Abstract

Background

Varenicline is an efficacious smoking‐cessation drug. However, previous meta‐analyses provide conflicting results regarding its cardiovascular safety. The publication of several new randomized controlled trials (RCTs) provides an opportunity to reassess this potential adverse drug reaction.

Methods and Results

We searched MEDLINE, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Library for RCTs that compare varenicline with placebo for smoking cessation. RCTs reporting cardiovascular serious adverse events and/or all‐cause mortality during the treatment period or within 30 days of treatment discontinuation were eligible for inclusion. Relative risks (RRs) with 95% CIs were generated by using DerSimonian–Laird random‐effects models. Thirty‐eight RCTs met our inclusion criteria (N=12 706). Events were rare in both varenicline (57/7213) and placebo (43/5493) arms. No difference was observed for cardiovascular serious adverse events when comparing varenicline with placebo (RR 1.03, 95% CI 0.72–1.49). Similar findings were obtained when examining cardiovascular (RR 1.04, 95% CI 0.57–1.89) and noncardiovascular patients (RR 1.03, 95% CI 0.64–1.64). Deaths were rare in both varenicline (11/7213) and placebo (9/5493) arms. Although 95% CIs were wide, pooling of all‐cause mortality found no difference between groups (RR 0.88, 95% CI 0.50–1.52), including when stratified by participants with (RR 1.24, 95% CI 0.40–3.83) and without (RR 0.77, 95% CI 0.40–1.48) cardiovascular disease.

Conclusions

We found no evidence that varenicline increases the rate of cardiovascular serious adverse events. Results were similar among those with and without cardiovascular disease. Given varenicline's efficacy as a smoking cessation drug and the long‐term cardiovascular benefits of cessation, it should continue to be prescribed for smoking cessation.

Keywords: cardiovascular disease, meta‐analysis, smoking cessation, systematic review, varenicline

Subject Categories: Cardiovascular Disease, Secondary Prevention

Introduction

Varenicline is a partial nicotine receptor agonist that has been shown to be an efficacious smoking‐cessation pharmacotherapy.1, 2 However, concerns exist regarding the cardiovascular safety of varenicline. Previous meta‐analyses provided conflicting results regarding the association between varenicline and adverse cardiovascular events.3, 4, 5, 6 In addition, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has issued a warning regarding serious cardiovascular events that may occur in patients taking the drug.7 Conclusive findings have been difficult to obtain given the rarity of these events and the limited size and duration of trials examining its use. However, safety data from more than a dozen new randomized controlled trials (RCTs) examining the use of varenicline for smoking cessation have nearly doubled the number of events of interest available, providing an opportunity to reassess this safety concern. We therefore performed a systematic review and meta‐analysis of RCTs to examine the cardiovascular safety of varenicline.

Methods

Search Strategy

This systematic review and meta‐analysis was performed using a prespecified protocol, and the results are reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses guidelines.8 A detailed description of the search strategy can be found in Tables S1 through S3. Briefly, we systematically searched MEDLINE (via Ovid), EMBASE (via Ovid), and the Cochrane Library in June 2015 by using Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and EMTREE terms as well as keywords for varenicline. These search terms were then combined with a modified version of the Cochrane Collaboration's RCT hedge to restrict our search to RCTs.9 The search was not restricted by date or language of publication. In addition, the references of included studies, as well as previous meta‐analyses, were hand‐searched for other potentially relevant studies. Unpublished data from a trial conducted by the authors (NCT00794573) were also screened for inclusion; this trial was published during the conduct of this meta‐analysis.10

Study Selection

One reviewer (L.H.S.) screened the titles and abstracts of publications identified by the search. The full texts of potentially eligible articles were then screened, and those meeting our prespecified inclusion/exclusion criteria were included. Two reviewers (L.H.S. and L.T.) independently performed the full‐text review, with disagreements resolved by consensus or a third reviewer (S.B.W.). Articles eligible for inclusion were those that (1) contained original data from RCTs examining the use of varenicline versus an inactive control (ie, placebo or a behavioral intervention applied equally in the varenicline and comparison groups; hereinafter referred to as placebo) in tobacco users and (2) reported the incidence of cardiovascular serious adverse events (SAEs) and/or all‐cause mortality during the study treatment period (ie, the duration of use of varenicline or placebo) or up to 30 days after drug discontinuation. Studies combining the use of the study drug with any form of behavioral counseling were also included. Observational studies, studies of abstinence maintenance, case reports and case series, reviews, meta‐analyses, commentaries, letters to the editor, conference proceedings, and abstracts were excluded. Articles published in a language other than English or French were also excluded.

Data Abstraction

Two reviewers (L.H.S. and L.T.) independently abstracted data, with discrepancies resolved by consensus or a third reviewer (S.B.W.). Abstracted information included trial name, first author, year published, countries in which participants were enrolled, sample size, length of treatment, varenicline dose, cardiovascular inclusion or exclusion criteria (eg, clinically significant cardiovascular disease [CVD], neurologic disorders, or cerebrovascular disease during the previous 6 months), participant demographic information (ie, age, sex, mean number of years smoked, and mean number of cigarettes smoked per day at baseline), and data pertaining to safety outcomes.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was incidence of cardiovascular SAEs (eg, myocardial infarction, unstable angina, coronary artery disease, need for coronary revascularization, arrhythmia, congestive heart failure, transient ischemic attack, stroke, sudden death, cardiovascular‐related death). The secondary outcome was all‐cause mortality. Only events that occurred during study treatment or within 30 days of drug discontinuation were included. Whenever possible, published outcome data were compared with results posted on ClinicalTrials.gov. When event rates differed for a given trial, we chose the source providing the most detailed classification of events (eg, in terms of determining whether reported SAEs were cardiovascular in nature and/or clarifying the timing of reported events in relation to study drug use).

Quality Assessment

Quality assessment of each included trial was performed by using the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool.11 This tool is used to assess threats to internal validity by assigning scores of “high,” “low,” or “unclear” risk of bias in the domains of sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants, personnel and outcome assessors, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting, and other potential sources of bias. Two reviewers (L.H.S. and L.T.) independently performed quality assessment, and discrepancies were resolved by consensus or a third reviewer (S.B.W.). All studies were included in the review and meta‐analysis regardless of their quality.

