Abstract

Purpose

We have previously reported that embryonic rat bladder mesenchyma has the appropriate inductive signals to direct pluripotent mouse embryonic stem cells toward endodermal derived urothelium and develop mature bladder tissue. We determined whether nonembryonic stem cells, specifically bone marrow derived mesenchymal stem cells, could serve as a source of pluripotent or multipotent progenitor cells.

Materials and Methods

Epithelium was separated from the mesenchymal shells of embryonic day 14 rat bladders. Mesenchymal stem cells were isolated from mouse femoral and tibial bone marrow. Heterospecific recombinant xenografts were created by combining the embryonic rat bladder mesenchyma shells with mesenchymal stem cells and grafting them into the renal subcapsular space of athymic nude mice. Grafts were harvested at time points of up to 42 days and stained for urothelial and stromal differentiation.

Results

Histological examination of xenografts comprising mouse mesenchymal stem cells and rat embryonic rat bladder mesenchyma yielded mature bladder structures showing normal microscopic architecture as well as proteins confirming functional characteristics. Specifically the induced urothelium expressed uroplakin, a highly selective marker of urothelial differentiation. These differentiated bladder structures demonstrated appropriate α-smooth muscle actin staining. Finally, Hoechst staining of the xenografts revealed nuclear architecture consistent with a mouse mesenchymal stem cell origin of the urothelium, supporting differentiated development of these cells.

Conclusions

In the appropriate signaling environment bone marrow derived mesenchymal stem cells can undergo directed differentiation toward endodermal derived urothelium and develop into mature bladder tissue in a tissue recombination model. This model serves as an important tool for the study of bladder development with long-term application toward cell replacement therapies in the future.

Keywords: urinary bladder, stem cells, mesoderm, urothelium, bone marrow

The bladder functions to store urine at low pressure and expel urine periodically by detrusor contractions. The bladder is lined by an epithelium cell layer, the urothelium, which is supported by an extracellular matrix rich lamina propria surrounded by organized layers of smooth muscle cells.1 Previous studies have demonstrated that cell-cell signaling between stroma and epithelium is integral for correct bladder development.2–4 Baskin et al reported reciprocal cell-cell signaling between the stromal and epithelial compartments.3 Stromal signaling is required to influence epithelial cell differentiation and in turn the epithelium influences stromal development and maturation. When either of these constituents is absent, bladder development fails to occur. Previous experiments with bladder tissue recombinant xenografts of EBLM have shown that it is a potent inductor of bladder morphogenesis and functional differentiation when associated with embryonic bladder urothelium,3 adult bladder urothelial cells5 or mouse embryonic stem cells.6 However, xenografts of EBLM alone yielded a graft composed of stroma without obvious cellular differentiation.4

During the last several years a great deal of attention has been focused on the plasticity of bone marrow derived stem cells. MSCs are a population of stem cells in bone marrow that are distinct from hematopoietic stem cells. MSCs are multipotent adult stem cells that reside in the bone marrow microenvironment.7 Traditionally stem cells were believed to be lineage restricted and organ specific. However, recent studies have demonstrated that bone marrow derived stem cells from mice and humans have the ability to cross lineage boundaries and form functional components of other tissues, expressing tissue specific proteins in organs such as the heart, liver, brain, skeletal muscle and vascular endothelium.8,9 Recent reports suggest that MSCs can also differentiate into nonstromal tissues, such as lung epithelial cells10 and pigment epithelial cells.11 In another study transplantation of a select population of bone marrow derived stem cells into lethally irradiated mice resulted in the appearance of bone marrow derived epithelial cells in the liver, gastrointestinal tract and skin.12

In this study we hypothesized that MSCs could contribute to the urothelial regeneration in bladder. We investigated bladder tissue development by recombining EBLM from rats with MSCs from adult mice and xenografting in nude mice host kidney. Histological examination of the xenografts showed mature bladder structures with normal microscopic architecture as well as proteins confirming functional characteristics. Our results show that bone marrow derived MSCs in the appropriate signaling environment can undergo directed differentiation toward endodermal derived urothelium and develop into mature bladder tissue in a tissue recombination model.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolation and Culture of MSCs From Bone Marrow

