Highlights

-

•

This is the first reported case of metachronous isolated omental metastasis of an initially T1 clear-cell RCC.

-

•

Noninvasive diagnostic studies may not differentiate sarcoidosis from metastatic spread of RCC.

-

•

Sarcomatoid paraneoplastic syndrome was triggered by the formation of omental metastatic deposit in this patient who have been previously diagnosed with sarcoidosis.

Keywords: Metastasis, Omentum, Renal cell carcinoma, Case report

Abstract

Introduction

Metachronous metastatic spread of clinically localized renal cell carcinoma (RCC) affects almost 1/3 of the patients. They occur most frequently in lung, liver, bone and brain. Isolated omental metastasis of RCC has not been reported so far.

Case presentation

A 62-year-old patient previously diagnosed and treated due to pulmonary sarcoidosis has developed an omental metastatic lesion 13 years after having undergone open extraperitoneal partial nephrectomy for T1 clear-cell RCC. Constitutional symptoms and imaging findings that were attributed to the presence of a sarcomatoid paraneoplastic syndrome triggered by the development this metastatic focus complicated the diagnostic work-up. Biopsy of the [18F]-fluorodeoxyglucose (+) lesions confirmed the diagnosis of metastatic RCC and the patient was managed by the resection of the omental mass via near-total omentectomy followed by targeted therapy with a tyrosine kinase inhibitor.

Discussion

Late recurrence of RCC has been reported to occur in 10–20% of the patients within 20 years. Therefore lifelong follow up of RCC has been advocated by some authors. Diffuse peritoneal metastases have been reported in certain RCC subtypes with adverse histopathological features. However, isolated omental metastasis without any sign of peritoneal involvement is an extremely rare condition.

Conclusion

To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of metachronously developed, isolated omental metastasis of an initially T1 clear-cell RCC. Constitutional symptoms, despite a long interval since nephrectomy, should raise the possibility of a paraneoplastic syndrome being associated with metastatic RCC. Morphological and molecular imaging studies together with histopathological documentation will be diagnostic.

1. Introduction

The incidence of renal cell carcinoma (RCC) has been rising, which includes both early stage and late stage disease [1]. Approximately 85% of all RCCs are of clear cell histology [2]. About 20–30% of patients have metastatic disease at the time of diagnosis, and about 20–40% of patients with clinically localized disease at diagnosis will eventually develop metastases [3]. RCC often metastasizes to the lung, bone, liver and brain. Herein, we report a case with isolated omental metastasis of RCC that has developed metachronously 13 years after the initially localized disease was managed by partial nephrectomy.

2. Description of the case

A currently 62-year-old male presented with decreased force of urinary stream, frequency, malaise, loss of apatite, difficulty in breathing and nonproductive cough. He was treated due to pulmonary sarcoidosis in the past and apart from hypertension he did not have any systemic comorbidity. He was using bronchodilators on demand due to airway-related problems and he received corticosteroids due to sarcoidosis in the past. He had undergone open extraperitoneal partial nephrectomy elsewhere due to T1 clear-cell RCC, 13 years ago. He also reported transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) and consequent office-based urethral dilatation procedures due to post-TURP urethral stricture. He had complied with the postoperative surveillance protocol of RCC and until 2013 there was no sign of recurrence or metastasis.

Imaging workup began with an abdominal ultrasound, demonstrating a solid round mass superolateral to the urinary bladder with nonspecific heterogeneous echotexture. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) confirmed this mass as a well-circumscribed structure abutting the superolateral urinary bladder, with a thin but preserved intervening fat plane between it and the urinary bladder (Fig. 1). For further staging, [18F]-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) scan was undertaken, demonstrating the index supravesical lesion to be FDG-hypermetabolic, as well as innumerable FDG-hypermetabolic lesions with an osseous, renal, pleural, and lymphatic distribution (Fig. 2). Percutaneous biopsy was directed to both the index supravesical lesion as well as the most hypermetabolic extravesical site (right iliac bone lesion). Histopathology of the supravesical specimen revealed clear cell RCC (representing delayed isolated omental metastasis) while the osseous specimen was interpreted as sarcomatoid reaction (Fig. 3).

Fig. 1.

