Highlights

-

•

There are no case in the literature involving “second and third” molar.

-

•

Affects an unusual region.

-

•

A well-documented case.

Keywords: Abnormalities, Molar, Panoramic radiography, Tomography

Abstract

Fusion and gemination is not an uncommon finding and affected most primary dentition and the permanent maxillary incisors. These changes can develop a series of complication. A 11-year-old male presented radiography finding: an unusual mandibular second molar. A well-documented case brings a challenge for radiologists classify between fusion and gemination. In conclusion, this alteration although common in other regions, there are no case in the literature involving “second and third” molar.

1. Introduction

Variation in number, size and form of teeth is not an uncommon finding. Gemination results of a developmental aberration of ectoderm and the mesoderm [1], the teeth germ divides and results a “two teeth”, with two crowns or one large partially separated crown, can be share a pulp chamber and root canal, affected most the permanent maxillary incisors [2].

Fusion is a union of two teeth as a result of some physical force or pressure, can be present with only one pulp chamber and a confluence of enamel and dentine as in gemination, or there may be two separate pulp chambers and union only of the dentine [3], involving permanent dentition are very rare 0–0.8%, with the majority of cases seen in anterior teeth [4], the congenital absence of the adjacent tooth from the dental arch can be differentiated fusion from gemination [3].

That anomalous tooth can develop a series of complication like malocclusion, caries, tooth misalignment, arch asymmetry and functional problems [5]. Occasionally, orthodontists encounter patients with this anomalies and it is extremely difficult to restore the natural look of such a wide tooth [6]. Currently the searching of perfect smile with a white and strait dental, like a celebrities, it takes several people realize an orthodontic treatment without a good planning and indiscriminate use of braces in Brazil.

The purpose of this case report was to describe anomalous and rare tooth in a young adult male in unusual right mandibular second molar, and discuss the possibilities involving the anomaly diagnosis.

2. Case report

A 11-year-old male in good health presented on radiology dental service to realize Panoramic Radiography (PR) for initial orthodontic treatment. There was no history of orofacial trauma. Radiographic (Fig. 1) evaluation showed second premolar agenesis (mandibular left region—35) and a second molar (mandibular right) apparently overlaid on the third molar. It is possible to the observer that “supposed third molar” has bigger development compared to their counterparts, 1/3 showing the formation of roots. It is very close to the level of development of the second molar, which had half of root formation. The second radiography (Fig. 2), three years later, showed a second molar (mandibular right) that had two separate canals and shared one (second molar mesial root and first molar distal root). The situation is the same in relation root formation, now the supposed third molar has bigger development compared to their counterparts, 1/2 showing the formation of roots. The second molar has almost complete root formation. The both dental apex still open is in agreement of patient age, but the supposed third molar was advanced development compared to the others. Initially the crown seems partially separated. Nolla stage 5 was recorded for tooth 38, stage 6 for teeth 18 and 28, stage 7 for “tooth 48” and stage 8 for “tooth 47”, the orthodontic treatment has started.

Fig. 1.

Panoramic Radiography (PR) for initial orthodontic treatment, showed second premolar agenesis (mandibular left region—35) and a second molar (mandibular right) apparently overlaid on the third molar, see that this tooth has more advanced root development than their congeners.

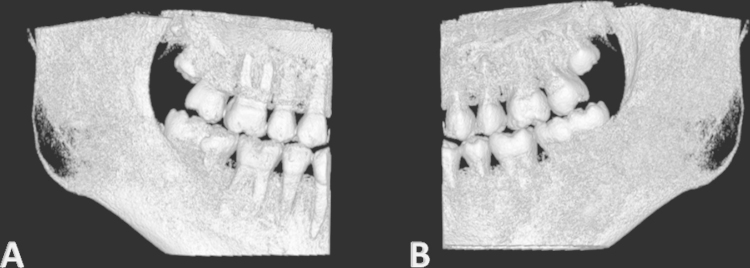

Fig. 2.

Second radiography, three years later, showed a second molar (mandibular right) had two separate canals and shared one (second molar mesial root and first molar distal root).

