Abstract

Cyclophilins catalyze cis ↔ trans isomerization of peptidyl–prolyl bonds, influencing protein folding along with a breadth of other biological functions such as signal transduction. Here, we have determined the microscopic rate constants defining the full enzymatic cycle for three human cyclophilins and a more distantly related thermophilic bacterial cyclophilin when catalyzing interconversion of a biologically representative peptide substrate. The cyclophilins studied here exhibit variability in on-enzyme interconversion as well as an up to 2-fold range in rates of substrate binding and release. However, among the human cyclophilins, the microscopic rate constants appear to have been tuned to maintain remarkably similar isomerization rates without a concurrent conservation of apparent binding affinities. While the structures and active site compositions of the human cyclophilins studied here are highly conserved, we find that the enzymes exhibit significant variability in microsecond to millisecond time scale mobility, suggesting a role for the inherent conformational fluctuations that exist within the cyclophilin family as being functionally relevant in regulating substrate interactions. We have additionally modeled the relaxation dispersion profile given by the commonly employed Carr–Purcell–Meiboom–Gill relaxation dispersion (CPMG-RD) experiment when applied to a reversible enzymatic system such as cyclophilin isomerization and identified a significant limitation in the applicability of this approach for monitoring on-enzyme turnover. Specifically, we show both computationally and experimentally that the CPMG-RD experiment is sensitive to noncatalyzed substrate binding and release in reversible systems even at saturating substrate concentrations unless the on-enzyme interconversion rate is much faster than the substrate release rate.

Graphical abstract

The cyclophilins are a ubiquitously expressed family of peptidyl-prolyl isomerases (PPIases) found in all families of life and often existing in multiple isoforms, including 17 in humans.1–3 Among the human cyclophilins, the most abundant and well-characterized is the prototypical Cyclophilin A (CypA). Within the cell, CypA is predominantly localized to the cytoplasm,4 but is also secreted under certain contexts.5 Alternatively, two of the other human cyclophilins, Cyclophilin B (CypB) and Cyclophilin C (CypC), contain signal peptides that localize them to the endoplasmic reticulum,4 while CypB has also been identified extracellularly.6 In addition to their originally identified biological roles as chaperones that aid in folding, cyclophilins also function in signal transduction pathways.7,8 Human cyclophilins have also been implicated in viral infectivity, including HIV and hepatitis,9,10 and can contribute to the progression of multiple inflammatory diseases and cancers.5,11

With the exception of proline, the N-terminal peptide bonds of the other 19 common amino acids exist almost exclusively in the trans population in both unstructured peptides and in the context of proteins. However, X-Pro peptide bonds in free peptides, where X is any other amino acid, adopt the cis conformation ~ 5–40% of the time, depending predominantly on the identity of X. In the context of a folded protein, X-P bonds adopt the cis conformation ~3–10% of the time and are generally locked into a single conformation in the context of a given protein structure.12 The inherent isomerization of the peptidyl–prolyl bond occurs with a rate constant on the order of 10−3 s−1, while cyclophilins and other PPIases increase the rate of isomerization by ~5 orders of magnitude, facilitating proper protein folding and other isomer specific out-comes.13–15

Despite the diversity in cellular localization and biological roles of cyclophilins, few studies have directly compared enzymatic function across multiple members of the family or the degree to which the enzymatic cycles are conserved among them. Multiple human cyclophilins have been previously compared with respect to their binding affinity for the cyclic peptide inhibitor cyclosporine A (CsA) and qualitatively compared with respect to their catalytic activity toward a weakly binding model tetrapeptide substrate.3 However, we sought here to characterize the full enzymatic cycle among multiple cyclophilins as they catalyze a biologically representative peptide substrate. Because prolyl cis ↔ trans interconversion is a reversible process and both isoforms are significantly populated at equilibrium, direct determination of the microscopic rate constants via measurement of substrate depletion or product formation is not possible. Measurement of the unidirectional cis-to-trans interconversion of isomerases can be achieved through a chymotrypsin-coupled assay, although this approach has significant limitations that have been previously outlined, including severe restrictions on the substrate, a low signal-to-noise ratio, and protease degradation of the enzyme.16 Alternatively, NMR line shape analysis provides a powerful means of determining microscopic rate constants on arbitrary substrates at equilibrium. NMR line shapes are exquisitely sensitive to exchange processes that occur on the time scale of chemical shift differences (tens to thousands of Hz); when line shapes are measured at multiple concentrations of an enzyme and substrate and combined with additional functional constraints, the microscopic rate constants defining the catalytic cycle can be determined. Specific to PPIases, line shape analysis has been previously employed to characterize the microscopic rate constants defining CypA catalysis of a non-native modified tetrapeptide17 and for another structurally unrelated PPIase, Pin1, to a biologically relevant peptide substrate.18 Thus, here we have functionally characterized and applied line shape analysis to three human cyclophilins, CypA, CypB, and CypC, as well as to a distant related cyclophilin we have recently characterized that is encoded by the thermophilic bacterium Geobacillus kaustophilus (GeoCyp).

An additional tool that has been applied to study microscopic rate constants in PPIases is the Carr–Purcell–Meiboom–Gill relaxation dispersion (CPMG-RD) experiment. CPMG-RD permits quantitative measurement of chemical exchange phenomena in the ~100–5000 s−1 range. Two-dimensional (2D) spectra are collected while a refocusing pulse is varied between ~50 and 1000 s−1 (νcpmg), allowing, for each νcpmg, calculation of R2 relaxation rates, which comprise an intrinsic relaxation rate (R20) and an exchange-induced relaxation rate (Rex).19,20 The Rex component can be fit to the Carver–Richards equations to extract kinetic (exchange rate, kex), thermodynamic (population occupancies), and structural (chemical shift difference, Δω) information about the exchange.21 Studies of both CypA and Pin1 have measured chemical exchange via CPMG-RD on the enzyme in the presence of near-saturating concentrations of substrate and interpreted the motions as being reflective of on-enzyme turnover.18,22,23 Here, we identify a significant limitation in this approach by providing both computational and experimental evidence indicating that CPMG-RD can be used to measure on-enzyme catalysis only in systems for which substrate release is much slower than on-enzyme interconversion.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Protein Expression and Purification

CypA, GeoCyp, and the substrate peptide were purified as previously described.24 The cyclophilin domain of CypB (residues 39– 216) was purified following a protocol similar to that of CypA. Briefly, for CypB, cells were lysed in lysis buffer [50 mM Tris and 50 mM NaCl (pH 7.0) with 1 mM DTT], purified over an SP Sepharose exchange column, dialyzed back into the lysis buffer, and passed through a Q Sepharose column, followed by size exclusion chromatography in NMR buffer [50 mM Na2HPO4 (pH 6.5) with 1 mM DTT and 1 mM EDTA]. The cyclophilin domain of CypC (residues 25–212) was purified following a protocol identical to that of GeoCyp. Briefly, for CypC, cells were lysed and purified over a nickel affinity column and the six-His tag was removed with thrombin, followed by size exclusion chromatography in NMR buffer [50 mM Na2HPO4 (pH 6.5) with 1 mM DTT and 1 mM EDTA]. All deuterated proteins were refolded following the protocol previously published for CypA and GeoCyp.24 The TA-peptide substrate was synthetically generated by WuXi AppTec, further purified via reverse phase high-performance liquid chromatography, and resuspended in NMR buffer.

NMR Assignments

Backbone assignments of CypA, CypB, and GeoCyp in the unbound forms have been previously published.25–27 For CypC, isotopically 2H-, 13C-, and 15N-labeled protein was purified, followed by collection of 15N HSQC, HNCACB, HN(CO)CA, and HN(COCA)CB experiments at 25 °C on an Agilent DD2 800 MHz spectrometer with a cryogenically cooled probe, allowing near-complete backbone sequential assignments to be determined (BMRB 25341). For CypC, titrations in temperature and with the peptide substrate, along with a 15N NOESY-HSQC experiment, allowed assignment of the amide resonances of CypC at 10 °C in the bound form (BMRB 25339). To determine amide peak assignments in the bound form for CypA (BMRB 25337), CypB (BMRB 25338), and GeoCyp (BMRB 25336) at 10 °C, peaks were followed during titration of the model peptide. Additionally, HNCACB and CBCA(CO)NH experiments were collected on 13C- and 15N-labeled proteins, using a either a Varian 600 MHz spectrometer or an Agilent DD2 800 MHz spectrometer in the presence of saturating concentrations of the model peptide to resolve assignment of any ambiguous peaks. Data were processed using NMRPipe28 and analyzed using CCPNmr.29

Measuring Isomerization Rates

Catalytic isomerization rates were measured as previously published.24 Briefly, ZZ-exchange spectra were collected on 1 mM 15N-labeled peptide with 20 µM enzyme at multiple mixing times. Peak heights were fit to the equations described by Farrow et al.30 All data were collected at 10 °C.

