Abstract

Given the high rates of comorbidity between posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and substance use disorder (SUD), we investigated an integrated treatment for these disorders. Individuals with comorbid PTSD and alcohol dependence were randomized to receive naltrexone or placebo, with or without prolonged exposure (PE). All participants also received BRENDA (supportive counseling). The naltrexone plus PE group showed a greater decline in alcohol craving symptoms than those in the placebo with no PE group. The PE plus placebo and the naltrexone without PE groups did not differ significantly from the placebo with no PE group in terms of alcohol craving. No treatment group differences were found for percentage of drinking days. Alcohol craving was moderated by PTSD severity, with those with higher PTSD symptoms showing faster decreases in alcohol craving. Both PTSD and alcohol use had a lagged effect on alcohol craving, with changes in PTSD symptoms and percentage of days drinking being associated with subsequent changes in craving. These results support the relationship between greater PTSD symptoms leading to greater alcohol craving and suggest that reducing PTSD symptoms may be beneficial to reducing craving in those with co-occurring PTSD/SUD.

Keywords: PTSD, substance use disorder, alcohol dependence, prolonged exposure, naltrexone

The high prevalence of substance use disorders (SUD) in individuals with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD; Kessler, Chiu, Demler, & Walters, 2005; Reynolds et al., 2005) has resulted in considerable efforts to develop effective treatments for those with this comorbidity. The importance of such treatments is further supported by research showing that those with both PTSD and SUD are more likely to have poorer outcomes in substance use treatment and are at increased risk for substance-use relapse (Glasner-Edwards, Mooney, Ang, Hillhouse, & Rawson, 2013; Read, Brown, & Kahler, 2004; Resko & Mendoza, 2012).

There are a number of treatment models that have been examined for individuals with concurrent PTSD/SUD. Tested models for comorbid PTSD/SUD have resulted in a number of treatments including Concurrent Treatment of PTSD and Cocaine Dependence (CTPTCD, also called Concurrent Prolonged Exposure (COPE); Back et al., 2014), Creating Change (CC; Najavits, 2014), Helping Women Recover/Beyond Trauma (HWR/BT; Covington, 2003; 2008), Integrated CBT for PTSD and SUD (ICBT; McGovern et al., 2009), Substance Dependence PTSD Therapy (SDPT; Triffleman, 1997; Triffleman, Carroll, & Kellogg, 1999), Seeking Safety (SS; Najavits, Weiss, & Liese, 1996), Trauma Adaptive Recovery Group Education and Therapy (TARGET; Ford & Russo, 2006), and Trauma Recovery Empowerment Model (TREM; Harris, 1998). In general, these treatments show positive outcomes in improving patients’ PTSD symptoms and/or other symptom areas. Specifically, treatments such as ICBT, TREM, and COPE showed greater improvements in PTSD symptoms compared to control conditions (Hien et al., 2015; Najavits & Hien, 2013). The results of the efficacy of SS are mixed with one study finding no differences between SS and an active comparison health education group in terms of PTSD symptom reductions or substance use outcomes (Hien et al., 2009). Furthermore, models focusing on SUD symptoms only and not specifically targeting PTSD symptoms (e.g., relapse prevention therapy) have also been shown to significantly improve PTSD symptoms (Hien, Cohen, Miele, Litt, & Capstick, 2004).

In addition, prolonged exposure (PE) has been proposed to treat those with comorbid PTSD/SUD problems. Historically, studies on PE have excluded those with SUD. Although PE was not designed to target substance use symptoms directly, it has been proposed that reducing PTSD symptoms with PE may lead to less reliance on substance use as a coping mechanism. PE has been shown in a meta-analysis to be effective in reducing PTSD symptoms compared to either psychological placebo (e.g., supportive counseling, relaxation, Present Centered Therapy, Time Limited Psychodynamic Therapy, or treatment as usual) or waitlist control (Powers, Halpern, Ferenschak, Gillihan, & Foa, 2010). However, PE was not found to be more effective than other active treatments including Cognitive Processing Therapy, Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing, Cognitive Therapy, and Stress Inoculation Training (Powers et al., 2010). Overall there has been less research on the efficacy of exposure-based therapies in those with PTSD/SUD compared to other treatments, such as SS.

Of the randomized controlled trials investigating exposure techniques in concurrent PTSD/SUD populations, a study by Coffey, Stasiewicz, Hughes, and Brimo (2006) randomly assigned alcohol dependent patients to either trauma-focused imaginal exposure or imagery-based relaxation for 6 weeks. All participants were required to have four days of abstinence prior to starting the study. They also participated in group treatment for SUD symptoms three times per week and individual coping-skills-based SUD therapy once every 1 or 2 weeks. The authors found a reduction in PTSD symptoms and alcohol craving in the imaginal exposure group and no significant change in the relaxation group. The finding of reduced PTSD symptoms was no longer significant when the analyses were restricted to those who showed a craving response (Coffey et al., 2006). Yet, the finding of reduced alcohol craving following imaginal exposure compared to relaxation suggests that adding exposure-based PTSD treatment to concurrent SUD treatment may have some benefit for reducing alcohol craving symptoms in those with comorbid PTSD/SUD. Unfortunately, this study did not assess substance use behaviors following treatment, which would have allowed for comparison of substance use outcomes between the treatment groups. Furthermore, the exposure condition in this study included a combination of exposure and coping skills therapy, with a higher dose of the latter.

A study by Mills et al. (2012) randomized participants to either COPE plus treatment as usual (TAU) or TAU alone. The results showed no differences between the two groups at the end of treatment, but found significantly greater reduction in PTSD symptoms in the COPE plus TAU group at 9 months follow-up compared to TAU alone (Mills et al., 2012). Although substance use severity and number of drug classes used decreased for both groups after 9 months, COPE plus TAU did not perform better on these substance use measures than TAU alone (Mills et al., 2012). Of note, COPE included multiple treatment techniques besides exposure (e.g., motivational enhancement, CBT for substance use, and cognitive therapy for PTSD), making the relative contributions of each treatment component difficult to disentangle.

