Abstract

Background

State Medicaid policies play an important role in Medicaid-enrollees' access to and use of opioid agonists, such as methadone and buprenorphine, in the treatment of opioid use disorders. Little information is available, however, regarding the evolution of state policies facilitating or hindering access to opioid agonists among Medicaid-enrollees.

Methods

During 2013-14, we surveyed state Medicaid officials and other designated state substance abuse treatment specialists about their state's recent history of Medicaid coverage and policies pertaining to methadone and buprenorphine. We describe the evolution of such coverage and policies and present an overview of the Medicaid policy environment with respect to opioid agonist therapy from 2004 to 2013.

Results

Among our sample of 45 states with information on buprenorphine and methadone coverage, we found a gradual trend toward adoption of coverage for opioid agonist therapies in state Medicaid agencies. In 2013, only 11% of states in our sample (n=5) had Medicaid policies that excluded coverage for methadone and buprenorphine, while 71% (n=32) had adopted or maintained policies to cover both buprenorphine and methadone among Medicaid-enrollees. We also noted an increase in policies over the time period that may have hindered access to buprenorphine and/or methadone.

Conclusions

There appears to be a trend for states to enact policies increasing Medicaid coverage of opioid agonist therapies, while in recent years also enacting policies, such as prior authorization requirements, that potentially serve as barriers to opioid agonist therapy utilization. Greater empirical information about the potential benefits and potential unintended consequences of such policies can provide policymakers and others with a more informed understanding of their policy decisions.

Keywords: opioid use disorder, policy, buprenorphine

Introduction

Opioid use disorders are a serious public health concern affecting over 2 million individuals in the US.1 Rates of drug-related emergency department visits involving opiates/opioids increased from 21.6 per 100,000 in 2004 to 54.9 per 100,000 in 2011 2 and between 1999 and 2011, overdose deaths related to opioids increased 265% among men and 400% among women (SAMHSA).3

Opioid agonist therapy, such as methadone and buprenorphine, is an effective, costeffective treatment;4-9 however, the majority of individuals with opioid use disorders have not historically received opioid agonist therapy.8,10 The number of opioid treatment programs (OTPs), the only facilities licensed to dispense methadone for treatment of opioid use disorders, remained relatively constant from 2003 to 2011; however the number of clients receiving methadone increased from 227,000 to 306,000 during this time period.11 From 2004 to 2011, the number of clients receiving buprenorphine in OTPs increased from 727 to 7,020; at non-OTPs, the number of clients receiving buprenorphine increased from 1,670 to 25,656.11

Methadone is effective in treating opioid use disorders,7,12,13 but there are a range of potential barriers to methadone treatment, including demanding regulations associated with operating an opioid treatment program,6,14-18 lack of community support,18,19 patient limits, and the common requirement that most patients take their dispensed methadone daily at the clinic.20,21 Buprenorphine mono- and combination- (buprenorphine/naloxone) products were approved for the treatment of opioid use disorders in 2002 and can be prescribed by waivered physicians outside of opioid treatment programs.22 Many experts were optimistic about the potential for buprenorphine to increase access to opioid agonist therapy,23,24 as it provides access for individuals unable or unwilling to attend a methadone-dispensing opioid treatment program.

Medicaid is the largest funder of substance abuse treatment services,25,26 and is likely to support a broader range of opioid agonist treatment than commercial insurance coverage, which is more likely to reimburse for buprenorphine but not methadone services.27 Furthermore, substantial numbers of individuals with opioid use disorders are Medicaid-eligible, 28 and state Medicaid policies can substantially impact potential access to opioid agonist therapy.23,29-34 A range of barriers to accessing opioid agonist therapy, however, exists for many Medicaid-enrollees, 35 including an insufficient ratio of providers to beneficiaries in many communities,36 insufficient availability of appointments and treatment slots within clinics, 37 difficulty for many individuals in rural communities in accessing substance abuse treatment clinics, which are predominantly in urban communities,36 and a reluctance of many providers to accept Medicaid reimbursement rates.38 Despite these challenges, however, Medicaid plays a critical role in the treatment of opioid use disorders, and addressing Medicaid policies is a reasonable first step in improving access for this population. In the years since buprenorphine's approval, states have adopted a range of approaches for supporting and facilitating the use of opioid agonist therapy for Medicaid-enrollees.20 However, there is a paucity of information about whether and how such state policies have evolved over time, as well as how they may affect the majority of Medicaid-enrolled individuals with opioid use disorders who have not historically been in Medicaid managed care or covered by similar types of service delivery or payment reform.39-41

