Abstract

Introduction

Despite excellent first year outcomes in kidney transplantation, there remain significant long-term complications related to new-onset diabetes after transplantation (NODAT). The purpose of this study was to validate the findings of previous investigations of candidate gene variants in patients undergoing a protocolised, contemporary immunosuppression regimen, using detailed serial biochemical testing to identify NODAT development.

Methods

One hundred twelve live and deceased donor renal transplant recipients were prospectively followed-up for NODAT onset, biochemical testing at days 7, 90, and 365 after transplantation. Sixty-eight patients were included after exclusion for non-white ethnicity and pre-transplant diabetes. Literature review to identify candidate gene variants was undertaken as described previously.

Results

Over 25% of patients developed NODAT. In an adjusted model for age, sex, BMI, and BMI change over 12 months, five out of the studied 37 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were significantly associated with NODAT: rs16936667:PRDM14 OR 10.57;95% CI 1.8–63.0;p = 0.01, rs1801282:PPARG OR 8.5; 95% CI 1.4–52.7; p = 0.02, rs8192678:PPARGC1A OR 0.26; 95% CI 0.08–0.91; p = 0.03, rs2144908:HNF4A OR 7.0; 95% CI 1.1–45.0;p = 0.04 and rs2340721:ATF6 OR 0.21; 95%CI 0.04–1.0; p = 0.05.

Conclusion

This study represents a replication study of candidate SNPs associated with developing NODAT and implicates mTOR as the central regulator via altered insulin sensitivity, pancreatic β cell, and mitochondrial survival and dysfunction as evidenced by the five SNPs.

General significance

-

1)

Highlights the importance of careful biochemical phenotyping with oral glucose tolerance tests to diagnose NODAT in reducing time to diagnosis and missed cases.

-

2)

This alters potential genotype:phenotype association.

-

3)

The replication study generates the hypothesis that mTOR signalling pathway may be involved in NODAT development.

Abbreviations: ATF6, Activated transcription factor; BMI, Body mass index; GWAS, Genome-wide association study; HLA, Human leucocyte antigen; HNF4, Hepatocyte nuclear factor 4; mTOR, Mammalian target of rapamycin; NODAT, New-onset diabetes after transplantation; PI3, Phospho-inositide 3-kinase; PPARGC1α, Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma co-activator 1 alpha; PPARy, Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma; PRDM14, PR domain zinc protein 14; SNP, Single nucleotide polymorphism

Keywords: New-onset diabetes after transplantation, single nucleotide polymorphisms, mTOR

Highlights

-

•

Oral glucose tolerance tests reduce time to NODAT diagnosis and missed cases

-

•

Biochemical testing changes genotype:phenotype association

-

•

mTOR signalling pathway may be involved in NODAT development

1. Introduction

Despite excellent first-year outcomes in kidney transplantation, there remain significant long-term complications of premature graft loss, morbidity, and mortality related to infection and cardiovascular disease. New-onset diabetes after transplantation (NODAT) is the major form of post-transplant hyperglycaemia that is associated with such complications. Thus research has focussed on preventative measures to post-transplant hyperglycaemia development, identification of those at risk in a timely manner, and investigating molecular pathways to its development.

Investigation of single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) variants offers such a strategy. A number of previous studies have investigated specific candidate gene variants, usually on the basis of prior evidence of association with type 2 diabetes in non-transplanted individuals. While some such SNPs have shown an association with NODAT, little attempt has been made to replicate findings in independent cohorts. More recently, the first genome-wide association study (GWAS) in the field has been reported [1]. In this study, NODAT was defined as the use of oral hypoglycaemics or insulin over a 12 year follow-up period, with the median time of NODAT onset of 100 months, and recent work highlights the growing momentum to use biochemical testing when identifying post-transplant hyperglycaemia [2], [3]. It is also worth noting that 25% of patients in this GWAS study were treated with a calcineurin inhibitor-free maintenance regimen. Our group has recently shown the use of biochemical definitions of post-transplant hyperglycaemia can alter the clinical phenotype-to-genotype association to such an effect that none of the eight β ‘glucotoxic’ SNPs identified in the GWAS were associated with NODAT in our cohort [4].

