Abstract

The fluorescence ubiquitination cell cycle indicator (FUCCI) system provides a powerful method to evaluate cell cycle mechanisms associated with stem cell self-renewal and cell fate specification. By integrating the FUCCI system into human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs) it is possible to isolate homogeneous fractions of viable cells representative of all cell cycle phases. This method avoids problems associated with traditional tools used for cell cycle analysis such as synchronizing drugs, elutriation and temperature sensitive mutants. Importantly, FUCCI reporters allow cell cycle events in dynamic systems, such as differentiation, to be evaluated. Initial reports on the FUCCI system focused on its strengths in reporting spatio-temporal aspects of cell cycle events in living cells and developmental models. In this report, we describe approaches that broaden the application of FUCCI reporters in PSCs through incorporation of FACS. This approach allows molecular analysis of the cell cycle in stem cell systems that were not previously possible.

Keywords: cell cycle, pluripotent stem cells, differentiation, epigenetics

1. Introduction

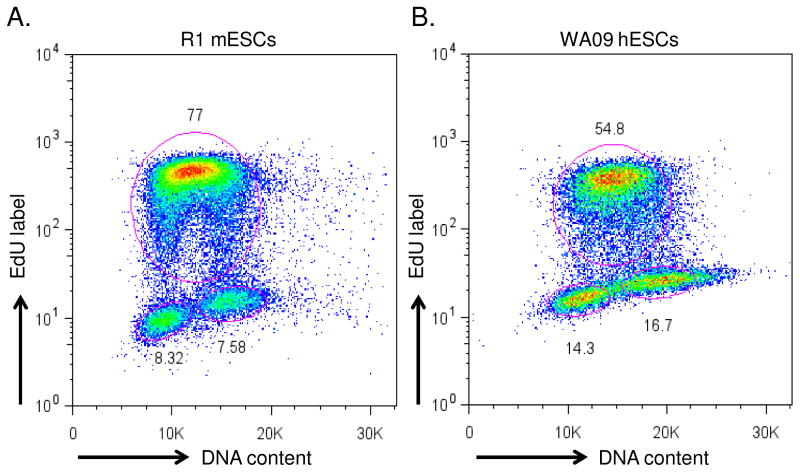

Human and mouse pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs and mPSCs, respectively) have an unusual cell cycle structure comprised of short G1 and G2 gap-phases (Figure 1). At any point in time >50% of PSCs are in S-phase, primarily because of the short intervening time between replicative and mitotic phases [1]. This structure is considerably different from somatic cells that devote more time to G1-phase and show characteristically slower division rates. During differentiation of PSCs, the cell cycle remodels such that the time taken to transition through G1- and G2-phase increases and the rate of cell division decelerates. This general pattern of cell cycle regulation is also exhibited by peri-implantation stage PSCs in vivo [1].

Figure 1.

Cell cycle structure of murine and human ESCs. A. Two-dimensional cell cycle analysis of murine and human embryonic stem cells (ESCs) where the X-axis indicates DNA content of the cell through propidium iodide staining and the Y-axis indicates cells in S-phase by incorporation of EdU, over a 15 min brief pulse-label period. PSCs typically have short gap phases and proportionally, are heavily enriched in S-phase cells.