Given Medicaid's importance in the treatment of individuals with opioid use disorders, in this manuscript we focus on how state Medicaid policies regarding opioid agonist therapy have evolved from 2004-2013, to facilitate a more comprehensive understanding of the evolution of state policies for clinicians, policymakers, and advocates. This work provides a resource to state Medicaid and substance abuse treatment agencies, assisting them in understanding the extent to which buprenorphine specific policies have been tried and tested across states, and helping them better understand the extent to which their own approach compares to other states. The examination of policies over a decade facilitates the identification of trends, as well as provides the basis for future analyses examining how changes in state Medicaid policies impact access to opioid agonist therapy and other clinical outcomes among Medicaid-enrollees.

Methods

Data

A survey of state Medicaid and substance abuse treatment officials was conducted during 2013-14 by the National Conference of State Legislatures and the RAND Corporation to better understand the state policy environment with respect to the provision of opioid agonist therapy. We attempted to contact representatives from all states. Behavioral health specialists within each state Medicaid agency (most frequently the state opioid treatment authority or another designated substance abuse treatment specialist) were asked to complete the survey or to provide it to the individual most knowledgeable about Medicaid policies related to methadone and buprenorphine. Respondents were instructed to consider the set of Medicaid behavioral health benefits they felt would be most representative of the state's policies, rather than a specific plan. The survey asked about seven state policies relevant for opioid agonist therapy for Medicaid-enrollees. These included 1) whether the state's Medicaid plan covered buprenorphine; 2) whether the state's Medicaid plan covered buprenorphine in an office-based outpatient treatment setting; 3) whether buprenorphine was on the state's preferred drug list; and whether treatment with buprenorphine required 4) prior authorization, 5) copayments, 6) counseling, and 7) whether the state Medicaid program covered methadone treatment. Respondents were asked to indicate the current status in the state for each policy, and if there had been any changes to that policy since 2003. Respondents who indicated that changes in the policy had occurred were asked to indicate when the changes occurred, and what the policy had been prior to the change(s). In this manuscript we report on responses related to seven state policies relevant to buprenorphine coverage for Medicaid-enrollees likely to facilitate or restrict access to opioid agonist therapy. Follow-up calls and information available from state websites were used to verify and clarify responses. RAND's IRB approved all study procedures.

Analytic Approach

In order to illustrate changes in state opioid agonist therapy policies, we examined changes in state policies over the time period 2004 to 2013. Policies that would be likely to expand Medicaid-enrollees' use of methadone or buprenorphine treatment, such as providing Medicaid coverage of buprenorphine or methadone, including buprenorphine on the preferred drug list, not requiring prior authorization for buprenorphine, not requiring a copayment for buprenorphine, and not requiring concurrent counseling for buprenorphine treatment, were categorized as “supportive” policies. Policies that might potentially increase barriers to the use of opioid agonist therapy, even if the primary intent was to improve the quality of care provided to individuals receiving opioid agonists, were categorized as “potentially restrictive” policies. Such policies included a lack of coverage of methadone or buprenorphine under Medicaid, as well as policies that could potentially increase the cost or hassle associated with opioid agonist use for providers or patients, such as not including buprenorphine of the preferred drug list, requiring prior authorization for buprenorphine, requiring a copayment for buprenorphine, and requiring concurrent counseling for buprenorphine treatment. We created four categories to generalize state policy changes over time for each policy: 1) supportive unchanged over the time period; 2) restrictive policies unchanged over the time period; 3) restrictive policies changed to supportive policies during time period; 4) supportive policies changed to restrictive policies during time period.

We counted the total number of states in each policy change category. We categorized states as those whose (1) State Medicaid programs did not cover buprenorphine or methadone; (2) State Medicaid programs covered methadone, but not buprenorphine; (3) State Medicaid programs covered buprenorphine but not methadone; and (4) State Medicaid programs covered buprenorphine and methadone. We also categorized states with respect to prior authorization policies in 2004, 2007, 2010, and 2013, as states whose (1) State Medicaid programs did not cover buprenorphine; (2) State Medicaid programs cover buprenorphine but require prior authorization; and (3) State Medicaid programs cover buprenorphine and do not require prior authorization.