Measuring Apparent Binding Affinity

15N HSQC spectra were collected on 0.5 mM 15N-labeled CypA, CypB, CypC, or GeoCyp in the presence of 0, 0.1, 0.2, 0.5, 1, or 2 mM unlabeled peptide substrate. Titration data were collected at 10 °C on a Varian 900 MHz spectrometer with a cryogenically cooled probe and fit as previously described.24

NMR Relaxation Experiments

15N TROSY CPMG-RD experiments were conducted with 0.5 mM 2H- and 15N-labeled CypA, CypB, CypC, or GeoCyp with 6 mM peptide substrate, 6 mM TA-peptide substrate, or 0.7 mM CsA. Data were collected on both a Varian 900 MHz spectrometer with a cryogenically cooled probe and a Varian 600 MHz spectrometer. Constant time relaxation periods of 60, 30, 40, and 70 ms were used for CypA, CypB, CypC, and GeoCyp, respectively. The R2 relaxation rate was calculated by31

| (1) |

where T is the constant time relaxation period, Iτ is the peak intensity at a given refocusing time τ, and I0 is the peak intensity in the absence of the constant time relaxation period. Exchange parameters were determined by least-squares fitting to the Carver–Richards equations, which describe generalized two-state exchange.21 R1 relaxation was measured using 0.5 mM N-labeled protein with mixing times of 10, 30, 50, 70, 90, and 110 ms. All data were collected at 10 °C.

Line Shape Analysis

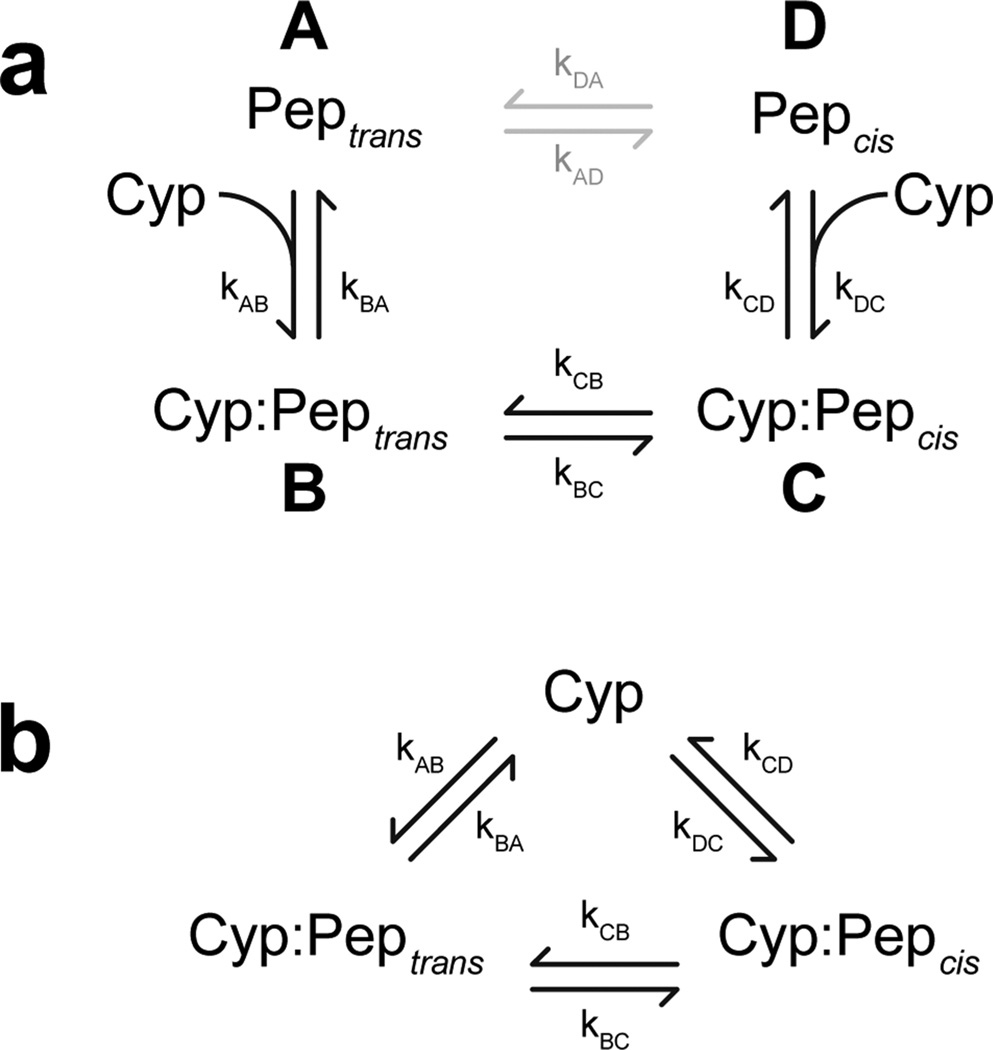

For a given set of microscopic rate constants, the equilibrium concentrations of states A–D (Figure 4a) were determined by solving the set of coupled equations:

| (2) |

using the Levenberg–Marquardt algorithm (LMA) for solving nonlinear least-squares systems, where [Stot] is the total substrate concentration, [Etot] is the total enzyme concentration, and [Efree] is the concentration of unbound enzyme. The evolution of magnetization M for a given residue is described by

| (3a) |

where M is the magnetization of states A–D:

| (3b) |

and K is the evolution matrix:

| (3c) |

where ωA–ωD are the chemical shift of states A –D, respectively, R2A – R2D are the proton R2 relaxation rates of states A–D, respectively, and [Efree] is the concentration of unbound enzyme. J is the scalar coupling constant, given by

| (3d) |

where JNH is the coupling between the amide proton and nitrogen and JHHα is the coupling between the amide proton and the Cα proton. The free induction decay (FID) of the system is given by

| (4a) |

where V is the matrix of eigenvectors of K, λ is the eigenvalues of K, and M0 consists of the equilibrium concentrations of states A–D determined from eq 2:

| (4b) |

FID, given in eq 4a, consists of four decaying exponential vectors describing each of states A–D. The frequency domain spectra were generated by taking the real component of the Fourier transform of the appropriate component (i.e., state A, free cis, or state D, free trans) of the FID, which were then fit to line shapes extracted from 2D 15N HSQC spectra. Spectra were generated for the free cis and free trans states of each residue used for each concentration of protein and peptide. Fits were performed using LMA, allowing each of the six microscopic rate constants and the bound chemical shift values to vary, while fitting to the measured line shapes (recorded at 10 °C on a Varian 900 MHz spectrometer with a cryogenically cooled probe), the apparent KD (KD-app), the observed isomerization rate (kiso), and the chemical shift of each residue when saturated with each cyclophilin. Proton R2 values of the bound form were directly measured on 2H- and 15N-labeled CypA in the free form and found to be ~40 s−1; 32 variation of this value by ±10 s−1 had a minimal effect on the solution for CypA, indicating an insensitivity of the solution to the particular bound R2 value used (Table S1). R2B and R2C were therefore fixed at 40 s−1 for all cyclophilins. At pH 6.5, at which all data were collected, the rate of amide exchange with solvent in an unstructured peptide is ~2 s−1, much lower than rates determined via line shape analysis.33 Additionally, because any exchange with water would be with a noncoherent proton, the net effect of solvent exchange would be a small increase in background R2 (eq 3c, diagonal); because R2 values are determined independently for each isoform of each residue, any variability in solvent accessibility would be accounted for by variability in these calculated R2 values, precluding solvent exchange from impacting rate the rate constants determined here. KD-app was calculated by

| (5) |

The isomerization rate (kiso) given by a single set of microscopic rate constants was determined by generating artificial evolution matrices in which magnetization may only flow from cis to trans or from trans to cis:

| (6a) |

| (6b) |

calculation of eigenvalues from these matrices yields two numbers of large magnitude that describe the rapid equilibration of the bound forms and a number of small magnitude, which describes the flux away from the cis or trans states (i.e., kcis→trans or ktrans→cis). The observed isomerization rate is then given by

| (7) |

Figure 4.

Minimal exchange models of cyclophilin catalysis. (a) Four-state peptide-perspective exchange model. kAD and kDA are many orders of magnitude slower than the other exchange parameters. (b) Three-state enzyme-perspective exchange model.

CPMG-RD Simulations

For each model run, 105 individual atoms were simulated. Atoms were distributed among the three states depicted in Figure 4b as given by the equilibrium concentrations and begun with coherent magnetization. Magnetization was allowed to evolve over a 20 ms simulation time, while stochastically transitioning between states as proscribed by the microscopic rate constants. trans-bound and cis-bound chemical shifts were arbitrarily set to 0.5 and 1 ppm downfield of the free enzyme chemical shift at 21.1 T, respectively, for all simulations. Refocusing pulses were applied with a νcpmg of 50–1000 s−1 by taking the complex conjugate of the magnetization. The absolute value of the sum of the magnetization all atoms after the simulation time yields the peak intensity, and Rex values are calculated as for measured data, using eq 1, for which I0 is set to the sum of magnetizations before evolution.

RESULTS

Functional Characterization of Multiple Members of the Cyclophilin Family

While the enzymatic activities of multiple human cyclophilins toward a short tetrapeptide have been qualitatively compared,3 we sought here to quantitatively compare both binding affinities and catalytic activity toward a biologically representative substrate that binds tighter to multiple members of the family than previously used model peptide substrates. Specifically, we utilized a previously characterized and solution resonance-assigned peptide sub-strate,24 GSFGPDLRAGD, initially derived from a phage display screen by Piotukh et al.,34 which was shown to be representative of multiple putative cyclophilin targets.33 We have previously demonstrated that CypA and GeoCyp both bind to and catalyze isomerization of this peptide.24 Here, we have also characterized the activities of two additional human cyclophilins, CypB and CypC, toward this substrate. The chemical shifts of CypA,25 CypB,27 and GeoCyp26 have been previously published, but not those for CypC. We therefore also determined the backbone chemical shift assignments for CypC (BMRB entry 25341) as described in Materials and Methods.