Statistical Analysis

We used DerSimonian–Laird random‐effects models to calculate relative risks (RRs) and corresponding 95% CIs. All analyses were conducted overall and then stratified by whether the trial was conducted in participants with a history of CVD. In our primary analysis, we used a 0.5 continuity correction to include data from RCTs that had study arms with zero events. This continuity correction allows for inclusion of zero event trials while maintaining analytic consistency.12 Risk differences (RDs) with 95% CIs were also calculated; these analyses were stratified by treatment duration and CVD history. Heterogeneity was assessed by using an I 2 statistic.

Several sensitivity analyses were conducted to assess the robustness of our results. First, we repeated our analyses by using Mantel–Haenszel fixed‐effects models. Inverse‐variance weighting and the Peto approach were used to assess the impact of the choice of fixed‐effects approach, given the small number of events in the individual trials. Second, we conducted influence analyses in which our random‐effects analyses were repeated omitting 1 trial at a time to assess the impact of each individual RCT on the final pooled results. Third, we repeated our analyses excluding trials with zero events in one arm and then excluding trials with zero events in both arms to assess the impact of zero event trials on our results. Fourth, we repeated our primary analyses, including only trials with at least 100 participants. Finally, to assess for potential publication bias, a funnel plot was visually assessed, and an Egger's test for small study effects was performed. All analyses were performed by using R version 3.2.2. [R Core Team (2015), R Foundation for Statistical Computing].

Results

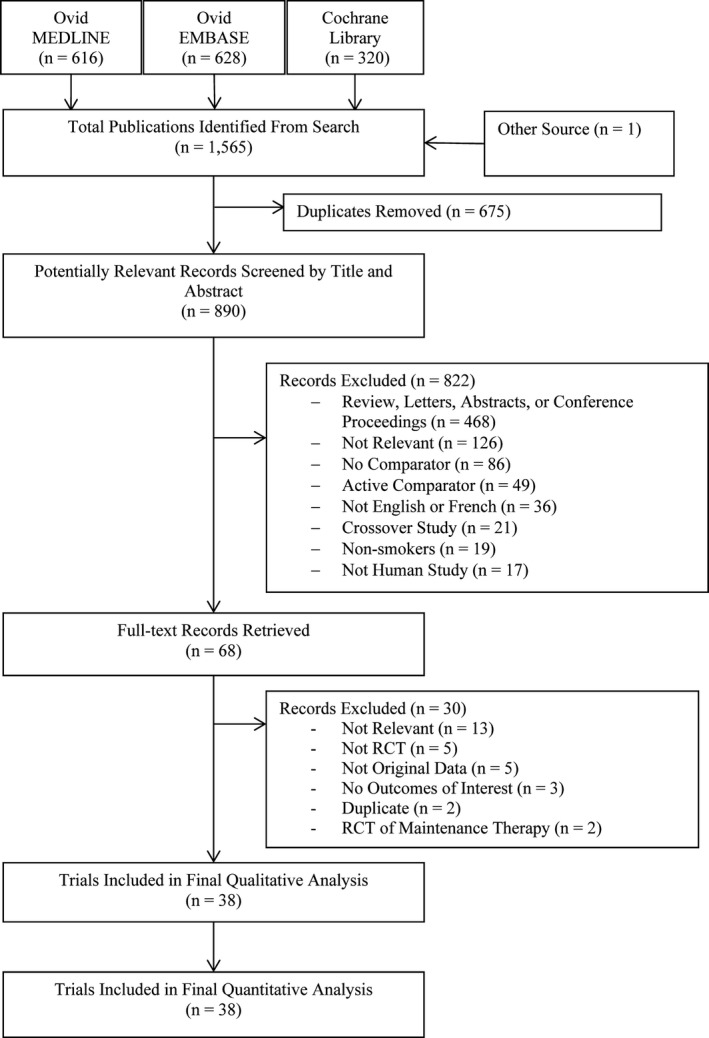

Our electronic database search yielded 1564 potentially eligible studies for inclusion in our review (Figure 1). We additionally assessed unpublished data from a trial conducted by the authors (NCT00794573); this trial was published during the conduct of this meta‐analysis.10 After the removal of duplicates and screening of titles and abstracts, 68 trials underwent full‐text review. In total, 38 RCTs met all eligibility criteria and were included in our meta‐analysis.10, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart describing the study's systematic literature search and study selection.

Study Characteristics

Sample sizes ranged from 10 to 1510 patients with a median of 268 patients (Table). A total of 7213 patients were randomized to varenicline and 5493 patients to placebo. The most common dose of varenicline was 1 mg twice daily, with some studies in which lower doses were prescribed. Length of treatment with varenicline ranged from 1 to 52 weeks, with the majority of studies treating patients for 12 weeks. Four studies examined CVD patients specifically (1 studied patients with a recent acute coronary syndrome, 1 studied patients with stable coronary artery disease, and 2 studied inpatients in which >50% were admitted for CVD). Seventeen RCTs examined smokers drawn from the general population, 5 studied smokers with mental illness (ie, schizophrenia, depression, bipolar disorder), 3 studied opioid‐ or cocaine‐dependent tobacco smokers, 4 studied smokeless tobacco users, and 5 RCTs examined patients with other inclusion criteria such as specific age ranges or patients scheduled for surgery. Losses to follow‐up varied between studies and ranged between 0% to 60%, with most studies reporting losses of <25%.

Table 1.

Trial Characteristics of RCTs Comparing Varenicline With Placebo and Smoking Profiles of Patients

| Study Lead Author, Year | No. of Patients | Varenicline Dose | Treatment (wk) | Years Smoked | Cigarettes, No./d | Patient Population | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Varenicline | Placebo | Varenicline | Placebo | Varenicline | Placebo | ||||

| Cardiovascular patients | |||||||||

| Rigotti, 201013 | 355 | 359 | 1 mg BID | 12 | 40.0 | 39.0 | 22.1 | 22.0 | Smokers with stable CVD |

| Carson, 201414 | 196 | 196 | 1 mg BID | 12 | 37.1±2.9 | 37.7±2.9 | 24.9±2.7 | 24.7±2.9 | Inpatients with tobacco‐related illness |

| Eisenberg, 201610 | 151 | 151 | 1 mg BID | 12 | 35.1±11.4 | 36.7±11.8 | 21.9±10.9 | 21.0±10.3 | Inpatients with ACS |

| Steinberg, 201115 | 40 | 39 | 1 mg BID | 12 | NR | NR | NR | NR | Inpatient smokers |

