Abstract

Background

IgA nephropathy (IgAN) and Henoch-Schönlein purpura nephritis (HSPN) are glomerular diseases that share a common and central pathogenic mechanism. The formation of immune complexes containing IgA1, myeloid IgA Fc alpha receptor (FcαRI/CD89) and transglutaminase-2 (TG2) is observed in both conditions. Therefore, urinary CD89 and TG2 could be potential biomarkers to identify active IgAN/HSPN.

Methods

In this multicenter study, 160 patients with IgAN or HSPN were enrolled. Urinary concentrations of CD89 and TG2, as well as some other biochemical parameters, were measured.

Results

Urinary CD89 and TG2 were lower in patients with active IgAN/HSPN compared to IgAN/HSPN patients in complete remission (P < 0.001). The CD89xTG2 formula had a high ability to discriminate active from inactive IgAN/HSPN in both situations: CD89xTG2/proteinuria ratio (AUC: 0.84, P < 0.001, sensitivity: 76%, specificity: 74%) and CD89xTG2/urinary creatinine ratio (AUC: 0.82, P < 0.001, sensitivity: 75%, specificity: 74%). Significant correlations between urinary CD89 and TG2 (r = 0.711, P < 0.001), proteinuria and urinary CD89 (r = − 0.585, P < 0.001), and proteinuria and urinary TG2 (r = − 0.620, P < 0.001) were observed.

Conclusions

Determination of CD89 and TG2 in urine samples can be useful to identify patients with active IgAN/HSPN.

Keywords: Henoch-Schönlein purpura nephritis, IgA nephropathy, Myeloid IgA Fc alpha receptor, Transglutaminase-2

Highlights

-

•

IgAN and HSPN are glomerular diseases with a common central pathogenic mechanism.

-

•

Anatomopathological analysis of renal biopsies is required for diagnosis.

-

•

Urinary CD89 and urinary TG2 are decreased in patients with active IgAN/HSPN.

-

•

The CD89xTG2 product has a high ability to discriminate active IgAN/HSPN.

1. Introduction

IgA nephropathy (IgAN) is the most prevalent form of chronic glomerulonephritis in the world with an estimated frequency of at least 2.5 cases per year per 100,000 adults [1]. The exact cause of primary IgAN is still unknown, but its onset is commonly associated with upper respiratory tract infections and episodes of macroscopic hematuria [2], [3]. Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP) is the most frequent form of vasculitis in children and about 40% of children with HSP develop nephritis (HSPN) [4], [5]. Although in the majority of cases a benign and self-limiting course is observed, some patients with HSPN can potentially progress to end-stage renal disease (ESRD) [4]. Actually, up to 30% of IgAN patients progress to ESRD by 20 years, and many of these patients need for renal replacement treatment [6], [7].

The clinical, genetic and immunologic characteristics of IgAN and HSPN are closely linked, and HSPN can be considered as the systemic form of IgAN [4], [8], [9]. IgAN and HSPN share a common and central pathogenic mechanism associated with an aberrant O-linked glycosylation in the hinge region of IgA1 molecules [2], [4], [5], [10], [11]. The recognition of this IgA1 hinge region neoepitope by naturally occurring IgA1 or IgG antibodies leads to generation of immune complexes in the circulation and to deposition of these nephrotoxic immune complexes in the glomerulus [12]. The formation of undergalactosylated, large-molecular-mass IgA1-IgG containing immune complexes forms a part of the not yet fully elucidated pathogenesis of IgAN [13]. However, some key molecules have been identified, which contribute to the formation of the immune complexes: myeloid IgA Fc alpha receptor (FcαRI/CD89), transglutaminase-2 (TG2) and transferrin receptor (TfR/CD71) [1], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17].

FcαRI/CD89 is a type I transmembrane glycoprotein expressed mainly on the surface of myeloid cells that binds both IgA1 and IgA2 with a similar affinity [18], [19]. TG2 (EC 2.3.2.13), the most ubiquitously expressed member of the transglutaminase family, has been proposed to be responsible for a pathogenic amplification loop, facilitating IgA1-CD89 deposition and mesangial cell activation in IgAN [16]. Additionally, it has been suggested that the aberrant glycosylated IgA1 stimulates the expression of mesangial CD71 and mediates mesangial deposition of nephritogenic IgA1-immune complexes [20], [21], [22]. A new and sensitive latex-enhanced nephelometric assay for measurement of urinary CD71 has recently been developed by our team. In a previous study, we have demonstrated that urinary CD71 concentrations were higher in patients with active IgAN/HSPN in comparison with patients with other types of glomerulopathy [13].

The measurement of novel urinary biomarkers might be a tool to provide meaningful information for the diagnosis of IgAN/HSPN. An early diagnosis is crucial to prevent the progression of these diseases to ESRD [13], [23]. In addition, no attempts have been made to determine the urinary concentration of CD89 and TG2 in IgAN/HSPN patients. Therefore, in the present study we have investigated the potential use of urinary CD89 and TG2 as new biomarkers in IgAN/HSPN.