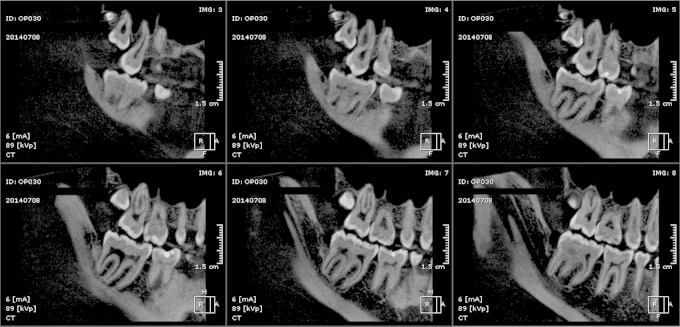

After three years of orthodontic treatment, was removed the braces and contention was placed. The patient was referred for extraction of anomalous tooth that was asymptomatic. Clinically, the tooth presented separated crowns and the number of teeth does not change (Fig. 3). Periapical radiographs of the region (Fig. 4) and the third PR (Fig. 5) presented a tooth with three roots, two crowns sharing a pulp chamber and one root canal. CT scan performed on Cone Beam Computed Tomography—CBCT (OP300-Instrumentarium Dental). In the sagittal view (Fig. 6), first slice (IMG: 24), the tooth in question due overlapping teeth presents enamel layer between the pulp chambers, observe the tooth 46 with central image, which indicates that the anomalous teeth is slightly off the dental arch, also seen in the photographic image. Note the superior forth molar presence. In the next slice (IMG: 25) presents clear union crown, showing a highlighted sulcus dividing the crowns. There caries lesion in the distal sulcus of the mesial crown. Clear presence of a “double teeth” (slice IMG: 26) with one pulp chamber, three root canals, mesial, distal and central. Note the pronounced pulp horn in the mesial which may indicate that it is a gemination. In the axial view (Fig. 7) the sequence showed initially three separate roots (IMG: 23 and 24), the next slice begins “fusion” of the mesial root with the “median” root. Slices IMG: 26 and IMG: 27, the pulp chamber is shared, and finally showed the union, the mesial and median root are covered by dentin and is seen the distal root canal. In panorama view (Fig. 8), shows the same details of panoramic radiography. The 3D reconstruction (Fig. 9) corroborates the clinical vision.

Fig. 3.

Intraoral photography. Clinically patient presented separated crowns and the number of teeth does not change.

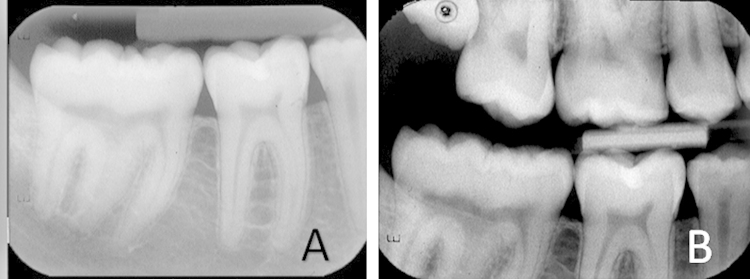

Fig. 4.

(A) Periapical radiography; (B) Bite-wing radiography.

Fig. 5.

Third radiography presented a tooth with three roots, two crowns sharing a pulp chamber and one root canal (the other third molars are with open apex). Presence of superior forth molar.

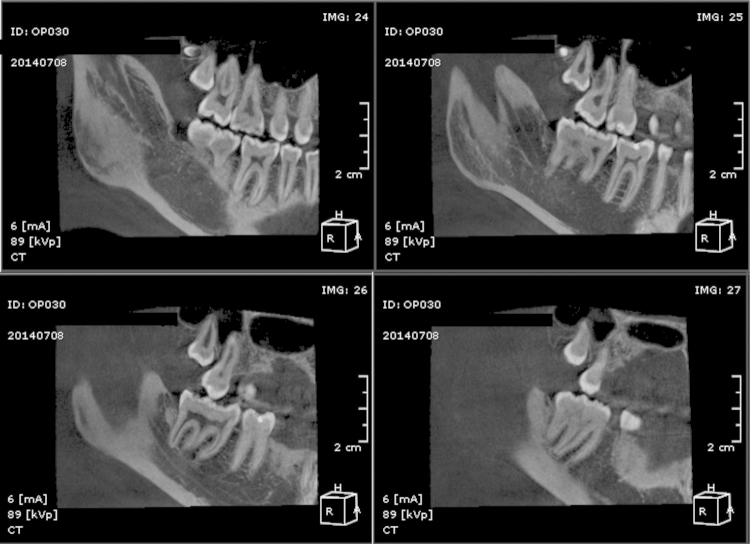

Fig. 6.