Bone marrow derived MSCs were isolated from the femurs and tibias of adult mice according to a previously described method.13 Briefly, MSCs were harvested by flushing femoral and tibial cavities with Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium. Bone marrow cells were cultured in medium containing a 30%:50% mixture of MCDB 191 and Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium low glucose, supplemented with platelet-derived growth factor-BB (9 ng/ml), epidermal growth factor (9 ng/ml), leukemia inhibitory factor (900 U/ml) (ESGRO®), 2% fetal calf serum and antibiotics. Nonadherent hematopoietic cells were removed and the medium was replaced. The adherent spindle-shaped MSC population was used in this study.

Tissue Recombination Grafts of Mouse Bone Marrow MSCs With Rat EBLM

All animal experiments were performed in accordance with the Vanderbilt University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Pregnant Sprague-Dawley rats (Harlan, Indianapolis, Indiana) were sacrificed at E:14 (plug day = 0). Female embryos were isolated and the bladders were removed. The bladders were placed in calcium and magnesium- free Hank’s saline (Gibco®) containing 24 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (Sigma®) for 80 minutes to release the bladder urothelium. EBLM and embryonic bladder epithelium components were separated manually under microscopic examination, washed thoroughly in RPMI-1430 (Gibco) and stored in medium before use. MSCs were detached from the flasks by gentle trypsinization and viable cells were counted on a hemocytometer using trypan blue exclusion. MSCs (25,000 cells) were resuspended in 30 µl rat collagen matrix and plated as a plug.

EBLM, now left as pure mesenchymal shells devoid of epithelium (1 shell used per graft), were physically placed into each collagen plug and incubated at 36C for plug solidification. Before grafting, each mesenchymal shell was approximately 0.3 × 0.3 mm and, therefore, no difficulty was noted when placing the shell(s) into the collagen plugs. RPMI-1430 tissue culture medium supplemented with 1% antibiotic-antimycotic solution (Gibco) and 4% HyClone® cosmic calf serum was then applied for 1 hour. Control grafts were also created with embryonic mouse bladder mesenchyma alone, MSCs alone and collagen matrix alone devoid of any cellular constituents.

Athymic Nude Mouse Host Xenografting

Male athymic nude mice (CD-1 nu/nu Charles River) at ages 6 to 7 weeks served as the host for subrenal capsule grafts. Kidney capsule xenografting, xenograft harvesting and processing were done according to previously described methods.6

Staining and Immunohistochemistry

For immunohistochemistry all incubations were done at room temperature unless otherwise stated. Slides were deparaffinized and hydrated through xylene and graded alcohols. Antigen retrieval was performed on slides by the sodium citrate method with microwaving in 9 mM sodium citrate (pH 5.0) for 9 minutes and then left at room temperature for 1 hour. Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked with Dako Peroxidase Blocking Reagent (Dako, Carpinteria, California) for 13 minutes and sections were washed in phosphate buffered saline for 4 minutes. Immunohistochemistry was performed using a Vectastain® Elite ABC peroxidase kit according to the manufacturer protocol. Sections for Gomori’s trichrome staining were performed with a Gomori’s One-Step Green Trichrome Staining System (DakoCytomation, Carpinteria, California) and an automated stainer platform. This staining was performed elsewhere.

Hoechst staining was performed according to a previously described method.14 Briefly, paraffin sections were deparaffinized and incubated with 3 µg/ml Hoechst 33247 for 1 minute at room temperature. Following 1 to 5 minutes of washing in running tap water the slides were coverslipped using Vectashield® and sealed with clear lacquer. Sections were examined by fluorescence microscopy.

LCM/DNA Isolation/PCR

To confirm urothelium derived from MSC cells we performed LCM, followed by SRY gene PCR, after sex mismatched recombination of EBLM (female rat) and MSC (male mouse) in xenograft. Tissue for LCM was collected prospectively following tissue processing and paraffin wax embedding. Mouse SRY gene primers consisted of the forward and reverse sequences 4′-TTGCTGTCTTTGTGCTAGCC-3′ and 4′-TGGTGAGCATACACCATACC-3′, respectively.

