Highlights

-

•

In every patient diagnosed with a tumoral lesion, the possibility of a second primary tumor should be considered.

-

•

Patients with thymoma are more likely to experience extrathymic neoplasms and the incidence of extrathymic cancers is increased both before and after the diagnosis of thymoma.

-

•

Symptoms and signs unrelated to a diagnosed primary tumor should be carefully assessed for a possible concurrent neoplasm.

-

•

Treatment decisions for a patient with double primary tumor should be individualised and the lesion with more life-threatening outcome should be treated first.

-

•

Simultaneous operation for two primary malignant tumors in different anatomic regions is not generally recommended.

Keywords: Mediastinal tumor, Thymoma, Brain tumor, Double malignancy

Abstract

Introduction

Patients with thymoma are found to have another systemic illness and a broadly increased risk for secondary malignancies. We present the case of a 53-year-old female patient who harbored two synchronous primary malignant neoplasms—an anaplastic oligodendroglioma of the right frontal lobe and an anterior mediastinal thymoma.

Presentation of case

A 53-year-old female patient presented in her first hospital admission with nausea, chest pain and non-pulsatile bitemporal headache. Continued headache and nausea along with negative cardiac findings prompted radiological evaluation including chest CT scan and brain CT scan which revealed simultaneous anterior mediastinal mass and frontal lobe calcification respectively. The patient underwent craniotomy and the pathological diagnosis was anaplastic oligodendriglioma. The anterior mediastinal tumor resection was performed three months later, while the patient had no newly onset of any symptoms necessitating more investigation.

Discussion

Multiple primary malignancies have been diagnosed by the following criteria: each tumor must have an obvious picture of malignancy, each must be separate and discrete and the probability that one was a metastatic lesion from the other must be excluded. Treatment strategies in cases of double malignancy involve treating the malignancy that is more advanced first. In our case we concluded that synchronous double malignancy can be treated successfully according to the above mentioned criteria.

Conclusion

Clinicians should be aware of the possibility of synchronous malignancies in order to use screening procedures in patients with reported increased risk of double malignancy. Such clinical alertness may lead to a better outcome for double primary tumor cases.

1. Introduction

Patients with thymoma are found to have another systemic illness and a broadly increased risk for cancer. The secondary malignancies that have been described in these patients include both common cancers (e.g., cancers of the lung, thyroid, and prostate, and lymphomas) and rare malignancies (e.g., brain tumors, sarcomas, and leukemias). We present a patient who harbored two uncommon synchronous primary malignant neoplasms—an anaplastic oligodendroglioma and an anterior mediastinal thymoma. The purpose of this article is to increase the awareness of the clinicians to this possibility in order to use screening procedures in patients with reported increased risk of double malignancy.

2. Presentation of case

A 53-year-old female patient presented in her first hospital admission with nausea, chest pain and non-pulsatile bitemporal headache. The patient while consuming aspirin, atenolol and atorvastatin was a non-smoker without any other underlying disease or addiction except hypertension and had normal physical examination and laboratory tests. The primary presumed diagnosis was acute coronary syndrome leading to cardiac evaluation which proved to be normal. There was no family history of any disease and the patient had an acceptable lifestyle with no anxiety or depression or any other psychiatric disorder. Continued headache and nausea along with controlled hypertension and negative findings in other organ systems prompted neurologist consultation with a suspected intracranial lesion.