A study by Foa et al. (2013), which serves as the basis for the current study, randomly assigned participants with comorbid PTSD and alcohol dependence to either PE plus naltrexone, PE plus pill placebo, naltrexone without PE, or pill placebo without PE. All groups also received manualized supportive counseling (the BRENDA model of substance use treatment). All four treatment groups showed a reduction in percentage of days drinking but the two groups receiving naltrexone showed significantly lower percentage of drink days than the other groups (Foa et al., 2013). PTSD symptoms also decreased in all four groups, but PE did not perform better than BRENDA during active treatment (Foa et al., 2013). At the six-month follow-up, all four groups showed an increase in percentage of days drinking but this increase was only significant in those not receiving PE (Foa et al., 2013). This study did not report on moderators of alcohol-related outcomes or on the lagged effects of percentage of days drinking and PTSD symptom severity on alcohol craving. PTSD symptoms have been proposed to lead some individuals to use substances to temporarily alleviate or mask the distress related to their symptoms (Jacobsen, Southwick, & Kosten, 2001; Norman, Tate, Anderson, & Brown, 2007). It is possible that PTSD severity may be a moderator of the change in alcohol craving or percentage of days drinking over time. Furthermore, changes in alcohol use or PTSD may influence subsequent changes in alcohol craving (lagged effects), which was not assessed in the Foa et al. (2013) study. Previous work has shown that reductions in PTSD severity were associated with substance use improvement but only minimal evidence was found that reductions in substance use symptoms improved PTSD symptoms (Hien et al., 2010).

Therefore, the purpose of this study was to investigate the theory postulating that increased PTSD symptom severity leads patients to have increased craving which, in turn, is expected to lead to increased drinking. We were also interested in examining treatment-related differences in these symptoms. First, this study investigated treatment differences in drinking and alcohol craving in a sample of patients with comorbid PTSD and alcohol dependence. We hypothesized that reductions in percentage of days drinking and alcohol craving over time would be strongest in those receiving combined naltrexone and PE therapy compared to the PE alone, naltrexone alone, and placebo groups. Second, we predicted that change in drinking and alcohol craving over time would depend on the level of PTSD symptoms (e.g., less PTSD, less drinking and craving). Specifically, we hypothesized that reductions in percentage of days drinking and alcohol craving would be moderated by PTSD symptom severity, such that greater reductions in alcohol outcomes would be observed in those with greater PTSD symptom severity. And lastly, this study tested the hypothesis that changes in percentage of days drinking and PTSD symptom severity would have a lagged effect on alcohol craving, i.e. that changes in alcohol use and PTSD would influence subsequent changes in craving. Additionally, an exploratory analysis was used to determine whether this lagged effect was apparent in the early phase of treatment, but not later in treatment, since one might expect that there would be the greatest reduction in symptoms early in treatment.

Methods

Participants

Participants included 165 individuals (65.5% male) seeking treatment for concurrent PTSD and alcohol dependence, recruited from the University of Pennsylvania's Center for the Treatment and Study of Anxiety and the Philadelphia Veteran's Affairs Hospital. The design, treatments, and measures used in this randomized controlled trial have been described elsewhere (Foa et al., 2013). Briefly, inclusion criteria included: 1) current diagnoses of PTSD and alcohol dependence (DSM-IV-TR criteria; American Psychiatric Association, 2000); 2) a score of 15 or more on the PTSD Symptom Severity Interview (PSS-I; Foa, Riggs, Dancu, & Rothbaum, 1993); and 3) endorsement of consuming more than 12 alcoholic drinks per week in the past month with at least 4 or more drinks consumed in one day. Participants were excluded if they 1) met criteria for other current substance dependence besides nicotine or cannabis; 2) met criteria for a current psychotic disorder; 3) endorsed clinically significant suicidal or homicidal ideation; 4) endorsed opiate use in the past month; 5) reported medical illnesses that could interfere with treatment (e.g., AIDS, active hepatitis); or 6) were pregnant or nursing. For a detailed description of the participant demographics, please see Foa et al. (2013).

Procedure

This study received approval from the University of Pennsylvania and the VA institutional review boards. As described in greater detail elsewhere (Foa et al., 2013; Foa & Williams, 2010), procedures included an intake assessment, baseline evaluation, randomization to one of four treatment conditions (naltrexone vs. placebo and PE vs. no PE; see treatments section below), and evaluations every four weeks during treatment, at post-treatment (week 24), and at follow-up (weeks 38 and 52). Evaluations were administered by evaluators who were blind to treatment group assignment. Participants were required to be abstinent from alcohol for at least three consecutive days before beginning treatment as measured by self-report and breathalyzer testing. Detoxification was monitored in an outpatient medical setting and symptoms of alcohol withdrawal were managed with oxazepam.

Measures

The PTSD Symptom Severity Interview (PSS-I) is a 17-item clinical interview that measures PTSD symptoms according to the DSM-IV-TR (Foa et al., 1993). Scores range from 0 to 51 with higher scores indicating more severe PTSD symptoms. This measure shows excellent psychometric properties and has been shown to be highly correlated with depression and anxiety and to be sensitive to treatment effects. (Foa et al., 2005; Foa & Tolin, 2000; Powers, Gillihan, Rosenfield, Jerud, & Foa, 2012).

The Timeline Follow-Back Interview (TLFB; Sobell & Sobell, 1995) is a semi-structured interview that measures participants’ self-reported daily alcohol use. Both frequency (days) and quantity (number of drinks) are collected. This measure was used to calculate the percentage of days where participants consumed alcohol. The TLFB has been shown to have good psychometric properties (Maisto, Sobell, & Sobell, 1982; Sobell, Maisto, Sobell, & Cooper, 1979).

The Penn Alcohol Craving Scale (PACS; Flannery, Volpicelli, & Pettinati, 1999) is a five-item self-report measure of the frequency, duration, and intensity of urges to consume alcohol. Additionally, it measures difficulty in resisting drinking. Higher scores indicate greater craving. This measure has been shown to have adequate psychometric properties including excellent reliability and good concurrent validity (Flannery, Volpicelli, & Pettinati, 1999; Modell, Glaser, Mountz, Cyr, & Schmaltz, 1992).