2. Subjects and methods

2.1. Patients

A total of 160 Caucasian patients with a biopsy proven IgAN or HSPN (95 males, 65 females, mean age ± SD: 36.8 ± 19.8 years) were consecutively recruited between November 2012 and February 2015 in this multicenter study [Department of Nephrology at the Ghent University Hospital (Gent, Belgium), Department of Nephrology and Transplantation Medicine at the Wroclaw Medical University (Wroclaw, Poland), Department of Transplantation Medicine and Nephrology, Medical University of Warsaw (Warsaw, Poland) and Department of Emergency and Organ Transplantation, Section of Nephrology at University of Bari “Aldo Moro” (Bari, Italy)]. Renal biopsies of IgAN were scored according to the Oxford MEST scoring system by pathologists experienced in the classification. The MEST score was defined as follows: M0/M1 as a mesangial score ≤ or > 0.5, or ≤ or > 50% of glomeruli with ≥ 4 mesangial cells per mesangial area, E0/E1 as the presence or absence of endocapillary hypercellularity, S0/S1 as the presence or absence of segmental sclerosis or tuft adhesions, and T0/T1/T2 as the degree of tubular atrophy or interstitial fibrosis (< 25%, 25–50%, > 50%, respectively) [24]. The biopsy findings of HSPN were graded according to the classification developed by the International Study of Kidney Disease in Children (ISKDC) [25]: (I) minimal glomerular abnormalities, (II) mesangial proliferation (MP), (III) MP with < 50% crescents, (IV), MP with 50–75% crescents, (V) MP with > 75% crescents, and (VI) membranoproliferative-like lesions.

Reviewing literature, the proposed remission criteria of IgAN/HSPN vary depending on the clinical studies. Therefore, a uniform assessment of treatment outcomes and a standardization of explanations of the condition is difficult. We opted to classify the disease status of IgAN/HSPN patients based on the proteinuria cutoff criteria [26]. A complete remission was defined as a proteinuria level of < 0.03 g/mmol creatinine, a partial remission was defined as a proteinuria level of 0.03 to 0.11 g/mmol creatinine and an active disease status corresponded with a proteinuria level of > 0.11 g/mmol creatinine. This study was approved by the local Ethics Review Board according to the Declaration of Helsinki and all patients signed an informed consent.

2.2. Routine biochemistry analyses

Urine samples were collected at time of diagnosis or during the follow up period and sent to the laboratory of the Ghent University hospital, where they were stored at − 80 °C, awaiting further analyses. Stability tests showed no significant influence of the storage procedure on the measured parameters. Spot urine samples were centrifuged at 3000 × g for 10 min before testing. The total urinary protein concentration was assayed using a pyrogallol red-based colorimetric assay [27] on a Cobas 8000® modular analyzer (Roche Diagnostics®, Mannheim, Germany), and serum creatinine levels were measured by a rate-blanked compensated Jaffe method on the same analyzer. The urinary IgA concentration was measured on a BN II nephelometer (Siemens®, Marburg, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The intra-assay coefficient of variation (CV) and inter-assay CV were < 5%. The estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of each participant was measured with the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation, which includes age, sex, race and serum creatinine levels [28].

2.3. Urinary soluble transferrin receptor (sTfR, CD71) assay

The spot urine samples were concentrated tenfold by ultrafiltration on a polyethersulfone membrane with a 7.5 kDa cutoff (Vivapore®, Sartorius Stedim Lab, Gloucestershire, UK). The urinary CD71 concentration was assayed in the concentrate by use of a newly developed latex-enhanced immunonephelometric assay on a BN II nephelometer (Siemens®, Marburg, Germany), as previously described in detail and validated by our research team [13]. The intra-assay coefficient of variation (CV) was 3.0% and inter-assay CV was 3.1%.

2.4. Urinary Fc fragment of IgA receptor (FcaR, CD89) assay

The urinary CD89 concentration was assayed in spot urine samples by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) with a human antibody specific to CD89 (Cloud-Clone Corp®, Houston, TX, USA) according to the manufacturers' instructions. Briefly, 100 μL of standards or urine was added to the wells and incubated for 120 min at 37 °C. The liquid of each well was removed and 100 μL of biotin-conjugated antibody specific for the human Fc fragment of the IgA receptor (primary antibody) was added. After 1 h of incubation, the liquid was removed and each well was washed three times with 350 μL of wash solution. 100 μL of avidin conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (HRP) was added to each microplate well and incubated for 30 min at 37 °C. Free components were washed five times with 350 μL of wash solution and 90 μL of substrate solution was added to each well. After 15 min of incubation, 50 μL of stop solution was added to each well. The optical density (O.D.) was immediately measured at 450 nm by the use of the automated Zenit UP (A. Menarini Diagnostics®, Florence, Italy) system. The urinary concentrations of CD89 were calculated after comparing the O.D. of the samples with the standard curve in the Microplate Manager® version 4.0 software (Bio-Rad Laboratories®, Hercules, CA, USA). The detection range of this assay was 0.781–50 ng/mL and its sensitivity was 0.35 ng/mL. Intra-assay CV was < 10% and inter-assay CV was < 12%.

