Abstract

The ‘Axial Age’ (500–300 BCE) refers to the period during which most of the main religious and spiritual traditions emerged in Eurasian societies. Although the Axial Age has recently been the focus of increasing interest,1-5 its existence is still very much in dispute. The main reason for questioning the existence of the Axial Age is that its nature, as well as its spatial and temporal boundaries, remain very much unclear. The standard approach to the Axial Age defines it as a change of cognitive style, from a narrative and analogical style to a more analytical and reflective style, probably due to the increasing use of external memory tools. Our recent research suggests an alternative hypothesis, namely a change in reward orientation, from a short-term materialistic orientation to a long-term spiritual one.6 Here, we briefly discuss these 2 alternative definitions of the Axial Age.

Keywords: Axial Age, history, iron age, life history theory, memory, motivation, religion, writing

The concept of the Axial Age developed out of the observation that most of the current world religions (Buddhism, Hinduism, Daoism, Judaism, Christianity, Islam) can trace their origins back to a specific period of Antiquity around 500 to 300 BCE, and that this period is the first in human history to have seen the appearance of thinkers who still are a source of inspiration for present-day religious and spiritual movements: Socrates, Pythagoras, Buddha, Mahavira, Confucius, Lao Tse, the Hebrew prophets, etc.7 By contrast, the Egyptian, Greek and Mesopotamian religions have had no obvious impact on today's religious and spiritual life.

Thus, the Axial Age was defined with reference to modern religions and the modern world. It is supposed to have been the beginning of a new era (this is the origin of the term ‘axial’). Socrates, Confucius, and Buddha are understood to be closer to modern people than to inhabitants of early chiefdoms and archaic empires. They ask the same questions and provide the same responses as today's religious and spiritual leaders.7

The consequence of such an atheoretical definition is that it is difficult to decide when the Axial Age began, and when it ended. For instance, Jaspers originally proposed to include Homer (around 800 BCE), whose work provided the cultural background of Greek philosophy. However, most historians working on the Axial Age now consider that there is nothing axial in Homer, as the Iliad and the Odyssey are very similar to other epic poems composed in pre-state societies. Furthermore, these poems are read today not for religious reasons, but mostly for aesthetic reasons. In the same way, Jaspers proposed to include Zarathustra in the list of axial figures probably because Zoroastrianism was the most widespread religion at the time (due to the extension of the Persian empire), and because it is supposed to have influenced the Hebrew religion.7 However, Zoroastrianism never became a world religion, never developed the proselytism so typical of world religions, and never spread beyond the political borders of the Persian Empire.8-10

In itself, the loose and atheoretical definition of the Axial Age is not a problem. Many scientific inquiries begin with the observation that several independent phenomena share some ‘family resemblance’ and that it may be possible to discover a common cause behind this resemblance. In arguing that this period constitutes a genuine transformation in human history (because its thinkers have inspired so much of modern spirituality), rather than the axial religions having been arbitrarily bundled together because of mere temporal coincidence, scientists, philosophers, anthropologists, historians, sociologists have proposed a number of theories of the Axial Age.

To date, most theorists have suggested that the nature of the axial change was cognitive or intellectual. In particular, it has often been argued that, during the Axial Age, people began to be more ‘reflexive’.2,3,11,12 For instance, Jaspers originally opposed ‘mythos’ to ‘logos,’ and defined reflexivity as ‘general consciousness’ and as ‘thinking about thinking’: “Hitherto unconsciously accepted ideas, customs and conditions,” Jaspers writes, “were subjected to examination, questioned and liquidated.”7 This radical questioning of tradition led, he claims, to monotheism in the eastern part of the Eastern Mediterranean, and to the birth of philosophy in its western part.

Philosophers and historians of religions have proposed a range of terms for what they take to be the psychological basis of the axial change. For instance, Voegelin coined the term ‘mythospeculation’;13 Momigliano used the term ‘criticism’;11 Schwartz proposed the term “Age of Transcendence,’ referring to the new ability of “standing back and looking beyond” and of ‘self-distanciation;”12 and Assman suggested “the Mosaic distinction” and “cognitive disembedding from the symbiotic embeddedness of early man in the cycles of nature, political institutions, and social constellations.”4