RESULTS

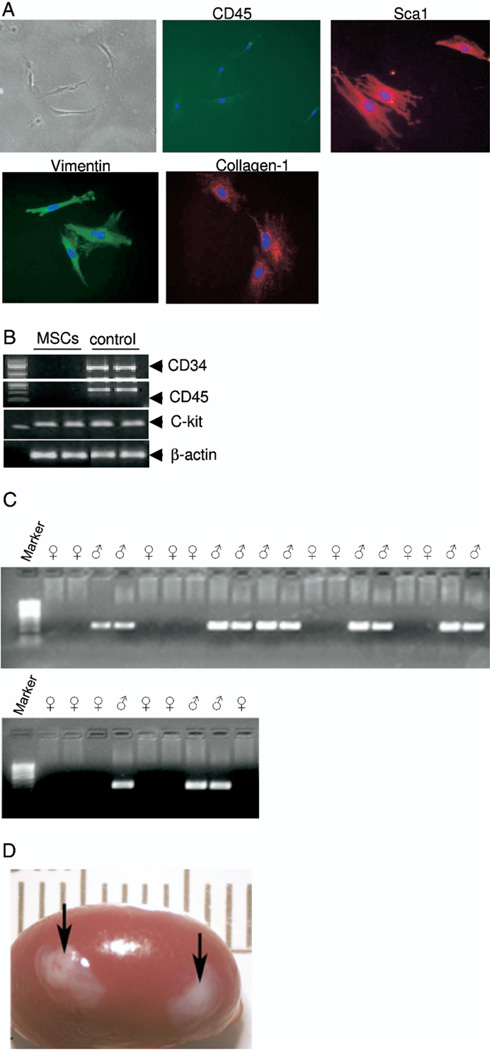

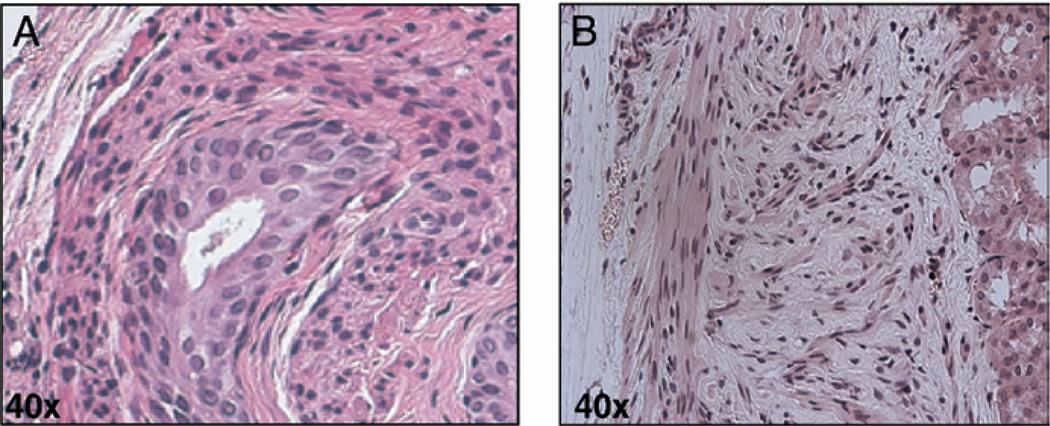

We isolated bone marrow derived MSCs from the femurs and tibias of adult mice. Figure 1, A shows a phase contrast image of MSCs in culture with characterization by Sca1, collagen1, CD45 and vimentin using immunofluorescence staining and c-kit, CD34 and CD45 using PCR (fig. 1, B). CD34−, CD45− and c-kit+, Sca1+, collagen and vimentin positive cells were used in this study. To further investigate the role of embryonic mesenchymal cells in the differentiation of MSCs to bladder urothelium we recombined MSCs (25,000) with E:14 female EBLM and xenograft in host nude mice kidney (fig. 1, C). The xenografts were harvested 42 days after in vivo incubation (fig. 1, D). Hematoxylin and eosin staining of EBLM with MSC grafts showed the bladder tissue structure (fig. 2, A). These structures had central lumenoid cavities, a cluster of surrounding multilayered epithelium, a subepithelial connective tissue layer consistent with lamina propria-like tissue and smooth muscle fibrils. Grafts of MSCs alone did not show any sign of epithelial layer formation (fig. 2, B).