CT scan performed on CBCT (OP300-Instrumentarium Dental). Sagittal view, IMG: 24, the tooth in question due overlapping teeth presents enamel layer between the pulp chambers, observe the tooth 46 with central image, which indicates that the anomalous teeth is slightly off the dental arch. Note the superior forth molar presence. In the next slice (IMG: 25) presents clear union crown, showing a highlighted sulcus dividing the crowns. There caries lesion in the distal sulcus of the mesial crown. Clear presence of a “double teeth” (slice IMG: 26) with one pulp chamber, three root canals, mesial, distal and central. Note the pronounced pulp horn in the mesial which may indicate that it is possible a gemination.

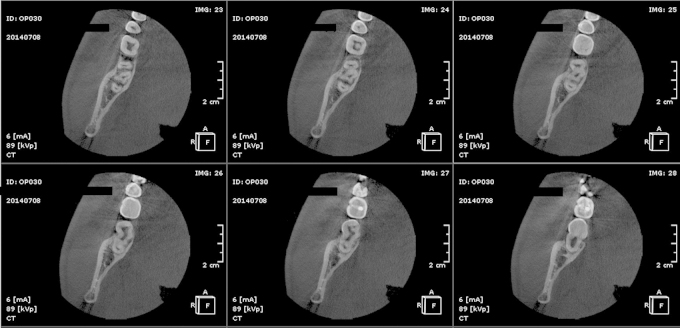

Fig. 7.

Axial view; the sequence showed initially three separate roots (IMG: 23 and 24), the next slice begins “fusion” of the mesial root with the “median” root. Slices IMG: 26 and IMG: 27, the pulp chamber is shared (the junction of the pulp chamber or the pulp portion of these roots), and finally showed the union, the mesial and median root are covered by dentin and is seen the distal root canal.

Fig. 8.

Panorama view; showed the same details of sagittal view. Note the curvature of mesial and distal roots, as if there were no central root.

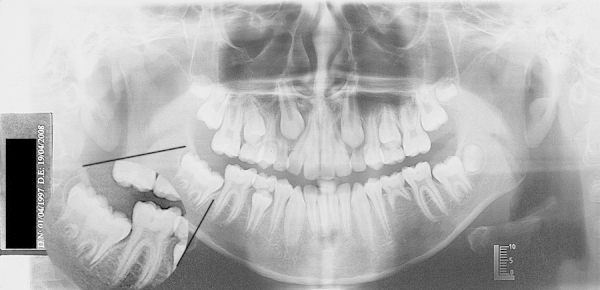

Fig. 9.

The 3D reconstruction. (A) Vestibular view. (B) Lingual view. 3D reconstruction corroborates the clinical vision.

3. Discussion

According to Kapadan et al. [7], the prevalence of “double teeth” in primary dentition in different countries were 0.1–4.1% and boys had more than girls. The lower region more often presented “double teeth” (66.7%) and unilateral occurrence (68.4%).

Differentiating gemination and fusion can be difficult, and it is usually confirmed by counting the number of teeth in the area and radiological evaluation [8].

A radiographic consideration is the difference in root configuration often seen between fusion and gemination, in the case of fusion there are usually two separate root canals, whereas in gemination there is usually one large common root canal [9]. Based on Tannenbaum and Ailing [3], this case report showed clinically and radiographically like a gemination of second molar, sharing a pulp chamber and root canals, and the presence of two crowns, occurs agenesis of the third molar. The third molar agenesis incidence ranges from 7% to 20% of population [10], [11]. Considering all these factors, is a rare event.

In the other hand, could be fusion? Fusion can be variable depending the stage of germs development, pulp chamber and the canals might be linked or separates [12]. Second molar germ with the third molar, this fusion would occur in initial stage of second molar crown maturation (Nolla stage 6 or 7) and stage 4 of third molar germ, this germ follow growth and development of the second molar germ? However, it would be possible considering the initial stage of development of others third molars germs?

Diagnostic difficulties arise when fusion occurs between a “normal” tooth and a supernumerary tooth, resulting in a full complement of teeth and giving the clinical appearance of gemination [9]. Thus, this case can be another possibility, second molar fused with a supernumerary tooth and occurs agenesis of the third molar.

The treatment suggested by dentist (teeth extraction), radiographically, was considering iatrogenic due the tooth not presented any problem (malocclusion, bad tooth alignment, arch asymmetry and functional problems), only a caries lesion in dentin (“47” crown). A restorer treatment was indicated. In case of endodontic involvement several articles report technicians of successful nonsurgical endodontic treatment [12], [13].

