Highlights

-

•

Myeloid Sarcoma (MS) is a rare laryngeal malignancy that arise from myelodysplastic syndromes, malignancy or de novo.

-

•

Laryngeal MS is may be asymptomatic of haematological manifestations.

-

•

The role of surgery in MS of the larynx is for tissue biopsy and to provide a secure the upper airway via tracheostomy.

Keywords: Leukaemia, Laryngeal, Chemotherapy, Dyspnoea, Sarcoma

Abstract

Introduction

Myeloid Sarcoma (MS) or Granulocytic Sarcoma is an uncommon laryngeal malignancy. It may arise from myelodysplastic syndromes, malignancy or de novo. Presentation in the larynx is rare and some may present with Acute Myeloid Leukaemia (AML) whereby the later may be asymptomatic.

Case Presentation

A 44-year-old South East Asian lady presented with a six months history of hoarseness, shortness of breath, reduced exercise tolerance, weight loss and laryngeal irritation. Symptoms progressed to coughing with liquids two months prior. On examination, she had a resting biphasic stridor and laryngoscopy revealed right immobile vocal cord with a firm right ventricle mass extending into the right paraglottic space. She was pale and haematology investigations revealed microcytic hypochromic anaemia. Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) of the neck and thorax showed thickening of the right false cord, true cord and aryepiglottic fold. A biopsy taken during endolaryngeal microsurgery (ELMS) confirmed myeloid sarcoma of the right ventricle and para glottic mass. Further investigation revealed a background of AML and she then underwent chemotherapy.

Discussion

MS is a rarity with only nine reported cases between the years of 1954 until 2015. Immunohistochemistry and immunophenotyping are definite for diagnosis confirmation as MS cells often exhibit myeloperoxidase (MPO), lymphocyte common antigen (LCA) and CD117 markers. MS is treated with are chemotherapy (either systemic or intrathecal), radiotherapy, surgical excision or in combination. Systemic chemotherapy has better efficacy and prognosis as compared to localised treatment of radiotherapy or surgical excision. However, there has yet to be a definitive chemotherapy protocol. Prognosis is poor with a 5-year survival rate of 48%.

Conclusion

Although laryngeal MS is a rare phenomenon, early recognition is key and patients should always be investigated for an underlying myeloproliferative or dysplastic disease.

1. Introduction

Myeloid Sarcoma (MS) of the larynx is a rare and uncommon type of laryngeal malignant tumour. They composed of immature myeloid cells which are of the extramedullary type of neoplasm [1]. It was first introduced by Burns in 1811 known as chloroma or granulocytic sarcoma. The term “Chloroma” was used due to its typical form of green colour that is imparted to the tissues as a result of the high concentration of myeloperoxidase found within the immature cells [2]. It was further on referred as “Granulocytic Sarcoma” in 1966 by Rapaport as not all cells are green; but 30% are grey, white or brown depending on the state of oxidation of the pigmented enzymes [1], [3].

It is said that this tumour is typically associated with liquid tumours of Acute Myeloid Leukaemia (AML), myelodysplastic syndromes, coinciding with systemic diseases or arising de novo [1]. The exact incidence of myeloid sarcoma in the larynx is yet unknown with a handful of reporting due to its rarity [2], [3]. It has no gender predilection, but it is more common in children than adult population, with 60% of patients younger than 15 years old [4].

Literature review suggests that myeloid sarcoma can be seen to occur in any part of the organ, with otolaryngology, head and neck regions being the frequently reported sites [2]. However, laryngeal involvement is rarely associated with myeloid sarcoma [4], [5].

Byrd et al. conducted a review of 154 cases of extramedullary leukaemia revealed that skin was the commonest site followed by lymph nodes, spine, small intestine, orbit and nasal sinuses [6].

Furthermore, Horny et al. presented a review of 170 cases of primary laryngeal involvement by haematological tumour, whereby only one was a myeloid sarcoma of the larynx.

The majority of patients diagnosed with myeloid sarcoma may be asymptomatic of AML [7]. However, in some cases, laryngeal myeloid sarcoma may precede and represent an initial manifestation of AML by several months or years. The previous report has also shown that myeloid sarcoma may develop in a patient with relapse of previously treated AML.