2.5. Urinary transglutaminase 2 (TG2) assay

The urinary TG2 concentration was assayed in spot urine samples by an ELISA with a human antibody specific to TG2 (Elabscience®, Wuhan, China) according to the manufacturers' instructions. Briefly, 100 μL of standards or urine was added to the wells and incubated for 90 min at 37 °C. The liquid of each well was removed and 100 μL of biotinylated detection antibody specific for human TG2 (primary antibody) was added. After 1 h of incubation, the liquid was removed and each well was washed three times with 350 μL of wash solution. 100 μL of HRP conjugate was added to each well and incubated for 30 min at 37 °C. Free components were washed five times with 350 μL of wash solution and 90 μL of substrate solution was added to each well. After 15 min of incubation, 50 μL of stop solution was added to each well. The O.D. was immediately measured at 450 nm by use of the automated Zenit UP (A. Menarini Diagnostics®, Florence, Italy) system. The urinary concentrations of TG2 were calculated after comparing the O.D. of the samples with the standard curve in the Microplate Manager® version 4.0 software (Bio-Rad Laboratories®, Hercules, CA, USA). The detection range of this assay was 0.156–10 ng/mL and its sensitivity was 0.094 ng/mL. The intra-assay and inter-assay CV were < 10%.

2.6. Statistical analysis

The distribution of variables was tested using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Continuous variables were reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or 95% confidence interval (CI) or median with interquartile ranges (IQR). Categorical data were summarized as percentages and a comparison between groups was performed with the χ2 test. Statistical differences between groups were evaluated by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by the Tukey's multiple comparison test or the Kruskal-Wallis test followed by the Dunn's multiple comparison test. Correlation analysis was performed with the nonparametric Spearman rank test. Receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curve was performed to quantify the overall ability of biomarkers to discriminate active from inactive IgAN/HSPN. Contingency tables were evaluated by Fisher's exact test. All hypothesis tests were performed as 2-sided at the 5% significance level. A P value of < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 4.00 for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA) and Statistica 6.0 (StatSoft Inc., Tulsa, OK).

3. Results

The mean follow time between diagnosis of IgAN of HSPN and the analysis of the investigated biomarkers in the present study was 52 months [95% CI: 38–66 months]. 46% of the patients were included in the study at the time of diagnosis, whereas 54% of the samples were collected during the follow up period. At the time of inclusion, 38% of the patients were treated with angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor blockers, 16% with corticosteroids, 10% with another immunosuppresive drug (mycophenolate mofetil, cyclosporin or azathioprine) and 4% with fish oil/omega-3 fatty acids. An overview of the baseline characteristics and biochemical parameters of the study participants is summarized in Table 1. The levels of proteinuria and the urinary IgA concentrations were higher in patients with active IgAN/HSPN compared with those in complete or partial remission. A significant decrease in kidney function was observed in patients with active IgAN/HSPN compared with the group in complete or partial remission.

Table 1.

Overview of baseline characteristics and parameters of the study patients.

| IgAN/HSPN in complete remission (defined as proteinuria < 0.03 g/mmol creatinine) |

IgAN/HSPN in partial remission (defined as proteinuria 0.03 to 0.11 g/mmol creatinine) |

Active IgAN/HSPN (defined as proteinuria > 0.11 g/mmol creatinine) |

P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 67 | 51 | 42 | - |

| Age (years) | 37.9 ± 22.9 | 32.6 ± 17.3 | 40.3 ± 16.5 | 0.164 |

| Male (%) | 59.7 | 52.9 | 66.7 | 0.406 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73m2) | 84.2 ± 33.4 | 76.8 ± 30.1 | 59.0 ± 33.9 | 0.002 |

| Urinary IgA (mg/mmol creatinine) | 0.14 (0.08–0.25) | 0.44 (0.28–0.72) | 2.56 (1.37–3.79) | < 0.001 |

Results are expressed as %, mean ± SD or median (IQR). Abbreviations: IgAN, IgA nephropathy; HSPN, Henoch-Schönlein purpura nephritis; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate.