The GSFGPDLRAGD peptide substrate exists with Pro 5 in both the cis and trans conformations, but titration of the substrate into any of the cyclophilins studied here results in a single set of bound peaks (Figure 1a), indicating that the enzyme–substrate interaction remains in the fast-exchange regime once near-saturating concentrations are reached. Titration of the substrate allows for the determination of an apparent dissociation constant (KD-app), which is influenced by binding to both the cis and trans isoforms. As shown in Table 1, all of the cyclophilins studied here bind to the peptide with affinities in the micromolar range, with an ~2.5-fold range in binding affinity among the human cyclophilins.

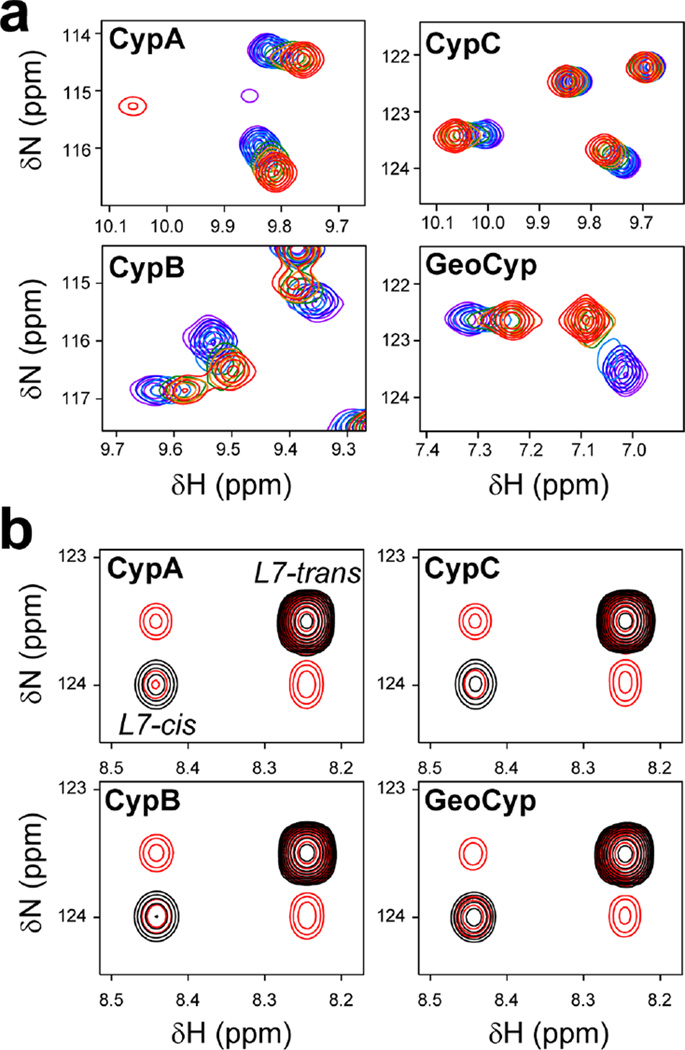

Figure 1.

Functional characterization of cyclophilins. (a) Titrations o the peptide substrate into 15N-labeled cyclophilins. 15N HSQC spectra were collected on 0.5 mM cyclophilin with 0 mM (red), 0.1 mM (orange), 0.2 mM (green), 0.5 mM (cyan), 1 mM (blue), and 2 mM (violet) unlabeled peptide substrate. (b) ZZ-exchange spectra for residue Leu 7, collected with mixing times of 0 ms (black) and 144 ms (red) on 1 mM 15N-labeled peptide with the addition of 20 µM cyclophilin

Table 1.

Apparent Binding Affinities and Observed Isomerization Rates for Multiple Cyclophilins

| enzyme | KD-app (µM) | kiso (s−1) |

|---|---|---|

| CypA | 76 ± 3a,b | 10.0 ± 0.5b |

| CypB | 171 ± 5 | 8.4 ± 0.4 |

| CypC | 146 ± 4 | 9.0 ± 0.5 |

| GeoCyp | 39 ± 2b | 4.7 ± 0.3b |

Errors are in fits to a single experiment.

Previously published.24

Because the peptidyl-prolyl isomerization catalyzed by cyclophilins is a reversible reaction, an isomerization rate of each enzyme was determined by addition of a low, catalytic enzyme concentration (20 µM) to 1 mM 15N-labeled peptide substrate, followed by collection of a ZZ-exchange experiment as previously described.24 Multiple residues exhibit distinct cis and trans amide chemical shifts, including two resides (Asp 6 and Leu 7) for which the cis, trans, and cross-peaks are resolvable (one cross-peak for Asp 6 is overlapped with another residue peak). The time-dependent disappearance of the cis and trans peaks and appearance of cross-peaks can be used to determine an isomerization rate (kiso) between the two free isoforms under the given conditions.30 kiso does not report directly on the catalytic turnover on the enzyme, which will be addressed below, but is dependent on both substrate and enzyme concentrations and is influenced by cis and trans binding affinities as well as turnover on the enzyme. As shown in Table 1 and Figure 1b, each of the cyclophilins studied here catalyzes isomerization of the substrate. Notably, the human cyclophilins catalyze isomerization with nearly identical kiso values, despite the much larger variability in substrate affinity, suggesting that the microscopic rate constants have been evolutionarily “fine-tuned” to maintain similar isomerization rates.

Structural and Dynamic Comparison of Multiple Human Cyclophilins

Previous studies have implicated both structural and dynamic factors in regulating cyclophilin function and in explaining functional differences within the family.3,24,35 Given the variable binding affinities of the three human cyclophilins for the model peptide and the more similar rates of turnover, we sought to determine whether the functional differences were dictated primarily through structure or dynamics. The structures of each of the three human cyclophilins have been previously determined by X-ray crystallography, although only for CypC in the presence of CsA As such, we overlaid the structures of CypA, CypB, and CypC, each determined as bound to CsA As shown in Figure 2a, despite only modest sequence conservation (64 and 54% identical to CypA for CypB and CypC, respectively), the crystallized backbone conformations of the three proteins are nearly identical (backbone rmsds of 1.40 and 1.06 Å with respect to CypA for CypB and CypC, respectively), with the only notable variability occurring in the orientation of the α2–β8 loop. A comparison of the side chains of the highly conserved active site and “gatekeeper” residues likewise reveals nearly identical conformations.3 While these structures were all determined in the presence of CsA, the X-ray structure determined for CypA alone 42 reveals minimal perturbations relative to CypA’s structure when CypA is bound to CsA, suggesting that the protein ground state is not altered significantly upon CsA binding (Figure S1).

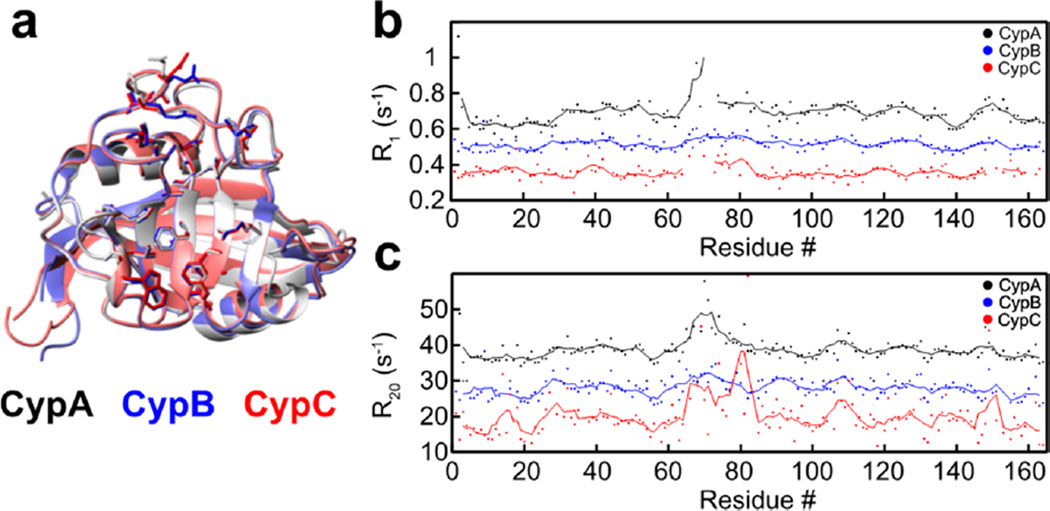

Figure 2.

Highly conserved structure and fast time scale dynamics among CypA, CypB, and CypC, and variable microsecond time scale exchange. (a) Overlaid ribbon diagrams of the previously determined crystal structure of CypA (PDB entry 2RMA, white36), CypB (PDB entry 1CYN, blue37), and CypC (PDB entry 2ESL, red, to be published). Side chains of active site and gatekeeper residues are depicted as sticks. (b) 15N R1 relaxation rates, collected at 900 MHz for 15N-labeled CypA, CypB, and CypC. (c) 15N R20 relaxation rates, estimated by CPMG-RD with a νcpmg of 1000 s−1 collected on 2H15N CypA, CypB, and CypC at 900 MHz. Rates are shifted by up by 15 s−1 (CypB) and 30 s−1 (CypA) to facilitate comparison. For both panels b and c, residue numbers are those for CypA, dots represent individual values, and lines represent a five-residue moving average, with lines plotted only for regions with three or more residues per window.