This article discussed the rare and unusual occurrence of de novo myeloid sarcoma of the larynx in middle-aged woman who presented with hoarseness and sudden onset of shortness of breath. We have also discussed the common presenting symptoms and current treatment protocol based on the available literature review.

2. Case report

A 44-year-old lady, South East Asian in ethnicity with no significant past medical history presented to the Otolaryngology outpatient clinic with a six months history of hoarseness and occasional loss of voice. She is a teacher by profession and her hoarseness was exaggerated during voice straining at the classroom. She complained of progressively worsening reduction in effort tolerance, resulting in her being short of breath on performing activities of daily living such as cooking and dressing. There was also significant unintentional weight loss of 5 kilograms over two months associated with loss of appetite. Moreover, she complained of frequent laryngeal irritation for two months, described as globus sensation in the throat resulting in recurrent non-productive cough. This was associated with occasional choking and coughing on swallowing liquids although she denied any dysphagia or odynophagia.

She had no significant past medical or surgical history. Four months into her symptoms, she complained of breathing difficulties with noisy breathing. She was admitted to a district hospital and was treated for bronchial asthma. The earlier symptoms repeated itself two weeks later whereby she was readmitted at the same hospital and nursed in the intensive care unit for an acute exacerbation of bronchial asthma. An otolaryngology consult was obtained and subsequently, she was referred to UKM Medical Centre, Kuala Lumpur for a tertiary care management.

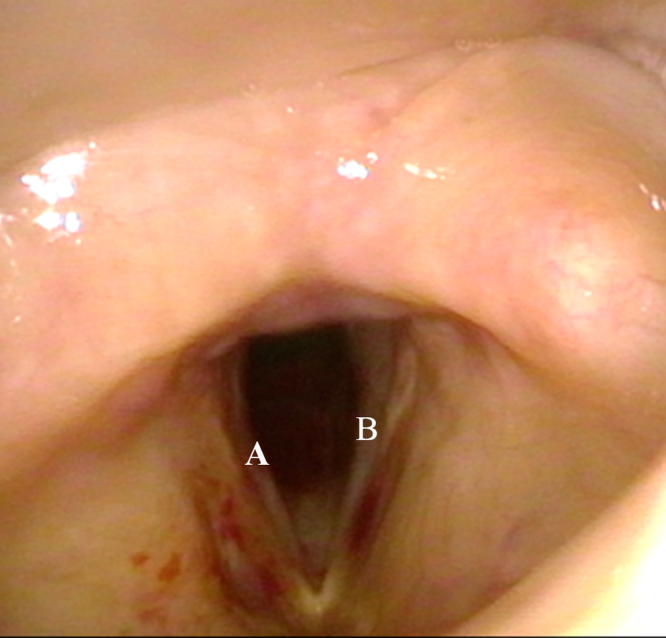

On examination, she was apyrexial and haemodynamically stable. There was audible biphasic stridor at rest, but she was able to count up to 10 in a single breath with no respiratory distress. The cardiopulmonary assessment was unremarkable. Flexible nasopharyngolaryngoscopy revealed a bulky right false cord covering part of the true cord, with limited mobility of the right vocal cord, and severe bilateral subcordal edema narrowing the airway (Fig. 1). Her nasal and oral cavities were normal. Her Voice Handicap Index-10 (VHI-10) score was of 24/40 and Eating Assessment Tool-10 (EAT-10) score of 20/40 which were abnormal.

Fig. 1.

This figure shows an image of MRI of the patient’s neck in coronal view depicting thickened right false cord, true cord and aryepiglottic fold (arrowed).

The haematological assessment was normal with the exception of microcytic hypochromic anaemia with haemoglobin of 9.0 g/dl. The immunological screening was negative of ANA, ANCA, rheumatoid factors and complement 3 and 4 proteins. Radiological imaging showed unremarkable chest x-ray findings whilst Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) of the neck showed thickening of the right false cord, true cord and aryepiglottic fold, with edema of the subglottis, consistent with our scope findings (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

This figure shows an endoscopic view of the patient’s larynx via flexible nasopharyngolaryngoscopy depicting a firm mass (A) on the right false cord with bilateral subcordal edema (B). The left true cord is visualised (C).