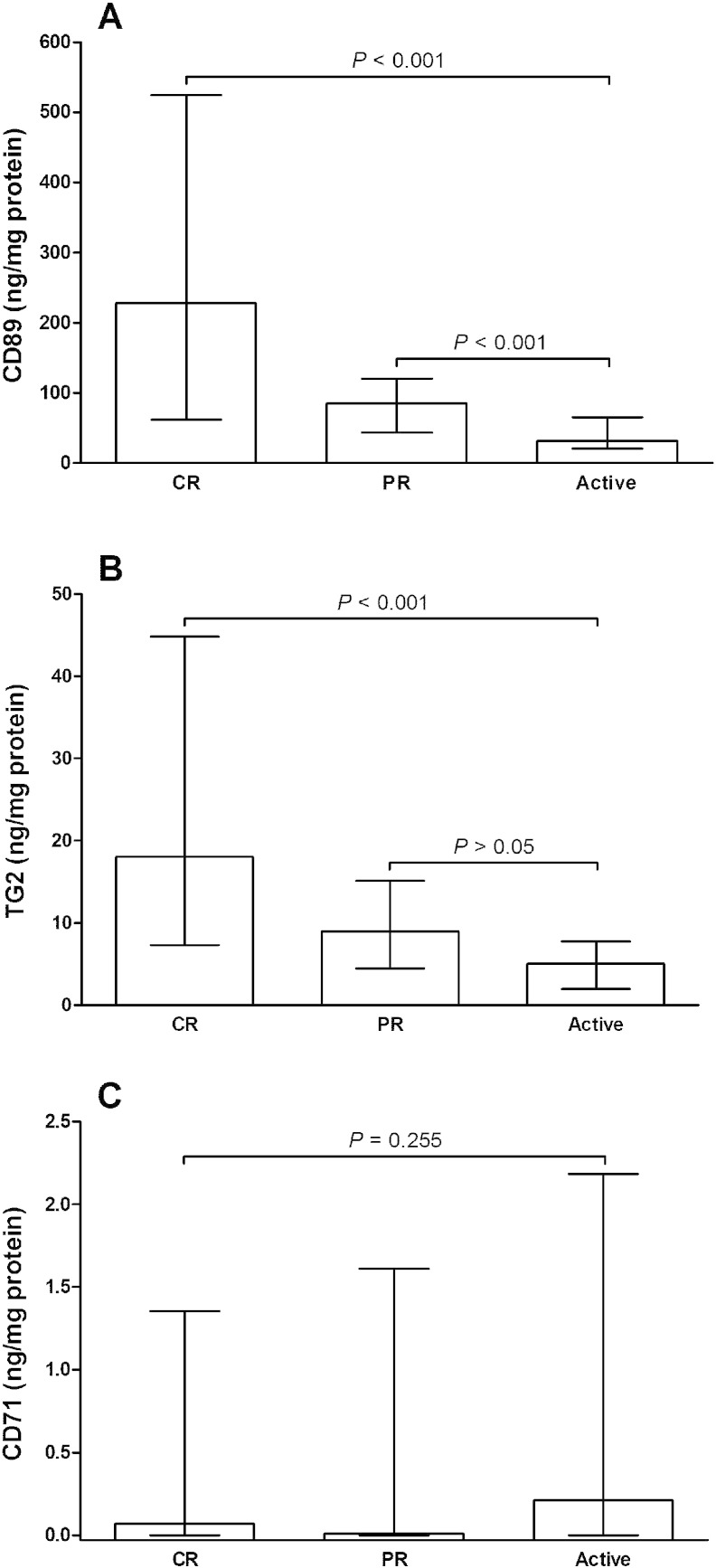

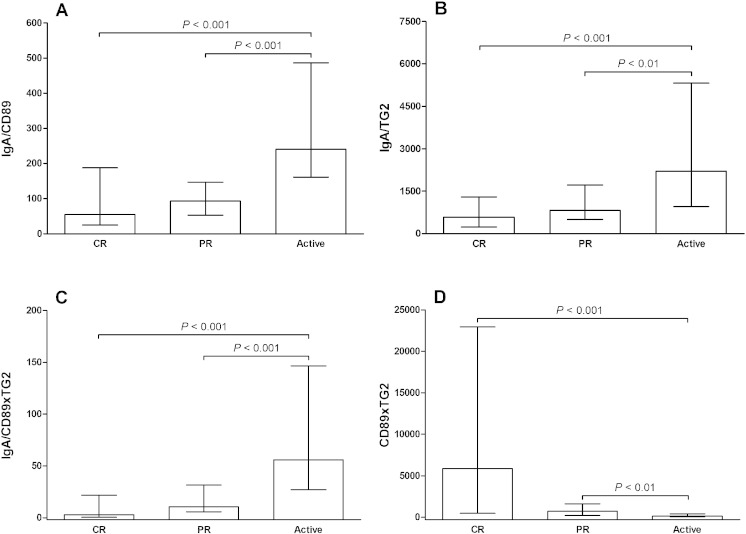

The urinary CD89 concentration was statistically lower in patients with active IgAN/HSPN compared to IgAN/HSPN patients in complete or partial remission (P < 0.001) (Fig. 1A). In addition, the urinary TG2 concentration was lower in patients with active IgAN/HSPN than IgAN/HSPN patients in complete remission (P < 0.001) (Fig. 1B). No significant difference in the urinary CD71 concentration was found between the different stages of IgAN/HSPN (Fig. 1C). Patients with active IgAN/HSPN had significantly higher IgA/CD89, IgA/TG2 and IgA/CD89xTG2 ratios than IgAN/HSPN patients in complete or partial remission (Figs. 2A, B and C). In contrast, CD89xTG2 values were lower in patients with active IgAN/HSPN compared with IgAN/HSPN patients in complete or partial remission (P < 0.001 and P < 0.01, respectively) (Fig. 2D).

Fig. 1.

Comparison of (A) urinary CD89 (ng/mg protein), (B) urinary transglutaminase-2 (TG2) (ng/mg protein) and (C) urinary CD71 (ng/mg protein) in patients with IgA nephropathy or Henoch-Schönlein purpura nephritis (IgAN/HSPN) in complete remission (CR), partial remission (PR) or active disease. Results are expressed as medians and interquartile ranges.

Fig. 2.

Comparison of (A) urinary IgA/CD89 ratio, (B) urinary IgA/TG2 ratio, (C) urinary IgA/CD89xTG2 ratio and (D) urinary CD89xTG2 in patients with IgA nephropathy or Henoch-Schönlein purpura nephritis (IgAN/HSPN) in complete remission (CR), partial remission (PR) or active disease. Results are expressed as medians and interquartile ranges.