The purpose of this study was to validate the findings of the GWAS and other candidate NODAT SNPs investigated in the Belfast study [1], but in a prospective study of patients undergoing a protocolised, contemporary immunosuppression regimen, and using detailed serial biochemical testing to identify the development of NODAT.

2. Patients and methods

From 2009 to 2012, 112 live and deceased donor renal transplant recipients were prospectively followed-up over a 12 month period in a single-centre adult tertiary centre at Queen Elizabeth Hospital Birmingham, United Kingdom. To exclude pre-existing diabetes, patients underwent glucose testing (after a minimum of 8 h fasting) immediately prior to transplantation and excluded if ≥ 6.1 mmol/l or HbA1c ≥ 6.5% (48 mmol/mol). In addition, live donor recipients underwent oral glucose tolerance testing (OGTT) with a standard 75 g glucose load within a week prior to transplantation. Following transplantation, OGTTs were then performed at 7 days, and then 3 months and 12 months in all patients except those who developed clinically manifest hyperglycaemia requiring treatment. NODAT was diagnosed if a) fasting glucose ≥ 7 mmol/l or 2 h OGTT was ≥ 11.1 mmol/l from day 7 onwards and persisted at the 3 month timepoint, b) HbA1c ≥ 6.5% (48 mmol/mol) from 3 months onwards, or c) requirement for institution of therapy for NODAT in which case OGTT was not undertaken (fasting clinic glucose was ≥ 7 mmol/l in all such patients). Exclusion criteria of pre-transplant diabetes and the requirement for exclusion of non-white patients to avoid population stratification in a genetic investigation such as this resulted in 68 patients being prospectively followed.

All patients received an identical immunosuppression regimen consisting of anti-CD25 monoclonal antibody induction followed by maintenance tacrolimus (target per-dose trough levels 5–8 ng/ml by liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry), mycophenolate mofetil (2 g daily dose), and prednisolone (20 mg/day initially weaning to 5 mg/day by 3 months, and then continued).

Literature review to identify candidate gene variants was undertaken as described previously [1]. The eight β ‘glucotoxic’ SNPs that have been previously been investigated for NODAT in this cohort were excluded [4]. Genotyping were performed using Sequenom iPLEX technology.

The study received approval from the local research ethics committee (NRES West Midlands Black Country 08/H1204/103) prior to commencement and was conducted in accordance with the Declarations of Helsinki and Istanbul with patient written consent.

2.1. Statistical analysis

Data are shown as median (1st and 3rd quartiles) if not normally distributed or mean (± standard deviation) if normally distributed. Baseline demographics were assessed using Mann–Whitney U (non-parametric data) or Student t test if normally distributed for continuous data, and Fisher exact testing for categorical data as appropriate using SPSS software, version 20 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois) for analysis. Genotype distributions were assessed for concordance with Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium using a χ2 goodness-of-fit test with a type 1 error rate set at 5% analysed using PLINK [5]. Genotype to phenotype associations and event analyses were conducted using logistic regression with the development of NODAT at any time during the first 12 months post-transplantation as the end measure of interest (time-to-event analysis was not undertaken due to only 2 post-transplant timepoints). Univariate genotype:phenotype relationships and then the relationship in a multivariate model fully adjusted for age, sex, baseline body mass index (BMI), and change in BMI over 12 months from transplantation (no selection process) were calculated using PLINK [5].