Fig. 1.

Primary cultures of adult mouse bone marrow MSCs and xenograft. A, phase contrast microscopy shows gross morphology of bone marrow mesenchymal cells in culture. Isolated MSCs demonstrated negative CD45 expression, and positive Sca1, Collagen1 and vimentin expression on immunofluorescence. Reduced from ×40. B, PCR analysis reveals MSC specific marker genes CD34 (−), CD45 (−) and C-Kit (+). C, rat E:14 tissue PCR for gender difference using rat SRY gene primers was conclusive for identifying gender differences in E:14 rats. Based on PCR results SRY negative rat EBLM was separated for xenograft. D, gross appearance of xenografts on host mouse kidney.

Fig. 2.

Immunohistochemical staining of xenografts confirmed bladder tissue. A, mouse cultured bone marrow mesenchymal cells plus rat EBLM graft. B, xenograft of MSCs alone. H & E, reduced from ×40.

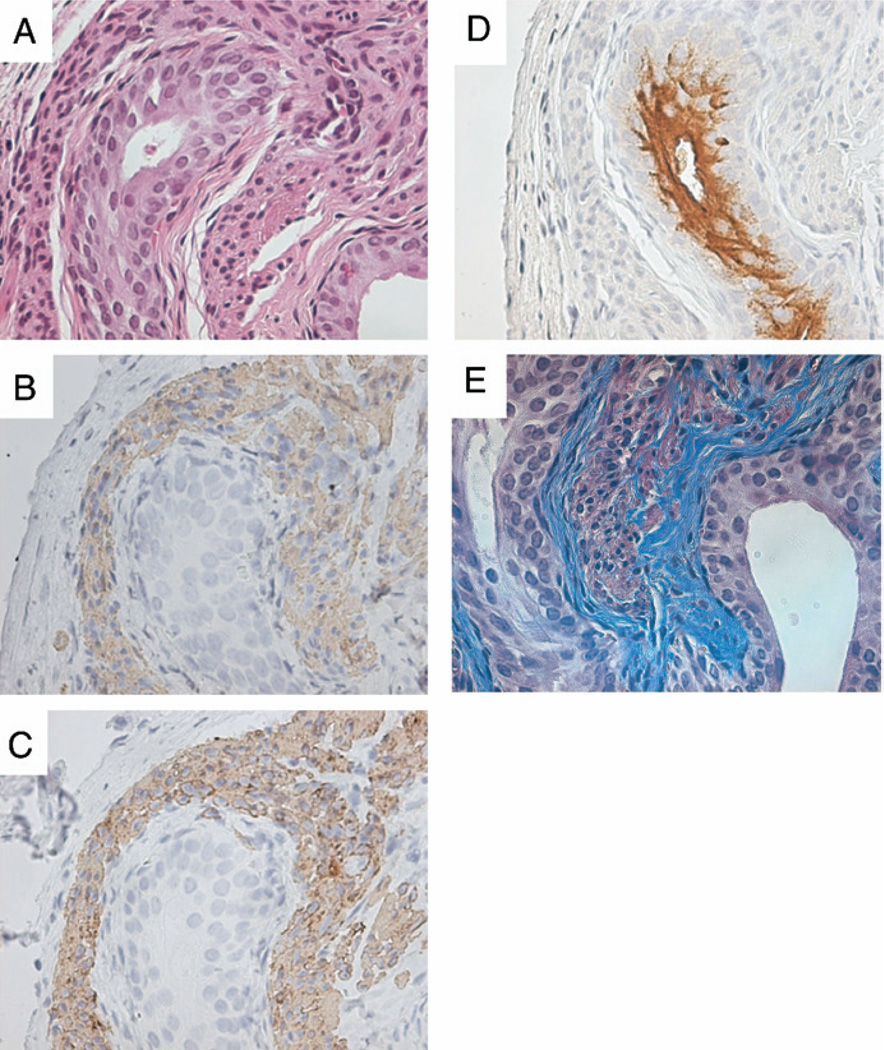

To confirm cell differentiation in the xenograft we performed SMA and desmin immunostaining. Similar to normal fetal bladder development,3 SMA and desmin immunolocalization was visualized subadjacent to the serosa (fig. 3, B and C). Uroplakin immunolocalization verified mature bladder urothelial differentiation and it was associated with the epithelial lining of the lumenoid structures (fig. 3, D). Uroplakin is a selective marker for urothelial cell differentiation and urothelium is the only epithelial cell in the body producing uroplakin. In addition, trichrome staining demonstrated a subepithelial connective tissue layer surrounding the urothelium (fig. 3, E), consistent with lamina propria-like tissue, in combination with an outer smooth muscle layer on SMA immunolocalization. A similar section was also stained for hematoxylin and eosin (fig. 3, A). Overall these results suggest that cellular organization and immunohistochemical staining were consistent with normal bladder tissue histology.

Fig. 3.

Immunohistochemical staining of xenografts confirmed bladder tissue. A, cultured mouse bone marrow mesenchymal cells plus rat EBLM graft. H & E, reduced from ×40. B and C, immunolocalization of SMA staining demonstrates stromal dedifferentiation and desmin staining shows smooth muscle differentiation. Reduced from ×40. D, broad-spectrum uroplakin positive staining reveals mature urothelial cells. Reduced from ×40. E, suburothelial connective tissue layers. Gomori’s trichrome stain, reduced from ×40.

As control, grafts of 1 EBLM shell alone or MSCs alone were performed and harvested after 42 days of incubation (fig. 2, B). Hematoxylin and eosin, and Gomori’s trichrome staining of EBLM only grafts demonstrated a paucity of growth with no evidence of complex differentiation or bladder tissue formation (data not shown). These findings were consistent with data previously reported in the literature.4,5

