization of the movement DoF would be considered synergistic. If this ratio is higher in H1 compared with H2 and H3, then the interpersonal movement system would not only be considered synergistic, but would be the strongest synergy and the one that best characterizes the organization of the task-directed movement system. In other words, the stabilization necessary to complete the task would be found to be more strongly dependent on the movements of both participants (as one single interpersonal synergistic system) as opposed to the separate stabilization of each arm [two synergistic (arm) systems interacting].

Results

Due to equipment malfunction and marker occlusion issues, data from two pairs could not be analyzed. Thus, the following analysis and results include data from only 13 of the 15 pairs recruited (i.e., N = 13).

Movement Kinematics

A paired-samples, one-tailed t test revealed an expected significant decrease in mean movement time from pretest to posttest, Mpretest = 1.36 s, Mposttest = 1.20 s; t(12) = 1.91, p = .04.

With regard to task accuracy, paired samples t tests on the constant errors in the final position in the x and y planes and as a function of test block revealed no significant differences for these dependent measures, all t(12) < 1.71, p > .11, all M ≈ 1.6 cm. The variable error of the meeting point as a function of test was also calculated, but there was no significant difference between pre- and posttest, t(12) = 1.78, p = .19, indicating that the meeting point was achieved successfully for all trials and remained relatively constant across pairs and test blocks.

With respect to range of joint angles, Table 1 shows the angle range for all joints averaged across participants as a function of arm and test block. Even though Domkin et al. (2002) found differences in joint range by arm, indicating a handedness effect, this was not the case in the current results. Repeated measures 2 (side: left vs. right) × 2 (test: pre vs. post) ANOVAs for each major joint showed only a significant main effect of test for shoulder range of motion, which was significantly reduced with practice (see Tables 1 and 2). All other main effects and interactions were not significant. all F(1, 8) < 3.58, p > .08, which suggests that participants contributed equally during the actualization of the movement across all trials and sessions.

Table 1.

Range of Motion (in Degrees) for Each Joint Separated by Arm and Test

| Side | Shoulder

|

Elbow

|

Wrist

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Left | Right | Left | Right | Left | Right | |

| Pretest | ||||||

| Mean | 22.63 | 22.50 | 45.95 | 47.86 | 15.36 | 10.31 |

| SD | 3.12 | 5.21 | 14.21 | 9.59 | 11.24 | 6.72 |

| Post-test | ||||||

| Mean | 22.04 | 18.89 | 48.31 | 51.96 | 10.01 | 10.44 |

| SD | 3.53 | 7.66 | 13.57 | 12.48 | 6.78 | 7.10 |

Table 2.

Main Effect Results for the Two-Way Repeated Measures ANOVA on Range of Motion for Each Joint

| Main effect | Shoulder | Elbow | Wrist |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre- vs. Posttest | F1,12 = 5.36 | F1,12 = 1.50 | F1,12 = 3.58 |