3. Results

Demographics of the cohort are shown in Table 1. The cohort was aged 45 years (± 15), human leucocyte antigen (HLA) mismatched 2.41 (± 1.43), body mass index increase of 1.0 (± 2.2) with 68% undergoing live kidney transplantation. Eighteen patients (26.5%) were diagnosed with NODAT, of whom 11 patients (61.1%) were diagnosed on the basis of the result of OGTT testing alone. Patients developing NODAT were older and displayed greater changes in BMI over the first year of post-transplantation (p < 0.05 for both). There were no significant differences between patients developing and not developing NODAT for age, HLA mismatch, rejection episodes, overall steroid dose used per day, tacrolimus levels, or presence of adult polycystic kidney disease (p > 0.05 for all). No patients had a prevalent or incident hepatitis C virus infection.

Table 1.

Demographics of the study cohort.

| Characteristic | NODAT | Non-NODAT | All | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients (%) | 18 (26) | 50 (74) | 68 | |

| Age (years) | 54 (± 12) | 41 (± 15) | 45 (± 15) | 0.002 |

| Female (%) | 8 (44) | 20 (40) | 28 (41) | 0.785 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 27.5 (± 4.9) | 26.3 (± 4.8) | 26.6 (± 4.8) | 0.375 |

| Body mass index change (kg/m2) | − 0.5 (± 2.5) | 1.5 (± 1.9) | 1.0 (± 2.2) | 0.002 |

| Polycystic kidney disease (%) | 3 (17) | 7 (14) | 10 (15) | 0.717 |

| Transplant type, live (%) | 13 (72.2) | 33 (66) | 46 (67.6) | 0.775 |

| Human leucocyte antigen mismatch | 2.82 (± 1.59) | 2.45 (± 1.36) | 2.56 (± 1.43) | 0.371 |

| Total rejection episodes | 0.39 (± 0.61) | 0.25 (± 0.64) | 0.29 (± 0.63) | 0.179 |

| 1st month rejection episodes | 0.11 (± 0.32) | 0.13 (± 0.33) | 0.12 (± 0.33) | 1.000 |

| Prednisolone dose (mg/day) | 9.0 (6.3–9.7) | 6.3 (6.3–9.3) | 6.3 (6.3–9.7) | 0.120 |

| FK level (micrograms/l) | 8.8 (± 1.5) | 8.1 (± 1.3) | 8.3 (± 1.4) | 0.107 |

Bold values indicate significance at p value ≤ 0.05.

Out of the remaining 42 candidate SNPs that were identified by literature review [1], 37 were successfully genotyped (rs1800961 [HNFA], rs2069763 [IL-2], rs2265917 [SHPRH], rs6903252 [intergenic], and rs7903146 [TCF7L2] were unavailable as they were not amenable to the Sequenom iPLEX genotype bundle designs). The genotype success rate for the 37 SNPs was > 99%. Six SNPs (rs10117679 [GRIN3A], rs1016429 [GRIN3A], rs12255372 [TCF7L2], rs17657199 [NDST1], rs2070874 [IL-4], rs2240747 [ZNRF4]) demonstrated deviation from Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (p < 0.05).

In the adjusted logistic regression model, five SNPs were significantly associated with NODAT: rs16936667 [PRDM14: OR 10.57; 95% CI 1.8–63.0; p = 0.01], rs1801282 [PPARG: OR 8.5; 95% CI 1.4–52.7; p = 0.02], rs8192678 [PPARGC1A: OR 0.26; 95% CI 0.08–0.91; p = 0.03], rs2144908 [HNF4A: OR 7.0; 95% CI 1.1–45.0; p = 0.04], and rs2340721 [ATF6: OR 0.21; 95% CI 0.04–1.0; p = 0.05] (Table 2).

Table 2.