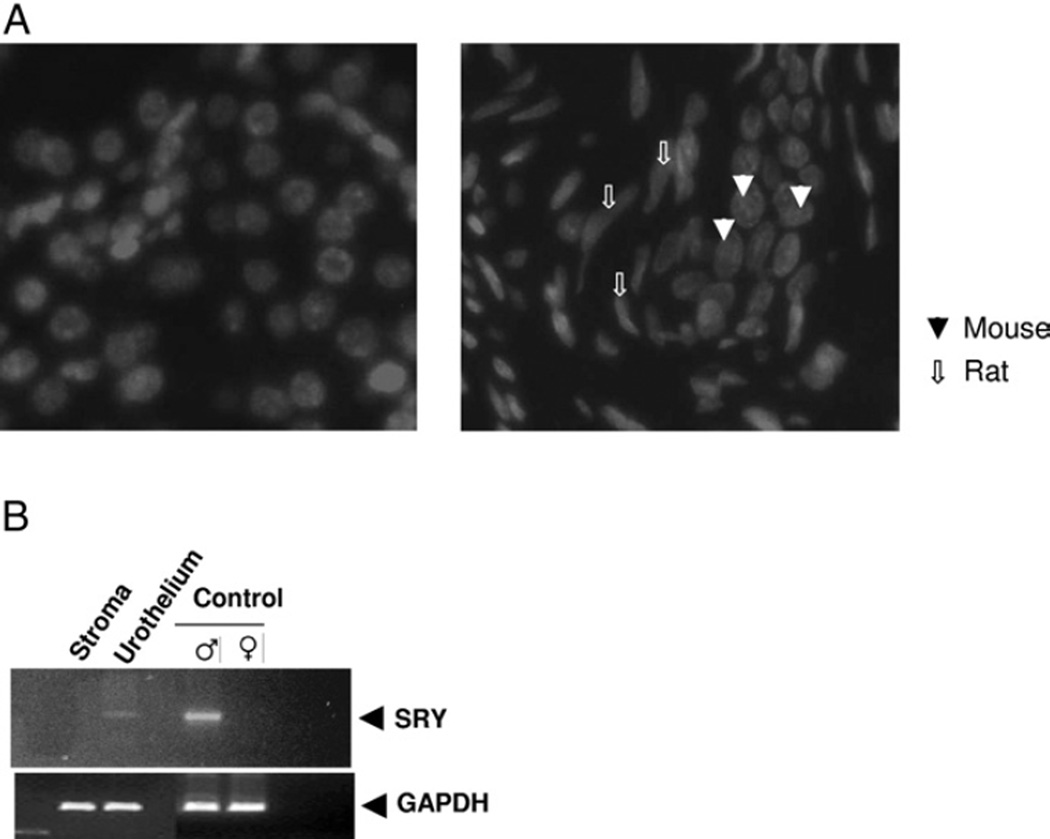

Hoechst dye 33247 was used to distinguish the species of origin of the graft components.14 In our tissue recombinant grafts we used different species (heterospecific), that is rat mesenchyma with mouse MSCs, for the xenograft. A nuclear stippling pattern has been described for mouse nuclei and Hoechst 33247 staining confirmed that the urothelial cells showed the characteristic mouse origin of the urothelium in recombinant tissues and in control mouse kidney (fig. 4, A). Heterospecific recombination techniques assisted with illustrating that our recombinant tissue growth was not due to potential rat urothelial cell carryover in mesenchymal preparations.

Fig. 4.

Differentiation of bone marrow MSCs in urothelial cells. A, control mouse kidney shows characteristic nuclear stippling pattern specific for mouse origin (left) and urothelium demonstrates stippling pattern in xenograft containing mouse bone marrow mesenchymal cells plus rat EBLM (right). B, PCR products of DNA obtained by LCM from xenograft urothelial stromal compartments with corresponding adult male mouse and adult rat bladder controls. Mouse SRY gene primers were used. LCM and DNA isolation with PCR amplification were conclusive for identifying that recombinant urothelium was of male mouse bone marrow MSC origin.

LCM/DNA Isolation/PCR

To further verify that the recombinant urothelium derived from male mouse MSCs in the 42-day grafts was of mouse origin LCM was used to obtain tissue from various compartments. DNA samples were isolated from recombinant urothelium, mesenchyma, native adult male and female mouse bladders (control). PCR was performed with mouse specific primers for the SRY gene. Figure 4, B shows the analysis of mouse SRY gene PCR products, which confirmed the mouse origin of the recombinant urothelium. Briefly, LCM coupled with DNA isolation and PCR was conclusive in defining the recombinant urothelial compartment as having originated from mouse MSCs and not from potential rat urothelial contaminating elements in the EBLM preparation. As described, none of the grafts of EBLM alone yielded