Highlights

-

•

Pseudoaneurysms occur when there is a partial disruption in the wall of a blood vessel.

-

•

Most pseudoaneurysms of the maxillary artery develop on the terminal pterygopalatine segment.

-

•

Endovascular embolization can be used successfully to treat a pseudoaneurysm

Keywords: Pseudoaneurysm, Facial trauma, Internal maxillary artery, Gunshot, Endovascular embolization

Abstract

Introduction

Pseudoaneurysms occur when there is a partial disruption in the wall of a blood vessel, causing a hematoma that is either contained by the vessel adventitia or the perivascular soft tissue.

Presentation of case

A 32-year-old male presented to the emergency department presented with comminuted fractures in the left zygoma, ethmoids, and the right ramus of the mandible following a gunshot wound. The patient underwent open reduction of his fractures and the patient was discharged on the eighth day after the trauma. Thirteen days after the discharge and 21 days after the gunshot wound, the patient returned to the ER due to heavy nasopharyngeal bleeding that compromised the patency of the patient’s airways and caused hemodynamic instability. Arteriography of the facial blood vessels revealed a pseudoaneurysm of the maxillary artery. Endovascular embolization with a synthetic embolic agent resulted in adequate hemostasis, and nine days after embolization the patient was discharged.

Discussion

The diagnosis of pseudoaneurysm is suggested by history and physical examination, and confirmed by one of several imaging methods, such as CT scan with contrast. Progressive enlargement of the lesion may lead to several complications, including rupture of the aneurysm and hemorrhage, compression of adjacent nerves, or release of embolic thrombi.

Conclusion

This case reports the long-term follow up and natural history of a patient with a post-traumatic pseudoaneurysm of the internal maxillary artery and the successful use of endovascular embolization to treat the lesion.

1. Introduction

Pseudoaneurysms occur when there is a partial disruption in the wall of a blood vessel, causing a hematoma that is either contained by the vessel adventitia or the perivascular soft tissue. The risk of rupture of a pseudoaneurysm is much higher than that of a true aneurysm, as there is less support from the vessel wall. They may be formed in proximity to, or at the site of, post-traumatic damage to arterial walls. They can be difficult to diagnose, especially when the compromised blood vessel obscures the defect. This paper presents the case of a patient with a diagnosis of a pseudoaneurysm of the maxillary artery following facial trauma, with recurrent bleeding after orthognathic surgery 6 years after the trauma, and long-term follow up.

2. Presentation of case

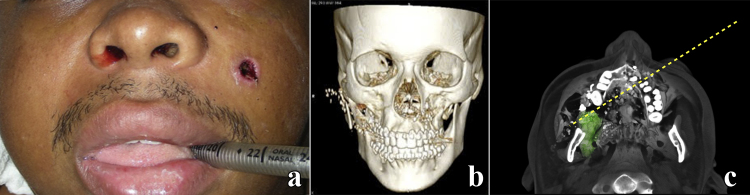

A 32-year-old gunshot wound victim was brought to the emergency department at the Hospital das Clínicas, FMUSP (School of Medicine, São Paulo University). The bullet entered the left malar region in the mid-pupillary line, five millimeters above the nasolabial fold, and exited via the right preauricular region, about two millimeters in front of the lobule (Fig. 1a). The patient had no significant medical or surgical history. There was no active bleeding, though the patient had a small amount of blood in the nostrils and a swollen, ecchymotic hard palate. There were no sensory or other neurologic deficits. The patient’s heart rate was 93 beats per minute and blood pressure was 150/80 mmHg. A CT angiogram of the head and neck showed an Ozyazgan Type II-A fracture of the left zygoma [1], as well as comminuted fractures of the ethmoids and the right ramus of the mandible (Fig. 1b). The contrast study did not reveal any damage to the large blood vessels. On the primary admission, the patient had a significant episode of epistaxis that resulted in a drop in hemoglobin from 11.0 g/dl to 6.6 g/dl. This required treatment by anterior and posterior nasal packing and transfusion of three units of packed red blood cells. After the bleeding was controlled, maxilla-mandibular movement was restricted with an Erich arch bar prior to an open surgical repair of the fractures. Additional angiography showed no further evidence of bleeding or damage to the large vessels. The patient was discharged on the eighth day after the trauma.