Univariate (p value) and multivariate analysis (p value adj) of the candidate single nucleotide polymorphisms for the development of new-onset diabetes after transplantation.

| SNP | Gene | Location | Minor allele | MAF | p value | p value adj | Odds ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs16936667 | PRDM14 | 8:70975726 | G | 0.16 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 10.6 (1.8–63.0) |

| rs1801282 | PPARG | 3:12393125 | G | 0.1 | 0.12 | 0.02 | 8.5 (1.4–52.7) |

| rs8192678 | PPARGC1A | 4:23815662 | A | 0.34 | 0.17 | 0.03 | 0.26 (0.08–0.91) |

| rs2144908 | HNF4A | 20:42985717 | A | 0.18 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 7.0 (1.1–45.0) |

| rs2340721 | ATF6 | 1:161849385 | A | 0.3 | 0.006 | 0.05 | 0.21 (0.04–1.0) |

| rs5219 | KCNJ11 | 11:17409572 | T | 0.34 | 0.08 | 0.12 | 2.7 (0.77–9.8) |

| rs10899444 | SHANK2 | 11:70606500 | G | 0.15 | 0.77 | 0.15 | 0.32 (0.07–1.5) |

| rs1025689 | IL-17RB | 3:53883722 | G | 0.44 | 0.14 | 0.15 | 0.45 (0.15–1.34) |

| rs1124053 | IL-17E | 14:22914819 | T | 0.23 | 0.05 | 0.16 | 2.7 (0.68–10.3) |

| rs2265477 | SHPRH | 6:146212338 | C | 0.46 | 0.54 | 0.17 | 0.45 (0.14–1.4) |

| rs6793265 | ITPR1 | 3:4735533 | T | 0.13 | 0.22 | 0.23 | 2.2 (0.60–8.4) |

| rs7145618 | PPP2R5C | 14:102329098 | C | 0.07 | 0.64 | 0.25 | 3.1 (0.44–21.5) |

| rs1783606 | SHANK2 | 11:70576651 | A | 0.14 | 0.99 | 0.26 | 0.42 (0.09–1.9) |

| rs2265919 | SHPRH | 6:146221753 | G | 0.44 | 0.74 | 0.29 | 0.54 (0.18–1.7) |

| rs3212574 | ITGA2 | 5:52366779 | A | 0.23 | 0.94 | 0.30 | 2.1 (0.50–9.2) |

| rs2107538 | CCL5 | 17:34207780 | T | 0.18 | 0.07 | 0.34 | 2.1 (0.46–9.5) |

| rs2240747 | ZNRF4 | 19:5456930 | C | 0.21 | 0.86 | 0.37 | 2.0 (0.45–8.7) |

| rs17657199 | NDST1 | 5:149950246 | T | 0.03 | 0.37 | 0.41 | 2.5 (0.28–23.3) |

| rs3817655 | CCL5 | 17:34199641 | A | 0.18 | 0.12 | 0.48 | 1.8 (0.37–8.5) |

| rs4819554 | IL-17RA | 22:17565035 | G | 0.12 | 0.62 | 0.49 | 1.7 (0.38–7.9) |

| rs341497 | DIAPH3 | 13:60429001 | C | 0.06 | 0.45 | 0.49 | 2.0 (0.28–14.1) |

| rs1800795 | IL-6 | 7:22766645 | C | 0.43 | 0.90 | 0.53 | 0.72 (0.26–2.0) |

| rs2280789 | CCL5 | 17:34207003 | C | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.59 | 1.7 (0.26–10.7) |