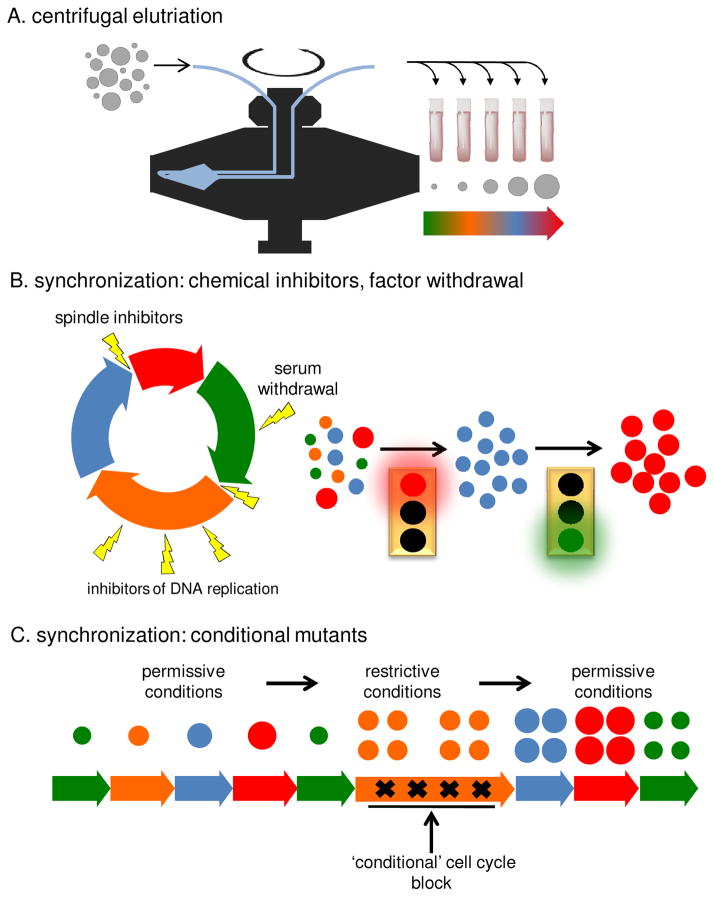

The atypical cell cycle structure of PSCs has attracted intense interest and has led to various models proposing links between cell cycle regulation and maintenance of the pluripotent state. A long-standing idea has been that PSCs retain a short G1-phase that somehow favors self-renewal over exit from pluripotency and, that initiation of PSC differentiation occurs during G1-phase [1,2]. The latter concept is intriguing because it provides a potential link between the cell cycle and fate decisions and would imply that transition through G1-phase is mechanistically linked to initiation of differentiation [1]. Bringing these ideas to a conclusion has been difficult however, due to technical limitations associated with tools previously used for cell cycle analysis (Figure 2). For example, in our experience conventional approaches such as the use of synchronizing drugs are problematic due to their inherent cytotoxicity and perturbation of cell cycle events. Centrifugal elutriation has also been used to a lesser extent in PSCs [3] and although useful, is hampered by limitations in the resolution of cell cycle phases and because specialist equipment is required. Finally, factor withdrawal to impose a G0 arrest is ineffective and leads to differentiation of PSCs [4] and, other tools such as temperature-sensitive mutants are not generally available.

Figure 2.

Methods for isolating cells at equivalent phases of the cell cycle. A. Centrifugal elutriation fractionates cells according to size by varying the balance between centrifugal force generated by rotation of the elutriation rotor and forces generated by continuous flow of media through the elutriation chamber chamber in a direction that opposes the centrifugal force. B. Cell cycle inhibitors can be used to arrest cells at defined points in the cell cycle. These include inhibitors of DNA replication (aphidicolin, hydroxyurea, mimosine and thymidine) and inhibitors of mitotic spindle formation (nocodazole, colchicine). Alternatively, cells can be blocked by addition of cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitors or by factor withdrawal, such as fetal calf serum depletion (Go arrest). Following arrest, cells are released as a synchronous wave by washing away the cell cycle inhibitor or, by replenishing media with serum or other factors. C. Cells can be synchronized by inducing a conditional cell cycle blockade. This typically involves switching from a ‘permissive’ temperature to a ‘restrictive temperature and requires a specific temperature sensitive mutation in a key cell cycle regulatory gene. Release from the block is achieved by switching back to the permissive temperature allowing the cell cycle molecule to regain function. This releases cells from the block in a synchronous wave.

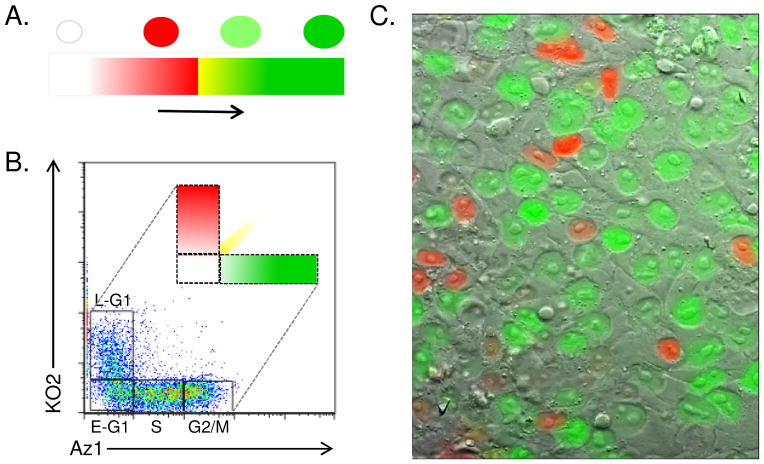

In 2008, Miyawaki and colleagues described the first fluorescent-protein based approach to monitor and isolate living cells in different phases of the cell cycle [4]. This system, termed FUCCI for Fluorescent Ubiquitinated-Cell Cycle Indicator, exploits cell cycle-regulated oscillations in the stability of two cell cycle regulated proteins. The first, CDT1, accumulates in G1 phase due to enhanced stability and then as cells enter S-phase it is degraded by ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis. The second protein, GEMININ, accumulates from early S-phase through to M-phase. Periodicity of protein stability is important for the respective functions of CDT1 and GEMININ and in each case, destruction is regulated by a small peptide motif known as a degron that directs cell cycle-dependent proteolysis. The FUCCI system exploits cell cycle regulated degron-sequences by fusing them to one of two fluorescent proteins with non-overlapping excitation and emission wavelengths; Kusabira Orange-2 (KO2) and Azami Green (Az1). The resulting fusion proteins turnover in a cell cycle-dependent manner that mirrors the accumulation of native CDT1 and GEMININ, allowing them to be used as accurate reporters of cell cycle position at the single cell level in living cells (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