| General population | |||||||||

| Ebbert, 201516 | 760 | 750 | 1 mg BID | 24 | NR | NR | 20.6±8.5 | 20.8±8.2 | Adult smokers |

| Gonzales, 200617 | 352 | 344 | 1 mg BID | 12 | 24.3±11.5 | 24.7±12.1 | 21.1±9.5 | 21.5±9.5 | Adult smokers |

| Jorenby, 200618 | 344 | 341 | 1 mg BID | 12 | 27.1±11.5 | 24.4±11.6 | 22.5±9.5 | 21.5±8.7 | Adult smokers |

| Rennard, 201219 | 493 | 166 | 1 mg BID | 12 | 26.0 | 24.6 | 21.3 | 21.5 | Adult smokers |

| Oncken, 200620 | 124 | 121 | 0.5 mg BID untitrated | 12 | 26.0±10.8 | 25.3±9.5 | 20.9±8.2 | 20.4±7.2 | Adult smokers |

| 129 | 0.5 mg BID | 25.0±10.8 | 21.3±8.1 | ||||||

| 124 | 1 mg BID untitrated | 25.7±10.6 | 20.8±20.2 | ||||||

| 129 | 1 mg BID | 24.0±11.1 | 20.9±7.0 | ||||||

| Bolliger, 201121 | 394 | 199 | 1 mg BID | 12 | 25.0 | 26.8 | 23.8 | 23.7 | Adult smokers |

| Nakamura, 200722 | 128 | 129 | 0.25 mg BID | 12 | 20.9±11.5 | 20.9±11.4 | 24.9±10.3 | 23.1±8.8 | Adult smokers |

| 129 | 0.5 mg BID | 20.1±11.3 | 23.8±10.5 | ||||||

| 130 | 1 mg BID | 21.5±11.3 | 24.0±9.8 | ||||||

| Nides, 200623 | 126 | 123 | 0.3 mg QD | 6 | 24.6±10.9 | 23.9±10.6 | 20.3±7.7 | 21.5±8.0 | Adult smokers |

| 126 | 1 mg QD | 25.4±11.1 | 20.1±7.8 | ||||||

| 125 | 1 mg BID | 23.4±10.0 | 18.9±6.9 | ||||||

| Gonzales, 201424 | 251 | 247 | 1 mg BID | 12 | 30.2±12.1 | 30.0±11.7 | 19.9±7.2 | 21.4±7.7 | Smokers who previously used varenicline |

| Williams, 200725 | 251 | 126 | 1 mg BID | 52 | 30.7 | 29.9 | 23.2 | 23.4 | Adult smokers |

| Wang, 200926 | 165 | 168 | 1 mg BID | 12 | 20.5 | 19.6 | 20.3 | 21.3 | Adult smokers |

| Niaura, 200827 | 160 | 160 | 1 mg BID | 12 | 24.9 | 25.7 | 22.2 | 22.3 | Adult smokers |

| Tsai, 200728 | 126 | 124 | 1 mg BID | 12 | 20.2 | 22.1 | 23.4 | 22.7 | Adult smokers |

| Hughes, 201129 | 52 | 58 | 1 mg BID, NE Site | 2 to 8 | NR | NR | 19.0±9.0 | 17.0±7.0 | Adult smokers |

| 55 | 53 | 1 mg BID VE Site | NR | NR | 20.0±10.0 | 18.0±6.0 | |||

| Cinciripini, 201330 | 86 | 106 | 1 mg BID | 12 | NR | NR | 19.2±8.5 | 19.7±9.8 | Adult smokers |

| Heydari, 201231 | 89 | 91 | 1 mg BID | 12 | NR | NR | NR | NR | Adult smokers |

| Garza, 201132 | 55 | 55 | 1 mg BID | 12 | 16.9 | 16.8 | 23.3 | 21.3 | Adult smokers |

| Patients with mental illness | |||||||||

| Anthenelli, 201333 | 256 | 269 | 1 mg BID | 12 | 26.0±11.7 | 27.3±11.8 | 21.9±7.5 | 21.5±8.7 | Adult smokers with major depressive disorder |

| Williams, 201234 | 85 | 43 | 1 mg BID | 12 | 23.7 | 24.9 | 23.5 | 22.3 | Adult smokers with schizophrenia |

| Chengappa, 201435 | 31 | 29 | 1 mg BID | 12 | 29.4±11.5 | 29.0±10.9 | 18.1±6.2 | 18.2±8.3 | Adult smokers with bipolar disorder |

| Hong, 201136 | 20 | 23 | 0.5 mg BID | 8 | NR | NR | NR | NR | Adult smokers with schizophrenia |

| Meszaros, 201237 | 5 | 5 | 1 mg BID | 8 | NR | NR | 15.0±15.0 | 14.3±14.7 | Smokers with schizophrenia and alcohol dependence |

| Smokeless tobacco users | |||||||||

| Fagerstrom, 201038 | 214 | 218 | 1 mg BID | 12 | 20.3±11.0 | 21.7±11.8 | 15.4±5.8a | 15.9±7.7a | Smokeless tobacco users |

| Jain, 201439 | 119 | 118 | 1 mg BID | 12 | 10.9±7.6 | 11.4±7.6 | 13.0±8.8b | 12.3±6.7b | Smokeless tobacco users |

| Tonnesen, 201340 | 70 | 69 | 1 mg BID | 12 | 5.6±3.7c | 7.0±5.1c | 22.4±8.9d | 24.5±9.9d | Long‐term NRT users |

| Ebbert, 201141 | 38 | 38 | 1 mg BID | 12 | 19.1±12.2 | 18.5±10.4 | 4.0±3.5e | 3.2±2.0e | Smokeless tobacco users |

| Smokers dependent on opioids or cocaine | |||||||||

| Stein, 201342 | 137 | 45 | 1 mg BID | 24 | 22.8±10.1 | 23.0±11.3 | 19.5±8.5 | 21.2±10.4 | Methadone‐maintained smokers |

| Nahvi, 201443 | 57 | 55 | 1 mg BID | 12 | NR | NR | 15 (10–20) | 15 (10–20) | Methadone‐maintained smokers |

| Poling, 201044 | 13 | 18 | 1 mg BID | 12 | NR | NR | 18.2 | 19.1 | Methadone‐maintained smokers who use cocaine |