Treatments

The four treatment conditions included naltrexone with PE (NAL+PE), placebo with PE (PLA+PE), naltrexone with no PE (NAL+NoPE), and placebo with no PE (PLA+NoPE). Naltrexone, an opiate antagonist, has been approved for the treatment of alcohol dependence by the US Food and Drug Administration (Kranzler, & Van Kirk, 2001). For more details on the titration schedule for naltrexone, please refer to Foa et al. (2013). PE involved 18 sessions total: 12 weekly 90-minute sessions which were followed by six sessions occurring every other week. For a detailed explanation of the protocol for PE, see Foa, Hembree, and Rothbaum (2007). All participants also received up to 18 30- to 45-minute sessions of supportive counseling using the BRENDA model which focused on medication management using motivational interviewing techniques (Starosta, Leeman, & Volpicelli, 2006; Miller & Rollnick, 1991). BRENDA visits occurred weekly for the first three months of treatment and then every other week after. Treatment dropouts prior to the end of the treatment phase included 53 participants (32.1%). Treatment groups did not differ significantly in terms of the number of dropouts (χ23 = 1.55; p = .67). Due to adverse events unrelated to the study, 12 participants were removed from participating (7 for serious suicidal ideation, 3 for serious medical problems, 1 for psychotic symptoms, and 1 for unrelated death). Of the total participants, 85% were considered adherent to medication and BRENDA, which was defined as 80% adherence to medication and attendance to BRENDA sessions. In terms of attendance, participants completed an average of 12.09 BRENDA sessions. Of those who participated in PE, participants completed an average of 6.33 exposure sessions. Participants on average completed a significantly greater number of BRENDA sessions than PE sessions (t(79) = 10.51, p < .001). No difference was found in number of completed sessions between the NAL+PE and PLA+PE groups (p = .73). Use of non-study treatments (e.g., individual treatment, group treatment, self-help, detox, rehabilitation) was endorsed by 37% of participants during active treatment and by 17% during follow-up. The amount of time spent in non-study treatments did not significantly differ between the treatment groups during either active treatment (p = .34) or follow-up (p = .67).

Data Analysis

Multilevel modeling was used to specify growth models that investigated the change in percentage of drinking days and alcohol craving over the course of treatment. First, we analyzed unconditional growth curve models separately for each of the variables of interest (PSS-I, percentage of days drinking, and alcohol craving). This involves examining individual variation in change rates over time in order to determine the best fitting shape of the growth trajectories for each variable. Akaike's Information Criterion (AIC) and Schwarz's Bayesian Criterion (BIC) were used to compare models, with smaller values indicating a better model fit (Heck, Thomas, & Tabata, 2014). The variance for percentage of drinking days was higher than its respective mean, suggesting that over-dispersion was present due to a large number of zeros in the data indicating high levels of abstinence. Therefore, a negative binomial model was used to model percentage of drinking days. Following the methods of Worely et al. (2008), partial correlations were used to examine the relationship between non-study treatments received and the study outcomes (alcohol craving, percentage of drink days, PSS-I) during active treatment and follow-up while controlling for baseline measures of non-study treatment services received, baseline scores on the relevant outcome measure, and treatment condition.

Multilevel modeling was used to model changes over time in percentage of days drinking and alcohol craving with treatment condition introduced to determine whether change over time in these measures depended on treatment type (NAL+PE, PLA+PE, NAL+NoPE, or PLA+NoPE). All treatment contrasts were analyzed, with each of the active treatment groups as the comparison group in contrast with the placebo. Additionally, baseline PSS-I was introduced as a moderator to examine whether PTSD symptom severity moderated changes in alcohol use and craving. Lastly, we tested the hypothesis that change in drinking and PSS-I would have a lagged effect on alcohol craving, with exploration of whether this lagged effect occurred in the early phase of treatment but not later in treatment. Alcohol craving was lagged by one time point to test whether change in percentage of days drinking or PSS-I at time t was associated with change in alcohol craving at time t + 1. An autoregressive model was used to account for the autoregressive effects of alcohol craving in order to provide information about the unique effects of PTSD symptoms on changes in alcohol use throughout treatment. Autoregressive models are advantageous because they specify that alcohol craving depends on its own previous values. Data analyses were conducted using the generalized linear mixed models routine of the IBM SPSS Statistics program (version 22) using the procedures outlined in Heck, Thomas, and Tabata (2012) and Shek and Ma (2011). To test whether missing data was missing completely at random (MCAR), we used Little's MCAR test (Little, 1988) implemented with SPSS's missing values analysis procedure. The results were not significant for the variables (p-values ≥ .297); therefore, we concluded that our data does not violate the missing completely at random assumption. All analyses were conducted with the intent-to-treat sample since multilevel modeling is robust to missing data due to dropout and does not exclude such data (DeSouza, Legedza, & Sankoh, 2009).

Results

Correlations among study variables

At baseline, participants with greater levels of PTSD symptom severity endorsed significantly greater percentage of days drinking and alcohol craving as shown by positive correlations between the PSS-I and percentage of days drinking (r = .29, p < .001) and alcohol craving (r = .51, p < .001). As expected, percentage of days drinking was positively correlated with alcohol craving (r = .45, p < .001). Means and standard deviations for the PSS-I, percentage of days drinking, and alcohol craving for each of the measurement time points are presented in Table 1. Non-study treatments received were not found to be related to treatment outcomes (PTSD, alcohol craving, or percentage of drink days) for either active treatment or follow-up (p-values ≥ .37). For growth curve model fitting, see the supplementary methods section.

Table 1.

Means and Standard Deviations of Variables by Time

| PSS-I |

Percent Drink Days |

Alcohol Craving |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time point | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD |

| Week 0 (pre-tx) | 28.14 | 7.86 | 74.83 | 25.26 | 18.38 | 6.91 |

| Week 4 | 22.62 | 9.22 | 19.81 | 25.79 | 13.30 | 7.52 |

| Week 8 | 19.53 | 10.52 | 13.60 | 21.57 | 11.66 | 7.94 |

| Week 12 (mid-tx) | 17.05 | 10.96 | 11.24 | 19.39 | 10.30 | 7.48 |

| Week 16 | 15.53 | 10.63 | 10.41 | 18.46 | 9.37 | 7.21 |

| Week 20 | 15.28 | 10.57 | 10.53 | 17.69 | 8.01 | 6.31 |

| Week 24 (post-tx) | 12.31 | 10.56 | 11.20 | 18.39 | 7.72 | 7.08 |

| Week 38 (follow-up) | 11.65 | 9.84 | 17.46 | 27.58 | 7.51 | 6.46 |

| Week 52 (follow-up) | 9.88 | 10.40 | 17.10 | 28.67 | 7.00 | 6.60 |

Note. PSS-I = PTSD Symptoms Scale-Interview; tx = treatment

Treatment condition differences in the change in alcohol craving and percentage of days drinking over time