FACS-isolation of FUCCI cell cycle fractions. A. Color scheme representing changes in FUCCI reporters over the cell cycle. B. Two-dimensional FUCCI profile measuring KO2 (Y-axis) and Az1 (X-axis). Cells can be isolated by FACs to generate pure populations of early G1 (double negative), late G1 (orange), S-phase (low green), G2 and M-phase cells (high green). Double positive (KO2+ and AZ1+) cells (‘yellow’) can also be isolated along a diagonal to isolate very early S-phase cells. C. Image of FUCCI cells taken on Viva View microscope system. This image is part of a video of live growing FUCCI hESCs (see Supplementary Video 1). 40x mag.

The FUCCI system exploits transition of cells through different color states, indicative of cell cycle position. Directly following mitosis (early G1), cells become double negative (DN) for both fluorescent reporters but as they transition through G1, orange fluorescence (KO2+) progressively increases. The transition from DN to KO2+ allows early and late G1 cells to be readily separated. Previously, isolation of cells at different stages of G1 was possible by elutriation, which sorts on the basis of cell volume or, by drug synchronization that separates cells based on post-release time (Figure 2). Both of these approaches don’t specifically result in isolation of single cells at a defined stage of G1 because of the isolation criteria used (e.g. volume, time). The FUCCI system offers a solution to these limitations because it precisely identifies cells functionally, based on the biochemical state of the cell. Upon entry into S phase, KO2 begins to be degraded and Az1 is stabilized, resulting in a brief period where cells are double positive for green and orange fluorescence. As KO2 is degraded, cells become increasingly green as they progress through S-phase (AzL). Finally, as cells enter G2, Az1 accumulates to higher levels reaching a maximum at the end of each cell cycle (Az-high, AzH). These fluorescent reporters allow live cells to be tracked as they progress through the cell cycle in vitro and in vivo, allowing temporal and spatial aspects of cell cycle regulation to be characterized in ways that were not previously possible [4].

Another advantageous feature of the FUCCI system is that cells from each stage of the cell cycle can be isolated by fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS) and used for additional single cell or population-based experiments; including studies of differentiation, trans-differentiation and reprogramming. While some viable DNA-binding dyes such as Hoechst 33342 and Vybrant Dye Cycle (Life Technologies) can also be used for FACs isolation of cells, this approach is somewhat limiting because cell cycle fractionation is based on cellular DNA content and therefore, it has limitations with regards to early and late G1-phase separation. Overall, the establishment of the FUCCI system provides tremendous benefits to researchers interested in the role of the cell cycle in development and disease and has resulted in many publications since first being reported seven years ago in models ranging from flies to human stem cells.

Several studies have now described the utility of FUCCI reporters in mouse and human PSCs and established new aspects of pluripotent cell biology [5–10]. One important finding has been confirmation that PSCs initiate the differentiation program from the G1-phase and that this represents a “window of opportunity” where cells make fate decisions [7, 8, 11–13]. As one example, we have recently used FUCCI indicators to identify genes that are cell cycle-regulated in PSCs by performing FACS of cell cycle fractions followed by RNA-sequencing. Surprisingly, transcription of developmental genes increases during late-G1 thereby contributing to stem cell heterogeneity but more importantly, indicating that PSCs are poised for differentiation at this time. Activation of developmental genes in late-G1 requires signals generated by retinoid, WNT, FGF, BMP and TGFβ family-members indicating that cell cycle and cell signaling pathways converge to control fate decisions. Epigenetic marks such as 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC) also appear to oscillate during the cell cycle, indicating a deeper layer of regulation in response to G1 transition. Detailed information on 5hmC assays is already available [14–16]. Overall, these findings illustrate the utility of FUCCI in characterization of PSCs and how it can be used to address questions that were previously intractable. In the following sections we will provide a framework for how the FUCCI system can be established and utilized in hPSCs.

2. Materials and methods

2.1 Construct design considerations

Obtaining stable, ectopic expression of transgenes in hPSCs can sometimes be problematic and promoters used to drive transcription are an important variable. The cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter for example is unreliable due to silencing. Instead, EF1α, PGK1 and UBC promoters are better options and provide different levels of expression. The most reliable, constitutive promoter used in PSCs however, is the CAG promoter that consists of chicken beta-actin 5′ regulatory sequences flanked by the CMV enhancer [17]. We therefore expressed CDT1-KO2 and GEMININ-AZ1 fusion genes from the CAG promoter because robust expression is required in this system. We also strongly recommend coupling the expression of genes to an internal ribosome entry site (IRES)-linked drug-resistance marker such as puromycinr, neomycinr, blastacidinr, or zeocinr. This approach significantly increases the yield of desired cell lines by reducing the frequency of ‘false positive’ clones. As with other cell types, does-response experiments should be performed to determine the level of drug required to eliminate cells not carrying the IRES-drug marker transgene [8, 18–21].