bladder tissue growth, further substantiating that the EBLM preparations used were devoid of urothelial contaminants. Together these results suggest that MSCs in the appropriate mesenchymal inductive signaling environment can undergo directed differentiation toward endodermal derived urothelium and develop into mature bladder tissue in a tissue recombination model.

DISCUSSION

Organs consist of epithelial and stromal tissues that are in constant communication with each other. These paracrine signaling events orchestrate the development and function of organs, establishing morphology during organogenesis and maintaining adult differentiation. Previous studies have demonstrated that cell-cell signaling between stroma and epithelium is integral for correct bladder development.2–4 Baskin et al reported reciprocal cell-cell signaling between the stromal and epithelial compartments.3

Mesenchyma induces specific patterns of epithelial morphogenesis15 and it is involved in regulating epithelial proliferation.16 In this study we established the conditions for mouse MSC isolation and tissue recombinant xenografting of MSCs with EBLM. In addition, our results demonstrate that recombining rat EBLM with mouse MSCs xenografted for 42 days shows the bladder tissue structure by hematoxylin and eosin staining. These structures had central lumenoid cavities, a cluster of surrounding multilayered epithelium, a subepithelial connective tissue layer consistent with lamina propria-like tissue and smooth muscle fibrils. E:14 mouse bladders were chosen as the mesenchymal source because of their known strong inductive capability and the lack of preexisting smooth muscle differentiation.4 Previous studies performed with embryonic rat bladders have shown that the initial differentiation of smooth muscle constituents does not start until E:14. The benefit of using such an early embryonic stage for the mesenchymal source is that it should induce epithelial differentiation, while fully allowing an investigation of whether cultured bladder urothelium can induce bladder stromal differentiation through all stages of development.