| p = .04 | p = .25 | p = .08 | |

| Left vs. Right | F1,12 = .78 | F1,12 = .82 | F1,12 = .81 |

| p = .40 | p = .38 | p = .39 |

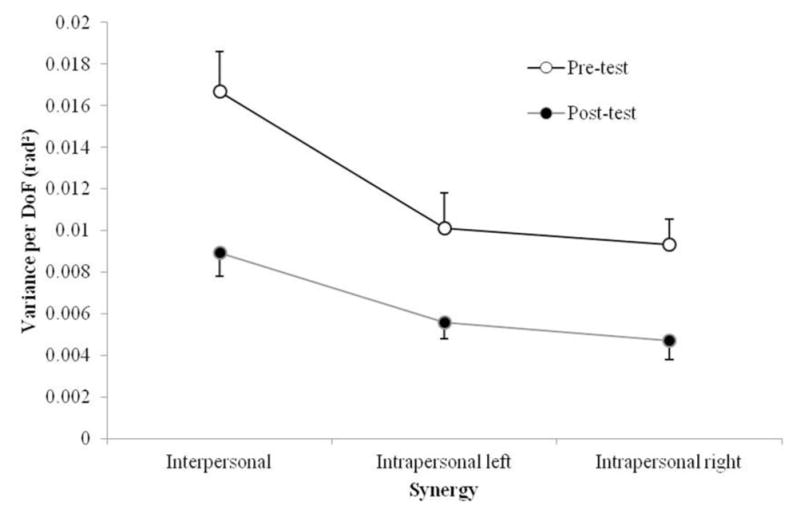

Joint-Angle Variance

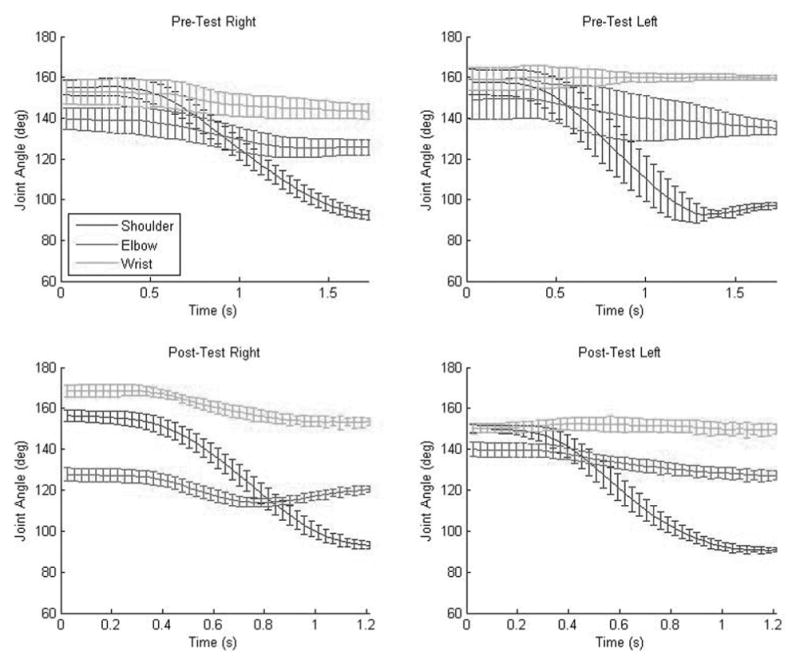

Figure 4 depicts a prototypical example of the mean joint angle trajectory during pre- and posttest trials. The SD, depicted in the error bars, shows a general decrease in overall variance from pre-to posttest. To test whether this decrease was significant, the total variance per DoF (VTOT) averaged across pairs and time bins was analyzed (see Figure 5). Because the interpersonal VTOT is the result of the addition of the value of the two intrapersonal hypotheses, a 2 (side: left vs. right) × 2 (test: pre vs. post) ANOVA was conducted. As expected, this analysis revealed a significant main effect of test, F(1, 12) = 14.83, p < .01, , with VTOT being significantly lower in the posttest (M = 0.005) than the pretest (M = 0.01). That is, participants showed significantly less variability from the pretest to posttest trials (i.e., their performance improved with time). No other significant effects were obtained for the analysis of VTOT (all p > .51).

Figure 4.

Mean joint angle configuration time series of the pre- (top) and posttest (bottom row) blocks by arm in a representative pair. The error bars depict standard deviation. The y-axis depicts the mean time it took to complete the trial.

Figure 5.

Total variance per degree of freedom (VTOT) averaged across the pairs and time bins presented by synergy. Error bars represent standard error of the mean.

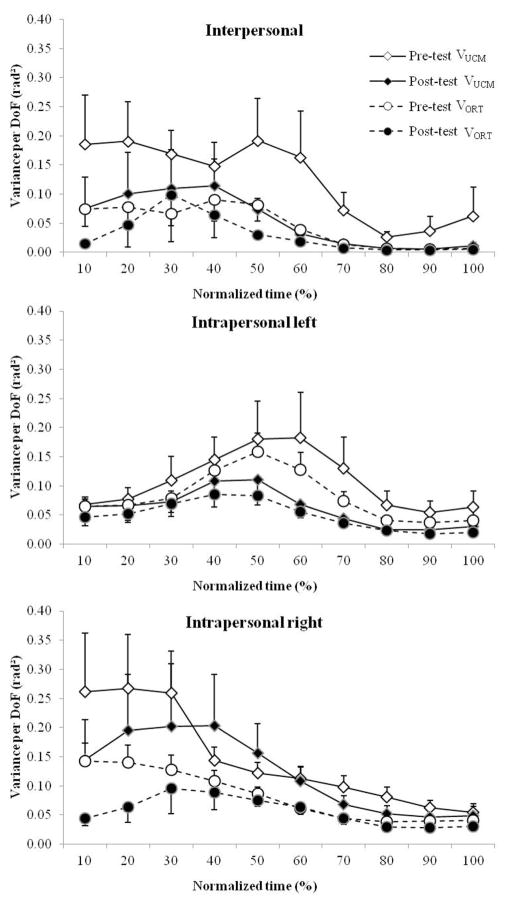

Figure 6 shows the mean VUCM and VORT for both pre- and posttest for each stabilization hypothesis across the 10 normalized time bins. All possible synergy configurations—intrapersonal (left arm and right arm separately) and interpersonal synergy configurations—show higher VUCM than VORT, both for pre- and posttest, indicating that the system at either level can be considered to be synergistically organized. Consistent with the VTOT results reported above, the UCM and ORT variance for all level configurations (i.e., interpersonal, left-arm-intrapersonal, right-arm intrapersonal) also decreased from pre- to posttest.