Results

We received information from 46 states (86% response rate). This included information regarding buprenorphine and methadone coverage in 2013 from 45 states, and complete policy profiles for the entire time frame for 38 states (capturing policy data on 75% of states). No state representatives refused to participate; however, in the instances of non-response we were unable to connect with an individual who would be able to answer our questions. State policies were generally supportive of providing opioid agonist therapy to Medicaid-enrollees, and the majority of state Medicaid policies were relatively stable from 2004 to 2013 (Table 1). Most state Medicaid programs covered methadone and/or buprenorphine over the time period and most state Medicaid programs listed buprenorphine on the preferred drug list.

Table 1. Summary of Changes in State Policies.

| Number of States | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Policy Changes During Study Period (2003-2013) | Policy Change Occurred During Study Period (2003-2013) | |||||

| Policy | Policy Supported Opioid Agonist Therapy | Policy Potentially Restricted Opioid Agonist Therapy | Policy Change Potentially Expanded Access to Opioid Agonist Therapy | Policy Change Potentially Restricted Access to Opioid Agonist Therapy | Not applicable | Insufficient Information |

| Medicaid coverage of methadone | 28 | 14 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Medicaid coverage of buprenorphine (any location) | 29 | 5 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| Medicaid coverage of buprenorphine (physician's office) | 28 | 7 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| Buprenorphine on Preferred Drug List | 23 | 7 | 4 | 0 | 5 | 7 |

| Prior Authorization not required for Medicaid coverage of buprenorphine (among states providing coverage) | 10 | 15 | 0 | 10 | 5 | 6 |

| Medicaid does not require copayment for buprenorphine | 7 | 21 | 0 | 4 | 5 | 9 |

| Counseling not required for buprenorphine | 18 | 8 | 0 | 7 | 5 | 8 |

There were, however, a number of policy changes that occurred over the time period, and some of these increased support of and access to opioid agonist therapy. For example, several state Medicaid programs added buprenorphine or methadone as a covered benefit, but none of the states removed these treatments from coverage. Most states included buprenorphine on the preferred drug list or added it during the time period; no states removed buprenorphine from the preferred drug list.

However, there were also state policy changes that occurred over the time period that were arguably more restrictive of opioid agonist therapy. These included prior authorization policies, which can serve as a barrier to physicians prescribing medications, as well as copayments, which increase the cost to patients of obtaining medications. It also included concurrent counseling requirements, which can serve as a barrier to opioid agonist therapy if such services are not easily accessible and for patients who prefer not to have concurrent counseling services.. No state removed these requirements during the time period.

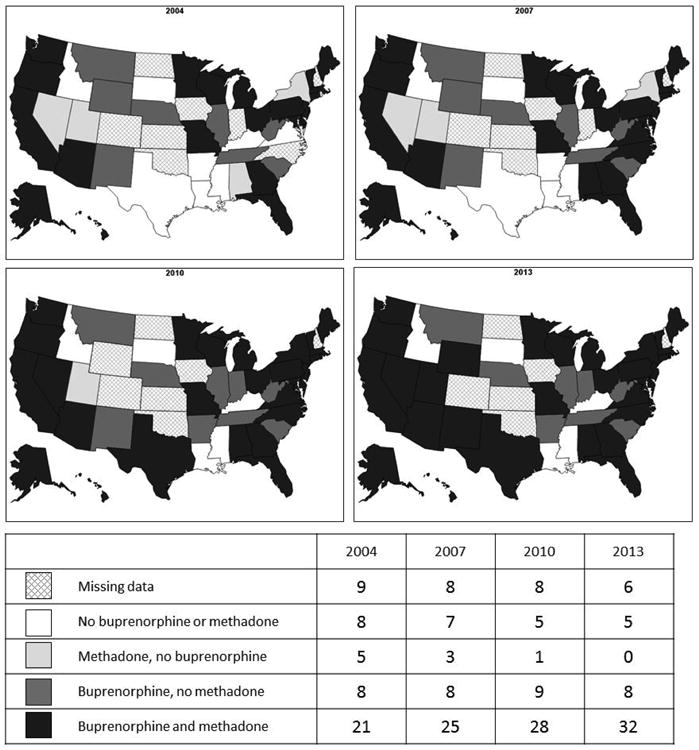

Figure 1 displays the changes in the state Medicaid policy environment with respect to methadone and buprenorphine coverage in 2004, 2007, 2010, and 2013, illustrating an increase in coverage of methadone and buprenorphine among states over the time period, particularly in several northeastern and southwestern states. At the time period's end, all of the states in our sample that covered methadone as a Medicaid benefit also covered buprenorphine. However, not all states that covered buprenorphine also covered methadone treatment.