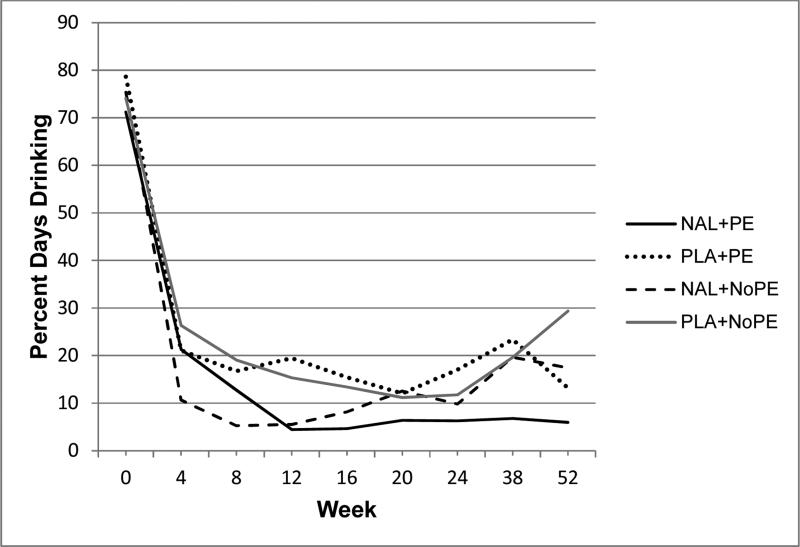

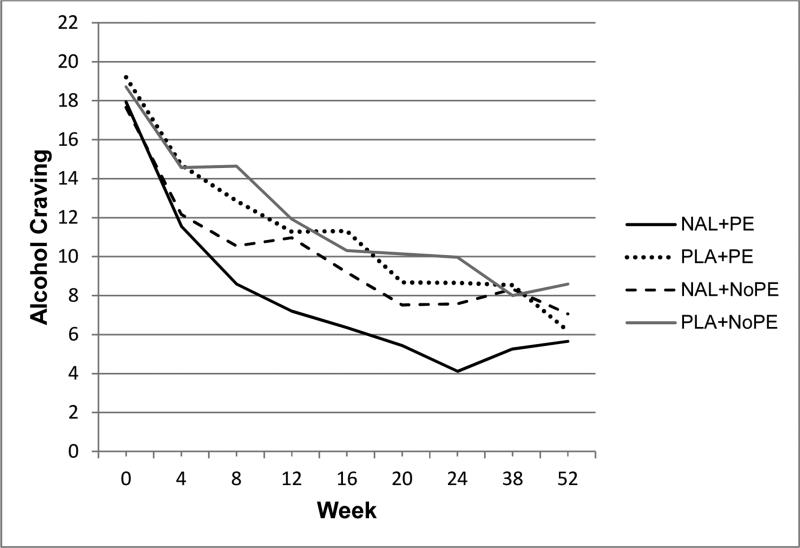

We examined the extent to which changes in percentage of days drinking and alcohol craving could be explained by treatment condition. For alcohol craving, model fit indices indicated that the addition of treatment condition to the model significantly improved the model's fit compared to the unconditional model with time only (χ2(9) = 55.50, p < .001). Results showed that reduction in alcohol craving over time differed based on treatment group. Specifically, those in the NAL+PE group showed a greater decline in alcohol craving symptoms over time than those in the PLA+NoPE group (B = −3.79, t(1,006) = −2.03, p = .042). No other treatment group comparisons were significant for alcohol craving (p-values ≥ .076). Change over time in percentage of days drinking did not differ between treatment groups (p ≥ .152) and model fit indices confirmed that the unconditional model with only time as a predictor fit better than the model that added treatment group as an additional predictor (χ2(9) = 41.79, p < .001).

PTSD symptom severity as a moderator of changes in alcohol craving and percentage of days drinking over time

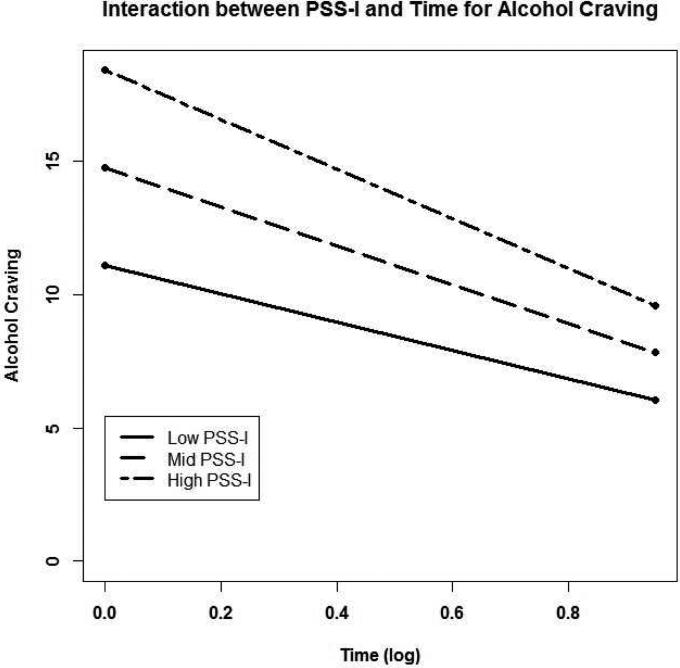

Model fit indices indicated that the addition of a time by PSS-I interaction to the alcohol craving model significantly improved the model's fit to the data over the model with time only (χ2(3) = 576.33, p < .001). Results showed that change in alcohol craving differed based on the level of PTSD symptom severity. Specifically, decrease in alcohol craving depended on the level of PSS-I, with those with higher PSS-I scores showing faster decreases in alcohol craving over time (B = −.17, t(939) = −3.11, p = .002; see figure 4). We also tested whether this significant time by PSS-I interaction for alcohol craving differed by treatment group using a three-way interaction (time by PSS-I by treatment group); however, the results were not significant (p = .107). Although model fit for percentage of days drinking was improved by the addition of the PSS-I as a potential moderator (χ2(3) = 239.23, p < .001), no significant interaction was found for time by PSS-I with percentage of drink days as the outcome (p = .354).

Figure 4.

Interaction between PSS-I scores (high, mid, and low) and time (log transformed) for alcohol craving. High and low values represent +1 and−1 standard deviations from the raw mean PSS-I score (mid).

Lagged effects on alcohol craving

In addition, we examined whether change in percentage of days drinking or change in PSS-I had a lagged effect on alcohol craving, with this effect being apparent in the early phase of treatment but not later on in treatment. Alcohol craving was lagged by one time point. The results indicated that percentage of days drinking at time t was associated with alcohol craving at time t + 1 (B = .022, t(856) = 2.80, p = .005) and this relationship remained significant regardless of whether patients were in the early (weeks 0-12; B = .029, t(468) = 2.74, p = .006) or late phases of treatment (weeks 13-24; B = .115, t(305) = 5.27, p < .001). PSS-I scores at time t were also associated with alcohol craving at time t + 1, even when controlling for percentage of days drinking (B = .066, t(782) = 2.62, p = .009), and this was also apparent during both the early (B = .080, t(426) = 2.29, p = .023) and late phases of treatment (B = .095, t(269) = 2.54, p = .012).