2.2 Establishment of FUCCI expression plasmids

FUCCI reporter constructs in the pcDNA3 backbone were a gift from Miyawaki and colleagues [4]. PCR amplification of gene fragments from pcDNA3 utilized modified T7 and SP6 primers. Primers were engineered to have Eco R1 restriction sites at their 5′-ends. PCR amplification of inserts can be achieved using most commercially available heat-stable polymerases, preferably with proofreading activities under standard conditions. We routinely use Platinum Pfx DNA polymerase (Invitrogen) for this type of PCR amplification. We used 100 ng of template plasmid with 0.5 μM of each primer with 1 unit of polymerase. All other components (amplification buffer, dNTP, MgSO4) were used according to manufacturer guidelines. PCR amplification was performed with 35 cycles comprising (1) denaturation at 94 °C for 15 sec, (2) annealing at 55 °C for 30 sec and (3) extension at 68 °C for 2 min. Following PCR amplification, samples were purified using the PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen) and subjected to gel electrophoresis to confirm amplification. Next, amplicons for CDT1-KO2 and GEMININ-AZ1 were digested with Eco R1 (New England Biolabs) for 8 h at 37 °C according to manufacturer protocols. In addition, approximately 5 μg pCAG-IRES-PURO and pCAG-IRES-NEO vectors were digested with Eco R1 for vector preparation. Following digestion, cut vector was treated with 1 μl calf intestinal phosphatase CIP (New England Biolabs) for 1 h. Next, digested inserts and plasmids were subjected to gel electrophoresis and DNA bands were excised using a clean scalpel and purified using the Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen). DNA concentrations were measured using a NanoDrop instrument (Thermo Scientific).

Ligations were then performed using a 3:1 molar ratio of insert to plasmid, using the DNA Ligation Mighty Mix Kit (Takara) overnight at 16 °C according to manufacturer protocols. The CDT1-KO2 fragment was ligated into pCAG-IRES-PURO and GEMININ-AZ1 was ligated into pCAG-IRES-NEO. Following ligation, 1 μl of each ligation mixture was transformed into Max Efficiency DH5α E. coli (Invitrogen) and plated onto LB agar plates supplemented with carbenicillin (100 μg/ml). Colonies were selected and then grown overnight in LB supplemented with carbenicillin (100 μg/ml) and used for plasmid isolation using the Miniprep Kit (Qiagen). Restriction digests were performed to confirm that ligations were successful and then, individual plasmids were selected for DNA sequencing. Clones of interest were then amplified in 100 ml cultures and DNA isolated using the HP Endotoxin-Free Maxiprep kit (Sigma).

3. Transfection and cell line engineering

Commercially available chemically-defined media (CDM) that work well for cell line selection include StemPro (Life Technologies) and mTeSR™ (StemCell Technologies™). We find that culture of hPSCs in CDM under feeder-free conditions is preferable to that on fibroblast feeder layers in undefined media containing components such as fetal calf serum for a number of reasons. First, contaminating feeder cells are not an issue when culturing on matrices such as Matrigel® (Corning), Geltrex® (Life Technologies) or fibronectin. Second, CDM is less prone to batch-to-batch variations, causes less experimental variability and has predictable levels of bioactive components that can vary significantly between batches of fetal calf serum. Third, CDM are less complex formulations and PSCs respond better to differentiation cues in CDM compared to serum containing conditions. WA09 hESCs, maintained in CDM [19,21,22], are passaged as single-cells using Accutase® (Invitrogen)[19]. Finally, although not directly applicable to the FUCCI studies described here, CDM are more appropriate for product development if use of cell products in humans is anticipated [23].

Transfection efficiency of hPSCs is frequently problematic due to potentially low efficiency of transfection with some lipid-based reagents and high cell death with electroporation-based approaches. Use of endotoxin-free DNA is an important factor. We have also found that optimizing the concentration of DNA used in lipofection-based transfections improves efficiencies and survival. Transfection efficiencies are typically in the 40–70% range, depending on plasmid size.