Sagittal fat saturated T2-weighted magnetic resonance image. A round, well-circumscribed, T2-heterogeneous signal intensity mass (arrow) displaces the anteroinferior urinary bladder inferiorly.

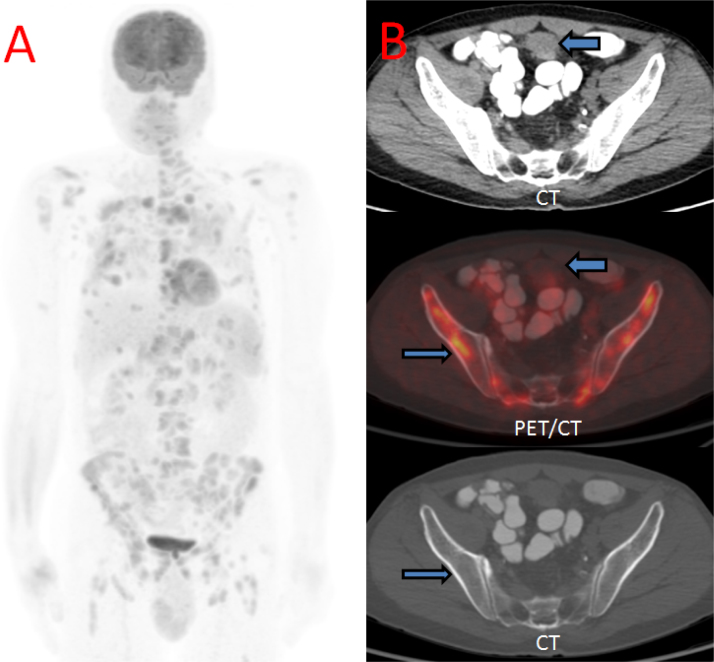

Fig. 2.

[18F]-Fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) (A) Maximum intensity projection (MIP) image shows innumerable hypermetabolic foci throughout the lungs, osseous structures, and lymph nodes above and below the diaphragm. (B) CT soft tissue window, Fusion PET-CT, and CT bone window images show the index supravesical lesion with faint FDG uptake (thick arrow). Focal hypermetabolic right iliac bone lesion was also targeted for biopsy revealing sarcomatoid reaction (thin arrow).