| rs1799854 | ABCC8 | 11:17448704 | T | 0.4 | 0.51 | 0.60 | 0.75 (0.25–2.2) |

| rs1016429 | GRIN3A | 9:104402364 | C | 0.1 | 0.41 | 0.64 | 1.6 (0.24–10.0) |

| rs2069762 | IL-2 | 4:123377980 | G | 0.25 | 0.21 | 0.66 | 1.3 (0.39–4.4) |

| rs1494558 | IL-7R | 5:35861068 | A | 0.35 | 0.79 | 0.70 | 1.2 (0.46–3.2) |

| rs2172749 | IL-7R | 5:35855264 | C | 0.35 | 0.79 | 0.70 | 1.2 (0.46–3.2) |

| rs1043261 | IL-17RB | 3:53899276 | T | 0.11 | 0.23 | 0.71 | 0.73 (0.14–3.8) |

| rs1044498 | ENPP1 | 6:132172368 | C | 0.14 | 0.21 | 0.74 | 0.80 (0.21–3.1) |

| rs2070874 | IL-4 | 5:132009710 | T | 0.17 | 0.60 | 0.78 | 0.82 (0.21–3.3) |

| rs10117679 | GRIN3A | 9:104378479 | T | 0.06 | 0.44 | 0.81 | 1.4 (0.1–18.3) |

| rs1169288 | HNF1A | 12:121416650 | G | 0.36 | 0.96 | 0.82 | 1.1 (0.35–3.8) |

| rs13266634 | SLC30A8 | 8:118184783 | T | 0.38 | 0.53 | 0.84 | 0.89 (0.30–2.7) |

| rs12255372 | TCF7L2 | 10:114808902 | T | 0.28 | 0.94 | 0.91 | 1.1 (0.41–2.7) |

| rs1871184 | ITGA1 | 5:52234323 | T | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.92 | 1.1 (0.16–7.4) |

| rs17722392 | KIDINS220 | 2:8940154 | C | 0.05 | 0.44 | 0.93 | 1.1 (0.09–13.8) |

Key: SNP: single nucleotide polymorphism, MAF: minor allele frequency, p value adj: p value adjusted for age, sex, body mass index at baseline and change after 12 months, CI: confidence interval.

Bold values indicate significance at p value ≤ 0.05.

4. Discussion

This study identifies SNP variants in common genes which are associated with the development of NODAT following kidney transplantation, thereby hypothesis generating to our understanding of mechanisms involved (discussed below) and the potential for risk-stratifying patients pre-transplantation. Some of the features of the study are relevant and worth noting in the context of its findings. Firstly, all patients underwent screening for diabetes prior to transplantation, and so the episodes of diabetes following transplantation were truly ‘new onset’ rather than pre-transplant diabetes which was picked up post-transplantation. Indeed, for the live donor recipients in the study, OGTTs were also undertaken to exclude pre-transplant diabetes. For the diagnosis of diabetes following transplantation, OGTTs were undertaken at serial timepoints in a carefully phenotyped prospective cohort, and so we believe that this study is particularly sensitive to the development of NODAT. Interestingly, the majority of patients were only diagnosed as a result of the OGTTs conducted specifically and additionally as part of this research study and would have been missed (or the diagnosis delayed) in routine clinical practice. Secondly, although the inclusion of only white patients (self-reported) does limit generalisation to other ethnicities, it does nevertheless make the study's findings more robust by limiting (albeit not fully excluding) the confounding effect of population stratification. Finally, the identified SNPs have been previously recognised as risk factors for diabetes and also for NODAT, and the current study therefore replicates these findings. As such, the p values have not been corrected for multiple comparisons. At 5% risk of false positives in the 37 SNPs would result in approximately 2 false positives assuming that the SNPs were independent of each other, yet, in view of the potential inter-relationship (discussed below) of the SNPs, the actual number of false positives is likely to be lower.