We initially generated single FUCCI reporter lines (KO2 or AZ reporters alone) so that controls were available for FACs gating purposes. Once individual KO2 or AZ lines were validated, the second reporter was introduced. For convenience, it is also possible to introduce reporters simultaneously if dual drug selection is employed. Transfection of the KO2 reporter is now described as an example. To begin, 1 × 106 hESCs were seeded on a 35 mm tissue culture plate pre-coated with Geltrex® (diluted 1:200 with DMEM/F-12 (Life Technologies) for 30 min. The next day, 10 μg of pCAG-CDT1-KO2 plasmid was transfected into the cells, as follows. First, 150 μl of DMEM/F-12 media was placed into two 1.5 ml microcentrifuge tubes. Second, 10 μl of Lipofectamine-2000 (Invitrogen) was added to tube-1 and 10 μg of pCAG-CDT1-KO2 was placed into tube-2, and incubated for 5 min at room temperature. Third, the tube-2 mixture was mixed with tube-1 and incubated for a further 20 min at room temperature. Next, fresh culture media was added to cells and the transfection mixture was added drop-wise with very gentle swirling of the plate to mix. Fifth, cells were incubated overnight. Finally, media was switched as before but supplemented with puromycin (0.1 μg/ml)- drug selection was maintained for two weeks. Once KO2 reporter cell lines were established, cells were transfected with 10 μg of pCAG-GEMININ-AZ1 using an identical protocol as described above except that media was supplemented with neomycin (200 μg/ml). Stable cell lines were frozen in defined media with 10% DMSO using a Mr. Frosty™ (Thermo Scientific) and stored long-term in liquid nitrogen.

4. Downstream analyses with FUCCI hPSCs

4.1 Live-cell imaging

An important feature of the FUCCI system is that cell cycle dynamics can be evaluated in space and time in living cultures and tissues. We have had considerable success using an Olympus Viva View FL incubator-microscope system (Olympus) at 37 °C, 5% CO2 to image hESCs progressing through the cell cycle (Figure 3C; Supplementary Video 1). This approach unambiguously shows that the FUCCI system faithfully reports cell cycle position and allows cell division times to be directly monitored [8]. In cells lacking FUCCI indicators this can be problematic as it is difficult to track cells but, the FUCCI color system alleviates this problem. Using time-lapse microscopy the mean cell cycle length is between 14–20 hours, depending on cell line and cell density. Proliferation rates of human PSCs are heavily influenced by cell density.

To view FUCCI hESCs, a 35 mm plate containing a glass chamber slide was pre-coated with Geltrex® (1:200; Life Technologies) for 30 min. FUCCI hESCs (1 × 106) were passaged and re-plated on coated plates in fresh pre-warmed media. Cells were culture for 2 days under standard conditions with daily media changes. Cells were next placed in the incubator and allowed to equilibrate for 6 h. Imaging (40x mag) was performed every 15 min for 24 h for DIC (25 ms exposure), green fluorescence and orange fluorescence (100 ms exposure). Images were merged and movie files collated. Files (.MOV Quicktime) were typically 5–10 Mb. Other types of time-lapse fluorescence instruments with temperature and gas controlled environments can also be used for this purpose.

Live imaging of FUCCI cells may be of value to determine cell cycle kinetics of pluripotent cells in different regions of a colony, where positional effects impact cell behavior. It will also be of value to characterize variations in cell division rates at the single cell level [9]. Quite often, cell cycle data is expressed as a function of the entire population. Microscopic imaging of individual cells would provide insight into variations across the population and potentially in different regions of the tissue culture vessel. In differentiating cells, changes in cell cycle progression could also be monitored as cells exit pluripotency [8,25]. It may also be possible to use the FUCCI system in combination with real-time readouts for gene expression and cell signaling. For example, FRET/FRAT analysis could be measured in the cell cycle to evaluate protein-protein interactions and signaling activity. Likewise, RNA dynamics in living cells could be evaluated as a function of cell cycle phase using technology such as SmartFlare™ (Millipore). In principal, FUCCI technology can be used in conjunction with a wide variety of other assays that measure cellular processes in living cells. The true power however of FUCCI from a temporal-spatial point of view is in model organisms where transgenic models expressing cell cycle reporters have been developed [4].

4.2 Fluorescent Activated Cell Sorting (FACS)

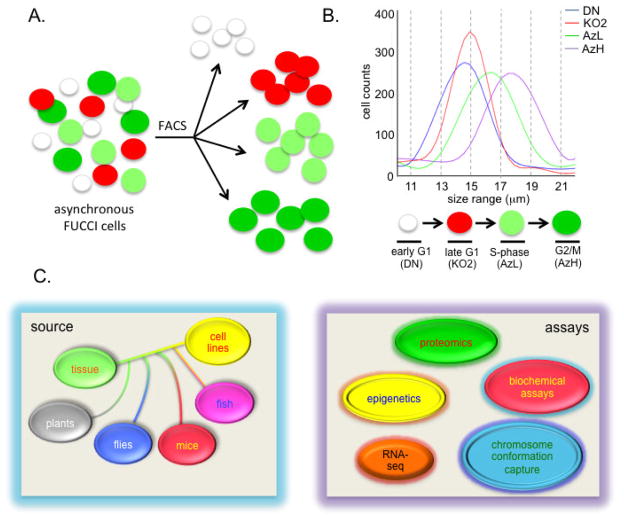

We routinely sort FUCCI hESCs into four cell cycle fractions; a double-negative fraction representing early-G1 cells, an orange-only fraction (KO2+) comprising late-G1 cells, weakly-expressing green cells (Az1-low) in S-phase, and highly-expressing green cells (Az-high) that comprise G2/M (Figure 3,4). Early S-phase populations can be isolated by sorting double-positive cells (KO2+/Az1+) but typically, the frequency of these cells is low due to the brief time period associated with the ‘yellow’ state in hESCs. In principal, the FUCCI cell cycle can be dissected into many more fractions if the cell sorter being used is capable of collecting >4 populations simultaneously. This can potentially increase the temporal resolution of cell cycle events but for many purposes this may not be necessary.