Fig. 1.

Preoperative images of the patient’s trauma including photographic (a), a three-dimensional projection of the CT scan (b), and a composite image showing the path of the bullet in yellow and the area that developed the pseudoaneurysm in green (c).

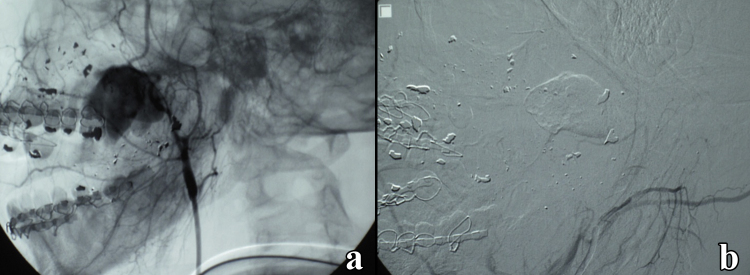

Thirteen days after the discharge and 21days after the gunshot wound, the patient returned to the ER due to heavy nasopharyngeal bleeding that compromised the patency of the patient’s airways and caused hemodynamic instability. On admission, the patient’s heart rate was 120 beats per minute and blood pressure was 110/60 mmHg. On physical examination, swelling was noted in the right preauricular region, near the exit wound of the bullet. The patient underwent an urgent cricothyroidotomy and temporary control of the bleeding was achieved via direct compression on the palate at the focus of the bleeding. The patient’s hemoglobin concentration was 7.4 g/dl with a hematocrit of 23.6%. After definitive stabilization of the airway and hemodynamic stabilization with 1000 ml of normal saline solution and two units of packed red blood cells, arteriography of the facial blood vessels was performed, which revealed a pseudoaneurysm of the maxillary artery (Fig. 2a). Selective catheterization of the maxillary artery and embolization by a synthetic embolic agent (Enbucrilate) resulted in adequate hemostasis (Fig. 2b), and nine days after the embolization the patient was discharged.

Fig. 2.

Angiography of the pseudoaneurysm of the internal maxillary artery, before (a) and after (b) embolization.

The patient returned 6 years following the trauma, for a LeFort I osteotomy with a bilateral sagittal split osteotomy for maxillary advancement and correction of lateral deviation, due to a class III malocclusion and an anterior open bite. The patient noted a new diagnosis of hypertension controlled with 50 mg of captopril twice daily. The surgery was performed carefully and without complications. The patient’s post-operative course was uncomplicated, and the patient was discharged in great condition on post-operative day 6. However, the patient returned to the emergency department with a nosebleed on post-operative day 8. He was bleeding profusely from his nose, and hypertensive to 160/90. There were no signs of bleeding into his oropharynx on oroscopy. The patient received anterior nasal packing and received an additional dose of captopril 50 mg for his hypertension. No additional imaging was performed, as the patient was hemodynamically stable, showed no hemostatic irregularities, and the bleeding was controlled with nasal packing. The patient was monitored carefully for the return of any significant bleeding, and was eventually discharged on post-operative day 13. The patient was examined in the clinic 17 months after the orthognathic surgery and over 7 years after the trauma with good occlusion, no reoccurrence of nasal bleeding, and excellent satisfaction with his surgery.

This case has been reported in line with the CARE criteria [2].

3. Discussion

Pseudoaneurysms, or traumatic aneurysms, are different from true aneurysms because they involve the disruption the inner layers of an artery after blunt, penetrating or even surgical trauma [3], [4], [5]. They also may occur in disruptions of all three vascular layers, if the original hematoma is tamponaded by the surrounded soft tissue. In penetrating trauma, as reported in this case, the usual mechanism is high velocity maxillofacial trauma, in which bone or projectile fragments lead to arterial laceration [5], [6], [7], [8]. In several weeks, the formed hematoma starts to liquefy in the center, producing a cavity and that develops a pseudointima on the outer wall. As the process evolves, the pseudoaneurysm starts to pulsate and enlarges progressively [3], [4], [7] .Pseudoaneurysms most commonly occur after arterial catheterization, with the inadequate manual compression as the most common etiology [9]. However, in craniofacial trauma, where non-transecting arterial injuries may not be evident on primary physical exam or vascular imaging, manual compression is impossible. The three branches of the external carotid system most vulnerable to pseudoaneurysms are the superficial temporal, facial and maxillary artery [6], and most pseudoaneurysms of the maxillary artery develop on the terminal pterygopalatine segment [10]. The progressive enlargement of the lesion may lead to several complications, including rupture of the aneurysm and hemorrhage [3], [11], compression of adjacent nerves [12], or release of embolic thrombi [13].