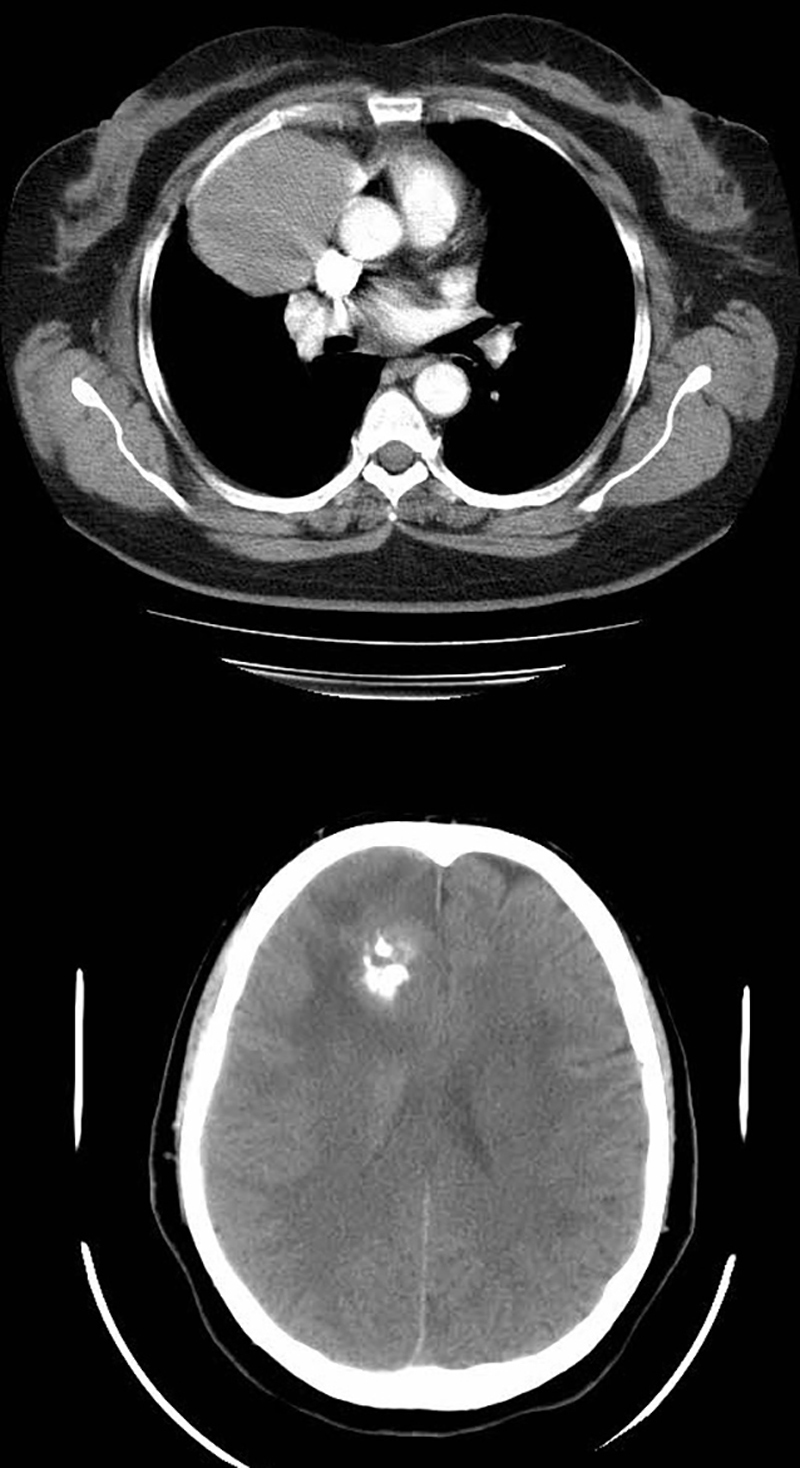

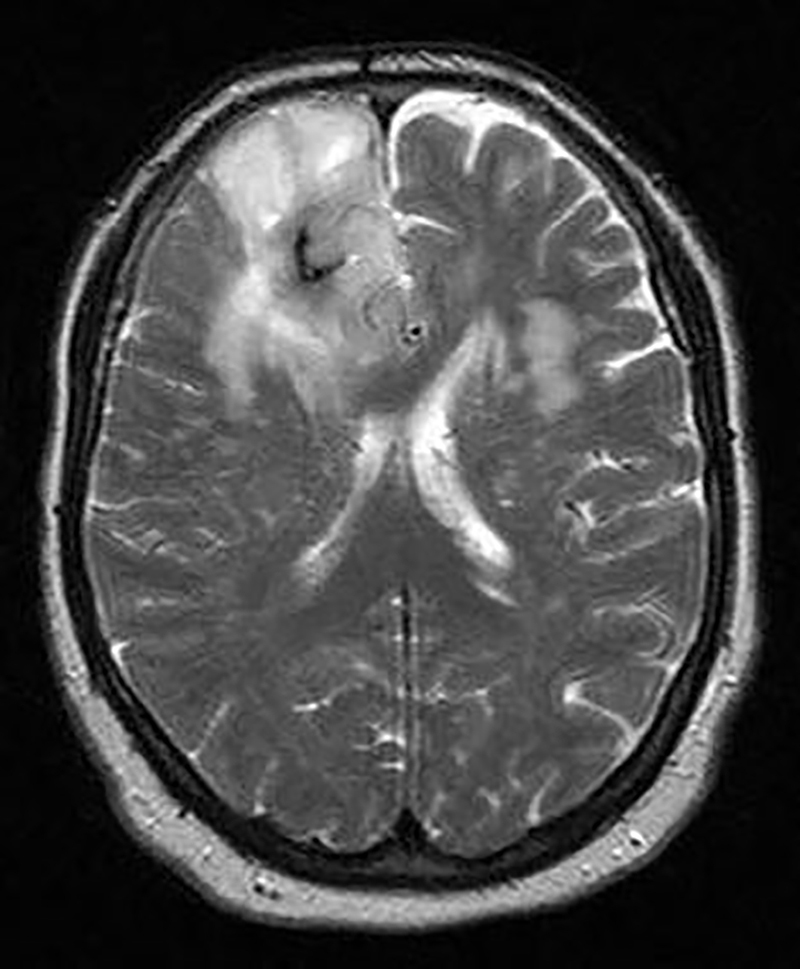

The radiological evaluation including chest CT scan and brain CT scan revealed simultaneous anterior mediastinal mass and frontal lobe calcification respectively (Fig. 1). Abdominal–pelvic CT scan was also performed which was normal. Further assessment including brain MRI and more complete neurologic exam showed a frontal lobe mass (Fig. 2) and normal muscles force, reflexes, cranial nerves function and no gait disturbance. CT-guided biopsy of the mediastinal mass was reported highly suggestive for thymoma and further evaluation revealed no evidence of myasthenia gravis or gastro-intestinal disorder and also a normal thyroid function test. Plasma and urinary cathecolamines and their metabolites were also negative.

Fig. 1.

Chest CT scan and brain CT scan show a well-defined anterior mediastinal mass with no adjacent tissues invasion and frontal lobe calcification respectively.

Fig. 2.

Brain MRI shows a frontal lobe mass.

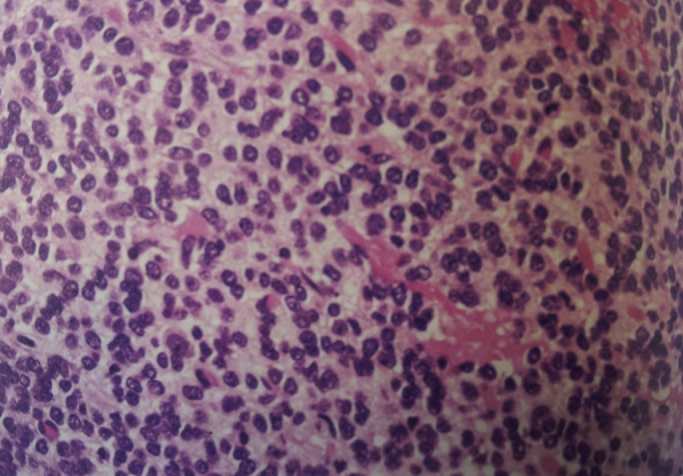

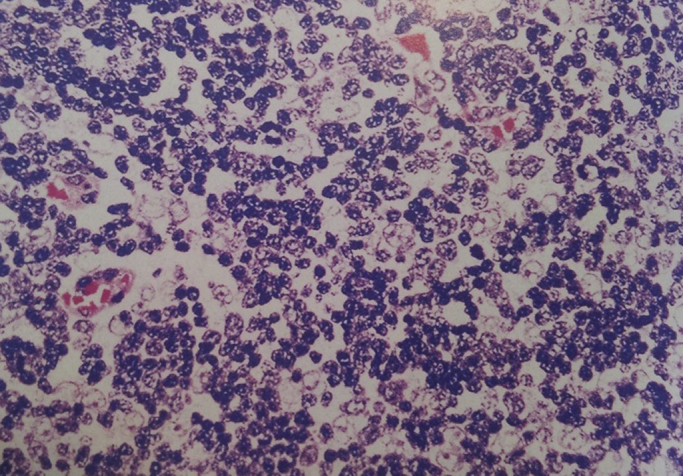

The patient underwent craniotomy with no post-operative complication and the pathological diagnosis was anaplastic oligodendriglioma WHO grade III with multiple areas of calcification. By immunohistochemistry, the tumoral cells were positive for glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) and negative for CD 45, CD 20 and CD 3. MIB-I index were about 20% (Fig. 3). The anterior mediastinal tumor resection via median sternotomy was performed three months later, while the patient had no newly onset of any symptoms necessitating more investigation. The completely resected tumor had no surrounding structures invasion or metastases. Pathological diagnosis was a grossly and microscopically encapsulated 10 × 11 × 6 cm thymoma (type B2) (Fig. 4). The adjuvant treatment for anaplastic oligodendroglioma included about 30 sessions of radiotherapy plus chemotherapy according to the oncologist discretion. The patient has undergone a regular follow-up for one year with no recurrence or any other complication or new lesion in her latest brain and chest CT Scan. (Fig. 5).

Fig. 3.

Pathological diagnosis of anaplastic oligodendriglioma WHO grade III.

Fig. 4.

Mixed lymphoepithelial thymoma WHO type B2, composed of admixures of thymic epithelial cells and small lymphocytes.

Fig. 5.

Post-operative brain and chest CT Scan (one year later) which shows no recurrence or new lesion.