Figure 1. State Medicaid Coverage of Opioid Agonist Therapy in 2004, 2007, 2010, 2013.

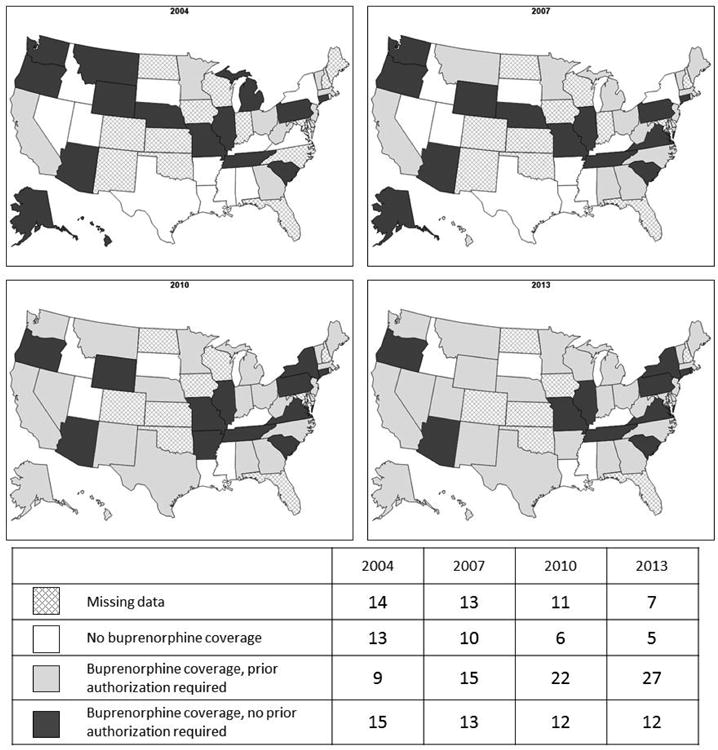

Figure 2 shows that while states increased coverage of buprenorphine, there were also increases in prior authorization requirements, which may limit access to treatment. We did not find any regional pattern among states with prior authorization requirements or lack thereof. The number of states requiring prior authorization for buprenorphine increased threefold during the study time period.

Figure 2. State Medicaid Prior Authorization Requirements for Buprenorphine in 2004, 2007, 2010, 2013.

Discussion

We found that Medicaid state policies shifted toward an increase in coverage of opioid agonist therapy from 2004 through 2013. However, despite increasing evidence regarding the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of opioid agonist therapy,4,27,42-46 some states' Medicaid programs still did not cover both methadone and buprenorphine in 2013, more than a decade after the FDA approval of buprenorphine.

The adoption of policies that influence access to opioid agonist therapy among Medicaid- enrollees was inconsistent throughout the US. While some states had Medicaid coverage of both buprenorphine and methadone along with several policies supporting treatment with buprenorphine, slow adoption of Medicaid coverage in other states may have contributed to the slower than expected adoption of buprenorphine overall.47 We are encouraged to find that states are generally moving in a direction likely to facilitate greater coverage of Medicaid-enrollees access to opioid agonist therapy. It is noteworthy that more states began adopting supportive Medicaid policies in the years subsequent to 2007, when the passage of the Office of National Drug Control Policy Reauthorization Act 48 allowed waivered physicians to obtain permission to treat up to 100 patients with buprenorphine rather than the previous limit of 30 patients. In terms of overall coverage, it appears that state Medicaid coverage of buprenorphine over this time period was not limited to a single region: states in our sample that were located in the northeast and southwest were more likely to have adopted supportive policies during this period than states in other regions.

