Abstract

Background & aims

Blood aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine transaminase (ALT) levels are the most frequently reliable biomarkers of liver injury. Although AST and ALT play central roles in glutamate production as transaminases, peripheral blood levels of AST and ALT have been regarded only as liver injury biomarkers. Glutamate is a principal excitatory neurotransmitter, which affects memory functions in the brain. In this study, we investigated the impact of blood transaminase levels on blood glutamate concentration and memory.

Methods

Psychiatrically, medically, and neurologically healthy subjects (n = 514, female/male: 268/246) were enrolled in this study through local advertisements. Plasma amino acids (glutamate, glutamine, glycine, d-serine, and l-serine) were measured using a high performance liquid chromatography system. The five indices, verbal memory, visual memory, general memory, attention/concentration, and delayed recall of the Wechsler Memory Scale-Revised were used to measure memory functions.

Results

Both plasma AST and ALT had a significant positive correlation with plasma glutamate levels. Plasma AST and ALT levels were significantly negatively correlated with four of five memory functions, and plasma glutamate was significantly negatively correlated with three of five memory functions. Multivariate analyses demonstrated that plasma AST, ALT, and glutamate levels were significantly correlated with memory functions even after adjustment for gender and education.

Conclusions

As far as we know, this is the first report which could demonstrate the impact of blood transaminase levels on blood glutamate concentration and memory functions in human. These findings are important for the interpretation of obesity-induced metabolic syndrome with elevated transaminases and cognitive dysfunction.

Abbreviations: AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; BBB, blood brain barrier; Gln, glutamine; Glu, glutamate; Gly, glycine; GOT, glutamate-oxalacetate transaminase; GPT, glutamate-pyruvate transaminase; Mets, metabolic syndrome; MSG, monosodium glutamate; NAFL, nonalcoholic fatty liver; NAFLD, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease; NASH, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis; WMS-R, Wechsler Memory Scale-Revised

Keywords: Aspartate aminotransferase, Alanine aminotransferase, Glutamate, Memory function

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Peripheral blood levels of AST and ALT have been regarded only as liver injury biomarkers.

-

•

In healthy human subjects, both plasma AST and ALT had significant positive correlations with plasma glutamate levels.

-

•

Plasma AST, ALT, and glutamate levels were significantly negatively correlated with memory functions in univariate and multivariate analyses.

-

•

As far as we know, this is the first report which could demonstrate the impact of blood transaminase levels on blood glutamate concentration and memory functions in human.

1. Introduction

Peripheral blood levels of aspartate aminotransferase [AST/GOT (glutamate-oxalacetate transaminase)] and alanine transaminase [ALT/GPT (glutamate-pyruvate transaminase)] have been regarded simply as liver injury biomarkers [1], [2]. In various etiologies from viral hepatitis to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), blood AST and ALT levels are elevated and are frequently reliable biomarkers of hepatotoxic effects. However, AST and ALT also play central roles in amino acid metabolism as transaminases [1], [2]. Specifically, AST and ALT catalyze transamination from aspartate or alanine to glutamate and are important positive regulators of tissue glutamate levels [1], [3]. In addition, a previous report demonstrated that transaminases in human blood have efficient enzymatic transamination activity [4]. However, there are no reports that have demonstrated the correlation between blood transaminases and glutamate levels in human subjects.

Glutamate plays pivotal roles in many physiological brain functions including memory [5], [6]. Glutamate is a principal excitatory neurotransmitter of the central nervous system [7]. Memory dysfunction can affect our cognitive function, and peripheral blood glutamate levels have been reported to be altered in many cognitive function disorders, such as Asperger's syndrome [8] and schizophrenia [9]. The glutamate concentration in the blood is thought to have effects on brain function despite the existence of the blood brain barrier (BBB). Indeed, peripheral blood glutamate levels positively correlate with the concentration of glutamate in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) [10], [11]. In rodent models, systemic administration of monosodium glutamate (MSG) induces BBB breakdown through its hypertonic effect [12]. There have been many reports that have demonstrated that glutamate and glutamatergic receptor have significant effects on memory functions [13], [14]. One of the mechanisms by which glutamate affects memory function is through glutamatergic induction of long term potentiation (LTP) of synaptic strength thorough activation of calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) [15].

In consideration of these findings, we hypothesized that blood transaminase levels could change the blood glutamate concentration and would have significant effects on cognitive functions in humans. To confirm our hypothesis, we investigated the relationship between blood transaminase (AST and ALT) levels, brain function-related amino acid levels [glutamine, glutamate, glycine, d-serine, and l-serine], and memory functions (verbal memory, visual memory, general memory, attention/concentration, and delayed recall) in 514 healthy subjects without any psychological diseases or current medication.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Ethical committee approval

The protocol and informed consent document were approved by the institutional review boards at Osaka University Graduate School of Medicine and Chiba University (No. 592). Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects and the study was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration.

2.2. Memory function assessment and laboratory measurements

A full version of the WMS-R [16], [17], a measure that is generally used to measure memory, was administered to the subjects, as previously described [18]. The five indices, verbal memory, visual memory, general memory, attention/concentration, and delayed recall of the WMS-R were used in the analysis. The scores of indices were corrected by age. Memory functions were positively correlated with the scores of indices. The mean value of these scores was set to 100, and one standard deviation (S.D.) was defined as 15. Blood biochemical variables [aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT)] were measured with a conventional automated analyzer (Mitsubishi MEDIENCE, Kobe, Japan).