Given the high degree of structural conservation among these enzymes, we next measured dynamics over multiple time scales, as conformational flexibility may have a role in influencing function. As described previously,24 we have been unable to fit data collected on CypA to the model-free formalism, possibly because of the large number of residues exhibiting microsecond to millisecond motions. We therefore determined 15N longitudinal (R1) relaxation rates for each of the three cyclophilins as reflective of fast time scale motions (Figure 2b). R1 rates report on the rigidity of the backbone and are predominantly reflective of the secondary structure of the protein. Therefore, it is unsurprising that the pattern of R1 rates is largely conserved among the three proteins, with the only major variability being localized to the highly dynamic loop comprising residues 65–73 (all residue numbering is given for CypA).

Slower (microsecond to millisecond) time scale motions have been previously reported as playing a role in the CypA catalytic cycle and can be measured quantitatively by CPMG-RD.22,23,38 However, we found that CypB weakly self-associates on the slow microsecond to millisecond time scale, as demonstrated by a concentration dependence of exchange-induced relaxation (Figure S2) and as we have previously reported for GeoCyp.24 We have instead estimated the Rex-independent component of R2 relaxation (R20) by measurement of CPMG-RD with the highest imparted νcpmg of 1000 s−1. As shown in Figure 2c, the patterns of baseline deviations are largely similar among the three proteins. Notably, variability exists in the magnitude of R20 deviations in both of the two large active site loops (residues 65–80 and 101–110 for CypA), with larger values for CypC and reduced values for CypB, relative to those of CypA. Structural variability in these regions has been previously suggested to impact substrate affinity and specificity,3 and we have shown for GeoCyp that specific side chain differences and dynamic alterations in this region underlie its altered function relative to that of CypA.24

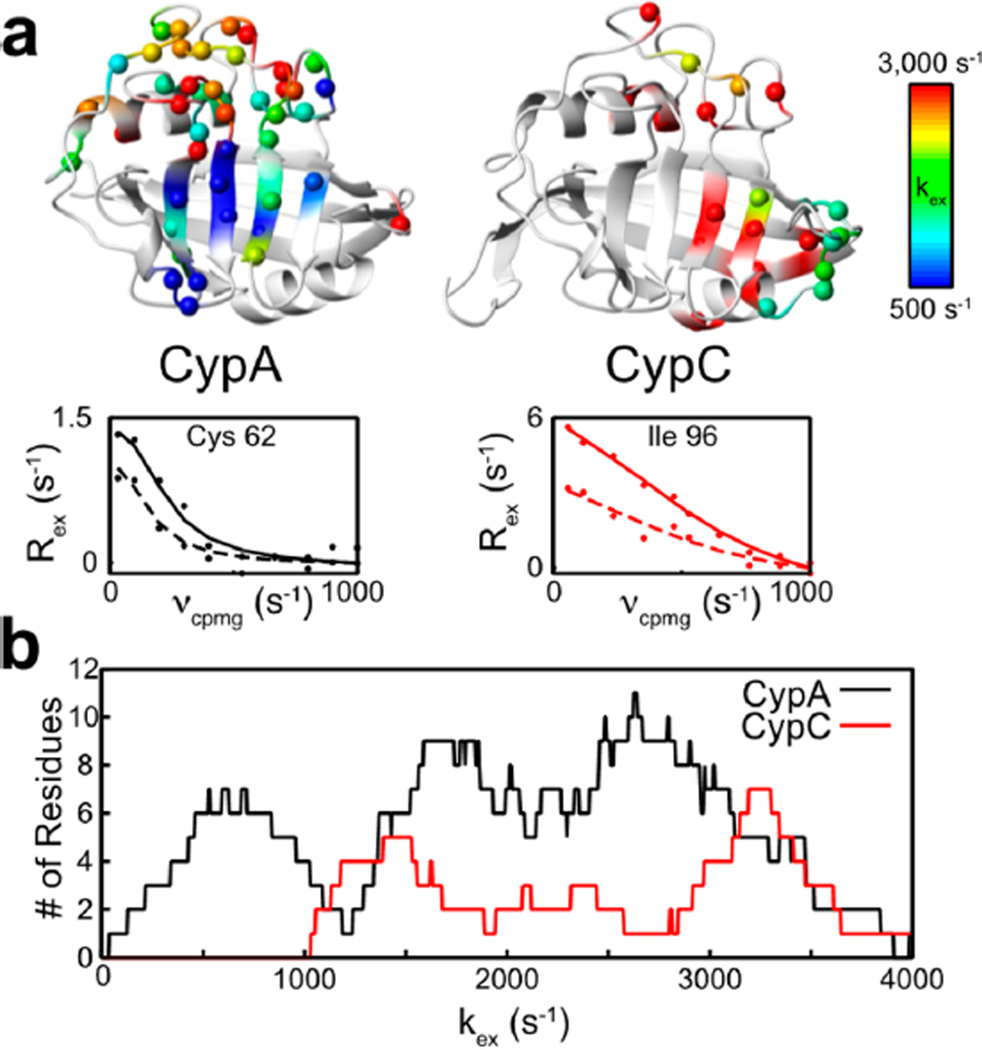

CypA and CypC do not self-associate on the microsecond to millisecond time scale (Figure S2 and ref 38), so we compared microsecond to millisecond time scale motions between them by collecting CPMG-RD data on 2H- and 15N-labeled protein. Both enzymes exhibit mobility in and around the active site on this time scale; however, the localization and rates of motion are altered significantly (Figure 3a,b). Generally, inherent measured rates of motions in CypC are increased relative to CypA and localized predominantly to one side of the protein. In combination with the highly conserved crystal structure and the variability in R20 rates, these data suggest that varied conformational sampling about a highly conserved ground state underlies the observed functional variability among the human cyclophilins studied here.

Figure 3.

Divergent microsecond to millisecond motions in CypA and CypC. (a) kex values measured for CypA and CypC. Data were collected at 600 and 900 MHz and fit individually for each residue to the Carver–Richards equations. Example data (dots) and fits (lines) are shown for homologous residues Cys 62 and Ile 96 at 600 MHz (dashed lines) and 900 MHz (solid lines). Residues are included for which Rex is greater than 0.5 s−1 and the error in kex is both less than 50% of kex and less than 2000 s−1. (b) kex distributions for CypA and CypC. Smoothed histogram showing the microsecond to millisecond rate distribution for CypA (black) and CypC (red). For each kex value, the number of residues is plotted exhibiting a measured rate of ±250 s−1.

Elucidation of the Complete Catalytic Cycle for Multiple Cyclophilins Utilizing Line Shape Analysis

To more thoroughly determine the underlying mechanism of altered functionality among the cyclophilin family, we decided to characterize the enzymatic cycle of each of the human cyclophilins studied here, as well as the distantly related thermophilic cyclophilin, GeoCyp, using line shape analysis. The minimal reaction model of cyclophilin isomerization is depicted in Figure 4a and consists of eight microscopic rate constants. The uncatalyzed interconversion of the peptide substrate (described by kAD and kDA) occurs at a rate many orders of magnitude slower than that of the catalyzed reaction24 and is therefore irrelevant on the NMR time scales utilized herein to experimentally determine the rate constants. We have therefore set this interconversion rate to zero for the remaining calculations. As demonstrated in previous studies utilizing line shape analysis,16,17 the information content of the NMR line shapes alone is generally insufficient to effectively constrain the parameters given in Figure 4a; therefore, as in previous studies, we have included additional, independently determined constraints that are described below and allow for determination of the microscopic rate constants describing cyclophilin catalysis.