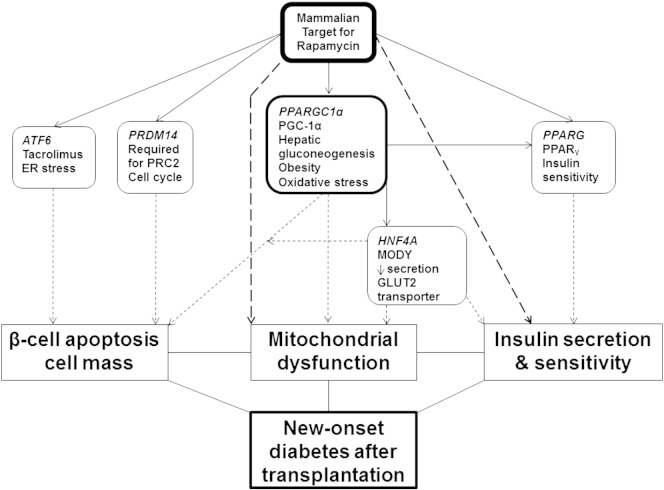

The potential detrimental effects of hyperglycaemia on pancreatic human β cells resulting in reduced proliferation and increased apoptosis after 2 days and loss of secretory function after 4 days have been shown in vitro which is reflected in the time to NODAT onset in this study [6], [7]. The five reported SNPs associated with NODAT in this study mirror the above mechanisms, and fall into three main interrelated categories, namely β cell apoptosis with reduction in cell mass, insulin sensitivity/release, and mitochondrial dysfunction (Fig. 1). The mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) is a member of the phospho-inositide 3-kinase (PI3K)-related kinase family and has a central role in the regulation of these SNPs.

Fig. 1.

Schematic of how the significant candidate genes may lead to new-onset diabetes after transplantation development, with mTOR being the central regulator to this.

It regulates peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma co-activator 1 alpha (PGC1α – PPARGC1α rs8192678) and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARy – PPARG rs1801282) signalling to promote cell growth, proliferation, metabolism, and survival; both these SNPs have been associated with type II diabetes previously [8], [9]. mTOR enhances the activity of these transcription factors PPARy and PGC1α by the regulation of lipid synthesis, thus acts as a key sensor for mitochondrial and B cell nutrient status via leucine and its regulation of AMP-activated protein kinase inhibiting secretion of insulin, controlling mitochondrial oxidative metabolism, and biogenesis through transcription PGC1α physical interaction with yin-yang 1 [10], [11]. mTOR regulates the transcription regulator, PR domain zinc protein 14 (PRDM14 rs16936667), which interacts directly with the chromatin regulator polycomb repressive complex 2 to exert its effects via trimethylation of histone H3 lysine27 and enhancer of zeste homolog 2 to regulate β cell proliferation, cell mass, and apoptosis [12], [13], [14]. This SNP was associated with NODAT in the recent GWAS [1].

Activated transcription factor 6 (ATF6 rs2340721) is present in pancreatic β cells, adipocytes, and hepatocytes. It becomes activated during periods of tacrolimus-induced endoplasmic reticulum stress in transplantation, to improve cell survival via mTOR in combating the unfolded protein response that leads to apoptosis, lipogenesis, and gluconeogenesis [15], [16]. Although not previously associated with NODAT, this SNP has been associated with an increased BMI in a renal transplant cohort [15], pre-diabetes in a Chinese cohort [17], and has been found in tight linkage disequilibrium (in Caucasians) with rs2070150 which is associated with type II diabetes in Pima Indians [18]. Mutations in the gene hepatocyte nuclear factor 4 (HNF4 rs2144908) have been associated with NODAT [19] and reduced insulin secretion to glucose stimulation due to progressive β-cell dysfunction, with defects in the GLUT2 transporter and mitochondrial dysfunction in the pathogenesis of maturity onset of diabetes in the young [20], [21], [22]. mTOR has an indirect effect on HNF4α by its regulation of PPARGC1α which co-activates with HNF4α thus regulating downstream gluconeogenic targets [23], [24].

In vivo studies have shown chronic inhibition of mTOR by rapamycin leads to insulin resistance and lipid dysregulation associated with defective insulin, insulin growth factor signalling, and β-cell toxicity [10], [25], [26]. However, there remains controversy over the use of sirolimus and the development of NODAT with some studies suggesting that its use is an independent risk factor for NODAT [27] while in others, sirolimus has been used to improve the metabolic parameters in a small number of NODAT patients as a substitute for calcineurin inhibitors [28]. Recent studies have also highlighted the dyslipidaemia, need for more anti-lipid medication [29], and the requirement for higher steroid dose in a sub-analysis of the SYMPHONY trial with the use of sirolimus [30] and thus questions if conversion to sirolimus will improve the cardiovascular survival outcomes in patients with or at risk of NODAT.