2.3. Determination of plasma amino acid levels

Measurement of plasma d-serine and l-serine were carried out using a column-switching high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) system (Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan) [19], [20]. Measurement of plasma glutamine, glutamate, and glycine was carried out using an HPLC system with fluorescence detection, as previously described [21].

2.4. Study subjects

A total of 514 healthy volunteers were enrolled in this study, as previously described [22], [23]. The study subjects were recruited through local advertisements. Psychiatrically, medically, and neurologically healthy subjects were evaluated using the structured clinical interview for DSM-IV (SCID), non-patient version. Subjects were excluded if they had neurological or medical conditions that could potentially affect the central nervous system, such as atypical headache, head trauma with loss of consciousness, chronic lung disease, kidney disease, chronic thyroid disease, active stage cancer, cerebrovascular disease, epilepsy, or seizures. The criteria for exclusion from this study also included a history of known hepatic diseases and virus hepatitis marker positive subjects (HCV-antibody and HBs antigen). The detailed information regarding the subjects is shown in Table 1. Briefly, the gender ratio was 268/246 (female/male), mean age was 31.8 ± 12.3 years old, and mean education length was 15.0 ± 1.8 years.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study subjects.

| Number | 514 |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 31.8 ± 12.3 |

| Gender (F/M) | 268/246 |

| Education (years) | 15.0 ± 1.8 |

| AST (U/L) | 19.1 ± 6.6 |

| ALT (U/L) | 17.3 ± 12.9 |

| Gln (μM) | 528.4 ± 72.7 |

| Gly (μM) | 223.0 ± 54.8 |

| Glu (μM) | 32.9 ± 16.4 |

| d-Serine (μM) | 0.95 ± 0.32 |

| l-Serine (μM) | 119.7 ± 27.4 |

| Verbal memory | 112.9 ± 13.7 |

| Visual memory | 105.0 ± 9.6 |

| General memory | 112.4 ± 13.0 |

| Attention/concentration | 110.1 ± 12.7 |

| Delayed recall | 110.0 ± 12.2 |

Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (S.D.).

Abbreviations: AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; Gln, glutamine; Gly, glycine; Glu, glutamate.

2.5. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using JMP Pro 11.0 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) and SPSS 20.0 (SPSS Japan Inc., Tokyo, Japan) software. Variables were expressed as mean ± S.D. As AST, ALT, glutamate, glycine, d-serine, and l-serine did not show a Gaussian distribution, these parameters were common log-transformed before analysis. The Wilcoxon test and Spearman R correlations were used for the statistical analyses in this study. Multivariate logistic regression analyses were conducted to identify parameters that significantly contribute to each memory function. Differences were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Plasma transaminase (AST and ALT) levels significantly correlate with the plasma glutamate level

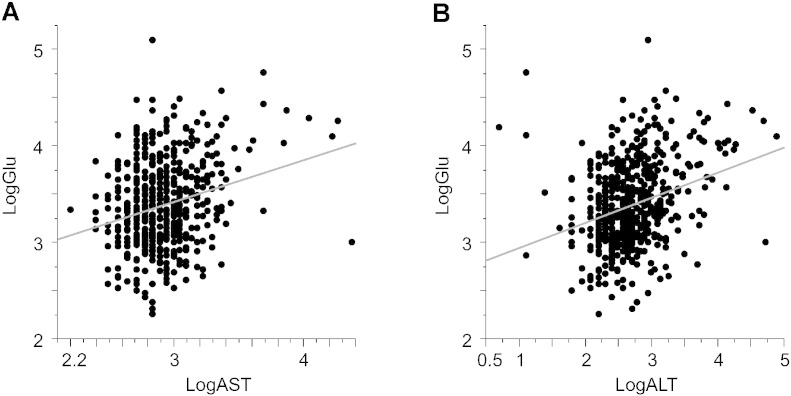

AST and ALT are transaminases which catalyze transamination from aspartate or alanine to glutamate. However, as far as we know, there are no reports that have investigated the relationship between blood transaminase and glutamate levels. First, we investigated the correlation between plasma transaminase levels and glutamate levels in our subjects. As expected, we found a significant and positive correlation between transaminases (AST and ALT) and glutamate (AST: R = 0.19, P = 1.1 × 10− 5; ALT: R = 0.30, P = 5.0 × 10− 12) (Fig. 1, Table 2). Both plasma AST and ALT levels had significant negative correlations with plasma glycine and l-serine [AST: R = − 0.12, P = 7.2 × 10− 3 (glycine), R = − 0.22, P = 7.5 × 10− 7 (l-serine); ALT: R = − 0.16, P = 3.5 × 10− 4 (glycine), R = − 0.24, P = 6.5 × 10− 8 (l-serine)]. There were no significant correlations between plasma transaminases and other amino acids [(AST: R = − 0.043, P = 0.34 (glutamine), R = 0.074, P = 0.095 (d-serine); ALT: R = − 5.3 × 10− 3, P = 0.91 (glutamine), R = 0.013, P = 0.77 (d-serine)]. A previous report has demonstrated that blood transaminases have enzymatic transamination activity [4]. Our results indicate that the blood transaminase concentration defines the concentration of peripheral blood glutamate in human subjects.