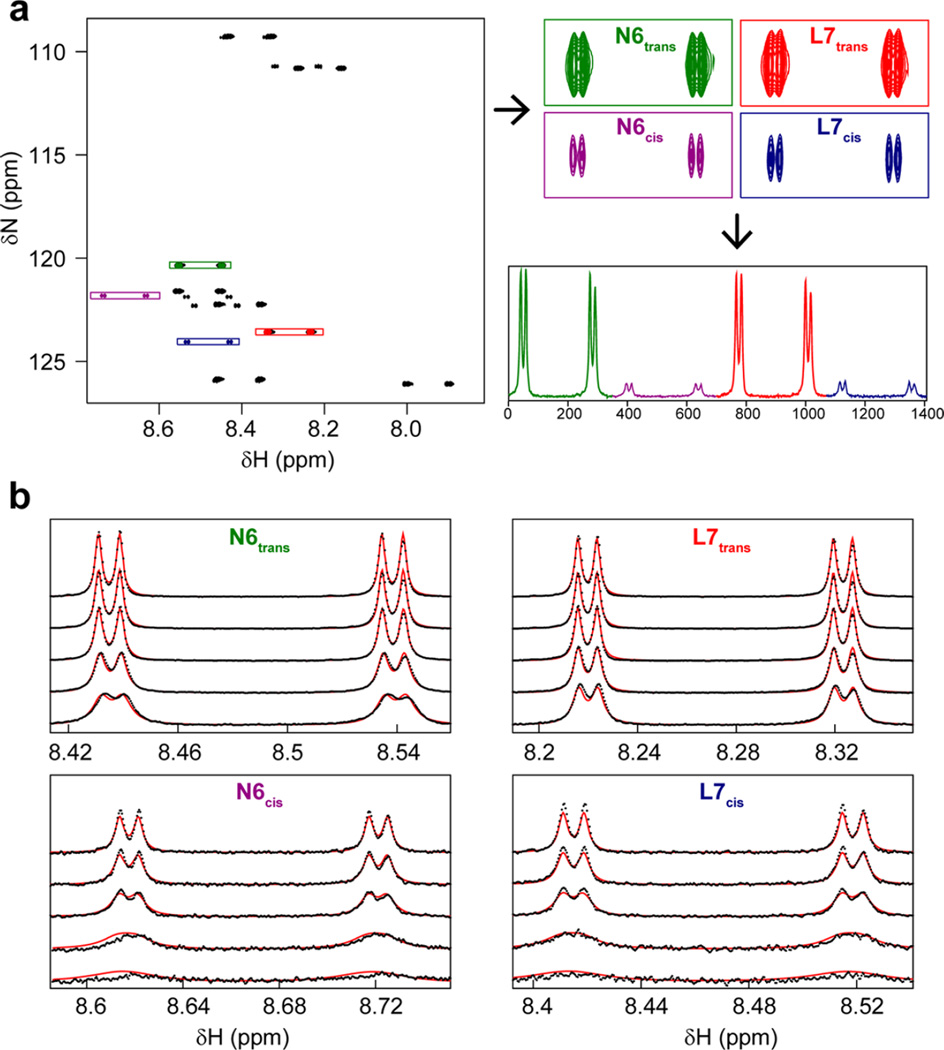

We collected high-resolution 15N HSQC spectra for each of the cyclophilins with multiple 15N-labeled peptide (0.5–1 mM) and unlabeled enzyme (5–100 µM) concentrations. To minimize perturbations to the line shapes imposed by truncation of the free induction decay (FID) data or windowing, we collected the full FID by acquiring data for 2.5 s after completion of the pulse sequence. This long acquisition time precludes application of decoupling during data application, preventing averaging of JNH and JHHα scalar coupling interactions and resulting in four peaks per residue per isoform. As shown in Figure 5a, even with these coupling interactions, for residues Asp 6 and Leu 7, all cis and trans peaks are fully resolved and therefore have been utilized for line shape analysis. Each of the sets of peaks was excised from the 2D spectrum as shown in Figure 5a and summed over the nitrogen dimension to eliminate effects of line broadening in the nitrogen dimension, yielding a series of one-dimensional (1D) traces in proton. Data were also normalized such that the total area under the 1D trace for each cyclophilin/substrate concentration is set to be equal for all conditions for both measured data and calculated line shapes, eliminating effects from variability in experiment-to-experiment signal intensity.

Figure 5.

Extraction and fitting line shape data. (a) High-resolution 15N HQSC spectra were collected on 15N-labeled peptide with variable concentrations of unlabeled cyclophilin without nitrogen decoupling during signal acquisition. Shown here is the peptide in the absence of enzyme. Peaks corresponding to residues Asp 6 and Leu 7 with Pro 5 in the cis and trans conformations were extracted using the windows indicated and summed over nitrogen to yield 1D proton spectra. (b) Line shape fitting for CypA. Fitting was performed as described in Materials and Methods, with data colored black and best-fit line shapes, determined simultaneously for all peptide and enzyme concentrations, colored red. For the sake of clarity, 1D spectra are shown only for 1 mM 15N-labeled peptide with 5, 10, 20, 50, and 100 µM CypA (top to bottom for each residue). Because of the low intensity relative to that of trans peaks, cis peak intensities have been scaled up by a factor of 5 in the bottom graphs for the purpose of visualization.

Data collected on the peptide alone were fit first, permitting determination of transverse relaxation rates for each isoform of each residue, scalar coupling constants, and free peptide chemical shifts to be utilized for fits once enzyme was added. The free variables were then simultaneously fit to the measured line shape data over the multiple enzyme and substrate concentrations as described in Materials and Methods, allowing each of the microscopic rate constants to vary along with the chemical shifts of the bound cis and bound trans forms; additional restraints were imposed to fit the experimentally measured KD-app and kiso described above (Table 1), as well as the averaged proton peak position in the bound form, which was determined by collection of 15N HSQC spectra in the presence of saturating concentrations of each of the cyclophilins. To fully search the parameter space, 200 fits were performed for each cyclophilin while the initial conditions were randomly varied. The best 20 fits, as measured by the coefficient of determination, were then averaged as representative of the best-fit solution and are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Best-Fit Solutions of Cyclophilin Microscopic Rate Constantsa

| CypA | CypB | CypC | GeoCyp | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| kAB (×106 s−1 M−1) | 3.2 ± 0.2 | 2.1 ± 0.2 | 4.2 ± 0.8 | 5.2 ± 1.8 |

| kBA (s−1) | 550 ± 160 | 960 ± 430 | 1620 ± 820 | 720 ± 270 |

| kBC (s−1) | 1660 ± 660 | 550 ± 290 | 370 ± 170 | 2410 ± 1330 |

| kCB (s−1) | 1070 ± 230 | 320 ± 100 | 210 ± 50 | 810 ± 370 |

| kCD (s−1) | 170 ± 40 | 200 ± 70 | 260 ± 100 | 50 ± 10 |

| kDC (×106 s−1 M−1) | 10.0 ± 0.3 | 4.9 ± 0.2 | 7.9 ± 0.3 | 7.0 ± 0.1 |

| KD-cis (µM) | 17 ± 4 | 40 ± 14 | 32 ± 11 | 7 ± 1 |

| KD-trans (µM) | 170 ± 50 | 460 ± 230 | 400 ± 180 | 140 ± 30 |

| bound cis/trans | 1.6 ± 0.8 | 2.1 ± 1.5 | 2.1 ± 1.4 | 3.1 ± 1.0 |

| ωtrans-bound D6 (ppm) | 8.65 ± 0.04 | 8.63 ± 0.07 | 8.63 ± 0.06 | 8.14 ± 0.50 |

| ωcis-bound D6 (ppm) | 8.43 ± 0.03 | 9.76 ± 0.96 | 8.20 ± 1.05 | 8.93 ± 0.04 |

| ωtrans-bound L7 (ppm) | 8.30 ± 0.01 | 8.38 ± 0.05 | 8.36 ± 0.04 | 8.05 ± 0.16 |

| ωcis-bound L7 (ppm) | 8.26 ± 0.01 | 8.25 ± 0.02 | 8.23 ± 0.05 | 8.36 ± 0.07 |

Standard deviation determined from the 20 best fits to the data.

To estimate the extent to which experimental variability may impact determined rate constants, a second, independent data set was also collected for CypA and fit using an identical routine. As shown in Table S2, the fitted rate constants can be reproduced from a second data set, with errors between the data sets comparable to or lower than fitting uncertainties for most parameters in Table 2; we do observe somewhat larger experimental variability for both trans and cis on rates, with differences of 0.6 × 106 and 0.4 × 106 s−1 M−1 between the data sets for kAB and kDC, respectively, suggesting that the true uncertainty in these values may be marginally higher than indicated from the uncertainty in the fitted parameters listed in Table 2.

The catalytic cycles of the cyclophilins fall broadly into two categories: one comprising CypA and GeoCyp, for which on-enzyme interconversion is much faster than substrate release, and a second comprising CypB and CypC, for which on-enzyme interconversion occurs at a rate comparable to the rate of substrate release. For CypA and GeoCyp, the rate constants kBC and kCB, describing cis ↔ trans interconversion on the enzyme, are poorly defined by the fitting routine. For these two enzymes, substrate release is the rate-limiting factor in catalysis, allowing the substrate to stochastically equilibrate on the enzyme before release; under these conditions, the line shape remains largely unaffected by increasing on-enzyme exchange, explaining the poor fits of these parameters. As has previously been reported for CypA catalyzing a tetrapeptide substrate, all of the cyclophilins maintain a much higher binding affinity for the cis isoform,17 leading to an overall slightly higher population of the cis-bound enzyme than of the trans-bound form, even though the unbound substrate exists in ~87% trans.24

A major result here is that, although the structures of these cyclophilins are largely similar, the specific microscopic rate constants vary, as do the measured dynamics on the slower microsecond to millisecond time scale, suggesting a relationship between these rate constants and motions. However, it remains difficult to extract a direct correlation between the microscopic rates constants and rates of motions from the free enzymes considering that only substrate-free CypA and CypC can be monitored by CPMG-RD because of the self-association of CypB and GeoCyp. Moreover, our findings presented above also indicate that the motions are highly localized within substrate-free CypA and CypC (Figure 3b,c), further clouding such direct correlations. However, the microscopic rate constants determined here do provide for direct assessment of the specific microscopic factors underlying observed functional differences between these cyclophilins (Table 1). For example, we recently reported structural and mutagenesis data demonstrating that GeoCyp has a somewhat occluded ground state active site but that upon substrate binding the increased binding affinity and decreased catalytic efficiency of GeoCyp are mediated predominantly through a substrate “clamp” mechanism that holds the peptide in place in the active site.24 From our line shape analysis, it appears that the increased affinity of GeoCyp for the peptide as compared to that of CypA is due predominantly to an increased affinity for the cis isoform, and consistent with our previous study, both the cis on rate and off rate are decreased relative to those of CypA, in accord with our proposed clamp mechanism. Via comparison of CypA to the more weakly binding CypC and CypB, affinities for both the cis and trans isoforms are decreased by similar percentages, effected by both decreased on rates and increased off rates.