| Other | |||||||||

| Tashkin, 201145 | 250 | 254 | 1 mg BID | 12 | 40.04 | 40.6 | 25.3 | 23.6 | Adult smokers with COPD |

| Wong, 201246 | 151 | 135 | 1 mg BID | 12 | NR | NR | 17.8±8.2 | 17.0±7.5 | Smokers scheduled for surgery |

| Faessel, 200947 | 14 | 7 | 1 mg BID, >55 kg | 2 | 2.3 | 1.9 | 12.0 | 13.0 | Adolescent smokers (aged 12–16 y) |

| 14 | 0.5 mg BID, >55 kg | 2.5 | 11.0 | ||||||

| 14 | 8 | 0.5 mg BID, <55 kg | 1.8 | 1.8 | 7.0 | 6.0 | |||

| 15 | 0.5 mg QD, <55 kg | 2.1 | 9.0 | ||||||

| Mitchell, 201248 | 31 | 33 | 1 mg BID | 12 | NR | NR | 10.7f | 11.0f | Heavy drinking adult smokersg |

| Burstein, 200649 | 8 | 8 | 1 mg QD | 1 | 51.5±5.0 | 40.9±14.0 | 26.0±11.0 | 21.3±10.0 | Smokers >65 years old |

| 8 | 1 mg BID | 50.4±6.0 | 20.8±10.0 | ||||||

ACS indicates acute coronary syndromes; BID, twice daily; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CVD, cardiovascular disease; LTFU, lost to follow‐up; NR, not reported; NRT, nicotine replacement therapy; QD, once daily.

Portions used per day.

Average number of times smokeless tobacco was used per day.

Duration of Nicotine Replacement Therapy use.

Average number of cigarettes smoked per day when last smoked.

Cans or pouches of smokeless tobacco used per week.

Mean number of cigarettes smoked per week divided by 7.

≥7 drinks/week for women or ≥14 drinks/week in men.

Quality Assessment

Overall, studies had a low risk of bias (Table S4) when assessed by using the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool.11 A number of studies had an unclear risk of bias in the sequence generation and allocation concealment categories. In the blinding domain, 1 study had a high risk of bias as a result of a behavioral intervention–only comparison group. Two additional studies had an unclear risk of bias because of insufficient information to determine whether there was adequate blinding. Several studies had an unclear or high risk of bias in the category of outcome data because of high rates of loss to follow‐up.

Patient Characteristics

The mean age of participants across all study arms ranged from 13.5 to 69.1 years, and the proportion of male participants ranged from 26.7% to 97.5% (Table S5). Among studies conducted in adult tobacco users, the mean number of years of use ranged from 10.9 to 51.5 years (Table). In trials conducted in cigarette‐smoking adults, the mean number of cigarettes smoked per day ranged from 10.7 to 26.0 (Table).

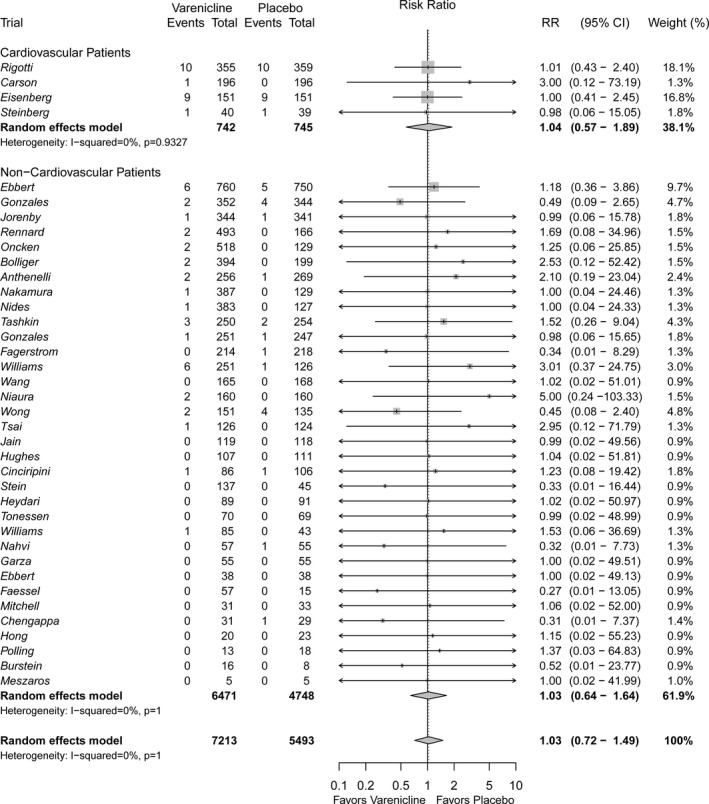

Cardiovascular SAEs

Overall, event rates were low, with 14 of the 38 included studies reporting no cardiovascular SAEs during treatment or within 30 days of treatment discontinuation. As anticipated, RCTs conducted in patients with acute coronary syndromes or established stable CVD had a higher cumulative incidence of cardiovascular SAEs than did trials conducted in other populations. A total of 57 cardiovascular SAEs occurred in the 7213 patients randomized to varenicline, and 43 occurred in the 5493 patients randomized to placebo (Figure 2). When pooling the data across the 38 studies by using a random‐effects model, no significant difference was found for cardiovascular SAEs when comparing varenicline with placebo (RR 1.03, 95% CI 0.72–1.49). Similar results were found among patients with a history of CVD (RR 1.04, 95% CI 0.57–1.89) and without a history of CVD (RR 1.03, 95% CI 0.64–1.64). The corresponding RDs were 0.00 (95% CI 0.01–0.02) and 0.00 (95% CI 0.00–0.00), respectively (Figures S1 and S2).

Figure 2.

Forest plot of the relative risks of cardiovascular serious adverse events in patients randomized to varenicline versus placebo.