Exploratory analyses

Finally, we conducted exploratory analyses to determine whether PTSD symptom severity over time depended on the percentage of days drinking. The results indicated that the time by percentage of days drinking interaction did not reach significance for PTSD symptom severity (p = .087). This suggests that severity of PTSD symptoms was not affected by the amount of alcohol the patient consumes in the current sample.

Discussion

The results of this study found that the naltrexone plus PE group showed a greater decline in alcohol craving symptoms over time than those in the placebo with no PE group. The PE plus placebo and the naltrexone without PE groups did not differ significantly from the placebo/no PE group in terms of change over time in alcohol craving. The lack of a difference between the naltrexone only group and the placebo/no PE group is in contrast to a meta-analysis of previous randomized controlled trials testing naltrexone in patients with alcohol use disorders that showed naltrexone reduced alcohol craving to a greater extent than placebo during the treatment phase but not during follow-up (Bouza, Angeles, Muñoz, & Amate, 2004). In addition, the finding of similar reductions in alcohol craving in the PE only group compared to the placebo/no PE group was not expected. However, individuals who participated in treatment involving both naltrexone and PE showed better outcomes in terms of alcohol craving suggesting that the combination of these two treatments had a stronger effect than PE alone or naltrexone alone. Additionally, contrary to our prediction, change in percentage of days drinking did not differ by treatment group. As noted in the methods, percentage of days drinking showed high levels of abstinence across all treatment groups. Therefore, either there may not have been enough variability in this alcohol use measure to find group differences, or indeed, all treatment groups may have been effective in improving this outcome. However, this is speculative since no equivalence analyses were done.

In terms of the lack of group differences found in this study, it is important to note that the BRENDA treatment, which was delivered to all four treatment groups, may have positively influenced alcohol use, alcohol craving, and PTSD outcomes regardless of treatment condition. If BRENDA significantly reduced alcohol craving, then we might not find that the addition of naltrexone alone or PE alone would produce greater reductions. However, we did not directly test BRENDA against a waitlist or other type of control group which precludes us from drawing conclusions about the effects of BRENDA. Also of note, participants on average completed a significantly greater number of BRENDA sessions than PE sessions. The greater treatment attendance to BRENDA than PE may suggest that the participants in this study found the 30- to 45-minute BRENDA sessions less burdensome than the 90-minute PE sessions in terms of time commitment or other factors such as emotional investment. It is not unexpected that PE might be perceived as emotionally challenging for PTSD patients, thus influencing treatment attendance, since PE involves revisiting traumatic memories in detail and a core symptom of PTSD is the avoidance of memories related to the trauma.

Additionally, changes over time in alcohol craving were found to be moderated by PTSD symptom severity. Consistent with previous studies, participants with higher PTSD symptom scores in the current study were more likely to endorse greater alcohol craving (Brady et al., 2006; Simpson, Stappenbeck, Varra, Moore, & Kaysen, 2012). Also, those with higher levels of PTSD symptoms showed greater decreases in alcohol craving over time, consistent with the notion that those with higher symptoms have more room for improvement. Furthermore, the moderating effect of PTSD symptoms was shown to impact changes in alcohol use/craving beyond baseline levels of use/craving, with effects demonstrated throughout posttreatment and follow-up. In addition, this study found that both PTSD symptom severity and percentage of days drinking had a lagged effect on alcohol craving, with alcohol craving being dependent on the amount of PTSD symptoms and alcohol use reported at the previous time point. Furthermore, this relationship remained significant regardless of whether patients were in the early or late phases of treatment. The lagged effect of percentage of days drinking is consistent with the expectation that alcohol craving will decrease with longer periods of abstinence. The finding that reduction in PTSD symptom severity at time t was associated with alcohol craving at time t + 1, even when controlling for reductions in percentage of days drinking, may lend support to the theory that PTSD symptoms may influence alcohol craving.

In terms of the broader literature on treatment for comorbid PTSD and substance use, the results of this study are consistent with the findings by Coffey et al. (2006) who showed a reduction in PTSD symptoms and alcohol craving over time during imaginal exposure but not during imagery-based relaxation. However, the analyses in the Coffey et al. (2006) study were based on completers only and the experimental paradigm did not include a follow-up period. The current study showed greater decreases in alcohol craving in those receiving naltrexone plus PE compared to those receiving placebo/no PE, using all study participants (completers and dropouts) and up to one year follow-up assessments. However, the present study was not able to demonstrate significant treatment group differences for alcohol use. Previous work found that other treatments such as SS and TAU both reduce alcohol use but SS showed a greater reduction in drug use outcomes than TAU (Boden et al., 2012). Other studies demonstrated that treatment modalities such as SS and TREM showed greater substance use reduction compared to a control group. For example, Hien et al. (2004) found that both SS and relapse prevention therapy resulted in significant reductions in substance use compared to standard community treatment. Additionally, Hien et al. (2015) reported that SS, combined with either sertraline or placebo, showed significant reductions in alcohol symptoms at the end of treatment, which was sustained through 12-months follow-up. Furthermore, TREM has been shown to significantly reduce alcohol and drug abuse severity but not PTSD symptoms compared to TAU (Fallot, McHugo, Harris, & Xie, 2011).

These results expand on the Foa et al. (2013) study and previous studies in several ways. First, this study builds on previous research by using multilevel modeling to examine two outcome measures (alcohol craving and percentage of days drinking) in order to test treatment condition and PTSD symptom severity as potential moderators of the reductions in alcohol use and craving. Furthermore, this study used a lagged time model to more clearly show the effect of reductions in PTSD symptoms and percentage of days drinking on alcohol craving. In addition, this randomized controlled trial, conducted within the context of a clinical, comorbid sample with fairly extensive follow-up periods and multiple assessment time points provides unique and valuable insight into how these constructs impact one another over the course of different treatments.

However, it is important to note that focusing on alcohol craving is not equivalent to focusing on alcohol use, as cravings are more subjective and possibly easier to change than use. Additionally, we did not administer an objective measure of alcohol use (e.g., breathalyzer) at each of the time points, which would be important for future studies to ensure. Similarly, while our measure of self-reported alcohol craving has been widely used (e.g., Brown, Garza, & Carmody, 2008; Chakravorty et al., 2014; Morley et al., 2006; Zilberman, Tavares, & el-Guebaly, 2003), it would have been useful to examine a biological measure of this construct such as imagery or a computerized paradigm that induces craving while measuring objective psychophysiological indices such as heart rate and skin conductance (Higley et al., 2011; Kwako et al., 2015; Sinha et al., 2009).