While we are encouraged to see this increase in overall Medicaid coverage of buprenorphine, state Medicaid requirements that create potential barriers, such as prior authorization, copayments, and concurrent counseling, also increased over the time period, and could contribute to a decrease in buprenorphine use. Despite the clinical benefits of buprenorphine, states may desire to put limits on its use for a range of reasons. For many states, the cost of both the medication and the other services related to prescribing have been a significant concern,49 although some of these concerns may be mitigated to some extent by the availability of generic medications. Widespread buprenorphine availability can also have a range of other downsides, including medical emergencies due to ingestion by children,50-53 diversion, and illicit use,54-57 all of which may prompt policymakers to consider more restrictive policies. Such policies are often designed to increase the likelihood that individuals receive appropriate care and ensure resources are used efficiently, but there are potential unintended consequences of such policies.20 Specifically, prior authorization presents a potential barrier to both providers and patients, and prior authorization may disincentivize providers' use of buprenorphine.58 Copayments have been shown to reduce treatment utilization.59 While counseling requirements may lead to better treatment adherence, it is also possible that this requirement could deter individuals from initiating or continuing treatment with buprenorphine. Further research on the long-term effects of these policy changes on access to treatment is needed to better understand their impact on access to and engagement in opioid agonist treatment overall and among key populations, as well as the outcomes of such treatment, and our description of the changes in such policies over time can provide a foundation for such work.

Our findings must be viewed within the context of the study limitations. Information about policies was gathered retrospectively, and respondents may not know the history of policy changes, or may recall inaccurately. While we sought information from all states for the entire period of time and attempted to verify the information we received, we are missing data from a number of states, and were unable to verify all of the information due to a lack of adequate documentation of policies that have changed over time. Information regarding state policies was collected primarily by survey, and respondents were asked to describe the set of policies that they felt would be most representative of the state's Medicaid policies. State Medicaid policies can be complex, however, with a different set of policies applying to different eligibility groups, or to groups whose care is managed versus being fee-for-service. Administrative limitations within the state Medicaid agency such as high staff turnover or inadequate staffing also potentially limited the information provided by states. It is possible that in some states a different respondent might have described different policies, or may not accurately have recalled the exact year when a policy changed. In situations in which multiple policies exist in a state, empirical analyses are needed to better understand their relative influence. We sought to obtain information about a number of state Medicaid policies pertaining to methadone or buprenorphine that were relevant across the entire time period we examined, and recognize that a range of additional state policies (such as restrictions on length of treatment) likely substantially influence the use of opioid agonist therapy among Medicaid enrollees. Similarly, differences across states, and within states over time, with respect to eligibility for Medicaid, likely has a substantial impact on the number and nature of individuals in a state who receive opioid agonist treatment under Medicaid.

Despite these limitations, our findings suggest a deliberate and persistent trend for states to cover opioid agonist therapies among Medicaid-enrollees but also to implement policies that may impede access to opioid agonist therapies. The data presented are particularly germane at a time when a number of states are expanding access to Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act,60 and there is no clear language in substance abuse parity or minimum mandated benefit laws regarding opioid agonist treatment. Policymakers and other stakeholders can use our findings to better understand how state Medicaid policies have evolved over time. Comparing policy support of opioid agonist therapy between states is also an important result from this research, as it allows state policymakers to learn from each other. Studies are beginning to demonstrate that such state Medicaid policies matter, having been associated with an increase in buprenorphine waivered physicians 61 and the use of opioid agonist therapies and buprenorphine in substance abuse treatment facilities.23,62 However, policymakers' future policy decisions require more detailed information about the impact of such policies on the actual patterns of treatment and outcomes of opioid agonist therapy, and information about state policies in this paper and available from other sources 63 are an important foundation for such analyses.

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to, Mark Sorbero, Andrew Dick, and Carrie Farmer of the RAND Corporation and Laura Tobler of the National Conference of State Legislatures for feedback on prior versions of the manuscript, Erin-Elizabeth Johnson of the RAND Corporation for assistance with the figures, and Gina Boyd, MLIS, of the RAND Corporation, for research assistance and assistance with manuscript preparation.