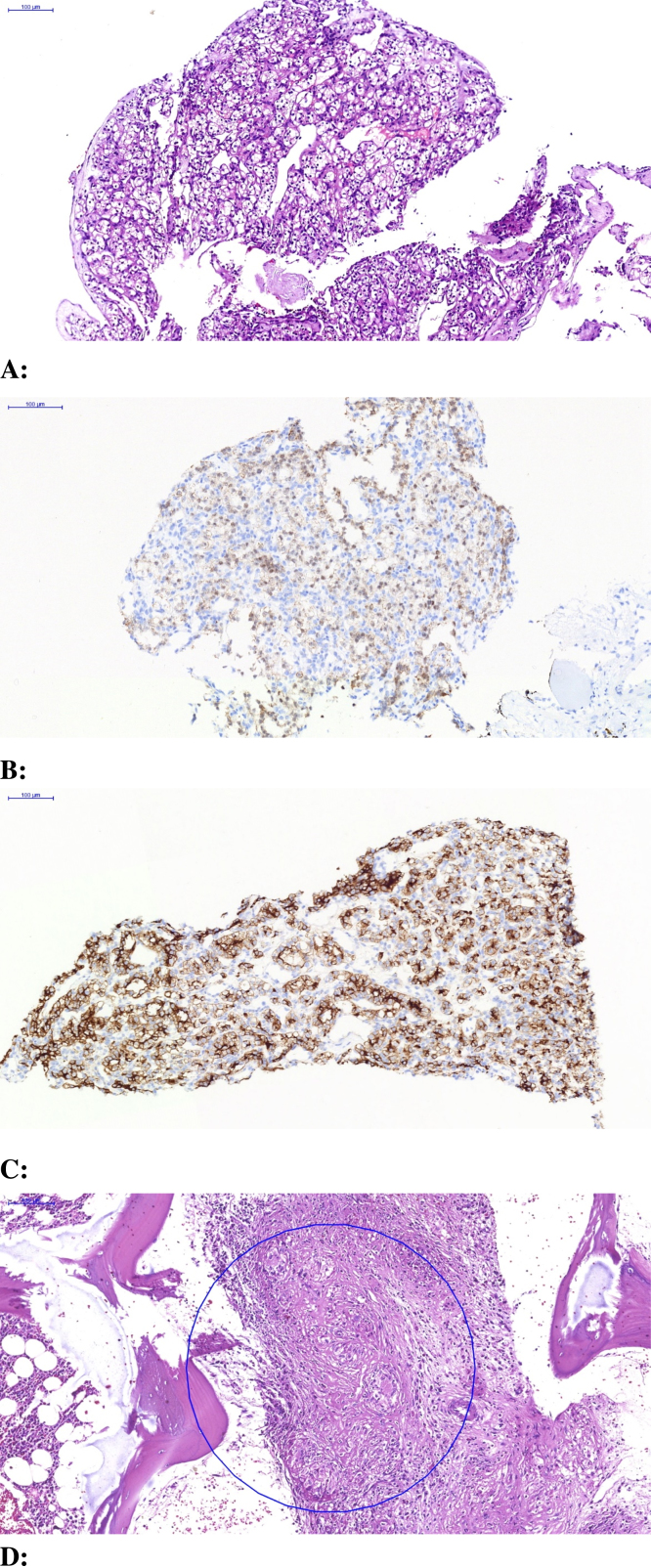

Fig. 3.

(A) Histopathology of the suprapubic mass demonstrate a neoplasm composed of cells with clear vacuolated cytoplasm and hyperchromatic small nuclei (H&E, ×90). (B) Immunohistochemically, tumor cells show nuclear positivity with PAX8 (IHC stain ×150). (C) Immunohistochemically, tumor cells show strong, diffuse positivity with CD10 (IHC stain ×150). (D) H&E stained sections of the neddle biopsy from the iliac bone showing granulomatous inflammation (×150).

Then, we made a consultation with the Pulmonary Medicine department and the advice given by them was to remove the metastatic lesion since widespread FDG (+) lesions and accompanying constitutional symptoms may be a sort of paraneoplastic syndrome, which can be seen quite often in RCC. We opted for an open surgery to remove the mass and during exploration it was found to be located within the omentum as a clearly palpable, isolated nodularity (Fig. 4). Neither the intestinal segments nor the peritoneum seemed to be affected by the metastatic spread. We performed a near-total omentectomy and excised the mass with clear margins. In the same session, we performed direct visual endoscopic internal urethrotomy due to bulbomembranous urethral stricture which seemed explanatory for the emptying phase lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS). Histopathological examination findings in the omental mass were concordant with the tru-cut biopsy result (Fig. 5). After having the opinions of Medical Oncology and Pulmonary Medicine specialists, the patient was scheduled for adjuvant targeted therapy with a tyrosine kinase inhibitor (sunitinib).

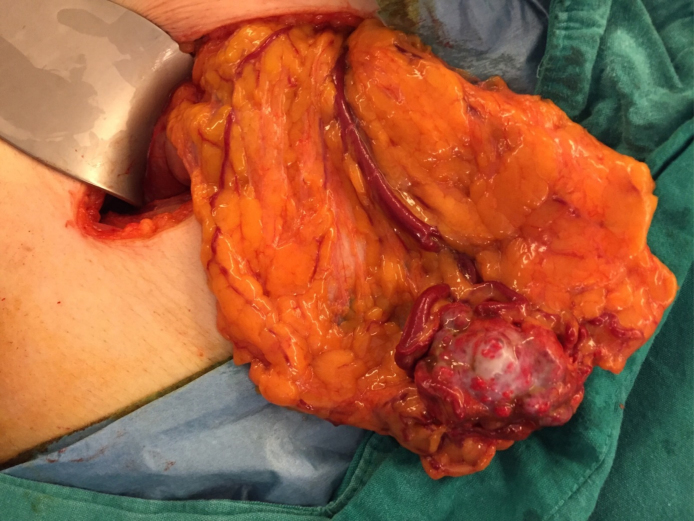

Fig. 4.