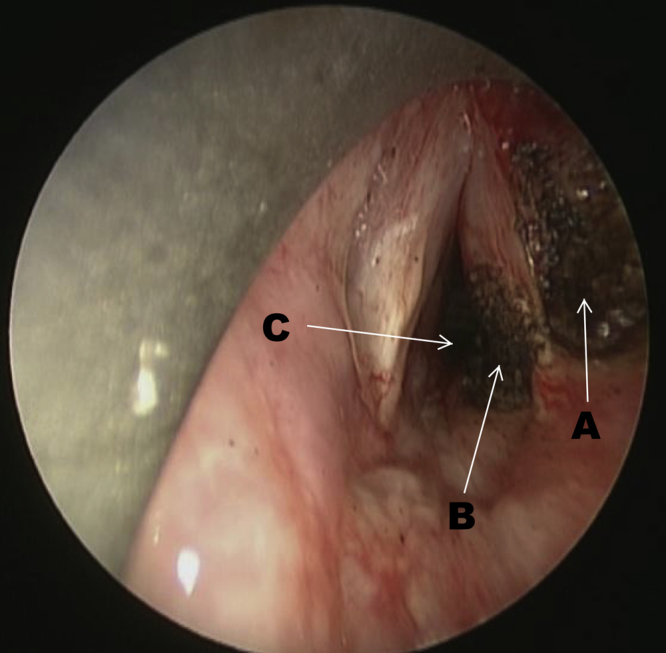

She underwent an endolaryngeal microsurgery under general anaesthesia. Intra-operatively there was a firm mass arising from the right ventricle extending into the right paraglottic space (Fig. 2). The right subcordal mass was ablated using a carbon dioxide laser and subsequently dilated up to 30 French Bougie to improve the airway (Fig. 3). Despite this, the patient developed a worsening inspiratory stridor with tachypnoea on extubation six hours post-procedure necessitating an emergency tracheostomy.

Fig. 3.

This figure shows an endoscopic view of the patient’s larynx via direct laryngoscopy depicting the appearance after carbon dioxide laser biopsy of the right false cord mass (A), laser ablation of the right subcordal edema (B) and dilatation of the subcordal region (C).