ROC curve analysis was employed to quantify the ability of the urinary biomarkers to identify active IgAN/HSPN. Overall AUCs of CD89, TG2, CD89xTG2, IgA/CD89, IgA/TG2 and IgA/CD89xTG2 were 0.82, 0.81, 0.84, 0.80, 0.79 and 0.86, respectively, and all of these AUCs were statically significant (P < 0.001) (Table 2). Urinary CD71 (ng/mg protein) was not able to discriminate active from inactive IgAN/HSPN (AUC: 0.57, P = 0.240). However, the urinary CD71/creatinine ratio (ng/mg creatinine) was able to identify active IgAN/HSPN (AUC: 0.69, P < 0.01). Additionally, we investigated if the corrections by urinary creatinine affected the diagnostic ability of the other biomarkers. The overall AUCs of the CD89/urinary creatinine ratio, the TG2/urinary creatinine ratio, the CD89xTG2/urinary creatinine ratio, the IgA/CD89/urinary creatinine ratio, the IgA/TG2/urinary creatinine ratio and the IgA/CD89xTG2/urinary creatinine ratio were 0.78 (P < 0.001), 0.78 (P < 0.001), 0.82 (P < 0.001), 0.80 (P < 0.001), 0.79 (P < 0.001) and 0.54 (P = 0.549), respectively. The IgA/CD89xTG2 ratio had a slightly higher ability to discriminate active from inactive IgAN/HSPN (sensitivity: 84%, specificity: 76%) in comparison with the other studied biomarkers. However, after the correction by urinary creatinine, the IgA/CD89xTG2 ratio was not able to discriminate active from inactive IgAN/HSPN (AUC: 0.54, P = 0.549). In addition, the CD89xTG2 demonstrated a high ability to distinguish active IgAN/HSPN in both situations: CD89xTG2/proteinuria ratio (AUC: 0.84, P < 0.001, sensitivity: 76%, specificity: 74%) and CD89xTG2/urinary creatinine ratio (AUC: 0.82, P < 0.001, sensitivity: 75%, specificity: 74%).

Table 2.

Characteristics of urinary biomarkers for assessment of active IgA nephropathy/Henoch-Schönlein purpura nephritis (IgAN/HSPN).

| AUC | 95% CI | P-value | Cut-off | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD89 | 0.82 | 0.74–0.90 | < 0.001 | 50 | 81 | 72 |

| TG2 | 0.81 | 0.73–0.89 | < 0.001 | 7.2 | 78 | 72 |

| CD89xTG2 | 0.84 | 0.76–0.92 | < 0.001 | 380 | 76 | 74 |

| IgA/CD89 | 0.80 | 0.72–0.89 | < 0.001 | 163 | 71 | 76 |

| IgA/TG2 | 0.79 | 0.69–0.88 | < 0.001 | 1257 | 76 | 74 |

| IgA/CD89xTG2 | 0.86 | 0.78–0.93 | < 0.001 | 30 | 84 | 76 |

IgA, immunoglobulin A; CD89, myeloid IgA Fc alpha receptor; TG2, transglutaminase-2.

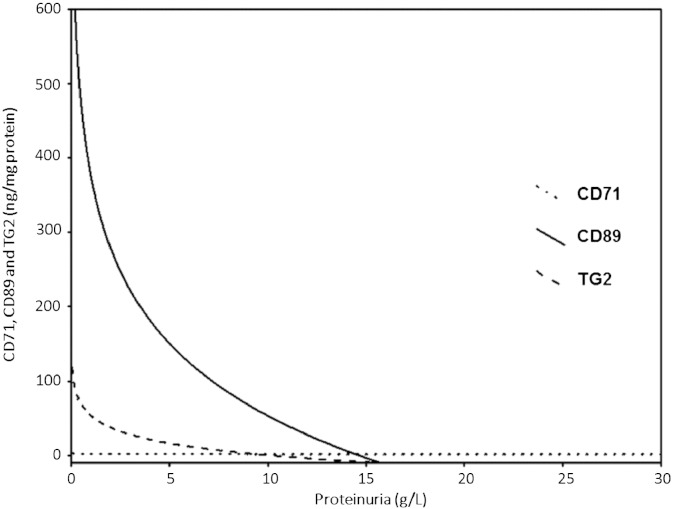

A significant correlation between urinary CD89 and urinary TG2 (r = 0.711, P < 0.001) was observed in the study patients. Furthermore, significant correlations between proteinuria and urinary CD89 (r = − 0.585, P < 0.001), and proteinuria and urinary TG2 (r = − 0.620, P < 0.001) were observed, but not for proteinuria and urinary CD71 (r = 0.047, P = 0.526). Fig. 3 shows the logarithmic relationships among proteinuria (g/L), urinary CD71 (ng/mg protein), urinary CD89 (ng/mg protein) and urinary TG2 (ng/mg protein) in the study patients.

Fig. 3.

Logarithmic relationships among proteinuria (g/L), urinary CD71 (ng/mg protein), urinary CD89 (ng/mg protein) and urinary TG2 (ng/mg protein) in the study patients.