Macroscopic appearance of the omental metastatic deposit. Note its prominent vascular supply and collateral vascular network covering its surface.

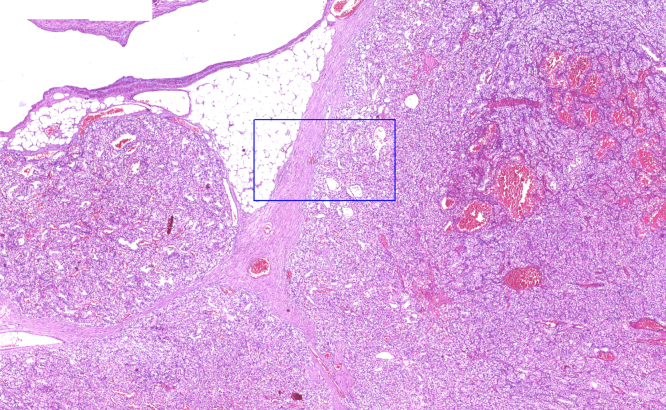

Fig. 5.

Omental tumor has similar histopathologic features with the suprapubic mass, consistent with clear cell renal cell carcinoma (H&E ×30).

3. Discussion

Late recurrence is one of the biological behaviors of RCC. It has been reported that the recurrence rate 5 years after surgery is 8.8% and the rate after 10 years is 11% [4], [5]. A previous study of patients with RCC who did not develop recurrence within a 10-year follow-up observation period reported that late recurrence rates were 10.5 and 21.6% at 15 and 20 years, respectively [6]. Therefore, some authors have highlighted the importance of postoperative surveillance and recommended life-long follow-up of RCC after the initial treatment [6]. Supporting this phenomenon; our case, who had pT1 clear cell RCC at the time of diagnosis, has developed an isolated omental metastasis 13 years following partial nephrectomy.

Some aggressive RCC subtypes with adverse histopathological features (sarcomatoid differentiation etc.) can present with diffuse peritoneal metastases involving the omentum [7], [8]. However, development of metachronous omental metastasis(es), particulary in the absence of diffuse peritoneal involvement, is an extremely rare condition in the natural history of RCC. Win et al. have recently reported a patient with an initially T3N0M0 chromopobe RCC, who developed an interaortocaval lymph node enlargement 1 year after laparoscopic radical nephrectomy [9]. They have incidentally discovered an additional omental metastatic deposit while removing this interaortocaval mass. Despite surgical excision and adjuvant therapy with tyrosine kinase inhibitors, the omental nodules recurred and they were able to detect this recurrence via FDG avidity on surveillance PET/CT studies [9].

RCC is unique for its association with various paraneoplastic syndromes. These can range from those manifesting as constitutional symptoms (ie., fever, cachexia, and weight loss) to those that result in specific metabolic and biochemical abnormalities (ie., hypercalcemia, nonmetastatic hepatic dysfunction, amyloidosis, etc.). The constitutional symptoms of our patient was initially attributed to the progression of sarcoidosis. However, disseminated osseous involvement is quite rare in sarcoidosis and in the absence histological proof of non-caseating granulomata on biopsy specimens it would not be possible to conclude upon the diagnosis of sarcoidosis. Moreover, the probability of metastatic dissemination must be evaluated in a patient who has been operated due to localized RCC. On the other hand, Willis et al. have reported that sarcoidosis and RCC can coexist in the same individual. In their case, the undiagnosed condition of sarcoidosis complicated the staging of bilateral RCC. Prior to the initiation of immunotherapy due to the initial diagnosis of mRCC, they also performed an FDG PET/CT scan and the difference in metabolic activity between the primary site of disease and the presumed metastatic disease suggested the possibility of two separate disease processes. The patient underwent bilateral partial nephrectomies and was ultimately diagnosed with stage T1 bilateral RCC. Demonstration of non-caseating granulomas on pulmonary nodules confirmed the diagnosis of coexistent sarcoidosis in this case [10].