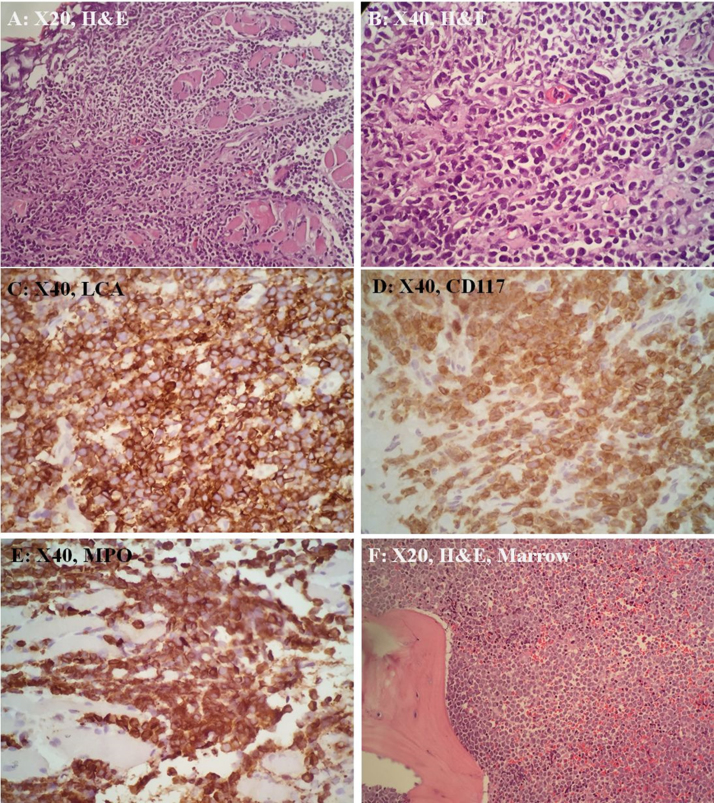

Histological examination of the right false cord and paraglottic masses showed sheets of small to medium-sized neoplastic cells infiltrating the muscle fibres. The neoplastic cells display round to oval nuclei with finely-dispersed chromatin, inconspicuous nucleoli and scanty cytoplasm. Immunohistochemically, the neoplastic cells are immunoreactive for LCA (strong and diffuse), MPO (strong and diffuse) and CD117, and they are negative for CKAE1/AE3, CD20, Cd79a, CD3, CD34 and TdT (Fig. 4). She was then investigated for myeloproliferative disease in which bone marrow biopsy and trephine confirmed a primary AML. She had received chemotherapy with High Dose Cytosine Arabinoside (HiDAC) protocol. After a cycle of chemotherapy, the mass on the right false cord and bilateral severe subcordal edema were not visualised on a repeat flexible scope (Fig. 5). She developed neutropenic sepsis and invasive pulmonary aspergilosis. Repeat bone marrow biopsy showed refractory AML. She passed away several months later. This work has been reported in line with the CARE criteria [8].

Fig. 4.

(A, B) The tissue is infiltrated by sheets of small to medium sized dyscohesive neoplastic cells. The neoplastic cells display round to oval nuclei with finely-dispersed chromatin, inconspicuous nucleoli and scanty cytoplasm. These cells are immunoreactive toward LCA (C), CD117 (D) and MPO (E). Bone marrow trephine biopsy also showed neoplastic cells infiltration that displays similar morphology (F).

Fig. 5.

This figure shows an endoscopic view of the patient’s larynx via flexible nasopharyngolaryngoscopy depicting a clear view of the vocal cords with no subcordal edema and resolved right ventricle mass after completion of the first cycle of chemotherapy. The right(A) and left (B) true cord are visualized.

3. Discussion

This case reports a 44-year-old lady with no history of AML, myelodysplastic syndromes or systemic diseases was unexpectedly diagnosed with MS of larynx as per histopathology and immunohistochemistry examination. MS are relatively uncommon, and laryngeal involvement is even more so, thus it is important for otolaryngologists to be aware of the possible presenting symptoms, site of involvement and management of these tumours. We identified only nine cases being reported between 1954 until 2015 by using PubMed and MEDLINE search with keywords of ‘myeloid, sarcoma, larynx’. Presenting symptoms and signs, and treatments delivered to these patients are summarised in Table 1. However, only five cases were tabled as the remaining four cases described the disease per se, omitting symptoms and signs.

Table 1.

This table shows summary of 5 cases being reported with the keyword of ‘myeloid; sarcoma; larynx’ in PubMed/Medine search.

| Cases | History at presentation | Clinical features | Definitive treatment |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | On remission | 37, male. Dysphagia and hoarseness Multiple unilateral lower cranial nerve paralysis—IX, X, XII. Multiple masses involving larynx and nasopharynx |

Chemotherapy Outcome: patient died due to pulmonary infection on day 17 of chemotherapy |

| 2 | No history | 32, male. Hoarseness Ulcerative mass on left laryngeal surface of epiglottis, aryepiglottic fold and vocal cord with immobile left vocal cord |

Chemotherapy Outcome: patient died 2 months after commencement of chemotherapy |

| 3 | Relapsed 3 months post radiation | 57, male. Respiratory distress, requiring tracheostomy Right laryngeal mass involving true and false vocal cords and subglottis that was partially occluding the airway |

Radiation therapy of 24 Gy in 12 fractions Outcome: disease free for 3 months, subsequently sufferred systemic progression and not fit for additional systemic therapies, and passed away several weeks later |

| 4 | No history | 36, male. Dysphagia, hoarseness and stridor requiring tracheostomy. Submucosal mass on right false cord partially obstructing the airway |

Induction chemotherapy followed by consolidation chemotherapy Outcome: developed recurrence of disease despite completion of chemotherapy treatment |

| 5 | CML detected by bone marrow aspiration | 50, male. Hoarseness and worsening sore throat Clinical findings not documented |

Treatment and outcome were not reported |

Of the five cases being shown in Table 1, majority of patients do not have underlying medical illness. All patients presented with symptoms of hoarseness, two of them complicated with respiratory distress requiring an emergency tracheostomy for obstruction relieve. Three of the five cases underwent chemotherapy and one underwent radiotherapy. However, most of the patients passed away due to disease progression or suffered from systemic infection. To our knowledge, this case report is the second case that presented de novo with upper airway obstruction (Table 2).

Table 2.