4. Discussion

The present study establishes the value of urinary CD89 and TG2 as new and non-invasive biomarkers useful for identifying of active IgAN/HSPN. Although previous studies have indicated the role of CD89 and TG2 in the pathogenesis of IgAN [1], [14], [15], [16], this study reports for the first time the measurement of urinary CD89 and TG2 in patients with IgAN/HSPN. Actually, anatomopathological analysis of renal biopsies is required for the definitive diagnosis of IgAN or HSPN [1], [29], [30], [31], [32]. However, a renal biopsy is frequently not performed for different reasons and has some limitations in the assessment of disease activity [30], [31]. For this reason, there is an urgent need for reliable noninvasive biomarkers that might be applicable for detecting and monitoring of IgAN/HSPN.

The major findings of the present study are that urinary CD89 and urinary TG2 were decreased in patients with active IgAN/HSPN compared to subjects with a partial or complete remission of IgAN/HSPN. In addition, both urinary biomarkers have the ability to discriminate active from inactive IgAN/HSPN. It is well established that the aberrant glycosylated IgA1 in IgAN/HSPN leads to the release of soluble IgA receptors as CD89 and to the formation and amplification of circulating immune complexes [33], [34]. The soluble CD89-IgA complex deposition induces an influx of mononuclear cells into the glomerular and interstitial regions and initiates an inflammatory reaction [33]. As a consequence, there is a decrease of urinary excretion of CD89 since this molecule appears to remain in the kidney during the active phase of IgAN/HSNP. However, some studies have indicated that human mesangial cells do not express CD89 to a significant extent [35] and that IgA-CD89 complexes are not specific for primary IgAN [36]. In addition, IgA-CD89 complexes were found in the serum of healthy individuals [18] at equal amounts of IgA-CD89 complexes present in IgAN patients [36]. Although there is some conflicting evidence regarding the CD89 and CD89-IgA complexes in patients with IgAN/HSPN, the few conducted studies have evaluated these molecules especially in serum samples. Until now, there are no data in the literature regarding the urinary CD89 concentration in patients with IgAN/HSPN. We have demonstrated in this study that the urinary CD89 concentrations were significantly reduced in patients with active IgAN/HSPN. Therefore, this finding opens a new perspective for the measurement of CD89 in urine samples as a way to monitor and diagnose IgAN/HSPN. It can help to understand the pathophysiological mechanisms related to the formation and deposition of the immune complexes as CD89 plays a crucial role in the clearance of IgA-complexes [37].

Our research also demonstrated that the urinary TG2 concentration was lower in patients with active IgAN/HSPN compared to non-active IgAN/HSPN patients. During the active phase of the disease, there is a stabilization of large multimolecular complexes containing CD89, TG2, CD71 and IgA1 on the mesangial cell surface, which induce chronic stimulation of the cells with release of pro-inflammatory mediators leading to renal dysfunction [16]. With the deposition and stabilization of these multimolecular complexes in the kidney, there is a decrease in the renal excretion of CD89 and TG2. Additionally, TG2 stabilized in the mesangium can contribute to the development of renal fibrosis [38], [39] and vascular calcification [40], leading to a decline in renal function. Furthermore, patients with active IgAN/HSPN had significantly higher IgA/CD89, IgA/TG2 and IgA/CD89xTG2 ratios compared with IgAN/HSPN patients in complete or partial remission. In contrast, CD89xTG2 values were lower in patients with active IgAN/HSPN compared with IgAN/HSPN patients in complete or partial remission. The CD89xTG2 had a high ability to discriminate active from inactive IgAN/HSPN, as demonstrated in the CD89xTG2/proteinuria ratio and in the CD89xTG2/urinary creatinine ratio. These results demonstrate that differences become more significant and the performance to discriminate the active phase of the disease is slightly higher when mathematical formulas involving both CD89 and TG2 are evaluated.

Moreover, a significant positive correlation between urinary CD89 and urinary TG2 was observed. Both molecules are present in immune complexes, which are stabilized on the mesangial cell surface during the active IgAN/HSPN [16]. Significant negative correlations between proteinuria, urinary CD89 and urinary TG2 were observed, but not for urinary CD71. The urinary CD71/creatinine ratios were able to identify the active IgAN/HSPN. Aberrant glycosylated IgA1 promotes an increased expression of the mesangial CD71 and mediates mesangial deposition of nephritogenic IgA1-immune complexes [20], [21], [22] and the evaluation of urinary CD71 can add information about the course of this disease [13].

Finally, some interesting logarithmic relationships among proteinuria, urinary CD89, and urinary TG2 were observed in the present study. As illustrated in Fig. 3, a significant reduction in the urinary concentrations of CD89 and TG2 in patients with IgAN/HSPN was observed, even in the presence of a mild proteinuria. The reduction of the biomarker according to the increase of proteinuria is more prominent for CD89, which suggests that CD89 might decrease earlier than TG2 in the urine of patients with IgAN/HSPN.

A limitation of the study is that there is a lack of standardization of the measurement of CD71, CD89 and TG2, which limits the diagnostic power of the investigated parameters, because it makes it difficult to compare the results among different studies. In addition, as the analysis of the biomarkers was also performed on urine samples during the follow period of the IgAN/HSPN patients, no correlation analysis with the results of the biopsies could be performed.