3. Discussion

Patients with thymoma are found to have another systemic illness including myasthenia gravis, pure red cell aplasia, hypogammaglobulinemia, polymyositis, systemic lupus erythematosus, thyroiditis, Sjogren’s syndrome, ulcerative colitis, pernicious anemia, Addison’s disease, scleroderma, and panhypopituitarism. In addition, patients with thymoma are more likely to experience extrathymic neoplasms and the incidence of extrathymic cancer is increased both before and after the diagnosis of thymoma.

Moertel [1] in his study of 37,580 cases of malignant disease, reported multiple primary malignant tumors in 10.6% of autopsy cases and 4.6% of surgical cases. Multiple primary malignancies have been diagnosed by the following criteria: each tumor must have an obvious picture of malignancy, each must be separate and discrete and the probability that one was a metastatic lesion from the other must be excluded.

Engels and Pfeiffer [2] in a 2003 study, used SEER data to assess cancer incidence in 733 U.S. thymoma patients relative to the general population. Secondary malignancies occurred in 66 (9%) thymoma patients. Specific malignancies for which thymoma patients had an increased risk included cancers of the digestive system as a group, non-Hodgkin lymphoma and soft tissue sarcomas.

Masaoka et al. [3] reported a series of 392 patients who required thymectomy for myasthenia gravis; 102 patients had thymomas of which nine patients were later diagnosed by another malignancy. Welsh et al. [4] reported that 28% of 136 patients with thymoma acquired extrathymic cancers. The most common extrathymic cancer in their series was colorectal carcinoma. Pan et al. [5] reported a series of 192 patients with thymoma from Taiwan. The incidence of extrathymic neoplasm was 8%, and the most common tumor was gastric adenocarcinoma. Two patients had extrathymic tumors before the diagnosis of thymoma. The secondary malignancies that have been described in these patient series includes both common cancers (e.g., cancers of the lung, thyroid, and prostate, and lymphomas) and rare malignancies (e.g., brain tumors, sarcomas, and leukemias). Overall cancer risk has been estimated to be 3–4 times higher in thymoma patients than in controls.

Malignant brain tumors are among the most distressful types of cancer, not only for their poor prognosis, but also because of the direct consequences on quality of life and cognitive function.

Some of the rare hereditary syndromes are associated with an increased risk of glioma, including Cowden, Turcot, Li-Fraumeni, neurofibromatosis type 1 and type 2, tuberous sclerosis, and familial schwannomatosis. Ionizing radiation is a recognized environmental risk factor for glioma development [6]. Our patient was not affected by any of the above-mentioned diseases. Cerebral malignant gliomas rarely show extracranial metastases. In the literature, several anecdotal cases of dissemination to the bone, leptomeninges, scalp, lymph–node, spine, bone marrow, liver, peritoneum, parotid gland, lung, spleen and pancreas from oligodendroglioma have been reported. The anaplastic variant showed the most frequent tendency to metastasize. Our patient with simultaneous double malignancy had no evidence of metastatic lesion.

Treatment strategies in cases of double malignancy generally involve treating the malignancy that is more advanced first. In our case we concluded that synchronous double malignancy may be treated successfully and both sites should be treated fully as if they were occurring separately.

4. Conclusion

Clinicians should be aware of the possibility of synchronous malignancies in order to use screening procedures in patients with reported increased risk of double malignancy. Such clinical alertness may lead to a better outcome for double primary tumor cases.

Conflict of interest

No conflict of interest.

Sources of funding

No funding recieved.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval issued by the "Research Integrity Evaluation Committee" of the corresponding hospital.

Consent

Patient's informed written consent has been obtained.

Author contribution

Dr. Mohammad Vaziri: Study concept, data analysis, writing the paper.

Dr Kamelia Rad: Data collection.

Guarantor

Dr. Mohammad Vaziri.

References

- 1.Moertel C.G. Multiple primary malignant neoplasms historical perspectives. Cancer. 1977;40:1786–1792. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197710)40:4+<1786::aid-cncr2820400803>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Engels E.A., Pfeiffer R.M. Malignant thymoma in the United States: demographic patterns in incidence and associations with subsequent malignancies. Int. J. Cancer. 2003;105:546–551. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Masaoka A., Yamakawa Y., Niwa H., Fukai I., Saito Y., Tokudome S. Thymectomy and malignancy. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 1994;8:251–253. doi: 10.1016/1010-7940(94)90155-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Welsh J.S., Wilkins K.B., Green R., Bulkley G., Askin F., Diener-West M. Association between thymoma and second neoplasms. JAMA. 2000;283:1142–1143. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.9.1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pan C., Chen P.C., Wang L., Chi K., Chiang H. Thymoma is associated with an increased risk of second malignancy. Cancer. 2001;92:2406–2411. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20011101)92:9<2406::aid-cncr1589>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Omuro A., DeAngelis L.M. Glioblastoma and other malignant gliomas: a clinical review. JAMA. 2013;310:1842–1850. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.280319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]