A limiting factor in the present study was the more restricted number of time points in the follow-up phase (only two, compared to seven in the active phase of treatment). While it would have been ideal to have the same four-week assessments during follow-up, this was not feasible and would have been burdensome for participants. Despite this, having a follow-up period that extends to one year post-treatment is an inherent strength of this study in comparison to other such examinations of these constructs (e.g., Nosen, Littlefield, Schumacher, Stasiewicz, & Coffey, 2014; Petrakis, Poling, et al., 2006; Petrakis, Ralevski, et al., 2012). Additionally, we utilized an interviewer-administered measure of PTSD (the PSS-I), a more comprehensive measure of PTSD compared to previous studies relying on self-report of PTSD symptoms (Freeman & Kimbrell, 2004; Kaysen et al., 2014; Simpson et al., 2012). Finally, the generalizability of this study may be limited by the study's exclusionary criteria (e.g., excluding any primary substance dependence other than alcohol; not allowing for opiate use in the prior month; and requiring 3 days abstinence from alcohol), which may have potentially made the sample easier to treat than other PTSD/SUD samples. It is also important to note that although we tested and concluded that missing data in the current study was missing completely at random, in any randomized controlled trial it is possible that data may be missing not at random, which is a limitation to treatment studies with patient dropout.

In terms of future directions, it would be beneficial to investigate dual treatment of PTSD and other SUDs. The current study used a population with alcohol dependence, but it is important to examine combined treatments in those with other comorbid SUDs such as cocaine or opiate dependence and PTSD (Mills, Teesson, Ross, Darke, & Shanahan, 2005). While there may be additional difficulties associated with combined treatment in other SUD populations, such additional research would provide important information about how the current results and interventions used in the present study generalize to improvement in SUD symptoms overall. Lastly, although the current study examined levels of PTSD at time t on alcohol at t + 1, this study did not measure the effects of intraindividual changes in PTSD on subsequent intrandividual changes in alcohol use. Future studies would benefit from using latent growth curve models to investigate the temporal effects of change in PTSD on subsequent change in alcohol use and craving.

Supplementary Material

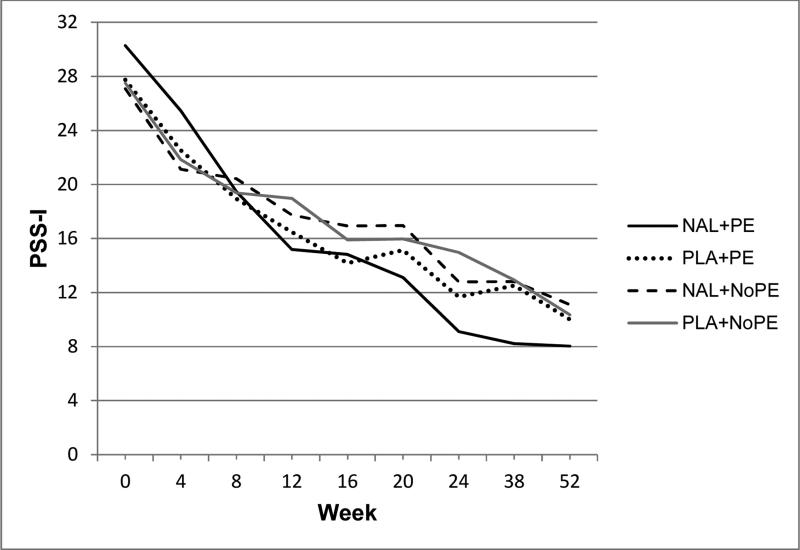

Figure 1.

Raw mean PSS-I (PTSD Symptom Severity Interview) scores during treatment (weeks 1-24) and follow-up (weeks 38 and 52). Treatment conditions: naltrexone with PE (NAL+PE), placebo with PE (PLA+PE), naltrexone with no PE (NAL+NoPE), and placebo with no PE (PLA+NoPE). All participants also received BRENDA (supportive counseling).

Figure 2.

Raw mean percentage of days drinking during treatment (weeks 1-24) and follow-up (weeks 38 and 52). Treatment conditions: naltrexone with PE (NAL+PE), placebo with PE (PLA+PE), naltrexone with no PE (NAL+NoPE), and placebo with no PE (PLA+NoPE). All participants also received BRENDA (supportive counseling).

Figure 3.

Raw mean alcohol craving scores during treatment (weeks 1-24) and follow-up (weeks 38 and 52). Treatment conditions: naltrexone with PE (NAL+PE), placebo with PE (PLA+PE), naltrexone with no PE (NAL+NoPE), and placebo with no PE (PLA+NoPE). All participants also received BRENDA (supportive counseling).

Secondary analysis of alcohol/PTSD treatment included naltrexone or placebo, with or without PE.

All participants also received BRENDA (supportive counseling).

Naltrexone+PE showed a faster decline in alcohol craving compared to Placebo+NoPE.

PTSD moderated alcohol craving and both PTSD and alcohol use had a lagged effect on alcohol craving.

These results suggest that reducing PTSD symptoms may be beneficial to reducing alcohol craving.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by a grant from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA). Trial registration: clinicaltrials.gov, identifier: NCT00006489.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed., text rev. Author; Washington, DC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Back SE, Foa EB, Killeen TK, Mills KL, Teesson M, Carroll KM, Brady KT. Concurrent Treatment of PTSD and SUDs Using Prolonged Exposure (COPE): Therapist Guide. Oxford University Press; New York, NY: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Boden MT, Kimerling R, Jacobs-Lentz J, Bowman D, Weaver C, Carney D, Trafton DA. Seeking Safety treatment for male veterans with a substance use disorder and PTSD symptomatology. Addiction. 2012;107:578–586. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03658.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouza C, Angeles M, Muñoz A, Amate JM. Efficacy and safety of naltrexone and acamprosate in the treatment of alcohol dependence: a systematic review. Addiction. 2004;99(7):811–828. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00763.x. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00763.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady KT, Back SE, Waldrop AE, McRae AL, Anton RF, Upadhyaya HP, Randall PK. Cold pressor task reactivity: Predictors of alcohol use among alcohol-dependent individuals with and without comorbid posttraumatic stress disorder. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2006;30(6):938–946. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00097.x. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00097.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown ES, Garza M, Carmody TJ. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled add-on trial of quetiapine in outpatients with bipolar disorder and alcohol use disorders. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2008;69(5):701–705. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n0502. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.4088/JCP.v69n0502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakravorty S, Hanlon AL, Kuna ST, Ross RJ, Kampman KM, Witte LM, Oslin DW. The effects of quetiapine on sleep in recovering alcohol-dependent subjects: A pilot study. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2014;34(3):350–354. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0000000000000130. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/JCP.0000000000000130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffey SF, Stasiewicz PR, Hughes PM, Brimo ML. Trauma-focused imaginal exposure for individuals with comorbid posttraumatic stress disorder and alcohol dependence: revealing mechanisms of alcohol craving in a cue reactivity paradigm. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2006;20:425–435. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.20.4.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covington S. Beyond Trauma: A healing journey for women. Facilitator's guide. Hazelden Press; Center City, MN: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Covington S. Facilitator's guide—Revised edition for use in the criminal justice system. Jossey-Bass Publishers; San Francisco, CA: 2008. Helping Women Recover: A program for treating substance abuse. [Google Scholar]