Child with transitional dentition (after eruption of first permanent tooth) and adolescent with permanent dentition (prior to eruption of third molars) it should individualized radiographic exam consisting of posterior bitewings with panoramic exam or posterior bitewings and selected periapical image [14], according American Dental Association recommendations, emphasizing the importance of premature diagnosis, for evaluation and/or monitoring of dentofacial growth and development or assessment of dental and skeletal relationships. In this case the documentation of transitional dentition was made would be possible to determine which anomaly the tooth is affected. Thus, there remains a classification often used in the literature when it is not defined the change: “Double teeth”.

4. Conclusion

In conclusion, this alteration although common in other regions, there are no case in the literature involving “second and third” molar. Underscoring that the patient also has number anomalies, agenesis of 35 tooth and forth molar presence. In this case, the radiology does not close diagnose, but bring an important discussion about possible dental findings and show the importance of a great clinical judgment and evaluation.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Funding

Do not have any funding to this case report. Just scholarship for PhD Student Angela Jordão Camargo.

Ethical approval

This case report was written based on patient archive and he authorized the publication.

Consent

The patient given your approval and was fully informed, written consent was documented in the paper.

Author contribution

Angela Jordão Camargo: data collection, data analysis, data interpretation and writing the paper.

Emiko Saito Arita: study concept and data interpretation.

Plauto Christopher Aranha Watanabe: study design, data collection and or interpretation.

Guarantor

Angela Jordão Camargo, Emiko Saito Arita and Plauto Christopher Aranha Watanabe.

Acknowledgment

Thanks to financial support from Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES).

Contributor Information

Angela Jordão Camargo, Email: dra.angelacamargo@gmail.com, angela.camargo@usp.br.

Emiko Saito Arita, Email: emiko.sp@terra.com.br.

Plauto Christopher Aranha Watanabe, Email: watanabe@forp.usp.br.

References

- 1.Grover P.S., Lorton L. Gemination and twinning in the permanent dentition. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. 1985;59:313–318. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(85)90173-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kremeier K., Pontius O., Klaiber B., Hülsmann M. Nonsurgical endodontic management of a double tooth: a case report. Int. Endod. J. 2007;40:908–915. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2007.01300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tannenbaum K.A., Ailing E.E. Anomalous tooth development: case reports of gemination and twinning. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. 1963;16:883–887. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(63)90326-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stabholz A., Friedman F. Endodontic therapy of an unusual maxillary permanent first molar. J. Endod. 1983;9(7):293–295. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(83)80121-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dhindsa A., Garg S., Damle S.G., Opal S., Singh T. Fused primary first mandibular macromolar with a unique relation to its permanent successors: a rare tooth anomaly. Eur. J. Dent. 2013;7:239–242. doi: 10.4103/1305-7456.110195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steinbock N., Wigler R., Kaufman A.Y., Lin S., Abu-El Naaj I., Aizenbud D. Fusion of central incisors with supernumerary teeth: a 10-year follow-up of multidisciplinary treatment. J. Endod. 2014;40(7):1020–1024. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2013.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kapdan A., Kustarci A., Buldur B., Arslan D., Kapdan A. Dental anomalies in the primary dentition of Turkish children. Eur. J. Dent. 2012;6:178–183. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Altug-Atac A.T., Erdem D. Prevalence and distribution of dental anomalies in orthodontic patients. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofacial Orthop. 2007;131:510–514. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2005.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kelly J.R. Gemination fusion, or both? Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. 1978;45(4):655–656. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(78)90051-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garn S.M., Lewis A.B. The relationship between third molar agenesis and reduction in tooth number. Angle Orthod. 1962;32(1):14–18. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vastardis H. The genetics of human tooth agenesis: new discoveries for understanding dental anomalies. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofacial Orthop. 2000;117:650–656. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ballal S., Sachdeva G.S., Kandaswamy D. Endodontic management of a fused mandibular second molar and paramolar with the aid of spiral computed tomography: a case report. J. Endod. 2007;33:1247–1251. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2007.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beltes P., Huang G. Endodontic treatment of an unusual mandibular second molar. Endod. Dent. Traumatol. 1997;13:96–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-9657.1997.tb00018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.American Dental Association, Dental radiographic examinations: recommendations for patient selection and limiting radiation exposure, 2012.