Major Limitations in Utilizing CPMG-RD for Measuring On-Enzyme Catalysis in Reversible Systems

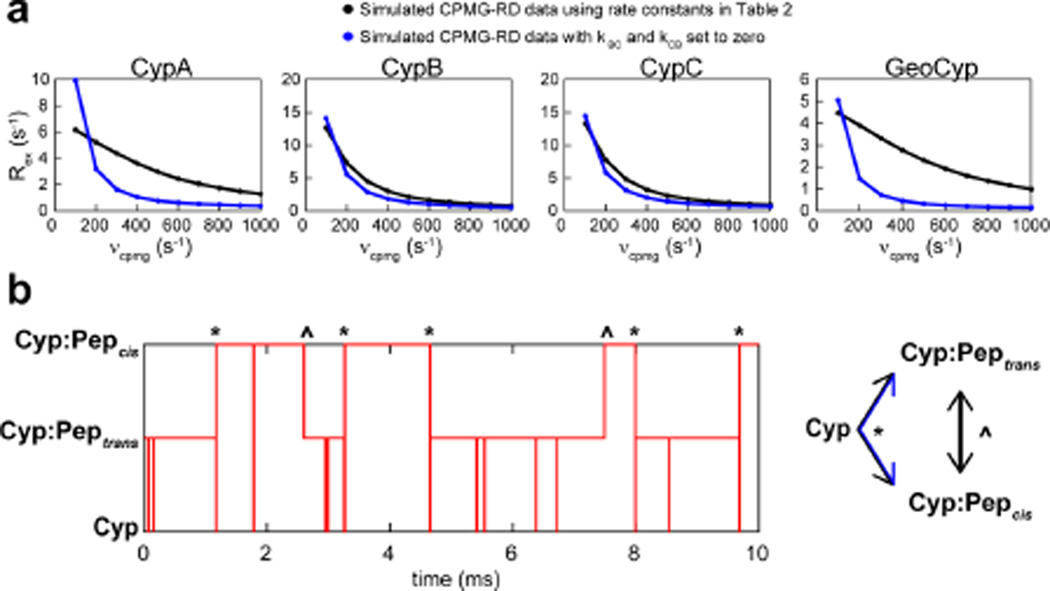

Multiple studies have measured exchange phenomena during catalytic turnover via measurement of CPMG-RD on enzymes in the presence of saturating concentrations of substrate, including for CypA and Pin1, and have concluded that these measured exchange phenomena may be representative of on-enzyme catalysis.18,22,23,38,39 To assess the validity of this approach for our current study, we have modeled the expected CPMG-RD data given by the minimal three-state exchange model from the enzyme perspective (Figure 4b) by simulating the individual magnetizations of 105 atoms as they proceed through the CPMG-RD pulse sequence for each νcpmg with each atom stochastically switching states as described by the microscopic rate constants determined by line shape analysis (Table 2). We have validated this model by applying it to a simple two-state exchange simulation, for which it aligns with the expected results as described by the Carver–Richards equations over a range of input parameters (Figure S3). We have additionally simulated the CPMG-RD data but blocked on-enzyme catalysis from occurring by setting kBC and kCB to zero.

As shown in Figure 6a, even in the absence of on-enzyme catalytic turnover (blue lines), and at arbitrarily high substrate concentrations (see Figure S4), significant exchange-induced relaxation is expected for all four cyclophilins using the microscopic rate constants determined by line shape analysis. The origin of this exchange in the absence of catalysis lies in interconversion, from the enzyme perspective, between the cis-bound form and trans-bound form via the free enzyme intermediate, by binding to different substrate molecules in opposite conformations (Figure 6b, blue arrows). The enzyme-perspective free ↔ trans (where kfree↔trans = [A]kAB + kBA) and free ↔ cis (where kfree↔cis = kCD + [D]kDC) interconversions each occur on time scales much faster than the CPMG-RD regime at high substrate concentrations, such as the peptide concentration of 6 mM utilized for all CPMG-RD experiments here, and therefore do not directly influence Rex (see Figures S2 and S4); however, the effective cis↔trans interconversion via the free enzyme intermediate lies squarely in the CPMG regime for these parameters. In other words, at high substrate concentrations, a residue with identical cis-bound and trans-bound chemical shifts and a different free chemical shift would register no chemical exchange via CPMG-RD, while a residue with different cis-bound and trans-bound chemical shifts would register chemical exchange even in the absence of isomerization. The apparent exchange rate (kex-app) that would be measured by any probe monitoring cis↔trans exchange is given by

| (8a) |

with

| (8b) |

| (8c) |

where [A] and [D] are the equilibrium concentrations of unbound trans and cis peptide, respectively. This phenomenon is illustrated in Figure 6b by following the state occupancy of a single simulated atom over a 10 ms simulation. While virtually no time is spent in the free state, substrate release permits noncatalyzed exchange of the cis and trans isoforms on the enzyme (Figure 6b, kex-uncatalyzed, “*”) in addition to catalyzed exchange (Figure 6b, kex-catalyzed, “^”). Given that kex.app is dependent all six rate constants (eq 8), the conditions under which CPMG-RD measurements may be indicative of on-enzyme catalysis cannot be readily generalized to a given system without consideration of the full catalytic cycle. However, to estimate the range over which kex-uncatalyzed may significantly impact CPMG-RD measurements in CypA, we simulated data over a range of kex-catalyzed and KD-app values, keeping the remaining rate constants unchanged from those listed in Table 2 (Figure S5). In general, only in the limiting case for which substrate release (i.e., kBA and kCD) is much slower than on-enzyme catalysis can measured CPMG-RD data possibly be predominantly representative of on-enzyme catalysis. For all other cases involving reversible enzymatic catalysis, measured CPMG-RD data are instead influenced by both on-enzyme interconversion and interconversion via the free enzyme intermediate. These two components cannot be readily parsed from the CPMG-RD data alone but can be separated by utilizing line shape analysis as we have described above.

Figure 6.

CPMG-RD can report on uncatalyzed exchange in reversible enzymatic systems. (a) Using the rate constants determined from line shape analysis (Table 2), CPMG-RD data were simulated from the cyclophilin perspective with (black) or without (blue) on-enzyme catalysis, with in silico concentrations of 1 mM cyclophilin and 10 mM peptide. For all cyclophilins, significant exchange persists even in the absence of catalysis. (b) State map of a single simulated atom over a 10 ms simulation, using the microscopic rate constants determined for CypC. Vertical lines represent transitions between states, while horizontal lines represent time spent in a single state. Transitions between Cyp:Peptrans and Cyp:Pepcis occur both through on-enzyme catalysis (^) and through the free enzyme intermediate (*).

kex-app, kex-catalyzed, and kex-uncatalyzed values for each of the cyclophilins studied here, calculated from the microscopic rate constants in Table 2, are listed in Table 3. kex-app is minimally impacted by uncatalyzed interconversion for CypA or Geo, while it is significantly impacted for both CypC and CypB. To compare the measured CPMG-RD exchange rates to the kex-app values predicted by the microscopic rate constants, CPMG-RD experiments were conducted at multiple magnetic field strengths on 2H- and 15N-labeled versions of each of the cyclophilins in the presence of saturating concentrations of the peptide substrate, and data were fit to the Carver–Richards equations. To ensure that interconversion with the free protein (i.e., free ↔ trans and free ↔ cis) would not directly impact measured exchange by CPMG-RD, data were collected at multiple substrate concentrations (Figure S2). Additionally, the weak self-association of CypB and GeoCyp is blocked upon addition of saturating concentrations of substrate (Figure S2), therefore allowing CPMG-RD data to be compared among all four cyclophilins. While all measured motions in the enzyme are not necessarily indicative of trans ↔ cis interconversion, measured motions detected at the conserved catalytic arginine (Arg 55 in CypA) are compared to the expected kex-app values in Table 3. With the exception of CypA, the expected kex-app values are similar to those experimentally observed at this reside. The overestimation of kex-app for CypA may be due to the poorly defined kBC and kCB values that define kex-catalyzed because of their minimal impact on line shapes (Table 2).

Table 3.

Calculated trans ↔ cis Exchange Rates for Each Cyclophilin and Chemical Exchange Rates Measured by CPMG-RD at the Catalytic Arginine

| enzyme | kex-catalyzed (s−1) | kex-uncatalyzed (s−1) | kex-app (s−1) | kex-Arg |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CypA | 2740 ± 700a | 290 ± 30 | 3030 ± 700 | 1600 ± 210b |

| CypB | 880 ± 210 | 390 ± 80 | 1270 ± 280 | 980 ± 330 |

| CypC | 580 ± 130 | 560 ± 120 | 1130 ± 240 | 1080 ± 420 |

| GeoCyp | 3200 ± 1600 | 160 ± 30 | 3380 ± 1610 | 4010 ± 2000 |

Standard deviation determined from the 20 best fits to the data.

Errors in fitting the Carver-Richards equations.