Figure 6.

VUCM (represented by diamonds) and VORT (represented by circles) averaged across pairs by time bins for the three control configurations (interpersonal at the top, intrapersonal left in the middle, and intrapersonal right at the bottom). The variances are also separated by test (posttest being the filled symbols). Error bars represent standard error of the mean.

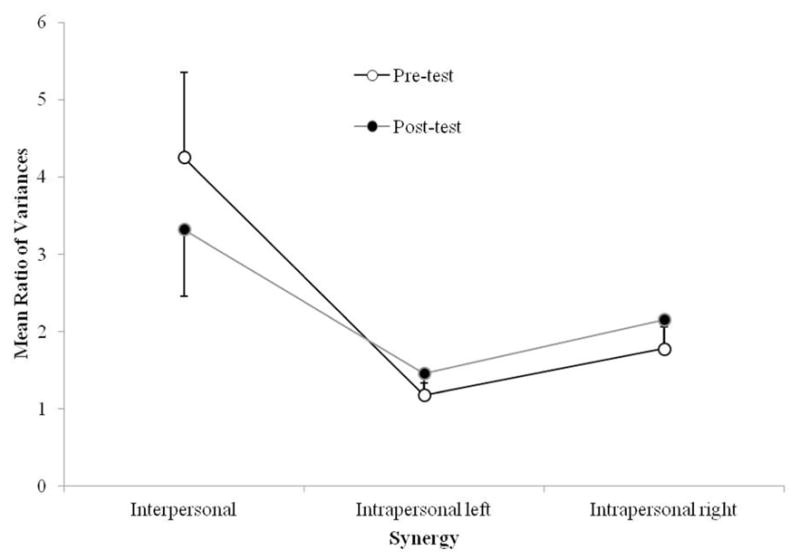

To assess the relative strength of the interpersonal synergy and the two intrapersonal synergies, the ratio of UCM variance over ORT variance (average across pairs and time bins) was calculated for each possible synergy configuration. As can be seen in Figure 7, all the VUCM to VORT ratios obtained were higher than one, indicating that the DoF used for this task were synergistically organized at all levels (interpersonal and intrapersonal). A 2 (test) × 3 (hypothesis: interpersonal, left and right intrapersonal) ANOVA showed a significant main effect of hypothesis, F(2, 24) = 7.13, p = .01, , with LSD post hoc analyses revealing that the interpersonal synergy was significantly stronger (M = 3.79) than the intrapersonal left (M = 1.32; p = .01) and the intrapersonal right (M = 1.97; p = .04) synergies. No other effects were significant (all p > .07).

Figure 7.

Mean ratio of UCM variance to ORT variance by hypothesis and test. Error bars represent standard error of the mean.

Discussion

The aim of the current study was to investigate whether synergistic processes constrain the collective dynamics and mutual responsiveness of coacting individuals completing a discrete joint action task. To test this possibility, a previously investigated intrapersonal bimanual pointing-to-target-task (Domkin et al., 2002) was adapted into a joint action (two-actor) task. The presence and strength of synergistic organization was evaluated using the UCM method at the beginning and at the end of the performance period with respect to three task stabilization hypotheses: Successful task performance was stabilized (H1) across participants (at the interpersonal level) or at the level of (H2) participant one’s arm (intrapersonal left) and (H3) participant two’s arm (intrapersonal right).

Task performance was evaluated by examining the mean amount of total joint angle variance per DoF (VTOT) that was exhibited by participants in the pretest and in the posttest. As expected, task performance improved over the course of the study, as demonstrated by the reduction of VTOT observed from the pre-to the posttest blocks. The significant decrease in mean movement time also pointed to an increase in task performance. Because a certain level of variance is expected and even considered beneficial for motor task completion (Bernstein, 1967; Black et al., 2007a; Turvey, 1990), of greater relevance to the three hypotheses evaluated in this study was the nature of the observed variance (compensated vs. uncompensated).