- DeSouza CM, Legedza AR, Sankoh AJ. An Overview of Practical Approaches for Handling Missing Data in Clinical Trials. Journal of Biopharmaceutical Statistics. 2009;19(6):1055–1073. doi: 10.1080/10543400903242795. doi:10.1080/10543400903242795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallot RD, McHugo GJ, Harris M, Xie H. The Trauma Recovery and Empowerment Model: A quasi-experimental effectiveness study. Journal of Dual Diagnosis. 2011;7:74–89. doi: 10.1080/15504263.2011.566056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flannery BA, Volpicelli JR, Pettinati HM. Psychometric properties of the Penn Alcohol Craving Scale. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1999;23(8):1289–1295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Hembree EA, Cahill SP, Rauch SAM, Riggs DS, Feeny NC, Yadin E. Randomized trial of prolonged exposure for posttraumatic stress disorder with and without cognitive restructuring: Outcome at academic and community clinics. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:953–964. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.5.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Hembree EA, Rothbaum BO. Prolonged exposure therapy for PTSD: Emotional processing of traumatic experiences. Oxford University Press, Inc.; New York, NY: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Riggs DS, Dancu CV, Rothbaum BO. Reliability and validity of a brief instrument for assessing post-traumatic stress disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1993;6:459–473. [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Tolin DF. Comparison of the PTSD Symptom Scale–Interview Version and the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2000;13:181–191. doi: 10.1023/A:1007781909213. doi:10.1023/A:1007781909213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Williams MT. Methodology of a randomized double-blind clinical trial for comorbid posttraumatic stress disorder and alcohol dependence. Mental Health and Substance Use. 2010;3:131–147. doi: 10.1080/17523281003738661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Yusko DA, McLean CP, Suvak MK, Bux DA, Oslin D, Volpicelli J. Concurrent naltrexone and prolonged exposure therapy for patients with comorbid alcohol dependence and PTSD: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association. 2013;310(5):488–495. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.8268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford JD, Russo E. Trauma-focused, present-centered, emotional self-regulation approach to integrated treatment for posttraumatic stress and addiction: Trauma Adaptive Recovery Group Education and Therapy (TARGET). American Journal of Psychotherapy. 2006;60:335–355. doi: 10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.2006.60.4.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman T, Kimbrell T. Relationship of alcohol craving to symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder in combat veterans. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2004;192(5):389–390. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000126735.46296.a4. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.nmd.0000126735.46296.a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasner-Edwards S, Mooney LJ, Ang A, Hillhouse M, Rawson R. Does posttraumatic stress disorder affect post-treatment methamphetamine use? Journal of Dual Diagnosis. 2013;9(2):123–128. doi: 10.1080/15504263.2013.779157. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15504263.2013.779157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris M. Trauma Recovery and Empowerment: A Clinician's Guide for Working with Women in Groups. The Free Press; New York, NY: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Heck RH, Thomas SL, Tabata LN. Multilevel Modeling of Categorical Outcomes Using IBM SPSS. Routledge; New York, NY: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Heck RH, Thomas SL, Tabata LN. Multilevel and longitudinal modeling with IBM SPSS. 2nd ed. Routledge; New York, NY: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hien DA, Cohen LR, Miele GM, Litt LC, Capstick C. Promising treatments for women with comorbid PTSD and SUDs. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;16:1426–1432. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.8.1426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hien DA, Jiang H, Campbell ANC, Hu M-C, Miele GM, Cohen LR, Nunes EV. Do treatment improvements in PTSD severity affect substance use outcomes? A secondary analysis from a randomized clinical trial in NIDA's Clinical Trials Network. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;167(1):95–101. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09091261. http://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09091261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hien D, Levin FR, Ruglass L, López-Castro T, Papini S, Hu MC, Herron A. Combining Seeking Safety with Sertraline for PTSD and Alcohol Use Disorders: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2015;83(2):359–369. doi: 10.1037/a0038719. http://doi.org/10.1037/a0038719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hien DA, Wells EA, Jiang H, Suarez-Morales L, Campbell ANC, Cohen LR, Nunes EV. Multi-site randomized trial of behavioral interventions for women with co-occurring PTSD and substance use disorders. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77(4):607–619. doi: 10.1037/a0016227. http://doi.org/10.1037/a0016227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higley AE, Crane NA, Spadoni AD, Quello SB, Goodell V, Mason BJ. Craving in response to stress induction in a human laboratory paradigm predicts treatment outcome in alcohol-dependent individuals. Psychopharmacology. 2011;218(1):121–129. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2355-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen LK, Southwick SM, Kosten TR. SUDs in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder: a review of the literature. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158:1184–1190. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.8.1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaysen D, Atkins DC, Simpson TL, Stappenbeck CA, Blayney JA, Lee CM, Larimer ME. Proximal relationships between PTSD symptoms and drinking among female college students: Results from a daily monitoring study. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2014;28(1):62–73. doi: 10.1037/a0033588. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0033588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):617–627. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617. published correction appears in Archives of General Psychiatry, 62(7), 709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kranzler HR, Van Kirk J. Efficacy of naltrexone and acamprosate for alcoholism treatment. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2001;25(9):1335–1341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwako LE, Schwandt ML, Sells JR, Ramchandani VA, Hommer DW, George DT, Heilig M. Methods for inducing alcohol craving in individuals with co-morbid alcohol dependence and posttraumatic stress disorder: behavioral and physiological outcomes. Addiction Biology. 2015;20(4):733–746. doi: 10.1111/adb.12150. doi:10.1111/adb.12150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little RJA. A test of missing completely at random for multivariate data with missing values. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1988;83:1198–1202. [Google Scholar]