This table shows treatment approach for MS obtained from Vishnu et al. with permission [15].

| Disease status | Suggested treatment approach |

|---|---|

| Isolated GS GS with bone marrow involvement Relapsed isolated GS after chemotherapy Relapsed GS and bone marrow disease after chemotherapy Relapse of isolated GS after AHSCT Relapse of concurrent GS and bone marrow disease after AHSCT |

Chemotherapy followed by surgery/radiation treatment Chemotherapy with consideration for AHSCT Chemotherapy followed by AHSCT Chemotherapy followed by AHSCT Donor lymphocyte infusion, tapering of immunosuppression if tolerated, or investigational agent versus palliative IDRT Investigational agents versus best supportive care |

Abbreviations: AHSCT; allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant; GS, granulocytic sarcoma; IFRT, involved-field radiotherapy.

MS is often misdiagnosed as the common alternative diagnosis of being either a lymphoma or undifferentiated carcinoma [9]. Misdiagnosis may be due to an incomplete work-up which may be misleading because T-cell or B-cell lymphoma and MS share similar morphologic patterns and both express leucocyte specific antigens [6].

The best definitive diagnosis is via immunohistochemistry and immunophenotyping. According to WHO 2008 classification, cytochemical stains should be myeloperoxidase (MPO), lymphocyte common antigen (LCA) and CD117 [10]. CD 117 and MPO are the most common markers in flow cytometric analysis in tumours to have a strong positive staining with myeloid differentiation. Our patient showed a strong positive staining to LCA, MPO and CD 99 with positive CD 68 and CD 117 over the focal granular region. These malignant cells also show a high proliferative index of Ki67 being over 80%. Other common markers are CD68/PG-M1, CD34, terminal-deoxy-nucleotidyl-transferase, CD56, CD61, CD30 and CD4 [11].

Treatment options depends upon patient, tumour factors and disease characteristics. There are several important factors for consideration, which includes the patient’s age, associated medical comorbidities, clinical symptoms, tumour type and stage and lastly, the extent of the disease involvement. Treatments employed for MS are chemotherapy (either systemic or intrathecal), radiotherapy, surgical excision or a combination of these interventions (Table 1).

Literature review suggests that current treatment options are conventional chemotherapeutic protocol for AML [5]. Tsimberidou et al. showed reduction in rate of progression to AML in isolated MS patients receiving systemic chemotherapy by 42% compared to patients receiving tumour localized treatment [12]. Isolated MS patients treated with AML based induction regimens have been reported to share similar prognostic features and prolonged disease-free interval [13].

Literature review is lacking evidence for a definite form of chemotherapeutic regime in treating MS. More data is required on the efficacy of specific chemotherapeutic regime used and follow up in term of prognostic factors and disease free survival period. Radiotherapy is often given concurrently with systemic chemotherapy although its role is not well established. Tsimberidou et al. found no difference on survival rate in isolated MS patients treated with radiotherapy in addition to chemotherapy or chemotherapy as a standalone [12]. Another recent article by Hoover et al., reported that MS is generally radiosensitive. The authors recommended treatment of minimum 20 Gy and proposed a regime of 24 Gy over 12 fractions as an appropriate treatment course for laryngeal MS [2].

The overall prognosis is poor in patients who were diagnosed with myeloid sarcoma with 53% mortality rate and an average life expectancy of patients with AML diagnosed with MS is less than 12 months [14]. This was seen is our patient. A retrospective study of 51 patients with myeloid sarcoma, either isolated or associated with AML showed a 5-year overall survival rate of 48%, with no significant differences in outcomes between the two presentations [15].

4. Conclusion

This case report and literature appraisal can conclude four main points. Firstly, laryngeal MS is of rare occurrence and may be asymptomatic of haematological manifestations. Early recognition for laryngeal MS is key with high suspicions amongst patients presenting with haematological disorders. Secondly, MS responds more favourably to systemic chemotherapy with or without radiotherapy compared to surgical treatment alone. Thirdly, the role of surgical treatment in laryngeal MS is mainly for biopsy and relieve of upper airway obstruction. Lastly, MRI of the larynx may not be specific but may be useful in diagnosis.

Author contribution

Concept—Tan Shi Nee, Hardip Singh Gendeh.

Design—Tan Shi Nee, Hardip Singh Gendeh, Marina Mat Baki.

Supervision—Marina Mat Baki, Sani A.