Analysis of the UCM ratio revealed two key findings. The first was that the behavior was synergistic at both the interpersonal and intrapersonal levels from the pretest and remained synergistic until the posttest. This finding corroborates previous evidence indicating that synergistic organization is typical of human perceptual-motor behavior in general (e.g., Domkin et al., 2002; Furuya & Kinoshita, 2008; Jacquier-Bret et al., 2009; Scholz & Schöner, 1999; Scholz et al., 2000). The second key finding was that the strongest synergistic organization observed in the task was at the interpersonal level, which suggests that the movements of coacting individuals were temporarily constrained and organized to form a single, synergistic, two-person system. (Marsh et al., 2006; Riley et al., 2011) and validates the hypothesis that coactors can spontaneously form a two-person synergistic system in order to carry out a discrete joint action.

Until now, no research had used the UCM method to assess the extent to which the movement of two coacting individuals performing a discrete joint-action task is synergistic—previous research had only demonstrated this with respect to continuous rhythmic coordination tasks (Black et al., 2007a). The findings of the current project thus extend our previous knowledge of interpersonal synergies in several ways (Black et al., 2007a; Ramenzoni, Davis, Riley, Shockley, & Baker, 2011; Riley et al., 2011). First, the current study provides evidence that interpersonal synergistic organization can characterize discrete joint action tasks. Second, the current study shows that joint-action behavior can possess both of the key characteristics of synergistic behavior: RC and DC. Although the use of PCA had previously demonstrated DC across participants (interpersonally) in a suprapostural targeting task (Ramenzoni et al., 2011) it failed to test the presence of RC. The current study showed RC by demonstrating that the majority of the variability present during the motion was within the uncontrolled manifold subspace, where different DoF interacted to bring about successful completion of the task, while stabilizing and reducing the variance that occurred orthogonal to this subspace, which negatively affects the task goal. Additionally, the presence of DC was supported by showing that constraints functionally couple DoF across participants (interpersonal synergy) rather than within participants (both intrapersonal synergies) to form a stronger stabilizing organization. The presence of these two key characteristics in the organization of DoF in a discrete joint motor task therefore provides support for the emergence of interpersonal synergies (cf. Riley et al., 2011).

The finding that the dynamics of individuals performing a joint-action task can become temporarily organized to form a single synergistic two-person system implies that social interactions in general may need to be investigated from a synergistic perspective. Future research should be directed toward identifying the reciprocal and functionally defined couplings that constrain coactors’ DoF. Distinguishing such synergistic processes will likely impact our understanding of other joint-action and social motor coordination phenomena (e.g., interpersonal passing behaviors, team sports), as well as the dynamics of social action and interaction in general. For instance, previous research has shown that simply coordinating one’s movements with another actor can influence rapport, feelings of connection, and feelings of social competence (for a review see Marsh et al., 2009). We might find these effects to be even stronger when studying discrete everyday tasks that require the formation of functional interpersonal synergies. Conversely, studying the influence that feelings of social connection might have on the strength of interpersonal synergies formed between individuals that already know each other during tasks in which they share a mutual goal might further inform the current understanding of social dynamics. Other researchers have also discussed the potential impact that the existence of interpersonal synergies would have in language (Fusaroli et al., 2014) and team sports (Passos et al., 2009; Riley et al., 2011).

Finally, support for interpersonal synergies found in this project could have the potential to radically change our understanding of certain motor and developmental delay disorders. Previous research has demonstrated that people diagnosed with Down’s syndrome, for example, use a different control parameter when it comes to synergistic organization than their control counterparts (Black et al., 2007b) and that Parkinson’s disease patients differ in the amount of variance observed in their motions (Van Emmerik, Hamill, & McDermott, 2005). While these particular findings reflect the effects of motor control deficiencies on intrapersonal synergistic organizations, disorders that affect social motor behavior and functioning are likely to affect the patterning and stability of social motor synergies. Children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) exhibit numerous impairments in social interaction and communication that typically persist throughout their life and impact functioning at home and in the community (Howlin, Goode, Hutton, & Rutter, 2004). Although interacting competently with others relies on cognitive abilities such as making inferences about another’s mental state (Baron-Cohen & Swettenham, 1997), an equally important, yet often overlooked, component of social competence is social motor coordination (Fitzpatrick, Diorio, Richardson, & Schmidt, 2013). Although recent research has revealed differences in the social motor coordination of typically developing children and those with ASD, it remains unclear why this happens. Because social movements emerge reciprocally between two or more actors who constantly accommodate each other, understanding where this relationship breaks down is crucial. Indexing the structure and strength (or lack thereof) of the motor synergies that are formed between parents or siblings and children with ASD might help to better understand these differences. Indeed, the degree of competence in social motor coordination appears to be related to social connectedness in this population. Thus, cataloguing the intra- and interpersonal processes that define ASD to non-ASD interactions could lead to the development of new diagnostic tools (Fitzpatrick et al., 2013; Fitzpatrick, Romero, Amaral, Richardson, & Schmidt, 2013; Isenhower et al., 2012; Marsh et al., 2013).