Fig. 1.

Relationships between plasma transaminase level and plasma glutamate level.

Relationships between the plasma glutamate level and (A) plasma AST level and (B) plasma ALT level. LogGlu, common log-transformed glutamate; LogAST, common log-transformed AST; LogALT, common log-transformed ALT.

Table 2.

Correlation between plasma transaminases and amino acids.

| AST |

ALT |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| R | P value | R | P value | |

| Glu | 0.19 | 1.1 × 10− 5 | 0.30 | 5.0 × 10− 12 |

| Gln | − 0.043 | 0.34 | − 0.0053 | 0.91 |

| Gly | − 0.12 | 7.2 × 10− 3 | − 0.16 | 3.5 × 10− 4 |

| d-Serine | 0.074 | 0.095 | 0.013 | 0.77 |

| l-Serine | − 0.22 | 7.5 × 10− 7 | − 0.24 | 6.5 × 10− 8 |

3.2. The correlation among plasma transaminase levels, amino acid levels, and memory functions

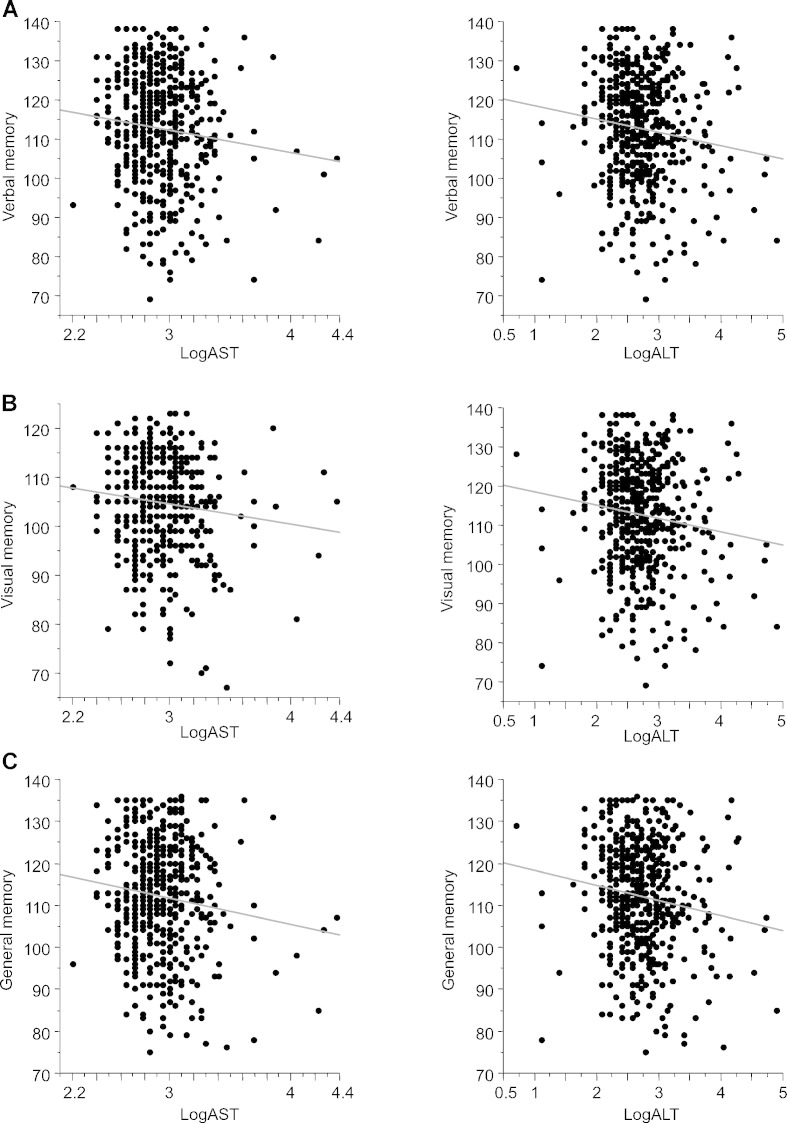

Next, we investigated the relationships between plasma transaminase levels and memory functions (Fig. 2) and between amino acid levels and memory functions (Table 3). Both plasma AST and ALT levels were significantly and negatively correlated with four of five memory functions [verbal memory: R = − 0.11, P = 0.014 (AST), R = − 0.13, P = 4.0 × 10− 3 (ALT); visual memory: R = − 0.11, P = 0.012 (AST), R = − 0.11, P = 0.014 (ALT); general memory: R = − 0.13, P = 0.0044 (AST), R = − 0.14, P = 0.0013 (ALT); and delayed recall: R = − 0.13, P = 0.0033 (AST), R = − 0.15, P = 4.0 × 10− 4 (ALT)] (Fig. 2A, B, C, E), but were not correlated with attention/concentration (R = − 0.022, P = 0.61) (Fig. 2D). Plasma glutamate levels demonstrated a similar correlation as transaminases with memory functions (Table 3). Other amino acids (glutamine, glycine, d-serine, and l-serine) did not correlate with verbal, visual, or general memory or delayed recall.

Fig. 2.

Relationships between plasma transaminase level and memory functions.