Figure 4.

Cell size determination of FUCCI cell cycle fractions. A. A diagram showing FUCCI fractions following isolation by FACS (see Figure 3). B. Cell size determination of FUCCI cell cycle fractions using a Coulter Counter. As cells transition through the cell cycle, cell volume increases. C. Potential applications for FUCCI cell cycle analysis. Left panel: highlights the sources of FUCCI cells currently available including cultured cell lines and transgenic flies, mice, fish and plants. Right panel: these FUCCI sources can be used for downstream molecular analysis if combined with cell sorting. Potential applications include RNA-seq, analysis of epigenetic marks (DNA methylation, histone modifications), chromosome conformation capture assays (Hi-C, 4C-seq, 5C-seq, ChIA-PET etc.) and a range of biochemical assays (immunoprecipitations, immunoblots etc.) and proteomics.

To prepare FUCCI expressing hESCs for FACS, we typically grow six 10 cm dishes to confluency (3–4 d after initial seeding at 3.5 × 106 cells per plate). Each plate of cells is washed with PBS and treated with 5 ml of Accutase® for 5 min at 37 °C. An equal volume of PBS is added followed by gently mixing to generate a single-cell suspension. Following centrifugation at 1000 rpm for 5 min, cells were resuspended in fresh media (1 ml per plate, ~1.5 × 107 cells). Cells were passed through a cell strainer (0.2 μm) to remove aggregates and kept on ice.

FUCCI hESCs are routinely sorted on a Beckman Coulter MoFlo XDP using excitation of 488 nm for Az1 and 561 nm for KO2. We recommend keeping cells at 4 °C, sorting with a 100 μm tip at 25 psi. The G1 populations (DN and KO2) are typically the limiting component, each comprising ~10% of the entire population. Most PSCs (typically >50%) will be in S-phase. We typically scale down the S- and G2/M fractions so that equal cell numbers of each population are used for downstream assays. Approximately 4–6 × 106 cells per cell cycle fraction are routinely obtained by this approach. Cells sorted at 4 °C do not progress through the cell cycle and remain viable as long as they are kept in the refrigerator and in suspension, allowing for FACS isolations of 6–8 h continual sorting time. Sorted cells should be re-analyzed to confirm that little-to-no drift in cell cycle position occurred.

Following sorts, cells can be pooled, flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C. It is also possible to pool cells from multiple sorts following storage at −80 °C. This is sometimes necessary for assays such as ChIP-seq, chromatin conformation capture assays (4C-seq analysis etc.). For interested readers, we refer them to a detailed 4C-seq methods paper published elsewhere [24]. Cell size increases during the cell cycle and as anticipated, isolation of FUCCI fractions during cell cycle progression allows for cells of increasing volume to be isolated (Figure 4). Precise cell volume can be determined from these fractions using a Coulter counter and bead standards of known volume. This has potential utility for investigating the link between cell cycle and cell volume controls.

4.3 Transcript analysis, immunoblotting and immunostaining

Expression profiling of transcript levels can be performed using standard approaches, either with TRIzol (Life Technologies) or commercially available RNA isolation kits (e.g. QIAGEN, ZYMO, Roche Life Sciences). We have had success using RNA isolation kits from Omega Bio-Tek with ~100,000 (or more) FUCCI-sorted cells following manufacturer recommendations. RNA levels are measured on a NanoDrop instrument to determine concentration and purity. Similarly, cDNA synthesis can be performed using standard kits. We have used the iScript Reverse Transcription Supermix (Bio-Rad) with 1 μg of RNA following manufacturer recommendations. Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) is performed using TaqMan assays (Life Technologies) or SYBR Green-based kits (e.g. Life Technologies, QIAGEN, Promega, Sigma) with custom-designed oligonucleotide primers.

Immunoblotting of FACS-isolated FUCCI fractions is performed using standard approaches. Cells are lysed in RIPA buffer (Life Technologies, Catalog # 89900) with protease and phosphatase inhibitors. A 1:1 ratio of cell pellet to RIPA volume is recommended. Following resuspension of the cell pellet in cold RIPA, cells should be placed on ice for 30 min. Cell debris is then pelleted for 10 min at maximum speed in a microcentrifuge. Supernatant can then be removed and protein concentration determined using a standard Bradford assay (BioRad, for example). Protein samples can then be adjusted to equal concentration and mixed with 2 times (2x) Laemmli sample buffer (65.8 mM Tris-HCl pH 6.8, 26.3% glycerol, 2.1% SDS, 0.01% bromophenol blue) and heated at 95 °C for 5 min immediately prior to gel loading. SDS-PAGE is then performed with FUCCI fractions samples, using 10–20 μg total protein per lane. Following electrophoresis, proteins are transferred to nitrocellulose or PVDF membranes and immunoblotted using standard approaches.