This patient underwent extensive imaging work-up in an effort to exclude RCC metastasis, however the summary of non-invasive studies provided equivocal results. For example, initial ultrasound and MRI findings revealed the solitary index lesion (supravesical mass). However, the subsequent FDG PET/CT scan demonstrated the FDG-hypermetabolic index lesion but also innumerable disseminated FDG-hypermetabolic foci. Moreover, FDG PET-CT is known to carry some limitation in the evaluation of RCC (unless the RCC is high grade). Therefore, combining the known pulmonary and surgical history with the patient’s delayed presentation and dramatic PET-CT findings in the context of benign-appearing renal fossae, tissue sampling was deemed necessary to guide the next steps in care. Eventually, we thought that most of the presenting symptoms, except emptying phase LUTS, and the FDG-hypermetabolic lesions should be considered as a component of a sarcomatoid paraneoplastic syndrome triggered by metastatic progression of an initially localized RCC.

Surgical resection of the primary tumor and metastatic deposits continues to play an important role in managing patients with mRCC when aiming for complete remissions, the likelihood of which is further supplemented with the addition of systemic targeted therapy. Therefore, after the removal of omental metastasis, our patient was scheduled to receive targeted therapy with sunitinib.

4. Conclusions

To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of metachronous isolated omental metastasis of an initially T1 clear-cell RCC. Metastatic spread can develop many years after the surgical treatment of localized RCC. Constitutional symptoms may be a sign of paraneoplastic syndrome that was triggered by RCC progression. Coexistent medical conditions, such as sarcoidosis as in our case, may complicate the diagnostic process. Morphological and functional imaging studies together with histopathological assessment of biopsy materials are necessary to confirm the diagnosis of mRCC and rule out other systemic disease processes.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Funding

None.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images.

Author contribution

Ömer Acar has written the manuscript. The operation was carried out by Tuna Mut, Ömer Acar and Tarık Esen. Pathology was reported by Yeşim Sağlıcan. Fatih Selcukbiricik, Levent Tabak have contributed to the clinical management of the patient. The radiological imaging studies were reported and managed by Alan Alper Sag, Okan Falay.

Guarantor

Tarık Esen.

References

- 1.King S.C., Pollack L., Li J., King J.B., Master V.A. Continued rise in incidenceof renal cell, carcinoma especially in young and high-grade disease-US 2001–2010. J. Urol. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.12.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karumanchi S.A., Merchan J., Sukhatme V.P. Renal cancer: molecular mechanisms and newer therapeutic options. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 2002;11(1):37–42. doi: 10.1097/00041552-200201000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ljungberg B., Campbell S.C., Choi H.Y. The epidemiology of renal cellcarcinoma. Eur. Urol. 2011;60(4):615–621. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2011.06.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McNichols D.W., Segura J.W., DeWeerd J.H. Renal cell carcinoma: long-term survival and late recurrence. J. Urol. 1981;126:17–23. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)54359-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Park Y.H., Baik K.D., Lee Y.J. Late recurrence of renal cell caricinoma >5 years after surgery: clinicopathological characteristics and prognosis. BJU Int. 2012 doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.11246.x. (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miyao N., Naito S., Ozono S. Late recurrence of renal cell carcinoma: retrospective and collaborative study of the Japanese Society of Renal Cancer. Urology. 2011;77:379–384. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2010.07.462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tartar V.M., Heiken J.P., McClennan B.L. Renal cell carcinoma presenting with diffuse peritoneal metastases: CT findings. J. Comput. Assist. Tomogr. 1991;15:450–453. doi: 10.1097/00004728-199105000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stavropoulos N.J., Deliveliotis C., Kouroupakis D., Demonakou M., Kastriotis J., Dimopoulos C. Renal cell carcinoma presenting as a large abdominal mass with an extensive peritoneal metastasis. Urol. Int. 1995;54:169–170. doi: 10.1159/000282715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Win A.Z., Aparici C.M. Omental nodular deposits of recurrent chromophobe renal cell carcinoma seen on FDG-PET/CT. J. Clin. Imaging Sci. 2014;4:51. doi: 10.4103/2156-7514.141560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Willis H., Heilbrun M., Dechet C. Co-existing sarcoidosis confounds the staging of bilateral renal cell carcinoma. J. Radiol. 2011;5(1):18–27. doi: 10.3941/jrcr.v5i1.553. Case Rep. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]