It should be stated that for the number of SNPs tested in this study compared to the 18 cases of NODAT and 50 non-NODAT control patients, the power is 60% to identify OR of 2, with 20% minor allele frequency, thus the 5 identified SNPs in this study requires further validation in another cohort as the optimal way of confirming these findings [31].

4.1. Conclusion

In summary, this study represents a replication study of candidate SNPs in regard to the risk of developing NODAT following kidney transplantation. It is hypothesis generating into the prevailing mechanisms of this important complication of transplantation and may even serve to stratify the risk for individual patients.

Transparency document

Transparency document.

Acknowledgements

JAM is in receipt of a Kidney Research UK Clinical Research Training Fellowship. There are no author conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

The Transparency document associated with this article can be found in online version.

References

- 1.McCaughan J.A., McKnight A.J., Maxwell A.P. Genetics of new-onset diabetes after transplantation. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2014;25:1037–1049. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013040383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sharif A., Moore R.H., Baboolal K. The use of oral glucose tolerance tests to risk stratify for new-onset diabetes after transplantation: an underdiagnosed phenomenon. Transplantation. 2006;82:1667–1672. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000250924.99855.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bergrem H.A., Valderhaug T.G., Hartmann A. Undiagnosed diabetes in kidney transplant candidates: a case-finding strategy. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2010;5:616–622. doi: 10.2215/CJN.07501009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chand S., Shabir S., Chan W. beta cell glucotoxic-associated single nucleotide polymorphisms in impaired glucose tolerance and new-onset diabetes after transplantation. Transplantation. 2014;98:e19–e20. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000000268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Purcell S., Neale B., Todd-Brown K. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007;81:559–575. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Donath M.Y., Ehses J.A., Maedler K. Mechanisms of beta-cell death in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2005;54(Suppl. 2):S108–S113. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.suppl_2.s108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Favaro E., Miceli I., Bussolati B. Hyperglycemia induces apoptosis of human pancreatic islet endothelial cells: effects of pravastatin on the Akt survival pathway. Am. J. Pathol. 2008;173:442–450. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.080238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hara K., Tobe K., Okada T. A genetic variation in the PGC-1 gene could confer insulin resistance and susceptibility to type II diabetes. Diabetologia. 2002;45:740–743. doi: 10.1007/s00125-002-0803-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moon M.K., Cho Y.M., Jung H.S. Genetic polymorphisms in peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma are associated with type 2 diabetes mellitus and obesity in the Korean population. Diabet. Med. 2005;22:1161–1166. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2005.01599.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blattler S.M., Cunningham J.T., Verdeguer F. Yin yang 1 deficiency in skeletal muscle protects against rapamycin-induced diabetic-like symptoms through activation of insulin/IGF signaling. Cell Metab. 2012;15:505–517. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Laplante M., Sabatini D.M. mTOR signaling at a glance. J. Cell Sci. 2009;122:3589–3594. doi: 10.1242/jcs.051011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chan Y.S., Goke J., Lu X. A PRC2-dependent repressive role of PRDM14 in human embryonic stem cells and induced pluripotent stem cell reprogramming. Stem Cells. 2013;31:682–692. doi: 10.1002/stem.1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen H., Gu X., Su I.H. Polycomb protein Ezh2 regulates pancreatic beta-cell Ink4a/Arf expression and regeneration in diabetes mellitus. Genes Dev. 2009;23:975–985. doi: 10.1101/gad.1742509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhou J.X., Dhawan S., Fu H. Combined modulation of polycomb and trithorax genes rejuvenates beta cell replication. J. Clin. Invest. 2013;123:4849–4858. doi: 10.1172/JCI69468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fougeray S., Loriot M.A., Nicaud V., Legendre C., Thervet E., Pallet N. Increased body mass index after kidney transplantation in activating transcription factor 6 single polymorphism gene carriers. Transplant. Proc. 2011;43:3418–3422. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2011.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Odisho T., Zhang L., Volchuk A. ATF6beta regulates the Wfs1 gene and has a cell survival role in the ER stress response in pancreatic beta-cells. Exp. Cell Res. 2015;330:111–122. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2014.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gu N., Ma X., Zhang J. Obesity has an interactive effect with genetic variation in the activating transcription factor 6 gene on the risk of pre-diabetes in individuals of Chinese Han descent. PLoS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0109805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thameem F., Farook V.S., Bogardus C., Prochazka M. Association of amino acid variants in the activating transcription factor 6 gene (ATF6) on 1q21-q23 with type 2 diabetes in Pima Indians. Diabetes. 2006;55:839–842. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.55.03.06.db05-1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang J., Hutchinson I.I., Shah T., Min D.I. Genetic and clinical risk factors of new-onset diabetes after transplantation in Hispanic kidney transplant recipients. Transplantation. 2011;91:1114–1119. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31821620f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Byrne M.M., Sturis J., Menzel S. Altered insulin secretory responses to glucose in diabetic and nondiabetic subjects with mutations in the diabetes susceptibility gene MODY3 on chromosome 12. Diabetes. 1996;45:1503–1510. doi: 10.2337/diab.45.11.1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mohlke K.L., Boehnke M. The role of HNF4A variants in the risk of type 2 diabetes. Curr. Diab. Rep. 2005;5:149–156. doi: 10.1007/s11892-005-0043-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang H., Maechler P., Antinozzi P.A., Hagenfeldt K.A., Wollheim C.B. Hepatocyte nuclear factor 4alpha regulates the expression of pancreatic beta-cell genes implicated in glucose metabolism and nutrient-induced insulin secretion. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:35953–35959. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006612200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Charos A.E., Reed B.D., Raha D., Szekely A.M., Weissman S.M., Snyder M. A highly integrated and complex PPARGC1A transcription factor binding network in HepG2 cells. Genome Res. 2012;22:1668–1679. doi: 10.1101/gr.127761.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schmidt S.F., Mandrup S. Gene program-specific regulation of PGC-1{alpha} activity. Genes Dev. 2011;25:1453–1458. doi: 10.1101/gad.2076411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lopes P.C., Fuhrmann A., Carvalho F. Cyclosporine A enhances gluconeogenesis while sirolimus impairs insulin signaling in peripheral tissues after 3 weeks of treatment. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2014;91:61–73. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2014.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barlow A.D., Nicholson M.L., Herbert T.P. Evidence for rapamycin toxicity in pancreatic beta-cells and a review of the underlying molecular mechanisms. Diabetes. 2013;62:2674–2682. doi: 10.2337/db13-0106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gyurus E., Kaposztas Z., Kahan B.D. Sirolimus therapy predisposes to new-onset diabetes mellitus after renal transplantation: a long-term analysis of various treatment regimens. Transplant. Proc. 2011;43:1583–1592. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2011.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Veroux M., Tallarita T., Corona D. Conversion to sirolimus therapy in kidney transplant recipients with new onset diabetes mellitus after transplantation. Clin. Dev. Immunol. 2013;2013:496974. doi: 10.1155/2013/496974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guerra G., Ciancio G., Gaynor J.J. Randomized trial of immunosuppressive regimens in renal transplantation. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2011;22:1758–1768. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2011010006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Claes K., Meier-Kriesche H.U., Schold J.D., Vanrenterghem Y., Halloran P.F., Ekberg H. Effect of different immunosuppressive regimens on the evolution of distinct metabolic parameters: evidence from the Symphony Study. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2012;27:850–857. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfr238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lieberman M.D., Cunningham W.A. Type I and type II error concerns in fMRI research: re-balancing the scale. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2009;4:423–428. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsp052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Transparency document.