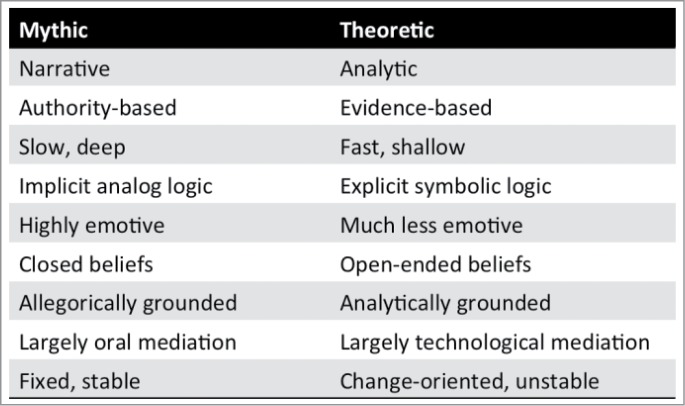

In recent years, Robert Bellah3 has proposed to use Merlin Donald's theory of cognitive change14,15 to explain the axial change. According to Donald's theory, human culture has gone through 3 transitions: from ape culture to mimetic culture (through the expansion of executive functions), from mimetic to mythic culture (through the emergence of linguistic symbols), and from mythic culture to theoretic culture (through the invention of writing). According to Bellah, the Axial Age corresponds to the transition from mythic to theoretic culture. And indeed, a range of characteristics imputed by Donald to theoretic culture do appear to have been central in the Axial Age as it is defined by the standard cognitive approach (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

The mythic and theoretic styles of cognitive governance (adapted from Donald, 2012).

According to Donald, the key element in the emergence of a theoretic culture is the invention of external symbolic memory technology.4,14 The development of external memory in the form of writing, lists, scriptures, etc., massively enhanced individuals' abilities to reflect on their own thoughts and challenge prior beliefs, which eventually led to a new kind of culture and a new way of dealing with the world.

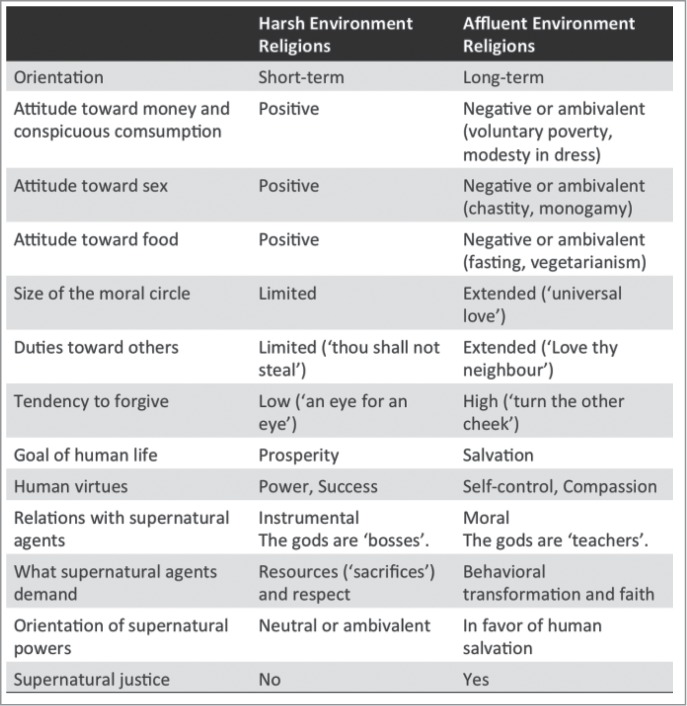

In our paper,6 we propose a new characterization of the Axial Age based not on a cognitive change but on a behavioral one (Fig. 2). We argue that the real change is the emergence of self-discipline and selflessness, which were new at the time and which today form the core of world religions. On this view, the reason why such figures as Buddha, the Stoics, Lao Tse and Confucius are still read today is that they proposed a new way of life in which morality and self-discipline are central.

Figure 2.

Religions in harsh and affluent environments.

On this view, the Axial Age is major psychological change from a period in which short-term orientations dominated, toward a period in which long-term orientations became culturally dominant. These behavioral changes concern cooperative behaviors (which can be seen in religious concerns for compassion and charity) and sexual behaviors (visible in religious concerns for chastity and socially imposed monogamy), but also economic behaviors (condemnation of greed and conspicuous consumption) and parenting behaviors (increasing investment in children). In short, these changes represent a major psychological transformation. In our paper,6 we suggested that these coordinated changes could result from an adaptive response to a more affluent behavior. Indeed, Life-History Theory has recently suggested that humans adaptively respond to a more favorable environment by ‘slowing down’ their strategies and displaying more long-term oriented behaviors such as high investment in children, in pair-bonding, in health or in cooperation.

This cultural dynamic does not entail that Iron Age societies became predominantly axial. On the contrary, most people in Iron Age societies still lived only a little way above bare subsistence level, and consequently saw only minor modifications to their preferences. In consequence, our model applies to the initial emergence of Axial Age doctrines as an elite interest, not to their subsequent diffusion among large populations. In fact, once they achieve cultural domination, moralizing and spiritual religions usually start to be “despiritualized” by the materialistic needs of the less affluent classes, producing phenomena such as the cult of the saints, the pilgrimages toward holy sanctuaries, and the venerations of relics.16,17

More generally, it is to be expected that there was a wide spectrum of axial believers, ranging from people who had a superficial knowledge of spiritual and moralizing religions but liked them, to people who committed some resources through alms giving, to people who actually went and lived in the desert and made vows of poverty. Roman accounts of conversion to Christianity describe all these motives, and more.18 Ultimately, all spiritual movements had to make concessions about the kind of life they asked from their followers, and most ended up splitting believers into 2 broad classes, the individuals fully committed to a spiritual life (priest, monks, hermits) and the lay people who supported the spirituals, but for whom the ascetic constraints of a religious life were relaxed.19-22