The diagnosis is suggested by history and physical examination, and confirmed by one of several imaging methods, such as CT scan with contrast. This imaging modality was recommended as it shows anatomic details of vascular injuries with a high degree of definition [14]. Another suggestion is the use of Doppler ultrasound for lesions in which the vascular nature is unknown. Ultrasound is advantageous for an initial screening because it is quick, involves no radiation and is cost-effective.

All imaging methods that reveal a potential pseudoaneurysm should be followed by angiography, to allow the visualization of the vascular architecture. In this case, the angiography was not immediately performed, because the anterior and posterior nose packing were effective to stop the bleeding. Management by anterior nasal packing is the correct emergency maneuver to be performed in cases of post-operative hemorrhage following maxillary osteotomy [15]. Additionally, the episode of bleeding following this patient’s orthognathic surgery is unlikely to be a pseudoaneurysm. Post-orthognathic bleeding is a relatively common complication [16], while pseudoaneurysms are much rarer. This post-orthognathic bleeding may be caused by a tear in the mucosa or the internal maxillary artery and terminal branches [15], [17], [18].

The initial treatment for life-threatening hemorrhages following orthognathic surgery should include direct compression and hemostasis followed by blood transfusion, if necessary, to stabilize the patient. All patients should be counseled about the possibility of a post-operative bleed and should be instructed on how to release the maxillo-mandibular fixation to clear potential clots [15]. Once in the hospital, anterior and posterior nasal packs should be placed for direct compression. In any circumstance where the airway is compromised, a tracheostomy should be considered [15]. Further diagnostic work-up should continue once the patient is hemodynamically stable.

Small pseudoaneurysms can be treated with simple compression or ultrasound-guided thrombin or collagen injections, though this may be more difficult and dangerous with pseudoaneurysms of the facial vessels [19]. Emergent surgical ligation of the maxillary artery has previously been performed, though it is difficult and ineffective, particularly in cases of massive active bleeding [20]. Another possible management is an open surgical technique that allows direct visualization of the lesion and its resection [6], [21]. Nevertheless, endovascular embolization performed at the time of angiography has been used with increasing frequency for treatment of pseudoaneurysms because it is safe, more selective, less invasive than the surgical procedure and it can be done under sedation [22]. Yin showed the difficulty in achieving hemostasis because of the need to perform multiple ligatures to reduce blood flow on the distal segment of the maxillary artery [23]. Several permanent or temporary materials can be used in arterial embolization, including polyvinyl alcohol, Gelfoam, nickel-titanium coils and balloons [21]. Embolic material can be introduced through the catheter into the maxillary artery and its terminal branches. It is essential to use small embolic material, as the vascular occlusion should be as distal as possible within the pseudoaneurysm, while protecting the parent vessel and healthy surrounding vessels [24]. A post-embolization angiography must be performed to verify the effectiveness of the treatment. However, surgical management of a pseudoaneurysm is still preferred in cases of a necrotic aneurysm, rapid enlargement, or in the case of failed embolization [25].

4. Conclusion

This case reports the long-term follow up and natural history of a patient with a post-traumatic pseudoaneurysm of the internal maxillary artery and the successful use of endovascular embolization to treat the lesion.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Funding

None.

Ethical approval

N/A: case report, proper consent was obtained.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Author contribution

Study concept or design: NA, EB, BM.

Data collection: NA, EB, BM.

Data analysis or interpretation: NA, EB, BM.

Writing the paper: NA, EB, BM.

Guarantor

Nivaldo Alonso.