Funding: The National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) provided support (award 1R01DA032881-01A1) for this study. The study's results and interpretation are those of the authors and do not represent those of NIDA or the NIH.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Ms. Burns and Drs. Stein and Pacula contributed to all stages of the research, from design to manuscript completion. Drs. Gordon and Leslie and Ms. Hendrickson contributed to the research conception, collection of data, and writing of the manuscript. Dr. Bauhoff contributed to the analysis and interpretation of the results and the writing of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Office of Applied Studies SAMHSA. The DASIS Report. [Accessed June 23, 2013];The national survey of substance abuse treatment services (N-SSATS) 2012 system http://www.oas.samhsa.gov/2k3/NSSATS/NSSATS.pdf.

- 2.SAMHSA. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 13-4760, DAWN Series D-39. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration; 2013. Drug Abuse Warning Network, 2011: National Estimates of Drug-Related Emergency Department Visits. [Google Scholar]

- 3.SAMHSA. Substance Use Disorders. [Accessed March 17, 2015];2014 http://www.samhsa.gov/disorders/substance-use.

- 4.Fiellin DA, Pantalon MV, Chawarski MC, et al. Counseling plus buprenorphine-naloxone maintenance therapy for opioid dependence. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(4):365–374. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fudala PJ, Bridge TP, Herbert S, et al. Office-based treatment of opiate addiction with a sublingual-tablet formulation of buprenorphine and naloxone. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(10):949–958. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harris AH, Gospodarevskaya E, Ritter AJ. A randomised trial of the cost effectiveness of buprenorphine as an alternative to methadone maintenance treatment for heroin dependence in a primary care setting. Pharmacoeconomics. 2005;23(1):77–91. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200523010-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mattick RP, Breen C, Kimber J, Davoli M. Methadone maintenance therapy versus no opioid replacement therapy for opioid dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(3):CD002209. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002209.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.American Methadone Treatment Association. Methadone Maintenance Program and Patient Census in the US. New York: American Methadone Treatment Association; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parran TV, Adelman CA, Merkin B, et al. Long-term outcomes of office-based buprenorphine/naloxone maintenance therapy. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010 Jan 1;106(1):56–60. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O'Brien CP. A 50-year-old woman addicted to heroin: review of treatment of heroin addiction. JAMA. 2008;300(3):314–321. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.1.jrr80005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.SAMHSA. The N-SSATS Report: Trends in the Use of Methadone and Buprenorphine at Substance Abuse Treatment Facilities: 2003 to 2011. Rockville, MD: 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lewis DC. Access to Narcotic Addiction Treatment and Medical Care -- Prospects for the Expansion of Methadone Maintenance Treatment. J Addict Dis. 1999;18(2):5–21. doi: 10.1300/J069v18n02_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schwartz RP, Highfield DA, Jaffe JH, et al. A randomized controlled trial of interim methadone maintenance. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(1):102. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.1.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barnett PG. Comparison of costs and utilization among buprenorphine and methadone patients. Addiction. 2009;104(6):982–992. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02539.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barnett PG, Zaric GS, Brandeau ML. The cost-effectiveness of buprenorphine maintenance therapy for opiate addiction in the United States. Addiction. 2001 Sep;96(9):1267–1278. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.96912676.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Connock M, Juarez-Garcia A, Jowett S, et al. Methadone and buprenorphine for the management of opioid dependence: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess. 2007;11(9):1–171. iii–iv. doi: 10.3310/hta11090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Doran CM, Shanahan M, Mattick RP, Ali R, White J, Bell J. Buprenorphine versus methadone maintenance: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003;71(3):295–302. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(03)00169-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oliva EM, Maisel NC, Gordon AJ, Harris AH. Barriers to use of pharmacotherapy for addiction disorders and how to overcome them. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2011 Oct;13(5):374–381. doi: 10.1007/s11920-011-0222-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bell J, Dru A, Fischer B, Levit S, Sarfraz MA. Substitution therapy for heroin addiction. Subst Use Misuse. 2002;37(8-10):1149–1178. doi: 10.1081/ja-120004176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clark RE, Samnaliev M, Baxter JD, Leung GY. The evidence doesn't justify steps by state Medicaid programs to restrict opioid addiction treatment with buprenorphine. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011;30(8):1425–1433. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anstice S, Strike CJ, Brands B. Supervised methadone consumption: client issues and stigma. Subst Use Misuse. 