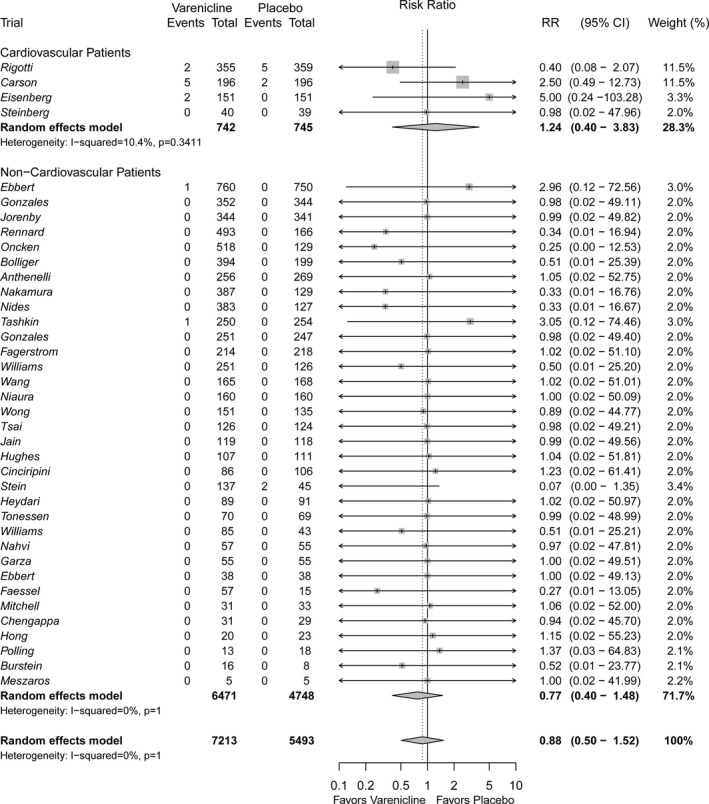

All‐Cause Mortality

Very few deaths occurred, with 32 of the 38 of studies reporting zero events in both study arms. The cause of death was reported for only half of the deaths that occurred, and half of these were cardiovascular in nature (n=5) (Table S6). A total of 11 deaths occurred in the 7213 patients randomized to varenicline and 9 occurred in the 5493 patients randomized to placebo (Figure 3). When data were pooled across trials, no difference in all‐cause mortality was observed when comparing varenicline with placebo (RR 0.88, 95% CI 0.50–1.52). There was no detectable difference between patients with a history of CVD (RR 1.24, 95% CI 0.40–3.83) and those without a history of CVD (RR 0.77, 95% CI 0.40–1.48); however, CIs were wide because of the rarity of these events. Corresponding RDs were also calculated, with no detectable difference found between varenicline and placebo for all‐cause mortality in both CVD (RD 0.00, 95% CI −0.01 to 0.01) and non‐CVD patients (RD 0.00, 95% CI 0.00–0.00) (Figures S3 and S4).

Figure 3.

Forest plot of the relative risks of all‐cause mortality in patients randomized to varenicline versus placebo.

Sensitivity Analyses

Sensitivity analyses that used fixed‐effects models produced results that were consistent with those of our primary analyses (data not shown). An influence analysis performed by using random‐effects models showed that no study had an overly large impact on the meta‐analysis results (data not shown). Results also remained consistent when repeating our primary analyses while excluding trials with zero events in one arm and then excluding trials with zero events in both arms (data not shown). When including only studies with >100 participants, results were consistent with those of our primary analysis (data not shown). Importantly, these analyses excluded the trial by Faessel et al, which was conducted in adolescents. Finally, visual inspection of a funnel plot (Figure S5) and Egger's test (P=0.80) showed no evidence of publication bias.

Discussion

Our study was designed to assess the cardiovascular safety of varenicline compared with placebo. Overall, cardiovascular SAEs and deaths were rare across trials. We found no increased risk of cardiovascular SAEs in participants randomized to varenicline. These findings were similar when stratified by participants with or without a history of CVD. Likewise, all‐cause mortality appeared similar between study populations and arms; however, the CIs were wide as a result of the rarity of these events and the relatively short treatment durations of included trials. Our results suggest that varenicline is not associated with increased cardiovascular risks compared with placebo.

Concerns regarding the cardiovascular safety of varenicline first emerged after an RCT that examined the use of varenicline in patients with stable CVD. The authors found numerically greater cardiovascular SAEs in the varenicline arm compared with the placebo arm when including events that occurred >30 days post treatment discontinuation.13 Shortly after, the first of several meta‐analyses examining the cardiovascular safety of varenicline was published. In their meta‐analysis, Singh et al reported an increased incidence of cardiovascular SAEs when comparing varenicline with placebo.3 However, the Singh et al meta‐analysis was criticized for its choice of statistical approach, exclusion of zero event trials, and inclusion of events that occurred >30 days after drug discontinuation.4, 50, 51 This may have resulted in an overestimation of the cardiovascular risk of varenicline.

A subsequent meta‐analysis performed by Prochaska and Hilton, which included only events that occurred during or within 30 days of treatment with the study drug, found no difference in cardiovascular SAE incidence between varenicline and placebo groups despite the use of a variety of meta‐analytic techniques.4 A US Food and Drug Administration–mandated meta‐analysis published by Ware et al that examined Pfizer‐sponsored studies had similar findings.5 This patient‐level meta‐analysis found no significant difference in rates of cardiovascular SAEs and low absolute risk of cardiovascular SAEs with the use of varenicline. Finally, a network meta‐analysis conducted by Mills et al also found no evidence of cardiovascular harm with varenicline.6 Our meta‐analysis incorporated safety data from 16 new trials (including 1 conducted in the highest‐risk patient population studied to date), nearly doubling the number of events available to pool. Our findings likewise suggest that these events are rare and not likely to be increased by the use of varenicline. These findings are also consistent with the results of several large cohort studies, which found no increased risk of cardiovascular SAEs when comparing individuals using varenicline with those using bupropion for smoking cessation.52, 53 Ultimately, there is little epidemiological evidence to suggest that varenicline increases the risk of cardiovascular SAEs.

Likewise, the biological mechanism by which varenicline could mediate cardiovascular SAEs remains unclear. Varenicline is a partial agonist of the α4‐β2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAchR) and a full agonist of the α3‐β4 and α7 nAchRs. These receptors have been shown to potentially modulate cardiovascular function.11, 54, 55, 56 Varenicline activates α4‐β2 and α7 nAchRs at rates similar to those of nicotine and is a greater agonist than nicotine at the α3‐β4 nAchR.57 However, it is unknown whether partial activation of these receptors can lead to major changes in cardiovascular health, as the role of these receptors in modulating the cardiovascular system is not well studied. It should be noted, however, that only a small portion of the detrimental effects of smoking could be expected to be mediated through nAchRs. The hemodynamic effects of nicotine arise mostly through activation of β‐adrenergic receptors and not nAchRs,58 and the vast majority of cardiovascular damage from smoking occurs as a result of the inflammation, oxidative stress, and hypercoagulable state caused by reactive oxygen species, carbon monoxide, and various particulates in tobacco smoke itself, not nicotine.59 Given this, it appears unlikely that varenicline would increase cardiovascular risk through its activation of nAchRs, and if possible, the occurrence of such events would be extremely rare. This potential risk must also be considered in the context of the exceptional role of quitting smoking in reducing cardiovascular risk.59, 60 The cardiovascular benefits of varenicline as an efficacious smoking‐cessation pharmacotherapy61 far outweigh a speculative and extremely small potential increase in cardiovascular risk.