A limitation of the UCM approach in the current context relates to the discrepancy between the theoretical understanding of how and when synergistic processes operate to organize behavior and the analytical tools available to study these processes. Theoretically, behavioral synergies should exhibit RC and DC both during a continuous bout of task performance, as well as between different trials or instances of a task performance. While for some specific types of movements the UCM method can be employed to measure synergistic processes at a within-trial level (Black et al., 2007a; Scholz et al., 2003), for discrete actions such as the task used in the present study the UCM method only measures synergistic organization between several repetitions of a task and therefore only provides a between-trial measure of synergistic organization. Thus, interpretation of the present results must be qualified with regard to this issue, and the continued development of new methods to identify synergistic organization within discrete movement trajectories should be a priority for future research.

Acknowledgments

This work was part of a master’s thesis conducted by Veronica Romero at the Center for Cognition, Action, and Perception at the University of Cincinnati. The research was also supported, in part, by funding from the National Institutes of Health (awards R01GM105045 and R21MH094659). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Finally, we thank Andrew Beach and Nikita Kuznetsov for help with data collection and data analysis.

Appendix. Computation of the Uncontrolled Manifold Components

This section describes the steps and computations employed to calculate the two components that make up the total variance according to the UCM method: VUCM and VORT. All the calculations are based on those described by Domkin et al. (2002) in their intrapersonal task.

The task variable selected to define the UCM and its subspaces in this study was joint configuration. Joint configuration was first computed for each trial as described in the method section. The mean joint configuration (M) was then calculated across all the trials in each block. Following this, the deviation from M of the joint configuration vector (Ak) was calculated for each trial: k = M − Ak. If all the Aks are clustered around M then the deviation of the task variable can be approximated as: Δrk = J × Δk.. Here J represents the Jacobian matrix used to restate the task variables into coordinates based on the joint angles present in the mean joint configuration. The UCM was defined as the subspace in which changes in the joint configuration resulted in no change to the task variable, and it was linearly approximated by finding the vectors that span this subspace (Domkin et al., 2002).

Δk was then separated into the changes in joint configuration along the two subspaces that make up the task space. The variance per degree-of-freedom of the changes in the joint configuration along or parallel to the UCM was then calculated using the following equation:

| (2) |

(Domkin et al., 2002), where DF is the number of degrees-of-freedom being used to stabilize the movement variance, DV is the dimensions of the task variables, N is the number of trials being considered and ΔkUCM comes from:

| (3) |

Then the variance of the joint configuration that occurred orthogonal to the UCM was calculated:

| (4) |

with ΔkORT simply being the leftover portion of Δk after calculating ΔkUCM.

Interpersonal Stabilization Hypothesis

The following provides details of how the variances were calculated for the interpersonal and the two intrapersonal stabilization hypotheses.

The task variable used to measure success in the interpersonal stabilization hypothesis was the 2D vectorial distance between the pointer and target in the movement plane (rx, ry). Forward kinematics captured the coordinates of the target (Tx and Ty) and the pointer (Px and Py) within the movement plane. This was done through the use of the arm segment lengths (l1: Participant 1’s upper arm, l2: P1’s forearm, l3: distance from P1’s wrist to target, l4: P2’s upper arm, l5: P2’s forearm and l6: distance between P2’s wrist wand the tip of the pointer) and the mean joint configuration given by their joint angles (α1, α2, α3, α4, α5, and α6) and taking into account the coordinates of the shoulders (P1x, P1y, P2x, and P2y) with the following set of equations:

| (5) |

Then, (rx, ry) need to be expressed as joint angles:

| (6) |

Then the derivatives of rx and ry with respect to joint angles are computed with this Jacobian matrix and its elements:

| (7) |

The nullspace of this Jacobian matrix represents the four-dimensional uncontrolled manifold for the task and with the specific version of Equation 2 the VUCM at the interpersonal level is calculated as follows:

| (8) |

Then, VORT (based on Equation 4) is obtained from:

| (9) |

Intrapersonal Stabilization Hypothesis for Participant 1

When considering each arm separately, only three DoF are taken into account and the task variable used is the position of the target only (Tx and Ty). A truncated version of the Jacobian matrix reviewed earlier is used:

| (10) |

The nullspace in this case that represents the UCM is one-dimensional and the ORT is two-dimensional. Therefore, the VUCM and VORT in this case are calculated as the follows:

| (11) |

Intrapersonal Stabilization Hypothesis for Participant 2

Similarly to the calculations of the other intrapersonal stabilization hypothesis, the calculations in this case involved three DoF and a truncated Jacobian matrix:

| (12) |

Again, the resulting UCM nullspace is one-dimensional and the orthogonal nullspace is two-dimensional, therefore VUCM and VORT are calculated as follows:

| (13) |

Footnotes

Trials where sensors were lost due to occlusion problems had to be discarded. This made it impossible to always use the first and last 15 trials of the intended sessions. Furthermore, due to these technological issues the pretest analyzed block for two of the pairs consisted of 11 trials instead of 15.