Finally, it is worth noting that, in this theory, religion is viewed as just the tip of the iceberg – a reflection of a deeper, more intuitive and automatic psychological change.23 Religious commandments and beliefs (afterlife punishment and rewards) are not advantageous by themselves. They rather become attractive because they allow justifying and legitimizing a range of new behaviors that were already emerging in the Eurasian upper classes. In line with this idea, Axial Age doctrines were associated with a variety of beliefs, including polytheism (e.g., in Daoism, Buddhism, and most Greek philosophical sects), dualism (in Manichaeism), monotheism (in Christianity), and largely non-theistic worldviews, as in the case of the Stoics, who saw the world as suffused with justice, in the absence of personified gods. To take specific examples, Socrates, Confucius, the author of Ecclesiastes, and even the Buddha were not particularly religious people. They all emphasized self-discipline as the way of life, but they did not see this way of life as specially linked to a God or the gods. But they lived in religious societies, surrounded by people who believed in supernatural entities. In this environment, the religious version of this new way of life had a cultural advantage.

This motivation theory of the Axial Age has some antecedents. In particular, the distinction between short-term/materialistic religions and long-term/ascetic religions is very much in line with Max Weber's distinction between ‘this-worldly’ religions and ‘other-worldly’ religions.24-27 ‘This-worldly’ religions are about succeeding in the world, getting more resources, and social success, while ‘other-worldly’ religions condemn the pursuit of material and social success and rather promote self-discipline and intensive work. Interestingly. Interestingly, Max Weber's work on religion was probably at the origin of Karl Jaspers' conceptualization of the Axial Age. However, while Weber was interested in religious ethos (in particular the Protestant ethos), Jaspers put more emphasis on religious beliefs. In our paper, we argue that, in line with Weber's approach, what really matters in the history of religions are motivational changes rather than doctrinal ones.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

FUNDING

NB thanks PSL* for funding its Chaire d'excellence and the 2 grants ANR-10-LABX-0087 IEC and ANR-10-IDEX-0001-02 PSL*.

References

- 1.Armstrong K. The great transformation: The beginning of our religious traditions. Anchor 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Árnason JP, Eisenstadt SSN, Wittrock B. Axial civilizations and world history. 4, Brill Academic Pub; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bellah RN. Religion in human evolution: From the Paleolithic to the axial age. Harvard University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bellah RN, Joas H. The Axial age and its consequences. Harvard University Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Graeber D. Debt: The first 5,000 years. Melville House; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baumard N, Hyafil A, Morris I, & Boyer P. Increased Affluence Explains the Emergence of Ascetic Wisdoms and Moralizing Religions. Curr Biol 2015; 25:10-15; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cub.2014.10.063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jaspers K. The origin and goal of history. Routledge; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boyce M. Zoroastrians: their religious beliefs and practices. Psychology Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rose J. Zoroastrianism: An Introduction. IB Tauris 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zaehner RC. The dawn and twilight of Zoroastrianism. Sterling Publishing Company Inc; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eisenstadt SSN. The origins and diversity of axial age civilizations. SUNY Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schwartz BI. The age of transcendence. Daedalus 1975; 104(2): 1-7. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Voegelin E. Order and history. University of Missouri Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Donald M. Origins of the modern mind: Three stages in the evolution of culture and cognition. Harvard University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Donald M. A mind so rare: The evolution of human consciousness. Norton & Company; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Creel HG. What is Taoism?: and other studies in Chinese cultural history. University of Chicago Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thomas K. Religion and the decline of magic: studies in popular beliefs in sixteenth and seventeenth-century England. Penguin; UK: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 18.MacMullen R. Christianizing the Roman empire (AD 100-400). Yale University Press; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gombrich R. Theravada Buddhism: A social history from ancient Benares to modern Colombo. Routledge; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Olivelle P. The Asrama System: The history and hermeneutics of a religious institution. Oxford University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kohn L. Monastic life in medieval Daoism: a cross-cultural perspective. University of Hawaii Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brown PRL. The body and society: Men, women, and sexual renunciation in early Christianity. Columbia Univ Pr; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baumard N, Boyer P. Religious Beliefs as Reflective Elaborations on Intuitions: A Modified Dual-Process Model. Curr Dir Psychol Sci 2013, 224 (2013): 295-300; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1177/0963721413478610 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weber M. Economy and society; an outline of interpretive sociology. Bedminster Press; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weber M. The sociology of religion. Beacon Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weber M. The Religion of China. Confucianism and Taoism. Translated and Edited by Gerth Hans H. With an Introduction by Yang CK. Collier Macmillan; 1964. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weber M. The Protestant ethic and the spirit of capitalism. Roxbury Pub; 1998. [Google Scholar]