2009;44(6):794–808. doi: 10.1080/10826080802483936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.H.R. 4365--106th Congress. Drug Addiction Treatment Act of 2000. 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ducharme L, Abraham A. State policy influence on the early diffusion of buprenorphine in community treatment programs. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2008;3(1):17–27. doi: 10.1186/1747-597X-3-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bridge TP, Fudala PJ, Herbert S, Leiderman DB. Safety and health policy considerations related to the use of buprenorphine/naloxone as an office-based treatment for opiate dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003 May 21;70(2 Suppl):S79–85. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(03)00061-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Levit KR, Mark TL, Coffey RM, et al. Federal spending on behavioral health accelerated during recession as individuals lost employer insurance. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013 May;32(5):952–962. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levit KR, Stranges E, Coffey RM, et al. Current and future funding sources for specialty mental health and substance abuse treatment providers. Psychiatr Serv. 2013 Jun;64(6):512–519. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201200298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Volkow ND, Frieden TR, Hyde PS, Cha SS. Medication-assisted therapies--tackling the opioid-overdose epidemic. N Engl J Med. 2014 May 29;370(22):2063–2066. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1402780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Adelmann PK. Mental and substance use disorders among Medicaid recipients: prevalence estimates from two national surveys. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2003 Nov;31(2):111–129. doi: 10.1023/b:apih.0000003017.78877.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baxter JD, Clark RE, Samnaliev M, Leung GY, Hashemi L. Factors associated with Medicaid patients' access to buprenorphine treatment. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2011 Apr 2;41:88–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2011.02.002. Published Online. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Becker WC, Fiellin DA, Merrill JO, et al. Opioid use disorder in the United States: Insurance status and treatment access. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;94(1-3):207–213. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Deck D, Carlson M. Access to publicly funded methadone maintenance treatment in two western states. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2004;31(2):164. doi: 10.1007/BF02287379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Deck D, Wiitala W, Laws K. Medicaid Coverage and Access to Publicly Funded Opiate Treatment. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2006;33(3):324. doi: 10.1007/s11414-006-9018-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McCarty D, Frank RG, Denmead GC. Methadone Maintenance and State Medicaid Managed Care Programs. Milbank Q. 1999;77(3):341. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Knudsen HK, Abraham AJ. Perceptions of the state policy environment and adoption of medications in the treatment of substance use disorders. Psychiatr Serv. 2012 Jan;63(1):19–25. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201100034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rinaldo SG, Rinaldo DW. Advancing Access to Addiction Medications: Implications for Opioid Addiction Treatment. Chevy Chase, MD: American Society of Addiction Medicine, The Avisa Group; 2013. Availability without accessability? State Medicaid coverage and authorization requirements for opioid dependence medications: Implications for Opioid Addiction Treatment. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dick AW, Pacula RL, Gordon AJ, et al. Growth in Buprenorphine Waivers for Physicians Increased Potential Access to Opioid Agonist Treatment, 2002-11. Health Aff (Millwood) doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.1205. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gryczynski J, Schwartz RP, Salkever DS, Mitchell SG, Jaffe JH. Patterns in admission delays to outpatient methadone treatment in the United States. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2011 Dec;41(4):431–439. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2011.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Decker SL. In 2011 nearly one-third of physicians said they would not accept new Medicaid patients, but rising fees may help. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012 Aug;31(8):1673–1679. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Galanter M, Keller DS, Dermatis H, Egelko S. The impact of managed care on substance abuse treatment: a report of the American Society of Addiction Medicine. J Addict Dis. 2000;19(3):13–34. doi: 10.1300/J069v19n03_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Research and Policy Analysis Group of Carnevale Associates LLC. Information Brief--The Affordable Care Act: Shaping Substance Abuse Treatment. Gaithersburg, MD: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Boozang P, Bachrach D, Detty A. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. 2014. Coverage and Delivery of Adult Substance Abuse Services in Medicaid Managed Care. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Krupitsky E, Nunes EV, Ling W, Gastfriend DR, Memisoglu A, Silverman BL. Injectable extended-release naltrexone (XR-NTX) for opioid dependence: long-term safety and effectiveness. Addiction. 2013 Sep;108(9):1628–1637. doi: 10.1111/add.12208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Krupitsky E, Nunes EV, Ling W, Illeperuma A, Gastfriend DR, Silverman BL. Injectable extended-release naltrexone for opioid dependence. Lancet. 