Our review had several potential limitations. First, the events of interest were rare; therefore, despite pooling all available data, some treatment effects are accompanied by wider 95% CIs. Second, the analysis of secondary data includes reliance on individual study definitions of events to be counted as cardiovascular SAEs, and few studies reported independent adjudication of these events. Third, the potential for publication bias cannot be excluded; however, we found no evidence of this bias through Egger's test or visual examination of a funnel plot. Finally, one included study was unblinded. However, this study accounts for only 1.32% of the weight in our primary analysis of cardiovascular SAEs. Consequently, its inclusion is unlikely to have had an important impact on our overall treatment estimates.

Conclusion

This study was designed to assess the cardiovascular safety of varenicline compared with placebo. When pooling data from 38 RCTs, we found no evidence of an increased risk of cardiovascular SAEs or all‐cause mortality with varenicline. Results were similar among studies that included participants with and without a history of CVD. The benefits of varenicline as an efficacious smoking‐cessation therapy outweigh any potential increased risk of cardiovascular harm.

Sources of Funding

Mr Sterling is supported by a Ron and Marcy Prussick Research Bursary and Mr Touma is supported by a Mach‐Gaensslen Foundation of Canada Student Grant, both funded through the McGill University Research Bursary Program. Dr Filion holds a Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) New Investigator Award.

Disclosures

Dr Eisenberg is the principal investigator of The Evaluation of Varenicline in Smoking Cessation for Patients Post‐Acute Coronary Syndrome (EVITA) Trial (NCT00794573), an investigator‐initiated trial, which received funding and study drug/placebo from Pfizer Inc. Pfizer Inc had no role in the design, conduct, analysis, interpretation of data, or reporting of the EVITA trial. Dr Eisenberg also received honoraria from Pfizer Inc for providing continuing medical education on smoking cessation. The other authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Supporting information

Table S1. Description of the MEDLINE Search for Randomized Controlled Trials Examining Varenicline Versus Placebo*

Table S2. Description of the EMBASE Search for Randomized Controlled Trials Examining Varenicline Versus Placebo*

Table S3. Description of the Cochrane Library Search for Randomized Controlled Trials Examining Varenicline Versus Placebo*

Table S4. Quality Assessment of Included Trials

Table S5. Patient Characteristics and Cardiovascular Exclusion Criteria

Table S6. Causes of Death in Included Randomized Controlled Trials

Figure S1. Forest plot of the risk differences of cardiovascular serious adverse events in patients randomized to varenicline versus placebo in studies examining patients with cardiovascular disease.

Figure S2. Forest plot of the risk differences of cardiovascular serious adverse events in patients randomized to varenicline versus placebo in studies examining patients without cardiovascular disease.

Figure S3. Forest plot of the risk differences of all‐cause mortality in patients randomized to varenicline versus placebo in studies examining patients with cardiovascular disease.

Figure S4. Forest plot of the risk differences of all‐cause mortality in patients randomized to varenicline versus placebo in studies examining patients without cardiovascular disease.

Figure S5. Funnel plot of included studies.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ms Renee Atallah, MSc, for her editorial assistance and Ms Pauline Reynier, MSc, for her programming support.

(J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5:e002849 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.115.002849)

Accompanying Tables S1 through S6 and Figures S1 through S5 are available at http://jaha.ahajournals.org/content/5/2/e002849/suppl/DC1