Prior to conducting the current study, a single-person pilot experiment (N = 5) was conducted using the same procedure and methodology presented here (again, based on Domkin et al., 2002). The data from this pilot study was employed to verify our version (i.e., MATLAB code) of the measures employed by Domkin et al. The results of this single-person pilot study replicated those of Domkin et al.

References

- Anderson ML, Richardson MJ, Chemero A. Eroding the boundaries of cognition: Implications of embodiment. Topics in Cognitive Science. 2012;4:717–730. doi: 10.1111/j.1756-8765.2012.01211.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1756-8765.2012.01211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron-Cohen S, Swettenham J. Theory of mind in autism: Its relationship to executive function and central coherence. In: Cohen DJ, Volkmar FR, editors. Handbook of autism and pervasive developmental disorders. New York, NY: Wiley; 1997. pp. 880–893. [Google Scholar]

- Bekkering H, de Bruijn ERA, Cuijpers RH, Newman-Norlund R, Van Schie HT, Meulenbroek R. Joint action: Neurocognitive mechanisms supporting human interaction. Topics in Cognitive Science. 2009;1:340–352. doi: 10.1111/j.1756-8765.2009.01023.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1756-8765.2009.01023.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein NA. Coordination and regulation of movements. New York, NY: Pergamon Press; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Black DP, Riley MA, McCord CK. Synergies in intra- and interpersonal interlimb rhythmic coordination. Motor Control. 2007a;11:348–373. doi: 10.1123/mcj.11.4.348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black DP, Smith BA, Wu J, Ulrich BD. Uncontrolled manifold analysis of segmental angle variability during walking: Preadolescents with and without Down syndrome. Experimental Brain Research. 2007b;183:511–521. doi: 10.1007/s00221-007-1066-1. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00221-007-1066-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen RG, Sternad D. Variability in motor learning: Relocating, channeling and reducing noise. Experimental Brain Research. 2009;193:69–83. doi: 10.1007/s00221-008-1596-1. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00221-008-1596-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cusumano JP, Cesari P. Body-goal variability mapping in an aiming task. Biological Cybernetics. 2006;94:367–379. doi: 10.1007/s00422-006-0052-1. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00422-006-0052-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domkin D, Laczko J, Jaric S, Johansson H, Latash ML. Structure of joint variability in bimanual pointing tasks. Experimental Brain Research. 2002;143:11–23. doi: 10.1007/s00221-001-0944-1. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00221-001-0944-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick P, Diorio R, Richardson MJ, Schmidt RC. Dynamical methods for evaluating the time-dependent unfolding of social coordination in children with autism. Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience. 2013;7:21. doi: 10.3389/fnint.2013.00021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick P, Romero V, Amaral J, Richardson MJ, Schmidt RC. Is social competence a multi-dimensional construct? Motor and cognitive components in autism. In: Davis T, Passos P, Dicks M, Weast-Knapp J, editors. Studies in perception and action XII: Seventeenth international conference on perception and action. New York, NY: Taylor & Francis Group, LLC; 2013. pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Furuya S, Kinoshita H. Organization of the upper limb movement for piano key-depression differs between expert pianists and novice players. Experimental Brain Research. 2008;185:581–593. doi: 10.1007/s00221-007-1184-9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00221-007-1184-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fusaroli R, Rączaszek-Leonardi J, Tylén K. Dialog as interpersonal synergy. New Ideas in Psychology. 2014;32:147–157. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.newideapsych.2013.03.005. [Google Scholar]