- Maisto SA, Sobell MB, Sobell LC. Reliability of self-reports of low ethanol consumption by problem drinkers over 18 months of follow-up. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1982;9:273–278. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(82)90066-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGovern MP, Lambert-Harris C, Acquilano S, Xie H, Alterman AI, Weiss RD. A cognitive behavioral therapy for co-occurring substance use and posttraumatic stress disorders. Addictive Behaviors. 2009;34(10):892–897. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.03.009. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Preparing people to change addictive behavior. Guilford; New York: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Mills KL, Teesson M, Back SE, Brady KT, Baker AT, Hopwood S, Ewer PL. Integrated exposure-based therapy for co-occurring posttraumatic stress disorder and substance dependence. JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association. 2012;308(7):690–699. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.9071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills KL, Teesson M, Ross J, Darke S, Shanahan M. The Costs and Outcomes of Treatment for Opioid Dependence Associated With Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Psychiatric Services. 2005;56(8):940–945. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.8.940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modell JG, Glaser FB, Mountz JM, Cyr L, Schmaltz S. Obsessive and compulsive characteristics of alcohol abuse and dependence: Quantification by a newly developed questionnaire. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1992;16:266–271. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1992.tb01374.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morley KC, Teesson M, Reid SC, Sannibale C, Thomson C, Phung N, Haber PS. Naltrexone versus acamprosate in the treatment of alcohol dependence: A multi-centre, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Addiction. 2006;101(10):1451–1462. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01555.x. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01555.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Najavits LM. Creating change: a new past-focused model for trauma and substance abuse. In: Ouimette P, Read JP, editors. Trauma and Substance Abuse: Causes, Consequences, and Treatment of Comorbid Disorders. Second Edition American Psychological Association Press; Washington, DC: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Najavits LM, Hien D. Helping Vulnerable Populations: A Comprehensive Review of the Treatment Outcome Literature on SUD and PTSD. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2013;69(5):433–479. doi: 10.1002/jclp.21980. doi:10.1002/jclp.21980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Najavits LM, Weiss RD, Liese BS. Group cognitive-behavioral therapy for women with PTSD and SUD. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 1996;13:13–22. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(95)02025-x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0740-5472(95)02025-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman SB, Tate SR, Anderson KG, Brown SA. Do trauma history and PTSD symptoms influence addiction relapse context? Drug & Alcohol Dependence. 2007;90(1):89–96. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.03.002. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nosen E, Littlefield AK, Schumacher JA, Stasiewicz PR, Coffey SF. Treatment of co-occurring PTSD-AUD: Effects of exposure-based and non-trauma focused psychotherapy on alcohol and trauma cue-reactivity. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2014;61:35–42. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2014.07.003. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2014.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrakis IL, Poling J, Levinson C, Nich C, Carroll K, Ralevski E, Rounsaville B. Naltrexone and disulfiram in patients with alcohol dependence and comorbid post-traumatic stress disorder. Biological Psychiatry. 2006;60(7):777–783. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.074. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrakis IL, Ralevski E, Desai N, Trevisan L, Gueorguieva R, Rounsaville B, Krystal JH. Noradrenergic vs serotonergic antidepressant with or without naltrexone for veterans with PTSD and comorbid alcohol dependence. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37(4):996–1004. doi: 10.1038/npp.2011.283. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/npp.2011.283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers MB, Gillihan SJ, Rosenfield D, Jerud AB, Foa EB. Reliability and validity of the PDS and PSS-I among participants with PTSD and alcohol dependence. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2012;26(5):617–623. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2012.02.013. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2012.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers MB, Halpern JM, Ferenschak MP, Gillihan SJ, Foa EB. A meta-analytic review of prolonged exposure for posttraumatic stress disorder. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010;30:635–641. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.04.007. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2010.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read JP, Brown PJ, Kahler CW. Substance use and posttraumatic stress disorder: Symptom interplay and effects on outcome. Addictive Behaviors. 2004;29:1665–1672. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.02.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resko SM, Mendoza NS. Early attrition from treatment among women with cooccurring SUDs and PTSD. Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions. 2012;12(4):348–369. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/1533256X.2012.728104. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds M, Mezey G, Chapman M, Wheeler M, Drummond C, Baldacchino A. Co-morbid post-traumatic stress disorder in a substance misusing clinical population. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2005;77:251–258. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shek D, Ma C. Longitudinal data analysis using linear mixed models in SPSS: Concepts procedures and illustrations. Scientific World Journal. 2011;11:42–76. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2011.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson TL, Stappenbeck CA, Varra AA, Moore SA, Kaysen D. Symptoms of posttraumatic stress predict craving among alcohol treatment seekers: Results of a daily monitoring study. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2012;26(4):724–733. doi: 10.1037/a0027169. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0027169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha R, Fox HC, Hong KA, Bergquist K, Bhagwagar Z, Siedlarz KM. Enhanced negative emotion and alcohol craving, and altered physiological responses following stress and cue exposure in alcohol dependent individuals. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34(5):1198–1208. doi: 10.1038/npp.2008.78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell L, Maisto SA, Sobell MB, Cooper AM. Reliability of alcohol abusers’ self-reports of drinking behavior. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1979;17:157–160. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(79)90025-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Alcohol timeline followback users' manual. Addiction Research Foundation; Toronto, Canada: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Starosta AN, Leeman RF, Volpicelli JR. The BRENDA model: Integrating psychosocial treatment and pharmacotherapy for the treatment of alcohol use disorders. Journal of Psychiatric Practice. 2006;12(2):80–89. doi: 10.1097/00131746-200603000-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Triffleman E, Kellogg S. Substance dependence post-traumatic stress disorder therapy (SDPT): A therapist's manual. 1997 Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Triffleman E, Carroll K, Kellogg S. Substance Dependence Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Therapy: An Integrated Cognitive-Behavioral Approach. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 1999;17:3–14. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(98)00067-1. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0740-5472(98)00067-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worley M, Gallop R, Gibbons MC, Ring-Kurtz S, Present J, Weiss RD, Crits- Christoph P. Additional Treatment Services in a Cocaine Treatment Study: Level of Services Obtained and Impact on Outcome. American Journal on Addictions. 2008;17(3):209–217. doi: 10.1080/10550490802021994. doi:10.1080/10550490802021994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zilberman ML, Tavares H, el-Guebaly N. Relationship between craving and personality in treatment-seeking women with substance-related disorders. BMC Psychiatry. 2003;3 doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-3-1. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-3-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.