Materials—Marina Mat Baki, Sani A.

Data collection and/or processing—Tan Shi Nee, Hardip Singh Gendeh, Marina Mat Baki.

Literature review—Tan Shi Nee, Hardip Singh Gendeh, Marina Mat Baki.

Writer—Tan Shi Nee, Hardip Singh Gendeh, Marina Mat Baki.

Critical review—Marina Mat Baki, Sani A.

Funding

There is no funding source for this case report.

Ethical approval

There is no ethical approval for this case report.

Consent

Informed consent was obtained for this case report from the next of kin. Consent was obtained prior to any diagnostic or treatment procedures.

Guarantor

Marina Mat Baki.

Conflicts of interest

There is no conflict of interest for this case report.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Professor Dr. Tan G.C., histopathologist of Department of Histopathology, University Kebangsaan Malaysia Medical Centre (UKMMC), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia for his input on the histopathology report of this patient. Also to the staffs of the Department of otorhinolaryngology, Head & Neck Surgery for their contributions to this manuscript.

References

- 1.Schultz J., Shay H., Gruenstein M. The chemistry of experimental chloroma I. Porphyrins and peroxidases. Cancer Res. 1954;14:157–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoover A.C., Anderson C.M., Hoffman H.T., De Magalhaes Silverman M., Syrbu S.I., Smith M.C. Laryngeal chloroma heralding relapse of acute myeloid leukemia. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014;32(7):18–21. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.47.0047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dock G. Chloroma and its relation to leukemia. Am. J. Med. Sci. 1893;106(2):153–157. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paydas S., Zorludemir S., Ergin M. Granulocytic sarcoma: 32 cases and review of the literature. Leuk. Lymphoma. 2006;47(12):2527–2541. doi: 10.1080/10428190600967196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Avni B., Rund D., Levin M. Clinical implications of acute myeloid leukemia presenting as myeloid sarcoma. Hematol. Oncol. 2012;30:34–40. doi: 10.1002/hon.994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Byrd J.C., Edenfield W.J., Shields D.J., Dawson N.A. Extramedullary myeloid cell tumors in acute nonlymphocytic leukemia: a clinical review. J. Clin. Oncol. 1995;13:1800–1816. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.7.1800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Horny H.P., Kaiserling E. Involvement of the larynx by hemopoietic neoplasms: an investigation of autopsy cases and review of the literature. Pathol. Res. Pract. 1995;191:130–138. doi: 10.1016/S0344-0338(11)80562-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gagnier J.J., Kienle G., Altman D.G., Moher D., Sox H., Riley D. The CARE guidelines: consensus-based clinical case reporting guideline development. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013(October (23)) doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-7-223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vardiman J.W., Thiele J., Arber D.A. The 2008 revision of the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia: rationale and important changes. Blood. 2009;114(5):937–951. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-209262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pileri S.A., Ascani S., Cox M.C., Campidelli C., Bacci F., Piccioli M. Myeloid sarcoma: clinico-pathologic, phenotypic and cytogenetic analysis of 92 adult patients. Leukemia. 2007;21(2):340–350. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lan T.Y., Lin D.T., Tien H.F., Yang R.S., Chen C.Y., Wu K. Prognostic factors of treatment outcomes in patients with granulocytic sarcoma. Acta Haematol. 2009;122(4):238–246. doi: 10.1159/000253592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tsimberidou A.M., Kantarjian H.M., Wen S., Keating M.J., O'Brien S., Brandt M. Myeloid sarcoma is associated with superior event-free survival and overall survival compared with acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer. 2008;113(6):1370–1378. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim L.Y., Purkey M.T., Patel M.R., Ghosh A., Hartner L., Newman J.G. Primary granulocytic sarcoma of larynx. Head Neck. 2015;37(3):38–44. doi: 10.1002/hed.23805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chevallier P., Mohty M., Lioure B. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation for myeloid sarcoma: a retrospective study from the SFGM-TC. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008;26(30):4940–4943. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.6315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vishnu P., Chuda R.R., Hwang D.G., Aboulafia D.M. Isolated granulocytic sarcoma of the nasopharynx: a case report and review of the literature. Int. Med. Case Rep. J. 2013;7:1–6. doi: 10.2147/IMCRJ.S53612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]