(A) Relationship between plasma transaminase level and verbal memory.

(B) Relationship between plasma transaminase level and visual memory.

(C) Relationship between plasma transaminase level and general memory.

(D) Relationship between plasma transaminase level and attention/concentration.

(E) Relationship between plasma transaminase level and delayed recall.

Table 3.

Correlation between plasma amino acids and memory functions.

| Glu |

Gln |

Gly |

D-Serine |

L-Serine |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R | P value | R | P value | R | P value | R | P value | R | P value | |

| Verbal memory | − 0.12 | 8.6 × 10− 3 | − 0.031 | 0.48 | − 0.018 | 0.69 | 0.05 | 0.25 | − 0.006 | 0.90 |

| Visual memory | − 0.084 | 0.056 | − 0.058 | 0.19 | − 7.0 × 10− 4 | 0.99 | 0.046 | 0.30 | 0.024 | 0.59 |

| General memory | − 0.13 | 3.4 × 10− 3 | − 0.038 | 0.39 | − 0.011 | 0.80 | 0.059 | 0.18 | − 0.006 | 0.90 |

| Attention/concentration | 0.043 | 0.33 | 0.088 | 0.046 | − 0.031 | 0.49 | 0.048 | 0.28 | − 0.098 | 0.027 |

| Delayed recall | − 0.12 | 7.8 × 10− 3 | − 0.0096 | 0.83 | − 9.0 × 10− 3 | 0.84 | 0.092 | 0.037 | − 0.003 | 0.95 |

As shown above, plasma AST, ALT, and glutamate levels were significantly correlated with verbal, visual, and general memory and delayed recall. To exclude the effects of gender differences and level of education, we conducted multivariate analyses for each memory function adjusted for gender and years of education (Table 4A, B, C). Plasma AST level was a significant determinant for verbal, visual, and general memory and delayed recall. Plasma ALT level was a significant determinant of verbal and general memory and delayed recall. Plasma glutamate level was a significant determinant of verbal, general memory, and delayed recall. These results indicate that plasma AST, ALT, and glutamate levels are significantly correlated with memory functions even after adjustment for gender and education length.

Table 4.

Multiple logistic regression analyses of factors associated with each memory function.

| Factors | Estimated value | S.E. | t value | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (A) Model 1 (gender, education, AST) | ||||