- Ghez C, Favilla M, Ghilardi MF, Gordon J, Bermejo R, Pullman S. Discrete and continuous planning of hand movements and isometric force trajectories. Experimental Brain Research. 1997;115:217–233. doi: 10.1007/pl00005692. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/PL00005692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorniak SL, Zatsiorsky VM, Latash ML. Hierarchies of synergies: An example of two-hand, multi-finger tasks. Experimental Brain Research. 2007;179:167–180. doi: 10.1007/s00221-006-0777-z. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00221-006-0777-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan N, Sternad D. On rhythmic and discrete movements: Reflections, definitions and implications for motor control. Experimental Brain Research. 2007;181:13–30. doi: 10.1007/s00221-007-0899-y. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00221-007-0899-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard IS, Ingram JN, Wolpert DM. Separate representations of dynamics in rhythmic and discrete movements: Evidence from motor learning. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2011;105:1722–1731. doi: 10.1152/jn.00780.2010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1152/jn.00780.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howlin P, Goode S, Hutton J, Rutter M. Adult outcome for children with autism. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2004;45:212–229. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00215.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00215.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huys R, Studenka BE, Rheaume NL, Zelaznik HN, Jirsa VK. Distinct timing mechanisms produce discrete and continuous movements. PLoS Computational Biology. 2008;4:e1000061. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000061. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isenhower RW, Marsh KL, Richardson MJ, Helt M, Schmidt RC, Fein D. Rhythmic bimanual coordination is impaired in young children with autism spectrum disorder. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2012;6:25–31. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2011.08.005. [Google Scholar]

- Jacquier-Bret J, Rezzoug N, Gorce P. Adaptation of joint flexibility during a reach-to-grasp movement. Motor Control. 2009;13:342–361. doi: 10.1123/mcj.13.3.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang N, Shinohara M, Zatsiorsky VM, Latash ML. Learning multi-finger synergies: An uncontrolled manifold analysis. Experimental Brain Research. 2004;157:336–350. doi: 10.1007/s00221-004-1850-0. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00221-004-1850-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelso JAS. Synergies: Atoms of brain and behavior. In: Sternad D, editor. Progress in motor control: A multidisciplinary perspective. Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2009. pp. 83–91. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-77064-2_5. [Google Scholar]

- Kelso JAS, Tuller B, Vatikiotis-Bateson E, Fowler CA. Functionally specific articulatory cooperation following jaw perturbations during speech: Evidence for coordinative structures. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 1984;10:812–832. doi: 10.1037//0096-1523.10.6.812. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0096-1523.10.6.812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kugler PN, Kelso JAS, Turvey MT. On the concept of coordinative structures as dissipative structures: 1. Theoretical lines of convergence. In: Stelmach GE, Requin J, editors. Tutorials in motor behavior. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: North-Holland; 1982. pp. 3–47. [Google Scholar]

- Latash ML. The bliss (not the problem) of motor abundance (not redundancy) Experimental Brain Research. 2012;217:1–5. doi: 10.1007/s00221-012-3000-4. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00221-012-3000-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latash ML, Anson JG. Synergies in health and disease: Relations to adaptive changes in motor coordination. Physical Therapy. 2006;86:1151–1160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latash ML, Scholz JP, Schöner G. Motor control strategies revealed in the structure of motor variability. Exercise and Sport Sciences Reviews. 2002;30:26–31. doi: 10.1097/00003677-200201000-00006. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00003677-200201000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh KL, Isenhower RW, Richardson MJ, Helt M, Verbalis AD, Schmidt RC, Fein D. Autism and social disconnection in interpersonal rocking. Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience. 2013;7:4. doi: 10.3389/fnint.2013.00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh KL, Richardson MJ, Baron RM, Schmidt RC. Contrasting approaches to perceiving and acting with others. Ecological Psychology. 2006;18:1–38. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s15326969eco1801_1. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh KL, Richardson MJ, Schmidt RC. Social connection through joint action and interpersonal coordination. Topics in Cognitive Science. 2009;1:320–339. doi: 10.1111/j.1756-8765.2009.01022.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1756-8765.2009.01022.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller H, Sternad D. Decomposition of variability in the execution of goal-oriented tasks: Three components of skill improvement. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 2004;30:212–233. doi: 10.1037/0096-1523.30.1.212. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0096-1523.30.1.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller H, Sternad D. Motor learning: Changes in the structure of variability in a redundant task. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. 2009;629:439–456. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-77064-2_23. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-77064-2_23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passos P, Araújo D, Davids K, Gouveia L, Serpa S, Milho J, Fonseca S. Interpersonal pattern dynamics and adaptive behavior in multiagent neurobiological systems: Conceptual model and data. Journal of Motor Behavior. 2009;41:445–459. doi: 10.3200/35-08-061. http://dx.doi.org/10.3200/35-08-061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramenzoni VC, Davis TJ, Riley MA, Shockley K, Baker AA. Joint action in a cooperative precision task: Nested processes of intrapersonal and interpersonal coordination. Experimental Brain Research. 2011;211:447–457. doi: 10.1007/s00221-011-2653-8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00221-011-2653-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisman DS, Scholz JP. Aspects of joint coordination are preserved during pointing in persons with post-stroke hemiparesis. Brain: A Journal of Neurology. 2003;126:2510–2527. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg246. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/brain/awg246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson MJ, Marsh KL, Isenhower RW, Goodman JR, Schmidt RC. Rocking together: Dynamics of intentional and unintentional interpersonal coordination. Human Movement Science. 2007;26:867–891. doi: 10.1016/j.humov.2007.07.002. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.humov.2007.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson MJ, Marsh KL, Schmidt RC. Challenging egocentric notions of perceiving, acting and knowing. In: Mesquita B, Barrett LF, Smith ER, editors. The mind in context. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2010. pp. 307–333. [Google Scholar]