We observed only pure bladder tissue formation with absolutely no evidence of nonbladder structures adjacent to our MSC derived bladder tissue. In addition, trichrome staining revealed a subepithelial connective tissue layer surrounding the urothelium in combination with an outer smooth muscle layer as indicated by SMA and desmin immunolocalization. Moreover, immunodetection of uroplakin further confirmed bladder tissue formation. Uroplakins are unique proteins expressed only by urothelial cells of the bladder, urethra and ureter.2 Uroplakin is a selective marker for urothelial cell differentiation and uroplakin staining in urothelial clusters indicated that the cells were acting in a manner consistent with functional urothelium.

MSCs have several advantages for basic study and potential clinical application. Withdrawal materials, and isolation and expansion ex vivo are relatively convenient. There is low immunogenesis and they can survive for a long time without losing their stem cell properties. The application of MSCs has little ethical controversy, and they have a strong ability to self-reproduce and differentiate to multilineage cells in vitro and in vivo.

Previous reports by other investigators have revealed that MSCs can undergo differentiation into epithelial cells. Alescio and Di Michele reported that the overall growth of epithelial ducts in 10-day embryonic mouse lungs developing in vitro was enhanced by increasing the amount of bronchial mesenchyma.17 Harris et al used a Cre/lox system together with β-galactosidase and enhanced green fluorescence protein expression in transgenic mice to identify epithelial cells in the lung, liver and skin that developed from bone marrow derived cells without cell fusion.18 Previous studies have shown that the transplantation of MSCs has a limited effect on smooth muscle cell regeneration and poor differentiation as smooth muscle cells in cryo-injured bladder.19 Further studies using MSCs seeded on small intestinal submucosa accelerated the cellular regeneration of bladder constituents and eliminated the fibrosis induced by bladder augmentation with small intestinal submucosa alone.20 Moreover, MSCs injected in the normal bladder barely survived and only a few could be identified in the wall of small arteries.

In this study our results show that bone marrow derived MSCs can undergo directed differentiation toward endodermal derived urothelium and develop into mature bladder tissue. Hoechst 33247 staining revealed that urothelial cells showed the characteristic mouse origin of the urothelium in recombinant tissues and SRY gene PCR further confirmed the origin of the urothelial cells.

Previous experiments with bladder tissue recombinant xenografts of EBLM have been demonstrated to be a potent inductor of bladder morphogenesis and functional differentiation when associated with embryonic bladder urothelium.4 The results of our current investigation support the concept that EBLM is a potent inductor that regulates bone marrow MSC differentiation into bladder urothelium (morphogenesis and cytodifferentiation).

CONCLUSIONS

These data support the notion of the cellular organization and immunohistochemical staining of EBLM with MSC xenografts, consistent with normal bladder tissue histology. In addition, to our knowledge we report the first application of the creation of successful tissue recombinant xenografts of MSCs with embryonic bladder stroma. These findings demonstrate that MSCs under the inductive signaling environment provided by EBLM, could undergo complex differentiation along an endodermal lineage to form mature urothelium with bladder tissue formation. This model may serve as an important tool for the study of bladder development with long-term application toward cell replacement therapies in the future.

Acknowledgments

Gomori’s trichrome staining was performed at the Vanderbilt mouse histology core facility.

Supported by National Institutes of Health Grant R01-DK057483 (JCP) and a Society of Pediatric Urology grant (JHM).

Abbreviations and Acronyms

- E:14

embryonic day 14

- EBLM

embryonic bladder mesenchyma

- LCM

laser capture microdissection

- MSC

mesenchymal stem cell

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- SMA

smooth muscle α-actin

Footnotes

Study received Vanderbilt University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approval.