To experimentally demonstrate the existence of measurable CPMG-RD exchange under saturating conditions in the absence of catalysis, we utilized a previously described substrate for which the G-P peptide bond in the peptide is replaced by a thioamide bond (TA-peptide). This substrate binds only ~50% weaker than the standard GSFGPDLRAGD peptide but is not isomerized by CypA.40 We collected 15N CPMG-RD data on 2H- and 15N-labeled CypA in the presence of saturating concentrations of either the peptide substrate or the uncatalyzed TA-peptide (see Figure S2 for validation of saturation by the TA-peptide). As shown in panels a and b of Figure 7, chemical exchange can be measured throughout most of the active site for both substrates, albeit at a significantly slower rate for the modified peptide (~1500 s−1 for the peptide vs ~300 s−1 for the TA-peptide). This lowered exchange rate is expected and indeed recapitulated in our simulation (Figure 6a), as the interconversion is proceeding through only the free enzyme intermediate as opposed to a combined exchange through both the free enzyme intermediate and on-enzyme exchange. To demonstrate that this exchange is reporting on binding and release of the substrate, we also collected 15N CPMG-RD data on 2H- and 15N-labeled CypA in the presence of the inhibitor CsA, which binds with an affinity of 7 nM.3 The exchange observed for CypA in the presence of both the catalyzed peptide and uncatalyzed TA-peptide that both exist in two unbound isoforms is quenched by CsA throughout most of the active site, as expected because of both the lack of cis and trans isoforms of CsA and the slow off rate associated with binding at an affinity of 7 nM (Figure 7a,b).

Figure 7.

Measured CPMG-RD data on 2H- and 15N-labeled CypA when it is saturated with catalyzable and uncatalyzable substrates. (a) 15N CPMG-RD data collected at 900 MHz (dots) and best-fit curves (lines) using the Carver–Richards equations, fit to data collected at 600 and 900 MHz for representative residues in 2H- and 15N-labeled CypA with saturating concentrations of the peptide substrate (black), the TA-peptide (blue), or CsA (red). (b) Measured exchange rates (kex) mapped onto the CypA structure in the presence of saturating concentrations of peptide, TA-peptide, or CsA. Data for each residue were individually fit. Residues are included for which Rex is greater than 0.5 s−1 and the error in kex is both less than 50% of kex and less than 2000 s−1. (c) CPMG-RD traces of representative residues in CypA that are not directly reporting on exchange between Cyp:Peptrans and Cyp:Pepcis.

Segmental Dynamics in CypA in the Bound Form

Despite the limitations in utilizing CPMG-RD to directly measure on-enzyme catalytic turnover in cyclophilins due to the contribution of uncatalyzed exchange, CPMG-RD still allows us to identify the existence of localized dynamics in CypA in the presence of uncatalyzable binding partners. We mapped kex values measured on 2H- and 15N-labeled CypA in the presence of saturating conditions of the peptide, the uncatalyzed TA-peptide, and CsA onto the structure of CypA. As described above and plotted in panels a and b of Figure 7, for much of the active site, dynamics are completely quenched for CypA:CsA and slowed dramatically in CypA:TA-peptide as compared to those of the CypA:peptide complex. Within one region of the active site, however, comprising a loop of residues ~65–78 and adjacent residues ~108–110, significant exchange is observed for CypA:CsA and much faster motions (~2000 s−1) are observed for CypA:TA-peptide (Figure 7b). The measured chemical exchanges for residues in this region are not fully independent of substrate binding, as Rex is altered significantly among the three binding partners (Figure 7c); nonetheless, these residues are not reporting directly on trans ↔ cis interconversion and demonstrate the existence of localized, yet coupled, microsecond to millisecond conformational dynamics in CypA when bound to substrate.

DISCUSSION

We have functionally characterized the interactions of multiple cyclophilins with a biologically representative peptide substrate and found that the catalytic efficiency is well-conserved among human family members, while the binding affinities differ more substantially. Because we have recently characterized a distantly related cyclophilin isoform, GeoCyp, and found that its catalytic efficiency and apparent dissociation constant are lower than those of its human counterparts, here we sought to determine the underlying differences between catalysis among the cyclophilins. To this end, here we compared previously determined structures, monitored dynamics on various time scales, and determined the complete catalytic cycle of three human paralogues (CypA, CypB, and CypC) and a thermophilic homologue, GeoCyp. The high degree of structural similarity among human cyclophilins along with the variability in microsecond to millisecond dynamics suggests that conformational flexibility plays a role in fine-tuning the catalytic cycle.

The application of line shape analysis in combination with fitting functional data of binding and catalysis yields well-defined parameters for the full catalytic cycle of multiple cyclophilins. Particularly notable is the degree to which substrate on rates vary between cyclophilins. The one previous study17 utilizing line shape analysis as applied to CypA reported substrate on rates of 18 × 106 and 27 × 106 s−1 M−1 for the trans and cis isoforms, respectively, near diffusion-limited, and many times the largest rates reported here. That study utilized a modified tetrapeptide, which may account for the difference in measured values; conformational selection has been suggested to play a major role in the cyclophilin binding mechanism, and the larger peptide utilized here may require a more restrictive, and thus less frequently sampled, conformation for binding. CypA has been shown to exhibit a relatively low substrate specificity, implicating the high degree of active site conformational mobility in sampling a wide range of states competent to interact with diverse substrates.3,41 The variability in substrate on rates between cyclophilins may, then, be reflective of subtly altered conformational landscapes whereby each cyclophilin has adapted its particular landscape to the suite of substrates with which it is likely to interact. Indeed, variability in substrate binding energetics between cyclophilins has already been demonstrated and likely plays a role in modulating substrate release.3 Nonetheless, the full catalytic cycle appears to have been evolutionarily constrained, yielding nearly identical catalytic efficiencies for each of the human cyclophilins.

We have also identified significant limitations in applying CPMG-RD experiments to monitor on-enzyme catalytic activity in reversible enzymatic systems. Specifically, unless the enzyme-perspective substrate exchange via the free enzyme intermediate [kex-uncatalyzed (Figure 6)] is much slower than on-enzyme exchange (kex-catalyzed), the effective cis ↔ trans exchange (kex-app) does not report solely on kex-catalyzed. Of previous studies analyzing substrate-saturated CypA dynamics, two utilized a weakly binding (KD-app of ~1 mM, koff of ~104 s−1) tetrapeptide,22,38 while another used a domain of the HIV capsid protein,23 which binds much more tightly (KD-app of 16 µM, koff of ~45 s−1). In the former cases, the high value of kex-uncatalyzed renders kex- app too fast to be observed via CPMG-RD such that any observed dynamics by CPMG-RD cannot be indicative of cis ↔ trans interconversion; notably, a majority of the residues with measured exchange under substrate-bound conditions in these studies colocalize with dynamics identified in panels b and c of Figure 7 as not reporting directly on cis ↔ trans interconversion. Alternatively, because of the slow off rates, CPMG-RD measured dynamics during catalysis of the HIV capsid protein are potentially indicative of on-enzyme exchange as reported. A previous study that analyzed Pin1 dynamics during catalysis also utilized a weakly binding substrate (KD-app of ~0.8 mM), likewise precluding direct measurement of kex-catalyzed by CPMG-RD.18 Thus, great care must be taken in interpreting CPMG-RD data collected on any multispecies systems with schemes more complex than a simple two-state binding model.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

NMR experiments were conducted at The Rocky Mountain 900 Facility (NIH Grant GM68928) and The High Magnetic Field Laboratory (NHMFL) that is supported by Cooperative Agreement DMR 0654118 between the National Science Foundation and the State of Florida.

Funding

M.J.H. is supported by the Earleen and Victor Bolie Scholarship Fund and National Institutes of Health (NIH) Applications 5T32GM008730-13 and 1F31CA183206-01A1. E.Z.E. is supported by NIH Application 1RO1GM107262-01A1.

ABBREVIATIONS

- CPMG-RD

Carr-Purcell-Meiboom-Gill relaxation dispersion

- NMR

nuclear magnetic resonance

- CypA

human Cyclophilin A

- CypB

human Cyclophilin B

- CypC

human Cyclophilin C

- GeoCyp

cyclophilin from G. kaustophilus

- CsA

cyclosporine A

- TA-peptide

thioamide-modified peptide

- HSQC

heteronuclear single-quantum coherence

- rmsd

root-mean-square deviation

- KD-app

apparent dissociation constant

- kex-app

apparent exchange rate

- kiso

observed isomerization rate

- LMA

Levenberg–Marquardt algorithm

- PDB

Protein Data Bank

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acs.bio-chem.5b00746.