Immunostaining of FUCCI cells can be problematic because KO2 and Az1 fluorescent proteins undergo rapid photo-bleaching. Fixation of cells in 4% formaldehyde for 5 min is adequate. Cells are then washed in PBS and used immediately for immunostaining. We typically block and permeabilize in a single step containing 10% donkey serum in PBS with 0.2% Triton X-100 for 1 h at room temperature. Next, primary antibodies in the same buffer are used by overnight incubation at 4 °C. The following day, probed cells are washed three times in PBS with 0.2% Triton X-100 for 5 min each, and then incubated with conjugated secondary antibody, such as Alexa Fluor 633 or 647, for 1 h in PBS with 10% donkey serum, 0.2% Triton X-100 at room temperature. Next, cells are washed as before and mounted using Prolong Gold Anti-Fade reagent. It is best to perform imaging within 24 h or less and to maintain slides in the dark.

4.4 Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP)

Quantitative chromatin immunoprecipitation (qChIP) or ChIP-seq assays on FUCCI fractions provide an opportunity to evaluate protein-DNA interactions that occur in a cell cycle-dependent manner. Using FUCCI hESCs, we have evaluated the differential enrichment of histone epigenetic marks and transcription factor binding during the cell cycle [25]. These studies have provided new insight into how the cell cycle and signaling pathways converge to regulate bivalent, developmental genes in G1-phase.

To perform ChIP assays we typically begin with approximately 5 × 106 cells isolated by FACS for each cell cycle fraction. Cell pellets are resuspended in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and fixed in freshly prepared 1% (final concentration) methanol-free formaldehyde (Pierce™ 16% formaldehyde [w/v]) for 5 min at room temperature on a rotary shaker. Use of methanol-free formaldehyde is essential to prevent over-fixation that typically occurs using commercial-grade formaldehyde solutions buffered in methanol- this interferes with efficient sonication. Fixation is quenched by addition of 1:20 volume of 2.5 M glycine on a rotary shaker for 5 min. Cells are then washed in 10 ml of PBS and centrifuged for 5 min at 1000 rpm. Finally, cell pellets are flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C.

For ChIP procedure, we follow the original ChIP on Chip protocol described by Agilent (http://www.chem.agilent.com/library/usermanuals/Public/G4481-90010_ChIP-on-chip_Protocol_v.11.2.pdf). We have modified the protocol by using only 1 ml of each Lysis Buffers (Buffers 1, 2, and 3). Samples are sonicated with a Covaris S2 Sonicator for 8 min (peak power 140, duty factor 5, and cycle/burst 200). DNA pellets are resuspended in 100 μl of molecular grade water for qPCR assays or, 20 μl if performing DNA sequencing. Quantitation of DNA and size range determination is performed on a Qubit fluorimeter (Life Technologies) and Fragment Analyzer (Advanced Analytical Technologies), respectively. Following sonication, optimal fragment size should be between 200 and 500 base pairs.

To perform qPCR following ChIP, 2 μl (1:50) of the IP is used in a 10 μl total reaction with user-defined primer sets. We typically utilize SYBR-FAST qPCR master mix by KAPA Biosystems, which perform best in our experience. In addition to performing several biological replicates, all qPCR assays should be performed in technical triplicate to help account for minor pipetting errors. To perform Next-Gen sequencing following ChIP, we typically outsource this procedure to the Hudson Alpha Institute for Biotechnology, Genomics Services Laboratory (Huntsville, Alabama).

5. Conclusions

Here we have outlined broad utility of the FUCCI reporter system in human PSCs and have shown how it can be used to unravel biological processes that were previously intractable. Specifically, we have highlighted the power of this system as an enabling tool to analyze how the cell cycle coordinates the processes governing self-renewal and differentiation. By utilizing this system, we have found that the cell cycle position is a major contributor to heterogeneity within stem cell populations and that this is a major factor controlling the initiation of cell fate decisions [6]. In the future, we suggest that single-cell analysis of the epigenome and transcriptome within FUCCI cell cycle fractions should be used to elucidate the importance of heterogeneity within stem cell populations. Moreover, it should be possible to perform FUCCI analysis for similar assays from freshly isolated tissue, allowing the investigation of cell cycle coupled processes to be performed in an in vivo context. In summary, establishment of the FUCCI system in human PSCs has opened up new opportunities to evaluate how the cell cycle impacts cell identity and cell fate choice with a precision that has not been previously possible. Further use of the FUCCI system will no doubt unravel numerous mysteries that have plagued cell cycle and stem cell researchers for many years.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Establishment of FUCCI cell cycle reporters in human pluripotent cells