References

- 1. Eisenberg MJ, Filion KB, Yavin D, Belisle P, Mottillo S, Joseph L, Gervais A, O'Loughlin J, Paradis G, Rinfret S, Pilote L. Pharmacotherapies for smoking cessation: a meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials. CMAJ. 2008;179:135–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Foulds J. The neurobiological basis for partial agonist treatment of nicotine dependence: varenicline. Int J Clin Pract. 2006;60:571–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Singh S, Loke YK, Spangler JG, Furberg CD. Risk of serious adverse cardiovascular events associated with varenicline: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. CMAJ. 2011;183:1359–1366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Prochaska JJ, Hilton JF. Risk of cardiovascular serious adverse events associated with varenicline use for tobacco cessation: systematic review and meta‐analysis. BMJ. 2012;344:e2856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ware JH, Vetrovec GW, Miller AB, Van Tosh A, Gaffney M, Yunis C, Arteaga C, Borer JS. Cardiovascular safety of varenicline: patient‐level meta‐analysis of randomized, blinded, placebo‐controlled trials. Am J Ther. 2013;20:235–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mills EJ, Thorlund K, Eapen S, Wu P, Prochaska JJ. Cardiovascular events associated with smoking cessation pharmacotherapies: a network meta‐analysis. Circulation. 2014;129:28–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chelladurai Y, Singh S. Varenicline and cardiovascular adverse events: a perspective review. Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2014;5:167–172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gotzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, Clarke M, Devereaux PJ, Kleijnen J, Moher D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta‐analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:e1–e34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lefebvre C, Manheimer E, Glanville J. Chapter 6: searching for studies In: Higgins JPT, Green S, eds. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 (updated March 2011). The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011. Available at: www.cochrane-handbook.org. Accessed September 7, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Eisenberg MJ, Windle SB, Roy N, Old W, Grondin FR, Bata I, Iskander A, Lauzon C, Srivastava N, Clarke A, Cassavar D, Dion D, Haught H, Mehta SR, Baril JF, Lambert C, Madan M, Abramson BL, Dehghani P; EVITA Investigators . Varenicline for smoking cessation in hospitalized patients with acute coronary syndrome. Circulation. 2016;133:21–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC, Juni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, Savovic J, Schulz KF, Weeks L, Sterne JA. The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Friedrich JO, Adhikari NK, Beyene J. Inclusion of zero total event trials in meta‐analyses maintains analytic consistency and incorporates all available data. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2007;7:5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rigotti NA, Pipe AL, Benowitz NL, Arteaga C, Garza D, Tonstad S. Efficacy and safety of varenicline for smoking cessation in patients with cardiovascular disease: a randomized trial. Circulation. 2010;121:221–229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Carson KV, Smith BJ, Brinn MP, Peters MJ, Fitridge R, Koblar SA, Jannes J, Singh K, Veale AJ, Goldsworthy S, Litt J, Edwards D, Hnin KM, Esterman AJ. Safety of varenicline tartrate and counseling versus counseling alone for smoking cessation: a randomized controlled trial for inpatients (STOP study). Nicotine Tob Res. 2014;16:1495–1502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Steinberg MB, Randall J, Greenhaus S, Schmelzer AC, Richardson DL, Carson JL. Tobacco dependence treatment for hospitalized smokers: a randomized, controlled, pilot trial using varenicline. Addict Behav. 2011;36:1127–1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ebbert JO, Hughes JR, West RJ, Rennard SI, Russ C, McRae TD, Treadow J, Yu CR, Dutro MP, Park PW. Effect of varenicline on smoking cessation through smoking reduction: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;313:687–694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gonzales D, Rennard SI, Nides M, Oncken C, Azoulay S, Billing CB, Watsky EJ, Gong J, Williams KE, Reeves KR; Varenicline Phase 3 Study Group . Varenicline, an alpha4beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist, vs sustained‐release bupropion and placebo for smoking cessation: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;296:47–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jorenby DE, Hays JT, Rigotti NA, Azoulay S, Watsky EJ, Williams KE, Billing CB, Gong J, Reeves KR; Varenicline Phase 3 Study Group . Efficacy of varenicline, an alpha4beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist, vs placebo or sustained‐release bupropion for smoking cessation: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;296:56–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rennard S, Hughes J, Cinciripini PM, Kralikova E, Raupach T, Arteaga C, St Aubin LB, Russ C; Flexible Quit Date Study Group . A randomized placebo‐controlled trial of varenicline for smoking cessation allowing flexible quit dates. Nicotine Tob Res. 2012;14:343–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Oncken C, Gonzales D, Nides M, Rennard S, Watsky E, Billing CB, Anziano R, Reeves K. Efficacy and safety of the novel selective nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist, varenicline, for smoking cessation. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1571–1577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bolliger CT, Issa JS, Posadas‐Valay R, Safwat T, Abreu P, Correia EA, Park PW, Chopra P. Effects of varenicline in adult smokers: a multinational, 24‐week, randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled study. Clin Ther. 2011;33:465–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nakamura M, Oshima A, Fujimoto Y, Maruyama N, Ishibashi T, Reeves KR. Efficacy and tolerability of varenicline, an alpha4beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist, in a 12‐week, randomized, placebo‐controlled, dose‐response study with 40‐week follow‐up for smoking cessation in Japanese smokers. Clin Ther. 2007;29:1040–1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nides M, Oncken C, Gonzales D, Rennard S, Watsky EJ, Anziano R, Reeves KR. Smoking cessation with varenicline, a selective alpha4beta2 nicotinic receptor partial agonist: results from a 7‐week, randomized, placebo‐ and bupropion‐controlled trial with 1‐year follow‐up. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1561–1568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gonzales D, Hajek P, Pliamm L, Nackaerts K, Tseng LJ, McRae TD, Treadow J. Retreatment with varenicline for smoking cessation in smokers who have previously taken varenicline: a randomized, placebo‐controlled trial. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2014;96:390–396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Williams KE, Reeves KR, Billing CB Jr, Pennington AM, Gong J. A double‐blind study evaluating the long‐term safety of varenicline for smoking cessation. Curr Med Res Opin. 2007;23:793–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wang C, Xiao D, Chan KP, Pothirat C, Garza D, Davies S. Varenicline for smoking cessation: a placebo‐controlled, randomized study. Respirology. 2009;14:384–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Niaura R, Hays JT, Jorenby DE, Leone FT, Pappas JE, Reeves KR, Williams KE, Billing CB Jr. The efficacy and safety of varenicline for smoking cessation using a flexible dosing strategy in adult smokers: a randomized controlled trial. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24:1931–1941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tsai ST, Cho HJ, Cheng HS, Kim CH, Hsueh KC, Billing CB Jr, Williams KE. A randomized, placebo‐controlled trial of varenicline, a selective alpha4beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist, as a new therapy for smoking cessation in Asian smokers. Clin Ther. 2007;29:1027–1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hughes JR, Rennard SI, Fingar JR, Talbot SK, Callas PW, Fagerstrom KO. Efficacy of varenicline to prompt quit attempts in smokers not currently trying to quit: a randomized placebo‐controlled trial. Nicotine Tob Res. 2011;13:955–964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cinciripini PM, Robinson JD, Karam‐Hage M, Minnix JA, Lam C, Versace F, Brown VL, Engelmann JM, Wetter DW. Effects of varenicline and bupropion sustained‐release use plus intensive smoking cessation counseling on prolonged abstinence from smoking and on depression, negative affect, and other symptoms of nicotine withdrawal. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70:522–533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Heydari G, Talischi F, Tafti SF, Masjedi MR. Quitting smoking with varenicline: parallel, randomised efficacy trial in Iran. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2012;16:268–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Garza D, Murphy M, Tseng LJ, Riordan HJ, Chatterjee A. A double‐blind randomized placebo‐controlled pilot study of neuropsychiatric adverse events in abstinent smokers treated with varenicline or placebo. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;69:1075–1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Anthenelli RM, Morris C, Ramey TS, Dubrava SJ, Tsilkos K, Russ C, Yunis C. Effects of varenicline on smoking cessation in adults with stably treated current or past major depression: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159:390–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Williams JM, Anthenelli RM, Morris CD, Treadow J, Thompson JR, Yunis C, George TP. A randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled study evaluating the safety and efficacy of varenicline for smoking cessation in patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73:654–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chengappa KN, Perkins KA, Brar JS, Schlicht PJ, Turkin SR, Hetrick ML, Levine MD, George TP. Varenicline for smoking cessation in bipolar disorder: a randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75:765–772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hong LE, Thaker GK, McMahon RP, Summerfelt A, Rachbeisel J, Fuller RL, Wonodi I, Buchanan RW, Myers C, Heishman SJ, Yang J, Nye A. Effects of moderate‐dose treatment with varenicline on neurobiological and cognitive biomarkers in smokers and nonsmokers with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68:1195–1206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Meszaros ZS, Abdul‐Malak Y, Dimmock JA, Wang D, Ajagbe TO, Batki SL. Varenicline treatment of concurrent alcohol and nicotine dependence in schizophrenia: a randomized, placebo‐controlled pilot trial. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2013;33:243–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Fagerstrom K, Gilljam H, Metcalfe M, Tonstad S, Messig M. Stopping smokeless tobacco with varenicline: randomised double blind placebo controlled trial. BMJ. 2010;341:c6549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Jain R, Jhanjee S, Jain V, Gupta T, Mittal S, Goelz P, Wileyto EP, Schnoll RA. A double‐blind placebo‐controlled randomized trial of varenicline for smokeless tobacco dependence in India. Nicotine Tob Res. 2014;16:50–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Tonnesen P, Mikkelsen K. Varenicline to stop long‐term nicotine replacement use: a double‐blind, randomized, placebo‐controlled trial. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15:419–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ebbert JO, Croghan IT, Severson HH, Schroeder DR, Hays JT. A pilot study of the efficacy of varenicline for the treatment of smokeless tobacco users in Midwestern United States. Nicotine Tob Res. 2011;13:820–826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Stein MD, Caviness CM, Kurth ME, Audet D, Olson J, Anderson BJ. Varenicline for smoking cessation among methadone‐maintained smokers: a randomized clinical trial. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;133:486–493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Nahvi S, Ning Y, Segal KS, Richter KP, Arnsten JH. Varenicline efficacy and safety among methadone maintained smokers: a randomized placebo‐controlled trial. Addiction. 2014;109:1554–1563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Poling J, Rounsaville B, Gonsai K, Severino K, Sofuoglu M. The safety and efficacy of varenicline in cocaine using smokers maintained on methadone: a pilot study. Am J Addict. 2010;19:401–408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Tashkin DP, Rennard S, Hays JT, Ma W, Lawrence D, Lee TC. Effects of varenicline on smoking cessation in patients with mild to moderate COPD: a randomized controlled trial. Chest. 2011;139:591–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Wong J, Abrishami A, Yang Y, Zaki A, Friedman Z, Selby P, Chapman KR, Chung F. A perioperative smoking cessation intervention with varenicline: a double‐blind, randomized, placebo‐controlled trial. Anesthesiology. 2012;117:755–764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Faessel H, Ravva P, Williams K. Pharmacokinetics, safety, and tolerability of varenicline in healthy adolescent smokers: a multicenter, randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, parallel‐group study. Clin Ther. 2009;31:177–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Mitchell JM, Teague CH, Kayser AS, Bartlett SE, Fields HL. Varenicline decreases alcohol consumption in heavy‐drinking smokers. Psychopharmacology. 2012;223:299–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Burstein AH, Fullerton T, Clark DJ, Faessel HM. Pharmacokinetics, safety, and tolerability after single and multiple oral doses of varenicline in elderly smokers. J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;46:1234–1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Samuels L. Varenicline: cardiovascular safety. CMAJ. 2011;183:1407–1408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Hays JT. Varenicline for smoking cessation: is it a heartbreaker? CMAJ. 2011;183:1346–1347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Toh S, Baker MA, Brown JS, Kornegay C, Platt R. Rapid assessment of cardiovascular risk among users of smoking cessation drugs within the US Food and Drug Administration's Mini‐Sentinel program. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:817–819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Svanstrom H, Pasternak B, Hviid A. Use of varenicline for smoking cessation and risk of serious cardiovascular events: nationwide cohort study. BMJ. 2012;345:e7176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Mazloom R, Eftekhari G, Rahimi M, Khori V, Hajizadeh S, Dehpour AR, Mani AR. The role of alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor in modulation of heart rate dynamics in endotoxemic rats. PLoS One. 2013;8:e82251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Moore C, Wang Y, Ramage AG. Cardiovascular effects of activation of central alpha7 and alpha4beta2 nAChRs: a role for vasopressin in anaesthetized rats. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;153:1728–1738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Jutkiewicz EM, Rice KC, Carroll FI, Woods JH. Patterns of nicotinic receptor antagonism II: cardiovascular effects in rats. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;131:284–297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Rollema H, Russ C, Lee TC, Hurst RS, Bertrand D. Functional interactions of varenicline and nicotine with nAChR subtypes implicated in cardiovascular control. Nicotine Tob Res. 2014;16:733–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Benowitz NL. Cigarette smoking and cardiovascular disease: pathophysiology and implications for treatment. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2003;46:91–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services . How Tobacco Smoking Causes Disease: The Biology and Behavioral Basis for Smoking‐Attributable Disease: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Jha P, Ramasundarahettige C, Landsman V, Rostron B, Thun M, Anderson RN, McAfee T, Peto R. 21st‐century hazards of smoking and benefits of cessation in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:341–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Cahill K, Stevens S, Perera R, Lancaster T. Pharmacological interventions for smoking cessation: an overview and network meta‐analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;5:CD009329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Description of the MEDLINE Search for Randomized Controlled Trials Examining Varenicline Versus Placebo*

Table S2. Description of the EMBASE Search for Randomized Controlled Trials Examining Varenicline Versus Placebo*

Table S3. Description of the Cochrane Library Search for Randomized Controlled Trials Examining Varenicline Versus Placebo*

Table S4. Quality Assessment of Included Trials

Table S5. Patient Characteristics and Cardiovascular Exclusion Criteria

Table S6. Causes of Death in Included Randomized Controlled Trials

Figure S1. Forest plot of the risk differences of cardiovascular serious adverse events in patients randomized to varenicline versus placebo in studies examining patients with cardiovascular disease.

Figure S2. Forest plot of the risk differences of cardiovascular serious adverse events in patients randomized to varenicline versus placebo in studies examining patients without cardiovascular disease.

Figure S3. Forest plot of the risk differences of all‐cause mortality in patients randomized to varenicline versus placebo in studies examining patients with cardiovascular disease.

Figure S4. Forest plot of the risk differences of all‐cause mortality in patients randomized to varenicline versus placebo in studies examining patients without cardiovascular disease.

Figure S5. Funnel plot of included studies.