2011 Aug 20;378(9792):665. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61331-7. author reply 666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mattick RP, Kimber J, Breen C, Davoli M. Buprenorphine maintenance versus placebo or methadone maintenance for opioid dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(2) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002207.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.National Institute on Drug Abuse. Principles of Effective Treatment for Criminal Justice Populations. Rockville, MD: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schackman BR, Leff JA, Polsky D, Moore BA, Fiellin DA. Cost-effectiveness of long-term outpatient buprenorphine-naloxone treatment for opioid dependence in primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2012 Jun;27(6):669–676. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1962-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stein BD, Gordon AJ, Sorbero M, Dick AW, Schuster J, Farmer C. The impact of buprenorphine on treatment of opioid dependence in a Medicaid population: Recent service utilization trends in the use of buprenorphine and methadone. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012 Jun 1;123(1-3):72–78. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Office of National Drug Control Policy Reauthorization Act of 2006 (ONDCPRA) 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 49.Clark RE, Baxter JD, Barton BA, Aweh G, O'Connell E, Fisher WH. The Impact of Prior Authorization on Buprenorphine Dose, Relapse Rates, and Cost for Massachusetts Medicaid Beneficiaries with Opioid Dependence. Health Serv Res. 2014 Dec;49(6):1964–1979. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lovegrove MC, Mathew J, Hampp C, Governale L, Wysowski DK, Budnitz DS. Emergency hospitalizations for unsupervised prescription medication ingestions by young children. Pediatrics. 2014 Oct;134(4):e1009–1016. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-0840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kim HK, Smiddy M, Hoffman RS, Nelson LS. Buprenorphine may not be as safe as you think: a pediatric fatality from unintentional exposure. Pediatrics. 2012 Dec;130(6):e1700–1703. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Martin TC, Rocque MA. Accidental and non-accidental ingestion of methadone and buprenorphine in childhood: a single center experience, 1999-2009. Curr Drug Saf. 2011 Feb 1;6(1):12–16. doi: 10.2174/157488611794480034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pedapati EV, Bateman ST. Toddlers requiring pediatric intensive care unit admission following at-home exposure to buprenorphine/naloxone. Pediatric critical care medicine : a journal of the Society of Critical Care Medicine and the World Federation of Pediatric Intensive and Critical Care Societies. 2011 Mar;12(2):e102–107. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e3181f3a118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cicero TJ, Ellis MS, Surratt HL, Kurtz SP. Factors contributing to the rise of buprenorphine misuse: 2008-2013. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014 Sep 1;142:98–104. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Johanson CE, Arfken CL, di Menza S, Schuster CR. Diversion and abuse of buprenorphine: findings from national surveys of treatment patients and physicians. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012 Jan 1;120(1-3):190–195. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Daniulaityte R, Falck R, Carlson RG. Illicit use of buprenorphine in a community sample of young adult non-medical users of pharmaceutical opioids. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012 May 1;122(3):201–207. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lavonas EJ, Severtson SG, Martinez EM, et al. Abuse and diversion of buprenorphine sublingual tablets and film. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2014 Jul;47(1):27–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2014.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lu CY, Soumerai SB, Ross-Degnan D, Zhang F, Adams AS. Unintended impacts of a Medicaid prior authorization policy on access to medications for bipolar illness. Med Care. 2010 Jan;48(1):4–9. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181bd4c10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hartung DM, Carlson MJ, Kraemer DF, Haxby DG, Ketchum KL, Greenlick MR. Impact of a Medicaid copayment policy on prescription drug and health services utilization in a fee-for-service Medicaid population. Med Care. 2008 Jun;46(6):565–572. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181734a77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Buck JA. The looming expansion and transformation of public substance abuse treatment under the Affordable Care Act. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011 Aug;30(8):1402–1410. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Stein BD, Gordon AJ, Dick AW, et al. Supply of buprenorphine waivered physicians: the influence of state policies. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2015 Jan;48(1):104–111. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2014.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bauhoff S, Stein BD, Pacula RL, et al. Paper presented at: Presented at the Addiction Health Services Research Conference. Boston, MA: 2014. Do substance abuse policies influence opioid agonist therapies in substance abuse treatment facilities? [Google Scholar]

- 63.American Society of Addiction Medicine. State Medicaid Reports. [Accessed January 22, 2015]; http://www.asam.org/advocacy/aaam/state-medicaid-reports.