| Verbal memory | ||||

| Gender (male) | − 0.48 | 0.62 | − 0.77 | 0.44 |

| Education (years) | 0.83 | 0.34 | 2.45 | 0.014 |

| AST (U/L) | − 0.23 | 0.092 | − 2.5 | 0.013 |

| Visual memory | ||||

| Gender (male) | − 0.53 | 0.44 | − 1.23 | 0.22 |

| Education length (years) | 0.063 | 0.24 | 0.27 | 0.79 |

| AST (U/L) | − 0.15 | 0.065 | − 2.26 | 0.024 |

| General memory | ||||

| Gender (male) | − 0.51 | 0.59 | − 0.87 | 0.38 |

| Education (years) | 0.69 | 0.32 | 2.15 | 0.032 |

| AST | − 0.25 | 0.087 | − 2.83 | 4.9 × 10− 3 |

| Delayed recall | ||||

| Gender (male) | − 0.57 | 0.55 | − 1.04 | 0.30 |

| Education (years) | 0.89 | 0.30 | 2.99 | 2.9 × 10− 3 |

| AST (U/L) | − 0.23 | 0.082 | − 2.8 | 5.3 × 10− 3 |

| (B) Model 2 (gender, education, ALT) | ||||

| Verbal memory | ||||

| Gender (male) | − 0.23 | 0.64 | − 0.36 | 0.72 |

| Education (years) | 0.82 | 0.34 | 2.43 | 0.016 |

| ALT (U/L) | − 0.14 | 0.048 | − 2.91 | 3.7 × 10− 3 |

| Visual memory | ||||

| Gender (male) | − 0.50 | 0.45 | − 1.11 | 0.27 |

| Education (years) | 0.068 | 0.24 | 0.29 | 0.77 |

| ALT (U/L) | − 0.053 | 0.034 | − 1.58 | 0.12 |

| General memory | ||||

| Gender (male) | − 0.28 | 0.60 | − 0.47 | 0.64 |

| Education (years) | 0.68 | 0.32 | 2.13 | 0.034 |

| ALT (U/L) | − 0.14 | 0.046 | − 3.04 | 2.5 × 10− 3 |

| Delayed recall | ||||

| Gender (male) | − 0.36 | 0.56 | − 0.63 | 0.53 |

| Education (years) | 0.88 | 0.30 | 2.97 | 3.2 × 10− 3 |

| ALT (U/L) | − 0.13 | 0.043 | − 3.03 | 2.6 × 10− 3 |

| (C) Model 3 (gender, education, glutamate) | ||||

| Verbal memory | ||||

| Gender (male) | − 0.035 | 0.66 | − 0.05 | 0.96 |

| Education (years) | 0.86 | 0.34 | 2.55 | 0.011 |

| Glu (μM) | − 0.11 | 0.039 | − 2.79 | 5.5 × 10− 3 |

| Visual memory | ||||

| Gender (male) | − 0.46 | 0.47 | − 1 | 0.32 |

| Education (years) | 0.084 | 0.24 | 0.35 | 0.72 |

| Glu (μM) | − 0.035 | 0.028 | − 1.28 | 0.20 |

| General memory | ||||

| Gender (male) | − 0.071 | 0.63 | − 0.11 | 0.91 |

| Education (years) | 0.72 | 0.32 | 2.26 | 0.024 |

| Glu (μM) | − 0.11 | 0.037 | − 3.01 | 2.8 × 10− 3 |

| Delayed recall | ||||

| Gender (male) | − 0.24 | 0.59 | − 0.42 | 0.68 |

| Education (years) | 0.92 | 0.30 | 3.09 | 2.1 × 10− 3 |

| Glu (μM) | − 0.091 | 0.035 | − 2.6 | 9.6 × 10− 3 |

Abbreviations: S.E. standard error.

4. Discussion

In the present study, we demonstrated the correlations among plasma transaminase levels, amino acid levels, and memory functions. As far as we know, our study is the first report to demonstrate that plasma AST and ALT have significant positive correlations with peripheral blood glutamate concentrations and significant negative correlations with memory functions in healthy subjects. In addition, we found that plasma glutamate levels also have significant and negative relationships with memory functions. Our findings indicate that plasma transaminase levels have significant impact on memory functions through changes in plasma glutamate concentration.

AST and ALT have been known to have critical roles in glutamate production [1], [3], [4]. Glutamate is known to be the major excitatory neurotransmitter of the central nervous system [7] and plays many important roles in brain functions. Plasma glutamate levels positively correlate with the CSF glutamate concentration [10], [11]. In male patients with schizophrenia, plasma levels of glutamate are elevated compared with those in control subjects [9]. A meta-analysis has also demonstrated that peripheral glutamate levels in schizophrenia patients are significantly higher than in controls [24]. In addition, significant correlations have been reported in various cognitive disorder diseases between brain glutamate levels and disease symptoms [13]. Therefore, although we did not measure CSF glutamate levels, increased plasma glutamate levels would have significant effects on brain functions. On the contrary, there have been some reports that have demonstrated no significant relationships between blood glutamate levels and cognitive functions in schizophrenia patients [25], [26], [27]. Drugs used in these patients would not have any effects on serum glutamate concentration and cognitive functions, and the relationships would be diminished in these patients. In our study, we have demonstrated significantly positive relationships between peripheral blood glutamate and these transaminases. We also found that both plasma transaminases and glutamate levels in healthy subjects were negatively correlated with memory functions. These findings indicate that elevation of plasma transaminase levels induces memory dysfunction through plasma glutamate level elevation in healthy subjects under no medication.

Recent studies have demonstrated that brain dysfunction induces food addiction and obesity [28], [29]. Binge eating disorder is characterized by a compulsive engagement in excessive food consumption which results in obesity [30]. In particular, glutamate and glutamate receptors have been found to play a role in the regulation of food intake and modification of binge eating (known as the “glutamate hypothesis”) [31], [32], [33]. MSG administration in rodent models is often used to induce overeating and obesity [34], [35]. In humans, glutamate N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor agonist suppresses food intake, and the NMDA receptor antagonist, acamprosate, has been found to decrease food dependency and weight gain [32], [36], [37], [38]. These findings indicate that glutamatergic system regulation may be useful for the treatment of eating disorders and obesity. In the DSM-4 (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Forth Edition), substance addiction is defined as a cluster of cognitive, behavioral, and psychological symptoms associated with the continuous use of a substance despite significant problems caused by the substance [39]. While obesity is characterized by overeating and the inability to stop overeating despite the desire to do so, these symptoms are remarkably parallel to those described in the DSM-4 for substance addiction. Therefore, some forms of obesity should be included as a mental disorder driven by a food addiction [40]. Obesity is not only closely associated with fatty liver disease, but also induces cognitive dysfunction [41], [42], [43]. Considered together, transaminase elevation in obesity-related fatty liver patients may trigger cognitive dysfunction and food addiction and might induce further weight gain.

Other amino acids, such as glutamine, glycine, d-serine, and l-serine, also have significant effects on brain functions [21], [44], [45]. Among these amino acids, d-serine and glycine are known as co-agonists of the NMDA receptor, and facilitate excitatory glutamatergic neurotransmission at synapses within the nervous systems [46], [47], [48]. Because phencyclidine, a non-competitive antagonist of the NMDA receptor, induces schizophrenia-like symptoms in healthy subjects, recent research on schizophrenia has focused on hypofunction of the NMDA receptor. However, no significant correlations have been cited between these amino acids (glycine and d-serine) and memory functions in our study subjects.

Obesity is a central and causal component of metabolic syndrome (Mets) and is almost always induced by overeating resulting from food addiction [29], [49]. Mets, a cluster of obesity-related diseases including NAFLD, is a critical growing medical problem in industrialized countries of the world. NAFLD is among the most common causes of chronic liver disease in obese people [41]. NAFLD patients have food dependency [50], and weight reduction is useful for the prevention of NAFLD progression [51], [52]. However, clinical hepatologists often encounter NAFLD patients who do not stop overeating in spite of frequent nutritional guidance [50]. In the rodent fatty liver model, it has been reported that memory performance is impaired and exenatide (glucagon-like peptide-1 analog) treatment improves memory performance [53]. In addition, 85% of NAFLD patients have mild or moderate cognitive dysfunction [54]. We suppose a number of the subjects in the present study with elevated transaminase levels would have NAFLD. In NAFLD patients, cognitive dysfunction induced by transaminase elevation has some effect on their food dependency. A cross-sectional and longitudinal study is needed to elucidate the relationships among blood transaminase levels, glutamate levels, and memory functions in NAFLD patients.