REFERENCES

- 1.Tanagho E. Anatomy of the lower urinary tract. In: Walsh P, Gittes B, Perlmutter A, Stamey T, editors. Campbell’s Urology. 1. 5th. Vol. 1. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1986. pp. 46–74. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Staack A, Hayward SW, Baskin LS, Cunha GR. Molecular, cellular and developmental biology of urothelium as a basis of bladder regeneration. Differentiation. 2005;73:121. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.2005.00014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baskin LS, Hayward SW, Young P, Cunha GR. Role of mesenchymal-epithelial interactions in normal bladder development. J Urol. 1996;156:1820. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baskin LS, Hayward SW, Sutherland RA, DiSandro MJ, Thomson AA, Goodman J, et al. Mesenchymal-epithelial interactions in the bladder. World J Urol. 1996;14:301. doi: 10.1007/BF00184602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oottamasathien S, Williams K, Franco OE, Thomas JC, Saba K, Bhowmick NA, et al. Bladder tissue formation from cultured bladder urothelium. Dev Dyn. 2006;235:2795. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oottamasathien S, Wang Y, Williams K, Franco OE, Wills ML, Thomas JC, et al. Directed differentiation of embryonic stem cells into bladder tissue. Dev Biol. 2007;304:556. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pittenger MF, Mackay AM, Beck SC, Jaiswal RK, Douglas R, Mosca JD, et al. Multilineage potential of adult human mesenchymal stem cells. Science. 1999;284:143. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5411.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Theise ND, Nimmakayalu M, Gardner R, Illei PB, Morgan G, Leperman L, et al. Liver from bone marrow in humans. Hepatology. 2000;32:11. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2000.9124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Orlic D, Kajstura J, Chimenti S, Jakoniuk I, Anderson SM, Li B, et al. Bone marrow cells regenerate infarcted myocardium. Nature. 2001;410:701. doi: 10.1038/35070587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang G, Bunnell BA, Painter RG, Quiniones BC, Tom S, Lanson NA, Jr, et al. Adult stem cells from bone marrow stroma differentiate into airway epithelial cells: potential therapy for cystic fibrosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:186. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406266102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arnhold S, Heiduschka P, Klein H, Absenger Y, Basnaoglu S, Kreppel F, et al. Adenovirally transduced bone marrow stromal cells differentiate into pigment epithelial cells and induce rescue effects in RCS rats. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:4121. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krause DS, Theise ND, Collector MI, Henegariu O, Hwang S, Gardner R, et al. Multi-organ, multi-lineage engraftment by a single bone marrow-derived stem cell. Cell. 2001;105:369. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00328-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spagnoli A, Longobardi L, O’Rear L. Cartilage disorders: Potential therapeutic use of mesenchymal stem cells. Endocr Dev. 2005;9:17. doi: 10.1159/000085719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cunha GR, Vanderslice KD. Identification in histological sections of species origin of cells from mouse, rat and human. Stain Technol. 1984;59:7. doi: 10.3109/10520298409113823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kratochwil K. Tissue combination and organ culture studies in the development of the embryonic mammary gland. In: Gwatkin RBL, editor. Developmental Biology: A Comprehensive Synthesis. Vol. 4. New York: Plenum Press; 1987. pp. 315–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sugimura Y, Cunha GR, Donjacour AA. Prostatic glandular architecture: whole mount analysis of morphogenesis and androgen dependency. In: Rodgers CH, editor. Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia. Vol. 2. Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office; 1986. pp. 55–72. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alescio T, Di Michele M. Relationship of epithelial growth to mitotic rate in mouse embryonic lung developing in vitro. J Embryol Exp Mophol. 1968;19:227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harris RG, Herzog EL, Bruscia EM, Grove JE, Van Arnam JS, Krause DS. Lack of a fusion requirement for development of bone marrow-derived epithelia. Science. 2004;305:90. doi: 10.1126/science.1098925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.De Coppi P, Callegari A, Chiavegato A, Gasparotto L, Piccoli M, Taiani J, et al. Amniotic fluid and bone marrow derived mesenchymal stem cells can be converted to smooth muscle cells in the cryo-injured rat bladder and prevent compensatory hypertrophy of surviving smooth muscle cells. J Urol. 2007;177:369. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.09.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chung SY, Krivorov NP, Rausei V, Thomas L, Frantzen M, Landsittel D, et al. Bladder reconstitution with bone marrow derived stem cells seeded on small intestinal submucosa improves morphological and molecular composition. J Urol. 2005;174:353. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000161592.00434.c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]