In conclusion, our results showed that urinary CD89 and TG2 were decreased in patients with active IgAN/HSPN, and the measurement of these new biomarkers in urine samples can be useful to identify patients with the active disease. However, further longitudinal studies are required to investigate the potential clinical use of these promising biomarkers.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Transparency document

Transparency document.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Elke Lecocq, Tim Coussement, Karen Nys, Sylvia Van Haelst, Jonas Himpe, Barbara Deryckere, Isabelle Rogiers and Gregoire Fauvarque for their skillful assistance. R. N. Moresco was recipient of a scholarship from the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (Science without Borders Program, CNPq/Brazil).

Footnotes

The Transparency document associated with this article can be found, in online version.

References

- 1.Floege J., Moura I.C., Daha M.R. New insights into the pathogenesis of IgA nephropathy. Semin. Immunopathol. 2014;36:431–442. doi: 10.1007/s00281-013-0411-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Narita I., Gejyo F. Pathogenetic significance of aberrant glycosylation of IgA1 in IgA nephropathy. Clin. Exp. Nephrol. 2008;12:332–338. doi: 10.1007/s10157-008-0054-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Floege J. The pathogenesis of IgA nephropathy: what is new and how does it change therapeutic approaches? Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2011;58:992–1004. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sanders J.T., Wyatt R.J. IgA nephropathy and henoch-Schönlein purpura nephritis. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 2008;20:163–170. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e3282f4308b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kiryluk K., Moldoveanu Z., Sanders J.T., Eison T.M., Suzuki H., Julian B.A. Aberrant glycosylation of IgA1 is inherited in both pediatric IgA nephropathy and henoch-Schönlein purpura nephritis. Kidney Int. 2011;80:79–87. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Appel G.B., Waldman M. The IgA nephropathy treatment dilemma. Kidney Int. 2006;69:1939–1944. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rocchetti M.T., Centra M., Papale M., Bortone G., Palermo C., Centonze D. Urine protein profile of IgA nephropathy patients may predict the response to ACE-inhibitor therapy. Proteomics. 2008;8:206–216. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200700492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meadow S.R., Scott D.G. Berger disease: henoch–Schönlein syndrome without the rash. J. Pediatr. 1985;106:27–32. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(85)80459-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Waldo F.B. Is henoch-Schönlein purpura the systemic form of IgA nephropathy? Am. J. Kidney Dis. 1988;12:373–377. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(88)80028-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mestecky J., Tomana M., Moldoveanu Z., Julian B.A., Suzuki H., Matousovic K. Role of aberrant glycosylation of IgA1 molecules in the pathogenesis of IgA nephropathy. Kidney Blood Press. Res. 2008;31:29–37. doi: 10.1159/000112922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Novak J., Moldoveanu Z., Renfrow M.B., Yanagihara T., Suzuki H., Raska M. IgA nephropathy and henoch-schoenlein purpura nephritis: aberrant glycosylation of IgA1, formation of IgA1-containing immune complexes, and activation of mesangial cells. Contrib. Nephrol. 2007;157:134–138. doi: 10.1159/000102455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Suzuki H., Fan R., Zhang Z., Brown R., Hall S., Julian B.A. Aberrantly glycosylated IgA1 in IgA nephropathy patients is recognized by IgG antibodies with restricted heterogeneity. J. Clin. Invest. 2009;119:1668–1677. doi: 10.1172/JCI38468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Delanghe S.E., Speeckaert M.M., Segers H., Desmet K., Vande Walle J., Laecke S.V. Soluble transferrin receptor in urine, a new biomarker for IgA nephropathy and henoch-Schönlein purpura nephritis. Clin. Biochem. 2013;46:591–597. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2013.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Monteiro R.C., Moura I.C., Launay P., Tsuge T., Haddad E., Benhamou M. Pathogenic significance of IgA receptor interactions in IgA nephropathy. Trends Mol. Med. 2002;8:464–468. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4914(02)02405-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ben Mkaddem S., Rossato E., Heming N., Monteiro R.C. Anti-inflammatory role of the IgA Fc receptor (CD89): from autoimmunity to therapeutic perspectives. Autoimmun. Rev. 2013;12:666–669. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2012.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berthelot L., Papista C., Maciel T.T., Biarnes-Pelicot M., Tissandie E., Wang P.H. Transglutaminase is essential for IgA nephropathy development acting through IgA receptors. J. Exp. Med. 2012;209:793–806. doi: 10.1084/jem.20112005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moresco R.N., Speeckaert M.M., Delanghe J.R. Diagnosis and monitoring of IgA nephropathy: the role of biomarkers as an alternative to renal biopsy. Autoimmun. Rev. 2015;14:847–853. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2015.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van der Boog P.J., van Zandbergen G., De Fijter J.W., Klar-Mohamad N., van Seggelen A., Brandtzaeg P. Fc alpha RI/CD89 circulates in human serum covalently linked to IgA in a polymeric state. J. Immunol. 2002;168:1252–1258. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.3.1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leung J.C., Tsang A.W., Chan D.T., Lai K.N. Absence of CD89, polymeric immunoglobulin receptor, and asialoglycoprotein receptor on human mesangial cells. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2000;11:241–249. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V112241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moura I.C., Arcos-Fajardo M., Sadaka C., Leroy V., Benhamou M., Novak J. Glycosylation and size of IgA1 are essential for interaction with mesangial transferrin receptor in IgA nephropathy. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2004;15:622–634. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000115401.07980.0c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Monteiro R.C. Pathogenic role of IgA receptors in IgA nephropathy. Contrib. Nephrol. 2007;157:64–69. doi: 10.1159/000102306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moura I.C., Benhamou M., Launay P., Vrtovsnik F., Blank U., Monteiro R.C. The glomerular response to IgA deposition in IgA nephropathy. Semin. Nephrol. 2008;28:88–95. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2007.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Galla J.H. IgA nephropathy. Kidney Int. 1995;47:377–387. doi: 10.1038/ki.1995.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barbour S.J., Espino-Hernandez G., Reich H.N., Coppo R., Roberts I.S., Feehally J. The MEST score provides earlier risk prediction in IgA nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2015 doi: 10.1038/ki.2015.322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Counahan R., Winterborn M.H., White R.H., Heaton J.M., Meadow S.R., Bluett N.H. Prognosis of henoch-Schönlein nephritis in children. Br. Med. J. 1977;ii:11–14. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.6078.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mohey H., Laurent B., Mariat C., Berthoux F. Validation of the absolute renal risk of dialysis/death in adults with IgA nephropathy secondary to henoch-Schönlein purpura: a monocentric cohort study. BMC Nephrol. 2013;14:169. doi: 10.1186/1471-2369-14-169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Orsonneau J.L., Douet P., Massoubre C., Lustenberger P., Bernard S. An improved pyrogallol red-molybdate method for determining total urinary protein. Clin. Chem. 1989;35:2233–2236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Levey A.S., Stevens L.A., Schmid C.H., Zhang Y.L., Castro A.F., 3rd, Feldman H.I. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009;150:604–612. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wyatt R.J., Julian B.A. IgA nephropathy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013;368:2402–2414. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1206793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Julian B.A., Wittke S., Haubitz M., Zürbig P., Schiffer E., McGuire B.M. Urinary biomarkers of IgA nephropathy and other IgA associated renal diseases. World J. Urol. 2007;25:467–476. doi: 10.1007/s00345-007-0192-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Suzuki Y., Suzuki H., Makita Y., Takahata A., Takahashi K., Muto M. Diagnosis and activity assessment of immunoglobulin A nephropathy: current perspectives on noninvasive testing with aberrantly glycosylated immunoglobulin A-related biomarkers. Int. J. Nephrol. Renov. Dis. 2014;7:409–414. doi: 10.2147/IJNRD.S50513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kawasaki Y. The pathogenesis and treatment of pediatric henoch–Schönlein purpura nephritis. Clin. Exp. Nephrol. 2011;15:648–657. doi: 10.1007/s10157-011-0478-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Launay P., Grossetête B., Arcos-Fajardo M., Gaudin E., Torres S.P., Beaudoin L. Fc alpha receptor (CD89) mediates the development of immunoglobulin A (IgA) nephropathy (Berger's disease). evidence for pathogenic soluble receptor-iga complexes in patients and CD89 transgenic mice. J. Exp. Med. 2000;191:1999–2009. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.11.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tissandié E., Morelle W., Berthelot L., Vrtovsnik F., Daugas E., Walker F. Both IgA nephropathy and alcoholic cirrhosis feature abnormally glycosylated IgA1 and soluble CD89-IgA and IgG-IgA complexes: common mechanisms for distinct diseases. Kidney Int. 2011;80:1352–1363. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Westerhuis R., Van Zandbergen G., Verhagen N.A., Klar-Mohamad N., Daha M.R., van Kooten C. Human mesangial cells in culture and in kidney sections fail to express Fc alpha receptor (CD89) J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 1999;10:770–778. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V104770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van der Boog P.J., De Fijter J.W., Van Kooten C., Klar-Mohamad N., Oortwijn B., Bos N.A. Complexes of IgA with FcalphaRI/CD89 are not specific for primary IgA nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2003;63:514–521. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00756.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grossetête B., Launay P., Lehuen A., Jungers P., Bach J.F., Monteiro R.C. Down-regulation of Fc alpha receptors on blood cells of IgA nephropathy patients: evidence for a negative regulatory role of serum IgA. Kidney Int. 1998;53:1321–1335. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1998.00885.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shweke N., Boulos N., Jouanneau C., Vandermeersch S., Melino G., Dussaule J.C. Tissue transglutaminase contributes to interstitial renal fibrosis by favoring accumulation of fibrillar Collagen through TGF-beta activation and cell infiltration. Am. J. Pathol. 2008;173:631–642. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.080025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chou C.Y., Streets A.J., Watson P.F., Huang L., Verderio E.A., Johnson T.S. A crucial sequence for transglutaminase type 2 extracellular trafficking in renal tubular epithelial cells lies in its N-terminal beta-sandwich domain. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:27825–27835. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.226340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen N.X., O'Neill K., Chen X., Kiattisunthorn K., Gattone V.H., Moe S.M. Transglutaminase 2 accelerates vascular calcification in chronic kidney disease. Am. J. Nephrol. 2013;37:191–198. doi: 10.1159/000347031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Transparency document.