Methods for efficient isolation of cell cycle fractions by FACS

Applying the FUCCI system for biochemical and molecular cell cycle analysis

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants to SD from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (HD049647) and the National Institute for General Medical Sciences (GM75334). We thank Julie Nelson for assistance with FACS.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Singh AM, Dalton S. Cell stem cell. 2009;5:141–149. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mummery CL, van Rooijen MA, van den Brink SE, de Laat SW. Cell differentiation. 1987;20:153–160. doi: 10.1016/0045-6039(87)90429-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sela Y, Molotski N, Golan S, Itskovitz-Eldor J, Soen Y. Stem cells. 2012;30:1097–108. doi: 10.1002/stem.1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sakaue-Sawano A, Kurokawa H, Morimura T, Hanyu A, Hama H, Osawa H, Kashiwagi S, Fukami K, Miyata T, Miyoshi H, Imamura T, Ogawa M, Masai H, Miyawaki A. Cell. 2008;132:487–498. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Calder A, Roth-Albin I, Bhatia S, Pilquil C, Lee JH, Bhatia M, Levadoux-Martin M, McNicol J, Russell J, Collins T, Draper JS. Stem cells and development. 2013;22:279–295. doi: 10.1089/scd.2012.0168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coronado D, Godet M, Bourillot PY, Tapponnier Y, Bernat A, Petit M, Afanassieff M, Markossian S, Malashicheva A, Iacone R, Anastassiadis K, Savatier P. Stem cell research. 2013;10:118–131. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2012.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pauklin S, Vallier L. Cell. 2013;155:135–147. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.08.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singh AM, Chappell J, Trost R, Lin L, Wang T, Tang J, Wu H, Zhao S, Jin P, Dalton S. Stem cell reports. 2013;1:532–544. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2013.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jovic D, Sakaue-Sawano A, Abe T, Cho CS, Nagaoka M, Miyawaki A, Akaike T. SpringerPlus. 2013;2:585. doi: 10.1186/2193-1801-2-585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roccio M, Schmitter D, Knobloch M, Okawa Y, Sage D, Lutolf MP. Development. 2013;140:459–470. doi: 10.1242/dev.086215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chetty S, Pagliuca FW, Honore C, Kweudjeu A, Rezania A, Melton DA. Nature methods. 2013;10:553–556. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jonk LJ, de Jonge ME, Kruyt FA, Mummery CL, van der Saag PT, Kruijer W. Mechanisms of development. 1992;36:165–172. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(92)90067-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Filipczyk AA, Laslett AL, Mummery C, Pera MF. Stem cell research. 2007;1:45–60. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yu M, Hon GC, Szulwach KE, Song CX, Jin P, Ren B, He C. Nature protocols. 2012;7:2159–2170. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu M, Hon GC, Szulwach KE, Song CX, Zhang L, Kim A, Li X, Dai Q, Shen Y, Park B, Min JH, Jin P, Ren B, He C. Cell. 2012;149:1368–1380. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang T, Wu H, Li Y, Szulwach KE, Lin L, Li X, Chen IP, Goldlust IS, Chamberlain SJ, Dodd A, Gong H, Ananiev G, Han JW, Yoon YS, Rudd MK, Yu M, Song CX, He C, Chang Q, Warren ST, Jin P. Nat Cell Biology. 2013;15:700–711. doi: 10.1038/ncb2748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Okabe M, Ikawa M, Kominami K, Nakanishi T, Nishimune Y. FEBS letters. 1997;407:313–319. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00313-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bechard M, Trost R, Singh AM, Dalton S. Molecular and cellular biology. 2012;32:288–296. doi: 10.1128/MCB.05372-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Singh AM, Reynolds D, Cliff T, Ohtsuka S, Mattheyses AL, Sun Y, Menendez L, Kulik M, Dalton S. Cell stem cell. 2012;10:312–326. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith KN, Singh AM, Dalton S. Cell stem cell. 2010;7:343–354. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang L, Schulz TC, Sherrer ES, Dauphin DS, Shin S, Nelson AM, Ware CB, Zhan M, Song CZ, Chen X, Brimble SN, McLean A, Galeano MJ, Uhl EW, D’Amour KA, Chesnut JD, Rao MS, Blau CA, Robins AJ. Blood. 2007;110:4111–4119. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-03-082586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Menendez L, Yatskievych TA, Antin PB, Dalton S. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:19240–19245. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1113746108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schulz TC. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2015;4:927–931. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2015-0058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van de Werken HJ, de Vree PJ, Splinter E, Holwerda SJ, Klous P, de Wit E, de Laat W. Methods Enzymol. 2012;513:89–112. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-391938-0.00004-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Singh AM, Sun Y, Li L, Zhang W, Wu T, Zhao S, Qin Z, Dalton S. Stem cell reports. 2015;5:323–336. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2015.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.