- Riley MA, Richardson MJ, Shockley K, Ramenzoni VC. Interpersonal synergies. Frontiers in Psychology. 2011;2:38. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2011.00038. http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2011.00038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronsse R, Sternad D, Lefèvre P. A computational model for rhythmic and discrete movements in uni- and bimanual coordination. Neural Computation. 2009;21:1335–1370. doi: 10.1162/neco.2008.03-08-720. http://dx.doi.org/10.1162/neco.2008.03-08-720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt RC, Bienvenu M, Fitzpatrick PA, Amazeen PG. A comparison of intra- and interpersonal interlimb coordination: Coordination breakdowns and coupling strength. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 1998;24:884–900. doi: 10.1037//0096-1523.24.3.884. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0096-1523.24.3.884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt RC, Richardson MJ. Dynamics of interpersonal coordination. In: Fuchs A, Jirsa VK, editors. Coordination: Neural, behavioral and social dynamics. Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag; 2008. pp. 281–307. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-74479-5_14. [Google Scholar]

- Scholz JP, Danion F, Latash ML, Schöner G. Understanding finger coordination through analysis of the structure of force variability. Biological Cybernetics. 2002;86:29–39. doi: 10.1007/s004220100279. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s004220100279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholz JP, Kang N, Patterson D, Latash ML. Uncontrolled manifold analysis of single trials during multi-finger force production by persons with and without Down syndrome. Experimental Brain Research. 2003;153:45–58. doi: 10.1007/s00221-003-1580-8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00221-003-1580-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholz JP, Schöner G. The uncontrolled manifold concept: Identifying control variables for a functional task. Experimental Brain Research. 1999;126:289–306. doi: 10.1007/s002210050738. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s002210050738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholz JP, Schöner G, Hsu WL, Jeka JJ, Horak F, Martin V. Motor equivalent control of the center of mass in response to support surface perturbations. Experimental Brain Research. 2007;180:163–179. doi: 10.1007/s00221-006-0848-1. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00221-006-0848-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholz JP, Schöner G, Latash ML. Identifying the control structure of multijoint coordination during pistol shooting. Experimental Brain Research. 2000;135:382–404. doi: 10.1007/s002210000540. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s002210000540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sebanz N, Knoblich G. Prediction in joint action: What, when, and where. Topics in Cognitive Science. 2009;1:353–367. doi: 10.1111/j.1756-8765.2009.01024.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1756-8765.2009.01024.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer RM, Verstynen T, Brett M, Ivry R. Cerebellar activation during discrete and not continuous timed movements: An fMRI study. NeuroImage. 2007;36:378–387. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.03.009. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torre K, Balasubramaniam R. Two different processes for sensorimotor synchronization in continuous and discontinuous rhythmic movements. Experimental Brain Research. 2009;199:157–166. doi: 10.1007/s00221-009-1991-2. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00221-009-1991-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng YW, Scholz JP, Schöner G, Hotchkiss L. Effect of accuracy constraint on joint coordination during pointing movements. Experimental Brain Research. 2003;149:276–288. doi: 10.1007/s00221-002-1357-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turvey MT. Coordination. American Psychologist. 1990;45:938–953. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.45.8.938. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.45.8.938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turvey MT. Action and perception at the level of synergies. Human Movement Science. 2007;26:657–697. doi: 10.1016/j.humov.2007.04.002. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.humov.2007.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turvey MT, Fonseca S. Nature of motor control: Perspectives and issues. In: Sternad D, editor. Progress in motor control: A multidisciplinary perspective. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag; 2009. pp. 93–122. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-77064-2_6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Emmerik REA, Hamill J, McDermott WJ. Variability and coordinative function in human gait. Quest. 2005;57:102–123. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00336297.2005.10491845. [Google Scholar]