Our study has some limitations. First, our study is a cross-sectional study. The effects of a plasma transaminase level change on plasma glutamate levels and memory functions were not elucidated. Longitudinal studies are needed to investigate this issue in more detail. Second, our study lacks the inclusion of factors related to Mets, such as body weight, blood sugar, and lipid levels. Therefore, the effects of factors other than transaminase and glutamate levels on memory functions were not assessed in our study. However, our study has a strong advantage in terms of the large number of healthy subjects (n = 514) included. Our healthy subjects were under no medication and did not have any past history of psychiatric diseases with memory dysfunction. Therefore, we believe a meaningful assessment of plasma transaminases, amino acids, and memory functions were performed in the present study.

In conclusion, we demonstrate the significant relationships among plasma transaminases (AST and ALT), plasma glutamate levels, and memory functions in 514 healthy subjects. Considering our findings, we hypothesize that plasma transaminase elevation in obesity-induced fatty liver patients evokes memory function disorders and leads to food dependency, which results in further obesity (vicious liver-brain cycle). Breaking up this vicious cycle should ameliorate metabolic syndrome progression.

Transparency Document

Transparency document.

Acknowledgments

A part of this work carried out care of support from Brain/MINDS and Comprehensive Research on Disability Health and Welfare by AMED, KAKENHI [25293250-Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B), 15H04810-Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B), 23659565-Grant-in-Aid for Challenging Exploratory Research], and Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Innovative Areas (Comprehensive Brain Science Network) by MEXT. The funders had no role in study design, data collection, and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

The authors disclose no conflicts of interests.

The Transparency Document associated with this article can be found, in the online version.