References

- 1.Ozyazgan I. A new proposal of classification of zygomatic arch fractures. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2007;65:462–469. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2005.12.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gagnier J.J. The CARE guidelines: consensus-based clinical case reporting guideline development. BMJ Case Rep. 2013:2013. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2013-201554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lanigan D.T., Hey J.H., West R.A. Major vascular complications of orthognathic surgery: false aneurysms and arteriovenous fistulas following orthognathic surgery. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 1991;49:571–577. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(91)90337-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schwartz H.C., Kendrick R.W., Pogorel B.S. False aneurysm of the maxillary artery: an unusual complication of closed facial trauma. Arch. Otolaryngol. 1983;109:616–618. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1983.00800230052012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rogers S.N. Traumatic aneurysm of the maxillary artery: the role of interventional radiology. A report of two cases. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 1995;24:336–339. doi: 10.1016/s0901-5027(05)80485-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Conner W.C., 3rd, Rohrich R.J., Pollock R.A. Traumatic aneurysms of the face and temple: a patient report and literature review, 1644 to 1998. Ann. Plast. Surg. 1998;41:321–326. doi: 10.1097/00000637-199809000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.D'Orta J.A., Shatney C.H. Post-traumatic pseudoaneurysm of the internal maxillary artery. J. Trauma. 1982;22:161–164. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198202000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krishnan D.G., Marashi A., Malik A. Pseudoaneurysm of internal maxillary artery secondary to gunshot wound managed by endovascular technique. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2004;62:500–502. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2003.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Katzenschlager R. Incidence of pseudoaneurysm after diagnostic and therapeutic angiography. Radiology. 1995;195:463–466. doi: 10.1148/radiology.195.2.7724767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Albernaz V.S., Tomsick T.A. Embolization of arteriovenous fistulae of the maxillary artery after Le Fort I osteotomy: a report of two cases. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 1995;53:208–210. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(95)90405-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crow W.N. Massive epistaxis due to pseudoaneurysm: treated with detachable balloons. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 1992;118:321–324. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1992.01880030113023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taher A.A. Traumatic external carotid artery aneurysm causing facial nerve paralysis: a case report. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 1991;20:88–89. doi: 10.1016/s0901-5027(05)80713-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Halbach V.V. Endovascular treatment of vertebral artery dissections and pseudoaneurysms. J. Neurosurg. 1993;79:183–191. doi: 10.3171/jns.1993.79.2.0183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lozman H., Nussbaum M. Aneurysm of the superficial temporal artery. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 1982;3:376–378. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0709(82)80013-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lanigan D.T., West R.A. Management of postoperative hemorrhage following the Le Fort I maxillary osteotomy. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 1984;42:367–375. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(84)80008-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim S.G., Park S.S. Incidence of complications and problems related to orthognathic surgery. J Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2007;65:2438–2444. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2007.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bell W.H. Wound healing after multisegmental Le Fort I osteotomy and transection of the descending palatine vessels. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 1995;53:1425–1433. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(95)90670-3. discussion; 1433–1434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Turvey T.A., Fonseca R.J. The anatomy of the internal maxillary artery in the pterygopalatine fossa: its relationship to maxillary surgery. J. Oral Surg. 1980;38:92–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krueger K. Postcatheterization pseudoaneurysm: results of US-guided percutaneous thrombin injection in 240 patients. Radiology. 2005;236:1104–1110. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2363040736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cannell H., Silvester K.C., O'Regan M.B. Early management of multiply injured patients with maxillofacial injuries transferred to hospital by helicopter. Br. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. 1993;31:207–212. doi: 10.1016/0266-4356(93)90140-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zachariades N. Embolization for the treatment of pseudoaneurysm and transection of facial vessels. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endod. 2001;92:491–494. doi: 10.1067/moe.2001.117453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moreau S. Supraselective embolization in intractable epistaxis: review of 45 cases. Laryngoscope. 1998;108:887–888. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199806000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yin N.T. Hemorrhage of the initial part of the internal maxillary artery treated by multiple ligations: report of four cases. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 1994;52:1066–1071. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(94)90179-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Elton V.J., Turnbull I.W., Foster M.E. An overview of the management of pseudoaneurysm of the maxillary artery: a report of a case following mandibular subcondylar osteotomy. J. Craniomaxillofac. Surg. 2007;35:52–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Webber G.W. Contemporary management of postcatheterization pseudoaneurysms. Circulation. 2007;115:2666–2674. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.681973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]