Overlay of crystal structures free CypA and CypA bound to CsA; self-association of CypB but not CypC on the millisecond time scale; saturation of CypA, CypB, CypB, and GeoCyp with the peptide substrate; saturation of CypA with the TA-peptide; validation of the CPMG-RD model by comparison to the Carver-Richards analytical solution for two-state exchange; simulated Rex values for a range of substrate concentrations; simulated CPMG-RD data for the saturated CypA:peptide complex over a range of artificial kex-catalyzed and KD-app values; microscopic rate constants determined with different values of R2-bound; and microscopic rate constants determined for an independently collected CypA data set (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gothel SF, Marahiel MA. Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerases, a superfamily of ubiquitous folding catalysts. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 1999;55:423–436. doi: 10.1007/s000180050299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bang H, Pecht A, Raddatz G, Scior T, Solbach W, Brune K, Pahl A. Prolyl isomerases in a minimal cell. Catalysis of protein folding by trigger factor from Mycoplasma genitalium. Eur. J. Biochem. 2000;267:3270–3280. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01355.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davis TL, Walker JR, Campagna-Slater V, Finerty PJ, Paramanathan R, Bernstein G, MacKenzie F, Tempel W, Ouyang H, Lee WH, Eisenmesser EZ, Dhe-Paganon S. Structural and biochemical characterization of the human cyclophilin family of peptidyl-prolyl isomerases. PLoS Biol. 2010;8:e1000439. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Galat A. Peptidylproline cis-trans-isomerases: immuno-philins. Eur. J. Biochem. 1993;216:689–707. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb18189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Billich A, Winkler G, Aschauer H, Rot A, Peichl P. Presence of cyclophilin A in synovial fluids of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J. Exp. Med. 1997;185:975–980. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.5.975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Allain F, Boutillon C, Mariller C, Spik G. Selective assay for CyPA and CyPB in human blood using highly specific anti-peptide antibodies. J. Immunol. Methods. 1995;178:113–120. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(94)00249-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rycyzyn MA, Reilly SC, O’Malley K, Clevenger CV. Role of cyclophilin B in prolactin signal transduction and nuclear retrotranslocation. Mol. Endocrinol. 2000;14:1175–1186. doi: 10.1210/mend.14.8.0508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Satoh K, Shimokawa H, Berk BC. Cyclophilin A: promising new target in cardiovascular therapy. Circ. J. 2010;74:2249–2256. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-10-0904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thali M, Bukovsky A, Kondo E, Rosenwirth B, Walsh CT, Sodroski J, Gottlinger HG. Functional association of cyclophilin A with HIV-1 virions. Nature. 1994;372:363–365. doi: 10.1038/372363a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Watashi K, Ishii N, Hijikata M, Inoue D, Murata T, Miyanari Y, Shimotohno K. Cyclophilin B is a functional regulator of hepatitis C virus RNA polymerase. Mol. Cell. 2005;19:111–122. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee J, Kim SS. An overview of cyclophilins in human cancers. J. Int. Med. Res. 2010;38:1561–1574. doi: 10.1177/147323001003800501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reimer U, Scherer G, Drewello M, Kruber S, Schutkowski M, Fischer G. Side-chain effects on peptidyl-prolyl cis/ trans isomerisation. J. Mol. Biol. 1998;279:449–460. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fischer G, Bang H, Mech C. [Determination of enzymatic catalysis for the cis-trans-isomerization of peptide binding in proline-containing peptides] Biomedica biochimica acta. 1984;43:1101–1111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kern G, Kern D, Schmid FX, Fischer G. A kinetic analysis of the folding of human carbonic anhydrase II and its catalysis by cyclophilin. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:740–745. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.2.740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferreira PA, Orry A. From Drosophila to Humans: Reflections on the Roles of the Prolyl Isomerases and Chaperones, Cyclophilins, in Cell Function and Disease. J. Neurogenet. 2012;26:132. doi: 10.3109/01677063.2011.647143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Greenwood AI, Rogals MJ, De S, Lu KP, Kovrigin EL, Nicholson LK. Complete determination of the Pin1 catalytic domain thermodynamic cycle by NMR lineshape analysis. J. Biomol. NMR. 2011;51:21–34. doi: 10.1007/s10858-011-9538-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kern D, Kern G, Scherer G, Fischer G, Drakenberg T. Kinetic analysis of cyclophilin-catalyzed prolyl cis/trans isomerization by dynamic NMR spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 1995;34:13594–13602. doi: 10.1021/bi00041a039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Labeikovsky W, Eisenmesser EZ, Bosco DA, Kern D. Structure and dynamics of pin1 during catalysis by NMR. J. Mol. Biol. 2007;367:1370–1381. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.01.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Palmer AG, 3rd, Kroenke CD, Loria JP. Nuclear magnetic resonance methods for quantifying microsecond-to-millisecond motions in biological macromolecules. Methods Enzymol. 2001;339:204–238. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(01)39315-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Loria JP, Berlow RB, Watt ED. Characterization of enzyme motions by solution NMR relaxation dispersion. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008;41:214–221. doi: 10.1021/ar700132n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carver JP, Richards RE. A general two-site solution for the chemical exchange produced dependence of T2 upon the carr-Purcell pulse separation. J. Magn. Reson. 1972;6:89–105. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eisenmesser EZ, Bosco DA, Akke M, Kern D. Enzyme dynamics during catalysis. Science. 2002;295:1520–1523. doi: 10.1126/science.1066176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bosco DA, Eisenmesser EZ, Clarkson MW, Wolf-Watz M, Labeikovsky W, Millet O, Kern D. Dissecting the microscopic steps of the cyclophilin A enzymatic cycle on the biological HIV-1 capsid substrate by NMR. J. Mol. Biol. 2010;403:723–738. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holliday MJ, Camilloni C, Armstrong GS, Isern NG, Zhang F, Vendruscolo M, Eisenmesser EZ. Structure and Dynamics of GeoCyp: A Thermophilic Cyclophilin with a Novel Substrate Binding Mechanism That Functions Efficiently at Low Temperatures. Biochemistry. 2015;54:3207–3217. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.5b00263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ottiger M, Zerbe O, Guntert P, Wuthrich K. The NMR solution conformation of unligated human cyclophilin A. J. Mol. Biol. 1997;272:64–81. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holliday MJ, Zhang F, Isern NG, Armstrong GS, Eisenmesser EZ. 1H, 13C, and 15N backbone and side chain resonance assignments of thermophilic Geobacillus kaustophilus cyclophilin-A. Biomol. NMR Assignments. 2014;8:23–27. doi: 10.1007/s12104-012-9445-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hanoulle X, Melchior A, Sibille N, Parent B, Denys A, Wieruszeski JM, Horvath D, Allain F, Lippens G, Landrieu I. Structural and functional characterization of the interaction between cyclophilin B and a heparin-derived oligosaccharide. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:34148–34158. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706353200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Delaglio F, Grzesiek S, Vuister GW, Zhu G, Pfeifer J, Bax A. NMRPipe: a multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J. Biomol. NMR. 1995;6:277–293. doi: 10.1007/BF00197809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vranken WF, Boucher W, Stevens TJ, Fogh RH, Pajon A, Llinas M, Ulrich EL, Markley JL, Ionides J, Laue ED. The CCPN data model for NMR spectroscopy: development of a software pipeline. Proteins: Struct., Funct., Genet. 2005;59:687–696. doi: 10.1002/prot.20449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Farrow NA, Zhang O, Forman-Kay JD, Kay LE. A heteronuclear correlation experiment for simultaneous determination of 15N longitudinal decay and chemical exchange rates of systems in slow equilibrium. J. Biomol. NMR. 1994;4:727–734. doi: 10.1007/BF00404280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Farrow NA, Muhandiram R, Singer AU, Pascal SM, Kay CM, Gish G, Shoelson SE, Pawson T, Forman-Kay JD, Kay LE. Backbone dynamics of a free and phosphopeptide-complexed Src homology 2 domain studied by 15N NMR relaxation. Biochemistry. 1994;33:5984–6003. doi: 10.1021/bi00185a040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ishima R, Torchia DA. Extending the range of amide proton relaxation dispersion experiments in proteins using a constant-time relaxation-compensated CPMG approach. J. Biomol. NMR. 2003;25:243–248. doi: 10.1023/a:1022851228405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cavanagh J. Protein NMR spectroscopy: Principles and practice. 2nd. Amsterdam: Academic Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Piotukh K, Gu W, Kofler M, Labudde D, Helms V, Freund C. Cyclophilin A binds to linear peptide motifs containing a consensus that is present in many human proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:23668–23674. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503405200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kern D, Eisenmesser EZ, Wolf-Watz M. Enzyme dynamics during catalysis measured by NMR spectroscopy. Methods Enzymol. 2005;394:507–524. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)94021-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ke H, Mayrose D, Belshaw PJ, Alberg DG, Schreiber SL, Chang ZY, Etzkorn FA, Ho S, Walsh CT. Crystal structures of cyclophilin A complexed with cyclosporin A and N-methyl-4-[(E)-2-butenyl]-4,4-dimethylthreonine cyclosporin A. Structure. 1994;2:33–44. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(00)00006-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mikol V, Kallen J, Walkinshaw MD. X-ray structure of a cyclophilin B/cyclosporin complex: comparison with cyclophilin A and delineation of its calcineurin-binding domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1994;91:5183–5186. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.11.5183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eisenmesser EZ, Millet O, Labeikovsky W, Korzhnev DM, Wolf-Watz M, Bosco DA, Skalicky JJ, Kay LE, Kern D. Intrinsic dynamics of an enzyme underlies catalysis. Nature. 2005;438:117–121. doi: 10.1038/nature04105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wolf-Watz M, Thai V, Henzler-Wildman K, Hadjipavlou G, Eisenmesser EZ, Kern D. Linkage between dynamics and catalysis in a thermophilic-mesophilic enzyme pair. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2004;11:945–949. doi: 10.1038/nsmb821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Camilloni C, Sahakyan AB, Holliday MJ, Isern NG, Zhang F, Eisenmesser EZ, Vendruscolo M. Cyclophilin A catalyzes proline isomerization by an electrostatic handle mechanism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2014;111:10203–10208. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1404220111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zoldak G, Aumuller T, Lucke C, Hritz J, Oostenbrink C, Fischer G, Schmid FX. A library of fluorescent peptides for exploring the substrate specificities of prolyl isomerases. Biochemistry. 2009;48:10423–10436. doi: 10.1021/bi9014242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ke H. Similarities and differences between human cyclophilin A and other beta-barrel structures. Structural refinement at 1.63 A resolution. J. Mol. Biol. 1992;228:539–550. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90841-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.