References

- 1.Ozer J., Ratner M., Shaw M., Bailey W., Schomaker S. The current state of serum biomarkers of hepatotoxicity. Toxicology. 2008;245:194–205. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2007.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sookoian S., Pirola C.J. Liver enzymes, metabolomics and genome-wide association studies: from systems biology to the personalized medicine. World J. Gastroenterol. 2015;21:711–725. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i3.711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gallagher F.A., Kettunen M.I., Day S.E., Hu D.E., Karlsson M., Gisselsson A., Lerche M.H., Brindle K.M. Detection of tumor glutamate metabolism in vivo using (13)C magnetic resonance spectroscopy and hyperpolarized [1-(13)C]glutamate. Magn. Reson. Med. 2011;66:18–23. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ladue J.S., Wroblewski F., Karmen A. Serum glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase activity in human acute transmural myocardial infarction. Science. 1954;120:497–499. doi: 10.1126/science.120.3117.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reis H.J., Guatimosim C., Paquet M., Santos M., Ribeiro F.M., Kummer A., Schenatto G., Salgado J.V., Vieira L.B., Teixeira A.L., Palotas A. Neuro-transmitters in the central nervous system & their implication in learning and memory processes. Curr. Med. Chem. 2009;16:796–840. doi: 10.2174/092986709787549271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kalivas P.W. The glutamate homeostasis hypothesis of addiction. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2009;10:561–572. doi: 10.1038/nrn2515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coyle J., Leski M., Morrison J. In: The Diverse Roles of l-Glutamic Acid in Brain Signal Transduction. Davis K., Charney D., Coyle J., editors. 2002. pp. 71–90. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aldred S., Moore K.M., Fitzgerald M., Waring R.H. Plasma amino acid levels in children with autism and their families. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2003;33:93–97. doi: 10.1023/a:1022238706604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tomiya M., Fukushima T., Watanabe H., Fukami G., Fujisaki M., Iyo M., Hashimoto K., Mitsuhashi S., Toyo'oka T. Alterations in serum amino acid concentrations in male and female schizophrenic patients. Clin. Chim. Acta. 2007;380:186–190. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2007.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alfredsson G., Wiesel F., Tylec A. Relationships between glutamate and monoamine metabolites in cerebrospinal fluid and serum in healthy volunteers. Biol. Psychiatry. 1988;23:689–697. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(88)90052-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McGale E., Pye I., Stonier C., Hutchinson E., Aber G. Studies of the inter-relationship between cerebrospinal fluid and plasma amino acid concentrations in normal individuals. J. Neurochem. 1977;29:291–297. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1977.tb09621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McCall A., Glaeser B.S., Millington W., Wurtman R.J. Monosodium glutamate neurotoxicity, hyperosmolarity, and blood–brain barrier dysfunction. Neurobehav. Toxicol. 1979;1:279–283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Merritt K., McGuire P., Egerton A. Relationship between glutamate dysfunction and symptoms and cognitive function in psychosis. Front. Psychiatry. 2013;4:151. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2013.00151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Egerton A., Brugger S., Raffin M., Barker G.J., Lythgoe D.J., McGuire P.K., Stone J.M. Anterior cingulate glutamate levels related to clinical status following treatment in first-episode schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37:2515–2521. doi: 10.1038/npp.2012.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lisman J., Yasuda R., Raghavachari S. Mechanisms of CaMKII action in long-term potentiation. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2012;13:169–182. doi: 10.1038/nrn3192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sugishita M. Nihonbunkakagakusha; 2001. Japanese Wechsler Memory Scale-Revised. (Place Published) [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wechsler D. Psychological Corporation; 1987. Wechsler Memory Scale Manual, Revised. (Place Published) [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ohi K., Hashimoto R., Yasuda Y., Fukumoto M., Nemoto K., Ohnishi T., Yamamori H., Takahashi H., Iike N., Kamino K., Yoshida T., Azechi M., Ikezawa K., Tanimukai H., Tagami S., Morihara T., Okochi M., Tanaka T., Kudo T., Iwase M., Kazui H., Takeda M. The AKT1 gene is associated with attention and brain morphology in schizophrenia. World J. Biol. Psychiatry. 2013;14:100–113. doi: 10.3109/15622975.2011.591826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fukushima T., Kawai J., Imai K., Toyo'oka T. Simultaneous determination of d- and l-serine in rat brain microdialysis sample using a column-switching HPLC with fluorimetric detection. Biomed. Chromatogr. 2004;18:813–819. doi: 10.1002/bmc.394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yamada K., Ohnishi T., Hashimoto K., Ohba H., Iwayama-Shigeno Y., Toyoshima M., Okuno A., Takao H., Toyota T., Minabe Y., Nakamura K., Shimizu E., Itokawa M., Mori N., Iyo M., Yoshikawa T. Identification of multiple serine racemase (SRR) mRNA isoforms and genetic analyses of SRR and DAO in schizophrenia and d-serine levels. Biol. Psychiatry. 2005;57:1493–1503. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yamamori H., Hashimoto R., Fujita Y., Numata S., Yasuda Y., Fujimoto M., Ohi K., Umeda-Yano S., Ito A., Ohmori T., Hashimoto K., Takeda M. Changes in plasma d-serine, l-serine, and glycine levels in treatment-resistant schizophrenia before and after clozapine treatment. Neurosci. Lett. 2014;582:93–98. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2014.08.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fujino H., Sumiyoshi C., Sumiyoshi T., Yasuda Y., Yamamori H., Ohi K., Fujimoto M., Umeda-Yano S., Higuchi A., Hibi Y., Matsuura Y., Hashimoto R., Takeda M., Imura O. Performance on the Wechsler adult intelligence scale-III in Japanese patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2014;68:534–541. doi: 10.1111/pcn.12165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Horiguchi M., Ohi K., Hashimoto R., Hao Q., Yasuda Y., Yamamori H., Fujimoto M., Umeda-Yano S., Takeda M., Ichinose H. Functional polymorphism (C-824T) of the tyrosine hydroxylase gene affects IQ in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2014;68:456–462. doi: 10.1111/pcn.12157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Song J., Viggiano A., Monda M., De Luca V. Peripheral glutamate levels in schizophrenia: evidence from a meta-analysis. Neuropsychobiology. 2014;70:133–141. doi: 10.1159/000364828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Altamura C.A., Mauri M.C., Ferrara A., Moro A.R., D'Andrea G., Zamberlan F. Plasma and platelet excitatory amino acids in psychiatric disorders. Am. J. Psychiatry. 1993;150:1731–1733. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.11.1731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim J.S., Kornhuber H.H., Holzmuller B., Schmid-Burgk W., Mergner T., Krzepinski G. Reduction of cerebrospinal fluid glutamic acid in Huntington's chorea and in schizophrenic patients. Arch. Psychiatr. Nervenkr. 1970;228(1980):7–10. doi: 10.1007/BF00365738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ohnuma T., Sakai Y., Maeshima H., Higa M., Hanzawa R., Kitazawa M., Hotta Y., Katsuta N., Takebayashi Y., Shibata N., Arai H. No correlation between plasma NMDA-related glutamatergic amino acid levels and cognitive function in medicated patients with schizophrenia. Int. J. Psychiatry Med. 2012;44:17–27. doi: 10.2190/PM.44.1.b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gearhardt A.N., Corbin W.R. The role of food addiction in clinical research. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2011;17:1140–1142. doi: 10.2174/138161211795656800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Filbey F.M., Myers U.S., Dewitt S. Reward circuit function in high BMI individuals with compulsive overeating: similarities with addiction. NeuroImage. 2012;63:1800–1806. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.08.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.A. American Psychiatric Association, A.P. Association . 1980. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tata A.L., Kockler D.R. Topiramate for binge-eating disorder associated with obesity. Ann. Pharmacother. 2006;40:1993–1997. doi: 10.1345/aph.1H178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McElroy S.L., Guerdjikova A.I., Winstanley E.L., O'Melia A.M., Mori N., McCoy J., Keck P.E., Jr., Hudson J.I. Acamprosate in the treatment of binge eating disorder: a placebo-controlled trial. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2011;44:81–90. doi: 10.1002/eat.20876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maldonado-Irizarry C.S., Swanson C.J., Kelley A.E. Glutamate receptors in the nucleus accumbens shell control feeding behavior via the lateral hypothalamus. J. Neurosci. 1995;15:6779–6788. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-10-06779.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Matyskova R., Maletinska L., Maixnerova J., Pirnik Z., Kiss A., Zelezna B. Comparison of the obesity phenotypes related to monosodium glutamate effect on arcuate nucleus and/or the high fat diet feeding in C57BL/6 and NMRI mice. Physiol. Res. 2008;57:727–734. doi: 10.33549/physiolres.931274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gudino-Cabrera G., Urena-Guerrero M.E., Rivera-Cervantes M.C., Feria-Velasco A.I., Beas-Zarate C. Excitotoxicity triggered by neonatal monosodium glutamate treatment and blood–brain barrier function. Arch. Med. Res. 2014;45:653–659. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2014.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Guard D.B., Swartz T.D., Ritter R.C., Burns G.A., Covasa M. NMDA NR2 receptors participate in CCK-induced reduction of food intake and hindbrain neuronal activation. Brain Res. 2009;1266:37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Resch J.M., Maunze B., Phillips K.A., Choi S. Inhibition of food intake by PACAP in the hypothalamic ventromedial nuclei is mediated by NMDA receptors. Physiol. Behav. 2014;133:230–235. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2014.05.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McElroy S.L., Guerdjikova A.I., Mori N., O'Melia A.M. Pharmacological management of binge eating disorder: current and emerging treatment options. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 2012;8:219–241. doi: 10.2147/TCRM.S25574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.A.P. Association, A.P. Association . American psychiatric association; Washington, DC: 1994. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM) pp. 143–147. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Volkow N.D., O'Brien C.P. Issues for DSM-V: should obesity be included as a brain disorder? Am. J. Psychiatry. 2007;164:708–710. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.5.708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ford E.S., Giles W.H., Dietz W.H. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome among US adults: findings from the third National Health and Nutrition examination survey. JAMA. 2002;287:356–359. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.3.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Komulainen P., Lakka T.A., Kivipelto M., Hassinen M., Helkala E.L., Haapala I., Nissinen A., Rauramaa R. Metabolic syndrome and cognitive function: a population-based follow-up study in elderly women. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 2007;23:29–34. doi: 10.1159/000096636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rouch I., Trombert B., Kossowsky M.P., Laurent B., Celle S., Ntougou Assoumou G., Roche F., Barthelemy J.C. Metabolic syndrome is associated with poor memory and executive performance in elderly community residents: the PROOF study. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry. 2014;22:1096–1104. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2014.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mothet J.P., Le Bail M., Billard J.M. Time and space profiling of NMDA receptor co-agonist functions. J. Neurochem. 2015;135:210–225. doi: 10.1111/jnc.13204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Butterworth R.F. Pathophysiology of brain dysfunction in hyperammonemic syndromes: the many faces of glutamine. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2014;113:113–117. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2014.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Johnson J.W., Ascher P. Glycine potentiates the NMDA response in cultured mouse brain neurons. Nature. 1987;325:529–531. doi: 10.1038/325529a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kleckner N.W., Dingledine R. Requirement for glycine in activation of NMDA-receptors expressed in Xenopus oocytes. Science. 1988;241:835–837. doi: 10.1126/science.2841759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Papouin T., Ladepeche L., Ruel J., Sacchi S., Labasque M., Hanini M., Groc L., Pollegioni L., Mothet J.P., Oliet S.H. Synaptic and extrasynaptic NMDA receptors are gated by different endogenous coagonists. Cell. 2012;150:633–646. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Garcia-Garcia I., Horstmann A., Jurado M.A., Garolera M., Chaudhry S.J., Margulies D.S., Villringer A., Neumann J. Reward processing in obesity, substance addiction and non-substance addiction. Obes. Rev. 2014;15:853–869. doi: 10.1111/obr.12221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yasutake K., Kohjima M., Kotoh K., Nakashima M., Nakamuta M., Enjoji M. Dietary habits and behaviors associated with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014;20:1756–1767. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i7.1756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vilar-Gomez E., Martinez-Perez Y., Calzadilla-Bertot L., Torres-Gonzalez A., Gra-Oramas B., Gonzalez-Fabian L., Friedman S.L., Diago M., Romero-Gomez M. Weight loss through lifestyle modification significantly reduces features of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:367–378.e365. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.04.005. (quiz e314–365) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fabbrini E., Tiemann Luecking C., Love-Gregory L., Okunade A.L., Yoshino M., Fraterrigo G., Patterson B.W., Klein S. Physiological mechanisms of weight-gain induced steatosis in people with obesity. Gastroenterology. 2015 doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Erbas O., Sarac F., Aktug H., Peker G. Detection of impaired cognitive function in rat with hepatosteatosis model and improving effect of GLP-1 analogs (exenatide) on cognitive function in hepatosteatosis. ScientificWorldJournal. 2014;2014:946265. doi: 10.1155/2014/946265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Newton J.L., Hollingsworth K.G., Taylor R., El-Sharkawy A.M., Khan Z.U., Pearce R., Sutcliffe K., Okonkwo O., Davidson A., Burt J., Blamire A.M., Jones D. Cognitive impairment in primary biliary cirrhosis: symptom impact and potential etiology. Hepatology. 2008;48:541–549. doi: 10.1002/hep.22371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Transparency document.